- Department of Anthropology, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia

This article investigates the mediation, circulation, and reframing of musical expressions from Eastern Indonesia—specifically Papua and Maluku—through the digital platform TikTok. Historically marginalized within Indonesia’s national cultural narrative, these regions have gained renewed visibility through the platform’s participatory and algorithmic dynamics. By conducting an interpretive analysis of viral songs such as “Aku Papua,” “Nyong Timur,” “Stecu-Stecu,” and “Pica-Pica,” etc., the essay examines how lyrics, bodily performances, and sonic aesthetics serve as modes of cultural affirmation and resistance. Drawing on theoretical insights from ethnomusicology, platform studies, and postcolonial critique, it posits that TikTok functions not only as a site of creative production but also as a stage for identity negotiation, where users transform regional vernaculars into shared digital narratives. While the platform provides visibility and symbolic inclusion, it also imposes constraints that risk commodifying identity. The paper advocates for an interdisciplinary engagement with ethnomusicology and digital anthropology to better comprehend how peripherally situated creators navigate algorithmic publics. Ultimately, this study positions music as a potent medium through which Eastern Indonesians assert presence, reconfigure representation, and contest cultural hierarchies in the digital age.

1 Introduction

Eastern Indonesia, comprising Papua and Maluku, has historically been marginalized within Indonesia’s national cultural discourse. Despite the region’s extensive ethnolinguistic and musical diversity, it has often been portrayed through reductive, exoticizing, or peripheral perspectives in mainstream media and policy narratives (Boellstorff, 2005; Heryanto, 2008). However, the advent of digital platforms such as TikTok has created a novel, decentralized space for cultural recognition, enabling marginalized voices to emerge and circulate on a global scale. TikTok’s algorithmic structure and participatory design facilitate users from peripheral regions in projecting their cultural identities (Ismail et al., 2025a; Ismail et al., 2025b), frequently through music, to wider audiences both within and beyond Indonesia (Abidin, 2021; Ismail et al., 2024; Mohan and Punathambekar, 2019).

