- Department of Drama, Faculty of Creative Arts, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

This study investigates how religious soundscapes mediate historical trauma in Snow in Midsummer (2023), directed by Malaysian Chinese filmmaker Chong Keat Aun. Focusing on Ah Eng's auditory journey to locate the graves of her father and brother lost in the 1969 May 13 Incident, the film interweaves personal grief, collective memory, and spectral presence. The research applies a sound-oriented close textual analysis, in which auditory events are systematically annotated and archived with timecodes, categorized into religious, spectral, and environmental sounds, and then examined through semiotic and contextual analysis. Interdisciplinary theories from trauma studies, sound anthropology, and religious aesthetics, together with Malay-language historical materials, inform the interpretations. The analysis reveals that sonic elements such as the adhan, Buddhist bells, and Taoist rituals transcend multicultural reflection by generating a cross-cultural acoustic space that resists political amnesia. In doing so, the film stages a form of sonic memory work where mourning converges with resistance and ritual with historical critique, offering an ethics of listening rooted in spiritual hybridity and emotional resonance that allows the voices of the dead to reverberate within Malaysia's postcolonial soundscape.

1 Introduction

In contemporary humanities and social sciences, increasing scholarly attention has been directed toward the intersections of religion and sensory experience. Among these, sound has emerged as a central medium through which spirituality, communal consciousness, and the transmission of historical memory are evoked, particularly within religious rituals. In the context of collective ceremonies, spiritual practices, and the mediation of historical trauma, sound not only triggers emotional responses but also embeds itself within both individual and collective memory (Schafer, 1993a; Beck, 2006). Religious experience, therefore, is not solely rooted in doctrinal belief or textual interpretation, but is deeply situated within the realm of sensory perception. As one of the most immediate and affective modes of sensory engagement, sound constitutes an indispensable element in the construction of the sacred domain (Beck, 2006). Schafer (1993b) asserts that the soundscape of any society profoundly reflects its cultural structures and values; religious soundscapes, in particular, embody transcendent orders. Thus, the religious voice serves not only as an accompaniment to faith and ritual but also, through its materiality and symbolism, evokes resonance within specific historical landscapes and embodied experiences, constituting an “affective soundscape”—a sonic environment that triggers individual and collective emotional responses through sound.

Relying solely on Western soundscape theories to interpret the religious sonic experiences of Southeast Asian Chinese communities presents theoretical limitations. Malaysian ethnomusicologist Tan Sooi Beng, in her seminal work, emphasizes the necessity of a decolonized theoretical lens to understand Malaysian musical traditions, moving beyond singular Western knowledge production paradigms. Tan's collaborative work with Patricia Matusky, The Music of Malaysia: Classical, Folk and Syncretic Traditions, provides a critical context-specific theoretical foundation for analyzing Malaysia's diverse religious soundscapes (Matusky and Beng, 2017). This study thoroughly examines Malaysi's syncretic music, Chinese musical traditions, and popular music forms, highlighting the interwoven characteristics of multi-ethnic and multi-religious sonic cultures.

In the Malaysian cultural context, religious sounds exhibit a distinctive syncretic quality. This syncretism is not only evident in musical forms but also in the transmission of religious practices and cultural memory. For instance, the percussive sounds of gongs and drums in Chinese temple festivals, the vocal styles of the Malay traditional theater bangsawan, and the multi-ethnic participation in religious celebrations collectively form a “syncretic soundscape” that transcends singular religious boundaries. Tan's research on bangsawan reveals how this performance form integrates Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Western musical elements, serving as a sonic representation of Malaysia's multicultural identity (Tan, 1993). This context-specific theoretical perspective underscores that Southeast Asian religious sounds cannot be adequately understood through the Western binary framework of sacred vs. secular; rather, they require an appreciation of their “syncretic spirituality.” Furthermore, Malaysian scholarship on the ritual functions of traditional music offers significant theoretical support for this study. The concept of “bunyi alam” (natural sounds) in traditional Malay music theory emphasizes the intrinsic connection between sound, cosmic order, and the spiritual realm. This perspective posits that specific sounds possess the capacity to invoke spirits, heal the soul, and connect with ancestors, engaging in a compelling dialogue with Western soundscape theories that prioritize ecological and social analyses. Cinema, as a highly sensory and synesthetic art form, has redefined the significance of sound within the broader “sonic turn” in cultural theory, becoming a powerful conduit for the articulation of affect, sociopolitical meaning, and identity. In film, sound often exceeds its technical or narrative function, acquiring ritualistic, mediatic, and mnemonic dimensions. In the cultural context of Sinophone communities in Southeast Asia, religious sound is deeply entwined with local knowledge systems and embodied practices shaped by multilingual, multiethnic, and multireligious interactions. The clang of gongs and drums, ritual chanting, funeral laments, operatic performances, and temple soundscapes are not only markers of cultural identity, but also perceptual traces of ethnic trauma and fractured memory. These layered sonic forms, saturated with religious significance, serve as mediums of historical re-enactment across time and space. Within this framework, Hirsch's (2012) theory of “postmemory” offers a crucial lens through which to understand how sound operates as a carrier of trauma and inherited memory. Hirsch contends that those who did not directly experience a traumatic past may nonetheless inherit its affective imprint through images, narratives, and sonic experiences. This becomes particularly salient in Snow in Midsummer, where sound functions not merely as a vehicle for recalling history, but as a means of acoustically binding individual and collective trauma. As Hirsch suggests, sound becomes a medium of postmemory—an auditory path through which audiences “hear trauma.” This view is further reinforced by Laub's (1995) work on “traumatic listening.” According to Laub, trauma often escapes verbal articulation but may be re-evoked through sound and other sensory experiences, forming what he describes as a “heard but unseen voice”—a sonic embodiment of trauma, haunting, and the unspeakable. These disembodied yet emotionally charged sounds become the “echoes of trauma,” giving form to historical suffering in sensory terms and providing a space for both characters and audiences to confront the unresolved past.

Snow in Midsummer, directed by Malaysian filmmaker Chong Keat Aun, exemplifies this intersection of religious sound, memory, and cinematic representation. Set against the historical backdrop of the May 13 Incident of 1969, the film recounts the story of a young Chinese girl, Ah Eng, and her mother, who witness a Chinese opera performance of The Injustice to Dou E at a temple festival when racial violence suddenly erupts. This traumatic event—marked by familial loss and unspeakable grief—leaves an enduring psychic scar. Nearly five decades later, Ah Eng returns to the cemetery in search of her missing father and brother, only to find the opera stage dismantled and the sacred sonic space of her past silenced by contemporary realities. The film's narrative intricately weaves personal memory, ethnic suffering, and national history into a poetic meditation on time, space, sound, and spiritual resilience. Garnering acclaim at major festivals including the Golden Horse Awards, the Venice Film Festival, and the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Snow in Midsummer has attracted attention not only for its historical and political themes but also for its experimental and affectively rich sound design. Crucially, Chong does not treat sound as a mere backdrop for narrative progression. Rather, he imbues it with ritualistic, mediatic, and mnemonic significance. The film's religious soundscape—composed of traditional opera performances, hallucinated voices, ambient natural sounds, and funeral dirges—forms a multi-layered auditory environment through which the audience enters a spiritual space of trauma remembrance and emotional restoration. These mysterious and evocative sonic elements not only summon the ghosts of historical violence but also construct what may be termed an “audible cultural trauma.”

This study uses Snow in Midsummer as a primary case study to investigate the role of religious sound as a critical medium for historical re-enactment, spiritual mediation, and cultural identity reconstruction in Malaysian Chinese cinema. Former Malaysian Prime Minister Abdul Razak Hussein candidly described the May 13 riots as a national tragedy (Council, 1969), an event also known as the “Kuala Lumpur riots” (Reid, 1969). In fact, the divide-and-rule policy implemented during British colonial rule was a key factor in sowing the seeds of racial tensions in Malaysia (Azizan, 2024). Additionally, the socioeconomic discontent among Malays appears to have been a fundamental cause of this crisis, prompting the government at the time to introduce the “New Economic Policy” in an effort to address the situation (DeBernardi, 2004). However, even today, the “May 13 Incident” remains a highly sensitive topic within Malaysia's social and political discourse. Furthermore, due to the long-term suppression and obfuscation of related historical records, the full truth about the “May 13 Incident” has yet to be fully clarified (Show, 2021). By engaging with theories of religious sound, postmemory, and soundscape aesthetics, the paper examines three major auditory realms in the film—Taoist funerary rituals, spectral voices, and environmental soundscapes. It argues that sound, in Snow in Midsummer, serves not merely as a technical component but as a resonant force that constructs a spiritually charged cinematic space, invoking suppressed cultural memory and negotiating historical trauma. Furthermore, the study explores how religious auditory experiences enable both characters and audiences to confront affective silences, contributing to the broader discourse on the aesthetics and politics of religious listening within contemporary Malaysian Chinese cinema. Through close textual analysis and interdisciplinary theoretical engagement, the paper also sheds light on how sonic aesthetics mediate cultural trauma, religious pluralism, and political remembrance in Sinophone Southeast Asian cinema.

