- 1Hanover Center for Health Communication, University of Music Drama and Media, Hanover, Germany

- 2Interdisciplinary Genitourinary Oncology, Department of Urology and Medical Oncology, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany

- 3Clinic for Paediatrics III, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany

A scoping review was conducted to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the unmet needs and communication challenges faced by long-term cancer survivors. Information seeking, barriers, and avoidance behaviors were reflected. Following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines, five databases were searched. Of 1,041 articles, 36 met the eligibility criteria. Studies focused on breast and prostate cancer survivors (50%) and survivors residing in North America and Canada (56%). Information needs mainly referred to specific cancer types, recurrence, sexual functioning, fertility, and comorbidities. Information barriers include concerns about trust in information quality, information overload, and difficulties in finding and understanding information. Most survivors are active information seekers, but some also exhibit information avoidance. Survivors prefer information from their healthcare provider or the Internet, as well as medical information and experiences from other survivors. Further research is needed on survivors from vulnerable groups, CAYAs (children, adolescents, and young adults), and ethnic minorities.

1 Introduction

The development of new treatment options has significantly improved cure rates for cancer and increased the number of cancer survivors in all age groups (RKI, 2023; Siegel et al., 2024). As of January 2022, the number of cancer survivors in the USA is estimated at 18.1 million, with 70% (USA) of them being long-term cancer survivors (LTCS) having lived five or more years after diagnosis (Tonorezos et al., 2024). Especially for children, adolescents, and young adults (CAYA) with cancer, long-term survival rates have increased to an average of 80% in developed countries (Robison and Hudson, 2014). However, late effects of the cancer and its therapy, associated with increased morbidity, shorter life expectancy, a reduced quality of life, and psychological distress, occur across all sociodemographic and socioeconomic groups and cancer types, often long after diagnosis and treatment (Fosså et al., 2008; Stein et al., 2008; Arndt et al., 2017; Byrne et al., 2022). Especially for CAYA cancer survivors, intense treatment may impair development and maturation in childhood and adolescent years, leading to lifelong health problems (Grossi, 1998). Moreover, after major body-altering interventions, there are possible lifelong impairments like stoma, prosthesis, blindness, or cognitive impairment for all LTCS (Byrne et al., 2022).

Thus, cancer survivors need long-term care and health provision services that address the various direct and indirect long-term and late effects and reduce the likelihood of the development of further effects in holistic approaches (Bergelt et al., 2022). However, while oncologists are in charge of immediate cancer treatment and follow-up care, regular healthcare providers might not feel responsible/or are not sufficiently competent regarding the long-term and late effects of cancer (Lie et al., 2015). This can lead to a care gap and the need for information and counseling tailored to different groups of LTCS (Davies et al., 2020). Although there is research about cancer patients’ and survivors’ information needs and behaviors in general, most studies focus on information needs during diagnosis and treatment (Fletcher et al., 2017). This scoping review aims to systematically summarize current knowledge about long-term survivors’ information needs, barriers, behaviors, and preferences, identify research gaps and key challenges in cancer communication for LTCS, and delineate priorities for future research. While the review follows a broad approach to gain an overview of LTCS’ information needs, behaviors, and preferences, some survivor groups are of particular interest. Childhood, adolescent, and young adult (CAYA) cancer survivors are especially vulnerable because their illness occurs early in life (Grossi, 1998; Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Byrne et al., 2022). In addition, survivors experience health disparities related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES) (Aziz and Rowland, 2002; Braveman and Tarimo, 2002; Ward et al., 2004; Viswanath, 2006; Adler and Rehkopf, 2008; Polite et al., 2017; Butler et al., 2020).

1.1 Cancer-related uncertainty management, information seeking, and avoidance

Cancer patients experience uncertainty about their illness, symptoms, treatment, themselves, their relationships, and their future (Mishel, 1990; Ferrell et al., 1998; O’Hair et al., 2003; O’Hair et al., 2008; Thompson and O’Hair, 2008). This can be both a positive and a negative state of not knowing (Brashers, 2001). These feelings of uncertainty may change during the course of the disease and treatment, but continue in survivorship (McKinley, 2000; Gill et al., 2004; Miller, 2014). According to the Uncertainty Management Theory (UMT), individuals aim to manage—i.e., to reduce, increase, or maintain—their uncertainties by seeking or avoiding information (Brashers et al., 2000; Link and Baumann, 2022a). Thus, ‘information needs’, which can be defined as the patient’s “recognition that their knowledge is inadequate to satisfy a goal, within the context/situation that they find themselves at a specific point in the time” (Ormandy, 2011), arise from the cancer patient’s uncertainty perception in a particular stage and context of illness, and are possible motivators of health information seeking and avoiding (Brashers et al., 2000; Kahlor, 2010), which have already been researched comprehensively in the context of cancer (Miller, 2014).

Studies on cancer information behavior mainly focus on active, needs-oriented information-seeking, i.e., a purposeful acquisition of information from selected information sources via specific channels to achieve goals like knowledge gain, attitude formation, decision making, or coping with uncertainties (Johnson and Meischke, 1993; Brashers, 2001). Most cancer patients, especially those with higher income and education, are active information seekers (Finney Rutten et al., 2016). But some individuals receive information only when they get in touch with it in everyday media use (information scanning; Niederdeppe et al., 2007; Grimm and Baumann, 2019). Finally, there is also information avoidance, meaning that the acquisition of available but potentially unwanted cancer-related information is deliberately not used or even actively avoided (Emanuel et al., 2015; Grimm and Baumann, 2019). Individuals with more pessimistic beliefs about the prevention and treatment of cancer, who are less health literate and less trusting of information sources, are more likely to avoid cancer information (Link and Baumann, 2022b). Studies report mixed results on sociodemographic factors that predict information avoidance (Link and Baumann, 2022b). A higher socioeconomic status seems to reduce the likelihood of health information avoidance (Ramanadhan and Viswanath, 2006; Chae, 2016; Nelissen et al., 2017; Chae et al., 2020; Link and Baumann, 2022b).

Several theoretical models help to explain the motivations and barriers of cancer information seeking, such as the Comprehensive Model of Information Seeking (CMIS, Johnson and Meischke, 1993), and the Planned Risk Information Seeking Model (PRISM; Johnson and Meischke, 1993; Kahlor, 2010; Hovick et al., 2014). The latter has already been applied and adjusted to the case of cancer information avoidance (e.g., Link and Baumann, 2022b). As the CMIS suggests, both sociodemographic and information carrier factors can contribute to or be barriers to (successful) information-seeking (Johnson and Meischke, 1993). On the information side, the sheer quantity of available health information can lead to information overload (Viswanath et al., 2012). The quality and depth of the available information are difficult to verify for the survivor, and much false information is circulating on the Internet (Arora et al., 2008; Maddock et al., 2011; Viswanath et al., 2012). On the individual side, the capability to assess the quality of and understand information can differ by the individual, e.g., depending on education level (Arora et al., 2008; Hesse et al., 2008; Maddock et al., 2011). Information carrier factors can also be applied to information preferences, such as the preferred delivery of information, e.g., the type of media or source (Johnson and Meischke, 1993).

1.2 Information seeking across the cancer journey

Cancer patients undergo a so-called cancer journey from diagnosis to survivorship or palliative care (Mistry et al., 2010). Apart from different aspects of (medical) care needs at each stage of the continuum, the need for information in general, the relevance of different cancer-related information, and preferred sources and communication formats are changing throughout the cancer journey (Grimm and Baumann, 2019; Squiers et al., 2005).

Cancer patients thus undergo a cancer information seeking journey with changing informational and supportive needs and behaviors at each stage (Grimm and Baumann, 2019; Mistry et al., 2010; Squiers et al., 2005). Their information needs and behaviors vary throughout their illness (e.g., regarding the topics of interest) and differ by cancer type (Tan et al., 2015). Some still wish to be well informed about all aspects of their illness after completing treatment (Mistry et al., 2010; Hoekstra et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2017; Johnston et al., 2021), some, however, may want to distance themselves from this episode of illness in life and thus avoid information concerning cancer (Link and Baumann, 2022b).

When cancer survivors are given information about long-term consequences around the time of their diagnosis, they may feel too distressed and anxious to understand and process these potentially frightening facts or probabilities, and thus prefer not to be informed; they may also be concerned about whether they will recall this information later in their survivorship (van Osch et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2017). The amount of information and use of complex medical terms can also prevent survivors from information involvement (Kessels, 2003; van Weert et al., 2011; Fletcher et al., 2017). Although cancer survivors still visit their healthcare provider more often than patients without a cancer history, they still report unmet information needs (Soothill et al., 2001; Harrison et al., 2011; Hoekstra et al., 2014). They prefer their healthcare providers as a source of information but feel that the information obtained is insufficient (Finney Rutten et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2011; Finney Rutten et al., 2016). This leads them to use the Internet for acquiring additional health- and cancer-related information (Finney Rutten et al., 2006; Chou et al., 2011; Finney Rutten et al., 2016).

Apart from differences along the cancer journey, cancer survivors are a diverse group with individually varying needs and behaviors. Health disparities due to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES), such as differences in mortality, the likelihood of developing cancer, general health status, and discrimination in healthcare, are reported (Aziz and Rowland, 2002; Braveman and Tarimo, 2002; Ward et al., 2004; Adler and Rehkopf, 2008; Polite et al., 2017; Butler et al., 2020). People from ethnic minorities are less likely to survive cancer for five or more years across several cancer domains (Ward et al., 2004; Polite et al., 2017). Racial disparities in cancer outcomes, follow-up, and long-term care are reported (Butler et al., 2020). Cancer survivors with lower SES tend to participate less in rehabilitation services and have unmet needs in that domain (Holm et al., 2013). There are general communication inequalities linked to these health-related social inequalities, such as access to and use of information channels and services, attention to and processing of health information, and capacity and ability to respond to information provided (Viswanath, 2006). Cancer survivors from ethnic minorities are also less likely to seek information and have more problems obtaining it (McInnes et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2010). SES is further related to information seeking in cancer patients, with seeking information from medical and nonmedical sources being more likely for higher educated patients (Lee et al., 2012).

