- Faculty of Psychology in Wrocław, SWPS University, Warsaw, Poland

Ad avoidance is one of the most persistent challenges in online advertising, with users increasingly employing ad-blocking software or developing habitual strategies to ignore marketing content. One promising solution is to shift from passive advertising formats to interactive ones, which actively engage users in the communication process. This article introduces questvertising, a novel interactive advertising format designed to reduce ad avoidance by offering users a brief, engaging task in exchange for access to desired content. In a typical questvertising scenario, instead of being asked to purchase access to gated content (such as an article or video), users are presented with a short branded message followed by a multiple-choice question based on that message. A correct answer grants immediate access to the content—at no cost—thus integrating the ad experience seamlessly into the user journey. We tested the effectiveness of questvertising in a field study promoting a new coffee brand, Colibri Café (N = 11,006). Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: a standard display banner, a single questvertising exposure, two spaced questvertising exposures, or a no-ad control. Brand awareness and associations were measured 26–51 h later. Results showed that a single questvertising exposure nearly doubled brand recall compared to the banner condition (59.0% vs. 31.2%), while two exposures increased it to 68.3%. Questvertising also significantly enhanced brand associations with South American origin (57.8–68.2% vs. 36.4%) and positive affect, with up to 30.1% selecting Colibri Café as the most appealing brand, compared to only 3.9% in the banner group. Traditional display advertising showed no significant advantage over the control. These findings demonstrate the considerable potential of questvertising as a more engaging and effective format of interactive advertising, particularly in combating ad fatigue and enhancing brand outcomes.

Introduction

According to the rule, which states that “Sale starts where the eyes stop” (Aitchinson, 1999), it is commonly believed that an ad should be attractive to the senses of the target audience. However, in the conditions where an average person receives, on daily basis, a staggering number of unsolicited advertisements, it is incredibly difficult to achieve. And while there is no evidence to suggest that our attention capacity increases along the development of our civilization, there are no doubts as to the fact that the number of advertised brands, products and advertisements as such increases consistently and at a very dynamic rate (Thales et al., 2014; Leeflang et al., 2014; Kumar and Gupta, 2016).

Nowadays, the Internet is the environment where a lot of such advertisements are published. Eye-tracking studies, which consist of tracking the eye movements in participants sitting in front of a laptop, tablet or smartphone, clearly demonstrate that consumers actively defend themselves against such ads by simply avoiding or minimizing their exposure to such advertisements (e.g., Filiopoulou et al., 2019; Santoso et al., 2020). According to Cho and Cheon (2004), there are at least three reasons for this. First, advertisements are intrusive from the perspective of the content the consumer is interested in – they disrupt or stop the inflow of information that the consumer considers important at the given moment. Second, consumers are exposed to a large number of advertisements and thus they do not know which ones might, at least potentially, be of interest to them. Third, most people have a negative experience with advertisements that are often misleading. It should be noted that while the second and the third reason applies to basically all advertisements, the first one is particularly important in the case of Internet ads. This is because an Internet ad is displayed almost exclusively on a webpage that, at that given moment, contains content in which the consumer is much more interested.

And thus, even though Internet advertising is undoubtedly the most dynamically developing marketing area (e.g., Jain et al., 2016; Ma and Du, 2018) and the Internet is where the advertising industry spends an increasing share of its budget (instead allocating their money to TV commercials, outdoor advertising or ads printed in papers) (e.g., Mohammed and Alkubise, 2012; Enberg, 2019), the actual effectiveness of Internet advertisements is not that obvious (e.g., Kumar et al., 2016; Ma and Du, 2018). It is nevertheless relatively often the case that people responsible for marketing campaigns fail to account for this and incorrectly assume that the sheer fact that an ad for a brand or a product is displayed on a consumer’s screen means that the content of the ad reaches the consumer and consequently persuades the consumer to purchase the product (e.g., Kireyev et al., 2016). Meanwhile, due to the fact that people actively avoid such ads and that precisely when such ads appear in the consumer’s field of perception their attention is focused on something completely different (e.g., Baek and Morimoto, 2012; Niu et al., 2021; Celik et al., 2022), Internet advertising faces a serious challenge, which is how to make sure the ad being presented to the consumer actually reaches them and builds or modifies their attitude.

In this article, we introduce a completely new form of online advertising, which we refer to as questvertising. The term is a portmanteau of two words: quest and advertising, with the latter shortened to-vertising. Questvertising can thus be understood as a form of advertising that engages the audience by prompting them to answer questions.

Questvertising–a novel format of interactive advertising

One of the classic domains of social psychology involves the study of social influence techniques that enhance the likelihood of individuals complying with requests or proposals. Through extensive experimental research, psychologists have identified and empirically validated the effectiveness of several such techniques (see Cialdini, 2021; Dolinski, 2016; Dolinski and Grzyb, 2022 for reviews). Interestingly, the effectiveness of these techniques tends to increase when preceded by a brief, conventional exchange between the requester and the potential respondent. For instance, Cialdini and Schroeder (1976) observed that individuals frequently refuse to donate to charitable causes. They hypothesized that this refusal is often internally justified by thoughts such as, “I’m not wealthy enough to help everyone in need.” While such reasoning may serve to rationalize inaction, Cialdini and Schroeder proposed that this justification could be disrupted by including a simple, legitimizing paltry contribution phrase in the request—specifically, “even a penny will help.” Their study demonstrated that this minor addition significantly increased the number of people willing to donate, without affecting the average donation amount. In effect, a few seemingly trivial words nearly doubled the total funds raised for the cause.

Further research by Dolinski et al. (2005) showed that the effectiveness of this technique is amplified when preceded by a short interpersonal interaction. For example, asking someone how they feel and briefly acknowledging their response before making the request further increased compliance rates.

Another well-established social influence technique is labeling. Simply informing an individual that, for example, their responses to a psychological test suggest they are kind and thoughtful has been shown to increase their likelihood of helping others in the near future (Strenta and DeJong, 1981). However, as with other techniques, the effectiveness of labeling is significantly enhanced when it is preceded by a brief, conventional dialogue with the individual (Grzyb et al., 2021).

The positive role of pre-dialogue has also been demonstrated in relation to the mimicry effect. A substantial body of research shows that subtly mimicking another person’s facial expressions, gestures, or verbal expressions increases the likelihood that the individual will later comply with requests (see Genschow and Oomen, 2025, for a review). Kulesza et al. (2016), however, found that this effect becomes even more pronounced when the mimicry is preceded by a short dialogue on a neutral topic.

