- 1Department of Health Communication, School of Public Health, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Department of Medical Communication, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hoshi University, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Division, Department of Human Sciences, Center for Liberal Arts and Sciences, Iwate Medical University, Iwate, Japan

We aimed to propose a new conceptualization of health communication that mitigates the limitations of traditional one-way models by introducing a relational, narrative-based approach that emphasizes mutual understanding. This paper critiques existing definitions and proposes an alternative framework by reviewing interdisciplinary literature on Narrative Medicine, narrative identity theory, and health communication research. The paper introduces “narrative intersection” as a concept that describes how divergent narratives engage in dialogic meaning-making. Health communication is redefined as the study and practice of opening closed narratives and co-creating shared meanings through narrative intersections to improve health. This redefinition shifts focus from merely delivering information to fostering dialog and co-constructing meaning. It provides a unifying framework for diverse domains, such as clinical communication and public health messaging, while addressing issues such as resistance to evidence-based recommendations and the spread of misinformation. Narrative intersections offer a grounded, ethically responsive, and practically relevant framework for advancing health communication by emphasizing the importance of dialog, narrative contexts, and the structural conditions that shape the voices that are heard.

1 Introduction

Health communication is central to medicine, public health, and policy because it directly influences how individuals and communities understand health information and make decisions (Schiavo, 2013). However, even when accurate and timely information is provided, people do not always respond as expected. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities released evidence-based recommendations on vaccines, mask-wearing, and physical distancing. Yet misinformation on social media spread more rapidly than scientific facts, fueling confusion and distrust (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2023). Similarly, in the clinical context, patients with chronic illnesses often report that their experiences are overlooked or misunderstood by healthcare professionals, leading to frustration, withdrawal, and poor adherence (Cheston, 2022; Zhang, 2024). These challenges illustrate that effective health communication cannot be reduced to simply delivering accurate messages. It requires engagement with people’s experiences, cultural backgrounds, and emotional realities.

In this study, we propose a redefinition of health communication that addresses these limitations. We conceptualize humans as narrative beings who understand themselves and the world through stories. Building on this perspective, we introduce the concept of “narrative intersection,” a dialogical process in which divergent narratives—whether those of patients, clinicians, or communities—interact and generate new shared meanings. From this viewpoint, health communication can be defined as the study and practice of opening closed narratives and co-creating shared meanings through narrative intersections to improve health.

This redefinition shifts the focus of health communication away from message transmission and toward relational meaning-making. It underscores the importance of dialog, context, and ethics in clinical practice and public health communication. By centering on narrative intersection, we aim to provide a unifying framework that advances theory and offers practical guidance for addressing urgent challenges such as resistance to evidence-based recommendations, the spread of misinformation, and the marginalization of patient voices.

2 The limitations of traditional health communication models: moving beyond one-way transmission

Health communication has traditionally been defined as the unidirectional transmission of information from experts to nonexperts (Ee et al., 2003). For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines health communication as “the study and use of communication strategies to inform and influence decisions and actions to improve health” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). Similarly, Healthy People 2010 described health communication as “the art and technique of informing, influencing, and motivating individual, institutional, and public audiences about important health issues,” portraying it as a technique for promoting understanding and action on health concerns (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2005). The National Cancer Institute (NCI) includes a wide range of health communication activities, from patient–provider interactions and public campaigns to policy advocacy and media engagement, but primarily emphasizes outcomes for the receiver, such as increasing knowledge and awareness, influencing perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes, and prompting action (National Cancer Institute, 2001).

Thus, the core of health communication is often understood as delivering accurate information to induce behavioral changes. Even in the most comprehensive definition proposed by Schiavo, based on an analysis of approximately 20 existing definitions, although considerations of bidirectionality and empowerment are evident, a degree of unidirectional thinking still appears to persist (e.g., to influence, engage, empower, and support individuals, and communities) (Schiavo, 2013).

However, this one-way model has several limitations. First, it tends to disregard the interpretive contexts of recipients, including their cultural backgrounds, personal beliefs, and prior experiences (Han, 2013; Ko, 2016; Schöps et al., 2023). For example, a patient may hear the same medical advice as others but interpret it differently because of past illnesses or cultural traditions. Second, it is poorly suited to patient-centered care, where mutual understanding and respect for patient values are critical for effective decision-making (Siebinga et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2024; Zhang, 2024). If a patient says, “This illness has taken away my daily life,” and the physician only replies, “Your test results are normal,” the communication fails to support the patient’s needs. Third, in today’s multivocal and participatory media environment, unidirectional communication fails to address the dialogical and decentralized ways in which health narratives are exchanged and contested (Neylan et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Ma and Ma, 2025). For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, scientific information about vaccines frequently clashed with community beliefs and rumors on social media platforms (Smith et al., 2023).

