- Institute of Art, Communication University of China, Beijing, China

The platformization of social media has reconfigured creative labor globally, yet its dynamics unfold with distinct intensity in China’s unique digital ecosystem, characterized by state-market hybrid governance and algorithmic collectivism. In this study, we draw on 19 months of embedded fieldwork and in-depth interviews with 20 content creators, to examine how young Chinese bloggers deploy informal manipulations—tactical practices that resist and repurpose platform constraints. The result reveals a dialectical dynamic wherein these grassroots tactics simultaneously sustain platformization and cultivate creative agency, functioning as critical mechanisms for mediatization. Crucially, We identify the emergence of digital spiritual artisanship—a psychosocial process through which creators reconcile labor alienation with self-actualization through culturally-inflected practices of self-cultivation and community-building. Our work advance platform labor theory by conceptualizing informal resistance as co-constitutive of platform evolution, theorizing “Digital Craftsmanship Spirit” as a culturally distinct survival strategy under algorithmic collectivism, and mapping China’s unique governance model onto global digital labor debates.

1 Introduction

The platformization of creative labor has reconfigured digital economies globally, embedding extractive logics within socio-technical infrastructures (Bhandari and Bimo, 2022; Atanasova et al., 2025). In China, however, this process unfolds within a unique ecosystem characterized by state-market hybrid governance and algorithmic collectivism—conditions that intensify tensions between platform control and user agency (Kaye et al., 2021; Li, 2024). Young content producers (aged 18–35), constituting 68% of China’s 110 million social media creators (CNNIC, 2024), navigate these constraints through informal manipulations—grassroots tactics like algorithm-gaming and mutual-aid networks that simultaneously sustain and resist platform dominance (Duffy and Meisner, 2023).

Platform infrastructures offer affordances—action possibilities that users repurpose tactically (Avalle et al., 2024). In China, young bloggers leverage affordances for informal manipulations: (1) Economic precarity to Algorithmic gaming: Trading visibility for revenue (Duffy et al., 2019); (2) Identity disciplining to Community-building: Virtual networks as sites of resistance (Jiang et al., 2024; Treré and Yu, 2021); (3) Material ontology: Platforms as contested infrastructures where labor relations are reconfigured (Boscarino, 2022).

This frame expose power while generating new value (Pronzato, 2024). Yet, how these practices drive platformisation dialectically remains untheorized. While prior research establishes platforms’ extractive logic (Crain, 2018) and China’s governance hybridity (Li, 2024), critical gaps persist in understanding how informal manipulations dialectically drive platformization. Specifically, studies inadequately address: (1) how grassroots tactics reshape platformization pathways; (2) why psychological resilience mediates labor domestication (Büchi and Hargittai, 2022); and (3) how China’s “disciplined innovation” model reconstitutes digital alienation (Zhou and Liu, 2024).

This study empirically decodes young bloggers’ agentive resistance within China’s platform ecology. We investigate: How informal manipulations promote the development of platformization while resisting its negative impact on the creative ecosystem; What psychosocial processes enable creators to reconcile alienation with self-actualization; How China’s model informs global digital labor debates.

Our contribution threefold advances platform studies: revealing algorithmic dialectics where resistance is co-opted yet generative, identifying “Digital Craftsmanship Spirit” as a culturally-distinct survival mechanism, and mapping Chinese platform governance onto global labor discussions.

2 Theoretical framework

This study is situated at the intersection of platform studies, digital labor theory, and critical sociology of communication, drawing on a synthesis of theoretical perspectives to conceptualize the informal manipulations of Chinese bloggers. Our framework is anchored in the concept of platformization—the process by which digital platforms reshape cultural production and embed their infrastructural and economic logics into social life (Bishop, 2025; Nieborg and Poell, 2018). Platformization scholarship has predominantly highlighted the extractive nature of platforms and the structural constraints they impose on users (Crain, 2018; Brucks and Levav, 2022). However, this top-down perspective often overlooks the nuanced agency and tactical ingenuity of users who navigate these infrastructures.

To theorize this agency, we integrate de Certeau’s distinction between strategies (the powerful’s structuring of space) and tactics (the art of the weak in operating within imposed spaces) (Certeau, 1984). In the context of platform labor, we conceptualize bloggers’ informal practices—such as algorithm-gaming and mutual-aid networks—as quintessential tactics. These are everyday and imperceptible manipulations that repurpose platform affordances for user-defined ends (Burai et al., 2024; Davidson and Joinson, 2021). This moves beyond a binary of domination versus resistance towards a dialectical understanding where user tactics are not merely oppositional but are often co-opted by and co-constitutive of platform evolution (Popiel and Vasudevan, 2024; Pronzato, 2024).

Furthermore, we engage with theories of digital labor and alienation to understand the psychosocial dimensions of this work. Platform labor is seen as a site of value extraction where users’ creative activities are commodified (Khelladi et al., 2022; Kreiss and McGregor, 2024). This often leads to a sense of alienation—a separation of the creator from their product, their creative process, and their community (Hochschild, 1983). Instead of framing bloggers solely as alienated laborers, we draw on the concept of “hope labor” (Tsang and Wilkinson, 2025). Fetishism of Money, Capital, Interest-Bearing Capital and Commodities. In: Fetishism and the Theory of Value. Palgrave Studies in the History of Economic Thought—the investment of unpaid work in anticipation of future rewards—and extend it by introducing the culturally-inflected notion of “digital craftsmanship spirit.” This concept captures the intrinsic, self-cultivating practices through which bloggers seek to reconcile labor alienation with self-actualization, a process particularly salient within collectivist cultural contexts that value moral and personal development.

Finally, we contextualize these dynamics within China’s unique state-market hybrid governance model, characterized by “algorithmic collectivism” (Fan, 2024; Guarriello, 2019; Kaye et al., 2021) and “disciplined innovation” (Li, 2024). This model creates a distinct ecosystem where platform rules are intertwined with state-led ideological imperatives, intensifying the tensions between control and agency (Habermas, 2022; Ho et al., 2022). By mapping these theoretical coordinates—platformization, tactical agency, the dialectics of labor, and Chinese specific governance—this framework provides a robust lens for analyzing how informal manipulations simultaneously sustain and subvert the very systems they operate within, thereby advancing a more nuanced understanding of platform power and user ingenuity in a non-Western context.

3 Data and methods

This study employs critical ethnography (Madison, 2019), grounded in “content as infrastructure” (Plantin et al., 2018), to examine how Chinese bloggers navigate platform constraints through informal manipulations. The author, positioned as a participant-observer, embedded within three creator mutual-aid groups on Douyin and Weibo (January 2023–July 2024), adopting an empathic insider’ role to document tactical exchanges. All participants provided informed consent, with pseudonyms and blurred identifiers protecting anonymity. We reflexively acknowledge our dual positionality as scholars educated in Western and Chinese institutions, both critical of platform capitalism and empathetic to creators’ autonomy struggles.

