- 1IDEA Consult—Erasmus Brussels University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Brussels, Belgium

- 2IDEA Consult, Brussels, Belgium

This article explores the role of the Cultural and Creative Sectors (CCS) as systemic enablers of the European Union’s (EU) triple transition—green, digital and just. It does this by assessing how EU policy frameworks have supported or constrained that role during the 2019–2024 legislative term, and what policy options are needed in the 2024–2029 parliamentary term to more effectively mobilise the CCS as agents of change across EU transition agendas. Drawing on a comprehensive study conducted for the European Parliament’s Committee on Culture and Education (CULT), the article combines critical analysis of EU institutional documents with future-oriented interviews conducted with a dozen policy experts and stakeholders. The concept of the ‘triple transition’ has gained prominence in EU strategic discourse since 2023, adding a social justice dimension to the existing twin focus on climate neutrality and digital innovation. This shift is not merely rhetorical. The discussion argues that the just transition should be understood not as a supplementary concern, but as the very substrate upon which ecological and digital transformation must grow. It calls for a deeper engagement with societal values, participation, and cohesion; areas in which the CCS are uniquely well-positioned to contribute. Yet, this potential remains only partially realised. While policy tools like the New European Bauhaus, the Digital Services Act, Creative Europe, or the European Pillar of Social Rights acknowledge the relevance of the CCS, their operational integration across EU transition strategies remains fragmented. The article identifies critical gaps in funding models, governance coherence, infrastructure, and cross-sectoral collaboration that continue to marginalise cultural actors from key policy arenas. In response, the article proposes a dual strategic approach: first, strengthening the cultural ecosystem through improved working conditions, sustainable finance, and coordinated governance; and second, embedding the CCS more structurally in the design and implementation of transition policies. Through this lens, the article reframes the CCS not as communicative tools but as crucial co-creators of sustainable and democratic futures.

1 Introduction: cultural and creative sectors at the crossroads of Europe’s triple transition

Europe stands at a critical juncture of deeply interconnected transitions: the green transition to combat climate change and decarbonise the economy, the digital transition to enhance competitiveness, innovation and public services, and the socially just transition aimed at inclusion and cohesion (Muench et al., 2022). These transitions are often addressed through economic, technological, and regulatory lenses, but their success also depends on cultural transformation, i.e., on how individuals, organisations, communities and societies imagine, express and act upon change. In this context, the Cultural and Creative Sectors (CCS) are no longer to be seen as peripheral actors, but need to be repositioned as potential catalysts for systemic transformation across all three dimensions of the so-called triple transition (European Commission, 2023).

The CCS encompass a broad and heterogenous array of fields, including the performing and visual arts, architecture, archives, libraries, museums, artistic crafts, audiovisual media, heritage, gaming, design, festivals, music and literature (European Commission, 2021). While these sectors are in themselves rapidly evolving under ecological, technological and social changes, actors within the CCS are increasingly called upon to contribute to wider policy or societal goals: developing narratives or expressions around climate justice, experimenting with digital platforms and AI, and creating and providing spaces for inclusion, community building, and democratic debate (e.g., De Voldere et al., 2024; Voices of Culture reports; Ranczakowska et al., 2024). Yet, the question remains: how adequately do EU policies recognise and support the CCS as agents of change in Europe’s triple transition?

The Council of the European Union formalised the framing of the triple transition in its 21 November 2023 conclusions (2023/2051(INL)), emphasising that Europe’s sustainable development can only be achieved by simultaneously advancing ecological objectives, the digital agenda and a social agenda that leaves no one behind. While the earlier concept of the ‘twin’ transition—marking the intertwining transitions towards climate neutrality and digital leadership in Europe—has been integrated in EU strategic agendas and other policy documents since 2020 (e.g., in the European Commission’s New Industrial Strategy for Europe, European Commission, 2020a), policy analysts (e.g., Matti et al., 2023) have warned that this framing risks deepening inequalities if not grounded in distributive justice. In response, a third dimension has been added to the twin transition to secure a more inclusive and equitable growth path for Europe. Since 2023, the triple transition has been presented as the EU’s integrative strategy for achieving competitive sustainability: decarbonising production and consumption, harnessing digital innovation for productivity and governance gains, and ensuring that the resulting benefits—and adjustment costs—are distributed fairly across socio-economic groups, sectors’ and regions.

This article explores the EU policy landscape in relation to the CCS and assesses its capacities to position culture and creativity at the heart of the triple transition. More specifically, it addresses the following research question: how has EU policy supported the CCS in contributing to the triple transition, and what policy options exist to more effectively mobilise the sectors’ transformative potential in the 2024–2029 parliamentary term?

The analysis is grounded in the findings of a comprehensive study that we conducted for the European Parliament’s Committee on Culture and Education (CULT) (De Voldere et al., 2024). The study combined a critical analysis of EU strategic policy documents with a forward-looking expert consultation. Twelve semi-structured interviews were conducted with EU-level policy actors from across the institutional landscape, including CCS representatives, experts, thought leaders and researchers [see for more details in De Voldere et al. (2024)]. The interviewee list is integrated in the Annexes of De Voldere et al. (2024), which is freely accessible to all. The ‘strategic conversations’ (e.g., Ratcliffe, 2002) were explicitly designed to explore future-oriented perspectives, with a particular focus on the opportunities, barriers and institutional shifts required to better integrate the CCS into EU transformation agendas.

The interviews followed a modified version of the “seven-questions approach” (Amara and Lipinski, 1983) in strategic conversations, a foresight technique aimed at eliciting structured reflections on past experiences, emerging challenges, and images of the future. Participants were invited to imagine a 10-year horizon (2034), corresponding to two EU parliamentary terms, and to articulate best-case and worst-case scenarios, perceived constraints, pivotal decisions and required actions in their policy context. The resulting qualitative data were analysed using Inayatullah’s (2008) futures triangle framework, identifying structural obstacles (‘weights from the past’), current enablers (‘pushes of the present’) and images of the futures (‘pulls from the future’) to map opportunities for strategic policy change.

This policy review synthesises the outcomes of the document analysis and strategic conversations into four main parts. First, it historically maps the evolution of EU policy frameworks supporting the CCS in relation to the triple transition, highlighting key strategic, regulatory and funding developments over the past decade. Second, it analyses how the CCS have been mobilised or marginalised within the triple transition policy frameworks. Third, it articulates a forward-looking set of strategic policy options to more effectively mobilise the CCS as agents of change across EU transition agendas. Finally, it offers a reflective discussion on the structural implications of moving from a dual to a triple transition, arguing that the addition of a ‘just’ dimension renders cultural participation and inclusion not optional, but in fact essential for shaping democratic, imaginative and equitable pathways of change.

2 Mapping past EU policy approaches to supporting the CCS in the triple transition

The European Union’s policy engagement with the CCS has significantly evolved over the past two decades. Initially framed within the logic of enhancing cultural cooperation among the EU Member States (cfr. European Agenda for Culture, COM(2007)242, European Commission, 2007), the CCS have progressively become part of broader strategic agendas, ranging from economic competitiveness to the triple transition. The New European Agenda for Culture (European Commission, 2018), the Work Plans for Culture, and sectoral instruments like the European Media and Audiovisual Plan (MAAP), the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) and the Digital Services Act (DSA) have begun to articulate a broader vision of the CCS as vital contributors to societal change. Notably, culture has also featured prominently in trans-sectoral initiatives such as the New European Bauhaus, signalling an institutional opening to the transversal role of culture in EU priorities.

