1 Introduction

The rise of digital platforms has significantly transformed the landscape of transnational cinema. Traditionally, international films were distributed through film festivals, arthouse cinemas, and limited theatrical releases. However, the emergence of streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ has democratized access to global cinema, enabling unprecedented cross-border cultural exchange. Globalization has played a crucial role in the rise of transnational cinema on digital platforms by breaking down geographical barriers and fostering cultural exchange.

Traditionally, the director has been seen as the central creative force behind a film, a view encapsulated by the “auteur theory.” Emerging from mid-twentieth-century French film criticism and later popularized by Andrew Sarris, auteur theory frames the director as the primary author whose recurring stylistic and thematic signatures define a body of work. While filmmaking has always been a collaborative effort involving writers, producers, and others, auteur theory has served as a critical lens to interpret artistic identity within cinema. In the age of digital platforms, however, this perspective is increasingly complicated by collective authorship and data-driven content strategies.

This article argues that while digital platforms have expanded access and participation in transnational cinema, they have simultaneously reshaped creative control, distribution equity, and audience agency through algorithmic governance and corporate consolidation. By analyzing key dimensions such as authorship, algorithmic curation, and cultural visibility, the paper reveals how platformised transnational cinema is both enabling and constraining new forms of global storytelling.

2 Digital platforms and the transformation of transnational cinema

2.1 Accessibility and cultural exchange

One of the most profound impacts of digital platforms is their ability to provide instant access to films from different cultural contexts. Streaming services have enabled audiences worldwide to experience diverse narratives, fostering greater cultural exchange, and representation. Unlike traditional distribution channels, which were often limited by geographic and financial constraints, digital platforms offer a vast library of international content available on demand (Lobato, 2019).

In today's global media landscape, audiences are exposed to a greater variety of cultural representations than ever before. Diasporic communities, in particular, benefit from this accessibility, using platforms like Netflix to reconnect with heritage content such as Bollywood and regional Indian cinema while participating in global media culture. However, this access does not automatically translate to cultural understanding. Superficial consumption, where audiences engage with content merely for entertainment without socio-political awareness, may lead to reductive interpretations of complex cultures. For instance, viewers may appreciate the aesthetics of a foreign film while remaining unaware of the historical, political, or linguistic nuances embedded within it. This highlights the need for both critical engagement and media education to ensure cultural exchange fosters genuine understanding rather than passive consumption.

3 Algorithmic curation and visibility

While digital platforms offer access to global content, algorithm-driven curation presents challenges related to visibility and diversity. Recommendation systems often prioritize mainstream or localized preferences, making it difficult for non-Western and independent films to gain exposure. Although many services offer sections for world cinema, these are often buried within the interface or lack strong promotion (Napoli, 2019).

Streaming algorithms aim to improve user experience by personalizing recommendations. However, they also risk creating filter bubbles, where audiences are repeatedly exposed to similar content. As a result, cultural diversity is undermined, and lesser-known perspectives are marginalized. As Duffy and Poell (2022) argue, platforms exert algorithmic control that not only influences user experience but also shapes the working conditions and visibility of cultural producers within digital economies. This highlights the need for transparent algorithm design and curated features that spotlight underrepresented regions and voices.

Additionally, commercial incentives can skew platform algorithms toward content with proven profitability, thereby discouraging experimentation with alternative or avant-garde cinema. Addressing this imbalance requires both technical solutions and ethical content policies.

4 Shifting production trends and localization

Digital platforms are not only distributors but also producers of transnational films. Companies like Netflix and Amazon have invested heavily in local-language productions, collaborating with filmmakers worldwide to create content tailored for diverse audiences. This shift has led to an increase in cross-border co-productions, blurring the lines between national and international cinema (Wayne, 2020). Local people transform global content into something tailored to their tastes. Local people rediscover the value of their own culture (Cho and Chung, 2009).

Global companies are compelled to tailor their content to suit local tastes (e.g., production companies like Sony Pictures, which produce international productions). Sony, a Japanese-owned company with a Hollywood presence, produces films across Asia, Europe, and Latin America, while also investing in local film industries in India, China, and Latin America. Other companies collaborate with international filmmakers, secure funding from various regions, and distribute their content worldwide. Examples include StudioCanal, Babelsberg Studio, and Netflix, which have produced notable films such as The Irishman (2019), and The Platform (El Hoyo) (2019, Spain).