What accounts for the effectiveness of this pre-dialogue? One key feature of dialogue is the formation of reciprocal interaction between two individuals. The person receiving the request is no longer a passive participant—they have already been engaged through a direct question, have responded, and have heard a comment related to their answer. This interaction establishes a minimal but meaningful social connection.

Advertising, too, functions as a form of social influence. Unlike the individualized techniques mentioned above, however, advertising typically targets broad audiences rather than specific individuals. Traditional advertising is often passive: the recipient simply receives the message without any interaction. Yet, advertising can also be designed to foster interactive engagement between the sender (advertiser) and the receiver (consumer). Indeed, one of the most crucial determinants of advertising effectiveness may be the degree to which it creates an interactivity.

The scientific literature on advertising frequently highlights the lack of a consistent and universally accepted definition of interactivity (e.g., Kiousis, 2002; Gao et al., 2010; Jensen, 1998). This ambiguity arises primarily because different scholars emphasize different aspects of the advertising experience. Some focus on the technical features of the advertising medium (e.g., Schneiderman and Plaisant, 1987; Steuer, 1992), others on the prior experiences and engagement of the audience (e.g., Belanche et al., 2017b), and still others on the emotional arousal elicited by the advertising message (Belanche et al., 2017a).

Nonetheless, many studies—either explicitly or implicitly—underscore the importance of dialogue-like interaction in advertising. For example, Belanche et al. (2020) argue that social media platforms allow recipients of advertising to share and compare their experiences with others, effectively enabling a digital form of word-of-mouth marketing. Moreover, consumers actively seek additional information about advertised products through manufacturers’ platforms. These forms of interactive advertising are generally more effective than traditional, one-way communication formats.

Hussain and Lasage (2013), in their research on why internet users install ad-blocking software, identified three primary factors contributing to ad avoidance. The first is the lack of relevance of advertisements to users’ personal needs. The second is the lack of perceived authenticity in advertising content. The third—particularly relevant to this discussion—is the perceived absence of interactivity in advertisements. While the first two issues may be difficult to address due to individual differences and the challenges of tailoring content, increasing the interactivity of advertising is comparatively more feasible. Several practical strategies can enhance interactivity: offering hyperlinks to additional information, allowing users to skip or exit the advertisement at will, or enabling them to choose the length or format of the ad from multiple options.

Returning to the earlier discussion of interactivity understood as dialogue, it is worth highlighting a study in which factorial analysis identified six variables influencing the perceived interactivity of mobile advertising. However, it should be emphasized here that the key factor proved to be the interpersonal communication. This perspective is also strongly supported by Kiousis (2002), who asserts that interactivity in advertising involves a series of communication exchanges between the sender and the recipient. In this context, we introduce questvertising as a novel form of online advertising, presented here for the first time in the academic literature. This format is explicitly built upon a dialogic model of communication between the sender and receiver of an advertising message. Questvertising is particularly suited for situations in which users are consuming online content—such as reading an article, watching a video, music concert, film, or comedy performance—and are subsequently prompted to purchase access in order to continue. Instead of requiring a direct payment, questvertising offers an alternative means of compensating content creators and copyright holders through advertising revenue—without triggering strong negative emotional reactions typically associated with ad interruptions. Specifically, a brief promotional message about a product is displayed on the screen, followed immediately by a multiple-choice question (usually with three options). To answer correctly, the user only needs to read the short note above. Upon selecting the correct answer, the user is granted immediate access to continue the content without further delay.

As a result, questvertising is a formula that is beneficial to those on both sides of the communication process: the advertiser is able to reach the consumer with its message and the consumer gains access to the content they are interested in at a low cost (i.e., minimal effort and minimal time required to answer the question).

The empirical research conducted so far (Dolinski and Grzyb, 2019a,b) clearly indicates that the effectiveness of the same advertisement is several times higher when the consumer is exposed to the ad through questvertising than in the case of traditional display ads. The recognition of unknown brands created for the purpose of the experiment was, on average, 3.6 times higher when questvertising was used and reached 28.7% following a single engaging in the ad-based quest. The advantage over a traditional ad was also maintained after 1 week–11.6% vs. 4.5%. At the same time, a higher level of sympathy was observed for the brand promoted through the use of questvertising.

Another crucial aspect observed in the course of the above-mentioned studies is the fact that the appearance of a questvertising ad was subjectively less aversive (less annoying) for the consumers compared to the appearance of the same ad in the traditional form (i.e., display).

Method

Even though the empirical studies designed to determine the effectiveness of questvertising ads compared to display ads conducted so far (Dolinski and Grzyb, 2019a,b) fully adhered to methodological rigorism, they were conducted in such conditions where the research participants knew they were participating in a study. Studies conducted in a natural context, where people are not aware they are participants in a study, are undoubtedly more valuable and reliable (Grzyb and Dolinski, 2022). Therefore, it was assumed that our participants, in the course of their spontaneous activity on the Internet, would be exposed to both display and questvertising ads without knowing that their reactions were being analyzed. It should be noted that this procedure does not violate the ethical principles of conducting studies, as the APA Code of Conduct allows omission of obtaining a declaration of informed consent for participation in such studies in similar situations.

The preparations for the studies began with the creation, from the ground up, of a new coffee brand, i.e., Colibri Cafe. A logo was designed for the brand as well as a draft of an ad for the product. The ad suggested that the face of the brand and the person promoting the product is Victor Alva (fictional character with a South American appearance presented as a coffee gourmet). The coffee was also physically prepared for sale. The assumption was to compare the effectiveness of the display ad and the questvertising ad on actual web portals. A decision was made to use one web portal used predominantly by women (Polki.pl) and another one used predominantly by men1.

The assumption was that the studies would compare the awareness of the Colibri Cafe brand (e.g., Do you know the name of the new coffee from the heart of South America with Victor Alva?) in the conditions of a traditional display ad vs. questvertising, as well as the associations between the Colibri Cafe brand and both non-existent brands (Flamingo Cafe and Tucano Cafe) and (in other study groups) with existing brands that are commonly known in Poland (Jacobs, Lavazza and Tchibo), where the study was being conducted. The participants were asked which of the brands they associated most with South America and which of the brands evoked the best emotional associations in them. These effects were further tested following subsequent releases of questvertising-type ads.

