Abstract

The AI-based eGuide platform for healthcare centers in Oman represents a cornerstone of the Sultanate's critical national health infrastructure, underpinning both patient care and national resilience. This paper develops a comprehensive cybersecurity and governance framework to secure the eGuide system against an increasingly complex threat landscape characterized by phishing campaigns, ransomware incidents, and data leakage risks. Building upon global best practices, the study advances a transition from legacy perimeter security models toward a Zero Trust Architecture, ensuring continuous authentication, dynamic authorization, and micro segmentation of services. The framework is reinforced by the adoption of ISO/IEC 27000 aligned governance, demonstrable compliance with Oman's Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Further contribution is the integration of mathematically verified security primitives, including multi-factor authentication, hybrid RBAC cum ABAC access models, and blockchain-enabled audit trails, providing rigorous assurances of privacy, integrity, and accountability. The methodology also incorporates continuous evaluation cycles and penetration testing strategies, enabling proactive detection and mitigation of vulnerabilities. By embedding resilience through architectural scalability, high-availability patterns, and disaster recovery mechanisms, this research positions the eGuide platform as a secure, reliable, and future-ready foundation for Oman's digital health ecosystem.

1 Introduction

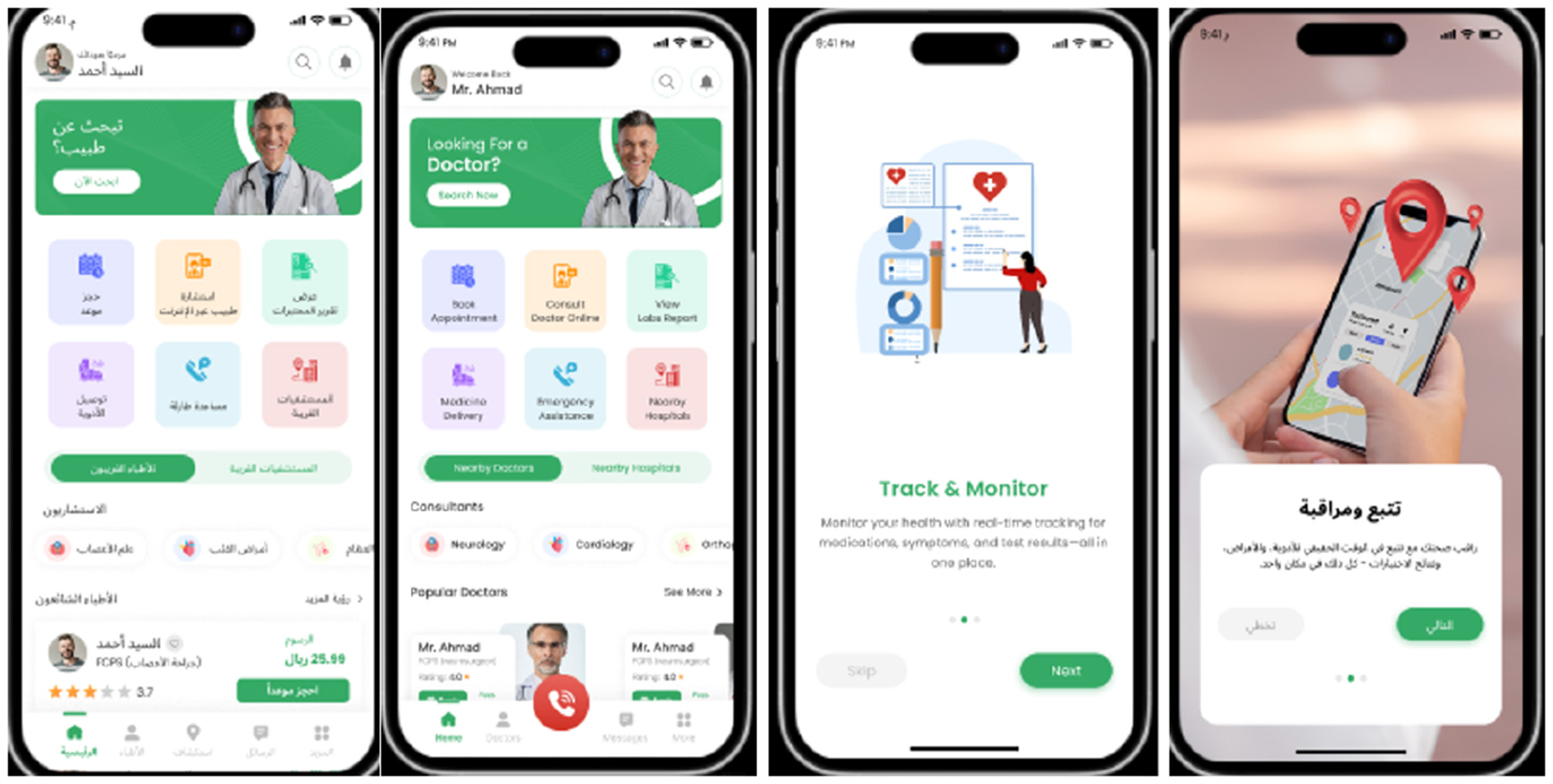

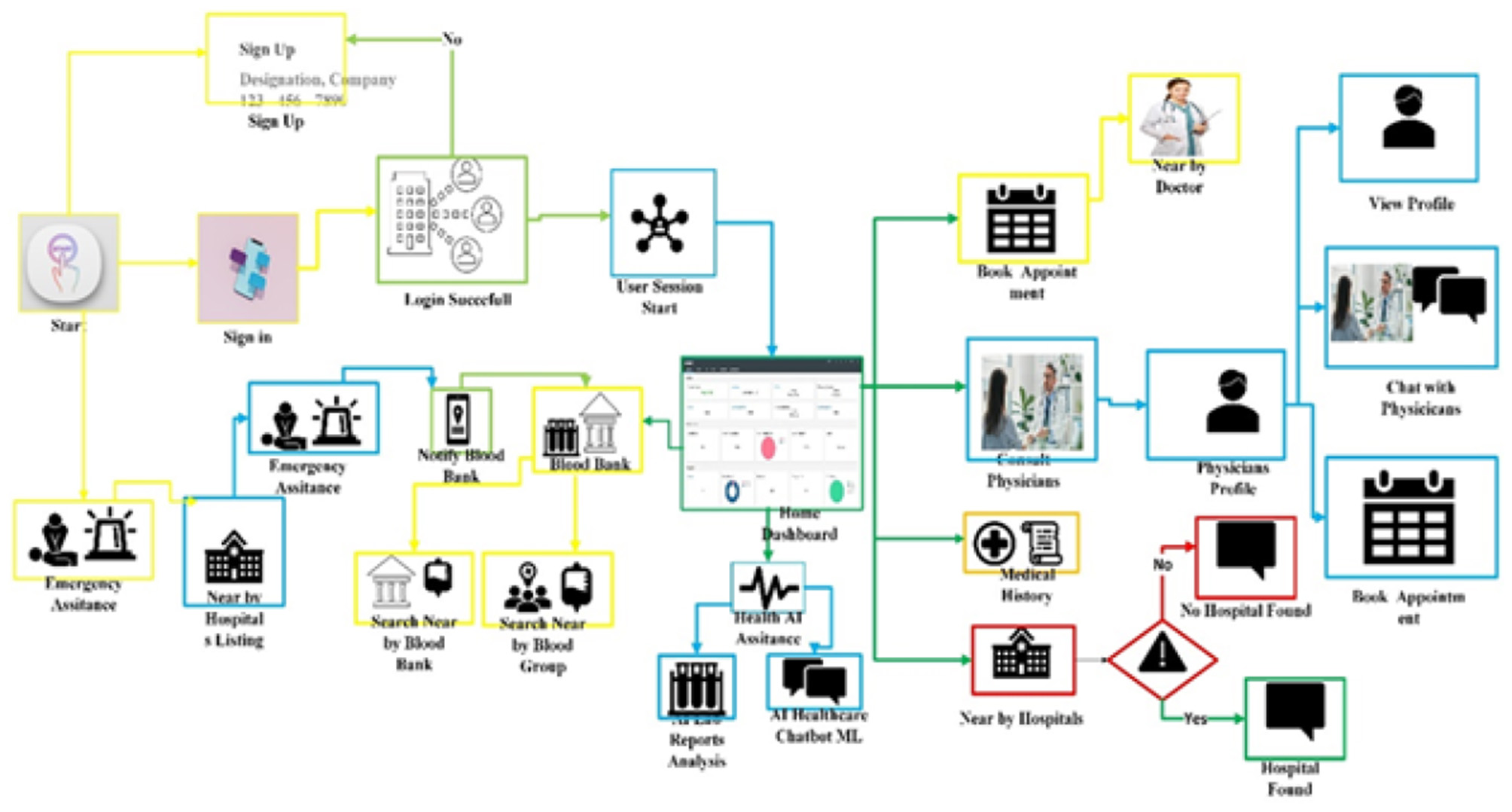

The AI based eguide for healthcare centers platform is an integrated healthcare information management system for healthcare centers of Oman that serves as the digital backbone of the Sultanate of Oman's health sector, passed feasibility and accessibility tests, combines the various facilities, it provides clinicians with a 360-degree view of patient history and clinical information (Podrecca et al., 2022), enabling more accurate, timely, and effective patient care (Fleming et al., 2025). By centralizing data from diverse sources, including the Ministry of Health, the Royal Oman Police, and other government bodies, AI based eguide for healthcare centers facilitates the rapid and precise transfer of health information, a function critical to its core mission. Figure 1 illustrates the various screenshots and services of the AI based eguide for healthcare centers of Oman. The eguide application is designed to use in emergency, normal life daily routine, doctor appointment, hospital searching, electronic patient record, blood bank search and reservation system and other health information was made available pertaining to the closed area of sultanate of Oman. The data flow diagram overview is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1

Screenshots of AI based centralized eguide for healthcare centers.

Figure 2

Overview of the data flow diagram of AI based eguide healthcare centers of Sultanate of Oman.

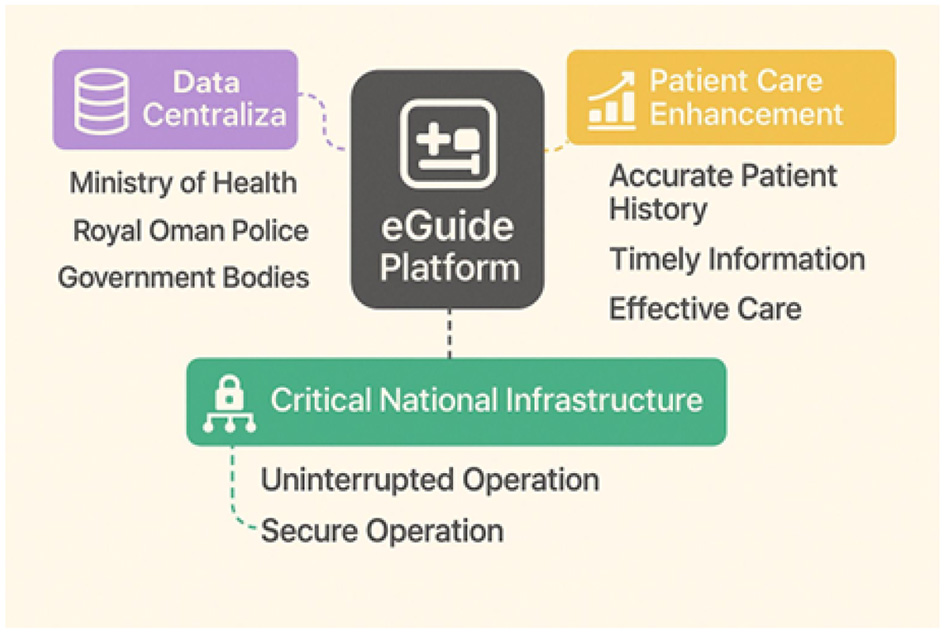

Given its central role, the AI based eguide for healthcare centers of Sultanate of Oman platform is designated as Critical National Infrastructure (CNI), its uninterrupted and secure operation is vital for the functioning of Omani society (Hussain et al., 2025) and its economy (Maashani et al., 2025), making its protection a national security imperative (Abisoye et al., 2001). Any disruption to its availability, or compromise of the confidentiality and integrity of its data, could have severe consequences, ranging from the erosion of public trust to direct impacts on patient safety and clinical outcomes. Figure 3 illustrates the central role and importance of the AI based central eguide Platform.

Figure 3

AI based central eguide platform: central role and importance.

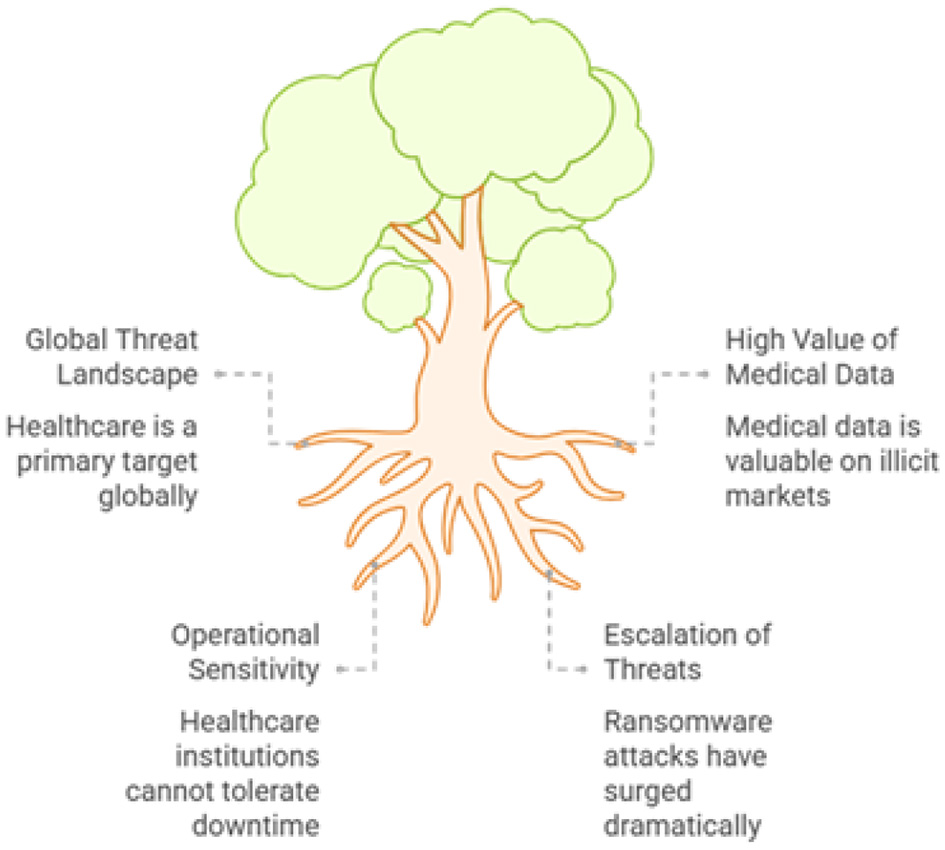

1.1 Contextualizing global and regional threats

This strategic research study is formulated as a direct response to a series of security incidents that, while successfully mitigated, highlight the persistent and evolving threats facing government and healthcare platforms globally (Qudus, 2025). The recent phishing attempts, ransomware attacks, and identified data leakage risks are not abstract possibilities but are manifestations of a global threat landscape where healthcare is a primary target (Shadadi et al., 2025). The Middle East, in particular, has become a focal point for such attacks. Cybercriminals are intensely motivated by the high value of medical data (Wang and Liu, 2025), which can be worth up to ten times more than financial records on illicit markets, and the extreme operational sensitivity of healthcare institutions, which cannot tolerate downtime (Venkata et al., 2025). Recent years have seen a dramatic escalation in the frequency and severity of threats (Duc et al., 2024; Idensohn et al., 2026; Ali et al., 2025; Kshetri, 2025). Ransomware attacks targeting the healthcare sector have surged by nearly 300% (Gupta et al., 2025), evolving from financially motivated crimes into life-threatening incidents that disrupt surgeries, delay critical treatments, and divert emergency services. These realities demand a cybersecurity strategy that is not merely reactive but proactively designed to anticipate and neutralize such threats. Figure 4 shows the various types of persistent cyberattacks.

Figure 4

AI based eguide platform persistent cyber attacks.

