- 1Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

- 2University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

The Loneliness Model posits that social isolation activates cognitive biases wherein people perceive increased social threats and become less sociable. The longitudinal study reported here tested this theoretical tenet in the context of students transitioning to college. Specifically, we examined the association between social isolation and social skills for initiating new relationships, and also examined how cognitive flexibility could potentially buffer the strength of this direct effect. Participants were recruited at a university orientation in the late summer before the start of their first college semester. They reported their levels of social isolation, initiation skills, and cognitive flexibility in August (T1) and again in January (T2). The results showed that T1 social isolation predicted lower initiation skills at T2 while controlling for initiation skills at T1, thus social isolation predicted lower levels of initiation skills at a later time. Cognitive flexibility also buffered this negative relationship, indicating that cognitive flexibility may serve as a protective factor in the link between social isolation and communication skills. The practical and theoretical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

Social isolation is a widespread mental health issue that affects many people across the world (Goldman et al., 2024). Social isolation is a distressing cognitive state that is linked to cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and health issues across the lifespan (see Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010; Maes et al., 2019). Indeed, people who are lonely tend to have lower levels of basic psychological needs satisfaction (Curran and Elwood, 2024), as well as higher levels of physical health consequences such as cardiovascular disease and early mortality rates (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Although there are many relevant factors in understanding the nature of loneliness, a considerable amount of research has examined the links between loneliness and communication skills. This research shows that the association between these two constructs is complex and is often reciprocal; loneliness can be both a predictor of and predicted by low social skills (e.g., Moeller and Seehuus, 2019; Segrin, 2019; Qualter et al., 2015). Although complex and reciprocal in nature, social isolation can promote social withdrawal due to increased perceptions of social threat (Cacioppo et al., 2006) and fears of negative social evaluations from others (Qualter et al., 2015).

We consider the relationship between these variables in the context of students transitioning to college. The transition to college offers a unique insight into the links between social isolation and communication behavior for several reasons. Students are entering into a new social environment in which support and communication skills are key to both mental wellbeing and overall coping (Dorrance Hall and Scharp, 2021). Mental health challenges are quite common among undergraduate students, indicating that this life period can be distressing (Eisenberg et al., 2013). Additionally, the transition into a new social environment is particularly relevant to feelings of social isolation for late adolescent/early adults. Qualter et al. (2015) show that during this stage, people experience social isolation when they lack understanding, validation, and closeness from their social network. Overall, emerging adults entering college are at heightened risk for social isolation (Qualter et al., 2015) and their social skills play a major role in their mental health and loneliness (Moeller and Seehuus, 2019).

A longitudinal examination of social isolation and initiation skills in a period of life transition can offer both practical and theoretical advancements. Given that a sense of belongingness and social inclusion is vital for student wellbeing (Arslan, 2021) and that loneliness is linked to increased substance use among college students (Flesaker et al., 2024), testing the association between social isolation and communication skills to initiate new relationships among students’ transitioning to college can help scholars better understand and work with students who feel socially isolated when entering college. This study also adds to theoretical understandings of social isolation by exploring the potential buffering effect of cognitive flexibility on the link between social isolation and initiation skills. Cognitive flexibility is defined as “a person’s (a) awareness that in any given situation there are options and alternatives available, (b) willingness to be flexible and adapt to the situation, and (c) self-efficacy in being flexible” (Martin et al., 1998, p. 532). By adding in this buffering hypothesis, we expand theoretical understandings of social isolation by attending to a relevant protective factor in the link between social isolation and one’s motivation to connect to others. Thus, we add to the gap in literature on protective psychosocial variables within the context of the Loneliness Model. The following sections expand upon the theoretical model and specific arguments for each hypothesized path.