These limitations are both practical and epistemological. Most existing definitions of health communication are implicitly grounded in a positivist orientation aligned with evidence-based medicine, which assumes that objective data and standardized messages can guide universally appropriate decisions and behaviors (Greenhalgh et al., 2014). However, this perspective overlooks the interpretive processes through which individuals engage with health information within the context of their life narratives. In contrast, Narrative Medicine emphasizes the storied nature of human understanding and the importance of attending to patients’ lived experiences, values, and meanings (Greenhalgh and Hurwitz, 1999; Charon, 2001; Zaharias, 2018a,b). From this viewpoint, effective communication is not simply delivering evidence-based content, but engaging in a dialogical process that honors narrative complexity and fosters shared understanding (Côté, 2024; Palla et al., 2024).

While classical definitions of health communication have emphasized one-way transmission, contemporary practice already encompasses robust dialogic and participatory strands. Examples include shared decision making, co-design of health services, community engagement, and patient and public involvement initiatives that emphasize mutual understanding and empowerment. Our critique therefore targets the conceptual default embedded in many formal definitions rather than current practice as a whole. The framework of narrative intersection is intended to integrate these dialogic efforts within a broader model that specifies when and how directive and relational modes can be combined most effectively.

3 Narrative-based foundations of health communication: addressing the challenge of divergent narratives

Human beings are fundamentally narrative in nature—homo narrans (Niles, 1999). We make sense of ourselves and the world through our stories (Fisher, 1984; Bruner, 2004; Adler and McAdams, 2007; Lind et al., 2025). Empirical studies support this view by demonstrating the association between how individuals construct life stories and their physical and psychological well-being (Adler et al., 2015, 2016; Iannello et al., 2018; Thomsen et al., 2025). These perspectives underscore that narrative is not merely a form of expression, but a primary mode of understanding, identity construction, and health-related meaning-making.

However, in practice, engaging in divergent narratives poses a major challenge to communication. Narratives are shaped by unique experiences, values and cultural contexts (McAdams, 2001; Adler and McAdams, 2007; Thomsen et al., 2025). Consequently, patients’ stories often diverge from those of clinicians. This divergence is known as “narrative mismatch” (Allegretti et al., 2010). For example, patients with chronic pain may describe their suffering in existential terms, whereas physicians primarily respond to biomedical categories (Blease et al., 2017; Cheston, 2022). When such accounts are overlooked, patients may feel ignored or invalidated, which can compromise rapport and quality of care (Wakefield et al., 2022).

Importantly, this discrepancy is not limited to clinical practice. Public health communications also encounter narrative divergence. Scientific narratives may conflict with community-held beliefs and cultural worldviews, necessitating dialogical bridge-building rather than top-down persuasion alone (Engebretsen and Baker, 2023). These patterns reaffirm the need to shift from health communication as information delivery to communication as relational meaning-making. In this view, the ability to engage across narrative boundaries and co-create meaning is not a peripheral skill, but a central component of communicative competence in healthcare (Charon, 2008; Zaharias, 2018a,b). This is the conceptual and ethical terrain on which narrative intersection operates, a framework that we elaborate on in the next section.

4 Defining health communication through narrative intersection: co-creating meaning across divergent perspectives

Building on the preceding discussion, we define health communication as “the study and practice of supporting individuals and communities by opening closed narratives and co-creating shared meaning through narrative intersection to improve health.” This redefinition marks a shift from one-way message delivery to mutual dialogical engagement grounded in the narrative nature of human understanding.

We use closed narrative to denote an account that (a) excludes alternative framings, (b) resists uptake of disconfirming or complementary information, and (c) confines next actions to a narrow, predetermined script. Conversely, a narrative is opened when at least two of the following markers can be observed during interaction: stance shift (acknowledging uncertainty or multiplicity), reframing (introducing a new interpretive lens), uptake cues (active paraphrasing or echoing), option-set expansion (joint articulation of multiple next steps), and shared language emergence (borrowing each other’s words). These five indicators function as minimal diagnostic criteria for identifying narrative intersection.

