- 1International Center for Ethics in the Sciences and Humanities, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

- 2Law Faculty, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

- 3Berlin School of Economics and Law, Berlin Institute for Safety and Security Research, Berlin, Germany

- 4Centre Marc Bloch, Berlin, Germany

The mainstreaming of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in technologies of various application fields offers many opportunities, but also comes with a number of risks for data subjects, users, developers, intermediaries and other stakeholders. This includes, among other things, risks posed by technical unreliability, epistemic opacity, privacy intrusions and algorithmic discrimination. As a consequence, scholars of various academic disciplines have proposed contestability as a concept and design principle that supports stakeholders in challenging and possibly correcting the adverse effects caused by certain AI systems. Most of the academic work in this context has been carried out by scholars of Human–Computer-Interaction, Design Research and Public Law. Building on this important work, we discuss a number of exemplary practices and aspects that should, in our opinion, be considered within the scientific study of AI contestation. Moreover, we propose a shift in attention from system-specific features and mechanisms toward a stronger consideration of motivations for contestations, of critical practices in organizations and of a contextualization within legal regulatory regimes. This includes anticipating risks and effective means for contestation, co-creating among stakeholders, formalizing the translation from principles to practices for AI contestability, governing contestation in deployed systems, facilitating a culture for contestation, rejecting AI as well as enabling external oversight and critical monitoring. These conceptual considerations will hopefully facilitate further research and empirical investigations on AI contestability in social science fields such as organizational studies, communication studies, science & technology studies and law.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) can support people in making better decisions in numerous areas such as work, entrepreneurship, administration, mobility, financial management, logistics, health care, information retrieval, data analysis and, arguably, providing citizens with more security. The wide-spread adoption of algorithmic decision making powered by the latest generation of machine learning (ML) technologies can, however, also lead to negative consequences for affected individuals and communities. Risks associated with AI-supported decision making include algorithmic decision, unreliability, opacity of decisions and privacy violations (Jobin et al., 2019; Hagendorff, 2020). Against this backdrop, emerging regulation like the EU AI Act highlights the importance of transparency and explainability of AI deployed in high-risk scenarios to safeguard against unreliable, unfair or malicious technologies. Research has shown (Kleemann et al., 2023; Rohlfing et al., 2021), however, that the combination of legal obligations and technical transparency measures may not be sufficient to enable contestability of decisions. The problems are, inter alia, linked to the common technical conceptualizations of AI model explainability that ignore the social elements enabling understanding and enacting contestability of decisions.

One can find several strands of academic authorship that deal with contestability, and particularly contestability in AI. First of all, contestability is often investigated as a normative principle or set of rules that may guide the design, deployment, use and supervision of AI systems. This perspective is, of course, mostly held by legal scholars who study provisions on contestability within legislation and other normative guidelines. Moreover, one can find explicit or implicit references to contestability within these normative frameworks themselves. While contestability is sometimes characterized as an intrinsic value fundamental to democratic societies (a means in itself) (Aler Tubella et al., 2020), it is far more often seen as an instrumental principle that facilitates the accomplishment of other basic values like justice and autonomy (a means to an end) (Lyons et al., 2021: 7f). Specifically, contestability can be understood as a system quality and instrument that matters whenever something goes wrong. If accountability ensures that decisions of technical systems are made in accordance with procedural and substantive standards, contestability is the necessary mechanism to hold someone responsible if these standards are not met (Doshi-Velez et al., 2019; Henin and Le Métayer, 2022). In the long run, the ability to contest decisions is thought to be a conducive element to establish better accountability within an algorithmic system.

The roots of a right to contest lie in the ability to challenge decisions—whether judicial, administrative, or political—that negatively affect individuals or groups. Traditionally, individuals have had the right to contest outcomes in legal proceeding through appeals, complaints, or counterclaims. The rise of automated decision-making (ADM), where AI systems increasingly determine significant outcomes such as employment decisions, credit allocation, or access to services, introduces the need to extend this right to decisions made by algorithms. This extension is justified not merely as a procedural safeguard but as a tool to uphold substantive rights such as fairness, justice, and consistency (Kaminski and Urban, 2021, p. 1974f.). Contestation ensures that errors or injustices arising from opaque or biased AI systems can be rectified while enhancing the legitimacy of both the system and its outcomes. From the perspective of human rights, it has been argued that a right to contest in the context of ADM and AI should ensure that individuals are aware of being subject to algorithmic profiling and are equipped to challenge the rationale behind these decisions (Wachter and Mittelstadt, 2018). The burden of proof should, however, not fall on the individual contesting the decision but on the AI operator, who must demonstrate the decision’s fairness and compliance with relevant norms. Effective contestation frameworks, therefore, require sufficient transparency and justifications for decisions, enabling individuals to assert their rights meaningfully. Kaminski and Urban (2021) introduce four contestation archetypes for designing effective systems to contest AI decisions which vary along two axes: from contestation rules to standards and from emphasizing procedure to establishing substantive rights. The first axis distinguishes between a “contestation rule” and a “contestation standard.” A legal rule is defined as providing precise content ex ante, whereas a legal standard is determined by an interpreter ex post. On this basis, a contestation rule “is similar to a legal in that its precise details are spelled out ex ante, by legislators or regulators, including: a notice requirement, a timeline for complaining, a timeline for responses to complaints, or formal requirements for how to complain” (Kaminski and Urban, 2021, p. 2006). On the other hand, a contestation standard, “merely states that there is a right to contest, leaving the procedural details to future decision-makers, private or public” (ibid.). The second axis varies between “substantive contestation” and “procedural contestation.” Substantive contestation mechanisms include both the rules for challenging a decision and the specific grounds (substantive rights) on which the challenge is based. Procedural contestation focuses on the processes by which individuals can contest a decision, without necessarily linking the process to specific substantive rights (idem., p. 2007). It can further be argued that contestation mechanisms should include meaningful notice and explanations of decisions, opportunities for human review, and processes to correct unjust or erroneous outcomes (idem., p. 2035).

Researchers in computer science, human-computer-interaction (HCI), design research and law have translated these normative expectations and conceptualizations into frameworks elaborating contestability in AI as a comprehensive design principle (Alfrink et al., 2022; Almada, 2019; Henin and Le Métayer, 2022; Hirsch et al., 2017; Lyons et al., 2021; Vaccaro et al., 2021). According to Marco Almada, “a system that is contestable by design should be built in ways that allow users and third parties to effectively seek human intervention in a given automated decision” (Almada, 2019). The means for contestability would, first, require the accessibility of the necessary information to contest, and second, a provision of adequate channels to request an intervention. In this sense, contestability goes far beyond explanation and justification, as it additionally requires appropriate channels to intervene and request an acknowledgement of wrong-doing and possibly a correction. Existing scientific contributions on the topic of contestability in AI can be attributed to three different interpretations: those focusing on contestability as an ex post mechanism, those highlighting possibilities and needs for additional ex ante contestability, and those combining the two approaches in a holistic perspective.

Lyons et al.’s (2021) have provided a very informative conceptualization of the affordances for ex post contestability in AI. On the one hand, the authors highlight the importance of effective policy decisions that provide the scope for contestation. These should specify (a) what can be contested, (b) who can contest, (c) who is accountable, and (d) what type of review applies. On the other hand, the contribution includes a detailed model of a contestation procedure for AI-based decision making, including (a) the individual decision of the system, (b) a notification of the decision, (c) a notification of the ability to contest, (d) an explanation for the decision, (e) an interactional mechanism to activate contestation, which then (f) finally activates a review process of the decision. To qualify as contestable AI, the system in question would need to include these elements and ensure an effective interaction between them.