The COVID-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine added further urgency to this shifting policy context. As both crises disrupted the operational and financial viability of many CCS actors, the EU responded with exceptional funding and solidarity mechanisms. At the same time, these emergency measures also highlighted the longer-term structural fragilities of the CCS: precarious working conditions, fragmented governance, short-term project-based funding, fragmented digital infrastructure and underdeveloped cross-sectoral collaboration. Hence, the European Parliament’s (EP) legislative term 2019–2024 was marked by both heightened recognition for and intensified vulnerability of the sectors, which is a paradox that underscores the need for more systemic and future-oriented policy approaches (De Voldere et al., 2024).

In the EU’s 2024–2029 legislative cycle, the CCS stand at a pivotal point: will the CCS be fully recognised in its role as agent of change in the triple transition? Mapping the past decade of EU CCS policy developments (see for more details in De Voldere et al., 2024), lays the foundations for understanding future preferabilities and the need for a more coherent, future-oriented strategy. This section therefore maps the institutional and policy trajectory of EU engagement with the CCS of the past decade, identifying key regulatory, financial and strategic frameworks and assessing their alignment with the evolving demands of the green, digital and socially just transition.

2.1 Institutional context: a supportive competence

While legislative competences for CCS policies lie primarily with the EU Member States, the EU plays an important supportive and complementary role. The EU promotes cooperation among Member States and supports actions in artistic and literary creation, including the audiovisual sector, under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Despite its limited competence, the EU indirectly shapes the cultural policy landscape, mainly through funding programmes, regulatory frameworks and initiatives in related policy domains.

The European Parliament (notably the CULT Committee), the European Commission (EC) (notably the Directorate-Generals (DGs) EAC, CONNECT, RTD, REGIO, EMPL, GROW, INTPA, COMP, JUST and HOME), and the Council of the European Union (notably in the Education, Youth, Culture and Sport Council) play central roles in setting Europe’s CCS policies agenda. Next to these, other relevant institutions, organisations, agencies and EU bodies are involved in CCS policies in Europe, including for instance the European Committee of Regions (CoR), the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC), the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC), the Joint Research Centre (JRC), and the European Audiovisual Observatory. The Open Method of Coordination (OMC), structured dialogues with the sector such as Voices for Culture and the European Film Forum, and cross-sector initiatives involving civil society and Member State experts (e.g., European Capitals of Culture, New European Bauhaus) have become important vehicles for policy coordination and exchange related to the CCS.

2.2 Strategic frameworks for culture: a social turn

The early strategic framing of EU cultural policy, as taken up in the European Agenda for Culture (COM(2007)242), focused primarily on promoting cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue. However, the adoption of the New European Agenda for Culture in 2018 marked a notable shift in also embracing broader societal objectives such as social cohesion, economic innovation and Europe’s external cultural relations.

The 2018 Agenda introduced three strategic areas:

1. the social dimension, harnessing culture for social cohesion, inclusion and resilience;

2. the economic dimension, stressing the importance of the CCS as drivers of economic growth and job creation; and

3. the global dimension, emphasising the role of culture in external relations and geopolitical aims.

The New European Agenda for Culture is implemented via Work Plans for Culture, which serve as coordinating tools across Member States, identifying priorities and key actions for the EC, the Member States and the presidencies of the Council.

In an assessment report on the Work Plan 2019–2022, the EC concluded that future priorities should remain the major focuses of the past years, though with new angles on the enduring priorities (working conditions, climate change impacts) as well as with new priorities in reaction to new developments, such as the post-COVID-19 recovery and strengthening the socio-economic resilience of CCS actors (De Voldere et al., 2024).

As the COVID-19 crisis strongly revealed the structural vulnerabilities within the CCS, especially the precarious working conditions of the CCS have been acknowledged by EU policy makers. The EU Work Plan for Culture 2023–2026 of the EC includes working conditions as an important priority and proposes the development of an online platform to enable continuous exchange of information between stakeholders. A first edition of this platform—called This is How we Work—was presented in November 2023. Also in 2023, the EP developed a legislative initiative as a joint activity by the CULT and the EMPL committees, asking for a Directive on decent working conditions, for Council Decisions towards EU standards, and for adapting EU programmes to ensure that artists are paid in compliance with international labour and social standards (European Parliament, 2023).

2.3 CCS embedded in European industrial policy

Since 2020, the EU has gradually moved the CCS into EU industrial policy. The 2020 Communication “A New Industrial Strategy for Europe” (COM(2020)102) positioned Europe’s ‘innovators and creators’ as strategic assets for the green and digital transitions, signalling—for the first time in an EU industrial policy document—the competitive value of artistic and cultural know-how (European Commission, 2020b). The 2021 post-COVID-19 update of the Industrial Strategy [COM(2021)350] further embedded the CCS in the core of EU industrial policy, when the CCS were listed as one of the 14 EU industrial ecosystems (Council of the European Union, 2022; European Commission, 2021). This brought the CCS also under the Single Market monitoring system and gave them access to targeted industrial policy instruments, including to support the green and digital transition.

To further strengthen the CCS as a key economic ecosystem and support them in the digital and green transition, stimulating innovation in the CCS has become an important pillar in EU industrial policy for the CCS. In that context, an important milestone in EU CCS policies in the past years has been the establishment of the Knowledge and Innovation Community (KIC)—EIT Culture & Creativity—in 2023, funded under Horizon Europe. EIT Culture & Creativity brings together companies, cultural organizations, higher education institutions, research centers, investors, policymakers and thought leaders at the intersection of arts, science, technology and culture, with the aim to transform CCS value networks and ecosystems, ensuring they are competitive, innovative, financially sustainable and aligned with ambitious European climate neutrality and social responsibility goals.

2.4 A growing focus on regulating the digital space for the CCS

EU legislation relevant to the CCS has increased in volume and scope, particularly in response to the digital transformation. The regulatory developments mainly focus on rights-protection of creative works and fair pay in the digital age, as well as on protecting digital spaces from hate speech, misinformation, etc. Notable developments include:

• The Audiovisual Media Service Directive (AVMSD) (last revised in 2018), which counts as the cornerstone of European audiovisual policy and promotes European works in streaming services and regulates advertising and harmful content;

• The Digital Service Act (DSA, 2022) and Digital Markets Act (DMA, 2022), adopted in 2022, which aim at creating a safer and more competitive digital environment for creators and consumers;

• The Copyright Directive (2019/790) on digital single market, which addressed fair remuneration and rights in the online environment;

• The European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), adopted in 2024, which strengthens editorial independence and media pluralism;

• The Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online is a voluntary agreement established between the EC and major IT companies. Introduced in 2016, it aims to combat the spread of illegal hate speech online. Since then, the following online platforms have signed the agreement: Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter (now X), YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Dailymotion, Jeuxvideo.com, TikTok, LinkedIn, Rakuten Viber and Twitch;

• In 2022, a range of actors, such as online platforms, players from the advertising ecosystem, fact checkers, civil society, research and other organisations signed the Strengthened Code of Practice on Disinformation, aimed at combating disinformation on the internet.

While these instruments have improved regulatory coherence in the face of rapidly evolving digital technologies, challenges persist, especially around enforcement, competition with global platforms, ethical and legal risks related to AI, appropriate representation of artists and collective bargaining rights for artists (see, e.g., De Voldere et al., 2024; Dutkiewicz et al., 2024; Jacobides and Lianos, 2021; Van Raemdonck and Meyer, 2024). Moreover, the regulatory pace often lags behind the rapid evolution of technology, presenting challenges in effectively addressing emerging ethical concerns and ensuring that regulatory frameworks remain relevant to technological advancements affecting the CCS.

2.5 Funding instruments supporting the CCS in the triple transition

The EU foresees a complex web of funding streams to empower the CCS in realising the triple transition. While Creative Europe remains the sectors’ flagship funding programme, other EU funding programmes (2021–2027) have increasingly promoted CCS participation as well:

• Creative Europe has grown in budget and ambition, and supports innovation within the CCS in various ways, including through new digital technologies, innovative forms of audience engagement and innovation to strengthen social inclusion. Greening has become a programmatic priority since 2020, with the development of a Green Strategy and accompanying monitoring tools to align projects with the ambitions of the European Green Deal.

