- 1Medical University of Varna “Prof. Dr. Paraskev Stoyanov”, Department of Social Medicine and Healthcare Management, Varna, Bulgaria

- 2Ziv Medical Center, Safed, Israel

Background: Effective communication is critical in managing chronic low back pain, yet disparities exist in how healthcare professionals engage with patients. This study aimed to identify professional differences in relational and culturally responsive approaches to caring for patients with low back pain in Israel.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted at Ziv Medical Center in Safed, Northern Israel, involving 50 healthcare professionals—31 nurses and 19 physicians —who manage patients with low back pain in various clinical settings. Participants completed a structured Likert-scale questionnaire evaluating four key aspects of communication: empathy, patient engagement, shared decision-making, and cultural competence. Data were analyzed using Jamovi (version 2.6.23), and group differences between nurses and physicians were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Findings: Nurses exhibited higher empathy and communication skills compared to physicians, particularly in emotional support, patient reassurance, and encouraging patient concerns (p < 0.05). Physicians, however, excelled in clinical decision-making and providing detailed explanations of treatments (p < 0.05). A significant positive correlation was found between empathy and communication skills for both groups (r = 0.62, p = 0.004). Nurses demonstrated higher cultural competence and provided more culturally tailored care, with a positive correlation between cultural competence and individualized care (r = 0.58, p = 0.009).

Discussion and conclusions: The study underscores the critical role of both nurses and physicians in shaping patient care experiences. Nurses tend to excel in empathy and communication, whereas physicians primarily focus on clinical decision-making and treatment. The observed correlation between cultural competence and patient reassurance suggests that greater cultural sensitivity may enhance the patient experience and strengthen trust within the care relationship. These findings highlight the need for targeted training to improve communication, empathy, and cultural awareness across healthcare teams, thereby fostering stronger collaboration and more effective patient care.

Introduction

Low back pain is one of the most prevalent and disabling musculoskeletal conditions worldwide, affecting individuals across age groups and socioeconomic backgrounds (Wu et al., 2020). It remains the leading cause of years lived with disability globally and contributes substantially to healthcare utilization, lost productivity, and broader social and economic burdens (GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators, 2023). Approximately 90% of adults will experience low back pain at some point in their lives, with a significant portion developing chronic symptoms (Ge et al., 2022; Fatoye et al., 2019). In Israel, nearly one in five adults report chronic back pain, which is associated with work absenteeism, diminished quality of life, and increased reliance on medical services (Buskila et al., 2000; Daher and Dar, 2025; Sharon et al., 2022).

Despite extensive research and the development of clinical guidelines, outcomes for many low back pain patients remain suboptimal (Bogaert et al., 2024; Bishop et al., 2008). One critical factor influencing these outcomes is the quality of communication between healthcare providers and patients (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021). Health communication involves more than the delivery of information—it includes demonstrating empathy, assessing patient understanding, and fostering shared decision-making (Haverfield et al., 2018; Kovačević et al., 2024). This is especially vital in chronic conditions like low back pain, where ongoing symptoms necessitate long-term management. Clear, compassionate, and collaborative communication has been shown to enhance treatment adherence, improve clinical outcomes, and strengthen the therapeutic alliance (Sharkiya, 2023).

Effective communication also builds trust, enabling healthcare professionals to address the emotional and psychological dimensions of chronic pain (Sharma and Gupta, 2023; Tikkanen and Sundberg, 2024). Recognizing this, the World Health Organization emphasizes person-centered communication as a core component of high-quality health systems (World Health Organization, 2001). However, persistent gaps remain in how these skills are taught and practiced. Many patients report feeling excluded from decision-making or underserved in terms of emotional support (Krist et al., 2017; Hannawa et al., 2022; Ferreira et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2024). These concerns are reflected in the literature on Shared Decision-Making (SDM)—a collaborative approach in which clinicians and patients jointly select treatment options. Although SDM is central to person-centered care, its implementation is often constrained by time pressures, insufficient communication training, hierarchical clinical cultures, and disparities in health literacy (Waddell et al., 2021). Such barriers can leave patients marginalized in the decision-making process, particularly in chronic pain management, where long-term cooperation and mutual trust are essential (Elwyn et al., 2012; Légaré and Thompson-Leduc, 2014; Joseph-Williams et al., 2021; Stacey et al., 2017).

In Israel’s multicultural healthcare landscape, where providers and patients may differ in language, cultural norms, and expectations, the need for empathy, trust, and cultural competence is heightened. Physicians and nurses play a central role in chronic pain management but may differ in their communication styles, empathy levels, and cultural responsiveness due to differences in training, workload, and time spent with patients (Guidi and Traversa, 2021; Kwame and Petrucka, 2021). Nursing education traditionally emphasizes holistic, patient-centered, and relational aspects of care, fostering greater focus on empathy, emotional support, and ongoing interaction with patients. In contrast, medical training tends to prioritize diagnostic reasoning, evidence-based treatment, and efficiency, often within shorter and more structured clinical encounters (Watson, 2008; Haidet et al., 2002; Levinson et al., 2010). These distinctions, together with differences in workload and time allocation, may shape how nurses and physicians communicate with and engage patients.

This study examines the communication practices of healthcare professionals treating patients with low back pain, with attention to empathy, patient engagement, shared decision-making, and cultural competence. By comparing physicians and nurses, the research aims to inform targeted interventions and training programs to enhance communication quality and improve patient outcomes in pain management.

Theoretical framework

This study is grounded in a multidisciplinary conceptual framework that synthesizes theoretical models from patient-centered care, behavioral science, and cross-cultural health communication to investigate the interpersonal and contextual factors shaping healthcare professionals’ communication with patients experiencing chronic low back pain. Given the complexity of chronic pain as a condition influenced by biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors, the framework emphasizes the role of interpersonal processes, like communication, in mediating clinical outcomes, treatment adherence, and patient satisfaction.

At the core of this framework lies the Patient-Centered Care Model, a paradigm that reconceptualizes the clinician-patient interaction as a collaborative partnership rather than a unidirectional exchange of clinical expertise (Greene et al., 2012). Rooted in the work of Mead and Bower (2000) and further elaborated by Epstein and Street (2011), the Patient-Centered Care model underscores the importance of empathy, respect for patient autonomy, and engagement in shared decision-making. Rather than viewing communication as a transactional delivery of biomedical information, this approach frames it as a reciprocal, affective process that contributes to emotional support, empowerment, and therapeutic alliance (Varela et al., 2025). Within the management of chronic low back pain—where symptoms are persistent, subjective, and influenced by psychological distress—relational continuity and patient-provider trust become essential components of effective care (Fu et al., 2015; Dang et al., 2017; Lozano et al., 2025).

Complementing the relational perspective, Social Cognitive Theory provides a behavioral and psychological lens to understand how healthcare professionals develop, maintain, and adapt their communication practices. Originating from Bandura’s work (Bandura, 1986; Bandura, 2004), Social Cognitive Theory posits that human behavior is the result of dynamic and reciprocal interactions between cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors. This framework is particularly relevant in understanding provider behavior in clinical settings, where internal drivers such as attitudes, perceived self-efficacy, and prior experiences interact with external influences including institutional culture, peer behavior, workload, and patient demographics (Islam et al., 2023; Manjarres-Posada et al., 2020). In this context, communication competence is seen as both malleable and socially contingent—subject to reinforcement and improvement through feedback, modeling, and targeted training interventions (Cavaco et al., 2023; Reith-Hall and Montgomery, 2023).