The loneliness model: social isolation and communication skills

A plethora of theoretical perspectives consider the relationship between social isolation and social skills, including Cacioppo and Hawkley’s (2009) Loneliness Model. According to the Loneliness Model (Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009), loneliness or perceived social isolation (synonymous terms) is a distressing psychological state that signals the importance of social connection (Goossens, 2018). Loneliness can drive people to connect more with others and relieve feelings of distress, but it can also create a perceptual bias wherein people actively distance themselves from others. Social isolation can increase one’s perceptions of social threat which lead to negative social expectations and recall of more negative social interactions (Cacioppo et al., 2006). Cacioppo et al. (2006) found that lonely individuals fear negative evaluation from others, have lower levels of optimism and social skills, and have increased shyness. As they explain, people who are socially isolated are more sensitive and attuned to social pain. The Loneliness Model postulates that socially isolated individuals feel unsafe and engage in social defensive mechanisms such as rejection of others and interpersonal coldness (Cacioppo et al., 2006). People who feel socially isolated are also motivated to avoid opportunities to be harmed by perceived social threats which leads to less opportunities to connect with others and social avoidance overall (Goossens, 2018). Moreover, Cacioppo et al. (2006) distinctly argue that loneliness is not a mere correlate of low socioemotional and sociable states, but rather loneliness is a key contributor to their activation. As such, we examine how perceived social isolation when entering college predicts initiating interactions and relationships skills after a person’s first academic semester.

Initiating interactions and relationships is a key component of social competence. People with initiation skills are able to begin new interactions with others and form new social relationships (Buhrmester et al., 1988). Thus, initiation skills are particularly important when people are adjusting to a new social environment (Buhrmester et al., 1988). In the context of adjusting to college, research shows that feeling a sense of belonging at a university increases perceptions of both self-worth and academic competence (Pittman and Richmond, 2008). Additionally, social skills such as communication confidence predict higher levels of resilience during students transition to college (Dorrance Hall and Scharp, 2021). On the other hand, negative social exchanges during the college transition are related to loneliness and low emotional wellbeing (Fiori and Consedine, 2013). We argue that initiation skills are also vital for this life transition given that belonging and social connection are critical components to student wellbeing and adjustment. For example, initiation skills have been linked to friendship formation for first year college students (McEwan and Guerrero, 2010). Moreover, initiation skills are critical for the college transition because students are expected to form many types of relationships during their first year at school (Dorrance Hall and Scharp, 2018). In addition to the breadth of relationships they are expected to form, research shows that the quality of social relationships are important predictors of loneliness (Qualter et al., 2015). Thus, students need to have skills initiating multiple types of high-quality relationships to foster a successful transition. However, based on the Loneliness Model, we suspect that social isolation will hinder initiation skills.

Toward that end, we first posit that social isolation will be negatively associated with initiation skills for students transitioning to college. Initiation skills are negatively linked to social sensitivity (Buhrmester et al., 1988), indicating that people who fear social rejection are less likely to engage in initiation strategies to meet or start conversations with new people. Initiation skills are also related to traits such as being outgoing and low levels of shyness, yet people who are socially isolated tend to disengage socially because they attribute their loneliness to factors outside of their control (Newall et al., 2009). Overall, both theory and past research indicate that entering college with increased feelings of social isolated should predict lower levels of initiation skills over time. Thus, we posit:

H1: Social isolation is negatively associated with initiation skills over time.

Cognitive flexibility as a buffer

Although we suspect a negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills, we also expect that higher levels of cognitive flexibility will buffer this effect. Cognitive flexibility could be a useful skill in the context of transitioning to college because it involves being adaptable and flexible to meet novel social demands (Martin et al., 1998). A significant body of research shows that cognitive flexibility is related to higher levels of social adjustment and overall wellbeing (e.g., Curran, 2018; Seiter and Curran, 2021). For example, Curran (2018) found that cognitive flexibility was related to lower levels of loneliness and higher levels of social skills and social support for both young adults and their parents. Likewise, cognitively flexible people are less aggressive interpersonally (Chesebro and Martin, 2003) and have lower anxiety symptoms (Curran et al., 2019). Overall, cognitive flexibility is related to numerous intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits.