Apart from health and communication disparities due to social inequalities, survivors diagnosed in CAYA years are especially vulnerable and affected by long-term and late effects, since cancer in these life stages can affect physical and mental development, e.g., maturation, education, and hormones. They could also have greater information needs, since information given during diagnosis and treatment was given to the parents instead of the survivors (Grossi, 1998; Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Byrne et al., 2022).

As described above, the information needs, information-seeking behaviors, information preferences, as well as the information barriers and avoidance behaviors of LTCS have been found to differ from those in earlier stages of the cancer patient journey. Further, they are supposed to differ in terms of vulnerabilities, such as race, SES, and age at diagnosis. To develop and provide suitable informational support tailored to the needs of LTCS, a synthesis of research evidence is necessary. Therefore, the following research questions arise:

RQ1: What do we already know about the information needs of LTCS?

RQ1a, 1b, 1c: What are the specific information needs of (a) non-White / ethnic minority LTCS, (b) LTCS with lower SES, (c) CAYA LTCS?

RQ2: What do we already know about the information behaviors and preferences of LTCS?

RQ2a, 2b, 2c: What are the specific information behaviors and preferences of (a) non-White / ethnic minority LTCS, (b) LTCS with lower SES, (c) CAYA LTCS?

RQ3: What do we already know about information barriers and information-avoiding behaviors of LTCS?

RQ3a, 3b, 3c: What are the specific information barriers and information-avoiding behaviors of (a) non-White / ethnic minority LTCS, (b) LTCS with lower SES, (c) CAYA LTCS?

RQ4: What theoretical models are used to explain cancer information seeking and avoidance in LTCS?

RQ5: What are the research gaps and implications for future research on LTCS?

2 Methods

A systematic scoping review according to the PRISMA-ScR was conducted (Tricco et al., 2018). The scoping review is used to follow a broad approach to the topic and determine the scope of literature on information for LTCS systematically, and map the available evidence as well as identify key factors related to information needs, barriers, behavior, and preferences of long-term cancer survivors (Munn et al., 2018). Furthermore, the scoping review is used to identify research gaps to inform priorities for future research in this context (Munn et al., 2018). A pre-registration of the protocol was not applied. The search was conducted in April 2023.

2.1 Information sources and search strategy

Five databases were selected based on their relevance to oncology and health communication, and were searched using relevant keywords: Medline (via PubMed), Scopus, PsycNET, Communication & Mass Media Complete (via EBSCOhost), and Web of Science. A broad search strategy was developed by the first author, consisting of a combination of the terms ‘information’, ‘cancer’, and ‘survivor’ with respective synonyms. The search in the title and abstract field returned a large number of articles about the medical needs of cancer survivors rather than their informational needs. Due to limited project duration and staffing, the review was limited to a title-based search. While this method was necessarily selective, it increased the chances of finding studies that are most relevant to the theme, as a topic in the title indicates a stronger focus on it. Studies that only addressed information needs peripherally – for example, through a single open-ended question within a broader survey — were intentionally excluded. The full search strings and raw export data are available in Appendix A.

2.2 Eligibility criteria and study selection

The population of LTCS was defined as people living with a cancer diagnosis for more than 5 years. The key concepts of ‘Advice’ and ‘Information’ in this study were defined as any written or spoken interpersonal or media-mediated information, data, knowledge, or recommendation that was not part of medical or psychological therapy, i.e., no psychological, genetic, diet or activity counseling or programming from a healthcare provider or professional, survivorship care planning or medical services. Information and advice about these services and topics are included, such as details on where to find them and the types of services available.

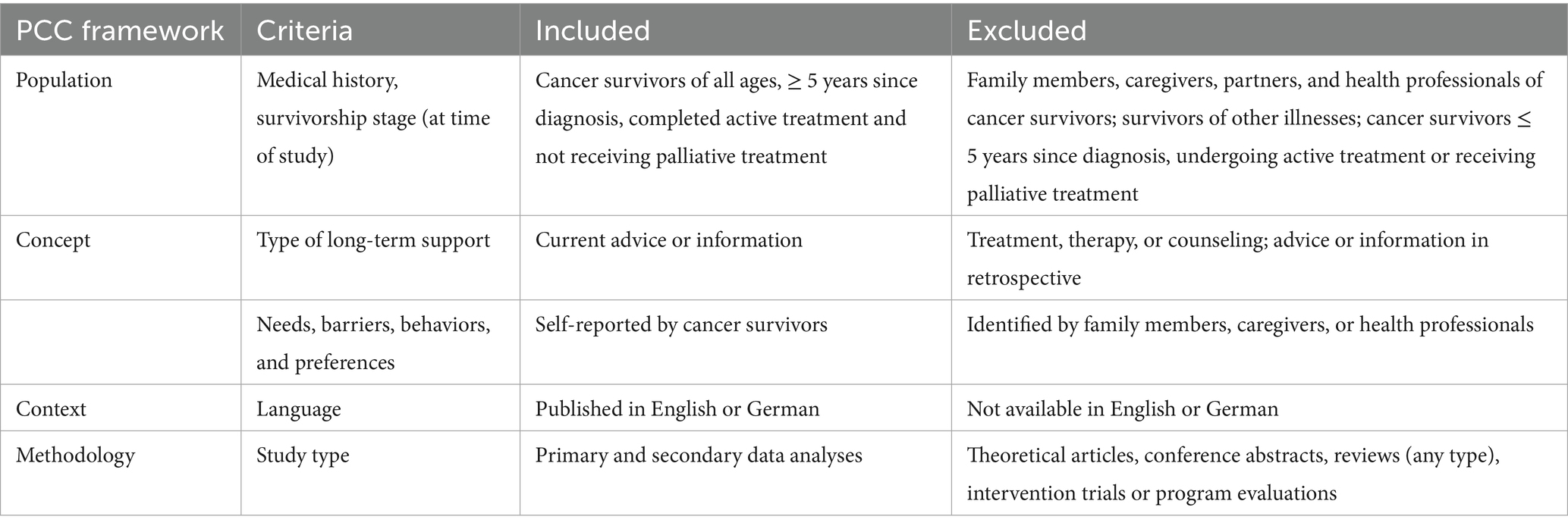

‘Information needs’ were defined as the motivational dispositions, information requests, or expressions of information wanted to have, while ‘preferences’ referred to the formal aspects of information needed, i.e., the type, delivery mode, the portrayal, the way of access, or the time survivors wanted to receive the information. ‘Behavior’ was defined as any action to seek, scan, non-seek, or avoid information or advice self-reported by cancer survivors, and ‘Barriers’ as conditions or characteristics, e.g., sociodemographic ones, to finding and understanding information or advice self-reported by cancer survivors. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for study selection using the Population-Concept-Context (PCC) framework (Peters et al., 2020) are presented in Table 1.

Studies with survivors at different stages of survivorship were included if either long-term survivors (≥5 years since diagnosis) were investigated as a separate group or time since diagnosis was included as an independent or control variable in the analysis.

Studies with cancer survivors participating in trials, programs, or interventions were excluded because the experiences in these programs may not represent both the broader survivorship population due to selection bias and everyday life due to the controlled environment. Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies, including those with primary or secondary data analyses, were included in the review to capture a broad insight into the topic. Searches were limited to empirical journal articles in peer-reviewed journals, in German and in English. No exclusion criteria were applied to geographical location, cancer type, age at diagnosis, and current age of the survivors to scope the breadth of the available literature.