To address the sociocultural dimensions of healthcare communication in multicultural environments such as Israel, the framework incorporates Campinha-Bacote’s Model of Cultural Competence in Healthcare Delivery (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). This model articulates five interdependent constructs essential for effective cross-cultural care: cultural awareness (self-examination of biases), cultural knowledge (understanding of cultural worldviews), cultural skill (ability to conduct culturally sensitive assessments), cultural encounters (interpersonal engagements with diverse populations), and cultural desire (intrinsic motivation to become culturally competent) (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). The model acknowledges that cultural competence is not a static attribute but an iterative developmental process. Research has shown that providers with higher cultural competence scores are more likely to establish rapport, elicit accurate symptom narratives, and improve adherence in culturally diverse patient populations (Handtke et al., 2019; Jongen et al., 2018).

Together, the three theoretical pillars converge on the premise that communication in chronic pain management is shaped by an interplay of personal dispositions, systemic influences, and cultural dynamics. The integration of the Patient-Centered Care model, Social Cognitive Theory, and the Campinha-Bacote model enables a nuanced exploration of how empathy, shared decision-making, and cultural responsiveness are operationalized in clinical practice. This framework also supports the examination of interprofessional differences, hypothesizing that variations in training, role expectations, and patient load may lead to differential communication behaviors between physicians and nurses.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study, conducted in accordance with the STROBE guideline, investigated differences in health communication competencies among healthcare professionals. Fifty participants, comprising 31 nurses and 19 physicians, were recruited from clinical departments such as emergency medicine and orthopedics, where patients with low back pain are routinely treated. Participants were eligible if they were actively involved in clinical practice and willing to complete the study questionnaire. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with informed consent obtained from all respondents before data collection. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling based on the availability and willingness of healthcare professionals actively involved in managing patients with low back pain. The sample size of 50 was determined by the number of eligible and consenting professionals available during the study period and was not derived from formal power analysis.

Setting

The study was conducted at Ziv Medical Center in Safed, Northern Israel, with a focus on clinical departments specializing in the management of low back pain.

Although the invitation to participate was distributed among several departments, the actual sample was primarily drawn from the Emergency Medicine Department (60%) and the Orthopedics Department (40%). This distribution reflects staff availability during the study period and may influence the generalizability of communication practices observed.

Instrument

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire developed to assess key domains of health communication among healthcare professionals. The instrument consisted of four sections: (1) expressions of empathy, (2) patient engagement and trust-building strategies, (3) shared decision-making practices, and (4) cultural competence in clinical settings. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), allowing respondents to indicate the extent of their agreement with various statements related to communication behaviors. Likert-scale responses were treated as ordinal data for nonparametric analysis. No items were transformed or grouped beyond the original domain scores.

The questionnaire was pilot tested in January with a small group (n = 9, five nurses and four physicians) of healthcare professionals to ensure clarity and content validity. Based on the feedback, minor adjustments were made to improve item wording and overall comprehension. Demographic information such as gender, professional role (e.g., physician or nurse), age group, and years of clinical experience was also collected to support subgroup analyses.

Procedure

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Ziv Medical Center, Safed, Northern Israel, prior to the initiation of data collection (Approval Number: ZIV-0072-24; Date: November 28, 2024). Data collection was conducted between February and March 2025. The questionnaire was administered electronically via Google Forms, based on the availability of healthcare professionals involved in the management of patients with low back pain, with a particular focus on staff from the Emergency Medicine Department. A small number of responses (<1%) were missing across several questionnaire items. All available data were retained in the analysis, and missing values were handled using available-case analysis. No imputation or data exclusion procedures were applied. Lastly, all responses were systematically recorded, entered into a Microsoft Excel database, and subsequently prepared for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Jamovi statistical software (version 2.6). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize group differences. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to compare responses between physicians and nurses, given the ordinal nature of the data. Effect sizes were calculated using rank biserial correlation (rrb) to assess the magnitude of significant differences. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied.

Results

A very small proportion of responses (<2%) were missing across some questionnaire items, leading to minor variations in the reported N values across tables.

Descriptive characteristics of participants in the study

The study sample comprised 50 participants, of whom 44% (n = 22) were male and 56% (n = 28) were female. The majority were nurses (62%, n = 31), while 38% (n = 19) were physicians. Most participants were between 35 and 45 years old (40%, n = 20), followed by those aged 25–35 years (30%, n = 15). Regarding clinical experience, the largest proportion had 10–20 years of experience (28%, n = 14), with a comparable distribution among those with 0–5 years (26%, n = 13) and 5–10 years (24%, n = 12) (Table 1).

