- Institute for Communication Studies, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

This paper explores the construction of masculinity and femininity in misogynic hate communication through the lens of Membership Categorization Analysis, focusing on language use and the interrelations of sexuality, violence, and power dynamics in collaborative storytelling. Analyzing German-language online interactions where male participants role-play both male and female characters, the study examines how gendered narratives are co-constructed and maintained. Findings indicate that male characters’ responses are largely unaffected by female autonomy assertions, suggesting a disregard for female agency, as male mistreatment appears consistent regardless of female actions. However, significant associations were found between male dominance assertion and dehumanizing language, as well as between sexualized language and scenes involving power struggles, highlighting a thematic connection between sexuality, control, and dehumanization in reinforcing gendered hierarchies. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of misogynic communication, revealing how linguistic practices support toxic masculinity and perpetuate gender inequality, with implications for digital policy and moderation strategies aimed at fostering inclusivity in online spaces.

1 Introduction

The rise of online communities has profoundly shaped modern social dynamics, particularly in how individuals construct and express identities related to gender and power (Douglas, 2012). Among these communities, groups associated with misogynic hate communication—a term used here to describe toxic, misogynistic rhetoric commonly found in digital spaces (Gilmore, 2001)—have garnered increasing attention due to their promotion of extreme forms of incivility (Papacharissi, 2004; Blom et al., 2014). Misogynic hate communication represents an extreme form of incivility as gendered online hostility that delegitimizes and excludes women from public discourse through objectification and dehumanization (Ging and Siapera, 2018; Fontanella et al., 2024; Dutta et al., 2025). These online echo chambers reinforce (cf. Kanz, 2021; Colleoni et al., 2014) harmful beliefs about gender roles, power dynamics, and interpersonal relationships (Jaki et al., 2019) while also reflecting broader societal issues tied to toxic masculinity and the systemic subordination of women.

These patterns are particularly evident in the so-called manosphere—a loosely connected constellation of online communities that promote antifeminist and misogynic ideologies (Ging, 2019). Within this network, discourses of male entitlement, resentment toward women, and rejection of feminist perspectives are not only normalized but celebrated as forms of authenticity and resistance (Aiston, 2024). The manosphere thus serves as a contemporary breeding ground for incivility and toxic masculinity, providing ideological and discursive frameworks that reinforce gendered hierarchies and hostility toward women (Barnes and Karim, 2025; Franklin-Paddock et al., 2025). Public figures such as Andrew Tate exemplify how these narratives have moved from fringe communities into mainstream digital culture, where hypermasculinity and the rejection of female autonomy are presented as aspirational ideals (Wescott et al., 2024). By situating misogynic hate communication within this broader socio-digital context, the present study connects its findings to ongoing cultural developments that shape public perceptions of gender and power in the digital age.

Understanding the narratives and discourses within misogynic hate communication is crucial for several reasons. First, these narratives perpetuate toxic masculinity, a construct characterized by dominance, emotional repression, and aggression as defining traits of manhood (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005). Such constructions reinforce hegemonic masculinity, which upholds male dominance and legitimizes the subordination of women as societal norms. Secondly, the portrayal of women within these narratives often involves objectification and dehumanization, which normalize and justify aggression towards women (Jane, 2014). The exclusionary nature of this rhetoric aligns with incivility studies, which highlight how certain forms of speech can undermine democracy by excluding certain groups from meaningful participation (Anderson et al., 2014; Ziegele et al., 2018).

Additionally, misogynic hate communication has real-world implications, as evidenced by its association with acts of violence (Baele et al., 2021). These acts, while extreme, draw attention to the broader ideological patterns in online communities that seek to exclude and dehumanize women, thereby threatening democratic principles and undermining social cohesion (Waltman and John Haas, 2011). Thus, examining the construction of gender within these narratives not only reveals how toxic masculinity is reproduced and reinforced but also highlights the dangers posed by this form of incivility to society at large (Lück and Nardi, 2019).

This study explores the construction of masculinity and femininity within the context of misogynic hate communication by analyzing interactive communications—specifically collaborative storytelling (Bührig, 2002; Meiler, 2021) between male participants. Using a Membership Categorization Analysis (Sacks, 1972; Fitzgerald and Housley, 2015) of German-language online communications, this study aims to uncover patterns related to sexuality, violence, and power dynamics. The findings offer insights into how misogynic hate communication perpetuates harmful gender stereotypes and contributes to the normalization of incivil behavior towards women, with significant implications for democratic discourse, gender relations, and online community dynamics. The central research question guiding this study is how masculinity and femininity are constructed in misogynic hate communication through language use and what relationships exist between depictions of sexuality, violence, and power dynamics in collaborative storytelling between male participants. By situating the analysis within a German-speaking context, the study provides a comparative perspective that highlights cultural nuances in misogynic hate communication, contributing to the global discourse on incivility, gender extremism, and online communities.

2 Construction of masculinity and femininity in misogynic hate communication

The phenomenon of misogynic hate communication has increasingly attracted attention in both popular media and academic discourse due to its promotion of harmful, exclusionary narratives that undermine democratic discourse. Misogynic hate communication, particularly in online spaces, often revolves around the frustration of predominantly male individuals who feel disenfranchised in romantic or sexual relationships (Gilmore, 2001). They attribute this perceived injustice to societal structures and, more specifically, to women, whom they blame for their lack of fulfillment (Kimmel, 2015). These digital spaces, much like echo chambers, reinforce harmful ideologies about gender roles, sexuality, and power dynamics (Jaki et al., 2019). The narratives found in these communities frequently reflect incivility (Bormann et al., 2022), as they aim to exclude women from discourse (Marx, 2017; Sagredos and Nikolova, 2022) through derogatory stereotypes (Kalch and Naab, 2017) and violent rhetoric (Hurt and Grant, 2019), both forms of communicative practices that threaten democratic values (Papacharissi, 2004).

Masculinity in these narratives is frequently constructed around themes of dominance, entitlement, and hostility toward women (Ging, 2019). These constructions reflect hegemonic masculinity, a framework where masculinity is defined by power, control, and the subordination of women (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005). This toxic form of masculinity is often expressed through communicative units that not only dehumanize women but also celebrate male dominance and aggression (Hatzidaki, 2024). Such behavior aligns with incivility in communication (Coe et al., 2014), as it seeks to exclude women from participating in meaningful discourse, reinforcing harmful social hierarchies and promoting aggression as a legitimate means of asserting male identity (Plummer, 2005).

The core feature of misogynic hate communication is its reliance on stereotypes and narratives that objectify women, portraying them as passive objects to be controlled or punished for failing to meet male expectations (Baele et al., 2021). This portrayal of masculinity, which upholds male aggression and entitlement (Bou-Franch et al. 2016), leads to the normalization of violence and the reduction of women to mere instruments for male gratification (Jane, 2018). The aggressive tone found in these communications often overlaps with incivility, where impoliteness may or may not be present, but the fundamental goal is to marginalize and exclude unwanted subgroups from public discourse (Krug, 2024a).

In misogynic hate communication, femininity is typically constructed through narratives that emphasize passivity, submissiveness, and an intrinsic inferiority to men (cf. Bem, 1981). This construction aligns with traditional gender stereotypes, which position women as lacking agency and autonomy. These narratives not only diminish women’s roles in society but also justify their exclusion from democratic discourse. By framing women as inherently subordinate, misogynic hate communication perpetuates incivility by reinforcing the idea that certain voices—namely, women’s—are not worth hearing or acknowledging (Lück and Nardi, 2019).