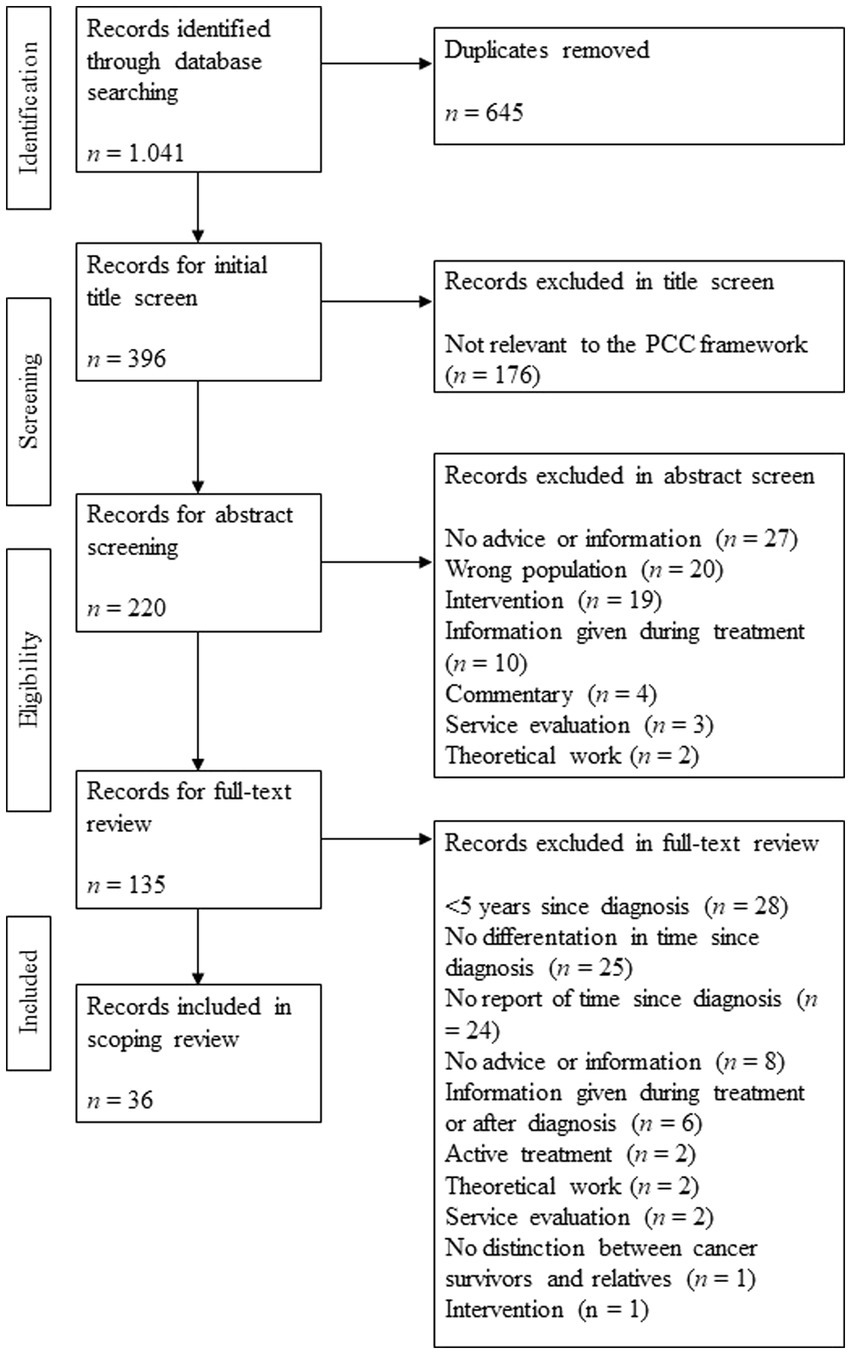

Search results from all five databases were exported into Excel, and duplicates were removed. For the remaining results, a title screening was conducted to match the PCC framework. Screening titles first is more efficient and tends to lead to the same recall as screening titles and abstracts together (Mateen et al., 2013). The remaining articles were researched, and abstracts were screened for population, context, and concept. After excluding the irrelevant studies, the full texts of the remaining articles were searched, downloaded, and screened for eligibility criteria. The process of inclusion and exclusion was conducted by the first author and is presented in the PRISMA Flow Chart (see Figure 1).

2.3 Data extraction and analysis

The following information was extracted and summarized for each study:

Study reference: Author, journal, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, publishing language.

Participants: Type(s) of cancer, age at study (range/mean), life stage at diagnosis (CAYA / non-CAYA), gender, ethnicity, sample size.

Content: Theoretical framework, information needs / barriers / behaviors (seek, non-seek, scan, avoid) / preferences and factors associated with it.

Study design: Qualitative or quantitative, experimental design (yes/no), limitations.

Ethnic groups to describe the studies’ populations were derived from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS; Finney Rutten et al., 2006) and included White, Asian, Hispanic, Black, and Other. Other included Non-White, Non-Hispanic minorities, e.g., Arab migration background or Indigenous background, such as Aboriginal or Alaskan Native. Studies were coded CAYA if they explicitly mentioned childhood or AYA cancers.

Studies were first categorized according to their main topic to answer the research questions: information needs, information seeking and preferences, and information avoidance and barriers. The theoretical models used in the studies were coded openly and then aggregated. Information barriers were analyzed in terms of the CMIS’s characteristics of the media and individual characteristics (Johnson and Meischke, 1993), coded openly and inductively condensed afterward. The categories for information topics were derived from Fletcher et al. (2017) and Johnston et al. (2021). Categories describing the reported information behaviors were based on the UMT (Brashers et al., 2000; Brashers et al., 2002) and extended by Grimm and Baumann’s (2019) summary of cancer-related information behaviors to include cancer information seeking, non-seeking, scanning, and avoiding. Information preferences were coded in terms of the preferred information source, form (e.g., website), and timing of the information.

For all dimensions, associated factors were coded. Derived from the CMIS (Johnson and Meischke, 1993), these included the sociodemographic variables “current age,” “gender,” “race or ethnical background,” “self-reported health status,” “education,” and “income” as well as the cancer-specific factors “type of cancer,” “age at diagnosis,” and “time since diagnosis” as health-related factors. An open category for other factors was included, e.g., for the perceived seeking control and seeking-related subjective norms as proposed by PRISM (Kahlor, 2010). The factors were coded if they were found to be associated with information needs or behaviors of LTCS, and the specific empirical relation was summarized openly. The full code sheet is available in Appendix B.

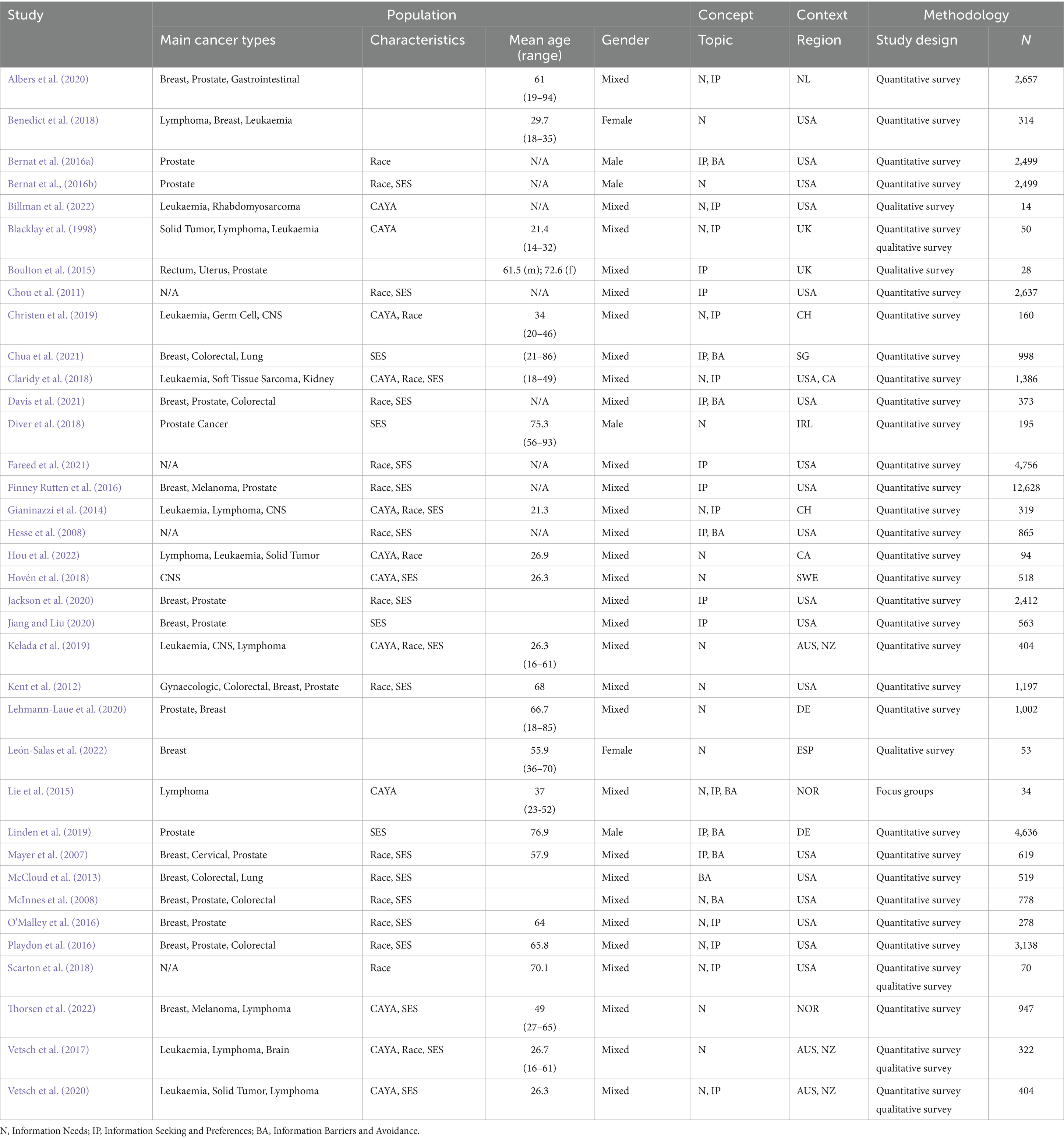

As specified in the PRISMA-ScR, a formal quality assessment of the included studies was not conducted (Tricco et al., 2018). The general characteristics of the included studies were mapped using the PCC framework. An overview of the included articles is presented in Table 2.

3 Results

36 articles were included in the review. The mean sample size of the identified studies was n = 1,399. The mean share of White participants (when reported) was 80.33%, versus 8.70% Black, 8.58% Asian, and 5.97% Hispanic participants. About one-third of the studies did not include information about participants’ ethnic backgrounds (n = 13; 36.11%); seven of these studies focused on CAYA cancer survivors. The mean age of the participants, if reported, was 47 years. Most studies focused on male and female cancer survivors (n = 30), with four studies on male survivors and two on female survivors. Approximately one-third of the studies covered information for CAYA cancer survivors (n = 13). Twenty-one studies did not report on the life stage during which the diagnosis occurred. Studies most frequently included prostate cancer survivors (n = 18) and survivors of breast cancer (n = 17). Studies on CAYA cancer survivors focused most frequently on leukemia and other hematological cancers (n = 10) and Hodgkin’s / Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n = 10). Over half of the studies focused on LTCS residing in the USA or Canada (n = 20), followed by one-third in Europe (n = 12). Most studies were quantitative survey studies (n = 28). Almost all of them were cross-sectional in design and lacked experimental stimuli (n = 35); only one study, by Blacklay et al. (1998), was longitudinal and employed an experimental design. More than half of the studies (n = 20) were published in the five years prior to the search (2018–2022).

