- 1Swiss Paraplegic Research, Nottwil, Switzerland

- 2Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, University of Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

- 3Institute of Public Health, Università della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, Switzerland

Background: Effective communication is essential during health crises to maintain operational clarity, staff engagement, and public trust. While existing models emphasise centralised crisis response and structured messaging, few studies examine how hospital communication evolves across different phases of a prolonged emergency.

Objective: This study explored how Swiss hospitals adapted their internal and external communication strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying key challenges, approaches, and lessons for future preparedness.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective qualitative study based on semi-structured interviews with 18 communication leaders from public hospitals across Switzerland. Thematic analysis was used to identify evolving communication strategies, challenges, and adaptations over time.

Results: Four dynamic phases emerged: preparedness and early onset, peak crisis response, stabilisation, and prolonged crisis adaptation. Communication strategies shifted from rapid internal coordination and leadership visibility to targeted digital engagement and staff support. Hospitals implemented structured messaging loops, leveraged mobile platforms, engaged in proactive media outreach, and introduced psychological support and recognition campaigns. Over time, they also refined communication protocols and reduced message frequency to avoid overload. Despite these efforts, challenges remained in managing decentralised coordination, sustaining morale, and countering misinformation.

Conclusion: Hospital communication during COVID-19 required continuous adaptation. Beyond disseminating information, effective strategies fostered connection, reassurance, and trust. Our findings highlight the need for communication systems that are both structured and flexible, grounded in resilience, and integrated into broader institutional crisis planning. These insights inform future communication frameworks for healthcare institutions facing prolonged emergencies.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally reshaped global healthcare systems, exerting extraordinary pressure on hospitals as they struggled to meet surging patient care demands while navigating an evolving landscape of complex communication challenges (WHO, 2020). In times of crisis, effective communication is not merely supportive but indispensable—it ensures that healthcare providers, patients, families, and the broader public receive timely, accurate, and coherent information. The pandemic underscored the critical importance of robust communication systems, particularly in a context defined by pervasive uncertainty, heightened anxiety, and the viral spread of misinformation (Paakkari and Okan, 2020; Rosenbaum, 2020).

Switzerland’s healthcare system, organized under a federal structure, delegates responsibilities for healthcare delivery across the federal government, 26 cantons, and municipalities. Hospitals operate within a mixed public–private framework, but public hospitals are the main providers of acute care and are closely integrated with cantonal health authorities (Sturny, 2020; Boes et al., 2025). Hospitals are categorized according to a federal typology based primarily on activity domains and care days per division, distinguishing between general care hospitals and specialized clinics. General care hospitals are further divided into centralized care hospitals and basic care hospitals. As of 2023, the centralized care category included five university hospital centers and 39 other large establishments, typically cantonal hospitals (Kennzahlen der Schweizer Spitäler, n.d.). This decentralized and diverse structure, combined with linguistic and cultural diversity, creates both opportunities and challenges for crisis communication, particularly during prolonged emergencies.

In this context, the pandemic served as a revealing stress test for hospital communication, exposing both strengths and vulnerabilities. Swiss hospitals faced a complex set of obligations: ensuring transparency, protecting patient confidentiality, and reassuring an anxious public. At the same time, they had to coordinate with decentralized health authorities, adapt to shifting guidelines, address staff safety concerns, and communicate effectively with a multilingual and multicultural population (Schlögl et al., 2021; Rubinelli et al., 2023; Schumacher et al., 2023). These overlapping challenges underscored the need for communication strategies that were both adaptable and resilient under prolonged pressure (Ehrenzeller et al., 2022; Grazioli et al., 2022).

Traditional crisis communication models, often structured around the phases of preparation, response, and aftermath (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005), provided a starting point for hospitals. However, the prolonged uncertainty and intensity of the pandemic quickly exposed the limitations of these linear frameworks. As a result, hospitals had to develop and adapt communication strategies on the fly, learning through experience what was effective and what was not (Bloom et al., 2021; Rosenbäck and Eriksson, 2024). The pandemic thus offers a rare and invaluable lens through which to examine the effectiveness of hospital crisis communication strategies, revealing not only critical gaps and opportunities for improvement but also the practical expertise hospitals acquired.

Despite their relevance, the specific communication experiences of Swiss hospitals during COVID-19 remain largely underexplored. This leaves a gap in the empirical and theoretical foundations needed to enhance preparedness for future crises on both national and global scales. This study aims to address this gap by systematically investigating the communication challenges encountered by Swiss hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic and analyzing the strategies they employed to overcome these obstacles. Its objectives are threefold:

First, to identify key communication challenges faced by Swiss hospitals d ng health crises, including internal coordination, public information dissemination, and alignment with governmental authorities.

Second, to analyze adaptive strategies and tools used to address these challenges, such as digital communication platforms, structural innovations, and targeted messaging approaches.

Third, to provide actionable recommendations for strengthening crisis communication preparedness in healthcare institutions, offering pragmatic solutions for healthcare leaders navigating future emergencies.

Switzerland’s healthcare system—marked by its decentralized governance, multilingual complexity, and commitment to high standards of care—provides a uniquely compelling case study for crisis communication in healthcare. By situating this research within the Swiss context, the study not only sheds light on local practices but also offers insights of global relevance. Its findings will contribute to the international literature on healthcare crisis communication, informing strategies that extend beyond pandemics to encompass a wide spectrum of crises, from natural disasters to public health emergencies.

Materials and methods

Study design

We chose a qualitative research design (Finset, 2008) to explore the communication challenges faced and strategies adopted by Swiss hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach allowed us to engage directly with hospital communication leaders, capturing their perspectives and experiences in a way that goes beyond surface-level strategies to reveal the thought processes and decisions underpinning their actions. Semi-structured interviews (Cohen and Crabtree, 2006) formed the heart of our data collection, providing participants with the space to share their stories openly and in detail. This conversational format also enabled us to ask follow-up questions, clarify points, and better understand the unique contexts in which they operated. By doing so, we aimed to build a deeper, more human understanding of the complexities of crisis communication within the healthcare sector.

Participants and recruitment

The study targeted leaders of Swiss public hospitals who were directly responsible for designing and implementing crisis communication strategies during the pandemic. Depending on the hospital, these roles included the hospital director, CEO, or communication specialist. Inclusion criteria specified that participants should hold managerial or leadership roles with regard to communication within their hospital to ensure that they had adequate insight into both the strategic and operational aspects of crisis communication. We systematically contacted all Swiss public hospital organizations — including both cantonal hospital networks and university hospital centers — using professional networks and publicly available contact lists. These approximately 45 organizations often comprise multiple hospital sites operating under the same administrative structure (Kennzahlen der Schweizer Spitäler, n.d.). Of these, 18 organizations agreed to participate, representing roughly 40% of the sector. The sample included hospitals from all three linguistic regions of Switzerland ensuring diversity in perspectives. In the Italian-speaking Canton of Ticino, the hospital sector is organized as a single public hospital network. Consequently, only one representative could be recruited from this region, reflecting the organizational structure rather than an imbalance in recruitment.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, conducted via secure video conferencing platforms or in person, depending on participant preference and in observance of public health guidelines at the time. Interviews were conducted between January and July 2021, towards the end of the second wave of the pandemic in Switzerland, each lasting between 60 to 90 min. All interviews were audio-recorded with participant consent, then transcribed verbatim for analysis.