Empathy declaration among health professionals

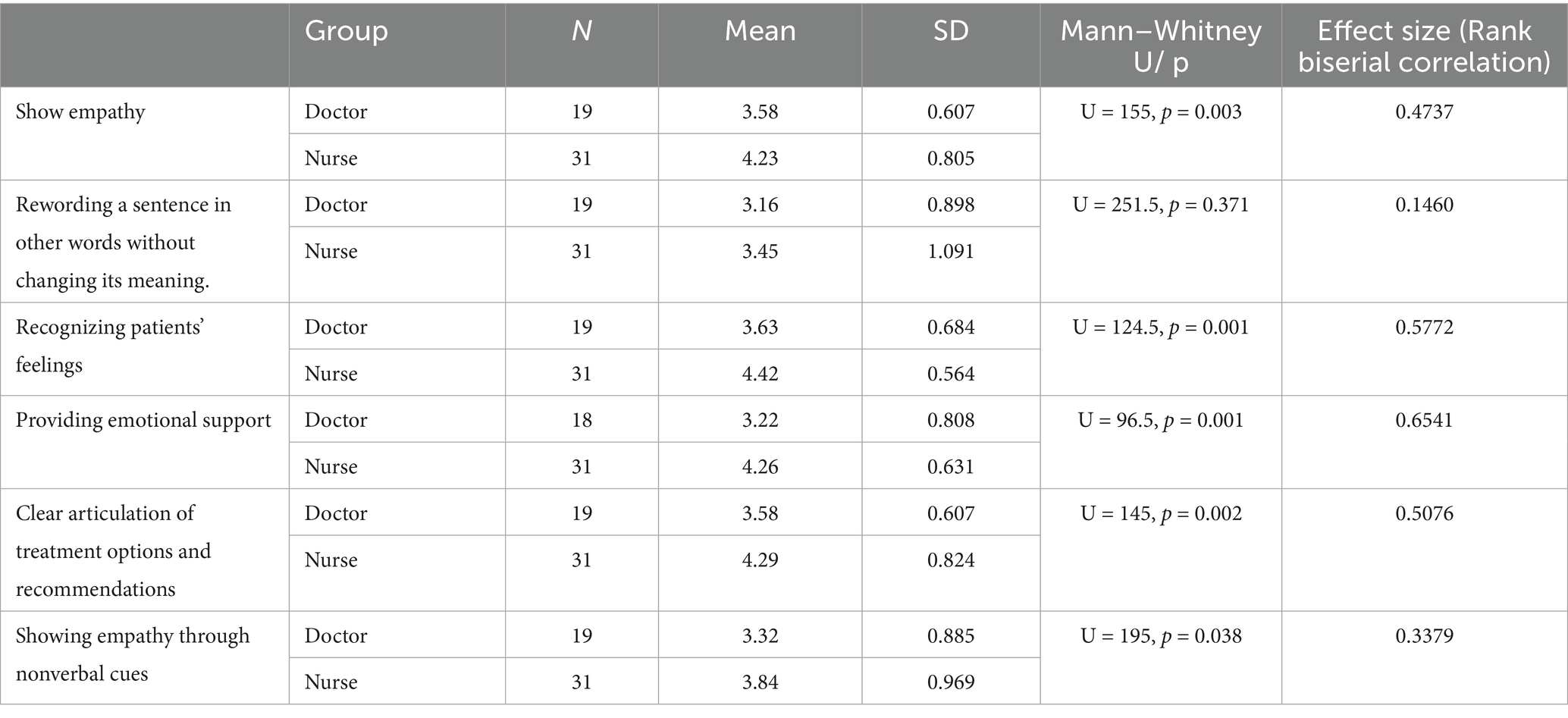

As shown in Table 2, nurses demonstrated significantly higher empathy than physicians across multiple domains, including showing empathy (U = 155, p = 0.003), recognizing patients’ feelings (U = 124.5, p = 0.001), providing emotional support (U = 96.5, p = 0.001), articulating treatment options (U = 145, p = 0.002), and using nonverbal cues (U = 195, p = 0.038). No significant difference was found in rewording sentences (U = 251.5, p = 0.371). Effect sizes were strong across all significant comparisons, with the largest for providing emotional support (0.65) and recognizing patients’ feelings (0.58). The smallest was for nonverbal cues (0.34) (Table 2).

Communication and patient engagement strategies

Nurses communicated more effectively than physicians in key areas, including encouraging patients to express concerns (U = 185.5, p = 0.023), providing reassurance (U = 163, p = 0.006), building trust (U = 185.5, p = 0.024), emphasizing transparency about treatment uncertainty (U = 126, p = 0.001), adapting communication styles (U = 189, p = 0.031), and incorporating shared decision-making (U = 136.5, p = 0.001). Physicians, however, were more likely to discuss the placebo effect with patients (U = 165, p = 0.007). Effect sizes were strongest for transparency (0.57) and shared decision-making (0.54), followed by the placebo effect discussion (0.44), encouraging concerns and trust-building (0.37), and the smallest for adapting communication (0.36) (Table 3).

Shared decision-making

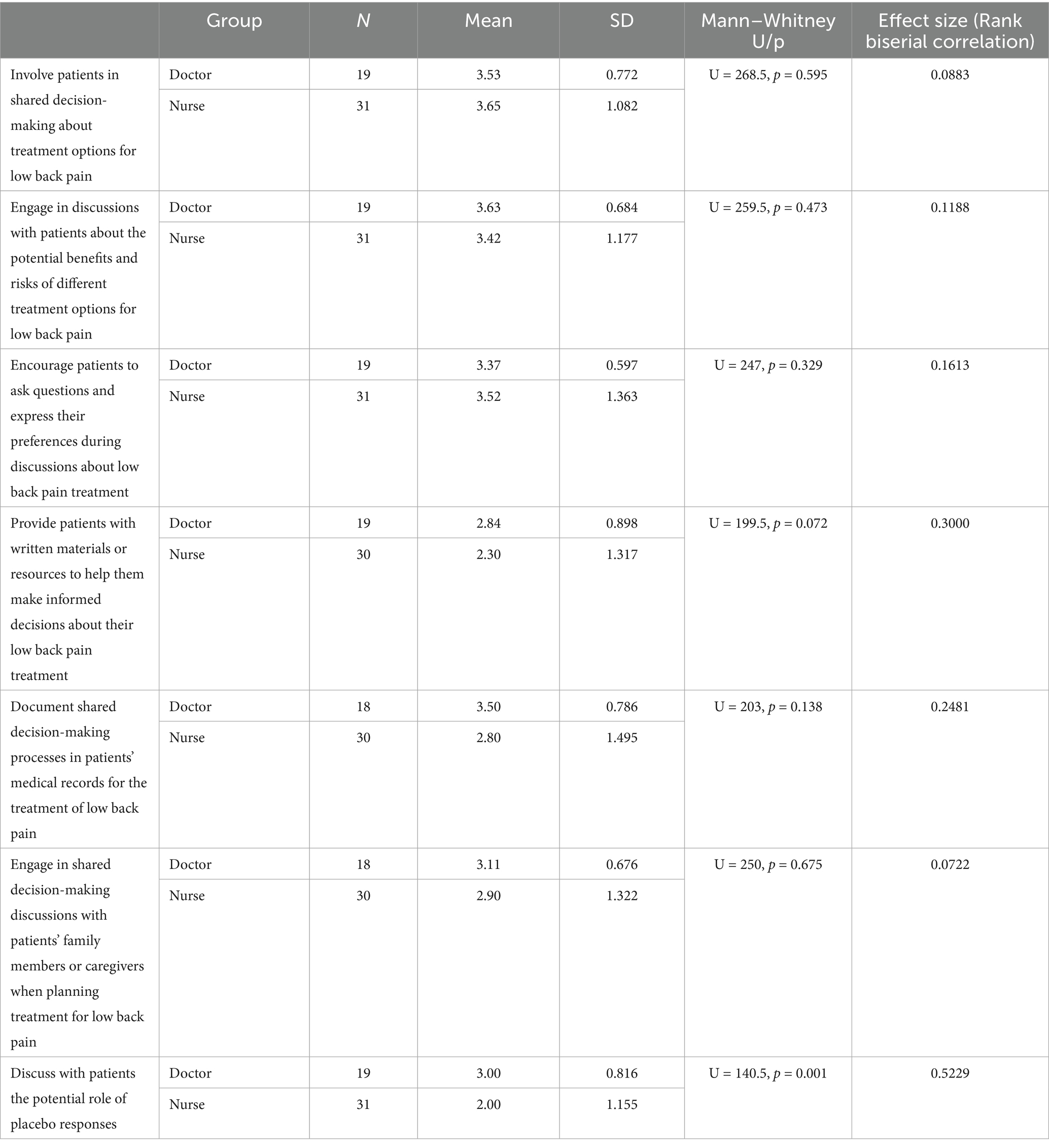

Physicians were significantly more likely than nurses to discuss the potential role of placebo responses with patients (U = 140.5, p = 0.001, rrb = 0.52). While not statistically significant, trends suggested that physicians were more likely to provide written materials (M = 2.84, SD = 0.898) than nurses (M = 2.30, SD = 1.317; U = 199.5, p = 0.072) and document shared decision-making processes (M = 3.50, SD = 0.786) compared to nurses (M = 2.80, SD = 1.495; U = 203, p = 0.138). No significant differences were observed in involving patients in shared decision-making, discussing treatment benefits and risks, encouraging patient questions, or engaging family members in decision-making (Table 4).