5 Disruption of theatrical distribution

The challenges that digital technologies pose to traditional media companies exemplify what is commonly referred to as “disruptive technologies”. This aligns with Christensen et al. (2015), who define disruptive innovation as streaming services have transformed the production, distribution, and consumption of transnational films. While this shift has democratized access to international cinema, it has simultaneously introduced significant challenges for traditional media institutions and independent filmmakers.

The widespread success of streaming platforms has contributed to a marked decline in traditional theatrical distribution, especially for transnational films. Cinemas, once cultural hubs for international film screenings, have increasingly lost audiences to the convenience of on-demand home viewing. This transformation carries profound implications for the economic sustainability of global cinema. Filmmakers must now navigate new funding and distribution models, including platform-exclusive production deals and crowdfunding initiatives, rather than relying on conventional studio financing (Tryon, 2013).

Netflix exemplifies platform-led disruption, bypassing theatrical windows and consolidating distribution power through direct-to-consumer strategies. As Green (2023) explains, Netflix's business model reflects a form of “disruptive innovation,” where traditional exhibition structures are circumvented in favor of data-driven, global-first streaming. Similarly, Wayne (2020) analyses how Netflix's vertical integration from production to distribution has reshaped global film economies without relying on conventional cinema infrastructure.

Although digital platforms provide global reach, they often retain exclusive distribution rights, limiting filmmakers' ability to monetize content through alternative markets such as DVD sales, broadcast licensing, or regional syndication (Ulin, 2019). Many international films, such as The Platform (Spain), may gain worldwide exposure via Netflix but still struggle to generate revenue outside the platform ecosystem.

As Curtin et al. (2022) observe, the COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this transition toward digital-first release strategies, intensifying the pressure on theatrical models and reshaping both the economics and cultural significance of film distribution worldwide. What was once a complementary digital space has now become the primary mode of circulation, compelling stakeholders to re-evaluate the role of physical cinemas and the long-term viability of hybrid models in the global film economy.

6 Platform politics and regional access

While platforms present a façade of open access, their content libraries are curated based on regional licenses, market size, and political considerations. For example, certain films may be geo-blocked in specific countries due to censorship or regulatory concerns (Lobato, 2019; Napoli, 2019). This results in uneven accessibility and raises questions about platform neutrality.

Additionally, the dominance of a few global streaming platforms, particularly U.S.-based corporations, has raised concerns about media concentration and cultural imperialism (Miller and Maxwell, 2021). These companies often dictate content priorities, influencing what stories are told, who tells them, and how they are marketed globally (Wayne, 2020).

These issues are further reflected in the strategic differences among global platforms. Streaming platforms differ significantly in their content strategies. Netflix invests heavily in international co-productions and local-language originals in markets like South Korea and India. Disney+, by contrast, focuses on franchise-based content with minimal regional adaptation. Amazon Prime combines local productions with international acquisitions, especially in emerging markets. Regional platforms such as Hotstar and TVING serve domestic audiences while exploring global partnerships. These strategic differences highlight the need to analyze platform-specific approaches to content visibility and transnational access.

7 Audience participation and fandoms

Audiences today are not mere consumers; they serve as active participants in global cinematic culture. Viewers engage through fan communities, social media, subtitles, reviews, and campaigns to renew shows. This participatory culture has contributed to the global success of many transnational films and series (Waldfogel, 2017).

For instance, Money Heist (La Casa de Papel) became the most-watched non-English title on Netflix in 2020, reaching over 65 million households globally within its first month of release (Netflix, 2020). Likewise, The Platform (El Hoyo) ranked in Netflix's Top 10 in more than 50 countries, demonstrating the global appetite for culturally distinct yet algorithmically boosted content. These examples illustrate how fandoms, social media, and subtitling networks can amplify international visibility for content that might otherwise remain regionally confined.

Fan communities bridge linguistic divides and promote grassroots distribution, particularly for niche or non-English media. Subtitling groups play a pivotal role in circulating Asian dramas and Latin American cinema among global audiences. Such practices foster a new form of cultural diplomacy, in which viewers actively participate in transnational exchange.

Fan-driven initiatives such as community translations, TikTok reviews, and fan-made trailers now play a crucial role in building anticipation and cultivating loyal international followings. Audience preferences are also increasingly shaped by algorithmic exposure and global taste hierarchies that filter transnational content through the logics of platform visibility (Barker and Mathijs, 2023).

