- College of Communication and Media Sciences, Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

This study investigates journalistic interventionism within the diverse media landscape of the Global South. Journalism in these regions sometimes takes an interventionist approach. Understanding this approach necessitates moving beyond Western-centric paradigms that may overlook Global South media’s distinctive historical, political, economic, and sociocultural circumstances. The primary objective of this research is to understand the manifestation of the interventionist journalistic role performance across various Global South countries, examining its overall prominence and the influential factors that affect interventionist role deployment. The study examines interventionist journalism in 16 Global South nations using quantitative content analysis of 59,391 news items from 153 media outlets based on the operationalization framework to measure journalistic role performance within news content. The findings reveal a regional pattern in journalistic role performance, with Latin American journalism displaying a more interventionist orientation. The results further showed a significant negative relationship between sociopolitical constraint and interventionist journalistic role performance, suggesting that levels of interventionist journalism decrease as sociopolitical constraints increase. Results also illuminate how national contexts, economic development levels, and political and press freedom influence interventionist journalistic role performance. These findings have significant implications for media organizations and policymakers, highlighting the need for adaptive strategies considering how organizational and contextual factors shape interventionist-driven journalistic practices.

1 Introduction

Contemplating the functioning of journalism in the Global South is particularly intriguing, as it diverges from practices observed in other regions of the world. Concepts of journalism originating from regions commonly referred to as the Global North do not invariably align with local contexts due to varied histories, cultures, and societal structures.

A significant distinction is that journalism in the Global South frequently sees its function as facilitating national development. Journalists may perceive a necessity to engage in improvement efforts, rather than merely observing from afar or expressing a critical posture. This approach differs from being a neutral observer, as Kalyango et al. (2016) argued.

Nevertheless, adopting this “interventionist” approach poses challenges for journalists. They encounter obstacles due to the structural organization of media entities, the level of media development in their nation, and the prevailing political and economic conditions in which they operate. These circumstances also raise ethical questions regarding the appropriate conduct of journalists (Mellado et al., 2024).

It is equally crucial to acknowledge that history and culture significantly influence performance. The interaction between journalism and religious views varies significantly throughout different regions of the Global South (Kalyango et al., 2016). Complexities may arise when media entities from the Global North endeavor to support journalism in the Global South. Occasionally, such assistance can inadvertently influence the perceptions of journalists in the Global South on their profession, even through mechanisms such as financial backing or cultural concepts (Tietaah et al., 2018). This underscores the necessity of being attuned to local circumstances and perspectives while trying to help the media in these areas.

Moreover, the practices employed to combat misinformation in Western nations may prove ineffective in the Global South. This occurs due to individuals utilizing various social media platforms, the dissemination of rumors across diverse networks, and the distinct methods by which information is typically shared. The emergence of networked societies and transnational networks alters journalists’ perceptions of their duties, particularly when they engage across borders (Badrinathan and Chauchard, 2024).

To comprehend journalism in the Global South, one must consider the distinct historical, political, and cultural contexts that influence its practice. Journalism goes beyond simply fact-reporting; it is intertwined with societal power dynamics and current perceptions and ideologies. Journalism can be regarded as a political activity (Mellado et al., 2024; McIntyre and Cohen, 2022).

The role of journalism extends beyond merely reporting events; it encompasses facilitating dialogue between the powerful, the marginalized, and those with limited influence (Aryal and Bharti, 2022) Journalism in the Global South fundamentally involves facilitating dialogues among the powerful, the powerless, and all intermediaries (Aryal and Bharti, 2022). The proactive endeavor to effect change distinguishes interventionist journalism from just event reporting. Journalists, whether attempting to influence directly or indirectly, generally aim to lead to change. Given the significant influence of media on public perception and knowledge, interventionist journalism can serve as a powerful tool for social or political transformation. The practical implications are not only a matter of different worldviews, but also extend to each region’s distinct political, economic, and social contexts (Muchtar et al., 2017). The efficacy of journalism as a watchdog is significantly influenced by the type of government and the extent of press freedom. When engaging with the media of the Global South, it is essential to be flexible and consider local perspectives to prevent inadvertently harming social relationships.

2 Global South media: diversity, challenges, and dynamics

Examining how countries organize their media helps us understand how it works and what it does in various societies and cultures. The influential framework by Hallin and Mancini (2004) primarily examined media in Western countries like the US and Western Europe. This means it might not fully explain how media operate elsewhere. Scholars like Waisbord (2013) argued that this Western perspective often misses the unique ways media function in non-Western countries and the important social and cultural factors. Their main suggestion is that we need to “de-westernize” how we think about media (Shen, 2012).

Hallin and Mancini (2004) focused on factors like newspaper history, how closely media and politics are linked, the professionalism of journalists, and government control over media. Other scholars like Blum (2014) proposed different categories based on media freedom and political parallelism to identify a range of media systems from liberal to controlled. However, the accuracy of these categories might not always fit well when applied to countries outside the Western world and require careful, context-specific consideration (Richter and Kozman, 2021, 18).

Media in non-Western countries are shaped by their unique histories, political structures, economies, and cultures, which often differ significantly from those in the West. Trying to understand these media systems solely through a Western lens overlooks the real picture and the challenges these media face. Much of the research has historically focused on Western liberal-democratic principles and has not adequately explored the meaning of journalism and the roles of journalists in non-Western communities (Ekdale et al., 2022). In these settings, values like community, personal relationships, and social harmony might be more influential in shaping journalism than Western ideals of individualism and adversarial reporting. Historically, research has examined chiefly Western democracies, leading to less understanding of media in less developed democracies (McIntyre and Cohen, 2022). It is crucial to recognize that Western media models may not directly apply because non-Western media often operate under different constraints and needs (Iyengar and McGragy, 2007). Non-Western countries are actively changing global journalism by incorporating their local narratives and adapting to specific situations (McIntyre and Cohen, 2022).

2.1 The Global South: a conceptual framework for journalism studies

The term “Global South” is not merely a geographical designation but a crucial conceptual framework across various academic disciplines, including geography, politics, and culture. It encompasses Latin America, Asia, Africa, and Oceania. Challenges like lower incomes, poverty, inadequate housing, limited education, and deficient health systems often characterize these countries. Beyond being a metaphor for underdevelopment, it reflects a shared history of colonialism, neo-imperialism, and socioeconomic changes that have led to lasting disparities and political/cultural marginalization (Wasserman, 2006). For journalism studies, the “Global South” highlights regions linked by shared colonial legacies, structural peripherality, and a common desire to reform global governance institutions (Moyo, 2022; Bull and Banik, 2025).

Many countries in the Global South contend with fragile or highly contested democratic systems, entrenched inequalities, and authoritarian tendencies, where democratic legitimacy is often a crucial basis of rule for leaders. State intervention in media systems is a common challenge, with journalists facing issues ranging from censorship to violence, and a completely free press system remains a long-term goal (Hallin and Papathanassopoulos, 2002).

In the Global South, structural factors and institutional considerations present fundamental practical challenges to individual motivation and the ability to report and publish news content (Prado, 2017). Several Latin American countries have experienced political upheaval, coups, dictatorships, and financial crises that have impacted media markets (Weiss, 2015). They often feature a mix of government-owned and private media, with major media players controlling significant content. Political clientelism, where media systems reflect political makeup, is a notable characteristic. Violence against journalists, issues with access to information, and media censorship are pervasive. Research findings showed that interpretive and populist mobilizer roles resonate most strongly among journalists in Latin American countries. Mexican journalists, for example, identify strongly with the populist mobilizer role, seeking to engage the public and impact change, which may be linked to the country’s turbulent past and challenges to press freedom. Brazilian journalists primarily perceive themselves in an interpretive role, acting as watchdogs for their communities (Hallin and Papathanassopoulos, 2002; Weiss, 2015).

Populist authoritarian regimes in African and Middle Eastern countries may also co-opt anti-colonial language while suppressing dissent and shrinking democratic space. Journalists are viewed as central to national unity and identity. Because most news content is outsourced from Western countries, African journalists often find themselves secondary in narrative shaping. This “othering” of local knowledge and voices, even by local journalists, is a critical aspect of role performance shaped by colonial legacies (Wahutu et al., 2023; Bull and Banik, 2025). These political realities often compel journalists to operate under specific ideologies that influence their daily routines, such as holding officials accountable or interpreting news rather than merely disseminating information (Vinhas and Bastos, 2025).

To understand media in the Global South, we must move beyond Western-centric models and adopt more inclusive approaches, considering the national context. The growth of media in Asian countries, for instance, provides valuable insights into media changes in a digital world. However, many Asian nations rely on Western news for international reporting, potentially limiting intercultural communication and media exchange (Mutsvairo et al., 2021). Technology and globalization have made the media landscape more dynamic. In many non-Western countries, governments often have significant control over the media, which can affect independent and critical reporting. Journalism has historically been taught and viewed through a “universal Western perspective,” considered a “global standard” that confers status. Journalists in the Global South are often trained to follow this “correct method” (Mutsvairo et al., 2021). There’s a growing recognition of the need to “decolonize” journalism studies and create frameworks more relevant to non-Western realities. Examining the historical, cultural, and political factors that shape media in these regions is essential.

