- 1Karen Peterman Consulting, Co., Durham, NC, United States

- 2Department of Statistics, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 3The Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance, Augusta, ME, United States

This case study describes the iterative process used to develop a virtual coaching program for out-of-school-time (OST) educators, particularly those who work in afterschool and library settings. The program, called ACRES (Afterschool Coaching for Reflective Educators in STEM), used a design-based implementation research (DBIR) approach to consider issues related to scale-up. Afterschool and library settings are complex systems that include supports and barriers that require adaptation for implementation. Throughout the design process, program developers worked to identify the essential elements of the program that should be maintained across contexts, while attending to the diverse needs of individual OST settings. Survey and interview data were collected from the full range of stakeholders throughout the implementation process to verify the importance of the essential elements to the professional learning model, and to gather early indicators of the program’s potential related to three key concepts for successful scale-up of programs: sustainability, spread, and shift. Conclusions are shared in relation to how these types of results support the scale-up of programs, and the strengths and gaps in the process used to apply the DBIR approach in our work.

Introduction

After a successful initial implementation period, one of the primary goals of innovative educational programs is to scale up, or to be implemented across a number of diverse educational contexts. The motivation for scaling up is the hope that sharing the innovation widely will improve teaching and student learning throughout a system (Fullan, 2009; Peurach and Glazer, 2012). However, this is often a challenging feat for new educational programs (Levin, 2013; DeWire et al., 2017), especially considering the dynamic, complex needs of each unique educational setting within the system. This can be especially true for OST programs that often have more variability across setting and less consistency in youth attendance when compared to K–12 classrooms.

While some define scaling up simply as “more” (i.e., implementation in more schools or programs, with more teachers and more students), others recognize the multifaceted nature of scaling up (Coburn, 2003; Dede et al., 2007). Coburn states that the process is complex, and includes four interrelated elements: depth (changes in beliefs, norms, and pedagogy), sustainability (change that is maintained over a substantial period of time and is supported at multiple levels), spread (dissemination both within and across organizations, which in turn influences policy and decision-making), and shift in reform ownership (ownership is assumed by users and is adapted as necessary to fit the unique needs of the organization).

One research method that is particularly well-suited to help innovative educational programs achieve scale is design-based implementation research (DBIR) (Penuel and Fishman, 2012; Penuel et al., 2011; Fishman et al., 2013; Svihla, 2014). The process of DBIR allows researchers to work in collaboration with multiple stakeholders to improve and appropriately adapt educational programs as they scale across diverse educational settings. The four core principles of DBIR are: 1) a focus on solving practical problems, as determined by multiple stakeholders; 2) a collaborative, iterative design process in which stakeholders are consulted and provide valuable input; 3) the goal of creating knowledge to be used in various learning contexts, which can also serve to improve design; and 4) a focus on increasing capacity to help educational innovations spread throughout an entire system or organization. Working in conjunction with one another, the four elements of DBIR allow researchers to both develop innovations and evaluate and refine innovations such that they are positioned to scale (Penuel and Fishman, 2012; Cobb et al., 2013).

In this case study, we describe the development of, and early implementation research on a virtual professional development program for OST educators called ACRES (Afterschool Coaching for Reflective Educators in STEM). We share data that were gathered iteratively to improve the ACRES program in collaboration with multiple stakeholders. We also demonstrate how, using DBIR, ACRES is poised to scale up based on the dimensions of sustainability, spread, and shift. This study is unusual in that DBIR was employed to iteratively revise and improve a professional development program designed to support OST educators in informal learning environments. Historically, DBIR has been used to refine educational programs implemented in traditional school settings. At the time of this writing, the authors could identify only two studies to date that have used DBIR to make enhancements to informal learning programs (Patchen et al., 2017; Subramaniam et al., 2021).

The Need for Virtual Professional Development for Out-of-School-time Educators

In the United States, community professionals such as afterschool providers and librarians are increasingly being asked to provide youth in their communities with hands-on STEM learning experiences. A recent study found that STEM activities were offered at over 70% of all programs (Afterschool Alliance, 2020). In libraries the growth has been more recent but dramatic: in 2016, 55% of libraries reported offering STEM programming at least monthly (Hakala et al., 2016), while in 2019 that percentage had risen to 70% (Shtivelband et al., 2019). At the same time, research suggests that the majority of OST educators do not have strong backgrounds in STEM (Chi et al., 2008), leading to repeated calls for professional learning opportunities (e.g., National Research Council, 2015; Rosa, 2018). A recent study in 11 states showed that participation in STEM-focused afterschool programs leads to increases in youth STEM interest, identity, career knowledge, and 21st-century skills such as critical thinking. Even more importantly, these gains were higher in youth who participated in higher-quality programs, as assessed using the Dimensions of Success (DoS) observation tool, which includes key facilitation practices such as encouraging youth to engage in STEM inquiry and to explain their new understandings (Allen et al., 2017).

Persistent Problems of Practice

In this DBIR work we focus on two problems of practice that are frequently faced by OST educators in relation to their growing roles as STEM educators: 1) Despite the demands on them to offer high-quality STEM programming, they are in systems that rarely promote investments in their professional learning to support this goal. STEM activities tend to be “hands-on” without being “minds-on,” and there is seldom a culture of reflection on STEM education practice to encourage the deeper learning characteristics of high-quality STEM programs (Allen et al., 2017); 2) These community educators often experience professional isolation, especially in rural areas. Clearly there is a need for high-quality, accessible professional development in a socially supportive context. The use of group coaching models, preferably conducted virtually, seem particularly promising in addressing this need (Denton and Hasbrouck, 2009; Brasili and Allen, 2019).

The Program’s Theoretical Framework

The underlying theoretical framework for ACRES draws from research and practice in three subdomains: instructional coaching, professional learning communities, and contemporary digital technologies. Each was explored in action during the pilot years of the program.

Instructional coaching is a relatively common strategy in the world of school-based teacher professional development (Denton and Hasbrouck, 2009). In this approach, a skilled leader helps teachers learn and apply new teaching strategies in their own work, in an atmosphere of collaboration and reflection. While much still remains unstudied in this area (Blazar and Kraft, 2015), some have shown its power to improve teacher practices and student achievement (Sailors and Price, 2010; Allen et al., 2011; Campbell and Malkus, 2011). One finding is a strong correlation between the amount of time the teacher and coach spend together and improvements in practice (Anderson et al., 2014; Blazar and Kraft, 2015). From this literature, the project team determined that the course would explicitly focus on a small number of STEM facilitation skills. Additionally, the program is based on the well-established principle that learning skills takes time and practice, making it quite different from single professional development workshops (e.g., Garet et al., 2001).

A second major development in the world of school-based teacher professional development is the use of professional learning communities (PLCs) in school districts across the country (e.g., Sims and Penny, 2015; Spencer, 2016). Essentially, a PLC involves a group of educators coming together with a common set of goals to reflect on and improve their teaching practices (Blankenship and Ruona, 2007; Britton et al., 2010). Research has shown the power of PLCs to change teacher practices, such as paying more attention to students’ reasoning, and using diverse modes of engaging students (Britton, 2010; Owen, 2015; Gee and Whaley, 2016), skills that would translate extremely well to the OST world. While PLC’s take a variety of forms, research by Nelson (2009) has shown that key elements for success include: teachers taking a learning stance in their work together, a nurturing and supportive environment, and targeted support in the topics of greatest challenge. The project team applied this literature to the general format of the program to create instructional PLCs, which included an ongoing series of meetings with peers, focused on creating a supportive culture of reflective practice. Additionally, the program encourages an explicit focus on educators engaging together dialogically as learners and integrates principles of focusing on what students are thinking and learning.

The third component of the model is the use of inexpensive digital recording and communications technologies to make the instructional PLCs work for blended or fully online groups of educators, without the need to purchase additional hardware. Video recordings of educators’ interactions with youth are shared privately with peers during the instructional PLC, and effectively simulate a live coaching scenario (Sherin and Han, 2004; Gaudin and Chalies, 2015; Cook et al., 2021). Improved video conferencing platforms such as Zoom and Google Hangout, now ubiquitous, allow for an online experience that can be made highly social and interactive (Brasili and Allen, 2019; Peterman et al., 2020).