This study adopts a sound-oriented analytical approach, using the film Snow in Midsummer (2023) as the primary text. Through systematic auditory sampling and the integration of interdisciplinary theories, the study explores the mediating function of religious soundscapes in historical trauma, cultural memory, and spiritual perception.

The research methodology consists of the following steps:

1. Systematic annotation of auditory events and sound archiving

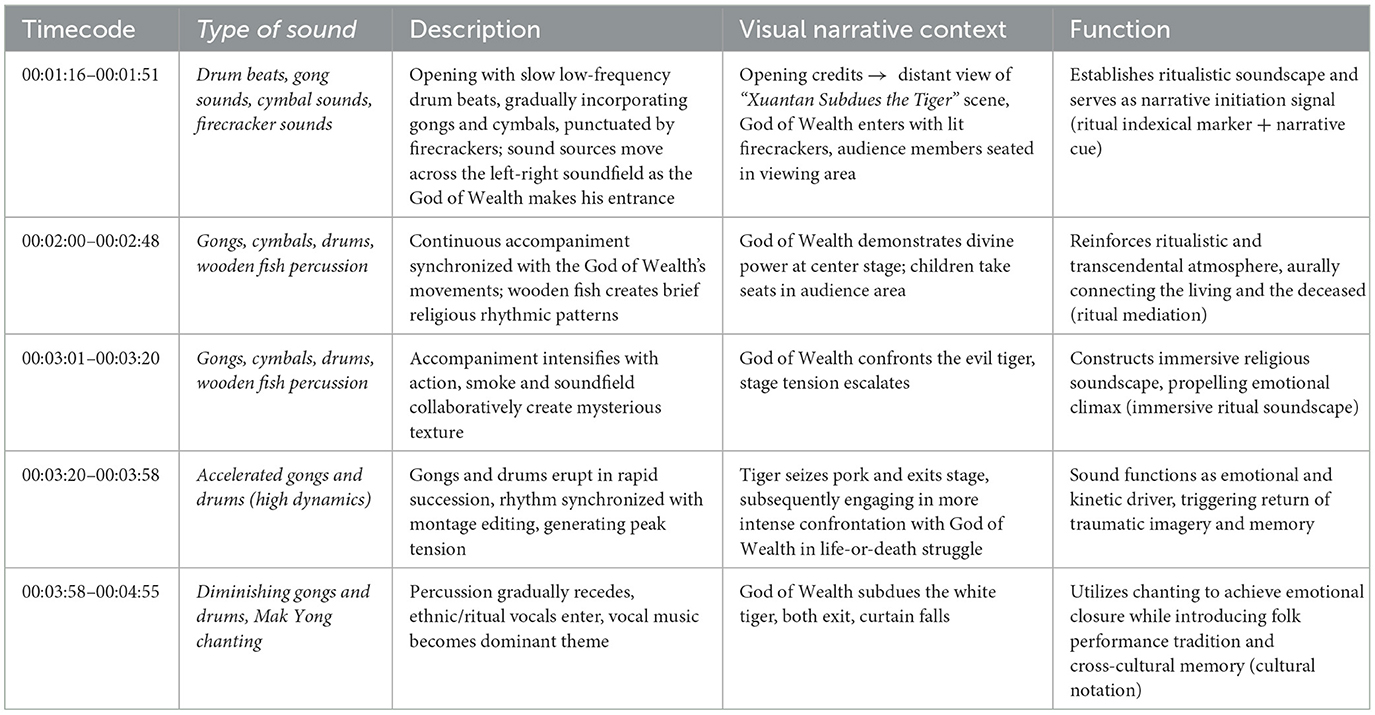

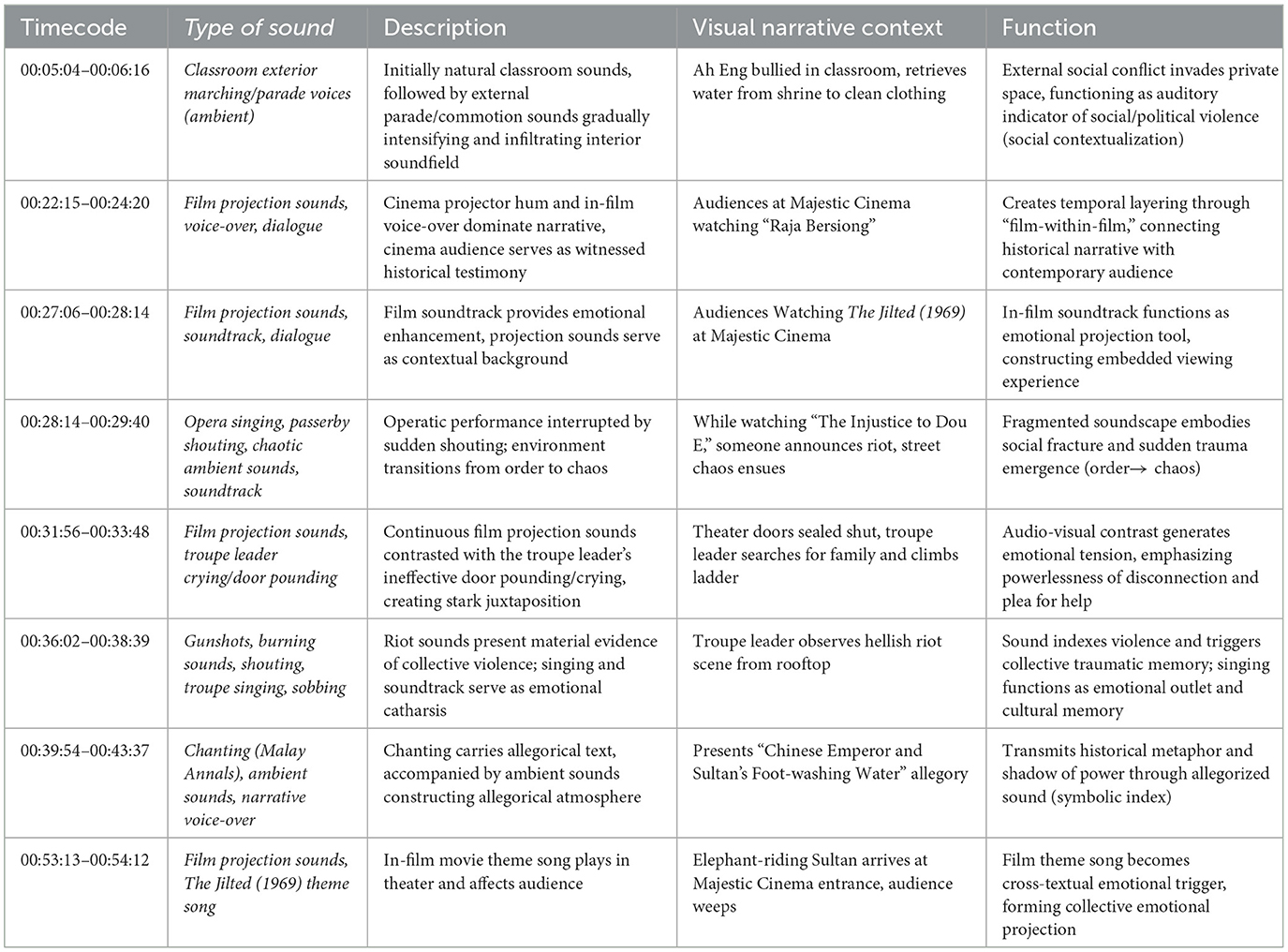

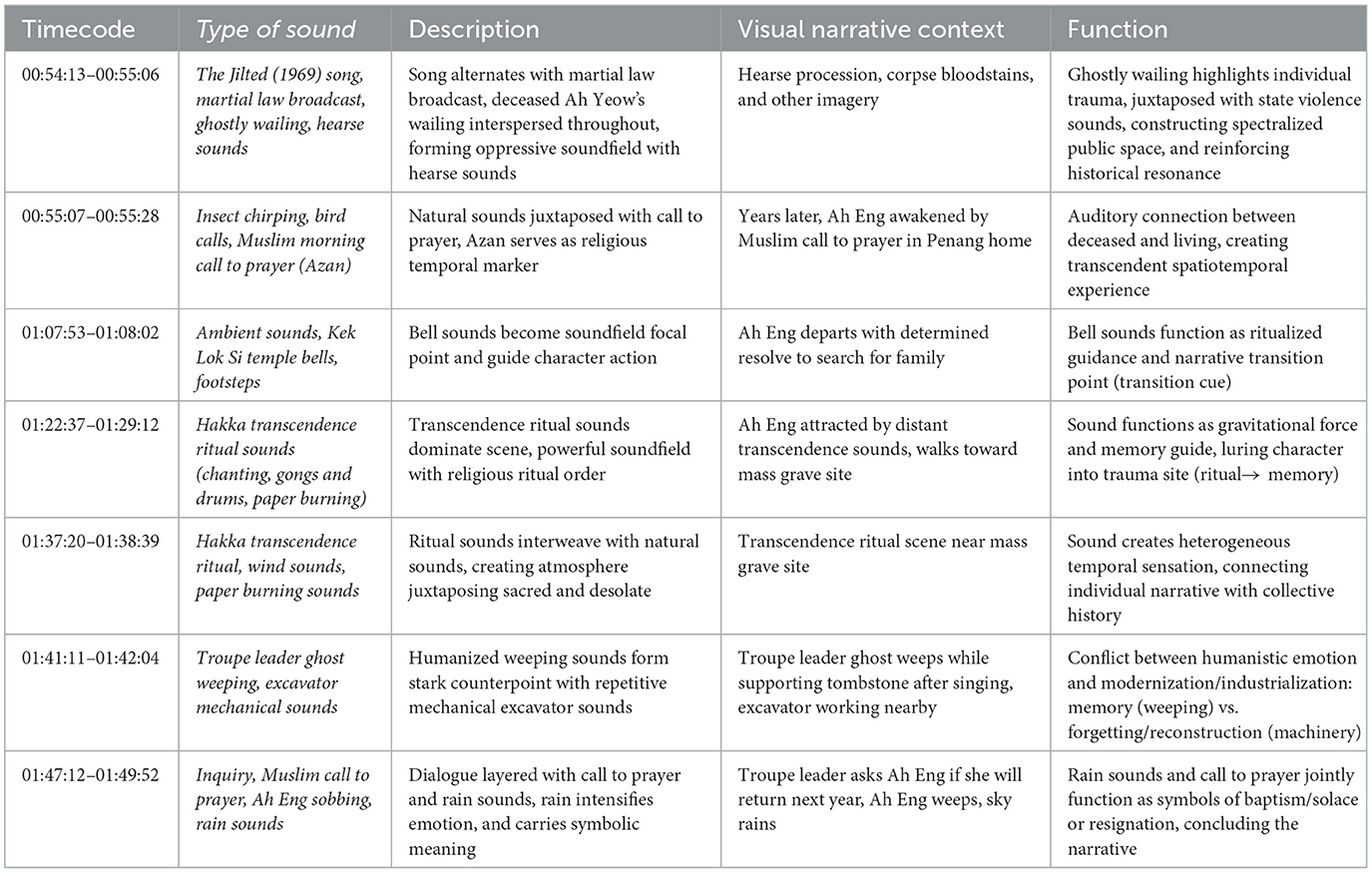

Through multiple viewings of the film, auditory events are meticulously categorized and recorded in timecode format (see Tables 1–3). The sound categories include religious and ritual sounds such as bells, chanting, and Taoist rituals; ghost and hallucinatory sounds such as spirit summons and broadcast noise; and natural and environmental sounds such as rain, night insects, and wind. In each of the three main analytical sections, a representative scene is selected, and in-depth sampling analysis is conducted, using timecodes to avoid arbitrariness and subjectivity, providing verifiable evidence to support the argument.

2. Semiotic and contextual analysis of auditory events

Each auditory segment is contextualized within its specific narrative sequence. The analysis includes the spatial quality, temporal duration, tonal texture, and interaction with visual imagery. The focus is on examining the role of sound in constructing religious spaces, triggering historical memories, and evoking emotional resonance.

3. Theoretical and contextual interpretations

This paper engages in interdisciplinary dialogue, drawing from research on religious sound, post-memory theory, and the politics of sound. It also incorporates selected Malay language historical materials and local studies on the 13 May incident and traditional religious practices in Malaysia to deepen the cultural and historical accuracy of the sound analysis.

Through these methods, the study not only achieves a close reading of the film's text on an auditory level, but also addresses the complexity of sound as a medium of history and a political vehicle from a methodological perspective.

2 Taboo sound: the religious soundscape and spiritual authority in Xuantan Subdues the Tiger (玄坛打虎)

Within the Malaysian Chinese context, religious and ritual practices often manifest as syncretic blends of Buddhism, Daoism, and folk beliefs. Snow in Midsummer integrates elements of exorcism rites, spirit invitation, paper-burning, and auditory hallucinations, all of which exemplify the distinctive religious sound culture of Malaysian Chinese communities. Director Chong Keat Aun employs a narrative strategy that intertwines heightened realism with the uncanny, crafting a cinematic space where memory is continuously reawakened through both visual and auditory modalities. In Snow in Midsummer, theater serves as a dominant sonic thread throughout the film. Yet behind the theatricality lies a profound aesthetic and philosophical exploration. At the beginning of the film, we are drawn into the first scene by the gradually intensifying dramatic sounds of gongs and firecrackers. The stage