Scholars like Almada (2019), however, also highlight ex ante possibilities for contestation before a system acts in a problematic way. In this reading, “a preventive approach [to contestability] can be seen as an early intervention which allows data subjects to contest the hypotheses and design choices made at each stage of an AI’s design and deployment” (Almada, 2019). Accordingly, such preventive approaches can help to reduce technical obstacles and social barriers that possibly hinder stakeholders from successfully challenging AI decisions in deployed AI systems.

Finally, authors have also provided holistic perspectives that highlight moments for contestability within the entire AI lifecycle combining both ex ante and ex post approaches. Most systematically, Alfrink et al. (2022) have identified requirements for contestability in the stages of business & use-case development, design phase, training & test data procurement, building, testing, deployment and monitoring. They have also specified concrete technical features and mechanisms that enable contestability in AI systems including built-in safeguards against harmful behavior, interactive control over automated decisions, explanations of system behavior, human review and intervention requests, and tools for scrutiny by subjects or third parties. In addition to technical features, Alfrink et al. (idem.) also made a valuable effort to address the quality of contestation as a practice. Their contestability framework differentiates features and practices conducive for contestability with the latter including elements with more ‘social’ components like ex-ante safeguards, agonistic approaches to ML development, quality assurance during development, quality assurance after deployment, risk mitigation strategies and third-party oversight. In our opinion, the consideration of practice and the categories that are proposed in that article enable to grasp the complex socio-technical fabric of successful contestation, which is arguably more difficult to formalize and characterize than technical features and processes. We think, however, that characterization may profit from further investigations and the consideration of the rich literature in social theory that characterizes contestation as a social practice. Our view of contestation draws mainly on a practice-theoretical perspective, which views society as a complex system of interconnected practices, thereby providing an alternative to social theories that focus primarily on individual agency or macro-level structures. Against this background, we aim at contributing to existing conceptualizations by focusing specifically on the social and normative dimensions of AI contestation practices.

2 Theoretical background: social practices, normativity and contestation

Our view of contestation draws mainly on a practice-theoretical perspective, which views society as a complex system of interconnected practices, thereby providing an alternative to social theories that focus primarily on individual agency or macro-level structures.

2.1 Social practices

The influential work by social scientist Theodore Schatzki describes social practices as “embodied, materially mediated arrays of human activity” (Schatzki et al., 2001, p. 2), which are organized by shared practical understanding, rules, and teleoaffectivity (Schatzki et al., 2001, p. 16). Shared practical understanding, in this context, refers to the common knowledge among participants how to correctly perform an activity: “knowing how to X, knowing how to identify X-ings, and knowing how to prompt as well as respond to X-ings.” (Schatzki, 2002, p. 77). For a practice of contestation to exist, participants would have to be aware of the approaches, procedures and tools by which AI can and should be challenged. They must be competent to contest. In the context of AI and ADM, this may necessarily include (at least) some (basic) knowledge about the way these digital technologies operate. Social practices of contestation related to AI must, as a result, always be understood as material practices (humans interacting with technology). Second, established norms specify what counts as legitimate contestation and what does not. Rules are understood by Schatzki as “explicit formulations, principles, precepts, and instructions that enjoin, direct, or remonstrate people to perform specific actions.” (Schatzki, 2002, p. 79). For contestation in AI, this may refer to provisions in hard law, but also to institutional guidelines or community-related codes of conduct. For this study, we will especially focus on the European normative context and the role the new AI Act plays in facilitating certain practices of contestation and complicating others. Finally, teleoaffectivity describes a structure of normativized and hierarchically ordered ends, projects and tasks, as well as emotions and moods to be associated with a practice (Schatzki, 2002, p. 80). As we will show later in the study, contestation in AI may be driven by fairly different motivations and justifications. These differences in teleoaffective structures should, in our opinion, be considered more in detail as they will equally influence how contestability in AI unfolds in practice.

2.2 Contestation as a social practice

Practice theory has informed multiple studies in the social sciences (e.g., political science, sociology, and organizational studies) that specifically characterize social practices of contestation. As an example for such work, one can mention international relations scholar Antje Wiener who dedicated an entire anthology to theorizing contestation and describes it as a critical discursive practice that is constitutive for normative change (Wiener, 2014, p. 15). As a social activity, contestation entails a discursive and critical engagement with norms of governance and is constitutive for social change. As a normative critique, it reflects an intention to either preserve or alter existing conditions. This can manifest through actions such as civil society groups’ claim-making, rejecting the standards used in international talks, resisting the application of norms locally, engaging in situative opposition or exhausting the interpretation of applicable norms (idem., p. 2). Another line of inquiry into contestation is found in organizational studies, particularly research on whistleblowing, which refers to individuals who report illegal or unethical conduct within their organizations (Alford, 1999, p. 266). For example, Weiskopf and Tobias-Miersch (2016) characterize whistleblowing in organizations as a social practice of contestation challenging established routines and regimes of truth at the workplace. This practice can, according to the authors, be either organized vertically or horizontally. In its vertically organized manifestation, whistleblowing is institutionalized and channeled authoritatively, whereas in its horizontal manifestation, it takes the shape of a situative, informal, ethico-political practice (idem, p. 1622). Practices of contestation are also an established object of inquiry in media studies. Couldry and Curran (2003), for instance, investigate contestations of media power and how everyday practices are reconfigured to enable sustainable challenges of that power. They highlight the performative aspect of contestation as a practice to do things differently: contestation, in this reading, is not just about saying no to an established norm, but to suggest and cultivate new ones. From a different angle, but equally relevant to our own investigation, Green (2021) identifies contestation as a central practice in technology ethics. He describes the latter as a terrain of contestation circling around the questions of what ethics entails, who gets to define it, and what impacts it generates in practice.

2.3 The normativity of practice

Referring to the conceptualization of practice instead of technical features and mechanisms of contestability offers intellectual and operational opportunities but also triggers questions and poses challenges. Both opportunities and challenges are related to the normative aspects of practice in general, as well as particularly in the context of contestability in AI. On the one hand, practices are always normative. They are “normatively unified regularities,” as philosopher Haslanger (2018, p. 240) is highlighting. Contestation is an example of a practice in which this normativity is especially obvious. Our liberal-democratic mode of governing values some practices of contestation as legitimate (e.g., organizing a public demonstration to draw attention to a perceived injustice) and encourages them through legal rules, enforcement structures and facilitating resources. Other practices of contestation (e.g., committing acts of vandalism during a demonstration) are delegitimized and sanctioned. Adhering to Schatzki’s conceptualization, we have to highlight that rules and normativity as components of practices do not only and necessarily refer to provisions in written law, but they also include softer normative devices like standards and guidelines as well as implicit social conventions. For this article, we still put emphasis on emerging legal rules and mechanisms as we believe that they will have a strong impact on the way contestability in AI unfolds in and as a practice.

On the other hand, investigating practice in the context of AI requires particular attention to normativity, since AI-related practices are only emerging and can rather be imagined, anticipated, or proposed than empirically observed. Recognizing this, we chose to give a particular consideration to the legal rules that ought to structure AI-related practices of contestation in the future and focus on the European context to do so. This regulatory focus acknowledges the increasing importance that legislation will have on the interpretation and realization of contestability unfolding in practice. Accordingly, the present article concretizes obligations for AI contestability under EU legislation and includes critical thoughts on the (potential) effectiveness of these (emerging) provisions. Moreover, we believe that AI-related practices of contestation should not be considered as idiosyncratic phenomena, but as reconfigurations of existing practices of social contestation and critique. As we will show later on, practices of contestation in AI show strong overlapping to and inherit qualities from established practices in organizations like quality control and whistleblowing. It seems beneficial, then, to take a closer look at these practices and evaluate whether and to what extent they inform AI-related technical features, formalized norms, governance structures, social routines and organizational communication.