• Though not dedicated to culture, also Horizon Europe financially contributes to the green and digital transition in and with the CCS. For instance, Cluster 5 on Climate, Energy and Mobility specifically addresses the intersection between CCS and greening by funding projects that combine research on cultural preservation with environmental responsibility. Cultural projects also contribute to climate neutrality in other sectors, for example, by bringing forward traditional and innovative practices, techniques and materials resulting from cultural heritage research. Horizon Europe funds are also mobilised to stimulate innovation in and with the CCS, to support the uptake of new digital technologies (such as artificial intelligence, virtual reality, blockchain technology), fostering business model innovation (e.g., new ways of creating in the digital age, producing or monetizing cultural content, green business models) and supporting research on the preservation, digitization, and accessibility of cultural heritage, to name only a few.

• To (financially) support the post-COVID-19 recovery of the CCS, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) has been mobilised by 16 Member States to incorporate measures targeting the CCS within their plans. Four plans were directly targeted at improving the working conditions in the CCS. Seven plans foresee investments to support the green transition in the CCS. Investments relate to renovations to increase energy efficiency of cultural buildings and sites, safeguarding heritage sites from climate change and incentives for green and climate-friendly projects by cultural actors. Eight plans foresee financial support to boost innovation for the digital transformation in the CCS.

• Erasmus+ has granted EU funding in several projects that aim to strengthen the skills of CCS actors in the triple transition. The Erasmus+ funded project CHARTER (the European Cultural Heritage Skills Alliance) is an example of a project aimed at tackling the skills needed for the green transition, fostering a deeper understanding of sustainability issues among cultural actors and equipping them with the tools to implement green practices.

2.6 New European Bauhaus: the catalysing role of the CCS in the triple transition comes into view

An important initiative that explicitly aims to leverage the CCS as catalysts for the green and just transition in Europe is the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative (European Parliament, 2022), which emerged as a response to the growing urgency of the environmental crisis. Launched in September 2020 by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, the NEB aims to support a vision for a future where sustainability, aesthetics and inclusivity are interwoven. The NEB thrives on a multi-level, participatory and transdisciplinary approach, engaging a wide range of actors beyond the traditional policy domains. Central to the NEB’s philosophy is the recognition of culture and the CCS as powerful catalysts for positive societal change. The initiative acknowledges the “systemic importance” of CCS in navigating the green and digital transitions, emphasizing their potential to shape new behaviours and values.

Beyond the NEB, the CCS are looked at for their creative capacity to rediscover and revalue sustainable heritage crafts and techniques (e.g., inspiring more sustainable construction), make new economic models more attractive and to communicate the viability of new economic models, for example, by showing how they can represent growth in other capacities and forms of value, including new circular business models, reaching new markets, innovation, stability and added value for citizens (see, e.g., Voices of Culture, 2023).

3 The CCS in EU triple transition policies: mobilisation or marginalisation?

The evolution of EU policy around the CCS shows a gradual shift from peripheral cultural cooperation and promotion towards more systemic engagement with the CCS’s potential in ecological, digital and social transformation. Across the European Commission’s flagship frameworks—from the European Green Deal to the Digital Compass and the European Pillar of Social Rights—there is growing emphasis on the importance of societal imagination, behaviour change, inclusion, and health and well-being. These are all roles for which the CCS are uniquely suited. The Council resolution of 29 November 2022, approving the EU Work Plan for Culture 2023–2026, acknowledged the role of culture as an integral element in sustainable development and positive societal transformation. It also underlined the importance of mainstreaming the cultural dimension into all relevant policy areas, programmes and initiatives, and the need for increased synergies. Since then, regulatory updates, strategic frameworks and funding instruments have further matured.

Yet, as the CULT Committee study (De Voldere et al., 2024) makes clear, this recognition has not yet fully translated into consistent structural inclusion of the CCS in EU’s triple transition strategies and related funding programmes. What we observe instead, is a rather fragmented landscape where pockets of innovation and engagement coexist with persistent underinvestment, sectoral precarity and relatively weak cross-policy coordination. Their roles remain constrained by institutional fragmentation and limited transversal integration.

In this section, we critically assess the extent to which the CCS have been mobilised—or marginalised—within the three transition domains. Drawing on an analysis of institutional documentation, a dozen of strategic conversations with EU policy stakeholders and work that we do in the Horizon Europe funded project ekip (2023–2026), we examine EU’s engagement of the CCS in the green, digital and just transitions, respectively. For each transition, we tackle how the CCS are mobilised in EU discourse and policy, and what structural conditions support or hinder CCS’ systemic participation in each transition.

3.1 CCS and the EU green transition: the NEB as partial conduit

The green transition is perhaps the domain where the EU has made the clearest discursive openings toward integrating the CCS as agents of change. The New European Bauhaus (NEB), launched in 2020 as part of the European Green Deal, is the only flagship initiative that explicitly mobilises cultural and creative assets for climate goals, invoking the power of culture, design and architecture to reimagine sustainable living.

However, despite this promising discursive shift, until now the role of the CCS in the green transition has been underplayed and actual policy integration of the CCS into climate and sustainability instruments remains shallow (European Parliament, 2022). In that context, the Voices of Culture brainstorming report on CCS driving the green transition (2023) speaks about CCS involvement being “insufficient and ad-hoc.” The report calls for the European Green deal to be amended so that the CCS become a central driver of social imaginaries for a low-carbon future. The report further highlights that current instruments for the green transition are too sectorally siloed and administratively rigid to harness creative capacities at scale.

As part of the Horizon Europe project ekip, the Policy Lab investigation and recommendations report Cultural and Creative Industries Enabling Green Transitions: Is the NEB a Catalyst? (Ekip, 2024) specifically investigates the role of the NEB in leveraging the CCS’s potential for the green transition. The report concludes that while the NEB provides a fertile framework for awareness-raising experiments involving the CCS, there are four structural bottlenecks:

1. Technocratic bias. Green innovation support remains primarily oriented towards technological and industrial solutions, with limited recognition of culture’s epistemic contributions. There is no strategic recognition of the diverse skills sets that transformative innovations for the green transition require and that go beyond scientific and technological skills.

2. Built-environment filter. Because NEB is anchored in spatial design, it has especially engaged with parts of the CCS that relate to the built environment, such as architecture, design or (immovable) heritage. While NEB enabled valuable experimentation, its close association with living spaces has led to engaging primarily those parts of the CCS that relate to designing sustainable and ‘beautiful’ built environments, thereby marginalising many strands, such as music, literature, theatre, or grassroots community art that do not interface directly with architecture or heritage.

3. Project-based funding and weak governance. CCS involvement is largely confined to short-term demonstrators; CCS actors are rarely invited into strategic goal setting or innovation-road-mapping, leaving them dependent on ad-hoc calls rather than systemic investment.

4. Lack of CCS-based R&I infrastructures for green (human-centred) experimentation. The ekip report further underlines the absence of dedicated infrastructures—creative hubs, socio-cultural centres, libraries—that could operate as innovation nodes for circular experimentation, as they often lack structural financial support for engaging in such processes and are thus ill-equipped to scale local green practices. The green transition logic often seems to be externally imposed, asking the CCS to ‘green’ their own activities, rather than inviting them in truly open innovation processes to co-shape the meanings, ethics, or aesthetics of ecological change itself. Mobilisation of the CCS is visible in pilot programmes, artistic interventions and discursive framing, but has not yet reached a level of structural integration of the CCS’s innovation potential to shape the green transition.