Furthermore, economic circumstances in non-Western nations significantly affect their media systems; limited resources and infrastructure can hinder media development and sustainability. The rise of digital and social media has created new avenues for citizen journalism and diverse voices in these countries. The internet has enabled these media to reach global audiences. The traditional dominance of Western media is being challenged by more varied and complex information flows (Thussu, 2013).

The media landscape in the Global South is complex and dynamic, requiring nuanced analysis beyond simple “free” or “unfree” categorizations. It ranges from complete media capture by authoritarian regimes to semi-liberal environments with varying degrees of autonomy and challenges (Humprecht et al., 2022). This diversity arises from a complex interplay of historical, political, economic, and socio-cultural factors unique to each nation. Many countries face turmoil and instability, exacerbated by media concentration, capture, violence against journalists, and the political use of journalism, limiting access to information (Mutsvairo et al., 2021). Western ideas about press freedom and the press’s watchdog role often do not fully fit the realities of these societies, where power dynamics differ. Media systems in the Global South are also shaped by colonialism, Cold War alliances, and digital technologies (Semujju, 2020; Echeverria et al., 2022).

“Media capture,” where powerful individuals or groups intentionally influence media for political or economic gain, is a major concern in many parts of the Global South (Chadha, 2017). This can involve political elites owning media, state advertising favoring pro-government media, and using laws to silence critics (Nielsen, 2017). This issue is often rooted in the colonial past, where the media served colonial or post-colonial state interests. Media capture seriously undermines public trust, limits viewpoints, and hinders democracy (Atal, 2017). However, the extent and nature of media capture vary across countries. While some have near-total state control, others have a mix of independent and state/partisan media (Atal, 2017). Economic liberalization has also led to “corporate capture” by powerful moguls (Nielsen, 2017). Even with significant capture, journalists often resist censorship. Digital and social media have created new avenues for citizen journalism and diverse narratives, challenging traditional media dominance. However, they also bring challenges like misinformation, hate speech, and weakened journalistic standards. Governments sometimes extend censorship through social media regulation or surveillance (Atal, 2017).

Understanding journalistic practices in the Global South requires a nuanced, context-sensitive approach considering diverse ownership, varying freedom, and complex political, economic, and socio-cultural factors. States often use ownership, financial, legal, and cognitive strategies to capture news media for political survival, with varying levels of directness (Zirugo, 2025). Political and economic interests, especially in fragile democracies, complicate the media landscape. Corporate capture is a growing concern, potentially suppressing investigative journalism and favoring business interests over the public good. The pursuit of profit can lead to lower-quality news (Márquez-Ramírez and Guerrero, 2017). Despite these challenges, many Global South countries have vibrant independent media that hold power accountable, often operating in precarious conditions.

3 Mapping interventionist journalistic role globally

Research on interventionist journalism in various contexts indicates its greater prominence in public media organizations and countries with restricted political freedom (Hanitzsch et al., 2016). It is also observed in democracies with partisan and opinion-oriented journalistic cultures or during sociopolitical crises (Márquez-Ramírez et al., 2019).

Interventionist journalism is also scholarly and addressed from an advocacy and social change perspective. Journalists legitimize interventionism by emphasizing the mission of journalism to give voice to underrepresented groups and ideas. Advocacy interventionism is normalized, while partisan activism is generally rejected (Shultziner, 2025). Furthermore, interventionism is seen in the context of humanitarian intervention, where journalists are encouraged to deconstruct structural causes of political violence and play a proactive role (Shaw, 2012).

Interventionism varies significantly across countries. Central and Northern European countries exhibit higher content-driven interventionism levels than Southern European countries (Pagiotti et al., 2024). In Spain, journalistic practices are characterized by an interventionist profile, with a high presence of the watchdog role and a conceptualization of the audience as citizens (Humanes and Roses, 2018). Utilizing a practice-oriented view of journalistic interventionism, a study uncovered that Finnish journalists negotiate their professional ethos amidst financial pressures and heightened competition, which questions objectivity and nonpartisan neutrality (Reunanen and Koljonen, 2016).

As another form of Interventionism, one study revealed that Journalists actively contribute to conflict frame building by using exaggerated language and amplifying political conflicts. This interventionist stance is often facilitated by media routines embedded in organizational practices (Bartholomé et al. 2015).

Understanding journalistic interventionism across different media systems requires a nuanced framework that connects its diverse dimensions and allows for more sophisticated analysis. Shultziner’s (2025) comprehensive model is particularly valuable because it distinguishes journalistic interventionism from related concepts such as media bias or advocacy, thereby clarifying the core subject for readers. Fundamentally, interventionism entails a conscious departure from the norms of objective journalism, driven by an intentional effort to advance specific causes or agendas. Crucially, the various forms of interventionism are interconnected rather than isolated—each can reinforce the others in practice, collectively constituting a broader, dynamic phenomenon (Shultziner, 2025). This integrated perspective provides deeper insight into how journalists navigate the complexities of their professional roles while pursuing ideological or social objectives.

Building on this model, it is essential to explore the motivations, justifications, and ethical considerations that underpin each form of interventionism. These include potential consequences for public trust, journalistic credibility, and the broader perception of media integrity (Shultziner, 2025). A balanced perspective should acknowledge both the empowering aspects of interventionist journalism—such as promoting accountability and catalyzing social change—and the potential pitfalls, including bias, manipulation, and erosion of journalistic standards.

Advocacy journalism, where reporters intentionally include their opinions or biases in their news stories, is a key area of interventionism. They might do this subtly by choosing certain words, framing the story in a specific way, or picking sources supporting their view to sway the public’s thoughts (Cox et al., 2024). As this becomes more common, it makes us question what the role of a journalist is today. Is it still to be purely objective, or is it okay to be more involved and present their point of view? (Shultziner, 2025). However, when journalists become advocates, it can be hard to tell where reporting ends and activism begins, and we need to think carefully about the ethics of that.

Similarly, agenda-setting is pivotal in shaping public discourse and influencing policy decisions. Within this framework, journalists strategically prioritize specific issues, often through repetition, framing, and using sources to make them seem more significant (Shultziner, 2025). While agenda-setting can serve the public interest, it may also distort reality, stressing select topics while neglecting others, thus compromising informed decision-making (Entman, 2007; Baleria, 2021, p. 70).

“Driving action” is another form of interventionism where journalists actively try to get people to participate in civic or political life. While getting people involved can be good, it can also make journalists seem less neutral. If journalists use their platforms to promote specific actions or political results, especially on social media, it becomes harder to see the difference between reporting and campaigning. This can make the public lose trust in their reporting and wonder if they have a hidden agenda (Cushion et al., 2012; Shultziner, 2025).

In order to investigate journalistic cultures, researchers proposed to focus on five main dimensions: socio-labor conditions, production methodologies, media relationships with companies and government, functions of journalistic information, and its use by citizens (Gómez-Diago, 2018). To fully grasp the implications of journalistic interventionism, it is essential to consider how cultural and societal values shape these practices. Hanitzsch (2007) considers that interventionism, power distance, market orientation, objectivism, empiricism, relativism, and idealism are the dimensions to deeply understand the complexity of journalism culture and typology. Research also indicated that journalists prioritizing values like power, tradition, or achievement are more likely to be interventionist (Hanitzsch et al., 2016). In some contexts, journalists may act as “populist mobilizers,” shaping media agendas and encouraging public debate, depending on the characteristics of the media landscape (Degen et al., 2024). The level of interventionism is influenced by factors such as the perceived urgency of an issue, the journalist’s social identity, and the broader departure from normative journalistic standards (Shultziner, 2025).

Given the growing complexity of the media environment and the increasingly blurred lines between traditional journalism and activism, interventionist practices are becoming more common (Shultziner, 2025). Addressing their ethical implications requires a robust analytical framework considering diverse perspectives and potential outcomes. As Waisbord (2013) argues, interventionism challenges the foundational principles of objectivity and impartiality that have long underpinned journalistic practice. The widespread adoption of advocacy journalism calls for a reassessment of the journalist’s societal role and the potential erosion of public trust in media institutions. Economic pressures, especially on local news outlets, further drive this shift as journalists turn to interventionist strategies to attract audiences and remain relevant. Ultimately, it is vital to critically assess the long-term effects of these trends on the quality, trustworthiness, and democratic function of journalism.