Femininity in these narratives is often linked to sexual objectification, where women are valued solely based on their sexual utility to men (Nussbaum, 1995). Such portrayals strip women of their individuality and identity, reducing them to sexualized objects whose sole purpose is to satisfy male desires. This objectification fits into the broader pattern of incivility, as it represents a form of communicative exclusion, where women are denied their full humanity and, as a result, their right to participate in discourse on equal footing (Pahor De Maiti et al., 2023). Moreover, misogynic hate communication often frames female sexuality as dangerous or manipulative, further dehumanizing women and casting them as threats to male identity and control (Baele et al., 2021).

Incivility, as outlined in current research, extends beyond mere rudeness. It includes behaviors that undermine democratic discourse by marginalizing and delegitimizing certain voices (Friess and Eilders, 2015; Krug, 2024b). Misogynic hate communication represents an extreme form of incivility in which hate speech, characterized by insults, sarcasm, and aggression (Chovanec, 2023; Geyer et al., 2022), is used to exclude women from discourse and deny them their rights (Bormann and Ziegele, 2023). This form of communication fosters a hostile environment where democratic ideals, such as equality and freedom of expression, are eroded (Dahlberg, 2007).

Collaborative storytelling and role-playing within misogynic hate communication serve as unique members’ methods for enacting and reinforcing these gendered narratives (cf. Brown and Zagefka, 2005). When individuals engage in role-playing, they assume exaggerated or stereotypical characteristics that reflect internalized beliefs and attitudes toward masculinity and femininity (Coyne et al., 2014; Hlalele and Jode Brexa, 2015). In these contexts, misogynic hate communication becomes a space where men rehearse and legitimize their misogynistic ideologies, reinforcing the exclusionary and dehumanizing narratives that underlie incivility (Ging, 2019).

In this interactive format, male dominance and female subservience are continually reaffirmed, with women portrayed as passive subjects to be controlled or dominated (Bem, 1981). This dynamic mirrors real-world gender-based violence, where power and control are used to assert male dominance over women (Johnson et al., 2008; Montiel-McCann, 2024). The violent and aggressive behavior that is often a part of these role-playing exercises aligns with the exclusionary practices of incivility, as it promotes the delegitimization of women and their voices within the broader public sphere (Colleoni et al., 2014).

3 Data collection and Corpus description

The analyzed material consists of an email-based collaborative storytelling exchange originally circulated within a German-language online group. In these interactive narrative exchanges, one participant typically assumed the role of the male characters, while another portrayed the female characters. This role-playing setup enabled the co-creation of stories that provide rich insight into the (co-)construction of masculinity and femininity (Salter and Blodgett, 2012), as well as the dynamics of power and control explored in this study.

At least two participants were involved in the correspondence, though their exact number, age, and demographic characteristics remain unknown. Based on linguistic and stylistic markers, it can be reasonably assumed that the participants were male and that they adopted multiple roles and genders throughout the interaction. The dataset covers a continuous period of communicative activity of slightly more than 1 year, concluding in December 2022. This period coincides with a phase of heightened public debate around online misogyny in German-language digital spaces (Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft »Gegen Hass im Netz«, Textgain, 2024), which provides some socio-temporal context for interpreting the narratives.

The researcher acted as an observing participant in the group; the participants were unaware of the research purpose, as disclosure would have rendered data access impossible. The corpus therefore represents a naturally occurring communicative environment rather than an experimental setting. Because of the limited contextual information, no sociological or demographic inferences can be made about the participants. Instead, the study focuses on how misogynic ideals are linguistically reproduced through the role-play dynamics within this collaborative storytelling environment, offering insight into discursive practices common within the manosphere.

The data include references to sexualized and, in some cases, pedosexual themes, which were not coded or analyzed as they fall outside the scope of this study. The research forms part of the broader project Digital Misogyny in Chat Communication and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities, University of Duisburg-Essen (approval ID: Ethik WS2024-6). All data were anonymized in compliance with ethical and legal standards, and any potentially harmful or identifying excerpts have been withheld from publication.

The data capture process involved manually transferring the email interactions into a text document, which was then converted into a tabular format. An automated procedure segmented each message into individual sentences, resulting in a total of 5,924 sentences. These segmented sentences constitute the primary unit of analysis for the interactionally informed coding process (see next section). Every sentence was attributed to the role of its author (male or female character) based on explicit textual markers such as first-person pronouns, gendered references, or role-specific vocabulary. As there were not any non-character roles (e.g., a narrator), every sentence could be attributed to a character within the storytelling. While each sentence constitutes an independent observation, the analytical focus was not limited to within-speaker variation but rather on distributional co-occurrences of discursive features across the corpus. In other words, the statistical tests examined whether sentences containing one practice (e.g., autonomy assertion by a female character) were more likely to appear in contexts that also included another category (e.g., delegitimizing or violent language used by male characters). This approach does not assume a direct conversational sequence between individual sentences or speakers, but instead captures broader interactional patterns reflected in the overall distribution of linguistic features. Thus, the analyses identify systematic associations between gendered language categories at the corpus level, providing evidence of thematic and interactional tendencies without requiring turn-by-turn conversational data. This approach allows for a systematic examination of how gendered categorizations and power dynamics are constructed across the dataset. The corpus contains explicit material depicting violent and abusive interactions between male and female characters; interpretative analysis of these themes is provided in the Discussion section.

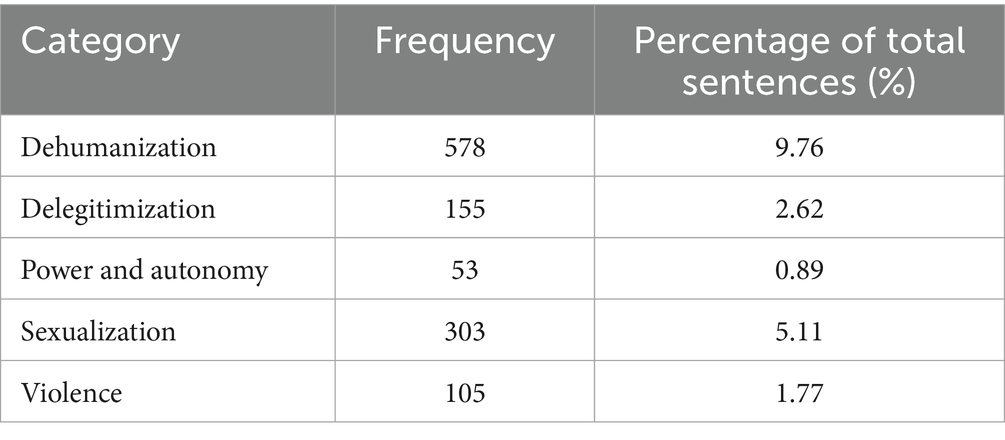

Using Membership Categorization Analysis (MCA, see next section), five principal interpretative categories were identified: dehumanization, delegitimization, power and autonomy, sexualization, and violence. Each sentence could receive multiple category labels. Coding was performed manually in a spreadsheet, supported by contextual notes for each sentence (see next section). Table 1 provides an overview of the category distribution and the relative frequency of each phenomenon across the corpus.

The overview demonstrates that dehumanization and sexualization were the most prominent forms of categorization, reflecting the centrality of these themes within misogynic hate communication.