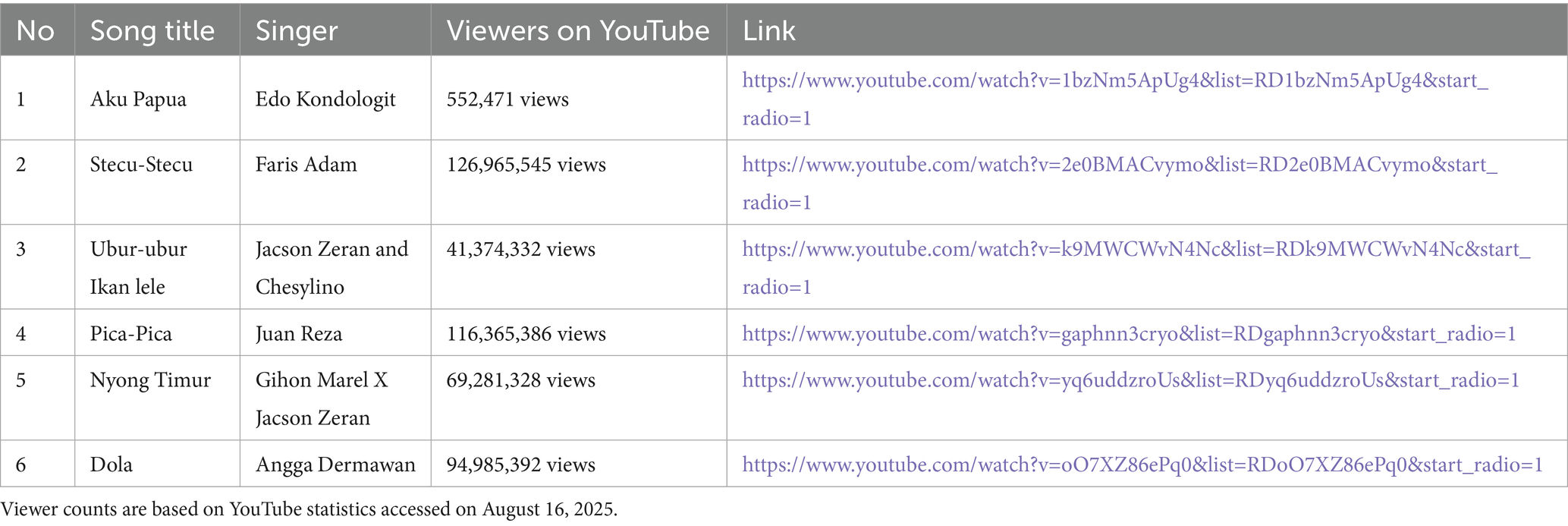

In the context of marginalization, digital platforms, particularly TikTok, have emerged as unexpected venues for cultural recognition. The platform’s algorithmic logic and rapidly shareable “microsong” formats create novel pathways for amplifying local voices (Wijaya and Rizal, 2023). Through the viral dissemination of songs such as Table 1, Eastern Indonesian musical expressions achieve unprecedented visibility, engaging both domestic and global audiences. These phenomena underscore TikTok’s capacity to transform the audience from passive listeners into active “global listeners,” engaging with regional sounds that were previously overlooked.

This article provides a critical examination of the mediation, circulation, and reframing of Eastern Indonesian musical expressions—specifically from Papua and Maluku—via the platform TikTok. Rather than presenting empirical research findings, this essay reflects on the role of music as a potent cultural vehicle in the digital age, particularly for communities historically marginalized within Indonesia’s national cultural narrative. By analyzing popular TikTok content and lyrical motifs in songs. I investigate how cultural identity is sonically and visually asserted through references to regional language and local pride.

2 Approach and material

This paper employs an interpretive analytical approach rooted in multimodal semiotics and popular music analysis to examine the articulation of Eastern Indonesian identity through digital musical content. Rather than adhering to a systematic ethnographic or empirical protocol, this perspective draws on theoretical frameworks from digital ethnomusicology and postcolonial media studies to analyze the interplay between lyrics, sound, visuals, and performance on platforms such as TikTok. The materials comprise selected viral songs and videos on Table 1, these were identified through purposive sampling based on their visibility, resonance with identity discourse, and aesthetic engagement. Analytical focus was directed towards sonic symbolism, linguistic cues, choreographic choices, and visual stylization as vehicles of cultural performance and self-assertion. Although this article does not aim for empirical generalization, it offers a situated, theoretically informed interpretation of how digital platforms mediate and amplify local identity claims. The analysis centers on meaning-making practices rather than measurement, emphasizing how creators utilize music to assert visibility within platform-driven cultural flows.

3 Sounding identity: music as cultural performance

Music serves not only as a form of entertainment but also as a potent medium for affirming cultural identity. As Rice (2007) elucidates, musical experiences encompass temporal, spatial, and embodied dimensions that shape an individual’s understanding of self and belonging. Viral songs originating from Eastern Indonesia on TikTok function as sonic texts that express pride, resistance, and regional distinctiveness. These compositions transcend mere musical products; they actively affirm presence, rooted in lived experience and mediated through the sociotechnical dynamics of the platform. In this digital milieu, cultural expression is not restricted to local stages but is amplified through networked publics that connect the periphery to the centre and the national to the global.

The musical expressions under consideration are imbued with rich semiotic layers. The lyrics are frequently articulated in regional dialects such as Ambonese, Papuan Malay, or Manado Malay, serving as auditory indicators of ethnic and linguistic distinctiveness. For instance, in the song “Nyong Timur,” the line “Kulit hitam manis, senyum tipis-tipis, pace ini tra ada dua” reclaims dark skin and facial features as positive and desirable attributes, thereby challenging prevailing beauty standards that are predominantly Java-centric or Eurocentric. Similarly, in “Tanah Papua,” the repeated affirmation “Hitam kulit, keriting rambut, aku Papua” operates both as a personal declaration and a collective anthem, emphasizing that physical characteristics are integral to the assertion of indigenous identity. These songs not only reference cultural origins but also re-signify elements that have historically been marginalized.

Within the TikTok platform, these lyrics are recontextualized as what may be termed audio-selfs—manifestations of sonic and corporeal identity embedded within platform-mediated performances. The playful yet assertive self-styling evident in songs such as “Stecu Stecu” (e.g., “nona stecu stelan cuek aduhai”) encapsulates gendered performance in relational and flirtatious contexts, wherein female and male personas negotiate desire through culturally coded signals. TikTok users enhance these relational narratives by employing video captions, camera angles, and dance styles, thereby transforming each clip into a performative declaration of their identity and origin. As Wanjala and Kebaya (2016) noted in the context of Kenyan youth, music serves as a versatile interface for navigating marginality, visibility, and belonging within urban and digital environments.