3.1 Participant selection and sampling rationale

3.1.1 Research operations

A purposive sampling strategy was adopted to capture maximum variation across:

Platform type: Douyin (n = 8); Bilibili (n = 6); Xiaohongshu (n = 6).

Revenue tier: High (>$500 k/year, n = 7); Medium ($200–500 k, n = 8); Low (<$200 k, n = 5).

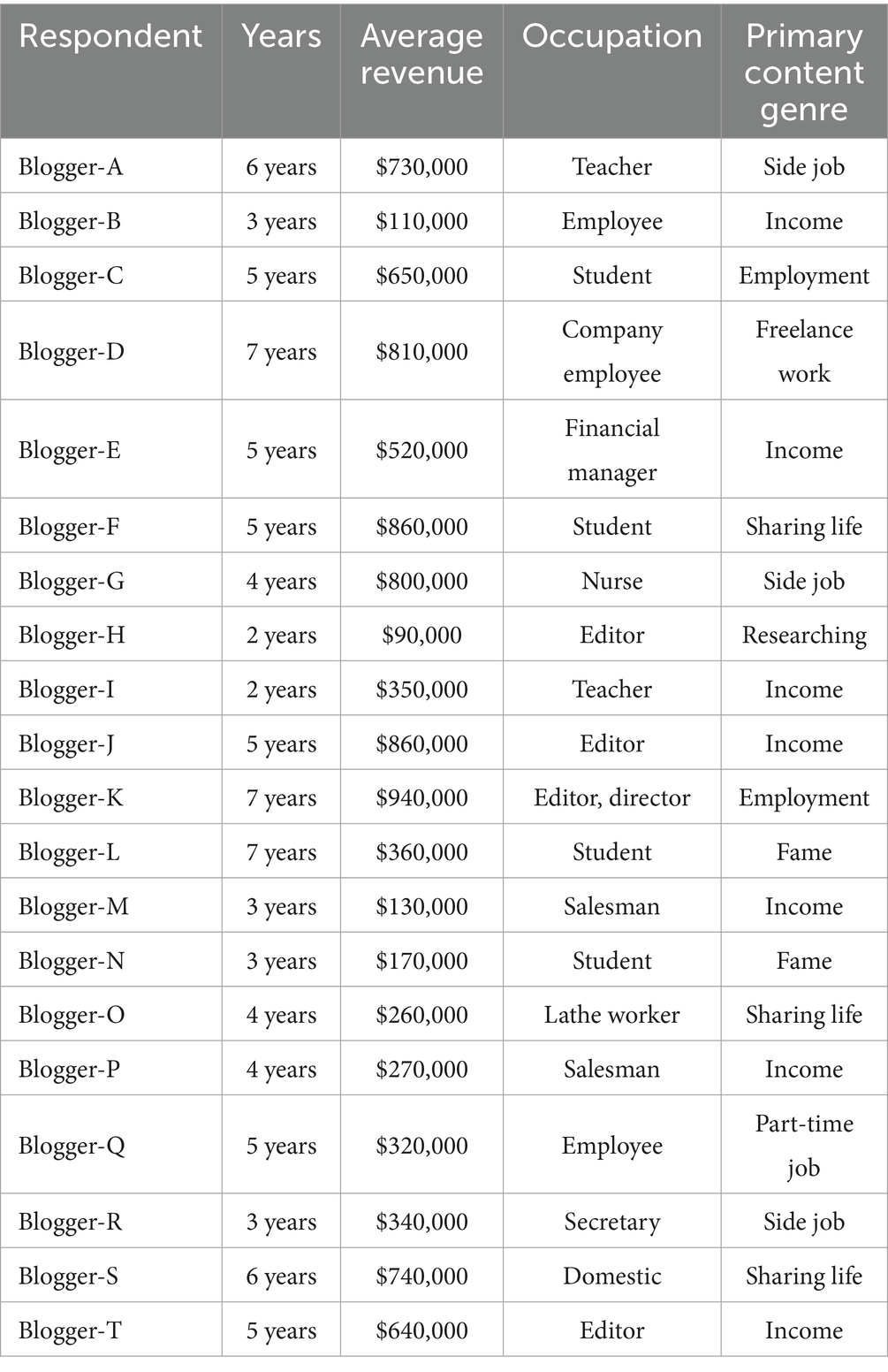

Occupational background (see Table 1): The income listed in the table refers to the bloggers’ annual income, and it is the income before the platform deducts its share. Typically, the platform and the MCN agency will deduct a share of 40 to 60% from this income.

Content genre: Lifestyle (n = 9); Knowledge (n = 6); Entertainment (n = 5).

Inclusion criteria: Aged 18–35 (CNNIC’s “young creator” benchmark); ≥5 years’ independent creation history (no MCN affiliation); Demonstrated use of informal manipulations (e.g., mutual-aid groups); Aggregate followers ≥2 M (validating platform influence).

Rationale: This stratification ensures diversity for cross-case analysis (RQ3) while targeting information-rich cases for RQ1–RQ2 (Patton, 2015). Sampling concluded at 20 participants upon reaching thematic saturation (Guest et al., 2006).

3.1.2 Sampling strategy and representativeness

A purposive sampling strategy was implemented to capture maximum variation across Chinese content creator ecosystem, stratifying participants by platform type, revenue tier, occupational background, and content genre. This approach prioritized information-rich cases that could provide diverse perspectives on informal tactical practices.

Our sample of 20 established creators (all maintaining ≥2 million followers and ≥5 years of experience) intentionally focuses on successful platform professionals whose prolonged engagement offers deep insights into tactical evolution. However, we explicitly acknowledge the sample’s systematic urban, educated bias, with most participants residing in first-tier cities and holding university degrees. Semi-structured interviews (60–90 min) were conducted with all 20 participants, following an iterative protocol that evolved with emerging findings.

This socioeconomic position fundamentally shapes their expression of “digital craftsmanship spirit,” enabling greater focus on self-actualization and community-building rather than economic survival. While this limits generalizability to less privileged creators, it provides crucial understanding of how relatively successful creators navigate and persist within platform economies. Future research comparing creators across success tiers would valuably complement these findings by examining how digital craftsmanship manifests under different conditions of precarity.

This sampling approach thus offers particular insight into the practices of China’s emerging professional creator class while transparently acknowledging its demographic limitations.

3.2 Data collection procedures

1. Participant Observation: Over a continuous 19-month period (January 2023–July 2024), the author conducted immersive participant observation within three prominent creator mutual-aid groups on Douyin and Weibo, adopting an empathic insider role (Madison, 2019).

