A Correction on

Intradisciplinarity: can one theory do it all?

by Martin, J. R. (2024). Front. Commun. 8:1310001. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1310001

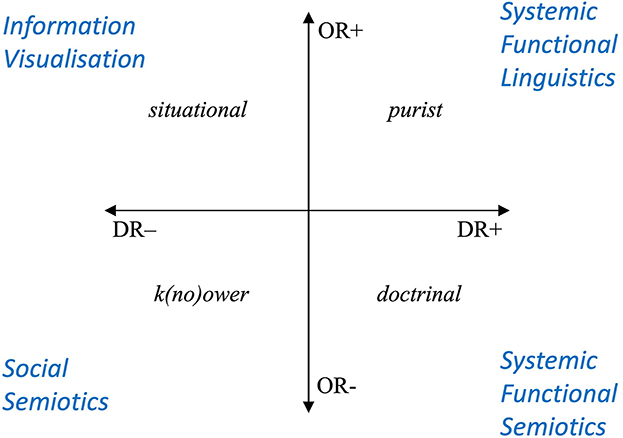

There was a mistake in Figure 10 as published. A wrong figure was published. The corrected Figure 10 appears below.

Figure 10. Multimodal discourse analysis and Maton's epistemic relations (insight); adapted from Maton (2014, Figure 9.3).

The original version of this article has been updated.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Keywords: Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), Systemic Functional Semiotics (SFS), legitimation code theory (LCT), multimodality, transdisciplinarity

Citation: Martin JR (2025) Correction: Intradisciplinarity: can one theory do it all? Front. Commun. 10:1725286. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2025.1725286

Received: 14 October 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited and reviewed by: Janina Wildfeuer, University of Groningen, Netherlands

Copyright © 2025 Martin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. R. Martin, amFtZXMubWFydGluQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

J. R. Martin

J. R. Martin