- Management Department, BINUS Business School Doctor of Research in Management, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, Indonesia

Indonesia’s healthcare sector is growing rapidly and facing increasingly fierce competition from new players and disruptive trends. In this dynamic environment, primary clinics must strengthen partnerships with stakeholders to build a foundation for resilience and sustainable growth. This study examines the influence of partnership capacity and collaborative leadership on stakeholder partnerships and analyzes the moderating role of a dynamic health ecosystem in the context of primary clinics in Indonesia. Using survey data collected from 370 clinic leaders, this study applies partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS (version 4.1.1.4) to test the research hypotheses. The results indicate that partnership capacity and collaborative leaders have a significant positive influence on stakeholder partnerships, while a dynamic health ecosystem significantly weakens this relationship. The research model explains 64% of the variance (R2 = 0.64) in stakeholder partnerships, demonstrating strong explanatory power consistent with previous studies in health and management. These findings highlight the strategic importance of leaders adopting a collaborative leadership style to complement institutional partnership capacity. In practice, partnership capacity provides the structural foundation for collaboration, while collaborative leadership transforms trust, communication, and adaptability into effective stakeholder engagement. Together, these factors strengthen clinics’ ability to navigate uncertainty in Indonesia’s dynamic healthcare ecosystem.

1 Introduction

One of the pressing challenges in developing primary clinic services in Indonesia is the limited and uneven distribution of health workers. According to the 2023 Indonesian Health Profile, the number of medical personnel is still insufficient, comprising 183,694 doctors (8.8%), 1,317,589 health workers (63.4%), and 576,190 health support personnel (27.7%). The majority of these health workers are concentrated in the Java-Bali region, which accounts for approximately 60.8% of the total number of doctors in Indonesia (111,686 people). Specifically, West Java has 27,091 doctors, East Java has 23,047 doctors, and DKI Jakarta has 22,724 doctors. Together, these regions account for 65.2% of the total number of doctors nationwide and represent 39.7% of the overall medical workforce. These numbers illustrate the uneven distribution of medical personnel across different regions of Indonesia. On the other hand, remote provinces such as Papua Pegunungan (235 doctors) and Papua Selatan (308 doctors) face significant shortages of doctors. This uneven distribution shows the disparity in health resource capacity (shortages in some regions and surplus in others), which challenges the competitiveness of health services in Indonesia.

In addition to workforce distribution, the ownership structure of clinics presents another challenge. Primary clinics dominate the healthcare landscape in Indonesia, with nearly 98% owned by local, small, and medium-sized businesses. This scenario highlights the importance of establishing sustainable partnerships with corporate stakeholders (e.g., policy and collaboration) to enhance organizational capacity. As emphasized by Lagarde and Palmer (2018), the sustainability of clinics depends on their ability to form strategic partnerships with potential partners. This effort aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically the SDG 3 (ensuring healthy lives) and SDG 17 (building partnerships for sustainable development), which underscore the importance of multi-stakeholder collaboration in achieving equitable, high-quality, and inclusive health services. These stakeholders include patient and corporate clients, healthcare providers, investors, insurance providers, medical distributors, healthcare product suppliers, regulators, and international organizations, such as the WHO and CDC (Secundo et al., 2019).

Given that public health sector funding in Indonesia is relatively low compared to other countries in Southeast Asia, small and medium-sized primary clinics owned by local businesses face significant business and managerial challenges. Capacity building for partnerships is a crucial strategy for improving competitiveness and sustainability (Goodman et al., 2024). Effective partnerships, particularly in areas such as financing, distribution, and human resource management, can significantly strengthen clinic operations (Loban et al., 2021). As emphasized by Padilha et al. (2018), healthcare management relies on collaboration with individual and institutional stakeholders, underscoring the importance of leadership and human resource capacity in enhancing organizational performance.

Recent research suggests that collaborative leadership plays a vital role in fostering trust and maintaining partnerships. A study conducted by Ang’ana and Ongeti (2023) identified several characteristics of collaborative leaders, including the ability to gain trust, create shared value, maintain open communication, and empower team members. Such leaders foster inclusivity and participatory governance practices, thereby increasing trust both within and outside the organization (Pillai, 2021). Through multi-stakeholder collaboration, they can overcome complex challenges, such as chronic disease management and health cost constraints, by aligning the interests of various parties (Charernnit et al., 2021). Essentially, collaborative leadership plays a role in building internal trust (employees and teams within the clinic) and external trust (patients, regulators, and corporate partners), which together form the foundation for successful partnerships (Nonet et al., 2022).

