- Department of Business, Marketing and Law, USN School of Business, University of South-Eastern Norway, Hønefoss, Norway

In 2025, the release of the Minecraft movie triggered a wave of youth-driven audience participation centered on the meme reference “chicken jockey,” which escalated into viral, in-theater performances. This paper examines the event as a case of memetic performance, where digital cultural scripts shape real-world behavior. Drawing on media ritual theory, participatory culture, and platform studies, the analysis explores how symbolic fluency and algorithmic amplification transform spectatorship into collective ritual. Using an interpretive case study approach based on secondary sources, the study situates the “chicken jockey” chant within a broader shift toward participatory spectacle. While focused on a single, culturally specific case, the paper offers conceptual insights into how memes function as both communicative codes and ritual cues, blurring boundaries between online signaling and offline performance in a platform-mediated media environment.

1 Introduction

In 2025, a peculiar media phenomenon unfolded in cinemas across the world (Aulbach, 2025; Milmo et al., 2025): during early screenings of the highly anticipated A Minecraft Movie (IMDb, 2025), young audience members began chanting, cheering, and even throwing popcorn at the screen in response to a single line: “Chicken jockey!” Delivered by Jack Black’s character upon encountering a baby zombie riding a chicken, the line referenced a well-known but relatively rare occurrence in the Minecraft video game (Allgood, 2015). What might have been a minor moment in a family-friendly film quickly escalated into a viral spectacle, with news outlets reporting disruptions in theaters and cinemas issuing warnings about the behavior (Milmo et al., 2025). The incident was widely likened to the participatory chaos of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, but reimagined for a new generation of digitally native viewers, armed with smartphones and memes (Zhan, 2025).

This paper uses the “Chicken Jockey” episode as a case study to explore how internet meme culture is reshaping the experience of cinematic media (Cutting, 2021; Pett, 2021). Specifically, it examines how digital-native audiences are importing participatory norms from online platforms into traditional viewing contexts.

In doing so, they are not merely reacting to content but actively co-producing it as a social ritual. These developments raise questions about authorship, media reception, generational aesthetics, and the porous boundaries between online and offline cultural practices. While this study centers on a specific event—the audience response to the Minecraft movie’s “chicken jockey” moment—it aims to use this case as a lens through which to theorize broader transformations in media reception and ritual, particularly within digitally native, Anglo-American youth cultures.

Drawing on theories of memetic transmission, participatory culture, and mediated ritual (e.g., Milner, 2018; Shifman, 2014; Turner, 1969), the analysis situates the Minecraft event within a broader cultural shift. As the logic of meme-making increasingly influences not just content but audience behavior, the cinema becomes a stage for meme performance—a space where shared digital literacy and symbolic reference are enacted communally. This convergence of meme and media spectacle represents a key transformation in how meaning is made and experienced in contemporary media.

To conceptualize these emerging behaviors, the paper further develops the notion of memetic performance, which has previously been applied to TikTok (Cervi and Divon, 2023; Trillò, 2024; Weiß et al., 2025). In the case of the Minecraft movie, it denotes a hybrid media ritual structured by digital platform dynamics, symbolic fluency, and participatory cues drawn from internet culture.

This paper employs an interpretive case study approach, drawing on secondary data. The analysis draws on media coverage, user-generated content (e.g., TikTok videos and social media posts), and existing scholarly literature in media studies, platform analysis, and cultural theory. No primary data were collected. Instead, the study uses the “chicken jockey” event as a theoretically generative case to explore how digital cultural scripts and algorithmic infrastructures shape participatory audience behavior. The aim is not empirical generalization but conceptual insight into the ritualization of media reception in platform-saturated environments.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the methodology. Section 3 outlines the theoretical basis for understanding memes as communicative codes and cultural rituals. Section 4 provides a brief overview of Minecraft as a memetic ecosystem. Section 5 presents the empirical case of the 2025 film and the “Chicken Jockey” incident. Section 6 interprets the event through the lens of participatory spectacle and youth cultural practice. Section 7 considers the broader implications for media production and reception in an age of ubiquitous meme fluency. The conclusion in Section 8 reflects on the future of cinema as a participatory, meme-inflected cultural space. Finally, Section 9 is the epilogue, which speculates about future rituals in meme-inflected media.

2 A brief note on methodology

This study adopts an interpretive case study design, examining the “chicken jockey” phenomenon as a theoretically generative example of meme-based audience participation. Because the event unfolded in real time during 2025 and no fieldwork was possible, the analysis draws exclusively on secondary sources, including journalistic coverage, widely circulated TikTok and Instagram clips, and relevant scholarship.

Sources were selected for their salience, circulation, and diversity, balancing mainstream reporting, user-generated content, and academic commentary. These materials were analyzed through close reading and thematic interpretation, focusing on ritual, performative, and platform dynamics of audience behavior.

Given that viral events are often amplified or dramatized by both journalism and platform logics (Couldry, 2003, 2012; Nieborg and Poell, 2018), these materials are treated as mediated constructions rather than direct accounts of reality. The approach, therefore, provides conceptual insight rather than empirical generalization, reflecting the interpretive tradition in qualitative case study research (e.g., Stake, 1995; Walsham, 2006).

3 Memes as communal codes and media ritual

Memes, in their contemporary digital form, are not merely humorous images or fleeting social media trends (Denisova, 2019; Miltner, 2018; Shifman, 2014). They function as shorthand expressions of collective knowledge, humor, and identity—forms of participatory vernacular that rely on shared recognition and implicit cultural fluency. Internet memes are not isolated items but groups of digital content sharing common characteristics of form, content, and stance, created with awareness of each other and circulated by many users (Shifman, 2014). This view frames memes not as discrete artifacts but as cultural templates, continually remixed and iterated upon by online communities.

Recent scholarship has further emphasized the sociocultural role of memes as a form of digital folklore (Shifman, 2014), operating much like oral traditions in pre-digital societies. They encode values, in-jokes, and social commentary, often with multilayered irony or absurdity. Memes can be viewed as “ready-made language,” composed of stereotypes and symbolic references that allow individuals to signal belonging within specific online cultures (Brown, 2022). Like vernacular speech genres in the Bakhtinian tradition (Bakhtin, 1986), memes rely on dialogic resonance: they make sense only within the context of other memes and the communal experiences they reference.

