- 1Institute for Media Research, Chemnitz University of Technology, Chemnitz, Germany

- 2Department of Media and Communication, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich, Germany

Introduction: In recent years, Germany has experienced a steady rise in international student enrollment at its higher education institutions. While universities publicly commit to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) principles, many fall short in translating these commitments into concrete practices. The lack of initiatives fostering meaningful cross-cultural engagement frequently contributes to integration challenges and experiences of othering. These experiences cause international students to face greater adjustment challenges than their local peers, often resulting in increased feelings of loneliness, depression, and isolation. Limited social interaction and othering can further create barriers in accessing health information and services. In this challenging time, however, it is particularly important to have access to health information and services that support and advise international students in coping with emotional and social difficulties. Drawing on social capital theory, this study examines the interrelationship between international students’ experiences of othering, their ties within their country of origin and Germany—reflected in their acculturation trajectories—and access to health information.

Methods: To examine these interrelations and the role of othering in these processes, we conducted interviews with 15 international students in Germany.

Results: The findings indicate that acculturation trajectories are reflected in participants’ health information repertoires, particularly regarding access to trusted individuals as health information sources. Participants undergoing integration typically reported utilizing a broader set of sources from multiple cultural contexts, whereas those experiencing separation or assimilation tended to rely on sources from only one context. Experiences of social othering—particularly within university settings—shaped the international students’ acculturation trajectories, especially among those experiencing separation. Linguistic exclusion and discriminatory behaviors by health professionals prompted many participants to avoid medical consultations and instead rely more on online sources.

Discussion: These findings underscore the need for cultural sensitivity training among health professionals and institutional efforts to counteract othering on campus through comprehensive integration strategies and cross-cultural engagement initiatives.

1 Introduction

Universities increasingly actively advertise abroad to recruit international students. These efforts have been successful, as a growing number of students worldwide seek educational opportunities abroad (Forbes-Mewett and Sawyer, 2016). Germany has experienced a steady rise in international student enrollment in recent years. In 2024, a record high of over 90,000 new students from countries outside Germany registered at German universities, raising the total number of international students to more than 400,000 (DAAD, 2024b; Mediendienst Integration, 2025). Approximately one-third of these students choose to remain in Germany after completing their studies (Destatis, 2022). The term international students refers to individuals who received their prior education in another country, have crossed national borders for education, and are currently enrolled in an institution outside their country of origin (Ma et al., 2020; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, n.d.). While many international students migrate solely for educational purposes and plan to return to their country of origin or relocate elsewhere upon completing their studies, this study focuses on international students who intend to remain in Germany after graduation.1

With the growing number of international students enrolling at German universities, many institutions have adopted formalized collective principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and publicly communicate their commitment to these values (see, e.g., Heidelberg University, n.d.; University of Freiburg, n.d.; University of Stuttgart, n.d.). These principles are intended to counteract the marginalization and exclusion of minority groups within the context of higher education and to promote more inclusive campus environments (Wolbring and Lillywhite, 2021). However, not all universities can fully uphold these principles. International students increasingly report a lack of intercultural awareness and sensitivity on campus, describing the implementation of DEI principles more as superficial multiculturalism than genuine inclusion (Tavares, 2021). Limited opportunities for meaningful interaction with local peers and experiences of exclusion may negatively affect international students’ acculturation trajectories and overall well-being.

International students frequently face a range of (acculturation) challenges, including limited communication with family and friends in their countries of origin, homesickness, language barriers, and experiences of discrimination (Ambrósio et al., 2017; Carter et al., 2017; Forbes-Mewett and Sawyer, 2016; Gautam et al., 2016; Khoshlessan and Das, 2017; Newton et al., 2021; Reilly, 2013; Udah, 2021; Udah and Francis, 2022; Yoon and Kim, 2014). Compared to domestic students, they report lower life satisfaction, less social support, and greater difficulties with adjustment (Russell et al., 2009; Skromanis et al., 2018). Acculturation challenges stemming from the exclusionary and/or discriminatory behaviors of the broader society of the country of residence are referred to as othering. Othering can affect minority and less privileged groups not only in everyday social interactions but also by creating barriers to accessing health information—manifesting through linguistic exclusion or discriminatory treatment within healthcare services (e.g., Kearney et al., 2005; Newton et al., 2021).

To date, there is a lack of studies examining the role of othering—in the form of social exclusion and within the context of health information and services access—on the acculturation trajectories and health information repertoires of international students. Yet such research can yield valuable recommendations for universities, international offices, health information and service providers, local peers, and society at large to improve the situation of international students. Therefore, this study addresses the question of the role of othering in acculturation trajectories and access to health information among international students.

2 Acculturation trajectories of international students

Migration inevitably brings individuals into contact with members of other (cultural) groups—most often those belonging to the country of residence’s broader society. Through sustained direct contact, individuals of one or both cultures often experience shifts in their beliefs, values, and behaviors—a process that is referred to as acculturation (Fox et al., 2017b; Ozer, 2013; Redfield et al., 1936). Such changes are particularly pronounced among individuals from minority cultural backgrounds as they adapt to a new sociocultural environment (Wang and Yu, 2015). On a personal level, acculturation may be reflected in changes in language use, social networks, eating habits, and participation in popular culture (Birman and Zabrodskaja, 2024; Fox et al., 2017b; Wang and Yu, 2015). Because acculturation is a dynamic and not always a fully intentional or controllable process (Fox et al., 2017a), researchers increasingly refer to acculturation trajectories (e.g., Cobb et al., 2021; Park, 2022) instead of acculturation strategies, originally coined by Berry (1980).