The interview guide was developed specifically for this study (Supplementary File 1), drawing on existing literature on crisis communication in healthcare and preliminary consultations with hospital communication experts. During the interviews, participants were invited to reflect retrospectively on several key areas: their initial reactions and preparedness at the onset of the pandemic; specific communication challenges encountered; the strategies used to address these challenges, including the deployment of digital tools and changes to internal communication structures; perceived differences between the first and second waves; and lessons learned regarding the effectiveness of their communication efforts.

The semi-structured format provided flexibility, allowing participants to raise issues specific to their institutional context while ensuring that core topics were consistently explored across all interviews.

Data analysis

We employed a codebook-style thematic analysis, drawing on Braun and Clarke’s foundational principles (Braun and Clarke, 2006) but aligning more closely with the structured, consensus-oriented approach commonly used in applied health research (Nowell et al., 2017). This method, focused on transparency, consistency, and actionable findings, emphasises a collaboratively developed coding framework refined through iterative discussions, rather than the researcher subjectivity and theoretical positioning typical of reflexive thematic analysis.

Familiarization began with repeated readings of transcripts to capture initial impressions and recurring patterns. Using an inductive–deductive approach, we developed a coding framework that integrated emerging themes with insights from the literature on crisis communication. Line-by-line coding was conducted to capture both explicit content and underlying meanings, with codes iteratively refined and grouped into broader themes and subthemes to identify patterns across hospitals. Coding continued until no new themes emerged, indicating thematic adequacy in line with Guest et al. (2006). Themes were reviewed for internal coherence, merging overlapping categories and retaining divergent perspectives to reflect the heterogeneity of hospital experiences.

Data organisation and analysis were supported by MAXQDA, enabling systematic coding, theme development, and efficient data retrieval. Two researchers (ND, MF) independently coded the first five transcripts, compared and refined the initial codes in joint discussions, and resolved discrepancies through consensus. The remaining transcripts were coded using the agreed framework, with regular team meetings to ensure consistency and refine thematic development. These meetings also provided reflexive spaces to critically examine the influence of the team’s disciplinary backgrounds—spanning health communication, public health, and qualitative research—on analysis and interpretation, thereby enhancing rigour and grounding findings in participants’ accounts.

Results

A total of N = 18 hospital communication leaders—including seven directors, seven communication specialists, and four CEOs—participated in the study, providing a comprehensive view of hospital communication practices across Switzerland. Most participants were male (n = 16) and worked in the German-speaking part of Switzerland (n = 11), while six were based in the French-speaking region and one in the Italian-speaking region.

Our thematic analysis revealed that hospital communication during the pandemic evolved dynamically, with strategies continuously adapting to shifting priorities, needs, and constraints. Throughout the analysis, we identified recurring patterns that captured both the phases of communication over time and the specific challenges hospitals faced within each phase. These findings highlight how hospitals navigated operational demands, supported staff well-being, maintained public trust, and coordinated with stakeholders in a rapidly changing environment.

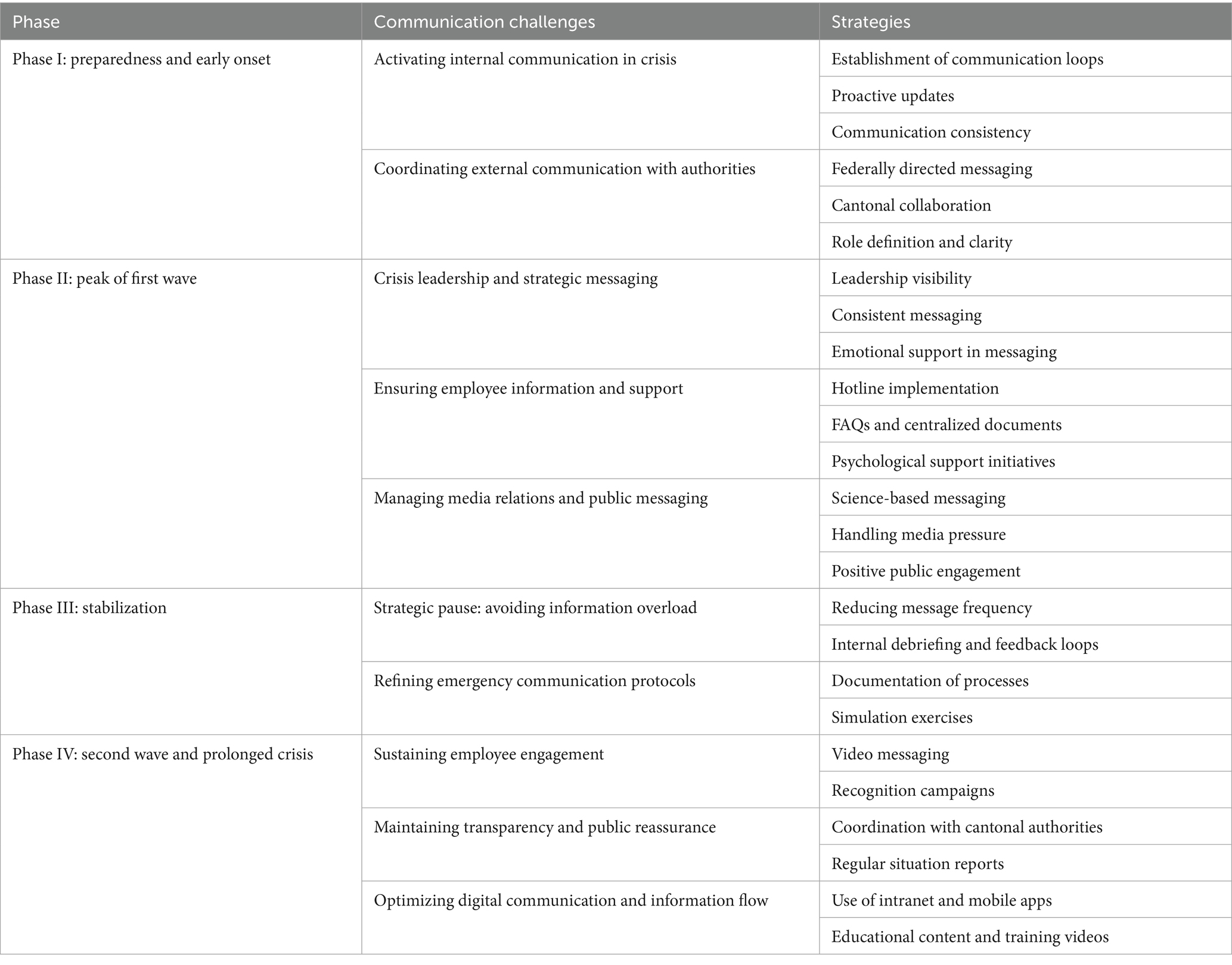

The patterns were grouped into four phases that reflect the temporal and operational evolution of communication: (I) Preparedness and early onset, (II) Peak of the first wave, (III) Stabilization, and (IV) Second wave and prolonged crisis. Within each phase, distinct challenges emerged, alongside the strategies hospitals developed to address them. Table 1 provides an overview of these challenges and corresponding strategies.