In this sense, memes are not only communicative devices but ritualistic ones. Their circulation and re-circulation create bonds among users, generating what Turner (1969) called communitas—a spontaneous sense of unstructured community through shared experience. This ritual function becomes especially visible when memes leap from digital platforms into physical spaces. When audiences chant a meme line in a theater, they enact a form of collective effervescence in the Durkheimian sense, a spontaneous shared energy rooted in mutual recognition and group identity (Durkheim, 1912/1965).

A central conceptual tension arises between the apparent spontaneity traditionally associated with ritual and the pre-coordinated quality of the “chicken jockey” response. Classical accounts of collective effervescence (Durkheim, 1912/1965) emphasize unstructured eruptions of shared energy, while the Minecraft case involved online rehearsal and anticipatory scripting. Rather than viewing these as mutually exclusive, the phenomenon can be understood as a hybrid ritual form: spontaneity in performance, yet structured by digital scripts circulating in advance. The ritual energy in theaters was real and immediate, but it was primed by algorithmic cues and memetic rehearsal. This hybrid quality is what distinguishes “memetic performance” from earlier frameworks such as participatory culture or spreadable media. It highlights not only audience creativity but also the infrastructural role of platforms in organizing the conditions of ritual enactment.

These participatory performances also echo the notion of convergence culture (Jenkins, 2006), in which media consumers are not passive recipients but active contributors to meaning-making. In their formulation of “spreadable media,” Jenkins et al. (2013) contrast old models of viral content transmission with more participatory, user-driven forms of engagement. Here, the meme is not just something passed along, but something performed, refashioned, and embedded into new cultural contexts.

The “Chicken Jockey” moment in the Minecraft movie exemplifies how memes can evolve from symbolic reference points to embodied social rituals. The meme’s logic—recognition, repetition, and communal joy—was carried into the movie theater, transforming a moment of passive reception into an improvised participatory event. This suggests that memes, while originally born in digital spaces, are increasingly serving as frameworks for offline interaction, especially among digitally native youth audiences. Understanding this shift requires attention to both the symbolic content of memes and the performative, ritualistic ways in which they are deployed in physical media environments.

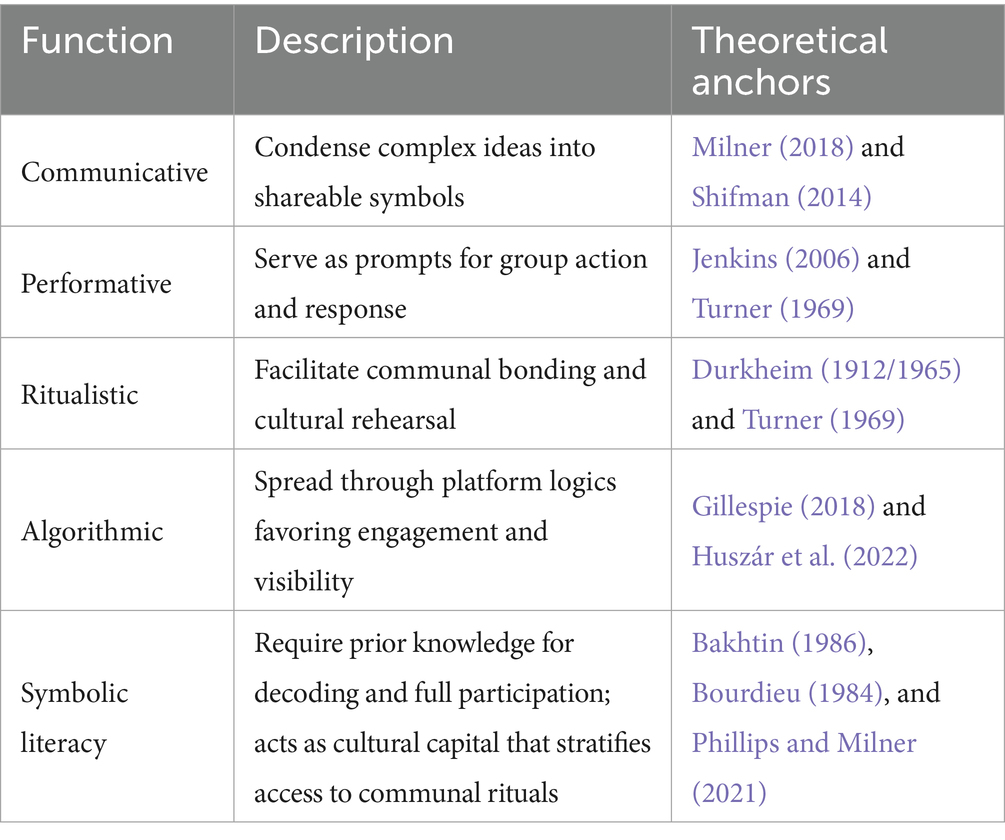

Taken together, these dimensions position memes not simply as units of cultural transmission but as embedded, ritualistic performances structured by both community norms and digital infrastructures. These layered roles reflect how memes operate at the intersection of communication, culture, and performance. To capture this multifaceted nature, Table 1 outlines five key functions that memes perform in participatory media environments. These functions are not mutually exclusive; rather, they overlap and compound, enabling memes to act as both symbolic shorthand and collective ritual. By linking each function to relevant theoretical traditions, the table demonstrates how interdisciplinary perspectives—from folkloristics to platform studies—can enrich our understanding of meme phenomena.

As the table shows, memes are not simply humorous or disposable content but integral components of contemporary symbolic life. Their communicative role helps distill complex ideas into shareable fragments; their ritualistic and performative dimensions support communal belonging; and their algorithmic spread ensures visibility within platform economies. Importantly, symbolic literacy—memes as cultural capital—further stratifies participation, privileging those who can “read” the meme and act on its cue. This theoretical framing sets the stage for understanding how a moment like “chicken jockey” can catalyze a collective performance far beyond the screen.