3.1 Information needs of LTCS (RQ1)

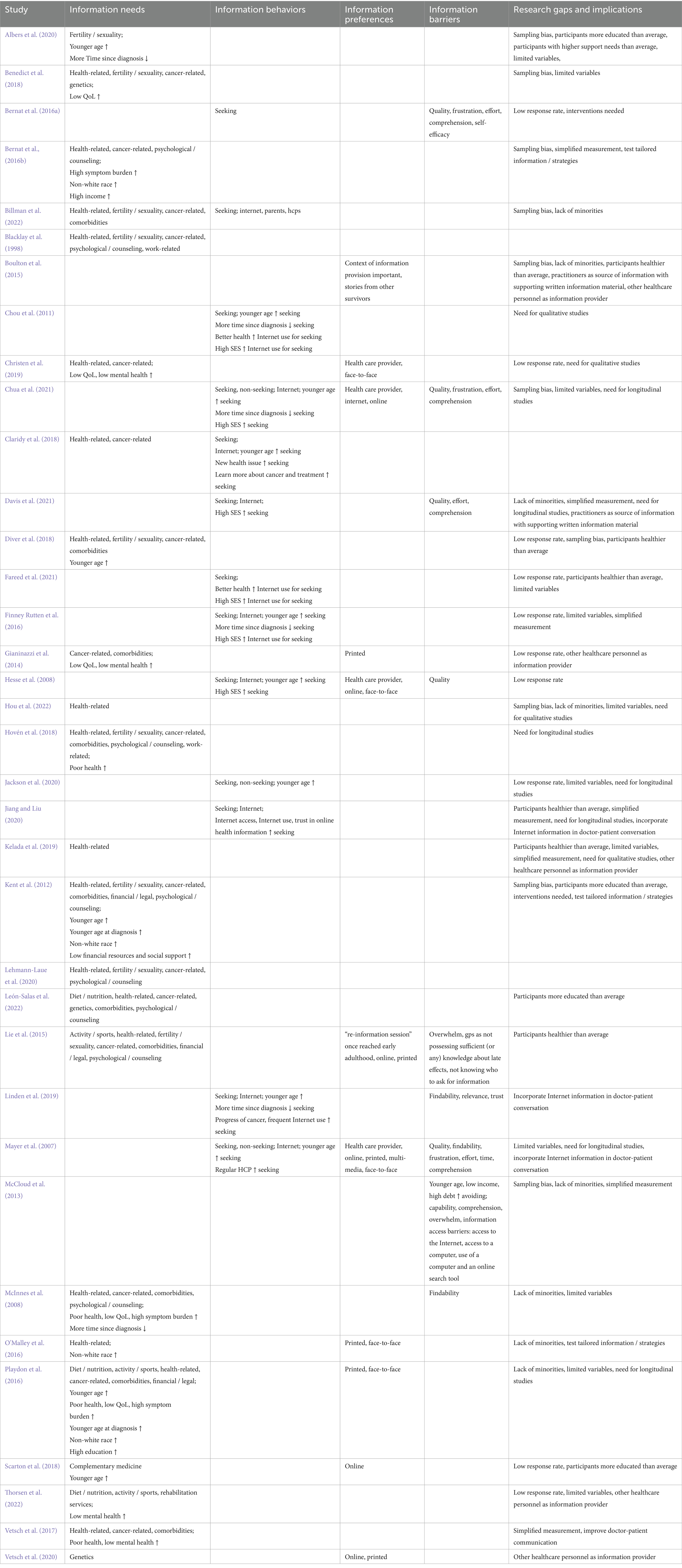

The studies included in the review revealed that LTCS still have unmet information needs, most on general health topics, cancer, and recurrence; comorbidities, and also on genetic risks and testing, fertility and sexuality issues, psychological issues or help, financial issues, diet and nutrition, and sports and activity (McInnes et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2012; Bernat et al., 2016b; O’Malley et al., 2016; Playdon et al., 2016; Benedict et al., 2018; Diver et al., 2018; Scarton et al., 2018; Albers et al., 2020; Lehmann-Laue et al., 2020; León-Salas et al., 2022; see Table 3). Younger survivors tend to have more information needs (Kent et al., 2012; Playdon et al., 2016; Diver et al., 2018; Scarton et al., 2018; Albers et al., 2020; see Table 3). Poorer general health, lower quality of life, higher symptom burden, or mental health problems are associated with greater information needs (McInnes et al., 2008; Bernat et al., 2016b; Playdon et al., 2016; Benedict et al., 2018; Hovén et al., 2018; see Table 3). Survivors diagnosed in earlier years of their lives tend to have more information needs than those diagnosed later in life (Kent et al., 2012; Playdon et al., 2016; see Table 3). Information needs tend to decrease with increasing time since diagnosis or approximately ten years after diagnosis (McInnes et al., 2008; Albers et al., 2020; see Table 3).

3.2 Specific information needs of vulnerable groups (RQ1a, 1b, 1c)

Race. Concerning race, four studies (11.1%) found non-White participants to have greater information needs than White LTCS (Kent et al., 2012; Bernat et al., 2016b; O’Malley et al., 2016; Playdon et al., 2016; see Table 3).

Lower SES. Income was a significant factor in one study (2.78%; Bernat et al., 2016b; see Table 3), with higher income associated with greater information needs. Higher education was found to be associated with greater information needs in one study (2.78%; Playdon et al., 2016; see Table 3), whereas five studies (13.89%) found education not to be significant (McInnes et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2012; Bernat et al., 2016b; O’Malley et al., 2016; Diver et al., 2018). One study found that cancer survivors reporting inadequate financial resources and lower social support were more likely to report health promotion and insurance-related information needs (2.78%; Kent et al., 2012; see Table 3).

CAYA. CAYA LTCS appear to have information needs in similar domains to non-CAYA LTCS in 84.62% of the studies on CAYA (n = 11; Blacklay et al., 1998; Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Lie et al., 2015; Vetsch et al., 2017; Claridy et al., 2018; Hovén et al., 2018; Christen et al., 2019; Kelada et al., 2019; Billman et al., 2022; Hou et al., 2022; Thorsen et al., 2022; see Table 3). Also, worse physical and mental health seems to contribute to greater information needs in 46.15% of the studies on CAYA (Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Vetsch et al., 2017; Hovén et al., 2018; Christen et al., 2019; Vetsch et al., 2020; Thorsen et al., 2022; see Table 3). In contrast to non-CAYA LTCS, current age, age at diagnosis, and time since diagnosis do not appear to be associated with information needs in CAYA cancer survivors, as seven studies (58.33%) reported no associations (Blacklay et al., 1998; Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Vetsch et al., 2017; Hovén et al., 2018; Christen et al., 2019; Kelada et al., 2019; Vetsch et al., 2020; Thorsen et al., 2022).

3.3 Information behaviors and preferences of LTCS (RQ2)

Concerning information behaviors, the studies included in this review mainly reported on the information-seeking or non-seeking behavior of non-CAYA LTCS (see Table 3). Across the studies, the most frequently mentioned source for information seeking was the Internet (Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; Bernat et al., 2016a; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Linden et al., 2019; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021), although some LTCS seemed to prefer receiving information from their healthcare provider instead (Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; Chua et al., 2021; see Table 3). According to the studies, LTCS seek information on general health topics, cancer and recurrence, genetics, sexuality and fertility, and psychological wellbeing (Chou et al., 2011; Bernat et al., 2016a; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Linden et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Fareed et al., 2021; see Table 3). Younger age seems to predict more health information seeking, especially on the Internet (Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; Chou et al., 2011; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Linden et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2020; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Chua et al., 2021; see Table 3). Findings on the association with gender are inconclusive.

Longer time since diagnosis may decrease the likelihood of seeking cancer-related health information in general and on the Internet, and increase the likelihood of being a non-seeker (Chou et al., 2011; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Linden et al., 2019; Chua et al., 2021; see Table 3), but other studies found no relation (Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; McInnes et al., 2008; McCloud et al., 2013; Claridy et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2020; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Davis et al., 2021; Fareed et al., 2021). Concerning general health status, two studies reported that survivors with better health were more likely to use the Internet (Chou et al., 2011; Fareed et al., 2021; see Table 3). Two studies found no relation between information-seeking and health status (Mayer et al., 2007; Jiang and Liu, 2020). Other studies did not report on the relationship between health status and information seeking.

Other factors increasing the likelihood of information-seeking behavior are the progress of the cancer and frequent Internet use (Linden et al., 2019; see Table 3). Internet access, health-related Internet use, and trust in online health information were also found to be associated with more information seeking on the Internet (Jiang and Liu, 2020; see Table 3).

LTCS described being too preoccupied during the diagnosis and treatment phase to process information on long-term effects (Boulton et al., 2015; see Table 3). In long-term survivorship, they prefer receiving personalized information in written or multimedia formats, including medical information and stories from other survivors, but also want to get information from their healthcare provider, preferably in a supportive setting (Mayer et al., 2007; Boulton et al., 2015; Playdon et al., 2016; Christen et al., 2019; see Table 3).

As motivation for seeking health information, survivors mentioned medical reasons like being diagnosed with a new health problem, unanswered questions after a visit to the doctor or clinic, being prescribed a new treatment, test, or medication, and having a medical condition, like high blood pressure or diabetes (Claridy et al., 2018; see Table 3). On top of that, learning more about the effects of the treatment they received, seeing or hearing something on the news they wanted to learn more about, and wanting to change their diet or activity habits were motivators to seek health-related information (Claridy et al., 2018; see Table 3).