3 Research questions and methodology

We investigate contestation in AI as a normatively structured, socio-technical practice and ask to what extent existent models of AI contestability can be supplemented by this perspective. The investigation draws on theoretical insights from research areas such as science and technology studies (STS), AI ethics, organizational studies, and public law. On an empirical level, it is informed by the authors’ participation in ELSA-type research and development constellations (investigation of ethical, legal and social aspects) within several projects aiming at the development of AI systems in high-risk scenarios such as law enforcement, recruitment, and education. Most concretely, this includes observations made during a multi-year transdisciplinary research and innovation project aiming at developing and evaluating trustworthy AI-based methods for police intelligence in Germany. The authors accompanied the technical development of these methods from the perspective of ethics and legal studies in a setting of integrated research (Spindler et al., 2020), which refers to a constellation in public-funded research and innovation projects requiring interdisciplinary teams including computer scientists, engineers, legal and ethical scholars, social scientists and entrepreneurs. ‘Integrated’ in this context is employed as a demarcation from earlier configurations of accompanying ELSA-research, which have been criticized as insufficiently effective due to their distance from the reality of technical development. Concretely, this means that the authors participated in numerous meetings at working and management level and sometimes also conducted small bilateral projects with individual technical project partners addressing concrete ethical and legal challenges. The proximity toward technical developers also has consequences for the potential space for contestation practices, which we will be critically reflect further on below in this article.

4 Emerging regulatory regimes for contestability in AI

The right to contest AI has been incorporated into hard and soft law within various political and geographical settings. For example, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) stated in its Recommendation of the OECD Council on AI, that AI actors should “enable those adversely affected by an AI system to challenge its outcome based on plain and easy-to-understand information on the factors, and the logic that served as the basis for the prediction, recommendation or decision” (OECD, 2024, para 1.3 (iv.), emphasis added). In the context of binding legal rules, Article 22 of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) stipulates that individuals affected by certain automated decisions must be afforded “at least the right to obtain human intervention […] to express his or her point of view and to contest the decision” (Art. 22(3) GDPR, emphasis added). The EU AI Act then builds upon these GDPR protective measures by extending contestation rights to individuals affected by decisions made by high-risk AI systems with a right to explanation of individual decision-making. The AI Act emphasizes that individuals must receive a clear and meaningful explanation of the role of the AI system in the decision-making process and its key components (Art. 86 AI Act). In contrast to the GDPR, the AI Act not only refers to fully automated processes, but it also shifts the focus to the role of system results in influencing decisions. Accordingly, it is recognized that decisions made by partially automated systems involving humans in the loop must be just as contestable as those made by fully automated processes. The AI Act also highlights the importance of transparency and meaningful human oversight in ensuring that affected individuals are empowered to contest AI-based decisions effectively.

The legal regulation of this phenomenon is, of course, not a purely European development. In the USA, several presidential executive orders have developed standards in the field of AI regulation such as the “Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence” (The White House, 2023) and the “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights” (idem., 2022), which were however partially revised by other executive orders such as “Removing Barriers To American Leadership In Artificial Intelligence” (idem., 2025a) or “Preventing Woke AI In The Federal Government” (idem., 2025b). The Executive Order “Winning the race: America’s AI Action Plan” published by the White House in July 2025 can be interpretated as constituting a form of contestation of a certain conception of legal and ethical AI regulation, for instance in its willingness to “Ensure that Frontier AI Protects Free Speech and American Values” by eliminating in a revised version of the NIST AI Risk Management Framework any references to misinformation, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and climate change (The White House, 2025c, p. 4).

AI and its regulation also play an important role in other regions of the world, especially in countries with important digital industries like China (CSET, 2024), Japan (Paulger, 2025) and South Korea (CSET, 2025). The consideration of provisions for contestation in the different jurisdictions, however, are beyond the scope of this article.

5 AI contestation as a practice: a non-exhaustive typology

In the following, we discuss a number of exemplary practices, activities and constellations that influence the ways contestation in AI development, deployment, use and supervision is realized or impeded. We begin with practices to be carried out in development teams, before addressing those in deploying organizations, as well as overseeing and monitoring institutions.

5.1 Developing teams

The first type of practices concerns ex ante contestation playing out in the phase of development including anticipating risks and effective means for contestation, co-creating among stakeholders and formalizing the translation from principles to practices for AI contestability.

5.1.1 Anticipating risks and effective means for contestation

Actors involved in the development of emerging technologies often face what is known as the Collingridge dilemma (Collingridge, 1982), which highlights the challenges of effectively addressing the social, cultural, and political impacts of new technologies. In the early stages of development, technologies are still flexible and adaptable, making it relatively easy to influence their direction. However, at this point, it is difficult to fully anticipate their consequences or potential societal impacts, as the technology is neither widely used nor well understood. In contrast, once a technology becomes more established and integrated into society, its effects are easier to observe and assess. By then, however, it is typically so deeply embedded in social, economic, and political systems that modifying, regulating, or redirecting its course becomes significantly more difficult, costly, and complex. A number of established methodologies such as Value-Sensitive Design (VSD) (Friedman and Hendry, 2019) and Scenario-Based Design (SBD) (Rosson and Carroll, 2007) try to solve the Collingridge dilemma by providing strategies to anticipate probable socio-technical entanglements of emerging technology and ethical value considerations. They also offer methods to address these considerations and associated risks for stakeholders within technology design.

Authors have highlighted the importance to consider contestability within the early imaginations of AI technologies and ADM. Henin and Le Métayer (2022), for instance, call for ex ante algorithmic impact assessments involving external stakeholders and Sarra (2020) discusses ex ante and individual (but pragmatic) considerations of risks in ADM in the context of the GDPR and its provisions on safeguard measures. Almada (2019) is even more specific and calls for predictive contestability, a preventive approach to contestability, that empowers data subjects to contest the hypotheses and design choices made at each stage of an AI’s design and deployment.

The AI Act includes several requirements for anticipatory consideration of risks by different AI actors and at different stages of the AI lifecycle. First, providers of high-risk AI systems must establish and implement a risk management system (Art. 9 AI Act) that works as a continuous and iterative process throughout the lifecycle of the AI system, identifying and addressing known and reasonably foreseeable risks, including those arising from foreseeable misuse. Second, AI providers are required to anticipate and mitigate potential biases in training and operational data that could negatively impact health, safety, or fundamental rights, especially where data outputs influence future inputs (Art. 10(2)(f) AI Act). Third, they must inform users of any known or foreseeable risks arising from intended use or misuse of the AI system, thus requiring anticipation of such risks in documentation. Fourth, anticipation of risks must also intervene after an AI system has been placed on the market, as part of the obligation for AI providers to establish and use a post-monitoring system (Art. 72 AI Act), for which they are required to collect relevant data from AI deployers in order for AI providers to evaluate the continuous compliance of AI systems with the requirements applicable to high-risk AI systems under the AI Act. Finally, risk anticipation is required as a consequence of the obligation to conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment under certain circumstances prior to the deployment of a high-risk system by public institutions or private entities providing public services. A fundamental rights impact assessment must, inter alia, anticipate which social groups are likely to be affected by its use in the specific context of use and which specific risks of harm that are likely to have an impact on them (Art. 27(1)(c)-(d), Recital 96 AI Act). Additionally, this provision requires AI deployers to describe the planned human oversight measures in line with the instruction for use, as well as the measures to be taken if anticipated risks materialise, including internal governance arrangements and complaint mechanisms (Art. 27(1)(e)-(f) AI Act).