Viral success on TikTok is intricately linked to affective recognition and cultural resonance. Songs such as “Nyong Timur” achieve virality precisely because they articulate a collective identity that has frequently been marginalized. The verse “Jang tanya lai, torang gagah semua” not only asserts masculinity but also conveys defiance against national narratives that tend to overlook Eastern Indonesian pride and contributions. Similarly, “Dola” by Angga Dermawan employs vulnerability and humor, demonstrating emotional openness through expressions like “kita salah dola”—a recurring refrain of romantic failure and self-deprecation that resonates with everyday digital intimacy. Stokes (1997) conceptualizes music as a site of ongoing identity negotiation, and TikTok offers a dynamic platform for this negotiation to occur in real time, engaging with audiences both locally and globally.

The multisensory architecture of TikTok facilitates the transformation of music into performative cultural storytelling. In the song “Pica Pica,” the lyrics “Nona Ambon pica-pica, Nona NTT linca-linca, Mace Papua garis tana” delineate a sonic geography of female embodiment across Eastern Indonesia. These identities are frequently visualized through vibrant traditional attire, dynamic dance movements, and background settings that evoke specific localities. The body—styled, moving, singing—serves as a central medium for the narration of place. As Rice (2007) emphasizes, the body functions not only as a receptor of music but also as a producer of cultural meaning. On TikTok, this embodiment becomes literal: digital choreography transforms song into gesture, and presence into performance.

Ultimately, the aggregate impact of these musical practices on TikTok constitutes a form of cultural advocacy. Whether through satirical compositions such as “Faja Skali,” which critiques performative modernity (“kit kita ni manusia bukan ATM sayang”), or celebratory pieces like “Ubur-ubur Ikan Lele” (“ganteng, cantik jua oke, cuma ada di timur eee”), the underlying message remains consistent: Eastern identity is intricate, legitimate, and deserving of recognition. As Mans (2009) posits, music as a form of identity work is a dynamic process wherein traditions are not merely preserved but are continuously reimagined. Consequently, TikTok emerges not solely as a platform for content creation but as a venue for cultural assertion. These musical expressions illuminate the emotional, linguistic, and political dimensions of Eastern identity, seeking acknowledgment not through protest but through rhythm, melody, and joy.

4 Platform as stage: TikTok and the algorithmic visibility of the margins

While TikTok is frequently seen as a platform where “anyone can go viral,” this view overlooks the fact that TikTok is not impartial. Its framework is heavily influenced by algorithmic filtering, content moderation systems, and attention economies that subtly prioritize certain styles, sounds, and aesthetics. As Abidin (2021) explains through her idea of platformed visibility, TikTok controls who is visible and in what manner, based on platform-driven signals like engagement metrics, sound trends, and video formats. For content creators from Eastern Indonesia, this involves navigating visibility by strategically aligning with viral aesthetics—such as short-form dances, looping choruses, and memeable captions—while incorporating regional narratives within these limitations. Consequently, TikTok’s algorithm not only mirrors popularity but also constructs it, determining which cultural performances from the periphery gain prominence on national and global stages.

Although TikTok employs algorithmic controls, it offers features that can elevate voices from less prominent areas through formats like remix, duet, and challenge. These tools enable users to engage with, reinterpret, and collaboratively create content across distances. For example, a dance challenge inspired by “Pica Pica” can be embraced by individuals in Java, Sumatra, or even those in the diaspora, integrating Eastern musical identities into a wider network of recognition. This participatory remix culture facilitates the symbolic migration of local music, where identity is not only showcased but also performed and shared by various participants. As noted by Nieborg and Poell (2018), platformization influences cultural production by balancing personalization with standardization. While TikTok sets the format, users from Eastern Indonesia cleverly incorporate cultural markers—such as language, clothing, and gestures—into these standardized templates, preserving cultural uniqueness within the framework of mass reproducibility.