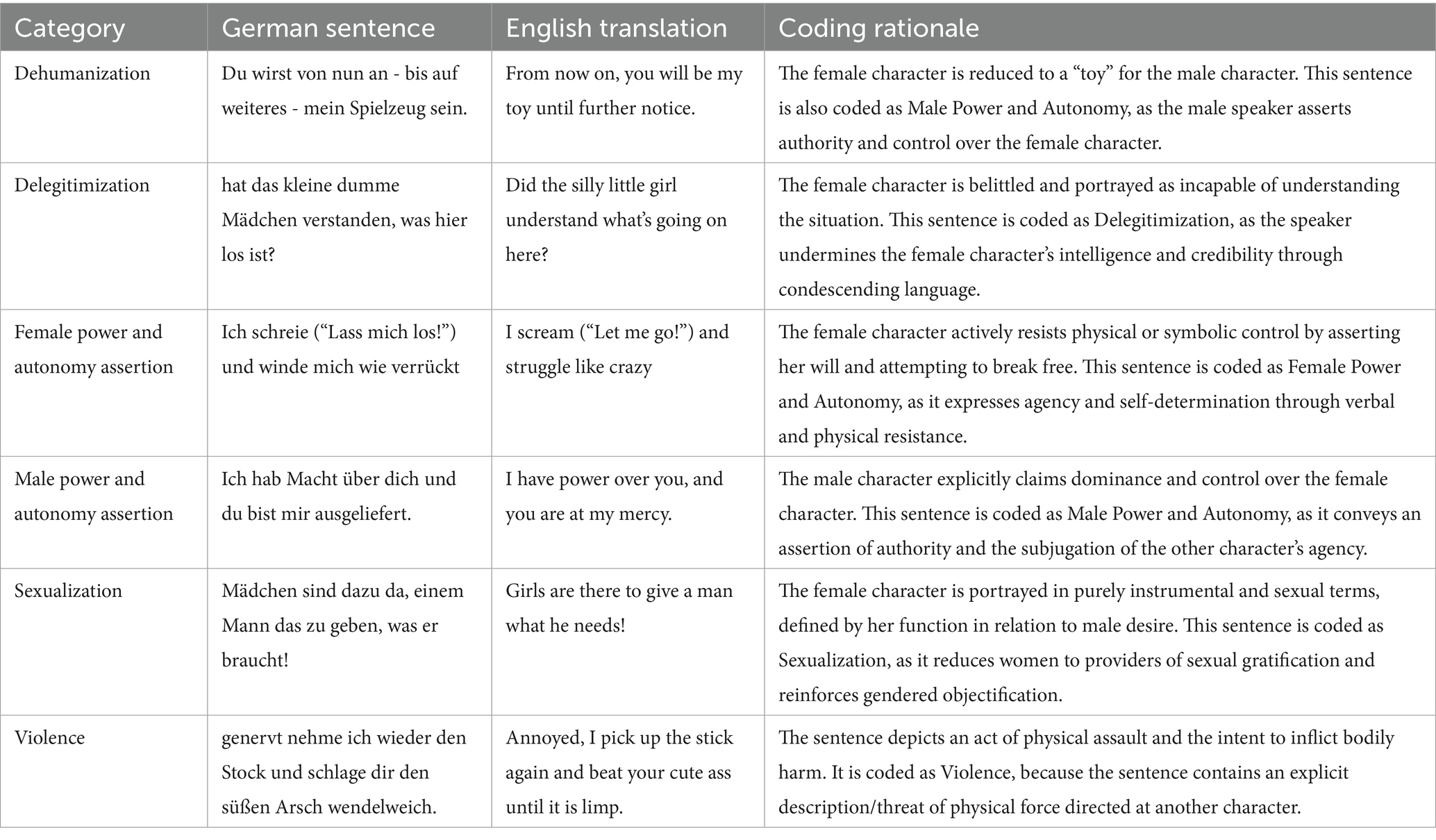

Table 2 presents a set of anonymized example sentences illustrating how the coding scheme was applied across categories (described in the Methods, see next section): a sentence was marked as Female Autonomy Assertion when it contained explicit first-person or agentive claims of agency by a female character; as Male Dominance Assertion when it contained claims of power, control, or ownership attributed to a male character; as Dehumanizing Language when it reduced a target to non-human traits or metaphors; as Delegitimizing Language when it denied competence, credibility, or moral standing; as Sexualization when the sentence depicted the female character primarily in sexual or instrumental terms; and as Violence when it contained explicit threats or descriptions of physical harm.

All 5,924 sentences were manually coded by a single researcher using the five predefined MCA categories. Because of the explicit and legally sensitive nature of the corpus, additional annotators could not be involved. No formal intercoder or intra-coder reliability test was conducted. However, during the preparation of a subsequent qualitative study based on the same dataset, the coding was revisited in depth, and the category assignments were found to be consistent. While this does not substitute for a formal reliability test, it provides an additional form of validation through sustained engagement with the material. The reliance on a single coder is acknowledged as a methodological limitation and discussed further in the limitations section.

4 Methods and hypothesis

4.1 Methodology: membership categorization analysis

Building upon the theoretical framework of misogynic hate communication and incivility, this study employs a Membership Categorization Analysis (MCA) to examine how categories contribute to the portrayal of masculinity and femininity, objectification, and violence within misogynic hate narratives. MCA provides a systematic approach to studying how speakers construct, assign, and negotiate social identities in their discourse. Building on the literature on incivility and especially on the objectification and dehumanization of women, this paper employs MCA to delve deeper into the ways these themes are constructed and reinforced through categorization practices in misogynic hate communication. As Stokoe (2012) emphasizes, MCA enables an exploration of categories not as fixed labels but as dynamic constructs that interactants use to make sense of their social world. In this study, MCA is used to analyze how participants in misogynic hate communication invoke gendered categories to construct and reinforce identities associated with power, objectification, and incivility in online spaces.

Unlike traditional approaches that often focus on sequential structure (i.e., conversation analysis), MCA concentrates on how categories and category-bound activities are used to organize social actions and identities (Housley and Fitzgerald, 2015). This approach is particularly pertinent to analyzing gendered discourse in hate communication, as it allows us to investigate the specific category-bound activities (cf. Sacks, 1972) attributed to men and women, and how these categorizations serve as resources for expressing incivility and justifying gendered exclusion.

The following analysis applies MCA to first inductively identify and later quantify the linguistic categories present in the corpus. Following Sacks’s (1992) foundational work, the primary membership categories within the digital collaborative storytelling are identified, and their associated predicates—e.g., authority for men, objectification for women—are examined to understand their role in identity construction within hate communication. As illustrated by Stokoe and Edwards (2009), categorization practices are analyzed to uncover implied stereotypes and roles that reinforce societal norms. MCA is applied to determine how the male characters in the narrative are frequently categorized as dominant or entitled while the female characters are positioned as passive or inferior, revealing underlying stereotypes that justify incivility in misogynic narratives. Drawing on the work of Eglin and Hester (1999), the unfolding of misogynic hate communication sequences in online conversations is examined. Here, categorization is assessed as a rhetorical tool for rallying support through alignment with shared gendered beliefs. Finally, building on Sinkeviciute’s (2024) insights into category-implicative actions in online joint fantasizing, the co-construction of identities through joint categorization efforts is analyzed.

Using MCA, the following five categories are identified: The first category, dehumanization, captures instances where story participants are portrayed as less than human. This often occurs through comparisons to animals or other non-human entities (e.g., “thing”). The second category, delegitimization, involves language that marginalizes participants, using exclusionary, hostile, or aggressive language designed to undermine their worth or right to participate. A third category, power and autonomy, highlights moments where participants assert their (deontic or epistemic) agency (e.g., Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012), whether by resisting control (Humă et al., 2023), claiming dominance, or exercising rights over their actions, thus emphasizing their independence and control over situations. Another category, sexualization, reduces participants to sexual objects, emphasizing only their physical attributes. Finally, the category of violence includes references to physical harm, aggression, or explicit threats, typically directed at the women in the narrative.