1.2 Study objectives and strategic approach

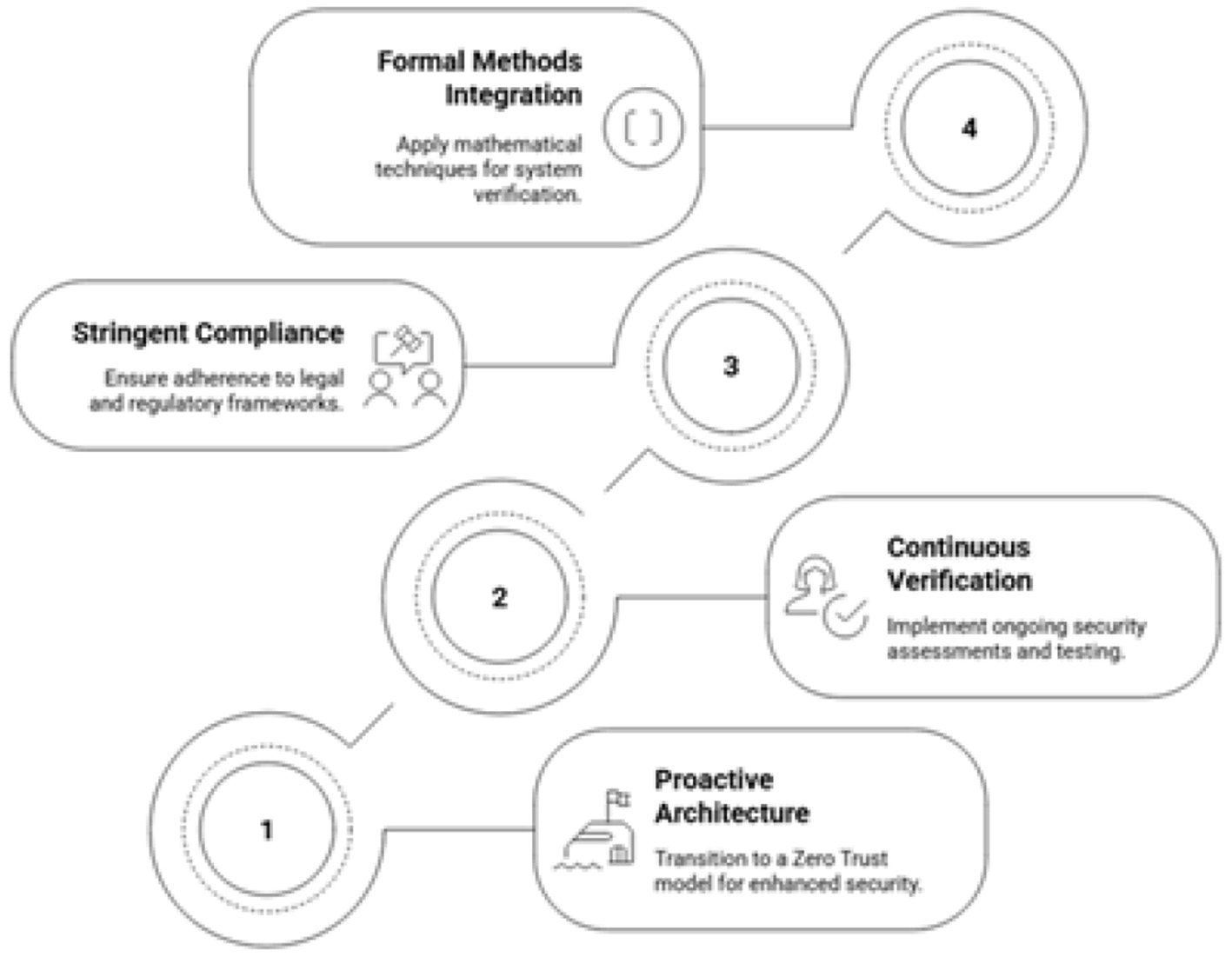

The primary objective of this study is to detail a holistic, multi-layered, and resilient cybersecurity strategy for the AI based eguide platform for healthcare centers of Sultanate of Oman. This strategy moves beyond traditional security paradigms to embrace a defense-in-depth approach guided by three core principles namely proactive or the secure-by-Design architecture, continuous verification and validation and the stringent and demonstrable compliance. The first principle which is proactive is the transitioning of the AI based plateform security whose base foundation is Zero Trust Model (Zakhmi et al., 2025) that ensures that no implicit trust is available and security must be verified at every access point. The other principle is the continuous verification and the validation where a robust framework is established for the ongoing security assessment, testing and auditing (Vaddiparthy, 2025). The emerging threats are effectively managed is assured through this method. The third core principle is the demonstrable and stringent compliance in which the assurance is made for the adeherance with the legal and regulatory guidelines including the Oman's personal data protection law (El-Khoury and Saleh, 2025), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (Rose et al., 2023; Fiedler, 2017) and the he General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Tamburri, 2020; Cornock, 2018).

A unique and critical component of this strategy is the integration of formal methods which means mathematically rigorous techniques for software and system verification (Masmoudi et al., 2022; Ibrhim et al., 2020). For a system as critical as AI based eguide of health centers of Oman, where software flaws can have life-or-death consequences, conventional testing is insufficient. Formal methods provide the capability to mathematically prove the correctness of key security components, offering the highest possible level of assurance that the system is secure by design (Blobel and Roger-France, 2025). This paper will outline how these principles can be translated into a concrete, actionable roadmap to safeguard Oman's vital national health infrastructure. The overall requirement of the robust cybersecurity of architecture is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Achieving robust cybersecurity.

2 International experiences and comparative evaluation of AI-based digital health eGuide systems

The digital transformation of healthcare systems is a global priority, with many countries deploying national-scale electronic health platforms to improve service accessibility, operational efficiency, and patient safety. Examining the evaluation outcomes and implementation experiences of comparable systems provides an essential international context for assessing the relevance, robustness, and scalability of the proposed AI-based eGuide framework for Oman.

2.1 European experiences

Several European countries are widely regarded as pioneers in national digital health infrastructures. The United Kingdoms NHS Digital ecosystem integrates electronic health records, patient portals, and decision-support systems under a centralized governance model. Evaluations of NHS Digital initiatives emphasize the importance of standardized interoperability frameworks, strong identity management, and compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). However, reported challenges include legacy system integration, fragmented access control policies, and increased exposure to ransomware attacks, which have driven recent shifts toward Zero Trust principles and continuous security monitoring.

Estonia represents a highly mature model through its nationwide Electronic Health Record (EHR) system, which leverages blockchain-inspired integrity mechanisms to ensure tamper resistance and auditability. Empirical evaluations demonstrate high levels of data integrity and citizen trust, largely attributed to transparent access logging and strong cryptographic controls. These findings strongly align with the eguide framework defined and aligned with the audit mechanism which is capable of providing suitability alongwith the national healthcare infrastructures.

2.2 North American experiences

The digital systems of the united states of America are highly regulated and also the systems of these digital platform ecosystems are highly decentralized and they are running under the governance of HIPAA. Most of the healthcare providers typically deploy the AI based patient portals, and robotic supported telehealth and the clinical decision support systems. These system are frequently and periodically for the integrity, availability and the confidentiality. Various studies presented and established the concept that the HIPPA compliance is considered as the data protection baseline and many of the security breaches can occur because of the insufficiency of audit trails, credential compromise due to phishing and the reconfigured access control. The security models present various limitations, hence the proposed model validates the adoption of multifactor authentication, and verified, hybrid RBAC-ABAC access control. Canada's provincial digital health systems further illustrate the importance of governance harmonization across jurisdictions. Evaluation reports indicate that inconsistent policy enforcement and heterogeneous security postures across regions complicate nationwide interoperability and resilience, emphasizing the need for unified governance frameworks such as ISO/IEC 27001-based Information Security Management Systems (ISMS).

2.3 Asia-Pacific experiences

The valuable insights are offered at the large scale and highly integrated digital health deployment in the Asia-Pacific region (Mohamed et al., 2025, 2026). The national health care record system of Singapore is considered one of the most robust and frequently cited along with centralized identity management, regulatory oversight strictness along with the cybernetics posture. The independent investigation suggest the high availability of the system, and the continuous risk assessment and mitigation where the regular penetration tests are conducted, and the regulatory strong enforcement are enforced. The proposed Omani framework is also advocated with the help of formal verification lifecycle and the continuous evaluation. In the same way, some other systems were introduced by Australia and South Korea and these systems are AI driven healthcare systems especially focused for emergency response and the population level analytics. There are growing concerns have been seen while evaluation, such as security of IoMT device, threats from inside, mis-configuration of cloud. In these situations, micro-segmentation, and Zero Trust architectures are reinforced. Figure 6 illustrates the various security architecture vulnerabilities.

Figure 6

Security architecture vulnerabilities.

2.4 Comparative insights and relevance to the Omani context

Various success factors have been evaluated and analyzed. These factors are continuous security assessment, control mechanisms and strong regulatory alignment. At the same time failures are also linked with multiple factors, such as, fragmented security governanc, insufficient auditability and the implict trust models. The international lessons are learned and the differentiating systematic AI based framework for Oman has been proposed. Unlike various other platforms where these system my face security control problems after deployment, the proposed system for Omani healthcare supprots the embeding of zero trust principle, compliance assurance and the formal verification at conceptual level as well as architecture level. And it is also aligned with the Oman's PDPL (El-Khoury and Saleh, 2025), GDPR (Tamburri, 2020; Cornock, 2018) and HIPPA (Rose et al., 2023; Fiedler, 2017) which positins it is as the globally but local compliant solution. In a conclusive way, the proposed framework is not only employing or replicating the international best practices, but also combines many advantages including block chain enabled system, continuous validation cycles within a single and comprehensive and cohesive national architecture. The scalability adn the transfer ability are also confirmed by the comparative analysis which provides as one of the suitable approach beyond the Omani health care ecosystem. The comparative evaluation of proposed AI Based Digital Health eguide systems are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Country | System | Security model | Key lessons for Oman |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | NHS Digital | GDPR-aligned, centralized EHR, partial Zero Trust | Legacy perimeter models increase ransomware risk; Zero Trust and MFA are essential |

| Estonia | National EHR | Blockchain-backed integrity, strong cryptographic identity | Blockchain auditability improves trust and data integrity |

| USA | HIPAA-based portals | Decentralized, RBAC-centric, HIPAA compliance | RBAC alone insufficient; hybrid RBAC-ABAC and MFA required |

| Canada | Provincial EHRs | Federated governance, ISO-aligned controls | Unified national ISMS needed for consistent security |

| Singapore | NEHR | Centralized governance, continuous security assessment | Continuous evaluation and penetration testing enhance resilience |

| Australia | My Health Record | Cloud-enabled, regulatory oversight | Cloud misconfiguration risks justify CSPM and IAM verification |

| South Korea | Smart Health Platforms | AI-driven analytics, centralized data sharing | IoMT security requires lifecycle control and micro-segmentation |

| Oman (Proposed) | AI-based eGuide | Zero Trust, ISO/IEC 27001, PDPL-GDPR-HIPAA | Secure-by-design, formally verified, nationally compliant framework |

Comparative evaluation of AI-based digital health eGuide systems.

3 Related work and literature review

3.1 Healthcare cybersecurity in digital health systems

The cyber threats exposure would be increased once the digitization of healthcare and its services are moving with rapid pace resulting making health care infrastructure one of the most frequent and targeted important and critical worldwide (Rahman, 2025; Paul et al., 2023). The legacy architectures which are perimeter based are visualized as the inadequate in terms of services, remote access and IoMT (Amiri et al., 2025).

3.2 Zero trust architecture and access control in healthcare

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) has emerged as a prominent response to the limitations of traditional network security models (Rose et al., 2023; Kindervag, 2010). ZTA enforces continuous authentication, dynamic authorization, and contextual access verification for every user and device, regardless of network location. In healthcare environments, prior studies suggest that Zero Trust adoption significantly reduces lateral movement and constrains attack blast radius (National Resilience Strategy, 2025). Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) has been proposed to address these limitations by enabling context-aware authorization decisions (Guo, 2025; Huang, 2025). Hybrid RBAC-ABAC models are increasingly recommended for healthcare use cases involving telemedicine, emergency access, and cross-organizational data sharing (Guo, 2025; Huang, 2025). However, most prior work evaluates these models conceptually or through simulation, with limited application of formal verification techniques to prove policy correctness.

3.3 AI integration in digital health platforms

A significant number of studies are available where the AI use in healthcare has been extensively studied. These studies provide an exhaustive information especially medical imaging, support for diagnostic, clinical decision making and the disease predication (Hu et al., 2021). Several and large trainign healthcare datasets have been trained and typically deep learning models have been employed. The statistical measurement metrics have been used including sensitivity, accuracy, and others (Lundervold and Lundervold, 2019). These systems for healthcare mostly focus on the optimization of the workflow, policiy driven automation and routing intelligently.

3.4 Compliance, auditability, and governance frameworks

Regulatory compliance has been widely addressed in healthcare cybersecurity research, particularly in relation to HIPAA, GDPR, and national data protection laws (Appari and Johnson, 2010; Tikkinen-Piri et al., 2018). ISO/IEC 27001-based Information Security Management Systems (ISMS) are frequently proposed as governance frameworks for managing healthcare cybersecurity risks in a systematic and auditable manner (ISO/IE, 2022; Von Solms and Von Solms, 2018). However, several studies demonstrate that regulatory compliance alone does not guarantee security (Herold and Schlegel, 2023). Multiple large-scale healthcare breaches have occurred in systems that were formally compliant but lacked effective auditability and tamper resistance (Ponemon Institute, 2021). Consequently, recent research has proposed blockchain-based audit mechanisms to ensure immutability, accountability, and non-repudiation (Azaria et al., 2016; Yue et al., 2016). Despite their promise, such mechanisms are rarely integrated into comprehensive national healthcare architectures.

3.5 Research gap and contribution of this study

The existing literature reveals a fragmentation between AI-enabled digital health systems, healthcare cybersecurity architectures, and formal governance and verification mechanisms. Most studies address these domains in isolation, focusing either on clinical AI performance, localized security controls, or regulatory compliance. This study builds on and extends prior research by proposing a holistic, secure-by-design framework for an AI-based centralized eGuide platform operating as Critical National Infrastructure (CNI) (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2018). Unlike prior work, the proposed framework integrates Zero Trust Architecture, formally verified hybrid RBAC-ABAC access control, immutable blockchain-based audit trails, and continuous penetration testing within a single cohesive system. By emphasizing architectural resilience, provable correctness, and multi-regulatory alignment, this work advances healthcare cybersecurity literature beyond reactive protection and data-centric AI toward a governance-centric, nationally scalable digital health security model.

4 Secure design assessment and architectural enhancements

4.1 Critical analysis of the existing AI based eguide architecture

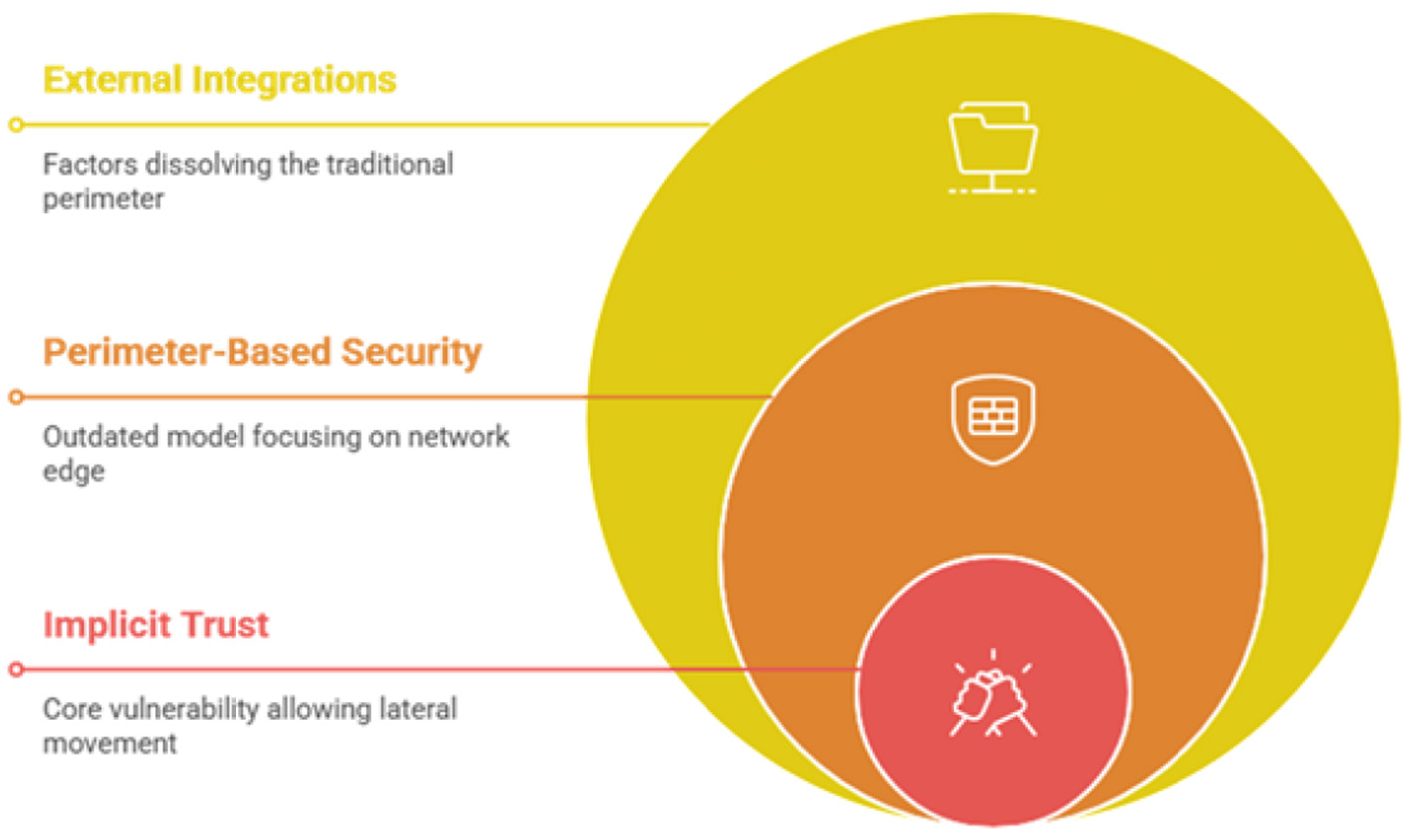

The existing security architecture of many large-scale government and healthcare information systems, including potentially the eguide platform, is often based on a traditional perimeter-based security model (Ahmadi, 2025). This model functions like a castle with a moat, focusing on strong defenses at the network edge while assuming that entities already inside the network are trustworthy. This architectural pattern, while once standard, contains inherent and critical weaknesses in the context of a modern, interconnected healthcare ecosystem (Govender et al., 2025). Its primary flaw is the concept of implicit trust. Once an attacker breaches the perimeter, whether through a phishing attack that compromises user credentials, an exploited vulnerability in a public-facing server, or a malicious insider, they can often move laterally within the network with relative ease (Kaur et al., 2025). This lateral movement is a key tactic used in devastating ransomware attacks. Furthermore, the very notion of a clear perimeter is dissolving. The eguide platform integrates with numerous external government and private entities, supports remote access for clinicians and administrative staff, and connects with a growing number of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices (Portal and Al-Shifa, 2025).