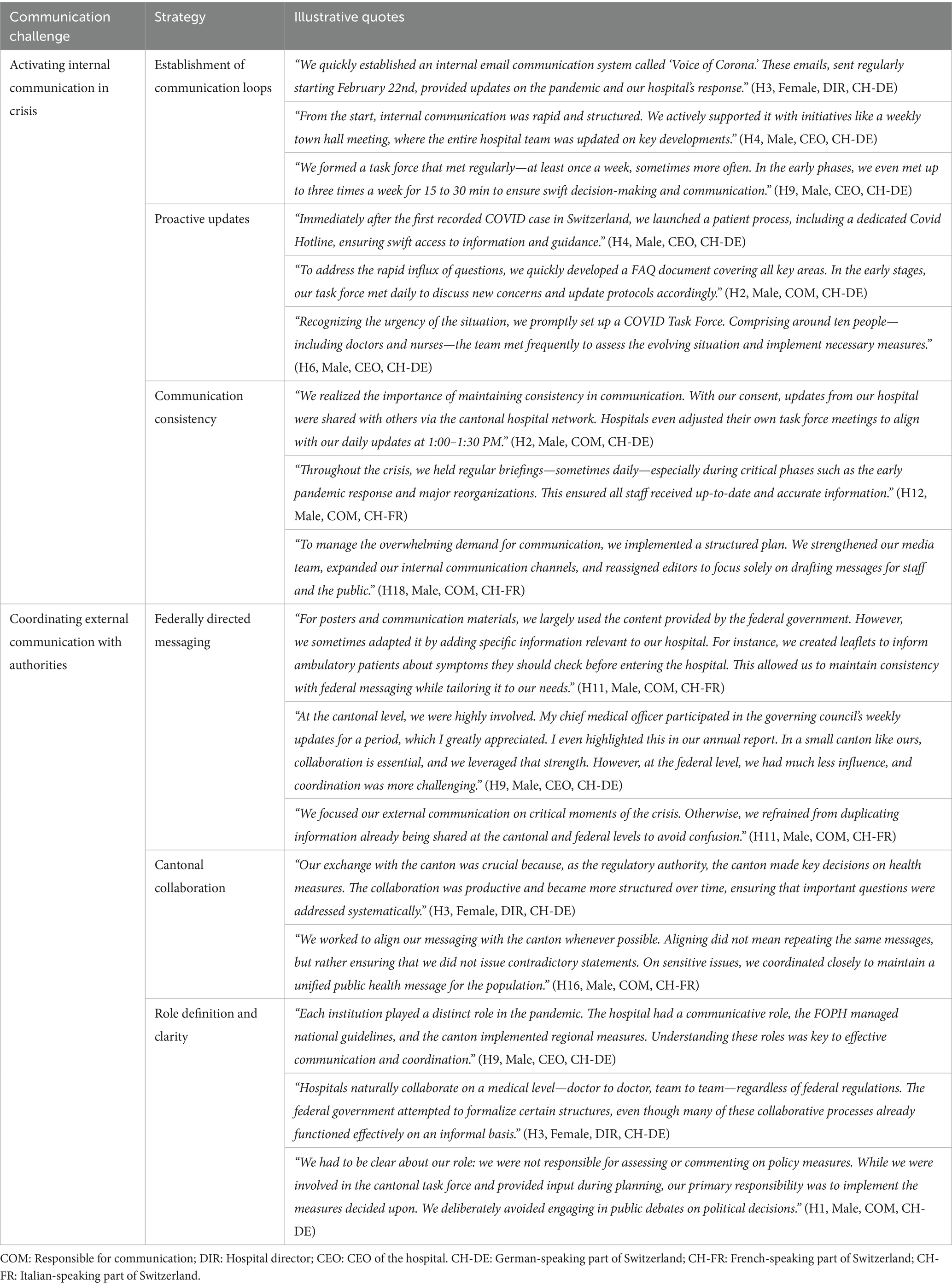

Phase I: preparedness and early onset

In the initial phase of the pandemic, Swiss hospitals faced significant uncertainty as they transitioned from routine operations to crisis communication. Preparing for an escalating emergency required swift action to establish internal cohesion, align with external authorities, and build public trust. Illustrative quotes for the strategies within each communication challenge are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Phase I: preparedness and early onset—communication challenges, strategies and illustrative quotes.

Challenge 1: activating internal communication in crisis

From the very beginning of the pandemic, hospitals had to shift rapidly from routine to crisis communication, ensuring that staff remained informed and prepared. Many described setting up structured communication loops almost immediately, with dedicated task forces, regular briefings, and internal email updates to streamline information flow. As one hospital director explained, “We quickly established an internal email communication system called ‘Voice of Corona.’ These emails, sent regularly starting February 22nd, provided updates on the pandemic and our hospital’s response” (H3, Female, DIR, CH-DE). These efforts not only reassured staff but also played a key role in maintaining trust and keeping operations running smoothly during an uncertain time.

Challenge 2: coordinating external communication with authorities

Hospitals worked closely with cantonal and federal authorities to ensure that communication was aligned and consistent across different levels of governance. Many described a structured collaboration with regional authorities, where regular meetings helped synchronize policies and avoid contradictory messaging. As one communication lead explained, “We worked to align our messaging with the canton whenever possible. Aligning did not mean repeating the same messages, but rather ensuring that we did not issue contradictory statements. On sensitive issues, we coordinated closely to maintain a unified public health message for the population” (H16, Male, COM, CH-FR). While federal messaging provided a foundation for public communication, hospitals adapted materials to their local context and maintained clarity in roles—focusing on internal updates and operational implementation while broader public health messaging remained with cantonal and federal agencies. This balance reduced confusion, strengthened public trust, and allowed staff to concentrate on patient care rather than navigating policy debates.

Phase II: peak of the first wave

The first wave of COVID-19 presented unprecedented challenges, with hospitals managing a surge in cases while intensifying communication efforts. Maintaining clarity, morale, and public trust became critical as institutions operated under immense pressure. Illustrative quotes for the strategies within each communication challenge are presented in Table 3.