In MCA, the typical aim is to reconstruct categories as the primary focus of the study. In this research, however, identifying the categories marks only the beginning of the analysis, as the goal is to apply a “heretical approach” (Stivers, 2015) of quantification to MCA. To this end, each sentence in the dataset is examined and coded to determine the presence or absence of these categories, creating categorical variables that indicate whether specific categorization devices appear in the text. This approach enables a systematic data organization suitable for statistical analysis while extending MCA’s traditional qualitative focus.

4.2 Hypotheses

Based on these categories analyzed through MCA, the following hypotheses are proposed to investigate how masculinity and femininity are constructed in misogynic hate communication and to understand the interplay of sexuality, violence, and power dynamics in collaborative storytelling. Research on misogynic communication shows that male-dominated spaces often marginalize women through language that diminishes their contributions, especially when they attempt to assert authority (Jane, 2014; Jaki et al., 2019). In this role-playing context, delegitimizing responses serve as a tool for reinforcing traditional power dynamics by positioning masculinity as authoritative and femininity as subordinate (Ridgeway, 2007). Furthermore, literature on violence in misogynic hate speech (e.g., Hurt and Grant, 2019) suggests that aggression is frequently used to enforce submission when gendered hierarchies are challenged (Baele et al., 2021). Within the collaborative storytelling framework (Stivers, 2008; Voutilainen et al., 2014), male characters may respond to challenges by invoking violence (including threats), reasserting control over the female character, and reinforcing toxic masculinity as a default in power dynamics. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Segments that include female autonomy assertions are more likely to also contain (a) delegitimizing or (b) violent language than segments without such assertions.

Sexualization of women in misogynic discourse reduces them to objects defined by physical attributes, aligning with patterns of objectification that reinforce control by positioning women as primarily valuable for their physical appearance (Nussbaum, 1995). In collaborative storytelling, male participants may employ sexualizing language to reinforce traditional gender roles, using objectification as a means of controlling or defining the female character’s role in the narrative (Jane, 2018). In this regard, dehumanizing language in hate communication serves to diminish personhood, often justifying aggression by casting the target as less than human (Pahor De Maiti et al., 2023; Sagredos and Nikolova, 2022). In this context, the female character’s resistance to male authority may trigger dehumanizing descriptors from the male character, reinforcing the notion that masculinity is entitled to dominance while femininity is subordinated, particularly when non-compliant (Ging, 2019; Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005). As a result, the following hypothesis is introduced:

Hypothesis 2: Male dominance assertions tend to co-occur with language that (a) sexualizes or (b) dehumanizes female characters within the same narrative segments.

Studies on gendered communication highlight how sexuality is often intertwined with power (Hlalele and Jode Brexa, 2015), particularly in discourses that objectify and control women (Nussbaum, 1995; Ging, 2019). In collaborative storytelling, sexualized language used during power conflicts (Schumann and Steve Oswald, 2024; Humă et al., 2023) may reflect an underlying association between female sexuality and male dominance, positioning femininity as submissive to masculine control. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is put forward:

Hypothesis 3: Sexualizing language is more likely to occur in contexts that also involve references to power struggles, reflecting an association between sexuality and control.

5 Analysis

The study tested three hypotheses regarding male character responses in narratives involving female characters’ assertions of autonomy, focusing on whether such responses involved different forms of negative language. To examine associations between the coded categories, chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted on the sentence-level data. Each sentence served as a unit of observation, coded for the presence or absence of relevant linguistic and thematic features (e.g., delegitimizing language, autonomy assertion, violence). Because each sentence is attributed to one character, the analyses do not assess direct responses between speakers but rather test whether these discursive features tend to co-occur across the same corpus segments, reflecting broader interactional tendencies.

Because several contingency tables were highly unbalanced, with expected frequencies below 5, Fisher’s exact test was applied instead of the chi-square test of independence for these comparisons. Tables 3–5 present both the observed and expected frequencies for each hypothesis. The imbalance in certain categories (i.e., violence and autonomy) is acknowledged as a limitation and is further discussed in the Discussion section.

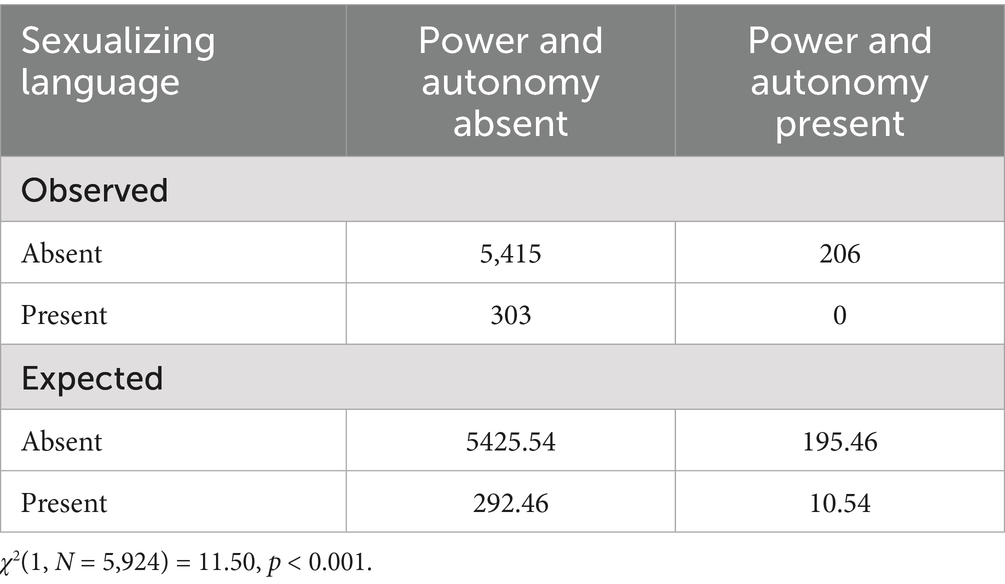

Hypothesis 1 proposed that segments containing female autonomy assertions are more likely to also include (a) delegitimizing or (b) violent language than segments without such assertions. To evaluate Hypothesis 1a, Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the relationship between the presence of female power and autonomy assertions and the occurrence of delegitimizing language (see Table 3).

Table 3. Observed and expected frequencies for female power and autonomy × delegitimizing and violence language.

Results showed no statistically significant association between female characters’ assertions of power and autonomy and the use of delegitimizing language, Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) p = 1.00. Observed and expected frequencies closely aligned, indicating no meaningful deviation from independence. This finding suggests that delegitimizing language was not systematically affected by female characters asserting power and autonomy, and Hypothesis 1a is therefore not supported.

Second, Hypothesis 1b proposed that male characters would respond with violent language when female characters asserted power and autonomy. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) revealed no statistically significant association between the two variables (p = 0.61; see Table 3). Observed and expected frequencies closely aligned, indicating no deviation from independence. The likelihood of violent responses by male characters was therefore not influenced by female autonomy and power assertion, and Hypothesis 1b is not supported.

In summary, Hypothesis 1 was not supported across the two components, indicating that male characters’ responses involving delegitimizing language or violence do not differ significantly in the presence of female power and autonomy assertions.