4.2 Architectural principles for national-scale resilience and scalability

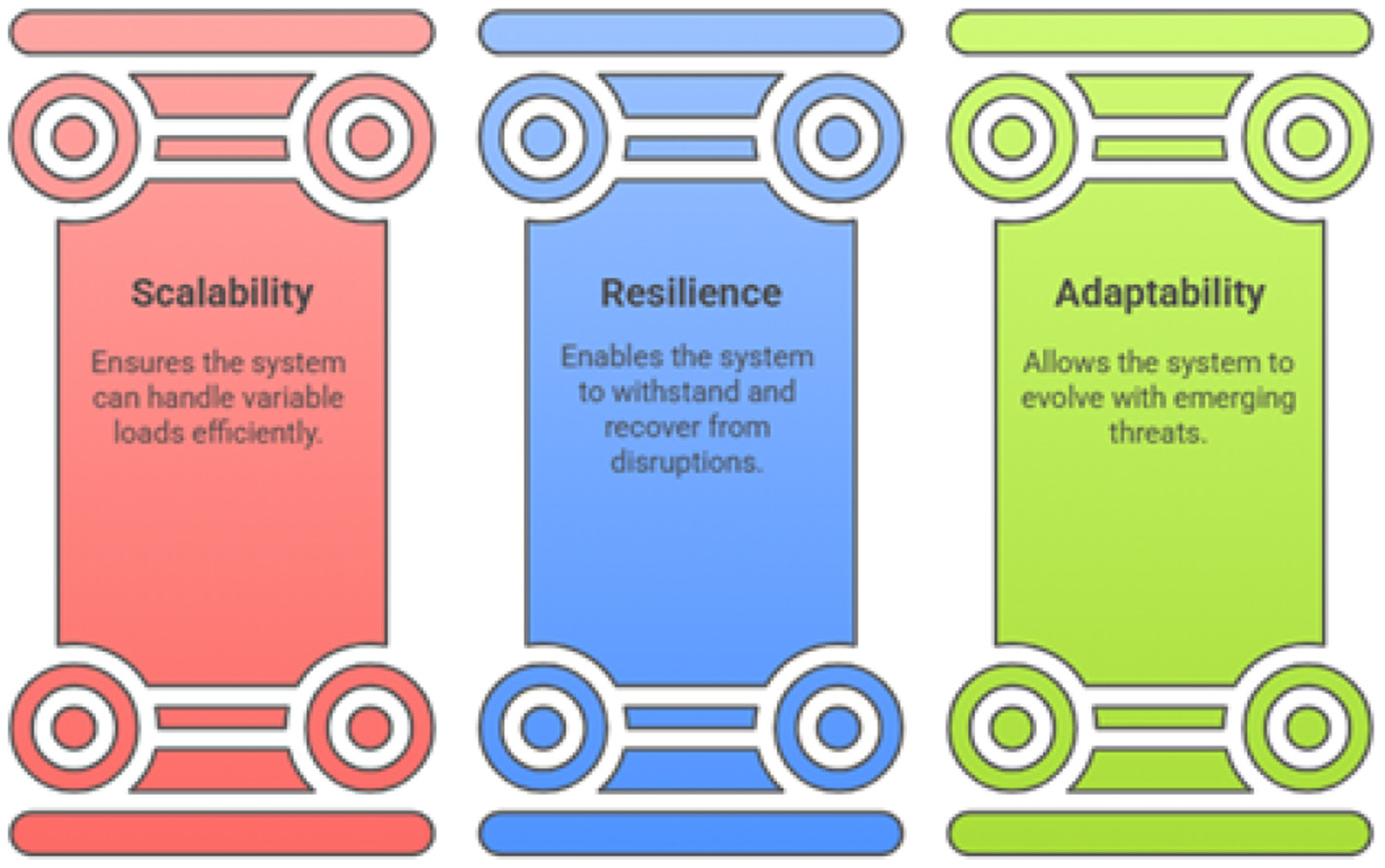

To support the entire population of Oman and defend against sophisticated, widespread attacks, the eguide platform's architecture must be founded on modern principles of scalability, resilience, and adaptability. Figure 7 illustrates the three foundations of architecture namely scalability, Resilience and adaptability. Variable loads are expected for the national healthcare systems during the operational times which may prove disaster for public health (Mousavi et al., 2025). The system must be scalable and microservices architecture or service oriented architecture would solve the problem rather than using legacy systems. For the resilience, the system must be capable of handling the attacks and continue its performance and this resilience can be achieved through redundancy from the geographically separate locations (Elghani Meliani et al., 2025; Pham et al., 2025). Degrading non essential services during the fail time will provide more characteristics of the resilience (Ahmadi, 2025). As the matter of adaptability, nothing is static especially the landscape and various new attack vectors and the new vulnerabilities are continuously evolving especially the country like Oman (Bhumireddypalli et al., 2025; Heath et al., 2022).

Figure 7

Eguide architectural foundation.

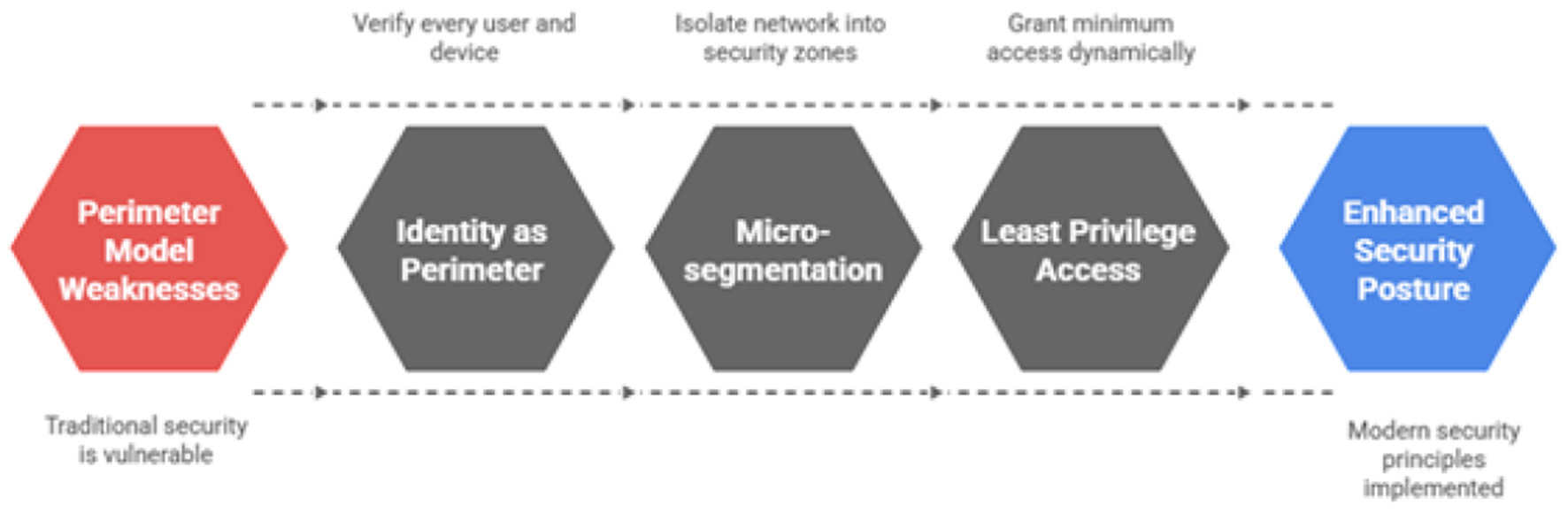

4.3 Proposed architectural evolution a zero trust framework for health care

To address the identified weaknesses of the perimeter model and build a foundation based on modern security principles, this research study strongly recommends the strategic evolution of the eguide platform to a Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA). ZTA is a paradigm shift in cybersecurity that operates on the fundamental principle of “never trust, always verify” (Abisoye et al., 2001). It eliminates the dangerous concept of a trusted internal network and instead enforces security for every access request, regardless of its origin. Implementation of Zero Trust architecture cycle is illustrated in Figure 8. The core tenets of ZTA, as applied to the AI based eguide platform, include:

Figure 8

Zero trust architecture implementation cycle for the AI-based eGuide platform, illustrating continuous authentication, authorization, micro-segmentation, and policy enforcement across healthcare services.

This architectural shift directly supports and strengthens compliance with regulations like HIPAA (Rose et al., 2023; Fiedler, 2017) and GDPR (Tamburri, 2020; Cornock, 2018). By enforcing granular, attribute-based access controls and generating comprehensive, immutable logs for every access attempt, ZTA provides the verifiable evidence required to demonstrate that access to sensitive patient data is strictly controlled and audited (Ullah et al., 2024).

4.4 High-availability and disaster recovery patterns for uninterrupted care

For a critical healthcare system, ensuring continuous operation is as important as ensuring confidentiality. This requires a robust strategy for both high availability and disaster recovery. It is essential to distinguish between these concepts and the overarching goal of business continuity. DR focuses on restoring IT infrastructure after a major disruptive event, while BC is the broader strategy for maintaining critical healthcare operations during such an event. The continuity of healthcare systems is shown in Figure 9. The proposed architecture for AI based eguide must incorporate geographic redundancy where An HA architecture should be implemented using at least two geographically separate data centers. The other is the Automated failure along with comprehensive BC or DR plan.

Figure 9

Healthcare system continuity.

Traditional disaster recovery scenarios often assume a widespread system failure, such as an entire data center being compromised by ransomware. The micro-segmentation inherent in ZTA fundamentally changes this calculus. By containing the “blast radius” of an attack, ZTA can prevent a localized breach from escalating into a system-wide catastrophe. This means that an incident may only require the isolation and recovery of a small segment of the network rather than the entire platform. This capability dramatically improves RTOs and makes the goal of maintaining business continuity during a cyberattack far more achievable. The strategic case for ZTA is therefore twofold: it provides superior protection against initial breaches and simultaneously enhances the platform's ability to withstand and recover from attacks that do succeed, a critical consideration for any national healthcare system.

5 A framework for continuous assessment, evaluation, and compliance

The foundation is the secure architecture which can be managed effectively through measurement and the validation. For this purpose there is a need of a robust framework, for the assessment security, evaluation which requires that the system must be rigorous and to align with the system for national healthcare (Thi et al., 2025).

5.1 Establishing an ISO/IEC 27000-based Information Security Management System (ISMS)

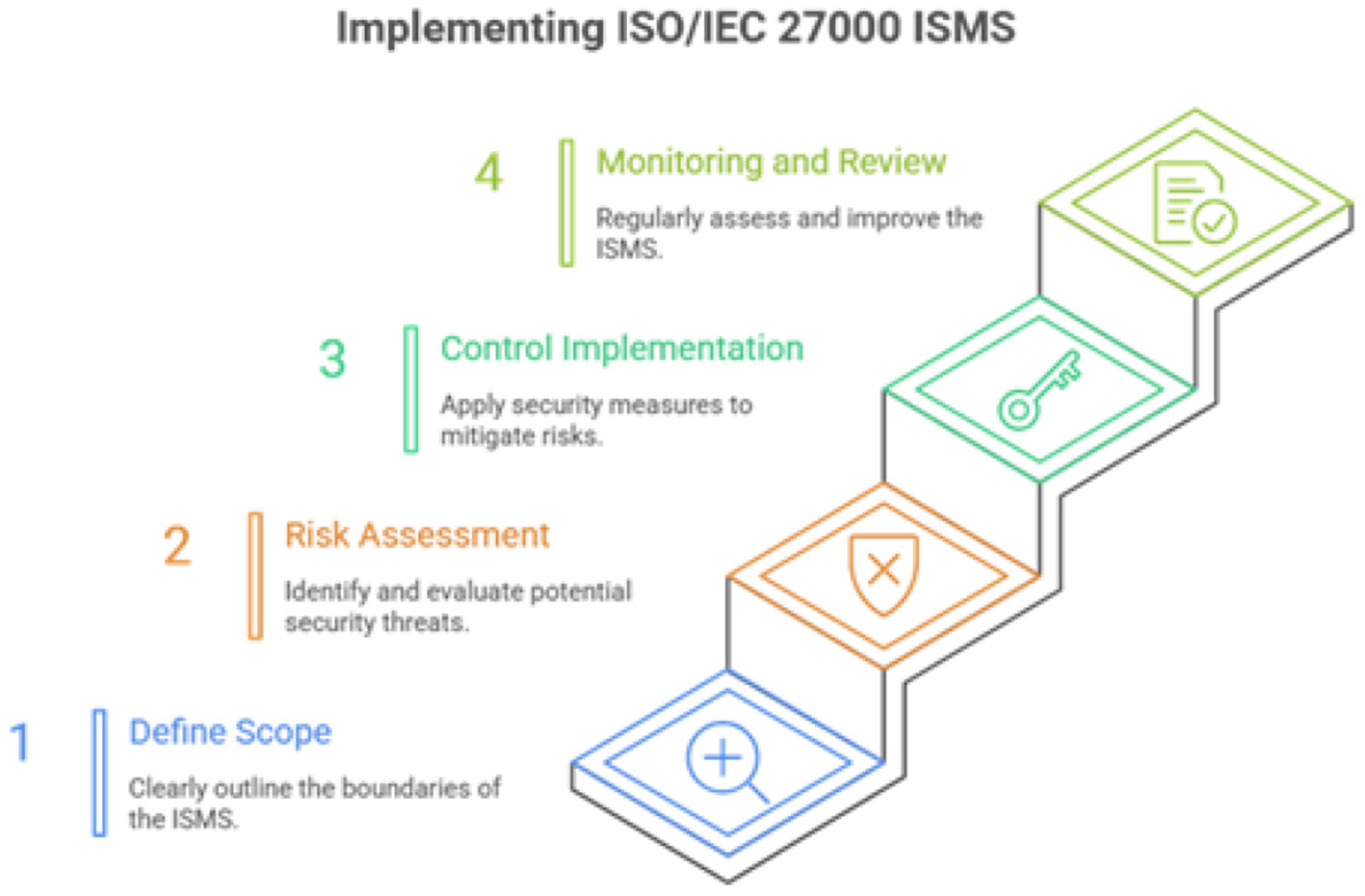

For the international standard to be recognized in perspective of the security, AI based eguide for helathcare centers of Oman must be accomplished with the same standards which must be based on the ISMS which is also called information security managment system especially the compliance with the ISO/IEC 27001 standard (Pavão et al., 2024). The security policies of the organization is managed by the holistic framework and also CIA Triad is also supported (Diamantopoulou et al., 2020). The implementation roadmap of the IEC 2700is givn in Figure 10.

Figure 10

ISO ISMS implementaion.

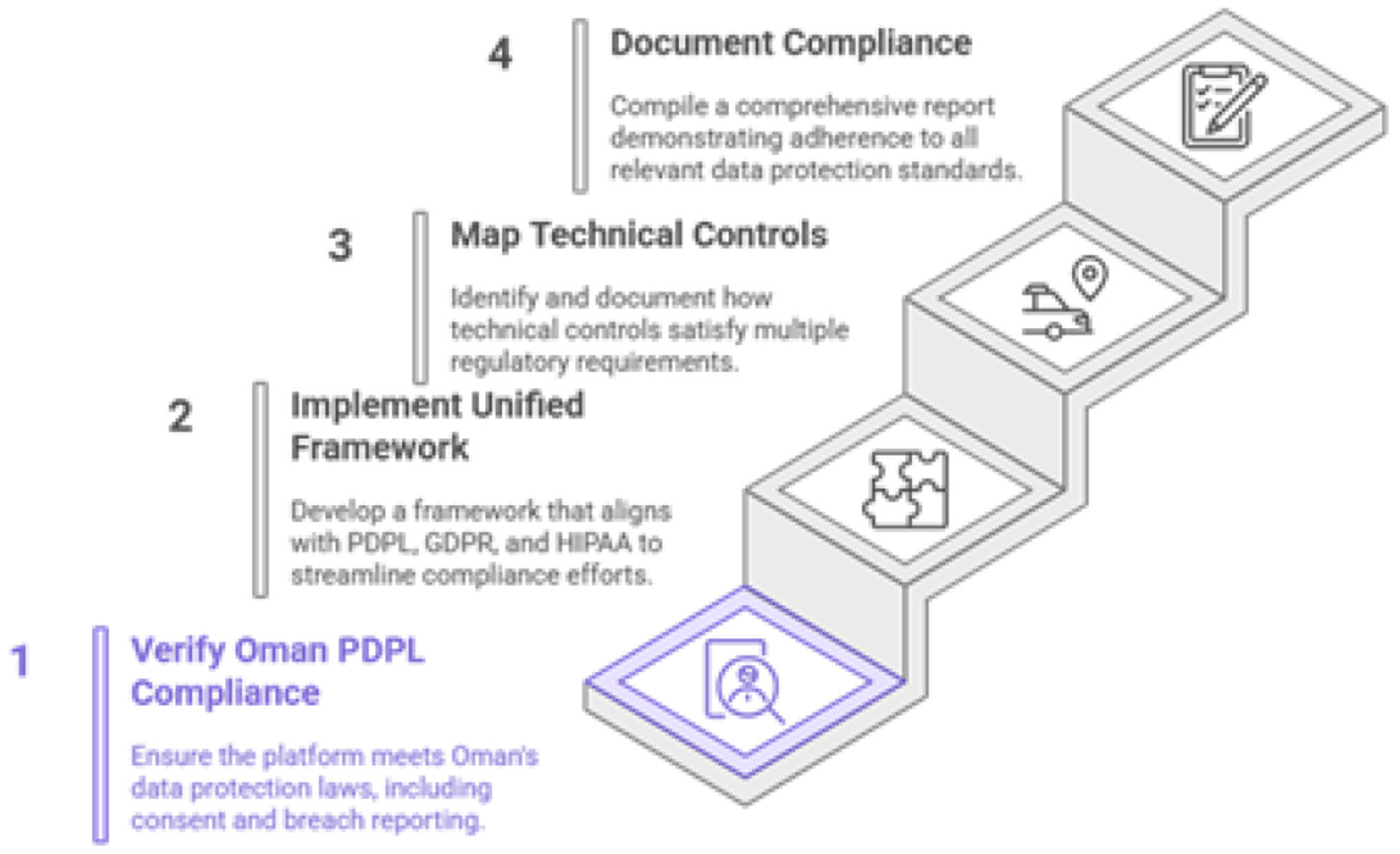

5.2 Methodology for auditing compliance with PDPL, GDPR, and HIPAA

The proposed AI eguide is also assure the Oman's PDPL (Alshammari, 2025; El-Khoury and Saleh, 2025) and the international laws namely GDPR (Tamburri, 2020; Cornock, 2018) and HIPAA (Rose et al., 2023; Fiedler, 2017). The compliance achievement is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11

Achieving comprehensive data compliance.

Unified compliance framework: To avoid redundant effort, the audit methodology will use a unified control framework. Many requirements of the PDPL (Alshammari, 2025), GDPR (Tamburri, 2020; Cornock, 2018), and HIPAA overlap. For instance, the PDPL's definition of personal data and its special protections for health data align closely with GDPR's principles and HIPAA's definition of Protected Health Information (PHI) (Rose et al., 2023). A single technical control, such as a well-defined access control policy, can be mapped to satisfy the requirements of all three regulations simultaneously. The audit will document this mapping to demonstrate comprehensive compliance efficiently.