Challenge 3: crisis leadership and strategic messaging

Leadership played a critical role in maintaining stability and trust during the crisis, with many emphasizing that visibility and clear communication were essential for effective crisis management. Hospital leaders described making a deliberate effort to be present—walking through hospital corridors, speaking directly with staff, and ensuring that employees felt supported amidst uncertainty. As one director noted, “When I walk through the corridors of the hospital, people are grateful and feel they have a CEO who was with them. Leadership worked alongside them, and this strengthened the connection between employees and management” (H15, Male, DIR, CH-FR). Structured and consistent messaging was also seen as key to maintaining confidence, with many opting for scheduled updates that provided staff with a clear assessment of the situation and an outlook on what to expect. This helped to prevent information overload while ensuring clarity in rapidly changing circumstances. At the same time, leaders recognized that communication was not only about information but also emotional support—messages were framed to reinforce a sense of teamwork, solidarity, and reassurance, helping to sustain morale throughout the crisis. By balancing visible leadership, structured messaging, and emotional reassurance, hospitals were able to foster a sense of trust and collective resilience during one of the most challenging periods in healthcare.

Challenge 4: ensuring employee information and support

Ensuring that staff had access to reliable information and emotional support was a top priority for hospitals throughout the pandemic. Many institutions quickly set up hotlines to address employee concerns, repurposing mediation offices to handle inquiries and alleviate the burden on medical teams. As one communication lead recalled, “The first thing I did was set up a hotline… repurposing mediators to manage the internal hotline, providing support for employees who were panicked or had concerns, for example, about vulnerable family members” (H18, Male, COM, CH-FR). This direct communication approach reassured staff and allowed them to receive timely responses to urgent questions. Hospitals also created centralized FAQ documents and online platforms, where employees could regularly access updated protocols, hygiene guidelines, and supply stock reports. This transparency helped build trust and ensured that messaging remained consistent across all levels of the institution. Beyond logistical support, hospitals also recognized the emotional strain on their workforce and actively promoted psychological support initiatives, reinforcing that staff were not alone in navigating the crisis. Leaders emphasized that communication needed to go beyond operational updates—it had to provide reassurance, validation, and a sense of solidarity. By combining practical information with emotional support, hospitals were able to foster a more resilient and informed workforce during an exceptionally challenging period.

Challenge 5: managing media relations and public messaging

Hospitals played a crucial role in shaping public discourse during the pandemic, balancing science-based messaging, media scrutiny, and proactive public engagement. Many institutions emphasized the need to uphold evidence-based communication, ensuring that all public statements were aligned with federal and cantonal guidelines, as well as international professional organizations. As one communication lead explained, “We committed to evidence-based communication […] We only communicated what had stable evidence and refused to engage in speculation or misinformation, such as claims that vaccines contained microchips” (H10, Male, DIR, CH-DE). At the same time, hospitals had to navigate intense media pressure, as scientific debates—normally confined to expert circles—were suddenly amplified in the public sphere. Some interviewees highlighted how misinterpretations of data and sensationalized headlines fueled confusion, while increased visibility led to criticism, particularly from COVID skeptics. Despite these challenges, hospitals also saw opportunities for positive public engagement, using social media, storytelling, and direct collaboration with journalists to position themselves as trusted sources of health information. By combining rigorous fact-checking, strategic media management, and proactive community outreach, hospitals reinforced public trust while countering misinformation during a time of heightened uncertainty.

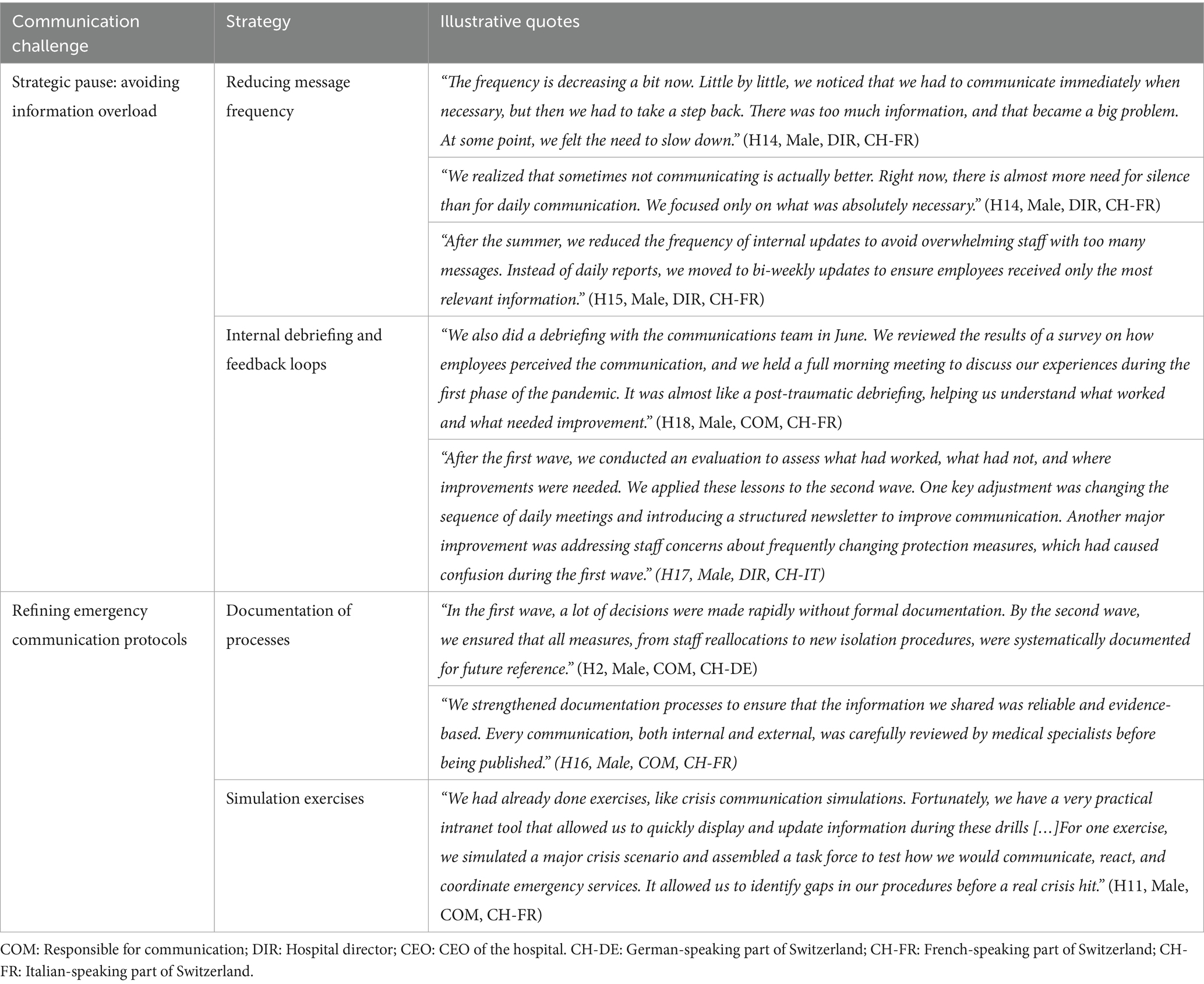

Phase III: stabilization

As cases declined during the summer after the first pandemic wave, hospitals shifted their focus to reflection and preparation. This phase allowed institutions to evaluate past strategies, reduce communication intensity, and strengthen their readiness for potential future waves. Illustrative quotes for the strategies within each communication challenge are presented in Table 4.