3.1 Interventionist journalistic role indicators in Global South nations

In his early study, Hanitzsch (2007) noted that interventionist journalism involves active participation in events to promote change, rather than maintaining a detached stance. Building on this Mellado (2015, 2020a, 2020b) have, over the past decade, influentially conceptualized the interventionist dimension of journalistic role performance as the degree to which a journalist’s voice is embedded in the construction of a news story, whether through content-driven or style-driven interventionism. It is crucial to understand how journalists influence narratives beyond simply reporting facts. Accordingly, the interventionist role becomes more prominent as the journalist increasingly shapes the message by expressing opinion, advocating or demanding change, and offering interpretations of events (Mellado et al., 2017). Additional indicators of this dimension include qualifying adjectives that reflect subjective judgments and the employment of first-person language, such as “I” or “we,” which personalizes the narrative and reinforces the journalist’s presence within the story. Mellado (2020a) emphasize that interventionism does not exist in isolation but interacts dynamically with other role performance dimensions in journalistic practice. Previous research argues that the level of intervention is directly proportional to the visibility of these features: the more a journalist uses opinion, interpretation, and stylistic markers like adjectives and first-person pronouns, the stronger the interventionist stance becomes, and vice versa. This framework provides a valuable lens for analyzing how journalistic roles evolve in response to professional, cultural, and institutional pressures, particularly in contexts where traditional norms of objectivity are being renegotiated.

Research conducted in some countries belonging to the Global South showed that the interventionist role is a complex phenomenon shaped by each country’s unique political, social, and historical contexts. While sharing some common ground, it manifests differently across various countries and media systems. In Ethiopia, State media predominantly performs interventionist roles by using strategies like inclusive language (“we”) to promote national unity (Skjerdal, 2024).

In Rwanda, Journalists prioritize roles that support official policies for development and convey a positive image of leadership, fitting the understanding of development journalism and a desire to rebuild and unite after the genocide. Criticizing the government is widely perceived as being of the least importance. While in Uganda, journalists embrace a more interventionist reporting style; they also value traditional information dissemination to blend Western and African values. In a less restrictive political system, Kenyan journalists find serving as a critic of the government more important than in Rwanda and Uganda, indicating a greater ability to embrace adversarial duties. They have also grappled with the ethics of objective reporting in conflict situations (McIntyre and Cohen, 2022).

Given the multilevel nature of the news creation process, further research is needed to examine the interaction between system-level factors, institutional factors and news-practice-related variables to understand better the variations in journalistic role performance across different societies, sociopolitical systems, and media environments (Kozman and Liu, 2024; Mellado et al., 2024).

This study seeks to fill the gap in understanding the dynamics of interventionist journalistic role performance and the factors affecting it within media practice in the Global South. The purpose of this research is to gain a better understanding of the interventionist journalistic role performance in media outlets by identifying the key factors that may be significantly associated with interventionist journalistic role performance and exploring the most effective factors influencing this role within Global South countries, focusing on identifying the strongest predictors among content-related, organizational, and socio-political contextual factors. Additionally, we attempt to clarify how the complex interaction between such factors shapes interventionist role performance in non-Western countries and helps media organizations adopt news production strategies to improve news performance and delivery.

4 Research questions and hypothesis

The main aim of this study is to understand the manifestation of the interventionist journalistic role performance across various Global South countries, examining its overall prominence and the influential factors that affect interventionist role deployment.

RQ1: How prominent are the interventionist journalistic role and its key sub-indicators in the selected Global South countries?

RQ2: How do news practices (content-related variables) and organizational variables (media outlets-related variables) influence the prominence of interventionist journalistic role performance?

RQ3: Which factors, among content-related, organizational, and socio-political contextual factors, most effectively predict the interventionist journalistic role in news content across the 16 countries?

Prior scholarship has demonstrated that sociopolitical context is pivotal in shaping journalistic role performance. Hallin and Mancini (2004) argued that a country’s political and social context profoundly influences a country’s media system, and the roles journalists perform. In systems characterized by high state control, limited press freedom, or significant economic constraints, journalists may be compelled to adhere to a more neutral or passive role to avoid repercussions such as censorship, legal action, or physical harm. A cross-national study found significant variation in interventionism at the individual, organizational, and societal levels. The authors concluded that journalists were more willing to practice an interventionist role when working in public media organizations and countries with restricted political freedom (Hanitzsch et al., 2016). Mellado et al. (2023) found significant country-specific differences in the performance of the interventionist role, with journalists in countries with greater media freedom tending to adopt a more interventionist approach. However, a recent comparative study showed that although the expression of an interventionist role is shaped by broader political, economic, and organizational factors, this relationship is not always linear (Mellado et al., 2024). In transitional and non-democratic countries, Márquez-Ramírez et al. (2019) found that restricted press environments often foster a hybrid role performance where interventionist and watchdog roles overlap. Under such political contexts, journalists face pressures to engage in more overtly opinionated or advocacy-based coverage (Márquez-Ramírez and Guerrero, 2017). Drawing on the preceding scholarly literature, we hypothesize that:

H1: Higher levels of sociopolitical constraint, reflected in lower degrees of freedom, are negatively associated with interventionist journalistic role performance.

5 Methods

This study employed a quantitative content analysis based on the operationalization framework to measure journalistic role performance within news content. The analysis was conducted to examine the dynamics shaping the interventionist journalistic role within Global South media, focusing on identifying key factors significantly associated with interventionist role performance and the interaction of these factors in producing interventionist content. Variations in interventionist journalistic role performance can be attributed to multiple measurable factors at both organizational and societal levels. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to explore the interaction of three types of factors: content-related factors, organizational factors, and sociopolitical contextual factors. At the first level, content-related variables include media type, story type, story format, story placement, story theme, geographic frame, number of news sources, diversity of these sources, and diversity of sources’ viewpoints. Organizational factors include media outlet size, media ownership, media chain structure, media newsroom convergence, media political orientation, media political alignment, and media-codified editorial rules. Finally, sociopolitical contextual variables include country of publication, Freedom House global freedom status, Economic Freedom Index (market orientation), the RSF Press Freedom Index score, and GDP per capita.

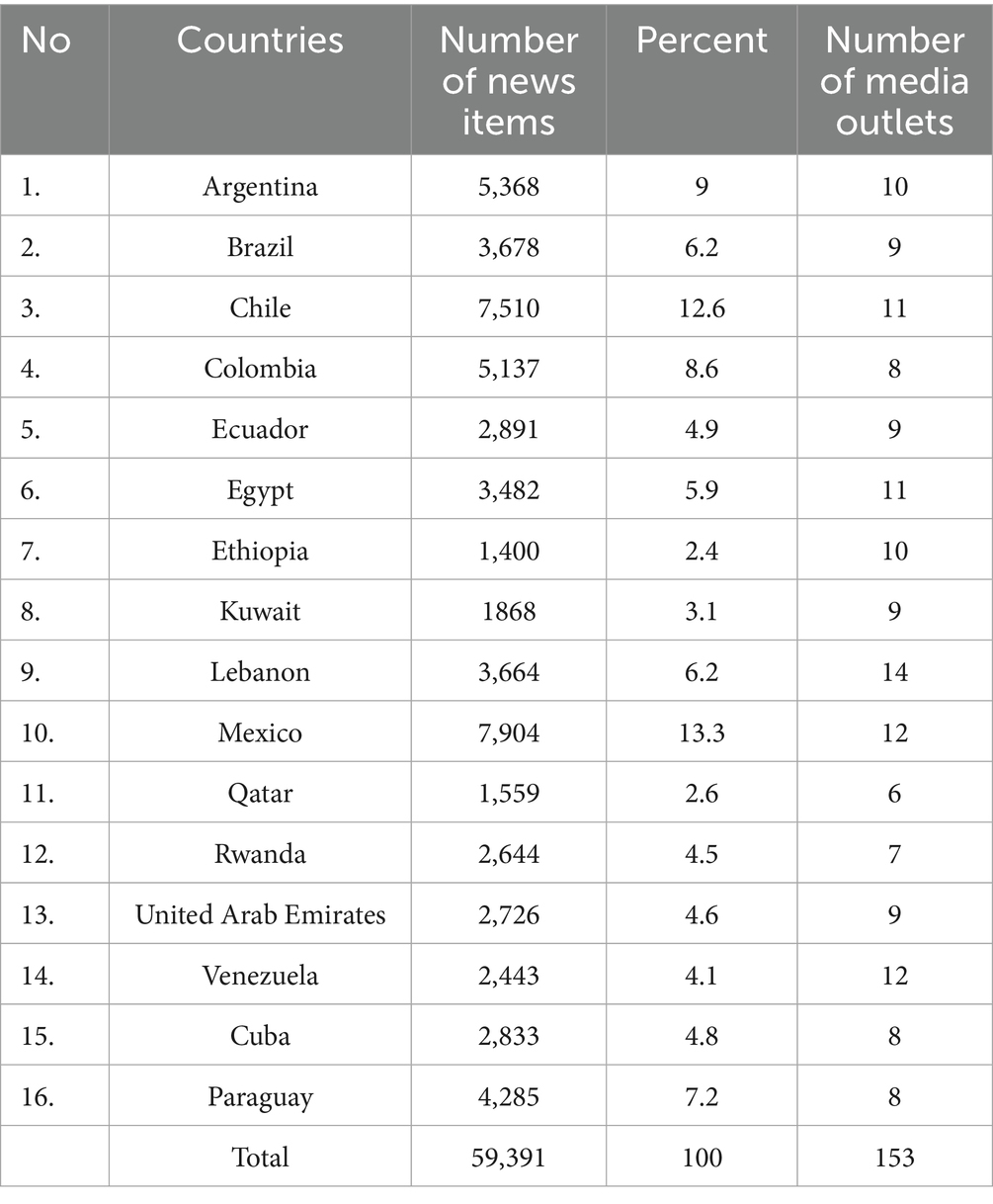

We collected data during 2020 across different media formats (television, radio, print, and online) in 16 Global South countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mexico, Qatar, Rwanda, United Arab Emirates, Venezuela, Cuba, and Paraguay, with a total sample of 59,391 news items from 153 media outlets.