Cognitive flexibility not only includes the skill to be adaptable, but it is also partly characterized by having the confidence to enact flexibility (Martin et al., 1998). This cognitive component could be crucial in buffering the effect from social isolation to initiation skills, as having the confidence to enter a new social environment with adaptability could help mitigate the negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills. As Curran (2018) argued, cognitively flexible people likely build positive and supportive social networks because they are adaptable and because they also report higher levels of prosocial characteristics such as interpersonal care and sensitivity. Thus, it is logical to reason that first year students who are higher in cognitive flexibility will use initiation skills as they adjust to a new social environment. As such, we hypothesize:

H2: Higher levels of cognitive flexibility will buffer the relationship between social isolation and initiation skills.

Method

Procedure and participants

The data for this project were part of a larger study on social skills and life transitions. Participants for this study were recruited at a university orientation in the late summer before the start of their first college semester in the summer of 2019. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be at least 18 years or older and they had to have completed high school in a county outside of the university to ensure that each participant was going through some level of life transition. The current study analyzes the first two waves of a three-wave longitudinal study that asked participants to complete surveys throughout their first year in school. In each wave of data collected, participants completed scales on their social skills, perceived social support, and mental health, among other variables not included in this study. The first wave of data were collected in the late summer before the start of their first semester. Participants were given a link to the online survey and were subsequently compensated with a five-dollar gift card upon completion. The second round of data collection occurred in January following their first semester. Participants were sent an email with the link to the survey and were asked to complete it at their own convenience. Upon their completion, participants were compensated with another five-dollar gift card. The IRB approved all procedures for this study.

There were 345 participants in total at Time 1 (T1). Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 25 years old (M = 18.36, SD = 1.36), and the sample was mostly female (78.2%). Also, the sample was largely White/Caucasian, as is the university from which the data were collected (93.9% White/Caucasian; 1.6% Black/African American, 2.0% Asian/Asian American, and 4.9% reported that they were of another race/ethnicity). There were 175 participants who completed the survey at T2, giving the sample a 49.3% attrition rate from T1 to T2. The attrition rate from T1 to T2 was within the expected range of 30–70% (Gustavson et al., 2012). Although a lower attrition rate is preferable, higher attrition rates for data with young adult samples are not detrimental to generalizability (Salthouse, 2014).

Measures

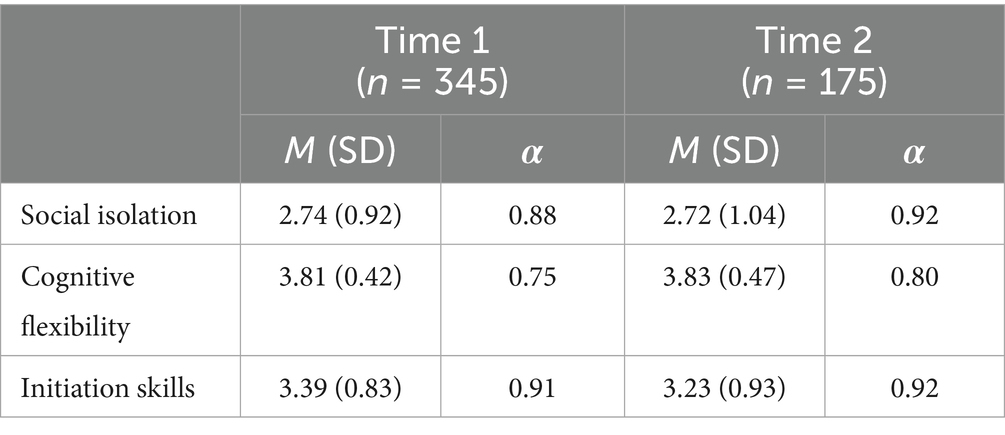

The univariate statistics for each measure are shown in the results section in Table 1.

Social Isolation was measured using Cella et al.’s (2010) 4-item Social Isolation Scale. The items (e.g., “I feel left out.”) were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of social isolation.

Initiation skills were accessed using the initiation competence Subscale of Buhrmester et al.’s (1988) Five Domains of Interpersonal Competence in Peer Relationships Scale. Participants reported their degree of comfort with each statement (e.g., “Finding and suggesting things to do with new people whom you find interesting and attractive.”). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = extremely uncomfortable to 5 = extremely comfortable). Higher scores indicated higher levels of initiation skills.