Challenge 6: strategic pause: avoiding information overload

As the pandemic progressed, hospitals recognized the need to reduce communication frequency and shift toward a more strategic approach. Initially, frequent updates were essential, but over time, staff became overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information. Many institutions deliberately slowed down their messaging, focusing only on critical updates and transitioning from daily to less frequent reports to ensure clarity without creating unnecessary noise. As one director reflected, “The frequency is decreasing a bit now. Little by little, we noticed that we had to communicate immediately when necessary, but then we had to take a step back. There was too much information, and that became a big problem” (H14, Male, DIR, CH-FR). Beyond adjusting communication frequency, hospitals also engaged in internal debriefing and feedback loops to reflect on their crisis response. Several institutions conducted evaluations, reviewing staff perceptions of communication efforts and identifying key areas for improvement. These reflections led to practical adjustments, such as restructuring daily meetings, refining message sequencing, and addressing confusion surrounding frequently changing protocols. The shift toward intentional, well-paced communication and structured reflection allowed hospitals to move from reactive crisis management to a more sustainable long-term strategy.

Challenge 7: refining emergency communication protocols

The pandemic highlighted the need for hospitals to formalize and refine emergency protocols, ensuring that lessons learned from the crisis were integrated into long-term preparedness strategies. Many institutions acknowledged that in the early stages of the pandemic, decisions were often made rapidly without comprehensive documentation. As one communications lead explained, “In the first wave, a lot of decisions were made rapidly without formal documentation. By the second wave, we ensured that all measures, from staff reallocations to new isolation procedures, were systematically documented for future reference” (H2, Male, COM, CH-DE). Alongside this, several hospitals emphasized the value of simulation exercises, which had been conducted prior to the pandemic to test crisis communication and emergency coordination. These drills provided a structured environment to identify procedural gaps, refine response strategies, and improve the usability of internal communication tools. The experience of COVID-19 reinforced the necessity of these preemptive training efforts and real-time documentation, ensuring that future crisis management would be more structured, evidence-based, and seamlessly executed.

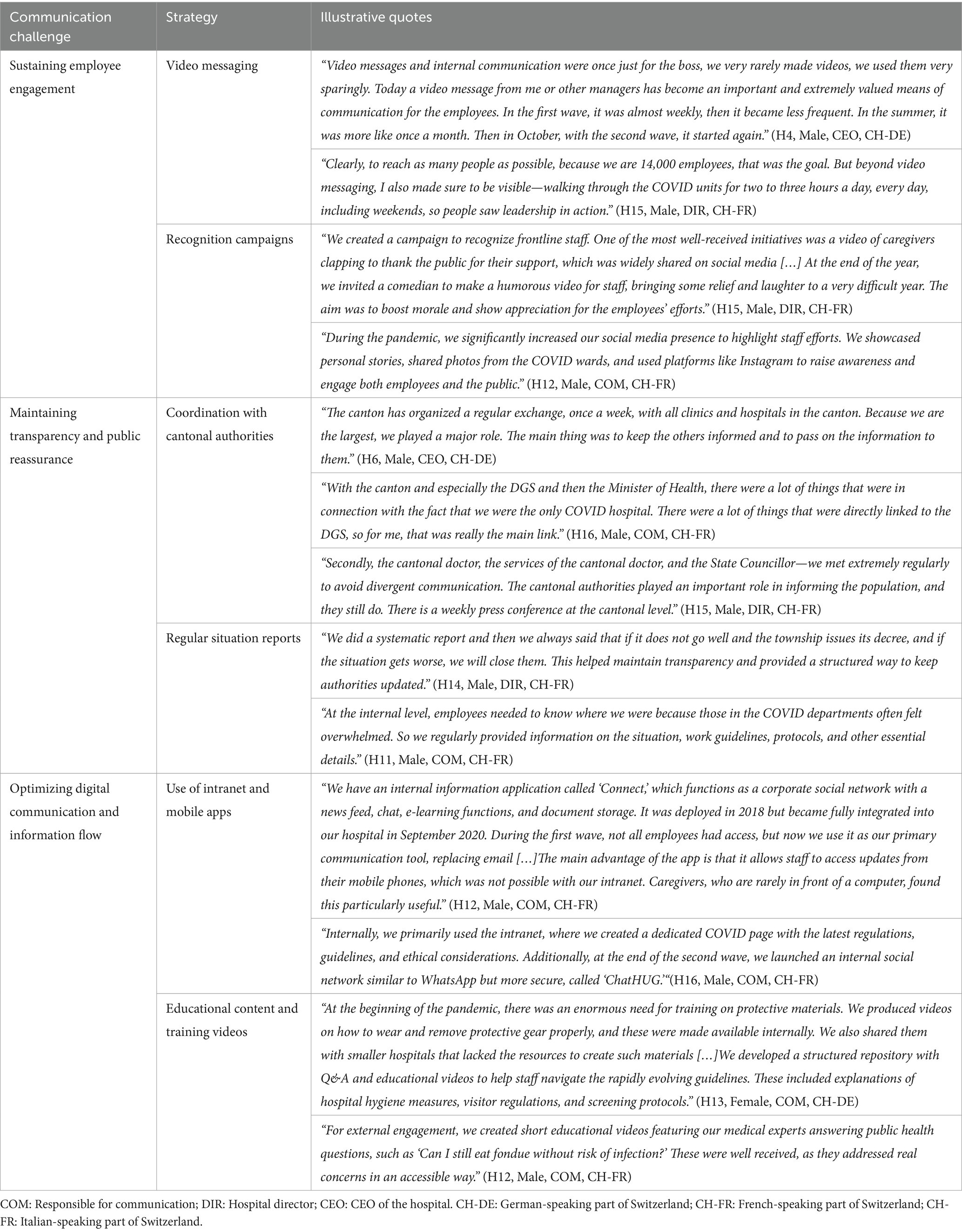

Phase IV: second wave and prolonged crisis

The second wave brought sustained challenges, but hospitals applied lessons from the first wave to implement more structured and effective communication strategies. Focus shifted to supporting staff resilience, fostering transparency, and optimizing digital tools. Illustrative quotes for the strategies within each communication challenge are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. Phase IV: second wave and prolonged crisis—communication challenges, strategies and illustrative quotes.