8 Regulatory frameworks and cultural protection

Regulators are beginning to respond to the challenges posed by digital platforms. The European Union, for instance, requires platforms like Netflix to allocate a minimum portion of their content catalog to European productions. Similar cultural quotas are being considered in countries such as Canada, Australia, and South Korea to protect local film industries (Ulin, 2019).

Policy interventions are crucial to ensuring fair visibility for regional cinema and supporting sustainable content ecosystems. Public funding, tax incentives, and fair licensing rules can provide independent filmmakers with the tools to compete in a globalized marketplace.

9 Redefining authorship in the digital era

The concept of authorship in cinema is undergoing a fundamental transformation in the age of digital platforms. Traditionally, auteur theory, originating in post-war French film criticism and later developed in Anglo-American film studies by scholars like Andrew Sarris, posited the director as the primary creative force behind a film, whose stylistic and thematic signatures could be traced across a body of work (Truffaut, 1954/1976; Sarris, 1962). While this framework offered a powerful lens for interpreting directorial identity and creative consistency, it has continuously operated more as a critical heuristic than a reflection of production realities.

In contrast, authorship is a broader and more fluid concept that encompasses the collaborative and industrial processes through which films are made. As Staiger (2003) argues, authorship must be understood as a site of negotiation, shaped by institutional, economic, and technological conditions. This is particularly true in the streaming era, where platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ have restructured the mechanisms of creative control. Here, content is often developed through writers' rooms, audience analytics, A/B testing, and algorithmically informed commissioning, decentralizing authorship and placing significant creative influence in the hands of corporate decision-makers, data scientists, and marketing teams (Wayne, 2020; Lobato, 2019).

This data-driven authorship complicates the auteur model. While streaming services still promote certain showrunners or directors as brands for instance, Ryan Murphy (Hollywood), Hwang Dong-hyuk (Squid Game), or Alex Pina (Money Heist) their creative authority is often circumscribed by platform imperatives such as user engagement metrics, genre targeting, and international marketability (Morris and Powers, 2015). In many cases, creative decisions are pre-emptively guided by algorithms predicting which narratives will perform best with segmented global audiences (Napoli, 2019). As Johnson (2021) highlights, media franchising now central to platform economies further fragments authorship across marketing, production, and data analytics teams, challenging traditional notions of creative ownership and singular artistic vision.

This shift necessitates a reframing of authorship that accounts for the hybrid nature of creative agency in the digital economy. Rather than treating data and creativity as mutually exclusive, it is more productive to view authorship as a networked process, where cultural producers, platform infrastructures, and audience behaviors are co-constitutive. As Jenkins et al. (2013) suggest in their work on spreadable media, contemporary media authorship is deeply participatory, involving audiences not just in interpretation but also in distribution, remixing, and even creative influence through fan engagement.

Therefore, the challenge is not to discard auteur theory entirely, but to critically adapt it, acknowledging its interpretive value while situating it within an industrial context where creative control is distributed, platform-driven, and often commercially optimized. Future scholarship on digital authorship must interrogate how power circulates across these networks and explore the implications for cultural diversity, artistic risk, and creative freedom.

10 Digital and media literacy in the age of platformed cinema

As digital platforms continue to shape global media consumption, it is increasingly important to develop both digital literacy and media literacy among audiences. While often used interchangeably, these terms refer to distinct but complementary sets of competencies.

Digital literacy refers to the technical and cognitive skills required to navigate digital environments. This includes using platforms effectively, managing data privacy, understanding algorithmic content delivery, and exercising informed decision-making in digital contexts (Napoli, 2019).

In contrast, media literacy involves the critical interpretation of media messages. It enables individuals to analyze representation, identify ideological bias, question authorship, and understand the sociopolitical context of media texts (Miller and Maxwell, 2021). Both forms of literacy are essential for audiences to engage meaningfully with transnational cinema.

For instance, the global accessibility of films such as The White Tiger (India), Parasite (South Korea), Hi, Mom (China), The Worst Person in the World (Norway), Photocopier (Indonesia), and The Power of the Dog (USA/New Zealand) reflects the unprecedented diversity available through streaming platforms. However, without adequate media literacy, audiences may approach these films as mere entertainment products, overlooking their cultural specificity, historical subtext, or social critique. Similarly, a lack of digital literacy may leave viewers unaware of how algorithmic recommendation systems shape the visibility of such films, potentially reinforcing cultural echo chambers.