This approach involved active engagement in daily interactions, tactical discussions, and content coordination activities, enabling deep access to bloggers’ informal practices. Unlike distant observation, this method allowed for real-time documentation of how algorithmic constraints were navigated, how platform policy changes triggered tactical adaptations, and how community norms emerged organically.

The observation covered 312 distinct activities, categorized into:

a. Content Production Workflows: Tracking algorithmic timing of posts, A/B testing of thumbnails, and use of trending hashtags.

b. Informal Tactics: Documenting “hugging warming” sessions where creators exchanged likes/comments, covert use of data-inflation tools, strategic practices of cross-platform traffic diversion.

c. Platform Policy Responses: Recording instances of demonetization, regulations on prohibiting dissemination, and creators’ collective countermeasures.

1. Semi-Structured Interviews: This study conducted 60–90 min interviews iteratively, with protocols aligned to RQs:

RQ1: “Describe tactics used to bypass algorithmic constraints.”

RQ2: “How do revenue goals impact creative choices psychologically?”

RQ3: “How do the platform’s dissemination rules shape your practices?”

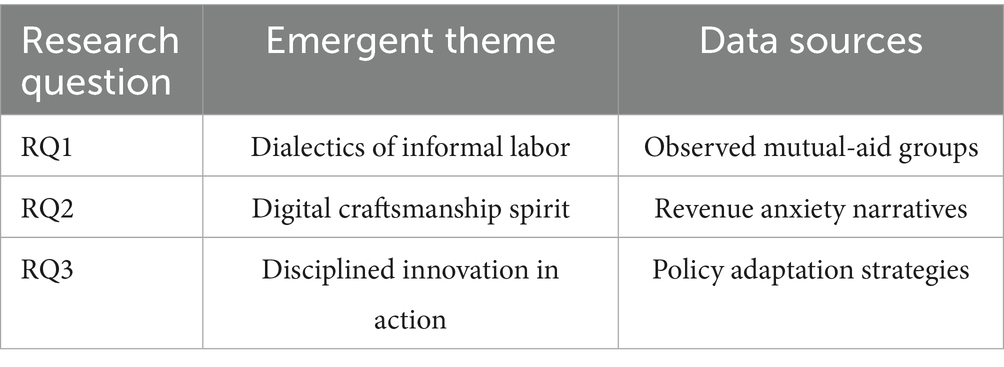

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, back-translated, and analyzed via constructivist thematic analysis (Braun an Clarke, 2006). Coding identified 78 initial codes (e.g., “algorithm-gaming,” “community-as-resistance”), grouped into themes mapping to RQs (see Table 2). Triangulation included methodological (observation vs. interview), data source (revenue tier comparisons), and member checking with six participants.

1. Operationalizing “Informal Manipulations”

Participants were screened for demonstrated use of ≥3 tactical categories:

Algorithm-Gaming: Artificially inflating engagement via mutual-aid groups.

Boundary Work: Circumventing content restrictions through coded narratives (e.g., using “rice” for money).

Data Inflation: Deploying bots or click farms to simulate organic growth. This multilevel screening ensured participants embodied the “informal manipulation” phenomenon under study, moving beyond self-reporting to observable practices.

1. Triangulation and validity

To mitigate sampling bias, we integrated:

Methodological triangulation: Comparing observed behaviors with interview claims.

Temporal triangulation: Tracking tactics across platform policy shifts (e.g., post-“Clean Net” campaigns).

Member checking: Preliminary findings were validated by 3–5 participants, enhancing interpretive accuracy.

Conceptual Operationalization: The core concepts of “informal manipulations” and “digital craftsmanship spirit” were systematically operationalized through observable indicators. Informal manipulations were identified through three behavioral categories: algorithm-gaming (e.g., mutual-aid groups), boundary-testing (coded language), and metric inflation. Digital craftsmanship spirit was tracked through linguistic markers including craft metaphors (“polishing content”), expressions of spiritual sustenance, and community-building narratives.

3.3 Analytical process of data

Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) iterative process:

Familiarization: Immersion in memos and transcripts.

Code Generation: This study has extracted 78 codes (e.g., “algorithmic resistance,” “community-as-infrastructure”).

Theme Development: Grouping codes into dialectical themes (e.g., “co-opted resistance”).

Reflexive Refinement: Using researcher journals to contextualize findings within power dynamics.

This rigorous approach addresses reviewer concerns by clarifying methodological coherence, researcher positionality, and conceptual operationalization—key gaps in critical digital ethnography.