An effective collaborative leader can optimize the use of limited resources by adjusting workforce capacity to the clinic’s organizational goals, thereby improving service quality (Kumar, 2022). Training and technological adaptation further support these leaders in building strategic partnerships (Bornman and Louw, 2023). Although collaborative leadership has garnered global attention, empirical research on small- and medium-sized primary clinics in Indonesia remains limited. Few studies have empirically examined how leadership behavior, partnership capacity, and health environment dynamics interact to influence the success of partnerships.

To address this gap, this study adopts the resource-based theory (RBT) perspective, which posits that human skills, expertise, and knowledge are essential organizational resources for achieving a sustainable competitive advantage (Abbas et al., 2022). Partnership capacity, as a unique organizational resource, creates value through trust, communication, and mutual participation (Odero et al., 2020; Robb et al., 2025). In the context of healthcare services, this capacity reflects the ability to coordinate knowledge, align goals, and maintain long-term collaboration effectively (Saarinen, 2020; Tun et al., 2020). Building this capacity requires leaders who can integrate input from various stakeholders, pursue innovative strategies, and maintain ethical governance (Ma et al., 2020).

In addition, leaders in the health sector need to develop managerial competencies and partnership-building skills (Parboteeah and Zakaria, 2023; Qalaai et al., 2020) to adapt to a dynamic health ecosystem, which is increasingly influenced by digital technology, regulatory changes, and interorganizational dependencies (Pikkarainen et al., 2025). Adaptive leadership enables clinics to manage uncertainty while maintaining collaboration (Purwadi et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2024).

Therefore, this study aims to explore: (1) how partnership capacity influences partnerships with stakeholders, (2) how collaborative leadership strengthens these relationships, and (3) whether a dynamic health ecosystem acts as a moderating variable that influences the relationship between partnership capacity and stakeholder partnership outcomes.

1.1 Partnership capacity and stakeholder partnerships

Partnership capacity refers to an organization’s ability to build and sustain effective collaboration among diverse stakeholders (Moreno-Serna et al., 2020). Stakeholder partnerships are defined as strategic alliances formed through voluntary agreements between two or more organizations to collaborate in long-term service, distribution, or marketing activities (MacDonald et al., 2019). Partnership capacity encompasses two key dimensions: the ability to establish trust-based relationships and the interpersonal skills required to sustain stakeholder engagement (MacDonald et al., 2019). These mechanisms facilitate information sharing, coordination, and continuous learning (Vayaliparampil et al., 2021), thereby enhancing the effectiveness of stakeholder partnerships (Barakat et al., 2022). When supported by fair governance and shared accountability, strong partnership capacity fosters reciprocal accountability and adaptability (Dentoni et al., 2016). Accordingly, partnership capacity functions as a strategic organizational resource that enhances stakeholder participation, decision-making quality, and dynamic co-creation capability.

H1: Partnership capacity has a significant positive effect on stakeholder partnerships.

1.2 Collaborative leadership and enhancing stakeholder partnerships

Collaborative leadership refers to a leader’s ability to engage multiple actors in decision-making, foster mutual trust, and create shared value through open and participatory interactions (Lehmeidi, 2025). The effectiveness of collaborative leadership is reflected in its capacity to create a safe and respectful environment where partners feel recognized and committed to shared goals, an essential condition for successful stakeholder partnerships.

The success of collaborative leadership largely depends on two key forms of trust: internal trust and external trust. Internal trust among organizational members is fostered through openness, empowerment, and a shared vision, whereas external trust with outside stakeholders is developed through transparency, accountability, and consistent communication (Bryson et al., 2022). These two forms of trust mutually reinforce one another and form the foundation of long-term stakeholder relationships.

Unlike transactional leadership, which emphasizes control and compliance, collaborative leadership prioritizes participation, joint decision-making, and mutual benefit. This approach is particularly relevant in the healthcare context, where effective partnerships rely on the ability of diverse actors, such as healthcare professionals, regulators, and service providers, to coordinate under conditions of uncertainty (MacDonald et al., 2018).