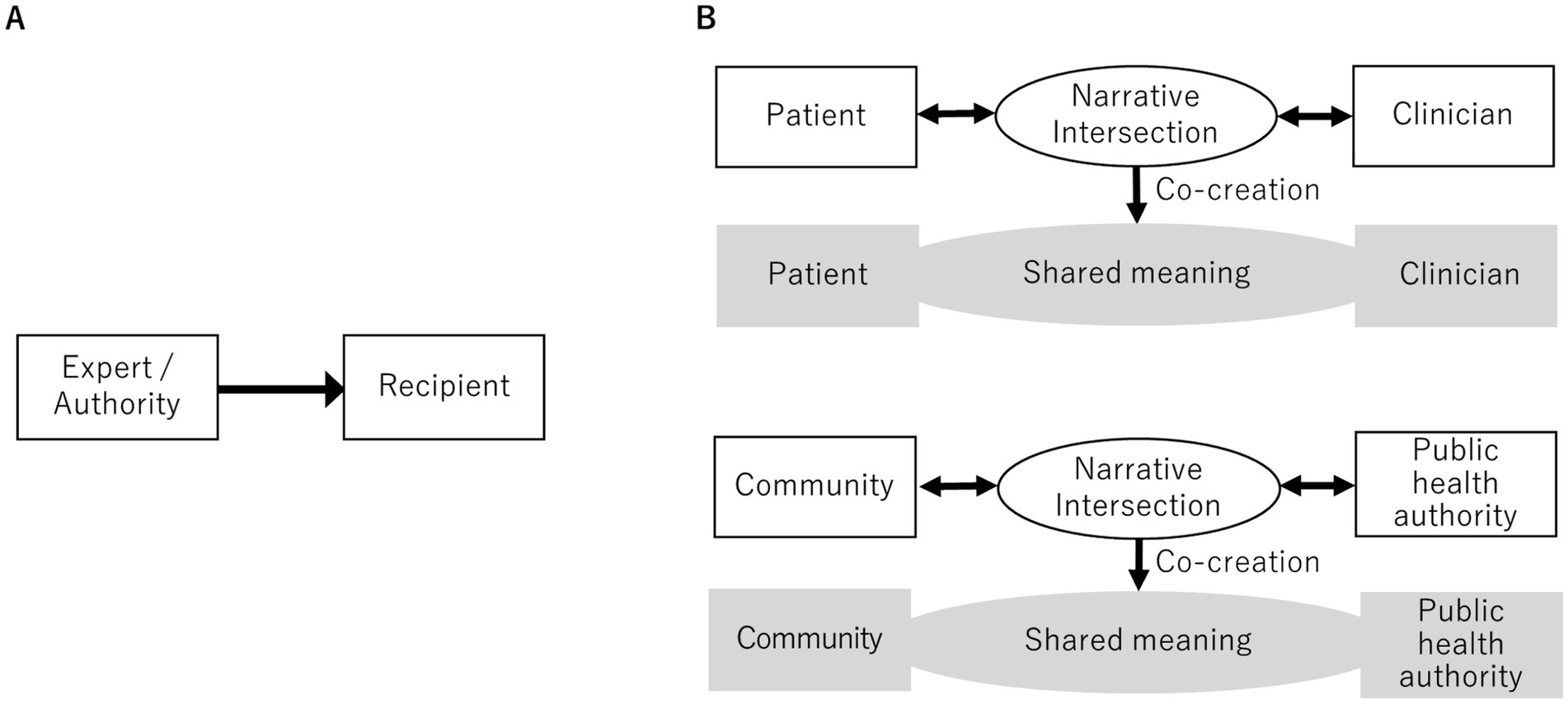

Figure 1 illustrates this conceptual shift. Panel A shows the traditional one-way model, in which information flows from experts to recipients. Panel B contrasts this with the narrative intersection model in which patients, clinicians, communities, and authorities bring their stories together and create a new understanding.