The ekip findings are illustrative of the fact that the NEB delivers symbolic visibility to the CCS’s role in the green transition, but stops short of truly embedding them inside the core governance structures that steer climate finance, research and regulation at the European level.

As visibility and awareness raising are crucial for mainstreaming creative approaches into green innovation ecosystems, the Voices of Culture report on the role of CCS in the green transition (2023) recommends an “official EU repository of best greening practices” to inspire the CCS and beyond. Also, robust data that track CCS contributions to the green transition are important to build up evidence of their role. However, robust impact metrics remain scarce (De Voldere et al., 2024).

At the skills level, education is a particular blind spot in general to learn about the value of arts, culture and creativity in today’s society, next to science and tech. While STEAM education (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics) has already been advocated by the EP in its 2019 resolution on education in the digital era, most Member States still treat culture as ancillary to STEM and ICT higher education programmes. The necessity to take further steps in fully recognising the value of the arts in STEAM is also stressed in the Voices of Culture report on the green transition (2023, p. 43): “[…] continuous exchange must be established between STEM and CCSI in order to allow CCSI to adopt new scientific methods, and for STEM to avail itself of the creative, culture-shaping content and communication capabilities of CCSI. A necessary step further would be the real integration of art in STEM and active promotion of STEAM.”

Finally, when it comes to the skills related to the green transition in the CCS itself, the 2024 Annual Single Market and Competitiveness Report highlight important deficits in climate literacy, energy efficiency and circular-design competences among cultural professionals. Data collected for the European Monitor of Industrial Ecosystems (EMI) report on the CCS (IDEA Consult and Technopolis Group, 2023) show that supply of, and demand for, green competences are both marginal in the CCS. The report highlights that further investments in innovation are crucial to accelerate the green transformation of the CCS. Closing the gap will require targeted up- and reskilling initiatives beyond the short, project-based pilots that currently dominate. Neither Erasmus+ nor Horizon Europe currently offer structural funding for a coherent learning pathway that couples artistic practice with ecological engineering.

3.2 CCS and the EU digital transition: balancing between actively contributing to designing new digital futures and protecting creative work

Historically, EU policy support for CCS digitisation was focused on heritage preservation and content dissemination (e.g., Europeana). More recently, however, the CCS have been repositioned as part of the EU’s broader industrial and innovation strategy. The inclusion of the CCS among the 14 European industrial ecosystems in the Updated Industrial Strategy (European Commission, 2021) marks a significant institutional recognition. Also, the Creative Europe Innovation Labs and Horizon Europe calls (especially in Cluster 2) have begun to support CCS-led digital experimentation. By using immersive technologies, digital storytelling and AI-human interaction, CCS actors actively contribute to digital innovation. Moreover, initiatives such as the Common European Data Space for Cultural Heritage, the 5Dculture project, and the AI4Europeana platform demonstrate how CCS actors are actively involved in shaping Europe’s digital infrastructure. Policy Lab investigations done in the context of the Horizon Europe project ekip suggest that the digital transition could be an opportunity for the CCS to model alternative digital futures—open-source, community-based, ethically governed. Concrete blueprints are, e.g., mentioned in the ekip investigation report Platformisation of the Music Industry lab, which profiles cooperative and decentralised models.

At the same time, in the digital transition, the CCS are seen as sectors in need of protection against platform monopolies and algorithmic bias. The Digital Service Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DMA), the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA), the Copyright Directive and the AI act have all sought to regulate the digital environment to ensure fairer access and remuneration, visibility and safety for creators. These instruments offer more secure environments for creative expression online, yet enforcement remains uneven. Moreover, many CCS actors still lack the capacity to assert their rights effectively, although EU-funded projects such as Creative FLIP aim to lower the barriers with awareness raising activities and tools such as the online tool My Intellectual Property, that offers information, advice and links to existing resources about IP for CCS professionals in the digital age.

More generally, many CCS actors face barriers in accessing digital tools, digital infrastructure, or digital upskilling programmes. The digital transition is often designed with industrial scale or technical sophistication in mind, neglecting the needs and capacities of CCS actors to adapt skills in the face of the digital transition (Hausemer et al., 2021). Moreover, digital policy largely treats the CCS as users or beneficiaries of digital innovation, rather than as co-drivers of the digital public sphere. Dependency on monopolistic practices of major platforms continues to constrain artistic autonomy, while dominant algorithms tend to skew access to audiences and revenue. Although the regulatory frameworks represent important steps and offer more secure environments for creative expression online, their implementation is uneven and enforcement remains fragmented and underdeveloped (De Voldere et al., 2024).

Thus, while digital policy increasingly includes CCS in regulatory and innovation frameworks, the sectors remain structurally marginal in shaping Europe’s digital future. As highlighted in ekip policy analysis documents, current EU policy frameworks and instruments lack systemic support for accessing innovation labs, digital literacy education, cross-sectoral experimentation and sustained co-governance involving CCS actors. Mobilisation is occurring, but often on terms defined by technological or industrial logics rather than by cultural or civic ones.

3.3 CCS leveraging just transition in the EU

Quite recently, and leveraged by the COVID-19 crisis, the focus in EU policy discourse on the twin transition has shifted towards a socially just transition, which is perhaps the most intuitive transition domain for CCS engagement (Matti et al., 2023). Here, the role of the CCS is well established: cultural spaces as centres of social encounter, artistic practices enhance participation and expression, and creative work can give voice to and open up towards marginalised communities. For example, a pan-EU survey among members of the European network of cultural centres (ENCC) shows that community-run arts hubs “produce measurable gains in trust, participation and local problem-solving capacity,” positioning them as natural laboratories for a just transition (Ranczakowska et al., 2024).

Over the years, multiple discussions have been held in the OMC and Voices of Culture on themes related to culture, social cohesion and inclusion, such as on the integration of migrants and refugees in societies through the arts and culture (European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2017), the promotion of intercultural dialogue and bringing communities together through culture in shared public spaces (Voices of Culture, 2016), or on the role of culture in non-urban areas of the EU (Voices of Culture, 2020). The New European Agenda for Culture (European Commission, 2018) further strengthened the social dimension of EU cultural policy, including the social and economic importance of culture and heritage (highlighted in the 2018 European Year of Cultural Heritage) with the European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage.

The COVID-19 pandemic reaffirmed the role of the CCS in developing a just transition in Europe and created further momentum to enlarge the scope of the role of culture with regards to well-being. CCS actors mobilised rapidly to support mental health, social connection and public morale (see, e.g., IDEA Consult et al., 2021). Similarly, in response to the war in Ukraine, CCS actors provided support for refugees, countered disinformation and reinforced democratic values.

This shift came with a growing body of research and evidence about the role of culture in different aspects of well-being, both at the global and national level. The World Health Organisation (WHO) played a major role in this respect, with the 2019 report What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review (Fancourt and Finn, 2019). The report has been an important catalyst for increased understanding and visibility of the body of work done in the field of arts and health, as well as for subsequent EU initiatives related to culture and health. The Preparatory Action CultureForHealth expanded on the WHO 2019 research, building further evidence on art and culture’s contribution to health and well-being. The final project report by Zbranca et al. (2022) advocates for a policy change at all levels, to bridge existing (policy) silos between health, culture, education and social sectors.

Also at the international level, the multidimensional value of culture and the CCS in today’s societies has been highlighted in international fora. At Mondiacult 2022, the global conference dedicated to cultural policy and sustainable development, organised by the UNESCO, the closing declaration explicitly recognized culture as a driver of resilience, social inclusion and economic growth, impacting areas ranging from education, employment, health and emotional well-being to poverty reduction, gender equality, environmental sustainability, tourism, trade and transport (UNESCO, 2022). In the declaration, cultural ministers advocate for the systemic anchoring of culture into public policies across international, regional, national and local levels to ensure just transition.

