- 1Communication Science, Universitas Ciputra, Surabaya, Indonesia

- 2Digital Public Relation Studies Program, Telkom University, Bandung, Indonesia

Amid intensified political competition during Indonesia’s 2024 General Election, this study examines how broadcasting regulators enforced ethical standards under structural, commercial, and ideological pressures. Using a qualitative case study method, it draws from institutional documents, official reports, and interviews with broadcasting practitioners in West Java to analyze the challenges faced by the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) and its regional counterparts (KPID) in maintaining media neutrality. Findings show that politically biased content and premature campaign materials were frequently aired by national broadcasters, often influenced by partisan ownership and central editorial control. Local stations lacked authority to intervene, as the National Network System (SSJ) limited regional oversight and contributed to inconsistent enforcement. Regulatory actions were largely reactive, relying on post-violation warnings rather than proactive prevention. The study applies critical media theories to reveal how market competition, structural asymmetries, and blurred boundaries between journalism and political promotion undermine regulatory independence. It concludes that Indonesia’s current broadcast regulation system remains vulnerable to media oligarchy and lacks the institutional resilience needed to protect democratic communication. To address these challenges, urgent reforms are recommended in legal authority, transparency, and civic engagement. This research contributes to broader debates on media governance and electoral integrity in hybrid media environments.

1 Introduction and background

The 2024 direct general election in Indonesia took place on 14 February 2024, involving 204, 807,222 registered voters and electing representatives at multiple levels, including the President, Vice President, members of the House of Representatives (DPR/Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat), Regional Representative Council (DPD/Dewan Perwakilan Daerah), and Regional People’s Representative Councils (DPRD/Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah) across provinces, regencies, and cities (International Foundation for Electoral Systems/IFES, 2024). This condition makes the 2024 general election one of the most significant single-day democratic events globally. Later in the year, Indonesia held its first-ever simultaneous regional elections on 27 November 2024, covering 38 gubernatorial, 415 regency, and 93 mayoral elections, further expanding the scale and complexity of the electoral process (Wilson, 2024). The Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI/Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia) faces significant challenges due to Indonesia’s highly concentrated media ownership, where 12 major conglomerates control over 97% of television viewership and extend their influence into print, radio, and digital platforms (Ambardi et al., 2014). These three waves of elections underscore the growing logistical and regulatory challenges facing Indonesia’s broadcasting institutions and oversight bodies, particularly in ensuring compliance with political neutrality standards during campaign periods.

The role of television as the most consumed form of mass media remains vital to Indonesian political life. Since its introduction during the 1962 Asian Games through TVRI, television has evolved from a government communication tool into a competitive media industry shaped by reform-era liberalization and the rise of commercial broadcasters (Rayhan and Putri, 2020). The 21st century has brought even greater transformation, with digital migration and the proliferation of streaming platforms like Netflix, Disney+Hotstar, and WeTV disrupting the structure of traditional broadcasting (Sapitri and Nurafifah, 2020; Salsabila and Pratomo, 2020). Indonesia’s digital migration, regulated under Kominfo Ministerial Regulation Number 11 of 2021, culminated in the national Analog Switch Off completed by November 2, 2022. Under the DVB T2 digital standard, each 8 MHz frequency channel now carries up to six or eight television streams, enhancing spectrum efficiency but also intensifying the strategic influence of broadcasters over political narratives during high-stakes electoral cycles (Sjuchro et al., 2023).

In parallel, Indonesian society is navigating a new media environment defined by immediacy, fragmentation, and algorithmic amplification. Television still reaches millions of homes, as measured by devices like Peoplemeter connected to over 12,000 households, confirming its continued dominance as a tool for information and political communication (Asih, 2023). However, the growing convergence between broadcast and digital platforms means that television content often competes and sometimes overlaps with viral online narratives, increasing the complexity of political communication in election years.

Mass media’s influence is not only technical or economic but also deeply ideological. In the digital era, audiences act as active citizens who choose, engage, and shape media flows. Television continues to serve as a powerful agenda setter in Indonesia, particularly during election periods. A recent study of TVRI finds that its national media agenda frequently reflects government influence, ownership structures, and editorial policies, often prioritizing official narratives over independent journalistic scrutiny (Razak et al., 2025; Muskita et al., 2023). This situation underscores that media content is never neutral. It reflects layers of intention that shape what is shown, what is silenced, and what is emphasized.

In this contested terrain, the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI/Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia) bears the constitutional responsibility to safeguard ethical and neutral broadcasting, especially during election cycles. According to Law Number 32 of 2002 on Broadcasting, particularly Article 36, paragraph 4, broadcasting institutions must not favor any particular political group or actor (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002). KPI’s role in protecting media integrity and democratic values is thus central to ensuring adherence to campaign regulations and professional standards, particularly in an era rife with negative campaigning and partisan influence (Priyanto and Rahmadante, 2024).

Referring to prior studies, KPI applies three regulatory approaches, which include independent monitoring, public participation, and institutional coordination (Zuwidah and Muzakkir, 2022). However, this oversight often falls short due to limited institutional capacity and the growing complexity of broadcast ecosystems, resulting in frequent public complaints and criticism over inconsistent enforcement (Khusnul and Kushardiyanti, 2022). KPIs’ normative function as a bulwark against political co-optation is increasingly tested in a commercial environment where ratings, advertising, and political sponsorships intertwine (Pranoto, 2020).

To ensure accountability, KPI relies on the Broadcasting Behavior Guidelines and Broadcasting Program Standards (P3SPS/Pedoman Perilaku Penyiaran dan Standar Program Siaran), which prohibit content involving pornography, hate speech, off-period political advertising, and material that targets or discriminates against ethnic, religious, or social groups (Natalia and Ajibulloh, 2023). Such guidelines are especially critical in protecting children and adolescents, who remain highly exposed to violence or sexually suggestive content due to television’s pervasive reach (Siddiq et al., 2020). However, broadcasting institutions also face systemic constraints, including underinvestment, licensing hurdles, advertiser pressure, and increasing competition from streaming and online video platforms (Zuhri, 2021). At the same time, KPI’s enforcement is challenged by discrepancies in its content review standards, such as inconsistencies in censoring soap operas or under responding to spectrum misuse (Aryesta and Selmi, 2022).

This study uniquely integrates national-level KPI violation data with a gatekeeping framework to analyze how political pressures influence regulatory consistency across multiple broadcasting platforms during Indonesia’s 2024 elections. It offers an updated perspective by examining how institutional oversight responds to politically charged violations in both analog and digital-era broadcasting. While existing studies focus on either broadcast content analysis or general election media trends (e.g., Sapitri and Nurafifah, 2020; Rayhan and Putri, 2020), few have examined how structural limitations within KPI itself affect enforcement consistency during political cycles. Prior research has yet to incorporate both national KPI data and regulatory theory to explore the interplay between institutional fragility and partisan broadcasting violations in Indonesia’s evolving media landscape (see Zuwidah and Muzakkir, 2022; Khusnul and Kushardiyanti, 2022).

Based on this context, this study aims to critically investigate the role of broadcasting regulators in maintaining media neutrality and ethical standards during the 2024 Indonesian General Election. These dynamics raise critical questions about the capacity of Indonesia’s broadcasting regulator to operate independently and effectively in a rapidly evolving media environment. As political content increasingly transcends platforms and blurs boundaries between journalism, entertainment, and propaganda, can the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) maintain impartial oversight during election cycles? How do structural constraints, ownership pressures, and digital disruption shape the consistency of KPI’s regulatory enforcement? Moreover, to what extent do the patterns of political broadcasting violations reflect broader institutional vulnerabilities within Indonesia’s democratic communication system? The structure of this article is as follows: the next section presents relevant theoretical frameworks, followed by the research methodology. The findings and discussion analyze key patterns of regulatory enforcement during the 2024 election, while the conclusion reflects on implications for media governance and democratic accountability in Indonesia.

2 Literature review

2.1 Kurt Lewin’s gatekeeping framework in political broadcasting

Gatekeeping, first introduced by Kurt Lewin in 1947, refers to the process by which information moves through channels, with specific points controlled by gatekeepers who determine whether information proceeds or is blocked. Though rooted initially in social psychology, the concept was later adapted by media scholars. Shoemaker and Vos (2009) define gatekeeping as the mechanism that transforms countless bits of information into a limited number of messages that shape public discourse. In mass communication, this framework helps explain how editorial judgment, institutional policy, political influence, and technological change impact the construction of public knowledge. This process is key to understanding how the media filter content and influence societal perception in electoral contexts.