of the Poh Cheung Choon Opera troupe prominently displays the title of Guan Hanqing's Snow in Midsummer. Snow in Midsummer, derived from an ancient Chinese folktale, depicts the tragic plight of the lower classes, who are at the mercy of those in power, with no outlet for their suffering. The play condemns the dark reality of corrupt officials who trample on human lives. However, Chong Keat Aun argues that The Injustice to Dou E, a play that expresses condemnation of corruption and politics through opera, transcends time, because for the victims who perished in the “snowstorm” of May 13, 1969, in Malaysia, it remains an unresolved grievance to this day (Swallow Wings Films, 2023). From this perspective, the director may have intended, through the intricate plot of The Injustice to Dou E, to reveal certain forms of oppression and resistance that existed in Malaysian society at the time, as well as a deep reflection on the political system.

Poh Cheung Choon Opera, founded by the renowned Malaysian Cantonese opera clown Leung Sing Poh, is Kuala Lumpur's oldest troupe. Before debuting in a new venue, Cantonese opera troupes traditionally conduct a clearing ritual—po tai (破台)—to ward off malevolent spirits and ensure a safe performance. Thus, in the film, following the firecracker display, the troupe proceeds with Xuantan Subdues the Tiger's blessing ritual.

Xuantan Subdues the Tiger is conventionally performed by two actors—one as Xuantan (the martial deity Zhao Gongming), the other as the tiger. Because of numerous taboos surrounding its performance, Chong invited veteran Cantonese opera master Choi Yim Heung to guide the ritual. During Xuantan's entrance, a lit string of firecrackers dramatizes his authority. The explosive sonic impact of the firecrackers is believed to dispel evil energies, purifying the space for the performance. Simultaneously, the thunderous crackle heightens the dramatic tension, signaling the initiation of a sacred ritual and transporting spectators from quotidian reality into a mythic domain. Importantly, this ritual performance is not meant for the uninitiated—viewing it by ordinary people is considered inauspicious, so accompanists typically perform backstage. Meyer (2006) defines “sensational forms” as sensory-symbolic media—images, sound, rhythm, scent, touch—that communicate with the divine, generating presence rather than merely conveying information. Through sound, imagery, rhythm, and performance, religious belief becomes perceptible and emotionally experienced. These sensory forms also mobilize collective emotion and identity: through drums, music, and rhythm, participants are drawn into a sacred time-space, cultivating presence and belonging (Meyer, 2006, 2012). In Xuantan Subdues the Tiger, the firecrackers, gongs, and singing collectively construct a non-worldly perceptual framework—an act of sonic ritualization that embeds spiritual authority. The taboos and sacredness materialize through this sound-based structure: its normative use establishes who may listen and defines the sonic parameters of invoking deities, dispelling impurity, and creating spiritual boundaries. This constitutes an auditory power structure that challenges and summons viewers ethically.