Cognitive flexibility was measured using the Cognitive Flexibility Scale (Martin and Rubin, 1995). This 12-item scale (e.g., “In any given situation, I am able to act appropriately.” was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores signified higher levels of cognitive flexibility.

Results

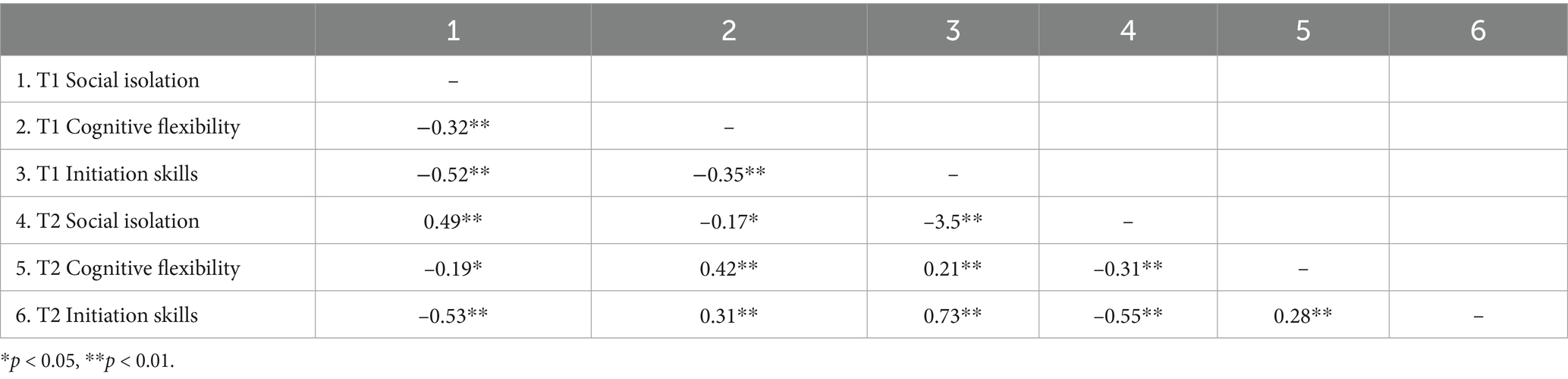

Table 1 shows the univariate statistics for the measures, and Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations among the variables. We also ran a series of paired samples t-tests to test the difference in reports at T1 versus T2 for each variable in the model. The first paired samples t-test showed that initiation skills at T1 (M = 3.24) were not significantly different that initiation skills at T2 (M = 3.23) t = −0.14, df = 174, p = 0.88. Next, social isolation at T1 (M = 2.77) was not significantly different that social isolation at T2 (M = 2.72) t = 0.62, df = 174, p = 0.54. Last, cognitive flexibility at T1 (M = 3.81) was not significantly different that cognitive flexibility at T2 (M = 3.83) t = −0.49, df = 174, p = 0.63.

To test our hypotheses, we used Model 1 of the Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS 4.2 Macro for SPSS. The macro runs a test of the direct effect from the exogenous variable (X: social isolation T1) to the endogenous variable (Y: initiation skills T2), as well as tests the interaction effect with the moderating variable (W: cognitive flexibility T1). Participant reports of initiation skills at T1 was used as a covariate in order to observe the effect between social isolation and initiation skills and over time, beyond reports of initiation skills at T1. The macro generated 95% bias corrected and adjusted confidence intervals (CI) with 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