The studies were conducted in February 2023 on two major Polish web portals for both women (polki.pl) and men (see footnote 1). The participants were randomly assigned to one of the following four groups:

a. Control group –no exposure to any ads

b. Display group –exposure to the traditional display ad

c. Experimental group No. 1 – single exposure to the questvertising ad

d. Experimental group No. 2 – double exposure to the questvertising ad

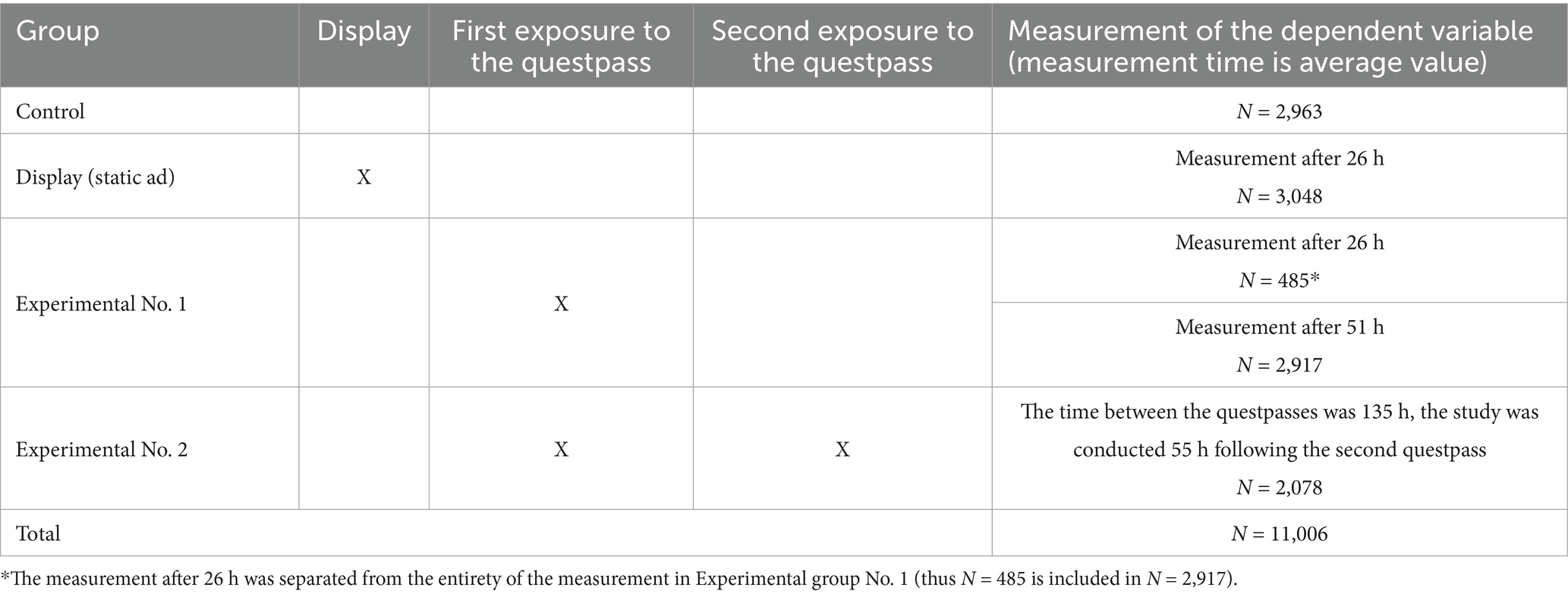

In total, the study comprised 11,006 participants. The specific number of participants in each of the groups is presented in Table 1. The table also includes detailed information on (average) intervals between particular stages of the study.

Participants were assigned to the experimental groups at random; consequently, randomization alone determined the material to which they were exposed. In the Display (static-ad) condition, they viewed a conventional banner advertisement embedded in the web page, which entered the participant’s field of vision after roughly 20% of the article had been read (see Figure 1 for an example of such a banner on the mobile version of “polki.pl”).

In the questvertising conditions, the banner displayed the question “Jak nazywa się kawa z serca Południowej Ameryki od Victora Alva?” (“What is the name of the coffee from the heart of South America by Victor Alva?”) together with three response options - Colibri Café, Flamingo Café, and Tucano Café. Clicking the correct answer allowed the participant to continue reading the article. Figure 2 illustrates such a questvertising banner.

Questvertising of this identical format was presented to participants in both Experimental Group 1 and Experimental Group 2; the only difference between the groups was that participants in Experimental Group 2 encountered the banner twice. It is important to emphasize that our primary interest lay in comparing a traditional form of online advertising (the Display group) with the single-exposure questvertising condition (Experimental 1). The Experimental 2 group was included to examine whether the effects of questvertising could be amplified through a double exposure to the stimulus.

Results

The first analysis was to search for possible differences in the answers between the users of both portals. As the identified differences were marginal, the next decision was to analyze all results together without making a distinction between the portals they came from.