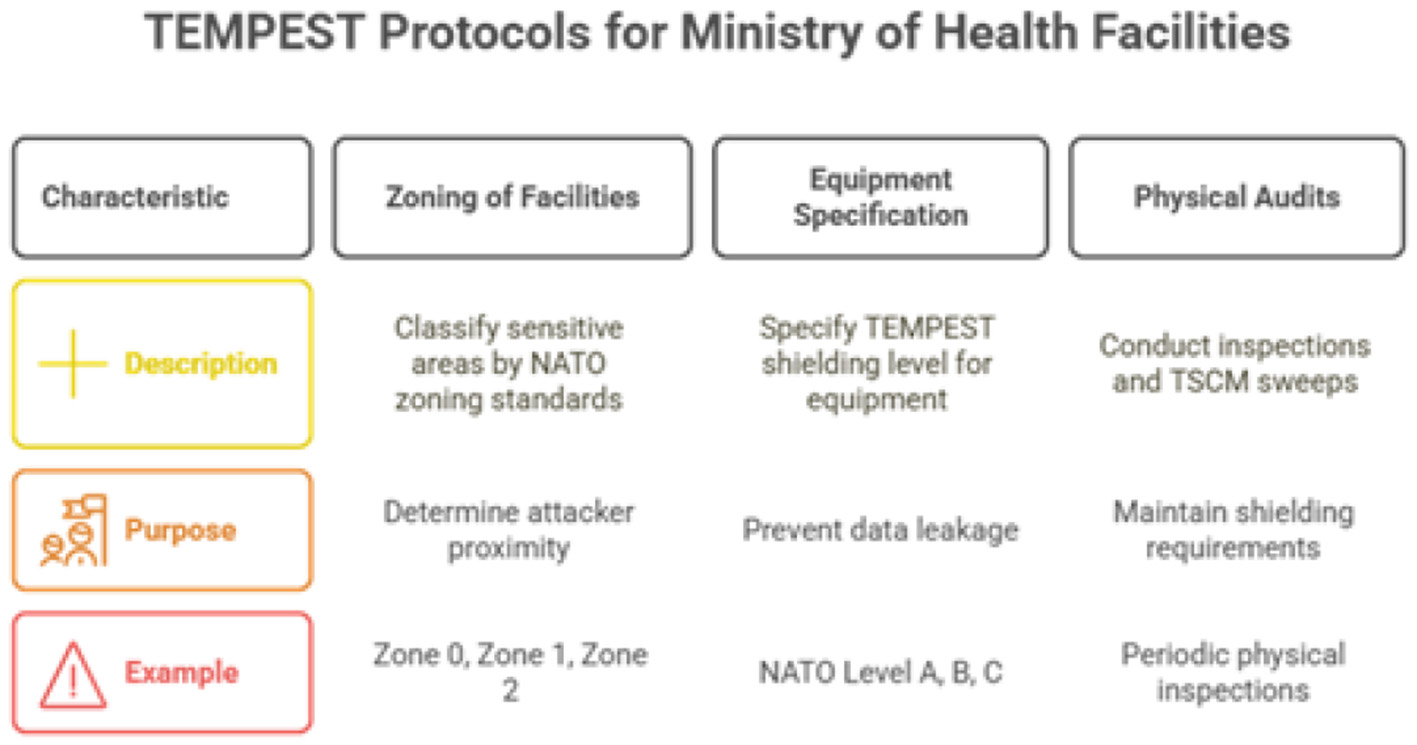

5.3 Emission security (TEMPEST) protocols for ministry of health facilities

For CNI, security must extend beyond the digital realm to the physical environment. Sophisticated adversaries, such as state-level actors, may attempt to intercept sensitive information through electromagnetic eavesdropping. TEMPEST (Telecommunications Electronics Materials Protected from Emanating Spurious Transmissions) is a set of standards designed to prevent data leakage from such compromising emanations (Martin et al., 2023). Figure 12 shows the tempest protocols for the facilities of Ministry of Health.

Figure 12

Tempest protocols.

Given the sensitivity of the data processed by AI based eguide, the assessment plan must include a review of emission security. The methodology will involve:

-

Zoning of Facilities: Classifying sensitive areas within MOH facilities (e.g., primary data centers, key command and control rooms) according to NATO zoning standards (e.g., Zone 0, Zone 1, Zone 2), which correspond to the assumed proximity of an attacker.

-

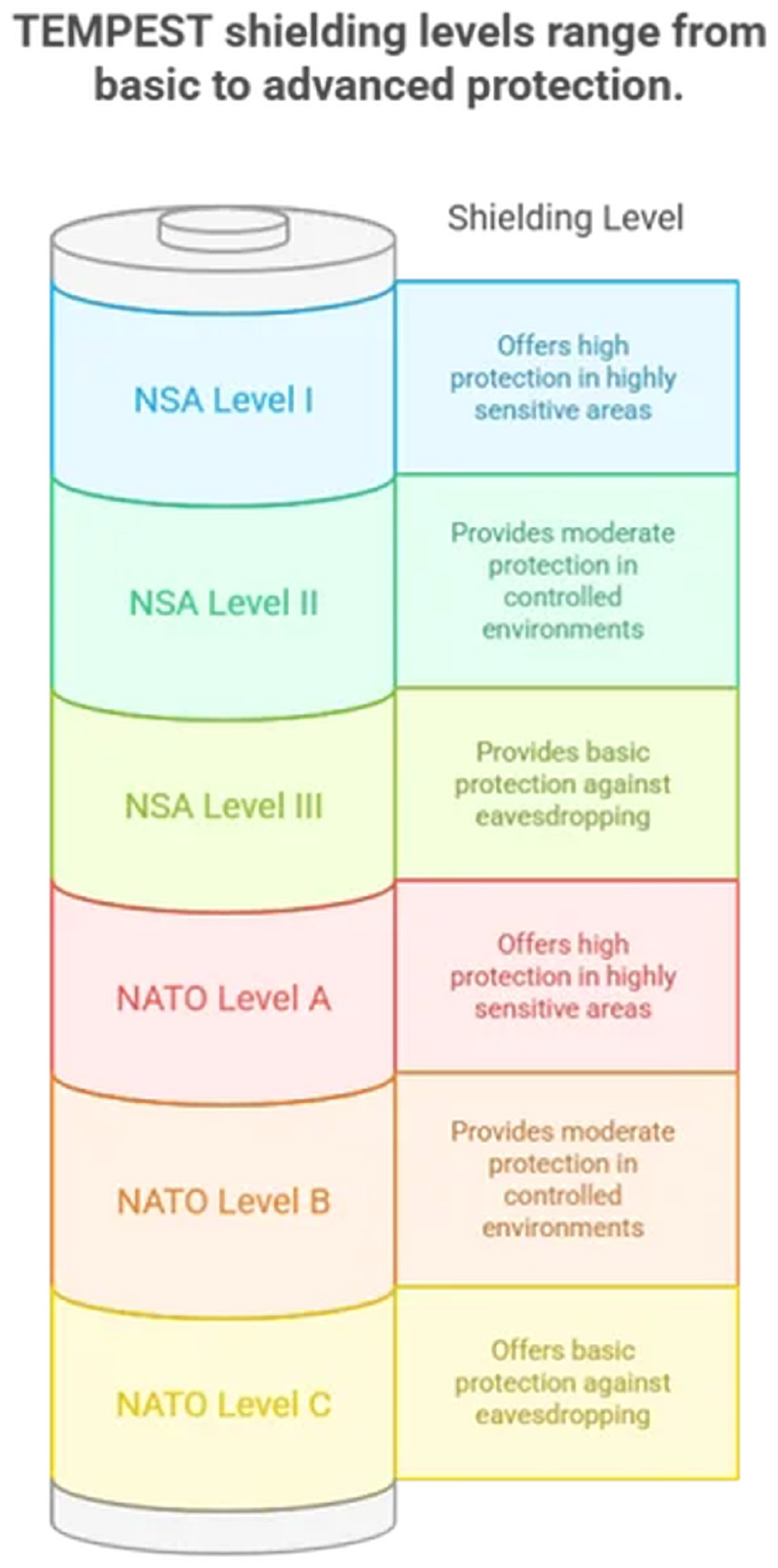

Equipment Specification: Specifying the required TEMPEST shielding level (e.g., NATO Level A, B, C or NSA Level I, II, III) for all computer and network equipment that processes classified or highly sensitive eguide data within these designated zones. Figure 13 shows the TEMPEST shielding levels ranging from basic to advanced protection.

-

Physical Audits: Conducting periodic physical inspections and technical surveillance countermeasures (TSCM) sweeps to ensure that shielding and physical separation requirements are maintained.

Figure 13

Tempest levels.

5.4 Integrating formal methods into the verification and validation lifecycle

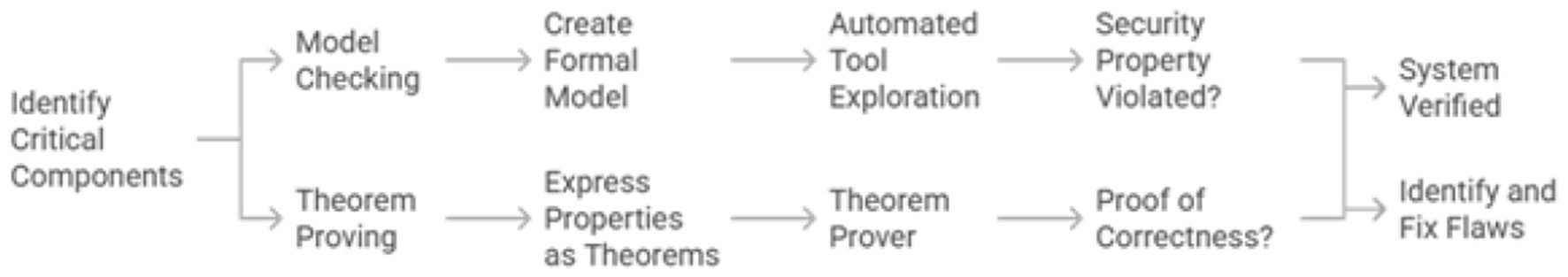

Standard testing and auditing can verify that a system behaves correctly under expected conditions, but they cannot prove the absence of flaws. For safety-critical systems, a higher level of assurance is required. Formal methods are mathematically rigorous techniques that can be used to specify and verify system properties with mathematical certainty, eliminating entire classes of design flaws before implementation (Saad Awadh Alanazi and Ahmad, 2025). System verification process cycle is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14

Formal methods in system verification.

The assessment and evaluation plan will integrate formal methods in a targeted manner for eguide's most critical components:

-

Model checking: This technique will be used for components that can be modeled as finite-state systems, such as communication and authentication protocols. A formal model of the protocol is created, and an automated tool exhaustively explores all possible states to check if a security property (e.g., “an unauthorized user can never gain access”) is ever violated (Alzahrani and Alzahrani, 2025). This can uncover subtle flaws that are nearly impossible to find with traditional testing.

-

Theorem proving: The more complex properties are verified through this technique and the popular applications are the authentication and communication protocol. Mathematics is typically used to express the desired security properties and for the proving of logical correctness, a theorem prover is used.

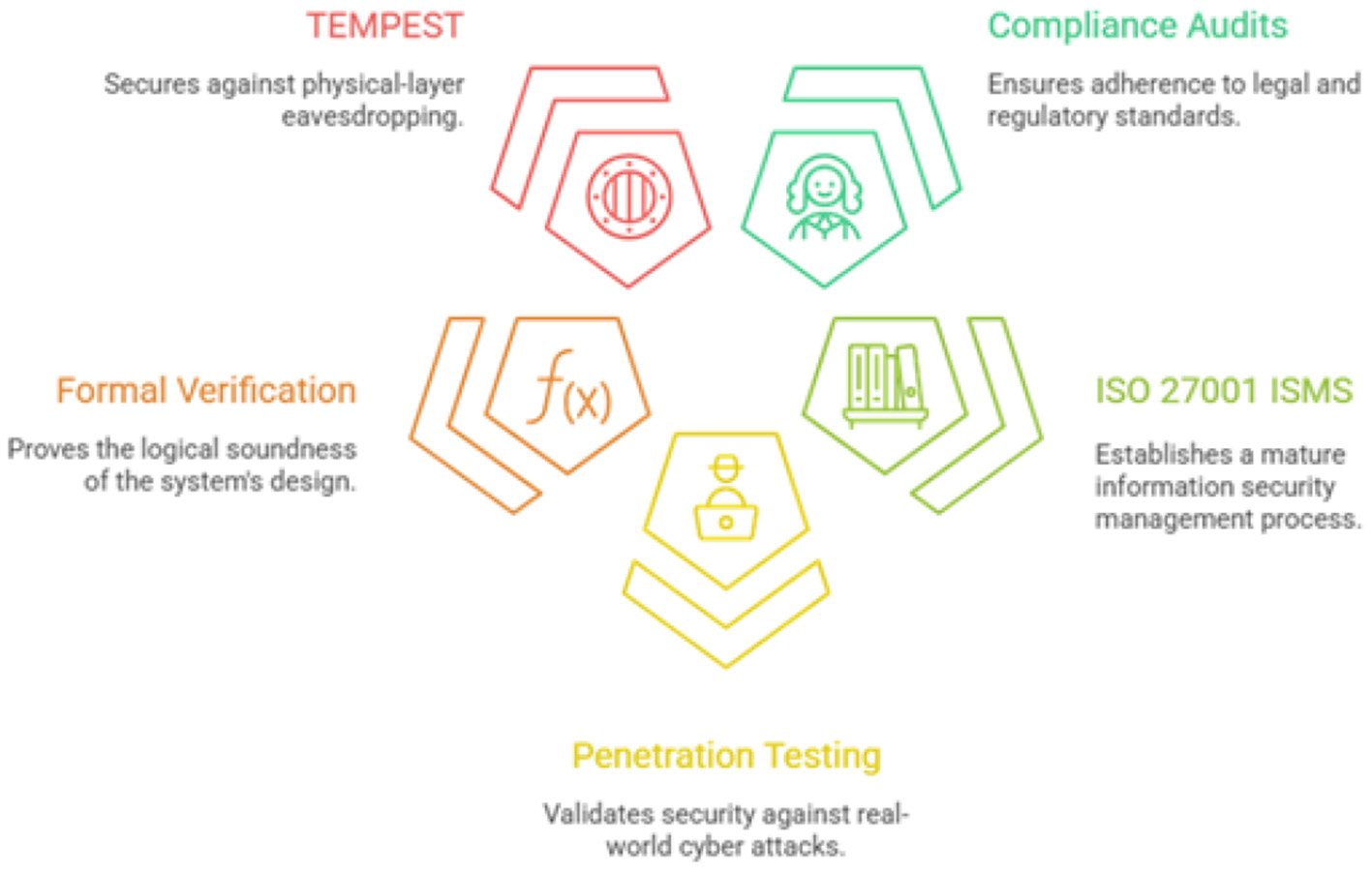

An assurance framework containing multiple layers is created by integrating the formal methods that provides defense-in-depth not just in implementation, but in the verification process itself. Compliance audits provide a baseline of legal adherence. The ISO 27001 (Podrecca et al., 2022) ISMS ensures a mature management process. Penetration testing validates the implementation against real-world attacks. Formal verification proves the logical soundness of the design. Finally, TEMPEST secures the system against physical-layer eavesdropping. This sophisticated, risk-informed strategy allows the Ministry to allocate resources appropriately, applying the most rigorous verification techniques to the most critical components, thereby building a system that is demonstrably and provably secure. The security framework for AI based eguide is illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15

AI based eguide's security framework.

6 Design and formal verification of advanced security primitives

To build a truly resilient system, the AI based eguide platform must be fortified with advanced, purpose-built security primitives. These foundational components governing authentication (Alzahrani and Alzahrani, 2025), authorization, privacy, and integrity must not only be implemented according to best practices but also be formally verified to ensure their correctness and robustness against sophisticated attacks (Saad Awadh Alanazi and Ahmad, 2025).

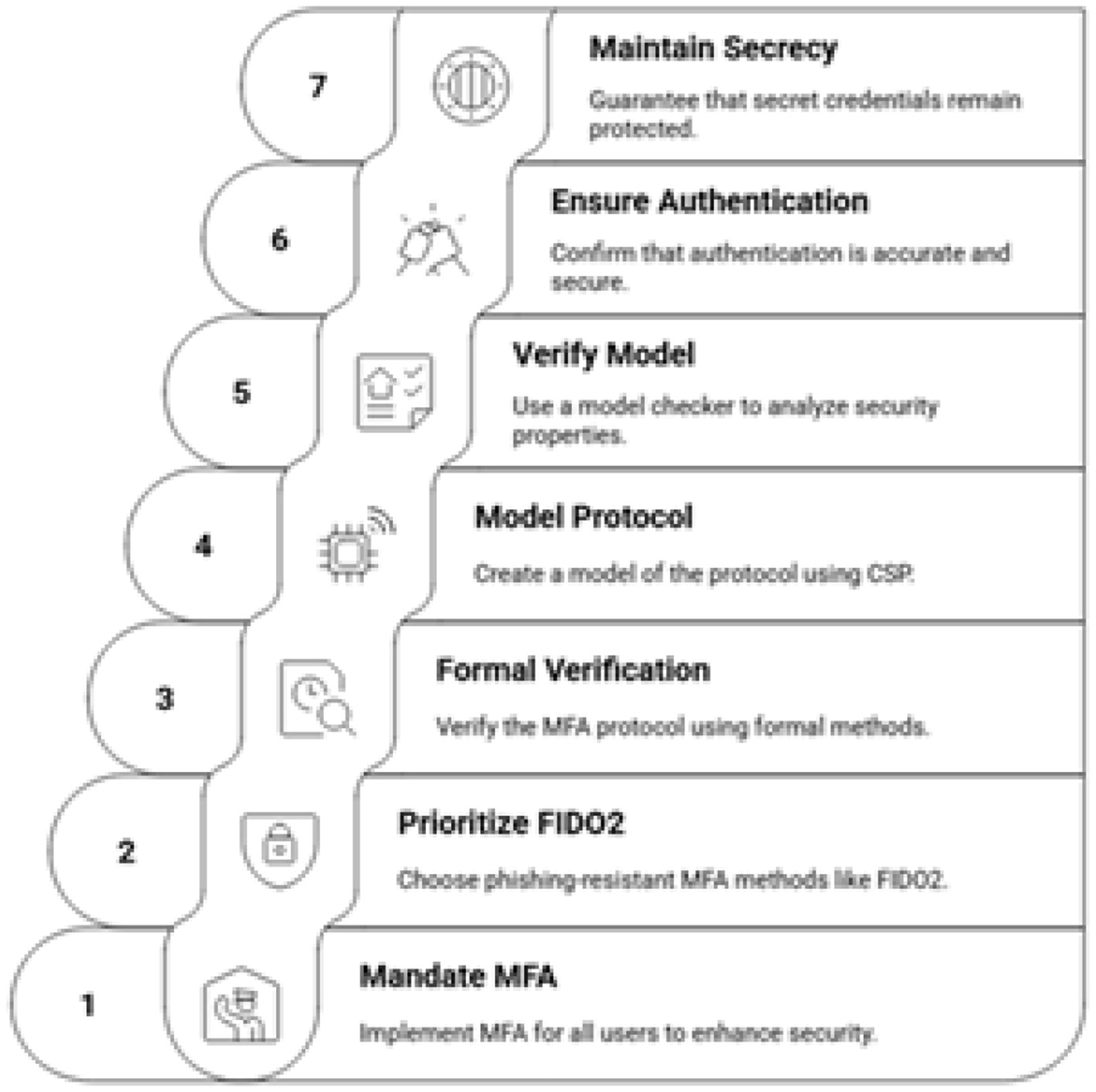

6.1 Strengthening identity: phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication (MFA)

The recent phishing incident targeting MOH employees underscores the fundamental weakness of password-only, single-factor authentication. It is imperative to mandate the use of Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) for all access to the AI based eguide platform, for both clinical and administrative users. MFA requires users to present at least two distinct types of credentials from the following categories: something you know (a password), something you have (a physical token or mobile device), and something you are (a biometric like a fingerprint). However, not all MFA methods are equal. Methods like SMS-based one-time passwords (OTPs) are vulnerable to interception and phishing attacks. Therefore, the strategy must prioritize phishing-resistant MFA methods, such as those based on the FIDO2/WebAuthn standards, which use public-key cryptography to bind the authentication to a specific device and origin, making it immune to traditional phishing attacks (Phat et al., 2025). The implementation of the MFA is shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16

Implementing secure MFA.