However, the general architecture of the AI Act leaves a certain amount of room for maneuver to the various AI subjects within the scope of the Act, which may potentially allow them to contest the concrete application of some obligations themselves, what may in turn allow other AI subjects, supervisory authorities or data subjects to contest decisions taken by these AI subjects. In the current state of the AI Act, there are indeed many obligations whose concrete scope of application needs to be specified. This has led parts of the literature to identify a logic of self-regulation in the AI Act which could preempt some possibilities of contesting issues of (non-)compliance with the AI, even though other voices have raised several risks or questions regarding the excessive regulatory burden that the Act will impose on relevant AI market actors.

Alfrink et al. (2022) have also considered technology and risk imagination as a practice enacting AI contestability. In terms of timing, they place this practice at an early phase within the AI lifecycle focusing on business and use case development. They then recommend incorporating the insights gained from this anticipation into the subsequent phases of the AI system’s life cycle, which may, for instance, translate to make contestability part of a system’s acceptance criteria.

5.1.2 Co-creating among stakeholders

The fact that the involvement of stakeholders enriches technology and software development has become mainstream in academic theorization of systems design. It has, especially, been hailed as a necessary requirement for the development of complex technologies that hold potential negative consequences for affected people and communities. In this line of thought, Alfrink et al. (2022) build on Hildebrandt (2019) and Almada (2019) to propose “agonistic approaches” for the development of AI systems that involves stakeholders in the early stages of the AI lifecycle and provide a possibility to identify potential problems before they manifest themselves in harmful actions.

Stakeholder involvement should not be a single or punctual intervention, however, but rather be structured as a constant and continuous process to be effective. Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) approaches such as integrated research (Spindler et al., 2020) can help to structure this process effectively. In the case of the project on AI police intelligence the authors worked in, the research and development process was explicitly designed to adhere to the idea of integrated research involving technical, practical and legal-ethical stakeholders collaborating at eye level. This means that ethicists and legal scholars made up one third of the entire consortium and they participated in all status meetings and many technical meetings at the working level. Moreover, ethical-legal challenges (algorithmic fairness, explainability, transparency, safety, human control, accountability) were already addressed in the initial research proposal and constitute a cornerstone of the entire undertaking (Brandner and Hirsbrunner, 2023). Contestability emerged as an important and sensible subject during the course of the project crucial for the facilitation of other values like justice, human control and safety.

One has to be aware, however, that participation (Bødker et al., 2022) and co-creation (Sanders and Stappers, 2008) do not automatically lead to better or ‘ethical’ software. Contestation and contestability design often involve conflictual social positions (e.g., between designers, entrepreneurs, data subjects and oversight bodies) that may not be resolved by the mere consultation with stakeholders. Nevertheless, we have argued elsewhere (Hirsbrunner et al., 2024), that AI technology development with conflictual parties can also be formally facilitated (‘infrastructured’) through accompanying technical structures (e.g., reflexive sessions, auto-ethnographic field notes, mapping of decision-making processes and interdisciplinary frictions).

5.1.3 Formalizing the translation from principles to practices for AI contestability

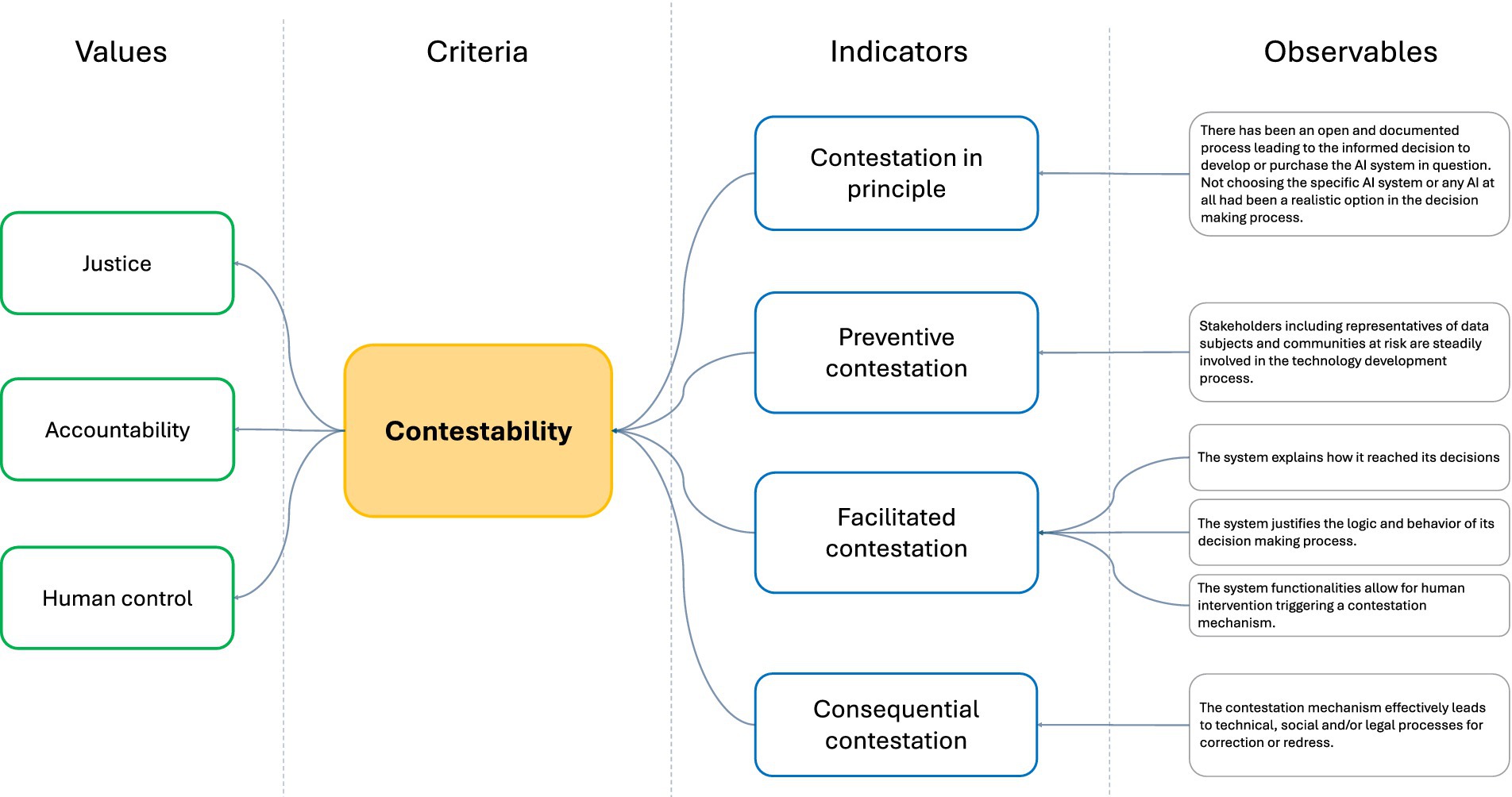

As AI systems become more and more embedded into aspects of social life, the more issues become part of the agenda of aligning AI systems design with human values. Such AI alignment is operationalized by translating normative guidelines into systems design mechanisms and governance measures. Scientists and other experts have proposed comprehensive models and procedures to bridge the principle-practice gap. One established approach is the VCIO (values, criteria, indicators, observables) model (Fetic et al., 2020) translating high-level values (transparency, accountability, privacy, fairness and reliability) into lower-level criteria, indicators and concrete observables. Alignment with ethical values is then tackled through a specified procedure going through comprehensive lists of questions and requirements, which is commonly referred to (and sometimes criticized) as a “checkbox ethics” approach (Kijewski et al., 2024).