However, despite this strong track record, there seems to be a lack of systemic EU strategy linking the CCS to social justice and well-being in Europe. There is no overarching EU framework positioning culture as part of the welfare state or social investment agenda (Zbranca et al., 2022). As a result, much cultural social innovation remains precarious, grant-dependent, and project-based.

3.4 Between promise and peripheralisation

Looking at EU policies and initiatives in past years related to the CCS and the triple transition, we can conclude that the CCS are increasingly invoked in EU rhetoric as enablers of the triple transition. In practice, however, their mobilisation remains partial and uneven.

The green transition has begun to integrate cultural narratives and practice but lacks systemic frameworks and deep engagement beyond architecture and design. The digital transition has recognised the CCS as an industrial ecosystem but struggles to position the CCS as core contributors to model alternative digital futures in Europe—open-source, community-based, ethically governed, address platform dependency and digital exclusion. The just transition has highlighted culture’s role in well-being and cohesion, but lacks a strategic anchor in education, inclusion and social innovation policy.

Strategic recognition of the role of the CCS as agents of change in the triple transition is thusly still far from established in EU policy, as also witnessed when screening the EU strategic agenda 2024–2029, which was adopted in June 2024 at the start of the new legislative period. The strategic agenda is structured around the following three pillars: (1) a free and democratic Europe, (2) a strong and secure Europe, and (3) a prosperous and competitive Europe. Except for an emphasis on the importance of free, secure and pluralistic media, the adopted strategic agenda makes no further reference to the role that the CCS can play in realising this strategic agenda (De Voldere et al., 2024). This discrepancy between promise and practice reflects deeper structural limitations in EU policy architecture.

4 Policy options for the future to empower the CCS in the triple transition

As the previous sections have shown, the CCS are increasingly recognised by EU institutions—at least in EU rhetoric—as having a key role to play in advancing Europe’s green, digital and just transition. Challenges such as the COVID-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine created momentum for several initiatives to tackle the fragile CCS and support their resilience. Yet, the systemic transformation of the CCS as agents of change in the EU’s triple transition is far from over. The CCS are currently insufficiently embedded in the core architecture of the EU’s policy frameworks to support the green, digital, and social transitions. Moreover, the CCS are also not fully equipped to take up this role, among others due to historical vulnerabilities in their working context.

Several policy options are needed to better equip and empower the CCS to serve as catalysts for the triple transition. Rather than approaching these transitions in isolation, their inherent interdependency cannot be neglected: ecological transformation cannot succeed without social inclusion; digital transformation must be human-centred, equitable and democratically grounded. The CCS are uniquely positioned to bridge these transitions due to their ability to foster imagination, dialogue, and inclusive participation, all critical elements in realising the triple transition. Yet, the CCS continue to face structural limitations at the level of EU policy. In this section, we draw on the interviews from the CULT Committee study (De Voldere et al., 2024) to identify policy options for mainstreaming the CCS into the heart of Europe’s transition agenda. The analysis of these interviews makes clear that continued policy efforts is needed in the coming years in multiple areas to further empower the CCS in playing that bridging role, for instance through strengthening their socio-economic resilience, investing in skills development, providing new ways of access to financing and funding, and creating more open innovation ecosystems for the CCS.

If the CCS are to contribute effectively to the triple transition, they must be supported not merely as vulnerable sectors deserving protection, but as strategic enablers of positive change. This requires a dual shift: first, strengthening the internal capacities of the CCS; second, structurally embedding them in the policy architectures of the triple transition.

4.1 Strengthening the cultural ecosystem: a precondition for engagement in the triple transition

Before CCS actors can fully engage with the challenges of climate change, digital transformation, or social justice, their working conditions, economic security and institutional capacities must be improved. Persistent fragilities remain in the sectors: high levels of precarity, project-based funding cycles, limited cross-border mobility and uneven access to infrastructure and life-long learning (De Voldere et al., 2024). These systemic deficits not only undermine individual resilience of people operating in the CCS but also weaken the sector’s collective ability to contribute meaningfully to any transition, let alone three. Below, we tackle five priority areas to strengthen the CCS’s internal capacities: (1) fair working conditions and social protection; (2) funding beyond project logic; (3) strengthening cross-sectoral collaboration; (4) infrastructure, skills and innovation ecosystems; and (5) governance reform and policy coherence.

4.1.1 Fair working conditions and social protection

The working conditions and fairness in the CCS should be (further) improved. More policy initiatives and measures are needed to help ensure that CCS actors have the security and rights needed to engage meaningfully in long-term change processes. Based on the study for the CULT Committee (De Voldere et al., 2024), we recommend that the EU and the Member States address systemic inequities to facilitate cultural workers to transition from operating at the margins of economic and social protection systems towards becoming stable contributors to broader transitional agendas. More specifically, we recommend the following:

• Supporting the implementation of a European framework for the Status of the Artist, thereby providing coordinated principles and benchmarks for fair remuneration, access to social rights and employment protections;

• Promoting national-level reforms that align with this framework and are sensitive to the needs of freelance, mobile and cross-border professionals.

4.1.2 Funding beyond project logic

Funding for the CCS in Europe remains dominated by short-term, project-based grants, often tied to narrow eligibility criteria and intensive administrative demands that inhibit continuity, collaboration and strategic risk-taking and innovation. To address this, we call for a shift from project-based to strategic funding in order to be more systemically involved in the long-term transformation processes the EU now prioritises. More concretely, the following (policy) actions seem necessary:

• Ensuring more long-term financial instruments that facilitate sustainable engagements or innovation and leverage the transformative role of the CCS;

• Simplifying administrative and financial procedures for financial instruments to better accommodate smaller CCS actors;

• Providing mentorship or training opportunities for CCS professionals to apply for funding;

• Further promoting other types of finance beyond public funding for culture and supporting the CCS in developing a diversified financing mix, exploring also other types of finance such as, e.g., crowdfunding, microloans, venture philanthropy, impact investing, etc. In that context, we refer to the work done in the EU-funded project Creative FLIP and the online ‘So You Need Money’ tool developed in this project.

4.1.3 Strengthening cross-sectoral collaboration

Aiming for just transitions and building ‘better futures’ depends on creating enabling environments for collaboration and open innovation, including between CCS and other sectors (e.g., health, education, environment, tech). However, many of the current innovation ecosystems lack openness towards including the CCS as agents of change for the triple transition (see, e.g., ekip). Recommended initiatives to promote more cross-sectoral collaboration include:

• Funding cross-sectoral transformation labs, where CCS actors can work alongside scientists, tech companies, urban planners, or educators on shared societal challenges;

• Fostering STEAM approaches in education and R&I programming to bridge science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics;

• Including CCS representatives in mission-oriented EU policy design, particularly within the EU Missions under Horizon Europe (e.g., climate-neutral cities, soil health, oceans).

4.1.4 Infrastructure, skills and innovation ecosystems

CCS engagement in the triple transition also seems to be hampered by uneven access to innovation infrastructures (including digital infrastructures) and transversal skills; gaps which are particularly severe in rural areas and within smaller organisations (e.g., Ranczakowska et al., 2024). Therefore, we recommend:

• Supporting access to digital and green infrastructure, including high-speed connectivity, digital platforms, energy-efficient buildings and sustainable production resources;

• Incentivising partnerships with higher education institutions and research organisations to develop CCS-tailored curricula and learning programmes that incorporate upskilling and reskilling focusing on the use of digital tools (AI, immersive media), green competencies (eco-design, circular practices) and skills for social innovation (co-creation, care work);

• Embedding CCS actors more structurally in research and innovation ecosystems, such as through consortia, innovation labs and specialisation platforms.

These investments are not only about technological adaptation, but about enabling the CCS to contribute proactively to broader innovation agendas that relate to the triple transition.