Cultural competences of health professionals

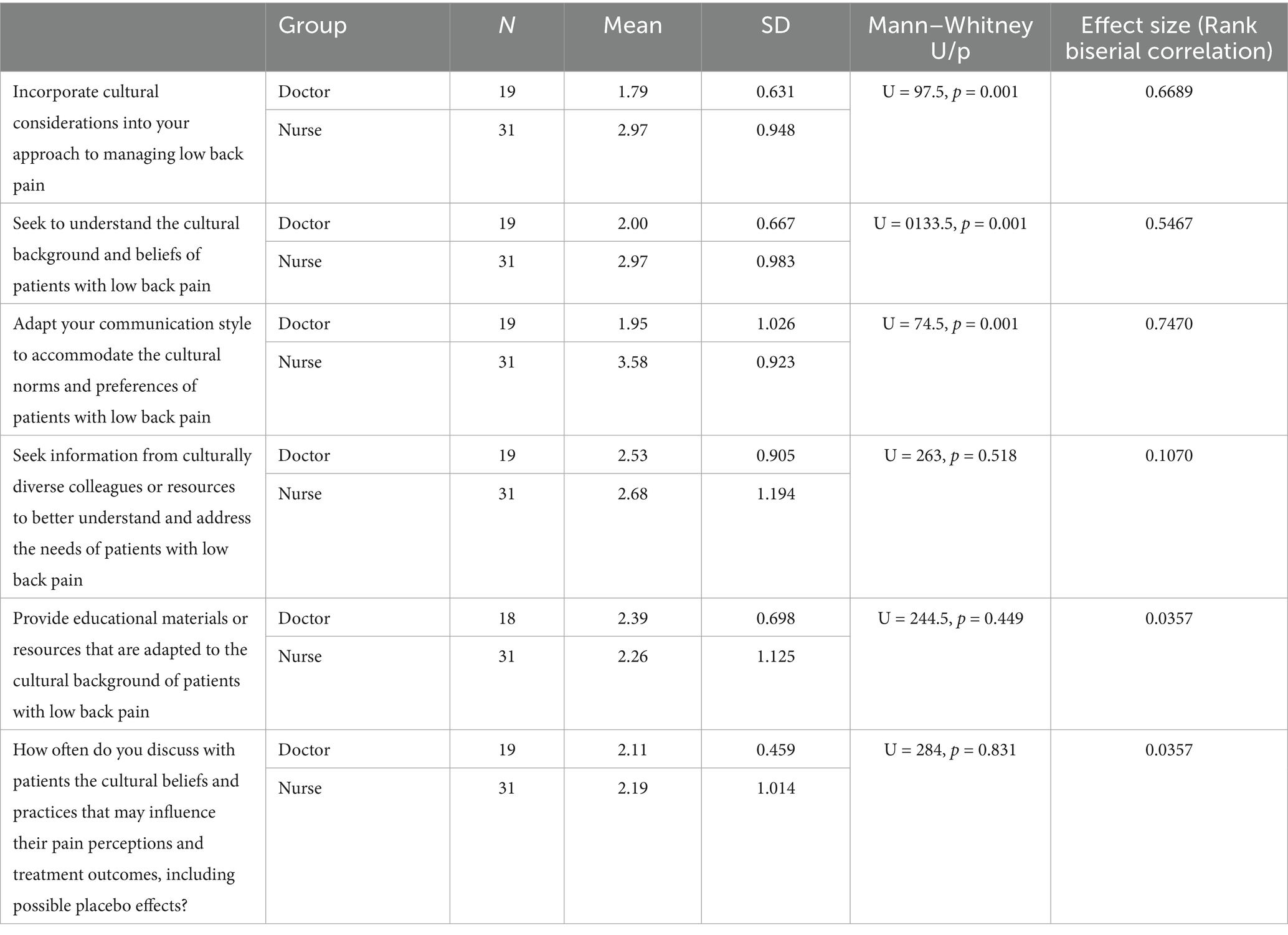

Nurses were significantly more likely than physicians to incorporate cultural considerations into their approach (U = 97.5, p = 0.001) and to seek an understanding of patients’ cultural backgrounds and beliefs (U = 133.5, p = 0.001). Nurses also adapted their communication styles to align with cultural norms and preferences more frequently than physicians (U = 74.5, p = 0.001), with the largest effect observed in this area (0.747). No significant differences were found in seeking culturally diverse resources (U = 263, p = 0.518), providing culturally adapted educational materials (U = 244.5, p = 0.449), or discussing cultural beliefs related to pain perception and treatment outcomes (U = 284, p = 0.831). However, mean differences suggested that nurses tended to seek culturally diverse resources (M = 2.68, SD = 1.194) more often than physicians (M = 2.53, SD = 0.905) and discuss cultural beliefs slightly more frequently (M = 2.19, SD = 1.014 vs. M = 2.11, SD = 0.459) (Table 5).

Discussion

This study examined the communication behaviors of healthcare professionals managing low back pain in Israel, with specific attention to empathy, patient engagement, shared decision-making, and cultural competence. The findings underscore the critical importance of interpersonal competencies in the delivery of high-quality pain management, particularly in multicultural contexts where patients may hold divergent expectations and cultural understandings of pain. These dimensions of communication are not merely ancillary; rather, they constitute essential components of therapeutic effectiveness, especially in chronic care settings.

Empathy emerged as a key area of difference between nurses and physicians. Across several domains of empathic communication—including the expression of emotional support, recognition of patient feelings, and the use of nonverbal cues—nurses consistently reported higher levels of engagement. This trend resonates with prior literature, which has consistently shown that the nursing role often involves more sustained and emotionally attuned interactions, allowing for the development of stronger relational bonds with patients (Molina-Mula and Gallo-Estrada, 2020; Carter and Chochinov, 2007). Nurses’ proximity to patients and their involvement in daily care routines may create more opportunities for empathetic exchange. In contrast, physicians, who typically bear the responsibility for diagnostic reasoning and therapeutic decision-making, often operate under greater time constraints and hierarchical expectations, which may limit the depth of emotional engagement (Drossman et al., 2021).

This divergence has important implications for training and workforce development. Empathy is well-documented to improve outcomes by enhancing patient satisfaction, fostering trust, reducing anxiety, and promoting adherence to treatment plans (Derksen et al., 2013; Nembhard et al., 2023). Therefore, the identified gap in empathic communication among physicians points to the need for targeted educational interventions. Training that cultivates reflective listening, emotional attunement, and the deliberate use of verbal and nonverbal cues could enhance empathic capacity, particularly for professionals operating in fast-paced or high-demand environments.

In addition to empathy, our findings suggest that nurses were more likely than physicians to employ proactive patient engagement strategies. These included behaviors such as encouraging patients to express concerns, offering reassurance, and building trust. Such strategies are especially important in the context of chronic pain, where patients often grapple with uncertainty, frustration, and fear. Psychological factors like catastrophizing, perceived helplessness, and low self-efficacy are known to amplify pain perception and complicate management (Kwame and Petrucka, 2021; Akyirem et al., 2022). Nurses’ emphasis on relational engagement can help to mitigate these psychosocial stressors, thus contributing to more effective and holistic care.