When the first pilot version of the project began in 2014, these tools were used rarely for OST professional development. Now, as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, they are used more frequently. Even so, while online learning has been championed largely by universities (including the use of MOOCs, webinars, and asynchronous approaches), and PLCs or instructional coaching are increasingly being used in school districts, this particular combination was unique in OST professional development when the program was initiated. It still serves as one of only a few examples in the literature today.

Study Context and Early Iterations

Over time, the project was refined to include a series of professional learning sessions in which three to 10 educators meet synchronously online every two to six weeks with a coach to learn and practice STEM facilitation skills for leading OST programs with youth. Over the course of three sessions, a coach teaches and models skills in the context of a hands-on activity, and participants watch sample videos of other educators using the skills. They then bring videos of their own work with youth to share with their cohort, and practice sharing constructive feedback by discussing strengths and opportunities for growth in each video.

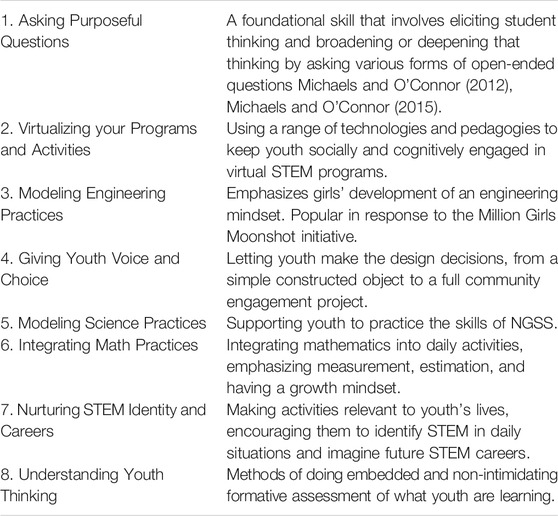

The program consists of eight modules, each of which targets a STEM facilitation skill (see Table 1 for a full list and descriptions of each).

The DBIR approach (Fishman et al., 2013) was used to develop the program, and provided insight into how the innovation works under a wide range of OST settings. Multiple OST stakeholder groups came together, for example, to inform the design and delivery of the program in response to persistent problems related to the need for professional learning in highly effective STEM pedagogies, especially across distance. Stakeholders included staff from the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance, with expertise in design of professional learning experiences in STEM; leaders from the National Afterschool Association, and from state and national library associations, with STEM interests and deep experience in professional learning for their members; educational researchers specializing in OST teaching and learning; and both leaders and practitioners from a wide range of afterschool and OST settings. They met in various configurations; most common were weekly meetings among the five MMSA coaches to share experiences and suggest improvements to the model, large-group advisory meetings held approximately three times a year, and myriad one-on-one conversations between MMSA staff and specific professional groups (e.g., Vermont Afterschool Association, Maine Afterschool Network, and New York State 4-H Youth Development) during preparatory customization of the program to meet the needs of their particular professional group. Ongoing data collection was also used to support iterative decision making.

As noted earlier, DBIR focuses on improving learning environments for students, building capacity for educators to enact innovations, supporting systems-level improvements by focusing on both the design of tools and practices, and designing supports for using those tools and practices in real-world settings. In the context of this case study, the program was developed to build the capacity of OST educators to facilitate STEM activities with youth, thereby improving the learning environment for students. By building OST educators’ facilitation skills and confidence, the program provides tools to offer youth hands-on, minds-on learning experiences that nurture STEM relevance and identity, and deepen reflection and understanding, while engaging in authentic STEM practices (Cook et al., 2021).

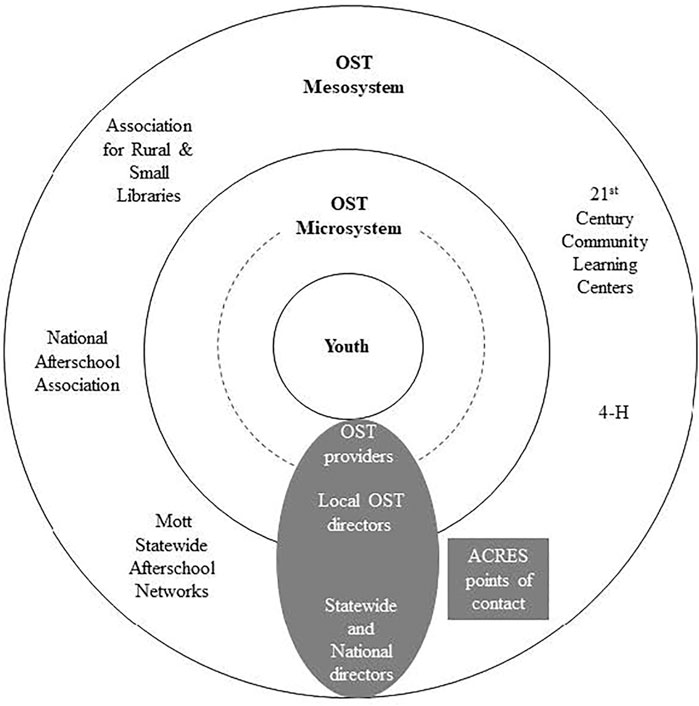

Figure 1 presents the OST learning ecosystem in which the program operates and includes examples of the key stakeholders with whom the program has direct interaction in gray. These include OST educators who work directly with youth and local OST directors, both of whom are in the microsystem, as well as national offices and support networks in the mesosystem. Two levels of stakeholders are represented in the microsystem, with OST educators who are positioned closer to youth and OST directors who are positioned closer to the mesosystem.

FIGURE 1. Adaptation of Bronfenbrenner's ecosystem model to show the OST contexts where ACRES has been implemented, and the levels at which ACRES interacts directly with stakeholders in the OST system.

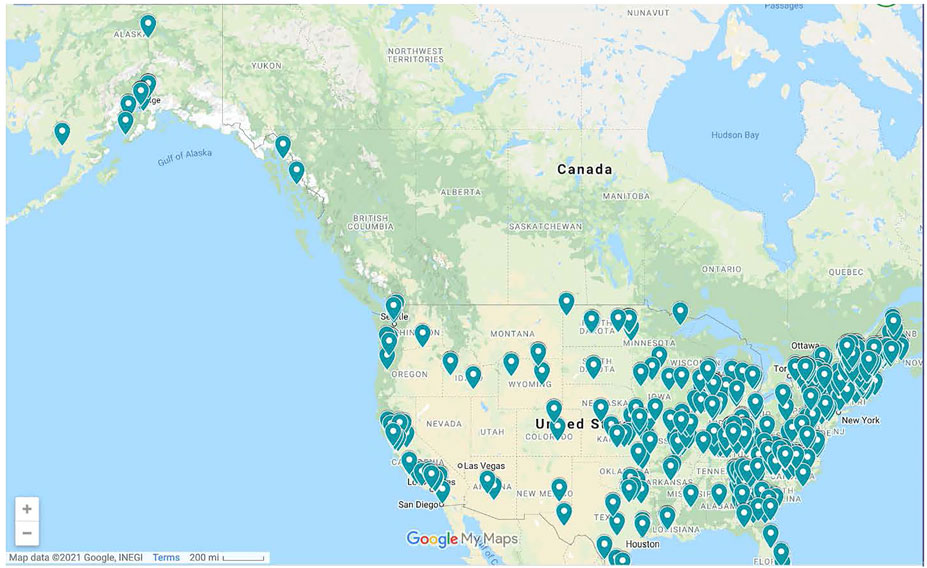

The specific groups presented in the mesosystem of Figure 1 include those who participated in the program from 2017 to 2020, including a total of 816 educators. Figure 2 shows the geographic reach of ACRES programming to date. The program has reached educators in 44 states, with the most concentrated reach in the Eastern U.S. Many educators signed up and participated as individuals, but some knew each other as a result of being actively recruited by a common contact such as a supervisor.