Furthermore, collaborative leadership fosters high-quality communication, joint learning, and reinforcing interactions that sustain effective and long-term partnerships (Raik et al., 2005; Sánchez et al., 2020). Therefore, collaborative leadership serves as a strategic factor that strengthens the effectiveness of stakeholder partnerships.

H2. Collaborative leadership has a significant positive effect on stakeholder partnership.

1.3 The moderation roles of the dynamic healthcare ecosystem

In this study, the dynamic healthcare ecosystem is defined as a system that is continuously shaped by multiple factors, including accelerated technological innovation, ongoing policy reforms, multi-stakeholder engagement, and shifts in patient needs and expectations. These factors create an environment in which adaptation and negotiation among stakeholders are constant and essential processes (Elizondo, 2024). Such dynamic interactions are crucial for fostering synergy and improving stakeholder partnership outcomes (Loban et al., 2021).

In this context, the dynamic healthcare ecosystem is conceptualized as a moderating variable because it influences how partnership capacity translates into effective partnership outcomes. In relatively stable environments, partnership capacity alone may be sufficient to sustain collaboration. However, in more dynamic contexts, leaders must integrate additional resources, adjust strategies, and realign organizational goals to maintain partnership effectiveness (Belrhiti et al., 2024).

Therefore, the greater the dynamism of the healthcare ecosystem, the stronger the need for leaders to adapt, ensuring that partnership capacity continues to generate optimal and sustainable outcomes. This adaptive ability allows organizations to maintain effective partnerships despite changing conditions (Arabi et al., 2025). In this context, the dynamic healthcare ecosystem does not directly determine partnership success but instead moderates the strength of the relationship between partnership capacity and stakeholder partnership outcomes.

H3: The dynamic healthcare ecosystem moderates the relationship between partnership capacity and stakeholder partnership outcomes.

Based on the conceptual framework above, partnership capacity is viewed as a strategic organizational resource that enables effective collaboration with stakeholders. Collaborative leadership plays a critical role in strengthening this relationship by fostering trust, enhancing participation, and promoting the creation of shared value among partners. However, the effectiveness of this relationship depends on the level of dynamism within the healthcare ecosystem, where technological change, policy reform, and inter-organizational dependencies demand adaptive leadership responses. Accordingly, the dynamic healthcare ecosystem may either strengthen or weaken the influence of partnership capacity on stakeholder partnership outcomes.

This framework emphasizes that the success of stakeholder partnerships is not solely determined by internal organizational capacity but also by collaborative leadership behaviors and the external context in which partnerships operate. The interrelationships among these three core constructs are illustrated in Figure 1, which presents the proposed research model and the hypothesized relationships tested in this study.

2 Methodology

2.1 Participant and procedure

The study population consisted of 8,911 primary clinics registered with the Indonesian Ministry of Health as clinics providing general medical services, basic health care, and limited specialist consultations. Therefore, this study specifically focused on primary clinics operating throughout Indonesia. The minimum sample size was determined using the Krejcie and Morgan (1970) formula, resulting in a minimum sample recommendation of 368 clinics. During the survey process, this study successfully collected data from 370 respondents (each representing one clinic), exceeding the minimum sample size. To ensure adequate statistical power, data were collected from 370 respondents.

Simple random sampling was employed in this study, utilizing the clinic list numbers from the Ministry of Health as the sampling frame. Each selected clinic was contacted via email with a Google Form URL included in the email body, requesting participation from individuals in managerial positions (e.g., directors, CEOs, branch managers, or managers with decision-making authority regarding partnerships) in the survey. The reference questionnaire was in English and translated into Indonesian. Then, one Indonesian language expert and two health practitioners were asked to review the list of questions (content validity). Next, a trial was conducted involving 30 clinic managers to validate the clarity of the items and the appropriateness of the context.

The sampling distribution based on position included the following: marketing managers (43%), branch heads (35%), partnership leaders (8%), owners (5%), senior managers (4%), general managers (2%), and directors (3%). Based on geographical area, the respondents were spread across Western Indonesia (71%), Central Indonesia (24%), and Eastern Indonesia (4%), covering 25 provinces throughout Indonesia. This geographical distribution reflects the overall concentration of health facilities in the Java-Bali region. Regarding the educational background of the respondents, 88% held bachelor’s degrees, 10% had master’s degrees, and 2% possessed doctoral degrees. Meanwhile, the gender distribution was 63% women and 37% men, reflecting the dominance of female health workers in Indonesia.