Challenge 8: sustaining employee engagement

As the pandemic extended into the second wave, hospitals recognized the need for long-term strategies to maintain employee engagement and morale. Leadership adapted their communication approach, for instance by making video messaging a regular practice, shifting from sporadic updates to scheduled messages that provided staff with a sense of continuity. As one hospital leader explained, “Video messages and internal communication were once just for the boss, we very rarely made videos. Today a video message from me or other managers has become an important and extremely valued means of communication for the employees” (H4, Male, CEO, CH-DE). While video updates became less frequent during the summer lull, they resumed in the second wave, reinforcing leadership visibility at a time when staff fatigue was growing. Beyond digital engagement, hospital leaders emphasized in-person presence, walking through COVID units daily to demonstrate support and strengthen connections with employees. At the same time, hospitals expanded recognition campaigns to sustain motivation, using social media to highlight staff efforts, sharing personal stories from COVID wards, and organizing morale-boosting initiatives, such as gratitude videos and lighthearted content. These sustained efforts helped foster a sense of belonging and resilience, ensuring that employees remained engaged despite the prolonged crisis.

Challenge 9: maintaining transparency and public reassurance

As the pandemic entered its second wave, hospitals reinforced transparent communication strategies to maintain trust with both employees and the public. Close coordination with cantonal authorities became even more structured, with weekly meetings ensuring hospitals remained aligned with public health policies. As one director noted, “The canton has organized a regular exchange, once a week, with all clinics and hospitals in the canton. Because we are the largest, we played a major role. The main thing was to keep the others informed and to pass on the information to them” (H6, Male, CEO, CH-DE). Hospitals that served as dedicated COVID centers were in direct and frequent contact with government officials, working to clarify evolving policies and avoid conflicting messages. Internally, the need for regular situation reports persisted, as employees—especially those in overwhelmed COVID units—relied on structured updates to navigate shifting protocols and workload demands. Unlike the first wave, where communication was often reactive, the second wave saw hospitals refining their information flow, ensuring that updates were more targeted and strategic. By maintaining open exchanges with authorities and structured internal briefings, hospitals helped stabilize communication in a prolonged crisis phase, reinforcing both staff confidence and public reassurance.

Challenge 10: optimizing digital communication and information flow

During the second wave, hospitals further expanded digital communication tools to address the ongoing need for efficient information dissemination. Many institutions transitioned from email-based updates to mobile apps and intranet platforms, making it easier for frontline staff to access real-time information. As one communications manager explained, “We have an internal information application called ‘Connect,’ which functions as a corporate social network with a news feed, chat, e-learning functions, and document storage […] The main advantage of the app is that it allows staff to access updates from their mobile phones, which was not possible with our intranet. Caregivers, who are rarely in front of a computer, found this particularly useful” (H12, Male, COM, CH-FR). Unlike the first wave, where digital systems were sometimes underutilized, by the second wave, dedicated apps and intranet pages became primary communication hubs, allowing caregivers to stay updated without relying on desktop access. The demand for educational content and training videos also persisted, prompting hospitals to refine their structured repositories with instructional materials on protective equipment, hygiene protocols, and evolving visitor policies. Beyond internal use, hospitals leveraged digital tools for external public engagement, creating expert-led videos that addressed everyday concerns and provided evidence-based health information. This shift toward integrated digital strategies during the second wave ensured that communication remained efficient, accessible, and responsive to the prolonged nature of the crisis.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic placed unprecedented demands on healthcare systems, underscoring the critical role of effective crisis communication. This study explored how Swiss hospitals navigated these challenges, identifying key strategies, obstacles, and lessons that can inform future preparedness efforts. Our findings show that hospital communication evolved dynamically, with strategies adapting to the rapidly changing conditions of the pandemic. When mapped against the classic stages of crisis communication—preparation, response, and aftermath (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005)—our phase-based findings reveal a more fluid and iterative process. The early phase reflected elements of preparedness, with hospitals rapidly mobilizing taskforces, developing protocols, and aligning messaging with federal and cantonal directives to ensure internal cohesion. During the acute response of the first wave, communication intensified and external engagement became central, with leadership visibility, science-based messaging, and efforts to counter misinformation playing a pivotal role. At the same time, recognition campaigns supported staff morale and fostered community solidarity. As the situation stabilized in the summer, hospitals entered a phase of reflection and recalibration, corresponding only partially to the “aftermath” phase in traditional models. Internal debriefings, documentation, and simulation exercises enabled hospitals to assess gaps and refine protocols, while adjusting communication frequency to prevent information fatigue. During the prolonged crisis phase of the second wave, communication became more structured and digitally supported, with tools such as intranet platforms and mobile apps used to deliver real-time updates, disseminate training materials, and maintain engagement, particularly with non-desk staff. These findings highlight that while established frameworks provided a valuable foundation, the prolonged and unpredictable nature of the pandemic required continuous adaptation, iteration, and the integration of digital solutions beyond the linear progression of classic models.

Our findings extend existing frameworks by showing that hospital communication during COVID-19 did not follow a strictly linear path. Traditional models, such as the Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication framework (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005) and the WHO pandemic phases (WHO, 2009), offer a valuable foundation but assume a clear sequence of preparation, response, and recovery. By contrast, our phase-based analysis reveals a more adaptive and iterative process, where hospitals moved fluidly between immediate crisis management, structured reflection, and the integration of digital tools as the situation evolved. This phase-emergent, experience-driven approach adds a novel layer of understanding to crisis communication, underscoring the importance of flexibility in navigating prolonged and complex emergencies. These dynamics also reflect principles of organisational resilience (Paton and Johnston, 2017), highlighting how continuous learning and adjustment supported hospitals under sustained pressure. Moreover, the emphasis on leadership visibility, role clarity, and the maintenance of trust aligns with Situational Crisis Communication Theory (Coombs, 2007), but demonstrates how these principles were contextually adapted to the realities of a rapidly evolving health crisis.

Finally, our findings reinforce the dual importance of internal and external communication across different phases of a prolonged emergency (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005). Early in the crisis, internal cohesion and alignment were critical for operational stability, whereas later phases required strong public messaging to sustain transparency and accountability. These insights suggest that effective crisis communication requires not only relevant content and timing but also the ability to adjust strategies over time—supporting both short-term responsiveness and long-term resilience.

Implications for crisis preparedness and organisational practice

The communication challenges and related strategies described by hospital leaders offer valuable insights that can inform efforts to enhance crisis preparedness and organisational resilience, while recognising that their relevance may vary across contexts. First, the early formation of taskforces and structured communication loops was key to ensuring timely decision-making and operational coherence. These findings reinforce prior research emphasising the importance of predefined emergency communication frameworks and role clarity for effective crisis response (Adini et al., 2007; WHO, 2011). Hospitals should incorporate flexible yet formalised communication protocols into their emergency preparedness plans, including predefined chains of communication and delegation of spokesperson responsibilities. Regular simulation exercises and scenario-based training—shown to improve communication coordination and confidence under pressure (Baetzner et al., 2022)—can help test these protocols in advance.