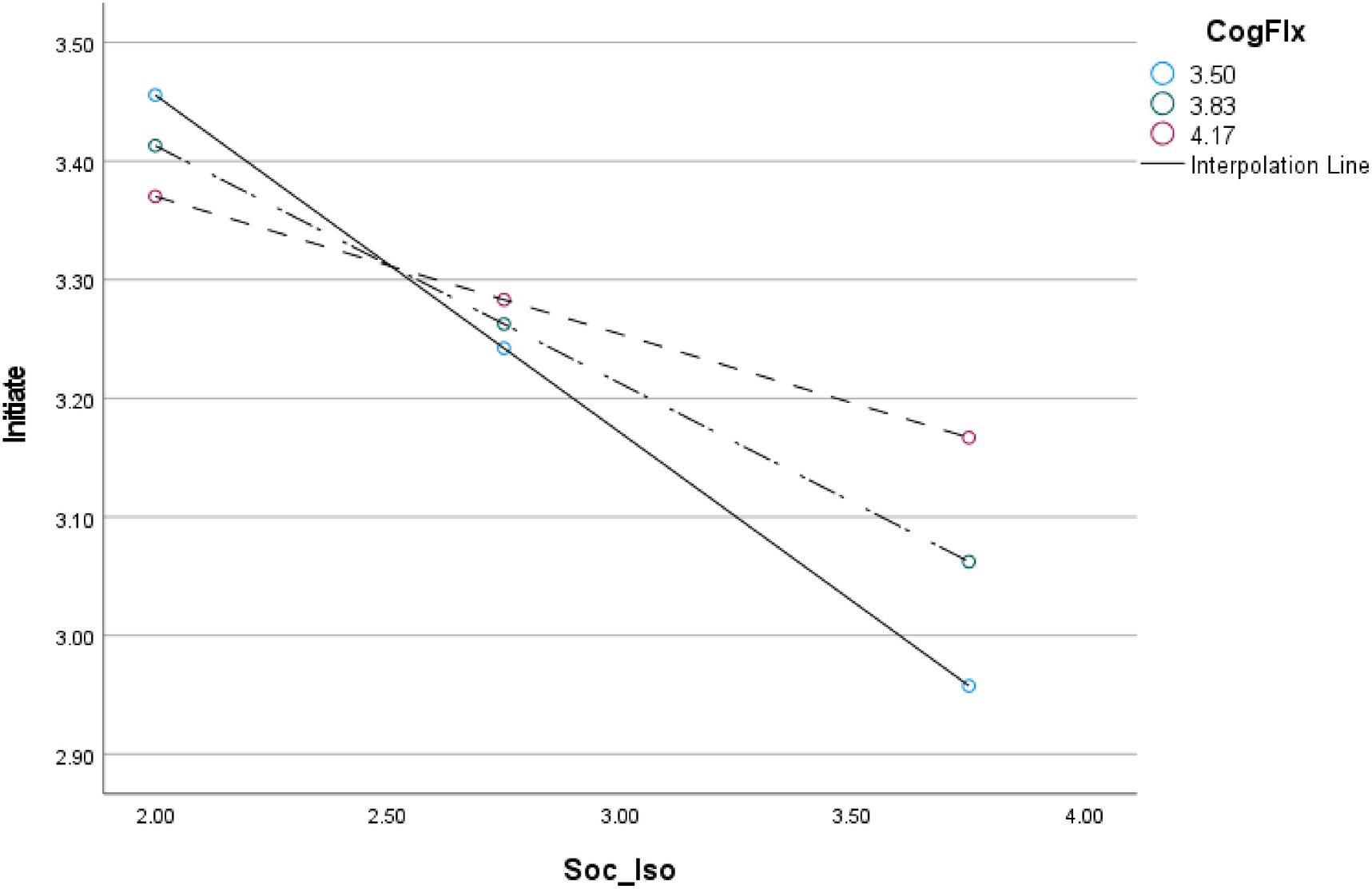

The results revealed that social isolation predicted decreased initiation skills at T2 while controlling for initiation skills at T1 (B = −1.169, SE = 0.48, t = −2.43, p = 0.016). Thus, H1 was supported. The interaction effect of cognitive flexibility at T1 and social isolation at T1 on initiation skills at T2 was also significant (B = 0.25, SE = 0.13, t = 1.98, p = 0.049). The graph visualizing the moderation effect (see Figure 1) indicates that the negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills is more severe for those with low cognitive flexibility, and indicates a buffering effect for those with higher levels of social isolation. Although there is a negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills, for people with higher cognitive flexibility, the relationship is weakened. As such, H2 was also supported.

Figure 1. Visual of the moderation effect. Initiate, Initiation Skills; Soc_Iso, Social Isolation; CogFlx, Cognitive Flexibility.