2.2 Common method bias and measurement model

Since the data were collected using a single survey instrument, common method bias (CMB) was tested to ensure data validity (Kock et al., 2021). This study employed a “full collinearity” method (Kock et al., 2021), which involves creating latent variable scores for each construct and generating dummy variables randomly. Then, the latent variable scores were regressed on the dummy variables. To detect CMB, the variance inflation factor (VIF) value was examined, with a threshold of greater than 3.3 indicating a bias problem. Conversely, a VIF value below 3.3 indicates no serious CMB problem (Hair et al., 2022; Kock and Lynn, 2012). “Full collinearity” testing was performed using the SmartPLS 4.1.1.4 (Ringle et al., 2024) software, and the results showed that all VIF values ranged from 1.72 to 3.01, indicating that the dataset was free from CMB problems (Table 1).

The research model was assessed using the approach of Hair et al. (2022), employing partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) as both an evaluation tool and a measurement instrument for the outer and inner models. This process included the evaluation of convergent validity, discriminant validity, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and collinearity (Hair et al., 2020). Indicators for each construct were considered valid when outer loadings exceeded 0.70 and AVE values were greater than 0.50.

The indicators demonstrated outer loading values greater than 0.70, VIF values below 5, and AVE values ranging from 0.569 to 0.646. These results confirm that convergent validity was achieved for each construct. Furthermore, all items within the constructs were reliable, as indicated by CR values between 0.792 and 0.908, which fall within the acceptable range of 0.70 to 0.95. Accordingly, the measurement model evaluation presented in Table 2 was confirmed to be both valid and reliable.

2.2.1 Strategy analysis

The research model employed PLS-SEM using SmartPLS to assess the research hypothesis, both direct and moderation effects, based on bootstrapping techniques (Hair et al., 2022).

2.3 Descriptive statistics and correlation

Table 3 presents the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio results assessing discriminant validity. All HTMT ratios were below the threshold value of 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2015), indicating that each latent construct was empirically distinct from the others within the model (see Table 4).

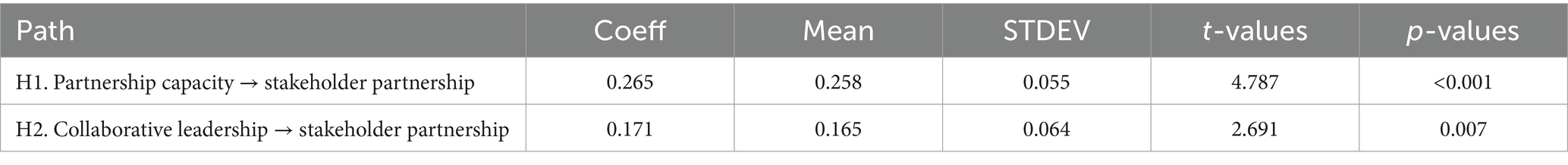

Hypothesis 1: Partnership capacity has a positive and significant impact on stakeholder partnerships in local primary clinics in Indonesia, with a value of β = 0.265, t-value = 4.787, and p-value of <0.001. Therefore, this hypothesis is accepted. Hypothesis 2 shows that collaborative leadership has a positive and significant impact on stakeholder partnerships, with a value of β = 0.171, t-value = 2.691, and p-value = 0.007 < 0.05. Therefore, this hypothesis is also accepted.

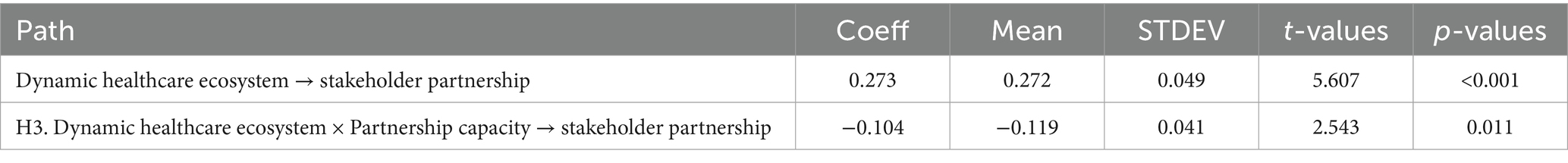

For Hypothesis 3, Table 5 shows that the dynamic healthcare ecosystem has a positive influence on stakeholder partnerships (β = 0.273, p < 0.001). The interaction term (β = −0.104, p = 0.011) reveals a significant negative moderation effect, indicating that increasing ecosystem dynamism attenuates the positive relationship between partnership capacity and stakeholder partnerships. Details are shown in Figure 2.