4.1.5 Governance reform and policy coherence

Cultural policy remains poorly integrated across EU governance structures, with siloed competences, limited inter-DG coordination and fragmented responsibilities between EU and Member State levels. To address this, the CULT Committee study (De Voldere et al., 2024) advocates for the following governance-level reforms for the CCS to be mainstreamed into EU’s most strategic policy agendas and programmes:

• Strengthening inter-DG cooperation—particularly between DG EAC, CLIMA, RTD, CNECT and REGIO—to align cultural priorities with climate, digital and regional development strategies;

• Supporting multi-level coordination platforms, involving national, regional and local authorities in co-developing cultural strategies aligned with the triple transition;

• Encouraging policy learning across Member States, with shared data frameworks and mutual exchange on policy innovation.

4.2 Leveraging the CCS as agents of change in the triple transition

Once the CCS are strengthened, the sectors can be more effectively and sustainably mobilised to drive and support the green, digital and just transitions. Below, we highlight what policy actions are needed to better activate the CCS across the three transitions.

4.2.1 The CCS in the green transition: from ‘communication tools’ to co-design

The green transition is often framed in rather technical or economic terms, but its success depends on cultural shifts: in values, lifestyles, aesthetics and imaginaries. CCS actors are powerfully positioned to catalyse such shifts, provided they are integrated structurally into climate policy frameworks. Based on the study for the CULT committee (De Voldere et al., 2024) and our policy work in the Horizon-project ekip, we call for:

• Embedding culture more systematically into the implementation of the European Green Deal, to fully harness the power of culture as a driver of change;

• Expanding the NEB beyond its current focus on architecture and design, to provide the right context for engaging also other cultural disciplines and community arts practices;

• Funding culture-based place-making and regeneration initiatives, particularly in marginalised or climate-vulnerable regions;

• Supporting CCS actors in greening their own operations, through carbon footprinting tools, mobility alternatives and energy transition plans;

• Encouraging partnerships between CCS and environmental knowledge or sciences, enabling joint storytelling (e.g., in theatre productions, art installations, music performances), scenario building and human-centred green innovations.

With these actions, the CCS are not simply positioned as ‘communicators’ in the last stage, but as actual co-designers of sustainable futures. The EC study Fostering Knowledge Valorisation through the Arts and Cultural Institutions (IDEA Consult, 2022) shows that artists and cultural organisations already collaborate with researchers and knowledge institutes at every stage of the knowledge chain—from framing research questions to prototyping low-carbon solutions—thanks to the unique set of competencies and activities that the CCS incorporate to bridge science and society.

4.2.2 The CCS in the digital transition: inclusion, sovereignty and ethics

Whereas the digital transition affects all sectors, there are particular complex implications for the CCS. On the one hand, CCS drive content, innovation and creativity in digital domains. On the other, they face increasing dependency on major online platforms, algorithmic control, and uneven access to digital infrastructures. To tackle this, the following policy options would centralise a human-centred digital transition in which the CCS do not merely adapt to technology, but help shape its direction and governance:

• Effective implementation of the DSA and DMA to protect cultural diversity and creator’s rights in platform environments;

• Supporting alternative digital platforms and infrastructures for culture, such as public, cooperative and open-source solutions that offer European digital sovereignty and respect European values as cultural diversity, pluralism and artistic freedom;

• Investing in digital skill development for CCS professionals, including literacy in AI, data protection, platform navigation and digital rights;

• Leveraging culture-tech collaboration, through artist residencies in tech firms, joint research projects and digital prototyping labs;

• Supporting access to digital infrastructure (broadband, servers, tools) for CCS actors in remote or underserved regions.

4.2.3 The CCS in the just transition: inclusion, engagement and care

The just transition seeks to ensure that no one is left behind in the face of ecological and technological change. Here, the CCS contribute not only to economic inclusion but to social cohesion, well-being and democracy. As mentioned before, the CCS are an indispensable pillar of this dimension. To further strengthen the CCS’s role in this transition, we propose in our study for the CULT Committee among others the following:

• Funding culture-based innovation projects in areas such as public health, education, migration, ageing and youth engagement;

• Embedding the CCS in place-based inclusion strategies, particularly in underserved urban and rural communities;

• Promoting inclusive governance within the CCS, ensuring that racialised, disabled, migrant and LGBTQ+ communities are represented in leadership, programming and funding

• Supporting the CCS in civic engagement and democracy-building, through arts-based civic education, counter-disinformation projects and community media initiatives.

An uptake of these policy options would position the CCS not just as a soft complement to social policy, but as crucial discursive and material vehicles of inclusion and cohesion. In that respect, cultural spaces—whether a rural creative hub, a virtual makers-forum or an urban mixed-reality lab—are crucial infrastructures through which a just transition can be lived rather than merely proclaimed. Cultural spaces can serve as safe environments for the CCS to interact with citizens and communities in the context of the green transition, well-being and societal innovation at large. In the CULT Committee study we refer to them as “critical nodes for artistic creation and community interaction,” while noting that the digital transformation comes with new types of digital cultural interaction spaces. Digital tools and platforms can further expand the reach of cultural activities and enable cultural creators to engage with communities in innovative ways, breaking down physical barriers. However, such digital interactions can only flourish when the access to digital cultural spaces is democratised and they are regulated well to prevent harmful behaviour such as cyberbullying or hate speech. It is of major importance that these spaces are designed to protect users’ privacy, provide digital and media literacy support, and ensure respectful interactions.