This study applies Lewin’s gatekeeping model to examine the role of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission or KPI during the 2023–2024 election cycle. As the national regulatory body, KPI acts as an institutional gatekeeper for political broadcasting content. Established under Law Number 32 of 2002, KPI is mandated to safeguard content neutrality, promote pluralism, and ensure the public interest in both television and radio. However, KPI’s authority faced mounting challenges during the election period. Political polarization, commercial pressures related to airtime sales, and the transition to digital broadcasting with expanded channel capacity and fragmented audiences made oversight increasingly complex. KPI’s enforcement actions (such as issuing formal warnings, enforcing airtime balance, and sanctioning violations under P3SPS standards) represent gatekeeping in practice. As Voinea (2025) observes, gatekeeping in the digital era is increasingly influenced by algorithmic systems beyond traditional editorial control, exposing new vulnerabilities in the regulation of political content.

2.2 Mass media power: television’s role in shaping political discourse

Mass media remain central to Indonesia’s political communication landscape. Among these, television holds a unique position due to its audiovisual nature, broad reach, and cultural familiarity. The word television derives from the Greek word tele, meaning “far,” and the Latin word visio, meaning “sight,” referring to the transmission of visual content over a distance (Fiske, 2011). Spilker et al. (2020) note that television content involves complex production, requiring both high financial resources and professional personnel. These factors make television highly influential in shaping public perception, particularly during election periods when political actors compete for visibility and legitimacy. The 2024 general elections amplified this dynamic, as commercial broadcasters strategically curated political messages aligned with ownership interests, often beyond the immediate control of regulators. The institutional power of television as a medium thus intersects with the regulatory efforts of KPI, creating both opportunities and challenges for upholding democratic standards in political broadcasting.

2.3 Media ideology as a political medium

Media ideology refers to the underlying set of beliefs and value systems that shape not only what media institutions choose to broadcast but also how they frame reality, it is often reflecting and reinforcing dominant political and economic structures (Hall, 1980). It shapes how reality is constructed, represented, and internalized by audiences. Alamsyah (2020) highlights that the ideological content of media is often hidden behind its entertainment or information functions, making it difficult for audiences to detect. During the 2024 Indonesian elections, these ideological layers became especially visible as various television stations were found to favor particular candidates, omit critical perspectives, or engage in politically biased coverage. This study uses the concept of media ideology to uncover how broadcasting content reflected broader patterns of political allegiance and economic control, and how such patterns posed challenges to KPI’s mission to ensure neutrality and fairness in public communication.

2.4 Agenda setting and regulatory implications

Agenda-setting theory helps explain how mass media shape the public’s understanding of political priorities. Developed by McCombs and Shaw (1972), this theory asserts that media do not tell people what to think, but rather what to think about. Mulyana and Wijayanti (2024) describe three dimensions of agenda setting: representation, persistence, and persuasion. Representation refers to how the media highlight specific issues as necessary, often in alignment with elite interests. Persistence is the media’s power to continuously bring attention to particular topics, sustaining their relevance in public discourse. Persuasion reflects how repeated framing can shape public opinion over time. In the context of the 2024 elections, political parties and candidates strategically used media to set the campaign agenda, while broadcasters played a selective role in what was emphasized or ignored. KPI’s challenge was to monitor and regulate these patterns, ensuring that no single political agenda dominated the public space unfairly. This study uses agenda-setting theory to examine how political violations in broadcast content emerged and how KPI responded to maintain a balanced media environment.

3 Methods

Through qualitative case studies methods, combining in-depth interviews, literature review, and analysis of official violation records, this study investigates how the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) confronts the pressures of political polarization, fragmented audience demand, and institutional fragility, with specific objectives: (1) to examine the regulatory challenges faced by KPI in monitoring political broadcasting content during the election period, and (2) to analyze the types and patterns of political broadcasting violations that occurred, along with institutional responses to these violations. Ultimately, the findings aim to contribute to scholarly debates on regulatory resilience, public accountability, and democratic integrity in Indonesian broadcasting, especially during elections when the stakes for truthful, ethical, and balanced media are highest (Siddiq and Hamidi, 2015).

To answer the research questions, this study employed a case study approach situated within the interpretative paradigm. The case study design was selected for its capacity to explore complex phenomena within bounded real-world contexts (Yin, 2018). KPI’s regulatory role during election cycles is shaped by intersecting dynamics of political contestation, institutional capacity, and public accountability—conditions that are best understood holistically through a case-based approach.

This epistemological stance assumes that knowledge is constructed through social contexts and subjective interpretations, particularly relevant when examining media regulation, institutional enforcement, and political influence (Creswell and Poth, 2018). Given the study’s focus on the institutional performance of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) during the 2024 general election period, the constructivist lens enables a deeper understanding of how various stakeholders (regulators, broadcasters, and civil society) perceive and negotiate broadcast neutrality in a politically charged environment.

This study employed purposive sampling (Palinkas et al., 2015) to identify individuals with direct involvement in political broadcasting regulation and monitoring. To ensure relevance and depth, informants were selected based on three criteria: (1) direct involvement in broadcasting regulation or political content compliance during the 2024 election period, (2) institutional affiliation with either a regulatory body (e.g., KPI/KPID) or a broadcasting entity, and (3) demonstrable knowledge of editorial decisions or policy implementation. The sample/informant included:

• One KPI official from West Java regional offices with roles in policy implementation, complaint handling, and election monitoring;

• Four broadcast editors and compliance officers from two national television stations and one national network radio station;

The selection of West Java as the primary research location was based on its strategic and representative significance in Indonesia’s media and political landscape. As the province with the largest population and media consumption rate in the country, West Java often serves as a bellwether for national broadcasting trends and electoral dynamics. Moreover, the West Java Regional Broadcasting Commission (KPID Jawa Barat) documented the highest number of election-related broadcasting violations during the 2024 General Election cycle, making it a critical site for examining institutional enforcement and broadcaster behavior. Supplementary data from other regional KPI offices, such as those in Central Java, South Sumatra, and Banten, were included to enrich the comparative dimension and reflect broader regulatory patterns across the country.

Data were collected between November 2023 and November 2024, using semi-structured, in-depth interviews, and KPI’s document analysis. Interviews were conducted in person and online, depending on participant availability. Conversations were audio-recorded, transcribed, and anonymized to ensure confidentiality. The documents analyzed include the KPI’s P3SPS (Broadcast Program Standards and Code of Conduct), violation reports, press releases, and institutional coordination records with Pers Council, the General Elections Commission (KPU), and the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu).

Guiding themes for data collection and analysis included:

a. the typology and frequency of political broadcasting violations;

b. The institutional and procedural constraints faced by KPI during the 2024 election period;

c. patterns of regulatory response and public complaint handling;

d. The perceived influence of political parties and commercial pressures on broadcast content.

All qualitative data were analyzed thematically and were analyzed thematically through an inductive and iterative process. Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke (2006) six-phase approach, which includes familiarization with the data, generation of initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming them, and finally producing the report. During the coding phase, transcripts and official documents were manually analyzed using a matrix-based technique. Initial open codes included terms such as “SSJ content override,” “editorial instruction from HQ,” “monetized campaign content,” “regulatory warning response,” and “ownership-political alignment.” These were then categorized into broader axial codes like “institutional constraints,” “commercial influence,” “gatekeeping breakdown,” and “regulatory response pattern.” From this process, four major themes emerged: structural asymmetry in regulatory enforcement, political economy of media content, reactive regulation under commercial pressure, and ideological framing in electoral broadcasting.