Content analysis was performed for news published in the major newspapers, radio stations, websites, and TV news programs in the countries involved. Different methods were employed to select the sample within each country, depending on the kind of media outlet being examined. The media outlets were selected based on reach, audience size, and impact in setting the public agenda. We selected the most popular outlets in their category, ratings, reviews, or similar criteria. Preference was given to outlets that were national in scope, as well as to ensure that the chosen outlets reflected the diversification of each country’s media environment. Two to four news media outlets are chosen from each platform in each country.

A stratified systematic sample of two weeks was selected for each media outlet in every country between January 2 and December 31, 2020. The selection process employed the “constructed week” method. The analysis examined the same days in all the included media outlets. The researchers divided the year into two six-month periods, January–June and July–December, to account for potential daily and monthly variations in news content. A constructed week was created for each of the six months, and researchers randomly chose the starting dates on Mondays. The subsequent six days were selected using three- to four-week skip intervals. This strategy comprised seven days every six months for a total sample of 14 days over the year.

The news item served as a unit of analysis. The study excluded editorials, opinion pieces, weather forecasts, horoscopes, movie (or cultural) reviews, social pages, puzzles, and similar content on radio and TV. Table 1 shows the distribution of news items, their percentage, and media outlets for each country.

5.1 Measurements

This study used Mellado (2015) operationalization of journalistic role performance, which has been validated in various studies (Mellado et al., 2017; Mellado and van Dalen, 2017; Mellado, 2020b), to measure professional roles in news content. The interventionist role in this study is conceptualized as a form of journalism where the journalist has an explicit presence and voice within the storytelling. This role often involves a journalist acting as an advocate for individuals or groups in society (Mellado, 2015). The degree of interventionism is operationalized based on the extent of the journalist’s active participation in shaping the story: a higher degree of involvement, participation, or advocacy by the journalist implies higher levels of interventionism, and vice versa.

The performance of the interventionist journalistic role was operationalized using five indicators: journalist’s point of view, interpretation, call for action, qualifying adjectives, and first person. These definitions are included in the codebook and guided by the analysis conducted by each national team.

To quantify the interventionist role, items were investigated based on their absence (0) or presence (1) and transformed into dichotomous variables. These items were then combined according to each dimension (range: 0–1) to generate a final score for each news story’s interventionist journalistic role. A higher score indicates higher performance in the interventionist role and vice versa.

Each country had two to four coders responsible for coding each news story. News items in each country were randomly assigned to the coders to reduce bias. Based on Krippendorff’s alpha (Ka), intercoder reliability ranged from 0.72 to 0.91 across the 16 countries.

6 Results

A comparative analysis was conducted to address RQ1 and determine the prominence of the interventionist journalistic role and its key sub-indicators across the 16 selected countries.

6.1 Comparison of interventionist JRP across Global South countries

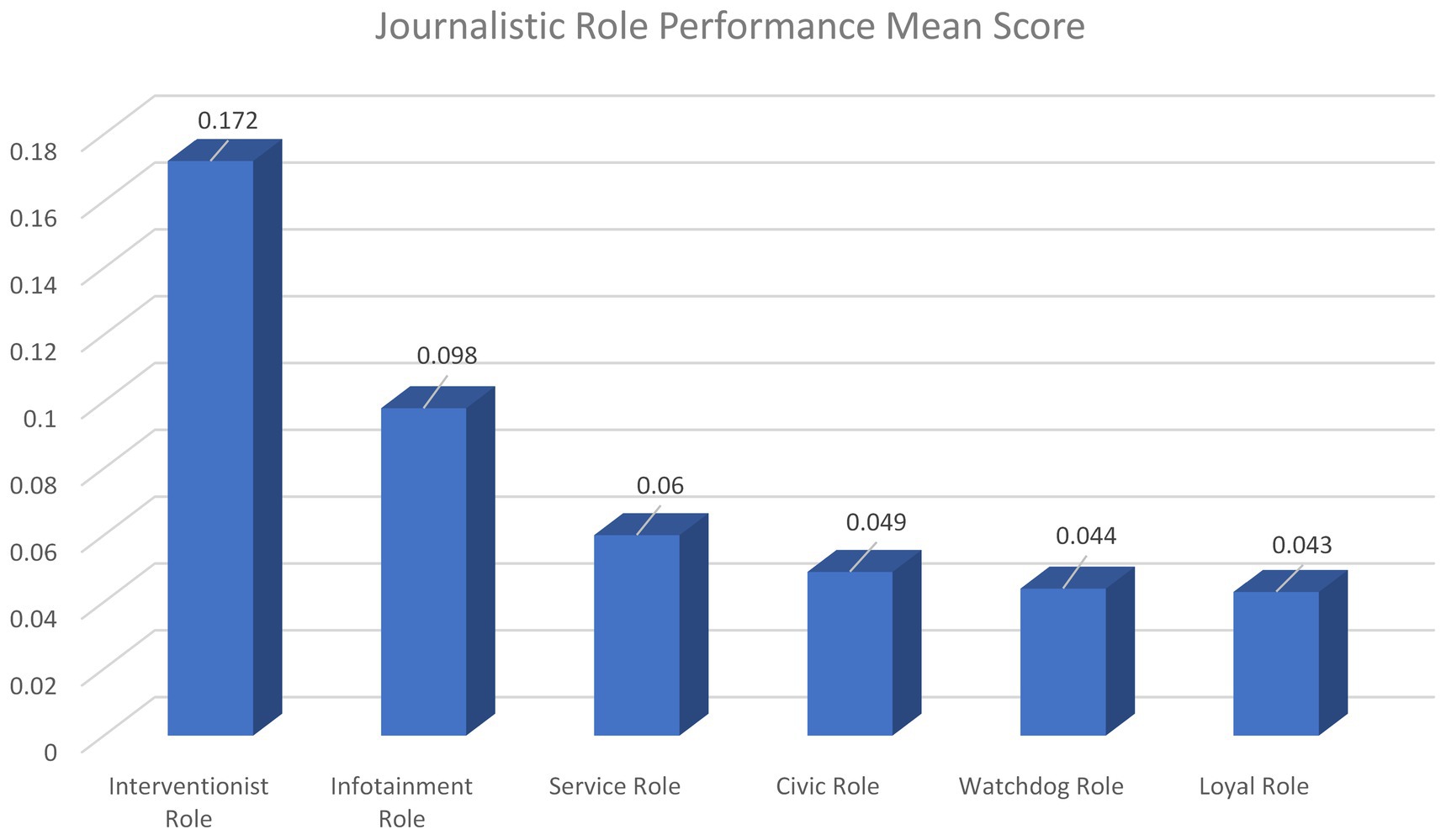

The analysis allowed for comparing interventionist JRP with other journalistic roles across the 16 countries. The interventionist role had the highest mean value, 0.172 (SD 0.217), among the other journalistic roles, such as the loyal, service, civic, infotainment, and watchdog journalistic roles (Figure 1). This may indicate that the interventionist role is the most common in journalism practice across the 16 countries.

