- Department of Tourism and Recreation, Cheng Shiu University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Amid intensifying competition from both traditional hotels and alternative lodging platforms such as Airbnb, building emotional customer–brand connections has become vital in the hospitality industry. This study investigates how hotel brand identity and brand image influence brand love and, subsequently, brand loyalty, with customer value cocreation behaviors as mediating factors. Drawing on social identity theory and social behavior theory, the model incorporates both engagement and citizenship behaviors to explore their respective impacts. Using purposive sampling, a structured questionnaire was administered in Taiwan and yielded 586 valid responses. Structural equation modeling (SEM) confirmed that brand image had a stronger effect on brand love than brand identity. Among the tested behaviors, information searching and advocacy demonstrated significant mediating effects between brand love and loyalty, underscoring their pivotal role in loyalty development. Other behaviors showed limited or nonsignificant influence. The findings emphasize the importance of emotionally driven and proactive cocreation behaviors in hospitality branding, particularly within the context of Taiwan’s digital service transformation. The study offers theoretical contributions to emotional branding and cocreation literature, and provides practical guidance for hospitality managers seeking to foster loyalty through targeted behavioral engagement.

1 Introduction

Amid the rapid evolution of the global travel and accommodation market, the hotel industry faces growing competitive pressure from both traditional rivals and alternative lodging platforms such as Airbnb, which offer flexible and diversified accommodations. In 2024, Airbnb reported over 4.9 billion nights and experiences booked globally and achieved annual revenue of USD 11.1 billion—a year-over-year increase of nearly 12% (Airbnb, 2024). According to the World Tourism Organization (2023), global hotel occupancy rates have gradually recovered post-pandemic, indicating a strong rebound in customer demand. In Taiwan, the Tourism Bureau reported over 65% hotel occupancy in 2023, underscoring the sector’s continued relevance. Additionally, Taiwan was ranked as the secondfastest-growing destination in Airbnb search volume worldwide in 2024, further intensifying competition. In this context, relying solely on service quality is no longer sufficient to secure customer loyalty and repeat business.

To remain competitive, hotels must strategically cultivate emotional connections between customers and their brands. Brand identity, which refers to the psychological connection and self-association customers develop with a brand, has been shown to influence brand loyalty through behaviors such as repurchase intention and word-of-mouth advocacy (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003). Brand equity, as conceptualized by Aaker (1991) and Keller (1993), represents the overall value of a brand in the customer’s mind and significantly affects customer preference and retention. Numerous studies suggest that brand image and brand identity jointly contribute to the formation of brand love—a deep emotional attachment to a brand—which in turn drives customer engagement behaviors and longterm loyalty (Albert and Merunka, 2013; Batra et al., 2012).

However, existing research on how these brand constructs interrelate—particularly within the hospitality sector—remains fragmented. While value cocreation and customer engagement have received increasing academic attention, few studies have explored how customer engagement behaviors mediate the relationship between brand love and brand loyalty in the hotel context. This gap is especially critical given the growing relevance of peer influence and brand advocacy in digital hospitality environments.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate how brand identity, brand image, and brand equity influence brand love and, subsequently, brand loyalty, with a particular focus on the mediating role of customer engagement behaviors. This research contributes to both theory and practice by offering actionable strategies for hospitality brand managers seeking to strengthen customer-brand relationships.

Although brand equity is briefly mentioned as a theoretical anchor, this study intentionally focuses on brand love as the emotional dimension of brand-consumer relationships, without modeling brand equity explicitly.

While prior studies have explored emotional branding and co-creation in general service contexts, few have focused on how these constructs interact in digital-first hospitality environments shaped by post-pandemic consumer behaviors. This study contributes by contextualizing the brand love–loyalty relationship within Taiwanese hotels implementing digital service transformation. In doing so, it highlights how experiential value, co-creation behaviors, and emotional attachment operate differently in hybrid service environments characterized by both physical and digital interactions.

Furthermore, this study contributes by integrating customer value co-creation into the emotional branding framework, offering a novel perspective on how behavioral mechanisms mediate brand loyalty in hospitality services—a relationship that remains underexplored in hotel research contexts.

To achieve these objectives, the study adopts a quantitative research approach. Data were collected via structured questionnaires administered to hotel customers in Taiwan. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the proposed relationships and identify key drivers of brand loyalty in the hospitality sector.

The research objectives are as follows:

Validate the effects of brand identity and brand image on brand equity.

Examine how brand love and customer engagement behaviors influence the formation of brand loyalty.

Provide strategic recommendations for hotel operators to enhance brand competitiveness.

2 Literature review

2.1 Social identity theory

Tajfel et al. (1979) proposed social identity theory, which describes the relationship between individuals and the social groups to which they feel they belong. Individuals tend to identify themselves through their connections with social groups or organizations. When individuals are in an environment with a reference object, they tend to classify themselves and others into various social categories. These categories help define their self-identity and construct their self-concept,

encompassing not only the groups they belong to but also the groups they aspire to join (Fujita et al., 2006). When individuals identify with a reference object that reflects their self-definition, they incorporate the values of that object into their own attitudes and behaviors to maintain a close relationship(Men and Tsai, 2013).

2.1.1 Social behavior theory and social influence in networked contexts

Social behavior theory provides a structural understanding of how individuals’ behaviors are shaped through interaction within social systems. Dubin (1970) social system framework posits that individuals occupy positions within a network, and their actions are influenced by their relational context. In brand communities, this theory explains how consumers adopt, reinforce, or resist behavioral norms, such as brand advocacy or engagement, based on their social interactions.

In the context of hospitality and influencer-driven marketing, this framework is particularly relevant.

As Lundblad (2003) observed in his critique of Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory, the effectiveness of message dissemination and behavioral adoption depends on social structure and perceived legitimacy. Yadav et al. (2022) further emphasized that engagement and behavior within organizations and communities are increasingly driven by value alignment, emotional involvement, and peer validation. In networked settings such as social media platforms, influencers, early adopters, and active brand participants function as behavioral catalysts, shaping customer value cocreation behaviors and loyalty outcomes through visible social influence.

Therefore, integrating social behavior theory helps clarify how customer engagement and citizenship behaviors are both individual expressions and socially influenced actions—especially in the digitally mediated hospitality sector.

2.2 Brand image

Brand image refers to the customer’s subjective perception of a brand, shaped by brand associations stored in memory (Keller, 1993). It plays a critical role in differentiating a brand from its competitors and in meeting customers’ needs and expectations, which in turn influences behavioral outcomes such as purchase intention—defined as the likelihood of a customer purchasing a particular product or service (Dodds et al., 1991; Ryu et al., 2008).

In the hospitality context, brand image is a key component of traveler-based brand equity and is described as “the perception of the overall brand reflected through brand associations in travelers’ memories” (Khan et al., 2019). A strong brand image is influenced by various factors, including brand awareness, brand associations, perceived brand advantages, emotional appeal, brand resonance, and corporate social responsibility (Saleem and Raja, 2014).

2.3 Brand identity

Martínez and Del Bosque (2013) defined brand identity as the deep psychological connection that customers form with a brand. This construct originates from social identity theory (Tajfel et al., 1979), which posits that individuals define their self-concept based on their perceived membership in social groups. In this context, brand identification refers to customers’ recognition of a brand as part of their social identity, encompassing cognitive, emotional, and evaluative components (So et al., 2016). When a brand represents a socially meaningful category to the customer, it fosters a sense of belonging and alignment. As a result, customers are more likely to engage in behaviors that reflect their identification with the brand, such as advocacy or repeated patronage (Bhattacharya and Sen, 2003).

Despite some conceptual overlap, brand identity and brand image represent distinct constructs. Brand identity stems from internal customer-brand identification and self-concept (Aaker, 1991; So et al., 2016), whereas brand image reflects the customer’s external perception formed through marketing signals and service experiences (Keller, 1993). This study treats them as independent constructs to reflect their different roles in customer psychology and loyalty development.