One notable feature of TikTok is its ability to enhance networked reach through viral content. The “duet” function enables local creators to align themselves with popular personalities or celebrities, establishing a sense of symbolic parity in the digital realm. This approach allows creators from the East to counter marginalization not by direct confrontation but by sharing the same space. For instance, a duet between a TikTok user from Papua and a popular influencer from Java reshapes the spatial dynamics of representation. This type of networked performance does not eliminate cultural differences; instead, it presents them as a relational advantage. Abidin (2021) refers to this as visibility labor—the process of crafting one’s cultural expression to be both algorithmically recognizable and authentic. For creators on the periphery, this labor is intensified: they must be culturally understandable to both their local audiences and the digital platform itself.

Remix and intertextual formats allow users to collectively tell the story of “Timur,” turning individual expression into a regional conversation. Recurring themes in songs like “Nyong Timur” or “Ubur-Ubur Ikan Lele”—such as references to dark skin, local dance styles, or colloquial terms—become memetic elements that are reused in users’ videos. These repeated symbols create a vibrant “cultural brand” of the East: proud, rhythmic, stylish, and emotionally impactful. As more users incorporate these themes, the identity of “Timur” evolves into a shared narrative—spread across screens, reproduced in clips, and reinforced by algorithms. Thus, TikTok serves not only as a broadcasting platform but also as a space for collaborative authorship, where regional pride becomes both infectious and established.

Another significant aspect is TikTok’s worldwide influence, which Abidin (2021) describes as creating a “global domestic audience”—individuals who are geographically separated but share a close connection through cultural consumption. For instance, a European user watching “Aku Papua” engages with Papuan identity in a way that bypasses the traditional media gatekeepers. While this global exposure does not always result in profound understanding, it does promote symbolic inclusion. For regions that have been historically marginalized, this can be transformative. The platform’s capacity to facilitate transnational attention allows cultural expressions from Indonesia’s eastern regions to reach beyond national borders, challenging the conventional center–periphery model of representation. In this context, TikTok serves as a gateway where cultural margins can directly engage with global audiences, eliminating the need for approval from Jakarta or mainstream television.

However, TikTok’s features come with certain risks. The urge to align with the platform’s aesthetics might simplify regional expressions, resulting in exoticization or a facade of authenticity. The key challenge is to preserve cultural integrity while meeting algorithmic demands. For creators in Eastern Indonesia, achieving virality presents both an opportunity and a challenge: it offers visibility but requires adaptation. As noted by Nieborg and Poell (2018), the platformization of culture often leads to the commodification of identity, pushing creators to tailor their cultural expressions to fit data-driven metrics. Yet, there is potential within this tension. Creators who can synchronize with the algorithm while grounding their performances in authentic culture have the ability to challenge the platform’s logic from within—turning TikTok into a dynamic, performative space for Eastern identity.

5 Lyrical pride and sonic belonging: case observations

Viral songs emerging from Eastern Indonesia transcend mere lyrical compositions, functioning as dynamic expressions of identity. Platforms such as TikTok and YouTube feature tracks, which evolve into audiovisual declarations—engaging bodies, rhythms, and visuals to articulate cultural pride and a sense of belonging. This section offers an interpretive analysis, rather than an ethnographic one, of selected songs and their video performances to explore how identity is expressed, styled, and disseminated across digital platforms.

In Edo Kondologit’s “Aku Papua,” the memorable chorus “Hitam kulit, keriting rambut, aku Papua” serves as a potent expression of Melanesian pride. The video situates the singer amidst Papua’s lush landscapes—hills, rivers, and forests—establishing a visual connection between identity and geography. Edo’s presence, exuding pride and confidence, is not merely passive but symbolizes cultural defiance. The harmonious integration of sound and imagery reclaims racial characteristics from historical marginalization. As Auslander (2022) notes, mediatized performance can simultaneously convey presence and resistance, and here, the Papuan body becomes a focal point of self-asserted visibility.

In a similar fashion, “Nyong Timur” expresses identity through a display of masculine aesthetics. The music video features young men from Maluku, Sulawesi, Papua, and NTT who pose, dance, and lip-sync with self-assured looks and expressive body language. The lyrics “Su kariting, mata manyala, itu katong pung ciri khas” are vividly illustrated in close-up shots of men with curly hair and dark skin, smiling with pride. Their presence challenges exoticized narratives and repositions them as central figures in cultural storytelling. This aligns with Foucault (1980) idea that bodies are arenas of power dynamics—the Eastern male body on TikTok emerges as both an aesthetic and political entity.