3.4 Specific information behaviors and preferences of vulnerable groups (RQ2a, 2b, 2c)

Race, lower SES. While information seeking in general or on the Internet was not a predicted by race in any study where it was controlled (n = 5; 13.89%; Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Jackson et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2021), a higher socioeconomic status, meaning higher income and education, appeared in 19.44% of the studies to be positively associated with health information seeking in general (Hesse et al., 2008; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; see Table 3) and on the Internet (Chou et al., 2011; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Fareed et al., 2021; see Table 3).

However, 13.89% of the studies found no difference in education (Mayer et al., 2007; Linden et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020) and income (Hesse et al., 2008; Jiang and Liu, 2020). Further factors increasing the likelihood of information-seeking behaviors are having a regular healthcare provider (Mayer et al., 2007; see Table 3), having a job, and private housing (Chua et al., 2021; see Table 3). None of the identified studies analyzed specific information preferences of Non-White and ethnic minority LTCS and LTCS with lower SES.

CAYA. Studies on the information behaviors of CAYA LTCS were sparse. Besides turning to their parents and healthcare providers, CAYA survivors seem to use the Internet to seek information and are more likely to do so if they are younger, higher educated and have poorer general health status (Claridy et al., 2018; Billman et al., 2022; see Table 3). They seek information on general health, cancer and recurrence, and comorbidities (Claridy et al., 2018; Billman et al., 2022; see Table 3). Especially CAYA cancer survivors reported limited knowledge of their cancer treatments, which leaves them unprepared to manage their health in survivorship (Billman et al., 2022). They prefer written information in a personalized form, consider receiving a refreshment of information once they reach adulthood as useful, and like to have information available continuously (Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Lie et al., 2015; Christen et al., 2019; Vetsch et al., 2020; see Table 3).

3.5 Information barriers and information avoiding behaviors of LTCS (RQ3)

According to the literature under study, information barriers of LTCS can be categorized into personal barriers and informational barriers. On the individual side, missing time and difficulties in finding information (including technical access), frustration while searching for it, difficulties in assessing the information’s quality, understanding it, trusting it, and missing health-related self-efficacy were found to be barriers to information seeking (Mayer et al., 2007; McInnes et al., 2008; McCloud et al., 2013; Bernat et al., 2016b; Linden et al., 2019; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; see Table 3). On the information side, the (perceived) quality and relevance of the information, the sheer volume of it on the Internet and the effort to find it were barriers to successful information seeking and satisfying information needs (Mayer et al., 2007; Hesse et al., 2008; Bernat et al., 2016b; Linden et al., 2019; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; see Table 3).

3.6 Specific information barriers and information avoiding behaviors of vulnerable groups (RQ3a, 3b, 3c)

Race. There were no reports on information barriers and avoidance behaviors of non-White or ethnic minority LTCS.

Lower SES. One study found information avoiders are more likely to be female, with higher debt, lower income, and aged under 50 years (McCloud et al., 2013). Younger men also showed a tendency to avoid information in one study, where a lower education level increased the likelihood of information avoidance (McCloud et al., 2013). One study found that lower income and lower health information-seeking self-efficacy were associated with more negative information-seeking experiences (Bernat et al., 2016a). The feeling that information was too hard to understand increased with lower levels of education (Bernat et al., 2016a).

CAYA. CAYA cancer survivors reported that the resources available to them fall short of their information needs (Billman et al., 2022). A barrier to adequate health information on their side is the uncertainty about who to ask and where to look, and the ability to judge whether information is relevant to them (Lie et al., 2015; see Table 3). On the information side, the sheer volume of information available on the Internet was reported as a barrier (Lie et al., 2015; see Table 3). On top of that, CAYA cancer survivors tend not to trust their general health provider and oncologist to possess sufficient knowledge of cancer long-term and late effects (Lie et al., 2015; see Table 3). When contacting their oncologist, CAYA survivors felt the oncologist would be too busy to be bothered with their ‘minor’ worries or that their illness would be too long ago for the oncologist to be the right person to approach (Lie et al., 2015).

3.7 Theoretical models used to explain information seeking and avoiding in LTCS (RQ4)

Only five studies (13.89%) were based on a theoretical model. Two studies used Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory (McInnes et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2012). One (McCloud et al., 2013) used Uncertainty Management Theory and the Structural Influence Model (Viswanath et al., 2007), another derived their interview questions from the Health Belief Model and Uses and Gratifications Theory (Scarton et al., 2018). Another one used the CMIS to model their study (Mayer et al., 2007).

3.8 Research gaps and implications for future research (RQ5)

Limitations acknowledged by the authors included recruiting participants from single institutions, e.g., cancer groups or centers, and low response rates (Hesse et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2012; McCloud et al., 2013; Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Boulton et al., 2015; Bernat et al., 2016a; Bernat et al., 2016b; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Benedict et al., 2018; Diver et al., 2018; Scarton et al., 2018; Christen et al., 2019; Albers et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Chua et al., 2021; Fareed et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2022; Thorsen et al., 2022; see Table 3). In addition, several authors reported a lack of representation of minorities in the participants (McInnes et al., 2008; McCloud et al., 2013; Boulton et al., 2015; O’Malley et al., 2016; Playdon et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2021; Billman et al., 2022; Hou et al., 2022; see Table 3).

Participants of the studies were more educated than cancer survivors in general (Kent et al., 2012; Scarton et al., 2018; Albers et al., 2020; León-Salas et al., 2022; see Table 3), and expected to be either healthier than the population (Boulton et al., 2015; Lie et al., 2015; Diver et al., 2018; Kelada et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Fareed et al., 2021; see Table 3), or with higher physical burdens (Albers et al., 2020). Several studies could not explain all relevant relationships because they included only a limited number of variables, especially considering factors contributing to health information needs and behaviors (Mayer et al., 2007; McInnes et al., 2008; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Playdon et al., 2016; Benedict et al., 2018; Kelada et al., 2019; Albers et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Chua et al., 2021; Fareed et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2022; Thorsen et al., 2022; see Table 3). Limited explanatory power was also reported as a limitation by the authors due to measuring complex phenomena with simplified items (McCloud et al., 2013; Bernat et al., 2016b; Finney Rutten et al., 2016; Vetsch et al., 2017; Kelada et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Davis et al., 2021; see Table 3).

Several studies gave recommendations, addressing the need for qualitative studies to gain in-depth insights into information needs and behaviors, and longitudinal studies to analyze the changes over time and in relation to different cancer survivorship states (Mayer et al., 2007; Chou et al., 2011; Playdon et al., 2016; Christen et al., 2019; Kelada et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2020; Jiang and Liu, 2020; Chua et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2022; see Table 3). Interventions to assess the effectiveness of tailored information and individual care plans were also recommended (Kent et al., 2012; Bernat et al., 2016a; Bernat et al., 2016b; O’Malley et al., 2016; see Table 3).

The studies recommended practical improvements in doctor-patient interaction. The importance of both the practitioners as a source of information, supporting written information material, and providing information in a personal conversation was underlined (Boulton et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2021; see Table 3). Some studies recommended incorporating information on the Internet in the doctor-patient conversation, e.g., doctors should encourage patients to seek information online and educate them on how to find reliable information, and doctors should better prepare for conversations with Internet-informed patients (Mayer et al., 2007; Linden et al., 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2020; see Table 3). Other studies also recommended that other healthcare personnel provide information to LTCS to relieve the workload from doctors (Gianinazzi et al., 2014; Boulton et al., 2015; Kelada et al., 2019; Vetsch et al., 2020; Thorsen et al., 2022; see Table 3).

4 Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive synthesis of the current knowledge on the information needs and behaviors of long-term cancer survivors. The findings indicate that, across multiple topics, LTCS still report significant unmet information needs. This supports prior research suggesting that survivors experience persistent uncertainty regarding their illness and its long-term effects, which drives their need for information (Mishel, 1990; Ferrell et al., 1998; Brashers et al., 2000; McKinley, 2000; O’Hair et al., 2003; O’Hair et al., 2008; Thompson and O’Hair, 2008). However, consistent with Mistry et al. (2010), information needs tend to decrease over time since diagnosis, suggesting that survivors either learn to manage their late effects or adapt to them.

The need for information on palliative and end-of-life care was not reported in the studies. However, studies on survivors receiving palliative care were excluded, which could explain this result. To identify and meet all LTCS’ information needs, which include those in end-of-life care, future studies should consider this group as well.

A key finding of this review is the disparity in information needs among ethnic minority LTCS. While racial differences did not predict information-seeking behaviors, non-White survivors consistently reported greater and more information needs than White survivors. This may indicate deficiencies in culturally sensitive aftercare, racial disparities in follow-up care, or ineffective communication strategies (Butler et al., 2020). The lack of studies on information barriers and preferences by race further highlights a research gap. Understanding why ethnic minority survivors’ information needs remain unmet, despite comparable information-seeking behaviors, is critical. Future qualitative research could explore the role of language barriers, cultural insensitivity, and biases within the healthcare system in shaping access to and perception of information. To achieve this, it is recommended to recruit more diverse study populations to better understand racial disparities in survivorship care and information provision. For practical implications, culturally sensitive, multilingual information materials for ethnic minority survivors should be developed.

The findings also suggest that worse health status, higher symptom burden, and greater psychological distress are associated with increased information needs. However, most studies did not assess participants’ health status in detail. Research on childhood, adolescent, and young adult (CAYA) cancer survivors, however, explicitly links poor health to more frequent information-seeking behavior (Claridy et al., 2018). Given that health status is a known moderator of health information-seeking behaviors (Link and Baumann, 2022b), future research should examine this relationship more systematically.