Chong Keat Aun has remarked that dense smoke filled the stage during filming, dispersing only after the tiger character was subdued—a coincidental visual echo of the deity's arrival (Chang, 2023). Moreover, time and auditory rhythm are meticulously coordinated to produce a cross-modal religious experience. Within the highly ritualized po tai, distinct percussion instruments play complementary roles: gongs emphasize climaxes, drums maintain rhythmic momentum reminiscent of battle or divine procession, cymbals heighten tension, and wooden clappers, fish drums, or auxiliary percussion synchronize with dialogue. Together, they form a percussive ensemble that signals religious gravitas. Simultaneously, the interplay of sound and stage imagery—the deity's procession, actors' movements—fosters a dual auditory-visual sensoriality, generating a psychological sense of sacred presence. Drawing on Durkheim's concept of “collective effervescence” (Durkheim, 1915), the film replicates ritual immersion, so even cinematic audiences may vicariously experience sacred presence via screen mediation. Through sonic narration, viewers are not mere spectators, but participants “led” into a concretized ceremonial space. The legend of Xuantan Subdues the Tiger holds that ordinary people are forbidden from watching the performance. Moreover, throughout the entire process of the performance, from the makeup to the final act, all participants must maintain absolute silence. Anyone who violates this taboo will bring bad luck and negatively affect future performances. The sounds of the performance, often in the form of suona, gongs, drums, vocal chants, and the shouting of the actors, demarcate the boundary between the divine and the human, thus creating a typical ritual soundscape. However, we can see that the man and child eating durian in the audience are completely at ease as they observe this forbidden performance. First, the middle-aged man is, in fact, a “concrete manifestation of divine power.” In fact, the official Instagram account of Snow in Midsummer mentions that the man eating durian in front of the opera stage, the Sultan riding an elephant, and the taxi driver who takes Ah Eng to the cemetery are all incarnations of the deity Datuk Gong (Bao, 2023). Therefore, since Datuk Gong is a divine figure, the taboo surrounding the deity's worship performance has no effect on the man in the audience, which we can understand. However, the director has collected local rumors that a child who watched the forbidden play on the day of the May 13th incident disappeared that night (Chang, 2023). This rumor seems to corroborate the account of Ahmad Mustapha Hassan, the former CEO of Bernama News Agency, who witnessed the killing of a Chinese teenager during the outbreak of the 1969 May 13th racial riots (Wong, 2007). An important feature of the performance is the “tiao jia” (跳架)—a composite of stage routines in Cantonese opera, with the basic form known as “tiao da jia (跳大架).” After the opening blessing, the actor playing Xuantan, dressed in the black “four-color coat” of the martial deity, performs an exorcizing tiao da jia, traversing the stage to expel evil. A large piece of pork hangs center-stage to bait the tiger. The actor follows choreographed shapes—steps, jumps, symbolic moves—culminating in “zha jia” (扎架) at center stage. When the tiger appears and devours the pork, Xuantan tames it with a divine whip, binds it using iron, and then retreats. After victory, he wipes his black makeup with “spirit paper,” symbolizing ritual completion and the lifting of taboos, signaling audible closure. It can be argued that the opera Xuantan Subdues the Tiger is rich in symbolic significance. It reveals the complex emotions of fear and hatred that the opera troupe harbors toward the white tiger, which represents disaster and misfortune. On the one hand, the troupe offers pork as a sacrifice to the tiger to appease it and prevent harm to others. On the other hand, they rely on the divine power of Lord Xuantan to subdue the tiger, eventually transforming it into a tamed mount. Senior members of the troupe vividly recount that any pork that has been “consumed” by the tiger and falls to the ground would not even be sniffed by dogs. This anecdote gestures toward a deeper metaphor: the opening ritual performance seems intricately connected to the May 13 Incident and the fraught relations between Chinese and Malay communities. The opera becomes a site of irony and allegory. Rather than simply a reproduction of folk custom or religious aesthetics, Xuantan Subdues the Tiger becomes a “ritual theater” imbued with political metaphor, constructed by the director. Through religious gestures and the demonic imagery of deities, it refers to the ethnic violence of May 13, symbolizing the Chinese community's need to perform self-sacrifice and self-soothing in the face of historical suppression and structural inequality. The disjunction between its symbolic content and historical context renders the ritual at once solemn and ironic, sacred and unsettling. Additionally, Schafer (1993a) introduced the concepts of “hi-fi” and “lo-fi” soundscapes in his discussion of the transition from rural to urban auditory environments. A “high-fidelity” soundscape refers to one in which natural sounds are clearly heard and relatively undisturbed by human-made noise, offering a clear spatial and acoustic distance that allows the source of sound to be easily identified. In contrast, a “low-fidelity” soundscape is marked by ambient noise, mechanical interference, and indistinct background sounds, making it difficult to discern specific sonic sources. In the segment depicting Xuantan Subdues the Tiger, the gongs and vocal chants, with their high penetrability and spatial resolution, constitute a typical high-fidelity soundscape. Due to their clarity, purity, and lack of extraneous noise, such sounds create a pronounced sense of distance and layering within the auditory field, and in the ritual context, they perform a function akin to sonic purification, namely, expelling impurities, cleansing the space, and establishing a sacred order (Wong, 2001; Feld, 2012; LaBelle, 2019). However, the film does not present this hi-fi soundscape in a static manner. Rather, it repeatedly situates it within low-fidelity soundscapes—such as ambient human chatter, mechanical noise, or reverberations that blur the boundaries of sound sources. This transition from hi-fi to lo-fi and back to hi-fi creates a dynamic sonic tension, which not only propels the narrative rhythm but also thematically resonates with the film's exploration of order and chaos, the sacred and the secular. In other words, hi-fi soundscapes in the film do not exist in isolation; their ritualistic and symbolic significance is amplified through repeated interaction with lo-fi soundscapes, thereby enhancing the expressive capacity of sound in both spatial and cultural terms.

Furthermore, as Feld (2012) argues, sound is not merely a physical phenomenon of the natural world but is socially and culturally constructed. From the perspective of Feld's acoustic epistemology, the ritualistic performance of Xuantan Subdues the Tiger communicates an ineffable, deeply layered religious and spiritual experience that defies verbal expression. These sounds embody cultural perceptions of the supernatural and serve as conduits for ancestral and divine knowledge. They summon a soundscape resonating with deities, historical trauma, and taboos—one to be heard rather than seen. In this way, Chong Keat Aun's approach may be intended to highlight the concept of “restricted listening rights” within culture, demonstrating how, in specific historical contexts, sound functions as a suppressed political symbol and reveals the auditory experiences that are overlooked or marginalized in postcolonial societies. It is worth noting that ethnomusicologists Matusky and Beng (2017) have defined the concept of “syncretic music,” which primarily refers to a musical form emerging in multiethnic and multicultural contexts through the fusion of indigenous folk and classical music traditions with external musical elements. In Malaysia, this concept encompasses both urban and rural musical practices, as well as dance, theater, and vocal performances. Such music achieves a highly inclusive and flexible sonic culture by combining local Malaysian folk and classical elements—such as ghazal, dondang sayang, zapin, inang, and joget—with melodies, rhythms, instruments, and performance techniques from Arabic, Persian, Indian, Chinese, and Western traditions. Furthermore, the defining characteristic of syncretic music lies in its open assimilative mechanism: foreign elements can be incorporated into melody, timbre, scale, lyrical themes, and performance techniques, while still maintaining intrinsic connections to the local context (Matusky and Beng, 2017).

In this particular scene, the director creates a Malaysian-style syncretic musical soundscape by collaging sounds that blend the vocal chants of the Malay traditional theater Mak Yong, Cantonese opera singing, and the percussive textures of Gamelan into the same auditory track. According to the theory of syncretic music, this cross-cultural sonic fusion is not a simple juxtaposition but involves structural interaction and cultural recontextualization: in their original contexts, Mak Yong and Cantonese opera serve the ritualistic and entertainment needs of distinct ethnic groups, yet in the film, they are positioned within the same narrative framework, producing a cross-religious and cross-ethnic syncretic spirituality. By interweaving the performance traditions of different communities within a single spatiotemporal framework, the director creates a syncretic soundscape that allows the audience to perceptually experience the fluidity and interpenetration of cultural identities.

Moreover, one might ask whether this phenomenon represents the localization of Cantonese opera in Malaysia. Traditionally, localization refers to adaptations of Cantonese opera in terms of performance language, themes, and character settings to suit local Chinese audiences—for example, by incorporating Malay-language lines, drawing on local stories, or performing during festival events. However, the introduction of Mak Yong in the film does not appear to fall within this “gradual adaptation” framework; rather, it exemplifies a cross-cultural reconfiguration in a postcolonial context. To deepen our understanding of this phenomenon, I invoke the concept of “postcolonial performative collage.” This concept emerges from key frameworks in postcolonial theory, particularly Homi Bhabha's notion of “hybridity,” which emphasizes the rupture and recombination of cultural identity in colonial and postcolonial contexts, rather than essentialist unity (Bhabha, 1994). It also draws on Judith Butler's idea of performativity, which views cultural identity as a dynamic process constructed through repeated performance (Butler, 2011). Furthermore, collage as an artistic form—originating in modernism, for instance in the works of Pablo Picasso—functions in art history and performance studies not merely as the juxtaposition of heterogeneous elements, but as a cultural strategy capable of revealing ruptures, recombinations, and power relations (Krauss, 1986; Sturken and Cartwright, 2016). In postcolonial criticism, this concept is extended to signify the deliberate juxtaposition of fragmented elements, challenging dominant narratives and exposing power dynamics (Ikas and Wagner, 2008). Within postcolonial theory, the meaning of this concept goes beyond a general questioning of cultural boundaries: it highlights the fluidity and instability of cultural identity in multiethnic societies. By deliberately collaging heterogeneous elements—such as the sounds and embodied practices of different theatrical traditions—it exposes the traumas and marginalized experiences inherited from colonial histories and the active re-creation of identity by subjects in multilingual environments. This form of collage is not random; it constitutes an ideologically driven intervention intended to subvert colonial binaries and foster a “third space,” in which cultural hybridity becomes a strategy of resistance and innovation (Bhabha, 1994).