Discussion

Social isolation is a cognitive state that has detrimental effects on one’s social, emotional, and physical health (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). As such, the goal of this study was to examine how social isolation predicts initiation skills for undergraduate students transitioning to college. Grounded in the Loneliness Model (Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009), we hypothesized that students entering college with increased perceptions of social isolation would struggle to exhibit initiation skills in order to form new social relationships during their first semester. Indeed, our findings showed that social isolation at T1 predicted lower levels of initiation skills at T2 while controlling for T1 reports of initiation skills. During a time of life transition, social skills are vital to one’s overall adjustment, resilience, and wellbeing (Dorrance Hall and Scharp, 2021). Thus, this study was able to test a tenet of the Loneliness Model over time in a particularly important context. We also hypothesized that cognitive flexibility would buffer the effect from social isolation to initiation skills. Our results revealed that cognitive flexibility did moderate this path. People who had higher levels of cognitive flexibility at T1 were less affected by the negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills. This result indicates that, although social isolation may have deleterious effects on one’s social skills, cultivating higher levels of cognitive flexibility could potentially help buffer people a decrease in social skills.

According to the Loneliness Model, social isolation can produce a cognitive bias that makes people feel threatened and unsafe in their social environment (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Our results support this theoretical tenet, and show that those who feel socially isolated initiate less conversations to spark new relationships. Our results evaluate the nature of this relationship over time and show that entering a new social environment feeling isolated can diminish one’s ability or motivation to initiate relationships. Socially isolated people might be less likely to attempt initiation behaviors because they see their social environment as negative and potentially harmful (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Thus, even if socially isolated people have the ability to enact social skills, they could be less willing to do so if they anticipate negative outcomes. This conclusion is aligned with Newell et al.’s (2009) findings that socially isolated people have difficulties participating in social activities and believe that their social connectedness and integration with others is largely outside of their control. Practically, our results highlight the need for university and college administrators to both recognize and adapt practices that help socially isolated students initiate new relationships during their transition. Aligned with Dorrance Hall and Scharp (2021), we argue that higher education practitioners could focus on building resilience among students during their college transition. For example, it could be useful for socially isolated students to understand that feelings of loneliness can create certain cognitive biases that interfere with their social goals and desires. By raising awareness and putting in structures to build resilience, interventions can help socially isolated people manage loneliness and their overall wellbeing (Goldman et al., 2024).

The direct negative effect from social isolation to initiation skills over time further advances theoretical evidence for the Loneliness Model, and highlights the importance of understanding the cognitive effects of social isolation on social behaviors. Testing this effect across time is crucial for causal inferences in regard to social isolation and initiation skills. As Hawkley and Cacioppo (2010) explain, social isolation can activate a self-fulfilling prophecy wherein lonely people perceive social threats and distance themselves from others. These results hold important practical implications for helping people adjust to new social environments. Counselors, educators, and therapists could work with socially isolated people on their cognitive biases in social spaces. Again, if socially isolated people better understood their cognitive tendencies to view social environments negatively, they might be better able to challenge those thoughts and subsequently enact more social skills in new environments.