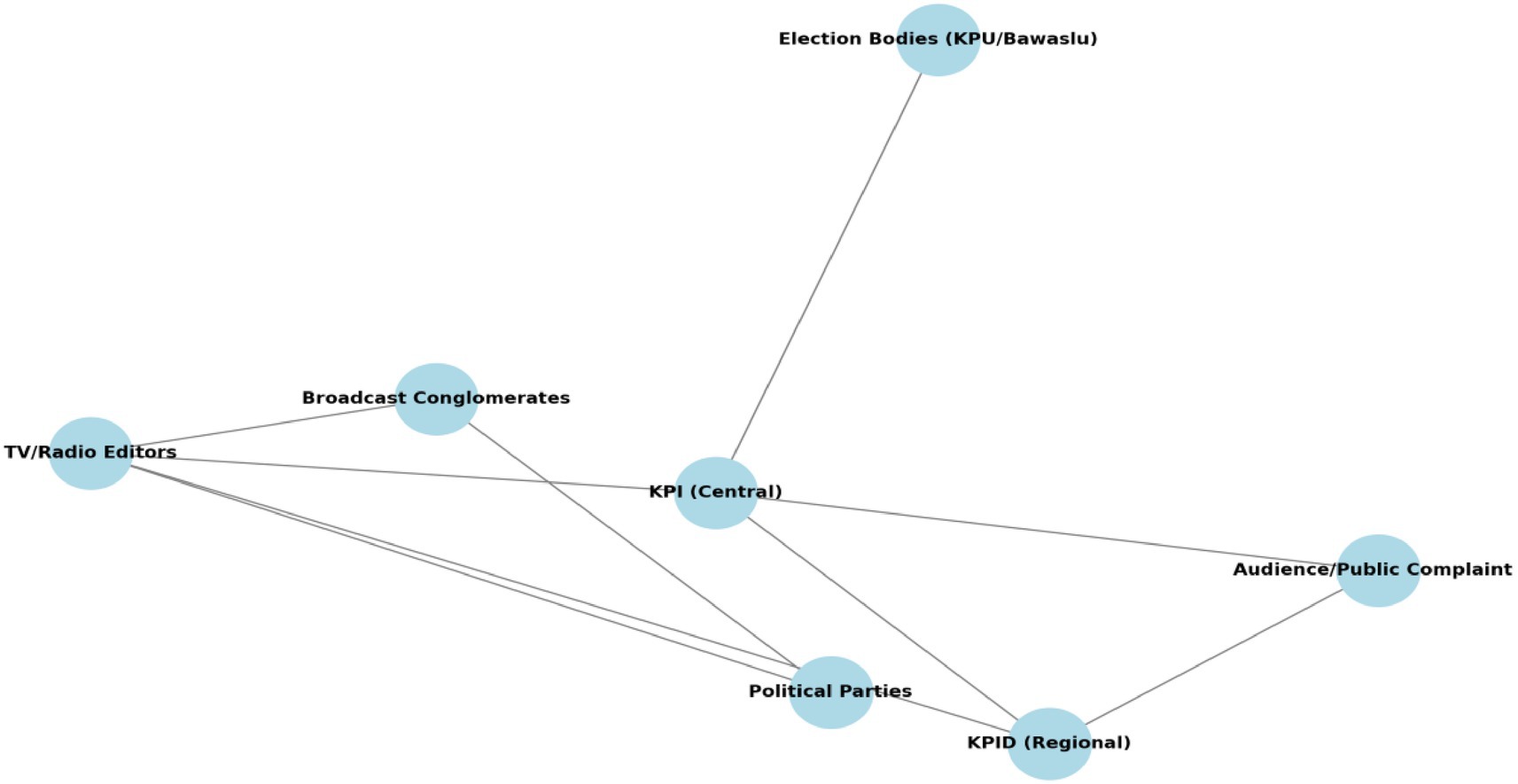

Data saturation was achieved through iterative analysis, whereby additional interviews no longer yielded new insights and existing themes were consistently reinforced across diverse data sources. To enhance analytical rigor, triangulation was applied across interviews, documents, and institutional categories, and coding results were cross-validated by multiple members of the research team to reduce interpretive bias. Furthermore, a visual triangulation map (see Figure 1) was constructed to illustrate the interactions among regulatory institutions (KPI and KPID), media conglomerates, political parties, and editorial decision-makers. This map highlighted key communication bottlenecks and power asymmetries in the regulatory chain, revealing how political content decisions often bypassed regional oversight mechanisms. These relational insights were corroborated through institutional documents, public complaint records, and informant testimonies, thereby strengthening the thematic coherence and depth of the analysis.

Figure 1. Power and communication map among media actors during 2024 election. Source: proceedings by researchers, 2025.

4 Finding and discussion

4.1 Findings on election violations

KPI operates a 24/7 broadcast content supervision system, yet comprehensive monitoring is primarily limited to radio and television stations located in Jakarta due to resource constraints. Monitoring is conducted on a randomized basis, with specific months and times chosen to optimize oversight within available resources. To address these limitations, regional broadcast institutions are occasionally required to submit recordings for KPI’s review, allowing the organization to maintain oversight flexibility and improve resource efficiency.

KPI monitoring team, including monitoring assistants and support staff, who filter broadcast materials for potential violations. Findings indicating possible breaches are documented in the iTem/Indikasi Temuan (Finding Indication) report, which is then verified by key commissioners: Coordinator of Broadcast Content and Content Commissioner. Verified reports advance to a plenary session with all KPID commissioners.

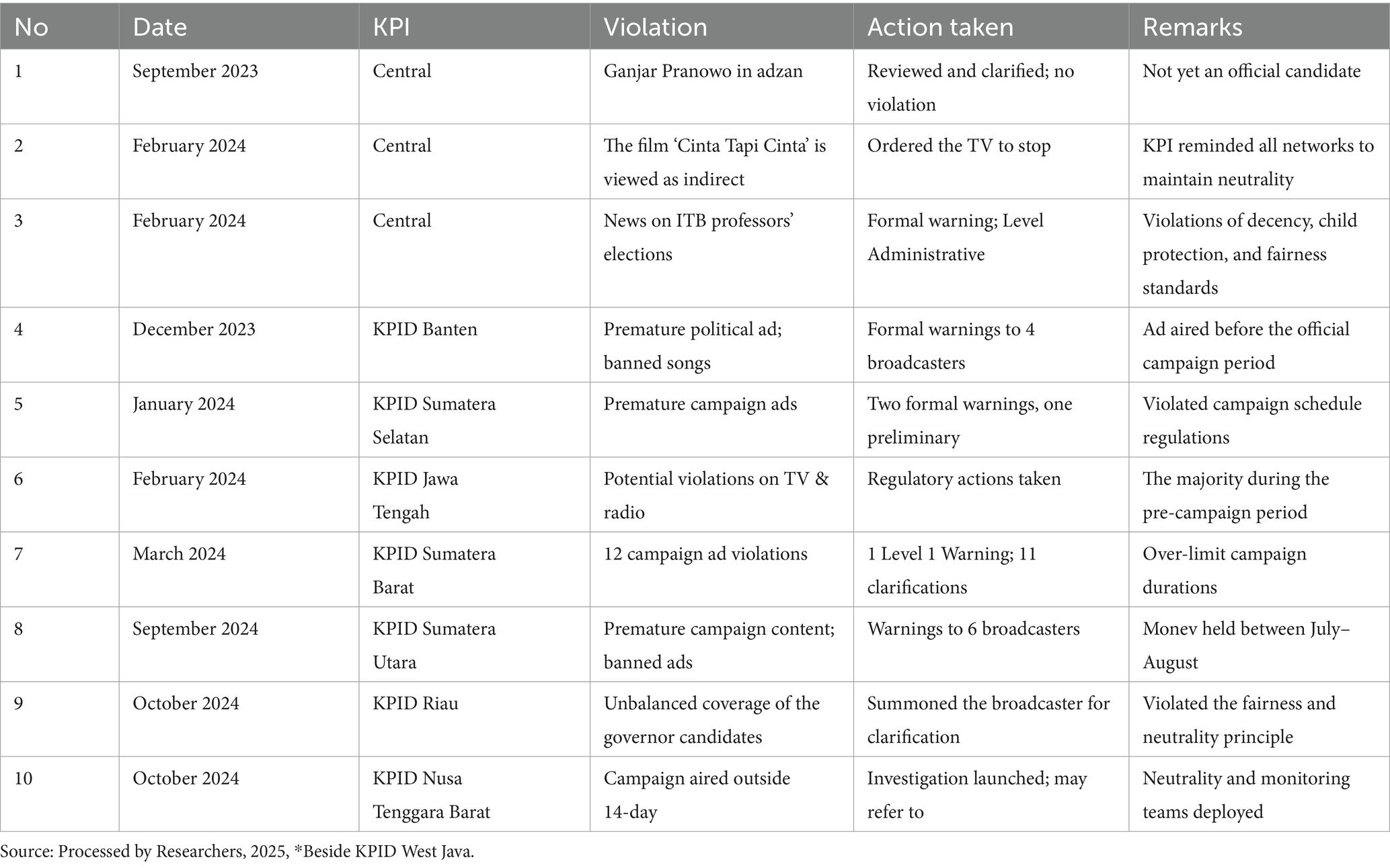

In initial plenary sessions, commissioners review the reported violations against the P3SPS standards. If the findings suggest a significant breach, further actions are taken, such as convening an RDPA/Rapat Dengar Pendapat Ahli (Expert Hearing) or requesting clarification from the broadcast entity to provide additional context and validate the disputed content. Once sufficient evidence is gathered, a second plenary meeting is conducted to determine the final decision. The outcome is formally recorded in a Decision Letter (SK/Surat Keputusan), which may include sanctions such as administrative reprimands or formal written warnings. Ubaidillah, Chairperson of the Central KPI, outlined the following violations related to election broadcasting:

The Central Broadcasting Commission (KPI Pusat) ordered one of the national television stations to immediately cease the broadcast of the film Cinta Tapi Cinta on February 14, 2024, as it was perceived as indirect campaigning for one of the presidential candidate pairs. This action was part of KPI’s broader effort to preserve neutrality in media content on the official voting day of the Indonesian General Election. Ubaidillah reminded all broadcasters to refrain from airing any material that could favor specific candidates, parties, or legislative contenders. He reaffirmed that such partisanship violates the 2012 Broadcasting Code of Conduct and Program Standards (P3SPS), which prohibits using broadcast platforms to advance personal or group interests. KPI also urged other networks under the MNC Group not to air similar content, underscoring broadcasters’ legal and ethical responsibility to maintain impartiality during the democratic process.