6.2 Comparison of interventionist JRP across Global South countries

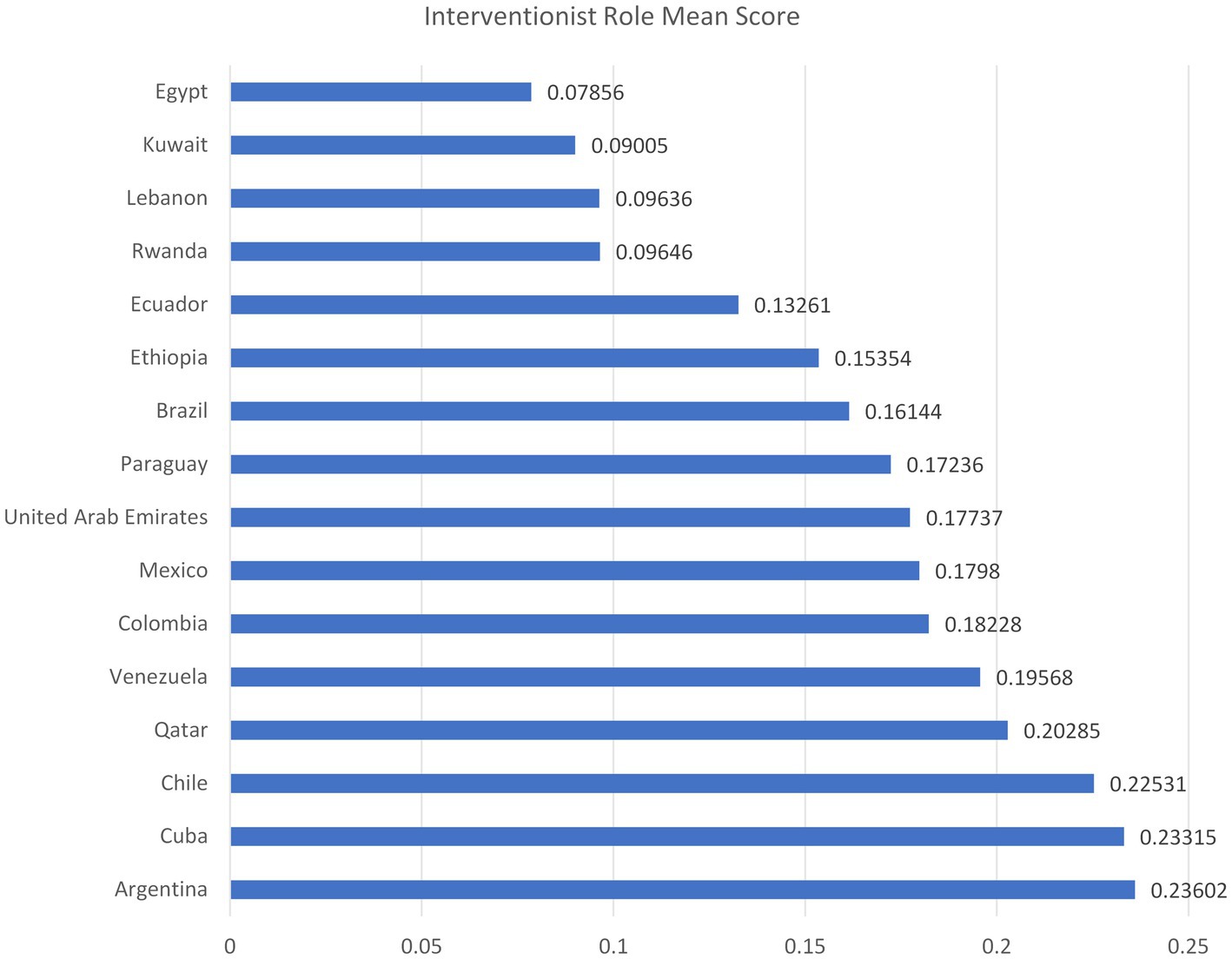

The ANOVA analysis revealed a significant difference in interventionist role performance across the 16 countries (Figure 2) [F(15, 59,374) = 210.397, p < 0.001]. This result indicates that the level of adoption of the interventionist role varies significantly across the sampled countries. Argentina (M = 0.236, SD = 0.251), Cuba (M = 0.233, SD = 0.253), and Chile (M = 0.225, SD = 0.218) had the highest mean values for the interventionist role, indicating a strong presence of this journalistic approach. Egypt (M = 0.078, SD = 0.161), Kuwait (M = 0.09, SD = 0.156), Rwanda (M = 0.096, SD = 0.161), and Lebanon (M = 0.096, SD = 0.179) showed the lowest mean value as an indication of a limited adoption. This result highlights a contextually dependent variation in adopting the interventionist journalistic role across the sampled countries. While Latin American nations demonstrated the strongest adoption of this role, several countries in the Arab and African regions exhibited the lowest levels of interventionism.

Figure 2. Variations in the mean adoption of the interventionist journalistic role across 16 countries.

6.3 A comparative analysis of the aspects of interventionist role performance

A comparative analysis of the five aspects of the interventionist role in news content showed that the most prominent was using qualifying adjectives (32.5%), followed by the interpretation (24.7%). The journalist’s point of view was evident in 15.6% of the total. Using first-person narration was less common at 9.7%, whereas the call for action was the least expressed aspect, accounting for only 3.9%.

Chi-square tests revealed a significant association between all five aspects of the interventionist role and the country of publication (p < 0.001), confirming that the expression of interventionist practices is strongly shaped by national context. Mexico (3.1%), Argentina (2%), and Chile (1.9%) demonstrated the highest percentage of the total sample expressing a journalist’s point of view, whereas Ethiopia (0.1%), Ecuador (0.4%) and Qatar (0.4%) showed minimal use of personal viewpoints.

The inclusion of interpretive elements was significantly more frequent in Latin American countries, particularly Mexico (3.38%), Colombia (2.84%), Chile (2.7%), and Argentina (2.27%). Countries that placed less emphasis on interpretation, preferring descriptive or fact-based reporting, were notably Middle Eastern and African countries, with Ethiopia (0.22%), Lebanon (0.66%), Qatar (0.815%), and Kuwait (0.811%).

The use of qualifying adjectives for color reporting was more common in Latin American countries, including Chile (6.06%), Argentina (3.93%), and Mexico (3.82%). A more restrained use of such language that emphasizes neutrality and impartiality was observed in Middle Eastern and African countries, including Kuwait (0.62%), Rwanda (0.65%), and Ethiopia (0.98%).

Chile (0.56%) was the highest in using the call for action element, followed by Colombia (0.45%) and Mexico (0.38%), indicating that journalists there tend to propose or demand actions or changes. Ethiopia (0.022%), Paraguay (0.051%), and Qatar (0.067%) were the lowest in terms of including a call for action.

Using first-person language (“I,” “we”) differed across countries. Journalists in Chile (2.24%), Argentina (0.99%), and Mexico (0.84%) showed the highest use of first-person references. Meanwhile, Egypt (0.04%), the UAE (0.047%), and Kuwait (0.61%) reported the lowest levels of first-person language usage.

To address RQ2, which asks how news practices (content-related variables) and organizational variables (media outlet-related variables) influence the prominence of interventionist role, we performed one-way ANOVA and t-tests. The analysis revealed statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.001) in interventionist role among the groups categorized by the various content-related variables, including media type, story type, story format, story theme, geographic frame, number of sources, diversity of sources, and diversity of points of view. Story placement was the only variable that did not yield a significant difference.

Analysis revealed, further, that the interventionist role performance in Global South countries differed significantly by media type, story type, and television format. The interventionist role scores significantly varied according to media type [F(3, 59,399) = 86.785, p < 0.001], with TV having the highest mean interventionist score (M = 0.180, SD = 0.221), slightly higher than radio (M = 0.178, SD = 0.231) and online media (M = 0.173, SD = 0.209), while print media had the lowest scores (M = 0.178, SD = 0.231). Regarding the story type factor, [F(3, 59,399) = 1504.549, p < 0.001], reportage demonstrated the highest interventionist score (M = 0.318, SD = 0.242), followed by interviews (M = 0.261, SD = 0.25) and then articles (M = 0.168, SD = 0.207). Brief news stories had the lowest mean score (M = 0.083, SD = 0.146).

The results indicated statistically significant differences in interventionist content across TV story formats [F(3, 59,399) = 1504.549, p < 0.001]; the anchor stories showed the lowest tendency to incorporate interventionist content (M = 0.127, SD = 0.203). Multi-format packages have the highest interventionist content (M = 0.217, SD = 0.003). The standup or reader format obtained an intermediate interventionist score (M = 0.207, SD = 0.232). These findings highlight that Television, along with radio and online platforms, showed higher levels of interventionism than print media. Reportage and interviews carried the strongest interventionist orientation, while brief news remained largely descriptive.

Analysis of variations in interventionist scores by news story theme [F(23, 59,366) = 41.29, p < 0.001] revealed that the most focused story themes on interventionist elements were lifestyle (M = 0.296, SD = 0.255), culture (M = 0.241, SD = 0.237), media (M = 0.223, SD = 0.243), social issues (M = 0.211, SD = 0.241), science/technology (M = 0.206, SD = 0.224), entertainment/celebrities, and sports, while protest, environment, campaigns/elections, police/crime, government/legislatures, health, religion, transportation, defense, and national security showed a lower degree of journalistic intervention. Themes such as court, economy, education, energy, housing, and accidents were found to be less concerned with expressing interventionism.