Furthermore, our results revealed that cognitive flexibility buffers the negative relationship between social isolation and initiation skills. These findings highlight the value of being socially adaptable during a life transition, and align with the body of research showing the benefits of cognitive flexibility. Cognitive flexibility could act as a buffer because those who are socially adaptable and confident in their ability to be flexible might adjust to new social situations with more ease. Martin and Rubin (1995) explain that cognitively flexible people are aware that there are multiple ways to act and communicate in any given situation. This cognitive state likely helps people transition to new social environments and realize that initiation skills are important and necessary for social connection. Indeed, this conclusion aligns with research showing that cognitive flexibility is linked to higher levels of social adjustment (e.g., Curran, 2018). Notably, our results are the first to our knowledge to evaluate the link between cognitive flexibility and social skills over time. This buffering effect highlights the importance of cognitive flexibility for enacting socially skilled behavior and overall social adjustment in a time of transition. Cultivating cognitive flexibility in young adults could be a useful protective factor particularly in the context of feeling socially isolated. Given how common it is to experience social isolation and loneliness (Goldman et al., 2024; Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010) it is vital to promote ways to protect people from the negative consequences of loneliness. While social isolation can activate negative cognitions about social engagements that lead to low sociability, cognitive flexibility can help people feel more comfortable and skilled in new social environments. Thus, counselors and educators could also consider the potential advantage of promoting cognitive flexibility for people adjusting to new social environments, particularly if they are prone to feelings of social isolation. Theoretically, our results also highlight how some individual psychosocial characteristics can potentially disrupt the link between social isolation and social skills more generally. While this study examined cognitive flexibility as a buffer between social isolation and initiation skills, other concepts (e.g., emotional intelligence; sociability; self-efficacy) could also potentially buffer this path. Moreover, the Loneliness Model postulates dual motivations related to loneliness: loneliness can motivate people to reduce loneliness by increasing their social connection, or it can make people even more socially apprehensive and less sociable (Goossens, 2018). Future research studies could examine the role of some characteristics such as cognitive flexibility and others, such as learned hopelessness and sociability, to determine how loneliness affects people’s motivation to initiate new relationships and forge connections in either prosocial or harmful ways.

Our results should also be understood based on several limitations. First, it is important to note that the sample for this study was predominantly White Taylor et al. (2025) found that race is an important factor in the link between loneliness and other mental health variables, highlighting the importance of more diverse samples in this context. The sample was also predominantly female; while Maes et al. (2019) show that loneliness is similar based on gender throughout the lifespan, future research should test these hypotheses with a representative sample. Moreover, the present study did not control for mental health status or consider other factors such as how far away students were from home, which degrees they were entering, and other characteristics that could impact the interpretation of the results. Also, the results presented are unstandardized values. Future research should address these limitations and also test these hypotheses in a different context for life transitions. This study only examined self-reported initiation skills in the context of transitioning to college. Different observations of initiation skills, such as other-rated or coded peer interactions could yield different results. Moreover, this study only investigated the link between social isolation and one aspect of communication competence. Future studies should address this limitation by examining the relationship between social isolation and multiple aspects of communication skills (e.g., self-disclosure, conflict management). Future studies should also consider the potential of cognitive flexibility as a buffering variable in other contexts. In doing so, future research can show a more holistic understanding of how cognitive flexibility functions in the link between mental health and social skills.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board, Utah State University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TC: Software, Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Methodology. AA: Software, Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by a Creative Activity Research Enhancement grant from the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Utah State University and by a Faculty Seed Grant from the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Georgia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arslan, G. (2021). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness. Aust. J. Psychol. 73, 70–80. doi: 10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499

Buhrmester, D., Furman, W., Wittenberg, M. T., and Reis, H. T. (1988). Five domains of competence in peer relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55, 991–1008. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.991

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., et al. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 1054–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007

Cacioppo, J. T., and Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005,

Cella, D., Riley, W., Stone, A., Rothrock, N., Reeve, B., Yount, S., et al. (2010). The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011,

Chesebro, J. L., and Martin, M. M. (2003). The relationship between conversational sensitivity, cognitive flexibility, and verbal aggressiveness and indirect interpersonal aggressiveness. Commun. Res. Rep. 20, 143–150. doi: 10.1080/08824090309388810

Curran, T. (2018). An actor-partner interdependence analysis of cognitive flexibility and indicators of social adjustment among mother-child dyads. Pers. Individ. Differ. 126, 99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.025

Curran, T., and Elwood, R. E. (2024). A theoretical integration of the social skill deficit vulnerability model and social determination theory in examining young adult loneliness. Front. Commun. 9, 1–6. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1491806

Curran, T., Worwood, J., and Smart, J. (2019). Cognitive flexibility and anxiety symptoms: the mediating role of destructive parent-child conflict communication. Commun. Rep. 32, 57–68. doi: 10.1080/08934215.2019.1587485

Dorrance Hall, E., and Scharp, K. M. (2018). Testing a mediational model of the effect of family communication patterns on student perceptions of the impact of the college transition through social communication apprehension. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46, 429–446. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1502461