2.4 Brand love

Brand love—an emerging concept in the field of experiential consumption—is a strong, deep, and positive emotional connection that customers have with a brand, transcending the pure level of value and function to form a profound emotional investment. Customers are prompted to develop strong loyalty to the brand, are willing to frequently purchase the brand’s products or services, and even actively support and promote the brand on social media (Shimp and Madden, 1988). Shimp and Madden (1988) explored the construct of brand love, advocating structural similarities between interpersonal love and love for customer goods. Customers have strong emotional connections with only a small proportion of the brands they interact with.

2.5 Customer value cocreation behavior

Customer value cocreation behavior has emerged as a critical concept in service marketing and hospitality management, emphasizing the active role of customers in shaping service experiences and generating value. Grönroos (2012) defined value cocreation as the process through which customers participate in the service delivery process to enhance value outcomes. Yi and Gong (2013) further categorized these behaviors into two main types: customer participation behaviors (in-role) and customer citizenship behaviors (extra-role).

More recently, scholars have highlighted the social and networked nature of cocreation behaviors. According to Dubin (1970) social system theory, individuals interact within structured social networks where behavior is influenced by roles, relationships, and feedback mechanisms. In the context of hospitality services, customer value cocreation is not only a personal choice but also a response to social expectations and peer engagement within brand communities (Yadav et al., 2022). This view aligns with recent findings that value cocreation is facilitated by social identification, emotional bonding, and influencer-driven dynamics, especially in digitally mediated service settings (Islam et al., 2018).

In addition, technological factors increasingly shape the way customers engage in cocreation. Mehra et al. (2021) found that attributes such as perceived enjoyment, compatibility, and complexity significantly affect mobile app adoption among young consumers, which in turn influences their likelihood to engage with digital service platforms. Similarly, Tiwari et al. (2024) identified perceived enjoyment and social influence as necessary conditions for travel app usage, suggesting that digital interface design can facilitate or hinder customer participation.

Moreover, Saxena et al. (2025) applied the MOA (Motivation–Opportunity–Ability) framework to AI-enabled travel, showing that the presence of enabling technologies and customer capabilities can significantly boost cocreation behaviors in AI-integrated service environments. These insights point to the critical role of technological context in activating and sustaining customer participation and citizenship behaviors.

Furthermore, Srivastava et al. (2024) highlighted that interactivity in virtual communities significantly enhances user engagement, emotional bonding, and skill development. Their findings suggest that service systems with higher levels of interactivity may better foster cocreation behaviors such as feedback, collaboration, and advocacy, particularly in educational or service-oriented digital communities.

Segment-based research has also revealed that customer traits and travel motivations influence the form and intensity of cocreation behavior. Chowdhary et al. (2020), through a segmentation study on domestic rural tourists in India, identified four distinct tourist types:

knowledge seekers, novelty seekers, cultural immersion seekers, and family and leisure seekers. Each segment exhibited different motivations and behavioral tendencies, which have direct implications for their participation in value cocreation. For instance, knowledge seekers may be more inclined to provide feedback and seek information, whereas cultural immersion seekers may be more active in interpersonal engagement and advocacy. These findings suggest that customer cocreation behaviors are not uniform but vary across customer profiles, emphasizing the importance of understanding customer segments when designing engagement strategies in hospitality contexts.

2.5.1 Definition of customer engagement behavior

Customer engagement behaviors refer to customers’ participation in the service delivery process, acting as in-role behaviors necessary for value cocreation (Shamim and Ghazali, 2014). These behaviors include information sharing, information searching, responsible actions, and interpersonal interactions (Revilla-Camacho et al., 2015). For example, customers may inquire about service details from hotel operators, seek advice from other customers, provide relevant information to staff during service interactions to ensure their needs are met, and demonstrate cooperative attitudes by adhering to hotel rules and guidelines. Interactions between customers and employees also contribute to maintaining positive relationships (Junaid et al., 2020; Kim and Kim, 2021).

Dabholkar (2014) defined customer engagement behaviors as the extent to which customers participate in producing and providing services. Chan et al. (2010) described these behaviors as a structured measure of customer involvement in service cocreation and delivery processes, including sharing information, offering suggestions, and participating in decision-making. Dong and Sivakumar (2017) further conceptualized customer engagement behaviors as the degree to which customers contribute effort, knowledge, information, and other resources to the service process.

These behaviors are typically perceived as essential in-role actions by both employees and customers (Chen and Raab, 2017).

However, not all customer engagement behaviors exert the same influence on brand loyalty. For instance, while information searching demonstrated a significant mediating effect in this study, behaviors such as information sharing did not show a statistically significant impact. One possible explanation is that information sharing, although valuable, may be more passive or routine in nature and may not create strong emotional or relational bonds with the brand. Additionally, cultural norms in Taiwan may influence the way customers engage; for example, they may be less inclined to actively share brand-related information unless explicitly incentivized. Therefore, the relationship between certain engagement behaviors and loyalty may be context-dependent, requiring the presence of moderating variables such as customer trust, brand community involvement, or perceived reciprocity.

2.5.2 Definition of customer citizenship behaviors

Customer citizenship behaviors are voluntary and extra-role behaviors demonstrated by customers that benefit value creation, such as providing service improvement suggestions to the business, spreading positive word-of-mouth, and assisting other customers (Yi and Gong, 2013). These behaviors include feedback, help, advocacy, and tolerance (Revilla-Camacho et al., 2015). For example, customers may inform staff about issues in a restaurant or provide feedback on its services, actively recommend the restaurant to family and friends after a positive service experience, offer help or suggestions to other customers encountering service-related issues, and demonstrate patience by willingly waiting during service delays (Assiouras et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019).

2.6 Loyalty

Dick and Basu (1994) defined customer loyalty as the strength of the relationship between an individual’s attitude and their repurchase behavior. Jones and Sasser (1995) described customer loyalty as a customer’s willingness to repurchase a specific product or service in the future. They further distinguished between long-term and short-term loyalty; long-term loyalty reflects a customer’s tendency to continue purchasing products or services over a long period, and short-term loyalty indicates that customers may switch to new providers or products if better options become available. Seybold and Marshak (1999) articulated four reasons that customer loyalty is important for company profitability: (1) the longer a customer relationship lasts, the more revenue a company can generate from that customer, thereby increasing its baseline revenue; (2) as customers purchase more, company income grows accordingly; (3) loyal customers often recommend new customers to a company; and (4) loyal customers are willing to pay higher prices for satisfactory products and services, reducing the need for discounts or other incentives.

Given the exploratory nature of this study and the multifaceted structure of customer value cocreation, multiple sub-hypotheses (e.g., H3a–H3d) were formulated to delineate the unique roles of specific behavioral dimensions. This decomposition allows for more nuanced theoretical insights into how different types of engagement and citizenship behaviors influence brand loyalty.