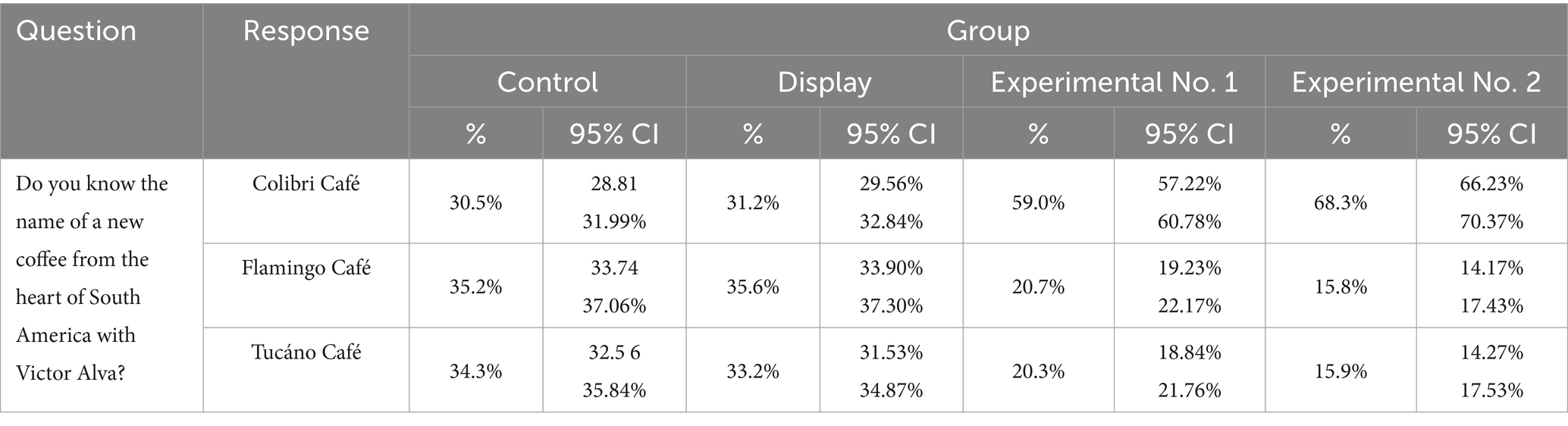

The answers given by the participants are presented in the following tables. Confidence intervals were calculated for each percentage (for the assumed confidence level of 95%) (Table 2).

Table 2. Answers for “Do you know the name of a new coffee from the heart of South America with Victor Alva?” in particular Experimental group – percentage with 95% Confidence Interval.

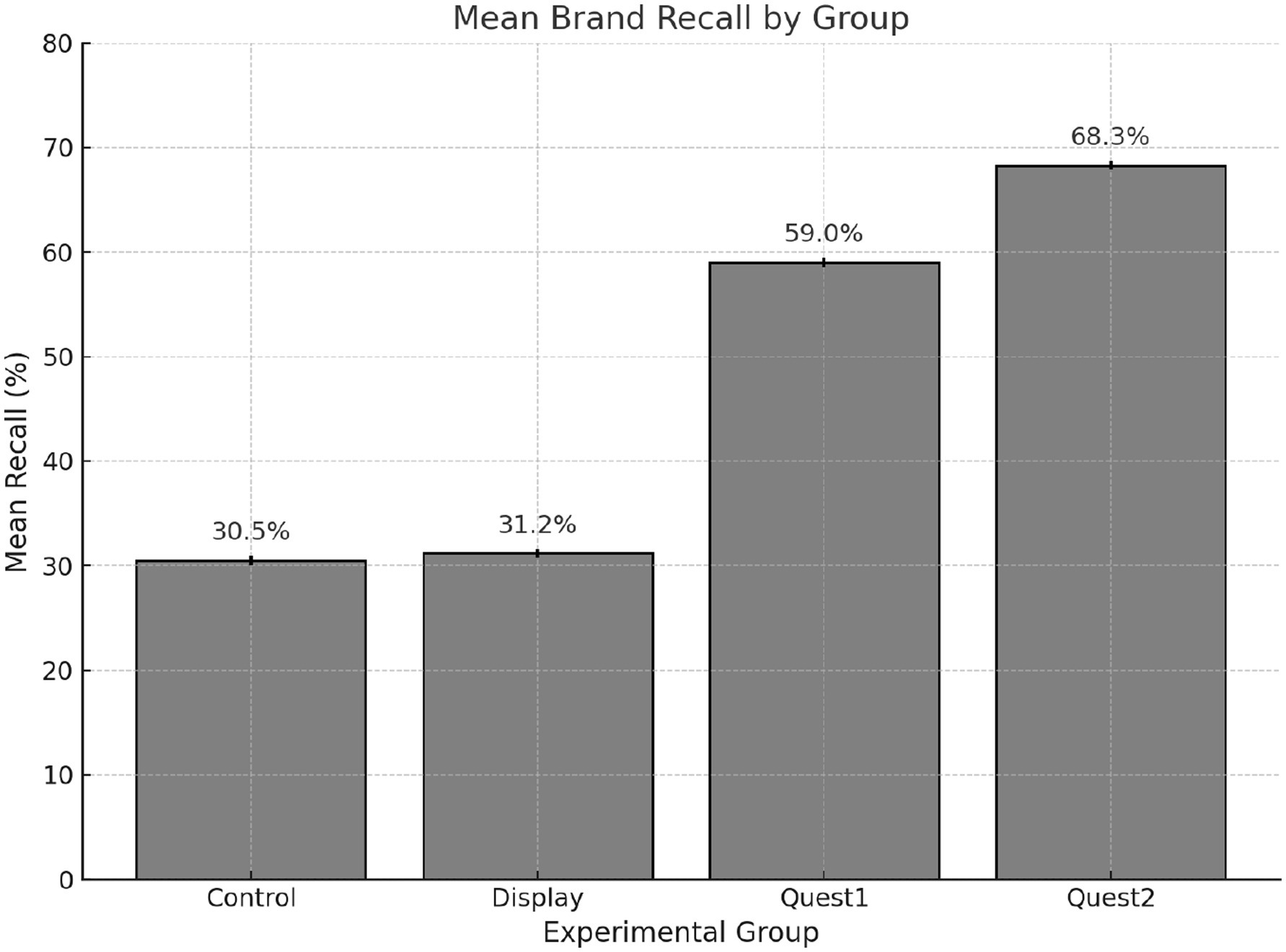

When they were asked about the connection between the Colibri Cafe brand and the person promoting it, i.e., Victor Alva, the participants from the control group and the display ad group responded at a guessing level. Only the groups with the questvertising ad showed a significant increase in the number of correct answers (increase from 59% of correct answers in the group with single exposure to 68.3% in the group with double exposure) (Table 3).