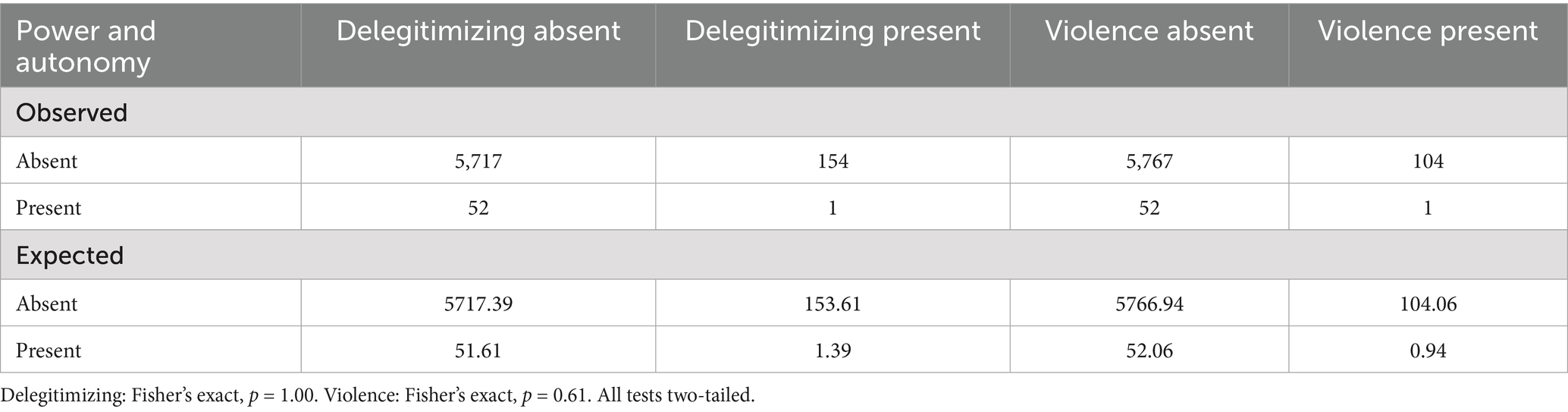

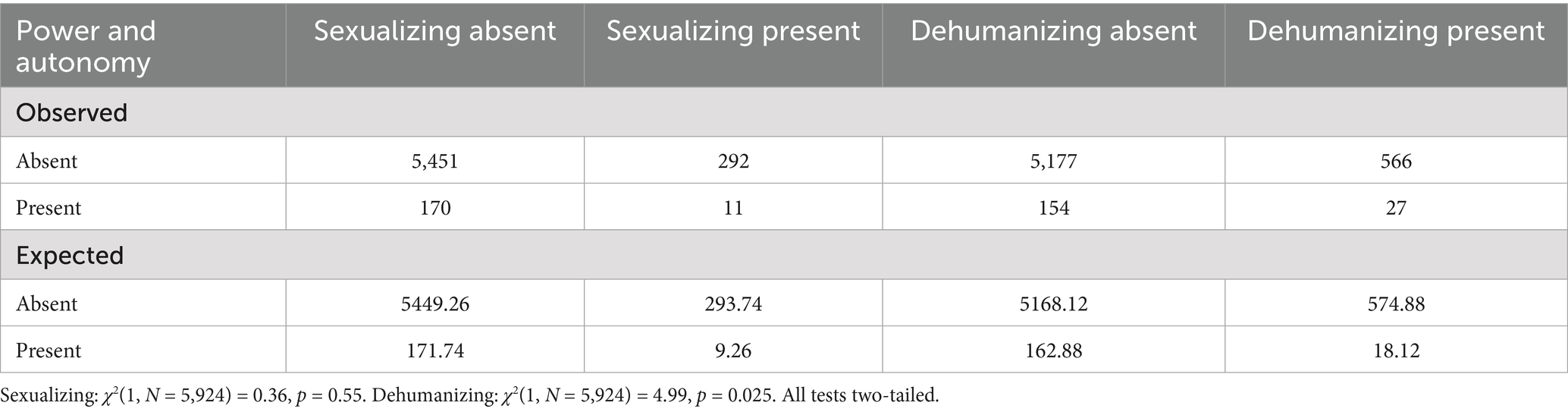

Hypothesis 2 explored whether male dominance assertions tend to co-occur with language that (a) sexualizes or (b) dehumanizes female characters within the same narrative segments (see Table 4).

Table 4. Observed and expected frequencies for male power and autonomy × sexualizing and dehumanizing language.

For Hypothesis 2a, a chi-square test assessed the association between male power and autonomy assertion and sexualizing language, yielding no significant results, χ2(1, N = 5,924) = 0.36, p = 0.55. Observed and expected frequencies closely aligned, indicating no deviation from independence. These findings suggest that male power and autonomy assertion was not associated with an increase in sexualizing language, and Hypothesis 2a is therefore not supported.

For Hypothesis 2b, which proposed a link between male power and autonomy assertion and the use of dehumanizing language, a chi-square test of independence revealed a statistically significant association, χ2(1, N = 5,924) = 4.99, p = 0.025 (see Table 4). When male power and autonomy were asserted, dehumanizing language occurred more frequently than expected (see Table 4), indicating a deviation from independence. This finding supports Hypothesis 2b, suggesting that male characters’ expressions of power and autonomy are associated with a greater tendency to dehumanize female characters in the narrative, reinforcing broader themes of control and subjugation.

Finally, hypothesis 3 posited that sexualizing language is more likely to occur in contexts that also involve references to power struggles (i.e., female power and autonomy), reflecting an association between sexuality and control (see Table 5).

A chi-square test of independence was conducted to evaluate this association, with results showing a statistically significant relationship, χ2(1, N = 5,924) = 11.50, p = 0.0012. Expected values under the null hypothesis suggested approximately 10.54 cases would feature both sexualizing language and a power struggle, but the complete absence of such cases deviated significantly from expectations.

The significant p-value of 0.0012 supports Hypothesis 3, suggesting that sexualized descriptions and power dynamics are associated in the narrative, reinforcing a thematic link between sexuality and control. Interestingly, the absence of instances where both sexualizing language and female power struggles co-occur suggests that while sexuality and control are related, they may not appear simultaneously in the same scenes. Instead, they might serve as separate mechanisms to reinforce dominance, with one possibly precluding the other in specific narrative contexts. These results imply an interplay between sexuality and control, and further research could investigate how these elements are strategically deployed to portray power dynamics in narratives involving female characters.

6 Discussion

This study sought to explore how masculinity and femininity are constructed in misogynic hate communication, specifically examining the relationships between sexuality, violence, and power dynamics in collaborative storytelling. The results suggest that hypothesized associations between female autonomy assertions and male responses involving delegitimizing language or violence were not statistically significant. However, findings related to male dominance and its association with dehumanizing language, as well as the link between sexualized descriptions and power struggles, provide valuable insights into the ways gendered power dynamics and misogynistic attitudes are maintained within these narratives.

The application of MCA in this study reveals how online participants not only reference gender but actively construct and negotiate it within the discourse to establish group identities (Godar and Ferris, 2004), particularly around themes of exclusion and objectification. As Stommel et al. (2022) show, categorization in interaction is often implicit yet powerful, invoking stereotypes that perpetuate traditional views on gender. The data contains explicit and violent content that highlights a destructive and abusive relationship between the characters. In the data, the male characters exhibit dominant and violent behavior, while the female characters are portrayed as submissive and passive. This portrayal reflects stereotypical gender roles that reinforce traditional notions of male aggression and female subordination. The male characters exploit their power to dominate and oppress the female characters, aligning with Connell and Messerschmidt's (2005) concept of hegemonic masculinity, where masculinity is constructed through dominance and control over others.

An example of the construction of masculinity is the violent and dominant nature of the male characters. They restrain the women and compel them to endure actions against their will. This behavior demonstrates a conception of masculinity as violent and controlling, contributing to the reinforcement of toxic masculinity norms (Kimmel, 2015). Toxic masculinity refers to cultural norms that associate masculinity with control, aggression, and the devaluation of women, which can be harmful to both men and women. The construction of femininity is illustrated through the passive and submissive demeanor of the female characters. They mostly obey the male characters’ commands and endure the mistreatment they are subjected to. These depictions reinforce the stereotypical notion of femininity as submissive and passive and contribute to the objectification and dehumanization of women, treating them as objects without autonomy or voice.