In the EU, it can be anticipated that alignment practices will gradually shift toward a consideration of the principles addressed by the AI Act. We have observed this tendency within our transdisciplinary research projects toward AI methods and applications. The technical developers in these projects took the challenge of aligning their systems to ethical values seriously, but often highlighted that we should focus on the values addressed by legislation (e.g. AI Act, GDPR, Digital Services Act). In the context of the AI Act, the aligning process for high-risk applications of AI will soon be formalized through concrete obligations and formal requirements. Procedurally, this includes the instrument of the conformity assessment and multiple transparency obligations. Moreover, the provisions of the AI Act are currently concretized by multiple standardization bodies and instruments like the VDE SPEC 90012 for trustworthy AI (VDE, 2022), which is explicitly using the VCIO approach to translate values to concrete requirements. The idea is that adherence to, or refusal of, these detailed requirements can later be empirically evaluated and used as a tool for compliance and accountability assessments. This is particularly important since the AI Act establishes a conformity presumption with harmonized standards (Art. 40(1) AI Act). This means that developers and providers of high-risk AI applications adhering to these standards are presumed to be compliant with the regulation if the standards fulfill the conditions imposed by the AI Act.

Against this background, it particularly matters whether and how contestability is addressed in these normative instruments. The VDE Spec 90012 includes, for example, various provisions that support contestability, addressing issues such as transparency (e.g., documentation of datasets and model training, intelligibility of results, mechanisms enabling human oversight and human-in-the-loop), privacy (e.g., cybersecurity measures, review and rectification mechanisms) and fairness (stakeholder involvement, impact analysis, procedures evaluating and mitigating algorithmic discrimination, justifications, working and supply chain assessments, evaluations of ecological sustainability). Currently, such general tools for AI alignment are further tailored to particular AI application fields. An example in this direction is the DIN Spec 91517 on requirements for trustworthy AI methods in police applications, which has been co-developed by the authors (DIN, 2025). Moreover, the EU has recently published a first version a code of practice for general-purpose AI models, which will support the implementation of the AI Act’s rules for providers of general-purpose AI models and general-purpose AI models with systemic risks, together with the Guidelines on the scope of the obligations for general-purpose models (European Commission, 2025). For instance, these guidelines provide a procedure for an AI provider to contest the European Commission’s ex officio classification or designation of a general-purpose AI model, as being as a general-purpose with systemic risk. Another example are the standards and rules contained both in the code of practice and the guidelines for general-purpose AI models to comply with the obligation imposed by the AI Act of having a copyright right policy as well as compulsory summary about the content used for training that AI model (Art. 53(1)(c)-(d)). These obligations might favor some forms of contestation stemming from rightholders, but within the scope of the AI Act and EU law. Taking the VCIO model as a template, Figure 1 proposes a direction of how contestability in AI systems can be considered and accounted for. In our visual example, contestability would probably best be considered as a criterium that contributes to the accomplishment of multiple values like justice, accountability and human control. Strong contestability would, on the other side, be characterized by several manifestations (indicators) like categorical contestation of use, preventive contestation, contestation in interaction and contestation with impact. These indicators could then be further concretized by specific measures (observables) that include technical and governance-related aspects. In the description of indicators and observables, we used the term ‘contestation’ instead of ‘contestability’ to make clear that these items are understood as empirical entities (and not as normative ideals as in values and criteria).1

While AI alignment through lists and checkboxes is not an ultimate strategy for truthfully supporting contestability, it can, in combination with other activities, represent a valuable anchoring method to structure, monitor and document an engagement with contestability design throughout the development process. As a matter of fact, the detailed tables of checkbox AI ethics may, themselves, be considered valuable contestability devices: they provide stakeholders with tools enabling them to speak the language of AI developers, identify possible risks and flaws of AI products and spot possible directions for improvement.

5.2 Deploying organizations

The second type of practices concerns those in organizations deploying AI-powered decision making systems such as, companies, state authorities or educational institutions. This includes governing contestation in deployed systems, facilitating a culture for contestation and rejecting AI.

5.2.1 Governing contestation in deployed systems

The vast majority of the relevant scientific literature either highlights contestability in the design phase or specifies technical provisions aimed at supporting contestability in the deployment phase. A blind spot, however, appear to be empirical observations about how contestation unfolds in practice as soon as the AI systems are deployed and socio-technical assemblages of technology use and affect begin to take form. This is an obvious consequence of the fact that, fueled by technical breakthroughs and an entrepreneurial hype around generative AI, many AI systems are currently within the design phase while only few systems are already working for a considerable time. Many ethical challenges linked to AI systems only become apparent when the technology is deployed, used and embedded in social life. This is, for example, the case if AI systems employ active learning in which users help to retrain models by giving critical feedback and correcting the systems’ outputs. Human biases in the provision of this feedback may further exacerbate discriminatory stereotypes, which are already a part of the original training data and/or application domain (Fischer et al., 2022). In some cases, problems might only arise at a much later moment in time, e.g., when political conditions, infrastructural embedding or technological practices change. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm was designed to maximize watch time and engagement, surfacing content users were most likely to click on and continue watching. Over time, however, researchers and journalists found that the mode of operation of the recommendation algorithm also showed an (supposedly unintended) bias toward increasingly extreme, polarizing, and conspiratorial content (Knuutila et al., 2022).

In their categorization of contestation practices, Alfrink et al. (2022) emphasize the importance of quality assurance after deployment maintaining feedback loops enabling ongoing improvements. They do also mention risk mitigation strategies throughout the AI system lifecycle that “intervene in the broader context in which systems operate, rather than to change aspects of what is commonly considered systems themselves” (idem., p. 628). The authors do not, however, elaborate much further on this idea and the characterization lacks, in our opinion, the important link to issues of organizational governance. As a matter of fact, this governance perspective currently gains momentum as the AI Act demands the development and operation of risk management and quality assurance systems for specified AI application fields and risk categories. A risk management system maintained as a continuous iterative process planned and run throughout the entire AI lifecycle “requiring regular systematic review and updating” (Art. 9 AI Act) is required for high-risk AI systems, general-purpose AI models and general-purpose AI models with systemic risks. For the post-deployment phase, the AI Act also requires AI providers to put in place a quality management system next to the risk management system. The legislation sets out a minimum list of the elements that a quality management system for an high-risk AI system must contain and many of these provisions are intimately linked to practices, structures and mechanisms that influence the ability of stakeholders to contest the decisions, most notably procedures for reporting a serious incident, the existence of a communication system with authorities and stakeholders, a comprehensive record-keeping system and an accountability framework identifying responsibilities for the management and other staff (Art. 17(1) AI Act). Most high-risk AI systems will be subjected to internal control procedures which among others oblige AI providers to verify that the established quality management is in compliance with the requirements of the AI Act (Annex VI(2) AI Act). Examples like Meta’s Oversight Board, which also reviews automated decisions within the company’s products (e.g., content moderation), illustrate the potential for layered internal oversight systems to strengthen accountability (Laux, 2024, p. 2861).