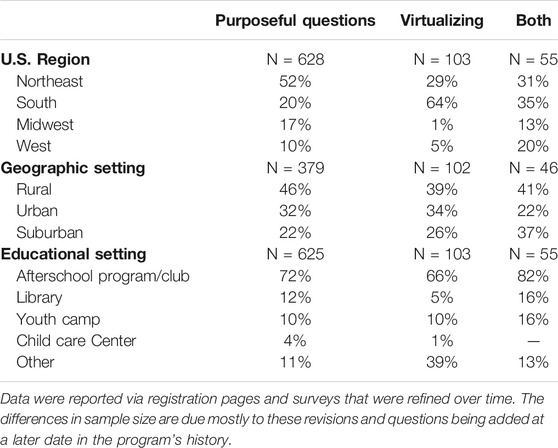

The majority of educators represented in Figure 2 participated in Asking Purposeful Questions and Virtualizing Your Programs and Activities, the two modules featured in this paper; a total of 802 educators have completed one or both of these modules to date (98%). ACRES educators are described in more detail in Table 2. Regarding geographical setting, the largest demographic was from rural areas which has been a particular focus for the program. Most educators work with youth in afterschool programs or club settings, while smaller numbers engaged with youth through libraries, summer camps or other informal learning environments.

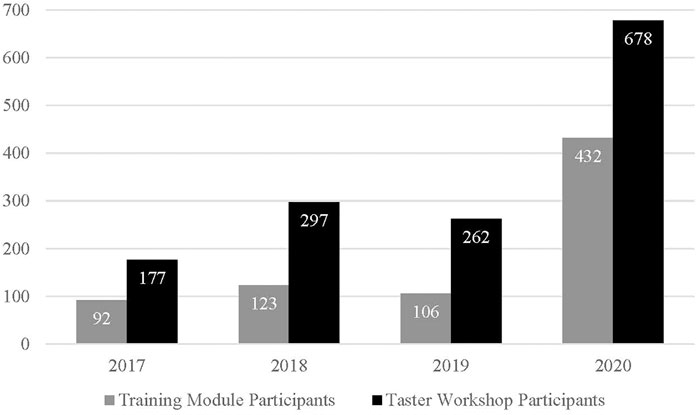

The spread of the program was also aided by the frequent offering of “Taster Workshops,” 45–1.5°h-long during which interested educators were given a short experience with the program’s materials and pedagogical approach. These reached a total of 1,414 over the same period (see Figure 3 for a comparison). The Taster Workshops were particularly helpful as a strategy for showing that the course was enjoyable and social, and for beginning to build early relationships between educators and coaches.

The program was developed with a focus on scale and sustainability from the beginning. It was unique in that professional learning was offered to the full range of OST systems concurrently, rather than working within one OST system (such as statewide afterschool networks) and then expanding to another (such as 4H). Project recruiters attempted to initiate extended relationships with OST organizations from the beginning and created supportive pathways for educators to become coaches within their own organizations. The team also considered processes that would support the program’s implementation within the context of each OST system, such that an entire network or region might implement, scale, and sustain the innovation. As with all DBIR projects, key questions of interest included What works for whom and under what conditions? and How can we make this innovation work under a wide range of conditions? (Penuel et al., 2011; Fishman et al., 2013). With these questions in mind, the program and research and evaluation efforts were devised to understand design and implementation supports and constraints across the OST settings involved, in order to build understanding about virtual professional development for the field.

Methods

The data for this case study were collected over a two-year iterative development period. Some data were collected consistently over time. Other data were gathered on one occasion and in response to specific design questions relevant to the current stage of the program’s development. Analyses were conducted regularly as data were collected so that they could be used as part of the DBIR process. Results are presented here in aggregate, and from professional audiences from the range of OST stakeholder groups included in gray in Figure 1.

Participants

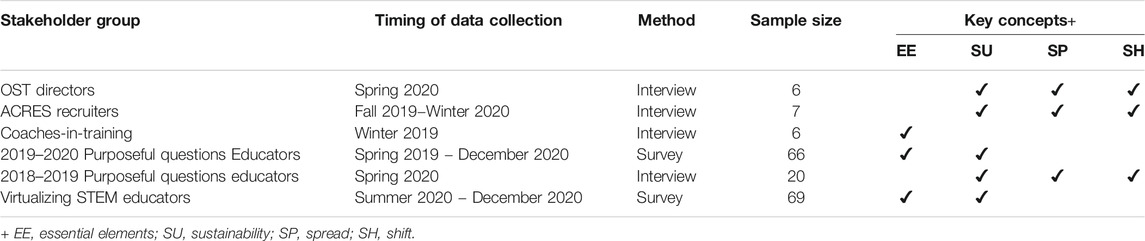

A full range of project stakeholders contributed data to support the iterative development of the program across a two-year implementation period. Table 3 presents a summary of participants, methods, and timing of data collection by stakeholder group. Qualitative data were collected from both program recruiters and OST program directors. Program recruiters are the people tasked with establishing new cohorts of educators to participate in the program. Four interviews were conducted in fall 2019 to gather stories about recruitment successes and challenges in afterschool settings. A second round of five interviews was conducted in early 2020, with a specific focus on those who had recruited and worked with library cohorts.

In spring 2020, interview data were collected from the six statewide OST directors who had begun to embrace the program; this number represented the majority of statewide afterschool networks that had participated in the program at that time. These directors were chosen in collaboration with the program staff to represent those who showed significant interest in the program, and various degrees and timeframes of participation.

Qualitative data were also collected from coaches-in-training. All coaches who participated in a train-the-trainer program in fall 2018 were invited to participate in an interview to share their feedback about the program’s essential elements in winter 2019; six of 10 participated in the interview (60%).

Quantitative survey data for this study were collected from two groups of OST educators. The first included those who completed a post-program survey after completing the Purposeful Questions module between spring 2019 to the end of 2020; a total of 66 educators completed the survey during that time (referred to hereafter as the Purposeful Questions educators). The second included those who completed a post-program survey after participating in the Virtualizing STEM module (n = 54, referred to hereafter as the Virtualizing educators).

Finally, longer-term qualitative data have also been collected from those in the Purposeful Questions cohorts. All educators who had completed the module between spring 2018 and fall 2019 were invited to participate in a follow-up interview in spring 2020 (n = 59). Of these, 20 responded and were interviewed (34%).

Instruments and Procedures

Four interview protocols, one for each stakeholder group, were used to collect data for this study. All interviews were transcribed for the purposes of analysis. Interviews with recruiters, directors, and coaches-in-training were coded for common themes across the entirety of the interview transcript. The interview protocol for program recruiters consisted of 18 questions designed to identify themes related to the systemic supports and barriers to joining and completing the program. The protocol for OST directors included a minimum of 20 questions. A subset of items included a series of “anything else” prompts that were used to ensure the capture of comprehensive details regarding the systemic barriers and supports for integrating programs into their educational context, and adaptations that were made to the program for implementation purposes. The interview protocol for coaches-in-training included 28 questions; responses were coded to capture impressions of the importance of essential elements of the program.

Follow-up interviews with Purposeful Question educators were coded on a question-by-question basis. Many responses were coded dichotomously, e.g., to characterize the particular configuration of components experienced by participants. A subset of responses were coded thematically, using consensus coding that was conducted by two members of the research team. For the purposes of the current study, responses to 11 items were used to document the systemic supports and barriers to using the program, educators’ use of the program’s facilitation skills with youth in STEM programs and beyond, the perceived impact of the program on youth, and ways that educators shared their experiences with others in their network.

Each of the quantitative assessments were administered as an online survey at the conclusion of the program. For the purposes of this study, responses to two questions asked of the Purposeful Questions educators were used. One question asked which of the ACRES components Purposeful Questions educators had implemented, and the other asked how likely educators would be to recommend the program to a colleague. Both questions were answered in a Likert-style rating. Similarly, responses from three questions asked of Virtualizing educators were used, all of which were rated on a Likert-style scale. Two of these questions focused on changes in the ways in which Virtualizing educators interact with youth, and the third asked how likely they were to recommend the program to colleagues or friends. All ratings data were scored low to high for the purposes of analysis.

Results

Essential Elements

DBIR derives from the intersection of several research traditions: evaluation research, community-based participatory research, design-based research, implementation research, and social design experiments (Fishman et al., 2013). It acknowledges the fact that programs are embedded in complex systems, and promotes study across multiple levels of a system as part of the design process. As one major part of their DBIR process, the project team utilized The Innovation Implementation Conceptual Framework (Century and Cassata, 2014) to identify and verify the essential elements of the model. Structural components, as defined by this framework, are the organizational, design, and support elements that serve as building blocks for an innovation. Other structural components are educative, in that they are designed to teach participants to know something or be able to do something. In addition to the structural components, the Innovation Implementation Conceptual Framework documents interactional components that explain the behaviors, interactions, and practices of an innovation during a program’s enactment.