Another central theme in the text is power and control. The male characters exercise their power over the female characters by holding them captive, restraining them, and subjecting them to abuse. They use their power to humiliate and degrade them, which is indicative of intimate partner violence rooted in patriarchal structures (Lawson, 2012; Lelaurain et al., 2021). This exertion of power reflects a unilateral distribution of power and the subordination of women, highlighting the inequality in gender relations (Ridgeway, 2007).

The depiction of forced interactions in the data indicates a broader rejection of consent as fundamental in relationships. MacKinnon (1991) argues that such representations normalize violence and undermine the importance of consent, perpetuating a culture that tolerates abuse against women. Furthermore, the control over the female body depicted in the narrative mirrors societal tendencies to police women’s autonomy and reproductive rights (Bordo, 1993).

Overall, the data illustrate the constructions of masculinity and femininity in a violent and abusive relationship. It highlights the stereotypical notion of masculinity as aggressive and controlling, while femininity is depicted as submissive and passive. These representations contribute to the normalization of toxic masculinity and the perpetuation of gender inequalities.

The lack of significant associations between female autonomy assertions and male responses in the forms of delegitimizing language or violence presents an intriguing deviation from prior research on misogynic hate communication. Studies have shown that women who assert autonomy often face negative responses intended to marginalize and silence their voices (Jaki et al., 2019). However, the results here imply that female characters’ actions, particularly their assertions of autonomy, may have little meaningful impact on male responses within these collaborative narratives. This could suggest that female characters are perceived as inherently subordinate regardless of their actions. Therefore, any display of autonomy is dismissed or ignored by male authors, rendering female agency inconsequential.

This interpretation aligns with research on objectification and dehumanization, where women are often reduced to passive roles, valued less for their actions and more as objects within a male-dominated narrative structure (Nussbaum, 1995; Ging, 2019). In this context, male characters may view female autonomy as inconsequential, adhering to a rigid narrative that reinforces male control regardless of female behavior. This suggests that, within these misogynic narratives, the very presence of female characters is sufficient to trigger negative responses, and their attempts to assert authority or influence have little effect on male characters’ predisposed actions. Such a pattern reinforces theories of hegemonic masculinity, where male dominance is maintained not as a reaction to specific female behaviors but as a default stance that positions women as inherently passive and subordinate (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005).

In contrast, a significant association was found between male power and autonomy assertion and dehumanizing language, supporting the hypothesis that expressions of male dominance align with language that dehumanizes female characters. This finding underscores the role of dehumanization in misogynic discourse, where male characters, upon asserting dominance, employ language that diminishes the humanity of female characters, thus reinforcing male authority and control. This aligns with theories of incivility in communication, where aggressive and dehumanizing language functions as a method of marginalizing and silencing the other, reinforcing traditional hierarchies and excluding women from meaningful participation (Blom et al., 2014; Rowe, 2015; Jane, 2014). The reliance on dehumanizing language highlights how these narratives are structured to uphold gendered power dynamics by positioning female characters as less-than-human, further embedding themes of control and subjugation.

Hypothesis 3, which examined the association between sexualized descriptions and power struggles, was also supported by a statistically significant finding. The results suggest that sexualization and power dynamics are linked in these narratives, reinforcing a thematic connection between sexuality and control. However, an intriguing aspect of the findings is that sexualizing language and power struggles do not occur simultaneously in the same scenes. This suggests that while both elements are related, they may function independently within the narrative, with each element contributing to control in a different way. Sexualization might be used to frame female characters as objects of male desire, reinforcing passivity, while power struggles emphasize the male character’s dominance over the female character as a separate display of control.

This relationship between sexuality and control aligns with broader trends in misogynic communication, where female sexuality is framed as both desirable and threatening – often viewed as a source of male control that does not require overt conflict to subjugate female characters (Baele et al., 2021; Eglin and Hester, 1999). In this narrative framework, the separate use of sexualization and power struggles might reflect a layered strategy that independently reinforces male dominance and female subordination, suggesting a more complex interplay between these elements than previously thought.

7 Conclusion

This study investigated the construction of masculinity and femininity in misogynic hate communication, focusing on language use and the relationships among sexuality, violence, and power dynamics within digital collaborative storytelling. Through Membership Categorization Analysis, the study analyzed how male and female roles were co-constructed in narratives involving German-language online interactions. The findings reveal that male characters’ responses did not significantly vary with female autonomy assertions, suggesting that female agency is disregarded, with male mistreatment occurring irrespective of female characters’ actions. However, associations were found between male dominance assertion and dehumanizing language, as well as between sexualized language and power struggles, emphasizing a connection between sexuality, control, and dehumanization in maintaining gendered power dynamics.

This study has limitations, including its focus on a specific digital community and linguistic context, which may limit generalizability to other platforms or cultures. A key limitation concerns the ecological validity of the data, as the narratives analyzed were produced by male participants who role-played both male and female characters. Consequently, the utterances of female characters cannot be interpreted as representative of women’s authentic discourse or lived experience. Instead, the present study treats these utterances as discursive performances of gender manifestations of how members of the manosphere linguistically imagine and reproduce femininity and masculinity. This perspective aligns with the Membership Categorization Analysis ethnomethodological understanding that gender is not a speaker property but a product of interactional construction (Garfinkel, 1967). While this design limits sociological generalization, it enables insight into the symbolic and ideological processes through which misogynic narratives are created and circulated in male-dominated online spaces. The precise identity of the online community cannot be disclosed to ensure participant anonymity and to comply with legal restrictions. This limits the possibility of contextualizing the discourse within a specific platform culture but does not affect the linguistic analysis of gendered interaction patterns.

Another limitation concerns the strong imbalance in the dataset, as some categories (particularly power and autonomy and violence) occurred only rarely. This uneven distribution reflects the inherently asymmetrical nature of misogynic discourse, in which certain linguistic practices (e.g., power and autonomy assertion by female characters) are exceptional rather than frequent. However, such sparsity also constrained the choice of statistical tests and reduced the robustness of inferential comparisons. To mitigate this issue, Fisher’s exact test was used where expected frequencies fell below five, ensuring valid statistical inference under these conditions. Nevertheless, the imbalance limits the generalizability of the quantitative findings and highlights the need for complementary qualitative analysis to capture the broader discursive dynamics.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of an intercoder reliability test, which was not conducted due to the explicit nature of the data. Consequently, the coding and interpretation of language use in the dataset reflect the perspective of a single coder without formal validation from multiple coders. While careful measures were taken to ensure consistency in coding, the lack of additional coders may introduce subjective bias, as the interpretations have not been cross-validated. Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating multiple coders to enhance the reliability and objectivity of the analysis.

Also, although the sentence-level analysis provides systematic and replicable evidence of linguistic co-occurrence patterns, it does not capture direct conversational sequences between speakers. Future research could expand on these findings by modeling the temporal dynamics of interaction, linking female and male utterances in conversational pairs or turns. Such analyses would allow for a more fine-grained test of response relationships implied in the hypotheses.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes to understanding how misogynic hate communication perpetuates gender inequality and supports toxic masculinity through language that undermines female autonomy and reinforces male dominance.

