- 1Department of Educational Sciences, Psychology, Communication - University of Bari “A. Moro”, Bari, Italy

- 2Department of Human and Social Sciences, Universita del Salento, Lecce, Italy

- 3Department of Humanities, University of Federico II, Naples, Italy

Introduction: Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) represent a multifaceted phenomenon at the intersection of technical, social, and economic dimensions. Despite their potential to foster sustainable transitions, RECs remain relatively unfamiliar and abstract to the broader public.

Methods: This study addresses this gap by examining how persuasive communication strategies are employed in public informative videos aimed at raising awareness and encouraging citizen participation in REC projects. Drawing on the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), we investigate the extent to which analytical versus heuristic pathways are activated in media discourse on RECs. We conducted an in-depth qualitative multimodal analysis of four videos (approximately 20 minutes in total), each representing a different type of REC (solidarity-based vs. non-solidarity-based; under development vs. fully implemented) located in Southern Italy. The integrated method combined observational analysis of speech and audiovisual features, enabling a systematic exploration of verbal, paraverbal, and visual components.

Results: The analysis identified three distinct communicative strategies: (1) an analytical approach, privileging factual data, bureaucratic language, and appeals to institutional authority (Sant’Arsenio); (2) an emotional approach, centered on regional identity and collective pride (Roseto); and (3) a balanced approach, blending analytic and affective cues (Naples and San Severo). These strategies varied according to REC type and project stage, with implemented and solidarity-based projects more frequently integrating emotional and community-oriented framings.

Discussion: Findings highlight how message framing, the balance of analytic versus heuristic cues, and audiovisual choices can significantly influence public representations of RECs. Tailored communication strategies, sensitive to both project type and audience characteristics, appear crucial for fostering engagement, legitimacy, and collective identification with RECs. Implications are discussed in terms of public policy design, sustainability education, and environmental advocacy, underscoring the role of communication as a lever for promoting active energy citizenship.

1 Introduction

The psychology literature on persuasive communication in the environmental domain is rapidly expanding. Classical variables, such as pro-environmental attitudes and citizens’ engagement, can be influenced by factors such as the role of opinion leaders (Nisbet and Kotcher, 2009), the type of message and its framing (e.g., economic, health-related, or moral), the role of social and descriptive norms (Van der Linden et al., 2015; Cialdini, 2003; Gustafson et al., 2025), and pre-existing values (Corner et al., 2014). Furthermore, perceived emotions may influence energy consumption decisions (Brosch et al., 2013), emphasizing the importance of moving beyond knowledge in promoting shifting attitudes and behaviors.

This literature, however, mostly focuses on individual dynamics, whereas less attention has been devoted to community variables, collective decision-making, and group processes. The territorial dimension and place-based narratives can be essential in persuading and generating positive attitudes concerning climate change (Schweizer et al., 2013; De Simone et al., 2025; Breves, 2023). In this perspective, recent research on the social acceptance dynamics of renewable energy communities has highlighted the importance of perceived socio-political control and the so-called motivational ‘warm-glow’ effect (Bonaiuto et al., 2025). The acceptance of community energy solutions is indeed based on a complex interaction of psychosocial factors that characterize the ‘psychology of the prosumer’ (Brambati et al., 2023). Thus, even within these interesting research fields, the impact of persuasive communication on participation in pro-environmental communities has been largely neglected. In particular, among the different kinds of pro-environmental communities, Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) have been under-investigated in the psychosocial literature. These initiatives are defined as Energy Communities which generally intend, in innovative and collaborative ways, to produce, consume, and manage renewable energy, usually initiated by local community members, with the potential to generate social, economic, and environmental benefits (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020; Hoppe and De Vries, 2018; Sovacool et al., 2020). Thus, RECs are communities that exhibit strong local and interdependent relationships, especially in their ‘solidary’ intention (Adler and Heckscher, 2006). This feature makes it relevant to understand how participatory processes related to these initiatives can be fostered through persuasive processes.

To fill this gap, this work aims to propose an integrated methodological approach, meaning that both textual/verbal and audio-video features are simultaneously considered in a global analytical procedure. In line with the theoretical framework of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Briñol and Petty, 2008) as well as with the dual models in persuasive communication (Chaiken, 1989), several communicative elements concerning RECs will be outlined. The investigation of main arguments, discursive strategies, frames, and audio-visual cues will contribute to outlining the main persuasive features of video news focusing on Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) in Southern Italy, considering both their nature (solidarity-based or not) and their project status (under development or already implemented). The aim is to identify communicative strategies that may provide useful insights for fostering citizen engagement and participation by activating either analytic or heuristic processing routes.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Participatory processes and persuasive communication

Participatory processes can be explained more comprehensively when social influence and persuasive communication are considered (Verba et al., 1995). Among their benefits, these social dynamics can activate and involve even peripheral members, thereby strengthening positive beliefs and attitudes and generating a virtuous cycle for the whole community. Since participation in political and civic domains can be affected by resources, motivations, and opportunities to understand specific issues, persuasive communication can engage and motivate several, even initially peripheral, stakeholders by widening the overall knowledge about political and technical topics. More generally, persuasive communication can foster identification and narrative commitments, thus catalyzing positive beliefs and attitudes about participation (Green and Brock, 2000).

It has been widely acknowledged that communication encompasses several pathways of elaboration. Information is usually processed following (a) prior knowledge about the issue and expertise, (b) more general interest and motivation to become acquainted with a specific matter (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Briñol and Petty, 2008). In addition, how a topic is “framed” can have a sensitive impact on people’s perception and engagement (Entman, 1993). Narrative and communicative frames (about risks, benefits, social justice, and technological innovation) can affect the perception of climate change and the willingness to engage in pro-environmental actions (Nisbet, 2009). Whereas a positive frame on participation (e.g., implying collective benefits) can activate and motivate less involved persons, a negative frame (e.g., concerning risks) can have a double-faceted outcome: on the one hand, it can increase the perception of immediate need; on the other hand, it can raise fear and inaction if not adequately supported by concrete solutions. A frame focused on innovation and economic opportunities can promote positive engagement, especially among groups less sensitive to environmental issues.

In this context, the visual dimension can support communicative performance effectiveness (Gleeson, 2012; Seo et al., 2013) by offering ease of understanding as well as suggestive, vivid, and even stereotypical images of a community. Through various means, visual cues can persuade targets from several cultural backgrounds and groups with varying levels of interest in the message, as emotionality and commitment are cross-checked.

2.2 The Elaboration Likelihood Model: understanding heuristic and analytical cues in REC communication processes

Following the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Briñol and Petty, 2008; Chaiken, 1989), linguistic, rhetorical, and audio-visual elements concur to activate either central/analytic or peripheral/heuristic elaboration pathways depending on the targets’ cognitive and motivational states. Two persuasive pathways are thus acknowledged: in the central route, individuals deeply elaborate messages through an accurate evaluation of data and logical arguments; in the heuristic route, individuals mostly rely on cognitive shortcuts (e.g., emotions, trustworthy testimonials, popular beliefs). Analytical processing will be more likely when targets are highly motivated and skilled; conversely, low-motivated and low-skilled targets will probably be more influenced by heuristic cues (e.g., rhetorical strategies). In the political domain, Poggi and D’Errico (2022) stressed the role of multimodal communication in activating a persuasive process, specifically through heuristic processing, even among low-skilled or motivated potential voters. Heuristic cues, such as body markers, used to multimodally discredit, convey charisma and dominance/humility, can lead the targets to perceive high/low trustworthiness, thus impacting some active behavior, such as voting and participation (D’Errico and Poggi, 2012; Poggi et al., 2011; Vincze and Poggi, 2022; Signorello et al., 2012).

Even in the institutional advertising concerning the COVID-19 emergency (Scardigno et al., 2023), a varied mix of central and peripheral multimodal cues was used following the different stages and waves of the pandemic. Especially during the initial period (aimed at facing the crisis) and the final phase (the pro-vaccine campaign), the engagement of celebrities from all entertainment spheres, emotional songs, symbolic gestures, and other heuristic cues promoted widespread heuristic information processing.