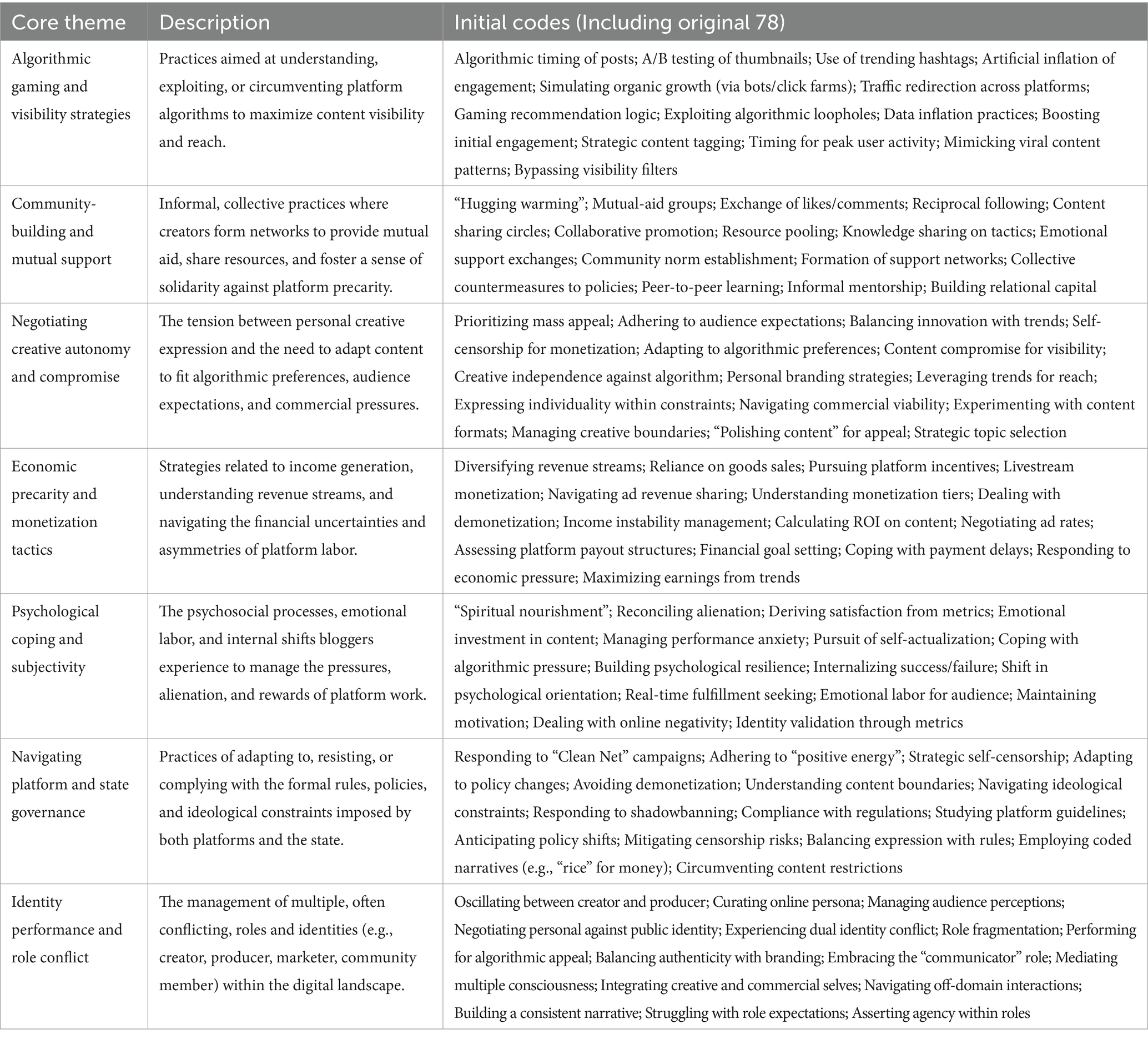

The following are the results of thematic categorization based on 78 initial codes extracted from the critical ethnographic study and semi-structured interviews. These codes were ultimately grouped into 7 core themes, which clearly outline the practices, strategies, conflicts, and adaptation patterns of Chinese young bloggers in the platformized environment (see Table 3).

4 Results

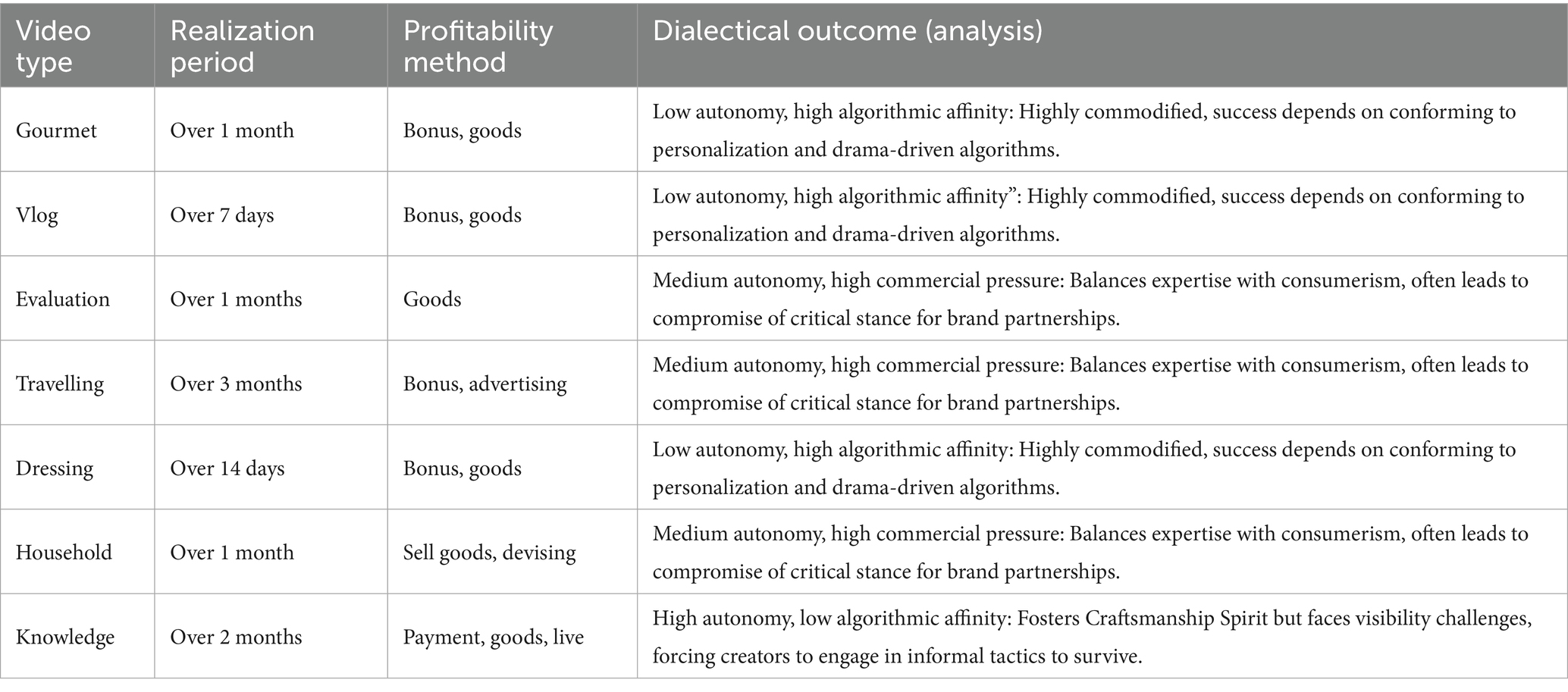

Throughout interview and participatory observation, both common creation types that young bloggers choose and their cash-in models are visible (see Table 4).