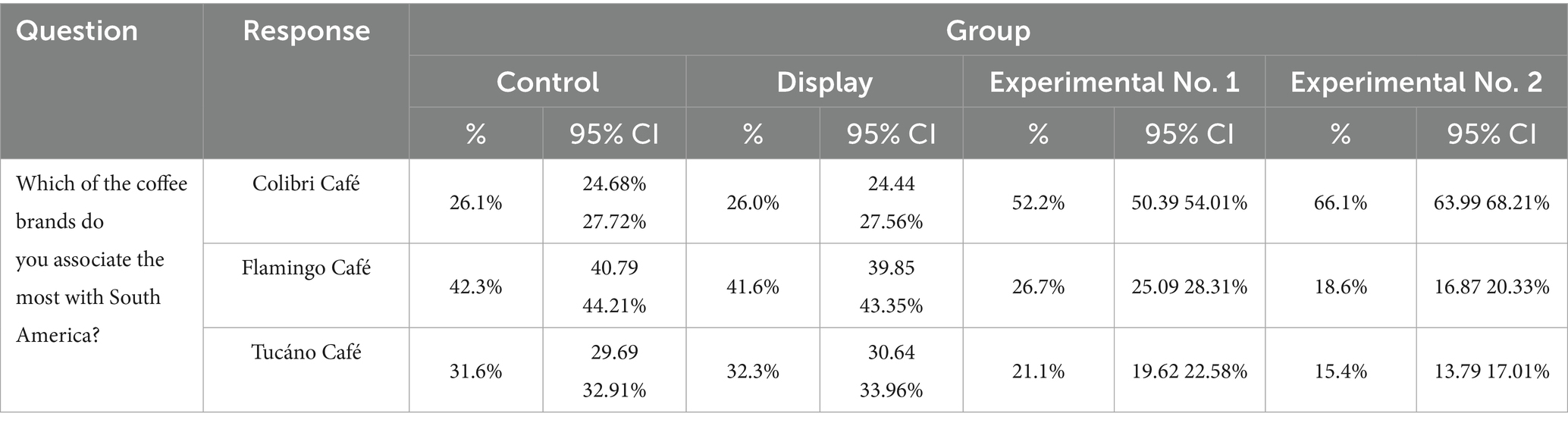

Table 3. Answers for “Which of the coffee brands do you associate the most with South America?” in particular Experimental group–percentage with 95% Confidence Interval.

A similar pattern of answers can be seen in the case of the question pertaining to the associations with South America. Here too, only a small fraction of participants from the control group and the display group provided answers pointing to Colibri Cafe. Results were different in the questvertising ad groups (52.2% with single and 66.1% with double exposure, respectively).

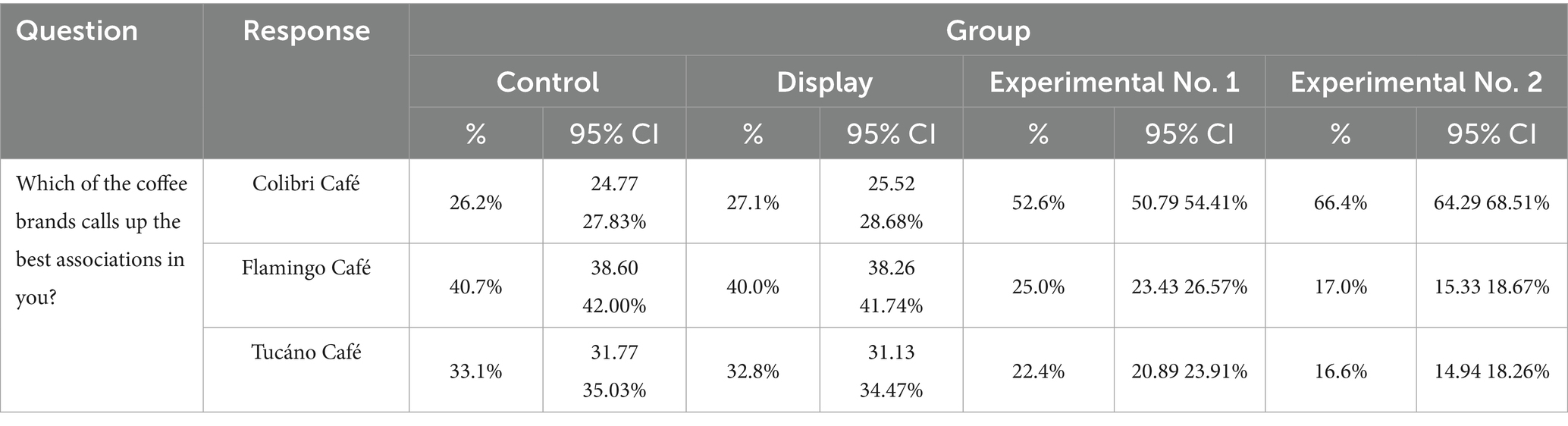

As far as the question regarding the best associations is concerned, again, the results most favoring Colibri Cafe were found in the experimental groups. In the group with single exposure to questvertising, 52.6% of the participants pointed to Colibri Cafe as the brand that called up the best associations. In the group with double exposure, the figure was even higher: 66.4% (Table 4).

Table 4. Answers for “Which of the coffee brands calls up the best associations in you?” in particular Experimental group – percentage with 95% Confidence Interval.

In the first two questions, Colibri Cafe was being compared with two non-existent brands (Flamingo and Tucano), whereas in the following two questions, it was being compared with three brands that are very well recognized on the Polish market (Jacobs, Lavazza and Tchibo) (Table 5).