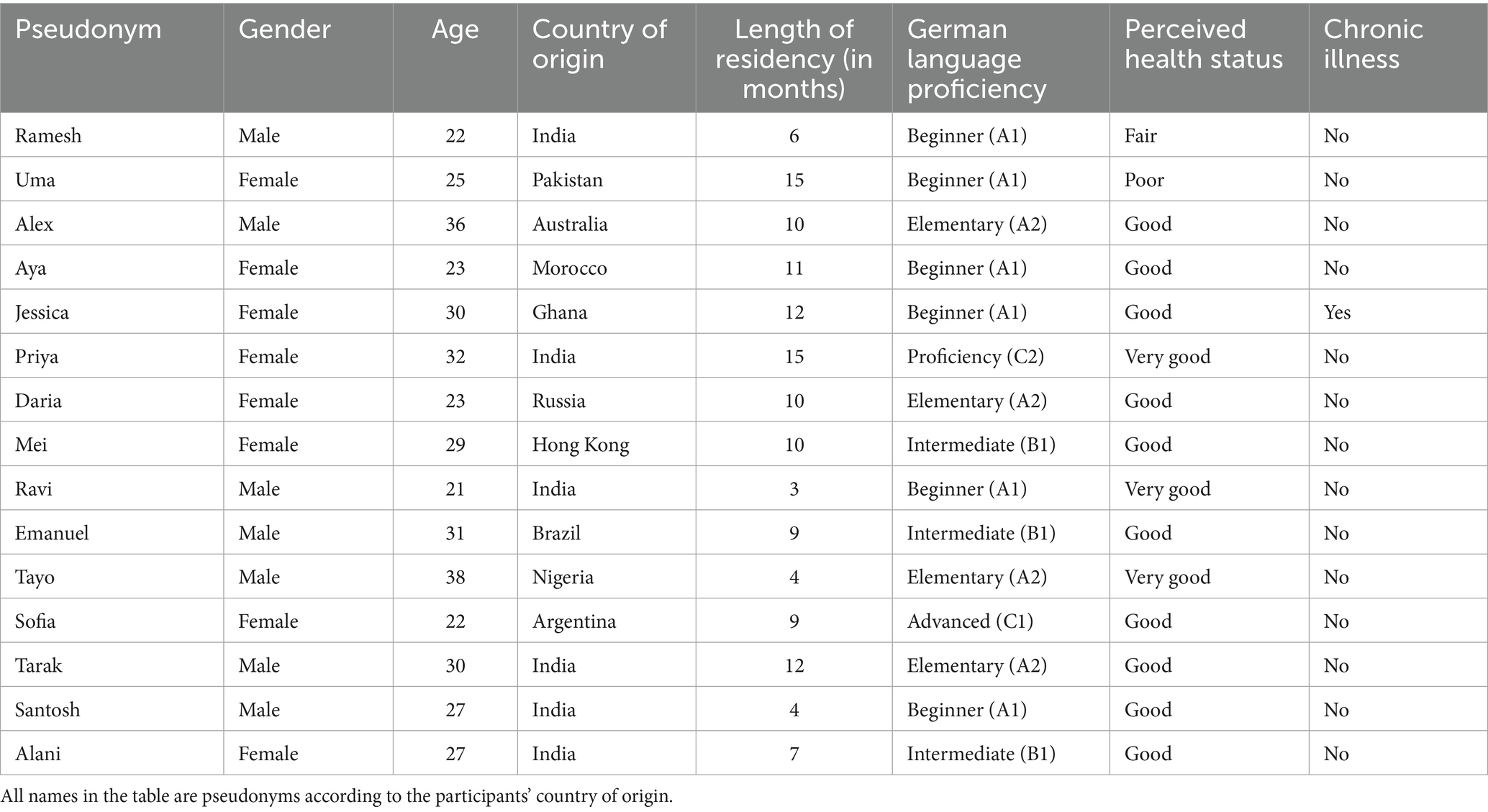

Berry (1980, 2022) conceptualizes acculturation as the different ways individuals adapt to new social and cultural contexts, proposing a bi-dimensional model grounded in two central dimensions: (1) orientation toward the original culture and (2) orientation toward the culture of the country of residences’ larger society (Andrushko and Lanza, 2024; Fox et al., 2017a; Nauck, 2008). Based on this model, four distinct acculturation trajectories emerge (see Figure 1): (1) Integration, where individuals maintain their heritage culture while actively participating in the broader society’s culture; (2) Assimilation, which involves engagement with the culture and people of the country of residence accompanied by the relinguishment of one’s original cultural identity; (3) Separation, where individuals preserve their heritage culture while having limited engagement with the larger society of the country of residence; and (4) Marginalization, characterized by a lack of connection to both the heritage and country of residence’s cultures and people (Andrushko and Lanza, 2024; Berry, 1980; Berry, 2022; Zhuk et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Model of acculturation. Own presentation based on Berry (1980, 2022) (see also, e.g., Kiylioglu and Wimmer, 2015).

The original model of Berry (1980) conceptualized acculturation predominantly from the perspective of migrants, taking little account of its reciprocal and dynamic nature. It implies that acculturation trajectories are shaped primarily by individual decisions, behaviors, and preferences of migrants, with limited attention to the structural conditions in the country of residence and its broader society (Zick, 2010). While this study similarly focuses on individual experiences from the migrant perspective, it also uncovers and critically examines the larger society’s societal behaviors, as well as structural conditions and challenges in the country of residence.

Berry’s framework is the most widely recognized model in cross-cultural psychology (Schwartz et al., 2020) and has also been applied in research on the acculturation of international students (e.g., Cao et al., 2021; Li et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2020; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Shim et al., 2014; Smith and Khawaja, 2011; Yan and FitzPatrick, 2016). However, previous studies have predominantly focused on specific subgroups of international students, particularly those from Asian countries (e.g., Cogan et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2020; Shim et al., 2014)—more specifically, on students from China (e.g., Bertram et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2021; Li et al., 2017). This is, however, understandable, as in many countries the largest proportion of international students originates from Asia, particularly from India and China (e.g., Australian Government, 2025; Deutsches Studierendenwerk, 2025; Institute of International Education, 2025). Research on the acculturation trajectories of international students in Germany remains limited (e.g., Shim et al., 2014).2 Moreover, most studies focus on international students’ experiences of acculturative stress rather than their specific acculturation trajectories (e.g., Bertram et al., 2014; Li et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2020; Yan, 2020; Zhang et al., 2010).

Research specifically examining international students’ acculturation trajectories has yielded divergent findings: While some studies suggest that most international students experience integration, with separation, marginalization, and assimilation being less common (e.g., Cao et al., 2021; Sullivan and Kashubeck-West, 2015), others report that separation, marginalization, and assimilation are more prevalent than integration (e.g., Shim et al., 2014). As all of the studies employed quantitative surveys and included international students from Asia either entirely or to a large extent, methodological biases do not appear to account for the divergent findings; rather, these are more plausibly attributable to differences in country contexts, given that the studies were conducted in the USA, Germany, and Belgium. The divergent findings regarding international students’ acculturation trajectories indicate that these are highly individualized processes, shaped by both personal characteristics and contextual conditions. To identify the specific acculturation trajectories of international students from a broader range of origins who are enrolled at German universities and to examine how acculturation unfolds in their social and cultural behavior, we first ask:

RQ1: In which acculturation trajectories do international students find themselves?

3 Othering in the context of acculturation

Beginning a degree program can be challenging for students in the initial stages of their university experience. These challenges are often amplified for international students, who must adapt to an unfamiliar socio-cultural environment in a foreign country. In addition to the common concerns university students face, international students may encounter difficulties that are less prevalent among their domestic peers and are likely to experience acculturative stress (Cogan et al., 2023; Kristiana et al., 2022; Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Lu et al., 2014; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Tang et al., 2012). These challenges can include language barriers, navigating unfamiliar educational systems, adapting to new cultural norms, and experiencing discrimination (Cao et al., 2021; Cogan et al., 2023; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Shim et al., 2014; Smith and Khawaja, 2011; Wong et al., 2014). Lacking familiarity with the academic system, cultural norms, and language makes international students more vulnerable to academic challenges and social exclusion (Laufer and Gorup, 2019). These challenges can serve as significant acculturative stressors, hindering international students from establishing relationships with members of the larger society (Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Shim et al., 2014), particularly in contexts such as Germany, where widely spoken global languages like English are not as commonly used in everyday life—as opposed to countries like the United States—and where students from collectivist cultures may find it difficult to adjust to the more individualistic cultural orientation of the broader society (Liu and Qian, 2023; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020).

Non-European students living in European countries of residence experience more difficulties making friends and are more likely to report perceived discrimination and forms of othering compared to both domestic students and European international students (Lee and Rice, 2007; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007; Shim et al., 2014). Such experiences contribute to heightened feelings of loneliness, isolation, and homesickness (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007; Shim et al., 2014). In addition, international students frequently report lower levels of perceived social support than their domestic peers (Khawaja and Dempsey, 2008; Shim et al., 2014). These emotional and social challenges can adversely affect international students’ acculturation trajectories and psychological well-being (Bertram et al., 2014; Cogan et al., 2023; Liu and Qian, 2023; Naylor, 2022; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Tavares, 2021; Shim et al., 2014).

Many acculturation challenges international students face stem from the broader society’s exclusionary or discriminatory behaviors—phenomena often conceptualized as forms of othering (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Udah and Singh, 2019). Othering is defined as a “process which serves to mark and name those thought to be different from oneself” (Weis, 1995, p. 17), relating to behaviors and interactions performed by majority groups and/or privileged groups towards minority groups and/or less privileged groups (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Liu and Qian, 2023; Udah and Singh, 2019). From the migrants’ perspective, othering refers to experiencing negative assumptions due to their status as a foreigner (Laufer and Gorup, 2019). Individuals who do not fit the country of residence’s society’s norms are designated as ‘the Others’. Differences are marked by biased, reductionist, or discriminatory behaviors of the majority or privileged group (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Liu and Qian, 2023; Tavares, 2021; Udah and Singh, 2019; Yao, 2018). In the context of international students, othering relates to power imbalances between minority student groups and the more powerful and privileged groups, such as professors, majority student groups, or any other more powerful or privileged individuals or groups of the broader society, and to perceptions of being marked as different by those in positions of power or privilege (Bilecen, 2013; Laufer and Gorup, 2019). When examining acculturation, we particularly focus on social othering, which—in the context of international students—is defined as “an individual’s experience of exclusion from participation in formal and informal social interactions at the university or within the [broader] society” (Laufer and Gorup, 2019, p. 176).

Prior research on othering behaviors directed at international students has identified that it is often attributed to the perceived closedness of the broader society (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Tavares, 2021). International students also report experiences of discrimination, often manifested through stereotypes directed at them personally or toward their countries of origin (Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Shim et al., 2014; Tavares, 2021). Some students perceive exclusion based on visible markers of difference, such as skin color (Kim, 2011; Liu and Qian, 2023). Moreover, they report experiences of linguistic exclusion, noting that locals were frequently either unaware of the language barrier or unwilling to use widely spoken languages such as English in the presence of non-native speakers—even when both parties are proficient in that language (Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Liu and Qian, 2023). Social othering was also evident in informal settings, such as shared meals or social gatherings, where language exclusion persisted and a lack of social inclusion was reported—even among students with proficiency in the local language (Laufer and Gorup, 2019). International students often intend and actively attempt to establish contacts with members of the broader society, but frequently report limited opportunities to interact with local peers beyond seminar rooms (Tavares, 2021). They often attribute the limited contact to language barriers, differing cultural backgrounds, a perceived lack of common ground—on which friendships typically are built—as well as insufficient internationalization strategies on the part of universities (McKenzie and Baldassar, 2017; Tavares, 2021). Furthermore, local students often appear disinterested in building new relationships and tend to remain within their established social circles, as they typically already have close connections with other peers—thereby underestimating the importance of such contact for the integration and well-being of international students (Fu, 2021; McKenzie and Baldassar, 2017; Tavares, 2021; Xing and Bolden, 2021).