3 Methodology

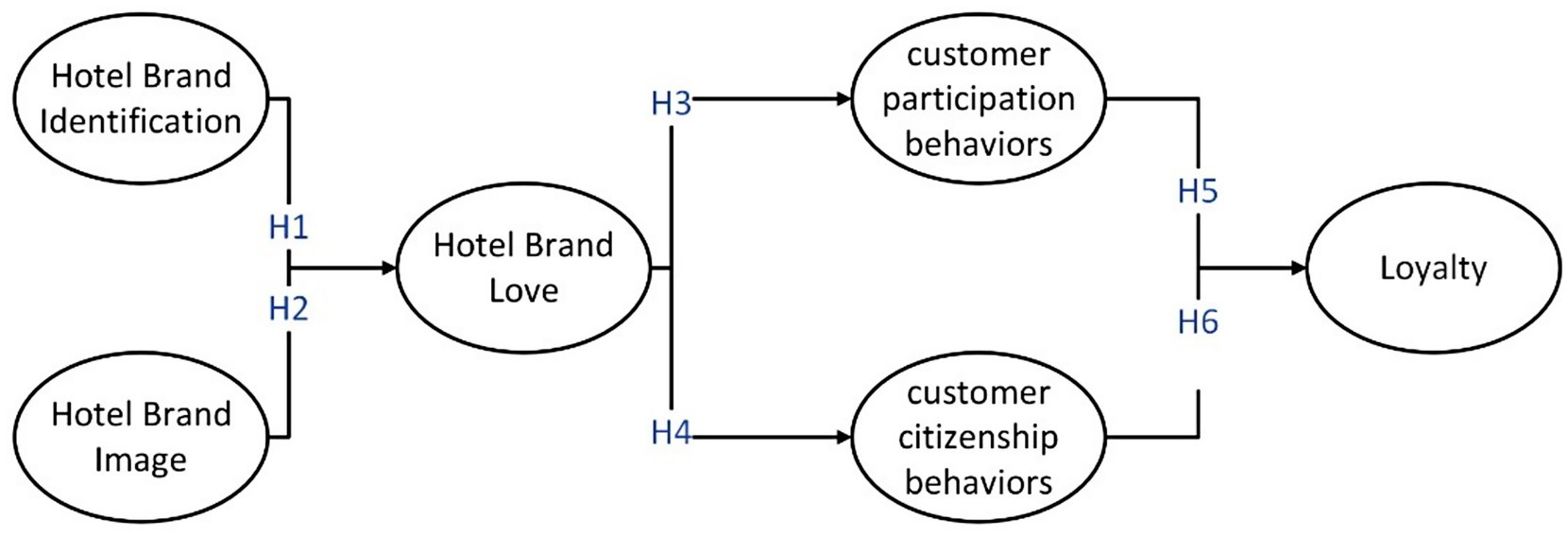

This study investigated whether hotel brand identity and brand image influence customer loyalty through the mediating roles of customer engagement behaviors and citizenship behaviors. The study explored the relationships between hotel brand identity, brand image, brand love, customer engagement behaviors, citizenship behaviors, and customer loyalty. The research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

3.1 Research hypotheses

3.1.1 Relationship between hotel brand identity, brand image, and brand love

In the process of influencing customers’ brand love, hotel brand identity serves as a critical psychological connection that significantly enhances customers’ emotional engagement and affection toward the brand. According to Lin and Choe (2022), brand identity refers to customers perceiving the brand as a part of their self-identity. This sense of identification fosters a deep emotional bond between customers and the brand.

H1: Hotel brand identity positively influences customers’ brand love.

Hotel brand image refers to customers’ overall perception and impression of the brand, encompassing the quality of services offered, facilities, and the overall experience. An enhanced hotel brand image has a positive effect on the formation of customers’ brand love. According to Lin and Choe (2022), the experiential value of luxury hotel customers significantly influences brand satisfaction, which in turn positively affects brand commitment and brand love.

H2: Hotel brand image positively influences customers’ brand love.

3.1.2 Relationship between brand love, customer cocreation behaviors, and loyalty

Brand love has been shown to enhance brand loyalty through customer value cocreation behaviors. When customers are emotionally attached to a brand, they are more likely to engage in participatory behaviors—such as providing feedback, sharing information, or advocating for the brand—that strengthen their relationship with it (Brodie et al., 2013; Veloutsou and Guzman, 2017). These value cocreation behaviors serve as mechanisms through which brand love is translated into sustained loyalty (Islam et al., 2018). Therefore, companies should actively cultivate brand love while promoting customer value cocreation behaviors to reinforce emotional connections and drive longterm brand loyalty.

3.1.3 Relationship between brand love and customer value cocreation behaviors

Multiple studies have reported a significant positive relationship between customer value cocreation behaviors and brand love. These behaviors include customer engagement behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors. Below is the reasoning process and literature support for this argument.

3.1.4 Effect of brand love on customer engagement behaviors

Customer engagement behaviors, such as information sharing, responsible actions, and interpersonal interactions, enable companies to deliver more personalized and high-quality services, thereby enhancing customer satisfaction and emotional connection with the brand. Lin and Choe (2022) noted that the positive experiences and emotional investment customers gain during their participation in the service process can strengthen their love for the brand. Such highly engaged and collaborative service experience allows customers to feel like an integral part of the brand, further enhancing brand love.

Grönroos (2012) supported said argument, stating that the perceived value customers gain through participating in the service process further deepens their emotional connection and attachment to the brand. This indicates that customer engagement behaviors not only improve satisfaction but also foster the development of brand love.

H3: Brand love positively influences customer engagement behaviors.

3.1.5 Effect of brand love on customer citizenship behaviors

It is important to distinguish customer citizenship behaviors from constructs such as subjective norms. While subjective norms involve external social pressure or conformity, customer citizenship behaviors are internally motivated and voluntarily performed. For example, the advocacy behaviors measured in Yi and Gong (2013) scale reflect customers’ desire to support and promote the brand out of emotional attachment—not due to social obligation. This study specifically focuses on selfinitiated actions that stem from emotional connection, rather than behaviors driven by external social expectations or normative pressure.

Customers who develop strong emotional connections with a brand are more likely to engage in such voluntary behaviors—offering suggestions, spreading positive word-of-mouth, helping others, or demonstrating patience during service failures—that benefit the brand and its community. These customer citizenship behaviors represent tangible expressions of brand love. As an affective driver, brand love motivates customers to go beyond transactional interactions and act as advocates for the brand. Zhang et al. (2024) emphasized that these behaviors reflect customers’ deep emotional commitment and identification with the brand. Therefore, the stronger the brand love, the more likely customers are to engage in citizenship behaviors that reinforce this emotional attachment.

H4: Brand love positively influences customer citizenship behaviors.

3.1.6 Relationship between customer value cocreation behaviors and brand loyalty

The relationship between customer value cocreation behaviors and brand loyalty has been validated in numerous studies, including customer engagement behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors. Below is the reasoning process and supporting literature.

3.1.7 Effect of customer engagement behaviors on brand loyalty

Customer value co-creation behavior refers to customer actions that contribute to the value-creation process during service interactions. Yi and Gong (2013) developed a widely adopted framework that categorizes these behaviors into two major domains: customer participation behavior and customer citizenship behavior.

Customer citizenship behaviors are defined as voluntary, extra-role actions that are not formally required but benefit the organization. These include feedback, help, advocacy, and tolerance. According to Yi and Gong (2013), such behaviors enhance firm performance by promoting a cooperative service environment. Revilla-Camacho et al. (2015) further argue that these discretionary behaviors strengthen emotional attachment to the brand, especially when they are recognized or reciprocated by the company. PhamThi and Ho (2024) similarly highlight that customer citizenship behaviors foster emotional commitment and trust, which in turn increase customers’ repurchase and retention intentions.

On the other hand, customer engagement behaviors—such as information sharing, responsible actions, and personal interaction—are typically considered in-role behaviors that directly influence service delivery and quality. These behaviors enable firms to customize and improve service experiences, thereby enhancing satisfaction and brand-related outcomes. Grönroos (2012) emphasized that the perceived value obtained from collaborative service experiences reinforces brand loyalty over time.

In summary, both customer citizenship behaviors (voluntary, extra-role) and customer engagement behaviors (in-role, participatory) play crucial roles in co-creating brand value. However, their psychological mechanisms and relative impacts on brand loyalty may differ, depending on whether the behavior stems from internal motivation, social identity, or situational cues. Therefore, a comprehensive examination of both behavior types is essential to understand their distinct contributions to loyalty formation in hospitality service contexts.

H5: Customer engagement behaviors positively influence customer loyalty.