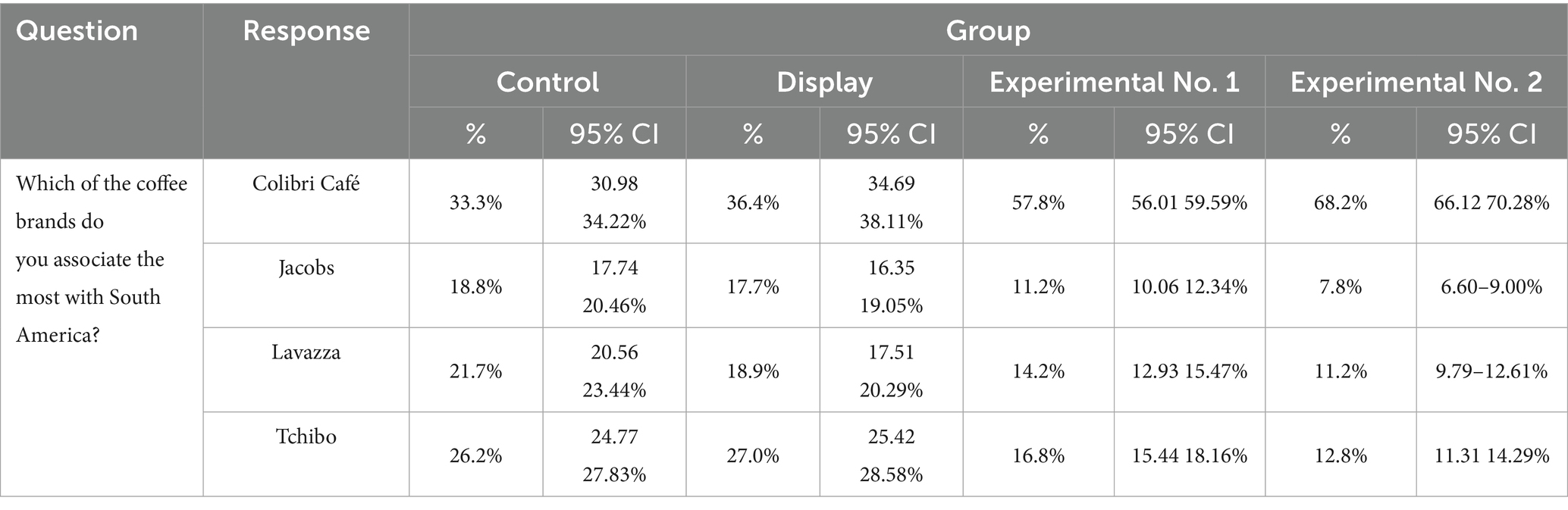

Table 5. Answers for “Which of the coffee brands do you associate the most with South America?” in particular Experimental group – percentage with 95% Confidence Interval.

As far as the question regarding associations with South America is concerned, the Colibri Cafe brand had the highest results in the control and the display ad groups: approximately 1/3 of respondents indicated that this brand made them think of that continent. It appears that the reason for this may be the association with a hummingbird (colibri), especially since the other brand names (Jacobs, Lavazza and Tchibo) fail to call up such geographical associations (and if they did, it would be Germany, in the case of Jacobs, or Italy, in the case of Lavazza). It should be noted, however, that significantly higher results were recorded in the experimental groups, where the percentage was almost two times higher (57.8% for the single exposure group and 68.2% for the double exposure group) (Table 6).

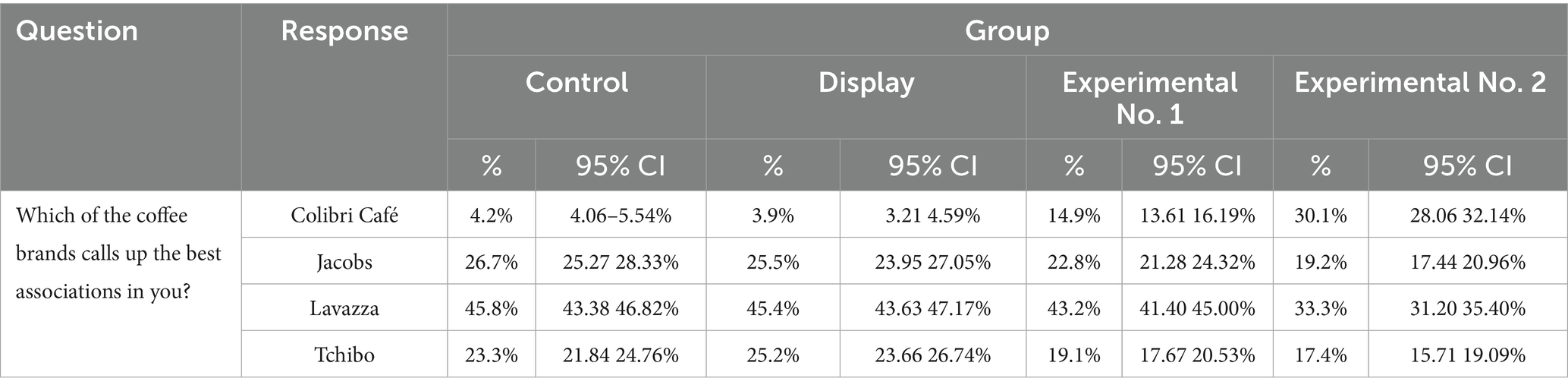

Table 6. Answers for “Which of the coffee brands calls up the best associations in you?” in particular Experimental group–percentage with 95% Confidence Interval.

The final question pertained to one’s positive associations with the brand. In the control group and the display group, the percentage of participants pointing to Colibri Cafe was marginal (4.2 and 3.9%, respectively). It was a completely different picture for the questvertising groups. Even though, in the case of the single exposure group, the number of individuals pointing to Colibri Cafe as the brand that called up the best associations was the lowest among the four coffee brands being compared, it did reach 14.9%. Yet in the case of the group with double exposure to questvertising, the number of participants who pointed to Colibri Cafe as the brand that evoked the best associations increased significantly, to 30.1%. This was the second-best result among all the coffee brands included in the comparison. So, following two exposures to questvertising, the brand that had less customer awareness managed to generate better associations in the research participants than the brands that had been present on the Polish market for decades (Tchibo and Jacobs).

To assess the general effectiveness of questvertising compared to traditional display advertising and no advertising (control), a one-way ANOVA was conducted with recall accuracy (correct brand identification) as the dependent variable and experimental group (Control, Display, Experimental 1, Experimental 2) as the between-subjects factor.

The ANOVA yielded a statistically significant effect of group on recall accuracy, F(3, 11,002) = 437.13, p < 0.001, indicating that at least one of the experimental conditions differed significantly in its effect on recall.

Given the large dataset used in the analyses—which, due to its size, may produce statistically significant results even for small effect magnitudes—Cohen’s d was calculated to assess the strength of the differences between individual groups (see – Figure 3). The results revealed substantial differences between the groups exposed to questvertising and the other two groups (Control and Display). Specifically:

• The comparison between the Experimental 1 and Control groups yielded a large effect size (d = 0.66), indicating significantly improved brand recall after a single exposure to questvertising.

• The Experimental 2 group demonstrated an even larger improvement compared to the Control group (d = 0.89), suggesting cumulative benefits from repeated exposure.

• Notably, the difference between the Display and Control groups was negligible (d = 0.01), suggesting that the display ad format had no meaningful impact on recall relative to no exposure.

• The key difference between the traditional advertising group (Display) and the single-exposure questvertising group (Experimental 1) demonstrated a substantial effect size: d = 0.58.

These results strongly support the hypothesis that embedding cognitive engagement (through answering a question) significantly enhances message retention and brand recall. In contrast, traditional online display advertisements appear largely ineffective in comparison.