5.2.2 Facilitating a culture for contestation

We have argued before that contestation is a practice that goes far beyond the scope of individual AI systems and life cycles. It can be understood as a critical organizational practice and culture, which takes a long time to build and considerable resources to maintain. At this stage, it also seems productive to critically engage with the meaning of ‘practice’ in existent conceptualizations of AI contestability. As a matter of fact, it appears that existent categorizations of AI contestation practices treated ‘practice’ as an umbrella term for various phenomena that go beyond technical mechanisms and specified work flows. Contributions from social science research fields, however, often have a more distinctive view on ‘practice’ that shows certain differences to those articulated by computer scientists and design researchers. For instance, such scholarship typically refers to Schatzki’s characterization of practices as “embodied, materially mediated arrays of human activity centrally organized around shared practical understanding” (Schatzki et al., 2001, p. 2). This general characterization has been further concretized and differentiated for multiple social contexts, which includes the contributions mentioned in chapter 5, such as quality control and whistleblowing practices that bear similarities to contestation practices. The definition by Schatzki and consideration of contestation as such an “array of human activity” supports the argument that these practices will mostly emerge and operate outside the frame of individual systems, life cycles and fully formalized procedures.

Alfrink et al. (2022) make a valuable effort to identify such activities in their description of risk mitigation measures including training and education efforts showing users how the system in question works and what limits and possible risks are to be expected. This characterization also demonstrates, however, that the authors mainly remain in the perspective of individual systems design, the temporal logic of the AI life cycle and the developer-user relationship. This perspective is important, but taken in isolation, it might marginalize the importance of practices focusing on the structural empowerment of stakeholders (not just users) to understand and challenge AI systems – being it in the phases and positionalities of development, deployment, use, supervision or passive affect.

As a complement to risk mitigation within the logic of individual systems design, we want to highlight the need for a contestation culture within organizations that aims at improving the structural capabilities of stakeholders to challenge AI systems more generally. Guidelines and frameworks for AI contestability-by-design are meaningless if the actors in the field do not have the necessary capabilities to understand, organize and enact contestability in practice. The establishment, organization and maintenance of such empowerment to contest is an endeavor that will take much time and effort. Similar to recommendations describing contestability mechanisms within systems design, best practices focusing on institutions may support the latter to assess their existing capacities for contestation, identify blind spots and propose effective means for improvement. An example in this direction is the organizational roadmap and risk assessment survey published by the law enforcement agency Interpol and the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI). The comprehensive document aims at providing an overview of and guidance on the organizational components that may be conducive to responsible AI and to improve the organizational readiness of law enforcement agencies employing AI systems. Its target audience includes senior officials in law enforcement authorities, police experts for technology application in law enforcement as well as stakeholders (Interpol/United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2024). Very aptly, the authors highlight the importance of multiple competences for responsible AI including technical, domain-, governance- and socio-cultural expertise. While the document does not explicitly refer to contestation abilities within organizations, it emphases the need for a risk management policy that should describe the approach to assess and address risks related to the implementation of AI systems and specify the staff members or units in charge of specific tasks, the respective risk owners as well as the timing and financial and organizational resources allocated to risk management (idem., p. 24). The organizational roadmap is supplemented by a risk assessment questionnaire consisting of 24 questions and a procedure to evaluate the findings of the checklist (Interpol/United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2024a and Verband der Elektrotechnik Elektronik Informationstechnik (VDE), 2022). In contrast to the main document of the roadmap, the questionnaire explicitly includes questions regarding the contestability mechanisms in place. Namely, questions 22 and 23 ask how likely is it that a lack of technological and/or organizational measures to allow AI system’s users (question 22) or the people affected (question 23) to challenge its outputs will have a negative impact on individuals or communities. Question 24 then asks how likely it is that insufficient access to redress for those who suffer negative effects as a result of the use of the AI system will have a negative impact on individuals or communities. The questionnaire also enumerates possible consequences of disregarding contestability.

For users, these consequences include failures, inaccuracies and biases of the AI system remaining undetected and uncorrected, discriminatory practices not being identified and addressed and the erosion of public trust in the law enforcement agency and AI due to the inability to raise perceived or alleged human rights violations. For affected people, then again, negative impact of insufficient access to redress may manifest itself as a breach of the right to access to justice and redress to those who claim to have suffered human rights violations as a result of the use of the AI system, unequal access to effective judicial remedies by certain individuals in the absence of adequate procedures to allow groups of victims to present claims for reparation and a feeling of unsafety and physical and psychological distress by those who are affected by the use of the AI system or their relatives (Interpol/United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2024, p. 23 f). Of course, there is still a long way to go from the acknowledgement for such questions to actual strategies to address them, but it shows the sensibility of the authors to tackle the challenge of AI contestability within organizations.

For the future, it will be crucial to underpin conceptualizations of contestability with empirical observations of how contestation of AI unfolds in practice. Equally, it may be particularly productive to observe situations in which contestation is impeded or where it is realized in a way unanticipated by contestability designers. Approaches from STS studying instances of breakdown in socio-technical settings (Star, 1999) might offer particularly well-suited avenues and methods (e.g., ethnography, including participant observation) to explore this direction and further our understanding of the way people challenge AI. This will, ultimately, help to create more effective guidelines and design features facilitating contestation in AI.

5.2.3 Rejecting AI

Existing conceptualizations typically start after the decision that an AI system shall be developed to tackle the particular problem or needs of a target audience. A fundamental moment of AI contestability may, however, be the decision to contest the very idea of using AI or developing or acquiring a particular AI system. We can illustrate this, in the following, with the issue of procurement. Indeed, one of the earlier stages in the procurement of AI technologies is to identify and justify the actual need behind the purchase of such systems and to specify the requirements that come with it (Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum, 2023, p. 3). From a socio-legal perspective, it is generally not clear whether procurement procedures can be effectively challenged, especially by third parties not involved in such procedures, even if they concern the future development and deployment of AI systems for public purposes (see, for instance, NIST, 2024, p. 48, A.1.3.).

Notably, the procurement of AI systems may fall under the scope of application of international conventions and EU law, as in the case of the Council of Europe Framework-Convention on AI and Human Rights, but which applies only to public authorities or private actors acting on their behalf from Member States of this Convention (Council of Europe, 2024a, 2024b). However, an open question is whether the applicability of, for example, this Convention-Framework to the procurement of AI systems can lead to the possibility of contesting the very reasons underlying the existence of a procurement procedure (and the decision behind them, i.e., whether one needs a particular AI system or application for AI systems and models). Notably in highly sensitive AI fields of activity, such as for security purposes, the secrecy that prevails in government procurement practices for private firms has a high negative impact on the very possibility of deploying AI contestation social practices (Friedman and Citron, 2024; Matulionyte, 2024). These issues affect also procurement procedures in commercial sector of activities. A study by the Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum has highlighted some of the problems that prevent effective transparency in procurement, as buyers may lack the technical expertise to effectively scrutinize the technologies to be purchased, while suppliers may limit the information they share with buyers (Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum, 2023). This can seriously undermine the ability to contest internally or externally a procurement process for the acquisition of an AI system or model. Among issues that might severely impede transparency of algorithmic system procurements between “buyers” – under the AI Act, either AI importers, AI distributors, AI deployers or users – and “vendors” – (AI providers), some of the factors explain why it is even harder to contemplate contestation by third parties not involved in those procedures. For example, there is often insufficient information from vendors on how legal or ethical requirements have been met during the development of the technology (e.g., representativeness and relevance of the training data), which can prevent buyers from making an informed judgment about whether the technology is appropriate for their context. Moreover, the commercial confidentiality of vendor-specific information may inhibit independent testing of technologies procured by a buyer (DRCF, 2023, p. 5).

5.3 Enabling external oversight and critical monitoring

The practices identified so far operated from within circles of AI development, deployment and use. An important mode of contestation, however, arises explicitly from the detachment from the system and its principal actors – namely, the mode of contestation undertaken by external oversight actors and corresponding mechanisms. Such external contestation can be facilitated through second-degree oversight mechanisms such as audits, reviews, and appeals, which are designed to address errors or harm caused by AI systems or AI models. It can be carried out either on the basis of a formal legal mandate or as a commitment to the civil duty within processes of democratic governance.

The AI Act introduces a comprehensive regulatory framework for the placing on the market, monitoring, and use of AI systems in the EU. Central to its architecture is a risk-based system of governance, in which member states are required to designate market surveillance authorities and notifying authorities to oversee compliance (Art. 70 AI Act). While the regulation allows flexibility in most sectors, it limits member state discretion in particularly sensitive domains involving fundamental rights, including high-risk applications, general-purpose AI models and general-purpose AI models with systemic risks.

For most high-risk AI systems, providers are required to implement internal governance mechanisms, including risk management, documentation, post-market monitoring, and regular internal audits (see for instance obligations in Arts. 9–17, 43(2) AI Act). These internal mechanisms aim to ensure compliance at the design and deployment stage and reflect the regulation’s reliance on provider responsibility. However, in particularly sensitive area of biometric identification, internal audits have to be supplemented by external conformity assessments carried out by notified bodies (Art. 43(1) AI Act) and ongoing post-market surveillance by other competent authorities. These audits provide several key benefits: acting as watchdogs, ensuring oversight against practices such as audit washing and misleading assurances; they challenge existing standards, helping to prevent the decoupling of audits, a concern seen in financial auditing, and they adapt effectively to emerging technologies.

Moreover, Hartmann et al. (2024) argue, that third-party audits by research organizations and civil society could play a crucial role in establishing a robust AI oversight ecosystem. These audits provide several key benefits: like acting as watchdogs, ensuring oversight against practices like audit washing and misleading assurances; they challenge existing standards, helping to prevent the decoupling of audits, a concern seen in financial auditing, and they adapt effectively to emerging technologies (idem., p. 16). Given the last two points, third-party audits gain additional importance by scrutinizing evolving standards and raising critical questions. Moreover, they foster a deeper understanding of sociotechnical systems and address the concerns of affected communities. Finally, third-party audits and their access to information on data, models and systems help counteract the information and power imbalances inherent in the platform economy (Ibid.).

It would be beneficial for the various interest groups that interact with the formal control authorities, like the notifying authorities, to be represented within these authorities themselves, wherever feasible. This would allow a multidisciplinary mix of actors comprising tech-savvy AI experts, representatives of those affected, legal experts and representatives of civil society to safeguard compliance to legislation and standards as well as supporting the protection of fundamental rights of data subjects. It would, however, also require the implementation of comprehensive transparency measures to guarantee explainability, effective control and, ultimately, fair decisions. It is the responsibility of developers and providers of AI software in the safety sector to create standardized formats that will enable experts in supervisory authorities to obtain the necessary information regarding an AI system (Kleemann et al., 2023).

6 Discussion

Building on the practices identified in the former chapter, we identified a number of broader issues with existing conceptualizations of AI contestability and evaluate to what extent insights from the social sciences can help to supplement these perspectives.

6.1 Disentangling different motivations for AI contestation practices

Scholars researching aspects of AI contestability point out good reasons why contestability matters or should matter when designing AI systems. For Alfrink et al. (2022, p. 615), for example, the motivation to enable contestability in AI is to “protect against fallible, unaccountable, illegitimate, and unjust automated decision-making.” This characterization is undoubtedly correct, but it does not consider the equally realistic fact that actors have different motivations to support contestability as a useful strategy to achieve these goals. To invoke Schatzki’s conceptualization again, practices are co-determined by specific teleoaffective structures (2002, p. 80). Set, communicated and perceived objectives (teloi) influence what practices are and how they are entangled with other practices.

Teleoaffectivity describes a structure of normativized and hierarchically ordered ends, projects and tasks, as well as emotions and moods to be associated with a practice.

As we want to argue, the fact that actors have different interpretations, conflicting motivations and multiple justifications for engaging with contestability can lead to unforeseeable consequences for the accomplishment of the latter. Contestation can generally be considered as a practice of critique and intervention in situations perceived as problematic or wrong. The evaluation, however, that something is not right might be based on various considerations of a concrete situation. In the context of AI-enabled algorithmic decision-making, we may differentiate two types of motivations:

On the one hand, one might thrive for contestability in a view of aligning systems better with human values in order to improve their societal acceptance. The experience of the last few years has shown that sensibility for ethical challenges within AI software design can actually lead to better technology that protects the rights, interests and needs of affected communities. Contestation can, accordingly, also be seen as a feature that mitigates the multiple risks associated with AI-based systems and eventually improves the robustness and trustworthiness of software. As an example, active learning techniques in AI may facilitate better control of software on behalf of the user, which can also include a reparation of ethical disgraces (Fischer et al., 2022).

On the other hand, contestability in AI can be more categorical than procedural. It is often argued that important aspects of the human personality are neither mathematically describable nor computable. Put otherwise, it seems that computers often get it wrong when they describe the character or a complex behavior of human beings. It can be argued as a matter of normative ethics that human beings might lose their sense of autonomy necessary for living a good life if machines increasingly influence and guide human activities (Hildebrandt, 2019).

These different motivations can unconsciously influence the way contestability is thought through and fought for. They can, however, also be represented more explicitly in terms of voiced justifications within practices of contestation. To speak with the words of practice theorist Luc Boltanski, the practice of contestation in literature mentioned above is motivated by different overarching values or principles of justification. The first type of justification for contestability in AI (‘building better systems’) is motivated by the principles of reliability, efficiency and technical performance, whereas the second type of justification (‘incomputability of the human being’) belongs, in Boltanski and Thévenot’s (2021) words, to the cité civique, the civic order emphasizing values like autonomy, justice, participation and democratic oversight. Boltanski and Thévenot’s typology includes six orders of justification that guide social practices including the civic order, the industrial order, the market order, the domestic order, the order of fame and the order of inspiration.

The anchoring of strategies of contestation in different orders of justification might lead to different conclusions, strategies and practices among key actors. From the perspective of a system designer, contestability is interpreted and justified as a means to make the system in question better and, therefore, more successful. As a consequence, she or he might not consider the option to discard the system development in case that a satisfactory level of effective contestability cannot realistically be reached. From the perspective of the designer, this option would be tantamount to failure (both in terms of industrial performance in the cité industrielle as in terms of recognition in the cité de l’opinion). Accordingly, it is difficult to imagine a design framework that considers the option to terminate the design process due to insufficient possibilities to enable effective contestation. In the case of affected communities, deploying institutions and overseeing agencies, the situation is different. Here, actions leading to the termination of a design or deployment process are perfectly conceivable and may in some cases be considered as best available options. The different positionings of -what we might call- constructive contestation practice versus an antagonistic contestation practice and resulting coping strategies stand, therefore, in a tense relationship with each other, which is often difficult to resolve in practice.