4 Minecraft and meme culture: context and history

Since its early public release (alpha build) in 2009 and its official release in 2011, Minecraft has functioned not only as a sandbox game but as a platform for creative expression, cultural exchange, and memetic proliferation (Apperley, 2015; Duncan, 2011; Garrelts, 2014; Thompson, 2016). Its blocky aesthetic, open-ended gameplay, and minimal narrative have made it uniquely conducive to the production and circulation of memes (Romano, 2025). As a digital environment that invites user-generated content (Newman, 2019; Nguyen, 2016), Minecraft fosters a participatory culture aligned with Jenkins (2006) account of convergence. Players do not simply engage with a fixed game world—they modify, narrate, and share their experiences in ways that often blur the boundary between gameplay and social performance (Agius and Lerviks, 2024; Garrelts, 2014).

The Minecraft meme ecosystem emerged organically from this participatory infrastructure. Early memes included in-game screenshots with captions, YouTube Let us Plays that narrated survival experiences, and music videos like the “Revenge” parody by CaptainSparklez, which reworked Usher’s “DJ Got Us Fallin’ in Love” with lyrics about creepers (CaptainSparklez, 2011). Among the most enduring memetic figures are the “creeper” itself—an icon of both danger and comic failure—and the various improbable mob configurations that sometimes occur during gameplay. One such configuration is the “chicken jockey”: a baby zombie riding atop a chicken, introduced in a 2013 game update (Allgood, 2015). Rare and often absurd in appearance, the chicken jockey quickly gained recognition within Minecraft lore and fan communities.

The absurdity of the chicken jockey made it ripe for memetic transformation. It was referenced in countless TikTok videos, fan animations, and modded gameplay clips. Its strangeness—combining the menacing speed of a baby zombie with the harmless image of a clucking chicken—lent itself to remixing and joke formats. Over time, it became a touchstone for in-game surprise and comedic chaos, a kind of inside joke among experienced players.

This in-game memetic recognition was reinforced by the ways in which Minecraft became deeply embedded in the cultural environments of children and teens. For over a decade, it has been not just a game but a social space, a classroom tool, and a creative outlet (Garrelts, 2014; Lane and Yi, 2017). Its characters and scenes have appeared in school projects, birthday cakes, and Halloween costumes. In this sense, the memetic logic of Minecraft—its capacity to produce and sustain iconic images, phrases, and narrative fragments—became a generational vernacular (Thompson, 2016).

The 2025 Minecraft movie, then, entered a media landscape already saturated with fan knowledge and meme fluency. The audience did not approach the film as a self-contained narrative experience but as a site of potential recognition and communal signaling. Memes like the chicken jockey were not simply easter eggs for attentive viewers; they were cultural artifacts waiting to be activated. The movie thus became an opportunity not just to view a story, but to participate in a shared act of memetic celebration. This context set the stage for the events that unfolded upon the film’s release—events that exemplify the convergence of media content and participatory meme ritual.

While the Minecraft meme ecosystem is distinctive, similar patterns of audience participation can be found in other cultural contexts. For example, K-pop concerts often feature coordinated fan chants, where audiences collectively recite lines or slogans at key moments in songs, blurring the line between performance and reception (Ismail and Khan, 2023; Tran-Nguyen, 2025). Likewise, fan cultures in Japan have long cultivated collective modes of audience participation, with call-and-response practices and synchronized reactions transforming venues into sites of shared performance (e.g., Ito et al., 2012; Raz, 1983; Simone, 2017). These parallels highlight that the memetic logics shaping the Minecraft event are not confined to Western youth cultures, but resonate across diverse global fan practices, each with their own symbolic codes and performative rituals.

5 The 2025 film and the “chicken jockey” event

The Minecraft movie, released globally in 2025 by Warner Bros (IMDb, 2025), was highly anticipated by a multi-generational audience. With Jack Black cast in a leading role and a production strategy aimed at blending humor, action, and franchise fidelity, the film sought to bring the open-world aesthetic and iconic creatures of Minecraft to the big screen. Among the numerous references to in-game lore, one line stood out: “It’s a chicken jockey!” This moment, uttered with exaggerated enthusiasm by Black’s character in response to the rare mob combination, was intended as both a humorous nod to veteran players and a quick piece of fan service. What followed, however, far exceeded expectations (Aulbach, 2025).

Reports quickly emerged of widespread disruptions during screenings. Viewers—primarily children and teens—reacted to the line not with laughter or applause, but with full-blown eruptions of noise, chanting, and physical movement. Popcorn was thrown, chants of “chicken jockey” echoed through theaters, and audience videos went viral on TikTok and Instagram. In several countries, cinema chains issued statements warning patrons against disruptive behavior, and some venues began screening the film only for supervised groups to curb the chaos (Milmo et al., 2025).

The origins of this response appear to lie in a combination of meme familiarity, audience expectation, and platform amplification. The “chicken jockey” moment had been teased in trailers and was the subject of social media speculation before the film’s release. On platforms like TikTok, fans had already begun rehearsing their reactions, encouraging others to join in the “jockey riot.” When the scene arrived, it was not experienced passively, it was anticipated and collectively performed.

Commentators were quick to draw parallels to The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), where cult screenings feature audience participation, call-backs, and dress-up (Austin, 1981; Kinkade and Katovich, 1992; Pett, 2021). Other recent examples underscore the broader cultural trend. The so-called “Gentleminions” phenomenon in 2022 saw groups of young fans attending Minions: The Rise of Gru in formal attire, performing chants, and documenting the experience for TikTok, prompting some cinemas to restrict entry (Andrew, 2022; Fahy and Oxenden, 2022). Similarly, esports tournaments often generate participatory chants and meme-based rituals that migrate from online discourse into live events. Together with Rocky Horror, these cases show that meme-driven performance is part of a longer lineage of participatory spectatorship, but one intensified by the speed and visibility of digital platforms.