3.1.8 Effect of customer citizenship behaviors on brand loyalty

Previous research has demonstrated that customer value cocreation behaviors contribute positively to brand loyalty. Yi and Gong (2013) found that customers who engage in value cocreation behaviors— such as providing feedback, helping others, and participating in brand-related interactions—tend to develop stronger emotional attachment and loyalty toward the brand. Similarly, Cossío Silva et al. (2016) confirmed that these behaviors enhance customers’ sense of belonging and long-term commitment. In particular, customer citizenship behaviors—voluntary, extra-role actions such as advocacy, tolerance, and assistance—play a crucial role not only in benefiting the brand but also in reinforcing the customer’s own identification with it (PhamThi and Ho, 2024). These behaviors often bring social recognition or deeper engagement, which further strengthen the customer–brand relationship over time.

H6a: Feedback positively influences customer loyalty.

Feedback allows customers to communicate dissatisfaction or offer suggestions for improvement. When brands respond effectively, it fosters trust and commitment, which can translate into loyalty (Revilla-Camacho et al., 2015).

H6b: Help positively influences customer loyalty.

Helping behavior, such as assisting other customers or employees, reflects strong affective attachment to the brand and a desire to sustain the brand community (Assiouras et al., 2019). These actions reinforce a sense of co-ownership and affiliation with the brand, which may enhance loyalty.

H6c: Advocacy positively influences customer loyalty.

Advocacy involves recommending the brand to others or promoting it through word-of-mouth. This public endorsement reflects deep emotional investment and has been shown to predict stronger brand commitment (Brodie et al., 2013).

H6d: Tolerance positively influences customer loyalty.

Tolerance refers to the customer’s willingness to accept minor service failures or delays. Such patience is often rooted in a long-term relationship orientation, and in high-trust environments, may reflect loyalty despite temporary dissatisfaction (PhamThi and Ho, 2024).

H6: Customer citizenship behaviors positively influence customer loyalty.

3.2 Sampling

This study focused on customers’ brand love for hotels and their value cocreation behaviors. A purposive sampling method was employed, and the survey was administered using both paper-based and online questionnaires. Paper surveys were distributed at the entrances and exits of train and metro stations in Kaohsiung, while online surveys were shared through Facebook groups related to hotel stays. Data collection took place from July to September 2024, covering both weekdays and weekends to enhance sample diversity and reduce temporal bias. According to Hair et al. (2010), the minimum sample size for structural equation modeling should be at least 10 times the number of measurement items. Given that the questionnaire contained 47 items, a minimum of 470 responses was required.

The selection criteria targeted individuals aged 20 and above who had stayed at a hotel within the past 12 months, ensuring that all respondents had relevant and recent brand experience. The survey was conducted from July to September 2024—a summer period in Taiwan—which may potentially influence customers’ psychological expectations due to peak travel season dynamics. Both weekdays and weekends were included to mitigate timing-related bias.

With a final sample of 586 valid responses and a total population of hotel customers in Taiwan estimated at over 1 million, the calculated margin of error is approximately ±4% at a 95% confidence level. These parameters enhance the generalizability and scientific rigor of the study while acknowledging contextual limitations such as regional and seasonal specificity.

“The use of both online and paper-based questionnaires was intended to maximize coverage across age groups and digital literacy levels. However, this mixed-mode design may introduce response style variation. To mitigate this, identical formats and scales were used, and no significant modebased response bias was detected during data screening”.

3.3 Questionnaire design

The questionnaire in this study comprises two sections: measurement of variables and respondents’ basic information. The first section consists of single-choice items for measuring variables. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale with endpoints ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The second section includes items related to brand image, brand identity, brand love, customer value cocreation, and loyalty.

Hotel brand identity is conceptually defined as the psychological state in which consumers are willing to actively choose and engage with the hotel brand. Questionnaire source: So et al. (2013).

Brand love is conceptually defined as the degree of consumers’ positive emotional responses and emotional attachment to a specific hotel brand. Questionnaire source: Wang et al. (2019).

Brand image is conceptually defined as the brand’s ability to provide value-for-money services, offering clear reasons for consumers to choose it over other brands, showcasing a unique and consistent personality, being perceived as interesting and attractive, and leaving consumers with a clear impression of its typical customers. Questionnaire source: Iglesias et al. (2011).

Customer engagement behaviors are conceptually defined as in-role behaviors that customers are required to perform during the service process, including information searching, information sharing, responsible action, and personal interactions. Questionnaire sources: Kim et al. (2019) and Roy et al. (2020).

Customer citizenship behaviors are conceptually defined as extra-role behaviors that customers voluntarily perform during the service process. These behaviors, although not essential for value cocreation, provide extraordinary value to the business. They include feedback, advocacy, help, and tolerance. Questionnaire sources: Kim et al. (2019) and Roy et al. (2020).

Consumer brand loyalty is conceptually defined as consumers’ loyalty and confidence toward a hotel, accompanied by their willingness to recommend it to others. Questionnaire source: Boo et al. (2024).

We collected 586 responses, with females comprising the majority (60.6%) and males making up 39.4%. Regarding age distribution, most respondents were aged 31–40 years (42.7%), followed by those aged 41–50 years (28.0%), 21–30 years (22.5%), and smaller proportions in other age groups. In terms of educational background, the majority held undergraduate degrees (75.1%), followed by master’s degrees (14.5%), high school or below (9.9%), and doctoral degrees (0.5%). Overall, the sample is primarily composed of young and middle-aged women who are highly educated.