Relationships with local peers can foster a sense of belonging, ease the process of familiarization with the new environment, and support language acquisition, thus promoting not only social but also linguistic and cultural integration (Tavares, 2021). Experiences of othering, on the other hand, can lead international students to form stronger bonds with their co-nationals or to withdraw socially—thereby shaping their acculturation trajectories toward separation or marginalization (Liu and Qian, 2023; Tian and Lowe, 2018). The attitudes and behaviors of the broader society—whether marked by openness or exclusion—can thus play a critical role in determining the direction of international students’ acculturation trajectories. In light of existing literature that often conceptualizes acculturation challenges to be overcome through adaptation or assimilation of immigrants rather than encouraging mutual adjustments (Liu and Qian, 2023; Mittelmeier et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2008) and given the lack of empirical work in the German context, we aim to examine the role of (social) othering in shaping the acculturation trajectories of international students in Germany, leading to the following research question:

RQ2: In what way do international students experience social othering in the context of acculturation, and how do these experiences affect their acculturation trajectories?

4 The role of othering for health information access

International students must navigate not only a new sociocultural environment but also an unfamiliar healthcare system and information landscape. Especially at the beginning of their migration process, they face the necessity of obtaining information about health insurance, availability and cost of medication, and access to healthcare providers such as local practices, hospitals, and consultation hours (Yoon and Kim, 2014). Furthermore, they often face new health challenges, including dietary changes, the onset of allergies or intolerances, or mental health issues (Carter et al., 2017; Forbes-Mewett and Sawyer, 2016; Udah and Francis, 2022; Yoon and Kim, 2014).

To comprehend, evaluate, manage, and cope with health-related challenges and stressors, individuals typically draw on various health information sources (Chen et al., 2014; Clark, 2005; Halder et al., 2010; Lambert and Loiselle, 2007). The integration of these sources into consistent behavioral patterns is conceptualized as a repertoire (Bachl and Mangold, 2017). The media repertoire approach (Hasebrink and Popp, 2006) emphasizes the habitual use of both traditional and digital media. In our study, as in recent research on health information repertoires (e.g., Bachl and Mangold, 2017; Baumann et al., 2020; Reinhardt et al., 2021), we extend this perspective to include interpersonal sources, including friends, acquaintances, family members, and health professionals. Accordingly, we adopt the broader term information repertoires, which encompasses both media and interpersonal sources.

Information repertoires are shaped by individuals’ constellation of social connections, known as communicative figurations (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2014; Hepp and Hasebrink, 2017). The diversity of an individual’s repertoire is closely linked to the heterogeneity of their social contacts (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2017). In cases of othering, contact with individuals from the country of residence is limited, which in turn can restrict access to (personal) health information sources originating from the country of residence. Moreover, immigrants often experience othering, such as in the form of discrimination or linguistic exclusion, during health services or when accessing written information materials (e.g., Akbulut et al., 2020; Gee and Ford, 2011). This can lead to dissatisfaction with and underutilization of health services and reduced searches for health information (e.g., Brzoska and Razum, 2015; Cogan et al., 2023; Kearney et al., 2005; McKay et al., 2023; Newton et al., 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to identify social and structural barriers that keep international students from accessing health information and contribute to health (information) disparities (King, 2022). Consequently, we ask:

RQ3: In what way do international students in Germany experience othering and other barriers in accessing health information and services?

5 Health information repertoires of international students

Given the barriers international students may face in accessing health information and the challenges of navigating a new information environment, it is essential to investigate which sources they rely on for health information in their country of residence and how they combine these sources into their repertoires. However, most studies examining the health information-seeking behavior of international students have primarily focused on the use of online sources (e.g., Bahl et al., 2022; Braun et al., 2023; Yoon and Kim, 2014) or counseling services (e.g., Masai et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2009; Kearney et al., 2005), overlooking other relevant sources and contexts. Furthermore, several studies have focused on specific health domains, such as mental health (e.g., Braun et al., 2023) or vaccination (e.g., Tung et al., 2022), without addressing students’ general health information-seeking practices, which may serve a broader range of purposes. Nonetheless, these studies offer valuable insights into the health information-seeking practices of this population.

Unlike other immigrant populations (e.g., Chae et al., 2021; Christancho et al., 2014; Islam et al., 2016), international students tend to rely less on traditional mass media and more on digital sources, particularly online platforms and apps, due to their generally high internet use and technological affinity (e.g., Yoon and Kim, 2014). Online sources are often accessed via search engines like Google (e.g., Tung et al., 2022). International students also frequently seek advice through interpersonal communication, often turning to trusted individuals such as family and friends—either face-to-face or via messengers, email, or phone calls (e.g., Braun et al., 2023; Yoon and Kim, 2014). Community organizations such as churches or university health centers serve as additional sources (e.g., Skromanis et al., 2018). Evidence on the role of health professionals is divergent, with some studies reporting utilization of and satisfaction with health services (e.g., Braun et al., 2023; Masai et al., 2021), while others indicate underutilization and dissatisfaction (e.g., Kearney et al., 2005; Newton et al., 2021).

Although previous studies offer insights into the health information behavior of international students, a research gap remains in investigating how international students compose sources into coherent patterns (health information repertoires). Therefore, we ask:

RQ4: Which health information repertoires do international students draw on?

6 The role of acculturation in health information behavior

As mentioned prior, individuals’ constellation of social connections—known as communicative figurations—plays a crucial role in shaping repertoires (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2014; Hepp and Hasebrink, 2017). The diversity of accessible information sources is closely linked to the heterogeneity of individuals’ social contacts (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2017). Consequently, it is essential to examine repertoires within the broader context of people’s communicative figurations (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2017). In the case of migration, communicative figurations refer to individuals’ acculturation trajectories in the country of residence.

Social interaction is a fundamental mechanism of acculturation, entailing the establishment and maintenance of social relationships through personal networks (Esser, 2006). Building on social capital theory (Bourdieu, 1986), extensive and diverse social networks are understood to enhance individuals’ access to (re)sources, including sources of health information (Derose and Varda, 2009; Van der Gaag and Webber, 2008; Song and Chang, 2012). Social capital is typically classified into three distinct types, each reflecting different strengths and functions of social relationships: (1) bonding social capital, which pertains to close relationships with family members and friends; (2) bridging social capital, which involves connections with acquaintances such as neighbors and colleagues; and (3) linking social capital, which refers to relationships with individuals in positions of authority or influence, such as city officials or health professionals (Uphoff et al., 2013; Derose and Varda, 2009; Szreter and Woolcock, 2004; Wang, 2021). Individuals can benefit from these relationships—also in the context of health information access. Prior studies have found that individuals’ network size influences the number of health information sources used, particularly positively influencing consultations with trusted individuals (e.g., Ahn et al., 2022; Song and Chang, 2012). Particularly, bonding social capital is related to overall improved health information access (Derose and Varda, 2009). Furthermore, studies found that individuals undergoing assimilation or integration tend to use sources from the country of residence more frequently, while individuals experiencing separation tend to use information sources from their country of origin more often (e.g., Wang and Yu, 2015).

For international students, social capital—shaped by their acculturation trajectories—may influence their access to health information sources and affect their repertoire size, composition, and diversity (Cogan et al., 2023; Hofhuis et al., 2023; Rodriguez-Alcalá et al., 2019). Since the interrelationship between acculturation trajectories and health information repertoires remains underexplored, we conclude by asking:

RQ5: To what extent do health information repertoires vary among international students experiencing different acculturation trajectories?

7 Methods

To address these research questions, we conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with 15 international students in Germany during March and April 2023. The interviews incorporated interactive tools to facilitate reflection and engagement. The integration of verbal and visual data not only enables mutual validation and comparison but also a more holistic interpretation of the data and can contribute to achieving empirical saturation (Heinrich, 2024; Strübing et al., 2018).

Eleven interviews were conducted in person and recorded using a digital device, while four were conducted online via Zoom and recorded using the computer’s recording function (audio only, no video). The interviewees consented to the interviewer taking notes during the interview. Due to her specialized training and experience in both the theoretical and practical aspects of qualitative methods—specifically interviews—all interviews were conducted by the first author herself. Given that the interviewer is a native speaker of German and has advanced proficiency in English, participants were given the choice to complete the interview in either English or German; fourteen chose English, and one opted for German. The average interview duration was 59 min—ranging from 33 to 95 min. Before participation, all students provided written informed consent. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the [institution].

7.1 Sampling procedure and participant characteristics

Participants were recruited via university lectures, mailing lists from the international offices of five universities, and the social media accounts of seven international student associations in Germany. Eligible participants were students who had arrived in Germany no earlier than the summer semester of 2021, intended to remain in the country after completing their studies,3 and possessed sufficient proficiency in English or German to facilitate participation. Accordingly, the recruitment strategy can be characterized as purposive sampling (Ahmad and Wilkins, 2024). Nineteen students responded to the call, of whom two were excluded because they were exchange students, and two others did not respond after initial contact, indicating that they were no longer interested in participating in the study. The final sample comprised fifteen participants, each of whom was assigned a pseudonym reflecting their country of origin.4 Since no new information emerged at a certain point in the data collection, data saturation was considered achieved, and further participant recruitment was deemed unnecessary.

The study sample consisted of eight female and seven male students, with an average age of 28 years (M = 27.73, SD = 5.20), all of non-European origin (see Table 1 for details).5 Nine participants were raised bilingually or multilingually, with Hindi and English being the most frequently spoken first languages. All participants reported advanced proficiency in English. Their German language skills were predominantly at the A or B level, with only two participants achieving C-level proficiency. At the time of the study, participants had resided in Germany for an average of 9 months (M = 9.13, SD = 3.74). Regarding educational background, five held a Master’s degree, eight obtained a Bachelor’s degree, and one completed secondary education.