Several identified information barriers align with factors outlined in the CMIS (Johnson and Meischke, 1993) and the PRISM (Kahlor, 2010). These barriers can be categorized into (1) information-related barriers, such as accessibility, discoverability, and trustworthiness of information, and (2) individual-level barriers, such as survivors’ ability to interpret medical information or personal confidence in processing it. Ensuring that health information is accessible, clearly communicated, and tailored to the needs of LTCS is essential. Socioeconomic status (SES) also plays a role in information behaviors. Higher SES is associated with greater information-seeking, whereas lower education, higher debt, and lower income are linked to information avoidance (McCloud et al., 2013). While this pattern is consistent with prior research (Ramanadhan and Viswanath, 2006; Chae, 2016; Nelissen et al., 2017; Chae et al., 2020; Link and Baumann, 2022b), findings regarding age and gender differences in information avoidance remain inconclusive (Link and Baumann, 2022b). Given the potential health risks associated with avoiding information, future research should further investigate these disparities through systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To address socioeconomic disparities in information access, targeted and discoverable information materials with accessible language for lower SES survivors should be designed. Information should also be provided in multimedia formats (e.g., videos, mobile apps) to accommodate different literacy levels.

A critical barrier is low trust in information and health-related self-efficacy, both of which contribute to information avoidance (Link and Baumann, 2022b). The review emphasizes the importance of empowering survivors by enhancing their self-efficacy and promoting trust in credible information sources. To achieve that, survivors should be educated on evaluating trustworthy online health information through structured guidance or workshops. Healthcare providers could be encouraged to discuss reliable online resources with patients.

A particularly understudied group is CAYA cancer survivors, who often lack sufficient knowledge about their treatments and long-term health management. Since many were too young to fully understand their initial diagnosis, follow-up education in adulthood could be an effective intervention. To tailor information to their needs, structured “re-information sessions” in adulthood should be offered to help CAYA survivors make informed health decisions. Digital tools providing continuous access to relevant health information could also be developed.

The growing reliance on the internet for health information suggests dissatisfaction with the information provided by healthcare professionals (Soothill et al., 2001; Harrison et al., 2011; Hoekstra et al., 2014). However, preferences vary, with some survivors still preferring traditional formats, such as face-to-face consultations or printed materials. Future research should explore how to balance digital and offline resources. One solution to optimize doctor-patient interaction is to train healthcare professionals to communicate effectively with internet-informed patients, addressing concerns while reinforcing trust in professional medical advice. They could also provide print materials and personalized online materials in healthcare settings. Additionally, incorporating patient experiences into educational materials could enhance engagement while ensuring that information remains transparent and manageable. To determine whether new information offers are required or if existing ones need adjustments, the accessibility, discoverability, and quality of existing online health resources for LTCS should be evaluated.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can offer promising solutions to address information gaps among LTCS. AI-powered platforms can provide personalized, on-demand health information based on each individual’s medical history, treatment journey, and symptom profiles (Talyshinskii et al., 2024; Riaz et al., 2025). These systems can suggest credible sources, translate medical jargon into plain language, and offer multilingual content tailored to the survivor’s cultural and linguistic background (Lawson McLean and Yen, 2024; Schmiedmayer et al., 2025; Rodler et al., 2025). AI-driven chatbots and virtual health assistants can offer ongoing support, answer questions, and help survivors navigate complex health information, which is especially helpful for those with lower health literacy or limited access to healthcare providers (Wang et al., 2023; Schmiedmayer et al., 2025). Additionally, AI can analyze patterns in survivors’ information-seeking behaviors to identify unmet needs in real time, enabling adaptive information delivery (Benetka et al., 2017). However, ethical issues such as privacy, algorithmic bias, and transparency need to be addressed to ensure AI technologies are inclusive, fair, and trustworthy (Lawson McLean and Hristidis, 2025). Incorporating AI into survivorship care could reduce information disparities and foster independence among diverse survivor groups while also reducing the workload on healthcare providers.

Finally, this review reveals a lack of theoretical grounding in many studies, with few applying established models, such as PRISM. Given its emphasis on cognitive, emotional, and social factors, PRISM could provide deeper insights into both information-seeking and avoidance behaviors among LTCS. A stronger theoretical framework would help clarify inconsistencies and guide the development of more effective health communication strategies. For example, conducting research using PRISM helps better to understand long-term information-seeking and avoidance behaviors beyond sociodemographic factors.

By addressing these challenges, healthcare systems and researchers can move toward a more inclusive, accessible, and survivor-centered approach to health communication.

4.1 Limitations

This scoping review offers valuable insights into the information needs and behaviors of long-term cancer survivors, thereby extending social science research on health by examining this vulnerable group. However, the findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. A broad search strategy was employed to search the title section of databases; therefore, the included studies may not fully represent the current knowledge on long-term cancer survivors. Future research could consider a librarian or information specialist to develop the search string further. The first author conducted both the development of the search string and the screening process. Although inclusion and exclusion decisions were carefully evaluated based on the specified criteria and documented in detail, they still may have been biased. Studies from different regions were included in this review, with no regard to the cultural and systemic differences of the countries, e.g., in terms of health insurance and healthcare systems. Although information needs and behaviors can be observed in LTCS in general, the medical supply situation in the respective region can also impact needs, behaviors, and barriers. A comparison of national healthcare systems and supply situations, along with a subsequent interpretation of the findings within this context, is needed.

Furthermore, both quantitative and qualitative studies were included and treated as equally important, with no regard to sample size, recruitment method, or bias. This could over- or underestimate reported findings. This scoping review can only provide an overview of the existing literature in a systematic manner, without regard to the quality of the studies or analyzing the findings in relation to a meta-analysis. Since only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included, they should generally meet research standards. Biased samples, such as those recruited only from members of cancer support groups, have been reported in the included studies and were not addressed in this review. A review with a subsequent meta-analysis could provide insight into the differing findings, especially regarding factors predicting LTCS’ information behavior, and consider effect sizes to minimize the over- or underestimation of findings.

5 Conclusion

This scoping review identified that LTCS still have unmet information needs in their long-term survivorship, are mainly active information seekers, aiming to satisfy their information needs, but also, in some cases, avoid distressing information, especially those with lower SES. They experience barriers to obtaining and processing information on both the individual and information sides, may be unsatisfied with the information provided by their healthcare provider, and feel overwhelmed by health information on the Internet, which they may not understand or trust. The information behavior of CAYA LTCS and the barriers to information faced by LTCS from ethnic minorities need to be investigated further. LTCS’ preferences on how, when and where they want to receive information give guidance to medical personnel and health communicators on how to design information tailored to their needs. However, the information needs of LTCS are not adequately met by simply publishing information on the Internet. Cooperation is needed between healthcare providers who know their patients and build a trustworthy relationship with them, support groups that empower them, and information offerings from federal institutions that educate them in a trustworthy environment. If specific questions like the barriers, information avoidance, and information preferences of ethnic minorities and CAYA cancer survivors are considered in the future, a guideline on how to reach these long-term cancer survivors with information tailored to their needs can be developed. With this, we are one step closer to providing long-term cancer survivors with appropriate long-term care.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/5p9d6/overview?view_only=9d0d8af759b54049a09b5ebc1a2e7783.

Author contributions

EH: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. EB: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology. VG: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. FSS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. UD: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health – 1504-54401 “Optimales Langzeitüberleben nach Krebs (OPTILATER) (Optimum long-term survival after cancer)” – Funding Code 2522FSB01B.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1624452/full#supplementary-material

References

Adler, N. E., and Rehkopf, D. H. (2008). U.S. disparities in health: descriptions, causes, and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Public Health 29, 235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852

Albers, L. F., van Belzen, M. A., van Batenburg, C., Engelen, V., Putter, H., Pelger, R. C. M., et al. (2020). Discussing sexuality in cancer care: towards personalized information for cancer patients and survivors. Supp. Cancer Off. J. Multinational Assoc. Supportive Care Cancer 28, 4227–4233. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05257-3

Arndt, V., Koch-Gallenkamp, L., Jansen, L., Bertram, H., Eberle, A., Holleczek, B., et al. (2017). Quality of life in long-term and very long-term cancer survivors versus population controls in Germany. Acta Oncologica 56, 190–197. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266089

Arora, N. K., Hesse, B. W., Rimer, B. K., Viswanath, K., Clayman, M. L., and Croyle, R. T. (2008). Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 223–228. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0406-y

Aziz, N. M., and Rowland, J. H. (2002). Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 29, 789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801

Benedict, C., Thom, B., Friedman, D. N., Pottenger, E., Raghunathan, N., and Kelvin, J. F. (2018). Fertility information needs and concerns post-treatment contribute to lowered quality of life among young adult female cancer survivors. Supp. Cancer Off. J. Multinational Assoc. Supp. Care Cancer 26, 2209–2215. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-4006-z

Benetka, J. R., Balog, K., and Nørvåg, K. (2017). “Anticipating information needs based on check-in activity,” In M. de Rijke (Ed.), ACM Digital Library, Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (41–50). doi: 10.1145/3018661.3018679

Bergelt, C., Bokemeyer, C., Hilgendorf, I., Langer, T., Rick, O., Seifart, U., et al. (2022). Langzeitüberleben bei Krebs: Definitionen, Konzepte und Gestaltungsprinzipien von survivorship-Programmen [long-term survival in cancer: definitions, concepts, and design principles of survivorship programs]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 65, 406–411. doi: 10.1007/s00103-022-03518-x

Bernat, J. K., Skolarus, T. A., Hawley, S. T., Haggstrom, D. A., Darwish-Yassine, M., and Wittmann, D. A. (2016a). Negative information-seeking experiences of long-term prostate cancer survivors. J. Cancer Survivorship Res. Practice 10, 1089–1095. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0552-5