Simple slope analysis in Figure 3 showed that at low dynamic healthcare ecosystem levels (−1 SD), the effect of partnership capacity on stakeholder partnerships was strongest (β = 0.369). At average dynamic healthcare ecosystem levels, the effect decreased (β = 0.265), while at high dynamic healthcare ecosystem levels (+1 SD), the effect was weakest (β = 0.161). These findings indicate that every single increase in the dynamic healthcare ecosystem’s standard deviation reduces the strength of partnership capacity in stakeholder partnership relationships by 0.104 points, suggesting that the more dynamic the health ecosystem, the weaker the contribution of partnership capacity to stakeholder engagement.

The coefficient of determination (R2) measures the extent to which exogenous variables explain variations in endogenous variables. R2 ranges from 0 to 1, where a value close to 1 indicates that independent variables are highly effective in predicting the variation in dependent variables. Meanwhile, a value close to 0 indicates that the independent variable has limited explanatory ability to explain the variation in the dependent variable. A higher R2 value indicates that the predictor explains more changes in the outcome. Furthermore, the measurement of f2 shows how much each exogenous variable contributes to the endogenous variable. The interpretation of the f2 value is 0.02 = small, 0.15 = medium, 0.35 = large (Hair et al., 2022).

Based on Table 6, this research model explains that a combination of collaborative leadership variables, partnership capacity, dynamic healthcare ecosystems, and interaction effects can effectively explain 64.0% of the variance in stakeholder partnerships. Based on the effect size (f2), the largest individual contribution to explaining the variance in stakeholder partnerships was made by the dynamic healthcare ecosystem (f2 = 0.108), followed by partnership capacity (f2 = 0.080), the moderation effect (f2 = 0.066), and collaborative leadership (f2 = 0.034). Although all main predictors made a small contribution, these findings confirm that the factors of the dynamic healthcare ecosystem and partnership capacity have a relatively greater influence than the factor of collaborative leadership.

3 Discussion

This study examines the role of partnership capacity and collaborative leadership in shaping stakeholder partnerships in a dynamic health ecosystem. These findings reinforce the theoretical premise that organizational capacity and leadership are central elements in sustaining multi-stakeholder collaboration. In line with Odero et al. (2020), effective information sharing, mutual trust, and transparent communication emerge as fundamental elements of partnership success. These factors are especially critical in primary clinics, where leaders operate in complex and uncertain environments (Nwankwo and Gbadamosi, 2010).

From a leadership perspective, the results of this study align with Saarinen (2020), who emphasizes that leaders must proactively promote ecosystem and industry development initiatives to strengthen stakeholder collaboration. In this case, clinic leaders play a crucial role in aligning organizational resources with the strategic partnership’s goals. Their ability to integrate external resources and implement strategic decision-making can build trust, generate shared knowledge, and create a foundation for long-term partnerships.

Empirically, this study found that a dynamic health ecosystem has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between partnership capacity and stakeholder partnerships. This means that although partnership capacity remains an important internal capability, its effectiveness declines under conditions of high ecosystem dynamism. Theoretically, this can be explained by the environmental turbulence theory (Dess and Beard, 1984), which states that rapid technological innovation, policy changes, and stakeholder realignment can disrupt coordination mechanisms and reduce the stability of trust-based relationships. In volatile conditions, existing partnership structures may struggle to adapt quickly, thereby weakening the strength of internal capabilities (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993).

However, these findings do not imply that dynamic ecosystems are detrimental to partnerships. Instead, they highlight the need for complementary capabilities—adaptive leadership, flexible governance, and continuous learning mechanisms—that enable clinics to transform environmental uncertainty into opportunities for innovation. These adaptive mechanisms allow organizations to readjust their resources and maintain collaboration even when the ecosystem is unstable.