4 Results

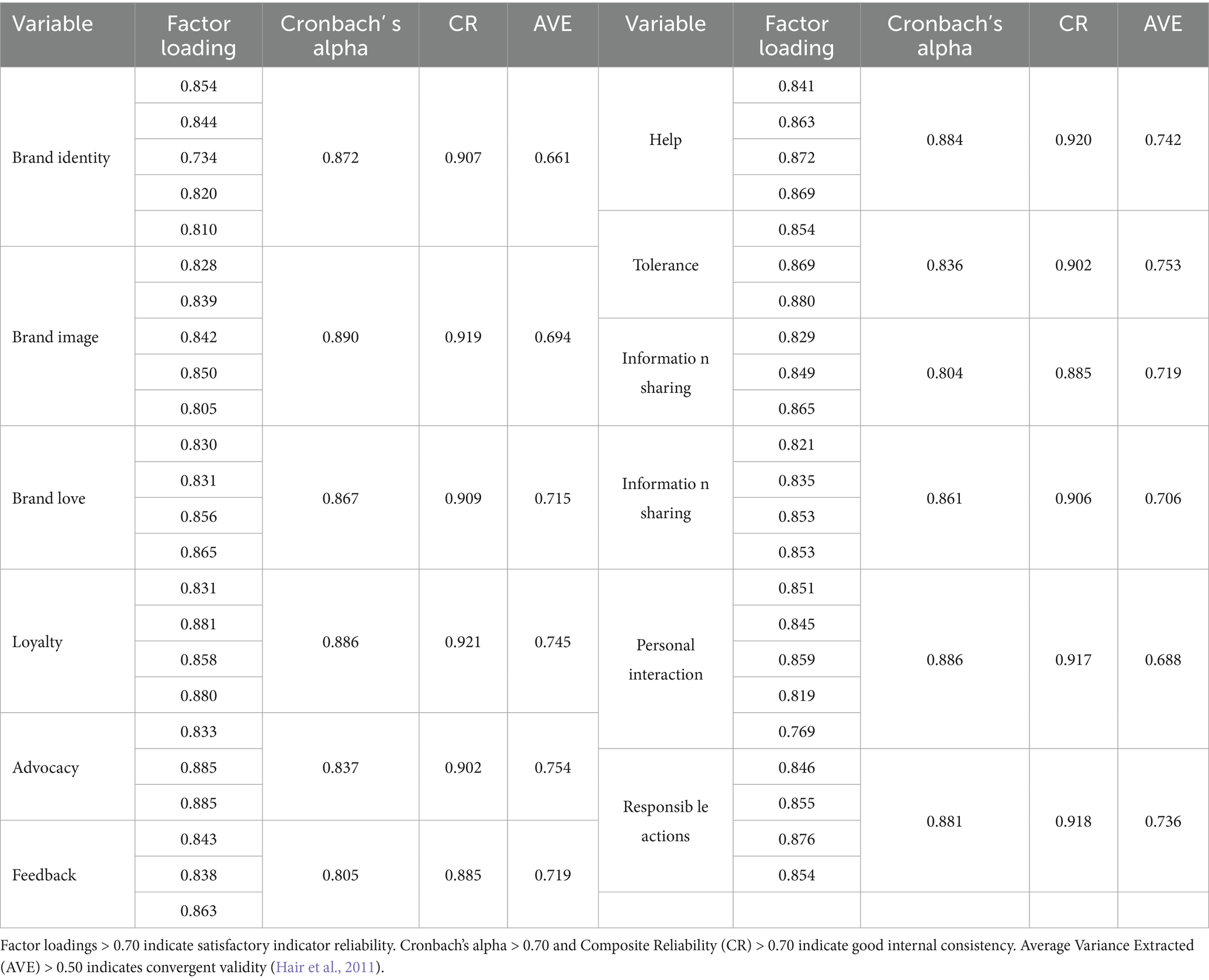

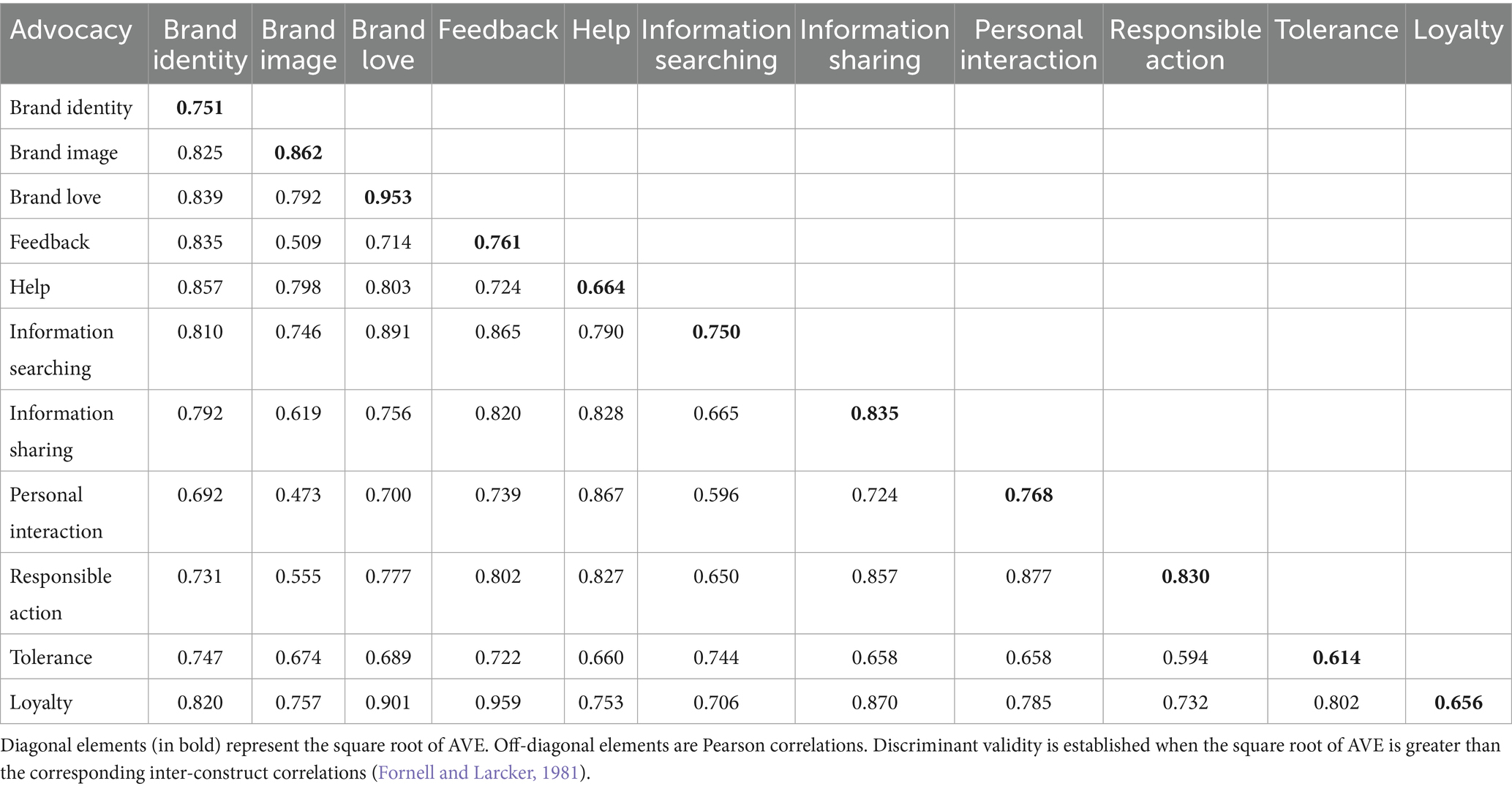

The measurement model evaluation covered three aspects: internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Internal consistency was assessed using composite reliability (CR), with all CR values surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating strong internal reliability. Convergent validity was confirmed through the average variance extracted (AVE), where all AVE values exceeded the suggested benchmark of 0.50, demonstrating adequate convergent validity. Discriminant validity was examined using cross-loadings, the Fornell–Larcker criterion, and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, with all HTMT values remaining below the critical threshold of 0.85, thereby confirming strong discriminant validity among constructs. The detailed measurement model evaluation results, including factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), are summarized in Table 1.

According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), composite reliability (CR) values above 0.70 indicate acceptable internal consistency, and average variance extracted (AVE) values should exceed 0.50 to demonstrate sufficient convergent validity. For discriminant validity, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) should remain below 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015). Variance inflation factor (VIF) values below 5.0 are also considered acceptable, indicating low multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2011). In the structural model, path coefficients are considered statistically significant when t-values exceed 1.96 at a 95% confidence level (two-tailed) (Table 2). Discriminant validity of variables using HTMT criterion.