In Snow in Midsummer, the opening ritual opera Xuantan Subdues the Tiger interweaves gongs, Cantonese opera singing, spirit medium utterances, and audience prayers to construct a religious soundscape that transcends visual representation. As a ritual performance, it not only revives folk beliefs through traditional opera but also evokes suppressed historical memories and cultural identities through its “forbidden sounds.” These sonic expressions—once marginalized and labeled as superstition or illegitimate by the modern nation-state—are reactivated through religious ritual and cinematic imagery. In doing so, they form a mediatic sensorium imbued with “spirit mediumship.” This sound treatment enhances the ritual's mysticism, producing a liminal auditory state that guides the audience across the thresholds of the mundane and the supernatural, the living and the spectral. As LaBelle (2019) and Gautier (2015) have argued, sound is not merely sensory experience but a political force that intervenes in space, memory, and subjectivity. In Chong's film, these “forbidden sounds” demonstrate the heterogeneous power of religious acoustics—autonomous from state institutions and dominant ideologies, yet organically generated and empowered through vernacular belief and bodily perception.

Through this practice of the “politics of sound,” it can be inferred that the film suggests how sound may resist disciplinary systems, evoke spiritual agency within repressed religious discourses, and offer an alternative testimony to historical trauma. As Hirschkind (2006) observes, religious sound produces an “ethical soundscape” that provides a space of moral perception beyond the dominant public sphere. In Xuantan Subdues the Tiger, the sound field—formed by the rhythm of gongs, the vocal stylings of Cantonese opera, and the voices of worshippers—awakens not only deities but also the Chinese Malaysian community's deeper awareness of identity, faith, and memory. Thus, religious soundscape becomes a sensory strategy to resist hegemonic historical narratives and a cultural practice that reconstructs ethnic subjectivity within spiritual space.

3 The sound of trauma: echoes of historical memory and spiritual listening

The May 13 Incident of 1969, a violent racial conflict that erupted in Kuala Lumpur, remains a haunting and often unspoken memory among Malaysian Chinese communities. Official narratives frame it primarily as an ethnic clash between Malays and Chinese, but it stands as one of the most devastating racial conflicts in Malaysian history, exerting a lasting impact on the country's political structure, social fabric, and interethnic relations.

Historically, tensions between Malay and Chinese communities had intensified during the 1960s. While Malays were predominantly rural and economically disadvantaged, Chinese communities were more urbanized, economically active, and better educated—creating a perception of marginalization among segments of the Malay population. This discontent, coupled with dissatisfaction toward the ruling Alliance Party's ethnic policies, catalyzed the rise of opposition parties with stronger ethnic or ideological agendas, such as the Democratic Action Party (DAP), Parti Rakyat (PR), Parti Buruh, Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), and Gerakan. The general election on May 10, 1969, marked a turning point, with the opposition achieving significant victories in several states—posing an unprecedented challenge to the ruling coalition and plunging the nation into political instability.

Intriguingly, the film Snow in Midsummer begins with a reference to the Sulalatus Salatin, a 17th-century Malay chronicle written by Tun Sri Lanang on May 13, 1612. This date is not a mere coincidence but a historically loaded metaphor. The film also alludes to a legend in which the Sultan of Melaka cures the Chinese emperor's leprosy by forcing him to drink his foot-washing water. This unsettling myth hints at power imbalances and racial tensions, foreshadowing the eruption of the May 13 Incident. Furthermore, the film briefly inserts a scene from Raja Bersiong, a mythological film based on the Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa and co-written and financed by Malaysia's first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman. Originally intended as a cultural project to legitimize the Malay monarchy, the story of a bloodthirsty king with fangs who is eventually overthrown by his people becomes a powerful allegory of tyranny and political violence. Director Chong Keat Aun repurposes this myth as a “substitutive violence narrative,” using mythological imagery to evoke collective memory of ethnic conflict in a context where direct visual representation of the May 13 Incident remains censored or taboo.

In the first act of the film, we see Ah Eng being bullied in her primary school classroom in Kuala Lumpur—three days after the election. Her Malay classmates smear blue ink on her uniform and hang her bag from a height. The blue ink subtly symbolizes the Malaysian identity card, which was blue in color, alluding to the rejection of Chinese Malaysians' belonging by Malay peers. As this scene unfolds, the background hums with the indistinct sounds of protestors marching outside—a sonic portrayal of the nation's tense political atmosphere. The film later shows the opera troupe leader returning to the Majestic Cinema during the riots, calling out for her mother in vain, knocking on doors without response. Climbing to the rooftop via the side stairs, she witnesses a scene of carnage resembling hell. With desperation, she sings:

Hell tolls the funeral bell, blood and doom my cruel fate foretell. The innocent butchered on the execution ground— Oh Heaven above, hear my lamenting sound.

(地狱一片丧钟响,恨薄命祸起血案。斩杀在刑场实太 枉。青天在上,哀哀叩恳,叩恳。)

Here, the audience inside Majestic Cinema exists in a sealed sonic space. The troupe leader's cries for “ah Ma” and the others go unanswered—her voice becomes a “voice in vain.” This acoustic failure illustrates a rupture in sound transmission, symbolizing the collapse and silencing of maternal and traditional realms in the face of political violence. According to Das (2006), the linguistic system of everyday life breaks down in the aftermath of state violence, forcing survivors to articulate pain in marginal ways. The troupe leader's cries are unheard, embodying a traumatic call rendered mute and unacknowledged. Ascending the rooftop, she is overwhelmed by the city's apocalyptic violence and channels her anguish through lines from The Injustice to Dou E. Director Chong avoids directly portraying the riot's violence, likely due to censorship constraints, and instead uses off-screen sound—distant gunshots, flames, wails, and screams—to construct a suffocating auditory atmosphere. Only at the end does the camera reveal a distant, hazy vision of hell on earth.

This scene is more than a personal outpouring; it exemplifies how certain voices are structurally “unheard” during social upheaval. As Ahmed (2013) argues, emotions are not purely internal but circulate within systems of power; the refusal to respond to emotion constitutes a repressive social mechanism. In this context, the closed doors of the theater signify more than physical obstruction—they embody a systemic “unhearing.” The troupe leader's knocks and cries call for shelter, kinship, and justice, but these sounds receive no answer. The persistent image of the “door that cannot be opened” symbolizes not only physical inaccessibility but also the structural silencing of emotional and political expression—especially of women and diaspora Chinese communities. These voices are excluded from the circuits of recognition and empathy.

This soundscape reaches its peak during The Injustice to Dou E, where the troupe leader assumes a symbolic voice for all silenced subjects. Her act of singing transforms a moment of voicelessness into one of resistance, establishing a tense nexus of religion, culture, and emotion. The scene also illustrates the existence of what may be termed “acoustic repression”: a boundary condition that governs which voices are allowed to be heard in a given sociopolitical context. Under the dual pressure of ethnic and gendered hierarchies, the troupe leader's body and voice are excluded from the domain of audibility. As Ahmed (2013) notes, some bodies and subjects are constructed as “sticky”—bound to pain and unable to generate resonance in public discourse. The troupe leader and Ah Eng become embodiments of the many women marginalized under Malaysia's patriarchal and Bumiputera structures. Lastly, the sonic isolation crafted in this scene does not constitute mere silence. Instead, through off-screen sound, the film enacts what may be called a “traumatic listening” experience. The troupe leader hears the city's violence from a distance—unable to intervene or respond. This involuntary, passive form of listening materializes what Sara Ahmed describes as “institutionally denied voices.” It also aligns with Michel-Rolph Trouillot's concept of “formulas of erasure” (2015), which posits that historical silences are not due to an absence of testimony but result from deliberate exclusion and obliteration by power structures.