Narrative intersection means that divergent stories—whether clinical, personal, or cultural—encounter each other and generate new meanings. In other words, communication becomes a space in which stories clash, converge, and evolve into interpretations that no single voice can produce. This process is of ethical significance. Treating patient stories as valid knowledge can counter not only the structural injustice between patients and healthcare providers but also specific forms of epistemic injustice, such as testimonial and hermeneutical exclusion (Kidd and Carel, 2017; Jonas et al., 2025). Recognizing and engaging with patients’ stories affirms their dignity and ensures equity in communicative relationships. For example, when a patient says, “My life is over because of this illness,” a clinician’s engagement may open space for a new meaning, such as, “This experience, though painful, can still hold value”(de Sire et al., 2023). Clinicians may also reshape their professional narratives through these encounters, broadening their care beyond biomedical logic (Huang et al., 2021). Such reciprocal transformations demonstrate that narrative intersection is not only a practical tool, but also an ethical commitment to justice, respect, and the recognition of patients as knowers.

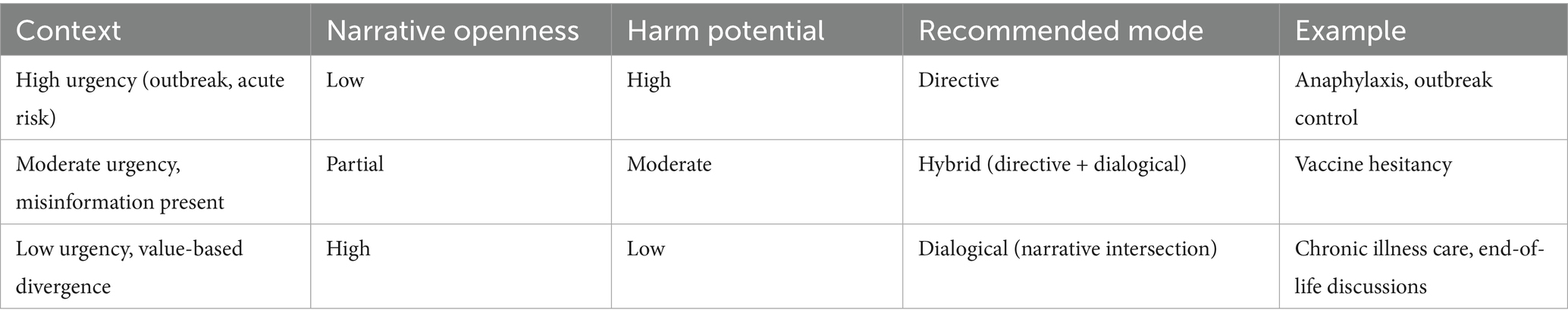

Narrative intersection is not intended to replace directive communication in all contexts. In time-critical, high-consensus risk communication—for instance, outbreak control or anaphylaxis management—rapid one-way messages are primary. In contrast, when values, identity, or lived experience are central (e.g., chronic illness, end-of-life care), narrative intersection becomes the preferred mode, facilitating mutual understanding and trust.

5 Theoretical and practical implications of narrative intersection: reconstructing health communication for a complex world

This section outlines the theoretical and practical implications of redefining health communication through narrative intersections. The following discussion first considers the theoretical contribution of this framework from an analytical perspective and then turns to its practical applications in clinical practice and public health communication.

Previous studies have emphasized the role of narratives in health. Kleinman (1988) noted that patients and clinicians have different explanatory models of illness. Narrative Medicine highlights the importance of listening to stories about illness (Charon, 2008). Frank (2013) described the typologies of illness narratives (Frank, 2013). Research on narrative persuasion has examined how stories shape attitudes (Dudley et al., 2023; Okuhara et al., 2023).

Our contribution goes further. Rather than concentrating on the content or persuasive power of individual stories, we highlight the relational process by which divergent stories meet and transform into one another. For example, a patient with chronic pain may say, “The tests show nothing is wrong, but this pain controls my whole life.” When a clinician acknowledges this experience and reframes it as, “Your pain is real, and together we can find ways to manage it,” the resulting dialog generates a new, shared meaning that validates the patient’s story (Naldemirci et al., 2021; Rosen, 2021). Theoretically, this example illustrates that narratives are neither static nor self-contained but relational and dynamic. Meaning arises through these encounters, where differences and conflicts become opportunities for transformation. This view resonates with dialogical perspectives (Bakhtin, 1981) and social constructionist accounts of meaning-making, which stress that understanding is always co-produced within an interaction. By adopting narrative intersection as an analytical lens, health communication shifts from focusing on isolated narratives to examining the dynamics of encounters, offering a more comprehensive framework for both theory and practice.