Dorrance Hall, E., and Scharp, K. M. (2021). Communicative predictors of social network resilience skills during the transition to college. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 38, 1238–1258. doi: 10.1177/0265407520983467

Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., and Speer, N. (2013). Mental health in American colleges and universities: variation across student subgroups and across campuses. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 201, 60–67. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab077,

Fiori, K. L., and Consedine, N. S. (2013). Positive and negative social exchanges and mental health across the transition to college: loneliness as a mediator. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 30, 920–941. doi: 10.1177/0265407512473863

Flesaker, M., Freibott, C. E., Evans, T. C., Gradus, J. L., and Lipson, S. K. (2024). Loneliness in the college student population: prevalence and associations with substance use outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 73, 3255–3261. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2024.2400105,

Goldman, N., Khanna, D., El Asmar, M. L., Qualter, P., and El-Osta, A. (2024). Addressing loneliness and social isolation in 52 countries: a scoping review of national policies. BMC Public Health 24:1207. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18370-8,

Goossens, L. (2018). Loneliness in adolescence: insights from Cacioppo's evolutionary model. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 230–234. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12291

Gustavson, K., von Soest, T., Karevold, E., and Røysamb, E. (2012). Attrition and generalizability in longitudinal studies: findings from a 15-year population-based study and a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Public Health 12:918. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-918,

Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40, 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8,

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., den Van Noortgate, W., and Goossens, L. (2019). Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: a meta–analysis. Eur. J. Personal. 33, 642–654. doi: 10.1002/per.2220

Martin, M. M., Anderson, C. M., and Thweatt, K. S. (1998). Aggressive communication traits and their relationships with the cognitive flexibility scale and the communication flexibility scale. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 13, 531–540.

Martin, M. M., and Rubin, R. B. (1995). Development of a communication flexibility measure. Psychol. Rep. 76, 623–626. doi: 10.1080/10417949409372934

McEwan, B., and Guerrero, L. K. (2010). Freshmen engagement through communication: predicting friendship formation strategies and perceived availability of network resources from communication skills. Commun. Stud. 61, 445–463. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2010.493762

Moeller, R. W., and Seehuus, M. (2019). Loneliness as a mediator for college students' social skills and experiences of depression and anxiety. J. Adolesc. 73, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.03.006,

Newall, N. E., Chipperfield, J. G., Clifton, R. A., Perry, R. P., Swift, A. U., and Ruthig, J. C. (2009). Causal beliefs, social participation, and loneliness among older adults: a longitudinal study. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 26, 273–290. doi: 10.1177/0265407509106718

Pittman, L. D., and Richmond, A. (2008). University belonging, friendship quality, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. J. Exp. Educ. 76, 343–362. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.76.4.343-362

Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., et al. (2015). Loneliness Across the Life Span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 250–264. doi: 10.1177/1745691615568999

Salthouse, T. A. (2014). Selectivity of attrition in longitudinal studies of cognitive functioning. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 69, 567–574. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt046,

Segrin, C. (2019). Indirect effects of social skills on health through stress and loneliness. Health Commun. 34, 118–124. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2017.1384434,

Seiter, J., and Curran, T. (2021). Social distancing fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mediation analysis of cognitive flexibility, fatigue, depression, and adherence to CDC guidelines. Commun. Res. Rep. 38, 68–78. doi: 10.1080/08824096.2021.1880385

Keywords: social skills, social isolation, cogntive flexibility, lonelineness, college transition

Citation: Curran T and Arroyo A (2025) Social isolation and initiation skills: a longitudinal test of the loneliness model and the buffering effect of cognitive flexibility. Front. Commun. 10:1687413. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1687413

Edited by:

Codruta Alina Popescu, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Iuliu Hatieganu, RomaniaReviewed by:

Olga Strizhitskaya, Saint Petersburg State University, RussiaAna Petak, University of Zagreb, Croatia

Copyright © 2025 Curran and Arroyo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Timothy Curran, dGltLmN1cnJhbkB1c3UuZWR1

Timothy Curran

Timothy Curran Analisa Arroyo2

Analisa Arroyo2