It is worth noting that, as later narrative developments suggest, the opera troupe leader was in fact killed by rioters at the theater entrance. Her subsequent performance of The Injustice to Dou E emerges not from the realm of the living, but as a ghostly return—a spectral voice from beyond death. This reveals that the film's notion of “spiritual space” is not merely an extension of physical space, but rather a transcendent manifestation made audible through “repressed voices” and “voices of injustice.” The moment she sings atop the theater roof, her dramatic lamentation mirrors her status as a victim of political violence. In Chinese classical drama, Dou E is a symbol of the wronged soul and is culturally encoded as a voice of female grievance. By employing a play-within-a-play structure, Chong Keat Aun enables the spectral voice to resonate through operatic performance, enacting a form of “traumatic voicing through song.”

From the perspective of Michel-Rolph Trouillot's notion of “historical silences,” the ghostly singing of the opera troupe leader enters into a profound dialogue with the state's systematic suppression of speech—what may be described as the enforced injunction that “the victims of the riots must not speak” (Trouillot, 2015). The troupe leader's ghost does not articulate itself through ordinary colloquial language, but rather through ritualized opera passages, a performative language whose very formalism enacts a “ghostly return.” This process may be understood as a form of aphasic resistance: here, “aphasia,” originally a medical term denoting a speech disorder, is metaphorically reconfigured as a cultural and political strategy of expression. In a post-traumatic society where direct speech is fraught with danger, individuals turn instead to non-linear, indirect symbolic forms. Such a turn should not be mistaken for passive silence; rather, it constitutes an active form of “strategic silence.” Further, drawing on Jacques Derrida's concept of hauntology, this “ghostly reappearance” underscores how past traumas continue to “haunt” the present through ritualized language, challenging the hegemony of official narratives (Derrida, 2012). More specifically, in the scene of the troupe leader, aphasic resistance manifests as a multimodal political act: by speaking through traditional operatic verses rather than modern speech, the ghost finds a pathway of circumvented expression. This is not merely the substitution of one cultural form for another, but an invocation of the non-verbal registers of religion and opera soundscapes to subvert mechanisms of repression. As Veena Das suggests that pain is often expressed through bodily and ritual practices, which serve as powerful testimonies to the inexpressible aspects of trauma (Das, 2006). Similarly, Trinh T. Minh-ha's theorization of “voice-absence” illuminates how marginalized subjects resist through indirect narration and fragmented voicing (Minh-ha, 1989).

In this scene, the rhythm, tonal inflections, and repetitions of the operatic verses emulate the cyclical emergence of the ghost. Their interstitiality—manifested in silences, ambiguities, and polyvalent meanings—invites the audience to insert their own interpretations, thereby generating a resonance of collective resistance. For instance, when the verses invoke canonical repertoire such as The Injustice to Dou E, they allegorize contemporary injustice by means of historical analogy, transforming personal trauma into social critique. Yet this resistance is marked by a duality: on the one hand, it establishes a “safe distance” that helps circumvent censorship; on the other hand, it risks reinforcing the internalization of silence—a paradox that requires critical reflection. Ultimately, as the troupe leader gazes down from the theater loft at the inferno below, where crowds scatter in panic, the director attenuates the infernal visual iconography and instead amplifies the off-screen environmental sounds—screams, explosions, the chaotic rhythm of fleeing footsteps—to produce an aural reconstruction of the May 13 violence. As J. Martin Daughtry suggests that the ambient sounds of war and violence carry greater emotional and mnemonic impact than visual images, serving as powerful mediators of inexpressible trauma (Daughtry, 2015). The ghostly voice of the troupe leader embodies precisely this faint yet insistent resonance that emerges from repression, aligning with David Der-wei Wang's theorization of “spectral narratology” to transform aphasic resistance into a persistent mode of collective memory (Wang, 2004). Through this analysis, aphasic resistance not only links the ghostly return of an individual with broader structures of political suppression but also demonstrates the subversive potential of sound in narrating trauma.

In Snow in Midsummer, the tension between state ideology and religious sound is further articulated through the notion of auditory governance—the deployment of sound as a tool of state control. At the Majestic Cinema, the theme song from the Taiwanese melodrama The Jilted (1969) functions as a “pre-traumatic sonic memory.” Laden with sorrow and personal sentiment, this nostalgic tune starkly contrasts the looming eruption of political violence, foreshadowing how private emotional sound will soon be eclipsed by state violence. This juxtaposition critiques the state's control over public auditory space. Through contrapuntal layering of “state voices” and “individual voices,” Chong reconstructs Malaysia's collective auditory memory of the 1969 May 13 Incident, exposing how sound becomes a medium for ideological control. Within this framework, the film foregrounds the central question of how individuals experience rupture, trauma, and silence under oppressive soundscapes.

4 Ghostly voices: the call of the dead and the manifestation of spirits

Across many cultural and religious traditions, the boundary between the dead and the living is often permeable. Sound functions as a key medium that crosses this threshold, carrying with it the voices of the dead and their spectral reappearances. In Snow in Midsummer, director Chong Keat Aun constructs ghostly voices as one of the film's core elements, using carefully designed soundscapes to explore the intricate relationship between the living and the dead. In scenes involving religious rituals and spiritual space, sound becomes more than a tool for emotional communication; it acts as a carrier of historical trauma and cultural memory. The voices of the dead—manifested through chanting, gong strikes, and Taoist rituals—evoke remembrance of lost loved ones and reveal collective trauma and spiritual disquiet beneath the silence. The emergence of ghostly voices signals unresolved histories and spectral presences within the world of the living, charged with an invisible tension that reflects the entanglements of cultural identity, sociopolitical histories, and personal memory. Through analysis of these soundscapes, we arrive at a deeper thematic inquiry: how sound forges a nexus between history and spirituality, leading us beyond life and death, beyond time, into a space of unspeakable trauma and remembrance.

Notably, the film's climactic representation of the May 13 Incident offers a chillingly “spiritual” and aurally disturbing scene. Filmed from a low angle beneath a corpse transport vehicle, the camera reveals no bodies—only the slow drip of blood—while the auditory layer combines three contrasting elements: the song from The Jilted, the prime minister's emergency broadcast, and a boy's anguished cries. The broadcast declares: “It is regrettable that many Muslims cannot attend prayers at the mosque, but they may pray at home. Let us pray to Allah together, that our beloved nation may soon return to peace.” This is immediately followed by the ghostly moan of the deceased Ah Yeow: “Papa, where are you? It hurts… Mama, little sister, where are you? It hurts…” Althusser (2001) insightfully observed that the state constructs auditory spaces through media, such as radio, inducing citizens to perceive themselves as being cared for and thus to voluntarily accept the legitimacy of state power. In this scene, however, the radio's ideological function is exposed. Its tone is deeply patriarchal and religious, invoking “Allah” and “prayer” to reframe the state of emergency and suppression as a moral necessity. The message makes no mention of the perpetrators, ethnic conflict, or the dead. Instead, it constructs an illusory auditory image of national harmony, masking the visceral fear and bloodshed experienced by the oppressed. This is a calculated ideological maneuver that conceals reality beneath a soft-spoken rhetoric of care.

In Snow in Midsummer, the “return of the dead” is not simply a narrative device but a ritualized sonic act that invokes history, the departed, and traumatic experience. Voices such as that of the opera troupe leader and the deceased Ah Yeow transcend time and the boundary between life and death, revealing the power of spiritual space, and the reconstruction of memory. Visually, the film only shows blood dripping from the transport vehicle, maintaining a stark visual restraint. However, its auditory design is strikingly forceful. Ah Yeow's cries are not ordinary lamentations but imbued with a distinctly ghostly quality. His rising pitch from “it hurts” to prolonged moans generates a sense of helplessness and auditory violence. His voice, erupting from death, addresses his father—and gestures toward an “invisible trauma.”

Chong's treatment of Ah Yeow's ghostly voice reflects Chion's (1999) notion of the acousmêtre—a voice that precedes its image, possessing spectral authority and dominating the audience's sensory perception. Though we never visually witness the massacre, we imagine its horror through the surreal sound of Ah Yeow's voice, which constructs an invisible yet suffocatingly sorrowful auditory space. Even more striking is the contrast between Ah Yeow's cries and the radio broadcast. While the state projects a soundscape of “peace, prayer, and calm,” Ah Yeow counters with one of “pain, disconnection, and death.” This sonic juxtaposition produces a rupture in the ideological auditory field. On the surface, the broadcast delivers comfort, but beneath it lies the wail of the dead. These two layers never interact, yet the director deliberately overlays them in a single scene, producing a profound dissonance.