Notably, nurses were also more likely to engage in transparent communication, especially regarding uncertainty in treatment outcomes. This is a particularly valuable skill in chronic pain contexts, where therapeutic options are often limited, non-curative, or iterative. Transparent dialogue about these realities—far from undermining patient confidence—can actually enhance trust and support more realistic expectations (Simpkin and Armstrong, 2019). Conversely, physicians were more likely to discuss the placebo effect, which reflects an orientation toward biomedical explanations and evidence-based reasoning. While such communication is critical, it is insufficient on its own to support meaningful patient engagement in chronic care. This suggests that physicians may be adopting a more didactic, less collaborative approach to communication, potentially limiting the degree of shared understanding and partnership in care decisions.

The concept of Shared Decision-Making is central to patient-centered care and warrants further conceptual elaboration considering the present findings. SDM refers to a collaborative process through which clinicians and patients jointly deliberate on healthcare options, integrating the best available clinical evidence with the patient’s values, preferences, and life circumstances (Elwyn et al., 2012; Légaré and Thompson-Leduc, 2014). It differs fundamentally from informed consent, which primarily ensures legal disclosure, and from paternalistic care models, in which decisions are made unilaterally by clinicians (Kituuka et al., 2024). Rather, SDM involves a reciprocal exchange of information, discussion of risks and benefits, and mutual agreement on a course of action (Charles et al., 1997). In this context, SDM can be understood as both a clinical method and an ethical imperative, reinforcing respect for patient autonomy while optimizing clinical outcomes.

Despite its endorsement in international health policy, translating SDM into routine clinical practice remains a significant challenge. Research highlights a persistent implementation gap between the theoretical ideal of SDM and its consistent application in daily encounters (Joseph-Williams et al., 2017; Légaré et al., 2008; Härter et al., 2017). Barriers include time limitations, institutional constraints, lack of clinician training in communication and negotiation skills, and variability in patients’ health literacy (Légaré et al., 2008). Moreover, defining and measuring SDM scientifically continues to pose difficulties, as its success depends not only on outcomes but also on the relational and communicative processes through which those outcomes are reached. Recent developments, such as the OPTION scale and CollaboRATE tool, represent valuable advances in quantifying SDM behaviors, yet consensus regarding what constitutes “effective” SDM remains limited (Makoul and Clayman, 2006; Scholl et al., 2011). Addressing these conceptual and methodological challenges is essential for embedding SDM more fully into evidence-based practice.

The present findings reflect these challenges within the Israeli healthcare context. Although both nurses and physicians endorsed SDM principles, structural pressures—such as limited consultation time, hierarchical decision structures, and variations in patients’ health literacy—often constrained their practical implementation (Miron-Shatz et al., 2012). These contextual factors mirror international reports on the persistent gap between SDM policy ideals and clinical realities (Elwyn et al., 2012; Légaré and Thompson-Leduc, 2014; Joseph-Williams et al., 2021; Härter et al., 2017). Furthermore, the absence of standardized SDM assessment tools in Israel underscores the need for contextually adapted evaluation frameworks capable of capturing both procedural and relational dimensions of decision-making. Integrating such tools into clinical education and institutional policy could promote more consistent and measurable adoption of SDM practices (Muscat et al., 2021; Karnieli-Miller et al., 2017).

Shared decision-making represents another dimension where nurses and physicians diverged in both form and emphasis. Although overall levels of shared decision-making were similar, distinct patterns were evident. Physicians were more likely to provide written materials and document clinical decisions, reflecting a structured and formal approach to information sharing. This method ensures clarity and medico-legal accountability but may be insufficient for fostering deeper patient involvement. Nurses, by contrast, demonstrated greater engagement in the relational elements of shared decision-making, such as validating patient preferences, encouraging open dialogue, and promoting active participation in care planning. These complementary approaches highlight the need for integrating both procedural and relational components in shared decision-making processes (Franklin and Zhang, 2014; O'Donnell et al., 2023).

Interestingly, there were no significant differences between nurses and physicians in involving family members or in discussing treatment benefits and risks. This uniformity may point to broader systemic constraints, such as time pressures, high patient volumes, or gaps in communication training. In many clinical environments, professionals may lack the time, institutional support, or structured tools to facilitate comprehensive shared decision-making practices. Addressing these barriers requires system-level strategies, including the development of interdisciplinary curricula that build collaborative competencies across healthcare roles and encourage team-based approaches to patient communication (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al., 2021).

While the ideal of Shared Decision-Making envisions patients as active collaborators in treatment planning, not all individuals possess the medical knowledge or confidence required to engage equally in this process. The asymmetry of expertise between clinicians and patients often reinforces reliance on professional authority, particularly when treatment options involve complex technical details or risk–benefit uncertainties. Patients with limited health literacy may struggle to interpret clinical data, evaluate probabilities, or comprehend nuanced treatment tradeoffs, leading them to defer to clinician recommendations rather than actively articulating their preferences or concerns. Achieving genuine SDM therefore requires more than inviting participation; it demands structured communication approaches and educational support that empower patients to make informed contributions. Evidence indicates that decision aids, plain-language communication, and targeted health literacy interventions enhance patients’ understanding and engagement in the decision-making process (Coulter and Collins, 2011; Yu et al., 2025; Hersch et al., 2025).

Cultural competence was another salient theme in our findings, particularly in the context of Israel’s diverse population. Nurses demonstrated higher levels of cultural sensitivity, including the adaptation of communication styles and the exploration of culturally relevant beliefs and values. This reflects their traditional role as “cultural brokers,” who often mediate between institutional protocols and patients’ individual worldviews (Kaihlanen et al., 2019). In settings characterized by linguistic, ethnic, and religious diversity, such as Israel, this responsiveness is vital. Patients’ beliefs about pain, health, and authority can vary widely, and mismatches between providers’ assumptions and patients’ cultural frameworks can undermine therapeutic relationships and outcomes.

Conversely, the findings suggest that physicians may have less training or fewer opportunities to engage in culturally attuned communication. This may reflect traditional medical curricula that prioritize technical knowledge over socio-cultural awareness. Given the well-documented associations between cultural competence and improved diagnostic accuracy, treatment adherence, and patient satisfaction (Govere and Govere, 2016; De-María et al., 2024), this gap represents an important target for intervention. Training in cultural humility—not merely knowledge of cultural “facts”—should be embedded in continuing medical education and institutional policies. Such efforts can help ensure that physicians are better equipped to recognize and address the ways in which sociocultural factors shape patients’ experiences of illness, especially in the context of chronic pain (Stubbe, 2020).

These findings can be further interpreted within the context of the study’s theoretical framework. According to Social Cognitive Theory, the observed differences in empathy and communication may reflect variations in self-efficacy—that is, healthcare professionals’ confidence in their ability to engage patients effectively and respond to their needs. Moreover, the interaction between provider behaviors and patient responses exemplifies the principle of reciprocal determinism, whereby social and environmental feedback continuously shape communicative behaviors. From the standpoint of the Campinha-Bacote model of Cultural Competence, the positive association between cultural competence and patient reassurance highlights the role of cultural awareness and cultural encounters as core mechanisms facilitating adaptive communication. Viewed integratively, these results suggest that effective clinical communication is a socially constructed and continually evolving process shaped by individual, professional, and cultural determinants (Bandura, 1986; Campinha-Bacote, 2002).