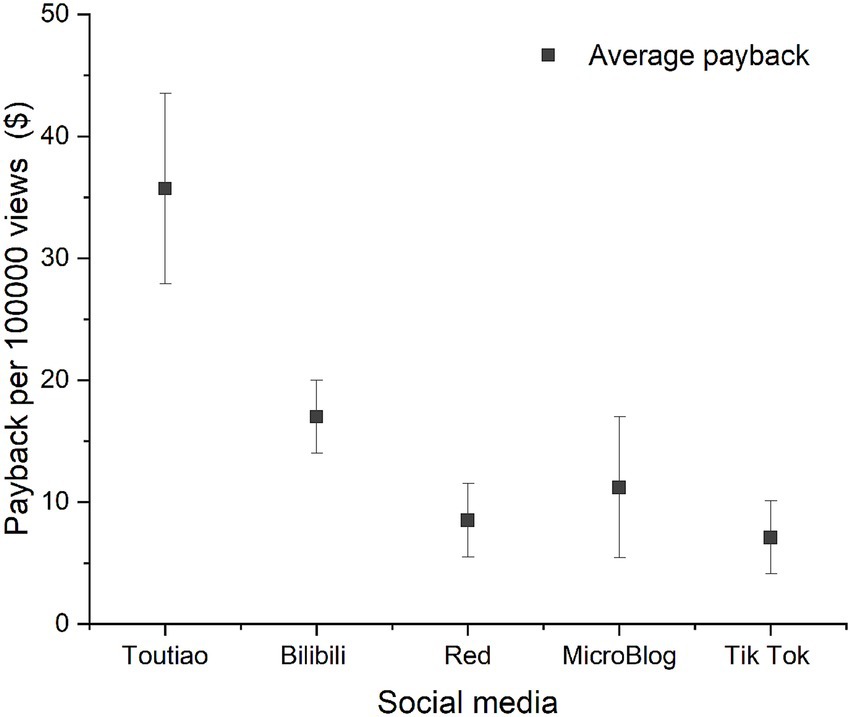

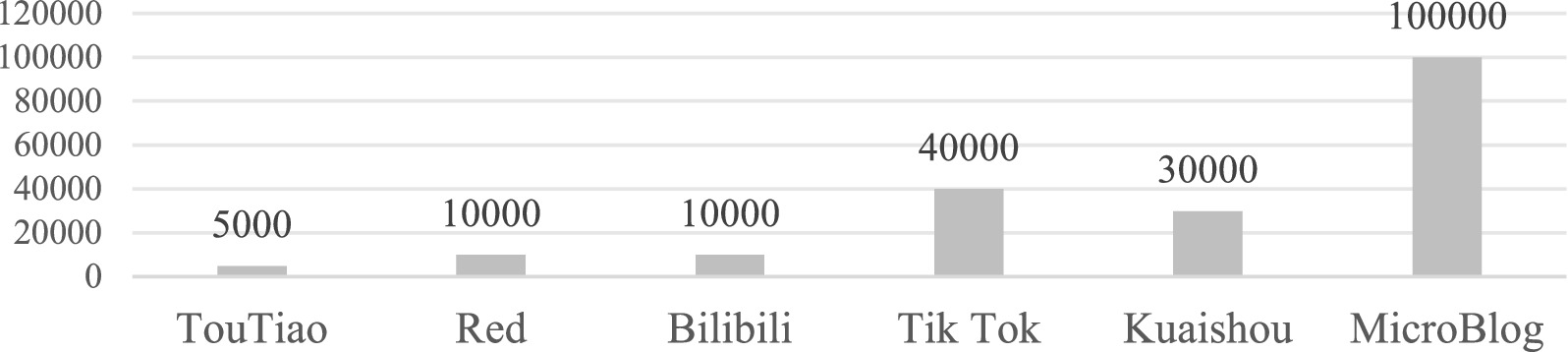

And, the proceeds of commercial advertisements and live streaming rewards need to be shared with media platform side, in which bloggers only get 35–40% of commercial ads fee and about 30% from live streaming. Whereas the amount of platform incentive money is positively correlated with the number of video broadcasts, the cost of commercial order advertising is positively correlated with the bloggers’ fan base (i.e., the number of users retained for the platform). As well, the cost of commercial advertising is based on high broadcast volume and high follower counts, across different social media platforms, each work with 100,000 broadcasts earns $0–50 (see Figure 1). And in order to earn 1,000 commercial advertising dollars for a single video, the blogger should have followers range from 10,000 to 100,000 (see Figure 2).

Here in, the research has found four critical subsections that characterize the labor dynamics within which young bloggers navigate their identities as digital platform defenders. These dynamics are driven by informal practices and content narrative, illustrating how Chinese social media impose identity disciplining at the creative labor level.

Our analysis reveals how digital craftsmanship spirit emerges through creators’ tactical engagement with platform constraints. This practice manifests most vividly in creators’ own narratives. As Blogger-E reflected, “I do not just chase views—I’m cultivating a ‘digital garden’ where I can refine my thoughts. This process of polishing content provides spiritual sustenance amidst the commercial pressure.” Such metaphors of cultivation and craft recurred across interviews, particularly among knowledge creators who framed their work as meaningful self-expression rather than mere content production.

Our position as empathic insiders revealed nuances that might escape external observation. While documenting mutual-aid groups, we noted how participants emphasized relational obligations alongside strategic benefits (Nazari and Karimpour, 2022). As one creator explained, “Helping others in our ‘warm-up’ group is not just about numbers—it’s about maintaining reputation and reciprocity.” This insider perspective helped us recognize how social capital operates within these tactical spaces.