Yet the Minecraft incident was distinct in several ways. First, it occurred on opening weekend, without years of accreted tradition. Second, it was fueled by a digital meme logic rather than a cinephilic ritual (Austin, 1981). Third, it was generationally specific: the participants were overwhelmingly young, digitally native, and steeped in a culture of ironic, fast-paced, and fragmentary media consumption.

As Zhan (2025) notes, this characterizes the phenomenon not as a spontaneous eruption, but as a coordinated memetic flash mob—an orchestrated display of audience behavior shaped by preexisting online scripts and expectations. The meme did not simply appear within the film; it had already been circulating and was waiting for activation. The line “chicken jockey!” acted as a trigger for a preloaded behavioral script—one co-authored not by the filmmakers but by online communities. Theaters became, however briefly, spaces of participatory spectacle where meaning was not contained by the screen but enacted in the auditorium.

This convergence of meme, media, and audience response presents a new form of reception—what might be called “memetic performance” (Cervi and Divon, 2023; Trillò, 2024; Weiß et al., 2025). Rather than interpreting or critiquing a moment, audiences reproduce and amplify it in real time, using social cues learned online. The meme becomes both content and cue, a fragment that prompts communal engagement. As this case illustrates, the line between on-screen moment and off-screen ritual is becoming increasingly thin in a culture where viewers are also performers and every scene is a potential meme.

6 Participatory spectacle and audience viewing cultures

The eruption of audience participation during the Minecraft movie’s “chicken jockey” scene reflects a broader cultural shift in the norms of media engagement, mostly visible among younger, digitally native audiences. What older generations may perceive as disruptive or disrespectful behavior—screaming during films, filming one’s reaction, or rehearsing memes in public—is, for many digitally native audiences, a form of cultural fluency. The incident underscores how younger platform-oriented viewers tend to approach media not as fixed texts to be absorbed in silence, but as open sites for interactivity, commentary, and performance.

This participatory sensibility is shaped by the media ecosystems these generations inhabit. Platforms like TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram Reels normalize rapid cycles of creation, reaction, and remix. Audiences do not merely consume content; they respond to it with stitches, duets, reaction videos, and meme formats. These practices foster a sense of co-creation and cultural immediacy: meaning is something made together, not something received from above. In this context, the film screening becomes another platform, and the theater becomes a stage.

The “chicken jockey” chant exemplifies what convergence culture (Jenkins, 2006)—where media content flows across multiple channels and is shaped by the active participation of users. However, the Minecraft event also signals an intensification of convergence, where not only content but affective response is collectively scripted and disseminated. The shared outburst was not just an expression of joy or recognition; it was a knowing performance of group identity, signaling in-group awareness and memetic competence.

This ritualized mode of viewing also recalls Émile Durkheim’s (1912/1965) concept of collective effervescence—the intense energy generated by group participation in a shared symbolic act. In religious contexts, this might be a ceremony or rite; in modern meme culture, it is a shout of “chicken jockey” delivered by hundreds of kids in sync. These moments produce a feeling of belonging and intensity, reinforced by their visibility on social media. When clips of the chant circulated online, they both documented the event and encouraged further reenactment in subsequent screenings, extending the ritual cycle.

These emerging behaviors also reflect the growing role of algorithmic amplification (Huszár et al., 2022; Milli et al., 2025) in cultural performance. Platforms like TikTok do not merely reflect cultural practices—they shape them through curated discovery mechanisms such as the “For You Page,” which rewards repetition, virality, and recognizable formats (Bhandari and Bimo, 2022; Milton et al., 2023). Audience members who filmed their reactions to the “chicken jockey” moment were not just capturing memories; they were producing content for algorithmic reward. This incentivizes pre-performance and scripting, encouraging attendees to exhibit expected behaviors in the hope of gaining social visibility. Platforms both invite and discipline user behavior through these logics of engagement (Gillespie, 2018). Beyond inviting participation, platforms also set the boundaries of acceptable performance. Algorithmic governance plays a key role in determining which memes are surfaced or suppressed, shaping not only what gains traction but what kinds of cultural rituals are institutionally legible. In this way, the chant was not only a moment of collective effervescence but a performance calibrated for maximum digital transmission.

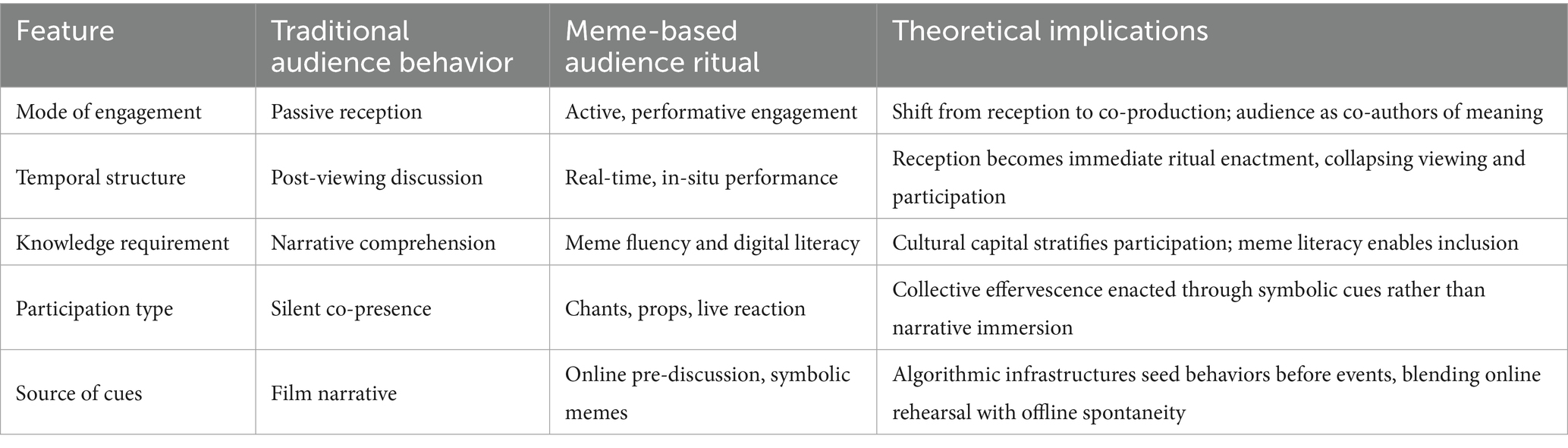

To better understand how meme-based rituals diverge from traditional audience behavior, Table 2 contrasts these forms of engagement along key experiential and communicative dimensions:

Beyond simply inviting participation, platforms also play a crucial role in disciplining it. TikTok’s algorithmic curation is not neutral—it selectively elevates or suppresses content based on opaque moderation practices and community guidelines (Bhandari and Bimo, 2022; Zhang and Liu, 2021). As such, the visibility of meme-based rituals is shaped by more than user enthusiasm; it is filtered through layers of platform governance that reward certain forms of performativity while sidelining others. This algorithmic gatekeeping helps construct the normative boundaries of memetic behavior, determining which participatory rituals are celebrated, commodified, or quietly erased. In this sense, audience performance is not only shaped by community expectations but also by infrastructural biases built into digital ecosystems.

At the same time, the response from cinemas—warnings, restrictions, and baffled statements—highlights an intergenerational cultural gap (Aulbach, 2025; Milmo et al., 2025). Traditional theatrical etiquette presumes silence and deference to the screen; the participatory logic of meme culture demands reaction and feedback. For industry stakeholders, this creates tension: while meme engagement can drive buzz and box office sales, it may also disrupt standard business models and audience expectations.

As memetic engagement continues to spill into physical venues, cinema infrastructure itself may face increasing pressures to adapt. Traditional theaters are designed for immersive, uninterrupted viewing, privileging silence, darkness, and fixed seating. These conditions often clash with the chaotic, performative energy of meme rituals that thrive on visibility, reactivity, and social signaling. Much like how theaters began offering “sing-along” or “interactive” screenings of musicals such as Frozen or The Greatest Showman, we may see future adaptations that embrace controlled memetic participation—so-called “meme-enabled showings” that explicitly allow or even choreograph collective responses. Such adjustments signal not only new forms of audience management but also a rethinking of the theater as a semi-public platform designed for co-authorship, not just consumption. In this sense, the Minecraft event is not just a quirky anecdote but a flashpoint in the ongoing negotiation between legacy media institutions and emergent cultural practices.

The implications extend beyond film. If youth audiences increasingly expect media to provide moments for communal enactment—whether through memes, chants, or challenges—producers may begin designing content with these responses in mind. What begins as spontaneous memetic performance may soon become a coded expectation, shaping both narrative structure and marketing strategy. The “chicken jockey” phenomenon thus offers a glimpse into the future of participatory spectacle, where generational media habits are rewriting the rules of reception.

7 Memetic performance as media ritual: implications for theory and design

The “chicken jockey” phenomenon crystallizes several important shifts in how media is experienced, produced, and theorized in the digital age. At its core is the transformation of audiences from passive viewers into active co-participants (Jenkins, 2006) but now extended into physical space. The theater, long a site of controlled, unidirectional storytelling, is recast as a participatory arena (Pett, 2021) where meme logic and audience response co-create meaning in real time.

This shift invites reconsideration of key concepts in media theory. Traditional reception studies focus on interpretation, assuming the audience decodes meaning privately or at most discusses it after viewing. By contrast, meme spectacles like the Minecraft “chicken jockey” chant exemplify performative reception: viewers enact their interpretation communally and visibly, sometimes in synchrony with others worldwide. These performances blur the boundaries between viewing, reacting, and producing.

They also suggest a movement toward what could be termed meme-based audience ritual. Unlike the relatively stable, text-bound rituals of cult cinema (e.g., The Rocky Horror Picture Show) (Hills and Sexton, 2015; Mathijs and Sexton, 2011), meme rituals are volatile, decentralized, and rapidly diffused. They emerge through online signaling, proliferate via algorithmic platforms, and manifest offline in spontaneous, replicable formats. Their symbolic content is often absurd, but their performative structure is highly disciplined: a recognizable cue triggers a predictable collective behavior, reaffirming group identity through repetition.

This presents a paradox for cultural producers. On the one hand, meme rituals offer unparalleled opportunities for engagement. Films that become meme events gain extended lifespans, free publicity, and generational relevance. On the other hand, the unpredictability of meme culture makes it difficult to control. Studios can plant memeable moments, but they cannot determine how or when audiences will take them up—or whether those moments will overshadow the narrative or compromise the viewing experience for others.

Some studios have already begun to adapt to this logic, designing scenes and trailers with “memeability” in mind. Rather than focusing solely on coherent narrative arcs, producers now consider the memetic afterlife of specific moments—brief phrases, exaggerated visuals, or absurd juxtapositions that might be isolated, clipped, and recontextualized across platforms. This trend—what might be called “meme baiting”—shifts creative emphasis toward modular, platform-optimized storytelling. This reflects a broader platformization of cultural production, in which content is increasingly engineered for shareability rather than depth (Nieborg and Poell, 2018). The implications are profound: the story becomes secondary to the snippet, and audience participation is pre-scripted by expectation rather than emergence.

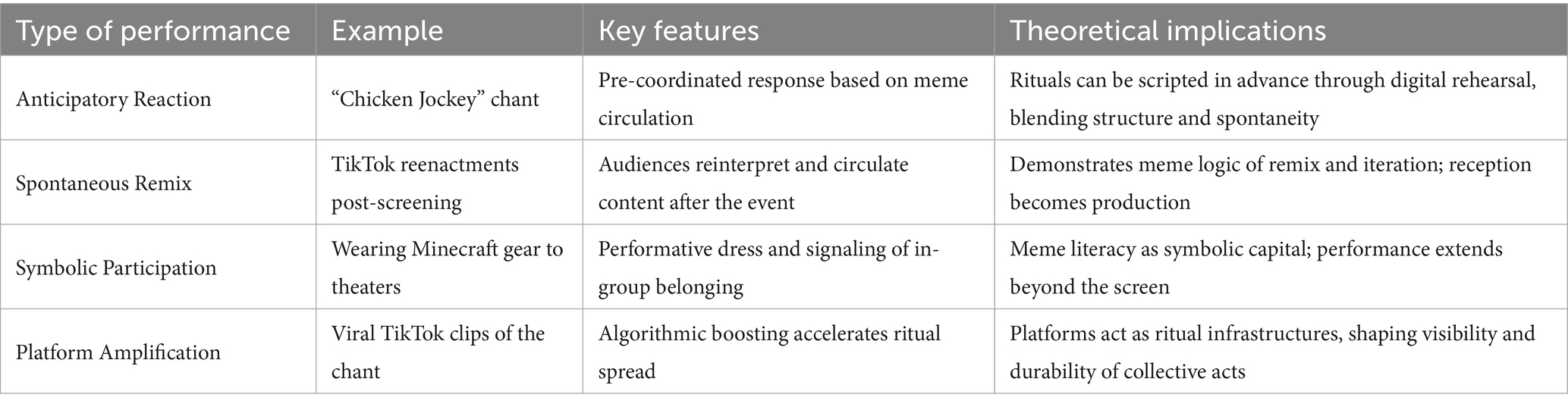

Table 3 categorizes the main types of memetic performance evident in this phenomenon, distinguishing anticipatory, spontaneous, symbolic, and platform-amplified behaviors as overlapping but distinct modes of ritual:

There are also implications for authorship and content design. As memes take on the role of structuring affective responses, filmmakers may begin to reverse-engineer scenes around potential meme triggers. The creative process shifts from crafting coherent arcs to engineering “moments”: quotable lines, absurd images, or cameo appearances designed to be clipped and shared. In this logic, narrative becomes modular, and meaning is constructed post hoc by audiences.

Moreover, this memetic turn in media reception raises questions about cultural literacy and exclusion. Understanding a meme often requires prior exposure to a symbolic lexicon—one that is generational, platform-specific, and evolving. Those unfamiliar with the “chicken jockey” meme might have found the theater eruptions confusing or alienating (Aulbach, 2025). As such, media experiences become increasingly stratified, with insiders and outsiders demarcated not by plot comprehension but by meme fluency. Meme fluency often operates as contested cultural capital, marking not just symbolic belonging but also social differentiation within online communities (Nissenbaum and Shifman, 2017). This reinforces the stratifying effects of symbolic literacy in participatory rituals, such as the “chicken jockey” chant.

Meme literacy, like any form of cultural capital, structures inclusion and exclusion in contemporary media rituals. Drawing on Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984), we can understand symbolic fluency with memes as a resource that enables full participation in shared cultural events—events that increasingly depend on recognizing, interpreting, and performing digital codes (Nissenbaum and Shifman, 2017). Those unfamiliar with a meme’s history, tone, or context may find themselves excluded from the emotional intensity or social cohesion the ritual enables. In this way, memes operate not only as media but as social filters, reinforcing distinctions between those who are “in on the joke” and those who are not.

From a theoretical standpoint, this signals a hybridization of ritual, spectacle, and algorithmic culture. Meme events like the Minecraft chant are shaped not only by audience creativity but also by the logics of platforms that prioritize shareability, brevity, and virality. The chant is not merely a cultural act; it is an optimized unit of engagement. Understanding such phenomena thus requires interdisciplinary tools, including media theory, performance studies, platform analysis, and digital anthropology, which must work in concert to grasp the dynamics at play.

In sum, the Minecraft case challenges prevailing assumptions about cinematic experience, audience behavior, and media meaning-making. It suggests a future in which films are not just watched but enacted, not just interpreted but performed—where the meme is both message and medium, and the audience is both choir and co-author.

8 Conclusion

The “chicken jockey” phenomenon that accompanied the release of the Minecraft movie in 2025 offers a revealing case study in the evolving relationship between meme culture and media experience. What might have once been seen as an isolated fan reaction was in fact a ritualized, memetic performance—rooted in shared digital knowledge, amplified by social platforms, and enacted in physical space. It marked a moment where audience behavior was no longer reactive but generative, transforming a scripted scene into a viral, participatory spectacle.

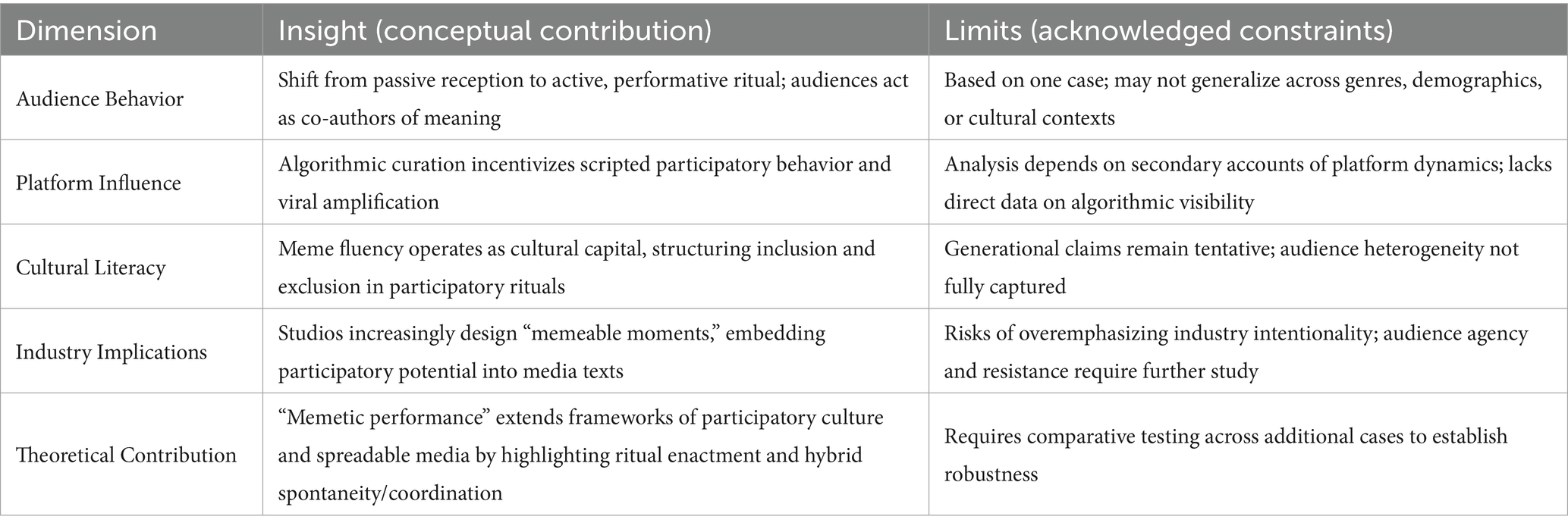

As a final summary, Table 4 consolidates the key theoretical and empirical insights drawn from the “chicken jockey” phenomenon, mapping its implications for audience behavior, platform culture, and media design.

This paper has traced how that transformation unfolded, beginning with the memetic logic of Minecraft as a platform for shared symbolic content, and culminating in the collective outburst triggered by a single in-game reference. In examining this event through the lenses of memetic transmission, participatory culture, and media ritual, we see not only a novel mode of audience engagement but a broader shift in the media landscape. Memes now serve not only as post-hoc commentary but as frameworks for live, communal meaning-making—turning film screenings into semi-scripted social performances.

Such developments have significant implications. They challenge traditional notions of authorship, narrative coherence, and cinematic etiquette. They invite cultural producers to consider the memetic potential of their content not just in digital afterlives but in real-time audience behavior. And they raise questions about the cultural competencies now required to fully participate in media experiences: recognition of symbolic cues, willingness to perform, and fluency in digital-native codes.

While it may be tempting to treat the “chicken jockey” riot as a novelty or aberration, it is better understood as an index of broader cultural change. It reflects how digitally native audiences, raised in algorithmic environments, approach media as something to be performed as much as consumed. In theorizing this phenomenon as memetic performance, this paper contributes a conceptual framework for understanding how audience rituals are being reshaped by the interplay of platform infrastructures, symbolic fluency, and social participation. As memes continue to shape not only what we see but how we behave in response, scholars and practitioners alike will need new tools to account for this participatory, performative, and often chaotic convergence of culture, content, and community.

This study employs a conceptual approach grounded in interpretive case analysis, drawing on secondary data and cultural texts to theorize the role of memetic performance in audience rituals and media spectacles. Despite its conceptual scope, this paper focuses on a single, highly specific case: the participatory eruption surrounding the “chicken jockey” moment during the 2025 Minecraft movie release. While this event is richly illustrative of broader shifts in audience behavior, memetic culture, and platform-mediated ritual, it may not be representative of all media experiences or demographic groups. The phenomenon analyzed here is most visible among younger, digitally native participants, while acknowledging a wider, multi-generational audience context, culturally situated (within Anglo-American and platform-native contexts), and temporally bounded (coinciding with the theatrical debut of a major franchise film). As such, the applicability of memetic performance as a framework should be understood in relation to similar algorithmically amplified, highly referential, and digitally networked settings. Future research could extend this analysis across other genres (e.g., horror, K-pop concerts, esports), different age cohorts, or non-Western contexts to test the limits and adaptations of meme-based audience rituals in varied sociocultural environments.

9 Epilogue: future rituals in meme-inflected media

The “chicken jockey” phenomenon suggests that meme logics may increasingly inform how media is both produced and received. Already, studios embed “memeable moments” into trailers and scripts, anticipating online circulation. Cinema venues, too, have begun experimenting with interactive or themed screenings, hinting at possible accommodations for meme-driven rituals. In this sense, future audience participation may be less about spontaneous disruption and more about managed integration of memetic performance into the entertainment experience.

Platforms also play a central role in this trajectory. Algorithmic curation not only amplifies rituals after they occur but also shapes expectations in advance by surfacing speculative reactions, rehearsals, and calls to action. This feedback loop blurs the line between audience and industry, where ritual is co-produced across both cultural and infrastructural levels.

Rather than a radical break, such developments represent a continuation of the dynamics observed in the Minecraft case: memes functioning simultaneously as symbolic codes, participatory scripts, and design logics for collective performance.

Author contributions

DM: Resources, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author used ChatGPT Plus and Grammarly Premium to improve the language, style, and structure of the manuscript. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agius, K., and Lerviks, B. L. (2024). How emergent gameplay in Minecraft brings its community closer. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5006399

Allgood, L. (2015). Review: chicken jockey. The Pinion. Available online at: https://mhspinion.com/opinion/2025/05/13/chicken-jockey/ (Accesed July 10, 2025).

Andrew, S. (2022). ‘Gentleminions’: why TikTok teens are wearing suits to ‘minions: the rise of Gru’. Available online at:https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/06/entertainment/gentleminions-rise-of-gru-tiktok-cec (Accessed June 7, 2025).

Apperley, T. (2015). “Glitch sorting: Minecraft, curation and the Postdigital” in Postdigital aesthetics: Art, computation and design. eds. D. M. Berry and M. Dieter (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 232–244.

Aulbach, D. (2025). What is ‘chicken jockey?’ Learn about ‘a Minecraft movie’ phrases fans are shouting in theaters. The Today Show. Available online at: https://www.today.com/parents/family/chicken-jockey-minecraft-movie-rcna200183

Austin, B. A. (1981). Portrait of a cult film audience: the rocky horror picture show. J. Commun. 31, 43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1981.tb01227.x

Bhandari, A., and Bimo, S. (2022). Why’s everyone on TikTok now? The algorithmized self and the future of self-making on social media. Social Media + Society 8:20563051221086241. doi: 10.1177/20563051221086241

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brown, H. (2022). The surprising power of internet memes. BBC. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220928-the-surprising-power-of-internet-memes (Accessed July 20, 2025).

CaptainSparklez. (2011). "revenge" - a Minecraft parody of usher's DJ got us Fallin' in love (music video). Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cPJUBQd-PNM (Accessed July 15, 2025).

Cervi, L., and Divon, T. (2023). Playful activism: memetic performances of Palestinian resistance in TikTok# challenges. Social Media+ Society 9:20563051231157607.

Couldry, N. (2012). Media, society, world: Social theory and digital media practice. London: Polity.

Cutting, J. E. (2021). Movies on our minds: The evolution of cinematic engagement. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Denisova, A. (2019). Internet memes and society: Social, cultural, and political contexts. London: Routledge.

Fahy, C., and Oxenden, M. (2022). ‘Why is everyone wearing suits?’: #GentleMinions has moviegoers dressing up. New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/08/style/minions-gentleminions-tik-tok-trend.html (Accessed July 20, 2025).

Garrelts, N. (2014). Understanding Minecraft: Essays on play, community and possibilities. London: McFarland.

Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. New York, NY: Yale University Press.

Hills, M., and Sexton, J. (2015). Cult cinema and technological change. New Rev. Film Television Stu. 13, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/17400309.2014.989007

Huszár, F., Ktena, S. I., O’Brien, C., Belli, L., Schlaikjer, A., and Hardt, M. (2022). Algorithmic amplification of politics on twitter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119:e2025334119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2025334119

IMDb. (2025). A Minecraft Movie. Available online at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3566834/ (Accessed July 2, 2025).

Ismail, U., and Khan, M. (2023). K-pop fans practices: Content consumption to participatory approach. Global Digital Print Media Review 6, 238–250.

Ito, M., Okabe, D., and Tsuji, I. (2012). Fandom unbound: Otaku culture in a connected world. London: Yale University Press.

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., and Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Kinkade, P. T., and Katovich, M. A. (1992). Toward a sociology of cult films: reading rocky horror. Sociol. Q. 33, 191–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1992.tb00371.x

Lane, H. C., and Yi, S. (2017). “Chapter 7 - playing with virtual blocks: Minecraft as a learning environment for practice and research” in Cognitive development in digital contexts. eds. F. C. Blumberg and P. J. Brooks (London: Academic Press), 145–166.

Milli, S., Carroll, M., Wang, Y., Pandey, S., Zhao, S., and Dragan, A. D. (2025). Engagement, user satisfaction, and the amplification of divisive content on social media. PNAS Nexus 4:pgaf062. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf062

Milmo, D., Pulver, A., and Ibrahim, M. (2025). Cinemas threaten Minecraft movie audiences over ‘chicken jockey’ TikTok trend. The Guardian. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2025/apr/09/cinemas-minecraft-movie-chicken-jockey-tiktok-trend (Accessed June 10, 2025).

Milner, R. M. (2018). The world made meme: Public conversations and participatory media. London: MIT Press.

Miltner, K. M. (2018). “Internet memes” in The SAGE handbook of social media. eds. J. Burgess, T. Poell, and A. E. Marwick, vol. 55 (London: Sage Publications), 412–428.

Milton, A., Ajmani, L., DeVito, M. A., and Chancellor, S. (2023). “I see me Here”: mental health content, community, and algorithmic curation on TikTok proceedings of the 2023 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Hamburg, Germany. 480, 1–17. doi: 10.1145/3544548.3581489

Newman, J. (2019). “Minecraft: user- generated content” in How to play video games. eds. P. Matthew Thomas and B. H. Nina (New York, NY: New York University Press), 277–284.

Nguyen, J. (2016). Minecraft and the building blocks of creative individuality. Configurations 24, 471–500. doi: 10.1353/con.2016.0030

Nieborg, D. B., and Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media Soc. 20, 4275–4292. doi: 10.1177/1461444818769694

Nissenbaum, A., and Shifman, L. (2017). Internet memes as contested cultural capital: the case of 4chan’s /b/ board. New Media Soc. 19, 483–501. doi: 10.1177/1461444815609313

Pett, E. (2021). Experiencing cinema: Participatory film cultures, immersive media and the experience economy. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Phillips, W., and Milner, R. M. (2021). You are here: A field guide for navigating polarized speech, conspiracy theories, and our polluted media landscape. London: MIT Press.

Raz, J. (1983). Audience and actors: A study of their interaction in the Japanese traditional theatre. London: E. J. Brill.

Romano, A. (2025). The unlikely origins of a (literal) blockbuster at the box office. Vox. Available online at: https://www.vox.com/culture/408531/minecraft-movie-memes-box-office-explained (accessed May 12, 2025).

Simone, G. (2017). Tokyo geek's guide: Manga, anime, gaming, cosplay, toys, Idols & More-the Ultimate Guide to Japan's otaku culture. New York, NY: Tuttle Publishing.

Tran-Nguyen, L. (2025). K-pop fandoms through Durkheim’s Lens. California Sociol. Forum 7, 87–97. Available online at: https://journals.calstate.edu/csf/article/view/6190

Trillò, T. (2024). “PoV: You are reading an academic article.” the memetic performance of affiliation in TikTok’s platform vernacular. New Media Soc. 22:14614448241290234. doi: 10.1177/14614448241290234

Walsham, G. (2006). Doing interpretive research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 15, 320–330. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000589

Weiß, A.-N., Primig, F., and Szabó, H. D. (2025). ‘Eyo, mixed girl check’: the commodification of embodied performance in the# mixedgirlcheck trend on TikTok. Platforms Soc. 2:29768624251332482. doi: 10.1177/29768624251332482

Zhan, J. (2025). Is a Minecraft movie becoming a blocky horror pixel show? Vulture. Available online at: https://www.vulture.com/article/chicken-jockey-meme-minecraft-movie-explained.html (accessed April 9, 2025).

Keywords: memes, audience participation, media ritual, participatory culture, digital platforms, Minecraft, TikTok, participatory media

Citation: Madsen DØ (2025) Memetic performance and participatory spectacle: audience ritual in the 2025 Minecraft movie. Front. Commun. 10:1699245. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1699245

Edited by:

Ufuoma Akpojivi, University of the Witwatersrand, South AfricaReviewed by:

Pedro Alves da Veiga, Universidade Aberta, PortugalAngelo Puccia, University of Cordoba, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Madsen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dag Øivind Madsen, ZGFnLm9pdmluZC5tYWRzZW5AdXNuLm5v

Dag Øivind Madsen

Dag Øivind Madsen