Educational institutions, media regulators, and streaming platforms share the responsibility of fostering these literacies. Schools and universities must integrate critical media studies and digital skills training into curricula. Regulators should develop frameworks that support public media education initiatives, particularly in multicultural and multilingual societies. Streaming platforms themselves should invest in algorithmic transparency, provide curated educational content, and offer users more control over their discovery pathways, such as advanced filtering, opt-out recommendations, or access to contextual film guides.

Building these literacies is essential not only for navigating the digital landscape but also for nurturing a more informed, critical, and culturally sensitive global viewership. In an era of transnational media flows, the ability to interpret and interrogate what we watch is just as important as the ability to access it.

11 Discussion: the future of transnational cinema in the digital age

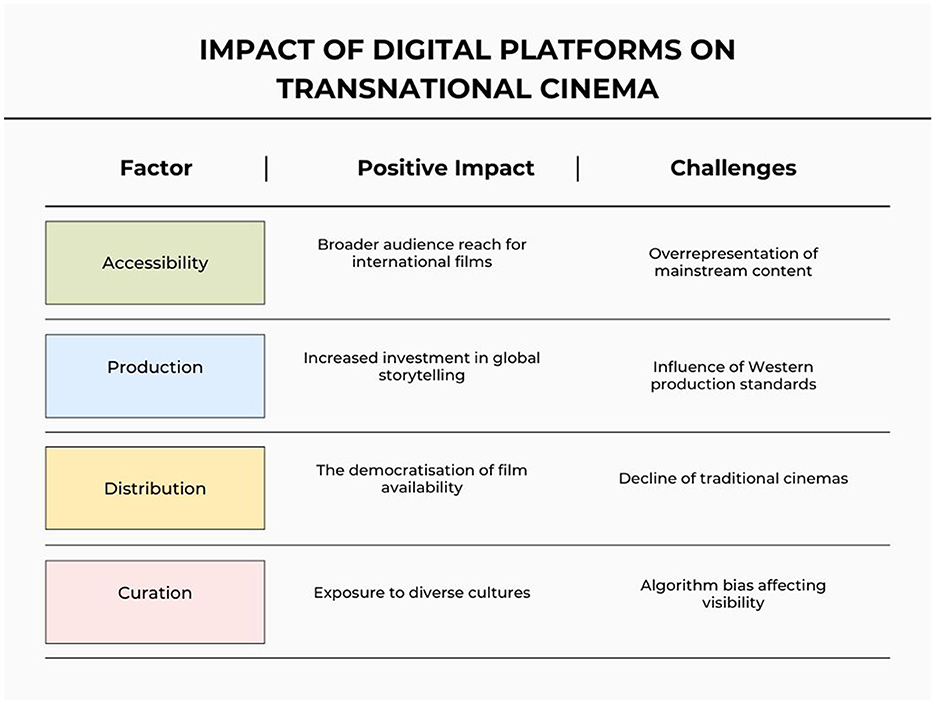

This table summarizes the dual nature of digital platforms' influence across four critical domains: accessibility, production, distribution, and curation (Figure 1). Each dimension presents both opportunities, such as broader reach and investment in global storytelling, and significant challenges, including algorithmic bias, declining cinemas, and cultural homogenization. The figure serves as a framework for understanding the complex dynamics shaping transnational cinema in the platform era.

Digital platforms have transformed transnational cinema by increasing accessibility, enhancing cultural exchange, and enabling diverse production models. However, these advancements also pose challenges. Algorithmic bias, regional licensing restrictions, and corporate monopolization hinder visibility and equitable representation (Napoli, 2019; Miller and Maxwell, 2021; Wayne, 2020). Balancing commercial interests with cultural diversity is vital to the sustainability of global cinema.

Streaming services must adopt transparent recommendation systems, prioritize authentic storytelling, and invest in underrepresented voices (Waldfogel, 2017; Lobato, 2019). Governments and cultural institutions should implement policies that protect local content industries and promote more equitable global digital ecosystems (Ulin, 2019). Audiences, too, play a pivotal role; through their viewing choices, social engagement and advocacy, they help shape the trajectory of transnational film culture (Tryon, 2013).