4.1 Structural model

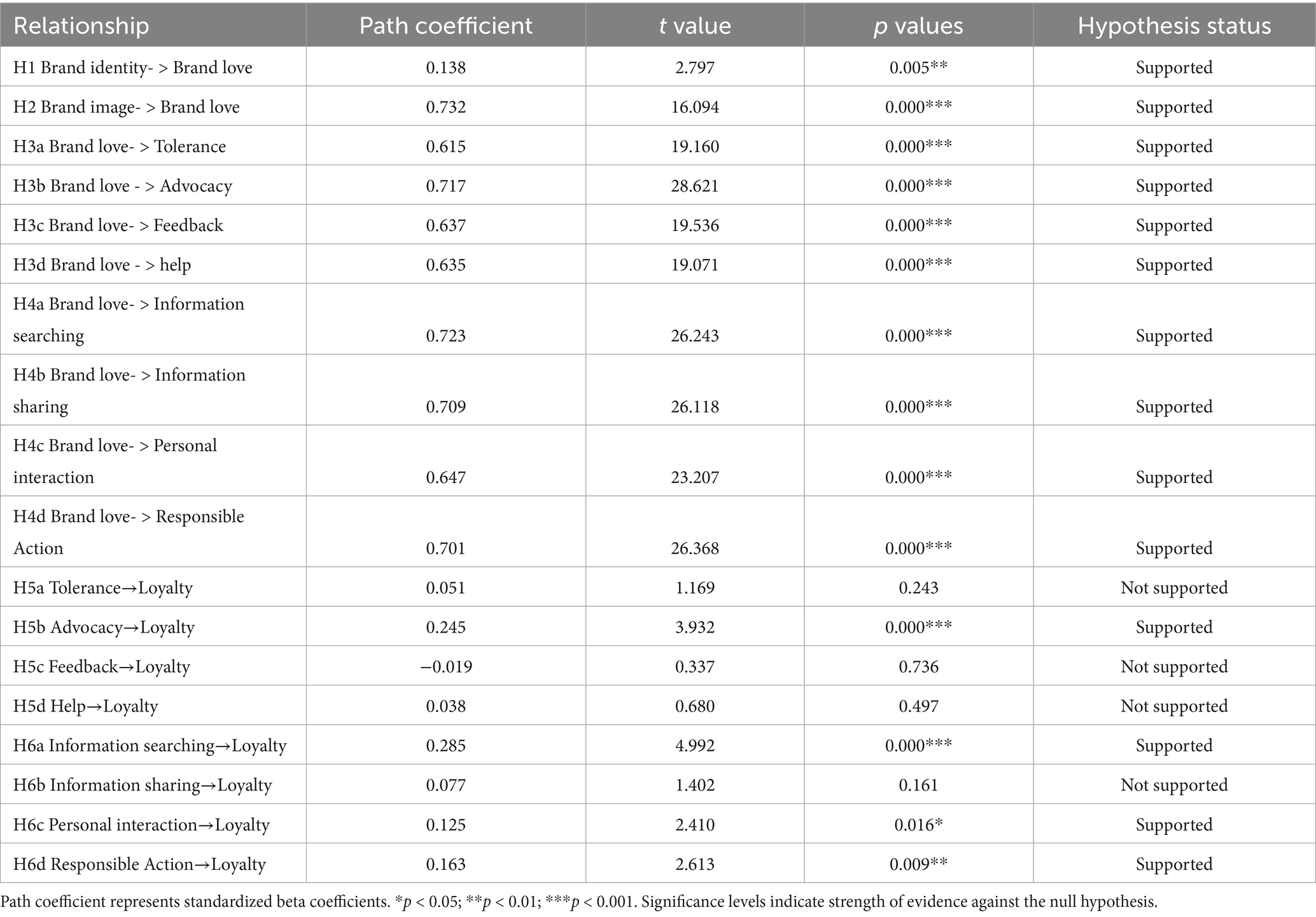

The influence of brand identity on brand love was significant (β = 0.138, t value = 2.797, p value = 0.005), supporting H1. The influence of brand image on brand love was significant (β = 0.732, t value = 16.094, p value = 0.000), confirming H2. The influence of brand love on tolerance was significant (β = 0.615, t value = 19.160, p value = 0.000), supporting H3a. The influence of brand love on advocacy (β = 0.717, t value = 28.621, p value = 0.000), feedback (β = 0.637, t value = 19.536, p value = 0.000), and help (β = 0.635, t value = 19.071, p value = 0.000) was significant, supporting H3b, H3c, and H3d, respectively.

The influence of brand love on information searching was significant (β = 0.723, t value = 26.243, p value = 0.000), supporting H4a. The influence of brand love on information sharing (β = 0.709, t value = 26.118, p value = 0.000), personal interaction (β = 0.647, t value = 23.207, p value = 0.000), and responsible actions (β = 0.701, t value = 26.368, p value = 0.000) was significant, supporting H4b, H4c, and H4d, respectively.

The influence of tolerance on loyalty was not significant (β = 0.051, t value = 1.169, p value = 0.243), so H5a was not supported. Advocacy significantly affected loyalty (β = 0.245, t value = 3.932, p value = 0.000), supporting H5b. Feedback (β = −0.019, t value = 0.337, p value = 0.736) and help (β = 0.038, t value = 0.680, p value = 0.497) did not significantly affect loyalty, meaning H5c and H5d are not supported.

Information searching significantly affected loyalty (β = 0.285, t value = 4.992, p value = 0.000), supporting H6a. The effect of information sharing on loyalty was not significant (β = 0.077, t value = 1.402, p value = 0.161), meaning H6b is not supported. Personal interaction (β = 0.125, t value = 2.410, p value = 0.016) and responsible action (β = 0.163, t value = 2.613, p value = 0.009) significantly affected loyalty, supporting H6c and H6d (Table 3).

5 Conclusion

5.1 Effect of brand identity and brand image on brand love

The results confirmed that both hotel brand identity and brand image exerted a significant and positive influence on brand love, with hotel brand image having a greater effect than brand identity (path coefficients of 0.732 and 0.138, respectively). This highlights the central role of a hotel’s overall impression and customer experience in shaping brand love, particularly factors such as service quality, facility standards, and emotional value, which play a crucial role in fostering customers’ emotional engagement with the brand. By contrast, brand identity serves as a supplementary factor, indirectly fostering brand love through customers’ sense of identification with the brand. Overall, these findings suggest that hotels should prioritize enhancing brand image to strengthen emotional connections with customers while complementing these efforts with strategies to reinforce brand identity, thereby achieving a more comprehensive construction of brand love. This study contributes by integrating customer value co-creation into the emotional branding framework, offering a novel perspective on how behavioral mechanisms mediate brand loyalty in hospitality services—a topic not yet sufficiently explored in hotel brand research.

5.2 Effect of brand love on customer value cocreation behaviors

The results confirmed that brand love significantly promoted customer engagement behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors, including information searching, information sharing, responsible actions, interpersonal interactions, and advocacy. Among these positive behaviors, information searching (path coefficient 0.723) and advocacy (path coefficient 0.717) exhibited the strongest responses to brand love, highlighting their critical roles in the process of converting emotional attachment into actual actions. This finding further demonstrates that when customers develop a deep emotional attachment to a brand, they not only actively engage in interactions related to the brand but also promote the brand’s value by sharing information, providing suggestions, or spreading positive word-of-mouth. These actions may even attract more consumers to join the brand’s ecosystem. Therefore, brand love is not just an emotional bond but also a key driver of multidimensional customer behaviors, playing an indispensable role in enhancing brand influence and market competitiveness.

5.3 Effect of customer value cocreation behaviors on brand loyalty

The effect of customer value cocreation behaviors on brand loyalty showed significant differences, suggesting that different types of behaviors play varying roles in fostering brand loyalty. “Culturally, the nonsignificant findings may also be influenced by the high-context nature of Taiwanese society, where customers tend to avoid direct confrontation or overt feedback (Hofstede, 2011).

5.3.1 Significant effects

Advocacy (path coefficient = 0.245, p < 0.001), information searching (0.285, p < 0.001), personal interaction (0.125, p < 0.05), and responsible action (0.163, p < 0.01) all exerted significant positive influences on brand loyalty. Among these, information searching and advocacy exhibited the strongest effects, underscoring the importance of customers who actively seek brandrelated information and promote brand value in reinforcing their emotional bond and behavioral commitment to the brand.

5.3.2 Nonsignificant effects

By contrast, tolerance, feedback, help, and information sharing did not show significant effects on brand loyalty. Several explanations may account for these findings. First, these behaviors may have weaker or more indirect associations with brand loyalty, requiring mediation through other psychological variables such as satisfaction or trust. Second, behaviors such as tolerance and feedback often represent passive or extra-role participation, which may lack sufficient emotional activation to directly translate into loyalty. Given the discretionary nature of customer citizenship behaviors, their influence may hinge on contextual factors such as social approval, perceived brand reciprocity, or internal motivation. Unlike in-role behaviors, they are not always visible to or reciprocated by the brand.

Furthermore, the insignificant effect of “help” and “information sharing” may be partially attributed to multicollinearity. These constructs—particularly help, personal interaction, and loyalty—showed high intercorrelations in the HTMT matrix. Although the variance inflation factors (VIFs) remained within acceptable thresholds, this collinearity may have obscured the unique contributions of these predictors. Future research is encouraged to examine this issue using variance decomposition or hierarchical modeling to isolate their individual effects more precisely.

Culturally, the nonsignificant findings may also be influenced by the high-context nature of.