Implications for practice and policy

The current research highlights important implications for both clinical practice and healthcare policy, emphasizing the need for a strategic, role-specific approach to enhancing communication within healthcare settings.

First, communication training should be tailored to the specific roles of healthcare professionals. Nurses, who often engage more intimately with patients, would benefit from focused training in emotional support, active listening, and nonverbal communication. Physicians, on the other hand, would benefit from training that emphasizes shared decision-making, patient engagement, and culturally competent communication, given their diagnostic focus and time constraints. Such training should occur at multiple levels, including formal integration into health professions curricula and continuing professional development programs for practicing clinicians, as recent research underscores the importance of embedding communication and cultural competence education within structured curricular frameworks (Karakolias et al., 2025; Lokmic-Tomkins et al., 2024). Role-specific training would address the distinct communication needs of each profession, leading to more effective patient–provider interactions and improved outcomes (Hatfield et al., 2020; Iversen et al., 2021).

Second, interprofessional education is essential to fostering collaboration across healthcare teams (Mohammed et al., 2021). By bringing together nurses, physicians, and other healthcare providers, interprofessional education can standardize communication strategies and promote team-based care. This is particularly crucial in chronic pain management, where communication is central to patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and overall care efficacy. Integrating interprofessional education into training ensures that healthcare professionals share a unified understanding of best communication practices, ultimately improving both care quality and patient outcomes (Zenani et al., 2023; Zechariah et al., 2019).

Third, healthcare institutions must develop systems for assessing and incentivizing communication competencies. Incorporating communication skills into performance evaluations, patient feedback mechanisms, and continuing education programs will reinforce the importance of empathy, engagement, and cultural competence in clinical practice. Regular evaluations and tailored interventions will foster continuous professional development and enhance the quality of care delivered across healthcare settings (Endalamaw et al., 2024).

From a policy standpoint, embedding communication and cultural competence into national guidelines for chronic pain and low back pain management is essential for standardizing care (Kern, 2023; Rogger et al., 2023). This will reduce variability in care quality and ensure that all patients receive compassionate, high-quality care (Saha et al., 2008; Bradshaw et al., 2022). Furthermore, incorporating patient-reported outcomes that assess communication experiences will provide valuable feedback, facilitating ongoing improvements in patient-provider interactions and care quality (Van Der Wees et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019).

Limitations and future research

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting these findings. First, the study employed a convenience sample with a relatively small size, drawn from specific clinical departments within a single medical center. This approach may introduce selection bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings. In addition, the majority of participants were drawn from the Emergency Medicine Department and the Orthopedics Department, which may reflect communication dynamics specific to acute and surgical care contexts and therefore limit the transferability of findings to other clinical environments, such as rehabilitation or primary care. Additionally, the use of self-reported data introduces potential biases, particularly social desirability bias, which may influence responses in areas such as empathy and cultural sensitivity. To address these concerns, future studies could incorporate observational methodologies or utilize patient-reported assessments to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of communication quality. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the current study does not allow for an examination of how communication practices evolve over time. Longitudinal research is needed to investigate how changes in communication strategies relate to clinical outcomes, such as treatment adherence and pain management effectiveness, in patients with low back pain. Expanding the scope of future research to include a more diverse sample and employing mixed-methods approaches would also strengthen the generalizability and depth of the findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of Ziv Medical Center, Safed, Northern Israel (Approval Number: ZIV-0072-24; Date: November 28, 2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SN: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology. AG: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study is financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project № BG-RRP-2.004-0009-C02.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used generative AI (ChatGPT, OpenAI) to assist with English language editing and refinement of the manuscript text. All content was reviewed and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy and integrity.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akyirem, S., Salifu, Y., Bayuo, J., Duodu, P. A., Bossman, I. F., and Abboah-Offei, M. (2022). An integrative review of the use of the concept of reassurance in clinical practice. Nurs. Open 9, 1515–1535. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1102,

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 31, 143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660

Bishop, A., Foster, N. E., Thomas, E., and Hay, E. M. (2008). How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain 135, 187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.11.010,

Bogaert, L., Brumagne, S., Léonard, C., Lauwers, A., and Peters, S. (2024). Physiotherapist- and patient-reported barriers to guideline implementation of active physiotherapeutic management of low back pain: a theory-informed qualitative study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 73:103129. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2024.103129,

Bradshaw, J., Siddiqui, N., Greenfield, D., and Sharma, A. (2022). Kindness, listening, and connection: patient and clinician key requirements for emotional support in chronic and complex care. J. Patient Exp. 9:23743735221092627. doi: 10.1177/23743735221092627,

Buskila, D., Abramov, G., Biton, A., and Neumann, L. (2000). The prevalence of pain complaints in a general population in Israel and its implications for utilization of health services. J. Rheumatol. 27, 1521–1525.

Campinha-Bacote, J. (2002). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 13, 181–201. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003003

Carter, A. J., and Chochinov, A. H. (2007). A systematic review of the impact of nurse practitioners on cost, quality of care, satisfaction and wait times in the emergency department. CJEM 9, 286–295. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500015189,

Cavaco, A. M., Quitério, C. F., Félix, I. B., and Guerreiro, M. P. (2023). “Communication and person-centred behaviour change” in A practical guide on behaviour change support for self-managing chronic disease. eds. M. P. Guerreiro, I. Brito Félix, and M. Moreira Marques (Cham: Springer), 57–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-20010-6_5

Charles, C., Gafni, A., and Whelan, T. (1997). Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? Soc. Sci. Med. 44, 681–692. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00221-3

Coulter, A, and Collins, A. Making shared decision-making a reality: No decision about me, without me. London: The King’s Fund; (2011). Available online at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs_decisionmaking.htm (Accessed July 20, 2025).

Daher, A., and Dar, G. (2025). Physician referrals of patients with neck and low back pain for physical therapy in outpatient clinics: a cross-sectional study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13584-025-00683-7,

Dang, B. N., Westbrook, R. A., Njue, S. M., and Giordano, T. P. (2017). Building trust and rapport early in the new doctor–patient relationship: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 17:32. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0868-5,

De-María, B., Topa, G., and López-González, M. A. (2024). Cultural competence interventions in European healthcare: a scoping review. Healthcare (Basel) 12:1040. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12101040,

Derksen, F., Bensing, J., and Lagro-Janssen, A. (2013). Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 63, e76–e84. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X660814,

Drossman, D. A., Chang, L., Deutsch, J. K., Ford, A. C., Halpert, A., Kroenke, K., et al. (2021). A review of the evidence and recommendations on communication skills and the patient–provider relationship: a Rome foundation working team report. Gastroenterology 161, 1670–88.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.037,

Elwyn, G., Frosch, D. L., Thomson, R., Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Kinnersley, P., et al. (2012). Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27, 1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6,

Endalamaw, A., Khatri, R. B., Mengistu, T. S., Erku, D., Wolka, E., Zewdie, A., et al. (2024). A scoping review of continuous quality improvement in healthcare system: conceptualization, models and tools, barriers and facilitators, and impact. BMC Health Serv. Res. 24:487. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-10828-0,

Epstein, R. M., and Street, R. L. Jr. (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann. Fam. Med. 9, 100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239,

Fatoye, F., Gebrye, T., and Odeyemi, I. (2019). Real-world incidence and prevalence of low back pain using routinely collected data. Rheumatol. Int. 39, 619–626. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04273-0,

Ferreira, D. C., Vieira, I., Pedro, M. I., Caldas, P., and Varela, M. (2023). Patient satisfaction with healthcare services and the techniques used for its assessment: a systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 11:639. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11050639,

Franklin, A., and Zhang, J. (2014). “Cognitive considerations for health information technology” in Clinical decision support. ed. R. A. Greenes. 2nd ed (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 619–640.