While the impact of dual communication has been widely acknowledged across a variety of domains (Scardigno et al., 2023), its influence on different target audiences (e.g., local vs. national; having different backgrounds or previous knowledge about the field) and types of community remains largely unknown. Adler and Heckscher (2006) emphasized that ‘collaborative’ communities align with both individual and collectivistic values: their members’ social identity is constructed through trusting relationships. This scenario differs significantly from ‘market-based’ communities, where identities and values are individual-oriented, no matter the role of belonging and interpersonal relations.

In the wider domain of organizational social responsibility, persuasive communication has been found to legitimize business concerning sustainability through discursive strategies related to the Aristotelian rhetoric: logos, ethos, and pathos (Higgins and Walker, 2012). The ‘ethos’ of a company’s credibility and the ‘pathos’ related to emotion elicitation can activate heuristic processing, thus facilitating overall acceptance and bypassing a careful control process. Conversely, the use of ‘logos’ and more rational arguments can foster a systematic processing of corporate responsibility. The complementary application of persuasive pathways can orient the acceptance and interpretation of specific narratives and affect the targets’ beliefs and attitudes. As an interesting applied field, understanding beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors can enhance the whole communication system, aligning with the targets’ informative needs and characteristics.

The Elaboration Likelihood Model was also used to emphasize the role of persuasive cues in participating in public decision-making processes, including through digital tools (Lee et al., 2017). The central pathway was manipulated by personal relevance, that is, tailoring the message with the addressee’s interests; the peripheral route was activated through contextual relevance, social proof, and prestigious enunciators. The combined use of central and peripheral cues was more efficient in engaging targets compared to using only one type of cue. Specifically, while personal relevance increased the elaboration time, it did not significantly impact participation; social proof and authority augmented the attention and the elaboration time, but they also did not improve participation. Conversely, matching personal preference and trustworthy authority improved participation, thus confirming that the application of ELM can affect public engagement in environmental sustainability. These insights regarding the effective combination of rational and emotional pathways can support governmental institutions in improving communication strategies aimed at achieving the overall goals of digital democracy and participation (Lee et al., 2017).

Beyond these examples, the Elaboration Likelihood Model has been widely applied in several public and social domains. However, to the best of our knowledge, scholars have devoted limited attention to environmental issues and, specifically, to Renewable Energy Communities (RECs). More generally, as highlighted in a recent review (De Simone et al., 2025), limited attention has been paid to communicative processes regarding RECs across their various domains, considering their dynamics, contents, and channels. Nevertheless, a sensitive gap exists in the psychosocial literature concerning even generic communicative features that support participation in such communities, even though communication has been identified as a crucial aspect influencing engagement and participation in RECs throughout the project’s life cycle (Dóci, 2021).

This indicates that the focus on communication has often been peripheral/tangential (Romero-Castro et al., 2023), implicit (Van Summeren et al., 2021), or ambiguous (Sloot et al., 2021). Consequently, an important research question pertains to communicative peculiarities concerning RECs, thereby contributing to understanding how speech, in conjunction with visual and sound elements, and heuristic and analytic cues, can promote involvement and engage people with RECs. To address this gap, this work investigates several communicative features concerning RECs: main arguments, discursive strategies, frames, and audio-visual cues that will contribute to outlining specific persuasive pathways in video news focused on some RECs from Southern Italy.

3 The research

3.1 Aims and research questions

This work is embedded within a broader research project investigating the psychosocial drivers and the communicative elements and dynamics that foster the implementation and development of RECs. Given the complexity of these initiatives, a variety of theoretical and analytical procedures were tested, thus proposing a comprehensive research pathway and an integrated methodology.

The current qualitative exploratory study focuses on analyzing media content used to communicate and promote RECs, specifically examining informational/explanatory videos disseminated through news outlets and online communication channels. Its exploratory nature is suitable, in line with the shortcomings identified in previous research and discussed in the theoretical background.

In this study, we tried to answer the following research questions:

a. What are the main textual features emerging from videos focused on RECs?

b. How are the analytical/heuristic pathways structured in those informative videos about RECs?

c. What salient audio/visual features emerge from video content addressing RECs?

3.2 Procedure

In order to investigate the multiple opportunities and cues offered by multimodal audiovisual communication, a database composed of 59 videos was gathered. These videos were gathered through extensive online research using the most efficient search engines (e.g., Google, Google News, YouTube). The names and locations of RECs in Southern Italy (specifically Puglia and Campania) were used as keywords. To conduct a specific and in-depth analysis of the several cues emerging from these videos, we further selected four videos for detailed analysis by matching two variables: (a) territorial dimension (region); (b) whether the RECs self-identified as “solidarity-based” or not. Solidarity-based RECs can be defined as specific Energy Communities that, while pursuing the overall aims related to the energy transition and democratization, also have the social issue as a core mission. This aim is usually achieved through several actions, including selecting participants, specific awareness-raising meetings, and other socio-educational measures (Cerreta et al., 2024). More specifically, even if all RECs are defined as grassroots innovations within a socio-technical landscape (Caramizaru and Uihlein, 2020), in some cases, the purpose of creating social innovation is more prominent. The focus on local values, emphasized through developing infrastructure and reinvesting part of the profits in the community, enabled some RECs to be identified as solidarity-based, implying that social aspects are a priority instead of more profit-based ones. As primary and secondary outcomes, in these cases, the local community can be educated in accordance with the environmental sustainability paradigm; in addition, all incomes are usually used for carrying out the state activity for civic purposes, solidarity, and social utility (Gentile, 2025).

The final sample includes videos focused on the following communities:

1. San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples), Campania, a solidarity-based REC;

2. Sant’Arsenio, Campania, a non-solidarity-based REC;

3. San Severo, Puglia, a solidarity-based REC;

4. Roseto Valfortore, Puglia, a non-solidarity-based REC.

In addition, each REC was considered in its phase of realization, ranging from still under-development projects to widely implemented communities.