From the perspective of RBT, these findings highlight that organizational resources, such as professional expertise, communication infrastructure, and leadership competencies, are only valuable when aligned with environmental dynamics (Parboteeah and Zakaria, 2023). Clinics that continuously invest in leadership development and digital readiness are better equipped to leverage partnership capacity to create sustainable value for stakeholders, even in turbulent environments.

Finally, the demographic and professional diversity of respondents further supports the contextual nature of partnership management in Indonesia. The dominance of experienced clinic managers with region-specific expertise suggests that local leadership approaches play a crucial role in tailoring partnership strategies to the needs of communities in diverse geographic regions. These findings underscore the significance of contextual leadership and local stakeholder engagement in healthcare management.

3.1 Practical implication

In light of the study’s findings, three significant practical implications emerge concerning how clinic leaders can strengthen stakeholder partnerships within dynamic healthcare ecosystems. First, clinic leaders should cultivate adaptive leadership and strategic flexibility to navigate environmental dynamism. In rapidly changing healthcare environments, where technology, regulations, and patient expectations evolve simultaneously, leaders must develop the ability to sense environmental shifts and adjust partnership strategies accordingly. It can be achieved through continuous training in digital literacy, strategic foresight, and scenario planning, enabling leaders to anticipate changes and maintain stakeholder trust even in the face of uncertainty. Second, primary clinics need to institutionalize mechanisms for collaborative learning and cross-stakeholder communication. Establishing joint decision-making forums, data-sharing platforms, and regular partnership evaluations can enhance transparency and ensure that all stakeholders, including patients, corporate partners, and regulators, remain engaged. By fostering open communication and mutual accountability, clinics can strengthen both internal and external types of trust, which are essential for the long-term sustainability of partnerships. Third, organizations should invest in building partnership capacity as a strategic resource that complements leadership competence. It includes developing systems that integrate human resource development, ethical governance, and inter-organizational coordination. Empowering teams to share knowledge, align goals, and measure partnership outcomes helps transform individual capabilities into collective organizational strength. Such initiatives enable SME-based clinics to compete effectively and maintain collaborative resilience in Indonesia’s evolving healthcare landscape.

3.2 Limitations and future research

Although this study adheres to strict methodological standards, several limitations remain that should be acknowledged and addressed in future research. First, the study sample was limited to local SME-based primary clinics, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to hospitals or community health centers. Therefore, future studies may consider examining hospital organizations or conducting comparisons between the two. Second, the research data only captured the perspective of clinic leaders, excluding patients, regulators, and external partners whose experiences could provide a holistic understanding of the dynamics of partnerships. Future research should consider perspectives beyond the scope of this study. Fourth, this study was conducted in Indonesia, and comparisons with other countries in the Asia-Pacific region are needed to gain insights into collaboration strategies. In addition, future research could explore the moderating role of dynamic health ecosystems in the relationship between collaborative leadership and partnership capacity, as well as the interaction between individual and organizational factors in diverse health and cultural contexts. A mixed-methods approach can also help clarify the causal mechanisms linking adaptive leadership, partnership learning, and ecosystem performance.

4 Conclusion

This study concludes that partnership capacity and collaborative leaders have a significant impact on stakeholder partnerships. In addition, a dynamic healthcare ecosystem can weaken the relationship between collaborative leaders and stakeholder partnerships. Therefore, strengthening partnership capacity in the health sector requires a dual focus on developing organizational resources and improving leadership skills. Leaders must not only possess technical expertise but also strategic and relational competencies that foster trust, facilitate effective communication, and enable resource sharing—key elements for maintaining collaboration in healthcare.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SA: Software, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision. EK: Software, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Methodology. FA: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software, Project administration, Visualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Validation. AF: Resources, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation, Software, Project administration, Formal analysis, Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. find the hyphotesses of each variable path with Scopus AI.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas, Z., Sarwar, S., Rehman, M. A., Zámečník, R., and Shoaib, M. (2022). Green HRM promotes higher education sustainability: a mediated-moderated analysis. Int. J. Manpow. 43, 827–843. doi: 10.1108/IJM-04-2020-0171