7.2 Operationalization

The interview guide was organized into four thematic blocks: (1) acculturation trajectories, (2) health information-seeking behavior, (3) changes in health and health information-seeking behavior, and (4) migration-related challenges.

In the section on acculturation trajectories, participants were asked about their interactions with individuals from their country of origin as well as with members of the broader society in Germany (e.g., “How often do you have contact with people from your country of origin?”). Additionally, they were asked to reflect on their engagement with both their heritage culture and the German culture (e.g., “To what extent do you think you have adapted to the cultural way of life in Germany?”). Furthermore, an interactive tool based on Berry’s model of acculturation was employed. Participants were asked to indicate the frequency of their interactions with individuals or groups from the larger society in Germany and their country of origin (see Figure 2 in the Results section). Drawing on the think-aloud technique (Charters, 2003; Mathieu and Pavlíčková, 2017; Noushad et al., 2024), they were encouraged to think aloud during their decision-making process and to reflect on their decisions as well as their own social behavior.

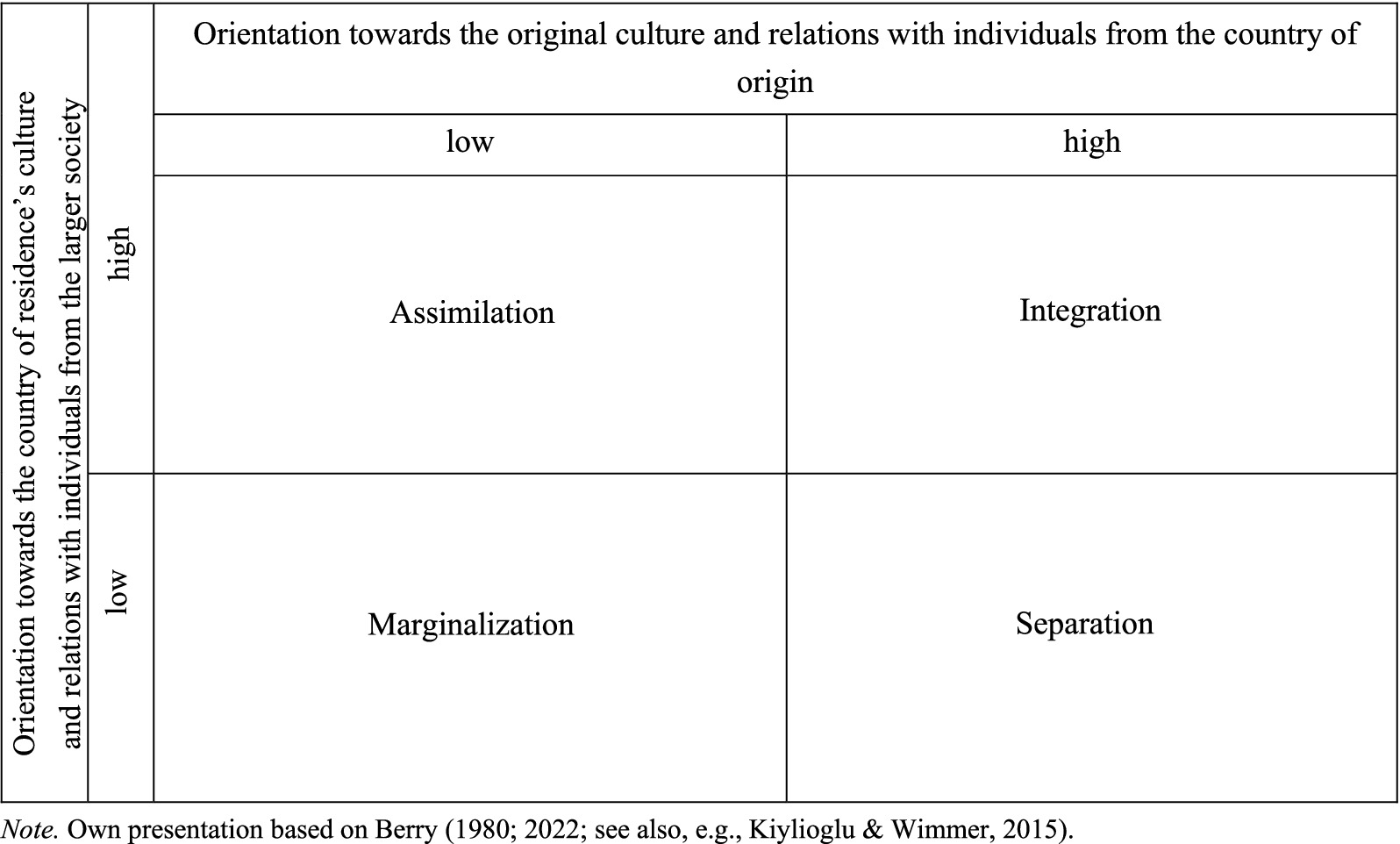

In the subsequent thematic block, participants were asked to describe their general health information-seeking behavior in Germany. This discussion was supported by an interactive method known as repertoire mapping (Merten, 2020). Participants were asked to list the sources they use for health information and to categorize them based on their perceived relevance (see, e.g., Figure 3 in the Results section). Simultaneously, participants are asked to comment on their decisions and to verbalize their thought processes—also drawing on the think-aloud technique (Charters, 2003; Mathieu and Pavlíčková, 2017; Merten, 2020; Noushad et al., 2024). By thinking aloud, participants reflect on their own usage practices, making implicit decision-making processes visible. This verbalized reflection often leads to the identification of previously unremembered sources, which can then be added to the repertoire map. Through thinking aloud, participants elaborate on how different sources are used and the processes through which they are accessed (Merten, 2020).

Figure 3. Repertoires of an online information seeker (left) and an online and interpersonal information seeker (right). Health information repertoires of Alani (left) and Sofia (right). Green circle = country of origin source; orange circle = German source; purple circle = sources from other countries or of unknown origin.

In the next section, the participants were asked about changes in their perceived health, health information-seeking behavior, and access to health information (e.g., “Has access to health information improved, declined, or stayed about the same since coming to Germany?”). In the final section, participants were invited to describe migration-related challenges they had encountered and to reflect on how these experiences had affected their health and well-being in Germany.6

7.3 Data analysis

Following the completion of the interviews, each was initially transcribed by the first author, who had also conducted the interviews. The interviews were transcribed in the language in which they were conducted. The interview conducted in German was therefore not translated into English, as all researchers involved in analyzing this interview possessed native-level proficiency in German. At the same time, all researchers involved possessed advanced-level proficiency in English. Transcription was conducted according to the rules of content-semantic transcription as outlined by Dresing and Pehl (2018). Each transcript was checked by two independent researchers with the appropriate language skills.

A qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz, 2016; Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2024) was performed on the interview data using MAXQDA Analytics Pro (version 24.7.0). The code system was developed using an inductive-deductive approach and was subsequently reviewed to ensure intersubjective comprehensibility. The first author initially read the transcripts to derive preliminary main categories. These were based on the theoretical framework, the existing literature, the interview guide, and the data itself. Relevant text segments were then assigned to the main categories, and subcategories were developed. This process was conducted iteratively until all relevant text segments were categorized and no new categories emerged (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2024). Since no new information or categories emerged at a certain point of iterative coding, data saturation was considered to have been achieved.

The analysis was primarily conducted by the first author (of German origin), with support and validation provided by an independent researcher from another German university (also of German origin) and two student assistants employed at the [institution] (of non-German origin and with own migration experience)7—all of whom had training and experience in conducting, analysing, and interpreting qualitative data. All researchers involved in the data analysis had access to the MAXQDA project file, and thus to the coding system, the full interview transcripts, and the applied codes.8 This step was necessary to enhance transparency and external validity, as well as to verify its clarity and interpretability from an outside perspective.

Data analysis and interpretation were carried out iteratively and collaboratively between the first author in close exchange with the supporting researchers. Regular team discussions were held to critically examine the coding process and emerging interpretations, and to integrate multiple perspectives on the material. This collaborative approach fostered interpretive depth and minimized the influence of individual bias (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2024). Reflexivity was maintained through ongoing documentation of interpretive decisions and reflections on the researchers’ positionalities in analytic memos, which served as an integral part of the analytic process. Furthermore, analytic transparency was ensured by systematically tracing the development of codes over time (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2024). Detailed records of these analytical steps enabled a clear reconstruction of how the analysis progressed from raw data to higher-order conceptual interpretations. Decisions regarding data saturation were made jointly, ensuring that the dataset provided sufficient depth and diversity of perspectives.

8 Results

8.1 Acculturation trajectories (RQ1)

Based on the reported contact frequencies and considering cultural practices described in the interviews, seven participants can be classified as experiencing integration, four as experiencing separation, and two as experiencing assimilation. No participants exhibited patterns consistent with marginalization. These classifications are supported by participants’ self-assessments of their contact with individuals from both Germany and their countries of origin (see Figure 2).

Except for two participants undergoing assimilation, all participants reported frequent contact with individuals from their countries of origin, with reported contact ranging from a few times per month to daily interactions. Most participants maintained regular communication with family members and friends from their countries of origin. Some participants had partners from their countries of origin, reported staying in contact with their general practitioners back home, or being involved with communities in Germany and regularly participating in their events. For many participants, maintaining contact with individuals from their country of origin is important for staying informed about current events and life back home, receiving emotional support, or providing support to others.

“Because many are responsible for some people back home. […] Like, you keep mind on their needs. Mostly financial. Sometimes, you know, psychological. And so, now that you are here, people will consider reaching out to you for assistance.” (Tayo, 38, Nigeria).

At the same time, local connections with people from their country of origin in Germany9 are particularly valuable, as they often share similar (migration) experiences and have already navigated certain challenges. Such contacts can offer practical assistance, such as helping with bureaucratic applications or finding a family doctor.

Considering cultural behavior, while some participants indicated that preserving the traditions and lifestyle from their countries of origin was not particularly important to them, many actively maintained aspects of their original culture—particularly through cuisine and by continuing traditional practices and celebrating festivities.

“It’s very important because it makes you feel like you have not lost yourself. You have not lost who you are and where you are coming from. Your background, you know. So it’s really, really important for me to keep my African culture. VERY important to me. […] So, like, my African culture, that is me.” (Jessica, 30, Ghana).

The extent of participants’ connections with individuals from the majority society in Germany varied considerably. In line with Berry’s model, those identified as experiencing assimilation or integration tended to have more frequent interactions with the broader society than those categorized as experiencing separation. Contact frequency ranged from multiple daily interactions to minimal engagement, limited primarily to routine situations such as shopping. Some participants developed relationships with Germans through university, part-time employment, or private networks. Notable differences emerged in the depth of these relationships: while some participants reported forming close friendships or even romantic partnerships, others described frequent but rather superficial relationships.

For some participants, access to individuals from the majority society in Germany was particularly limited at the beginning of their migration process due to the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many experienced feelings of loneliness, depression, and isolation, which were exacerbated by their status as foreigners.10 Some had received vaccines not recognized in Germany, further restricting their mobility and participation in public life. As a result, many were confined to their homes for extended periods and were only able to engage in university activities through online formats.

“And we arrived during the pandemic. It was very hard. […] Yeah, loneliness was a factor, especially during the pandemic. And that’s, I would say, MAINLY because of the pandemic, because […] all the events, all the parties, everything was closed, and that made it worse.” (Emanuel, 31, Brazil)

Participants who had established closer relationships with members of the majority society in Germany reported that these interactions played a crucial role in helping them navigate their new environment. Such contact provided support in understanding bureaucratic procedures and the healthcare system, accessing translation assistance, facilitating integration, and offering opportunities to practise the German language.

“It’s very important for the people to have contact with people from the country you are living in. […] Because some things are new to me. So I need to know some things, so I just call up my friends. I’m asking them up, ‘Okay, hey, can you explain with this? What is this? How this process has to be done?’.” (Ramesh, 22, India).

Many participants reported having adapted to aspects of the German lifestyle and culture, particularly through language acquisition, trying German cuisine, and participating in local festivities, such as Carnival, Oktoberfest, or Christmas—celebrations that are generally not part of the cultural traditions of some of our non-European participants. Some forms of adaptation are also evident in changes to the structure of everyday life and in participants’ behaviors and communication styles.

While some critically reflected that they had not yet fully adapted, all emphasized the importance of adapting to the way of life in Germany. This adaptation was seen as a sign of respect, a way to avoid offending, and a means to better understand German society, thereby facilitating social connections and laying the groundwork for a long-term stay. At the same time, many participants stressed the importance of maintaining their own cultural identity alongside this adaptation.

“I want to respect the place I’m at obviously, and I want to respect people’s boundaries and people’s culture and people’s norms and expectations. So I try my best to, I guess, do them, within something that also is okay within my values and my morals. So I’m not going to be rude to people […]. That’s also something I respect. So I think it’s very important because I’m the one coming to Germany, so I should be able to adapt to Germany.” (Aya, 23, Morocco)

In summary, our findings indicate that participants predominantly exhibited experiences of integration and separation, with two cases reflecting experiences of assimilation. Notably, the frequency of contact with members of the broader German society varied significantly among participants. Although all participants made efforts to integrate both culturally and socially, many reported that they had not fully succeeded—an outcome that cannot be attributed solely to their own behavior. In line with recent studies examining acculturation trajectories, we adopt a reciprocal and dynamic perspective that also considers the behavior of the majority society. In the following section, we further examine and critically assess the role of social behaviors—particularly othering practices—within the broader German society in shaping participants’ acculturation trajectories.

8.2 Experiences of othering in the context of acculturation (RQ2)

Establishing contacts and relationships with people from the majority society in Germany is essential for successful integration. However, acculturation is not always a fully intentional or controllable process (Fox et al., 2017a), since it is also dependent on the inclusivity of the larger population. In the interviews, many reports of othering behavior by the larger society in Germany became apparent.

Participants frequently reported that fellow students and colleagues from the majority society in Germany often showed little interest in maintaining contact outside of university or the workplace. They were described as diplomatic and direct, with communication perceived as predominantly functional. As a result, some participants found it difficult to establish private or more personal relationships with members of the larger society. Accordingly, some participants—particularly those undergoing assimilation or integration—reported that although they very frequently interact with individuals from Germany, these interactions tend to remain superficial, and they have not yet formed any deep or meaningful relationships.

Furthermore, participants noted that Germans often tend to keep to themselves and are generally perceived as reserved and less welcoming—particularly towards individuals with a migration background. Germans were said to be reluctant to engage in conversations conducted in languages other than German. In everyday situations, some participants reported being deliberately dismissed or ignored when they spoke no German or only limited German. As a result, some international students experienced exclusion, social othering, and discrimination based on language barriers. Owing to these forms of social exclusion, participants reported feelings of loneliness or depression, particularly during the early stages of their migration process.

“I think we mainly international students in our master’s degree keep to ourselves. Not that we don’t want to talk to German students. I feel like German students are a little closed with each other. They already have their group of friends, and they also probably want to speak in their own native language.” (Aya, 23, Morocco).

In addition to experiences of disinterest, perceived social closedness, and linguistic exclusion—which may, in some cases, occur unintentionally—some participants also reported instances of deliberate exclusion by their fellow students and colleagues. This was particularly evident concerning activities outside of university or work, where they were not included in plans.

“I think Germans are quite straightforward. […] They can make a plan in front of you, not including you, and they wouldn’t feel it is awkward. But we do feel, okay, if you are not including me in the plan in front of me. But now I’m used to it. […] I felt left out at times, because I stayed with them, I talked to them, and then when have their dinner plan, so they don’t include me.” (Ramesh, 22, India).

Some participants also reported experiences of racism and discrimination based on their background, visible characteristics, or language—either through their own encounters or those of close contacts or acquaintances with a migration background. Due to prejudice and discriminatory attitudes, some international students also faced challenges in securing housing, such as finding a shared apartment or rental accommodation,11 or obtaining part-time employment.

“It took me four months and more than seventy messages to get two WG castings out of it. […] So I think there is a lot of prejudice against, like, the foreigners.” (Tarak, 30, India)

Some participants reported instances of racism and discrimination in their workplace. Others described perceiving prejudiced attitudes in everyday life, even when no explicit remarks were made.

8.3 Othering and other barriers in accessing health information (RQ3)

Experiences of othering occurred not only in private, everyday social interactions but also in the context of accessing health information and services. In the interviews, participants described various instances of othering behaviors by health professionals and highlighted structural barriers that limited their access. The most frequently mentioned barrier was difficulties with finding a general practitioner and securing appointments for medical consultations. Many participants reported being repeatedly turned away by medical practices because no new patients were accepted. Even in cases of severe symptoms or pain, participants were—if at all—only accepted as exceptions. Some reported having to wait several months for an appointment despite experiencing acute health issues. Even when appointments were scheduled, participants sometimes reported having to wait several hours before being seen by a healthcare practitioner.12 Only a few participants reported having a family doctor in Germany.

“[…] it takes forever to get an appointment with a German doctor. And in Russia, it doesn’t work like that. If you have an issue, you go and solve it right away. You don’t wait for months until you will get an appointment. […] I’m like, ‘What? What if I will die while I’m waiting?’ […] I would not want to wait for two months to get checked. So yeah, that’s why I use professional websources.” (Daria, 23 Russia).

Another barrier to accessing health services involves issues related to health insurance. Participants reported difficulties understanding the distinction between private and statutory health insurance in Germany, as well as uncertainty about which services were covered under each system. Challenges were also mentioned regarding the process of signing up for health insurance, along with concerns about the high cost of insurance in Germany compared to that in their countries of origin. Some international students also expressed general difficulties understanding the German healthcare system, particularly at the beginning of their stay. They reported a lack of guidance and support in navigating key processes—such as how to change health insurance or the importance of registering with a general practitioner early on.

“I did not know that I was supposed to change my health insurance three months after I came, otherwise […] I would have to go with the private one for till the end of my student career. […] It would have been REALLY nice if somebody told me. […] so now I have a private insurance and I can’t change it, no matter what I do, unless I no longer am a student. So that sucks.” (Aya, 23, Morocco).

Othering in the context of accessing health information and services was experienced by many participants in the form of linguistic exclusion and discrimination resulting from language barriers. Several participants, lacking sufficient proficiency in German, searched for English-speaking health professionals—often unsuccessfully. While they were generally able to communicate to some extent with German-speaking doctors, they reported significant difficulties in understanding medical explanations. Some relied on translation software to comprehend what health professionals were telling them. Printed informational materials, notices in medical practices, and online health information were also often not available in English. Others described situations in which they were hung up on when trying to make a doctor’s appointment by phone as soon as they spoke English instead of German.

“You can’t book the appointment online, unless you call them. And then when you call, I can’t speak German. So they either put the phone down, like, they just, ‘Kein Englisch. Kein Englisch’, and just cut off the line like that. […] Most of the doctors don’t speak English. […] The challenge was the language barrier. I need to go with the translator. And that was the big challenge for me to understand it here […].” (Jessica, 30, Ghana).

Some participants reported dissatisfaction with health services and medical consultations, which they attributed both to the perceived low quality of care and discriminatory behavior. Consultations were often described as impersonal and superficial. Several participants felt that doctors doubted the legitimacy of their symptoms, reporting that they were not taken seriously and thoroughly examined.

“Because it’s a very intimate topic, your health, and you want to meet a professional that would also be a human being, not only treat you like a[n] object. […] I’m afraid of facing someone who would treat me like a chair. […] It gives you the image of not to really trust doctors. […] They will just say, ‘Stay at home and drink tea’, or anything like that. […] But there is an annual check-up that I do. It’s coming soon. But I don’t think that I will do that here in Germany. I would probably do that in Russia. I will just wait for it.” (Daria, 23 Russia).

Participants also reported both direct and subtle experiences of discrimination based on their origin or limited German language proficiency. Some felt they were treated more rudely and in a patronizing manner because of their background.

“I don't know, maybe the work stress, they seem a bit less empathetic to me. It’s a harsh criticism, I know. But then, this is what I noticed from that. […] here, they seem a bit less empathetic towards people of /. I don’t want to whine about it, but then they don’t want to spend time with you if you are, like, a bit different.” (Tarak, 30, India).

Many participants stated that language barriers and experiences of othering had significantly hindered their healthcare and health information access. As a result, they reported visiting doctors less frequently in Germany than in their countries of origin. Some said they preferred to wait until their next visit home to see their general practitioner there and to rely more heavily on online sources for health information rather than seeking in-person consultations with doctors in Germany.

“So in Pakistan, I did not use to search so much from Google. I did not use to search online and read blogs too much. But here I do that because in Pakistan […] the doctors were, like, directly available.” (Uma, 25, Pakistan).

“I rely a lot more on the Internet here because back home I would just go to the doctor […] and that also, you know, kind of puts me off because if you're sick, you have to search for a doctor, things like that.” (Priya, 32, India).

8.4 Health information repertoires (RQ4)

Due to these barriers and the unfamiliar information environment, many participants reported changes in their information-seeking behavior compared to their countries of origin. These changes were shown in the sources participants use for health information, and particularly in their repertoires.

Looking at the sources participants generally used, all reported using online sources, including platforms such as YouTube, official government and health insurance websites, health apps, online research articles, and Wikipedia. Many relied on search engines like Google to locate relevant information online. For most participants, search engines and digital sources were considered equally important—or even more important—than consultations with health professionals. For most, the internet—particularly Google—was the primary point of reference for addressing health-related questions.

“So in Germany, what is the first thing I do is that I search it online when I have a problem. So I just use Google. And there’s just Healthline, an article, a website. So I read articles from there usually (…) and see what I can do to treat.” (Uma, 25, Pakistan).

Most participants reported having visited a health professional in Germany at least once. Participants with specific health needs—such as Jessica, who has a chronic illness, and those who rely on prescription medication—reported regularly consulting health professionals. While some participants indicated that they attend regular check-ups, others stated that they had only consulted a doctor a few times—or, in some cases, not at all. Notably, five participants did not consider health professionals to be part of their health information repertoire, either because they had never visited a healthcare provider in Germany or because they did not view such consultations as important.

“In Germany, I go to [the medical centre]. But I’ve been there once in two years. I’m hoping that I don’t have to go to the doctor here. I find it very complicated. I do not understand.” (Priya, 32, India).

“Because I’m on private insurance and because I don’t speak the language, I try to avoid doctors as much as possible. Unless something severe comes up.” (Aya, 23, Morocco).

Trusted individuals, such as family members and especially friends, were identified by most participants as frequently used and important sources of health information. Some participants also reported continuing to use medicine and traditional remedies from their countries of origin.

“Sometimes I’m able to tell what’s going on with me, but if not, then I can go to my mom. So I just call her, ‘Yeah, I am facing this issue. So can you just help me out?’ And then she tells me. Because when I came from India, I have this big medicine box with me with the prescription of doctors. […] She also has a photo and then she search it out. […] Because she marked the numbers on the medicines. So she said, ‘We see that is number seven. This is for this. This is for this. This is for this’. And they are sending the prescription how it has to be taken, and I do it. […] That’s why I’m not with a doctor here. […] if it’s something she cannot also tell, then I or she contacts to the family doctor we have in India. Because he has been looking at me since the last, I guess, eighteen years now.” (Ramesh, 22, India).

Traditional mass media were rarely mentioned by participants. When they were, participants noted that these sources were considered relatively unimportant for obtaining health information.

Looking at how international students combine these sources into repertoires, two participants—Alani and Ravi—indicated solely relying on online information sources for health information (Online Information Seekers), while all other participants combined both online and interpersonal sources (Online and Interpersonal Information Seekers).13 While Ravi included a dentist he had visited once in Germany in his repertoire map, he stated that he had not consulted any other health professionals and did not name any additional interpersonal sources.

“It’s online device everything. Just on Google I search something. […] I didn’t ask anybody or go to a health information provider. Just whatever Google search results show up. Yeah, I didn’t look at any preference that what website I’m looking at or which resource it’s coming forward. Like, just reading in Google searches, three or four different resources.” (Alani, 27, India).

“So my first reaction, if I have a curiosity or a problem, I would probably ask my wife, if she knows something. And then if she doesn’t know […], then I will probably use my cellphone, my smartphone to use Google and Google it.” (Emanuel, 31, Brazil)

The variations between Online Information Seekers and Online and Interpersonal Information Seekers were evident not only in terms of the diversity of sources used but also in the overall quantity. On average, Online and Interpersonal Information Seekers accessed considerably more information sources than Online Information Seekers (see Figure 3 for repertoire examples).

8.5 Interrelationship between acculturation and health information repertoires (RQ5)

Concerning the repertoires of Online Information Seekers and Online and Interpersonal Information Seekers, only minor variations were observed across individuals experiencing different acculturation trajectories (see Table 2). The two Online Information Seekers were classified as experiencing assimilation and integration. However, they reported frequent but rather superficial contact with members of the majority society in Germany. As a result, their access to trusted interpersonal sources was limited, which may explain their stronger reliance on online sources. Nonetheless, no noticeable pattern could be identified regarding the assignment of acculturation trajectories to the repertoire types. However, a closer look at the combination of sources and their origins reveals a more pronounced picture.

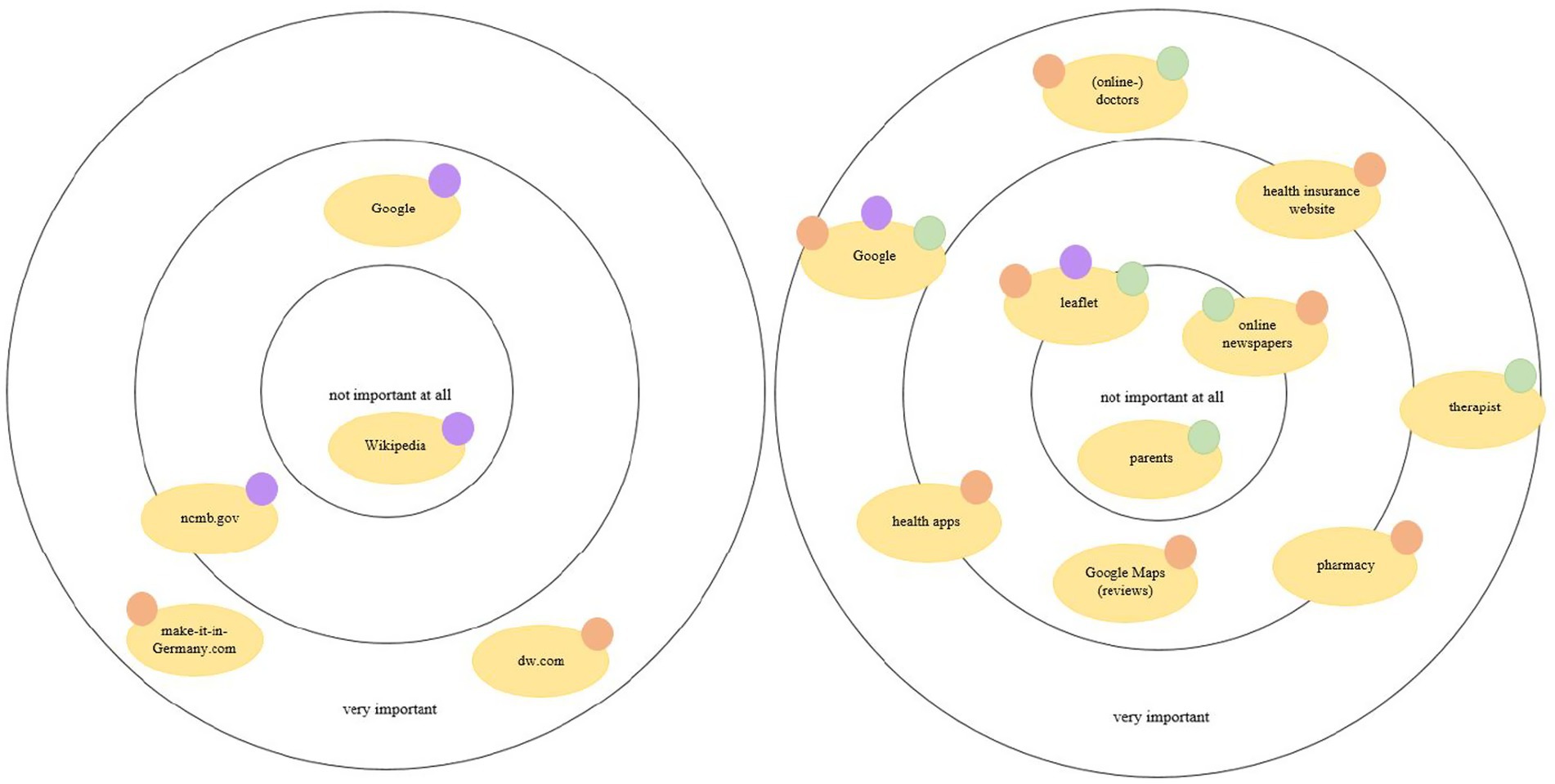

The interview data and repertoire maps further reveal that participants undergoing assimilation—if at all— tend to consult confidants from Germany rather than from their countries of origin (see Figure 4 for repertoire examples). They therefore tend to rely less on bonding or bridging social capital. They reported consulting health professionals in Germany—Alex regularly, Ravi only once—but not those from their countries of origin. Accordingly, if they rely on experts at all, they tend to place their trust in linking social capital within Germany. Regarding online sources, they predominantly used sources of unknown or international origin, as well as sources from their country of origin, but not those of German origin. Written information in German is therefore avoided.

Figure 4. Repertoire of a participant experiencing assimilation (left) and separation (right). Health information repertoire of Alex (left) and Uma (right). Green circle = country of origin source; orange circle = German source; purple circle = sources from other countries or of unknown origin.

“I am using English most of the time. […] Yeah, usually I didn’t go to many sources written in German because I’m not searching for that.” (Alex, 36, Australia).

Participants experiencing separation only consulted trusted individuals from their countries of origin for health information, but not individuals from the larger society in Germany—if at all, the latter were considered unimportant sources. Confidants from their countries of origin were generally categorized as (very) important. They thus often rely on bonding social capital from their country of origin for health information.

“[…] I usually contact my friends or family. My [Pakistani] friends in Germany and my family in Pakistan. So I ask them what I need to do, what medicines I should take. […]. So that’s the second thing I do, like, contact my family and friends.” (Uma, 25 Pakistan).

In contrast, these participants predominantly only consulted health professionals in Germany; except for Tayo, who additionally consulted health professionals from his country of origin. Regarding online sources, participants undergoing separation predominantly used websites of unknown origin or from other countries.

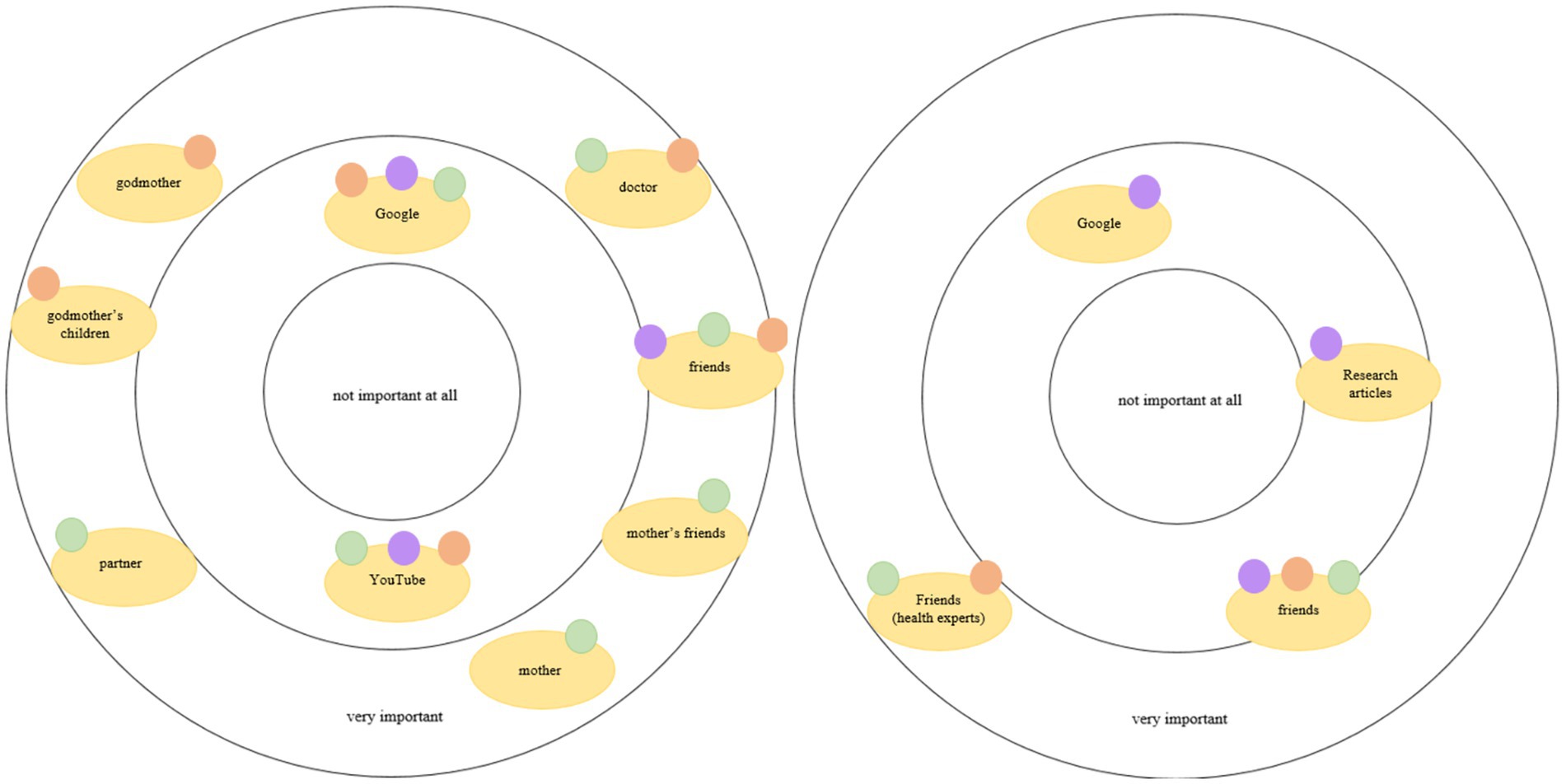

Participants experiencing integration tended to frequently consult trusted individuals from their countries of origin and/or from the larger society in Germany for health information—though confidants such as family members or friends from their countries of origin were mentioned most frequently and often categorized as (very) important information sources by most of these participants (see Figure 5 for repertoire examples). Nevertheless, in many cases, participants relied on bonding or bridging social capital from both their country of origin and Germany.

Figure 5. Repertoires of participants experiencing integration. Health information repertoire of Priya (left) and Tarak (right). Green circle = country of origin source; orange circle = German source; purple circle, sources from other countries or of unknown origin.

“If I have any issue, I have a best friend and he’s a doctor. So it’s pretty convenient, especially when you are hypochondriac. So I talk to him. […] I try to consult with the online stuff and with my friend. And that’s it. I’m pretty satisfied with that. […] With mom, because […] she has known my body since I was a child. So I think that probably she even knows me in some of the ways better.” (Daria, 23, Russia).

“You know, it’s best to ask people. I don’t refrain from it because there’s always Germans around me, and then I always go for it, unless it’s like extremely private.” (Tarak, 30, India).