Through this auditory montage, Chong creates a deep tension: ideological discourse and ghostly memory speak simultaneously yet cannot address each other. As Ahmed (2013) argues, when personal pain cannot be acknowledged in public discourse, emotional suppression itself becomes a structure of auditory ideology. As the narrative unfolds, the setting shifts to Ah Eng's home in Penang, decades after the 1969 events. She awakens to the sound of the Muslim morning prayer (adhan), followed by a visual cut to the statue of the Goddess of Mercy at Penang's Kek Lok Si Temple. This marks the beginning of the film's second act, centered on Ah Eng's adult life. Notably, when Ah Eng later decides to leave Penang for Kuala Lumpur in search of the graves of her father and son, who perished during the May 13 Incident, the film reprises the image of the Kek Lok Si statue. This time, the ambient temple bell tolls accompany her silent departure, luggage in tow.

The interplay of sound and image in this sequence can be read as a symbolic rendering of Ah Eng's inner transformation and spiritual journey. Her awakening to the sound of the adhan, immediately followed by the image of a Buddhist icon, carries profound religious and cultural connotations. The Muslim call to prayer marks the start of a new day—an aural signal of awakening that also operates as a spiritual summons. It gently stirs Ah Eng from the silence of trauma into a more lucid path of life. Simultaneously, it invites the audience into the film's sonic narrative and Ah Eng's inner world, fostering an affective resonance with her complex emotional state while revealing the multi-religious fabric of her sociocultural environment. The presence of the adhan within Ah Eng's domestic space also subtly reflects her embeddedness in broader social and historical contexts. The sound performs a dual function: as part of daily life, it marks routine continuity; as an intrusive presence, it evokes a sense of cultural dissonance. For Ah Eng, whose Peranakan identity places her between Chinese traditions and Malay cultural influence, this auditory encounter accentuates the tensions of cultural hybridity. The adhan, while signifying spiritual order and communal belonging, simultaneously underscores her marginal status in relation to Malay-Muslim society. Her identity is not fixed but fluid, shaped by ongoing negotiations with social and religious forces. In this sense, the adhan may be experienced by Ah Eng not only as a religious invocation but as a marker of cultural estrangement. Despite living within a multiethnic and multireligious society, her Nyonya heritage renders her relatively peripheral within the dominant Muslim cultural paradigm. Thus, the morning prayer does not merely awaken—it also reminds her of her in-betweenness, her precarious positioning within overlapping systems of faith, ethnicity, and gender. Strikingly, the juxtaposition of the adhan and the temple bell resonates as an acoustic mapping of her emotional trajectory—from grief and numbness toward spiritual redemption. As she departs with her suitcase, the tolling bell deepens the emotional charge of the scene. No longer a mere ritualistic sound, the bell becomes a metaphor for inner resolve. It signifies a psychological turning point as she begins to seek closure and belonging after the compounded trauma of 1969 and an unhappy marriage. Echoing with symbolic weight, the bell functions as both solace and summons, connecting her to the memory of the dead and urging her toward self-recovery.

In the film's second act, Ah Eng visits the unmarked burial ground at the Sungai Buloh Leprosy Settlement, nearly 50 years after the May 13 Incident. Her journey is more than a private act of mourning—it becomes a poignant critique of the systemic erasure of national trauma and communal memory. The visual austerity of the overgrown cemetery contrasts sharply with her solitary figure, evoking the marginalized status of the deceased within official historiography and the broader exclusion of Chinese Malaysian narratives from the national imaginary. Through meticulous audiovisual composition, the film transforms Ah Eng's search for graves into a listening act—an ethical and spiritual engagement with the silenced past. The ritual space comes alive with the sounds of a Taoist appeasement ceremony: chanting, cymbals, the burning of joss paper, and women's wailing. In Chinese Malaysian cultural belief, violent deaths are classified as “improper,” requiring specific Taoist rituals to pacify the spirits and prevent spiritual unrest. When Ah Eng stumbles upon a Hakka Taoist ritual being conducted at the mass grave, the film underscores the convergence of personal trauma and collective religious practice. Here, ritual sound mediates the threshold between the living and the dead, linking memory and spiritual agency.

This encounter is followed by a spectral reunion with the ghost of a Chinese opera troupe leader. Their exchange unfolds in an in-between spiritual realm—neither fully real nor wholly imagined—a liminal space shaped by ritual sound, natural acoustics, and mourning. The ghostly figure elicits Ah Eng's long-suppressed grief, as she recounts her inability to locate her family's tombstones and her ritual offerings to anonymous graves. The opera leader's question, “Will you come again next year?” triggers her emotional collapse. As Ahmed (2013) argues, emotions are shaped by histories and cultural contexts; they circulate in public space, disclosing structures of trauma and power. Ah Eng's sobs become both a personal lament and a sonic protest against the state's amnesia. At the emotional climax, the sudden emergence of the Muslim call to prayer interrupts the scene with solemn gravity. This moment of sonic intrusion introduces a transcultural religious register, extending the ritual space into an acoustic commons. Hirschkind (2006) posits that religious auditory ethics can generate alternative public spheres, allowing otherwise repressed memories and affects to find resonance. In this light, the adhan not only offers a prayer for the dead but also provides spiritual cleansing for Ah Eng and the viewer. Contrasted with her crying, it marks a turning point from despair toward transcendence, embodying the possibility of religious coexistence in Malaysia's pluralistic society. The addition of ambient rain and natural sound further amplifies the emotional and ritual atmosphere. In fact, this particular sonic combination exemplifies the core principle of bunyi alam. Within this conceptual framework, the sound of rain is not treated merely as environmental background noise but as a “meaningful sound” that embodies the intrinsic connection between cosmic order and the spiritual realm. Unlike Western soundscape theories, which often emphasize ecological contexts or socio-cultural analysis, bunyi alam underscores an ontological dimension of sound—namely, that sound itself constitutes a manifestation of sacred power. Thus, when the sound of rainfall intermingles with the call to prayer, they together generate a multilayered spiritual soundscape: the rain functions as a divine manifestation, resonating with Islamic teachings that interpret natural phenomena as signs of God's mercy and purification, while the prayer serves as a medium of “human–divine dialogue,” harmonizing with natural sounds within the cosmology of bunyi alam. As Caruth (2016) notes, trauma often reappears through delayed or repetitive returns, with sound functioning as a conduit for affective reverberation. The sound of rain thus becomes more than a backdrop—it signifies purification and cosmic mourning, reinforcing the relational nexus between human, nature, and spirit within the spiritual soundscape.

It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the high-fidelity ritual soundscape created by the gongs and vocal performance in the Xuantan Subdues the Tiger segment, the excavation machine's roar from the cemetery side during the ritual of purification introduces a typical low-fidelity soundscape. The persistent, broad-spectrum industrial noise significantly elevates the environmental “noise floor,” compressing the dynamic range and spatial depth of the soundscape. This obscures the boundaries of the sound sources of the scripture and ritual instruments, which are masked by background reverberation and the mechanical hum (Schafer, 1993a). This type of acoustic masking is not merely an auditory disturbance; rather, it represents a structural intrusion into the ritual's spatial-temporal and meaning-making order: on the one hand, the ritual's original intention of “sonic purification”—to cleanse the space, settle the spirits, and consolidate communal memory through clear, directed sounds—is counterbalanced by the lo-fi noise. On the other hand, the mechanical noise shifts the auditory focus from the center of the ritual (the altar/reciter) to the material apparatus of the “logic of development,” redrawing the scene's “acoustic territory” (LaBelle, 2019). This shift from hi-fi to lo-fi not only diminishes the sacred atmosphere of the ritual but may also be interpreted as a disturbance of historical memory, symbolically covering over the collective trauma narrative. In this sense, the presence of noise provides the audience with a perceptual path: it makes the sounds of historical events “difficult to hear clearly” on an acoustic level, thereby prompting reflections on how society handles sensitive historical narratives (Wong, 2001; Assmann, 2011; Feld, 2012).

More crucially, the interweaving of Buddhist bells, Taoist chants, and the Islamic adhan constructs an interreligious acoustic commons. In this multisensory field, religious traditions do not compete but coalesce as overlapping responses to trauma. As Hirschkind (2006) affirms, religious soundscapes can cultivate alternative ethical imaginaries. In the film's long takes, ritual sounds—chanting, cymbals, joss paper burning, mourning cries—do not merely serve as background but symbolically reconfigure death as a process of summoning, identification, and remembrance. The integration of natural sound—such as the fluttering of ashes or the whispering wind—furthers the film's construction of a temporary sacred space. These sounds become ritual acts, inviting the audience to listen to the dead and participate in a multisensory ethic of mourning. Visually, the film alternates between stasis and movement; sonically, it blurs the boundaries of time and space. In doing so, it renders death, memory, and spirit permeable. In conclusion, the “ghostly sounds” in Snow in Midsummer do not merely signify spectral presences; they reveal the entanglements of history, culture, and spirituality through a carefully curated acoustic space. The voices of the dead cross temporal thresholds, voicing silenced histories and unresolved grief. Ritual and natural sounds together construct a healing soundscape—one that enables the audience to perceive trauma, reckon with history, and encounter spiritual consolation. These sounds are not echoes of a vanished past but enduring carrier of cultural memory in the present.