On February 13, 2024, the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) issued a formal written warning to one of the national television stations concerning their news program segment aired on February 6, which reported on a public statement by ITB professors calling for fair and honest elections. KPI concluded that the segment violated multiple provisions in the Broadcasting Code of Conduct and Program Standards (P3 and SPS), including norms on public decency, protection of children and adolescents, cultural sensitivity, and journalistic integrity. As a result, KPI imposed a Level 1 Administrative Sanction, reaffirming the broadcaster’s obligation to uphold ethical standards and public responsibility, especially during the election season.

Prior to those two occasions, in September 2023, the appearance of presidential candidate Ganjar Pranowo in a televised call-to-prayer (adzan) segment sparked considerable public noise and speculation over potential violations of broadcasting ethics. KPI responded by initiating a content review and formally requesting clarification from the broadcaster regarding the rationale and timing of the segment. Critics, including public figures like Rocky Gerung and PSI politician Ade Armando, expressed concern over the potential misuse of public frequencies to favor a particular candidate, especially during a politically sensitive period. Following the review, KPI concluded that the broadcast did not breach the Broadcasting Code of Conduct and Program Standards (P3SPS). According to KPI Coordinator for Content Supervision Tulus Santoso, Ganjar was not officially registered as an election participant at the time, and the segment contained no explicit or implied campaign message. KPI’s findings were also aligned with the view of the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu), which saw no grounds for electoral sanctions. While the incident stirred significant public discourse, it was ultimately not proven to violate any broadcasting or electoral regulations. In addition to the Central KPI, election-related violations were also documented by regional KPI (KPID) offices, as outlined chronologically below.

In December 2023, the Regional Broadcasting Commission of Banten (KPID Banten) issued a formal warning to a local broadcasting institution for airing a political campaign advertisement on behalf of a legislative candidate ahead of the legally sanctioned campaign period. Commissioner Efi Afifi confirmed that the ad explicitly urged the public to vote, mentioned the candidate’s name and party affiliation, and included the candidate’s ballot number. Such content violated the General Elections Commission (KPU) regulations, which stipulate that political advertising is only permitted from January 2024. In addition to this case, KPID Banten issued official warnings to three other broadcasting institutions for separate violations involving the unauthorized airing of songs previously prohibited by the national broadcasting commission, KPI. All four broadcasters were summoned for clarification and underwent review during a plenary session, which resulted in the issuance of first-level warnings.

In January 2024, the Regional Broadcasting Commission of South Sumatra (KPID Sumatera Selatan) issued formal warnings to three media outlets for violations related to premature political campaign advertising. According to Chairperson Herfriady, two of the broadcasters received written reprimands, while one was issued a preliminary notice. The infractions occurred in December 2023, a time when campaign advertisements were not yet permitted under the official timeline set by the General Elections Commission. The early airing of such content was deemed a violation of national regulations, which require media institutions to maintain neutrality and adhere to established campaign periods. KPID Sumsel’s enforcement actions were taken to uphold the legal provisions outlined in the Broadcasting Code of Conduct and the Broadcast Program Standards, both of which explicitly prohibit campaign activities outside the designated timeframe. During a press briefing on January 22, Herfriady emphasized that these broadcasters had engaged in premature promotional content, commonly referred to as “curi start.”

In February 2024, the Central Java Regional Broadcasting Commission (KPID Jateng) reported 122 potential broadcasting violations related to the 2024 General Election. These were discovered through monitoring activities targeting 32 local and SSJ television stations and 30 radio broadcasters across the province. According to Broadcast Content Commissioner Ari Yusmindarsih, 112 of the violations involved television broadcasts and 10 involved radio. Infractions included unauthorized use of public frequencies for partisan purposes, premature campaign ads, and excessive campaign airtime. Notably, no violations were recorded during the cooling-off period or on election day, February 14. Broadcasting Policy Commissioner Anas Syahirul Alim affirmed that KPID Jateng responded to the violations with appropriate regulatory action, emphasizing the need for improved compliance among broadcasters. He reminded all license holders that broadcast frequencies are public resources and must be used to serve the public interest, particularly in maintaining fairness and balance during election coverage.

In March 2024, the West Sumatra Regional Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPID Sumatera Barat) reported 12 suspected violations related to election campaign broadcasting during the official campaign period ahead of the 2024 general election. These violations were uncovered through systematic monitoring of political advertisements on television and radio, concluding on February 10, 2024. During a press conference on March 5, chaired by KPID Sumbar Chairperson Robert Cenedy, it was revealed that one local broadcaster received a Level 1 Warning, while the other 11 cases were addressed through clarification meetings with the respective media institutions. Robert stated that the majority of these violations stemmed from broadcasters exceeding the legally allowed duration and frequency of campaign ads, in breach of regulations issued by the General Elections Commission (KPU). However, after the commission intervened, all the implicated broadcasters in West Sumatra took corrective measures, either removing or revising the content in question.

In September 2024, the Regional Indonesian Broadcasting Commission of North Sumatra (KPID Sumatera Utara) issued formal warnings to five radio stations and one private television channel for airing unauthorized health and medicinal advertisements, while another television station was reprimanded for broadcasting political campaign content for a regent candidate before the official campaign period. These actions followed findings from a monitoring and evaluation (Monev) session conducted between July and August 2024, with the session held at the KPID Sumut office in Medan on September 26. The violations were primarily related to premature campaign broadcasts and failure to comply with regulations from the General Elections Commission (KPU) and KPI’s circulars, which specify that campaign ads may only air after November 10 and are limited to 10 slots per candidate per day. Commissioner Anggia emphasized that all broadcasting institutions must adhere strictly to the principles of neutrality and fairness in political reporting and advertising. Any media outlet found to favor specific parties or candidates risks further sanctions.

In October 2024, the Regional Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPID) of Riau summoned a local radio station to address alleged violations in its coverage of the 2024 Riau Gubernatorial Election. The commission’s monitoring team found that the station aired news segments focusing exclusively on Candidate Pairs No. 1 and No. 2, while omitting any mention of Candidate Pair No. 3. This selective reporting was deemed disproportionate and partial, contradicting the requirement for equitable coverage in election broadcasts. Ahmad Royhan Qodri, Head of the Content Supervision Division at KPID Riau, stressed that such an imbalance violates Circular Letter No. 6 of 2024, which mandates all broadcasters to ensure fairness, balance, and neutrality during local elections.

In October 2024, the West Nusa Tenggara Broadcasting Commission (KPID NTB) received a public complaint alleging that a local broadcaster aired political campaign content outside the legally permitted 14-day campaign window. Commissioner Yusron Saudi confirmed initial findings of a likely violation and stated that KPID NTB had secured evidence and begun a formal investigation. If confirmed, the broadcaster will face sanctions in line with regulatory procedures, and the case may be referred to the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu), in coordination with the KPU. While withholding details of the broadcaster, candidate, and content, Yusron reaffirmed KPID NTB’s neutrality and noted that monitoring teams were deployed throughout the province to ensure compliance. These events are presented in Table 1.

4.2 KPID West Java: highest number of violations

In West Java, Adiyana Slamet, Chairperson of the West Java Regional Broadcasting Commission (KPID Jawa Barat), confirmed that out of 108 identified indications of electoral broadcasting violations, only 32 were verified as actual infractions after thorough internal deliberations in the Commission’s Plenary Session. These confirmed violations were subsequently addressed through official warnings and sanctions, with only nine cases escalating to the level of formal written warnings. For infractions involving network-affiliated (SSJ) content beyond regional jurisdiction, KPID West Java submitted recommendations to the Central KPI for appropriate handling. The Commission maintained continuous monitoring of broadcast content from 2023 through to election day on February 14, 2024, up to 3:00 p.m.

Most of the confirmed violations were attributed to imbalanced political coverage and breaches of neutrality, often favoring the political messaging of media owners or affiliated political parties. These findings highlight ongoing structural weaknesses in upholding fairness and neutrality in Indonesian electoral broadcasting, particularly due to the limited jurisdiction of regional commissions when facing violations by national networks.

Between May 2023 and February 2024, various significant breaches of campaign broadcasting rules were documented in West Java, especially concerning the misuse of television airtime for political agendas.

On May 20, 2023, two national television channels aired the Prosperous Justice Party’s anniversary, violating Article 46(10) of Law No. 32/2002, which prohibits the sale of broadcast time for non-commercial content. This situation was followed by speeches from Gerindra’s Prabowo Subianto on July 9 and 16, the Democratic Party on July 14, and the Nasdem Party’s “Apel Siaga Perubahan” on July 16, all aired across multiple national channels. Sanctions in the form of a Recommendation for Clarification Request were issued to the relevant broadcasters.

No violations were observed in November 2023, likely due to the campaign’s late start on November 28. However, by December, nine breaches were recorded, including Ganjar Pranowo’s appearance in call-to-prayer segments and excessive airtime for DPR candidate Hj. Siti Maryanti.