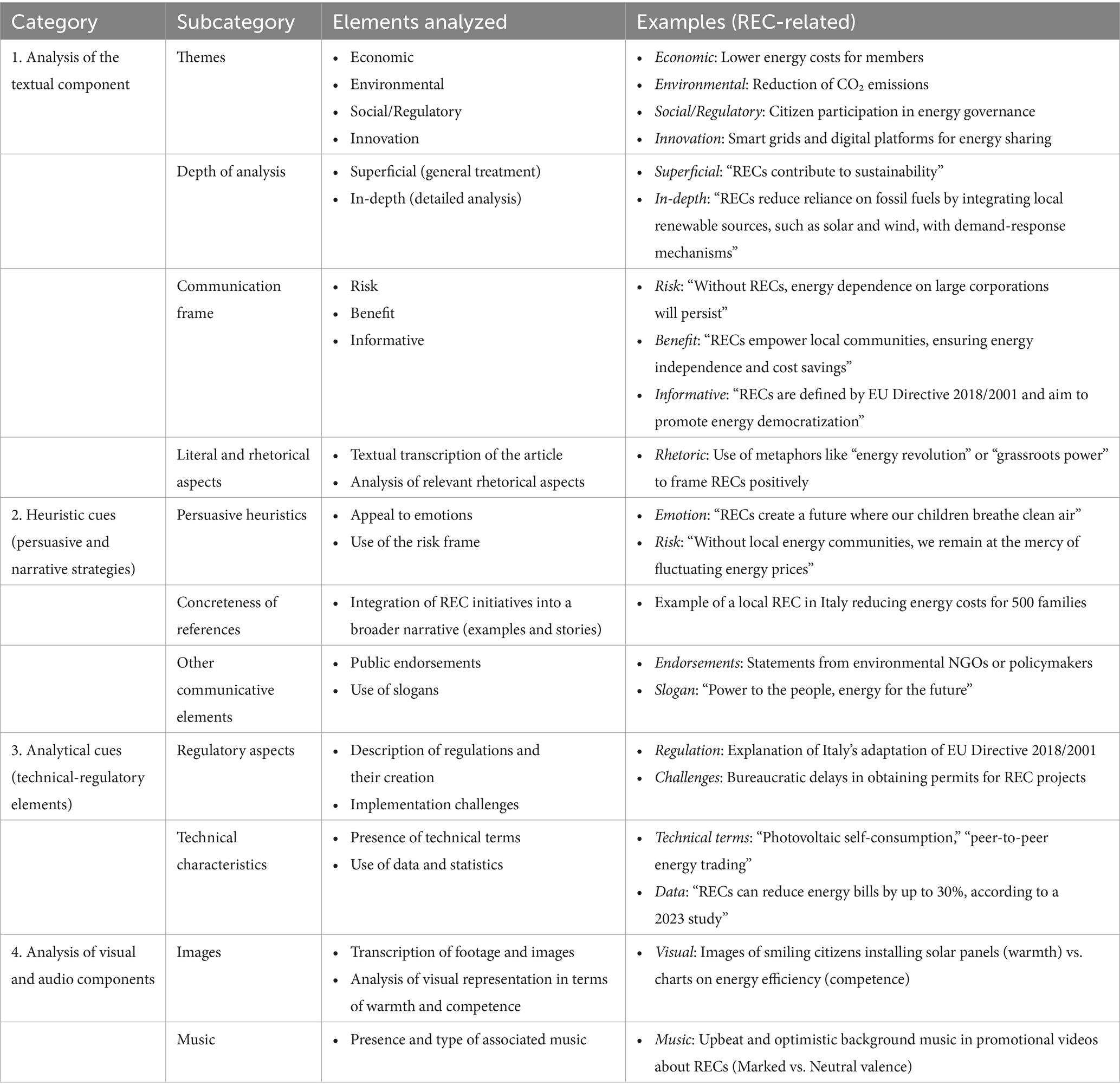

Two independent judges were trained to code each part of the four videos according to the codebook presented in Table 1, where all the variables are defined and exemplified. The codebook was specifically designed taking into account different modalities of communication (Poggi and D’Errico, 2022; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986): both content and rhetoric markers of speeches were identified; both analytic and heuristic cues were outlined; and both video and audio issues were codified. This multimodal communication observational analysis is summarized in the codebook below in Table 1.

4 Results

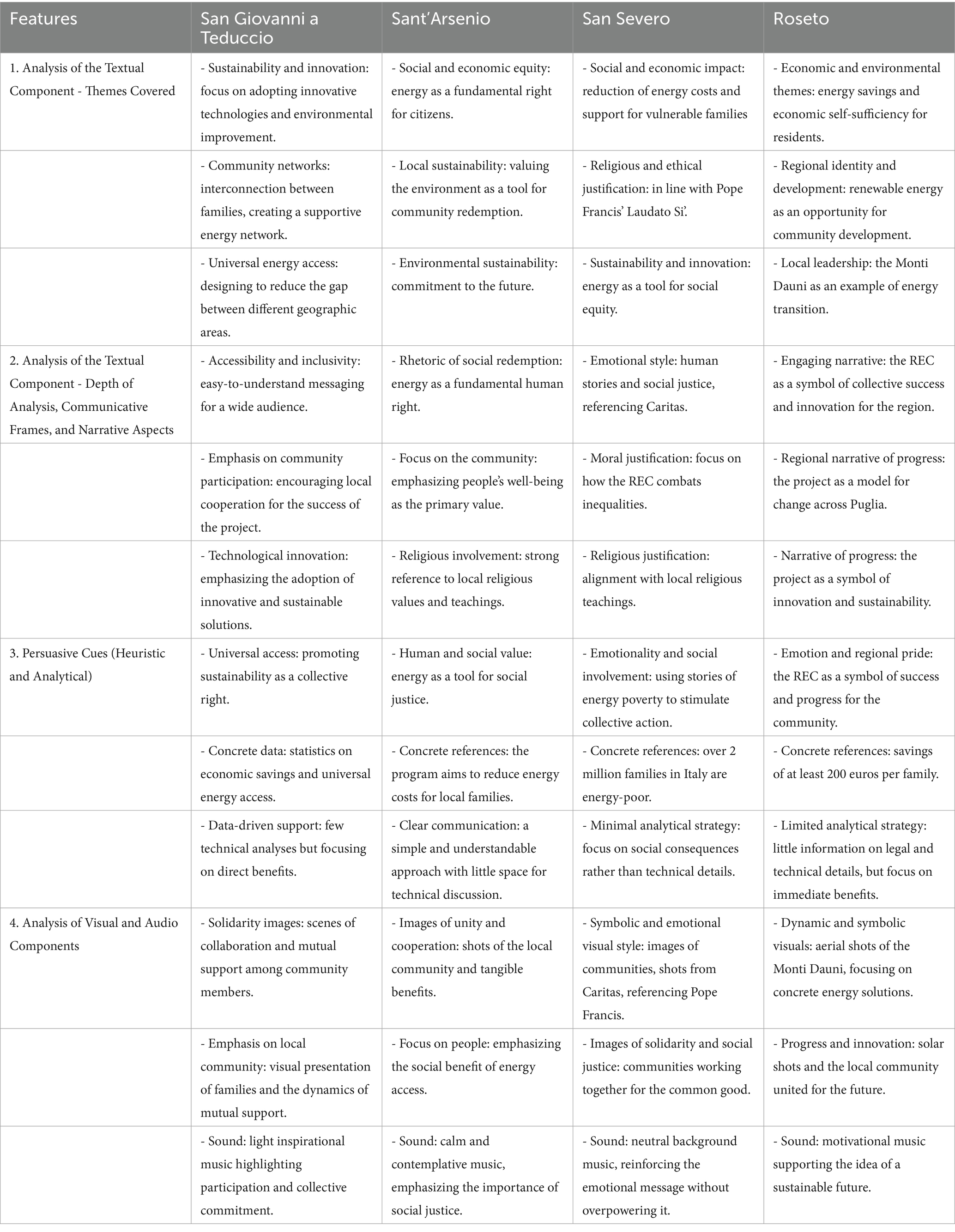

Results provide an analytical description of the communicative features, as outlined in the procedure. For each community, textual elements and references to the observed audio-visual cues are reported, organized according to the three research questions. A general overview of these findings will be presented in the discussion section (see Table 2 for a summary of the results).

Our analytical framework distinguishes three interconnected dimensions: (1) informational content (what is communicated), (2) persuasive strategies (how arguments are constructed and delivered), and (3) multimodal elements (visual and auditory support). While conceptually distinct, these dimensions operate synergistically in effective communication. Heuristic and analytical cues, as theorized in the ELM, manifest across all three dimensions, creating complex persuasive pathways tailored to diverse audiences.

The analysis reveals that communicative strategies systematically vary according to the REC’s orientation (solidarity-based/non-solidarity-based) and project phase (implemented/under development). We identified four distinct communicative configurations, each characterized by a specific balance between analytical and heuristic elements, different dominant themes, and coherent audiovisual strategies. This variation suggests that communication about RECs is inherently contextual, with persuasive approaches being tailored to match both the community’s values and the project’s maturity.

4.1 Communication profile of the San Giovanni a Teduccio REC (East Naples)

The Renewable Energy Community (REC) of “San Giovanni a Teduccio” is located in a Naples-East suburb (Naples, Campania, Italy). It is a widely implemented project. Specifically, the video about this REC was posted to YouTube on April 11th, 2022,1 and it was shot for the “Stories” column of the Italian TG2 news. The video is 4 min and 49 s long and includes some interviews with internal stakeholders/local champions, that is, the President of “Fondazione Famiglia di Maria,” the President of “Legambiente Campania,” a resident of the district of Naples-East of “San Giovanni a Teduccio,” and the President of “Fondazione con il Sud.”

4.1.1 Analysis of the textual component—themes covered

The video addresses four main themes, focusing on the economic and social impact of the initiative. It emphasizes how REC can improve residents’ economic conditions by providing access to low-cost energy and encouraging shared consumption. This aspect is reinforced through direct statements that underscore the social value of the initiative:

“Our idea is to give vulnerable families the opportunity to access clean energy and reduce the burden of their bills.”

In addition, the social benefits are highlighted: the REC is portrayed as an initiative that strengthens the local social networks by involving associations such as Legambiente Campania and the Fondazione Famiglia di Maria. The video underscores the importance of collective participation, thus presenting the project as more than just an energy initiative:

“This project is not just about energy; it is a way to rebuild a sense of community.”

While sustainability is not the primary focus, the video includes footage of solar panels, implicitly reinforcing the connection to renewable energy. The message suggests that the initiative contributes to a broader environmental goal:

“We are reducing emissions and contributing to a more sustainable future for Naples East.”