As part of their DBIR process, the project team met regularly throughout 2017 and 2018 to discuss implementation successes and challenges, and to identify a list of feasible essential elements. As the result of these meetings, the structural components of the program’s virtual professional development model (labeled S1–S5 in what follows) were refined to include the following: online instructional PLCs that include a small group (ideally six) of OST educators (S1) who meet regularly with a coach (S2), who teaches and models skills in the context of a hands-on activity (S3). For a minimum of two sessions, the educators are encouraged to bring short videos of their own practice to share with their cohort (S4). The videos are expected to be less than 5 min in length and demonstrate practice using the facilitation skill. Cohort members then practice sharing constructive feedback by observing and discussing strengths and opportunities in each video (S5). Within this structure, the educative components include the information shared with practitioners to define each of the facilitation skills and the ways those skills should be used to lead youth-based OST programs (e.g., What is a purposeful question, and what are ways to integrate purposeful questions into OST activities?).

The program’s interactional components are the behaviors that coaches are expected to use when leading the instructional PLC to foster a positive and interactive learning context for OST educators. The instructional components are labeled I1-–I5 hereafter. Specifically, coaches establish group norms and shared goals for the cohort (I1). They reiterate that the project respects the privacy of participants by keeping all videos confidential, and by encouraging transparent sharing of honest feedback from multiple perspectives (I2). Coaches set high but achievable expectations for OST educators during each professional learning session by encouraging practitioners to set “stretch goals” that will help them move beyond their existing skill level and advocating for “safe and brave” space for sharing and receiving feedback (I3). They model skillful facilitation (e.g., asking mostly open-ended questions, modeling wait time; I4), and support technology learning by integrating opportunities into the instructional PLC sessions (I5).

Data were collected over time to document whether and how these structural and interactional elements were considered vital program components to those being trained. The first opportunity was a series of interviews with coaches-in-training that were conducted relatively early in the project team’s process to document essential elements. That work, and the interview responses from coaches-in-training, then informed a new set of survey items that were used to gather impressions from both Purposeful Questions and Virtualizing educators. Each group answered questions that were framed to represent essential elements within the context of the specific professional learning module being evaluated. Results are described below for each of these three groups. For the purpose of this analysis, the results reference the specific essential elements identified above (i.e., S1–S5, I1–I5). In reality, none of the essential elements function alone and many are dependent on the others for the program to be successful. Even so, attempting to disaggregate the essential elements to verify their role in the learning process, from the perspective of various stakeholders, proved a useful strategy for the DBIR process.

Coaches-in-Training

Coaches-in-training shared their impressions of the importance of each ACRES essential element based on their experiences with the train-the-trainer model. Most had not yet applied their professional learning to lead a cohort of their own. Coaches-in-training shared unique ways that their coach and their peers were important to learning how to be a coach, with 83% (n = 5) describing the specific roles that coaches played and 100% describing the influence of their peer group (n = 6). Regarding their coach, coaches-in-training shared general examples about how the coach modeled the program’ facilitation skills (S3, I4), as well as specific examples of support provided during the instructional PLC (I1, S4). They believed that the small cohort size (S1) allowed for relationship building over time (S2), overall discussion, and time to dive deeply together into the program materials. Coaches-in-training also reported that live meetings provided a positive and meaningful environment to engage in genuine interactions, while also nurturing fresh ideas. The quotes below reiterate the importance of modeling skills (S3, I4) and creating a safe and brave space (I3) for sharing openly (I2).

I think (our coach) and the rest of the ACRES team are really great about modeling the skills we’re trying to use. So they ask good purposeful questions and make sure that it’s up to us to reflect on our work and what we’re doing and set a welcoming and inclusive environment so it makes it easy for everybody to chime in.

I think in a small group you get to know people better. You get to have time to have discussions too. So you can go a little bit deeper sometimes than if it’s a larger group. And the comfort. You feel like a team.

Much of the learning that happens in the program occurs through sharing and receiving constructive feedback about videos that feature teaching practice. The video requirement is a primary way that the coach supports technology use (I5). Participants watch sample videos of one another as they use the program’s facilitation skills with youth, and then discuss the strengths and growth opportunities observed (S4, S5). Five coaches-in-training (83%) confirmed that having time to reflect on their own practice was a meaningful element of their train-the-trainer experience. Some stated that receiving immediate feedback from peers was meaningful to them, while others focused more on their own thinking and reflection. The quotes below reflect learning that occurred from watching their personal video in one instance (S4), and peer videos in another (S5). Both examples demonstrate coaches-in-training reflecting on ways to stretch their practice (I3).

It’s hard work to sort of unpack your habit. It’s definitely hard work to put yourself in the vulnerable position of watching yourself teach and seeing yourself sort of stumble through what you hope is going to be a quality experience.

Watching the others’ videos was very helpful because I could see, “Oh, that’s a great idea,” or, “Oh, I like the way they engaged the kids with that activity.” So I was able to take tips to help with me and with my teaching.

Coaches-in-training also highlighted the bond that is fostered by the instructional PLC, and the role those bonds play in the success of the model. The first quote below highlights many essential elements of the program, reiterating the importance of receiving live feedback in response to videos of teaching practice (S4) and then reflecting on how to apply that feedback (S5). The second demonstrates the importance of the bonds created through the program in contexts beyond, referencing the ways the cohort model provides the opportunity for broad support and collegiality. When asked to reflect on their learning during the train-the-trainer sessions, coaches-in-training shared:

When you’re investing at this level of personal contact, it’s such an enormous jump of your skill sets because you are viscerally involved in hearing live someone’s feedback to what you produced. And it forces you to sort of step back and say, “Okay, I heard these really nice things. But then here are these things that people picked out about my challenge and I’m feeling vulnerable but they’re being courageous to speak up and say it. And I have the same opportunity.”

I think those connections there are other people out there like me in other places that are trying to achieve these same kinds of things and that we can help each other out.

Educators

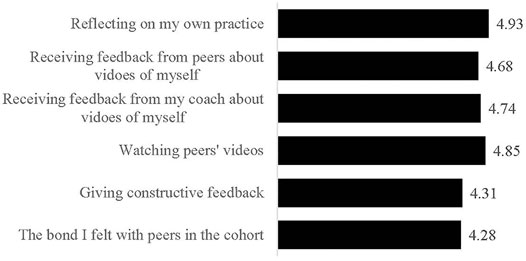

Purposeful Questions educators were asked to rate the impact of essential elements on their learning using a series of Likert-style questions. The essential elements were compartmentalized into roles played by coaches, peers, and the OST educators themselves. All essential elements received moderate, positive endorsement from OST educators, with average ratings at the upper middle range of the scale (see Figure 4 ). Experiences with their coach (I3), watching peers’ videos (S5), and reflections on their practice (I3) were the essential elements that OST educators believed affected their learning most, followed by receiving feedback from peers (S4). Giving feedback to others (S5) and the bond felt with the cohort (S1, S2) were also considered impactful, though slightly less so.

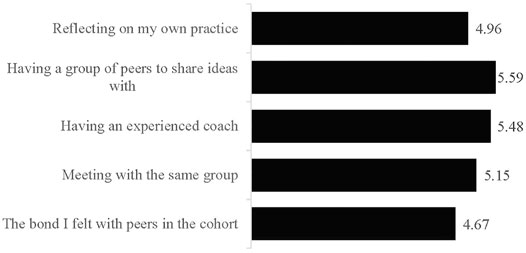

As with those described above, Virtualizing educators were also asked to rate the impact of the program’s structure and interactions on their learning. All essential elements were endorsed by Virtualizing educators, with average ratings at the upper end of the scale (see Figure 5). Three essential elements were rated using the top options on the scale, with average ratings between 5 and 6. These included the specific roles that the coach played during the instructional PLC (I4), and meeting with the same group over time (S2) to share ideas (I2). Ratings for the importance of reflection activities (I3) and the bonds formed with cohort members (S1, S2) were slightly lower, though these elements were also considered to have a high impact on learning.