Through his intricate sound design, Chong Keat Aun crafts a cross-religious sonic landscape charged with affective intensity, transforming traumatic listening into a dual practice of political critique and spiritual ethics. The alternating layers of the adhan and Buddhist bell resonate not only with Ah Eng's plural religious context but also with her emotional arc and identity tensions. Sound becomes a crucial medium for articulating and healing trauma, reconstructing cultural belonging, and inviting the audience into a sonic space of mourning, reflection, and potential redemption.

5 Conclusion

Snow in Midsummer by Chong Keat Aun constructs a multi-layered auditory landscape in which religious, cultural, and spectral sounds are not merely aesthetic choices but epistemological interventions into the politics of memory and trauma in postcolonial Malaysia. This study has examined how the film mobilizes sonic elements—including the adhan, Buddhist temple bells, Taoist appeasement rituals, natural environmental sounds, and spectral voices—to articulate unspoken grief, intergenerational trauma, and suppressed histories, particularly surrounding the May 13 Incident.

Through a nuanced sound design, the film foregrounds the concept of traumatic listening—a process in which the audience and protagonist are drawn into an ethical relation with the past through auditory memory and ritual soundscapes. These sounds do not simply accompany the narrative; they structure the affective temporality of trauma and healing, marking transitions between memories and forgetting, silence and articulation, death and the sacred. Ah Eng's embodied experience of sound—beginning with her awakening to the adhan and culminating in her encounter with ritual sounds at the mass grave—maps a spiritual journey from silence and displacement to mourning and partial reconciliation. Her hybrid Peranakan identity complicates this journey, rendering each sound an index of cultural tension, religious coexistence, and personal loss. The juxtaposition of multiple religious soundscapes does not signify harmony or universalism, but rather dramatizes the layered entanglement of Malaysia's pluralistic society—one in which faith traditions coexist amidst political exclusion and unresolved historical wounds.

The film's deployment of acoustic elements as memory work echoes scholarly insights into the role of sound in the constitution of religious and affective communities (Hirschkind, 2006; Meyer, 2015). By incorporating the aural textures of ritual—chanting, bells, weeping, ambient rain, industrial noise—Snow in Midsummer generates what may be termed a sonic counter-archive, wherein the silenced dead are audibly re-inscribed into the cultural and historical consciousness. In this acoustic commons, listening becomes both a spiritual practice and a political gesture of witnessing. Moreover, the film critiques the violent incursion of modern capitalist development into sacred space through its sharp sonic contrast between ritual and mechanical noise, highlighting the continued marginalization and erasure of subaltern memory in the name of national progress. The sound of the excavator, intruding upon mourning rituals, becomes a metaphor for systemic forgetting—a second act of violence against the victims of state-sanctioned historical amnesia. Ultimately, the film proposes an alternative ethics of listening: one that resists closure and acknowledges the spectral nature of historical trauma. By attending to the voices of the dead through ritual, ambient, and spectral sound, Snow in Midsummer activates a collective auditory memory that transcends visual representation. In doing so, it repositions cinema as not merely a visual medium but a site of sensory and spiritual reckoning.

This study contributes to the broader discourse on religious soundscapes, memory politics, and postcolonial trauma by demonstrating how auditory aesthetics can reveal cultural tensions and offer modes of healing beyond the visual. Chong Keat Aun's film exemplifies how sound—especially when operating across religious and cultural registers—can invoke the unspeakable, mediate mourning, and articulate a path toward spiritual and ethical restoration. Through its auditory poetics, Snow in Midsummer opens a space for rethinking how we hear history, remember violence, and co-inhabit a pluralistic but wounded nation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XJ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. RS: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Financial support was provided by the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Malaya.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Althusser, L. (2001). “Ideology and ideological state apparatuses (Notes towards an investigation),” in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, Transl by. B. Brewster (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press), 85–126.

Assmann, J. (2011). Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Azizan, M. A. (2024). Tunku Abdul Rahman: tindakan pencetus peristiwa 13 Mei 1969. MINDEN J. Hist. Archaeol. 1, 105–116. Available online at: https://ejournal.usm.my/mjha/article/view/4887

Bao, C. (抱城). (2023). [Film] Snow in midsummer: the heavens have not sent snow, and the injustice has been forgotten [《五月雪》: 天公未降大雪, 冤, 卻已被遺忘] Available online at: https://vocus.cc/article/656dbe3dfd89780001a6650f (Accessed August 16, 2025).

Beck, G. L. (2006). Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions. Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Butler, J. (2011). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Oxford: Taylor and Francis.

Chang, Y. T. (張硯拓). (2023). Ten things you want to know after watching “Snow in Midsummer” (釀專文|看完《五月雪》的你會想知道的十件事). Available online at: https://vocus.cc/article/654c4fd4fd8978000174021c (Accessed June 15, 2025).

Das, V. (2006). Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Daughtry, J. M. (2015). Listening to War: Sound, Music, Trauma, and Survival in Wartime Iraq. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DeBernardi, J. (2004). Rites of Belonging: Memory, Modernity, and Identity in a Malaysian Chinese Community. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Derrida, J. (2012). Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. New York: Routledge.

Durkheim, E. (1915). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life a Study in Religious Sociology. London: Allen and Unwin.

Feld, S. (2012). Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression, With a New Introduction by the Author. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gautier, A. M. O. (2015). Aurality: Listening and Knowledge in Nineteenth-Century Colombia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Hirsch, M. (2012). The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hirschkind, C. (2006). The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Krauss, R. E. (1986). The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: MIT Press.

LaBelle, B. (2019). Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Laub, D. (1995). “Truth and testimony: the process and the struggle,” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press), 61–75.

Matusky, P., and Beng, T. S. (2017). The Music of Malaysia: The Classical, Folk and Syncretic Traditions. London: Routledge.

Meyer, B. (2006). Religious sensations: Why Media, Aesthetics and Power Matter in the Study of Contemporary Religion. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Meyer, B. (2015). Sensational Movies: Video, Vision, and Christianity in Ghana (17). Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Meyer, B. (2012). Mediation and the Genesis of Presence. Towards a Material Approach to Religion. Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht.

Minh-ha, T. T. (1989). Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Reid, A. (1969). The Kuala Lumpur riots and the Malaysian political system. Aust. Outlook 23, 258–278. doi: 10.1080/10357716908444353

Schafer, R. M. (1993a). The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Show, Y. X. (2021). Narrating the racial riots of 13 May 1969: gender and postmemory in Malaysian literature. South East Asia Res. 29, 214–230. doi: 10.1080/0967828X.2021.1914515

Sturken, M., and Cartwright, L. (2016). Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swallow Wings Films (海鵬 影業). (2023). Snow in midsummer - Behind the scenes EP. 2: 1969, The Snow in Midsummer Night at Pudu (《五月雪》幕後花絮|第二篇【1969.半山芭那一夜的六月雪】), [Video]. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSTWMcDMSE4 (Accessed August 5, 2025).

Tan, S. B. (1993). Bangsawan: A Social and Stylistic History of Popular Malay Opera. New York: Oxford University Press.

Trouillot, M. R. (2015). Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Wang, D. D.-W. (2004). The Monster that is History: History, Violence, and Fictional Writing in Twentieth-Century China. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Wong, D. (2001). Sounding the Center: History and Aesthetics in Thai Buddhist Performance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wong, T. C. (王德齐). (2007). Witness to the May 13 Riot: Chinese teenager killed, Mustapha alleged Harun's family had weapons (513暴动目睹华裔少年遭杀害 慕斯达法指哈伦家早藏有武器). Available online at: https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/74859 (Accessed July 28, 2025).

Keywords: religious soundscape, traumatic listening, ritual acoustics, spectral voice, May 13 Incident, Malaysian Chinese cinema, Snow in Midsummer (2023)

Citation: Jiang X and Suboh Rb (2025) Religious soundscapes and traumatic listening: auditory memory, ritual, and spiritual space in Chong Keat Aun's Snow in Midsummer (2023). Front. Commun. 10:1648327. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1648327

Received: 17 June 2025; Accepted: 20 August 2025;

Published: 11 September 2025; Corrected: 30 September 2025.

Edited by:

Dongxu Zhang, Northeastern University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaodong Lu, Dalian University of Technology, ChinaYuan Zhang, Shenyang Jianzhu University, China

Copyright © 2025 Jiang and Suboh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xingyao Jiang, czIxMjI4NDVAc2lzd2EudW0uZWR1Lm15; Rosdeen bin Suboh, a3VkaW5AdW0uZWR1Lm15

Xingyao Jiang

Xingyao Jiang Rosdeen bin Suboh

Rosdeen bin Suboh