The theme of innovation is briefly mentioned but not thoroughly examined from a technical perspective. The video acknowledges innovation as a component of the project, yet it remains a secondary focus compared to the economic and social aspects.

4.1.2 Analysis of the textual component—depth of analysis, communicative frames, and narrative aspects

The video adopts an informative and accessible approach, prioritizing clarity over technical complexity. It avoids in-depth discussions on regulatory or technological aspects, instead opting for a storytelling-driven narrative that resonates with a broad audience. Rather than presenting detailed data or legal frameworks, the focus is on practical benefits and everyday relevance.

“We want to explain simply how this initiative can help people in their daily lives.”

Regarding the Communicative Frames, we found both Informative and Benefit-Oriented Frames: The video strongly emphasizes the positive impact of the REC, highlighting its economic and social advantages. The primary goal is to convey a motivational message, reassuring residents that energy justice is achievable. The focus on fairness and equity makes the initiative more appealing and accessible to a wide range of stakeholders.

“Fair and equitable energy is possible.”

Concerning the Informative Frame, the video explains the general principles of the initiative but does not delve into potential challenges, risks, or implementation barriers. This suggests a strategic choice to maintain an optimistic tone, avoiding any discussion that might create doubt or resistance.

As to the rethorical aspects, the language used is formal yet inclusive, striking a balance between professionalism and accessibility. While it maintains an informative tone, the video also shows emotional elements, particularly when discussing the REC’s impact on the neighborhood’s quality of life, thereby reinforcing the broader narrative of community renewal and collective progress.

“Naples East needs change. This project is a first step.”

4.1.3 Persuasive cues

The video employs a range of heuristic cues to engage viewers and reinforce the importance of the Renewable Energy Community (REC). The dominant strategy is emotional appeal, with language that underscores the urgent need to make energy more accessible to vulnerable populations. By framing energy as a fundamental right rather than a privilege, the video establishes a strong moral argument that resonates with viewers.

“Energy should not be a luxury but a right for all.”

This message is further strengthened by concrete references to the neighborhood’s tangible socio-economic struggles. Instead of presenting the REC as an abstract initiative, the video situates it within the daily realities of Naples East, where many families struggle to pay their energy bills.

“Here in Naples East, many families struggle to pay their bills. This energy community can change that.”

Another key persuasive element is public endorsement. The video features well-known organizations such as Legambiente Campania and the Fondazione Famiglia di Maria, whose involvement lends credibility to the initiative.

In contrast, analytical cues, which play a crucial role in central (rational) persuasion, are largely absent or underdeveloped. The video provides only a superficial overview of regulatory aspects, avoiding specific legislative references that could clarify the legal framework surrounding the REC.

Furthermore, the technical aspects of the REC are either minimally discussed or completely absent. There is no mention of energy distribution mechanisms, efficiency rates, or integration with the existing grid. The video also lacks data and statistics, prioritizing personal stories and testimonies over numerical evidence. While this approach enhances emotional engagement, real-life examples, and endorsements, it limits the depth of rational persuasion, making the video more appealing to a general audience but less informative for experts or policymakers.

4.1.4 Analysis of visual and audio components

The video strategically employs visual elements to contextualize the energy community (REC) project within the urban and social landscape of Naples East. Aerial shots of the neighborhood provide an immediate sense of place, showcasing the densely built environment where the initiative takes shape. This is complemented by footage of rooftops with solar panels, offering a tangible representation of the project’s impact and reinforcing its contribution to sustainable energy.

Another significant visual strategy involves the presence of a television studio setting, where a journalist discusses the project. This setting lends an authoritative and professional tone. Additionally, images depicting citizen engagement contribute to a sense of community warmth, showing that the REC is not merely a technical or bureaucratic initiative but a grassroots effort directly involving residents. The presence of experts and representatives from associations such as Legambiente Campania further strengthens the perception of competence and legitimacy.

From a sound perspective, the video begins with an oriental-style musical piece, an unusual choice that may evoke an exotic or engaging narrative style. As the video progresses, the music transitions into a more neutral background sound, ensuring that the spoken content remains the focal point.

4.2 Communication profile of the Sant’Arsenio REC

The REC of Sant’Arsenio is located in Sant’Arsenio, a city in Campania (Italy), and is an under-development project. Specifically, the video was released on YouTube on November 24th, 2023, as part of a service provided by “Infocilento,” a newspaper in the province of Salerno.2 The video is 3 min and 9 s long and includes interviews with a “City Green Light SRL” referent and the mayor of Sant’Arsenio.

4.2.1 Analysis of the textual component—themes covered

The video highlights four main themes, mainly concerning the economic and legal/regulatory dimensions.

Regarding the economic topic, the video explores the economic benefits of the REC, particularly in terms of incentives and funding mechanisms. It also touches on the community’s financial self-sufficiency, emphasizing the initiative’s sustainability from an economic standpoint. This is reinforced by statements that highlight the structured approach to establishing the REC:

“This evening, through specialized professionals in the sector, we are presenting the founding elements, the legal entity that will manage the energy community, open to citizens, private individuals, businesses, and activities from various categories.”

A significant focus is placed on the legal and regulatory framework, with discussions surrounding laws, incentives, and bureaucratic procedures necessary for the establishment of the REC:

“We are trying to speed up the procedures provided by law and utilize the economic incentives we have obtained together with other municipalities from the Campania Region.”

Although the environmental aspect is addressed, it assumes a secondary role, approached from a technical rather than an emotional perspective:

“The primary benefit of this initiative is optimizing local energy production and reducing reliance on external energy sources”.

The video briefly acknowledges the modernization of energy systems but does not delve deeply into the innovative aspects of the project. Innovation is present as a theme but remains in the background compared to the regulatory and economic considerations.

4.2.2 Analysis of the textual component—depth of analysis, communicative frames, and narrative aspects

The Sant’Arsenio REC video adopts a highly detailed and structured approach, focusing on the legal, financial, and procedural dimensions of the initiative. Unlike the San Giovanni a Teduccio REC video, which highlights community engagement and social impact, this production prioritizes regulatory compliance and technical administration. Through expert discussions and institutional speeches, the video provides an in-depth explanation of energy incentives and the steps required to establish and manage an energy community effectively.

The communicative frame is primarily informative, aiming to educate viewers rather than evoke emotional responses. The content is structured like an instructional presentation, outlining the fundamental elements needed for a legally compliant and financially viable energy community. It presents the REC as a structured entity with clear financial benefits, framed through the lens of funding opportunities and operational efficiency rather than personal financial relief.

From a rhetorical standpoint, the video features a formal and institutional tone, relying on expert opinions and official statements rather than spontaneous testimonials. The structured delivery of information minimizes the use of storytelling techniques or emotional appeals, favoring instead a technical and policy-oriented approach.

4.2.3 Persuasive cues

From the heuristic standpoint, the video exhibits minimal emotional appeal, opting instead for a structured and rational exposition of the REC’s formation and operation. While concrete references are present, they are framed in an institutional rather than personal manner, with discussions centered on legal frameworks, funding mechanisms, and regional policies rather than individual testimonials or community-driven storytelling. Public endorsements play a crucial role in establishing credibility, as regional authorities and legal experts lend institutional weight to the initiative.

In terms of analytical cues, the video provides an extensive regulatory description, thoroughly explaining the bureaucratic steps involved in establishing the REC. Although implementation challenges are not explicitly discussed, the in-depth focus on administrative procedures and legal structures implies an awareness of the complexities associated with the process. Technical aspects are well-represented, particularly concerning funding mechanisms, energy distribution models, and the administrative structure of the REC. Additionally, the video makes extensive use of data and statistics, incorporating slides that display financial projections, available funding opportunities, and procedural timelines, reinforcing the perception of the project as a well-structured and strategically planned initiative.

4.1.9 Analysis of visual and audio components

The visual and sound choices in the Sant’Arsenio REC video reinforce its institutional, professional, and highly structured approach, designed to convey credibility, technical expertise, and procedural clarity.