Consistent Themes

Each of the structural elements were verified as important by the coaches-in-training, including small cohort size (S1), regular meetings (S2), modeling of skills by a coach (S3, I4), watching and receiving feedback on videos of their own teaching practice (S4, I5), and watching and providing constructive criticism of peers’ teaching practice (S5, I5). Though the sample size for the interviews was small, this cohort was convened at a key point in time, when the project team was narrowing its focus on essential elements, and thus provided a meaningful touchpoint for the team. The quotes from coaches-in-training and the essential element highlight the dynamic interplay between structural and interactive components in the program model. The use of videos (I5), for example, sets the stage for the learning that happens through essential elements S4 and S5.

The ratings items used with the Purposeful Questions and Virtualizing Educators attempted to disaggregate these interactions into specific components that spanned a subset of the structural and interactive components of the model. The ratings from both groups of educators verified the importance of these essential elements to learning, with the role of the peer group and coach receiving the highest ratings. Though we attempted to assign items to one or two essential elements for the purpose of this analysis, the integrated nature of the program’s delivery may mean that we have under-interpreted these data. The item receiving feedback from peers about videos of myself, for example, is likely the combination of several essential elements including the video requirement (I5), the learning environment created by the coach (I1, I2, I3), and the expectation that videos will provide a reflection point for the cohort (S4).

When considering these results as part of the team’s DBIR process, the team was encouraged after seeing the essential elements all receiving moderate to high ratings of value. In particular, the item “reflecting on my own practice” was rated very highly (almost five by both groups of educators), showing that the educators valued the foundational approach underlying this kind of PLC. The feedback from both educators and directors gave more emphasis than the team expected on building relationships to reduce isolation; as a result the materials were adjusted to give a greater emphasis to this process during the sessions and also during the recruitment. Also, the skill of giving feedback to peers was initially included as one of the educative essential elements, but when the stakeholders gave it less value than expected, the team removed this element from the list.

The iterative DBIR process also led to the development of supports and adaptations based on the needs and desires of particular participants. For example, librarians tended to have far less experience in STEM activities than afterschool educators, so cohorts of mostly librarians were given a more gradual introduction to the ideas of video-recording their own work with youth, starting instead with a video that simply showed the space in which they worked, as a form of skill-building ice-breaker. Also, the early versions of the materials included particular hands-on activities designed to serve as contexts for the educators to practice their skills, but this was changed when the coaches reported that educators tended to fixate on the activity rather than the skill; later versions had the activities reduced to being optional and educators were instead encouraged to apply the target skill in the context of their own curricular materials. This change emphasized practicing the skill, rather than the tendency to practice the activity. Another element that was allowed to vary was whether the group included senior members of the organization itself, or whether it included only staff members with direct contact with youth. Other adaptable elements included logistical characteristics such as time of day for the sessions, and the number of weeks between sessions (few enough to provide continuity, but long enough for the educators to record their work with youth and update their videos). Such adaptations allowed the program to maximize flexibility and support while still adhering to the essential elements described above.

Expectations for Sustainability, Spread, and Shift

Using the DBIR process provided the context for the leadership team to consider whether and how the program’s essential elements help foster initial interest and commitment from OST educators and systems, and the ways in which essential elements set the stage for program sustainability, spread, and shift. Characteristics of OST organizations and educators were also used to consider the systemic factors that affected adoption and continued engagement with the program (Century and Cassata, 2014). Here, we present data from across stakeholder groups that highlights the programmatic aspects of the program that set expectations for sustainability, spread, and shift.

Recruiters

Recall that five recruiters were interviewed on two occasions to share their perspectives about those who did and did not pursue the program. Four recruiters (80%) shared examples of conversations with educators and directors related to decreasing isolation across multiple levels of the OST system. Examples within the microsystem shown in Figure 1 included educators who felt isolated from one another and directors who felt isolated from their educators. Other examples were at the mesosystem level and included state-level coordinators who felt isolated from national-level systems and funders.

Expecting change in disconnected parts of the OST system assumes sustainability of the personal and professional connections made through the program; having a community of colleagues and making connections to other organizations have each been found to support sustainability (Coburn, 2003). The program featured in this case study was designed to fill a gap in many OST systems, by responding to the fact that many educators work in isolated contexts and thus have a need and interest in connecting with others. Framed within the context of the Innovation Implementation Conceptual Framework, the program was designed to respond to isolation as both a characteristic of individual educators and OST organizations (Century and Cassata, 2014). Expectations for combatting this isolation may be particularly salient to those who were recruiting and working with educators from within the same OST system, as exemplified below.

The accidental impacts can be the most powerful ones and I do highlight those a lot...So I try to talk about people coming together to learn, and to be connected, and stay connected after the learning experience. So I guess when I tell the ACRES story, I say it’s STEM facilitation and I also try to mention it’s (going to) make your everyday practice better, build that community with people across the state doing the same work as you.

Coburn (2003) says that, in order for a program to be sustainable, program developers must support a variety of users by allowing minor modifications that do not undercut the core principles of the program, while evolving toward conditions for success. In addition, providing support across multiple levels of a system also supports sustainability. These characteristics are exemplified in the recruiting practices used by the program. Though a defining feature of the program is virtual coaching, recruiters found that some OST systems were more comfortable with a hybrid model that included an introductory session in-person and then virtual professional learning thereafter. The Taster Workshops mentioned earlier function as a successful way to bridge this gap virtually; both directors and educators have been introduced to the program through this mechanism and then gone on to foster and participate in the full instructional PLC.

Recruiters have noted that successful recruitment into the program often required building trust across two types of stakeholders. The first was the decision-maker, often a director, who agreed to offer the program as a professional development opportunity to their staff. The second group was the OST educators themselves. The story below exemplifies both a hybrid approach and the minor modifications made to the program’s recruitment and delivery to ensure success. As is often the case, the program recruiter was also the coach for this cohort, ensuring that the initial trust- and relationship-building in the recruitment phase also carried over directly to the instructional PLC.

For the National Afterschool Association conference I did (an in-person) session on how to reach out to rural educators. A brand-new [statewide] afterschool STEM facilitator stayed afterward and she said, “This is absolutely perfect. This is what I need to help reach out to (my state). Can we work on this? What do we do?” So, (we) talked from March to July, once a month she had me apply to come out to the (state) AfterSchool Conference. I was going to do an in-person session and then we were going to do two actual coaching sessions. What she told me the day of was that everyone was very nervous, that they weren’t really sure what they were getting into, and that they were likely not to come if this was the start. I said, “Well, how about we just have it be the intro, just come and learn about it and we can have this group start afterward?” So, I spent that time answering their questions, getting them excited. We did start a cohort. They all showed up.

Spread is defined as dissemination both within and across organizations, which in turn influences policy and decision-making. Spread is another key concept necessary for programs to scale up. Within the context of program recruitment, spread typically occurs through an expanding network of those who have been part of prior cohorts. In later years of the project, the program has also relied on the video testimonials from past participants. This strategy prompted implementation of the program innovation by demonstrating what is possible from the perspective of others who share the same OST context. The potential for spread is also exemplified through the following series of connections, which the recruiter referred to as “relays.”

I think I always have to build the relationship with the first person that I’m connecting to. Because if it’s a relay I want to honor that person. (I have one alum) who just happens to have the gift of gab, and gets everybody loving him, and he’s memorable. And then he has been relaying people to me (Working with librarians in one state) really happened first that way...He introduced (me to someone in a new state). (That person) was able to pull together a cohort of five, including herself...I feel like in some ways she came out of her Purposeful Questions cohort realizing this benefit and that she couldn’t do it all. So that’s when she relayed me to the state person...the top leadership position as a state librarian (and) she knew the mechanism to reach more librarians.

Directors

While the examples above demonstrate the potential for sustainability and spread at the mesosystem level, the data from OST network directors demonstrate the features of the program that support these concepts at the microsystem level. For example, directors mentioned various aspects of the learning environment that make it easy for OST educators to participate in the program, and to implement it with youth—both of which allow for program sustainability. The flexibility of the program, which teaches skills that can be immediately applied in a variety of OST settings (n = 4, 67%), and the flexible nature of OST environments (n = 3, 50%) set the stage for the program to be sustained. Indeed, the immediate application of the program is embedded in the essential elements, which encourage OST educators to not only use the program’s facilitation strategies, but to video record their practice and bring it back to the group to promote additional learning and reflection (S4, S5). Directors’ reflections about the immediate potential for applying the program’s facilitation strategies across learning activities included the following:

The thing that I think is important to say is that of course afterschool programs really require flexibility. They also sometimes really benefit from proposals and models, so you could say, “It could be used this way. It could be used that way, whatever works best for you” But hearing that and having them say, “Okay, I’m not having to invent a whole new way of being. Instead, I’m going to find a way to make this work in scaffold or whatever.” That’s useful.