Second, staff engagement emerged as a central concern, with hospitals recognising that maintaining morale and resilience required more than information flow. Consistent leadership visibility, emotional reassurance, and recognition campaigns were described as critical in sustaining workforce motivation. These practices align with evidence from high-stress healthcare contexts showing that transparent communication, two-way feedback mechanisms, and visible leadership reduce psychological distress and foster institutional trust (Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Ahmed et al., 2020). Embedding staff support strategies—such as psychological first aid, structured debriefings, and digital mental health tools—into routine operations can mitigate burnout and strengthen long-term team cohesion (West et al., 2016; Gilmartin et al., 2017).

Third, the use of digital platforms—including mobile apps, intranet pages, and internal video messages—enabled timely communication across diverse staff groups, particularly those without desktop access. However, hospitals also reported the risk of information overload and disengagement. This tension underscores the need for carefully balanced digital strategies. As highlighted in the literature, frequency, clarity, and channel appropriateness are key to sustaining attention and avoiding fatigue (Mehta et al., 2020; Sellnow and Seeger, 2021). Hospitals should invest not only in digital infrastructure but also in digital communication governance—defining when, how often, and through which tools key messages are delivered.

Finally, public communication played a decisive role in shaping trust, institutional credibility, and adherence to public health measures. Hospitals that proactively engaged the media and addressed misinformation reported stronger alignment with public expectations. These insights align with studies emphasising that proactive, transparent, and science-based messaging is critical to maintaining public trust during prolonged crises (Merchant and Lurie, 2020; Vraga and Bode, 2021). Integrating public communication strategies into crisis plans—such as by designating media-trained experts, pre-preparing templates, and monitoring public sentiment through social listening tools—can help healthcare institutions build trust capital before and during a crisis.

Limitations

This study has several limitations to consider. First, data were collected from a limited number of hospitals in Switzerland, predominantly in the German-speaking part, which may not fully capture the diversity of communication strategies used in other regions or healthcare systems. Additionally, while qualitative interviews provide detailed insights, they may introduce bias due to participants’ recall or social desirability, potentially leading some to emphasize positive aspects over challenges. However, the structured design of the interviews helped mitigate recall bias by clearly distinguishing between different phases, allowing for more robust and reliable data collection. The focus on hospitals during the unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic may also limit transferability of our findings to other types of crises. Moreover, our findings are largely descriptive and reflect only the perspective of hospital communication leads, meaning we cannot assess how messages were received or interpreted by staff, patients, or the public. Future research integrating the perspectives of message recipients is needed to provide a fuller understanding of communication effectiveness and impact. Additionally, interviews were conducted while the pandemic was still ongoing, which means some participants may have been in an acute crisis mindset, potentially limiting their ability to critically or retrospectively reflect on their experiences. Finally, although our sample covered all three linguistic regions of Switzerland and a range of institutional types, the qualitative nature of our study does not allows to represent the full diversity of Swiss hospitals in a generalizable way.

Future studies that integrate multiple perspectives and use mixed methods could help validate these findings and quantitatively assess the effectiveness of specific communication strategies on outcomes such as staff well-being, public trust, and operational efficiency.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic was not only a test of medical and operational capacity, but also a defining moment for the role of communication in healthcare institutions. Swiss hospitals, operating under sustained pressure, faced the dual challenge of ensuring that information remained clear, timely, and actionable, while also supporting the emotional well-being of staff and sustaining public trust. While many institutions demonstrated remarkable adaptability, communication strategies varied in effectiveness and scope, revealing gaps in preparedness, coordination, and long-term engagement.

Our findings highlight both the achievements and persistent tensions within hospital-based crisis communication. Leadership visibility, structured messaging, and digital tools played a critical role in fostering trust and ensuring continuity. Yet even these strategies were not always sufficient to overcome information fatigue, decentralised governance dynamics, or staff burnout. Hospitals were often required to pivot rapidly—recalibrating message frequency, rethinking digital delivery channels, and re-engaging both internal and external audiences in the face of prolonged uncertainty.

This study reinforces the understanding that effective crisis communication extends well beyond information dissemination. It involves building infrastructures that support emotional resilience, two-way engagement, and institutional trust—both during acute phases and in the quieter moments in between. Communication systems must be agile enough to adapt to new challenges, but also grounded in pre-established principles and feedback mechanisms. The lessons emerging from this study point to the need for healthcare organisations to embed communication planning into emergency preparedness frameworks, invest in leadership and staff capacity, and integrate digital and public-facing strategies in a coordinated, intentional manner.

In this sense, crisis communication is not a reactive task but a continuous organisational function—central to resilience, recovery, and the capacity to serve both healthcare workers and the public during future emergencies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (reference number EKNZ 2020-01306) for the studies involving humans because the study falls outside the scope of the Human Research Act and complies with the Helsinki Declaration. Participants could withdraw from the study at any moment and were assured of confidentiality and the secure handling of data. Identifying details were anonymized in transcripts and reports to protect participant privacy. Recordings and transcripts were stored on encrypted devices and will be securely deleted after the study’s completion. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the interviews were conducted via Zoom in accordance of the pandemic restrictions in place at the time. All participants provided oral informed consent prior to their participation.

Author contributions

ND: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MF: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a research grant awarded to SR and ND by the Swiss National Science Foundation (special call on coronaviruses, grant number 31CA30_196736).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their thanks to Dr. Claudia Zanini (Swiss Paraplegic Research) for her support in conducting interviews in the French-speaking region of Switzerland. They also express their gratitude to all interview participants for dedicating their time to our study despite the challenging circumstances.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT to support language editing and formatting during the preparation of this manuscript. All intellectual content, analysis, and interpretation were developed by the authors, who take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1672472/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CEO, Chief Executive Officer; EKNZ, Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz; FAQ, Frequently Asked Questions; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

Adini, B., Goldberg, A., Laor, D., Cohen, R., and Bar-Dayan, Y. (2007). Factors that may influence the preparation of standards of procedures for dealing with mass-casualty incidents. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 22, 175–180. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00004611

Ahmed, F., Zhao, F., and Faraz, N. A. (2020). How and when does inclusive leadership curb psychological distress during a crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 11:1898. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01898

Baetzner, A. S., Wespi, R., Hill, Y., Gyllencreutz, L., Sauter, T. C., Saveman, B.-I., et al. (2022). Preparing medical first responders for crises: a systematic literature review of disaster training programs and their effectiveness. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 30:76. doi: 10.1186/s13049-022-01056-8

Bloom, J. R., Martin, E. J., and Jones, J. A. (2021). Communication strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: unforeseen opportunities and drawbacks., in Seminars in Oncology, (Elsevier), 292–294. Available online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0093775421000580?casa_token=a54EHNZiYd8AAAAA:Ex02ur7wr_FkCKVQHTD5QQXrSUuFhFAX8QS0hSJtAXfHVeRkbsjTC8rB8MwlLdPxmGyuRr0 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Boes, S., Weisstanner, D., and Durvy, B. (2025). Health Systems in Action: Switzerland: 2024 edition. Available online at: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/18086897/health-systems-in-action/18986408/ (Accessed August 21, 2025).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cohen, D., and Crabtree, B. (2006). Semi-structured interviews. Robert wood johnson foundation qualitative research guidelines project. Retrieved July 15, 2025 from https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/COHEN%202006%20Semistructured%20Interview.pdf.