Analysis showed statistically significant differences in the interventionist role across types of news [F(2, 56,139) = 159.730, p < 0.001]. Soft news had the highest mean score (M = 0.195, SD = 0.218), followed by hybrid news (M = 0.194, SD = 0.227), while hard news had the lowest mean score (M = 0.159, SD = 0.213).

There were also statistical differences in interventionist scores based on the geographic frame of news stories [F(3, 58,477) = 66.156, p < 0.001]. Completely foreign news tends to have a lower interventionist level (M = 0.153, SD = 0.201) than domestic news (M = 0.170, SD = 0.217). Foreign news involving domestic participants (M = 0.198, SD = 0.232) tends to have the highest interventionist levels and is higher than domestic news with foreign participants (M = 0.190, SD = 0.227).

Examining the relationship between the number of sources and the interventionist role revealed a significant positive relationship between the number of sources used in news stories and the level of interventionist [r (59391) = 0.156, p < 0.001]. This result indicates that news articles with more sources tend to have a slightly stronger interventionist journalistic role. The diversity of sources in news stories significantly affected the level of interventionist role [F(2, 59,387) = 393.027, p < 0.001]. Descriptive statistics demonstrated that the stories that incorporated multiple types of sources had the highest interventionist levels (M = 0.207, SD = 0.227), while those with unilateral coverage or sources of the same type showed the lowest interventionist role mean score (M = 0.15, SD = 0.207). News items with no sources had a mean interventionist role score (M = 0.173, SD = 0.222).

The analysis also indicated significant differences in interventionist scores based on the diversity of viewpoints in the news stories [F(2, 59,387) = 395.628, p < 0.001]. The inclusion of multiple viewpoints in news stories had a higher interventionist role (M = 0.22, SD = 0.232) than those lacking viewpoints (M = 0.17347, SD = 0.222) and those with unilateral coverage (M = 0.156, SD = 0.209).

The interventionist role varies significantly depending on the size of media outlets [F(2, 59,387) = 191.271, p < 0.001]. Three sizes of media outlets—small, medium, and large—were used to examine the interventionist role. Medium-sized outlets tended to have higher levels of interventionist (M = 0.196, SD = 0.228) than large-sized (M = 0.173, SD = 0.208) and small-sized media outlets (M = 0.158, SD = 0.211).

A significant association was found between the type of media ownership and differences in interventionist roles. [F(3, 59,386) = 175.29, p < 0.001]. Privately owned media (M = 0.17, SD = 0.215) and state-owned media (M = 0.15, SD = 0.203) had lower interventionist scores than civic society, which had the highest mean interventionist score (M = 0.242, SD = 0.272), followed by publicly traded corporations (M = 0.228, SD = 0.247).

A significant difference exists in the interventionist role score attributed to the media chain structure, t[(59389) = −3.247, p < 0.001]. The interventionist score was higher for news released in media outlets that were a part of a media chain (M = 0.174, SD = 0.217) than for those that were not (M = 0.169, SD = 0.217). The interventionist role of media chain-affiliated outlets is marginally higher, but not enough to suggest a significant pattern.

The influence of newsroom convergence was examined. We used the extent of media platform integration within the organization. The newsroom convergence factor includes full integration, in which infrastructures for multi-channel productions in the news organization are combined in one newsroom; cross-media, where journalists work in separate newsrooms for different platforms but are connected through multimedia coordinators and/or routines along with management that coordinates cooperation and communication between the outlets; or coordination of isolated platforms, where newsrooms are autonomous and lack cooperation or integration in news production or distribution. The results indicated that interventionist scores varied significantly among the various levels of media newsroom integration levels [F(2, 59,387) = 336.672, p < 0.001]. The interventionist score was higher for media outlets with a cross-media newsroom (M = 0.192, SD = 0.227) than for those with full integration (M = 0.155, SD = 0.211) and isolated platform coordination (M = 0.138, SD = 0.188).

Further, the analysis uncovered a statistically significant difference in interventionist scores between media organizations with codified editorial rules and those without [t(59389) = 2.312, p = 0.02]. Media organizations without codified editorial rules had slightly higher interventionist role scores (M = 0.174, SD = 0.222) than those with them (M = 0.171, SD = 0.215).

For newspapers, there was a significant difference in the interventionist role score according to newspaper audience orientation [t(8664.40) = 5.53, p < 0.001], with popular newspapers (M = 0.17, SD = 0.21) showing a higher interventionist role score compared to elite newspapers (M = 0.15, SD = 0.20).

6.4 Sociopolitical contextual factors

This study examined the impact of sociopolitical contextual factors embodied in media political orientation and political alignment factors. Media political orientation was measured by identifying whether the news organization has a left, left-center, center, right-center, or right political leaning. Media political alignment measures whether the outlet has a basic predisposition—either positive or negative—vis-à-vis any political group, political party, political organization, or the political establishment of the country. A t-test [t(59389) = −5.000, p = 0.001] indicated that media outlets with political alignment had a significantly higher interventionist role (M = 0.175, SD = 0.220) than those with no political alignment (M = 0.166, SD = 0.213). The findings showed statistically significant differences in the interventionist role based on political orientation: [F(4, 52,118) = 58.608, p < 0.001]. The highest level of the interventionist role was observed in the left-center (M = 0.209, SD = 0.241) and left-leaning outlets (M = 0.206, SD = 0.245), while center-leaning outlets showed the lowest level.

Based on each country’s ranking on Freedom House Global Freedom Status, the results showed a significant difference in interventionist scores according to political freedom status [F(2, 59,387) = 438.47, p < 0.001]. Countries classified as ‘free’ exhibited the highest levels of interventionism (M = 0.214, SD = 0.231), while those classified as ‘not free’ (M = 0.156, SD = 0.211) or ‘partly free’ (M = 0.155, SD = 0.209) had lower levels of interventionism. This result shows that journalists in free countries have a higher interventionist role than those in ‘not free’ or ‘partly free’ environments.

Pearson correlation analysis revealed a small but significant negative correlation between the interventionist role and the RSF Press Freedom Index rank (r = −0.094, p < 0.001). This indicates that higher press freedom (represented by a lower RSF rank) is associated with slightly higher levels of interventionist journalistic practices.

The Economic Freedom Index measures economic policy, and the level of financial freedom, often called “market orientation,” had a significant influence on the interventionist degree [F(2, 59,387) = 300.548, p < 0.001]. The data indicate that as economic freedom increases, the role of interventionists in news content also increases. Countries with “free” markets had the highest mean (M = 0.212, SD = 0.208), while “partly free” countries had a moderate mean (M = 0.172, SD = 0.219), and “not free” markets had the lowest mean (M = 0.143, SD = 0.215).

The correlation between the geographical regions and the interventionist role score indicated a significant variation in the mean scores of journalists’ interventionist reporting tendencies across three regions of the study—Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East [F(2, 59,387) = 751.941, p < 0.001]. Latin America recorded the highest mean score (M = 0.172, SD = 0.227), followed by the Middle East (M = 0.119, SD = 0.183), while Africa reported the lowest mean score (M = 0.116, SD = 0.170). These findings indicate that Latin American journalists exhibit the highest level of interventionist reporting, while Middle Eastern and African journalists demonstrate lower interventionist tendencies.

To answer RQ3—which examines which factors among content-related, organizational, and socio-political contextual factors most effectively predict the interventionist journalistic role in news content across the 16 countries—we conducted a linear regression analysis to determine which story-related (content-related) variables effectively predict the interventionist role. The predictors tested included story type, format, placement, number, diversity of sources, viewpoints, news theme, news type (hard/soft), and geographic frame. Descriptive statistics indicated a low mean interventionist role score (M = 0.17, SD = 0.22). Correlation analysis revealed significant but generally small differences in interventionist roles attributed to content-related variables.

Stepwise linear regression results showed that story type, number of sources, diversity type of sources, story topic, story format, news type (hard/soft), diversity of points of view, and placement of the story variables significantly contributed to predicting the interventionist role. The regression model was statistically significant [F(8, 55,333) = 782.123, p < 0.001]. The model explained 10.1% of the variance in the interventionist role (R2 = 0.101). The strongest predictors were story type, number of sources, and diversity of sources. Story type (e.g., brief, article, reportage, and interview) exhibited the strongest positive correlation (r = 0.276, p < 0.001), followed by several sources (r = 0.163, p < 0.001) and diversity of points of view (r = 0.078, p < 0.001).

A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of organizational variables on the interventionist role in news content and to examine the extent to which organizational-level variables predict the interventionist role. The organizational variables included media type, outlet size, ownership type, media chain structure, newsroom convergence (editorial codes), codified editorial rules, and media political orientation. A stepwise regression method was used.