There’s flexibility (in out of school programs), and especially on the level of they’re already working with a STEM enrichment program, it really is a lot easier, I think, to layer (ACRES) into their practice.

Other aspects that support sustainability are the virtual aspect of the instructional PLC, which eliminates travel time and expense (n = 5, 83%), and the fact that the program is offered at no cost (n = 2, 33%).

(I saw) an opportunity with ACRES to actually expand our toolbox and work with people virtually, which was a big part of what we were looking for in particular, that would be a huge help to us to reach the state. Most of our state is rural. There’s lots of people who want professional development and we can’t offer it to them because we can’t get there.

Network directors are key to ensuring that information about new professional development programs is communicated to educators and administrators, thus promoting spread to both the OST meso- and microsystems. Most network directors met a leadership team member and learned about the program at an annual national conference or meeting (n = 5, 83%), events that help to maintain the community through which the program spreads. For various reasons, all directors (n = 6, 100%) were excited to share information about the program with their network organizations.

(This program is) quite attractive and brilliant to think of helping improve your practice by really looking at your practice, and having it be virtual in an age when it wasn’t as easy to do as it is right now and today.

It was the first time I’d heard about a resource like this and then met someone who I knew would understand the role of my group.

Spread can be easier when there are many OST organizations concentrated in a particular area, such as in urban settings, and more difficult to achieve in areas where there are few OST organizations, and where educators often feel isolated. Because it is a virtual program, educators serving in rural areas can participate as easily as educators in urban settings. Spreading to less populous regions is one of the components that network directors found attractive (n = 2, 33%).

Most of our state is rural. There’s lots of people who want professional development and we can’t offer it to them because we can’t get there.

It fit well inside of our equity lens, as opposed to having in-person trainings that really force folks from rural communities or smaller communities to not be able to participate.

Shift, a third concept that is necessary to achieve scale, takes place when ownership is assumed by users and is adapted as necessary to fit the unique needs of the organization (Coburn, 2003). While STEM programming can feel intimidating for some OST staff, and staff often want to be taught an activity that they can turn around and immediately teach to youth, the focus is on the facilitation of STEM activities. Network directors noted that this essential element (S3) fostered a shift in focus that helped educators become comfortable and confident delivering both STEM and non-STEM programming to youth (n = 5, 83%), thus also creating a change in how educators interacted with youth.

ACRES wasn’t teaching them, “I can do National Youth Science Day and talk about coding.” That’s not what it’s about. It’s like, I have a coding project or I want to do a coding activity with my volunteers or teach my volunteers, and I don’t need to know how to code. I just need to know how to facilitate.

I think a lot of staff are looking for actual activities. “Give me an activity, so I can take it back and use it,” which is not what ACRES is about. I think it’s more of a mindset that hopefully they walk away with.

Directors shared that another type of change occurred for Purposeful Questions educators. They stated that educators were initially hesitant to participate in a virtual professional development program (n = 5, 83%), because they were either uncomfortable with the technology or because they were concerned about the effectiveness of online professional development. Directors also noted that educators quickly overcame their hesitancy and learned to interact online in a productive and constructive manner, reiterating the success of essential element I5. This new comfort became particularly useful with the onset of the pandemic, as OST educators were forced to shift to virtual models for engaging youth (and not just for their own professional development).

We got comfortable using virtual tools to do hands-on STEM with people and with STEM itself at the same time.

I think this idea of being online and receiving coaching and feedback and training via Zoom or other platforms. I think folks are really comfortable with it now, so I think that’s going to be a real plus.

Educator Evidence of Sustainability, Spread, and Shift

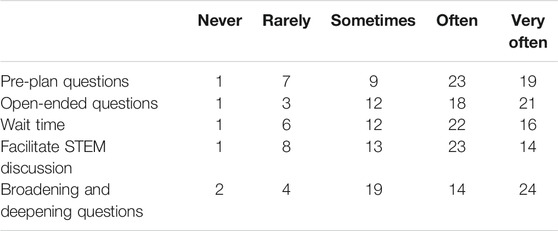

Though a young and growing program, evaluation results do offer early evidence of sustainability. Overwhelmingly, educators have applied the program’s facilitation strategies to their work with youth, both in the short and long term. Just after completing the Purposeful Questions module, for example, educators were asked how often they implemented five specific facilitation strategies with youth (see Table 4 ). A total of 98% reported that they had implemented at least one strategy. On average, educators reported that they used one or more of these strategies between sometimes and often (n = 55–63 across five items, mean = 2.86).

Similarly, Virtualizing educators reported immediate changes in the ways in which they engage with youth. All Virtualizing educators (n = 93, 100%) reported that their participation would impact the youth that they work with. The majority also noted that they had already tried new activities with youth by the end of the program (n = 62, 73%), or shared specific plans for how they will use what they learned with youth (an additional n = 6, 8%).

Months after their professional learning experience, Purposeful Questions educators shared ways that they had sustained their use of program facilitation practices. Most noted changes to how and when they asked questions of their students (n = 15, 79%), the use of open-ended questions (n = 6, 32%), the time they waited to allow students to answer (n = 4, 21%), and the ways in which they posed follow-up questions to students (n = 3, 16%). These longer-term teaching practices are particularly important given that youth outcomes are stronger when they experience high-quality programs that include these kinds of facilitation practices (Allen et al., 2017).

Letting there be unanswered questions and letting kids come up with questions. And I feel like even outside of STEM, it’s been really great to see in everyday life kids doing that work of questioning and wondering, and me not giving them the answer right away.

We did a bridge building program. And I remember asking, “Well, why do you think this type of bridge works?“ (for) an existing bridge, Golden Gate Bridge. And then when they were building their own bridge things didn’t work. I remember asking them, “Well, why is it not? What made you think of that idea? Why did you think it would work? Why do you think it didn’t work?” And I think before ACRES, I might have just been like, “Why didn’t it work?” I think I would stop there.

I learned that it’s very culturally appropriate to, if you’re going to ask a question, to give that long space for both youth and adults to answer. And that was something I was not great at, and I’m still improving upon. But was really a valuable part of ACRES.

Purposeful Questions educators who participated in the longer-term follow-up interviews also reflected on the aspects of the program that supported its sustainability in their practice, as well as perspectives related to spread and shift of their teaching practice over time. The informal nature of OST settings, such as afterschool programs and libraries, marries well with the program’s flexibility. Purposeful Questions educators believed that having the freedom to utilize the program’s facilitation skills broadly—both for STEM activities and non-STEM activities (n = 17, 94%)—and the flexible nature of OST settings were two of the main reasons they were able to easily adapt, implement, and sustain their use of program pedagogy (n = 6, 33%). As noted above, the deliberate focus on facilitation skills that can be applied broadly (S3), rather than specific STEM activities, also helps support sustainability and spread.

The afterschool setting definitely helps with ACRES because I felt like I was able to apply the purposeful questions. And if I needed to pivot or kind of change my lesson direction, I had the freedom to do so.

I feel like it’s useful in any area...it’s education related—it’s not just STEM.

In order to sustain change, educators must have support at multiple levels, including a community of colleagues (Coburn, 2003). Fifteen of the Purposeful Questions educators from the follow-up interview stated that they knew none or few people in their cohort before beginning the program (88%). This gave them the opportunity to make connections with educators from other OST organizations, and further expand their community of colleagues. Several essential elements of the program (S5, I2, I3) were designed to help foster these connections. Purposeful Questions educators noted that the cohort aspect of the program was unique (n = 7, 41%), indicating that they had not had the opportunity to participate in other professional learning communities. Some also shared that they had sustained relationships that were formed during the instructional PLC (n = 4, 21%), providing a long-lasting community of colleagues.

I remember that I really liked having other people to talk to about it. Like when we were in the online sessions, there were, I think three or four other people to talk to who were also professionals who were taking the same course. So, whereas a lot of professional development, I feel like you’re doing alone when you’re online. Instead, it was still that group setting. So I really liked that.

We did talk a lot about (the program) while we were doing it, and even we’ve referenced it after when we were working on different curricula.