Formal verification of the MFA protocol: To provide the highest level of assurance, the chosen MFA protocol must be formally verified.

-

Modeling: Communication sequential process is used to model protocol using formal language that also capable of description of the various interactions for the server, user and authenticator.

-

Verification: CasperFDR is one of the popular model checker and may also be employed to take away other powerful adversaries especially which are based on Dolev-Yao intruder model (Mao, 2005) that provides the overall and complete control over the network. The model checker will exhaustively search for any sequence of actions that could violate key security properties, such as Authentication which means verifying that if a user successfully completes the protocol and believes they are authenticated to the AI based eguide server, then the server also correctly believes it has authenticated that specific user, and not an imposter. The other is Secrecy which means proving that the adversary can never learn the session key or other secret credentials exchanged during the protocol execution.

This process provides mathematical proof that the protocol is resistant to common attacks like man-in-the-middle (Pincu et al., 2025), replay (Contreras et al., 2025), and impersonation attacks (Javanmardi et al., 2024).

6.2 Dynamic authorization: a formally verified hybrid RBAC and ABAC model

Traditional Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) is insufficient for the dynamic and complex environment of a modern healthcare system (De Carvalho Junior and Bandiera-Paiva, 2018). While simple to manage initially, RBAC often leads to role explosion, where an unmanageable number of roles must be created to handle specific permissions. This strategy proposes a hybrid access control model that combines the simplicity of RBAC with the power and flexibility of Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) (Huang, 2025). The hybrid access control approach is illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17

Hybrid access control model.

-

RBAC foundation: RBAC will be used to define baseline, static permissions based on a user's job function (e.g., “Doctor,” “Nurse,” “Pharmacist,” “Researcher”) (De Carvalho Junior and Bandiera-Paiva, 2018).

-

ABAC for dynamic control: ABAC policies will be layered on top to provide fine-grained, context-aware authorization for sensitive operations. ABAC makes access decisions in real-time based on a combination of attributes from the user (e.g., role, location, on-call status), the resource being accessed (e.g., data sensitivity level, patient record type), and the environment (e.g., time of day, device security posture, network location) (Huang, 2025).

An example of ABAC policy might be: “Permit access if the user's role is ‘Cardiologist' AND the resource's sensitivity is ‘Patient-General' AND the access location is from within the ‘Hospital-Trusted-Network'.” Formal verification of the access control policy: A misconfigured access control policy can create critical security holes. Formal verification can prove that the policy set is logically sound and free from dangerous inconsistencies of modeling, verification, separation of duties and data segregation. A justification of the adoption and a clear comparison is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Aspect | Prior work | This study |

|---|---|---|

| Security model | Perimeter-based or partial defense-in-depth (Kaur et al., 2025) | Full Zero Trust Architecture (Rose et al., 2023) |

| Access control | RBAC or conceptual ABAC (Hu et al., 2014) | Formally verified hybrid RBAC-ABAC |

| AI usage | Clinical prediction or isolated decision support (Topol, 2019) | Governance- and security-oriented AI orchestration |

| Evaluation metrics | ML accuracy or qualitative risk discussion | CVSS v3.1, OWASP Top 10, exploitability analysis |

| Audit mechanisms | Mutable logs or SIEM (Herold and Schlegel, 2023) | Blockchain-based tamper-proof audit trails |

| Compliance scope | Single-regulation focus (Appari and Johnson, 2010) | Unified PDPL-GDPR-HIPAA alignment |

| Validation | Simulation or conceptual analysis | Formal verification + penetration testing |

| System scope | Institutional or departmental | National-scale Critical National Infrastructure |

Comparative evaluation of AI-Based digital health eGuide systems.

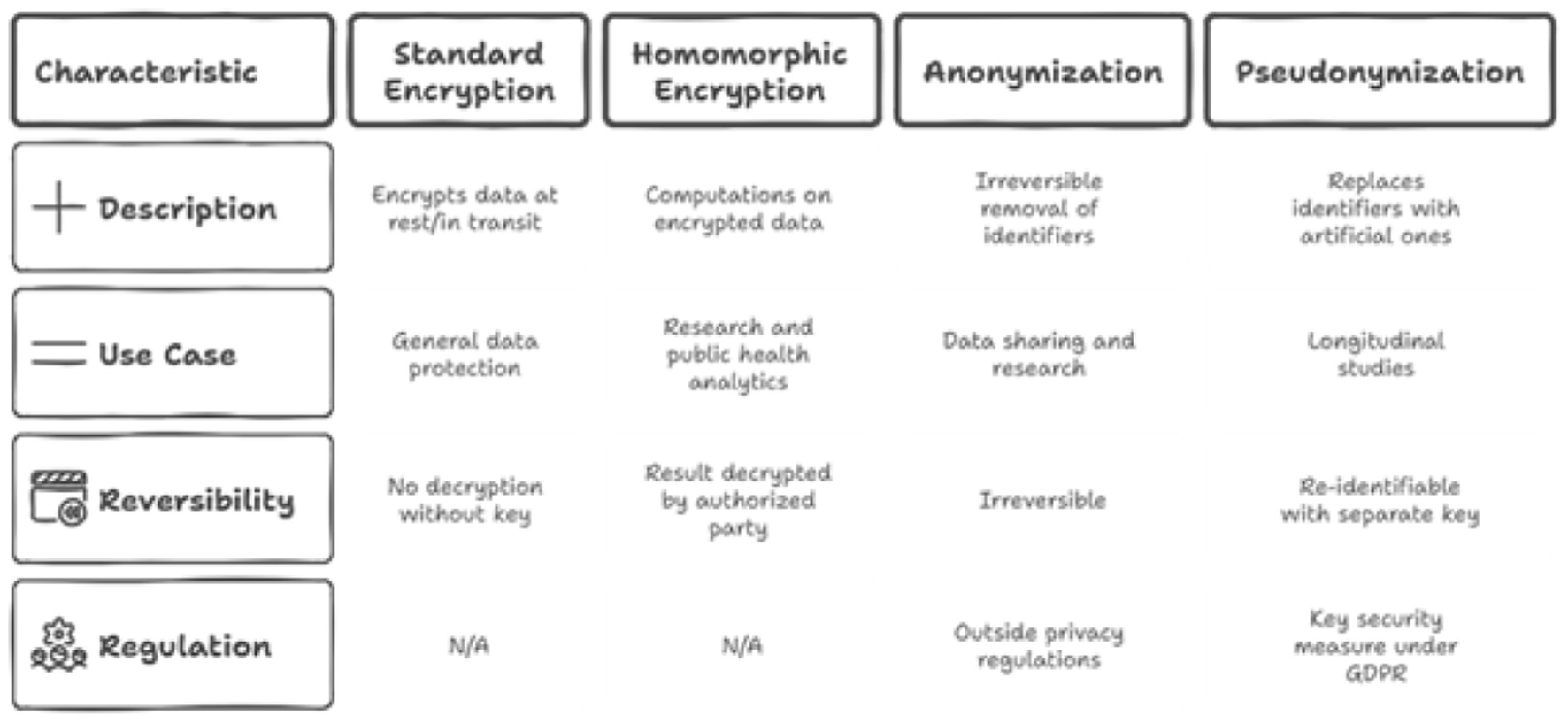

6.3 Advanced data protection: end-to-end encryption and privacy-preserving technologies

Protecting the confidentiality of patient data is a non-negotiable requirement especially in the environments like Sultanate of Oman. The AI based eguide platform must implement a multi-layered data protection strategy as shown in Figure 18 which contains the standard encryption (Huo and Wang, 2023), homomorphic encryption (Ahmed and Hrzic, 2025; Venkata et al., 2025), anonymization (Daly Manocchio et al., 2024) and the pseudonymization (Noé et al., 2022).

Figure 18

Data protection strategies for AI based eguide.

6.4 Ensuring accountability: blockchain-enabled tamper-proof audit mechanisms

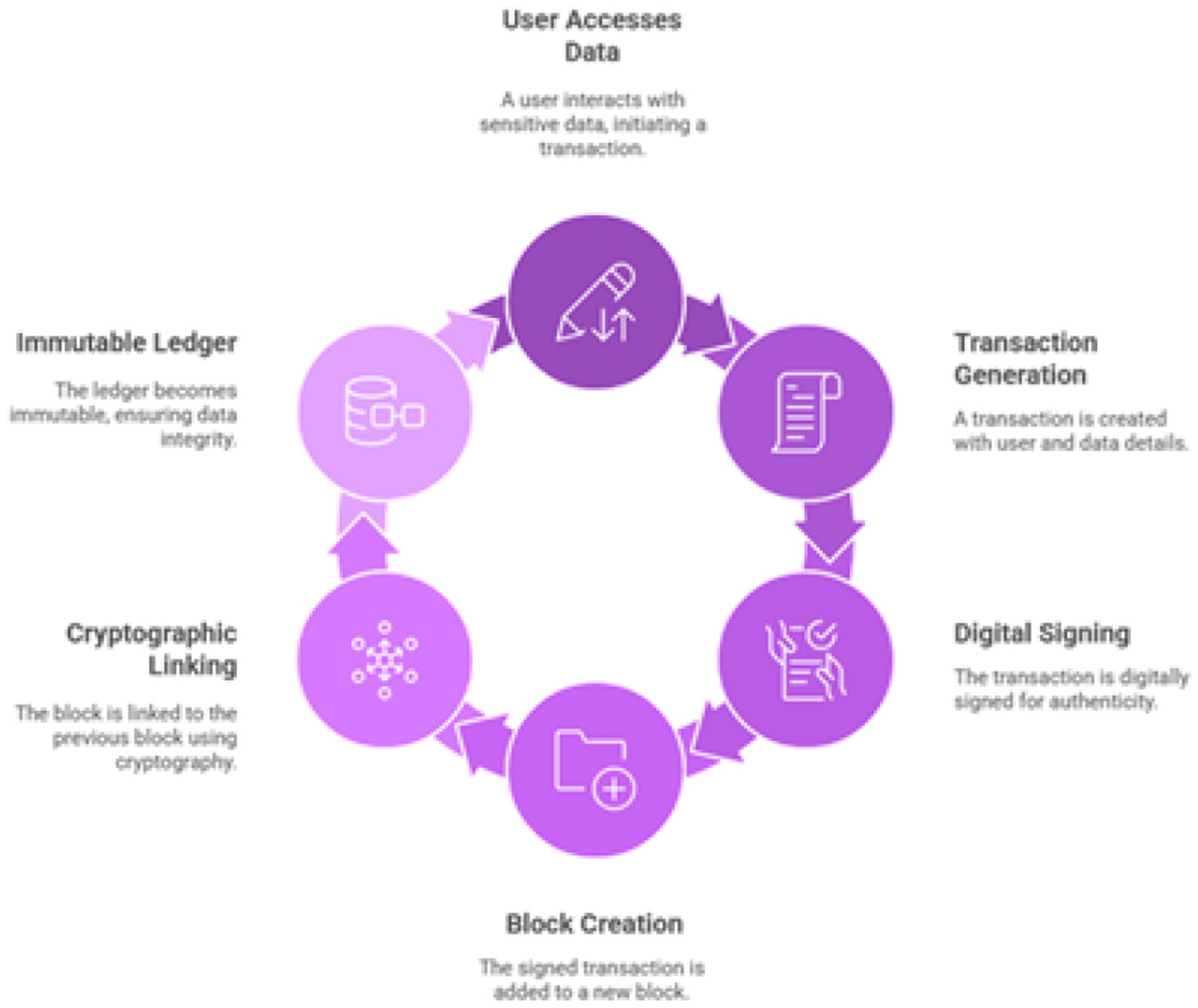

A fundamental requirement for security and compliance is a reliable audit trail of all access to sensitive data. However, traditional log files stored in a database or on a server can be modified or deleted by a privileged attacker (such as a compromised system administrator) to erase their tracks. A block chain based audit trail cycle is proposed for the current system as shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19

Blockchain-based audit trail cycle.

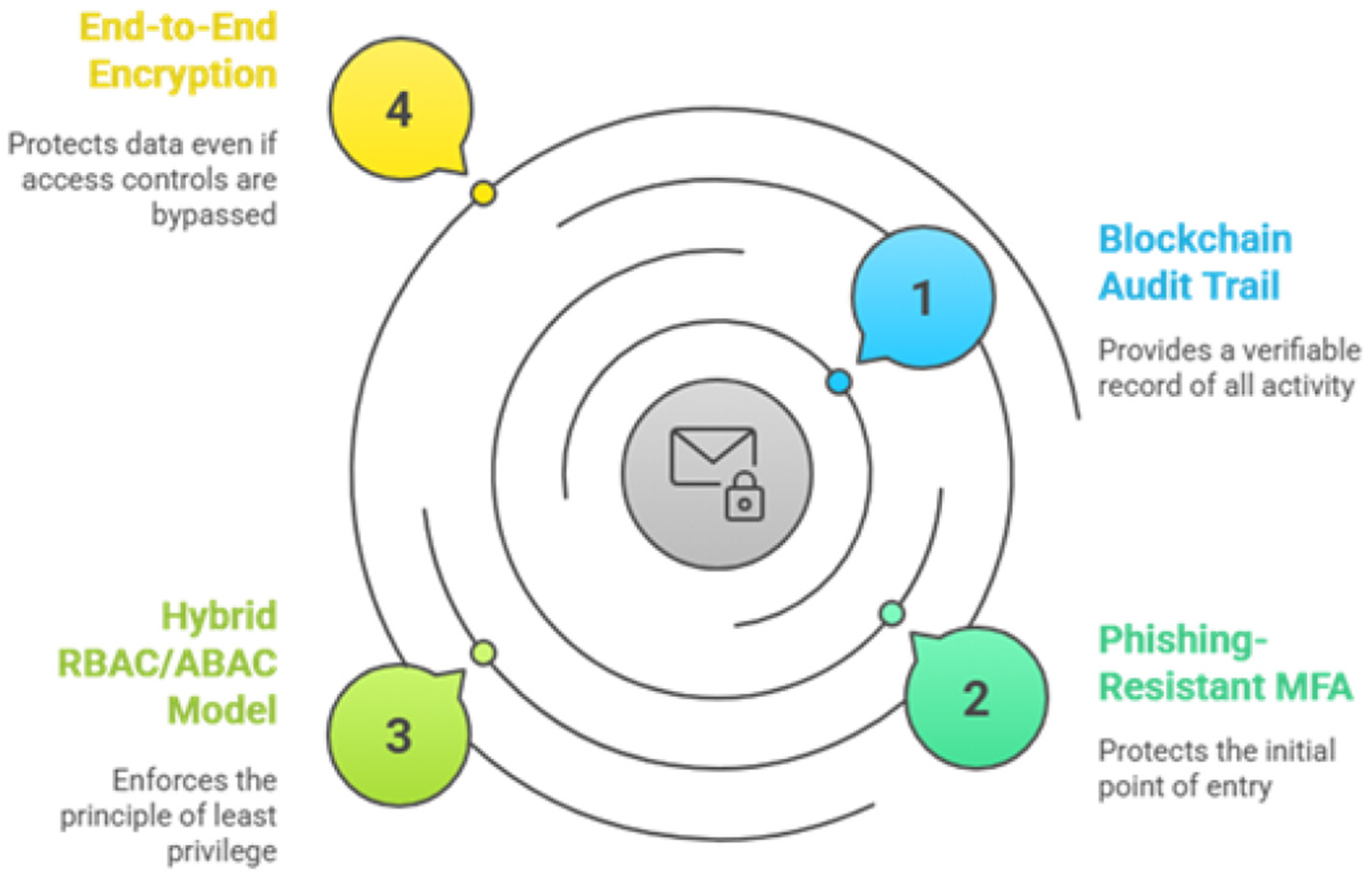

To create a truly immutable and non-repudiable audit trail, this strategy proposes the use of a private, permissioned blockchain network such as Hyperledger Fabric (Nedakovic et al., 2023). There are two types of the ledger including immutable ledger and cryptographic verification. In Immutable Ledger, every time a user accesses or modifies a patient record in AI based eguide, a transaction is generated. This transaction, containing details of the user, the patient data accessed, the timestamp, and the action performed, is digitally signed and added to a distributed, append-only ledger. Whereas in cryptographic Verification, each block of transactions is cryptographically linked to the previous one, forming a chain. Phishing-resistant MFA protects the initial point of entry. The hybrid RBAC/ABAC model enforces the principle of least privilege, limiting what an authenticated user can do. End-to-end encryption protects the data itself, even if access controls are somehow bypassed. Finally, the blockchain audit trail provides an immutable record of all actions, ensuring that even a successful breach is detected and can be fully investigated. This layered approach ensures that the security of AI based eguide for healthcare centers of Oman is not dependent on any single control, creating a far more resilient and trustworthy system for the healthcare system of Sultanate of Oman. A panorama of these security primitives is shown in Figure 20.