From a visual perspective, the setting in a council hall immediately establishes the official and administrative tone of the discussion. The presence of slides and infographics serves to illustrate technical data, legal procedures, and financial projections, ensuring that the audience is presented with factual and structured information rather than subjective narratives. Close-ups of participants in formal attire further contribute to an atmosphere of professionalism and authority, highlighting the involvement of legal experts, regional officials, and policymakers.

The absence of warmth in the imagery—such as community interactions or emotional testimonials—confirms that the primary goal is informing rather than engaging on a personal level. Instead, the emphasis is placed on competence, as seen in the expert presentations and structured discussions.

The sound components align with this formal approach. The complete absence of background music signals that the focus is solely on spoken content, reinforcing the perception of a serious, structured, and technical presentation.

4.3 Communication profile of the San Severo REC

The video is about San Severo’s REC, an under-development project in Puglia (South of Italy). It is 3 min and 56 s long, and it was released on YouTube on January 4th, 2024.3 It was shot for an Italian local news (“TGR Puglia”) and it includes interviews with the President of “Fondazione con il Sud,” two CEOs and the account manager for “Hivergy srl,” the director of Diocesan Caritas in San Severo, and the President of “Gestore dei Servizi Energetici (GSE).”

4.3.1 Analysis of the textual component—themes covered

The video highlights four main themes, mainly concerning the social and economic impacts.

The REC is presented as a means to reduce energy costs and provide financial support to vulnerable families. The initiative is framed as a step toward greater social equity, ensuring access to affordable energy for those in need. This commitment is reinforced through concrete figures by giving more substance to the economic theme:

“More than 500 families will benefit from this initiative, a concrete step towards social justice.”

A key focus of the video is the role of Caritas, a Catholic organization that supports low-income families. The REC is portrayed as a tool for improving energy access for disadvantaged communities, aligning with broader ethical and religious responsibilities. The video explicitly connects the project to Catholic social teachings:

“The Catholic world sees renewable energy as part of the responsibility to care for our common home, as called for in Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’.”

The notion of the “Common Home,” as articulated in Laudato Si′, serves as a powerful metaphor that reframes the relationship between humanity and the planet in terms of care, responsibility, and collective action, thus underscoring the inescapable interconnectedness between human societies and natural systems. This perspective underlines that caring for the Earth is not merely an environmental obligation but a profound ethical responsibility that transcends social, political, and generational boundaries. The metaphor of the common home also calls for a shift from individualistic approaches toward responsibility and collective action, integrating care for the environment with justice for the poor and vulnerable (Ferrara, 2019). Thus, sustainability is addressed as an extension of the project’s ethical mission rather than as a primary scientific or technological focus. The video presents environmental responsibility as intrinsically linked to economic and social justice:

“This is a perfect example of how environmental sustainability and economic impact work together to provide families with access to clean, affordable energy.”

The theme of innovation is briefly mentioned, primarily concerning technical advancements. However, rather than highlighting technological breakthroughs, the video frames innovation as a practical solution to economic and social challenges.

4.3.2 Analysis of the textual component—depth of analysis, communicative frames, and narrative aspects

The San Severo REC video adopts a highly accessible and emotionally engaging approach, prioritizing narrative and storytelling over technical explanations or regulatory details. The goal is to mobilize support and create a sense of urgency, positioning the REC as a social justice initiative rather than a technical or economic project.

The video offers a low level of technical detail, focusing instead on human-centered storytelling, clear and impactful.

“We must ensure that energy is not just a commodity, but a right for everyone.”

The video is structured around three main communicative frames, all aiming to reinforce a moral and ethical positioning: (1) Benefit Frame: the REC is presented as a solution to energy poverty, focusing on how it can improve the lives of struggling families. The emphasis is placed on the tangible, human impact rather than on technicalities.

“This is a project that puts people first, helping those in need gain access to energy and financial relief.”

(2) Rhetoric of Social Redemption: The project is framed as a moral and ethical duty, aligning with broader narratives of social justice. Caritas is positioned as the savior of vulnerable communities, actively working to reduce inequalities and promote fair access to energy resources.

“The fight against energy poverty is real, and we are here to make a difference.”

(3) Religious and Ethical Justification: The video strongly integrates Catholic social teachings, aligning the REC initiative with Pope Francis’s Laudato Si′, which emphasizes environmental responsibility and social equity. By invoking religious and ethical principles, the project gains moral legitimacy and reinforces a sense of collective duty.

“Inspired by Laudato Si’, we are committed to making renewable energy accessible to all.”

The textual structure of the video blends studio commentary, field interviews, and religious discourse, creating a rich and dynamic storytelling experience. Unlike more technical or institutional presentations, this video relies on emotional language to engage the audience.

The rhetorical strategy is deeply rooted in moral appeals and collective responsibility, with frequent references to justice, fairness, and solidarity.

“No one should be left behind when it comes to energy access.”

4.3.3 Persuasive cues

The San Severo REC video primarily employs heuristic cues to engage viewers, relying on emotional storytelling, social justice narratives, and moral responsibility rather than technical or regulatory explanations. The persuasive strategy of the video is built around emotional engagement and a sense of social urgency. In particular, they used emotional appeal by heavily drawing on stories of hardship, portraying energy poverty as a human rights issue. Personal testimonies and dramatic framing emphasize the need for action.

“This is not just about saving money – it’s about dignity, about giving people a fair chance.”

In addition, in this video, it recurs concrete references: the REC is presented within a broader socio-economic struggle, connecting it to poverty, inequality, and financial hardship. By linking the initiative to larger systemic issues, the video strengthens its narrative of social transformation.

“Over 2 million families in Italy live in energy poverty – this initiative is a step toward real change.”

The credibility of the project is reinforced through the direct involvement of Caritas, thus to a public endorsed and well-established Catholic organization with a strong reputation in social advocacy. Caritas’s support legitimizes the REC as a moral and humanitarian intervention rather than just a policy initiative. The video does not explicitly use catchy slogans, but its narrative structure consistently conveys a mission-driven urgency, appealing to ethics and solidarity.

As to the Analytic cues, unlike institutional or technical presentations, the San Severo REC video minimizes analytical complexity, keeping the message accessible and emotionally charged. The legal and bureaucratic framework of the REC is barely discussed, with the focus remaining on social impact rather than compliance or governance, also the analysed video avoids discussing potential difficulties or barriers, maintaining an optimistic and solution-oriented tone.

The Technical aspects are superficially mentioned. While solar energy production and financial savings are acknowledged, they are not explored in depth. Instead, the social benefits of renewable energy take precedence.

4.3.4 Analysis of visual and audio components

The San Severo REC video employs a highly emotive and symbolic visual style, reinforcing its humanitarian and ethical message. The sound design further supports this tone, creating an atmosphere of warmth, solidarity, and moral urgency.

The video’s visual language is carefully curated to emphasize the social and ethical mission of the REC, aligning it with Catholic teachings and humanitarian values.

These locations serve as powerful symbols of charity and social justice, framing the REC as an extension of San Severo’s mission to support vulnerable communities.

Outdoor Interviews and Aerial Footage of Rooftops: The juxtaposition of human-centered interviews and wide environmental shots visually connects the project’s human impact with its renewable energy solutions.

In addition, this video includes papal messages and Vatican imagery (Pope Francis’ Speech and Images of St. Peter’s Square), the video reinforces the moral and religious legitimacy of the REC, positioning it within Catholic social teaching. This spiritual dimension adds a layer of ethical persuasion beyond mere economic or environmental arguments.

In this video they are represented close-ups of smiling individuals, community gatherings, and aid centers create a strong sense of unity and empathy. The human element is central, making the REC feel personal and socially transformative rather than merely technical (theme oriented to warmth content). Unlike more institutional REC presentations, this video emphasizes moral leadership over technical expertise, focusing on social values rather than regulatory details.

The sound design complements the visual storytelling, reinforcing an atmosphere of hope and solidarity. A soft, neutral background score is used strategically. It enhances the emotional tone without overwhelming the message, maintaining a balance between engagement and clarity. The absence of dramatic or overly cinematic music ensures that the focus remains on the testimonials and ethical arguments rather than the spectacle.