Narrative intersections are highly relevant in clinical practice. Shared decision-making, for example, is often framed as a rational weighting of risks and benefits (Elwyn et al., 2013; Siebinga et al., 2022). However, in reality, patients and clinicians enter these conversations with different stories about the illness, treatment, and future (Thomas et al., 2020; Waddell et al., 2021). For example, a patient with a chronic illness may prioritize maintaining daily activities, whereas the clinician may emphasize treatment outcomes alone (Evangelidis et al., 2017). By explicitly acknowledging and negotiating these divergent narratives, decision making can move beyond abstract statistics to a process of co-constructing meaning that respects patient values. Thus, the narrative intersection provides a practical framework for improving trust, adherence, and satisfaction with clinical encounters.

Narrative Medicine and dialogic theories have powerfully underscored the ethical and relational value of listening to patients’ stories. However, these frameworks often remain at the level of ethos—emphasizing why dialog matters—without specifying how to recognize, facilitate, and evaluate it in practice. The concept of narrative intersection advances this conversation by offering an interactional process focus with concrete recognition criteria (e.g., stance shifts, reframing, uptake cues) and assessment possibilities for when stories genuinely engage and co-create shared meaning. Thus, narrative intersection transforms a narrative attitude into an operational framework for observing and cultivating dialogical meaning-making.

This framework also extends to public health communication. For example, it clarifies why accurate health information is often rejected, whereas misinformation spreads more easily (Zhou et al., 2021; Vellani et al., 2023; Langdon et al., 2024). The issue is not only the content of the message but also its fit with people’s existing narratives. When information clashes with the recipient’s worldview, it is likely to be rejected. When dialog creates a shared narrative, it opens space for change. Reproductive health and aging involve competing perspectives shaped by cultural values and social experiences. Discussions about reproductive rights often pit biomedical risk framing against community-based narratives of morality and family (Parker, 2020). In aging societies, public health advice regarding frailty or dementia may conflict with older adults’ stories of independence and dignity (Gheorghe et al., 2024; Marnfeldt and Wilber, 2025). Narrative intersections help explain these clashes and provide a dialogical approach to address them. By engaging communities in mutual storytelling, public health professionals can create shared narratives that foster legitimacy and trust among diverse populations.

This redefinition unifies the diverse domains of health communication through a single lens. Clinical communication, community-based initiatives, and public health can all be viewed as sites of narrative intersection and meaning co-creation. In patient–provider communication, a narrative intersection may explain why trust and treatment adherence improve when dialog occurs (Waddell et al., 2021). Peer communities and online forums also function as sites where patients share stories to inform, validate, and connect with each other (Kohl et al., 2024; Aldarwesh, 2025). Public health communication faces similar dynamics when scientific messages clash with community worldviews, such as in vaccine communication (Dickinson et al., 2025). In any of these cases, the narrative intersection offers a dialogical approach that enables mutual storytelling, builds trust, and fosters reciprocal understanding. This is especially important for marginalized communities, whose voices have often been excluded.

While narrative intersection emphasizes mutual understanding, it does not imply moral equivalence among all narratives. Two ethical guardrails guide its responsible use:

1. Integrity guardrail: Narrative intersection must never compromise factual accuracy, public safety, or human rights. Dialog aims to understand harmful narratives, not to endorse them.

2. Equity guardrail: Engagement should prioritize marginalized voices and protect those harmed by misinformation or discrimination.

In situations involving misinformation, clinicians and public health practitioners should distinguish between understanding the worldview behind a harmful claim and validating the claim itself. Narrative intersection can be used to uncover the emotional or identity-based concerns that sustain misinformation (e.g., fear, distrust, belonging), while directive communication remains essential when false claims pose imminent harm.

Table 1 shows the decision grid. This grid provides a practical heuristic: as urgency and harm potential increase, communication should shift toward directive clarity; as narrative openness increases, dialogical engagement becomes more appropriate. These ethical boundaries ensure that narrative intersection strengthens, rather than undermines, evidence-based communication.

Finally, certain challenges remain. Methodological innovation is required, as tools to assess the degree of narrative disjunction or shared meaning are underdeveloped. Future work should focus on qualitative and process-oriented approaches, such as narrative, dialogical, or conversation analyses, to evaluate meaning co-creation in real settings. Interventions that facilitate narrative intersections, especially in clinical and public health contexts, should be designed and tested.