Figure 20

AI based eguide security primitives.

7 Multi-platform security review and fortification

The security of the AI based eguide application is intrinsically linked to the security of the underlying platforms on which it operates. A comprehensive security strategy must therefore address the entire technology stack, from server operating systems and endpoints to cloud infrastructure and connected medical devices.

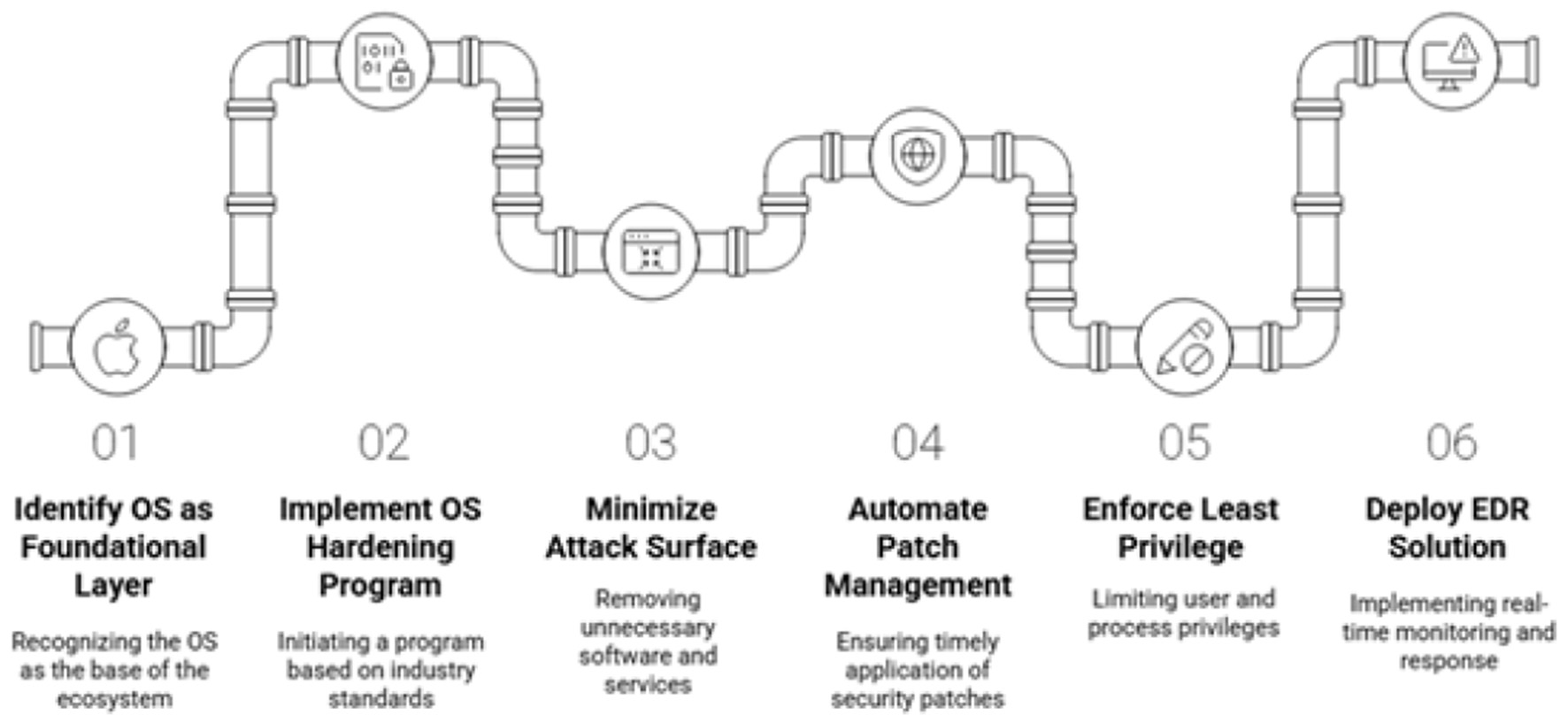

7.1 Hardening the foundation: secure configurations for operating systems and endpoints

The operating systems (OS) on servers and endpoints (e.g., clinical workstations, administrative PCs) form the foundational layer of the AI based eguide ecosystem. A compromise at this level can undermine all application-level security controls. A mandatory OS hardening program must be implemented for such system, based on recognized industry standards such as the Center for Internet Security (CIS) Benchmarks. The proposed hardening cycle of OS is illustrated in Figure 21.

Figure 21

OS hardening and security measures.

Key OS hardening practices proposed for AI eguide for healthcare centers include various approaches,

-

Minimizing the attack surface: removing all unnecessary software, services, libraries, and network ports from servers and endpoints. Every running service is a potential entry point for an attacker, in this case, the software and services which are connected to AI central guide to stop the possible entries of the attackers.

-

Automated patch management: in case of any attack, implementing a robust system to ensure that all security patches for the OS and third-party software are applied promptly will ensure the hardening of the system. Unpatched vulnerabilities are a leading cause of security breaches.

-

Principle of Least Privilege (PoLP): in case of AI central eguide for healthcare enters database, it must be ensuring that user accounts and system processes run with the minimum level of privilege required for their function. Administrative privileges must be tightly controlled and monitored.

-

Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR): deploying an EDR solution on all endpoints is critical for defending against advanced threats like ransomware. EDR tools provide real-time monitoring of endpoint activity, using behavioral analysis to detect suspicious patterns. Upon detecting a threat, an EDR solution can automatically respond by isolating the infected device from the network, preventing the threat from spreading to other systems.

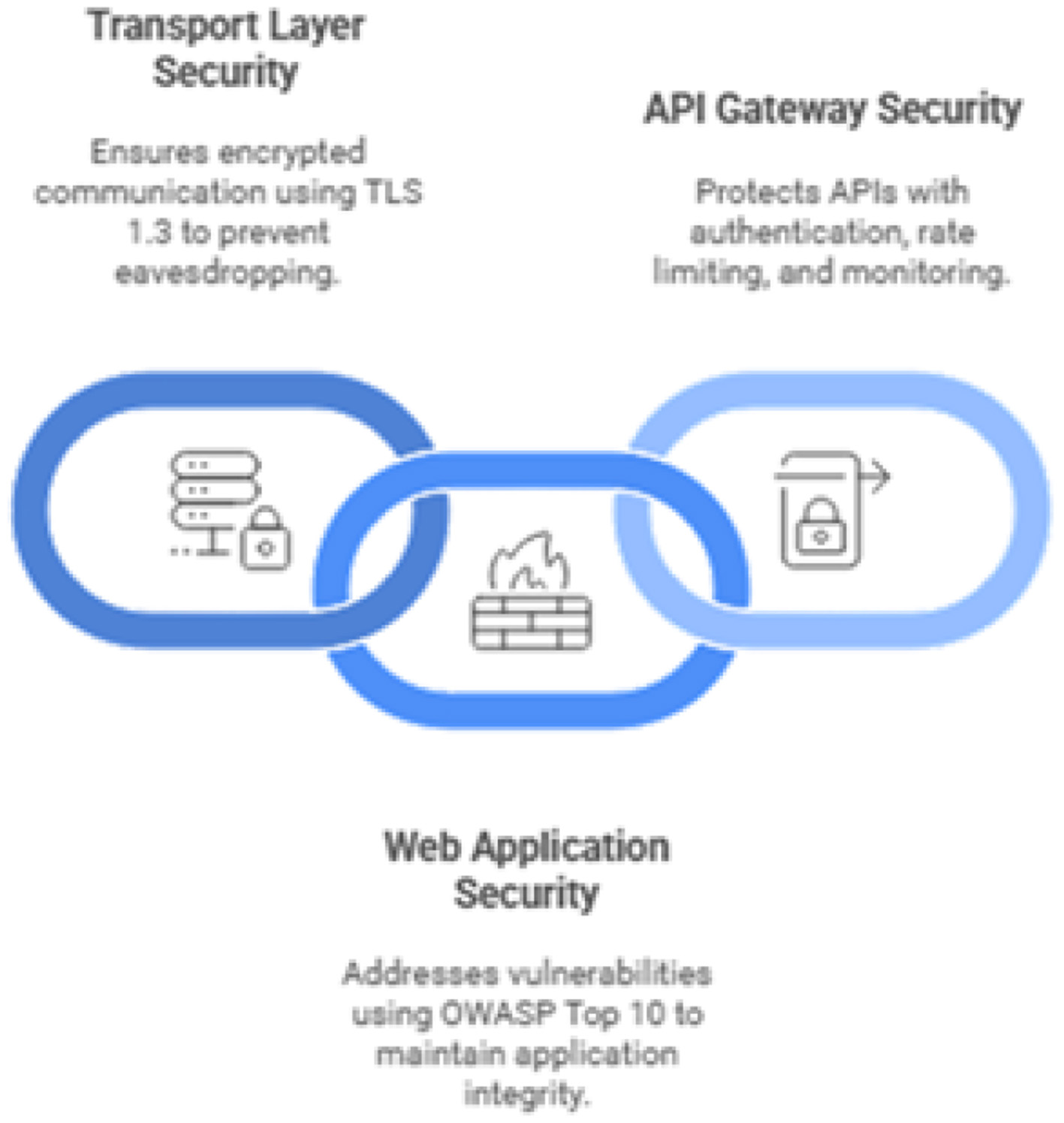

7.2 Securing communications: advanced web security protocols and API gateways

As a web-based platform, AI based eguide's communications must be secured against eavesdropping and manipulation. The digital infrastructure of securing AI based eguide is presented in Figure 22.

Figure 22

Securing AI based eguide's digital infrastructure.

-

Transport layer security (TLS): All web traffic to and from the AI based eguide platform must be encrypted using the latest version of the TLS protocol, currently TLS 1.3. Older, vulnerable versions such as SSLv3, TLS 1.0, and TLS 1.1 must be disabled at the server level to prevent downgrade attacks (Rubio et al., 2024). Server configurations should also enforce the use of strong cipher suites and key exchange mechanisms that support Perfect Forward Secrecy (PFS).

-

Web application security (OWASP Top 10): The AI based eguide mobile application and web application and its APIs must be regularly assessed for vulnerabilities outlined in the OWASP Top 10 list.

-

API gateway security: All health care standards like HL7FHIR (Gazzarata et al., 2024) and all other APIs must be supproted by the one of the main API called central API. For the detection of the anomalies and potential attacks, traffic logging and Monitoring is also provided (Rubio et al., 2024).

7.3 Mitigating risk in the cloud: a security blueprint for hybrid cloud deployments

Regarding our proposed system AI eguid, resilience and scalability can be achieved through the hybrid cloud model employing public cloud services as well as the on-premise data centers (El-Khoury and Saleh, 2025). While the cloud offers significant benefits, it also introduces new security challenges, with misconfigurations being a leading cause of cloud-based data breaches (Alshammari, 2025). The proposed hybrid cloud-based security for AI based eguide is shown in Figure 23.

Figure 23

Securing AI based eguide's hybrid cloud.

The cloud security strategy must address:

-

Cloud security posture management (CSPM): Deploying CSPM tools to continuously scan cloud environments for misconfigurations. Common and dangerous misconfigurations include unrestricted inbound/outbound network ports (e.g., open RDP or SSH ports), overly permissive Identity and Access Management (IAM) policies, and publicly accessible storage buckets.

7.4 Securing the edge: a lifecycle approach for embedded systems in IoMT devices

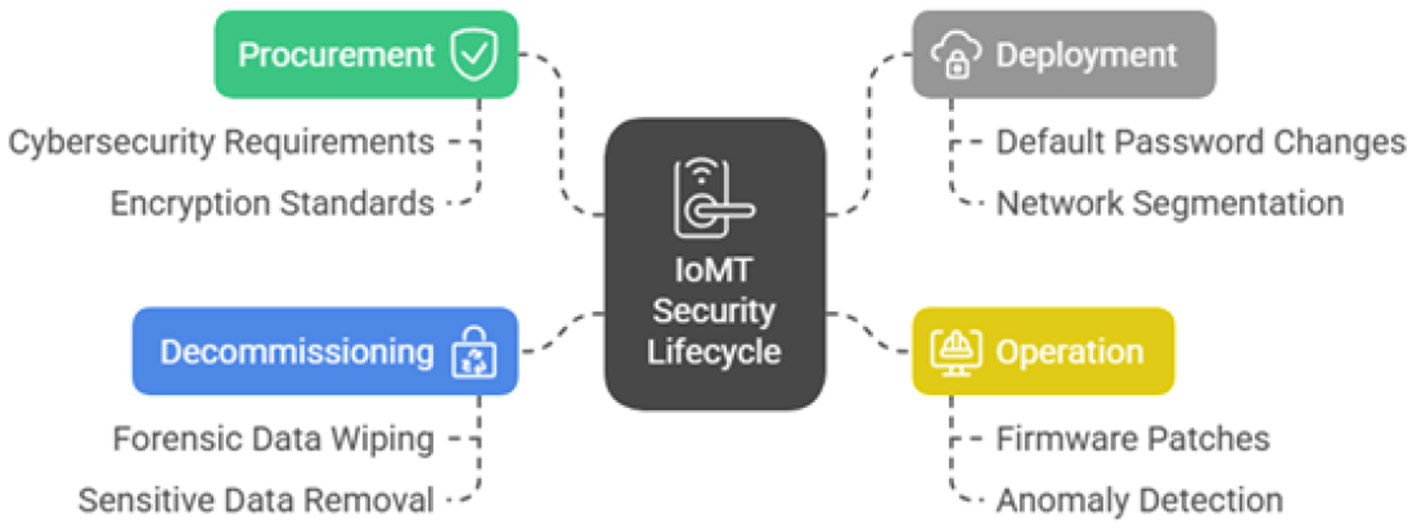

The rapid expansion of IoMT also calls for attacks in hospitals. various IoMT devices, are embedded in the network which may impact directly on the patient and patient's data (Fleming et al., 2025). A comprehensive, lifecycle-based approach to IoMT security is essential for the AI guide and in country like Oman. The comprehensive IoMT security lifecycle in healthcare is presented in Figure 24.

Figure 24

IoMT security lifecycle in healthcare.

-

Procurement: security must be a primary consideration during the purchasing process. All procurement contracts for IoMT devices must include specific cybersecurity requirements, such as the ability to be patched, support for modern encryption standards, and the absence of hardcoded default credentials.

-

Deployment: before being connected to the network, every IoMT device must be properly configured so that it can be easily connected to the main system of AI based eguide. This includes changing all default passwords, disabling any unnecessary network services, and placing the device on a segmented network isolated from critical systems and the general hospital network.

-

Operation: a continuous monitoring and maintenance program must be in place as much of the capital has been invested and also planned for the future. This includes applying firmware patches as they are released by the vendor and using network monitoring and EDR tools to detect anomalous behavior that could indicate a compromise.

Securing these platforms cannot be done in silos. A sophisticated attacker will not limit themselves to a single domain. A realistic attack path could begin by exploiting a known vulnerability in an unpatched, legacy IoMT device on a clinical ward (Saad Awadh Alanazi and Ahmad, 2025). From this foothold, the attacker could pivot to the cloud backend service that the device communicates with. Once in the cloud environment, they could exploit a subtle IAM misconfiguration to escalate their privileges (Saad Awadh Alanazi and Ahmad, 2025). Finally, using these elevated privileges, they could launch an attack from the now-trusted cloud environment against the core on-premises EHR database. This converged threat scenario demonstrates that a holistic security strategy is essential. Controls like network micro-segmentation and the “never trust, always verify” principle of ZTA are not just best practices for a single platform but are critical for breaking these dangerous cross-domain attack chains and securing the entire AI based eguide ecosystem.

8 Simulated black-box and gray-box penetration testing methodology

This section details the results of a simulated penetration test conducted against a representative deployment of the AI based eguide Smart Medical Record Management System (SMRMS). The primary objective of this assessment is to provide practical, evidence-based validation for the strategic recommendations outlined in this report. By proactively identifying and exploiting security vulnerabilities in a controlled environment, this test demonstrates how the absence of a Zero Trust Architecture, advanced security primitives, and a continuous validation framework manifests as critical, tangible risks to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of patient data and clinical operations. The findings herein serve as a direct justification for the proposed architectural and procedural transformations. Proposed penetration sequence is shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25

Penetration test sequence for AI based eguide SMRMS.

8.1 Scope

The target of evaluation (ToE) for this assessment was a locally hosted instance of the AI based eguide SMRMS, deployed on a server with the IP address 10.10.1.125. The scope of the test was limited to the web application and its underlying services, focusing on key functional modules identified as high-risk due to the sensitivity of the data they process. These modules include User Authentication and Session Management, Patient Record Creation, Access, and Modification and System Audit and Activity Logging Functions. Out of scope for this assessment were denial-of-service attacks, social engineering of Ministry of Health personnel, and physical security assessments of the hosting facility.

8.2 Methodology

A hybrid testing methodology was adopted to provide a comprehensive view of the SMRMS security posture from two distinct adversarial perspectives. This approach combines black-box and gray-box testing phases to simulate a realistic, multi-stage attack campaign.

The structure of this two-phased test is deliberate. The black-box phase reveals weaknesses at the perimeter, while the subsequent gray-box phase demonstrates that even if the perimeter is breached, robust internal controls are essential to prevent catastrophic damage. This progression provides a powerful argument against the legacy “castle-and-moat” security model and directly validates the core never trust, always verify principle of the Zero Trust Architecture advocated in previous task namely Secure Design Assessment and Architectural Enhancements.

8.3 Test environment

All penetration testing activities were conducted by a dedicated attacker machine configured to mirror a typical offensive security setup. The environment consisted of Kali Linux (2025.2 Release) operating System and Oracle VM VirtualBox 7.0 hypervisor. For the network configuration we used the attacker virtual machine and the target SMRMS server (10.10.1.125) were located on an isolated virtual network to ensure that all testing activities were contained and posed no risk to live production systems.

8.4 Phase 1: black-box assessment

The black box assessment is also called the unauthenticated attacker. This phase simulates an external adversary's initial reconnaissance and exploitation attempts against the public-facing components of the AI based eguide SMRMS.