In conclusion, while digital platforms have significantly broadened access to transnational cinema, they have also introduced structural challenges that risk homogenizing global content. Issues such as algorithmic bias, regional disparities, and the consolidation of power among a few dominant platforms continue to undermine efforts toward genuine cultural diversity. Despite repeated scholarly and industry calls for more inclusive practices (e.g., Wayne, 2020; Cho and Chung, 2009), progress has been limited, often stalled by profit-driven algorithms, weak regulatory mechanisms, and the commercial priorities of platform monopolies.

Moving forward, the future of transnational cinema depends on a coordinated response across multiple domains. Policymakers must implement enforceable cultural quotas, mandate algorithmic transparency, and promote equitable licensing frameworks to ensure fair representation. Streaming platforms should take greater responsibility by funding underrepresented creators and designing curated discovery tools that elevate diverse voices. At the same time, empowering audiences through digital and media literacy initiatives is essential to fostering critical engagement and resisting passive consumption. Together, these efforts can support a more inclusive, decentralized, and creatively prosperous cinematic landscape, one that values cultural specificity, experimentation, and authentic storytelling on a global scale.

Author contributions

YB: Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YJ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to assist with language refinement, grammar correction, paraphrasing, and improving the clarity and coherence of academic writing. The author(s) solely developed the conceptual development, critical analysis, argumentation and all intellectual content. The author(s) have thoroughly reviewed and validated all AI-assisted outputs to ensure accuracy and originality.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Barker, M., and Mathijs, E. (2023). Audiences and cultural taste: streaming, transnationality and the global consumer. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 26, 145–162. doi: 10.1177/13678779231155507

Cho, Y., and Chung, J. (2009). Local agency and cultural globalisation. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 12(6), 485–503. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2002.1.2.7

Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., and McDonald, R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harv. Bus. Rev. 93, 44–53.

Curtin, M., Holt, J., and Samson, P. (2022). Distribution Revolution. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Duffy, B. E., and Poell, T. (2022). Algorithmic Visibility and Platform Labour. London: SAGE (New Media & Society).

Green, J. R. (2023). Netflix's complicated role as an innovative disruptor in the film industry. ESIC Digital Econ. Innov. J. 2:e057. doi: 10.55234/edeij-2-057

Johnson, D. (2021). Media franchising in the platform era. Cine. J. 60, 56–78. doi: 10.1353/cj.2021.0035

Lobato, R. (2019). Netflix Nations. New York, NY: NYU Press. doi: 10.18574/nyu/9781479895120.001.0001

Miller, T., and Maxwell, R. (2021). Global Hollywood 2. British Film Institute. Available online at: https://books.google.com.my/books/about/Global_Hollywood.html?id=DoacQgAACAAJandredir_esc=y

Morris, J. W., and Powers, D. (2015). Control, curation and musical experience in streaming music services. Creat. Ind. J. 8, 106–122. doi: 10.1080/17510694.2015.1090222

Napoli, P. M. (2019). Social Media and the Public Interest. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. https://cup.columbia.edu/book/social-media-and-the-public-interest/9780231184540

Sarris, A. (1962). Notes on the auteur theory in 1962. Film Culture, 27, 1–8. https://dn721605.ca.archive.org/0/items/film-culture-1962-no-27/film-culture-1962-no-27.pdf

Staiger, J. (2003). “Authorship approaches,” in Authorship and Film eds. D. A. Gerstner and J. Staiger (New York, NY: Routledge), 27–57.

Truffaut, F. (1954/1976). “A certain tendency of the French cinema,” in Movies and Methods: An Anthology ed. B. Nichols (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 224–237.

Ulin, J. (2019). The Business of Media Distribution. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351136624

Waldfogel, J. (2017). Digital Renaissance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9780691185439

Keywords: transnational cinema, digital platforms, streaming media, fandom, digital and media literacy

Citation: Balan Y and Jiang Y (2025) Digital platforms and the shifting landscape of transnational cinema. Front. Commun. 10:1655589. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1655589

Received: 28 June 2025; Accepted: 15 August 2025;

Published: 29 August 2025.

Edited by:

Changsong Wang, Xiamen University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Nurul Lina Mohd Nor, Taylor's University, MalaysiaMuhammad Irsyad Zulkifli, Xiamen University Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Balan and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yugeetha Balan, eWJhbGFuQHN3aW5idXJuZS5lZHUubXk=; Yuan Jiang, MTA0MjI2MzIxQHN0dWRlbnRzLnN3aW5idXJuZS5lZHUubXk=

Yugeetha Balan

Yugeetha Balan Yuan Jiang*

Yuan Jiang*