Building on the present study’s findings and limitations, future research should expand the scope by incorporating diverse linguistic and cultural contexts to determine whether similar discursive patterns of dehumanization, sexualization, and disregard for female autonomy emerge in other digital spaces. Given the limitations related to the gender role-playing nature of the data and the absence of female-authored discourse, future studies could analyze interactions involving female members to better assess how actual expressions of autonomy are received in misogynic communities. Additionally, addressing the imbalance in category frequencies will require larger or more targeted datasets. A qualitative approach could play a crucial role in complementing such expansions. By examining how misogynic ideologies are interactionally sustained, resisted, or reframed within specific conversational moments, qualitative analysis can reveal practices of gendered meaning-making that are often flattened in purely quantitative coding.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MK: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The University of Duisburg-Essen funds the open access publication fees of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Grammarly was used to check grammar and receive suggestions for clearer and more effective wording throughout the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiston, J. (2024). Vicious, vitriolic, hateful and hypocritical’: the representation of feminism within the manosphere. Crit. Discourse Stud. 21, 703–720. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2023.2257816

Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., and Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 19, 373–387. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12009

Baele, S. J., Brace, L., and Coan, T. G. (2021). From “Incel” to “saint”: analyzing the violent worldview behind the 2018 Toronto attack. Terrorism Polit. Violence 33, 1667–1691. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2019.1638256

Barnes, M. J., and Karim, S. M. (2025). The manosphere and politics. Comp. Pol. Stud. 00104140241312095, 1–41. doi: 10.1177/00104140241312095

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: a cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 88, 354–364. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

Blom, R., Carpenter, S., Bowe, B. J., and Lange, R. (2014). Frequent contributors within U.S. newspaper comment forums. Am. Behav. Sci. 58, 1314–1328. doi: 10.1177/0002764214527094

Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight: Feminism, western culture, and the body. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Bormann, M., Tranow, U., Vowe, G., and Ziegele, M. (2022). Incivility as a violation of communication norms—a typology based on normative expectations toward political communication. Commun. Theory 32, 332–362. doi: 10.1093/ct/qtab018

Bormann, M., and Ziegele, M. (2023). Incivility. In Challenges and perspectives of hate speech research. eds. C. Strippel, S. Paasch-Colberg, M. Emmer, and J. Trebbe (Berlin), 199–217. doi: 10.48541/dcr.v12.12

Bou-Franch, Patricia, and Garcés-Conejos Blitvich, Pilar. 2016. Gender ideology and social identity processes in online language aggression against women. In Patricia Bou-Franch (ed.), Benjamins Current Topics, 86, 59–81. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company

Brown, R., and Zagefka, H.. 2005. Ingroup affiliations and prejudice. In John F. Dovidio, Peter Glick, and Laurie A. Rudman (eds.), On the nature of prejudice, 54–70. 1st edn. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Bührig, K. (2002). “Interactional coherence in discussions and everyday storytelling: on considering the role of jedenfalls and auf jeden fall” in Rethinking sequentiality: Linguistics meets conversational interaction; based on papers from the 7th IPrA conference, which was held in Budapest in 2000 (Pragmatics & beyond). eds. A. Fetzer and C. Meierkord, vol. N.S., 103 (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 273–290. doi: 10.1075/pbns.103.13buh

Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft »Gegen Hass im Netz«, Textgain. (2024). Tracing Online Misogyny. Eine quantitative und qualitative Analyse verschiedener Facetten der Manosphere und misogyner Praxis im deutsch-internationalen Vergleich. Berlin. www.bag-gegen-hass.net.

Chovanec, J. (2023). “Negotiating hate and conflict in online comments: evidence from the NETLANG Corpus” in Hate speech in social media. ed. I. Ermida (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 341–367.

Coe, K., Kenski, K., and Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. J. Commun. 64, 658–679. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12104

Colleoni, E., Rozza, A., and Arvidsson, A. (2014). Echo chamber or public sphere? Predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in twitter using big data: political homophily on twitter. J. Commun. 64, 317–332. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12084

Connell, R. W., and Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: rethinking the concept. Gend. Soc. 19, 829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639

Coyne, S. M., Linder, J. R., Rasmussen, E. E., Nelson, D. A., and Collier, K. M. (2014). It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a gender stereotype!: longitudinal associations between superhero viewing and gender stereotyped play. Sex Roles 70, 416–430. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0374-8

Dahlberg, L. (2007). “The internet and discursive exclusion: from deliberative to agonistic public sphere theory” in Radical democracy and the internet. eds. L. Dahlberg and E. Siapera (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 128–147.

Douglas, K. M. (2012). “Psychology, discrimination and hate groups online” in eds. A. N. Joinson, K. Y. A. McKenna, T. Postmes, and U.-D. Reips, vol. 1 (Oxford University Press).

Dutta, A., Banducci, S., and Camargo, C. Q. (2025). Divided by discipline? A systematic literature review on the quantification of online sexism and misogyny using a semi-automated approach. Scientometrics 130, 4915–4971. doi: 10.1007/s11192-025-05410-2

Eglin, P., and Hester, S. (1999). “You’re all a bunch of feminists:” categorization and the politics of terror in the Montreal massacre. Hum. Stud. 22, 253–272. doi: 10.1023/A:1005444602547

Fitzgerald, R., and Housley, W. (Eds.) (2015). Advances in membership categorisation analysis. London: Sage.

Fontanella, L., Chulvi, B., Ignazzi, E., Sarra, A., and Tontodimamma, A. (2024). How do we study misogyny in the digital age? A systematic literature review using a computational linguistic approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:478. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-02978-7

Franklin-Paddock, B., Platow, M. J., and Ryan, M. K. (2025). From privilege to threat: unraveling psychological pathways to the manosphere. Arch. Sex. Behav. 54, 1325–1340. doi: 10.1007/s10508-025-03114-5

Friess, D., and Eilders, C. (2015). A systematic review of online deliberation research. Policy Internet 7, 319–339. doi: 10.1002/poi3.95

Geyer, Klaus, Bick, Eckhard, and Kleene, Andrea. 2022. ‘I am no racist but …’: a Corpus-based analysis of xenophobic hate speech constructions in Danish and German social media discourse. In Natalia Knoblock (ed.), The grammar of hate, 241–261. 1st edn. Cambrige: Cambridge University Press

Ging, D. (2019). Alphas, betas, and incels: theorizing the masculinities of the manosphere. Men Masculin. 22, 638–657. doi: 10.1177/1097184X17706401

Ging, D., and Siapera, E. (2018). Special issue on online misogyny. Feminist Media Stud. 18, 515–524. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2018.1447345

Godar, S. H., and Ferris, S. P. (2004). Virtual and collaborative teams: process, technologies, and practice. USA: IGI Global.

Hatzidaki, O. (2024). I’ll throw acid on your pretty little face […], so wrote a genteel fanatic antifeminist: the discursive management of male gender-driven aggression by eminent Greek female autobiographers of the 19th and early and mid-20th century. J. Lang. Aggr. Confl. doi: 10.1075/jlac.00123.hat

Hlalele, D., and Jode Brexa, (2015). Challenging the narrative of gender socialisation: digital storytelling as an engaged methodology for the empowerment of girls and young women. Agenda 29, 79–88. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2015.1073439

Housley, W., and Fitzgerald, R. (2015). “Introduction to membership categorisation analysis” in Advances in membership categorisation analysis. eds. R. Fitzgerald and W. Housley (London: Sage), 1–21.