Fu, Y., McNichol, E., Marczewski, K., and Closs, S. J. (2015). Patient–professional partnerships and chronic back pain self-management: a qualitative systematic review and synthesis. Health Soc. Care Community 23, 225–236. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12223

GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators (2023). Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 5, e316–e329. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00098-X,

Ge, L., Pereira, M. J., Yap, C. W., and Heng, B. H. (2022). Chronic low back pain and its impact on physical function, mental health, and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study in Singapore. Sci. Rep. 12:20040. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24703-7,

Govere, L., and Govere, E. M. (2016). How effective is cultural competence training of healthcare providers on improving patient satisfaction of minority groups? A systematic review of literature. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 13, 402–410. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12176,

Greene, S. M., Tuzzio, L., and Cherkin, D. (2012). A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm. J. 16, 49–53. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-025,

Guidi, C., and Traversa, C. (2021). Empathy in patient care: from 'clinical empathy' to 'empathic concern'. Med. Health Care Philos. 24, 573–585. doi: 10.1007/s11019-021-10033-4,

Haidet, P., Dains, J. E., Paterniti, D. A., Hechtel, L., Chang, T., Tseng, E., et al. (2002). Medical student attitudes toward the doctor–patient relationship. Med. Educ. 36, 568–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01233.x,

Handtke, O., Schilgen, B., and Mösko, M. (2019). Culturally competent healthcare - a scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLoS One 14:e0219971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219971,

Hannawa, A. F., Wu, A. W., Kolyada, A., Potemkina, A., and Donaldson, L. J. (2022). The aspects of healthcare quality that are important to health professionals and patients: a qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 1561–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.10.016,

Härter, M., Moumjid, N., Cornuz, J., Elwyn, G., and van der Weijden, T. (2017). Shared decision making in 2017: international accomplishments in policy, research and implementation. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 123-124, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.024,

Hatfield, T. G., Withers, T. M., and Greaves, C. J. (2020). Systematic review of the effect of training interventions on the skills of health professionals in promoting health behaviour, with meta-analysis of subsequent effects on patient health behaviours. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20:593. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05420-1,

Haverfield, M. C., Giannitrapani, K., Timko, C., and Lorenz, K. (2018). Patient-centered pain management communication from the patient perspective. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 33, 1374–1380. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4490-y,

Hersch, J., O’Hara, L., Juraskova, I., Laidsaar-Powell, R., Bartley, N., Gillies, K., et al. (2025). Interventions to support patient decision making about taking part in health research: a systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 141:109339. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2025.109339

Islam, K. F., Awal, A., Mazumder, H., Munni, U. R., Majumder, K., Afroz, K., et al. (2023). Social cognitive theory-based health promotion in primary care practice: a scoping review. Heliyon 9:e14889. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14889,

Iversen, E. D., Wolderslund, M., Kofoed, P. E., Gulbrandsen, P., Poulsen, H., Cold, S., et al. (2021). Communication skills training: a means to promote time-efficient patient-centered communication in clinical practice. J. Patient Cent. Res. Rev. 8, 307–314. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1782,

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., and Bainbridge, R. (2018). Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18:232. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5,

Joseph-Williams, N., Abhyankar, P., Boland, L., Bravo, P., Brenner, A. T., Brodney, S., et al. (2021). What works in implementing patient decision aids in routine clinical settings? A rapid realist review and update from the international patient decision aid standards collaboration. Med. Decis. Mak. 41, 907–937. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20978208,

Joseph-Williams, N., Lloyd, A., Edwards, A., Stobbart, L., Tomson, D., Macphail, S., et al. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 357:j1744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1744,

Kaihlanen, A. M., Hietapakka, L., and Heponiemi, T. (2019). Increasing cultural awareness: qualitative study of nurses' perceptions about cultural competence training. BMC Nurs. 18:38. doi: 10.1186/s12912-019-0363-x,

Karakolias, S., Tagarakis, G., and Polyzos, N. (2025). Communication skills as a bridge between medical and public health education: the case of Greek medical students. Front. Public Health 13:1709045. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1709045,

Karnieli-Miller, O, Miron-Shatz, T, Siegal, G, and Zisman-Ilani, Y. On the verge of implementing shared decision making in Israel: an overview and future directions. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes.. 2017;123–124:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.007.

Kern, K. U. (2023). Low back pain management in routine clinical practice: what is important for the individual patient? Pain Manag. 13, 243–252. doi: 10.2217/pmt-2022-0096,

Kituuka, O., Mwaka, E. S., Munabi, I. G., Galukande, M., and Sewankambo, N. (2024). A qualitative study on informed consent decision-making at two tertiary hospitals in Uganda: experiences of patients undergoing emergency surgery and their next of kin. SAGE Open Med. 12:20503121241259931. doi: 10.1177/20503121241259931,

Kovačević, I., Pavić, J., Filipović, B., Ozimec Vulinec, Š., Ilić, B., and Petek, D. (2024). Integrated approach to chronic pain—the role of psychosocial factors and multidisciplinary treatment: a narrative review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 21:1135. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21091135,

Krist, A. H., Tong, S. T., Aycock, R. A., and Longo, D. R. (2017). Engaging patients in decision-making and behavior change to promote prevention. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 240, 284–302. doi: 10.3233/ISU-170826,

Kwame, A., and Petrucka, P. M. (2021). A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs. 20:158. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2,

Légaré, F., Ratté, S., Gravel, K., and Graham, I. D. (2008). Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ. Couns. 73, 526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018,

Légaré, F., and Thompson-Leduc, P. (2014). Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ. Couns. 96, 281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.014,

Levinson, W., Lesser, C. S., and Epstein, R. M. (2010). Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. (Millwood) 29, 1310–1318. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450,

Lokmic-Tomkins, Z., Barbour, L., LeClair, J., Luebke, J., McGuinness, S. L., Limaye, V. S., et al. (2024). Integrating planetary health education into tertiary curricula: a practical toolbox for implementation. Front. Med. 11:1437632. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1437632,

Lozano, P. M., Allen, C. L., Barnes, K. A., Peck, M., and Mogk, J. M. (2025). Persistent pain, long-term opioids, and restoring trust in the patient–clinician relationship. J. Pain 27:104694. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2024.104694,