In January 2024, violations related to Presidential and Legislative election campaigns were recorded consistently from January 16 to January 28, all occurring on national and local television stations in West Java. A total of four distinct violations were documented:

1. A single broadcast of a political campaign advertisement for the National Mandate Party (PAN), candidate No. 12, aired within an SSJ television program (in one national television channel).

2. Covert political advertising embedded within the “Gedor Gembira Indonesia” program aired six times (on one local television channel).

3. A campaign video clip for Presidential and Vice Presidential candidates No. 02, Prabowo-Gibran, aired once as an advertisement (on one local television channel).

4. An unbalanced broadcast of a live event titled “Saatnya Menang untuk Perubahan” for the Nasdem Party aired once (on one national television channel).

The sanctions issued for these television’s violations were classified as Level 1 Warnings for content No.3, and Recommendation Level 1 Warnings for Nos. 1, 2, and 4.

In February 2024, two DPR candidates, Djoni Toat Muljadi and Badarrudin, aired campaign ads across several days, adding to a total of six infractions. Across these months, KPID West Java issued a mix of Level 1 Warnings and Recommendation Level 1 Warnings, reflecting the persistent difficulty of regulating political broadcasting within a fragmented and ownership-influenced media landscape.

A producer from a national television station in Bandung disclosed that commercial and operational pressures often override compliance with broadcasting regulations. Although KPI West Java routinely provides guidance, local station managers admitted that directives from their Jakarta head office (particularly to meet annual advertising and event revenue targets) frequently took precedence. This pressure was evident during election periods, when stations knowingly aired non-compliant political advertisements from parties like PSI and Perindo to secure revenue, despite the risk of violating regulations.

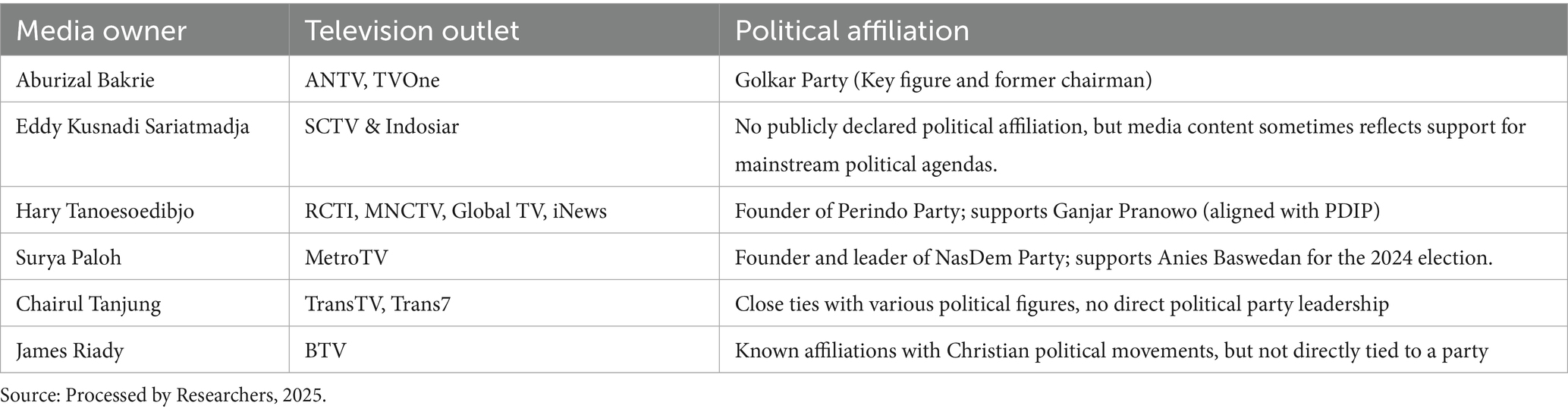

Economic strain in the broadcasting industry, worsened by a 70% drop in advertising revenue during the COVID-19 pandemic, has led broadcasters to depend on fewer, budget-constrained advertisers. With many advertisers shifting to digital platforms such as Instagram and government campaigns moving to local government social media, broadcasters were further pushed to accept high-risk content, including political ads, adult product promotions, and shows that test decency standards. The situation is exacerbated by the structure of the National Network System (SSJ), where regional stations relay content directly from Jakarta without editorial control. Local offices lack the authority to preview or modify this centrally produced content, which is delivered straight to their Master Control Rooms (MCR) for broadcast. This system has led to regulatory breaches that triggered formal warnings from KPI West Java. While SSJ relays reduce operational costs and help stations stay afloat, they also reveal how media ownership, political affiliations, and centralized content pipelines contribute to persistent violations of broadcasting ethics and standards. The following provides an overview of the 12 major conglomerates dominating over 97% of television viewership, as discussed in the Introduction (Table 2).

Interviews with station managers, news coordinators, and program directors in Bandung revealed that national radio networks frequently aired content flagged for violating P3SPS regulations during the 2024 election cycle as part of a broader strategy to retain their market share. These stations acknowledged that political programming was increasingly influenced by what garnered attention on social media, including viral campaign jingles, influencer-endorsed candidates, and emotionally charged slogans. According to them, responding to market trends (rather than upholding neutrality) was seen as essential to remaining competitive in an election year marked by intense political spectacle.

Many broadcasters admitted that, as part of national networks, their editorial decisions were not locally determined but followed directives from Jakarta headquarters, which were often affiliated with political parties or coalitions. This top-down content management led to a uniformity of political messaging across regions, minimizing the ability of local stations to filter or balance political narratives. The local staff expressed concern that this centralization diluted journalistic integrity and reduced space for critical or pluralistic discourse, especially when their parent companies openly aligned with specific candidates.

Frustration also arose over perceived inconsistencies in KPI West Java’s enforcement practices. Local broadcasters argued that while they were penalized for airing partisan content, the central stations that produced and distributed the duplicate content often went unchecked. They suggested that KPI should focus not only on local station compliance but also on systemic violations stemming from centralized production in Jakarta. A more effective regulatory approach would involve regular publication of pre-election content guidelines tailored for all network members, along with transparent scrutiny of headquarters-driven editorial policies.

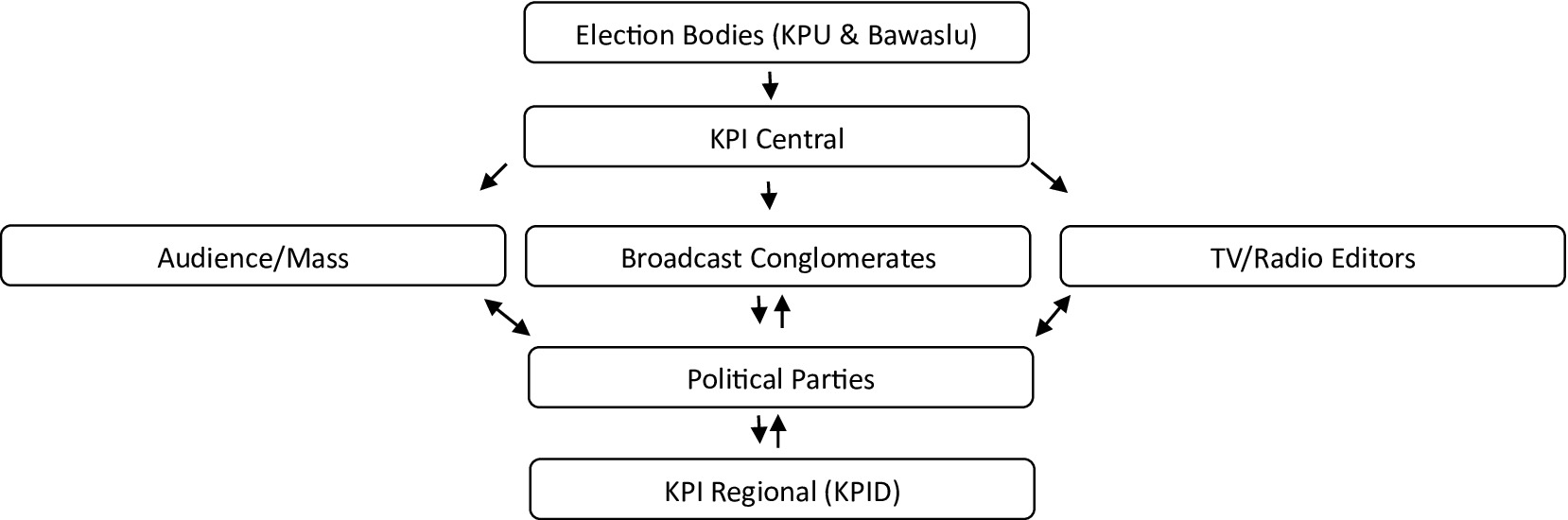

To better understand the institutional dynamics and communication pathways that influence broadcasting oversight during the 2024 election, a visual mapping of interrelated actors is presented below. Figure 2 outlines the hierarchical flow of authority, reporting structures, and information exchange among central and regional regulatory bodies, media institutions, political entities, and the public:.

Figure 2. Flow of hierarchical authority among KPI central and regional and stakeholder. Source: proceedings by researchers, 2025.