The final regression model was statistically significant, F(5, 52,118) = 111.226, p < 0.001. The final model explained approximately 1.1% (R2 = 0.11) of the variance in the interventionist role, with each predictor contributing uniquely to the model. Media codified editorial rules, media outlet size, and media type emerged as the strongest organizational predictors of interventionism, while political orientation and ownership exhibited smaller, yet still significant, effects.

Media-codified editorial rules had a significant negative effect (B = −0.038, p < 0.001), indicating that stricter editorial guidelines reduce journalists’ interventionist practices. Media outlet size showed a significant positive effect (β = 0.022, p < 0.001), indicating that larger media organizations are likelier to exhibit interventionist journalistic roles. Media type also had a significant positive effect (β = 0.011, p < 0.001), suggesting that certain types of media are associated with higher levels of interventionism. Media political orientation demonstrated a significant negative effect (β = −0.008, p < 0.001), implying that outlets with stronger political leanings tend to show lower interventionism. Media ownership exhibited a significant negative effect (β = −0.006, p < 0.001), indicating that outlets with more concentrated ownership are associated with reduced interventionist practices.

A stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the influence of macro-level socio-political contextual factors on the interventionist role. The analysis included six predictors: geographical region, GDP per capita, RSF Press Freedom Index Rank, Freedom House Global Freedom Score, the REC Economic Freedom Index, and the Heritage Foundation Economic Freedom Index. The final model was significant [F(6, 56,941) = 370.951, p < 0.001], with all predictors collectively explaining approximately 3.8% of the variance in the interventionist role (R2 = 0.038). While statistically significant, the explained variance is relatively small, indicating that most of the variation in interventionism is influenced by other factors not included in the model.

The geographical region factor emerged as the strongest predictor (β = −0.213, p < 0.001), highlighting that certain regions are associated with certain levels of interventionist journalistic roles. GDP per capita was a positive predictor [β = 0.060, p < 0.001], indicating that wealthier countries tend to have higher levels of interventionist journalism. The RSF Press Freedom Index Rank showed a significant negative relationship [β = −0.099, p < 0.001], where lower press freedom (higher rank) is associated with a weaker interventionist role.

The Freedom House Global Freedom Score also had a negative effect (β = −0.115, p < 0.001), confirming that higher political freedom correlates with a less interventionist journalistic role. Interestingly, REC Economic Freedom showed a positive effect (β = 0.063, p < 0.001), indicating that higher economic freedom supports a more interventionist journalistic approach.

A simple linear regression was performed to test H1, which hypothesized that higher levels of sociopolitical constraint, reflected in lower degrees of freedom, would be negatively associated with interventionist journalistic role performance. The predictor was the Restriction Index, a composite measure of sociopolitical constraint. To operationalize this construct, three standardized indicators were combined: the Freedom House Global Freedom Score, the RSF Press Freedom Index, and the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom (2020 editions).

The regression model was statistically significant, F(1, 59,389) = 458.25, p < 0.001, but explained less than 1% of the variance in interventionist role performance (R2 = 0.008, adjusted R2 = 0.008). The results indicated a significant negative relationship between sociopolitical constraint and interventionist journalistic role performance, B = −0.010, SE < 0.001, β = −0.088, t(59,389) = −21.41, p < 0.001. In other words, as sociopolitical constraints increased (lower levels of freedom), interventionist journalistic role performance levels significantly decreased. This supports the hypothesized negative association. While these findings offer valuable preliminary evidence of association, the modest R2 value indicates that the identified predictors account for only a limited portion of the variance in the outcome. Additional factors not captured in the current models likely contribute to the observed results.

7 Discussion and Conclusion

The primary objective of this research was to understand the interventionist journalistic role performance across various Global South countries. The study examined interventionist journalism role performance in 16 Global South nations using quantitative content analysis of 59,391 news items from 153 media outlets based on the operationalization framework to measure journalistic role performance within news content.

Results revealed that the prominence of the interventionist journalistic role varied significantly across Global South countries. Argentina, Cuba, and Chile recorded the highest mean values for the interventionist role, indicating a strong presence of this journalistic approach. Egypt, Kuwait, Rwanda, and Lebanon showed the lowest mean value, indicating a limited emphasis on this role.

There was also significant variation in incorporating interventionist sub-indicators. Qualifying adjectives emerged as the most prominent interventionism technique, followed by interpretation. Journalists’ explicit points of view, using first-person narration and calls for action, were less frequently employed. This pattern indicates that while journalists often influence audience perception through subtle language choices and explanatory framing, they avoid overtly inserting themselves into the story. Such findings indicate a preference for indirect forms of intervention, maintaining a balance between traditional norms of neutrality and the journalist’s interpretative role.

Regarding the content-related factors, TV had the highest mean interventionist score, slightly higher than radio and online media, while print media had the lowest scores. This may partially show that traditional audiovisual media in the Global South are more likely to use interventionist role aspects. Such findings support previous work that provides evidence of the Global South’s efforts to maintain control over audiovisual media, using it as a vital tool to promote governmental policies and foster a sense of integration and unity among members of society. This result is consistent with scholarly evidence from Ethiopia (Skjerdal, 2024), Rwanda (McIntyre and Cohen, 2022), and China (Mirrlees, 2023), which indicates that audiovisual media in the Global South may be more susceptible to state control or influence than print and online media, often due to direct ownership, regulatory frameworks, and the perceived power of broadcasting in shaping public opinion.

Interventionist content is also more prominent in soft or hybrid news than hard news. These results demonstrate that journalists in the global south tend to take a more active and interpretative role when covering themes such as lifestyle, culture, media, social issues, science, and technology. At the same time, hard news showed lower scores for the interventionist role, which may be due to professional standards emphasizing factual reporting and objectivity. In contrast, soft news allows more narrative flexibility and subjective voice, making it more conducive to an interventionist role. Regarding the story type factor, reportage-style stories were the most interventionist-oriented, whereas brief stories were less. Completely domestic or completely foreign news tends to have a lower interventionist level than foreign news or domestic news involving foreign participants.

The numbers and variety of sources also significantly impact interventionist levels. News stories with more sources tend to have higher levels of interventionism. News items incorporating multiple types of sources in reporting were more likely to produce content with higher levels of intervention than relying on sources of the same type or unilateral coverage. Including multiple viewpoints in the news appeared to significantly increase interventionism, while reliance on unilateral or no sources is associated with a lower interventionist role.

The linear regression analysis showed that among content-related variables, story type, number of sources, and diversity of points of view are the most significant predictors of the interventionist journalistic role in Global South news content. This result implies that the interventionist journalistic role in news reporting is more likely to increase in the Global South media in interpretative stories, feature multiple and diverse sources, and present multiple viewpoints. In other words, the interventionist role is more associated with more complex storytelling with diverse sources and analytical formats rather than event-based reporting.

At the organizational level, the analysis indicated that media outlet size significantly influenced the interventionist level. Medium-sized media outlets are more likely to produce content with higher levels of intervention than large- and small-sized outlets. Regarding ownership patterns, media outlets owned by civic society organizations and publicly traded corporations exhibited the highest interventionist roles. In contrast, privately owned and state-owned media exhibited the lowest. There is a statistically significant difference between media outlets with and without a media chain structure in interventionist journalistic role scores. Media organizations without codified editorial rules have slightly higher interventionist role scores than those with formalized editorial codes and guidelines. Popular newspapers showed a slightly higher interventionist mean score than the elite newspapers’ audiences. Media political orientation and political alignment significantly affect interventionist levels. Media outlets with left-leaning orientations and those with political alignment are more likely to produce interventionist-focused content.

The impact of media outlet size and ownership structure on interventionism can be attributed to greater resources, commercial interests, increased competition, financial pressures, and diverse editorial strategies, all of which influence news practices. Additionally, analysis of the influence of organizational factors indicates that outlets with more concentrated ownership and stricter formalized editorial guidelines were associated with reduced interventionist practices. This outcome implies that concentrated media ownership structures and stricter editorial guidelines might emphasize adherence to traditional notions of objectivity. This emphasis discourages journalists from embedding their personal opinions in news content due to imposing top-down pressures that dissuade them from adopting an overt interventionist stance, which might be perceived as disruptive or contrary to the owner’s strategic objectives.

These results support previous research that found that Latin American media tends toward more varied and often politically polarized reporting, with a notable presence of interventionist roles in a largely privatized media landscape facing threats to journalist safety (Oller et al., 2017). In contrast, African and Middle Eastern countries often exhibit more substantial state influence over media, leading to a refraining from the interventionist role, significant restrictions on press freedom, and, in some cases, a greater emphasis on development journalism (Mutsvairo and Bebawi, 2022).

Findings showed that economic freedom status plays a significant role in shaping interventionist role performance in Global South countries. Journalists operating in free economies are more inclined toward an interventionist role than those in partly free or non-free economies. Countries with higher GDP per capita tend to have slightly higher levels of interventionism in news content.