Notably, although some participants experiencing integration reported consulting health professionals from their country of origin and/or from Germany, this group was the only one that also included participants who reported not consulting health professionals at all. The use of linking social capital within this group, therefore, varies considerably. Regarding online sources, all participants used websites of unknown origin or from other countries; many additionally relied on online sources from Germany and/or their country of origin.

The diversity of contacts and (potential) information access points is also reflected in the repertoire sizes across the groups. On average, individuals experiencing integration showed a slightly larger repertoire size than those experiencing assimilation or separation—particularly due to their larger use of bonding and bridging social capital.

9 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of othering in shaping acculturation trajectories and health information access through a qualitative interview study. It yielded important insights into international students’ health information-seeking behaviors and the barriers they face in accessing interpersonal networks and health information and services in Germany.

Regarding acculturation trajectories (RQ1), participants could be classified as experiencing integration, separation, and assimilation; none of the participants were undergoing marginalization. These findings align roughly with prior studies (e.g., Cao et al., 2021; Sullivan and Kashubeck-West, 2015), indicating that most international students experience integration, while experiences of separation, assimilation, and marginalization are less common. However, our results align more closely with studies conducted in other countries (e.g., Cao et al., 2021; Sullivan and Kashubeck-West, 2015) than with those conducted in Germany among East Asian international students (Shim et al., 2014)—some of whom, however, were born in Germany and only had a family migration background, and who differ culturally and ethnically from most of our participants. The findings underline that acculturation is a highly individual process, shaped by multiple factors such as ethnical and cultural background—or cultural and geographical proximity to the country of residence (e.g., Lee and Rice, 2007; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007; Shim et al., 2014)—regional context, and personal experiences (e.g., Ranabahu and De Silva, 2024). Time may also be an important factor, that is, how long international students have already lived in the country of residence; however, the exact duration of residence is often not reported in previous studies. Overall, regarding RQ1, this study provided initial findings on the acculturation trajectories of international students in Germany across a broad range of ethnic backgrounds and fields of study at the beginning of their migration process.

Participants’ acculturation trajectories were also shaped by othering experiences, particularly among those experiencing separation (RQ2). In everyday life—aligning with findings from studies conducted in other countries (e.g., Fu, 2021; Laufer and Gorup, 2019; McKenzie and Baldassar, 2017; Tavares, 2021)—participants experienced social othering primarily through the perceived closedness, disinterest, and unwelcoming attitudes of the broader society in Germany. Some participants also reported experiences of discrimination, stereotyping, and deliberate social or linguistic exclusion (e.g., Laufer and Gorup, 2019; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007; Shim et al., 2014; Tavares, 2021). Some participants downplayed instances of discriminatory behavior, interpreting them as typical interaction patterns in Germany to which one simply has to adapt, viewing such situations as part of everyday life (e.g., “My wife and I sometimes debate about that, because for me, sometimes it’s hard to tell if it’s discrimination or if it’s just the German way.” Emanuel, 31, Brazil). Precisely because our participants have non-European backgrounds—as prior studies suggest (e.g., Lee and Rice, 2007; Liu and Qian, 2023; Pérez-Rojas and Gelso, 2020; Poyrazli and Lopez, 2007; Shim et al., 2014)—differences in culture, norms, language, and outward appearance played an even greater role in their experiences, and instances of othering were correspondingly more pronounced. These perceptions and experiences hindered their ability to establish connections with the larger society. Additionally, external circumstances—particularly the COVID-19 pandemic—further hindered integration in the early stages of their migration process and had a considerable impact on the acculturation trajectories of our participants at the outset of their migration. Under such extraordinary circumstances, international students may rely more heavily on their existing social networks for social and emotional support (e.g., Hari et al., 2021), which in turn limits their contact with individuals from the broader society in Germany—who may also rely more on their existing and trusted social networks and avoid forming new contacts due to the uncertain situation (e.g., Phuong et al., 2025; Taubert et al., 2023). Regarding RQ2, the results therefore indicate pervasive experiences of othering among international students, particularly pronounced among those who differ more from the broader society in terms of cultural and ethnic proximity as well as appearance. Being perceived as “different” or foreign especially hinders the formation of social contacts—which was pronounced during the pandemic.

In accessing health information and services (RQ3), othering manifests in linguistic exclusion and dismissive or discriminatory behavior by health professionals—as has also been found in other studies (e.g., Akbulut et al., 2020; Gee and Ford, 2011). Informational materials are often available only in German, and language barriers pose significant challenges during doctor-patient interactions. Practitioners are often unable or unwilling to speak languages other than German. Several participants reported perceived differential treatment based on their status as foreigners, describing instances in which they felt not taken seriously or treated only superficially by physicians. Some even recounted experiences of discrimination during medical treatment and being denied access to healthcare services due to limited German language skills. Such experiences of othering in healthcare affected participants’ health information-seeking behavior. Several participants reported visiting doctors less frequently or actively avoiding health services in Germany. The reduced use of health services and dissatisfaction with the services provided in the country of residence were also evident in previous research (e.g., Cogan et al., 2023; Newton et al., 2021). As a result—and due to their general digital affinity—aligning with findings of prior studies (e.g., Tung et al., 2022; Yoon and Kim, 2014), our participants reported to frequently rely on online sources as a primary means of obtaining health information, often using search engines, particularly Google, to locate relevant content. Furthermore, most participants rely heavily on trusted individuals for health information (e.g., Braun et al., 2023; Yoon and Kim, 2014). However, unlike findings from other studies (e.g., Skromanis et al., 2018)—while participants reported being involved in communities—none mentioned consulting community members regarding health-related issues. In line with the divergent findings of previous studies (e.g., Braun et al., 2023; Masai et al., 2021; Newton et al., 2021), the use of health professional consultations among our participants is ambivalent: some report regular consultations and high levels of satisfaction and trust, while others express dissatisfaction and non-use due to prior negative experiences. Notably, many participants spoke about mental health challenges, strong feelings of loneliness, and even depression—yet only one reported seeking support from a therapist. It is also noteworthy that only five participants included dentists in their health information repertoire—and among them, one even categorized this source as unimportant. Traditional mass media are generally not accessed proactively (e.g., Yoon and Kim, 2014). The results regarding RQ3 therefore point to significant issues of othering in the treatment of international students—and migrants more broadly—as participants reported discriminatory behaviors by medical staff during doctor visits, ranging from a refusal to speak English to hanging up the phone when scheduling appointments. These experiences led some international students to visit doctors less frequently and instead rely more on other sources, particularly online sources.

Regarding participants’ combinations of sources into repertoires (RQ4), most reported using both online and interpersonal sources to seek health information (Online and Interpersonal Information Seekers). Two individuals relied exclusively on online sources (Online Information Seekers). The results provide—for the first time—an overview of the health information repertoires of international students in Germany, encompassing a wide range of health information sources and covering a large spectrum of health-related topics. In the case of at least two participants who generally obtain health information exclusively from online sources, these results indicate major limitations in their access to interpersonal sources. These insights were made possible, particularly because the media repertoire approach was expanded to include an interpersonal dimension in this study, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the health information repertoires of international students in Germany.

While no substantial variations in the assignment of repertoire types were observed across participants with different acculturation trajectories, a closer examination of their health information repertoires revealed a more nuanced picture (RQ5). Participants experiencing assimilation tended to consult international online sources, and—if at all—rely on trusted individuals and health professionals from Germany. In contrast, those undergoing separation turned more frequently to confidants from their country of origin. At the same time, however, they also reported consulting health professionals in Germany, and tended to primarily use international online sources. Participants experiencing integration had more diverse interpersonal networks and reported more than those experiencing assimilation or separation to draw on trusted individuals from both Germany and their country of origin. While some reported consulting health professionals from either or both contexts, many within this group did not use health services at all. Online sources used by this group were predominantly international but often supplemented by sources from Germany and/or the country of origin. Overall, the results regarding RQ5 provide initial indications of an interplay between acculturation trajectories and the health information repertoires of international students in Germany, indicating that participants’ health information repertoires closely reflect their respective acculturation trajectories—particularly in terms of access to confidants (bonding social capital) for health information.

In summary, this study examined, for the first time, the interplay between experiences of othering, acculturation trajectories, and health information access among international students in Germany. Acculturation trajectories—shaped by the openness or closedness of the broader society—seem to particularly play a role in accessing trusted individuals (bonding social capital) as sources of health information. Access to health professionals (linking social capital), on the other hand, appears to be shaped less by acculturation trajectories and more by individual experiences and attitudes towards health consultations. This is particularly reflected in the considerable variation in the use of health services observed within the group of participants experiencing integration, and the relatively frequent reports of consultations with German practitioners among participants undergoing separation. Other studies have similarly shown that social capital tends to positively influence the use of trusted individuals as sources of health information, but not the use of health professionals (e.g., Song and Chang, 2012). Overall, our findings suggest an interrelationship between acculturation trajectories and participants’ health information repertoires—not particularly in terms of their average size, but rather in the composition and diversity of sources.