8.4.1 Network and service reconnaissance

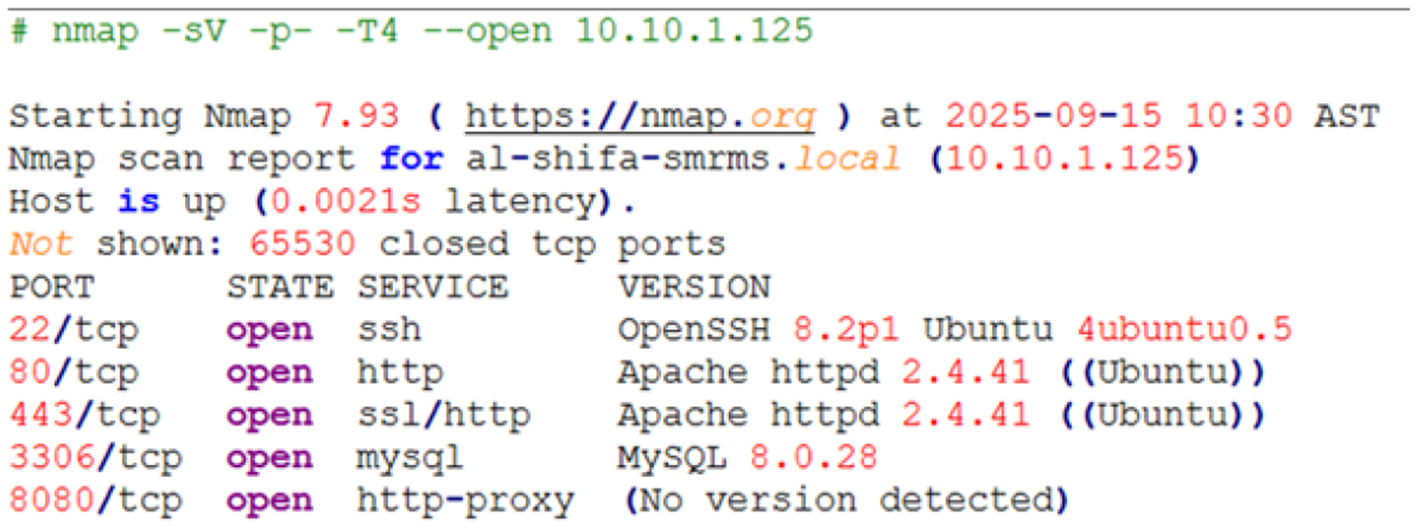

The following output was generated by Nmap as shown in Figure 26.

Figure 26

Nmap result.

Analysis: The scan reveals five open TCP ports, presenting a significant and unnecessarily large attack surface. While the web servers on ports 80 and 443 are expected, the exposure of SSH (port 22) and especially the MySQL database (port 3306) to the network is a critical configuration flaw. Untrusted networks must not be used for the access of the database services. Firewalls must be installed so that only application server can accept the authenticated connections.

8.4.2 Authentication mechanism analysis: username enumeration and brute-force susceptibility

The SMRMS login page at https://10.10.1.125/login was analyzed for weaknesses that could facilitate unauthorized access. The Burp Suite web proxy tool was used to intercept and manipulate login requests. Finding 1: username enumeration The application was found to provide different responses for invalid usernames vs. invalid passwords, allowing an attacker to confirm the existence of valid user accounts. Cases for the user enumeration is shown in Figure 27.

Figure 27

Username enumeration messages.

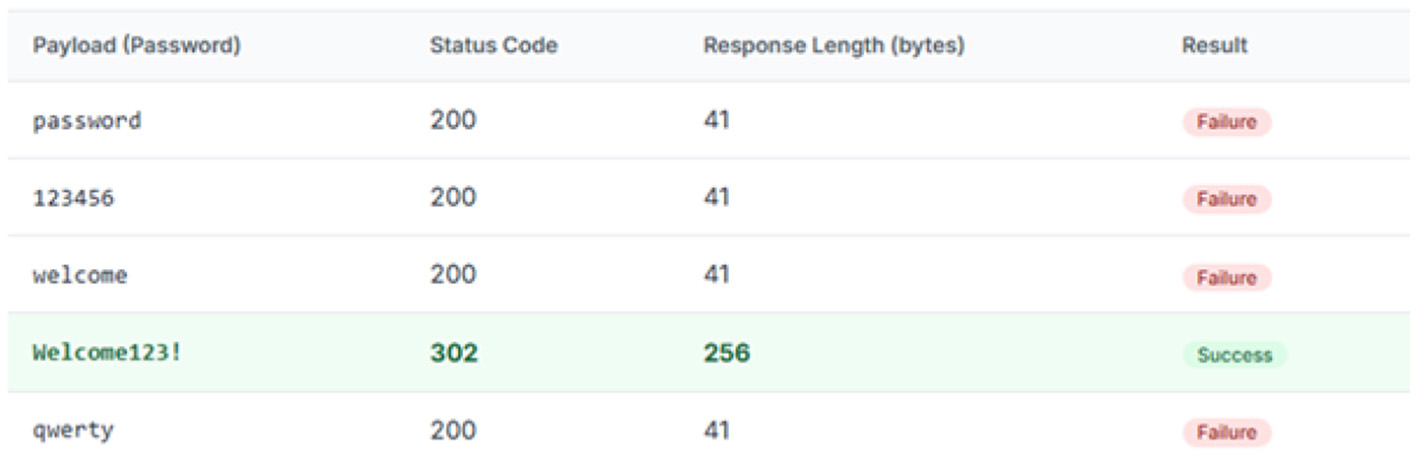

Finding 2: susceptibility to brute-force attack The login mechanism did not implement any account lockout policy after multiple failed attempts. This allowed for a password brute-force attack to be mounted against a known-valid username (r.ahmed) using Burp Intruder as shown in Figure 28. The following Figure 28 (Table as screenshot) summarizes the results of a targeted Burp Intruder attack.

Figure 28

Results of a targeted Burp Intruder attack.

Analysis The username enumeration vulnerability allows an attacker to compile a list of valid accounts, which is a violation of user privacy and provides a target list for further attacks. The lack of an account lockout policy is a critical failure of the “Technological Controls” outlined in the ISO 27002 framework assessment and evaluations. Together, these flaws significantly lower the bar for an attacker to gain unauthorized access through password guessing or spraying attacks.

8.4.3 Exploitation: authentication bypass via SQL Injection (SQLi)

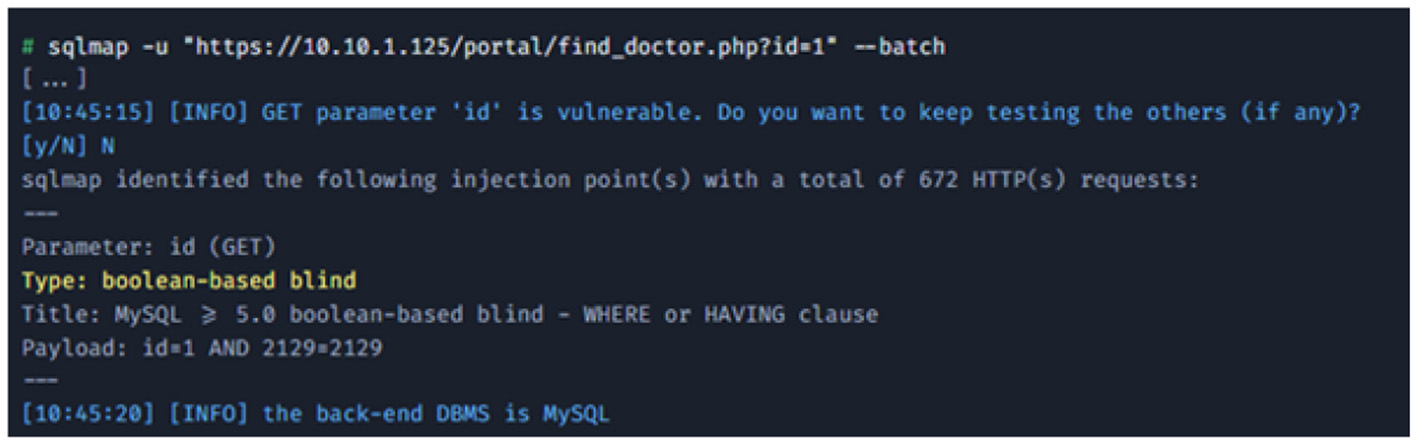

Further investigation of the application's unauthenticated features revealed a public-facing find a doctor search page as shown in Figure 29. The id parameter in this feature was tested for SQL injection vulnerabilities using the automated tool sqlmap.

Figure 29

Vulnerability discovery.

-

Vulnerability discovery: sqlmap was used to test the target URL. It quickly confirmed that the id parameter was injectable.

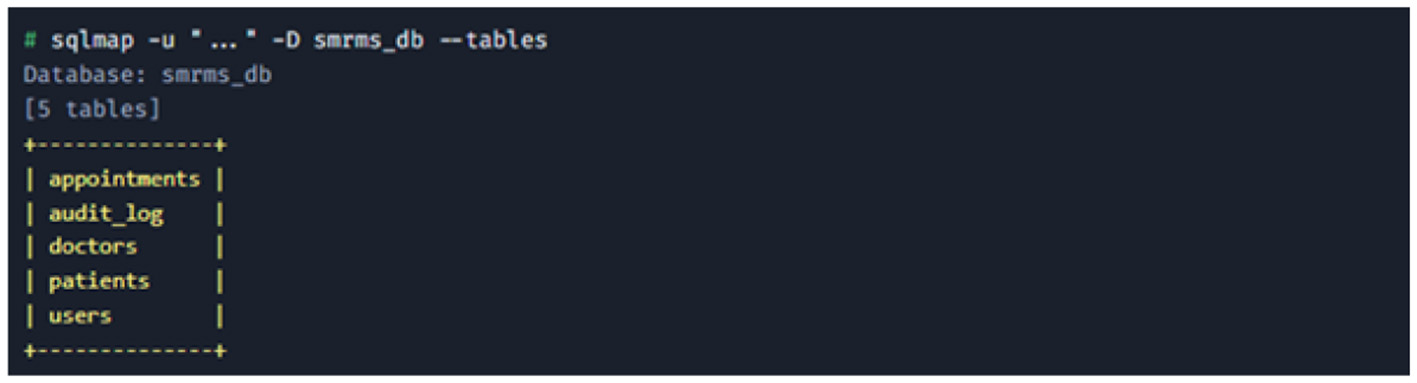

-

Database enumeration: having confirmed the vulnerability, sqlmap was used to enumerate the databases and tables as shown in Figure 30.

-

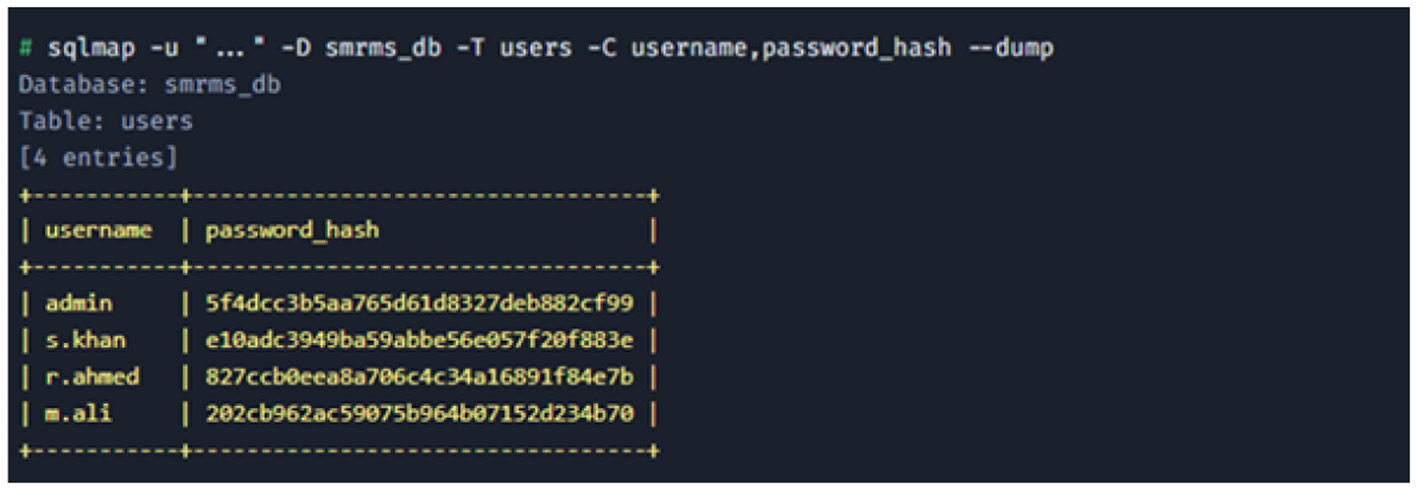

User credential exfiltration: the final step was to dump the contents of the users table to retrieve usernames and password hashes as shown in Figure 31.

Figure 30

Database enumeration.

Figure 31

User credential exfiltration.

Analysis This finding is rated Critical. It represents a complete failure of input validation, a foundational secure coding practice. The vulnerability allows an unauthenticated attacker on the internet to bypass all security controls and exfiltrate the entire contents of the SMRMS database, including sensitive patient data and all user credentials. The use of weak MD5 hashes for password storage (e.g., e10adc3949ba59abbe56e057f20f883e is the hash for 123456) means these credentials can be trivially cracked and used for further access. This vulnerability provides a direct pathway for an external attacker to gain authenticated access, serving as the logical and realistic entry point for the gray-box phase of this assessment.

8.5 Phase 2: gray-box assessment

The Gray Box assessment is also called the compromised insider. This phase assumes the attacker has used the credentials obtained via the SQL injection attack to log in as the low-privilege user r.ahmed (a receptionist account). The objective is to assess the effectiveness of internal security controls from the perspective of an authenticated user.

8.5.1 Authorization flaw: insecure direct object reference (IDOR) in patient records

After logging in as r.ahmed, the application allows viewing of patient records assigned to that user. The request to view a record was captured in Burp Suite. The URL format was observed to be https://10.10.1.125/records/view?patient_id=1052. This request was sent to Burp Repeater to test if the patient_id parameter could be manipulated to access records not assigned to r.ahmed. Evidence: The following HTTP requests and server responses demonstrate a critical authorization failure.

-

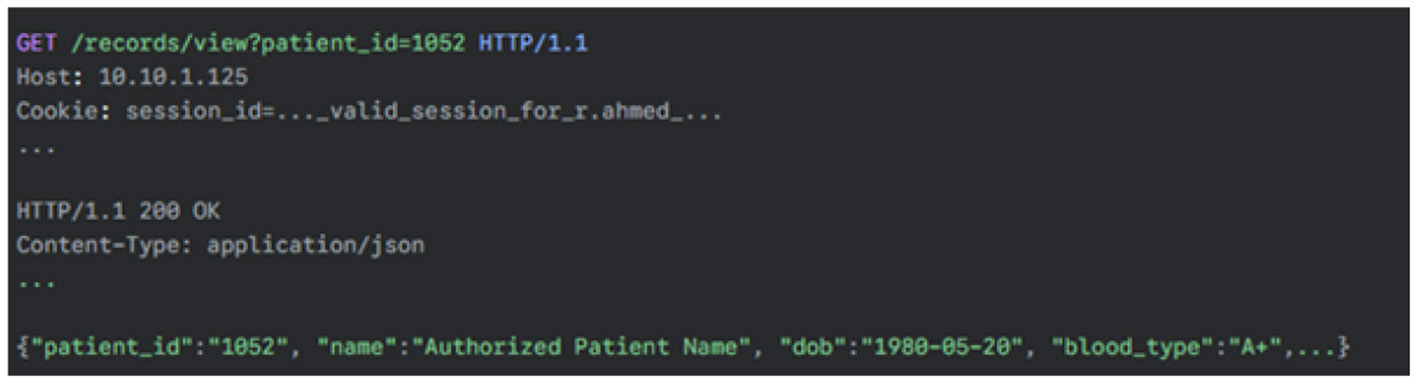

Legitimate request: The user requests a patient record they are authorized to view (patient_id=1052). The server correctly returns the patient's data as shown in Figure 32.

-

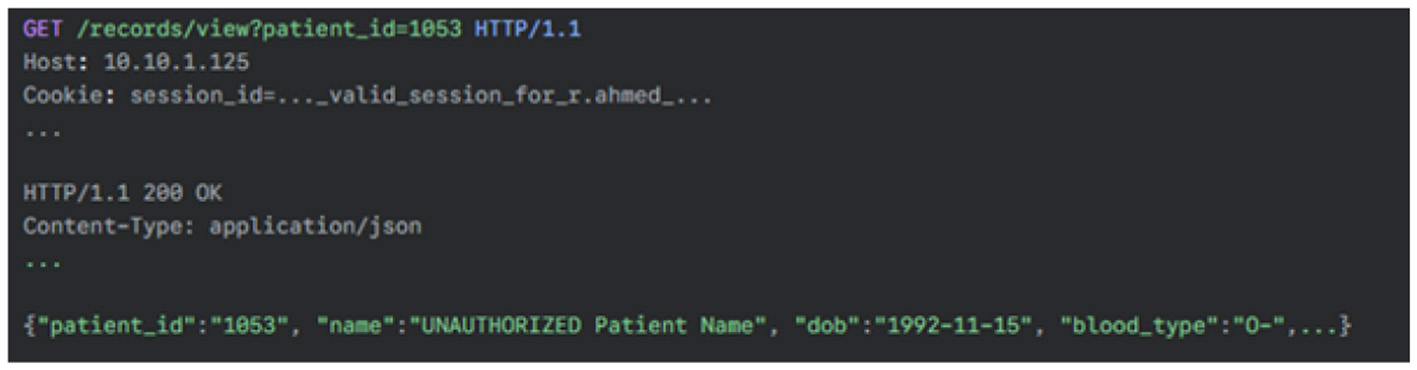

Malicious request (IDOR): The attacker modifies the patient_id to 1053, a record not assigned to r.ahmed. The server incorrectly processes the request and returns the sensitive data for the unauthorized patient as shown in Figure 33.

Figure 32

HTTP legitimate request.

Figure 33

Malicious request.