Discussion

The studies conducted clearly demonstrated that questvertising is very effective. This applies to all examined parameters: those related to one’s memory and emotions. As it turned out, in the case of all (sic) aspects covered by our studies, questvertising was significantly more effective than the traditional display ad. The correct name of the coffee brand promoted by Victor Alva was selected by over twice as many participants exposed to questvertising as those compared to the display ad. Additionally, almost three times as many respondents associated this brand with South America in the case of questvertising, compared to the traditional display ad. When Colibri Cafe was being compared with non-existent brands, only every fourth participant selected this brand in the case of the traditional advertisement, whereas in the questvertising conditions, over half of the participants did. As far as the comparison with reputable coffee brands that have been present on the Polish market is concerned, only a low percentage of participants exposed to the traditional ad chose Colibri Cafe as the brand that evoked the best associations, whereas the figure rose to between 10 and 20% for those exposed to questvertising.

Additionally, display advertisements proved to be virtually ineffective in the course of the study. All of the answers to the questions regarding coffee brands that the participants were asked were almost identical in the conditions with either exposure to display advertisements and in the control conditions, where the participants were not exposed to any advertisement for Colibri Cafe.

The result patterns are particularly valuable, as they come from the studies designed to test a new, viable product being introduced to the market. What is more, the study was natural, as the participants were completely unaware of their participation in an experiment. The aforementioned high level of effectiveness is particularly impressive when we compare it with the effectiveness parameters of the traditional display advertisement, which are virtually zero.

All of the above clearly suggests that nowadays, when we are bombarded with a staggering number of advertisements on a daily basis, simply increasing the number of ad releases or changing the advertising space (e.g., publishing ads on different web portals) is not a viable solution. It is necessary to skillfully motivate the consumer to actively become familiar with the content of the advertisement message. The studies discussed herein clearly demonstrate that this can be achieved through questvertising.

The results of our study align closely with empirical findings in the literature. They suggest that the future of online advertising must be grounded in the concept of interactivity (e.g., Belanche et al., 2020; Hussain and Lasage, 2013; Kiousis, 2002; Huang et al., 2013). Belanche et al. (2017b) argue that as internet users increasingly develop the ability to ignore or avoid advertisements, the significance of message persuasiveness—traditionally seen as a key determinant of advertising effectiveness—is diminishing. In contrast, factors such as habitual ad-skipping are becoming more influential. This shift implies that only through interactive engagement with the audience can advertising messages achieve effectiveness.

Although some studies indicate that, for certain products and audiences, traditional advertising may outperform interactivity-based approaches (Bezjian-Avery et al., 1998), such cases should be viewed as exceptions rather than the norm. Nonetheless, this does not suggest that further exploration of this compelling issue should be disregarded.

Skipping, or “zapping,” is a challenge that affects nearly all forms of advertising (e.g., Chen et al., 2016; Becker et al., 2022). But does this phenomenon also apply to questvertising—and if so, to what extent? Unfortunately, our current study does not provide sufficient data to answer this question. While the methodology we employed offers several strengths, it lacks the capacity to capture the nuances of ad-skipping behavior within the context of questvertising. Future research should therefore aim to investigate the scale and nature of zapping in this emerging advertising format.

Another important issue related to the effectiveness of questvertising concerns its reward mechanism. In this model, the user is granted immediate access to desired content (e.g., an article or video) after completing a simple quiz. This structure naturally raises the question: would questvertising remain effective in the absence of such an immediate reward? Addressing this question also requires targeted empirical investigation to determine whether the interactive element alone is sufficient to sustain engagement and persuasion.

In conclusion, while we acknowledge that questvertising—as a novel form of interactive advertising—demands further exploration, our findings provide compelling initial evidence of its potential effectiveness. These results underscore the value of continued research into questvertising and its role within the broader landscape of digital advertising strategies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Commitee, SWPS University, Faculty of Psychology in Wrocław. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because since it was a field experiment conducted online.

Author contributions

DD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

DD’s name appears on the HYPERLINK questvertising.com website due to previous academic collaboration between the Social Behavior Research Centre (a research unit affiliated with SWPS University) and Questvertising on research projects evaluating the effectiveness of marketing solutions. This collaboration has been strictly academic. Neither the authors nor their institutions have any financial relationship with Questvertising: specifically, there is no employment, consultancy, honoraria, fees, in‑kind compensation, equity or stock ownership, patents, or paid services associated with Questvertising, and no funding from Questvertising supported the present work. The authors acknowledge that this relationship was not disclosed at the time of submission or during peer review. The omission was inadvertent and the authors apologise for this oversight. This past academic collaboration did not influence the conduct of the present study. Questvertising had no role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, decision to submit, or preparation of the manuscript. The research was motivated solely by scientific aims - namely, to assess the effectiveness of different marketing approaches - and, where applicable in earlier work, by the possibility of accessing a large participant pool. In the authors’ view, this information does not constitute a financial conflict and should not affect the evaluation of the manuscript; it is disclosed here for completeness and transparency. All authors have reviewed and approved this statement.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Weszlo.com

References

Aitchinson, J. (1999). Cutting edge advertising: How to create the world’s best print for brands in 21st century. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Baek, T. H., and Morimoto, M. (2012). Stay away from me: examining the determinants of consumer avoidance of personalized advertising. J. Advert. 41, 59–76. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367410105

Becker, M., Scholdra, T. P., Berkmann, M., and Reinartz, W. J. (2022). The effect of content on zapping in TV advertising. J. Mark. 87, 275–297. doi: 10.1177/00222429221105818

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., and Pérez-Rueda, A. (2017b). User adaptation to interactive advertising formats: the effect of previous exposure. Habit and time urgency on ad skipping behaviors. Telemat. Informat. 34, 961–972. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.04.006

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., and Pérez-Rueda, A. (2017a). Understanding interactive online advertising: congruence and product involvement in highly and lowly arousing, skippable video ads. J. Interact. Mark. 37, 75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2016.06.004

Belanche, D., Flavián, C., and Pérez-Rueda, A. (2020). Consumer empowerment in interactive advertising and EWOM consequences: the PITRE model. J. Mark. Commun. 26, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2019.1610028

Bezjian-Avery, A., Calder, B., and Iacobucci, D. (1998). New media interactive advertising vs. traditional advertising. J. Advert. Res. 38, 23–32. doi: 10.1080/00218499.1998.12466563

Celik, F., Cam, M. S., and Koseoglu, M. A. (2022). Ad avoidance in the digital context: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 47, 2071–2105. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12882

Chen, X., An, L., and Yang, S. (2016). Zapping prediction for online advertisement based on cumulative smile sparse representation. Neurocomputing 175, 667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2015.10.107

Cho, C.-H., and Cheon, H. J. (2004). Why do people avoid advertising on the internet? J. Advert. 33, 89–97. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2004.10639175

Cialdini, R. B., and Schroeder, D. A. (1976). Increasing compliance by legitimizing paltry contributions: when even a penny helps. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 34, 599–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.34.4.599

Dolinski, D. (2016). Techniques of social influence. The psychology of gaining compliance : Routledge.