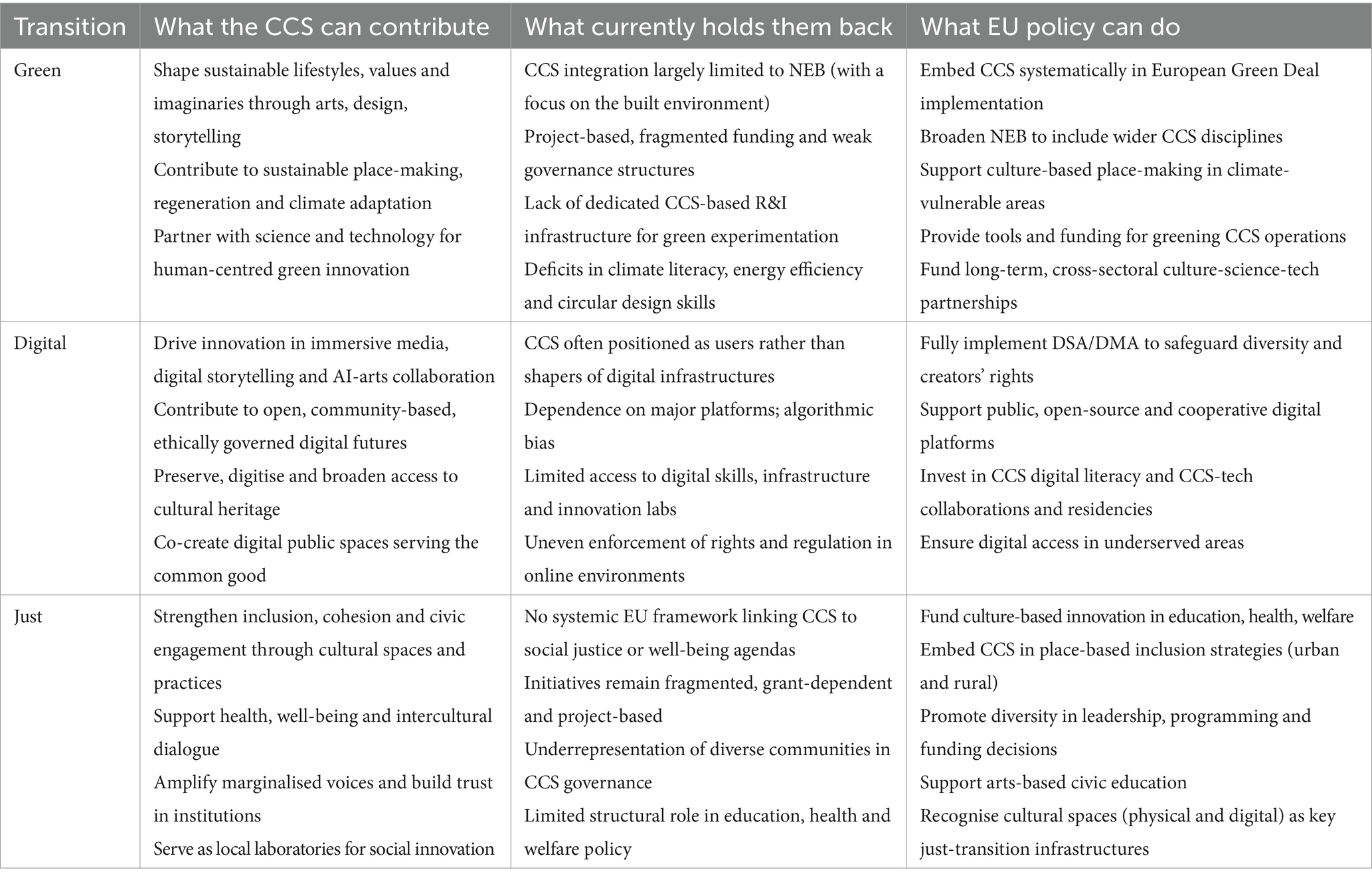

The preceding analysis and policy options have outlined how the CCS can be strengthened internally (section 4.1) and embedded more structurally in the EU’s triple transition (section 4.2). To conclude this section, Table 1 brings together the main insights from this article in a consolidated overview. It maps the (current and potential) roles of the CCS in the green, digital and just transitions, the main gaps and barriers that currently constrain their mobilisation, and the strategic policy recommendations set out in this section to address these challenges.

5 Discussion: the just transition as the soil for systemic change?

The notion of a triple transition—green, digital and just—marks a conceptual and strategic evolution in EU policymaking. Where once the green and digital transition were the primary axes of European transformation (the ‘twin transition’), increasingly the need for a more inclusive, participatory and socially just approach has surfaced. This turn, in our view, is not merely supplementary, nor is it a matter of ‘softening the edges’ of the other two transition domains. Rather, the just transition is the very soil upon which the other two can take root and flourish. Without justice, equity and public engagement, the green and digital transitions risk becoming exclusionary and siloed from societal changes.

It is precisely in this understanding that the CCS become not only relevant, but also structurally indispensable. As this policy review has shown, the CCS are uniquely positioned to shape meaning, provoke imagination and incite reflection. Through the policy recommendations—both in this article and in our study for the CULT Committee (De Voldere et al., 2024), we have called for repositioning the CCS as co-creators of Europe’s futures. However, to fully appreciate the urgency and value of this repositioning, we must situate it within the evolving architecture of the triple transition itself—an endeavour that we uptake in this closing discussion.

5.1 From dual to triple transition: why this strategic shift counts

Until recently, EU strategy framed systemic change largely through the lenses of the green and digital transitions. These priorities—taken up in the European Green Deal and the Digital Strategy—respond to complex challenges related to the climate crisis and the digital age. Yet, these transitions were often articulated in technical terms, oriented around emissions targets, digital infrastructures and economic competitiveness.

It was only in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic that the third dimension—social justice, inclusion and cohesion—was brought more explicitly to the fore. The pandemic made visible what had long been latent: that ‘resilience’ is not only a matter of environmental or technological adaption, but of social connectedness, trust in institutions and collective care. In this sense, the pandemic created momentum to underscore the need for a complex transformation that is not only efficient and sustainable, but also human-centred, inclusive and democratic.

By adding the just transition, the EU has shown its recognition that system-wide change can only be realised if it is also socially rooted and equitably distributed. Importantly, this third axis cannot be limited to technocratic policy interventions, but inherently implies a cultural shift in how transformation is imagined, governed and experienced. Here, the CCS offer unique and evident capacities, helping to give the transition a human aspect, a shared narrative, a democratic ground.

The CCS generate the material and discursive grounds that enable people to confront uncertainties, engage in anticipation and imagination, and stay connected across differences. During COVID-19, this role became very clear: from online concerts and participatory art projects in public space, to digital heritage platforms and community theatre. The CCS actors sustained and created social bonds, mental health, and a sense of belonging in times of profound disruption (see, e.g., IDEA Consult et al., 2021). In several countries, (e.g., UK, Bosnia and Herzegovina), arts and culture were able to effectively continue engaging with children and young people even during closure of schools thanks to newly established cross-sectoral collaborations between arts organisations, public broadcasters and the education sector (see, e.g., UNESCO Bosnia and Herzegovina Ministry of Culture, UNESCO, 2020). Arts and culture have also been a powerful medicine to combat psychological issues during the pandemic, as illustrated by the ‘Covid Living’ project and research. In this project, 14- to-24-year olds were invited to use photography, writing and other forms of artistic expression to document and express how they experienced the lockdown period (their feelings of loneliness, anxiety, etc.). The related research confirmed the relaxing effect of arts on the participants (Smith and Wolpert, 2020). The COVID-19 crisis thusly revealed not only the vulnerability of the CCS, but its value as a common good. If the green and digital transitions are to be successful, legitimate and inhabited, they must be necessarily underpinned by these cultural capacities.

5.2 Structural implications of the triple transition: the CCS as an enabler, not a tool

The triple transition logic has important structural consequences for EU policymaking. It means that the CCS cannot be treated as instrumental appendices, intermittently called in to ‘raise awareness’, ‘make something creative’, or ‘communicate change’ once all the real work has been done. Instead, it necessarily implies an integration of culture into the design, governance and implementation of transition strategies from the outset.

Therefore, our recommendations call for including culture in the heart of the transition policies: i.e. not just through dedicated programmes like Creative Europe or the New European Bauhaus, but also across climate missions, innovation platforms, digital regulation and investment mechanisms. This requires a shift from short-term project funding towards more structural and sustainable funding and partnerships. CCS actors should be encouraged to build long-term collaborations with local and regional authorities, EU R&I platforms, cross-national networks (e.g., ENCC, Culture Action Europe, 2022) and educational institutions, as these stable partners can act as bridges between culture, innovation/creativity and broader transition strategies. It also requires a shift in broader governance: how transition is defined, who participates in shaping it and what kinds of knowledge and experience are acknowledged as legitimate. Necessarily, it means treating artists, cultural organisations and creative workers not just as stakeholders to be consulted, but as co-owners and -drivers of positive change in Europe.

Also from a broader, democratic logic this makes sense and creates a sense of urgency. Across Europe, trust in institutions seems to become increasingly fragile, participation in formal politics is declining and polarisation is growing (Ahrendt et al., 2025; Eurobarometer, 2023). In such a context of uncertainty, transitions are not just a matter of ‘delivering’ but of severe co-creation that builds on collective agency and a shared sense of urgency. It is almost redundant to say that the CCS, as platforms for expression, experimentation, negotiation and dissent, have a crucial role to play in this. They offer space for marginalised voices and histories, and have a major storytelling, imagination, and awareness-creating power. This is what it means to say that the just transition is the soil of the dual transition, as it is the living ground on which democratic, imaginative and human-scale transitions can grow.

5.3 Opening up the transition and future directions

The integration of the CCS as agents of change in the triple transition comes with complex challenges. It requires, amongst others, new metrics of value and monitoring, new cross-sectoral ties, collaborations and even discourses, and fresh institutional configurations. In these ‘post-normal’ times with high levels of complexity, contradiction and chaos (Sardar, 2010), it inevitably also raises questions about power: whose voice is being heard, whose stories are being told, whose imagined futures are being heard and who benefits from which transformation.