The regression analysis revealed multiple macro-level factors significantly predict the interventionist journalistic role. Higher economic development (GDP per capita) and greater economic freedom were positively associated with interventionist tendencies, while higher press freedom and political freedom scores were negatively related. The results indicated that regional contexts, economic development levels, and political and press freedom influence interventionist journalistic role performance. Specifically, interventionism is stronger in certain geo-cultural regions, wealthier countries, and countries with lower political and press freedoms. These findings indicate that geographic-cultural and macroeconomic-political factors shape the degree to which journalists adopt interventionist roles in their reporting. Political freedom status is significantly associated with interventionist role scores. The statistical analysis showed that journalists in Global South countries classified as free countries tend to have a higher interventionist role than those in ‘not free’ or ‘partly free’ environments.

The findings support the hypothesis empirically, demonstrating that sociopolitical constraints are negatively associated with interventionist role performance among Global South journalists. The data indicate that greater restriction appears to suppress interventionist practices. In highly constrained political environments, journalists may be less willing—or less able—to adopt interventionist approaches due to fear of censorship, legal sanctions, or personal harm. Instead, they may prioritize compliance with state narratives, practice self-censorship, or confine their reporting to less sensitive issues. This pattern is consistent with literature showing that non-free contexts constrain journalistic autonomy and discourage adversarial reporting (Voltmer, 2013; Hanitzsch et al., 2019). In freer environments, journalists benefit from greater legal and institutional protection, which enables them to critically interpret events, advocate for social change, and intervene more directly in public debates. The small effect size (R2 = 0.008), reflecting the model’s minimal explanatory power, indicates that the interventionist role is likely influenced by a broader and more complex set of factors, including newsroom culture, market pressures, professional norms, and individual journalist values. This result highlights the multifaceted nature of conditions shaping this journalistic practice.

Despite significant variation in the prominence of the interventionist journalistic role across Global South countries, a discernible regional or geographical pattern emerged. Most Latin American countries exhibited a high level of journalistic interventionism, whereas most Arab countries demonstrated a low level in deploying this role. This pattern could be interpreted through sociopolitical, historical, and systematic media factors, and dominant journalistic cultures.

Factors that contribute to high interventionism in Latin America may include a legacy of struggles for democracy and social justice. Many Latin American countries have long histories marked by political instability, authoritarian regimes, social inequalities, and periods of conflict, which have shaped this interventionist journalistic role. In such environments, journalism often transcends a purely “objective” or “neutral” role, evolving into a more active participant in social and political processes. Journalists may feel a strong imperative to expose corruption, advocate for marginalized groups, or challenge powerful elites, leading to more interventionism (Mellado and van Dalen, 2017; Hanitzsch et al., 2016). This aligns with the understanding of advocacy journalism, where reporters intentionally infuse their opinions to drive social change. In addition, partisan and opinion-oriented Journalism in many Latin American nations is characterized by a more partisan and opinion-oriented culture, where news outlets are often explicitly aligned with political groups or ideologies. Also, in countries transitioning from authoritarianism or struggling with democratic consolidation, journalists have often played a crucial role in advocating for human rights and democratic values. This active stance naturally leads to interventionist practices. The previous finding supports other studies arguing that such an environment legitimizes and encourages journalists to embed their voices, biases, or opinions within news content, leading to a higher interventionist dimension of journalistic role performance (Márquez-Ramírez et al., 2019; Mellado, 2015, 2020a, 2020b).

While political context is foundational, the prominence of the interventionist role in Latin America is also shaped by various economic and organizational factors. Many media outlets’ economic precarity and reliance on politically and corporately influenced advertising markets can incentivize journalists to adopt interventionist roles to maintain professional legitimacy and audience engagement (Mesquita and de-Lima-Santos, 2023). Furthermore, within Latin American newsrooms, advocacy and social change have historically been viewed as legitimate functions, a perspective reinforced by journalism education systems prioritizing social responsibility over traditional objectivity models (Hanitzsch et al., 2019; Mesquita and de-Lima-Santos, 2023). This combination of economic pressures and professional traditions fosters an environment where interventionist practices can become a core part of a news organization’s identity.

On the other hand, in many Arab countries, the pervasive factor is the significant state control or influence over media outlets. Governments often impose strict censorship and monitor content, directly inhibiting overt forms of interventionism. Journalists operating under such conditions may self-censor, leading to a more cautious, less assertive, and thus lower interventionist approach (Rugh, 2004; Zayani and Sahraoui, 2007). Additionally, the economic models of media in many Arab states often rely heavily on state subsidies or government advertising, creating a financial dependency that discourages independent or interventionist journalism. In some African contexts, particularly those with more restrictive political systems like, journalists perceive roles that “support official policies to bring about prosperity and development” and “convey a positive image of political and business leadership” as highly important (McIntyre and Cohen, 2022). The previous result may highlight how national media cultures, political contexts, and journalistic traditions can significantly influence how journalists perform their professional roles, especially how much they intervene in news content.

The practical implications of this study lie in its focus on interventionist practices, dynamics, and the various nested levels of factors that influence this phenomenon. These findings also have significant implications for media organizations and policymakers, highlighting the need for adaptive strategies considering how organizational and contextual influences may support or counteract interventionist-driven journalistic practices. Additionally, findings can guide media policymakers in different sociopolitical and media contexts and support journalists in balancing journalistic standards, engaging audiences, achieving profitability, and responding to the challenges imposed by political, economic, and media systems within the evolving global south.

This study has several limitations. First, future research could expand to include more Global South countries representing diverse media systems, in order to identify patterns of interventionist journalistic practices across contexts. A further limitation of this study lies in its exclusive focus on the interventionist role, without deeper consideration of its relationship to other dimensions such as loyal facilitator, service, and watchdog roles. Another limitation of this study is the model’s relatively low explanatory power, as indicated by the small R2 value, which highlights the influence of other unmeasured or unmodeled factors. Additionally, the data were collected in 2020, a period when the coronavirus pandemic was disrupting daily life and imposing stricter constraints on journalistic practices to curb misinformation and manage public panic. Further studies may investigate audience perceptions of interventionists, their narrative structure, and differences in interventionist role practice across platforms. Additionally, cross-cultural comparisons of interventionist content may enhance understanding of its dynamics across diverse contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

NF: Writing – review & editing. HE: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the international research project Journalistic Role Performance around the Globe (http://www.journalisticperformance.org). We would like to thank all the other regional researchers participating in this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the revising of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, Quillbot, Grammarly) was used to assist in manuscript revision, including language editing, text condensation, and grammar correction. The AI-generated output was reviewed and revised by the authors to ensure accuracy and appropriateness.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aryal, S. K., and Bharti, S. S. (2022). Changing the media landscape in India under the Modi government: a case study based on the narrative policy framework. Stud. Z Polit. Publicznej 9, 3, 47–64. doi: 10.33119/kszpp/2022.3.3

Atal, M. R. (2017). “Competing Forms of Media Capture in Developing Democracies” in In the Service of Power: Media Capture and the Threat to Democracy (The Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA)), 19–32. Available at: https://www.cima.ned.org/publication/media-capture-in-the-service-of-power/

Badrinathan, S., and Chauchard, S. (2024). Researching and countering misinformation in the Global South. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 55:101733. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101733

Baleria, G. (2021). The journalism behind journalism: Going Beyond the Basics to Train Effective Journalists in a Shifting Landscape. New York: Routledge.

Bartholomé, G., Lecheler, S., and De Vreese, C. (2015). Manufacturing Conflict? How journalists intervene in the conflict frame building process. The International Journal of Press/Politics 20, 438–457. doi: 10.1177/1940161215595514

Blum, R. (2014). Lautsprecher & Widersprecher. Ein Ansatz zum Vergleich der Mediensysteme. Köln: Herbert von Halem 444 Seiten.

Bull, B., and Banik, D. (2025). The rebirth of the Global South: geopolitics, imageries, and developmental realities. Forum Dev. Stud. 52, 195–214. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2025.2490696

Chadha, K. (2017). The Indian news media industry: Structural trends and journalistic implications. Global Media and Communication 13:139. doi: 10.1177/1742766517704674

Cox, J. B., Miller, S., and Shin, S. Y. (2024). The News Sourcing Practices of Solutions Journalists in Africa, Europe, and the U.S. Journal. Pract., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2024.2394556

Cushion, S., Lewis, J., and Ramsay, G. N. (2012). The impact of interventionist regulation in reshaping news agendas: a comparative analysis of public and commercially funded television journalism. Journalism 13, 831–849. doi: 10.1177/1464884911431536

Degen, M., Olgemöller, M., and Zabel, C. (2024). Quality journalism in social media – what we know and where we need to dig deeper. Journalism Stud. 25, 399–420. doi: 10.1080/1461670x.2024.2314204