However, some theoretical questions remain. Narratives are socially situated and shaped by broader structures. Power asymmetries, cultural hegemony, stigma, and systemic discrimination influence which narratives are heard or dismissed (Rosen, 2021). Future research should examine how these structural conditions shape the possibility of narrative intersection. By addressing these barriers, the framework could be refined to promote equitable and inclusive communication.

6 Conclusion

This study argues that health communication must be redefined to address the complexity of contemporary health challenges. Traditional transmission models, while valuable in certain contexts, are limited because they reduce communication to the delivery of information. Our analysis shows that such models overlook the interpretive, relational, and ethical dimensions of how people engage with healthcare.

We propose narrative intersection as a unifying perspective that reframes health communication as the co-creation of meaning across divergent stories. This framework highlights that communication is not a linear process, but a dialogical encounter in which new understandings emerge. By recognizing human beings as fundamentally narrative in nature, this redefinition integrates insights from multiple domains and provides a more comprehensive foundation for research and practice.

Redefining health communication through narrative intersections provides a unified, ethically grounded framework. It moves the field beyond one-way transmission to dialogical meaning-making and affirms dignity, equity, and respect for diverse voices. This redefinition reorients health communication toward a more inclusive, reflexive, and human-centered future, marking a necessary shift in the 21st century through mutual understanding via narrative intersections.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HO: Writing – review & editing. RY: Writing – review & editing. YK: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI (grant number: 25K13483).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, J. M., Lodi-Smith, J., Philippe, F. L., and Houle, I. (2016). The incremental validity of narrative identity in predicting well-being: a review of the field and recommendations for the future. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 20, 142–175. doi: 10.1177/1088868315585068

Adler, J. M., and McAdams, D. P. (2007). Time, culture, and stories of the self. Psychol. Inq. 18, 97–99. doi: 10.1080/10478400701416145

Adler, J. M., Turner, A. F., Brookshier, K. M., Monahan, C., Walder-Biesanz, I., Harmeling, L. H., et al. (2015). Variation in narrative identity is associated with trajectories of mental health over several years. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108, 476–496. doi: 10.1037/a0038601

Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Iwelunmor, J., Munodawafa, D., Ford, C. L., Oni, T., Agyemang, C., et al. (2020). Culture matters in communicating the global response to COVID-19. Prev. Chronic Dis. 17:E60. doi: 10.5888/PCD17.200245

Aldarwesh, A. (2025). Journey of hope for patients with fibromyalgia: from diagnosis to self-management—a qualitative study. Healthcare 13:142. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13020142

Allegretti, A., Borkan, J., Reis, S., and Griffiths, F. (2010). Paired interviews of shared experiences around chronic low back pain: classic mismatch between patients and their doctors. Fam. Pract. 27, 676–683. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq063

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981) in The dialogic imagination: Four essays. ed. M. Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press).

Blease, C., Carel, H., and Geraghty, K. (2017). Epistemic injustice in healthcare encounters: evidence from chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Med. Ethics 43, 549–557. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103691

Charon, R. (2001). Narrative medicine a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 286, 1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Charon, R. (2008). Narrative medicine: honoring the stories of illness. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cheston, K. (2022). (Dis)respect and shame in the context of ‘medically unexplained’ illness. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 28, 909–916. doi: 10.1111/jep.13740

Côté, C. I. (2024). A critical and systematic literature review of epistemic justice applied to healthcare: Recommendations for a patient partnership approach. Med Health Care Phil 27, 455–477. doi: 10.1007/s11019-024-10210-1

de Sire, A., Marotta, N., Drago Ferrante, V., Calafiore, D., and Ammendolia, A. (2023). Effects of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos and Behçet’s syndromes: a paradigmatic case report according to the narrative medicine. Disabil. Rehabil. 46, 4687–4694. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2023.2283104

Dickinson, R., Makowski, D., van Marwijk, H., and Ford, E. (2025). Interventions for combating COVID-19 misinformation: a systematic realist review. PLoS One 20:e0321818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321818

Dudley, M. Z., Squires, G. K., Petroske, T. M., Dawson, S., and Brewer, J. (2023). The use of narrative in science and health communication: a scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 112:107752. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107752

Ee, R., Lee, G., and Garvin, T. (2003). Moving from information transfer to information exchange in health and health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 56, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00045-x