Overall, from finding part, broadcasters saw themselves caught between commercial imperatives, central office political affiliations, and inconsistent regulatory oversight, leaving little room to assert editorial independence or prioritize public interest over partisan advantage.

In the discussion part later, these are four approaches. First, from the gatekeeping perspective, the role of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) during the 2024 election cycle aligns with Kurt Lewin’s foundational model. KPI and KPID served as institutional gatekeepers, filtering and responding to political content broadcast across national and local television. However, this regulatory function was consistently challenged by structural limitations. Many regional broadcasters admitted that compliance often came second to commercial directives from their Jakarta headquarters, particularly during peak political seasons. In practice, the National Network System (SSJ) hindered regional KPIs from exercising editorial control over centrally relayed content. KPI’s gatekeeping role became largely reactive, issuing post-airing warnings rather than preventing infractions. This finding echoes the concerns raised by Voinea (2025), and also by Syah et al. (2025), who highlighted the regulatory paralysis caused by digital fragmentation, particularly in environments overloaded with unchecked information flows and politicized media activity. Furthermore, KPI’s reactive posture indicates a shift from normative gatekeeping to procedural monitoring, where enforcement is often delayed and symbolic rather than preventive and structural.

Second, from the perspective of media power, the findings confirm the enduring influence of television in shaping political narratives. As argued by Fiske (2011) and Spilker et al. (2020), television remains central to public communication due to its broad reach and immersive audiovisual format. During the 2024 election, this medium was used not only to inform but to influence. Financial pressures, especially following the advertising downturn exacerbated by the pandemic, forced many broadcasters to prioritize revenue over compliance. Political actors exploited this vulnerability by securing prominent airtime for content that subtly or explicitly promoted their campaigns. In some cases, stations knowingly aired content that violated the Broadcasting Code of Conduct, suggesting that television continues to function as both an economic and ideological battlefield in electoral politics. This political-economic nexus mirrors recent findings by Putri et al. (2024), who showed how agenda direction and promotional bias in televised electoral programs were often shaped more by editorial framing than by democratic balance. The asymmetry of power between political advertisers, media owners, and regulators further entrenches this condition, making it difficult for KPI to exercise independent judgment in the face of politically backed commercial imperatives.

Third, when analyzed through media ideology theory, the data illustrate how unspoken political and economic loyalties often inform broadcast decisions. Following the explanation of Hall (1980) and Alamsyah (2020), media do not merely relay facts but actively produce meaning within existing power structures. The repeated appearance of specific candidates in emotionally charged or religious contexts, without balanced representation, revealed how ideology is embedded in routine programming. Rather than overt bias, these patterns reflect deeper institutional alignments with particular political parties or figures, especially in media owned or influenced by political interests. Such implicit framing makes regulatory enforcement difficult, as violations often fall within gray zones not covered by existing rules, a condition also noted by Heryanto et al. (2024) in their analysis of hoax-laden political content that exploited emotional cues and selective exposure to reinforce partisan narratives. In this sense, ideology is not always visible through explicit endorsements. However, it often emerges through symbolic repetition, representational asymmetries, and emotional scripting embedded in program formats such as talk shows, religious features, or infotainment.

Fourth, about agenda setting, the findings reflect how broadcasters and political actors collaborated, directly or indirectly, to shape public attention. Based on McCombs and Shaw’s model, what appeared on television determined what the public perceived as necessary. Through persistent messaging, symbolic framing, and selective reporting, media coverage elevated the visibility of particular parties and narratives. This was especially evident in the unequal airing of campaign materials, early promotional content, and event coverage skewed toward specific candidates. Mulyana and Wijayanti's (2024) dimensions of representation, persistence, and persuasion are visible in the data, and KPI’s task was to counterbalance this agenda domination. However, the asymmetrical power dynamics between regulators, media owners, and political advertisers complicated this role, limiting KPI’s ability to ensure fairness in the public information space fully. While some regulatory interventions were made in response to public complaints or monitoring reports, these efforts often came too late to counter the effects of prolonged exposure, allowing certain narratives to dominate the public agenda unchallenged.

In sum, when the results are viewed through the lens of the four primary theoretical frameworks (Gatekeeping, Mass Media Power, Media Ideology, and Agenda Setting), they reveal specific mechanisms by which structural, commercial, and ideological forces shaped Indonesia’s broadcast media during the 2023–2024 election cycle. Gatekeeping theory highlights KPI’s reactive and structurally limited position in controlling political content. Media power theory illustrates how commercial dependency and editorial bias allowed political influence to pervade broadcasting. Media ideology explains the normalization of partisan narratives through implicit, coded messages shaped by ownership and institutional alignment. Finally, agenda-setting theory demonstrates how repetitive exposure, selective framing, and imbalanced representation coalesced to shape electoral discourse in favor of dominant actors. These combined forces created a political information landscape where regulation was both necessary and insufficient, constrained by systemic inequities that exceeded the formal reach of broadcasting law.

KPI and KPID, as national and regional regulatory bodies, consistently perform a gatekeeping function as conceptualized by Lewin (1947) and expanded by Shoemaker and Vos (2009), filtering which political content proceeds to the public and which is blocked. Their issuance of formal warnings (SK) reflects both legal and educational dimensions of regulation (Baldwin et al., 2012), encouraging ethical broadcasting behavior and public accountability (McQuail, 2005). The increasing number of SKs also aligns with McQuail’s emphasis on public participation as a regulatory force and indicates growing civic awareness in reporting violations. These mechanisms demonstrate that KPI and KPID not only enforce existing standards but also actively construct the boundaries of political communication, as gatekeepers should.

However, the fluctuation in P3SPS violations, particularly the spike in 2024, raises concerns over the deterrent effect of such sanctions. The inability to entirely suppress repeat violations may be linked to insufficient enforcement power or the mounting pressures of a political year marked by three major democratic events. As Tapsell (2017) and Jurriëns (2020) point out, media ownership entanglements and oligarchic influence in Indonesia severely constrain editorial independence and regulatory effectiveness, particularly when broadcasting platforms are used for political and business gain. The KPI and KPID role as gatekeepers is thus contested terrain, challenged by media conglomerates that act as both message producers and political actors.

From the perspective of mass media power, television remains the most influential medium during elections due to its audiovisual impact and cultural familiarity (Fiske, 2011; Spilker et al., 2020). Its dominance in shaping public perception, particularly among youth and rural voters, makes it a powerful political tool. KPI and KPID’s role is to ensure this power is not weaponized for partisan gain, especially under the pressure of advertising competition and declining revenues. Repeated violations—such as airing child-inappropriate content or political promotions outside campaign periods—signal a trade-off between commercial survival and regulatory compliance, as noted by Yudiawan and Ariestu (2023).

This tension is further exacerbated by media ideology, which subtly shapes reality to align with vested interests. As Hall (1980) and Alamsyah (2020) argue, media do not merely reflect truth but manufacture consent by embedding dominant political values. This was especially evident during the 2024 elections, where broadcast media selectively promoted specific candidates or omitted others. While KPI and KPID intervened through SK issuance, they operated within a landscape of ideological asymmetry, where neutrality was often compromised by editorial instructions from politically affiliated media owners (Nugroho et al., 2012; Supriadi et al., 2020).

In terms of agenda setting, political content on television did not merely inform but structured public priorities (McCombs and Shaw, 1972). Political parties and candidates strategically used media to highlight their platforms, while broadcasters chose which narratives to elevate or silence. Mulyana and Wijayanti (2024) stress the three key dimensions: representation, persistence, and persuasion. The recurrence of political advertisements, curated coverage, and candidate-focused programming all shaped what the audience thought about, even if not how they thought. In this dynamic, KPI and KPID sought to moderate the dominance of singular political agendas, but enforcement remained limited by organizational reach, particularly in SSJ networks beyond regional control (Alim et al., 2020; Susetyo et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the exposure of youth to political content has long-term implications. As Strasburger (2005) and Gaultney et al. (2022) observe, repeated exposure to politicized or sexually suggestive content can skew young viewers’ beliefs and social behaviors. Media literacy deficits among youth further exacerbate this, making them vulnerable to distorted information and emotional manipulation. Cangara’s sensory-driven media model, Bandura’s social learning theory (Bandura, 1991), and Gerbner’s cultivation theory (Shrum, 2017) help explain how prolonged exposure to glamorized or normalized political and sexual content can lead to behavioral imitation and distorted social realities. In South Asia, demonstrates how government public relations and bureaucratic influence shape broadcast regulation in India and Pakistan, limiting the independence of regulatory bodies and skewing content toward state-aligned narratives. These examples reinforce the importance of vigilant enforcement of neutrality standards during election cycles. Cross-national comparisons reinforce this dynamic. In Latin America, media reform often occurs under tension between civic society and populist governance, revealing how regulatory institutions struggle to moderate partisan content in the face of elite media capture (Waisbord, 2011). In India, transformations in journalism—especially in periods marked by increased political control and crisis—highlight how regulatory and editorial fields adapt under pressures that can compromise media neutrality (Belladi, 2025).