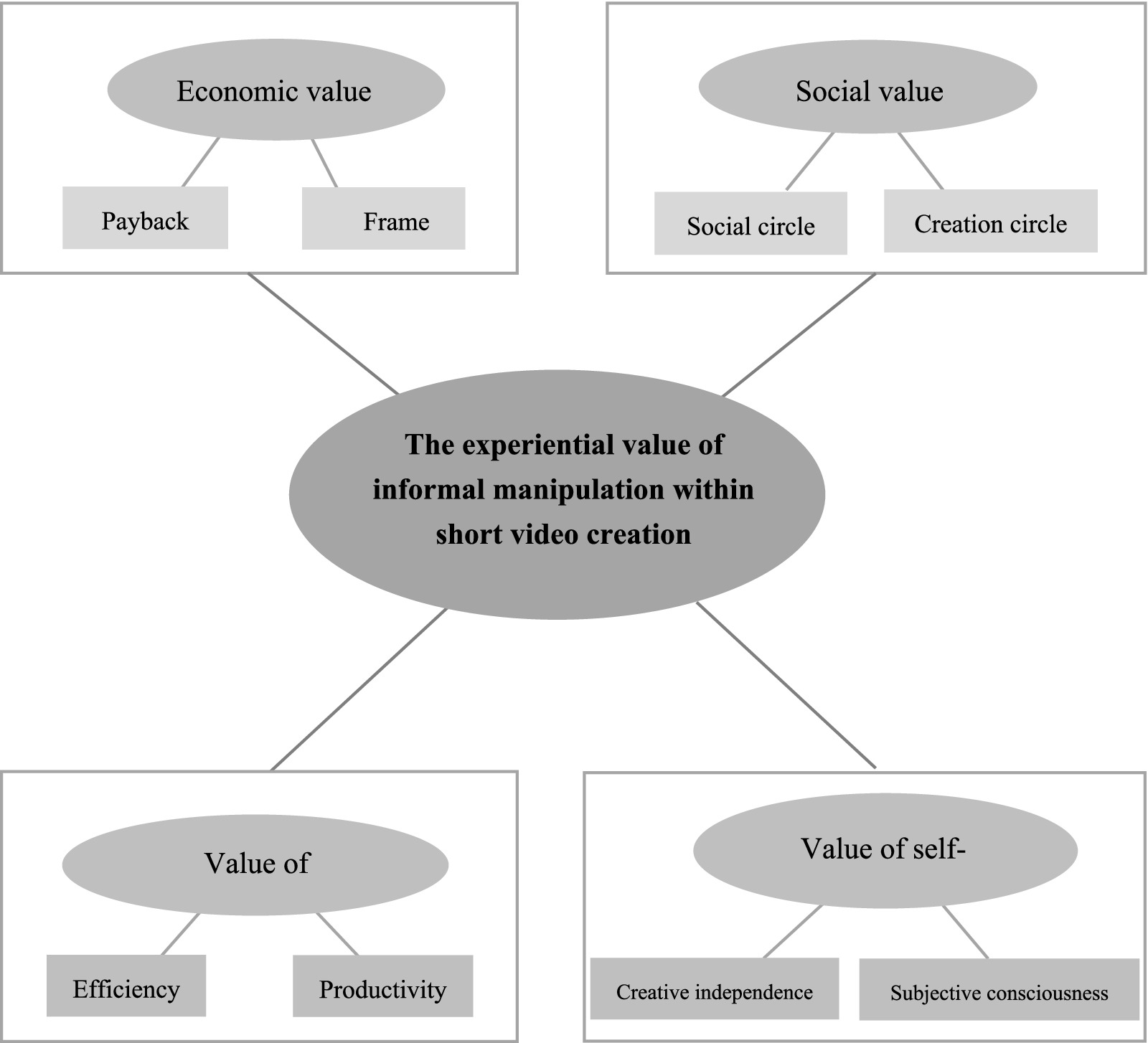

The multidimensional value framework (Figure 3) illustrates how craftsmanship integrates four interconnected domains: economic viability enables social connection, which facilitates information exchange, ultimately supporting self-actualization. As Blogger-C noted, “The income lets me sustain this work, but the community feedback is what pushes me to improve my craft.” This empirical evidence demonstrates how digital craftsmanship represents a holistic adaptation to platform environments, where tactical survival and meaningful creation become mutually constitutive rather than contradictory pursuits.

Figure 3. A dimensional model of the value of young bloggers’ informal practices within social media creation.

The findings reveal a dialectical dynamic where bloggers’ informal manipulations simultaneously reinforce and resist platform systems they operate within. The struggle reflects their effort to assert agency where often commodifies their contributions. Thus, the relationship between bloggers and social media is characterized by both dependence on algorithmic structure and negotiation for creative freedom. This section presents three core arguments: (1) the emergence of a culturally-inflected practice we term “digital craftsmanship spirit” as a distinct response to platform alienation; (2) the co-constitutive relationship between grassroots tactics and platform evolution; and (3) the unique operation of this dialectic under Chinese state-market hybrid governance, or “disciplined innovation.”

4.1 Digital craftsmanship spirit: self-cultivation as resistance and reconciliation

Moving beyond established frameworks of affective labor (Nazari and Karimpour, 2022) or hope labor (McNeill, 2021), which often emphasize the exploitation of emotional capacity or the investment in future potential, this study identifies digital craftsmanship spirit as a practice focused on present-moment self-cultivation and community-building. This concept is empirically grounded in creators’ narratives and practices that blend productive labor with confucian-inspired values of moral and personal development.

The digital craftsmanship spirit manifests not in opposition to algorithmic labor but through it. Blogger-E, a knowledge creator, described the process as “polishing content,” a term imbued with craftsmanship connotations of patience and mastery. He stated, “It’s not just about chasing views. For me, it’s about building a ‘digital garden’ where I can refine my thoughts and connect with a like-minded community. This process is a form of ‘spiritual sustenance’ amidst the pressure to perform.”

This pursuit of “spiritual sustenance” through creative practice represents a significant departure from Western narratives of pure resistance or burnout. It is a strategy of productive adaptation that generates value for the platform while providing the creator with a sense of purpose and identity that mitigates the alienation of metric-driven labor. The value derived from this practice, as Figure 3 illustrates, is multidimensional, encompassing not just economic but also social, informational, and self-actualization values, with the latter being a key differentiator from hope labor.

4.2 The dialectics of informal manipulations: co-opting and co-constituting platformization

The second argument is that informal tactics are not merely resistance but are co-constitutive of platform evolution in Chinese ecosystem. Platforms like Tiktok and Bilibili are not static entities, they adapt their algorithms and policies in response to widespread creator tactics.

A prime example is the practice of “hugging warming” (It refers to a mutual assistance practice among bloggers, where they help one another increase metrics such as the number of views, likes, comments on their respective works, as well as the popularity of their accounts.). While observed as a form of collective resistance to algorithmic opacity, it simultaneously generates immense data value and trains the platform’s AI (Ouvrein, 2024; Verhoef et al., 2022). Blogger-C explained: “We have groups where we instantly share new posts to get those first likes and comments. This ‘jump-starts’ the algorithm’s recommendation mechanism. Without this, even good content might sink.” This practice directly feeds the platform’s need for engagement metrics, making resistance a resource for platform growth.

From the perspective of social interaction, mutual aid digital games such as “hugging warming” enable bloggers to inadvertently construct a digital social network atop the platform, which encapsulates both the direct transfer of genuine social relationships and the newly emerged interactions. These social relationships can be solidified by the ongoing evolution of platform-centric social behaviors. The nature of social relationships has shifted from tangible communities to virtual network platforms (like the blogger E, etc.). Hence, bloggers become the “drivers” of social connections within short video media, motivated by the realization of creativity and engagement. The informal practices of these bloggers further compel platforms to initiate environmental maintenance protocols, resulting in the establishment of community norms which serve as a form of shaping mediated community relations.

4.3 Navigating “disciplined innovation”: craftsmanship spirit within a state-market hybrid

These practices within the unique context of Chinese “disciplined innovation” (Zhou and Liu, 2024). Bloggers must navigate a dual constraint: the market-driven logic of the platform and the state-led ideological framework.

This forces a specific form of compromise that goes beyond Western content. Bloggers internalize the need for “positive energy.” Blogger-D, a travel vlogger, stated: “I never talk about sensitive topics. It’s not just about rules. It’s about understanding the ‘mood’ of the platform. Content with ‘positive energy’ gets promoted. It’s an unspoken rule we all learn to work with.”

This is not mere compliance but a tactical internalization of state discourse to ensure survival and visibility. The practice of digital Craftsmanship spirit thus unfolds within strictly defined boundaries. Creators cultivate their “gardens” and find “sustenance,” but they do so by carefully tilling soil that has been pre-approved by both capital and the state. This finding challenges purely market-centric analyses of platform labor and underscores the critical importance of integrating Chinese political and cultural scholarship to fully understand the local manifestations of global platform dynamics (Vera et al., 2019; Deng et al., 2023).