Ang’ana, G. A., and Ongeti, W. J. (2023). Collaborative leadership and performance: towards development of a new theoretical model. J. Bus. 11, 297–308. doi: 10.12691/jbms-11-6-1

Arabi, S., Vindigni, D., and Butler-Henderson, K. (2025). Exploring challenges and opportunities in international healthcare partnerships: a thematic analysis. World Med. Health Policy 17, 456–467. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.70012

Barakat, S. R., Boaventura, J. M. G., and Gabriel, M. L. D. S. (2022). Organizational capabilities and value creation for stakeholders: evidence from publicly traded companies. Manag. Decis. 60, 2311–2330. doi: 10.1108/md-05-2021-0576

Belrhiti, Z., Bigdeli, M., Lakhal, A., Kaoutar, D., Zbiri, S., and Belabbes, S. (2024). Unravelling collaborative governance dynamics within healthcare networks: a scoping review. Health Policy Plan. 39, 412–428. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czae005

Bornman, J., and Louw, B. (2023). Leadership development strategies in interprofessional healthcare collaboration: a rapid review. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 15, 175–192. doi: 10.2147/jhl.s405983

Bryson, J., George, B., and Seo, D. (2022). Understanding goal formation in strategic public management: a proposed theoretical framework. Public Manag. Rev. 26, 539–564. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2022.2103173

Charernnit, K., Mathur, A., Kankaew, K., Alanya-Beltran, J., Singh, S., Sudhakar, P. J., et al. (2021). Interplay of shared leadership practices of principals, teachers’ soft skills and learners’ competitiveness in COVID 19 era: implications to economics of educational leadership. Stud. Appl. Econ. 39, 1–15. doi: 10.25115/eea.v39i12.6463

Dentoni, D., Bitzer, V., and Pascucci, S. (2016). Cross-sector partnerships and the co-creation of dynamic capabilities for stakeholder orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 135, 35–53. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2728-8

Dess, G. G., and Beard, D. W. (1984). Dimensions of organizational task environments. Admin. Sci. Q. 29, 52–73. doi: 10.2307/2393080

Elizondo, A. (2024). Governance intricacies in implementing regional shared care records: a qualitative study in the national health service, England. Health Informatics J. 30:14604582241290709. doi: 10.1177/14604582241290709

Goodman, C., Witter, S., Hellowell, M., Allen, L., Srinivasan, S., Nixon, S., et al. (2024). Approaches, enablers and barriers to govern the private sector in health in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMJ Glob. Health 8:e015771. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-015771

Hair, J. F., Howard, M. C., and Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 109, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

Hair, J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., and Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Jaworski, B. J., and Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 57, 53–70. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700304

Kock, F., Berbekova, A., and Assaf, A. G. (2021). Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 86:104330. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

Kock, N., and Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: an illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 13, 546–580. doi: 10.17705/1jais.00302

Krejcie, R., and Morgan, D. (1970). Sample size determination table. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30, 607–610.

Kumar, R. D. C. (2022). Leadership in healthcare. Clin. Integr. Care 10:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.intcar.2021.100080

Lagarde, M., and Palmer, N. (2018). The impact of health financing strategies on access to health services in low and middle income countries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018:CD0060924. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006092.pub2

Loban, E., Scott, C., Lewis, V., Law, S., and Haggerty, J. (2021). Improving primary health care through partnerships: key insights from a cross-case analysis of multi-stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces. Health Sci. Rep. 4:e397. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.397

Ma, H., Zeng, S., Lin, H., and Zeng, R. (2020). Impact of public sector on sustainability of public–private partnership projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 146:04019104. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001750

MacDonald, A., Clarke, A., and Huang, L. (2019). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainability: designing decision-making processes for partnership capacity. J. Bus. Ethics 160, 409–426. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3885-3

MacDonald, A., Clarke, A., Huang, L., Roseland, M., and Seitanidi, M. M. (2018). Multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG #17) as a means of achieving Sustainable communities and cities (SDG #11). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Moreno-Serna, J., Purcell, W. M., Sánchez-Chaparro, T., Soberón, M., Lumbreras, J., and Mataix, C. (2020). Catalyzing transformational partnerships for the SDGs: effectiveness and impact of the multi-stakeholder initiative El día después. Sustainability 12:7189. doi: 10.3390/su12177189

Nonet, G. A.-H., Gössling, T., Van Tulder, R., and Bryson, J. M. (2022). Multi-stakeholder engagement for the sustainable development goals: introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Ethics 180, 945–957. doi: 10.1007/s10551-022-05192-0

Nwankwo, S., and Gbadamosi, A. (2010). Entrepreneurship marketing. Entrepreneurship marketing: principles and practice of SME marketing. London: Routledge.