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Ongoing crisis communication: planning, managing, and responding. Sage. Available online at: https://books.google.ch/books?hl=it&lr=&id=E3fQ8EraOTIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=ngoing+crisis+communication:+Planning,+managing,+and+responding&ots=HeasuSPNNq&sig=JpiA-XYF3egKJL0jIXpBscB0kXI (Accessed November 29, 2024).

Ehrenzeller, S., Durovic, A., Kuehl, R., Martinez, A. E., Bielser, M., Battegay, M., et al. (2022). A qualitative study on safety perception among healthcare workers of a tertiary academic care center during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 11:30. doi: 10.1186/s13756-022-01068-0

Finset, A. (2008). Qualitative methods in communication and patient education research. Patient Educ Couns. 73, 1–2.

Gilmartin, H., Goyal, A., Hamati, M. C., Mann, J., Saint, S., and Chopra, V. (2017). Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers–a systematic literature review. Am. J. Med. 130:1219-e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.041

Grazioli, V. S., Tzartzas, K., Blaser, J., Graells, M., Schmutz, E., Petitgenet, I., et al. (2022). Risk perception related to COVID-19 and future affective responses among healthcare Workers in Switzerland: a mixed-methods longitudinal study. Int. J. Public Health 67:1604517. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604517

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Kennzahlen der Schweizer Spitäler (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.bag.admin.ch/de/kennzahlen-der-schweizer-spitaeler (Accessed August 21, 2025).

Mehta, J., Yates, T., Smith, P., Henderson, D., Winteringham, G., and Burns, A. (2020). Rapid implementation of Microsoft teams in response to COVID-19: one acute healthcare organisation’s experience. BMJ Health Care Inform. 27:e100209. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2020-100209

Merchant, R. M., and Lurie, N. (2020). Social media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus. JAMA 323, 2011–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4469

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., and Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847

Paakkari, L., and Okan, O. (2020). COVID-19: health literacy is an underestimated problem. Lancet Public Health 5, e249–e250. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30086-4

Paton, D., and Johnston, D. (2017). Disaster resilience: an integrated approach. Charles C Thomas Publisher. Available online at: https://books.google.ch/books?hl=it&lr=&id=oZknDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Disaster+Resilience:+An+Integrated+Approach.&ots=yF1n6BX4MD&sig=BoNLTrsThccwwaAvOkhdsbMpzKs (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Reynolds, B., and Seeger, W. M. (2005). Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J. Health Commun. 10, 43–55. doi: 10.1080/10810730590904571

Rosenbäck, R., and Eriksson, K. M. (2024). COVID-19 healthcare success or failure? Crisis management explained by dynamic capabilities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24:759. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11201-x

Rosenbaum, L. (2020). The untold toll — the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 2368–2371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2009984

Rubinelli, S., Häfliger, C., Fiordelli, M., Ort, A., and Diviani, N. (2023). Institutional crisis communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland. A qualitative study of the experiences of representatives of public health organizations. Patient Educ. Couns. 114:107813. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107813

Schlögl, M., Singler, K., Martinez-Velilla, N., Jan, S., Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A., Roller-Wirnsberger, R. E., et al. (2021). Communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: evaluation study on self-perceived competences and views of health care professionals. Eur Geriatr Med 12, 1181–1190. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00532-1

Schumacher, L., Dhif, Y., Bonnabry, P., and Widmer, N. (2023). Managing the COVID-19 health crisis: a survey of Swiss hospital pharmacies. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23:1134. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-10105-6

Sellnow, T. L., and Seeger, M. W. (2021). Theorizing crisis communication. John Wiley & Sons. Available online at: https://books.google.ch/books?hl=it&lr=&id=YGUQEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=Theorizing+Crisis+Communication&ots=sVU1rdeGF3&sig=3g1eC2SxmHzZDhgWkDWac2WQMWs (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Shanafelt, T. D., and Noseworthy, J. H. (2017). Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout., in Mayo Clin. Proc., (Elsevier), 129–146. Available online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025619616306255?casa_token=vWc8cy0mHyYAAAAA:QbNanOy2LKInhfonSAUNpOcNw99Vd800RBfnhO-Dcd2OZWdavMYzs3UU4WZc6QF8BH4LpfKh2tI (Accessed December 3, 2024).

Sturny, I. (2020). International health care system profiles: Switzerland. The Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/Switzerland (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Vraga, E. K., and Bode, L. (2021). Addressing COVID-19 misinformation on social media preemptively and responsively. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 396–403. doi: 10.3201/eid2702.203139

West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., Erwin, P. J., and Shanafelt, T. D. (2016). Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 388, 2272–2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

WHO (2009). “The WHO pandemic phases,” in pandemic influenza preparedness and response: A WHO guidance document, (World Health Organization). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK143061/ (Accessed February 18, 2025).

WHO. (2011). “Hospital emergency response checklist: an all-hazards tool for hospital administrators and emergency managers,” In hospital emergency response checklist: An all-hazards tool for hospital administrators and emergency managers. Available online at: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/who-349374 (Accessed November 29, 2024).

WHO. (2020). Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: Interim report, 27 august 2020. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/334048/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1-eng.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2024).

Keywords: crisis communication, hospital management, COVID-19, qualitative study, health services research

Citation: Diviani N, Fiordelli M, Ort A and Rubinelli S (2025) From preparedness to adaptation: Swiss hospitals’ communication strategies in a prolonged crisis. Front. Commun. 10:1672472. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1672472

Edited by:

Leah M. Omilion-Hodges, Western Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Michalis Tastsoglou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceTania Desmet, Ghent University Hospital, Belgium

Copyright © 2025 Diviani, Fiordelli, Ort and Rubinelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicola Diviani, bmljb2xhLmRpdmlhbmlAcGFyYXBsZWdpZS5jaA==

Nicola Diviani

Nicola Diviani Maddalena Fiordelli

Maddalena Fiordelli Alexander Ort

Alexander Ort Sara Rubinelli

Sara Rubinelli