In short, the experiential value of informal practices in creation by young bloggers can be depicted in four dimensions: economic value, social value, informational value, and self-actualization value.

5 Discussion and conclusion

This study provides a nuanced understanding of short video media dynamics by framing content creation as a form of infrastructure that shapes user behavior and platform evolution. While previous research has emphasized the role of external factors—such as regulations and technological frameworks—in influencing user interactions (Matsuzaka et al., 2023; Davidson and Joinson, 2021), this study introduces the notion that the creative initiatives of bloggers, particularly those seeking fame and monetary rewards, are pivotal in driving platform dynamics.

By examining the role of young bloggers operating with informal technologies, the study highlights how their social manipulations and content strategies contribute to the overall ecology of social media (Yalın, 2024; Salamon and Saunders, 2024). The concept of platform capital is introduced, emphasizing that the motivations and actions of these bloggers are integral to how platforms function and evolve. Unlike traditional perspectives that focus solely on the regulatory or structural aspects of platforms, this study argues that the bloggers’ intrinsic drive and creative output directly influence the nature of user engagement and the character of the platform itself.

5.1 Theoretical implications: advancing platform labor studies

This study set out to investigate how young Chinese bloggers navigate platform constraints through informal manipulations and what these practices reveal about the broader dynamics of platformization (Cho et al., 2024). The finding make three central contributions to the literature on digital labor and platform studies.

First, This study introduces and empirically ground the concept of digital craftsmanship spirit. It moves beyond established frameworks such as affective labor (managing emotions for a wage) and hope labor (working for exposure and future potential) by capturing a more holistic, culturally-nuanced practice of self-cultivation. Whereas affective and hope labor often center on exploitation and futurity, craftsmanship describes a present-focused strategy of finding meaning, community, and skill mastery within the alienating conditions of platform labor. It is a form of productive resilience that helps explain why individuals persist in precarious creative work, not solely due to economic necessity or false hope, but also through the active creation of intrinsic value. This concept provides a new lens for understanding the sustainability of creator economies, particularly in non-Western contexts.

Second, this analysis strengthens the theoretical framework for studying platformization by fusing affordance theory with the “content as infrastructure” perspective (Verhoef et al., 2022). We demonstrate that creator tactics are not just about using platform features (affordance) but about actively repurposing and reassembling them into a grassroots infrastructure that supports their survival. This informal infrastructure—built on mutual aid, data gaming, and community norms—exists in a dialectical relationship with the formal platform infrastructure, simultaneously depending on it and subverting its control mechanisms. This integrated lens offers a more coherent and dynamic model for analyzing the co-constitutive nature of platform evolution.

Third, this study explicitly position Chinese “disciplined innovation” not merely as a context but as an active agent in this dialectic. The findings show that platform governance is a hybrid of state ideological goals and market capitalist extraction. Creators must innovate and resist within a tightly disciplined field, leading to a unique form of platformization that is shaped by both bottom-up tactics and top-down political control. This challenges the applicability of purely Western, market-centric models of platform studies and underscores the necessity of incorporating geopolitical and cultural specificity into global theories of digital labor.

5.2 Practical and policy implications

The findings also yield actionable insights for multiple stakeholders.

For Creators: This study validates and articulates the informal practices many creators already employ. Understanding these tactics as a form of “craftsmanship” can provide a framework for communities to consciously foster more sustainable and mutually supportive practices, mitigating burnout and alienation.

For Platform Operators: The dialectical nature of informal manipulations presents both a challenge and an opportunity. While practices like “hugging warming” can be seen as gaming the system, they also generate immense value and train algorithms. Platforms could engage more transparently with creator communities to develop fairer revenue-sharing models and co-design features that reduce the need for covert resistance, leading to a healthier ecosystem.

For Policymakers: In China and similar contexts, recognizing social and economic value of the creation economy is crucial. Regulations aiming to maintain ideological control should also consider the precarity of digital labor. Policies that provide creators with better social safety nets and more transparent content governance frameworks could help harness their innovative potential while ensuring greater stability.

5.3 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that chart a course for future research. First, while our purposive sampling captured diverse voices, it underrepresented creators from lower-tier cities and those who have failed or quit, potentially overlooking important dimensions of platform precarity. Second, the ethnographic focus on tactics provides deep qualitative insights but cannot quantify the prevalence of these practices at scale. Future research should combine large-scale surveys with computational methods to track the evolution of informal tactics across platforms.

Furthermore, the concept of “digital craftsmanship spirit” warrants further investigation. Comparative studies between Chinese and Western creators could explore the cultural specificity of this concept—is it a uniquely Confucian response, or a universal strategy manifesting differently across cultures? Longitudinal research is also needed to examine how craftsmanship spirit evolves over a creator’s lifecycle and in response to major platform algorithm updates.

5.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study moves beyond simplistic narratives of exploitation and resistance in the platform economy. Through a robust critical ethnography, we have revealed the complex reality where young Chinese bloggers, through their informal manipulations, become unwitting co-architects of the platform ecosystem. Their practices of digital craftsmanship spirit represent a profound adaptation to algorithmic alienation, one that seeks meaning and community within the machine. Ultimately, the Chinese model of platformization is forged in the tension between this grassroots agency and the overarching framework of “disciplined innovation.” By taking these informal practices seriously, we gain not only a more nuanced understanding of the Chinese digital landscape but also a new set of theoretical tools—centered on dialectics, infrastructure, and artistry—for critiquing and reimagining the future of creative labor globally.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans as the studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WY: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Atanasova, A., Eckhardt, G. M., and Laamanen, M. (2025). Platform cooperatives in the sharing economy: how market challengers bring change from the margins. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 53, 419–438. doi: 10.1007/s11747-024-01042-9

Avalle, M., Di Marco, N., Etta, G., Emanuele, S., Shayan, A., Anita, B., et al. (2024). Persistent interaction patterns across social media platforms and over time. Nature 628, 582–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07229-y

Bhandari, A., and Bimo, S. (2022). Why’s everyone on TikTok now? The algorithmized self and the future of self-making on social media. Soc. Media Soc. 8, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/20563051221086241

Bishop, S. (2025). Influencer creep: how artists strategically navigate the platformisation of art worlds. New Media Soc. 27, 2109–2126. doi: 10.1177/14614448231206090

Boscarino, J. E. (2022). Constructing visual policy narratives in new media: the case of the Dakota access pipeline. Inf. Commun. Soc. 25, 278–294. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2020.1787483

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brucks, M. S., and Levav, J. (2022). Virtual communication curbs creative idea generation. Nature 605, 108–112. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04643-y

Büchi, M., and Hargittai, E. (2022). A need for considering digital inequality when studying social media use and well-being. Soc. Media Soc. 8, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/20563051211069125

Burai, K., Solti, Á., and Bene, M. (2024). Feel local, post local: an ethnographic investigation of a social media-based local public. New Media Soc. 0:14614448241262988. doi: 10.1177/14614448241262988

Cho, H., Cannon, J., Lopez, R., and Li, W. (2024). Social media literacy: a conceptual framework. New Media Soc. 26, 941–960. doi: 10.1177/14614448211068530

CNNIC (2024). 54th Statistical Report on the Development of China’s Internet. China Internet Network Information Center 54, 35–53.