Elwyn, G., Scholl, I., Tietbohl, C., Mann, M., Edwards, A. G., Clay, C., et al. (2013). “Many miles to go.”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 13:S14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S14

Engebretsen, E., and Baker, M. (2023). Health preparedness and narrative rationality: a call for narrative preparedness. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 12:7532. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2023.7532

Evangelidis, N., Tong, A., Manns, B., Hemmelgarn, B., Wheeler, D. C., Tugwell, P., et al. (2017). Developing a set of Core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: an international Delphi survey. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 70, 464–475. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.029

Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: the case of public moral argument. Commun. Monogr. 51, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/03637758409390180

Frank, A. (2013). The wounded storyteller: body, illness, and ethics. 2nd Edn. London: University of Chicago Press.

Gheorghe, A. C., Bălășescu, E., Hulea, I., Turcu, G., Amariei, M. I., Covaciu, A. V., et al. (2024). Frailty and loneliness in older adults: a narrative review. Geriatrics 9:119. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics9050119

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J., Maskrey, N., Brassey, J., Burch, D., Burton, M., et al. (2014). Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 348:g3725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3725

Greenhalgh, T., and Hurwitz, B. (1999). Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ 318, 48–50. Available at:. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.48

Han, P. K. J. (2013). Conceptual, methodological, and ethical problems in communicating uncertainty in clinical evidence. Med. Care Res. Rev. 70, 14S–36S. doi: 10.1177/1077558712459361

Hu, Z., Wu, C., and Sacco, P. L. (2023). Editorial: public health policy and health communication challenges in the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. Front. Public Health 11:1251503. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1251503

Huang, C. D., Jenq, C. C., Liao, K. C., Lii, S. C., Huang, C. H., and Wang, T. Y. (2021). How does narrative medicine impact medical trainees’ learning of professionalism? A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 21:391. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02823-4

Iannello, P., Biassoni, F., Bertola, L., Antonietti, A., Caserta, V. A., and Panella, L. (2018). The role of autobiographical story-telling during rehabilitation among hip-fracture geriatric patients. Eur. J. Psychol. 14, 424–443. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v14i2.1559

Jiang, S., Wu, Z., Zhang, X., Ji, Y., Xu, J., Liu, P., et al. (2024). How does patient-centered communication influence patient trust?: the roles of patient participation and patient preference. Patient Educ. Couns. 122:108161. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2024.108161

Jonas, L., Bacharach, S., Nightingale, S., and Filoche, S. (2025). Under the umbrella of epistemic injustice communication and epistemic injustice in clinical encounters: a critical scoping review. Ethics Med. Public Health 33:101039. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2024.101039

Kidd, I. J., and Carel, H. (2017). Epistemic injustice and illness. J. Appl. Philos. 34, 172–190. doi: 10.1111/japp.12172

Ko, H. (2016). In science communication, why does the idea of a public deficit always return? How do the shifting information flows in healthcare affect the deficit model of science communication? Public Underst. Sci. 25, 427–432. doi: 10.1177/0963662516629746

Kohl, G., Koh, W. Q., Scior, K., and Charlesworth, G. (2024). “It’s just getting the word out there”: self-disclosure by people with young-onset dementia. PLoS One 19:e0310983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0310983

Kleinman, A. (1988). The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. Basic Books. New York.

Langdon, J. A., Helgason, B. A., Qiu, J., and Effron, D. A. (2024). “It’s not literally true, but you get the gist:” how nuanced understandings of truth encourage people to condone and spread misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 57:101788. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2024.101788

Lind, M., Cowan, H. R., Adler, J. M., and McAdams, D. P. (2025). Development and validation of the narrative identity self-evaluation scale (NISE). J. Pers. Assess. 107, 292–305. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2024.2425663

Ma, Z., and Ma, R. (2025). The role of narratives in countering health misinformation: a scoping review of the literature. Health Commun. 40, 2353–2364. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2025.2453451

Marnfeldt, K., and Wilber, K. (2025). The safety-autonomy grid: a flexible framework for navigating protection and Independence for older adults. Gerontologist 65:gnaf111. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaf111

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 100–122. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

Naldemirci, Ö., Britten, N., Lloyd, H., and Wolf, A. (2021). Epistemic injustices in clinical communication: the example of narrative elicitation in person-centred care. Sociol. Health Illn. 43, 186–200. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13209