4.4 Communication profile of the Roseto REC

The video is about Roseto Valfortore’s REC, an implemented project in Puglia (Italy). It is 6 min and 37 s long, and it was released on YouTube on January 27th, 2023. It was part of a service provided by “Immediato TV,” a newspaper in the province of Foggia.4 It includes interviews with the Roseto Valfortore’s mayor, the President of Roseto Valfortore’s REC, a local business owner, the Assessor Production Activities in the Puglia Region, the Assessor Welfare in the Puglia Region, the coordinator of “SNAI Monti Dauni,” the President of “GAL Meridaunia,” and the President of the Foggia province.

4.4.1 Analysis of the textual component—themes covered

The video focuses on economic and environmental themes, with an emphasis on community identity and regional development.

The REC is presented as a tool for achieving both energy savings and economic self-sufficiency for residents. The focus is not only on immediate financial benefits but also on the broader impact of sustainable energy use:

“First and foremost, the main advantage is the significant savings on energy bills, but beyond that, the true benefit is for the environment.”

Unlike other cases where sustainability is treated as a secondary concern, here it is central. The video frames clean energy as both a responsibility and an opportunity for local development, reinforcing the importance of renewable sources:

“We produce energy by harnessing the sun, and we are creating a sustainable future for Roseto.”

The community dimension is emphasized, though less institutionally compared to Sant’Arsenio. The REC is positioned as a replicable model, encouraging other municipalities to follow its example:

“This is an example that should be followed by other municipalities so that they too can realize their potential.”

While not the central focus, the REC is portrayed as a pioneering initiative for the Monti Dauni region. The video underscores local leadership in renewable energy, presenting the community as forward-thinking and determined:

“The Monti Dauni region is at the forefront of renewable energy, proving that we have the courage and determination to innovate.”

4.4.2 Analysis of the textual component—depth of analysis, communicative frames, and narrative aspects

The Roseto REC video presents a compelling vision of energy transition, balancing accessible information with an engaging narrative, focusing on storytelling and community involvement. The initiative is introduced as a transformative project, an opportunity for local development that extends beyond energy production to touch on economic relief, environmental sustainability, and regional identity.

The communicative frame is centered on tangible benefits, reinforcing the idea that the REC is not just an innovative project but a concrete solution to financial and environmental challenges. By emphasizing direct advantages—“such as annual savings of at least 200 euros per family”—the video translates a broad concept into a personal, everyday impact. For instance, a local resident interviewed in the video expresses how the reduction in energy costs allows families to allocate resources to other essential needs, making the project feel directly relevant to people’s daily lives.

In addition, it extends to a sense of territorial pride, presenting Roseto and the Monti Dauni as pioneers in the energy transition. One of the speakers proudly states, “We are showing that the Monti Dauni can be a leader in the energy transition,” reinforcing the idea that the initiative is not just about energy but about positioning the region at the forefront of sustainable innovation.

This positioning elevates the REC beyond a local initiative, framing it as a model that could inspire other communities across Puglia. The video further supports this by featuring a municipal representative who insists that:

“This is an energy model that must serve as inspiration for the rest of Puglia,” turning the project into a symbol of progress for the entire region.

Calls to action are not framed as obligations but as opportunities for citizens to take part in a broader shift toward sustainability. This is reflected in a final statement that urges residents to join the movement:

“We expect citizen participation because Puglia must take the lead in this revolution.”

The overall tone is one of optimism and momentum, inviting viewers to see the REC not as an isolated initiative but as a crucial step in a larger transformation. The video serves both as an informative piece and a motivational tool, ensuring that its audience walks away not only understanding the project but feeling inspired to support it.

4.4.3 Persuasive cues

The Roseto REC video employs both heuristic (peripheral) and analytical (central) persuasive strategies, though it leans more toward the former: the emotional appeal is strong, as the REC is framed as a symbol of regional pride and progress:

“The Monti Dauni are proving they have the strength to innovate and look to the future,” reinforcing a sense of collective achievement.

Concrete references tie the initiative to broader economic and environmental strategies, emphasizing local benefits: “This project will benefit citizens, small businesses, and the entire energy sector.”

Public endorsements from local authorities and energy experts further validate the project’s credibility. Additionally, explicit slogans, such as “Against rising energy costs, Roseto is leading the way,” make the message more impactful and memorable.

On a more analytical level, the video provides limited regulatory descriptions, avoiding deep legal discussions. Similarly, implementation challenges are not addressed, as the focus remains on the REC’s success rather than its potential difficulties. Technical aspects, such as solar energy production and distribution, are briefly mentioned but lack in-depth analysis. The use of data is minimal, with only key figures, like.

“Families will save at least 200 euros per year.”

Highlighting the project’s practical benefits without extensive statistical backing.

4.4.4 Analysis of visual and audio components

The Roseto REC video uses a combination of dynamic visuals and strategic sound elements to create an engaging and aspirational narrative.

The footage alternates between aerial views of the Monti Dauni region and community interviews, reinforcing the idea that renewable energy is deeply connected to the local territory. The landscape shots highlight Roseto as a place of progress, countering stereotypes of rural underdevelopment. Scenes of solar panels installed on local buildings visually anchor the project’s success, presenting technology as an accessible and transformative tool.

This visual strategy strengthens both the warmth of the video by emphasizing community participation and its competence, as local officials and project leaders add credibility to the initiative.

The background music is carefully chosen to evoke innovation and progress, complementing the video’s motivational tone. Rather than relying on dramatic or emotional cues, the soundscape supports the aspirational message, reinforcing the idea that the Roseto REC is a model for the future. The combination of visual and sound elements results in a persuasive and forward-looking portrayal of the project, making it both engaging and credible.

4.5 Comparative analysis across cases

When juxtaposing the four cases, significant patterns emerge along both the solidarity dimension and the implementation phase dimension. Solidarity-based RECs (San Giovanni a Teduccio and San Severo) prioritize narratives centered on social justice, frequently referencing positive impacts for vulnerable populations. The communication styles of these communities consistently emphasize collective values, ethical responsibilities, and inclusive participation. Conversely, non-solidarity RECs (Sant’Arsenio and Roseto) adopt more technically-oriented or identity-based approaches, with Sant’Arsenio foregrounding administrative and procedural aspects, while Roseto leverages regional pride and collective achievement.

The implementation phase similarly influences communicative strategies. Implemented projects (San Giovanni a Teduccio and Roseto) leverage concrete outcomes and testimonials, presenting tangible evidence of success. Their communication is grounded in achieved results rather than potential benefits. In contrast, under-development projects (San Severo and Sant’Arsenio) necessarily focus on prospective outcomes, with San Severo compensating for the lack of tangible results through stronger moral and religious appeals, while Sant’Arsenio emphasizes procedural clarity and institutional legitimacy.

5 Discussion

Psychosocial literature on persuasive communication and participation emphasized the combined use of central and peripheral pathways to promote participation, including in environmental issues (Lee et al., 2017). Even in individualistic, market-framed contexts, communication is more effective when heuristic cues accompany analytical ones, thus emphasizing social responsibility and sustainability (Higgins and Walker, 2012).

However, a notable gap was found in the literature concerning the communicative features that support participation in energy community projects, including the Renewable Energy Community. REC is acknowledged as a multifaceted construct, encompassing various technical domains and matching different layers of benefits and critical features. Although communication has been identified as a crucial aspect influencing engagement and participation in RECs throughout the project’s life cycle (Dóci, 2021), limited attention has been devoted to the investigation of the different pathways of persuasive communication and how dynamics, contents, and channels can represent opportunities to affect the targets’ intentions to be part of these communities. Since it is not yet a widespread issue, this study aimed to investigate the communicative dynamics and processes adopted to inform about those matters and sensitize and persuade citizens to participate in these projects through a variety of analytical markers deriving from speech and audio-visual analysis, thus implying an integrated approach.

The present study investigated the multimodal communicative strategies adopted in public informative videos about different types of Renewable Energy Community (REC) initiatives in Southern Italy through the application of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Briñol and Petty, 2008; Poggi and D’Errico, 2022). Our findings provide explorative insights into how varied configurations of analytic (central) and heuristic (peripheral) cues are employed to persuade and engage the public, as well as how socio-cultural context and the specific characteristics of the REC project can influence features of the communication process.