Crain, M. (2018). The limits of transparency: data brokers and commodification. New Media Soc. 20, 88–104. doi: 10.1177/1461444816657096

Davidson, B. I., and Joinson, A. N. (2021). Shape Shifting Across Social Media. Social Media + Society, 7, 102-123. doi: 10.1177/2056305121990632

Deng, X., Taylor, J., and Joshi, K. D. (2023). To speak up or shut up? Revealing the drivers of crowdworker voice behaviors in crowdsourcing work environments. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 53, 1003–1027. doi: 10.17705/1CAIS.05343

Duffy, B. E., and Meisner, C. (2023). Platform governance at the margins: social media creators’ experiences with algorithmic (in) visibility. Media Cult. Soc. 45, 285–304. doi: 10.1177/01634437221111923

Duffy, B. E., Poell, T., and Nieborg, D. B. (2019). Platform practices in the cultural industries: creativity, labor, and citizenship. Soc. Media Soc. 5, 76–89. doi: 10.1177/2056305119879672

Fan, J. (2024). In and against the platform: navigating precarity for Instagram and Xiaohongshu (red) influencers. New Media Soc. 0:14614448241270434. doi: 10.1177/14614448241270434

Guarriello, N.-B. (2019). Never give up, never surrender: game live streaming, neoliberal work, and personalized media economies. New Media Soc. 21, 1750–1769. doi: 10.1177/1461444819831653

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Habermas, J. (2022). Reflections and hypotheses on a further structural transformation of the political public sphere. Theory Cult. Soc. 39, 145–171. doi: 10.1177/02632764221112341

Ho, M., Huyen, N. T. T., Nguyen, M., La, V., and Vuong, Q. (2022). Virtual tree, real impact: how simulated worlds associate with the perception of limited resources. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 213–245. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01225-1

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling : University of California Press.

Jiang, L., Deng, X., and Christian, W. (2024). Understanding the individual labor supply and wages on digital labor platforms: a microworker perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 79:102823. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2024.102823

Kaye, D. B. V., Chen, X., and Zeng, J. (2021). The co-evolution of two Chinese mobile short video apps: parallel platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mobile Media Commun. 9, 229–253. doi: 10.1177/2050157920952120

Khelladi, I., Castellano, S., Hobeika, J., Perano, M., and Rutambuka, D. (2022). Customer knowledge hiding behavior in service multi-sided platforms. J. Bus. Res. 140, 482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.017

Kreiss, D., and McGregor, S. C. (2024). A review and provocation: on polarization and platforms. New Media Soc. 26, 556–579. doi: 10.1177/14614448231161880

Li, L. (2024). The specter of global ByteDance: platforms, regulatory arbitrage, and politics. Inf. Commun. Soc. 27, 2005–2021. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2024.2352634

Madison, D. S. (2019). Critical ethnography: Method, ethics, and performance. 3rd Edn: SAGE Publications.

McNeill, D. (2021). “Fetishism of Money, Capital, Interest-Bearing Capital and Commodities” in Fetishism and the Theory of Value: Reassessing Marx in the 21st Century (Palgrave Macmillan), 151–175.

Matsuzaka, S., Avery, L. R., and Stanton, A. G. (2023). Black women’s social media use integration and social media addiction. Soc. Media Soc. 9:20563051221148977. doi: 10.1177/20563051221148977

Nazari, M., and Karimpour, S. (2022). The role of emotion labor in English language teacher identity construction: an activity theory perspective. System 107:102811. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102811

Nieborg, D. B., and Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 20, 4275–4292. doi: 10.1177/1461444818769694

Ouvrein, G. (2024). Followers, fans, friends, or haters? A typology of the online interactions and relationships between social media influencers and their audiences based on a social capital framework. New Media Soc. 27, 5659–5690. doi: 10.1177/14614448241253770

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. 4th Edn: Sage Publications.

Plantin, J.-C., Lagoze, C., Edwards, P. N., and Sandvig, C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. Big Data & Society 5. doi: 10.1177/205395171878137

Popiel, P., and Vasudevan, K. (2024). Platform frictions, platform power, and the politics of platformization. Information, Communication & Society 26, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2024.2300361

Pronzato, R. (2024). Algorithms of resistance: the everyday fight against platform power. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Salamon, E., and Saunders, R. (2024). Domination and the arts of digital resistance in social media creator labor. Soc. Media Soc. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/20563051241269318

Treré, E., and Yu, Z. (2021). The evolution and power of online consumer activism: illustrating the hybrid dynamics of “consumer video activism” in China through two case studies. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 65, 761–785. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2021.1965143

Tsang, E. Y. H., and Wilkinson, J. S. (2025). Hope for the forgotten poor: Chinese male migrants, affective labor and the livestreaming industry. Front. Sociol. 10:1640234. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1640234

Vera, L. A., Walker, D., Murphy, M., Mansfield, B., Siad, L. M., and Ogden, J. (2019). When data justice and environmental justice meet: formulating a response to extractive logic through environmental data justice. Inf. Commun. Soc. 22, 1012–1028. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1596293

Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Dong, J. Q., Fabian, N., et al. (2022). Digital transformation: a multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 122, 889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

Yalın, A. (2024). Governing the resilient self: influencers’ digital affective labor in quarantine vlogs. Soc. Media Soc. 10, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/20563051241247749

Keywords: Chinese social media, platformisation, empirical research, content narrative, digital craftsmanship

Citation: Yue W (2025) Digital craftsmanship spirit: informal tactics and the negotiation of platform power in China. Front. Commun. 10:1661101. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1661101

Edited by:

Prahastiwi Utari, Universitas Sebelas Maret, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Maulana Rezi Ramadhana, Telkom University, IndonesiaEka Nada Shofa Alkhajar, Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

Pramana Pramana, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Yue. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenwen Yue, MjAyMzEwMTMwMXozMTU0QG1haWxzLmN1Yy5lZHUuY24=

Wenwen Yue

Wenwen Yue