Bernat, J. K., Wittman, D. A., Hawley, S. T., Hamstra, D. A., Helfand, A. M., Haggstrom, D. A., et al. (2016b). Symptom burden and information needs in prostate cancer survivors: a case for tailored long-term survivorship care. BJU Int. 118, 372–378. doi: 10.1111/bju.13329

Billman, E., Smith, S. M., and Jain, S. L. (2022). Perspectives of childhood Cancer survivors as young adults: a qualitative study of illness education resources and unmet information needs. J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Education 9:2240. doi: 10.1007/s13187-022-02240-1

Blacklay, A., Eiser, C., and Ellis, A. (1998). Development and evaluation of an information booklet for adult survivors of cancer in childhood. The United Kingdom children’s Cancer study group late effects group. Arch. Dis. Child. 78, 340–344. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.4.340

Boulton, M., Adams, E., Horne, A., Durrant, L., Rose, P., and Watson, E. (2015). A qualitative study of cancer survivors’ responses to information on the long-term and late effects of pelvic radiotherapy 1-11 years post treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Care 24, 734–747. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12356

Brashers, D. E. (2001). Communication and uncertainty management. J. Commun. 51, 477–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2001.tb02892.x

Brashers, D. E., Goldsmith, D. J., and Hsieh, E. (2002). Information seeking and avoiding in health contexts. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 258–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00807.x

Brashers, D. E., Neidig, J. L., Haas, S. M., Dobbs, L. K., Cardillo, L. W., and Russell, J. A. (2000). Communication in the management of uncertainty: the case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. Commun. Monogr. 67, 63–84. doi: 10.1080/03637750009376495

Braveman, P., and Tarimo, E. (2002). Social inequalities in health within countries: not only an issue for affluent nations. Soc. Sci. Med. 54, 1621–1635. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00331-8

Butler, S. S., Winkfield, K. M., Ahn, C., Song, Z., Dee, E. C., Mahal, B. A., et al. (2020). Racial disparities in patient-reported measures of physician cultural competency among Cancer survivors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 6, 152–154. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4720

Byrne, J., Schmidtmann, I., Rashid, H., Hagberg, O., Bagnasco, F., Bardi, E., et al. (2022). Impact of era of diagnosis on cause-specific late mortality among 77 423 five-year European survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the PanCareSurFup consortium. Int. J. Cancer 150, 406–419. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33817

Chae, J. (2016). Who avoids Cancer information? Examining a psychological process leading to Cancer information avoidance. J. Health Commun. 21, 837–844. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2016.1177144

Chae, J., Lee, C.-J., and Kim, K. (2020). Prevalence, predictors, and psychosocial mechanism of Cancer information avoidance: findings from a National Survey of U.S. adults. Health Commun. 35, 322–330. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1563028

Chou, W.-Y. S., Liu, B., Post, S., and Hesse, B. (2011). Health-related internet use among cancer survivors: data from the health information National Trends Survey, 2003-2008. J. Cancer Survivorship Res. Prac. 5, 263–270. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0179-5

Christen, S., Weishaupt, E., Vetsch, J., Rueegg, C. S., Mader, L., Dehler, S., et al. (2019). Perceived information provision and information needs in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Eur. J. Cancer Care 28:e12892. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12892

Chua, G. P., Ng, Q. S., Tan, H. K., and Ong, W. S. (2021). Cancer survivors: what are their information seeking Behaviours? J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Education 36, 1237–1247. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01756-8

Claridy, M. D., Hudson, M. M., Caplan, L., Mitby, P. A., Leisenring, W., Smith, S. A., et al. (2018). Patterns of internet-based health information seeking in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 65:e26954. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26954

Davies, A., Dégi, C. L., and Aapro, M. (2020). Free from Cancer: achieving quality of life for all Cancer patients and survivors. Brussels. Available online at: https://www.europeancancer.org/resources/166:free-from-cancer-achieving-quality-of-life-for-all-cancer-patients-and-survivors.html (accessed May 5, 2023).

Davis, S. N., O’Malley, D. M., Bator, A., Ohman-Strickland, P., and Hudson, S. V. (2021). Correlates of information seeking behaviors and experiences among adult Cancer survivors in the USA. J. Cancer Educ. Off. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 36, 1253–1260. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01758-6

Diver, S., Avalos, G., Rogers, E. T., and Dowling, M. (2018). The long-term quality of life and information needs of prostate cancer survivors. Int. J. Urol. Nurs. 12, 16–26. doi: 10.1111/ijun.12156

Emanuel, A. S., Kiviniemi, M. T., Howell, J. L., Hay, J. L., Waters, E. A., Orom, H., et al. (2015). Avoiding cancer risk information. Soc. Sci. Med. 147, 113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.058

Fareed, N., Swoboda, C. M., Jonnalagadda, P., and Huerta, T. R. (2021). Persistent digital divide in health-related internet use among cancer survivors: findings from the health information National Trends Survey, 2003-2018. J. Cancer Survivorship Res. Prac. 15, 87–98. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00913-8

Ferrell, B. R., Grant, M., Funk, B., Otis-Green, S., and Garcia, N. (1998). Quality of life in breast cancer. Part II: psychological and spiritual well-being. Cancer Nurs. 21, 1–9. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199802000-00001

Finney Rutten, L. J., Agunwamba, A. A., Wilson, P., Chawla, N., Vieux, S., Blanch-Hartigan, D., et al. (2016). Cancer-related information seeking among Cancer survivors: trends over a decade (2003-2013). J. Cancer Educ. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Educ. 31, 348–357. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0802-7

Finney Rutten, L. J., Squiers, L., and Hesse, B. (2006). Cancer-related information seeking: hints from the 2003 health information National Trends Survey (HINTS). J. Health Commun. 11, 147–156. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637574

Fletcher, C., Flight, I., Chapman, J., Fennell, K., and Wilson, C. (2017). The information needs of adult cancer survivors across the cancer continuum: a scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 100, 383–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.008

Fosså, S. D., Loge, J. H., and Dahl, A. A. (2008). Long-term survivorship after cancer: how far have we come? Annals Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 19, v25–v29. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn305

Gianinazzi, M. E., Essig, S., Rueegg, C. S., von der Weid, N. X., Brazzola, P., Kuehni, C. E., et al. (2014). Information provision and information needs in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 61, 312–318. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24762

Gill, K. M., Mishel, M., Belyea, M., Germino, B., Germino, L. S., Porter, L., et al. (2004). Triggers of uncertainty about recurrence and long-term treatment side effects in older African American and Caucasian breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 31, 633–639. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.633-639

Grimm, M., and Baumann, E. (2019). “Mediale Kommunikation im Kontext von Krebserkrankungen” in Handbuch der Gesundheitskommunikation [handbook of health communication]. eds. C. Rossmann and M. R. Hastall (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 555–566.

Grossi, M. (1998). Management and long-term complications of pediatric cancer. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 45, 1637–1658. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70106-1

Harrison, S. E., Watson, E. K., Ward, A. M., Khan, N. F., Turner, D., Adams, E., et al. (2011). Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: a questionnaire survey. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2091–2098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5167

Hesse, B. W., Arora, N. K., Burke Beckjord, E., and Finney Rutten, L. J. (2008). Information support for cancer survivors. Cancer 112, 2529–2540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23445

Hoekstra, R. A., Heins, M. J., and Korevaar, J. C. (2014). Health care needs of cancer survivors in general practice: a systematic review. BMC Fam. Pract. 15:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-94

Holm, L. V., Hansen, D. G., Larsen, P. V., Johansen, C., Vedsted, P., Bergholdt, S. H., et al. (2013). Social inequality in cancer rehabilitation: a population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 52, 410–422. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.745014

Hou, S. H. J., Tran, A., Cho, S., Forbes, C., Forster, V. J., Stokoe, M., et al. (2022). The perceived impact of COVID-19 on the mental health status of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood Cancer and the development of a knowledge translation tool to support their information needs. Front. Psychol. 13:867151. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.867151

Hovén, E., Lannering, B., Gustafsson, G., and Boman, K. K. (2018). Information needs of survivors and families after childhood CNS tumor treatment: a population-based study. Acta Oncologica 57, 649–657. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1406136

Hovick, S. R., Kahlor, L., and Liang, M.-C. (2014). Personal cancer knowledge and information seeking through PRISM: the planned risk information seeking model. J. Health Commun. 19, 511–527. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.821556

Jackson, I., Osaghae, I., Ananaba, N., Etuk, A., Jackson, N., and G Chido-Amajuoyi, O. (2020). Sources of health information among U.S. cancer survivors: results from the health information national trends survey (HINTS). AIMS Public Health 7, 363–379. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2020031

Jiang, S., and Liu, P. L. (2020). Digital divide and internet health information seeking among cancer survivors: a trend analysis from 2011 to 2017. Psycho-Oncology 29, 61–67. doi: 10.1002/pon.5247

Johnson, J., and Meischke, H. (1993). A comprehensive model of Cancer-related information seeking applied to magazines. Hum. Commun. Res. 19, 343–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1993.tb00305.x

Johnston, E. A., van der Pols, J. C., and Ekberg, S. (2021). Needs, preferences, and experiences of adult cancer survivors in accessing dietary information post-treatment: a scoping review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 30:e13381. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13381

Kahlor, L. (2010). PRISM: a planned risk information seeking model. Health Commun. 25, 345–356. doi: 10.1080/10410231003775172

Kelada, L., Wakefield, C. E., Heathcote, L. C., Jaaniste, T., Signorelli, C., Fardell, J. E., et al. (2019). Perceived cancer-related pain and fatigue, information needs, and fear of cancer recurrence among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 102, 2270–2278. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.022