Both the short-term survey results and the longer-term interviews provided evidence that educators were fostering the spread of the program. Just after completing the module, both Purposeful Questions and Virtualizing educators reported being very likely to recommend the program to a friend or colleague (n = 131, mean = 8.85 out of 10 and n = 95, mean = 9.09 out of 10, respectively). During the follow-up interview, 11 Purposeful Questions educators confirmed that they had spread the word about the program by recommending it to a colleague (74%) and sharing stories of their positive experiences (58%).

I talked to the use services person and kind of to everyone who was working with me at the time, I was very excited about it, and really thought it was something that would benefit librarians in general.

(I) was sort of telling people I think this would be useful for you because it would give you more of a structure for planning your programs and evaluating them and really helping kids to build better problem-solving skills and the things that are at the heart of STEM.

Recall that the concept of shift takes place when ownership is assumed by users and is adapted as necessary to fit the unique needs of the organization (Coburn, 2003). As noted in the section above, Purposeful Questions educators overwhelmingly felt that they could apply the program’s facilitation skills broadly (n = 17, 94%). This same freedom also allows for a shift in internal decision making, a key component of scaling up.

It’s good for (STEM), but you can use it everywhere. So I think from that, I felt empowered to think about the same kinds of things for any sort of program I was doing.

We’re pretty free to do kind of whatever we want with the kids .we throw art and other things in, but I feel like all of that stuff is related too, you know? You can’t just use things that you learn just for STEM. I’m putting it and using it in other places as well. And when we do our planning, it definitely shows. We’re, you know, planning more time or being more thoughtful.

Discussion

This study provides an example of how DBIR can be applied to a moderate-sized OST project over the course of a few years to support both program development and to provide initial evidence of the potential for project scale-up. This study responds to a call for examples of research that incorporate considerations of implementation and sustainability early in a program’s development (Penuel and Fishman, 2012). A particular focus of this project was to address two persistent problems in the OST STEM sector: how afterschool and library educators can meet the demand for high-quality STEM programming for youth, and how they can engage in professional learning in a culture of social support and reflection rather than reactivity and isolation. To answer these questions, data were collected from multiple stakeholders, using both interviews and surveys, to narrow down and then continue to verify the importance of the program’s essential elements. Stakeholder feedback was collected from those who represented different levels of the OST system (e.g., recruiters, directors, educators) and based on multiple types of OST programs (e.g., 21st Century sites, 4H, Boys and Girls Clubs, libraries, and statewide afterschool networks). The team used the data to consider the extent to which the program functioned as expected across OST settings, and to improve the program’s design in an effort to increase the program’s spread throughout an entire system or organization. This process occurred over a three-year period, and through many iterations and conversations about whether specific essential elements were fundamental to the success of the program or simply characteristics that could be encouraged, but not required. While the focus on essential elements felt overly conceptual and academic at times, being able to verify the essential elements with educators was critically important to considerations related to scale-up, particularly as recruiters continue to negotiate the parameters of new courses with organizational leaders of larger groups.

Regular monitoring of the survey data throughout the implementation provided the project team with the opportunity for continued reflection about the essential elements in practice. The amount of data available and the consistent results related to the essential elements between spring 2019 and spring 2020 supported the team’s choices in how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Virtualizing STEM module itself serves as one example of sustainability for the program, as it demonstrated that the program had a robust design that enabled it to adapt to the changes caused by the pandemic. Importantly, the quality of the professional learning experience, as indicated by educator ratings, indicates that the program did not abandon the essential elements in the process (Dede et al., 2007). One essential element that had to be adjusted under the new pandemic constraints was S4, in which educators make videos of their own practice to share with their instructional PLC cohort. With the majority of such programs going virtual or shutting down, educators were encouraged to be creative: bringing recordings of their zoom sessions with youth, videos of themselves doing STEM activities with their own children, or even lesson plans for their future STEM activities. In this way, essential element S4 became “For a minimum of two sessions, the educators are encouraged to bring videos or other artifacts of their own practice to share with their cohort.”

This study also used the concepts of sustainability, spread, and shift to demonstrate how the project has considered its feasibility for implementation at scale. Sustainability may be the most important of these at this stage in the program’s development, as demonstrating the program’s ability to affect practice in the longer-term is vital if it is to scale-up. The results in this study demonstrate that the program’s design was effective at fostering use of the program’s pedagogical strategies in the short-term, with the majority of educators confirming that they applied specific strategies to their practice while completing the professional learning. Those who were interviewed over six months later also confirmed that they continued to use the program’s pedagogical strategies in their work with youth. The concept of shift was also demonstrated by these educators, many of whom had used the facilitation skills within the context of STEM activities, as expected, and with activities beyond STEM as well.

A number of design characteristics supported the sustainability, spread, and shift of the program. Focusing on facilitation skills that can transfer easily across OST activities is one such example. This feature of the program may be particularly useful in avoiding the replica trap—trying to create carbon copies of programs, without taking local context into account (Wiske and Perkins, 2005)—related to program scale-up. Directors also noted that the program model allowed for slight variation in its implementation, and that this flexibility was an important consideration for OST systems in particular. Another is that the program was designed to create professional learning communities, providing a cohort of colleagues who supported one another during, and in some cases long after, their instructional PLC experience. Many OST educators are isolated in their work. Both the cohort model and the virtual delivery helped to combat this isolation, while also providing the potential for spread and shift. OST directors, in particular, noted the importance of this combination in their decision to offer the program to their educators. The quotes from coaches-in-training and educators affirm the importance of learning and reflecting on their facilitation skills as part of a cohort. Finally, the recruiters took advantage of existing relationships with people in relatively stable organizational positions (e.g., using a “relay” model to recruit their target audience), thereby revealing and leveraging the importance of word-of-mouth recommendations in these populations.

The combined presentation of results related to sustainability, spread, and shift in this paper was made in an attempt to be conservative in framing our results. While each concept has a distinct definition, each construct is also related to and sometimes overlaps the others (Coburn, 2003). In addition, the data used in this study to provide evidence of these concepts were not collected via methods that were designed to measure these constructs specifically; rather, the project team and external evaluator were driven to assess impacts with multiple stakeholders and to iterate the program for effectiveness and adaptability. What was learned, even with modest investment in studies and over a relatively short time period, led to the project being positioned to respond to a pandemic while retaining the elements that had shown long-term impacts.

We have attempted to use the data in this study to demonstrate how DBIR approaches can benefit projects that do not have the ability to do a large-scale study. Even so, the sample size for this study is a limitation of the work. Interview data were collected on a “just in time” basis, depending on the needs of the project team. The data collected in each instance included most or all stakeholders who were available to share their perspectives at that time, and so in that way the sample was comprehensive. Even so, the number of stakeholders interviewed at each time point remained small. In the case of the coaches-in-training and the essential elements, the interview data were used to inform the development of survey items that were then used to collect data from a larger sample. This verification process helps alleviate possible concerns regarding sample size in relation to these topics.

The results presented in this study offer a snapshot in time that is part of an ongoing development process. The team continues to collect and use survey data to explore consistencies and differences in ratings based on group characteristics, and the extent to which educators participate fully in the program. Additional interviews are also planned with educators trained in 2020, to continue gathering evidence of sustainability. This study differs from other DBIR examples in the literature in that it does not include results from the youth who are the final beneficiaries of the program. Existing models, such as the scalability index for technology innovations, include student data as a key factor in determining a program’s readiness for scale (Clarke et al., 2006). By contrast, professional development programs for OST provide unique challenges in relation to this criterion, in that the youth who participate in OST are a notoriously transient group of participants when compared to students in classrooms, and there are no easy equivalents of grades or test scores in an environment designed to nurture emergent, interest-based STEM learning (Friedman, 2008; National Research Council, 2009). Existing scholarship has demonstrated that the kinds of skills fostered by the program improve teacher practices and student achievement (Sailors and Price, 2010; Allen et al., 2011; Campbell and Malkus, 2011). A next step in studying the program will be to attempt to replicate these kinds of results in OST settings.

Even without direct input from youth, we believe that this case study offers a solid example of how DBIR can be utilized to help support program development and to study the scale-up potential of OST programs. We also believe that some of the strategies used in this program can be adopted by others who wish to train educators to combat some of the systemic challenges of OST settings. The project team learned over time, for example, that the instructional PLC approach was of equal interest to library staff and afterschool providers, and that these educators worked well with mixed groups that included those from both OST settings. The program worked better when it was made modular, because a complete course of eight skills over many months was too difficult for most OST educators to commit to or schedule far in advance. Modularity also made it possible for educators to choose the content that was most relevant to their interests and needs.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Enacting online, instructional PLCs that focus on facilitation skills that can transfer across discipline holds particular promise for the field. This type of professional learning helps combat the isolation experienced by many OST educators and provides teaching practices that can be utilized across a wide range of OST activities to support youth development. Some of the modifications to the program over time, such as the primer ice-breaker activity that eases educators into virtual learning and the teaser sessions to demonstrate the program’s structure and establish initial levels of trust and comfort, are also strategies that might be applied by a broad range of professional development programs that are exploring online program delivery.

To date, research and evaluation efforts on the ACRES program have focused at the mesosystem and microsystem levels of the learning ecosystem. Targeting these levels is a direct match for the intervention itself, which is enacted with educators. As with many PD programs, data have been collected before and after the training. It is less common to gather follow-up data on perceived impacts, though the results in this paper share promising results. What is missing currently from this study, and from others in the field, is a detailed account of the supports and constraints that educators experience when enacting the program with youth, and the ways that local context interacts with those supports and constraints to create a range of learning environments. It is our hope the work we have shared here provides inspiration for others to join us as we continue to use the DBIR approach to explore the use of PLCs in OST.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

KP, JRE, and SA had primary writing responsibilities for the manuscript. KP and JR also had primary responsibility for collecting a subset of the data used for this study. SA is the principal investigator for this project and thus helped lead the DBIR process described. SB, BN, and KK had primary responsibility for collecting a subset of the data used for this study, and for contributing to how those data were used in the DBIR process.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1713134. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

Author KP was employed by the company KP Consulting, Co. Author JRE was employed by the company Virginia Tech.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Afterschool Alliance (2020). America after 3PM: Demand Grows, Opportunity Shrinks. Available at: http://afterschoolalliance.org/documents/AA3PM-2020/AA3PM-National-Report.pdf (Accessed February 25, 2020).

A. J. Friedman (Editor) (2008). Framework for Evaluating Impacts of Informal Science Education Projects. Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Allen, J. P., Pianta, R. C., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., and Lun, J. (2011). An Interaction-Based Approach to Enhancing Secondary School Instruction and Student Achievement. Science 333, 1034–1037. doi:10.1126/science.1207998

Allen, P. J., Noam, G. G., Little, T. D., Fukuda, E., Gorrall, B. K., and Waggenspack, B. A. (2017). Afterschool & STEM System Building Evaluation 2016. Belmont, MA: The PEAR Institute: Partnerships in Education and Resilience. doi:10.4324/9780203790359

Anderson, R., Feldman, S., and Minstrell, J. (2014). Understanding Relationship: Maximizing the Effects of Science Coaching. Edu. Pol. Anal. Arch. 22, 54–n54. doi:10.1108/oth-11-2013-0047 Retrieved from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1050386.pdf.

Blankenship, S., and Ruona, W. E. A. (2007). Professional Learning Communities and Communities of Practice: A Comparison of Models, Literature Review. Retrieved from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504776.pdf (Accessed February 23, 2020).

Blazar, D., and Kraft, M. A. (2015). Exploring Mechanisms of Effective Teacher Coaching. Educ. Eval. Pol. Anal. 37 (4), 542–566. doi:10.3102/0162373715579487

Brasili, A., and Allen, S. (2019). Beyond the Webinar: Dynamic STEM Professional Development for Online Learners. Afterschool Matters. Available at: https://www.niost.org/Afterschool-Matters-Spring-2019/beyond-the-webinar?fbclid=IwAR0jJoDlZi39pOQC8FYSTlohjCRLgYQ3-Oi1rWYFT-S-TB2ZsASVC0CKN08 (Accessed January 20, 2020).

Britton, T. (2010). National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, and WestEdSTEM Teachers in Professional Learning Communities: A Knowledge Synthesis. Retrieved from: https://www.wested.org/online_pubs/resource1097.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2020).

Campbell, P. F., and Malkus, N. N. (2011). The Impact of Elementary Mathematics Coaches on Student Achievement. Elem. Sch. J. 111 (3), 430–454. doi:10.1086/657654

Century, J., and Cassata, A. (2014). “Conceptual Foundations for Measuring the Implementation of Educational Innovations,” in Treatment Integrity: A Foundation for Evidence-Based Practice in Applied Psychology School Psychology Book Series. Editors L. M. Hagermoser Sanetti, and T. R. Kratochwill (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 8181–108108. doi:10.1037/14275-006

Chi, B., Freeman, J., and Lee, S. (2008). Science in Afterschool Market Research Study. Berkeley, CA: Lawrence Hall of Science, University of California.

Clarke, J., Dede, C., Ketelhut, D. J., and Nelson, B. (2006). A Design-Based Research Strategy to Promote Scalability for Educational Innovations. Educ. Tech. 46 (3), 27–36.

Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Smith, T., Sorum, M., and Henrick, E. (2013). Design Research with Educational Systems: Investigating and Supporting Improvements in the Quality of Mathematics Teaching and Learning at Scale. Natl. Soc. Study Edu. 112 (2), 320–349. doi:10.1007/s11858-015-0692-5

Coburn, C. E. (2003). Rethinking Scale: Moving beyond Numbers to Deep and Lasting Change. Educ. Res. 32 (6), 3–12. doi:10.3102/0013189x032006003

Cook, K., Lakin, H., Allen, S., Byrd, S., Nickerson, B., and Kastelein, K. (2021). Virtual Coaching PLCs in and Out of School. Connected Sci. Learn. 3, 1. Available at: https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning-january-february-2021/virtual-coaching-plcs-and-out-school.

Dede, C., Rockman, S., and Knox, A. (2007). Lessons Learned from Studying How Innovations Can Achieve Scale. Threshold 5 (1), 4–10.

Denton, C. A., and Hasbrouck, J. (2009). A Description of Instructional Coaching and its Relationship to Consultation. J. Educ. Psychol. Consultation 19 (2), 150–175. doi:10.1080/10474410802463296

DeWire, T., McKithen, C., and Carey, R. (2017). Scaling up Evidence-Based Practices: Strategies from Investing in Innovation. Rockville, MD: Report prepared for Westat, Inc. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577030.pdf (Accessed February 10, 2020).

Fishman, B. J., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A. R., Cheng, B. H., and Sabelli, N. O. R. A. (2013). Design Based Implementation Research: An Emerging Model for Transforming the Relationship of Research and Practice. Natl. Soc. Study Edu. 112 (2), 136–156.

Fullan, M. (2009). Large-Scale Reform Comes of Age. J. Educ. Change 10, 101–113. doi:10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., and Yoon, K. S. (2001). What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results from a National Sample of Teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38 (4), 915–945. doi:10.3102/00028312038004915

Gaudin, C., and Chaliès, S. (2015). Video Viewing in Teacher Education and Professional Development: A Literature Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 16, 41–67. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2015.06.001

Gee, D., and Whaley, J. (2016). Learning Together: Practice-Centred Professional Development to Enhance Mathematics Instruction. Maths. Teach. Edu. Develop. 18 (1), 87–99.

Hakala, J. S., MacCarthy, K., Dewaele, C., Wells, M., Dusenbery, P., and LaConte, K. (2016). STEM in Public Libraries: National Survey Results. Boulder, CO: Report prepared for the National Center for Interactive Learning Retrieved from http://ncil.spacescience.org/images/papers/FINAL_STEM_LibrarySurveyReport.pdf. doi:10.1109/educon.2016.7474586

K. S. Rosa (Editor) (2018). The State of America’s Libraries 2018: A Report from the American Library Association. Chicago, IL: American Libraries, 1–25. Available at: http://www.ala.org/news/sites/ala.org.news/files/content/2018-soal-report-final.pdf.

Levin, B. (2013). What Does it Take to Scale up Innovations? Report Prepared for the National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/scaling-up-innovations (Accessed January 20, 2020).

National Research Council (2015). Committee on Successful Out-Of-School STEM Learning Identifying and Supporting Productive STEM Programs in Out-Of-School Settings. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.