In compositions such as “Pica-Pica” and “Ubur-Ubur Ikan Lele,” the elements of humor and a pop sensibility are prominently featured. These works are characterized by playful lyrics, catchy rhythms, and vibrant dance routines, rendering them ideal for viral dissemination. The performance of “Nona pu goyang, pica-pica” includes dynamic group dances, with participants adorned in colorful attire and exhibiting expressions of joy. The humor embedded in these videos is significant—it captivates, entertains, and subtly redefines Eastern culture as not distant or traditional, but rather as enjoyable, contemporary, and culturally vibrant. Weaver (2010) posits that humor frequently serves as a mechanism of subtle resistance and cultural reclamation, and these performances employ it to reframe regional identity as appealing and relatable.

In “Ubur-Ubur Ikan Lele,” identity is articulated through a jubilant celebration. The lyrics “Orang timur pu manis le, soal senyum paling oke” are accompanied by smiling faces, exaggerated gestures, and dance movements tailored to align with TikTok’s style of concise, dynamic content. Although these visuals appear playful, they operate within a broader context of representational politics. They challenge deficit-based narratives by offering alternative emotional connections: joy, humor, and allure. Burgess (2007) describes this form of creativity as vernacular authorship—cultural production that emerges outside formal institutions yet holds substantial social significance.

The integration of lirik (lyric), tubuh (body), irama (rhythm), and gambar (image) constitutes what may be characterized as a sonic-visual vernacular representative of Eastern Indonesian identity. These music videos, although concise and designed for broad appeal, function as essential instruments for cultural representation. They offer emotional and aesthetic alternatives to dominant narratives, utilizing humor, pride, and rhythm to render regional culture visible, relatable, and shareable. Platforms such as TikTok and YouTube serve not merely as channels but as stages where identity is articulated, observed, and experienced in both national and international contexts.

6 Discussion and conclusion: sonic margins and the platformed future of eastern Indonesian identity

The intersection of music, algorithms, and identity on TikTok has created a significant platform for Eastern Indonesian communities—groups historically marginalized or considered peripheral in national discourse—to assert their visibility and cultural pride. Through viral songs, TikTok serves as a validating medium where sonic and visual elements—such as dark skin, vernacular language, and local dance—are transformed into expressive assets. However, this visibility is intertwined with the platform’s inherent logic: content must be optimized for virality, brevity, and aesthetic familiarity. While these affordances render Eastern identities more accessible to both national and transnational audiences, they also influence the manner in which these identities are presented, often within condensed, entertaining formats that risk oversimplifying their complexity.

The dynamic interplay between self-expression and algorithmic regulation in these performances creates a productive tension. The process of “sounding identity” is simultaneously liberating and fraught with risk. On one hand, local creators reclaim narrative agency by crafting visual and lyrical content that celebrates cultural belonging and emotional authenticity. On the other hand, the same structures that amplify their work—such as likes, loops, and challenges—may incentivize caricature or repetition. For instance, songs like “Ubur-Ubur Ikan Lele,” while joyous and humorous, may also fall into patterns where regional identity becomes a brand rather than a nuanced discourse. This underscores the ambivalence inherent in digital performance: empowerment can coexist with commodification.

As music originating from Eastern Indonesia gains prominence in digital arenas, a pivotal inquiry emerges: who governs the narrative when local compositions achieve viral status? Although numerous creators actively engage in shaping their own representation, there exists a risk of transitioning from being agents of expression to subjects of spectacle. When virality is propelled by external audiences—whether urban, central, or global—there is a potential for appropriation or oversimplification. The visibility conferred by platforms such as TikTok may thus engender recognition without comprehensive understanding, transforming rich cultural identities into digital stereotypes. This scenario necessitates critical reflection on the functioning of representation within algorithmic culture: who is permitted to articulate, who listens, and who benefits?

In anticipation of future developments, there is an imperative to advance digital ethnomusicology—a framework that not only analyzes songs but also comprehends their dissemination, performance, and mediated presence on platforms. Similarly, the nascent discipline of platform anthropology must address how regional creators from both local and diasporic backgrounds construct “sonic communities” within digital environments. These actions are not merely artistic expressions but also political acts of presence and relationality. By investigating the ways in which music traverses and evolves on platforms, scholars can reveal the socio-technical infrastructures that either facilitate or hinder cultural expression.