Consistent with previous research (Lee et al., 2017; Higgins and Walker, 2012), our study highlights the importance of integrating both central and peripheral pathways to persuasion in communication for environmental causes. However, our study advances the literature by demonstrating how four distinct communication styles can be identified, each characterized by a specific balance between analytic and heuristic cues, tailored visual and verbal cues, distinct persuasive aims, and audio-visual elements.

For instance, the analyzed video from San Giovanni a Teduccio (Naples) adopted a communicative approach characterized by a harmonious integration of emotional and analytic content. Here, the message emphasized social and economic benefits, using accessible and inclusive language to address the whole community. The inclusion of authentic imagery, such as scenes from neighborhood life and renewable energy installations, along with background music, created an environment that facilitated both rational understanding and emotional resonance. This blend likely enhances viewers’ identification with the project, making participation feel both personally and collectively meaningful. Interestingly, the communication seemed to activate not only the content of “warmth” typically associated with Southern Italian communities (Fiske et al., 2007), but also to construct a counter-stereotypical image centered on competence and capacity for social improvement.

A similar, yet even more emotionally charged, heuristic pathway emerged in the San Severo video. Here, the persuasive appeal was underlined by explicit references to social justice (“No one should be left behind when it comes to energy access”), religious values (“Inspired by Laudato Si′…”), and humanitarian impact (“The fight against energy poverty is real, and we are here to make a difference”). The imagery of charity, active help, and religious symbols reinforced stereotypical themes of warmth and community (Fiske et al., 2007), augmented by affective music that encouraged empathy and moral engagement. Rational arguments and technical data were secondary, indicating that in solidarity-focused RECs, human values and emotional resonance are prioritized over analytical depth. This aligns with the notion that solidarity-based collective action benefits from moral and identity-based motivation (Di Bernardo et al., 2021).

The Roseto video represents a third configuration, where regional identity and group belonging are central. This video privileged heuristic cues, particularly those evoking collective pride and regional leadership (“The Monti Dauni are proving they have the strength to innovate…”). The use of aerial imagery, motivational language, and uplifting music contributed to a narrative centered on competence, progress, and innovation. Unlike San Severo, the focus here was not on humanitarianism, but rather on local pride and the empowerment of the community as a regional actor capable of leading energy transition. Such collective pride can be a powerful motivator when engagement depends on local or territorial identity rather than purely moral values (Martin, 2003).

In contrast, the Sant’Arsenio video was characterized by a predominance of analytic communicative cues. The language used was technical and bureaucratic, focused on data, regulations, official processes, and expert authority. The visual style supported this, highlighting formal documents, meetings, and slides, with a notable absence of background music. This austere style likely signals credibility and seriousness (reinforcing perceptions of authority and competence; Vincze and Poggi, 2022), but may risk alienating lay audiences or those for whom emotional connection is important. Such an approach may be suitable for audiences already predisposed toward analytic processing or in contexts where legal/normative framing is required.

A cross-comparison of the cases revealed a meaningful pattern: the choice of communicative strategy is closely linked to the context and aims of the specific REC project. In solidarity-based communities (such as San Giovanni a Teduccio and San Severo; Cerreta et al., 2024), where values, knowledge-sharing, and social ties are central, communication leverages emotion, shared identity, and moral appeals to foster engagement and participation. In standard (non-solidarity) RECs, the focus shifts toward the technical and the rational, with communication that values objectivity, transparency, and procedural detail.

A key insight is the distinction between solidarity-based RECs (such as San Giovanni a Teduccio and San Severo) and non-solidarity-based RECs (like Sant’Arsenio and Roseto), each one adopting unique framings of the energy transition and deploying specific communication strategies. Solidarity RECs emphasize energy as a fundamental social right and frame their narratives around moral obligations and social justice. A core argument for these communities concerns the well-being of vulnerable populations. In these cases, energy is not defined as a commodity, but rather as a means of restoring dignity and reducing inequality. San Giovanni a Teduccio, for instance, explicitly identifies its mission as helping vulnerable families access affordable energy, tying clean energy to economic relief and profound social transformation. San Severo goes further, invoking the Catholic doctrine of ‘Laudato Si’ to frame renewable energy as a spiritual responsibility and collaborating with Caritas to reinforce messages of compassion and social care. The rhetoric in these cases is highly emotive, with appeals like “This is not just about saving money – it’s about dignity, about giving people a fair chance.”

In contrast, non-solidarity-based RECs approach energy as an economic and technical opportunity, aligning their communication with principles of efficiency, innovation, and strategic regional development. Their discourse emphasizes institutional and policy frameworks, focusing on regulatory compliance, economic incentives, and long-term viability. For example, Sant’Arsenio highlights financial and regulatory aspects, stating, “Through this project, we aim to facilitate regulatory compliance.” Roseto amplifies regional pride, presenting the Monti Dauni as a model for energy innovation and sustainability.

Moreover, videos concerning already implemented RECs (e.g., San Giovanni a Teduccio and San Severo) appeared more complex and interactive, clearly structured toward engagement and involvement. In contrast, communication about under-development communities (such as Sant’Arsenio and, to a lesser extent, Roseto) was more technical, less emotionally engaging, and appeared more concerned with information provision than with persuasion. This appears consistent with previous studies: Dóci (2021) highlights how effective communication and persuasion processes are adjusted to the various stages of the project. The primary purpose of the initial phase of the projects is to inform community members about current developments (which is consistent with the informative and technical nature of communication procedures found in the under-development RECs analyzed). On the other hand, the primary goal of the second phase, when the RECs had already been implemented, was to allow participants to provide feedback or ask questions. It typically took the shape of information events or face-to-face interactions, allowing the initiators to persuade skeptics and opponents (Dóci, 2021). Thus, it is reasonable to think that in this phase, communicative processes will be more focused on people’s persuasion and engagement, using a balanced mix of heuristic and analytic cues.

These findings extend previous theoretical frameworks by demonstrating that the balance of analytic and heuristic cues is not fixed but varies according to project maturity/stage, community context (solidarity-based vs. non-solidarity-based; Cerreta et al., 2024), and specific persuasive objectives. They suggest that future frameworks for REC communication should more explicitly account for the interplay between analytic and heuristic – sometimes even identity-based – tactics, and consider how, for instance, counter-stereotypical cues may be strategically mobilized.

More generally, this study also pursued a theoretical objective, that is, to examine whether the proposed framework could be meaningfully applied to the underexplored context of RECs. As a consequence, from a practical standpoint, these results offer direct utility for communicators, policymakers, and organizations promoting renewable energy initiatives. First, tailoring communication style—not only in terms of analytic/heuristic content but also linguistic register, imagery, and emotional tone—appears critical for maximizing public engagement (Poggi and D’Errico, 2022). Second, leveraging social identity (whether rooted in solidarity, territorial pride, or competence) can function as a persuasive tool, particularly when aligned with community values and religious and historical narratives (Scardigno et al., 2021, 2022). Finally, the effectiveness of legalistic or analytical communication may be limited to audiences already motivated by or accustomed to technical discourses (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986).

Although the present study offers nuanced insight into the persuasive strategies employed in REC communication, it is limited by its focus on a small number of cases and its reliance on video content. Even if this point can be a critical point concerning the overall external validity, it should be argued that, in qualitative methods, there is a wide-ranging discussion concerning validation criteria that can differ from those in quantitative methods (e.g., Konradsen et al., 2013). However, future research should expand the analyzed video sample and also extend to other media (e.g., social media campaigns, in-person events), examine audience reception more directly (e.g., through experimental or survey methods), and investigate cross-cultural differences in how such communication strategies play out.

Thus, this exploratory study has other limitations. The dataset was limited by the availability of Southern Italian video news concerning RECs, and the sources themselves varied in their broadcasting scope (local vs. national), which may have implicitly influenced content and comparability. However, the variety in origin can itself be considered a meaningful variable in communication, reflecting the multi-layered reach and framing efforts of the RECs.

Nevertheless, some strengths points can be identified: due to the low focus devoted to communication processes in RECs, specifically concerning speech and audio-visual cues, this exploratory, qualitative and in-depth work has enabled scholars to deeply comprehend the variety of opportunities and channels for communicating events related to even technical and environmental features through the proposal of an integrated method. Future research could extend these procedures by (a) testing the proposed analytical tools (pathways and variables) on other videos, both within the environmental domain and for more technical content; (b) promoting culturally oriented guidelines for effective communication aimed to informing and sensitizing target audiences. In a field where such processes are often neglected, these findings provide valuable groundwork for future research and practice.