Kent, E. E., Arora, N. K., Rowland, J. H., Bellizzi, K. M., Forsythe, L. P., Hamilton, A. S., et al. (2012). Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long-term cancer survivors. Patient Educ. Couns. 89, 345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.014

Kessels, R. P. C. (2003). Patients’ memory for medical information. J. R. Soc. Med. 96, 219–222. doi: 10.1177/014107680309600504

Lawson McLean, A., and Hristidis, V. (2025). Evidence-based analysis of AI Chatbots in oncology patient education: implications for trust, perceived realness, and misinformation management. J. Cancer Educ. 40, 482–489. doi: 10.1007/s13187-025-02592-4

Lawson McLean, A., and Yen, T. L. (2024). Machine translation for multilingual Cancer patient education: bridging languages, navigating challenges. J. Cancer Educ. 39, 477–478. doi: 10.1007/s13187-024-02438-5

Lee, C.-J., Ramírez, A. S., Lewis, N., Gray, S. W., and Hornik, R. C. (2012). Looking beyond the internet: examining socioeconomic inequalities in cancer information seeking among cancer patients. Health Commun. 27, 806–817. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.647621

Lehmann-Laue, A., Ernst, J., Mehnert, A., Taubenheim, S., Lordick, F., Götze, H., et al. (2020). Bedürfnisse nach information und Unterstützung bei Krebspatienten: ein Kohortenvergleich von Langzeitüberlebenden fünf und zehn Jahre nach einer Krebsdiagnose [supportive care and information needs of Cancer survivors: a comparison of two cohorts of Longterm cancers survivors 5 and 10 years after primary Cancer diagnosis]. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 70, 130–137. doi: 10.1055/a-0959-5834

León-Salas, B., Álvarez-Pérez, Y., Ramos-García, V., del Mar Trujillo-Martín, M., de Pascual Y Medina, A. M., Esteva, M., et al. (2022). Information needs and research priorities in long-term survivorship of breast cancer: patients and health professionals’ perspectives. Eur. J. Cancer Care 31:e13730. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13730

Lie, H. C., Loge, J. H., Fosså, S. D., Hamre, H. M., Hess, S. L., Mellblom, A. V., et al. (2015). Providing information about late effects after childhood cancer: lymphoma survivors’ preferences for what, how and when. Patient Educ. Couns. 98, 604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.01.016

Linden, A. J., Dinkel, A., Schiele, S., Meissner, V. H., Gschwend, J. E., and Herkommer, K. (2019). Internetnutzung nach Prostatakrebs: Informationssuche und Vertrauen in erkrankungsrelevante Informationen bei Langzeitüberlebenden [internet use after prostate cancer: information search and trust in disease-related information among long-term survivors]. Der Urologe Ausg. A 58, 1039–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00120-019-0966-6

Link, E., and Baumann, E. (2022a). Efficacy assessments as predictors of uncertainty preferences. Eur. J. Health Psychol. 29, 134–144. doi: 10.1027/2512-8442/a000092

Link, E., and Baumann, E. (2022b). Explaining cancer information avoidance comparing people with and without cancer experience in the family. Psycho-Oncology 31, 442–449. doi: 10.1002/pon.5826

Maddock, C., Lewis, I., Ahmad, K., and Sullivan, R. (2011). Online information needs of cancer patients and their organizations. Ecancermedicalscience 5:235. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2011.235

Mateen, F. J., Oh, J., Tergas, A. I., Bhayani, N. H., and Kamdar, B. B. (2013). Titles versus titles and abstracts for initial screening of articles for systematic reviews. Clin. Epidemiol. 5, 89–95. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S43118

Mayer, D. K., Terrin, N. C., Kreps, G. L., Menon, U., McCance, K., Parsons, S. K., et al. (2007). Cancer survivors information seeking behaviors: a comparison of survivors who do and do not seek information about cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 65, 342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.015

McCloud, R. F., Jung, M., Gray, S. W., and Viswanath, K. (2013). Class, race and ethnicity and information avoidance among cancer survivors. Br. J. Cancer 108, 1949–1956. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.182

McInnes, D. K., Cleary, P. D., Stein, K. D., Ding, L., Mehta, C. C., and Ayanian, J. Z. (2008). Perceptions of cancer-related information among cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of Cancer survivors. Cancer 113, 1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23713

McKinley, E. D. (2000). Under toad days: surviving the uncertainty of cancer recurrence. Ann. Intern. Med. 133, 479–480. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-6-200009190-00019

Miller, L. E. (2014). Uncertainty management and information seeking in cancer survivorship. Health Commun. 29, 233–243. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.739949

Mishel, M. H. (1990). Reconceptualization of the uncertainty in illness theory. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 22, 256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00225.x

Mistry, A., Wilson, S., Priestman, T., Damery, S., and Haque, M. (2010). How do the information needs of cancer patients differ at different stages of the cancer journey? A cross-sectional survey. JRSM Short Reports 1, 1–10. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2010.010032

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., and Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Nelissen, S., van den Bulck, J., and Beullens, K. (2017). A typology of Cancer information seeking, scanning and avoiding: results from an exploratory cluster analysis. Inf. Res. Int. Electr. J. 22:44680. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej1144680

Niederdeppe, J., Hornik, R. C., Kelly, B. J., Frosch, D. L., Romantan, A., Stevens, R. S., et al. (2007). Examining the dimensions of cancer-related information seeking and scanning behavior. Health Commun. 22, 153–167. doi: 10.1080/10410230701454189

O’Hair, H. D., O’Hair, D., Villagran, M. M., Wittenberg, E., Brown, K., Ferguson, M., et al. (2003). Cancer survivorship and agency model: implications for patient choice, decision making, and influence. Health Commun. 15, 193–202. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1502_7

O’Hair, H. D., Scannell, D., and Thompson, S. (2008). “Agency through narrative: patients managing Cancer Care in a Challenging Environment” in Narratives, health, and healing: Communication theory, research, and practice. (Routledge Communication series). eds. L. M. Harter, P. M. Japp, and C. S. Beck (Mahwah: Taylor and Francis), 413–432.

O’Malley, D. M., Hudson, S. V., Ohman-Strickland, P. A., Bator, A., Lee, H. S., Gundersen, D. A., et al. (2016). Follow-up care education and information: identifying Cancer survivors in need of more guidance. J. Cancer Educ. 31, 63–69. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0775-y

Ormandy, P. (2011). Defining information need in health - assimilating complex theories derived from information science. Health Expect. 14, 92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00598.x

Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., and Khalil, H. (2020). “Chapter 11: scoping reviews” in JBI manual for evidence synthesis. eds. E. Aromataris and Z. Munn (New York, NY: JBI).

Playdon, M., Ferrucci, L. M., McCorkle, R., Stein, K. D., Cannady, R., Sanft, T., et al. (2016). Health information needs and preferences in relation to survivorship care plans of long-term cancer survivors in the American Cancer Society’s study of Cancer survivors-I. J. Cancer Survivorship Res. Prac. 10, 674–685. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0513-4

Polite, B. N., Adams-Campbell, L. L., Brawley, O. W., Bickell, N., Carethers, J. M., Flowers, C. R., et al. (2017). Charting the future of Cancer health disparities research: a position statement from the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Cancer Society, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the National Cancer Institute. Cancer Res. 77, 4548–4555. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0623

Ramanadhan, S., and Viswanath, K. (2006). Health and the information nonseeker: a profile. Health Commun. 20, 131–139. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc2002_4

Riaz, I. B., Khan, M. A., and Osterman, T. J. (2025). Artificial intelligence across the cancer care continuum. Cancer 131:e70050. doi: 10.1002/cncr.70050

Robison, L. L., and Hudson, M. M. (2014). Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634

Rodler, S., Cei, F., Ganjavi, C., Checcucci, E., de Backer, P., Rivero Belenchon, I., et al. (2025). GPT-4 generates accurate and readable patient education materials aligned with current oncological guidelines: a randomized assessment. PLoS One 20:e0324175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0324175

Scarton, L. A., del Fiol, G., Oakley-Girvan, I., Gibson, B., Logan, R., and Workman, T. E. (2018). Understanding cancer survivors’ information needs and information-seeking behaviors for complementary and alternative medicine from short- to long-term survival: a mixed-methods study. JMLA 106, 87–97. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.200

Schmiedmayer, P., Rao, A., Zagar, P., Aalami, L., Ravi, V., Zahedivash, A., et al. (2025). Llmonfhir: A Physician-Validated, Large Language Model-Based Mobile Application for Querying Patient Electronic Health Data. JACC: Advances, 4:101780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2025.101780

Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N., and Jemal, A. (2024). Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 12–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21820

Soothill, K., Morris, S., Harman, J., Francis, B., Thomas, C., and McIllmurray, M. (2001). The significant unmet needs of cancer patients: probing psychosocial concerns. Supportive Care Cancer Off. J. Multinational Asso. Supportive Care Cancer 9, 597–605. doi: 10.1007/s005200100278

Squiers, L., Finney Rutten, L. J., Treiman, K., Bright, M. A., and Hesse, B. (2005). Cancer patients’ information needs across the cancer care continuum: evidence from the cancer information service. J. Health Commun. 10, 15–34. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263620

Stein, K. D., Syrjala, K. L., and Andrykowski, M. A. (2008). Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer 112, 2577–2592. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23448

Talyshinskii, A., Naik, N., Hameed, B. M. Z., Juliebø-Jones, P., and Somani, B. K. (2024). Potential of AI-driven Chatbots in urology: revolutionizing patient care through artificial intelligence. Curr. Urol. Rep. 25, 9–18. doi: 10.1007/s11934-023-01184-3