Moreover, this perspective necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration. The transition from sound to visibility is not solely aesthetic; it is inherently political. Music, as both a form and a force, fosters affective connections and cultural recognition, while simultaneously inviting debates concerning authenticity, ownership, and power. Addressing these complexities demands an integration of ethnomusicology, media studies, performance theory, and postcolonial critique. In this context, the examination of Eastern Indonesian musical expression on TikTok can serve as a conduit for broader discussions about voice, visibility, and the future of cultural representation in algorithmic publics.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study has been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Hasanuddin, Participants' informed consent was properly obtained. Participants' anonymity and confidentiality are fully protected. Data collection methods (in-depth interviews, participant observation, and documentation) are compliant with ethical standards for research involving human participants. The research does not pose more than minimal risk to participants.

Author contributions

AI: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. In preparing this manuscript, I used Paperpal, an AI-based academic writing assistant, solely to improve the clarity, grammar, and readability of the text. The intellectual content, conceptual framework, and critical analysis are entirely my own and have not been generated by artificial intelligence. The tool was not used to generate substantive content or conduct any part of the analysis.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abidin, C. (2021). Mapping internet celebrity on TikTok: exploring attention economies and visibility labours. Cult. Sci. 12, 77–103. doi: 10.5334/csci.140

Boellstorff, T. (2005). The gay archipelago: Sexuality and nation in Indonesia. New Jersey, United States: Princeton University Press.

Burgess, J. E. (2007). Vernacular creativity and new media [Phd, Queensland University of Technology]. Available online at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16378/ (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. New York, US: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Heryanto, A. (2008). Popular culture in Indonesia: Fluid identities in post-authoritarian politics. London: Routledge.

Ismail, A., Munsi, H., and Purwanto, S. A. (2025a). Constructing National Identity: media narratives on the naturalization of football players in Indonesia. Front. Sports Active Living 7:1595501. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2025.1595501

Ismail, A., Munsi, H., and Yusuf, A. M. (2024). A bibliometric analysis the scope of local, global, and glocal studies. Glocal Soc. J. 1, 1–13. doi: 10.31947/gs.v1i1.36119

Ismail, A., Munsi, H., Yusuf, A. M., and Hijjang, P. (2025b). Mapping one decade of identity studies: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of global trends and scholarly impact. Sociol. Sci. 14:92. doi: 10.3390/socsci14020092

Mans, M. (2009). Living in worlds of music: A view of education and values. London, New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Mohan, S., and Punathambekar, A. (2019). “Introduction: mapping global digital cultures” in Global digital cultures: Perspectives from South Asia (Michigan, US: University of Michigan Press).

Nieborg, D. B., and Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 20, 4275–4292. doi: 10.1177/1461444818769694

Rice, T. (2007). Reflections on music and identity in ethnomusicology. Muzikologija 1, 17–38. doi: 10.1177/1329878X16665177

Stokes, M. (1997). Ethnicity, identity and music: The musical construction of place. London & New York: Berg.

Wanjala, H., and Kebaya, C. (2016). Popular music and identity formation among Kenyan youth. Muziki 13, 20–35. doi: 10.1080/18125980.2016.1249159

Weaver, S. (2010). The ‘other’ laughs Back: humour and resistance in anti-racist comedy. Sociology 44, 31–48. doi: 10.1177/0038038509351624

Keywords: TikTok, cultural identity, eastern Indonesian music, digital representation, ethnomusicology

Citation: Ismail A (2025) Sounding identity in the digital age: Eastern Indonesia’s musical voices on Tiktok. Front. Commun. 10:1651788. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1651788

Edited by:

Joseph Lobo, Bulacan State University, PhilippinesReviewed by:

Iwan Awaluddin Yusuf, Universitas Islam Indonesia Fakultas Psikologi dan Ilmu Sosial Budaya, IndonesiaCopyright © 2025 Ismail. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmad Ismail, aXNtYWlsLmd1bnR1ckB1bmhhcy5hYy5pZA==

Ahmad Ismail

Ahmad Ismail