In summary, our study demonstrates that effective public communication around REC projects is inherently context-sensitive and multifaceted, relying on a strategic balance between rational argumentation and affective, identity-based engagement. This has significant implications for designing campaigns that not only inform but also actively inspire and mobilize diverse communities in the transition to renewable energy.

This study provides an exploratory yet integrated analysis of communicative strategies employed in public informative videos promoting RECs in Southern Italy. By applying the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986), we found that both verbal and audio-visual cues are mobilized differently in central and peripheral persuasive pathways depending on the type of REC (solidarity vs. non-solidarity) and project phase (implemented vs. under development). Overall findings suggest that solidarity-based RECs privilege emotional and moral appeals – anchored in social justice and even religious narratives –, while non-solidarity-based RECs emphasize technical, economic, and regulatory aspects, as well as regional identity and pride. Importantly, communicative strategies are not generalizable but context-dependent, thus adapting to community values, project development, and audience needs.

Beyond extending theoretical applications of the ELM to energy initiatives, this work highlights the practical importance of tailoring REC communication by strategically combining analytical and heuristic cues. Such an approach can enhance citizen engagement, strengthen trust, and foster a sense of identification with energy transition projects. Future research should broaden the empirical base across media types and cultural contexts and assess audience reception to evaluate how these communicative strategies translate into participation and long-term sustainability of RECs.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from author Carmela Sportelli upon request.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform’s terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

FD'E: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology. CS: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. ES: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. FP: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. RS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was financed by the European Union—NextGeneration EU, Mission 4, Component 1 [H53D23009640001].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WYwZLUY9wK4

2. ^https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tjjcPEr4ma4

References

Adler, P. S., and Heckscher, C. (2006). Towards collaborative community. In C. Heckscher & P. S. Adler (Eds.), The firm as a collaborative community: reconstructing trust in the knowledge economy. Oxford University Press. 11–106.

Bonaiuto, M., Fornara, F., Carrus, G., Martino, P., and Cantone, E. (2025). The social acceptance of renewable energy communities: the role of socio-political control and impure altruism. Climate 13:55. doi: 10.3390/cli13030055

Brambati, F., Ruscio, D., Biassoni, F., Hueting, R., and Tedeschi, A. (2023). Predicting acceptance and adoption of renewable energy community solutions: the prosumer psychology. Open Res. Europe 2:115. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.14950.1

Breves, P. (2023). Persuasive communication and spatial presence: a systematic literature review and conceptual model. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 47, 222–241. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2023.2169952

Briñol, P., and Petty, R. E. (2008). Embodied persuasion: fundamental processes by which bodily responses can impact attitudes. In G. R. Semin, E. R. Smith (Eds.), Embodiment grounding: social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscientific approaches, Cambridge University Press. 184–207. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511805837.009

Brosch, T., Patel, M. K., and Sander, D. (2013). Affective influences on energy-related decisions and behaviors. Front. Energy Res. 1, 1–12. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2014.00011

Caramizaru, A., and Uihlein, A. (2020). Energy communities: An overview of energy and social innovation, vol. 30083. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cerreta, M., Prisco, M., and Ciardella, C. (2024). Imagining and creating solidarity futures: from the CERS experience to the regeneration of public housing heritage in Naples. Scienze del Territorio 12, 65–75. doi: 10.36253/sdt-15712

Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 12, 105–109. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01242

Corner, A., Markowitz, E., and Pidgeon, N. (2014). Public engagement with climate change: the role of human values. WIREs Clim. Change 5, 411–422. doi: 10.1002/wcc.269

D’Errico, F., and Poggi, I. (2012). Blame the opponent! Effects of multimodal discrediting moves in public debates. Cogn. Comput. 4, 460–476. doi: 10.1007/s12559-012-9175-y

De Simone, E., Rochira, A., Procentese, F., Sportelli, C., and Mannarini, T. (2025). Psychological and social factors driving citizen involvement in renewable energy communities: a systematic review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 124:104067. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2025.104067

Di Bernardo, G. A., Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., McKeown, S., Cocco, V. M., Saguy, T., et al. (2021). Fostering social change among advantaged and disadvantaged group members: integrating intergroup contact and social identity perspectives on collective action. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 26–47. doi: 10.1177/1368430219889134

Dóci, G. (2021). Collective action with altruists: how are citizens led renewable energy communities developed? Sustainability 13:Article 2. doi: 10.3390/su13020507

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Ferrara, P. (2019). Sustainable international relations. Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato si’and the planetary implications of “integral ecology”. Religion 10:466. doi: 10.3390/rel10080466

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., and Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Gentile, I. A. M. (2025). Techno-economic assessment and benefit allocation in solidarity-based renewable energy communities (Doctoral dissertation). Turin: Politecnico di Torino.

Gleeson, K. (2012). Polytextual thematic analysis for visual data–pinning down the analytic. Visual methods in psychology. London: Routledge, 346–361.

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Gustafson, A., Goldberg, M. H., Lee, S., Remshard, M., Luttrell, A., Rosenthal, S. A., et al. (2025). Testing the durability of persuasion from moral appeals about renewable energy. Sci. Commun. 1:1011. doi: 10.1177/10755470241311011

Higgins, C., and Walker, R. (2012). Ethos, logos, pathos: strategies of persuasion in social/environmental reports. Account. Forum 36, 194–208. doi: 10.1016/j.accfor.2012.02.003

Hoppe, T., and De Vries, G. (2018). Social innovation and the energy transition. Sustainability 11:141. doi: 10.3390/su11010141

Konradsen, H., Kirkevold, M., and Olson, K. (2013). Recognizability: a strategy for assessing external validity and for facilitating knowledge transfer in qualitative research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 36, E66–E76. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e318290209d

Lee, H., Tsohou, A., and Choi, Y. (2017). Embedding persuasive features into policy issues: implications to designing public participation processes. Gov. Inf. Q. 34, 591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2017.11.006

Martin, D. G. (2003). “Place-framing” as place-making: constituting a neighborhood for organizing and activism. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 93, 730–750. doi: 10.1111/1467-8306.9303011

Nisbet, M. C. (2009). Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 51, 12–23. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.51.2.12-23

Nisbet, M. C., and Kotcher, J. E. (2009). A two-step flow of influence? Opinion-leader campaigns on climate change. Sci. Commun. 30, 328–354. doi: 10.1177/1075547008328797

Petty, R. E., and Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. New York: Springer, 1–24.

Poggi, I., and D’Errico, F. (2022). Social influence, power, and multimodal communication. London: Routledge.

Poggi, I., D’Errico, F., and Vincze, L. (2011). Agreement and its multimodal communication in debates: a qualitative analysis. Cogn. Comput. 3, 466–479. doi: 10.1007/s12559-010-9068-x

Romero-Castro, N., Ángeles López-Cabarcos, M., Miramontes-Viña, V., and Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2023). Sustainable energy transition and circular economy: the heterogeneity of potential investors in rural community renewable energy projects. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 27, 18051–18076. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02898-z

Scardigno, R., Mininni, G., Cicirelli, P. G., and D’Errico, F. (2022). The ‘glocal’ community of Matera 2019: participative processes and re-signification of cultural heritage. Sustainability 14:12673. doi: 10.3390/su141912673

Scardigno, R., Musso, P., Cicirelli, P. G., and D’Errico, F. (2023). Health communication in the time of COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative analysis of Italian advertisements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:4424. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054424

Scardigno, R., Papapicco, C., Luccarelli, V., Zagaria, A. E., Mininni, G., and D’Errico, F. (2021). The humble charisma of a white-dressed man in a desert place: pope Francis’ communicative style in the Covid-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:683259. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.683259

Schweizer, S., Davis, S., and Thompson, J. L. (2013). Changing the conversation about climate change: a theoretical framework for place-based climate change engagement. Environ. Commun. 7, 42–62. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2012.753634

Seo, K., Dillard, J. P., and Shen, F. (2013). The effects of message framing and visual image on persuasion. Commun. Q. 61, 564–583. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2013.822403