Odero, A., Pongy, M., Chauvel, L., Voz, B., Spitz, E., Pétré, B., et al. (2020). Core values that influence the patient—healthcare professional power dynamic: steering interaction towards partnership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:8458. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228458

Padilha, R. Q., Gomes, R., Lima, V. V., Soeiro, E., Oliveira, J. M., Schiesari, L. M. C., et al. (2018). Principles of clinical management: connecting management, healthcare and education in health. Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 23, 4249–4257. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320182312.32262016

Parboteeah, P., and Zakaria, R. (2023). Resource-based theory. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Pikkarainen, M., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., Iivari, M., Jansson, M., and Hong-Gu, H. (2025). Overseas innovation ecosystem collaboration in the healthcare sector. Technovation 147:103302. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2025.103302

Pillai, S. G. (2021). The importance of clinical leadership in healthcare quality improvement. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.18145.02401

Purwadi, P., Widjaja, Y., Junius, J., and Mahmudah, N. (2024). Strategic human resource management in healthcare: elevating patient care and organizational excellence through effective HRM practices. Golden Ratio Data Summ. 4, 88–93. doi: 10.52970/grdis.v4i2.540

Qalaai, S., Surji, K., and Sourchi, S. (2020). The essential role of human resources management in healthcare and its impact on facilitating optimal healthcare services. Qalaai Zanist Sci. J. 5, 1166–1188. doi: 10.25212/lfu.qzj.5.2.35

Raik, D. B., Siemer, W. F., and Decker, D. J. (2005). Intervention and capacity considerations in community-based deer management: the stakeholders’ perspective. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 10, 259–272. doi: 10.1080/10871200500292835

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., and Becker, J. -M. (2024). SmartPLS 4. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online at: http://www.smartpls.com

Robb, C. C., Brownell, K. M., Brännback, M., and Rumi, S. (2025). Applying resource-based theory to social value creation: a conceptual model of contributive advantage. J. Small Bus. Manag. 63, 147–169. doi: 10.1080/00472778.2024.2309498

Sánchez, F., Sandoval, A., Rodríguez-Pomeda, J., and Casani, F. (2020). Professional aspirations as indicators of responsible leadership style and corporate social responsibility. Are we training the responsible managers that business and society need? A cross-national study. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 36, 49–61. doi: 10.5093/jwop2020a5

Secundo, G., Toma, A., Schiuma, G., and Passiante, G. (2019). Knowledge transfer in open innovation. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 25, 144–163. doi: 10.1108/BPMJ-06-2017-0173

Singh, P., Singh, S., Kumari, V., and Tiwari, M. (2024). Navigating healthcare leadership: theories, challenges, and practical insights for the future. J. Postgrad. Med. 70, 232–241. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.jpgm_533_24

Tun, S., Wellbery, C., and Teherani, A. (2020). Faculty development and partnership with students to integrate sustainable healthcare into health professions education. Med. Teach. 42, 1112–1118. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1796950

Keywords: partnership capacity, collaborative leadership, stakeholder partnership, dynamic healthcare ecosystem, Indonesia

Citation: Apriza S, Kuncoro EA, Alamsjah F and Furinto A (2025) How do primary clinics successfully navigate stakeholder partnerships in dynamic healthcare ecosystems? A strategic imperative for leaders. Front. Commun. 10:1687114. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1687114

Edited by:

Ahmad Firdhaus Arham, National University of Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Salma Arabi, Charles Sturt University, AustraliaYusnaini Yusoff, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Apriza, Kuncoro, Alamsjah and Furinto. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sari Apriza, c2FyaS5hcHJpemFAYmludXMuYWMuaWQ=

Sari Apriza

Sari Apriza Engkos Achmad Kuncoro

Engkos Achmad Kuncoro Firdaus Alamsjah

Firdaus Alamsjah Asnan Furinto

Asnan Furinto