A useful lens for understanding Indonesia’s broadcasting landscape is the comparative framework proposed by Hallin and Mancini (2004), who argue that media systems are not autonomous entities but are profoundly shaped by the political systems in which they operate. They identify three models of media and politics, the Polarized Pluralist, Democratic Corporatist, and Liberal, each corresponding to different configurations of political pluralism, journalistic professionalism, and state intervention. While this typology was developed from Western democratic contexts, Indonesia’s hybrid media system increasingly reflects traits aligned with the Polarized Pluralist model, characterized by substantial political parallelism, instrumentalized journalism, weak regulatory autonomy, and significant elite influence over media institutions. This situation is evident in how media conglomerates with political affiliations dominate news agendas, and how regulators such as KPI face constraints when enforcing neutrality during electoral cycles.

Although Indonesia formally adopts a democratic system of governance (marked by direct elections, decentralization, and a multiparty structure), the practical realities of its media regulation reveal underlying tensions between normative ideals and entrenched power structures. The regulatory paralysis observed during the 2024 election underscores how media oversight institutions are often reactive, under-resourced, and politically encumbered. In this context, democratic procedures exist more prominently on paper than in practice, particularly when market forces and partisan interests override the public interest function of the media. As Hallin and Mancini suggest, understanding the embeddedness of media within a country’s political culture is crucial to grasping why regulatory efforts struggle to ensure balanced, ethical broadcasting, especially during high-stakes political contests.

Ultimately, the broadcasting ecosystem is at risk of drifting away from the public service mandate outlined in Article 3 of Law No. 32/2002 (Pemerintah Indonesia, 2002). KPI and KPID are thus entrusted not only with enforcing content standards but also with protecting the democratic and moral fabric of society—a responsibility that intersects with the Press Law No. 40/1999 (Indonesia, R, 1999), the Journalistic Code of Ethics (Dasar et al., 1945), and electoral laws (Negara, 2017; Tedjokusumo et al., 2024). Their task is to balance the commercial logic of broadcasters with the ethical imperative of public communication, especially during elections. To strengthen this role, scholars recommend four actionable reforms. First, legal revision is needed to enhance KPI/KPID’s enforcement authority, particularly in the context of the National Network System (SSJ), where regional commissions often lack control over centrally relayed content. A more precise legal mechanism should empower KPIDs to intervene directly in SSJ transmissions that breach electoral ethics or violate the P3SPS. Second, the transparency of media ownership must be institutionalized through accessible public disclosures to expose potential conflicts of interest and ensure regulatory decisions remain independent.

Third, the establishment of a centralized and publicly accessible database of sanctioned broadcasters and practitioners, including a practitioner blocklist as suggested by Widyatama (2022), could serve both as a deterrent and as a tool for improving long-term compliance. Fourth, in line with growing scholarly concern (Dharmawan, 2018; Fardiah et al., 2020), partnerships with civil society should be strengthened to foster locally produced, diverse content and to expand public engagement and media literacy programs. As disinformation and emotional manipulation increasingly affect youth and rural voters, integrating media literacy into formal education and community initiatives must become a national priority. These long-term strategies, when implemented alongside firm sanctions, are essential to cultivating an informed, participatory, and resilient public. Only through such holistic gatekeeping can KPI and KPID preserve the integrity of political broadcasting in Indonesia’s contested media landscape.

5 Conclusion

This study finds that Indonesia’s broadcasting regulators, KPI and KPID, face severe institutional and structural constraints in enforcing media neutrality and ethical standards during the 2024 general election. Although the regulatory framework is formally robust, its implementation suffers from centralization, limited regional autonomy, and inconsistent sanctions. The National Network System restricts the authority of regional KPIDs, especially in responding to centrally relayed content that may contain biased political messages. Monitoring activities are concentrated in Jakarta, while violations in the provinces are often discovered late or receive only minimal follow-up. This asymmetry, combined with commercial and political pressures, diminishes the regulators’ ability to intervene decisively and uphold fair broadcasting practices. Furthermore, KPI’s responses tend to be procedural rather than strategic, and public complaints or civil society inputs rarely translate into meaningful regulatory impact.

The pattern of violations, ranging from premature campaign ads and symbolic political appearances to selective news coverage, reflects deeper vulnerabilities in Indonesia’s media governance. These are not merely technical breaches but symptomatic of blurred boundaries between journalism, propaganda, and infotainment. Nonetheless, KPI’s use of plenary hearings, expert consultations, and multi-source verification offers a measure of procedural accountability. To improve this role, the study recommends several reforms: expanding KPID’s legal authority, establishing transparent ownership disclosures, developing a national database of sanctioned practitioners, and investing in media literacy initiatives to promote public awareness. Ultimately, strengthening Indonesia’s broadcasting oversight will require not only institutional resilience but also a democratic commitment to safeguard political communication from distortion, especially during elections.

Further research should examine the regulatory landscape across multiple election cycles to assess whether patterns of violations and enforcement evolve or remain structurally embedded. Comparative studies with other transitional democracies in Asia or Latin America could provide context for Indonesia’s regulatory dilemmas, highlighting how different systems balance state authority, media corporatism, and democratic oversight. Additionally, future inquiry should explore public perception and civil society engagement with broadcasting violations to capture bottom-up accountability mechanisms. Lastly, research must expand into digital and cross-platform political content—such as influencer-driven campaigns and OTT broadcasts—which increasingly shape electoral narratives but often fall outside the current regulatory framework, raising urgent questions about KPI’s relevance in a hybrid media environment (**).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study by the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation. MA: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. DP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alamsyah, F. F. (2020). Media representation, ideology, and reconstruction. Al-I’lam. Jurnal Komunikasi-Penyiaran Islam. 3, 4–8. doi: 10.31764/jail.v3i2.2540

Alim, N., Asang, S., and Sciences, P. (2020). Performance of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission’s Oversight Function in South Sulawesi 8, 54–62. Available at: https://share.google/U9lt0AyRHU0vaeJbY

Ambardi, Kuskridho, Parahita, Gilang, Lindawati, Lisa, Sukarno, Adam, and Aprilia, Nella (2014). Mapping Digital Media: Indonesia. Open Society Foundation. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333355791_The_Dynamics_of_Media_Landscape_and_Media_Policy_in_Indonesia (Accessed July 10, 2025).

Aryesta, A. E., and Selmi, S. (2022). Analisis Strategi Komunikasi KPI Menggunakan situational theory of public relation. Jurnal Communio: Jurnal Jurusan Ilmu Komunikasi 11, 76–88. doi: 10.35508/jikom.v11i1.5037

Asih, R. W. (2023). Nielsen: TV viewership grows to 130 million. Bisnis Tekno, 1–3. Available at: https://ejurnal.kampusakademik.co.id/index.php/jssr/article/view/503

Baldwin, R., Cave, M., and Lodge, M. (2012). Understanding regulation: theory, strategy, and practice. doi: 10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199576081.001.0001

Belladi, S. (2025). Transformation of journalism in India and the rise of new practices during emergency and beyond. Cogent Arts Humanit. 12:2498187. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2025.2498187

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 4th Edn. New York: Sage Publications.

Dasar, U., Universal, D., and Asasi, H. (1945). Kode Etik Jurnalistik. Ministry of Internal Affair. 1–5.

Dharmawan, A. (2018). Mengurai Tantangan Dan Solusi Kpid Jawa Timur Untuk Mewujudkan Kualitas Program Siaran Televisi. Diakom: Jurnal Media Dan Komunikasi 1, 24–32. doi: 10.17933/diakom.v1i1.18

Fardiah, D., Darmawan, F., and Rinawati, R. (2020). Media literacy capabilities of broadcast monitoring in regional Indonesian broadcasting commission (KPID) of West Java. Jurnal Komun. 36, 126–142. doi: 10.17576/JKMJC-2020-3604-08

Gaultney, I. B., Sherron, T., and Boden, C. (2022). Political polarization, misinformation, and media literacy. J. media Lit. Educ. 14, 59–81. doi: 10.23860/JMLE-2022-14-1-5

Hallin, D. C., and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, S. (1980). “Encoding/decoding” In: Culture, media, language ed. Willis, P (London: Routledge), 128–138.

Heryanto, G., Zamroni, M., and Astuti, Y. D. (2024). Disinformation unveiled: tracking media hoaxes to build public literacy for Indonesia’s 2024 elections. Stud. Media Commun. 12:28. doi: 10.11114/smc.v12i4.6931

Indonesia, R. (1999). Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 40Presiden, R. I. (1999). Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 40 Tahun 1999 Tentang Pers. Available online at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q (Accessed July 10, 2025).

International Foundation for Electoral Systems/IFES (2024). Elections in Indonesia: 2024 General Elections. Available online at: https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/2024_Elections_FAQ_Final.pdf (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Jurriëns, E. (2020). Citizens and the digital revolution. London: Rowman and Littlefield International.