Taiwanese society, where customers tend to avoid direct confrontation or overt feedback (Hofstede, 2011). As such, tolerance and feedback may be less frequent or impactful in shaping loyalty, compared to more proactive behaviors. These interpretations align with Cossío Silva et al. (2016), who found that passive or discretionary behaviors exerted limited predictive power on loyalty outcomes in the Spanish hospitality context.

5.3.3 Implications

These findings suggest that practitioners should prioritize encouraging value cocreation behaviors that directly promote loyalty, especially information searching and advocacy. Meanwhile, the nuanced roles of extra-role behaviors—such as tolerance and feedback—warrant further investigation to uncover their conditional impacts under specific motivational or cultural contexts.

Although several hypotheses were statistically supported (e.g., H1: Brand identity → Brand love; H6c: Personal interaction → Loyalty; H6d: Responsible action → Loyalty), their relatively modest path coefficients (0.138, 0.125, and 0.163, respectively) suggest that these factors play a secondary role in shaping loyalty. In contrast, brand image and information searching demonstrated stronger effects, reaffirming their critical role in driving customer engagement and loyalty formation.

Lastly, the moderate yet significant effects of H5b (Advocacy → Loyalty, β = 0.245) and H6a (Information searching → Loyalty, β = 0.285) may operate through complex pathways involving mediators such as trust, satisfaction, or emotional resonance. Further research is encouraged to explore these indirect mechanisms and boundary conditions.

5.4 Cross-cultural comparison with previous research

Furthermore, this study’s findings provide an interesting contrast to those of Cossío Silva et al. (2016), who validated the Yi and Gong (2013) scale in the Spanish context. Their research, conducted in the personal care service sector, found that information-related behaviors—such as information seeking, information sharing, and feedback—did not meet significance thresholds and were removed during the scale refinement process. As a result, their final validated model retained only five dimensions of customer value co-creation, notably omitting key engagement behaviors due to their weak explanatory power in the Spanish sample. By contrast, in the current study conducted in Taiwan’s hotel industry with strong technology-mediated interfaces (e.g., self-service kiosks and digital check-ins), information searching and advocacy emerged as the most impactful customer behaviors. These behaviors significantly mediated the relationship between brand love and brand loyalty. This divergence suggests that cultural and service-setting differences play a moderating role in how customers engage in value co-creation. Taiwanese consumers, especially in high-tech hospitality contexts, appear more inclined to actively seek information and advocate for brands they emotionally connect with. These findings underscore the importance of contextual and cultural adaptation of value co-creation constructs. Whereas the Spanish sample in Cossío Silva et al. (2016) emphasized interpersonal elements like personal interaction and responsible behavior, the Taiwanese sample in this study displayed a more proactive, information-driven approach. This highlights the need for further cross-cultural and cross-sectoral research to validate and extend the applicability of co-creation models in various service environments.

5.5 Implications

According to the findings of this study, brand image had a significantly stronger effect on brand love than brand identity, underscoring the central role of brand image as an emotional driver in service industries, such as the hotel sector. This result aligns with the literature, emphasizing the critical roles of service quality, facility standards, and emotional value in shaping brand love, further highlighting the importance of brand experience in fostering emotional connections. Brand identity, as a supplementary factor, provided a new perspective on how identity recognition indirectly promoted brand emotions. Brand love significantly drove both customer engagement and citizenship behaviors, extending the theoretical understanding of emotional branding and customer behavior. The study confirmed the close relationship between emotional investment and behavioral expression, particularly in the areas of information searching and advocacy, revealing the specific mechanisms by which emotional attachment translates into tangible actions. This provides brand management with precise tools for behavioral prediction.

The effects of customer value cocreation behaviors on brand loyalty were not uniform, underscoring the differential roles of engagement and citizenship behaviors in fostering loyalty. Proactive behaviors such as information searching and advocacy exhibited strong, positive, and significant impacts, confirming their function as key drivers in the formation of brand loyalty. These findings suggest that customers who actively seek brand-related information or advocate for the brand are more emotionally and behaviorally committed, offering a clearer basis for behavioral classification in loyalty-building strategies.

Conversely, nonsignificant results for behaviors like feedback and tolerance indicate that not all value cocreation behaviors equally influence loyalty outcomes. This highlights the complexity of behavioral mechanisms and suggests that certain extra-role behaviors may operate through indirect or contextual pathways, requiring further investigation into moderating variables such as cultural norms, perceived reciprocity, or service setting.

Furthermore, brand love demonstrated partial mediation through specific value cocreation behaviors—most notably, information searching and advocacy—emphasizing the central role of emotional attachment in driving loyal behavior. These significant mediation effects support the notion of behavior transformation in the value cocreation process, where emotional connections are translated into concrete loyalty outcomes. Meanwhile, the lack of significance in other behavioral paths may point to nonlinear or conditional relationships, suggesting a more nuanced interplay between behavioral diversity and loyalty that future research should explore.

While many hypothesized relationships were statistically supported, the nonsignificant findings related to feedback, tolerance, help, and information sharing reveal critical nuances in the cocreation–loyalty linkage. These behaviors, primarily categorized as customer citizenship behaviors (CCBs), may lack direct visibility or reciprocation from the brand, thereby weakening their impact on loyalty. Theoretically, this indicates that not all extra-role behaviors are equally consequential in driving loyalty—some may require intermediate psychological states, such as trust or perceived fairness, to become effective.

From a cultural standpoint, the Taiwanese context may also contribute to the muted influence of these behaviors. As a high-context society, Taiwan places emphasis on harmony and implicit communication (Hofstede, 2011), which could reduce the frequency or salience of feedback and confrontation-driven behaviors like tolerance. Thus, these actions may be less prominent in shaping brand loyalty in collectivist service environments, where indirect support (e.g., advocacy) is culturally preferred over explicit critique or unsolicited assistance.

Managerially, these insights suggest that encouraging all forms of co-creation indiscriminately may not yield optimal outcomes. Instead, brands should invest in identifying and nurturing those customer behaviors that align closely with both the service context and cultural expectations. This includes designing systems that reward high-impact actions such as information searching and advocacy, while creating safe, structured spaces for feedback and peer-to-peer assistance that are culturally sensitive and psychologically rewarding. Future research should further examine the boundary conditions—such as customer empowerment, digital platform interactivity, or brand community climate—that moderate the efficacy of different co-creation behaviors in loyalty formation.

5.6 Managerial implications

5.6.1 Optimizing brand image to strengthen brand love

Hotels should prioritize enhancing brand image to build emotional bonds with customers. This includes improving service quality, facility standards, and emotional value delivery. Storytelling marketing and visual identity can also be leveraged to build a unique brand culture. Social media should be used strategically to communicate brand values, while customer feedback should inform service optimization to reinforce brand love.

5.6.2 Promoting high-impact value cocreation behaviors

Encouraging proactive behaviors—such as information searching and advocacy—helps spread brand value and deepen customer engagement. Brands can stimulate these behaviors through interactive content, online brand communities, and partnerships with key opinion leaders (KOLs). These efforts drive positive wordof-mouth and strengthen emotional identification.