Humă, B., Joyce, J. B., and Raymond, G. (2023). What does “resistance” actually look like? The Respecification of resistance as an interactional accomplishment. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 42, 497–522. doi: 10.1177/0261927X231185525

Hurt, M., and Grant, T. (2019). Pledging to harm: a linguistic appraisal analysis of judgment comparing realized and non-realized violent fantasies. Discourse Soc. 30, 154–171. doi: 10.1177/0957926518816195

Jaki, S., De Smedt, T., Gwóźdź, M., Panchal, R., Rossa, A., and De Pauw, G. (2019). Online hatred of women in the Incels.Me forum: linguistic analysis and automatic detection. J. Lang. Aggr. Confl. 7, 240–268. doi: 10.1075/jlac.00026.jak

Jane, E. A. (2014). Back to the kitchen, cunt’: speaking the unspeakable about online misogyny. Continuum 28, 558–570. doi: 10.1080/10304312.2014.924479

Jane, E. A. (2018). Systemic misogyny exposed: translating Rapeglish from the manosphere with a random rape threat generator. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 21, 661–680. doi: 10.1177/1367877917734042

Johnson, S. K., Murphy, S. E., Zewdie, S., and Reichard, R. J. (2008). The strong, sensitive type: effects of gender stereotypes and leadership prototypes on the evaluation of male and female leaders. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 106, 39–60. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2007.12.002

Kalch, A., and Naab, T. K. (2017). Replying, disliking, flagging: how users engage with uncivil and impolite comments on news sites. Stud. Commun. Media 6, 395–419. doi: 10.5771/2192-4007-2017-4-395

Kanz, V. (2021). “Die Echokammer als rechter Resonanzraum: Eine Analyse von Resonanzphänomenen innerhalb der Kommentarspalte eines AfD-Facebook-Beitrags” in Skandalisieren, stereotypisieren, normalisieren: Diskurspraktiken der Neuen Rechten aus sprach-und literaturwissenschaftlicher Perspektive (Sprache - Politik - Gesellschaft). eds. S. Pappert, C. Schlicht, M. Schröter, and S. Hermes (Hamburg: Buske), 167–194.

Kimmel, M. (2015). Angry white men: American masculinity at the end of an era. New York, NY: Nation Books.

Krug, Maximilian. 2024a. Inzivilität als Strategie: Kommunikative Funktionen inziviler Kategorien im Telegramkanal der rechtsradikalen Partei Freie Sachsen. In Forschungsgruppe Diskursmonitor und Diskursintervention, (ed.), Politisierung des Alltags. Strategische Kommunikation in öffentlichen Diskursen., 51–70. Siegen: Universitätsverlag Siegen.

Krug, M. (2024b). “Inzivile Meinungsbildung durch Superuser in rechten Telegramkanälen” in Tagungsband Wissenschaftskonferenz 2023: Meinungsbildung 2.0 – Strategien im Ringen um Deutungshoheit im digitalen Zeitalter. ed. Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, 154–162.

Lawson, J. (2012). Sociological theories of intimate partner violence. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 22, 572–590. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2011.598748

Lelaurain, S., Fonte, D., Giger, J.-C., Guignard, S., and Lo Monaco, G. (2021). Legitimizing intimate partner violence: the role of romantic love and the mediating effect of patriarchal ideologies. J. Interpers. Violence 36, 6351–6368. doi: 10.1177/0886260518818427

Lück, J., and Nardi, C. (2019). Incivility in user comments on online news articles: investigating the role of opinion dissonance for the effects of incivility on attitudes, emotions and the willingness to participate. Stud. Commun. Media 8, 311–337. doi: 10.5771/2192-4007-2019-3-311

Meiler, M. (2021). Storytelling in instant messenger communication. Sequencing a story without turn-taking. Discourse Context Media 43:100515. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100515

Montiel-McCann, C. (2024). Hegemonic femininity, femonationalism and the far-right: Boris Johnson’s textual representation of the burka and his rise to power in the UK. J. Lang. Aggr. Confl. doi: 10.1075/jlac.00115.mon

Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philos Public Aff 24, 249–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x

Pahor De Maiti, K., Franza, J., and Fišer, D. (2023). Haters in the spotlight: gender and socially unacceptable Facebook comments. Internet Pragmat. 6, 173–196. doi: 10.1075/ip.00093.pah

Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media Soc. 6, 259–283. doi: 10.1177/1461444804041444

Plummer, K. (2005). “Male Sexualities” in Handbook of studies on men & masculinities (Thousand Oaks California: SAGE Publications, Inc), 178–195.

Ridgeway, C. L. (2007). “Gender as a group process: implications for the persistence of inequality” in Shelley J. Correll (Hrsg.), Social Psychology of Gender, vol. 24 (Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1016/S0882-6145(07)24012-3

Rowe, I. (2015). Civility 2.0: a comparative analysis of incivility in online political discussion. Inf. Commun. Soc. 18, 121–138. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2014.940365

Sacks, H. (1972). “An initial investigation of the usability of conversational data for doing sociology” in Studies in social interaction. ed. D. Sudnow (New York; NY: Free Press), 31–74.

Sacks, Harvey. 1992. Lectures on conversation: Volumes I & II. (Ed.) Harvey Sacks & Gail Jefferson. 1. Publ. In one paperback volume 1995, [Nachdr.]. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sagredos, C., and Nikolova, E. (2022). Slut I hate you’: a critical discourse analysis of gendered conflict on YouTube. J. Lang. Aggr. Confl. 10, 169–196. doi: 10.1075/jlac.00065.sag

Salter, A., and Blodgett, B. (2012). Hypermasculinity & dickwolves: the contentious role of women in the new gaming public. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 56, 401–416. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2012.705199

Schumann, J., and Steve Oswald, (2024). Pragmatic perspectives on disagreement. J. Lang. Aggr. Confl. 12, 1–16. doi: 10.1075/jlac.00094.sch

Sinkeviciute, V. (2024). Multimodal joint fantasising as a category-implicative and category-relations-implicative action in online multi-party interaction. Internet Pragmat. 7, 101–136. doi: 10.1075/ip.00110.sin

Stevanovic, M., and Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic authority in interaction: the right to announce, propose, and decide. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 45, 297–321. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2012.699260

Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: when nodding is a token of affiliation. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 41, 31–57. doi: 10.1080/08351810701691123

Stivers, T. (2015). Coding social interaction: a heretical approach in conversation analysis? Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 48, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2015.993837

Stokoe, E. (2012). Moving forward with membership categorization analysis: methods for systematic analysis. Discourse Stud. 14, 277–303. doi: 10.1177/1461445612441534

Stokoe, Elizabeth, and Edwards, Derek. 2009. Accomplishing social action with identity categories: mediating and policing neighbour disputes. In Margaret Wetherell (ed.), Theorizing identities and social action (Identity Studies in the Social Sciences), 95–115. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stommel, W., Plug, I., Olde Hartman, T. C., Lucassen, P. L. B. J., van Dulmen, S., and Das, E. (2022). Gender stereotyping in medical interaction: A Membership Categorization Analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 3242–3248. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.07.018

Voutilainen, L., Henttonen, P., Kahri, M., Kivioja, M., Ravaja, N., Sams, M., et al. (2014). Affective stance, ambivalence, and psychophysiological responses during conversational storytelling. J. Pragmat. 68, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.006

Wescott, S., Roberts, S., and Zhao, X. (2024). The problem of anti-feminist ‘manfluencer’ Andrew Tate in Australian schools: women teachers’ experiences of resurgent male supremacy. Gend. Educ. 36, 167–182. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2023.2292622

Keywords: misogynic hate communication, incivility, toxic masculinity, objectification, dehumanization, gender roles, power dynamics, violence

Citation: Krug M (2025) Inconsequential female autonomy in misogynic hate communication: male dominance, dehumanization, and sexualization in digital collaborative storytelling. Front. Commun. 10:1662590. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1662590

Edited by:

Ke Zhang, Shandong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Lara Fontanella, Chieti-Pescara University, ItalyAndreea Voina, Universitatea Babes Bolyai, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Krug. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maximilian Krug, TWF4aW1pbGlhbi5rcnVnQHVuaS1kdWUuZGU=

Maximilian Krug

Maximilian Krug