Khusnul, K. N., and Kushardiyanti, D. (2022). Sensor Penyiaran Televisi Indonesia: Menyoal Muatan Negatif Dalam Konten Siaran Televisi. Media. 6, 1–16. doi: 10.30762/mediakita.v6i1.304

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: channels of group life; social planning and action research. Hum. Relat. doi: 10.1177/001872674700100103

McCombs, M. E., and Shaw, D. L. (1972). The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176–187. doi: 10.1086/267990

Mulyana, N. I., and Wijayanti, Q. N. (2024). Agenda-setting communication theory in K-pop: the role of media on fan motivation, satisfaction, and loyalty. Jurnal Sains Student Res. 2, 1–14.

Muskita, M., Winartha, K. A., Suwirta, I., and Lestari, P. (2023). Implementation of agenda setting theory by radio Republik Indonesia Denpasar: constraints and strategies. J. Commun. Stud. Society 2, 49–56.

Natalia, W. K., and Ajibulloh, A. A. (2023). Polemik Komisi Penyiaran Indonesia (KPI) dalam Pengawasan Media Baru Polemic On Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) in New Media Control. Jurnal Mediakita Jurnal Komunikasi Dan Penyiaran Islam 7, 82–98. doi: 10.30762/mediakita.v7i1.789

Negara, K. S. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 7 Tahun 2017 tentang Pemilihan Umum. Ministry of Internal Affair. (2017).

Nugroho, Y., Putri, D. A., and Laksmi, S. (2012). Mapping the landscape of the media industry in contemporary Indonesia Report Series Oleh Yanuar Nugroho. 1–170. Available at: https://cipg.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/MEDIA-2-Media-Industry-2012.pdf.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Pemerintah Indonesia (2002). Undang-undang nomor 32 tahun 2002 tentang penyiaran. Indonesia: Ministry of Communication & Informatic Republic of Indonesia. 1–34.

Pranoto, E. (2020). Peran KPI Dalam Menjaga Keberagaman. MAGISTRA Law Rev. 1:76. doi: 10.35973/malrev.v1i01.1571

Priyanto, A., and Rahmadante, A. G. (2024). Digital conglomerates and their political behavior: a study on the affiliation of MNC group owner Hary Tanoesoedibjo towards the presidential candidacy of Ganjar Pranowo in the 2024 general election. J. Law, Politic Humanities 4, 208–220. doi: 10.38035/jlph.v4i3.332

Putri, K. Y. S., Fazli, L., Iskandar, I., Gumelar, G., and Pandjaitan, R. H. (2024). Analysis of the agenda setting strategy applied by Narasi TV’S creative team towards the 2024 presidential and vice-presidential election issue through musyawarah program. Stud. Media Commun. 12:115. doi: 10.11114/smc.v12i3.6861

Rayhan, T. M., and Putri, W. Y. (2020). Framing analysis of RCTI’S iNews Siang segment “Pilihan Indonesia 2019.”. J. Creat. Commun. 2, 1–20. doi: 10.33376/is.v2i2.537

Razak, R., Pawito, P., Utari, P., and Nurhaeni, I. D. A. (2025). Balancing government influence and editorial independence: TVRI’S role in shaping media agendas. J. Soc. Polit. Sci. 8, 73–85.

Salsabila, P. Z., and Pratomo, Y. (2020). Ministry of Communication and Information Technology of the Republic of Indonesia implies analog TV service providers immediately migrate to digital. Available at: https://redfame.com/journal/index.php/smc/article/download/6861/6579#:~:text=Furthermore%2C%20the%20Ministry%20of%20Communication,Salsabila%20&%20Pratomo%2C%202020.

Sapitri, H., and Nurafifah, N. L. (2020). Private television media and political in Presindential election 2019 from the agenda setting of. Perspective 24, 3–10. doi: 10.33299/jpkop.24.2.3024

Shrum, L. J. (2017). Cultivation theory: Effects and underlying processes. Int. Encyclopedia Media Effects, 1–12. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0040

Siddiq, M., and Hamidi, J. (2015). Komunikasi Visual Iklan Layanan Masyarakat Dana Bos Sebagai Bahan Belajar. Jurnal Teknodik, 19, 147–160. doi: 10.32550/teknodik.v19i2.156

Siddiq, M., Salama, H., and Khatib, A. J. (2020). Manfaat Teknologi Informasi Dan Komunikasi. Dalam Metode Bercerita. Jurnal Teknodik. 24:131. doi: 10.32550/teknodik.v24i2.496

Sjuchro, D. W., Fitro, R. M., Amdan, N. S., Yusanto, Y., and Khoerunnisa, L. (2023). Implementation of the analog switch off towards digital broadcast Jawa Pos. ProTVF 7, 82–96. doi: 10.24198/ptvf.v7i1.42012

Spilker, H. S., Ask, K., and Hansen, M. (2020). The new practices and infrastructures of participation: how the popularity of twitch.Tv challenges old and new ideas about television viewing. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 3–15. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1529193

Strasburger, V. C. (2005). Adolescents, sex, and the media: Ooooo, baby, baby-a Q & A. Adolescent Med. Clin. 16, 269–288. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2005.02.009

Supriadi, Y., Drajat, M. S., and Saleh, N. L. (2020). The role of the West Java Indonesian broadcasting commission (KPID) in preventing citizen panic related to news and information regarding Covid-19. Mediator: Jurnal Komunikasi 13, 167–177. doi: 10.29313/mediator.v13i2.6573

Susetyo, S., Ikram, I., Mulyaningsih, H., Raidar, U., Benjamin, B., and Ratnasari, Y. (2019). Peran Komisi Penyiaran Daerah (Kpid) Provinsi Lampung Dalam Pengawasan Lembaga Penyiaran Di Provinsi Lampung. SOSIOLOGI: Jurnal Ilmiah Kajian Ilmu Sosial Dan Budaya 21, 97–109. doi: 10.23960/sosiologi.v21i2.40

Syah, R. F., Ekawati, E., Azanda, S. H., Syafarani, T. R., Ayunda, W. A., Zulkifli, Y., et al. (2025). Hoax and election: the role of social media and challenges for Indonesian government policy. Stud. Media Commun. doi: 10.11114/smc.v13i2.7486

Tapsell, R. (2017). Media power in Indonesia: Oligarchs, citizens and the digital revolution. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Tedjokusumo, D., Siswanto, C. A., and Dewantara, Y. P. (2024). Dirty voice: revealing the veil of black campaigns in the world of politics in the 2024 election. IHSA Institute (Natural Resources Law Institute) 13, 1–2.

Voinea, D. V. (2025). Reconceptualizing gatekeeping in the age of artificial intelligence: A theoretical exploration of artificial intelligence-driven news curation and automated journalism. J. Med. 6:68. doi: 10.3390/journalmedia6020068

Waisbord, S. (2011). Between support and confrontation: civic society, media reform, and populism in Latin America. Commun. Culture Critique 4, 97–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-9137.2010.01094.x

Widyatama, R. (2022). The Examination of Sanctions on Violation of the Broadcasting Code of Conduct to Build a Healthy and Sustainable Broadcasting Industry in Indonesia 5, 146–153.

Wilson, I. (2024). More competition, less opposition: Indonesia’s 2024 regional elections. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Available online at: https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2024-97-more-competition-less-opposition-indonesias-2024-regional-elections-by-ian-wilson/ (Accessed August 12, 2025).

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. 6th Edn. London: Sage Publications.

Yudiawan, I. D. G. H., and Ariestu, I. P. D. (2023). Juridical Review of Indonesia Broadcasting Commission Supervision on Broadcasting Services in Indonesia. doi: 10.4108/eai.1-6-2023.2341412

Zuhri, S. (2021). Peran dan Fungsi Penyiaran Menurut Undang-Undang Penyiaran Tahun 2002 dan Perkembangannya. Jurnal Penelitian Dan Pengembangan Sains Dan Humaniora 5, 295–303.

Keywords: broadcast regulation, election coverage, media bias, political communication, Indonesia 2024 general election

Citation: Sulistijanto AB, Abdurrahman MS and Putra DKS (2025) Broadcasting in the shadow of power: regulatory challenges and political violations during Indonesia’s 2024 election. Front. Commun. 10:1682232. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1682232

Edited by:

Temple Uwalaka, University of Canberra, AustraliaReviewed by:

Puji Santoso, Muhammadiyah University of Sumatera Utara, IndonesiaTodani Nodoba, University of Venda, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Sulistijanto, Abdurrahman and Putra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman, c3VmeWFuZGlnaXRhbHByQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; bXVoYW1tYWRzdWZ5YW5AdGVsa29tdW5pdmVyc2l0eS5hYy5pZA==

Andi Budi Sulistijanto1

Andi Budi Sulistijanto1 Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman

Muhammad Sufyan Abdurrahman Dedi Kurnia Syah Putra

Dedi Kurnia Syah Putra