5.6.3 Providing incentives and platforms for brand participation

Incentive mechanisms such as loyalty rewards, early access to offers, or gamified point systems can motivate customers to participate in brand-related activities. In turn, these behaviors reinforce both emotional connection and behavioral loyalty. Establishing digital interaction platforms and organizing brand events (e.g., online seminars or fan gatherings) can also enhance participation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the [patients/participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin] was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

M-HW: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Airbnb,. (2024). Airbnb posts record revenue as company announces expansion plans. IG. Available at: https://www.ig.com/en/news-and-trade-ideas/airbnb-posts-record-revenue-as-company-announces-expansion-plans-250214

Albert, N., and Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 30, 258–266. doi: 10.1108/07363761311328928

Assiouras, I., Skourtis, G., Giannopoulos, A., Buhalis, D., and Koniordos, M. (2019). Value cocreation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 78:102742. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2019.102742

Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., and Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand love. J. Mark. 76, 1–16. doi: 10.1509/jm.09.0339

Bhattacharya, C. B., and Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 67, 76–88. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

Boo, S., Kim, M., and Kim, T. J. (2024). Effectiveness of corporate social marketing on prosocial behavior and hotel loyalty in a time of pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 117:103635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2023.103635

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., and Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: an exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 66, 105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.029

Chan, K. W., Yim, C. K., and Lam, S. S. (2010). Is customer participation in value creation a doubleedged sword? Evidence from professional financial services across cultures. J. Mark. 74, 48–64. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.74.3.048

Chen, S. C., and Raab, C. (2017). Construction and validation of the customer participation scale. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 41, 131–153. doi: 10.1177/1096348014525631

Chowdhary, N., Kaurav, R. P. S., and Sharma, S. (2020). Segmenting the domestic rural tourists in India. Tour. Rev. Int. 24, 23–36. doi: 10.3727/154427220X15791346544761

Cossío Silva, F. J., Vega-Vázquez, M., and Revilla Camacho, M. (2016). The customer’s perception of value co-creation. The appropiateness of Yi and Gong's scale in the Spanish context. ESIC Market, no. 153.

Dabholkar, P. A. (2014). How to improve perceived service quality by increasing customer participation. Proceedings of the 1990 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference.

Dick, A. S., and Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: toward an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 22, 99–113. doi: 10.1177/0092070394222001

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., and Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 28, 307–319. doi: 10.2307/3172866

Dong, B., and Sivakumar, K. (2017). Customer participation in services: domain, scope, and boundaries. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 45, 944–965. doi: 10.1007/s11747-017-0524-y

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Fujita, K., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., and Levin-Sagi, M. (2006). Construal levels and self-control. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 351–367. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.3.351

Grönroos, C. (2012). Conceptualising value co-creation: a journey to the 1970s and back to the future. J. Mark. Manag. 28, 1520–1534. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2012.737357

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Read Psychol Cult 2:8. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J., and Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2011). The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. J. Brand Manag. 18, 570–582. doi: 10.1057/bm.2010.58

Islam, J. U., Rahman, Z., and Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: a solicitation of congruity theory. Internet Res. 28, 23–45. doi: 10.1108/IntR-09-2016-0279

Junaid, M., Hussain, K., Asghar, M. M., Javed, M., and Hou, F. (2020). An investigation of the diners’ brand love in the value co-creation process. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.008

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 57, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700101

Khan, M. M., Memon, Z., and Kumar, S. (2019). Celebrity endorsement and purchase intentions: the role of perceived quality and brand loyalty. Market Forces 14, 99–120.

Kim, D. Y., and Kim, H.-Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: a nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. J. Bus. Res. 134, 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

Kim, E., Tang, L., and Bosselman, R. (2019). Customer perceptions of innovativeness: an accelerator for value co-creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 43, 807–838. doi: 10.1177/1096348019836273

Lin, Y., and Choe, Y. (2022). Impact of luxury hotel customer experience on brand love and customer citizenship behavior. Sustainability 14:13899. doi: 10.3390/su142113899

Lundblad, J. P. (2003). A review and critique of Rogers' diffusion of innovation theory as it applies to organizations. Organ. Dev. J. 21, 50–64.

Martínez, P., and Del Bosque, I. R. (2013). CSR and customer loyalty: the roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 35, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.009

Mehra, A., Paul, J., and Kaurav, R. P. S. (2021). Determinants of mobile apps adoption among young adults: theoretical extension and analysis. J. Mark. Commun. 27, 481–509. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2020.1725780

Men, L. R., and Tsai, W.-H. S. (2013). Beyond liking or following: understanding public engagement on social networking sites in China. Public Relat. Rev. 39, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.013

PhamThi, H., and Ho, T. N. (2024). Understanding customer experience over time and customer citizenship behavior in retail environment: the mediating role of customer brand relationship strength. Cogent Bus Manag 11:2292487. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2023.2292487

Revilla-Camacho, M. Á., Vega-Vázquez, M., and Cossío-Silva, F. J. (2015). Customer participation and citizenship behavior effects on turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 68, 1607–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.02.004

Roy, S. K., Balaji, M., Soutar, G., and Jiang, Y. (2020). The antecedents and consequences of value co-creation behaviors in a hotel setting: a two-country study. Cornell Hosp. Q. 61, 353–368. doi: 10.1177/1938965519890572

Ryu, K., Han, H., and Kim, T.-H. (2008). The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 27, 459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.11.001

Saleem, H., and Raja, N. S. (2014). The impact of service quality on customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and brand image: evidence from hotel industry of Pakistan. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 19, 706–711.

Saxena, S., Kaurav, R. P. S., Ramasundaram, A., Kataria, S., and Halvadia, N. B. (2025). AI enabled travel: a MOA-nificent journey. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 30, 1103–1121. doi: 10.1080/10941665.2025.2486022

Seybold, P. B., and Marshak, R. T. (1999). Customers. Com: How to create a profitable business strategy for the internet and beyond. Random House Audio Assets.

Shamim, A., and Ghazali, Z. (2014). A conceptual model for developing customer value cocreation behaviour in retailing. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 6, 185–196.

Shimp, T. A., and Madden, T. J. (1988). Consumer-object relations: a conceptual framework based analogously on Sternberg’s triangular theory of love. Adv. Consum. Res. 15:11.

So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. A., and Wang, Y. (2013). The influence of customer brand identification on hotel brand evaluation and loyalty development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 34, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.02.002

So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. A., and Wang, Y. (2016). The role of customer engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. J. Travel Res. 55, 64–78. doi: 10.1177/0047287514541008

Srivastava, K., Siddiqui, M. H., Kaurav, R. P. S., Narula, S., and Baber, R. (2024). The high of higher education: interactivity, its influence and effectiveness on virtual communities. BIJ 31, 3807–3832. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-09-2022-0603

Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., and Worchel, S. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict” in Organizational identity: A reader. ed. H. Tajfel, vol. 56 (London: Psychology Press).

Tiwari, P., Kaurav, R. P. S., and Koay, K. Y. (2024). Understanding travel apps usage intention: findings from PLS and NCA. J. Mark. Anal. 12, 25–41. doi: 10.1057/s41270-023-00258-y

Veloutsou, C., and Guzman, F. (2017). The evolution of brand management thinking over the last 25 years as recorded in the journal of product and brand management. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 26, 2–12. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-01-2017-1398

Wang, Y.-C., Qu, H., and Yang, J. (2019). The formation of sub-brand love and corporate brand love in hotel brand portfolios. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 77, 375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.08.001

World Tourism Organization,. (2023). World tourism barometer, September 2023 - Excerpt. UNWTO. Available at: https://pre-webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-09/UNWTO_Barom23_03_September_EXCERPT.pdf

Yadav, A., Pandita, D., and Singh, S. (2022). Work-life integration, job contentment, employee engagement and its impact on organizational effectiveness: a systematic literature review. Ind. Commer. Train. 54, 509–527. doi: 10.1108/ICT-12-2021-0083

Yi, Y., and Gong, T. (2013). Customer value co-creation behavior: scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 66, 1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.026

Keywords: brand loyalty, brand identification, brand image, brand love, customer value co-creation

Citation: Wu M-H (2025) The impact of brand identification, brand image, and brand love on brand loyalty: the mediating role of customer value co-creation in hotel customer experience. Front. Commun. 10:1626744. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1626744

Edited by:

Rahul Pratap Singh Kaurav, Fore School of Management, IndiaReviewed by:

M. Dolores Méndez-Aparicio, Independent Researcher, Madrid, SpainChanda Gulati, Prestige Institute of Management & Research, Gwalior, India

Copyright © 2025 Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ming-Hsuan Wu, am9obnNvbnd1MDExN0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Ming-Hsuan Wu

Ming-Hsuan Wu