Makoul, G., and Clayman, M. L. (2006). An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 60, 301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010,

Manjarres-Posada, N. I., Onofre-Rodríguez, D. J., and Benavides-Torres, R. A. (2020). Social cognitive theory and health care: analysis and evaluation. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 8, 132–126. doi: 10.11114/ijsss.v8i4.4870,

Mead, N., and Bower, P. (2000). Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00098-8,

Miron-Shatz, T., Golan, O., Brezis, M., Siegal, G., and Doniger, G. M. (2012). Shared decision-making in Israel: status, barriers, and recommendations. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 1:5. doi: 10.1186/2045-4015-1-5,

Mohammed, C. A., Anand, R., and Saleena Ummer, V. (2021). Interprofessional education (IPE): a framework for introducing teamwork and collaboration in health professions curriculum. Med. J. Armed Forces India 77, S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.01.012

Molina-Mula, J., and Gallo-Estrada, J. (2020). Impact of nurse-patient relationship on quality of care and patient autonomy in decision-making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:835. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030835,

Muscat, D. M., Smith, J., Mac, O., Cadet, T., Giguere, A., Housten, A. J., et al. (2021). Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids: an update from the international patient decision aid standards. Med. Decis. Mak. 41, 848–869. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211011101,

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and MedicineHealth and Medicine DivisionBoard on Health Care ServicesCommittee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care. Implementing high-quality primary care: Rebuilding the foundation of health care. SK Robinson, M Meisnere, RL PhillipsJr, and L McCauley, editors. National Academies Press; (2021). Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK571814/ (Accessed July 24, 2025).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Evidence review for communication between healthcare professionals and people with chronic pain (chronic primary pain and chronic secondary pain): chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain (evidence review B, NICE guideline no. 193). London (UK): National Guideline Centre; (2021). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193 (Accessed July 26, 2025).

Nembhard, I. M., David, G., Ezzeddine, I., Betts, D., and Radin, J. (2023). A systematic review of research on empathy in health care. Health Serv. Res. 58, 250–263. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.14016,

O'Donnell, D., Davies, C., Christophers, L., Ní Shé, É., Donnelly, S., and Kroll, T. (2023). An examination of relational dynamics of power in the context of supported (assisted) decision-making with older people and those with disabilities in an acute healthcare setting. Health Expect. 26, 789–798. doi: 10.1111/hex.13750

Reith-Hall, E., and Montgomery, P. (2023). Communication skills training for improving the communicative abilities of student social workers. Campbell Syst. Rev. 19:e1309. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1309,

Rogger, R., Bello, C., Romero, C. S., Urman, R. D., Luedi, M. M., and Filipovic, M. G. (2023). Cultural framing and the impact on acute pain and pain services. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 27, 429–436. doi: 10.1007/s11916-023-01125-2,

Saha, S., Beach, M. C., and Cooper, L. A. (2008). Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 100, 1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4,

Scholl, I., Koelewijn-van Loon, M., Sepucha, K., Elwyn, G., Légaré, F., Härter, M., et al. (2011). Measurement of shared decision making—a review of instruments. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 105, 313–324. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2011.04.012,

Sharkiya, S. H. (2023). Quality communication can improve patient-centred health outcomes among older patients: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23:886. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09869-8,

Sharma, N. P., and Gupta, V. Therapeutic communication. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567775/ (accessed Jul 1, 2025).

Sharon, H., Greener, H., Hochberg, U., and Brill, S. (2022). The prevalence of chronic pain in the adult population in Israel: an internet-based survey. Pain Res. Manag. 2022:3903720. doi: 10.1155/2022/3903720,

Simpkin, A. L., and Armstrong, K. A. (2019). Communicating uncertainty: a narrative review and framework for future research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 34, 2586–2591. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04860-8,

Stacey, D., Légaré, F., Lewis, K., Barry, M. J., Bennett, C. L., Eden, K. B., et al. (2017). Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5,

Stubbe, D. E. (2020). Practicing cultural competence and cultural humility in the Care of Diverse Patients. Focus (Am. Psychiatr. Publ.) 18, 49–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20190041,

Tian, C. Y., Wong, E. L.-Y., Qiu, H., Zhao, S., Wang, K., Cheung, A. W.-L., et al. (2024). Patient experience and satisfaction with shared decision-making: a cross-sectional study among outpatients. Patient Educ. Couns. 129:108410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2024.108410,

Tikkanen, V., and Sundberg, K. (2024). Care relationship and interaction between patients and ambulance clinicians: a qualitative meta-synthesis from a person-centred perspective. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 38, 24–34. doi: 10.1111/scs.13225,

Van Der Wees, P. J., Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden, M. W., Ayanian, J. Z., Black, N., Westert, G. P., and Schneider, E. C. (2014). Integrating the use of patient-reported outcomes for both clinical practice and performance measurement: views of experts from 3 countries. Milbank Q. 92, 754–775. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12091

Varela, A. J., Gallamore, M. J., Hansen, N. R., and Martin, D. C. (2025). Patient empowerment: a critical evaluation and prescription for a foundational definition. Front. Psychol. 15:1473345. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1473345,

Waddell, A., Lennox, A., Spassova, G., and Bragge, P. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in hospitals from policy to practice: a systematic review. Implement. Sci. 16:74. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01142-y

Watson, J. (2008). Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Rev. Edn. Boulder (CO): University Press of Colorado.

World Health Organization. (2001). People-centred health care: A policy framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345077 (Accessed July 25, 2025).

Wu, A., March, L., Zheng, X., Huang, J., Wang, X., Zhao, J., et al. (2020). Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann. Transl. Med. 8:299. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.175,

Yu, S. F., Kuo, P. J., Lin, H. C., and Yu, H. T. (2025). Defining the strategies to advance health-literacy-friendly patient decision aids based on the ICA-NRM approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 25:1218. doi: 10.1186/s12913-025-13439-5,

Zechariah, S., Ansa, B. E., Johnson, S. W., Gates, A. M., and Leo, G. (2019). Interprofessional education and collaboration in healthcare: an exploratory study of the perspectives of medical students in the United States. Healthcare (Basel) 7:117. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7040117,

Zenani, N. E., Sehularo, L. A., Gause, G., and Chukwuere, P. C. (2023). The contribution of interprofessional education in developing competent undergraduate nursing students: integrative literature review. BMC Nurs. 22:315. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01482-8,

Keywords: chronic pain, back pain, health communication, nurses, physicians, cultural competence, empathy, cross-sectional studies

Citation: Nikolova S and Gotani A (2025) Exploring empathy, communication, and cultural competence in low back pain care: a comparative cross-sectional study of nurses and physicians in Israel. Front. Commun. 10:1674019. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1674019

Edited by:

Victoria Team, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Stefanos Karakolias, Democritus University of Thrace, GreecePavlo Sodomora, Danylo Halytsky Lviv National Medical University, Ukraine

Copyright © 2025 Nikolova and Gotani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silviya Nikolova, c2lsdml5YS5wLm5pa29sb3ZhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Silviya Nikolova

Silviya Nikolova Aiham Gotani

Aiham Gotani