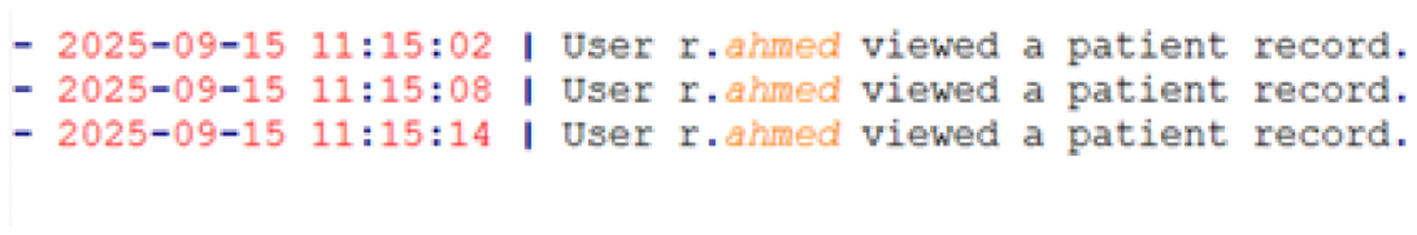

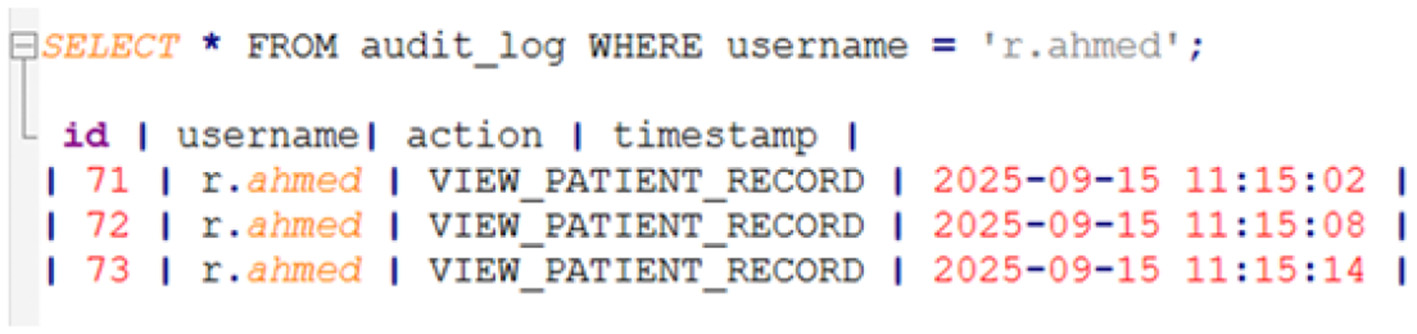

8.5.2 Audit and accountability failure: insufficient and mutable logging

To assess the systemś ability to detect the IDOR attack, the applicationś Audit Trail feature was reviewed after accessing multiple unauthorized patient records. Additionally, the audit_log table in the database (accessible via the SQLi vulnerability) was inspected.

-

User-facing audit log: the log available in the application's UI contained only vague, high-level entries. It confirmed that the user viewed records but failed to capture the most critical piece of information: which records were viewed and presented in Figure 34.

-

Database audit table (audit_log): direct inspection of the database revealed the same insufficient level of detail, confirming this is a systemic design flaw given in Figure 35.

Analysis: the audit trail is critically insufficient for security and compliance purposes. Its failure to log the specific object identifier (patient_id) makes it impossible to conduct a forensic investigation or determine the scope of a data breach. An administrator reviewing these logs would have no way of knowing that unauthorized data access had occurred. Furthermore, because the logs are stored in a standard, mutable SQL table, an attacker with database access (as achieved via SMRMS-001) could easily modify or delete these entries to erase all evidence of their activity.

Figure 34

User-facing audit log.

Figure 35

Database audit table.

8.6 Summary of findings and risk analysis

From mediuum to critical severity level of vulnerabilities have been found during the penetration testing. The score for common vulnerability scoring system was obtained as v3.1 mapping to the Top 10 categories of 2021 as the OWASP. Table 3 explains the summary of penetration testing. Four vulnerabilities classes have been identified a a perspective of the quantitative aspects. Out of these two classes, two of them achieved v3.1 scores exceeding 8.8 resulting severe risk to availability, integrity and the confidentiality. The high severity exploit ability is also connected with zero trust architecture. Architecture level weaknesses and vulnerabilities are addressed in this proposed framework which eliminates entirely these vulnerabilities category rather than reducing them.

Table 3

| Finding ID | Vulnerability name | OWASP top 10 category (2021) | CVSS 3.1 score & vector | Severity | Business & clinical impact summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMRMS-001 | Authenti-cation bypass via SQL injection | A03: injection | 9.8 (CVSS:3.1/AV: N/AC:L/PR:N /UI:N/S:U/C: H/I:H/A:H) | Critical | Complete compromise of database confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Mass data leakage of all patient and user data. Direct violation of PDPL, GDPR, and HIPAA. |

| SMRMS-002 | Broken authorization (IDOR) | A01: broken access control | 8.8 (CVSS:3.1/AV: N/AC:L/PR:L /UI:N/S:U/C: H/I:H/A:N) | Critical | Any authenticated user can access and potentially alter any patient record, leading to catastrophic patient safety risks (e.g., incorrect diagnosis or medication) and massive regulatory fines. |

| SMRMS-003 | Insufficient and mutable audit trail | A09: security logging and monitoring failures | 7.5 (CVSS:3.1/AV: N/AC:L/PR:H /UI:N/S:U/ C:H/I:H/A:N) | High | Inability to detect or investigate data breaches, rendering incident response ineffective. Prevents accountability and non-repudiation, allowing attackers to operate undetected within the system. |

| SMRMS-004 | Username enumeration & weak lockout mechanism | A07: identification and authentication failures | 5.3 (CVSS:3.1/AV: N/AC:L/PR:N /UI:N/S:U/ C:L/I:N/A:N) | Medium | Facilitates targeted brute-force and password-spraying attacks, increasing the likelihood of account compromise, particularly following phishing campaigns. |

Summary of penetration test findings.

8.7 Summary of quantitative security outcomes

From a quantitative perspective, the evaluation identified four distinct vulnerability classes, including two critical vulnerabilities with CVSS v3.1 scores of 9.8 (authentication bypass via SQL injection) and 8.8 (broken authorization through IDOR), indicating severe risk to confidentiality, integrity, and availability. A further high-severity vulnerability (CVSS 7.5) related to insufficient and mutable audit logging and a medium-severity issue (CVSS 5.3) involving authentication hardening gaps were also observed. A high quality exploit ability has been shown in overall findings. The proposed design framework mitigates quantitatively most of the risks and vulnerability classes by implementing ZTA and duly verifiyd by the ABAC and RBAC authentication and other evidence based audit trails. A measurable evidence of the cybernetics resilience has been proposed by the national level health care infrastructure.

9 Detailed vulnerability analysis and strategic remediation

9.1 SMRMS-001: authentication bypass via SQL injection

9.1.1 Technical description

The application's find_doctor.php script is vulnerable to SQL injections. The root cause is the unsafe practice of dynamically constructing an SQL query by concatenating raw, unvalidated user input from the id GET parameter directly into the SQL statement string. An attacker can manipulate this parameter to inject malicious SQL syntax, altering the logic of the original query to exfiltrate data from the database.

9.2 SMRMS-002: broken authorization (IDOR)

9.2.1 Technical description

The applicationś (AI based central eguide for healthcare centers of Oman) endpoint for viewing patient records (/records/view) fails to perform an authorization check. While it correctly verifies that the user is authenticated (has a valid session), it does not verify that the authenticated user has the specific right to access the patient record requested via the patient_id parameter. The system implicitly trusts that if a user is logged in, they are authorized to request any object by simply changing the identifier in the URL. Table 4 shows the control themes and their application to the AI based eguide platform. Table 5 illustrates the comparative analysis of RBAC and ABAC models in the AI based eguide context.

Table 4

| ISO 27002:2022 theme | Description | Specific AI based eguide application examples |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational controls (clause 5) | High-level policies, processes, and rules that govern information security across the organization. | Development of a formal “”Information Security Policy for AI based eguide “”. - Asset management policy to classify all patient data as “”Confidential“”. - Security requirements for third-party vendors, including IoMT device manufacturers. |

| People controls (clause 6) | Controls related to human factors, including awareness, training, and personnel security. | Mandatory annual cybersecurity and phishing awareness training for all MOH staff. - Role-based security training tailored to clinicians, administrators, and IT personnel. - Formal background screening processes for all personnel with privileged access to AI based eguide. |

| Physical controls (clause 7) | Measures to protect physical assets, such as data centers, equipment, and storage media. | Multi-factor physical access controls (e.g., biometrics) for data centers hosting AI based eguide servers. - Secure disposal procedures for storage media from decommissioned medical devices and workstations, ensuring no residual patient data remains. - Clear desk and clear screen policies for all workstations accessing EHRs. |

| Technological controls (clause 8) | Technical safeguards are implemented in hardware and software to protect information systems. | Implementation of strong cryptography for all patient data at rest and in transit. - Enforcement of robust access control mechanisms (MFA, RBAC/ABAC). - Deployment of tamper-proof audit logging and monitoring systems. - Integration of security into the software development lifecycle (DevSecOps). |

ISO 27002:2022 control themes and their application to the AI based eguide platform.

Table 5

| Feature | Role-based access control (RBAC) | Attribute-based access control (ABAC) | Recommendation for AI based eguide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Granularity | Coarse-grained; permissions are tied to a user's role. | Fine-grained; permissions are based on real-time attributes of the user, resource, and environment (Huang, 2025). | Hybrid approach: Use RBAC for broad roles and ABAC for specific, sensitive data access. |

| Flexibility | Static; requires creation of new roles to grant new permissions, leading to role explosion. | Dynamic; policies can adapt to changing contexts without creating new roles (De Carvalho Junior and Bandiera-Paiva, 2018). | ABAC provides the necessary flexibility for a modern healthcare system. |

| Management complexity | Simpler to implement and manage in small, static organizations (Huang, 2025). | More complex to design and implement initial policies. | The initial complexity of ABAC is justified by its superior security and flexibility. |

| Emergency access (“break glass”) | Difficult to model; often requires a manual, temporary role assignment which is slow and error-prone. | Natively supported via environmental attributes (e.g., emergency_flag=true) in a policy, enabling audited, time-limited access. | ABAC is essential for securely managing emergency access scenarios. |

| Telemedicine and remote access | A “Doctor” role has the same permissions regardless of location or device. | Can enforce policies like “Deny access to full EHR if network_location=public_wifi or device_posture = unmanaged.” | ABAC is critical for securing the expanding telehealth attack surface. |

Comparative analysis of RBAC and ABAC models in the AI based eguide context.

9.2.2 Proof of concept

The evidence in Section 6.5.1 shows an authenticated user (r.ahmed) successfully requesting and receiving the full medical record for patient_id=1053, a patient to whom they have no clinical relationship, simply by manipulating the URL parameter.

9.2.3 Comprehensive impact analysis

-

Technical impact: any authenticated user, regardless of their privilege level, can systematically iterate through patient_id values to access and exfiltrate every single patient record in the SMRMS.

-

Clinical/patient safety impact: beyond confidentiality breaches, an attacker could use this flaw to access the records of high-profile individuals for blackmail or espionage. If write access is similarly flawed, an attacker could alter medical records, leading to misdiagnosis or incorrect treatment, posing a direct threat to patient safety.

-

Regulatory impact: this represents a catastrophic failure of access control, which is a core requirement of HIPAA's Security Rule and the data protection principles of GDPR and PDPL. The inability to restrict access to PHI on a need-to-know basis would result in severe compliance violations.

9.2.4 Strategic remediation roadmap

-

Tactical (immediate): for every request to access a patient record, the application logic must be modified to perform an explicit authorization check. The code must verify that a relationship exists between the currently logged-in user and the requested patient_id before returning any data.

-

Strategic (architectural): this finding is a direct consequence of an inadequate, implicit authorization model. The definitive strategic remediation is the full implementation of the formally verified hybrid RBAC and ABAC model detailed in design and formal verification. An ABAC policy would deny access by default and only permit it if a specific rule is met, such as: “Permit access if user.role is 'Doctor' AND resource.patient_id is present in user.assigned_patients.” This enforces the principle of least privilege at a granular level and eliminates the entire class of IDOR vulnerabilities.

9.3 SMRMS-003: insufficient and mutable audit trail

9.3.1 Technical description

The system's audit logging mechanism fails on two critical fronts. First, the log entries are insufficiently detailed; they record that an action occurred (e.g., VIEW_PATIENT_RECORD) but omit the essential context of which object the action was performed on. Second, the logs are stored in a standard SQL database table, making them mutable and subject to tampering or deletion by any attacker who gains privileged database access.

9.3.2 Proof of concept

The evidence in Section Audit and accountability failure shows that after exploiting the IDOR vulnerability to view multiple unauthorized records, the audit log only contains generic, indistinguishable entries, making it impossible to identify the malicious activity.

9.3.3 Strategic remediation roadmap

-

Tactical (immediate): the application's logging function must be immediately updated to include detailed contextual information in every log event. For access events, this must include the source IP address, the authenticated username, the action performed, the specific object ID (patient_id), and a precise timestamp.

-

Strategic (architectural): the fundamental problem of mutability validates the necessity of the blockchain-enabled tamper-proof audit mechanism proposed in Framework design and architecture. By writing detailed audit events as transactions to a private, permissioned blockchain, the system can create a cryptographically verifiable and immutable ledger. Any attempt to alter a past log entry would be immediately detectable, providing the non-repudiation and integrity that is essential for a system designated as Critical National Infrastructure.

10 Strategic conclusion and roadmap for implementation

The well being of the citizens of Sultanate of Oman is the basic foundation provided by the security and resilience of the AI based eguide system. Traditional and contemperory attacks and threat patterns and persistent cyberattacks demand for a new strategic but beyond the tranditona, and reactive security responses to mitigate various risks and attacks. The recent incidents, though mitigated, serve as a clear directive: a proactive, deeply integrated, and multi-layered cybersecurity strategy is not an option, but a necessity. This study has detailed such a strategy, centered on a paradigm shift to Zero Trust Architecture. This approach, which replaces implicit trust with continuous verification, is the most effective way to protect a complex, interconnected ecosystem like AI based eguide from both external attacks and insider threats. By combining this modern architectural foundation with a robust ISO 27001-based management system (Culot et al., 2021), advanced and formally verified security primitives, comprehensive platform hardening, and a continuous cycle of rigorous testing, the Ministry of Health can build a platform that is not only secure by design but also demonstrably resilient in practice. The implementation of this comprehensive strategy is a significant undertaking that requires commitment, resources, and a phased approach. The current study proposes the high level road mad given below.

-

Phase 1: Foundational Hardening and Immediate Risk Mitigation (Months 1–6)

Action: Implement mandatory, phishing-resistant Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) for all users of the system.

Action: Conduct a comprehensive OS and application hardening initiative based on CIS benchmarks and remediate all critical vulnerabilities identified in the initial penetration test (e.g., SQLi, IDOR).

Action: Deploy Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) solutions across all clinical and administrative workstations.

Action: Establish the formal ISO 27001-based ISMS governance structure and initiate a full-scope risk assessment.

-

Phase 2: Architectural Evolution and Policy Formalization (Months 7–18)

Action: Design and pilot the Zero Trust Architecture in a limited, non-critical segment of the AI based eguide network.

Action: Formally model and verify the proposed hybrid RBAC/ABAC access control policy and the MFA protocol using theorem proving and model checking.

Action: Develop and deploy the API Gateway to secure all external and internal API communications.

Action: Begin development of the blockchain-based tamper-proof audit trail prototype.

-

Phase 3: Full ZTA Rollout and Continuous Security Operations (Months 19–36)

Action: Incrementally expand the ZTA micro-segmentation across the entire AI based eguide ecosystem.

Action: Fully deploy and integrate the blockchain audit trail, phasing out reliance on mutable local logs for critical events.

Action: Establish a mature Security Operations Center (SOC) with continuous monitoring capabilities, leveraging CSPM and EDR data.

Action: Institute a recurring schedule of internal audits, compliance reviews, and annual third-party penetration tests.

Ultimately, cybersecurity is not a one-time project but a continuous process of adaptation and improvement. It requires not only technological investment but also a cultural shift toward security awareness at every level of the organization. By embarking on this strategic path, the Ministry of Health of Sultanate of Oman will not only be protecting a critical IT system but will be safeguarding the trust of its citizens and ensuring the delivery of safe, effective, and uninterrupted healthcare for the Sultanate of Oman for years to come.

11 Limitations and future work

Some of the limitations must be acknowledge in the presence of a comprehensive scope of the current study. An intentional framework based on AI based eguide has been proposed and it is designed as security oriented decision support and governance and it is more than a data driven clinical prediction ro diagnostic tool. As there has been no any patient data has been employed, or no any inference mechanism has been used in model training so traditional machine learning metrics are not applicable. Black box and gray box penetration testing have been used for the evaluation within a controlled environment. These testing methods have produced effective results, by revealing most of the practical vulnerabilities and the weaknesses of architecture and such tests may not fully reveal the operational and large scale multinational health care deployments. longitudinal validation and live environments of health care will be point of focus for the future studies along with the continuous monitoring and adaptive risk assessment. The integration of privacy preserving machine learning approach and the integration of the explainable AI may also be explored in the future studies for the decisions which are not for clinical decision optimization, ethical and regulatory approvals. The extension of this work which supports interchangeability with existing, emerging national and international digital health systems resulting in an enhanced applicability of the cross borders.

12 Conclusion

The current study underscores the urgent need for a paradigm shift in securing Oman's AI-based eguide platform, moving beyond perimeter-based defenses toward a holistic Zero Trust framework. The study is all about the national health care infrastructure employed as one of the hot and frequency target of the cyberattaks which needs continuous validation and the verified security mechanism for the maintenance of the compliance, trustworthiness and the resilience. The research demonstrates that the Ministry of Health in Sultanate of Oman can achieve immediate system hardening through phased adoption of hybrid RBAC-ABAC models and audit trails based on blockchain, thereby guaranteeing accountability, privacy, and operational efficiency. Beyond technical innovation, the findings emphasize the importance of robust institutional governance supported by ISO/IEC 27000-based ISMS, rigorous compliance audits, and emission security protocols capable of countering sophisticated adversarial threats. Looking forward, future research should explore the integration of explainable AI into both security operations and clinical decision-making (Amiri et al., 2025) to enhance transparency and regulatory confidence, the development of scalable cloud-IoMT frameworks capable of enabling real-time monitoring and adaptive resilience during national crises, and the advancement of privacy-preserving analytics such as homomorphic encryption and federated learning to balance data utility with stringent patient privacy requirements. On the solutions of such problesm, Oman's healthcare sector can not only secure its critical digital infrastructure but also establish itself as a regional leader in safe, intelligent, and resilient healthcare transformation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AK: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. YM: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology. MB: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. DH: Software, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Validation. DG: Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Software, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding