- 1Department of Journalism and Digital Media, Zarqa University, Zarqa, Jordan

- 2College of Communication and Media, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

University institutions are being put to the test by crises, particularly when social media presents both positive and negative perspectives. This study examines the impact of leadership communication style on employees’ online communication behaviors and employee engagement at Jordanian institutions during times of crisis. This study develops an integrated framework that combines relational and situational perspectives to explain employee communication behavior. It is based on social exchange theory and situational crisis communication theory. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 426 academic and administrative employees from six Jordanian institutions to collect data, which was then analyzed using SmartPLS (SEM). Results show that a leader’s communication style improves employee engagement by promoting good social media behaviors while stifling those that are adverse, such as disseminating rumors and public complaints. It emerged that employee engagement becomes the primary mechanism by which leadership’s communication exerts an effect on employee digital voice during times of crisis. In addition to enhancing situational crisis communication theory by introducing employees as proactive digital ambassadors in organizational crisis planning, the research makes theoretical contributions by using social exchange theory to show how leader-employee exchanges in reciprocity are transformed into online behaviors.

1 Introduction

Global health outbreaks like the COVID-19 pandemic, reputational scandals, and sectoral disruptions are only a few examples of the crises that have become unavoidable in organizational life in the current digital age. According to Alsharairi et al. (2025), social media platforms have changed the nature of crisis communication by necessitating leaders to engage in transparent, dialogic, and responsive stakeholder interactions, rather than delivering top-down communications. Through digital channels, which serve as both information outlets and environments for identity building, sensemaking, and comfort during difficult times, employees are increasingly expecting leaders to deliver fast and reliable updates (Bindel Sibassaha et al., 2025). According to recent research, employee emotional states and communicative preferences—in particular their degree of engagement—are significantly influenced by a leader’s communication style, whether it be transparent, honest, or sympathetic (Barron Garrett, 2024; Tao et al., 2022). Nevertheless, although several communicative aspects of leadership style are discussed in relation to work-related leader–follower interactions, and leadership communication, limited studies have examined the impact of leadership communication on employees’ social media use during crises.

Employee communication behaviors, as a primary consequence of public relations practices, have been extensively examined in across various external public settings, including corporate, and global contexts, but significant questions remain unanswered. However, examining how leaders style their internal public or maintain their behaviors in times of crisis requires further study (Eichenauer et al., 2022). In contrast, there has been very little focus on internal dynamics, or how employees engage with and exaggerate leaders’ crisis messages in digital environments (Ravazzani et al., 2024). Furthermore, insufficient is known about whether employee engagement mediates the link between leadership style and employee online communicative behaviors during crisis situations, even though it has been generally acknowledged as a crucial outcome of leadership communication (Mphaluwa et al., 2025). Another gap is that despite evidence that employees engage in both positive and negative behaviors, such as spreading criticism, spreading rumors, or sharing positive behaviors (Zhou et al., 2023), including promoting encouraging messages, addressing misinformation, and maintaining the organization’s reputation. Neglecting this duality contributes to the explanation of the gaps observed in earlier studies on online employee communication behaviors. Theoretical integration of SET and SCCT is essential. To resolve the inconsistent findings in the literature, Cropanzano et al. (2017), SET emphasized that open communication from leaders creates views of involvement, which increases commitment and positive employee communication behaviors. In turn, SCCT illustrates how the framing of crisis messages affects employee reactions and responsibility attributions (Coombs, 2021). By combining these perspectives, employees can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the significance of leadership style and how engagement is a psychological process that connects leadership communication to employee positive and negative communication behaviors in online settings (Santoso et al., 2022a). Studies found substantial impacts of leadership transparency on employee engagement, whereas others (van Zoonen et al., 2024) show weaker or context-dependent links. Jordan’s higher education system provides an experimentally rich environment for filling in these gaps. Jordan’s public and private universities have faced a number of challenges in the past few years, including as severe financial difficulties, frequent student demonstrations, and the suspension of academic activity during the COVID-19 epidemic. Students, faculty, and administrative personnel use social media extensively to discuss institutional policies, raise support, and spread both good and negative narratives (AlDreabi et al., 2023). However, previous research in Jordan has tended to focus on digital communication from a managerial or external perspective, and did not sufficiently explore the various ways in which leadership communication styles impact employees’ digital behaviors in times of crisis. Building a theoretically sound and practically applicable model is made possible by using SET and SCCT to this situation.

Therefore, using employee engagement as a mediating mechanism, this study examines how leadership communication style affects employees positive and negative communicative behaviors on social media during crises at Jordanian institutions. The study makes a theoretical contribution by defining the dual nature of employee communicative behaviors in digital contexts, reframing engagement as a mediator rather than as a result, and incorporating SET and SCCT into crisis communication research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Leadership communication style

Leadership communication styles are commonly described as transformational, authentic, and supportive, yet the core scholarly interest has shifted toward how such styles shape employees’ experiences during high uncertainty (Walker, 2025). It has been shown that transformational communication, marked by vision sharing and individualized consideration, has reduced ambiguity, sustained morale, and encouraged constructive employee voice during the COVID-19 period in higher education and service settings, although effects have varied across contexts and channels (Santoso et al., 2022b; van Zoonen et al., 2024). Leadership communication has been linked to perceived openness and trustworthiness in online settings, which has been associated with increased relational trust and greater sensemaking by employees when reputational pressure is considerable in service and industrial settings (Lee, 2022). Leadership communication has been identified to promote psychological safety and perceived importance, and results have been associated with increased motivation to engage in advocacy and corrective discourse in organizational networks (Thelen and Men, 2022). Several studies have viewed leadership style as a static determinant, and its integration into specific online communication behaviors has not been adequately explored (Alyaqoub and Alsharairi, 2020; Santoso et al., 2022a). The microdynamics involved in communicating about crises, such as timeliness, dialogic responsiveness, acknowledgement of uncertainty, and correction of misinformation, have not been systematically integrated with leadership style in one integrated frame (Kim, 2023; Lee et al., 2022). Moreover, leaders’ ambiguous or inconsistent social media updates often decrease engagement and draw doubting or critical responses from employees (Lee et al., 2024).

Despite this, these mechanisms are not sufficiently specified beyond general clues at dwindling trust (Chevalier et al., 2025; van Zoonen et al., 2024). Research on higher education in the Middle East has been remarkably scarce, which leaves unsolved issues about how leadership communication translates into employees’ digital communication behaviors in universities that are highly active on social media and feature hybrid governance. Accordingly, while stylistic taxonomisations are frequently highlighted, employees’ communicative behaviors in networks involving crises appear to depend upon specific signals that have not been fully integrated into leadership communicative models.

2.2 Employee engagement

Employee engagement is a positive work-related condition involving vitality, motivation, and engagement. The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale and other abbreviated adaptations have been commonly employed to measure these three factors and have displayed strong effects across cultures and occupations, such as contexts involving research in organizational communication (Schaufeli et al., 2006; Arana-Medina et al., 2023). It has been suggested that transparent and supportive leader communication elevates vigor by supplying direction and efficacy cues, fosters dedication by aligning employees with shared purpose, and sustains absorption by reducing noise and clarifying task boundaries in volatile conditions (Eva et al., 2024). Quantitative evidence from public and private organizations has indicated that employees report higher engagement when supervisors use transparent, responsive, and credible messaging, and that this elevation is associated with more consistent participation in digital initiatives during disruptions (Santoso et al., 2022a).

Nevertheless, gaps remain visible. Engagement has often been modeled as an endpoint rather than a proximal psychological condition shaping how employees communicate about their organization on social media. Little attention has been paid to whether the three dimensions contribute differentially to digital expression (Tao et al., 2022). For example, vigor may energize rapid sharing of official updates, dedication may anchor defense of organizational decisions, and absorption may encourage deep involvement in corrective discussions (Qin, 2025). However, such differentiated pathways have rarely been tested. Studies of remote and hybrid work further indicate that engagement can fluctuate with digital overload and work–life interference, which in turn can tilt employee communication toward either constructive advocacy or fatigued criticism, but integrative designs linking these dynamics to leadership messaging are scarce (Zhou et al., 2023). The current literature suggests strong links between leader communication and engagement, leaving unanswered how the three engagement facets map onto specific forms of employee talk in organizational social media during crises.

2.3 Communication behavior on social media

Employee communication on social media has been examined as a set of observable practices in public and semi-public platforms (Alsharairi et al., 2022). A two-part structure has been increasingly acknowledged. Positive behavior has included sharing and amplifying institutional messages, defending organizational reputation, and correcting misinformation. Negative behavior has included public complaints, rumor propagation, and the circulation of demoralizing narratives that can intensify reputational risk (Oloba et al., 2024). Evidence demonstrates that supportive internal climates and clear crisis narratives are associated with greater advocacy and corrective talk. In service, industrial, and government-related contexts, transparent or protective messaging has also been linked to negative posting and the dissemination of rumors (Mirbabaie et al., 2023; Nuortimo et al., 2024). Research on encouraging speech and employee advocacy has also shown that dialogic cues from managers are linked with more positive digital expression in both internal and external channels, with cultural differences noted across national contexts (Alsharairi et al., 2023; Thelen and Men, 2022).

However, studies has frequently seen digital communication as a one-dimensional notion, ignoring significant differences between positive and negative behaviors. Many surveys have aggregated posts, likes, and comments without coding valence or intent, making it difficult to compare how leadership communication relates to amplification versus complaint. Crisis-specific designs have also been limited, and sectoral coverage has leaned toward corporate and public administration samples, with higher education often considered peripherally (Lengyel et al., 2019). Jordanian universities, where students, staff, and faculty actively debate policy online, have rarely been foregrounded despite their high relevance for internal crisis communication (Alsharairi and Jamal, 2021). Research indicates that digital communication became central to the continuity of academic work and the negotiation of institutional identity during the pandemic in Jordan. However, the link between leadership style and employee talk is a positive–negative spectrum that has not been examined with fine-grained measures in this setting (Alyaqoub et al., 2024; AlDreabi et al., 2023).

As a result, three consistent gaps emerge from the literature. First, integrative studies that connect leadership communication style, the three-facet structure of engagement, and the two-valence structure of employee social media behavior within a single crisis-sensitive model remain scarce. Second, higher education in the Middle East, particularly in Jordan, has not been adequately represented, despite distinctive governance norms and high social media activity. Third, measurement strategies often conflate employee communication into single indices, obscuring the distinction between advocacy and correction on one hand and complaints and rumors on the other.

These gaps can be better understood through established theoretical perspectives between SCCT (Coombs, 2021). This is because positive encouragement, responsible collaboration, and message framing direct stakeholder reactions. Thus, when considered collectively, these theories explain why employee behavior on social media during times of crisis cannot be seen as random noise, but rather as a structured response influenced by exchange quality and the fit of the crisis message (Coombs, 2021; Cropanzano et al., 2017).

3 Theoretical framework

Within the context of the current study, there is precedence given to the lenses of two theories, which fit in with the structure and context of the crisis. Speaking particularly about social exchange theory, it explains social exchange with regard to tangibles and intangibles as a process of social exchange. Fundamentally, social exchange theory suggests that there is social exchange between employees and their leadership, generating trust, friendship, and loyalty (Wang et al., 2022). Social exchange is a process in which exchange partners reciprocate each other. Accordingly, high-quality leadership behavior, as well as leadership relationships, foster positive associations about employee communication behavior. Leadership qualities, ethics, support, positivity, and relationship behavior are crucial for efficient management, thereby enhancing leadership, trust, and relationships with social exchange (Chen and Sriphon, 2022). Therefore, a positive relationship between leadership and employees will influence them to achieve objectives, improve performance, and communicate positively in a crisis. The SCCT is concerned with making decisions regarding crisis responsibility, which has a significant impact on people’s perceptions and behavior toward the organization’s image and reputation. Responsible for the relationship between employee engagement, online behaviors, and leadership style for the crisis (Coombs, 2021; Cropanzano et al., 2017; Mazzei, 2022; Thelen and Men, 2022).

3.1 Social exchange theory (SET)

Social exchange theory is one of the most popular conceptually based frameworks in management studies, as well as in other areas such as sociology, social psychology, and management science. One major shortcoming, however, for social exchange theory is its failure to provide enough theoretical specificity. Researchers based on social exchange theory, for example, have the capacity to explain many observed social occurrences from an after-the-fact point of view, yet their capacity to provide legitimate, inadvance predictions on workplace behavior is significantly constrained Cropanzano et al., 2017. According to social exchange theory, trust and dedication are fostered through reciprocal interactions that involve perceived advantages, fairness, and relational involvement. Within organizational communication, supportive and transparent leader behavior has been shown to generate perceptions of justice and care that employees reciprocate through constructive attitudes and behaviors, including communication-related involvement in digital environments (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Men et al., 2022; Thelen and Men, 2022). In crisis conditions, timely acknowledgment of uncertainty, dialogic responsiveness, and clarity from leaders function as high-value signals in the exchange, strengthening engagement as a proximal psychological state that reflects vigor, dedication, and absorption (Santoso et al., 2022b; Liu-Lastres et al., 2023). When engagement is strengthened, employees have been observed to participate more consistently in organizational digital initiatives, to amplify official messages, and to support corrective information flows. When perceived transparency or fairness is low, disengagement and skeptical talk tend to surface, including critical posting or rumor sharing that travels rapidly on social media during crises (van Zoonen et al., 2024; Oksa et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Therefore, SET explains why leadership communication is a precursor to engagement and is closely bound up with the valence of employees’ social media expression in turbulent periods.

3.2 Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT)

Situational Crisis Communication Theory argues that stakeholder attributions of responsibility guide evaluations and that communication should be matched to crisis type and intensifying factors to maintain legitimacy and trust. Message framing, responsibility acknowledgement, and corrective action influence audience responses in crises (Coombs, 2021; Mazzei, 2022). Although SCCT has traditionally focused on the external public, internal stakeholders can be read through the same logic in hybrid roles as employees and digital actors. Evidence from internal crisis communication shows that accommodative strategies, which create security, sustain belonging, and activate desired behaviors, are associated with more supportive internal climates and with stronger employee advocacy online during disruptions, whereas opaque or defensive messaging correlates with critical posting and rumor propagation (Mazzei, 2022; Liu-Lastres et al., 2023; Thelen and Men, 2022). SCCT consequently clarifies how leadership communication style in crisis channels the direction of employees’ digital behaviors, making constructive amplification more likely when the message strategy fits the situation and responsibility is addressed.

3.3 Integration of SET and SCCT

The theories are complementary rather than redundant. Social Exchange Theory illuminates the relational and psychological mechanisms that connect leadership communication to employee engagement by emphasizing reciprocity and perceived investment. Situational Crisis Communication Theory highlights the situational contingencies that determine how engagement is enacted in digital communication by emphasizing message–situation fit and responsibility management (Aslam et al., 2024). When integrated, SET explains why supportive leadership generates reciprocity in the form of engagement, while SCCT explains how crisis framing and corrective action shape whether engagement manifests as positive advocacy and correction or as negative complaint and rumor in social media spaces (Coombs, 2021; Cropanzano et al., 2017; Thelen and Men, 2022; van Zoonen et al., 2024). This integration advances a view in which employee digital behavior during crises is patterned by both exchange quality and crisis message quality.

3.4 Theoretical gap

Despite clear relevance, SET and SCCT have rarely been combined to explain internal digital communication in crises. Applications of SET have often treated engagement as an endpoint rather than a proximal state that conditions digital expression, while SCCT work has prioritized external publics and corporate reputation. Few studies map the differentiated features of leader crisis messaging together with engagement and valenced digital behavior in a single model, and higher education in the Middle East in general and Jordanian universities in particular, remains underrepresented despite intensive social media use and hybrid governance norms (AlDreabi et al., 2023; Mazzei, 2022; Coombs, 2021). The present study contributes by bringing these theories together in a novel sector and region, extending theoretical understanding of leadership communication, employee engagement, and social media behavior during crises.

4 Research hypotheses development

Based on the reviewed literature and the theoretical foundations, this section develops the hypotheses that guide the current study, explaining the expected relationships among leadership communication style, employee engagement, and communication behavior on social media during crises. Drawing on Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), the hypotheses are formulated to reflect how relational mechanisms and crisis communication strategies jointly influence employees’ engagement and their communicative behaviors within the context of Jordanian universities.

4.1 Leadership communication style and employee engagement

According to SET, leaders’ encouraging and open communication is a relational engagement that promotes reciprocity, improving employees’ feelings of vigor, commitment, and integration (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Leadership communication and employee engagement are effectively entrenched in a social paradigm of an organization in which these two elements are mutually embedded in an organization (Makowski, 2023 sustainability). Inspirational leadership and communication have a positive act in employee engagement between leadership and employees (Men et al., 2022; Santoso et al., 2022b). For example, Perceived Organizational Support and Leader Member Exchange have uncovered a motivating factor in employee engagement for Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (Giallouros et al., 2024). This aligns with Mazzei’s (2022) point regarding creating and developing social engagement for successfully engaged leadership. Additionally, literature suggests that leadership communication and open communication enable production-oriented leaders to increase their employees’ engagement. Leaders who are transparent and consistent in communication are likely to be trusted by their followers. In turn, trust indirectly leads to employee engagement through perceived leadership in communication (Heuss and Datta, 2023).

Consequently, leaders who communicate their vision, identify difficulties, and exhibit empathy in times of crisis send signals of justice and concern that have been demonstrated to increase involvement in various organizational situations. Leader behaviors influence communication among employees and foster positive relationships within the organization. While some studies show that leadership communication significantly improves engagement (Thelen and Men, 2022), other research indicates that leadership style may not be sufficient to avoid disengagement in challenging situations completely (Oksa et al., 2021). The study forecasts the following hypothesis in light of these considerations:

H1: Leadership communication has a positive relationship with employee engagement in a crisis.

4.2 Employee engagement and communication behavior on social media

In recent years, as companies have begun to recognize the importance of engaged employees for direct business outcomes, such as improved performance, innovation, and productivity (Kwarteng et al., 2024), employee engagement has recently proved to be an essential concept, which has played a crucial role in influencing organizational efficiency and competitiveness (Deepalakshmi et al., 2024). Prior to the new context regarding employee engagement and its importance in overall communication contexts in an organization, employee communication behavior in crisis situations had long been identified to reveal its consequence in employee engagement (Alsharairi et al., 2023; Nuortimo et al., 2024). For instance, engaged employees have more favorable communication behavior than disengaged employees. It is, therefore, inferred that there is a relationship between high employee engagement and favorable communication behavior, which is favorable/positive. Conversely, negative communication behavior, now called negative behavior, is defined by employees speaking badly about their organization to outsiders. However, studies also show that dissatisfied employees may disseminate undesirable talks, critiques, and rumors (Mirbabaie et al., 2023). Theoretically, engaged workers might function as “online advocates” in times of crisis, supporting institutional legitimacy and organizational narratives (Coombs, 2021; van Zoonen et al., 2024). According to SET, social media participation is favorably correlated with perceived managerial effort. According to earlier research, motivated workers encourage constructive online communication practices (Zhou et al., 2023). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Employee engagement is favorably correlated with proactive social media communication practices during times of crisis.

H3: There is an adverse relationship between employee engagement and negative online communication behaviors during times of crisis.

4.3 Leadership communication style and communication behavior on social media

Effective leadership communication is crucial for preserving stakeholder trust and organizational stability in a crisis (Koritarov and Dimitrakieva, 2024). In this sense, leadership communication is defined as the process through which organizational leaders connect with and influence stakeholders (Lemoine et al., 2024). This suggests that leadership communication plays a critical role in how employees behave in times of crisis. For example, in a crisis, employees are more likely to support and spread good information about their company on social media when managers communicate in an open, accountable, and responsive manner (Mazzei, 2022; Thelen and Men, 2022). Conversely, mistrust is fostered by defensive or unclear communication, which results in negative online actions during emergency situations (Oksa et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). It is crucial to investigate these relationships in a variety of settings since empirical research on leadership communication on social media has shown both favorable and unfavorable effects on employee behaviors and online voice (van Zoonen et al., 2024). In Jordanian universities, where employees and students actively use social media to debate institutional policies, the leadership communication style is expected to influence the valence of employees’ online communication behaviors directly.

H4: Leadership communication style is positively related to online employees’ positive communication behaviors during crises.

H5: Leadership communication style is negatively related to employees’ negative online communication behaviors during crises.

4.4 The mediating role of employee engagement

Integrating SET and SCCT offers a basis for expecting mediation. SET explains that leadership communication strengthens employee engagement by creating trust and reciprocity. In contrast, SCCT explains that engaged employees become agents who either amplify or detract from organizational messages depending on perceived legitimacy and appropriateness of crisis response. In this sense, engagement translates leadership communication into digital behaviors. Existing studies support the mediating role of engagement between leadership and outcomes such as advocacy, performance, and voice (Mphaluwa et al., 2025). However, few have tested this mechanism in digital communication contexts, and almost none in higher education institutions during crises in the Middle East. By examining this mediation, the study addresses a theoretical gap and a pressing practical question for Jordanian universities.

H6: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between leadership communication style and employees’ communication behaviors on social media during crises.

Hence, Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the study, summarizing the hypothesized relationships among leadership communication style, employee engagement, and communication behaviors on social media during crises. The framework demonstrates the proposed connections between employee engagement, leadership communication style, and employees’ social media behavior during emergencies. It is anticipated that a leader’s communication style will increase staff engagement (H1), which will, in turn, promote positive communication behavior (H2) and decrease negative communication behavior (H3). Positive (H4) and negative (H5) communication behaviors are also strongly influenced by leadership communication style. The following links between positive (H6a) and negative (H6b) communication behaviors and leadership communication style are presented to be partially mediated by employee engagement on social media.

5 Methodology

5.1 Research design

The current study conducted a quantitative survey to examine the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between leadership communication style and employee communication behaviors on social media during crisis impact in Jordanian higher education. To achieve this, Smart Pls (SEM) is employed, which facilitates modeling complex relationships and is well-suited for non-normal data, allowing the findings of this study to be generalizable to any large organization in Jordan. The research framework’s relationships, including direct effects and mediation, were examined. The significance of all effects was verified through bootstrapping.

5.2 Population and sample

The target population consisted of academic and administrative personnel working at Jordan’s public and private institutions who use major social media platforms. A stratified sampling method was used to acquire a varied, representative sample from public and private Jordanian universities, based on their availability, reputation, and in relation to the crisis. Its criteria for choosing participants included being employees in either public or private Jordanian universities, in addition to being social media users. A total of 650 responses were generated, with 426 being valid after data cleansing, meeting beyond the required threshold for Structural Equation Modeling analysis. Thus, the response rate was 65.5% (Hair et al., 2022).

5.3 Data collection and instrumentation

The study conducted a pilot test to ensure the validity of the measurements. Following approval by the higher education review board, a pilot test was conducted with 30 employees who were recruited to participate in the pretest survey in Jordanian universities. On the other hand, all measurements in this study (i.e., leadership communication, employee engagement, and employee communication behaviors) on social media were adopted and adapted from previous studies. For example, to evaluate leadership communication style, including three dimensions such as “transformative,” “genuine,” and “supporting” communication style, these items were adopted from Men et al. (2022) and Santoso et al. (2022b). The other measures in this study were adopted from previous literature. Employee engagement was adapted from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9), a multidimensional construct including vigor, devotion, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2006; Arana-Medina et al., 2023). Finally, employee communication behaviors in the online environment have been measured with two dimensions (positive and negative communication behaviors), which were developed by van Zoonen et al. (2024) and Mirbabaie et al. (2023). Each variable was measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

6 Results

6.1 Procedure for statistical data analysis

To examine whether the measurement model fits, reliability, and validity tests were conducted by estimating the reliability of the constructs by means of composite reliability, in place of the traditional use of cronbach’s alpha (Hair et al., 2022). A structural model test on the relationship between hypotheses is employed in examining the model in a research. By utilizing the PLS-SEM algorithm and bootstrapping, the structural model is evaluated (Hair et al., 2019).

6.2 Demographic profile of the respondents

The demographic information for the sampled employees from public and private universities in Jordan is presented in Table 1. Of the 426 respondents, 232 (54.5%) were males, while the remaining 194 (45.5%) were females. Of the 426 participants in the study, 181 (42.5%) were between 31 and 40 years, and 116 (27.2%) were between 41 and 50 years. 21and 30 years, 103 (24.2%) were between 36 and 45, and 6.1% (18) were 50 or more. Regarding work experience, 36.6% reported 6–10 years of work experience, while 25.1% had more than 15 years of experience. Approximately 54.5% identified as male, 45.5% as female. Concerning their current Experience job, 36.6% (n = 156) had been in their role for 6–10 years, 16.4% (n = 70) for 11–15 years, and 25.1% (n = 107) for 15 years or more. 21.8% (n = 93) for 1–1-5 years. In terms of University Type, 50.2% (n = 214) in Public universities and 49.8% % (n = 212) from private universities.

6.3 Descriptive statistics of the constructs

The research constructs’ descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2. The findings show that respondents had a generally favorable opinion of leadership communication style (M = 3.87, SD = 0.72). Additionally, employee engagement received a reasonably high score (M = 3.92, SD = 0.69), indicating that employees are only somewhat engaged. In terms of social media communication behaviors, positive conduct (M = 3.75, SD = 0.71) was more common than negative activity (M = 2.41, SD = 0.65). These results offer preliminary evidence that during times of crisis, employees are more likely to participate in supportive digital communication than in critical or rumor-related activities.

6.4 Reliability of the instrument

The standardized factor loadings of the measuring items were used to evaluate their dependability. Items with loadings over 0.70 are regarded as very dependable according to the criteria proposed by Hair et al. (2022); nevertheless, values between 0.60 and 0.70 are also acceptable in exploratory investigations. All of the items in the present research showed adequate loadings, which ranged from 0.71 to 0.88, suggesting that the latent constructs were consistently represented by the observable variables. The comprehensive item loadings for social media communication behavior, employee engagement, and leadership communication style are shown in Table 3.

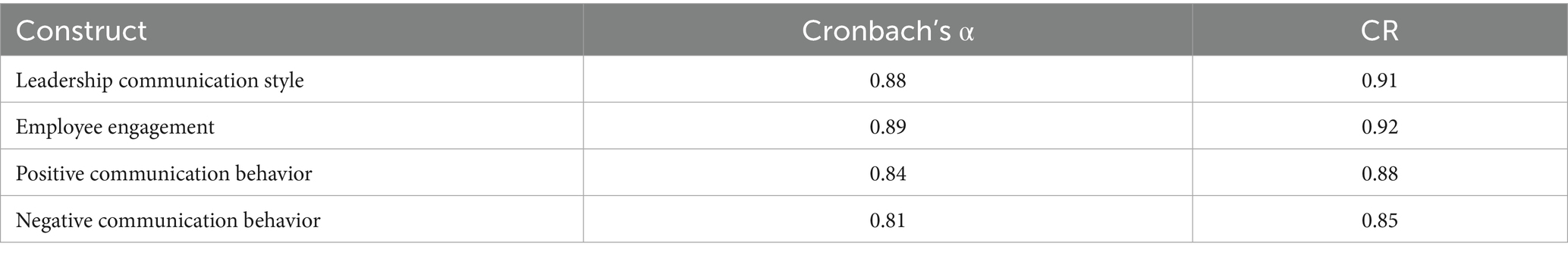

6.5 Internal consistency reliability

Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR) were used to evaluate the dependability of internal consistency. According to the recommendations made by Hair et al. (2022), strong internal consistency is indicated when α and CR values exceed 0.80, and adequate reliability is demonstrated when they exceed 0.70. With Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.81 to 0.89 and CR ranging from 0.85 to 0.92, the data shown in Table 4 show that every construct surpassed the recommended norms.

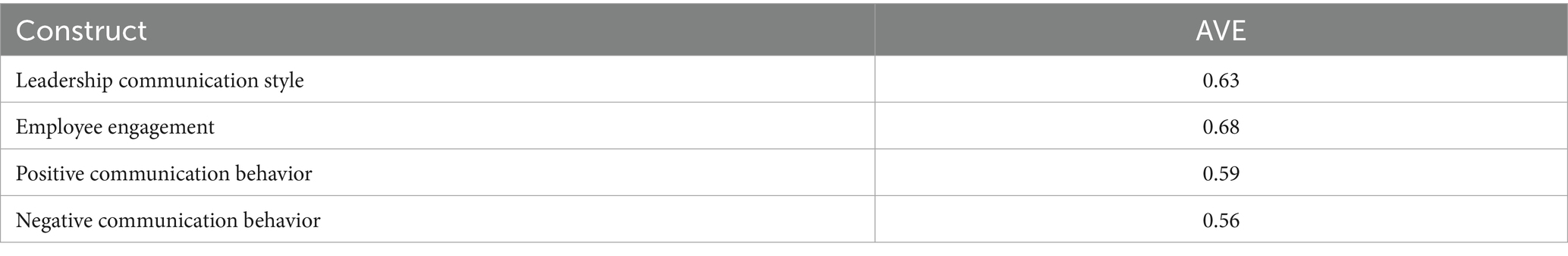

6.6 Convergent validity

In this study, AVE was utilized to determine the convergent validity of the latent constructs. The values of the AVE describe the average variance that a construct and its connected items share (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Typically, the values of the AVE must be greater than 0.5 to indicate that a construct accounts for more than half of the variance in its indicators (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Chin, 2010). In the current research, the AVE values ranged from 0.56 to 0.68, as shown in Table 5, indicating high levels of convergent validity for all the constructs studied.

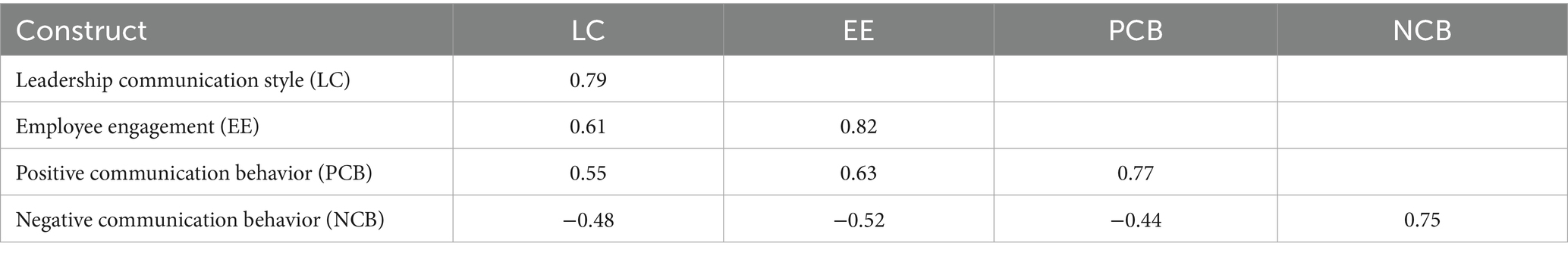

6.7 Discriminant validity – Fornell–Larcker criterion

To examine discriminant validity. This study employed the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the (HTMT) test (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 6 presents the Discriminant Validity (Fornell-Larcker) for the constructs. The table shows that the square roots of all the AVE values were larger than those of the other correlation values among the latent variables, indicating that the constructs utilized in this model were connected with discrete entities. Therefore, the measurement model exhibited good discriminant validity among its constructs.

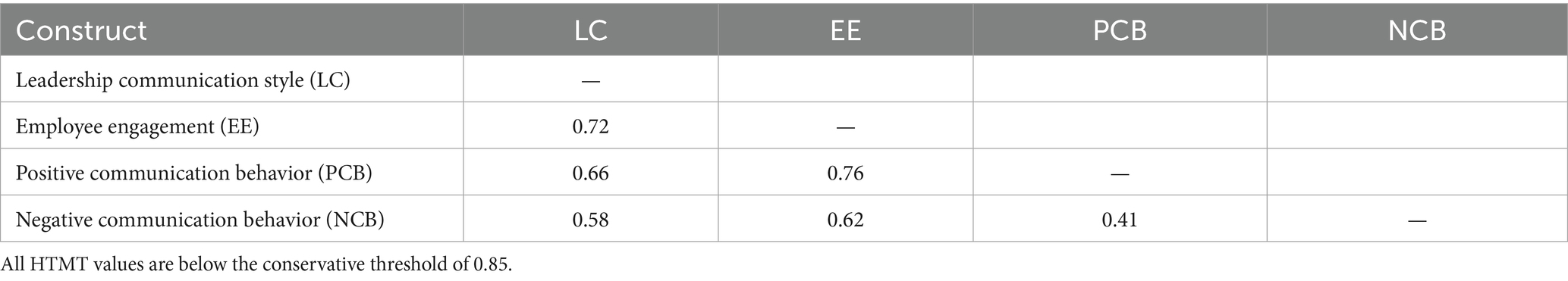

6.8 Discriminant validity – HTMT ratios

In this study, the HTMT standard demonstrates that discriminant validity has been achieved. The highest correlation was found between positive communication behavior and employee engagement, at 0.76 (see Table 7), which is lower than 0.90. Therefore, in the current study, both types of validity were reached.

7 Structural model assessment

After obtaining the validity and reliability for the outer model, there are some steps to be followed in examining the postulated relationships in the structural model. Structural model evaluation entails model evaluation based on the relationship between latent variables and other latent variables, in which hypotheses are tested. It is with the algorithm in PLS-SEM, with the utilization of bootstrapping, that the structural model is assessed (Chin, 2010). The Coefficient of determination (R2), the effect size (f2), the significance of path coefficients, and predictive relevance (Q2) were used to assess the structural model in PLS.

7.1 Collinearity assessment

Multicollinearity has been assessed in the present study using the Variance Inflation Factor method. As such, multicollinearity is considered an issue if a VIF value exceeds 5 (Hair et al., 2017). In this regard, the VIF values for the exogenous constructs of this present research. The VIF values ranged from 1.21 to 2.36, which is less than 5. Thus, it is evident that multicollinearity was not a concern among the constructs in the current study (Hair et al., 2019).

7.2 Explanatory power (R2)

Scholars have noted that R-squared values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 for endogenous latent constructs can be considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively (Hair et al., 2011). However, this study indicated that exogenous constructs contributed 0.52% of the variance in employee engagement through leadership communication. Furthermore, the R2 of positive online communication behaviors was substantial, with a value of 0.55% for employee engagement and leadership communication. Negative online communication was 0.36% by the same predictors. This means that employee engagement explained 52% of the variance in online communication behaviors. Thus, explanatory variables have adequately clarified the endogenous variables.

7.3 Effect size (f2)

As presented in this study, for Employee Engagement and Communication Behaviors as endogenous variables, the effect sizes indicated varying levels of influence across the exogenous constructs. Utilizing Cohen’s (2013) classification, the effect size of LC on EG (f2 = 0.38) should be considered large. In contrast, its effect on positive communication behavior (f2 = 0.11) is small, while the impact on negative communication behavior (f2 = 0.06) is also categorized as small. Additionally, the effect sizes of employee engagement on positive (f2 = 0.27) and negative (f2 = 0.19) communication behaviors fall within the medium range. Therefore, it can be concluded that the effects of the exogenous variables range from small to large across the endogenous variables.

7.4 Analyzing predictive relevance (Q2)

To compute Q2 as it comprises the main component of the path model, i.e., the structural model, to forecast omitted data points, this study employed the cross-validated redundancy technique. As such, an omission distance of seven was set to trigger the blindness procedure. Q2 values were 0.32 for employee engagement, 0.35 for positive communication behavior, and 0.21 for negative communication behavior. A value of Q2 of more than zero indicates the predictive significance of the model (Hair et al., 2011). This means that the model had adequate predictive relevance.

7.5 Model fit

The model fit was evaluated using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) in the current study. The SRMR value was 0.062, which is less than the suggested cutoff of 0.08, suggesting that the model fits the data.

7.6 Direct, indirect, and Total effects

To verify the mediating effect, the test on its significance was preceded by running the bootstrapping resampling method with 5,000 samples to obtain the t-value for testing whether the PLS direct paths were significant. These generated path coefficients are displayed in Table 8, below, which shows the output from the bootstrapping test:

On conducting the bootstrapping PLS-SEM 4 analysis, there was evidence to support that there was a significant positive relationship between leadership communication style and employee engagement (β = 0.41, t = 11.27, p < 0.001) based on Hypothesis 1.

A significant and positive relationship was observed between employee engagement and positive employee communication behaviors on social media (β = 0.39, t = 9.02, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed; on the other hand, it was found that there was a negative relationship between employee engagement and negative employee communication behaviors (β = −0.27, t = 6.48, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed.

Moreover, there was also a positive relationship between leadership communication styles and employees’ positive communication behavior on social media, which was found to be significant (β = 0.19, t = 3.12, p = 0.002); thereby, Hypothesis 4 was verified. Furthermore, a positive and significant association was found between leadership communication style and negative employee communication behaviors on social media (β = −0.14, t = 2.35, p = 0.019), which also supports hypothesis 5.

For the mediation, the hypothesized relationship is significant based on the path coefficient and the t-values. As expected, the employee engagement mediates the relationship between leadership style and both positive and negative employee communication behaviors on social media. The indirect effect on positive communication behavior (β = 0.16, t = 5.41, p < 0.001) and on negative communication behavior (β = −0.11, t = 4.02, p < 0.001). However, it found that employee engagement partially mediated the impact of leadership style and both positive and negative employee communication behaviors on social media, which is also supported by hypothesis 6.

8 Discussion

Some antecedents have been identified in previous studies, which influence employee communication behavior and their engagement in the workplace. For example, leadership style is an important antecedent, which exerts influence on communication behavior. Even though its importance is accepted, its role in developing countries like Jordan has not entirely been explored, given that most major institutions in higher education are being questioned about their reputation. The idea of communicative leadership or employee engagement became an important consideration, which could have had a major influence on employees’ behavior, preventing negative communication behavior on social media with regard to their organization during a crisis.

Findings have validated the significance of these antecedents, in particular, the leadership communication style adopted by management in employee participation, as well as in reacting positively to negative criticisms, which usually accompany occurrences in crisis situations in organizations. More specifically, it is to be noted that the findings from this research have identified the positive impact of leadership communication styles, which played an important role in shaping employees’ perceptions regarding their positive communication style in support and defence of their organization in crisis situations.

For example, Men et al. (2022) and Santoso et al. (2022b) have shown that leadership communication is a significant factor that influences positive behaviors, decreases negative behaviors, and increases trust and employee engagement in times of crisis in the digital environment. This also aligns with the findings of Mirbabaie et al. (2023) and Oksa et al. (2021), who found that faced with unfavorable criticism during a time of crisis, engaged workers are more likely to defend their companies. In a similar direction, Thelen and Men (2022) and Zhou et al. (2023) have demonstrated that workers who are not actively involved are more likely to disseminate misinformation and unfavorable comments, and if given the opportunity, they may even turn against their companies. The findings of this study confirm that the relational motives for negative behaviors in crises in a developing context, such as Jordanian higher education institutions, are similar to those of Western contexts.

The study also found that increased employee engagement and interaction positively impacted employee communication behaviors, leading to a greater sharing of positive information about organizations and a decrease in the dissemination of negative information during crises in the digital environment. As Al-Sharaira and others pointed out, the cultural context plays a crucial role in reducing the sharing of negative messages, given that it is culturally prevalent in Jordan for an employee to consider their workplace as their second family, thus making negative talk about it unacceptable.

The current study examined the mediating role of employee engagement as a factor explaining the relationship between communication leadership styles and employee communication behavior. The study found that employee participation acts as a mediator and explainer of the relationship between the study variables. It indicated that the concept of employee participation is fundamental and an important factor that Jordanian higher education institutions should pay more attention to, emphasizing employee participation and interaction, and maintaining good relationships during crises. This can be achieved by emphasizing leadership communication practices to foster positive communication behaviors and minimize the spread of negative ideas and information during crises. This aligns with the study by [name omitted], which indicated [details omitted]. Theoretically, the study tested an integrated model in a developing context like Jordan by combining two theories within a different context and from a crisis perspective. Public relations scholars have confirmed that situational theory should be re-examined and integrated into non-Western contexts to ensure its applicability. This study expanded a comprehensive theoretical framework by integrating situational theory with social exchange theory to provide insights and a comprehensive framework for future studies.

9 Conclusion

One of the problems being faced by organizations is finding ways to encourage their human capital to be fully engaged, given that engaged employees are more than willing to support their organization in its success. The current research confirmed that leadership style, especially leadership communication, is an element in ensuring high levels of employee engagement in the organization. Another finding from the research is that employee engagement acts as a mediator for leadership communication style and employee communication behavior on social media in a crisis situation. On the other hand, leadership communication can be used to increase employee engagement, given that employees are involved in decision-making.

This research is an important addition to the theory-based literature, specifically for studies on crises in developing countries. This research moves forward communication theory in crisis situations by incorporating it into one theoretical framework, specifically in the Jordanian higher education environment, which is facing a crisis situation at present. It investigates ways whereby reciprocity and mutuality have beneficial effects on employees’ behavior on social media in crisis situations, at the same time turning employees into advocates or supporters for their respective organizations by spreading good information and backing their respective companies in crisis situations. Additionally, this particular research enhances information on leadership style in communication, creating ways for employees to be influenced in their behavior in a positive manner.

Conversely, there are limitations to the current research, which was undertaken in a particular research environment involving Jordanian universities. Findings from the current research might not be generalizable to other parties. Future studies are encouraged to widen their scope to cover more representatives. The current research was based on one leadership style. Other styles of leadership, used by leaders, have not yet been covered in the research. Accordingly, the findings from the research are not general enough to deduce leadership styles for employee engagement and online communication behavior. Future studies need to be undertaken comprehensively, taking into consideration other popular styles in leadership. The current research only considered employee engagement for possible mediation in its model. Future studies should include other aspects for mediation, such as organizational structure, whether team or individual, organization culture, whether integration or adaptation, communication styles, among others.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee, Zarqa University, Jordan. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MaA: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MuA: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by Zarqa University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AlDreabi, H., Alshawabkeh, A., Almomani, O., and Al-Khasawneh, A. (2023). Sustainable digital communication using perceived enjoyment with a technology acceptance model within higher education in Jordan. Front. Educ. 8:1226718. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1226718

Alsharairi, A., Al-Souob, H. A. R., AlQadi, M. F., and Shatnawi, S. M. (2025). Social media communication and framing of the Gaza conflict: impact on public opinion. J. Intercult. Commun. 25, 73–82. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v25i3.1153

Alsharairi, A., and Jamal, J. (2021). Strategic communication of corporate social responsibility activities in strengthening customer-based organizational reputation: evidence from Jordanian banks. Am. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. Res. 5, 266–287.

Alsharairi, A., Jamal, J., and Yusof, N. (2022). Online communication behaviors in the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the influence of internal public relations practices and employee-organization relationships. South Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 3, 1–19. doi: 10.48165/sajssh.2022.3101

Alsharairi, A., Jamal, J., and Yusof, N. (2023). Online employees communication behaviours during crisis in Jordanian public hospitals: the value of internal communication practices. Int. J. Exp. Res. Rev. 34, 44–56.

Alyaqoub, R., Alsharairi, A., and Aslam, M. Z. (2024). Elaboration of underpinning methods and data analysis process of directed qualitative content analysis for communication studies. J. Intercult. Commun. 24, 108–116. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v24i2.573

Alyaqoub, R., and Alsharairi, A. (2020). Possibility to bridge the gaps: defining the issues that affect online global public relations practice. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 9, 44–50. doi: 10.35629/8028-0908034450

Arana-Medina, C. M., Arévalo-Avecillas, D., Arias-Gómez, D., and Salgado, A. (2023). Work engagement scale construct validity and reliability across occupational groups. Front. Psychol. 14:1195797. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1195797

Aslam, M. Z., Alsharairi, A., Barzani, S. H. H., Alyaqoub, R., and Yusof, N. (2024). The social neuroscience of persuasion approach to the religious intercultural communication: a conceptual evidence from Sidhwa’s novel ‘an American brat’. J. Intercult. Commun. 24, 1–11. doi: 10.36923/jicc.v24i2.629

Bagozzi, R. P., and Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, 74–94.

Barron Garrett, C. (2024). Leadership communication and employee trust in digital workplaces. J. Commun. Manag. 28, 34–49. doi: 10.1108/JCOM-09-2023-0123

Bindel Sibassaha, J. L., Pea-Assounga, J. B. B., and Bambi, P. D. R. (2025). Influence of digital transformation on employee innovative behavior: roles of challenging appraisal, organizational culture support, and transformational leadership style. Front. Psychol. 16:1532977. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1532977,

Chen, J. K., and Sriphon, T. (2022). Authentic leadership, trust, and social exchange relationships under the influence of leader behavior. Sustainability 14:5883. doi: 10.3390/su14105883

Chevalier, S., Perot, A., Klenkenberg, S., Dumoulin, F., Declaye, J., Stipulante, S., et al. (2025). Emotional intelligence, transformational leadership, and team satisfaction during the COVID-19 period in Belgium. Front. Organ. Psychol. 3:1578835. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2025.1578835

Chin, W. W. (2010). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In W. W. Esposito Vinzi, J. H. Chin, and H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (Springer handbooks of computational statistics series, vol. ii) (pp. 655–690). Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London, New York: Springer

Coombs, W. T. (2021). Revisiting situational crisis communication theory. Public Relat. Rev. 47:102009. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102009

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., and Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: a critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manage. Ann. 11, 479–516. doi: 10.5465/annals.2015.0099

Deepalakshmi, N., Tiwari, D., Baruah, R., Seth, A., and Bisht, R. (2024). Employee engagement and organizational performance: a human resource perspective. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 30, 5941–5948. doi: 10.53555/kuey.v30i4.2323

Eichenauer, C. J., Ryan, A. M., and Alanis, J. M. (2022). Leadership during crisis: an examination of supervisory leadership behavior and gender during COVID-19. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 29, 190–207. doi: 10.1177/15480518211010761,

Eva, T. P., Afroze, R., and Sarker, M. A. R. (2024). The impact of leadership, communication, and teamwork practices on employee trust in the workplace. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 12, 241–261. doi: 10.2478/mdke-2024-0015

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Giallouros, G., Nicolaides, C., Gabriel, E., Economou, M., Georgiou, A., Diakourakis, M., et al. (2024). Enhancing employee engagement through integrating leadership and employee job resources: evidence from a public healthcare setting. Int. Public Manag. J. 27, 533–558. doi: 10.1080/10967494.2023.2215754

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., and Ray, S. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., and Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 45, 616–632.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: indeed, a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19, 139–152. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Heuss, S. C., and Datta, S. (2023). Impact of leadership communication on job satisfaction and well-being of physicians. Discov. Glob. Soc. 1:11. doi: 10.1007/s44282-023-00004-w

Kim, Y. (2023). The role of base crisis response and dialogic competency. J. Public Relat. Res. 35, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2022.2148673

Koritarov, T., and Dimitrakieva, S. (2024). Situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) in maritime contexts: challenges, strategies and future directions. Norwegian J. Dev. Int. Sci. 147, 85–91.

Kwarteng, S., Frimpong, S. O., Asare, R., and Wiredu, T. J. N. (2024). Effect of employee recognition, employee engagement on their productivity: the role of transformational leadership style at Ghana health service. Curr. Psychol. 43, 5502–5513. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04708-9

Lee, Y. (2022). Personality traits and organizational leaders' communication practices in the United States: perspectives of leaders and followers. Corp. Commun. 27, 595–615. doi: 10.1108/CCIJ-10-2021-0118

Lee, Y., Lee, D., and Yang, S. (2024). How CEOs’ conversational communication on social media enhances internal relationships and employees’ social media engagement. Corp. Commun. Int. J. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.4775203

Lemoine, G. J., Hartnell, C. A., Hora, S., and Watts, D. I. (2024). Moral minds: how and when does servant leadership influence employees to benefit multiple stakeholders? Pers. Psychol. 77, 1055–1085. doi: 10.1111/peps.12605

Lengyel, A., Szőke, S., Kovács, S., Dávid, L. D., Bácsné Bába, É., and Müller, A. (2019). Assessing the essential pre-conditions of an authentic sustainability curriculum. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 20, 309–340. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-09-2018-0150

Liu-Lastres, B., Shin, Y. H., and Leng, H. K. (2023). Examining employees’ affective and behavioral responses during crises. Front. Psychol. 14:1130183. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1130183

Makowski, P. (2023). Remote leadership and work engagement: a critical review and future directions. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 8, 1–7. doi: 10.24018/ejbmr.2023.8.4.1835,

Mazzei, A. (2022). Internal crisis communication strategies: contingency factors determining an accommodative approach. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102212. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102212

Men, L. R., Qin, Y. S., and Yue, C. A. (2022). How supervisory leadership communication during COVID-19 fostered employee trust: evidence from motivating language theory. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 59, 193–218. doi: 10.1177/23294884211020491,

Mirbabaie, M., Kapasi, M. K., and Stieglitz, S. (2023). Negative word of mouth on social media: antecedents and consequences. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 33, 861–881. doi: 10.1108/JSTP-01-2022-0010

Mphaluwa, K., Dzansi, D. Y., and Mutambara, E. (2025). The mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between leadership and performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12:169. doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-05707-w

Nuortimo, K., Harkonen, J., and Breznik, K. (2024). Exploring corporate reputation and crisis communication. J. Mark. Anal., 1–22. doi: 10.1057/s41270-024-00353-8

Oksa, R., Kaakinen, M., Mantere, E., Savela, N., and Oksanen, A. (2021). Professional social media usage and work engagement: before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:636861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636861

Oloba, B. L., Olola, T. M., and Ijiga, A. C. (2024). Powering reputation: employee communication as the key to boosting resilience and growth in the US service industry. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 23, 2020–2040. doi: 10.30574/wjarr.2024.23.3.2689

Qin, Y. S. (2025). Inspiring employee engagement in remote work: the influence of leadership communication and trust in leadership. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 19, 458–475. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2024.2417669

Ravazzani, S., Mazzei, A., and Butera, A. (2024). “Internal crisis communication and the COVID-19 pandemic: heading towards a new future?” in Risk and crisis communication in Europe (New York, NY: Routledge), 311–325.

Santoso, A., Nugroho, Y., and Prabowo, H. (2022b). Transformational leadership communication during the COVID-19 crisis in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 36, 1152–1166. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-02-2022-0087

Santoso, N. R., Sulistyaningtyas, I. D., and Pratama, B. P. (2022a). Transformational leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: strengthening employee engagement through internal communication. J. Commun. Inq. doi: 10.1177/01968599221095182

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Tao, W., Lee, Y., Sun, R., Li, J. Y., and He, M. (2022). Enhancing employee engagement via leaders’ motivational language in times of crisis: perspectives from the COVID-19 outbreak. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102133. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102133,

Thelen, P. D., and Men, L. R. (2022). Increasing employee advocacy through supervisor motivating language: the mediating role of psychological conditions. Public Relat. Rev. 48:102253. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102253

van Zoonen, W., Verhoeven, J. W. M., and Vliegenthart, R. (2024). Leadership communication on social media: ambiguities in employee engagement and voice. J. Public Relat. Res. 36, 87–105. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2023.2294751

Walker, R. (2025). Leadership communication: reflecting, engaging, and innovating. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 62, 435–438. doi: 10.1177/23294884251345231

Wang, F., Li, Y., and Zhang, J. (2023). Social media use for work during non-work hours and employee outcomes: evidence from a multi-source study. J. Bus. Res. 158:113717. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113717

Wang, Z., Hangeldiyeva, M., Ali, A., and Guo, M. (2022). Effect of enterprise social media on employee creativity: social exchange theory perspective. Front. Psychol. 12:812490. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.812490,

Keywords: leadership communication, employee engagement, communication behavior, crisis communication, Jordanian universities

Citation: Alsharairi A, Alazzah M, Safori A and Aladwan MNS (2025) Leadership communication, employee engagement, and online communication behaviors during crises: evidence from Jordanian universities. Front. Commun. 10:1713290. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1713290

Edited by:

Leticia Rodríguez Fernández, University of Cádiz, SpainReviewed by:

Lóránt Dénes Dávid, John von Neumann University, HungaryFrancis Paniagua, University of Malaga, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Alsharairi, Alazzah, Safori and Aladwan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmad Alsharairi, YWFsc2hhcmFpcmlAenUuZWR1Lmpv

Ahmad Alsharairi

Ahmad Alsharairi Malik Alazzah1

Malik Alazzah1 Amjad Safori

Amjad Safori