Dolinski, D., and Grzyb, T. (2019a) Questvertising – nowe podejście do reklamy online. Podsumowanie wyników badań. Raport powstały we współpracy z Adquesto pod patronatem IAB Polska. Available online at: https://www.iab.org.pl/aktualnosci/patronat-iab-polska-raport-questvertising-nowe-podejscie-do-reklamy-online/ (Accessed July 22, 2025).

Dolinski, D., and Grzyb, T.. (2019b). Badanie weryfikujące skuteczność questvertisingu w stosunku do reklamy tradycyjnej. Podsumowanie wyników eksperymentu online. Available online at: https://cdn.questpass.io/reports/Badanie_skutecznosci_reklam_2023.pdf (Accessed July 22, 2025).

Dolinski, D., and Grzyb, T. (2022). 100 Effective techniques of social influence: When and why people comply (1st ed.). Routledge, doi: 10.4324/9781003296638

Dolinski, D., Grzyb, T., Olejnik, J., Prusakowski, S., and Urban, K. (2005). Let’s dialogue about penny: effectiveness of dialogue involvement and legitimizing paltry contribution techniques. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 35, 1150–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02164.x

Enberg, J. (2019). Digital ad spending 2019. eMarketer Report Collection. eMarketer.com. Available online at: https://www.emarketer.com/content/global-digital-ad-spending-2019 (Accessed July 22, 2025).

Filiopoulou, D., Rigou, M., and Faliagka, E. (2019). “Display ads effectiveness: An eye tracking investigation” in Business transformations in the era of digitalization. eds. K. Mezghani and W. Aloulou, Hershey, Pennsylvania: IGI Global. 205–230.

Gao, Q., Rau, P. L.-P., and Salvendy, G. (2010). Measuring perceived interactivity of mobile advertisements. Behav. Inf. Technol. 29, 35–44. doi: 10.1080/01449290802666770

Genschow, O., and Oomen, D. (2025). “Imitation and social influence” in Research handbook of social influence. ed. R. Prislin (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 227–241.

Grzyb, T., and Dolinski, D. (2022). The field study in social psychology. How to conduct research outside of a laboratory setting? London and New York: Routledge.

Grzyb, T., Dolinski, D., and Kulesza, W. (2021). Dialogue and labeling. Are these helpful in finding volunteers? J. Soc. Psychol. 161, 63–71. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2020.1758017

Huang, J., Su, S., Zhou, L., and Liu, X. (2013). Attitude toward the viral ad: expanding traditional advertising models to interactive advertising. J. Interact. Mark. 27, 36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2012.06.001

Hussain, D., and Lasage, H. (2013). Online video advertisement avoidance: can interactivity help? J. Appl. Business Res. 30, 43–49. doi: 10.19030/jabr.v30i1.8279

Jain, P., Karamchandani, M., and Jain, A. (2016). Effectiveness of digital advertising. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. 3, 490–495. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.36629.99048

Jensen, J. F. (1998). “Interactivity” tracking a new concept in media and communication studies. Nordicom Rev. 19, 185–204.

Kiousis, S. (2002). Interactivity: a concept explication. New Media and Society 4, 355–383. doi: 10.1177/146144480200400303

Kireyev, P., Pauwels, K., and Gupta, S. (2016). Do display ads influence search? Attribution and dynamics in online advertising. Int. J. Res. Mark. 33, 475–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2015.09.007

Kulesza, W., Dolinski, D., Wicher, P., and Huisman, A. (2016). The conversational chameleon: an investigation into the link between dialogue and verbal mimicry. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 35, 515–528. doi: 10.1177/0261927X15601460

Kumar, A., Bezawada, R., Rishika, R., Janakiraman, R., and Kannan, P. (2016). From social to sale: the effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior. J. Mark. 80, 7–25. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0249

Kumar, V., and Gupta, S. (2016). Conceptualizing the evolution and future advertising. J. Advert. 45, 302–317. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2016.1199335

Leeflang, P. S., Verhoef, P. C., Dahlström, P., and Freundt, T. (2014). Challenges and solutions for marketing in adigital era. Eur. Manag. J. 32, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2013.12.001

Ma, J., and Du, B. (2018). Digital advertising and company value: implications of reallocating advertising expenditures. J. Advert. Res. 58, 326–337. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2018-002

Mohammed, A. B., and Alkubise, M. (2012). How do online advertisements affects consumer purchasing intention: empirical evidence from a developing country. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 4, 208–218.

Niu, X., Wang, X., and Liu, Z. (2021). When i feel invaded, I will avoid it: the effect of advertising invasiveness on consumers’ avoidance of social media advertising. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 58:102320. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102320

Santoso, I., Wright, M., Trinh, G., and Avis, M. (2020). Is digital advertising effective under conditions of low attention? J. Mark. Manag. 36, 1707–1730. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2020.1801801

Schneiderman, B., and Plaisant, C. (1987). Designing the user interface: Strategies for effective human-computer interaction. Boston: perason Education, Inc.

Steuer, J. S. (1992). Defining virtual reality: dimensions determining telepresence. J. Commun. 42, 73–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00812.x

Strenta, A., and DeJong, W. (1981). The effect of prosocial label on helping behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 44, 124–147. doi: 10.2307/3033711

Keywords: questvertising, interactive advertisement, attention, brand recall, field experiment ad study

Citation: Dolinski D and Grzyb T (2025) Questvertising as a new format of interactive advertising. Front. Commun. 10:1641657. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1641657

Edited by:

Naser Valaei, Liverpool John Moores University, United KingdomReviewed by:

João Lucas Hana Frade, University of São Paulo, BrazilEndi Rekarti, Indonesia Open University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Dolinski and Grzyb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tomasz Grzyb, dGdyenliQHN3cHMuZWR1LnBs

Dariusz Dolinski

Dariusz Dolinski Tomasz Grzyb

Tomasz Grzyb