While extremely complex in nature, these are precisely the questions that the CCS are equipped to raise and tackle, from a critical, reflexive and inclusive stance. Rather than seeking to neutralise, evade or manage these tensions, EU policy should embrace the CCS as key constitutive elements of its democratic raison d’être. For, a ‘just’ transition does not have to be synonymous to a smooth transition; it may be well contested, negotiated and resisted, and history has shown that culture is where hegemonic and counter-hegemonic discourses become visible and meaningful.

As the EU has moved into its 2024–2029 parliamentary term, it must recognise that the triple transition is not just a policy framework, but a democratic project through and through; a project that demands new infrastructures, not only of energy or data platforms, but also of imagination, well-being and belonging. The CCS can support building these necessary material and discursive infrastructures. The 2024–2029 parliamentary term presents a critical chance for the EU to move the CCS from marginalisation to mainstreaming, from symbolic inclusion to structural integration.

Author contributions

ED: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Resources, Validation. ID: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Data curation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The article is based on funded research for the CULT Committee of the European Parliament: “EU culture and creative sectors policy – overview and future perspectives” (De Voldere et al., 2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge that this article builds further on collective work carried out in the framework of the European Parliament study “EU culture and creative sectors policy: Overview and future perspectives” (De Voldere et al., 2024). We are grateful to our co-authors of that study—Heritiana Ranaivoson, Marlen Komorowski, Tille Peters, Sylvia Amann, Joost Heinsius, Aleksandra Kuczerawy and Jozefien Vanherpe—for the crucial contributions that they made to the study. The authors also wish to thank the different interviewees and stakeholders who generously shared their insights during the study. Their collective contributions provided an essential foundation for the reflections and analysis developed further in this article.

Conflict of interest

ED and ID are employed by IDEA Consult, a private, independent research bureau that performs policy studies and closely collaborates with academic partners. The study on which this article builds has been done in partnership with two academic institutions (VUB and KULeuven).

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, generative AI was used solely to assist language refinement and formatting of summary materials. All intellectual content, analysis, reflections and conclusions are the authors' own, and the authors take full responsibility for the final text.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahrendt, D., Sándor, E., Chédorge-Farnier, D., and Schulte-Brochterbeck, L. (2025). Quality of life in the EU in 2024: results from the living and working in the EU e-survey. Eurofound. Available online at: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/resources/data-story/2025/quality-life-eu-2024-results-living-and-working-eu-e-survey (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Amara, R., and Lipinski, A. J. (1983). Business planning for an uncertain future: Scenarios & strategies. New York: Pergamon.

Council of the European Union (2022). Council Conclusions on building a European Strategy for the Cultural and Creative Industries Ecosystem (2022/C 160/06). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=oj:JOC_2022_160_R_0006 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Culture Action Europe (2022). The EU Commission assesses the current work plan for culture. Available online at: https://cultureactioneurope.org/news/https-eur-lex-europa-eu-legal-content-en-txt-uricom2022317fin/ (Accessed September 8, 2025).

De Voldere, I., De Smedt, E., Peters, T., Ranaivoson, H., Komorowski, M., Amann, S., et al. (2024). EU culture and creative sectors policy – overview and future perspectives. Research for CULT Committee. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2024)752453 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

DMA. (2022). Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (digital markets act) (text with EEA relevance).

DSA. (2022). Regulation (EU) 2022/2065 of the European Parliament and of the council of 19 October 2022 on a single market for digital services and amending directive 2000/31/EC (digital services act) (text with EEA relevance).

Dutkiewicz, L., Krack, N., Kuczerawy, A., and Valcke, P. (2024). “AI and media” in Cambridge handbook on the law, ethics and policy of artificial intelligence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Ekip—European Cultural and Creative Industries Innovation Policy Platform (2024). Policy Lab 2 – Cultural and Creative Industries enabling green transitions: Is the New European Bauhaus a catalyst? Report and policy recommendations. Available online at: https://ekipengine.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/ekip_NEB-Policy-recommendations_FINAL.pdf (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Eurobarometer (2023). Flash Eurobarometer 522: Democracy Report. Survey conducted by Ipsos European Public Affairs at the request of the European Commission, Secretariat-General. March 2023. Available online at: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2966 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2007). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on a European Agenda for Culture in a Globalizing World. COM/2007/242 final. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2007:0242:FIN:EN:PDF (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2018). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the Regions: A new European agenda for culture. COM/2018/267 final. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0267 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2020a). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the Regions: A new industrial strategy for Europe. COM/2020/102 final. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0102 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2020b). Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the Regions: Updating the 2020 new industrial strategy: Building a stronger single market for Europe’s recovery. COM/2021/350 final. Available online at: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/9ab0244c-6ca3-4b11-bef9-422c7eb34f39_en?filename=communication-industrial-strategy-update-2020_en.pdf&prefLang=nl (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2021). Annual single market report 2021 accompanying the communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the Committee of the Regions Updating the 2020 new industrial strategy: Building a stronger single market for Europe's recovery. SWD/2021/351 final. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021SC0351 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Commission (2022). Directorate-general for education, youth, sport and culture, stormy times – Nature and humans – Cultural courage for change – 11 messages for and from Europe, publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission. (2023). Strategic Foresight Report 2023: Sustainability and People’s Wellbeing at the Heart of Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture (2017). How culture and the arts can promote intercultural dialogue in the context of the migratory and refugee crisis: report with case studies, by the working group of EU Member States’ experts on intercultural dialogue in the context of the migratory and refugee crisis under the open method of coordination. Publications Office.

European Parliament (2022). European Parliament resolution of 14 September 2022 on the new European Bauhaus (2021/2255(INI)). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022IP0319&qid=1712278946217 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

European Parliament (2023). European Parliament resolution of 21 November 2023 with recommendations to the commission on an EU framework for the social and professional situation of artists and workers in the cultural and creative sectors (2023/2051(INL)). Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/C/2024/4208/oj/eng (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Fancourt, D., and Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. In Health evidence network synthesis report 67. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/sites/default/files/9789289054553-eng.pdf (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Hausemer, P., Richer, C., Klebba, M., and Amann, S. (2021). Skills, needs and gaps in the CCSI. Creative FLIP final report, work package 2 on learning. Available online at: https://oldflip.creativehubs.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FINAL-WP2_Final-Report-on-Skills-mismatch-2.pdf (Accessed September 8, 2025).

IDEA Consult (2022). Research for EC-DG RTD—fostering knowledge valorisation through the arts and cultural institutions. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

IDEA Consult and Technopolis Group (2023). Research for EC- European innovation council and SMEs executive agency - monitoring the twin transition of industrial ecosystems: CULTURAL AND CREATIVE INDUSTRIES - analytical report. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

IDEA Consult, Goethe-InstitutAmann, S., and Heinsius, J. (2021). Research for CULT committee – Cultural and creative sectors in post-Covid-19 Europe: Crisis effects and policy recommendations, European Parliament, policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2021)652242 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight 10, 4–21. doi: 10.1108/14636680810855991

Jacobides, M. G., and Lianos, I. (2021). Regulating platforms and ecosystems: an introduction. Ind. Corp. Chang. 30, 1131–1142. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtab060

Matti, C., Jensen, K., Bontoux, L., Goran, P., Pistocchi, A., and Salvi, M. (2023). Towards a fair and sustainable Europe 2025: Social and economic choices in sustainability transitions. Joint Research Centre. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. Available online at: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133716 (Accessed September 8, 2025).

Muench, S., Stoermer, E., Jensen, K., Asikainen, T., Salvi, M., and Scapolo, F. (2022). Towards a green and digital future. Joint Research Centre. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.