Neylan, J. H., Patel, S. S., and Erickson, T. B. (2022). Strategies to counter disinformation for healthcare practitioners and policymakers. World Med. Health Policy 14, 428–436. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.487

Niles, J. D. (1999). Homo narrans: the poetics and anthropology of oral literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Okuhara, T., Kagawa, Y., Okada, H., Tsunezumi, A., and Kiuchi, T. (2023). Intervention studies to encourage HPV vaccination using narrative: a scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 111:107689. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107689

Parker, W. J. (2020). The moral imperative of reproductive rights, health, and justice. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 62, 3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.07.006

Palla, I., Turchetti, G., and Polvani, S. (2024). Narrative Medicine: theory, clinical practice and education-a scoping review. BMC Health Ser Res 24:1116. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11530-x

Rosen, L. T. (2021). Mapping out epistemic justice in the clinical space: using narrative techniques to affirm patients as knowers. Philos. Ethics Humanit. Med. 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s13010-021-00110-0

Schiavo, R. (2013). Health communication: from theory to practice. 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schöps, A. M., Skinner, T. C., and Fosgerau, C. F. (2023). Time to move beyond monological perspectives in health behavior change communication research and practice. Front. Psychol. 14:1070006. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1070006

Siebinga, V. Y., Driever, E. M., Stiggelbout, A. M., and Brand, P. L. P. (2022). Shared decision making, patient-centered communication and patient satisfaction – a cross-sectional analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 2145–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.03.012

Smith, R., Chen, K., Winner, D., Friedhoff, S., and Wardle, C. (2023). A systematic review of COVID-19 misinformation interventions: lessons learned. Health Aff. 42, 1738–1746. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00717

Thomas, A., Kuper, A., Chin-Yee, B., and Park, M. (2020). What is “shared” in shared decision-making? Philosophical perspectives, epistemic justice, and implications for health professions education. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. (Blackwell Publishing Ltd) 26, 409–418. doi: 10.1111/jep.13370

Thomsen, D. K., Cowan, H. R., and McAdams, D. P. (2025). Mental illness and personal recovery: a narrative identity framework. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 116:102546. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2025.102546

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2005). Healthy people 2010. Washington, DC.

Vellani, V., Zheng, S., Ercelik, D., and Sharot, T. (2023). The illusory truth effect leads to the spread of misinformation. Cognition 236:105421. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105421

Waddell, A., Lennox, A., Spassova, G., and Bragge, P. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in hospitals from policy to practice: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. 16:74. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01142-y

Wakefield, E. O., Belamkar, V., Litt, M. D., Puhl, R. M., and Zempsky, W. T. (2022). “There’s nothing wrong with you”: pain-related stigma in adolescents with chronic pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 47, 456–468. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab122

Wang, D., Zhou, Y., and Ma, F. (2022). Opinion leaders and structural hole spanners influencing Echo chambers in discussions about COVID-19 vaccines on social Media in China: network analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 24:e40701. doi: 10.2196/40701

Zaharias, G. (2018a). Narrative-based medicine and the general practice consultation: narrative-based medicine 2. Can. Fam. Physician 64, 286–290.

Zaharias, G. (2018b). What is narrative-based medicine? Narrative-based medicine 1. Can. Fam. Physician 64, 176–180.

Zhang, J. (2024). Fostering dialogue: a phenomenological approach to bridging the gap between the “voice of medicine” and the “voice of the lifeworld.”. Med. Health Care Philos. 27, 155–164. doi: 10.1007/s11019-024-10195-x

Keywords: health communication, definition, narrative, narrative medicine, story, patient-centered care

Citation: Okuhara T, Okada H, Yokota R and Kagawa Y (2025) Redefining health communication through narrative intersection: opening closed narratives and co-creating meaning. Front. Commun. 10:1672808. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1672808

Edited by:

Victoria Team, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Jiankun Gong, University of Malaya, MalaysiaIlaria Palla, Sant'Anna School of Advanced Studies, Italy

Esi Thompson Tani-Eshon, Indiana University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Okuhara, Okada, Yokota and Kagawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tsuyoshi Okuhara, b2t1aGFyYS1jdHJAdW1pbi5hYy5qcA==

Tsuyoshi Okuhara

Tsuyoshi Okuhara Hiroko Okada

Hiroko Okada Rie Yokota2

Rie Yokota2