6.2 Broadening the scope of actors practicing contestation in AI

As highlighted in the related work section above, contestability is mostly conceptualized as an interplay between normative principles and their translation into technical design. This interplay gives those who define the rules and those who translate rules into technical system features a preferential position over other stakeholders. As a matter of fact, the often-evoked importance of ‘stakeholder involvement’ supports rather than attenuates such a reading: stakeholders are people and entities who may be consulted and sometimes involved more profoundly in the project development process, but this participation mostly remains punctual for multiple reasons. This includes limited access to stakeholders, limited funding preventing realistic participation opportunities and fuzzy stakeholder categorizations. The central actors, however, are the system designers who may, or may not, decide to involve others in their AI systems development. This view is also supported by dedicated approaches and methods such as Value-Sensitive Design (VSD) (Friedman and Hendry, 2019), which are targeted to system designers who then organize the involvement of ‘others.’ The central position of system designers that is mediated by this setting may, however, exaggerate the agency that software developers have in the assemblage of an AI system. If one takes the often proclaimed characterization of AI and other algorithmic technologies as ‘socio-technical’ systems seriously (Baxter and Sommerville, 2011; Boyd and Crawford, 2012), one is advised to put this privileged attribution of power to designers into question. The same is true for the central position of those defining normative principles on a legislative and policy level. These actors (e.g., legislators, administrators, standardization bodies) may have some leeway to define abstract rules, but their impact on concrete systems is less clear-cut. In contrast, it seems only plausible to attribute a more preferential position of power to actors like company senior officials and sales manager, compliance officers or, outside the company, representatives of standardization bodies and controllers of supporting infrastructure (e.g., cloud-hosting, data annotation platforms). Greater consideration of such actors would take account of the observation that the development and deployment of AI systems are particularly confronted with the problem of many hands distributing responsibility among multiple actors (Thompson, 2017). The controller of a supporting cloud infrastructure (e.g., Amazon Web Services) or market access points (e.g., Apple Store) may have strong possibilities to ‘contest’ a particular systems design, even though this practice of contestation will rarely be considered as such. Equally, it may be argued that normative documents and technological entities may themselves represent non-human actants with a power to challenge the specific design, deployment or use of an AI system.

6.3 Contestation practices are not in sync with the AI life cycle

The previously discussed points of limitation (relevance of conflicting motivations, justifications and resulting practices of contestation, preferential role of designers and official rule makers) also lead to another bias in the conceptualization of contestability in AI, which is the dominant frame of the ‘AI lifecycle’ to capture possible contestation moments and practices. Several contributions from design researchers highlight the importance to address and enable contestability throughout the complete AI lifecycle. This focus on one system cycle is understandable considering the design perspective of many of frameworks of AI contestability, which mostly have software designers in mind as their target audience and their task to design one system in a responsible way. These authors rightly emphasize that contestability is not something to think about sporadically or ex-post, but that it should be systematically considered within all stages of an AI system’s life span, including use case development, the design phase, training, testing and deployment. Consequently, these frameworks do not sufficiently account for activities that occur prior to the start of a development project (or after the cessation of a product’s use). This includes all sorts of institutional measures supporting the organization readiness to challenge aspects of AI technologies. It also affects formalized processes within organizations like the procurement of software and accompanying services. Of course, the authors of contestability conceptualizations from the field of design and HCI may well be aware that their frameworks are ill-equipped to guide organizations in their pursuit of contestation capabilities. The fact, however, is that stakeholders like organizational AI-users, oversight authorities and civil society actors may nevertheless rely on these contestability frameworks structured by the AI life cycle frame because there are currently no other conceptual models to rely on. In our opinion, however, it would be pivotal to consider elements and processes that happen between AI life cycles and may adhere to other temporal logics and time frames. In particular, this may help to consider more realistically the relevance of organizational, communicative and cultural practices, structures and safeguards within and among institutions, which may decide on the real manifestation and possibilities for AI contestability.

6.4 Contestation as situative critique and ethico-political practice

Existing characterizations of AI contestability typically work with an implicit objective to formalize instances of contestation within processes of AI development, deployment, use and oversight. This is equally true for contributions from the field of law as for those from the field of design. Legal studies tend to translate implicit values and norms into explicit regulatory frameworks, legislations and concrete rules. Engineers and computer scientists, then again, aim at translating abstract design principles (often inspired by legislation) into concrete technical mechanisms, procedures and workflows. Such activities are highly valuable and have a strong impact to make the use of AI-supported in multiple domains ethically more responsible. They may, however, fall short to capture the often situative, bottom-up character of contestation as a social practice. We can, for example, discuss whistleblowing as an exemplary practice of contestation to make this aspect clear.

Weiskopf and Tobias-Miersch (2016) differentiate two different configurations of organization for whistleblowing: vertical and horizontal. In its vertically organized manifestation, whistleblowing is institutionalized and channeled authoritatively. On the one hand, this means that it is also expected, intended and formalized. It typically defines terms for legitimate contestation such as the “possible content of critique, the legitimate speaker, the legitimate addressees, the circumstances under which critique may occur and the modality in which it has to be articulated” (Weiskopf and Tobias-Miersch, 2016, p. 1636). In its horizontal ‘bottom-up’ manifestation, in contrast, whistleblowing can be seen as a form of parrhesia (Foucault, 2001), “an ethico-political practice that opens up possibilities of new ways of relating to the self and others (the ethical dimension) and new ways of organizing relations to others (the political dimension)” (Weiskopf and Tobias-Miersch, 2016, p. 1622). Parrhesiastic critique is situative, not formalized and independent from institutional support.

This differentiation of institutionalized versus situative practices of critique is also relevant in the context of AI contestability. As a matter of fact, existent conceptualizations of AI contestation practices seem to focus mainly on institutionalized procedures and workflows of critique. This is a logical consequence from the aforementioned constellation to conceptualize contestability as an alignment between normative rules and design features. This may, however, marginalize the often informal, parrhesiastic character of contestation practices. As discussed in the STS literature (Henderson, 1991), software users have always been creative in finding workarounds when official technological processes do not function properly or fail to meet their needs. Equally, it would be productive to investigate how stakeholders may elaborate situative, ethico-political practices to challenge and contest AI mechanisms or decisions in case that official, formalized ways of contestation do not function properly or are non-existent.

7 Conclusion

Contestability is a key concept in efforts to make AI more responsible, ethical and safe. This is particularly the case for high-risk applications of AI for which errors and otherwise problematic outputs and features potentially lead to severe negative consequences for data subjects, users or other stakeholders. In our article, we proposed to critically evaluate the following limitations of contestability conceptualizations for the AI context: with its focus on systems design, the existing conceptualizations operate within the frame of individual systems design. Most notably, the well-established AI lifecycle frame in engineering and regulation acknowledges the heterogenous stages and actors involved in conceptualizing, designing, training, testing, deploying, using and maintaining the socio-technical ML systems. This frame is, however, poorly suited to capture elements of contestability that lie between individual lifecycles or involve otherwise structured temporalities. Related to that, established understandings of AI contestability typically start from the perspective of the designer and tend to see actors outside of the design circle as recipients and users of contestation mechanisms. This focus is completely justified from the perspective of a system design process. However, it inevitably leads to the activities of external stakeholders being seen solely as a source of impetus for system design while other important structural constellations and activities of stakeholders are being neglected. This includes, for example, activities like institutional mechanisms and capacity building measures within stakeholder organizations that are extremely important to enable AI contestability within the frame of good governance and civil society empowerment. Moreover, existing conceptualizations typically work within the logic of formalized and institutionalized contestation avenues conceived as translations of procedural rules into interactional mechanisms within the functionalities of AI systems. While such formalized circuits of functionalities and behaviors make sense from the perspective of systems design, it ignores the sometimes implicit, informal, situational, repetitive or dogmatic character of contestation.

As a result, we have proposed a shift in attention for future research investigating AI contestability, namely from a system-centered, life cycle-focused and developer-oriented views toward a stronger consideration of critical, organizational and situative practices and a contextualization within concrete normative boundary conditions. Future studies incorporating this shift in attention will hopefully help to inform contestability principles with empirical perspectives evaluating instances of realized contestation in practice and more fine-grained recommendations for normative instruments, design features, governance and oversight mechanisms.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MT: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding