- Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development (OLPD), University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Introduction: A recent statewide principal survey revealed that Black principals are more likely than white and other principals of color to frame their workload as unsustainable. Scholarship suggests that Black principals specifically lack district-level support when navigating racialized resistance to their leadership from white faculty and families. Hence, this empirical scholarship examines the lived, racialized experiences of four Black principals working in historically and predominantly white school districts in Minnesota.

Methods: Specifically, this scholarship leverages qualitative methods (e.g., interviews) to understand Black principal’s perceptions of sustainability in the principalship; the nature of resistance from white families, faculty, and staff; the organizational working conditions (e.g., district supports); and their career plans within the district and/or profession.

Results: Three themes emerged from this data: 1) Black social suffering, 2) Costs, and 3) District (Un)readiness.

Discussion: This scholarship offers important implications for increasing the sustainability and support of Black principals within the field. Moreover, it provides critical insight into how district leaders can and should specifically support Black principals and interrupt school, district, and community-based, anti-Black resistance.

Introduction

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic ushered in one of most interruptive events in the history of American education. K -12 public school operations were fundamentally ruptured in several ways (e.g., distance learning, online professional development, meal deliveries). Particularly, the approaches of our schools to teaching, learning, and leading were dramatically reconsidered and reorganized to meet the demands of that time. This turbulence specifically ushered in a catastrophic fracturing of Black lives (Horsford et al., 2021). Beyond the seemingly insurmountable health crisis, we also experienced the latest iteration of Black public death(s) and dehumanization; this calamity was compounded by the surfacing of technological inaccessibility among historically disenfranchised communities, exacerbating entrenched access issues to quality education. The pandemic severely pressed an educational system to respond in ways it had not been properly prepared to. When the smoke seemed to clear, instead of taking this opportunity to reset the system (Ladson-Billings, 2021), districts began reinstating some of the old norms and inadequate policies of past iterations of American schooling. Given the history of American schooling for Black people, Ladson-Billings (2021) explains that the hastiness of schools to return to normal was/is a process that all but secures continued Black suffering. However, this time, it was slightly different in some district contexts. As a response to the increased awareness of Black public death, districts brought in neoliberal equity sensibilities and initiatives (e.g., rise of equity directors or hiring Black and Brown educators/leaders) (Lewis et al., 2023).

School closures, white flight to outer-ring suburbs and private schools, COVID-related displacements of communities, and increases in school choice options (e.g., open enrollment) meant that some historically white school districts would experience significant shifts in the racial makeup of their schools. Especially in “liberal” states and local contexts, districts responded to these changes through mass hirings and restructurings of district cabinets to attend to the “new challenges” and equity needs related to a shifting racial demography (Irby et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2023). Yet, the hasty, reactionary decisions to hire Black leaders specifically rested on a set of logics that could sustain leadership discontinuity. As Peters (2011) suggests, the reliance of school districts on reactionary logics instead of strategic hiring plans all but ensures school leadership instability. To be sure, no educational leader could have properly prepared for the catastrophic impact and interruption of an international health crisis and its lingering effects. Notwithstanding, the pandemic highlighted the unpreparedness of historically and predominately white school districts to respond to changes in the racial makeup of their schools. In this paper, I argue that the reactionary hiring of Black principals into predominately and historically white school districts, without proactive planning, is a particularly dangerous practice. Given the severe underrepresentation, lived institutional realities, and continued, urgent need for Black principals in public K-12 schools, it is imperative that all school districts, but especially those that are rapidly diversifying, are conscious of the necessary conditions to sustain Black school leaders.

In this paper, I attempt to shed light on the lived realities of four Black principals recently hired (since 2020) and working in predominately and historically white districts in Minnesota. Specifically, I aim to unearth and critically examine the motivations of districts to diversify their leadership as well as the limitations of those hiring initiatives. Utilizing Racial Opportunity Cost and BlackCrit framings, I will interrogate the readiness of districts to support Black leadership and critique the limitations of hiring Black principals as a response to shifting district demographics and political climates. Moreover, I situate this scholarship under the umbrella of dynamic leadership succession planning to make sense of district preparedness to sustain Black principalship (Peters, 2011). In what follows, I attempt to connect these pseudo equity moves (i.e., Black principal hiring in the wake of social unrest and amidst demographic change) to the literature on district succession planning for principals (Peters, 2011; Peters-Hawkins et al., 2018).

Succession planning and sustainability

Peters (2011) defines leadership succession planning as a dynamic process focused on sustaining cost effectiveness, reducing turnover, and providing “smooth transitions” for new leaders in often historically divested and destabilized urban school environments. Leadership stability is critical because of its relationship to staffing consistencies, student achievement, and other key determinants of the overall sustainment of youth and communities. Peters-Hawkins et al. (2018) offer a critique of traditional succession planning, stating that these “efforts may advantage the organization’s broader goals over the professional goals of the individual” (p.29). Hence, Peters (2011) offers a framework that challenges district leaders to see succession planning as a cyclical praxis that prioritizes forecasting, sustaining, and planning. Forecasting focuses on planned openings in the principalship, sustaining refers to the efforts to build the capacities of aspiring leaders in the district-community, and planning highlights the importance of being well-prepared for a change in leadership, ensuring that outgoing and incoming leaders are in the community. This framework uniquely situates a process that could help districts avoid generating turbulence in historically divested, and mostly Black, school communities.

This framing offers a theoretical and conceptual grounding that spurns more specific questions about Black principals hired into historically white spaces. Given the response to pandemic crises and racial reckonings, I wonder if these school districts had a dynamic succession plan. Although district leaders could not have foreseen the significant interruption of an international health crisis and the subsequent turbulence in the educator labor market in some schools (Goldhaber and Theobald, 2023). Peters (2011) framing suggests that a commitment to smooth transitions (planning) and sustainment (developing future district leaders) should have been in place to help stabilize the principal workforce amidst the stated conditions. Arguably, the reactionary hiring of Black leaders to respond to rapidly diversifying school contexts and liberal, equity discourse could have (un)intentionally invisibilized the humanity of Black principals in the hiring process. Therefore, I wonder if district leaders considered the sustainability of Black administrators specifically in predominately white spaces. Moreover, I am curious about the tension between the primacy of systems and organizational goals (e.g., diversity, DEI initiatives) and the humanity and sustainability of Black leaders, as alluded to by Peters-Hawkins et al. (2018). In what follows, I consider the notion of succession planning, specifically leadership sustainability, and its relationship to the intersections of the Black principalship, antiblackness, and historically and predominately white school districts.

Literature review

Importance of Black principals

Scholarship recognizes the unique commitments and impact of Black principals on Black youth (Lomotey, 1987, 1993, 2019; Gooden, 2005). Historically, Black principals served as the lifeblood of segregated Black educational communities (Walker and Byas, 2009). Black principals operated as community-situated visionaries, public intellectuals, and intermediaries between white district leaders and Black schools and were committed to leveraging community-based assets to co-organize the optimal learning environment for Black youth (Walker, 1996, 2000). The deleterious, one-sided 1954 Brown decision and subsequent desegregation efforts closed Black schools across the South. Hence, Black principals were either fired or demoted to other positions in newly desegregated school communities (Fenwick, 2022; Tillman, 2003).

Despite the impact of mass dismissals, more contemporary Black principals continue to have a deep influence on Black youth. Lomotey (1987) and Gooden (2005) explain that the ethno-humanist Black principal offers students an empathetic touch that centers their humanity through relational dialogue; they lead with a commitment to Black possibilities and compassion for Black life and motivate Black children to realize their potential. Bass (2012) and Witherspoon Arnold (2014) discuss the explicit ways that Black women principals center Black Feminist and Womanist epistemological stances to collectively support and center Black youth in leadership decision-making. Black women principals are well-equipped to recognize intersectional forms of school-based oppression and center Black community-based epistemologies and perspectives (e.g., communalism, spirituality) to help Black youth navigate oppressive school conditions (Peters and Miles Nash, 2021; Horsford, 2012). That is, despite schools being imbued with anti-Black rhetoric of Black students (e.g., Black students are less capable learners), Black women principals leverage holistic, spiritual, and caring practices to humanize Black youth daily (Peters and Miles Nash, 2021). Black principals further center cultural and community-based knowledge through culturally responsive and community-engaged educational leadership praxis (Gooden, 2005; Green, 2015; Khalifa, 2018; Reed, 2012; Stanley and Gilzene, 2023). This critical praxis is a further iteration of the ways that Black principals led Jim Crow schools (Walker and Byas, 2009).

Other scholars detail how Black educators and leaders can interrupt discipline disproportionalities and increase access to gifted and talented courses for Black youth (Grissom et al., 2017; Lindsay and Hart, 2017; Welsh and Sobti, 2023). I mention this scholarship to briefly highlight how Black principals can and do improve the conditions of schools to generate greater access and opportunities for Black youth. Welsh (2024) further complicates some of this literature, suggesting that the presence of Black principals does not in itself always lead to major changes in disciplinary exclusion; Welsh (2024) suggests that this work is more nuanced, contextual, and mixed. Differently, Jang and Alexander (2022) suggest that there is a positive relationship between the instructional strategies of Black women principals and Black student achievement. This scholarship centers state- and school-based measures of success, which have little to do with the liberation of Black minds and souls. Given the colonizing, containment of contemporary state institutions, and the contempt that they hold for Black bodies, racial congruence alone will not eliminate the suffering of Black youth and communities in schools. My primary argument is that Black principals have the potential to do much more than redress the ills of institutional policies and practices. Yet, I argue that these are the metrics that district leaders utilize to inform contemporary workforce diversity moves, especially post-pandemic.

Black principals, “tapping,” and the leadership pipeline

I will use this section to briefly highlight the ways that principal pipeline inequities sustain the dominance of white principals in the field (Taie and Goldring, 2020). Despite promise and influence, Black principals often experience turbulent journeys into the profession (Bailes and Guthery, 2023; Weiner et al., 2022). Perrone (2022) offers some important research that suggests Black principals and other principals of color experience exclusion in the preparation process. Despite their credentials, they are less likely to ascend to principalship than white principals. Berry and Reardon (2022) explain that “although Black principals have the prerequisite knowledge, skills, and abilities in preparation for the principalship, their preparation path may be subject to containment” (p.48). Utilizing the Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), this scholarship names that Black principals are sometimes more likely to acquire external credentials than white colleagues, but they continue to experience exclusion from the profession due to internal barriers like same-race tapping (Berry and Reardon, 2022; Myung et al., 2011).

Myung et al. (2011) explain that tapping is a largely informal practice by which current leaders approach and encourage teachers to pursue principalship; leaders identify people who they believe show leadership potential and are more likely to “tap” teachers who share their same race and/or gender identities. Myung et al. (2011) suggest that tapping is a pervasive tactic employed by districts across the country. The informality and lack of intentionality of this process exist in tension with the logic of dynamic succession planning (Peters, 2011). First, school leaders, especially in suburban, historically white school districts, are more likely to be white. Additionally, for Black principals, there is a clear throughline of Black leader disregard and containment, which can be traced back to the mass demotions and dismissals of Black principals despite them often having greater credentials than their white colleagues (Fenwick, 2022). Further, (un)planned tapping (and hiring) as a practice does not critically interrogate the sustainability of the principalship, especially for Black principals; this practice does not consider the alignment between the broader district goals, changes in district needs, and the future leaders ascending to the principalship. As such, for Black principals, the pathway to leadership can be turbulent, confining, and incongruent with their own unique needs, thus sustaining the enduring leadership pipeline inequities.

Institutional-organizational experiences of Black leaders

Black principals must also navigate institutional spaces that are unprepared to sustain them (Stanley, 2024). Krull and Robicheau (2020) name the impact of racial battle fatigue and microaggressions as key mechanisms that can produce exhaustion and stress. Daily microinsults from colleagues and families have a grave impact on the emotional, psychological, and physiological well-being of Black principals (Armstrong, 2023; Krull and Robicheau, 2020). These anti-Black institutional experiences can be exacerbated in suburban and predominately white contexts (Burton, 2023). As cited in Burton (2023), Omi and Winant (1994) explain that suburban America was founded on the logic of white supremacy; self-segregation by white people (i.e., white flight) created predominately and historically white schools (Diamond and Posey-Maddox, 2020). Using inter-group conflict and color-blindness as a framework, Madsen and Mabokela (2002) state that Black principals working in these contexts experienced ideological misalignment with white colleagues; that is, conflict arose when the dominant, white ideologies were in tension with efforts to alleviate school suffering for Black youth (e.g., discipline inequities). Jansen and Kriger (2023) extend this idea by centering the interiority of Black principals who are the “firsts” to lead in predominately white school communities in post-apartheid South Africa. The authors explain that “the awareness of the racial self…emerges out of an inescapable relationship that Black principals must form with their white colleagues on a daily basis…they must constantly recalibrate their internal understandings of who they are” (p.237). Collectively, this scholarship highlights the inter-organizational and contextual tensions that complicate the lives and sustainability of Black principals.

antiBlackness and Black social death in educational leadership

As stated above, I acknowledge the Black intellectual and leadership legacies, which are critical to Black principalship. Black principals have collectively created the conditions for Black joy and possibility, both historically and contemporarily. Yet, I also want to clearly name the anti-Black foundations and sensibilities that are inherent to the field of education, educational research, and educational leadership more specifically. A brief historical analysis of Black educational exclusion (e.g., anti-literacy laws), the sustained cultural disregard and dehumanization of Black youth (e.g., discipline inequities, spirit-murdering), and the severe underrepresentation of Black teachers and leaders in most school districts collectively highlight the pervasive anti-Black realities in this field (Anderson, 1988; Dumas, 2014; Stanley, 2022; Stanley, 2024).

Educational research continues to dehumanize Black youth through gap-gazing, under-theorizing, and centering methodologies, which reinforce deficit notions of Black people (Scheurich and Young, 1997). Further, the practice of educational leadership remains heavily steeped in “great man,” Eurocentric ideas, and managerial practices which, in racially diverse schools, rest on logics premised on the control of Black bodies; this is not a product of historically Black educational intellectual and leadership traditions (Khalifa et al., 2014). I argue that Black youth, families, classroom teachers, and principals are uniquely tethered to a set of logics predicated on their demise, dehumanization, and control (Stanley, 2024). Further, to alleviate the intimate relationship with Black social suffering/death and disregard, we must intentionally confront antiblackness as a mechanism that operates within Black principalship. That is, the underrepresentation and instability of the Black principal workforce is, arguably, tied to a broader colonial project that is threatened by non-white permanence (Wolfe, 2006), specifically in the principalship. In what follows, I will discuss how I think about antiblackness and its relation to this research through BlackCrit (Dumas and ross, 2016). To be clear, I center BlackCrit as a “neater” framing of the ways I seek to theorize antiblackness in the Black principalship; I recognize that the intrusive ways that antiblackness interrupts Black life and possibility are more expansive. Further, I utilize Racial Opportunity Cost (Venzant Chambers, 2022) as a framework to make sense of the “costs” associated with Black principalship.

Minnesota context

Importantly, and despite expressed liberal, moral, and political commitments, Minnesota is not exempt from historical and contemporary forms of Black exclusion, particularly in PK-20 education. Historically, Minnesota, as a state, has positioned itself as morally and politically distinct from the U.S. regional South (Montrie, 2022). Yet, scholars like Chad Montrie and William Green name the pervasiveness of whiteness/white supremacy and intentional racialized injustice as a “hidden” part of Minnesota’s social history. For example, Black Minnesotans have had their thriving communities, like the Rondo neighborhood, completely destabilized by local zoning and housing policies; further, white school communities have engaged in anti-Black programming like public minstrel shows while simultaneously propagandizing their moral elitism (Montrie, 2022). Historical evidence suggests that the sustained disregard for Black life is a lesser known but significant aspect of Minnesota’s history.

Black educators and leaders in Minnesota

Today, we find that Black educators and leaders experience significant underrepresentation and marginalization in the field. Specifically, 95% of teachers in the state are white, with only 1.4% of educators identifying as Black (Carter, 2021). 90% of Principals are white, and in a recent statewide survey of 1,000 school administrators, only 4% or 31 respondents identified as Black (Kemper et al., 2024). Consistent with the literature, Black principals in this state are more likely to cite student demographics and opportunity for impact as key factors in where they choose to work (Kemper et al., 2024). Their commitment to seeing their students grow and develop is central to their job efficacy and satisfaction (Kemper et al., 2024). Yet, Black principals average fewer years of experience than white principals and plan to stay in their current positions for shorter periods than their white colleagues. One Black leader highlighted the conditions that make it difficult to persist in their role:

Being a Black leader in [a] mostly white community and among a white staff requires district leadership to understand how these racial dynamics impact mental health and create many barriers that are both passively and aggressively placed in the way by colleagues and the community. The leadership cannot believe their sympathy or empathy is enough, they have to have a strategic plan to support, recruit, and retain other Black leaders (Kemper et al., 2024, p. 61).

Collectively, these data suggest that not only are Black principals significantly underrepresented in the state, but they are also under-supported in ways that cause them to accrue specifically racialized costs (e.g., mental health). That is, the conditions of schools and districts are not conducive to the work, commitments, and sustainability of Black principals.

Given this context, I examine the following research questions:

Research Question 1: How do Black principals describe their experiences working in predominately and historically white school districts?

Research Question 2: How do Black principals make sense of their sustainability in these historically and predominately white school districts?

Theoretical framing(s)

I leverage Racial Opportunity Cost and Black Crit to critically analyze the lived social conditions and “costs” that uniquely confront Black principals working in predominately and historically white schools and districts. Specifically, Racial Opportunity Cost (ROC) (Venzant Chambers, 2022) highlights the psychological, community, and representational costs that Black and other people of color endure because of deeply racialized expectations placed upon them by white hegemonic narratives. Although this framework has been almost exclusively used to analyze the experiences of Black and LatinX youth, I am arguing that there are similar costs associated with being a Black principal in a predominately white school district. Black people must navigate and endure the double consciousness or the twoness of their being: Black and American (Du Bois, 1903; Venzant Chambers, 2022). In this scholarship, ROC names the factors that impose an undue burden on Black bodies trying to imagine themselves as successful on their terms and the terms of white hegemony.

Further, BlackCrit (Dumas and ross, 2016) names the anti-Black structural and institutional conditions that are endemic to the experiences of Black people and, in this case, Black principals. Further, I draw on BlackCrit’s suspicion of neoliberal multiculturalism to name and critically situate the limitations of hiring Black principals as de facto equity leaders. Neoliberalism in education often situates the marketplace as the priority and the Black as the perpetual problem needing to be fixed by state-designed education spaces. For example, Dixson et al. (2015) describe the neoliberal, hostile takeover of post-Katrina schools in New Orleans; specifically, the opportunity and market demand for charter schools secured the displacement of 7,500 employees in a predominately Black educator workforce. Cloaked by the promise of better schools, New Orleans’ Black communities’ futures continued to take a back seat to state-sanctioned, market-driven reform. I use these two frames to analyze the anti-Black structural and institutional conditions that create undue costs on Black principals. However, and consistent with BlackCrit’s commitment to freedom dreaming, I will highlight the promise, success, and impact of Black principals despite these conditions. Below, I will outline Racial Opportunity Cost and Black Crit in more detail.

Racial opportunity cost

ROC has intellectual roots in Du Bois’s notion of double consciousness or this idea that Black people live in a world where “one ever feels his twoness, − an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder” (Venzant Chambers, 2022, p, 3 from Du Bois, 1903 p.3). The constant navigation of the world through one’s own visions and framings and the piercing eyer of white hegemony is often a consequence of Black life. Venzant Chambers (2022) names this phenomenon utilizing an economic framing or analogy of opportunity cost. ROC suggests that, for Black people and other people of color, there is a cost for academic achievement; that is, to be academically successful, one may have to sacrifice key aspects of their cultural and racialized identities (Chambers et al., 2014). ROC proposes three costs: psychosocial, which is the racialized expectations placed on Black people’s psychological and emotional well-being; community, which names the potential fracturing between Black people and their communities; and representation, the burden of being the representative for the entire racial group and the “ambassador of diversity” (Venzant Chambers, 2022, p. 12).

ROC calls attention to the school, intersectional, and capacity factors that influence and mitigate the costs endured by Black people in educational spaces. School factors include climate, policies, practices, and values, which create the conditions and expectations of Black people in the school. For example, Venzant Chambers (2022) names that schools center white-normed institutional scripts that dictate how Black and LatinX students must behave to be successful. Intersectional factors highlight the complexity of identity and how race is but one way to exclude Black people in schools. That is, schools must create space for the multiplicity and depth of identities across race, class, gender, and other intersections. Finally, capacity factors highlight the internal or external non-school supports that may help Black people sustain themselves within educational institutions. Family, friends, and mentorship outside of school can provide a unique safety net that specifically supports racialized and cultural identities.

Black Crit

Black Crit is a response to the cultural, social, and political disregard of Black life. It centers three key understandings: antiblackness is endemic and central to our understanding of human life; antiblackness exists in tension with neoliberal multiculturalism; and BlackCrit challenges us to imagine a Black liberatory fantasy, free from the remnants of bondage and enduring oppression (Dumas and ross, 2016). Drawing from the works of Black studies’ scholars Wynter, DuBois, Hartman, Wilderson, and others, Black Crit theorizes the supposed and sustained inhumanity and inherent slaveability of the Black. Specifically, Dumas (2014) names that anti-Black social suffering is an endemic and enduring reality of Black life. That is, the inability to recognize the Black person as human renders any and all parts of the Black’s social, cultural, and political life as disposable, replaceable, and unremarkable in American and global society. Hence, Black “contributions” to society are positioned as eerily oxymoronic (I say eerily because there are historical and everyday evidence(s) of our contributions and advancements in global society).

Together, I utilize these theoretical frames to critically examine the lived realities of Black principalship in liberal, white school spaces. Specifically, I ponder the anti-Black sentiments that can lead to social suffering in the Black body. Further, I think about the psychological and identity-related costs associated with trying to navigate overwhelmingly and historically white spaces as a Black leader. To be clear, the principals in this study represent different intersecting identities and communities. I do not propose that these framings will, nor can, fully capture the nuanced experiences of Black diasporic peoples. Race is but one way to illuminate the ills and possibilities of the Black principalship.

Methods

This project utilizes a qualitative, narrative interview study design that centers open interviews as the primary text (i.e., narratives) or source of data (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). I leveraged humanizing research practices to build a relational rapport with each Black principal highlighted in this study (Paris and Winn, 2014). Specifically, I reached out to each principal via email and introduced myself, my K-12 experiences, and the research that I was engaging in. Once they agreed to participate, I conducted four 60-90-min interviews via Zoom; I recorded each interview with the written consent of each Black principal. To be included in the study, principals had to identify as Black, work in a predominately and historically white school district context, and have been a principal for at least 1 year.

I centered open interviews as a method to better understand the ways that Black principals narrate their entry into the profession, experience the principalship in their districts, and made sense of the sustainability of Black principalship (Denzin, 2014). As Merriam and Tisdell (2016) explain, first-person accounts of experiences constitute the narrative “text” (p.34). Also, by centering on humanizing methods, each interview was a communal dialogue among two individuals who shared similar experiences in K-12 school leadership. That is, I, as the interviewer, entered the interview process with a grounded discussion of our shared histories and experiences working as Black educational leaders in K-12 school districts. Further, interview questions were intentionally designed to reflect and better understand the data published in the Minnesota Principals Survey (Kemper et al., 2024). For example, some questions asked about the intersection of racialized dynamics and well-being; these questions come directly from survey data, which highlights the impact of the job on Black principals’ mental health.

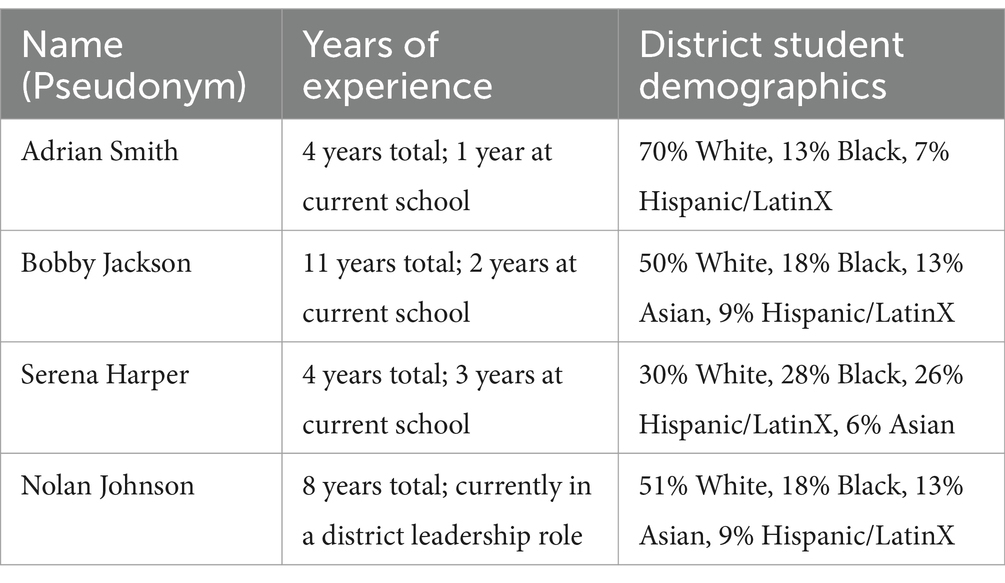

I engaged in two rounds of iterative coding processes (structural, process, and In Vivo) utilizing Dedoose software (Saldaña, 2021). In the first round of coding, I centered ideas from BlackCrit and ROC to better understand the lived experiences, institutional and district contexts, and navigational tactics utilized by Black school leaders. These lenses revealed the underlying racialized and anti-Black tensions, which destabilizes their work as Black principals. In the second round of coding, I focused more attention on In Vivo coding processes to capture the nuances of the principal’s sense making. I used thematic analyses to categorize and synthesize the data in alignment with the broader theoretical framings and the empirical understandings of the Black principalship (Esposito and Evans-Winters, 2022). These processes revealed three key themes: Black Social Suffering, Costs, and District (Un)readiness. I attended to trustworthiness through thick and rich description and data triangulation (interview transcripts, relating with other transcript data, and reflecting on the survey data) (Anfara et al., 2002). Next, I will briefly introduce the challenges, commitments, and liberatory possibilities offered by four Black principals (see Table 1).

Black principal’s challenges, commitments, and possibilities

Adrian Smith

Adrian is a Black, Somali male who is entering his second year as a high school principal. Adrian was a graduate of this high school. He stated, “It has been a goal of mine to return to this high school and be the leader of it.” Adrian explained that his family immigrated from Somalia to the United States; education was vitally important in their home and surrounding community. He describes that during his time at the local schools, he was often one of only a few students of color. To achieve “academic success,” Adrian “just aligned to what the system wanted [him] to do.” Throughout our dialogue, Adrian openly reflected on the “cost of success” in his hometown school district and the ways that he attempts to interrupt and resist systems of oppression for Black students as the principal.

Bobby Jackson

Bobby Jackson is a Black male principal who is entering his third year at his elementary school. He describes his 11 years in the principalship as a journey filled with allies, relationships, perseverance, isolation, and spiritual navigation. Central to our discussion was Bobby’s multiple experiences with isolation. In some cases, he was the only Black administrator or one of two Black administrators in his district. He explains that when he came into his current district, “there was a large number of administrators of color that came over, and that was huge. But now I look up 2 years later, going to year three, everybody left, and it’s down to just two of us.” Despite these realities, Bobby sees himself as a leader who continues to have tangible impacts on Black students’ lives. “Whatever harm I went through, or whatever I did, I was able to change and impact lives. That’s why I do this at the end of the day.” Bobby remains committed to the field but recognizes that larger systemic change is necessary and is, therefore, considering a move into central office leadership.

Serena Harper

Serena is a radically pro-black, Muslim, Somali mother and elementary school principal. Serena is entering her second year as a principal at her school; she was the first Somali female principal to be hired in the district. Serena brings her Somali community knowledge and social work background to the principalship in ways that challenge systems and practices that seek to disregard Black youth and families. She stated, “that’s my biggest resistance, defending the humanity of Black kids and letting people know, like, our kids are great.” Because of her commitment to Black youth and families, Serena describes moments where the white district community wanted to push her out; as a response and to demonstrate her commitment to leading in the space, she moved her family to the district and enrolled her kids in the schools. “I remember having opportunities to be unapologetic and what I stood for, not just for my son, but for all [Black] children, and just being able to…humanize and remind staff our job is to create a safe community where children can make mistakes and learn from those mistakes.” Throughout our conversation, Serena highlighted explicit experiences with pushout, racialized harm, and exclusion, yet she leans on her faith, community, and commitment to Black children as fuel to significantly interrupt systemic, racialized oppression.

Nolan Johnson

Nolan identifies as a Black male public servant who has a deep historical connection, lineage, and commitment(s) to his local community. In only 8 years as a licensed administrator, he has been the first Black principal in either his school or district three separate times. He explains that he was “fast-tracked” into the principalship in his early twenties. Now, only in his mid-thirties, he has transitioned into a district administrative role. Throughout our conversation, he explicitly names the costs that he accrued as a school administrator in a predominately white space that was not prepared for him. He explains, “I’m worried about Black men in leadership.” Nolan describes that Black male leaders, in particular, experience immense pressure, heightened stress, and threats to their mental well-being. There is a real concern for the sustainability of Black principals in state school districts that are unwilling to reckon with their racialized realities. Nolan also underscores some significant impacts of the Black principalship: hiring equity liaisons, instituting student feedback loops, and supporting culturally responsive instructional practices. Nolan explained that under his leadership, the new equity liaison was hired to develop “a multicultural resource center for students and in our community…networking [with] students and families, mentorship, scholarships, and opportunities.” Despite the reality of the conditions surrounding the Black principalship, Nolan has found unique ways to outmaneuver systemic oppression and uplift Black youth and communities.

Themes

As mentioned, this study reveals three important themes: Black Social Suffering, Costs, and District (Un)readiness. The Black Social Suffering theme offers an institutional analysis of the Black principals’ encounters with direct and indirect antiblackness. Each principal discusses a key event that forced them to interact with the anti-Black sensibilities of their working context. Costs highlights the collective psychosocial, emotional, and physical impact of working as a Black principal in anti-Black school contexts. This theme names the ways that Black principals endured and made sense of the racialized assaults experienced in their schools and districts. Finally, District (Un)readiness captures the ways that these leaders’ critique white district leadership and their inabilities to provide responsive support for Black principals.

Black social suffering

Drawing from Dumas (2014) conceptualizes Black social suffering in education as a shared group consciousness of pain. That is, specifically in education, there is a shared experience among Black people that is connected to loss, hopelessness, and everyday suffering. Dumas (2014) delineates the nuances between larger structural forms of suffering (e.g., poverty) or Bourdieu’s (1999) notion of grand misère and la petit misère, the everydayness of suffering commonly referred to as racial microaggressions. This framing is especially important in morally liberal contexts like Minnesota; one could inaccurately assume that significant racialized traumas are not central to the lives of Black, middle-class people (i.e., principals). Hence, I will utilize this framing to analyze the shared consciousness of social suffering experienced by Black principals in their schools and districts.

Grand misère: district-community context

Bobby and Nolan explain that they were both initially attracted to districts that had recently become more racially diverse, hired Black and Brown leaders, and expressed commitments to equity and justice. Nolan posits, “I was drawn to this district because of what I saw on paper.” Differently, Adrian describes being more internally motivated to work at his alma mater and in his community. Despite their differing motivations, they collectively experienced the brunt of racialized resistance from teachers, central office leaders, and the surrounding community. Bobby explains his situation in a previously predominately white district, “[I was] the first [Black] principal in that district and the only principal of color for eight years, I faced death threats, racial harm….”

Further, on two separate occasions, Bobby and Nolan had encounters with teachers who hurled racial epithets at Black children. Bobby explains “I had an instance in my school recently where it was the teacher…he was a coach…that said the N word.” “My first year there was a coach who used the N word, offended many families. The coach was suspended and brought back. Nobody talked to the Black players on the team about how they felt. Nobody talked to their families. Brought them [the coach] back. But once, there was some Jewish, Islamaphobic…language being used. Eventually, the district started trying to react towards that. And so now…you got the African American families like, wait we [were] harmed. You did not even check on us, right?”

Nolan describes a very similar event with a basketball coach and connects this to a lack of support with central office. He explains,

A high-profile basketball coach that used the N word in basketball practice…we put them on leave and activated an investigation. There was lots of scrutiny around that decision and lots of feedback from the community. Ultimately, I was told the coach was being reinstated and this is a person that was in my building and my employee, and I was pretty clear about what I was expecting in terms of an outcome, and I did not get to make the final decision. I think [this event] really highlights there are absolutely lots of folks in the leadership space that I think are curious about or interested in or supportive of diversifying their leadership teams, [except] when it comes down to making a decision that will activate discomfort for you as a white leader or white systems’ leader.

In both cases, Nolan and Bobby describe the structural and explicit forms of Black disregard often experienced by Black people in education. Racialized harm was perpetuated against Black students, families, and principals; their shared feelings were not properly acknowledged. Black principals’ leadership and “authority” was undermined by white central office leaders who thought it best to reinstate the coaches against the wishes of the school leaders. Further, as Nolan describes, Black principals had to endure the everyday reminder that both their positional authority and psychosocial safety were and are disposable.

La petit misère: institutional context

Black principals also describe the ways that antiblackness shows up in their daily lives as school leaders and community members. That is, they can and often do experience the subtle yet impactful pricks of anti-Black sentiments from white families, colleagues, and others who live in the community. Specifically, Serena names the impact of limiting and deficitizing narratives from white teachers about her abilities to lead the school. In our discussion, Serena describes two specific white women and the white racialized resistance to Serena’s principalship: “They made it a point to rally people in the building, you know, against me.” She extended,

I remember…my first year there was anonymous box in the staff lounge. And, you know, being new, I just went along with it. I was like, sure, let us do the anonymous. But in reality [it] became more direct attacks about people being frustrated about things. And then, you know, there was an anonymous survey that was filled out, and the results were shared with me, and it consisted of a lot of untruthful things. And I remember talking to people, those two white women, and saying…like this did not happen. There was a report that I berated a staff member, and that’s just not how I move in the world. I do not berate people. But this was said that I had done. And there was feedback about me not trusting the teachers and making them call parents…And I was like yeah…because you sent a paper home to a family asking really sensitive information, and forgot to, like, call them to tell them that this was coming home. So you came to me, and you had time, and I was here, so we made the call together, like context matters. So it was hard.

Serena highlights the ways that white emotionality and the neoliberal (i.e., ruggedly individual) passive-aggressive context of Minnesota can spurn anti-Black sentiments against Black principals. In this discussion, Serena highlighted the untruths and the resistive nature of the white women teachers; they were willing to sacrifice basic protocol and ethical practice (i.e., communicating with families) to resist Serena’s leadership. Further, when redirected, instead of admitting oversight, they proceeded to cast untruths onto Serena. Serena found some shared experiences with another Black female administrator in her district. She reflected, “just hearing [another Black administrator] experience navigating this situation too. So there’s just a culture here where when white women are upset that the system stops literally and does its best to just make things better.”

Adrian describes a more indirect assault on his personhood as a Black male principal. He explained,

I remember…one comment to a teacher that I highly respect…I just threw it out there…from my perspective as a Black man. And I said to her one time, because they kept saying, “well the district is…kind of handcuffing you. It’s you know, you are kind of handcuffed.” They use this loosely handcuffed…” It’s not really your decision. It’s the district”…And I just said, you know, with all due respect, as a Black man leader, as I continue to hear this handcuff, handcuff, I just want you all to know that phrase or that does not sit well with me, and we can, I can go deeper into this, but it’s just not the time right now. But please just be mindful of what you are using, you know, what you are sharing.

The casual yet harmful language of “handcuffing” was a trigger for Adrian. For him, it highlighted the continued over-policing of Black male bodies and the resultant public deaths of Black men. Further, it calls attention to the continued disregard of Black life, which is often perpetuated by casual yet symbolically violent language. The assaults on their humanity from colleagues and the community contributed to the dysphoric and sometimes bewildering contextual realities (i.e., costs) for Black principals.

Costs

Each principal discussed their own unique experiences being the first and sometimes the only Black principal or leader of color in their schools and/or districts. These shared realities, in many cases, had a significant impact on their social and emotional well-being. Adrian described, “I’m the only person of color in the district leadership team, the entire industry. So, I want to say 60 people or so. Only person, yeah, yeah, that’s tough.” Differently, Bobby describes some of the “costs” when he was first hired as a teacher in a school district. “And there was a point where I moved…and came here to Minnesota and was teaching, and I was put in a situation where I felt, as a Black male, I was just a check on the box. I was a checkbox teaching a cultural class, and I was the only…person in the building of color, so I did not feel supported…I left at the end of the day after a year and a half.” After walking away from the field for a brief time, Bobby’s passion for students brought him back to an elementary school teaching position and he began his master’s program in educational leadership. Yet, the costs followed him into principalship. “There was times in the year where I may have questioned like, man, is this something I still want to do?”

For Nolan, the primary cost was due to the pressures associated with being a young, Black male leader in a district that had never seen one. In describing his previous district, he explained,

You know students of color in these highly racially isolating environments. Oftentimes were just kind of in survival mode, in terms of navigating their identity, or kind of in survival mode in terms of responding to those negative experiences that they were having as it relates to race.

Nolan explained that racial isolation was the primary issue that students of color faced in his district. However, when he and other administrators of color were hired, student survey results revealed a higher sense of belonging among Black and Brown youth. Nolan was able to provide support to Black youth in his building; the costs that he would incur from this support had just begun.

Nolan posited,

I would characterize some of what I navigated as just working through, perhaps a sense of imposter syndrome. And like there was a real, reality that, like my presence or perspective wasn’t welcome…it’s a lot of pressure, I think there is a real scrutiny that’s different, and you know, I recognize, like, imposter syndrome. I would try and internally [manage the stress] and [manage it] with peers or others…try and put a positive spin on it and I think that was important for sustaining like high levels of engagement or enthusiasm about the work. Um, but what I failed to do was, um, fully acknowledge and allow myself to experience the weight that I was carrying.

As Venzant Chambers (2022) alludes to, there are significant representational and identity costs associated with being Black in predominately white spaces, which have placed superfluous expectations on Black leadership. Evidenced through these accounts, we find that Black principals, because of their unapologetic commitments to Black youth, also endure the costs of being the only Black leader, role model, and example for all Black youth in the school. These experiences generate a kind of racialized pressure that causes psychological stressors, and district leaders have yet to find ways to mitigate these realities. These stressors were exacerbated by white district leaders who were unprepared to redress racialized harm, exclusion, and isolation.

District (Un)readiness: hiring without support

A clear throughline across the principals was this willingness to name the lacking support from district leaders and the seeming unpreparedness for Black leadership in their school contexts.

Nolan highlighted.

we started to, as a system, like, experience skepticism from our community that I do not think the system was ready for. And, and I was…part of a cohort of lead principals that were hired in a short amount of time…and a majority of those hires were leaders of color and so all of a sudden, the system started to have to navigate principals being scrutinized at a higher level.

Nolan’s summation frames the district-community tensions associated with the increase of Black educational leaders in a predominately white district that was used to predominately white administrators. The shift in some ways shocked the school system; this shock led to uncertainty and a sense of unpreparedness for the white district personnel.

Bobby described that when he came over to his current district, he started to notice Black leaders whom he had met in other spaces. However, Bobby describes, “as time went on…to peel back the layers…you saw it for what it was…I saw how my other brothers and sisters, then slowly was starting to get treated, and slowly getting pulled into the office, and slowly getting talked to. So then they started leaving…so now it’s down to two of us.” I followed up with questions about why the leaders were being called into the district office. Bobby explained that most of the reasons were related to phantom allegations where the investigation into an incident found no wrongdoing. Bobby suggested that the impetus of the described antagonism against Black principals was connected to community pressures (i.e., white racialized resistance). The district, specifically the Black assistant superintendent, was hiring Black leaders as a response to the recent influx of Black and Brown students (via open enrollment policies). As such, the white community response was oppositional: “the way the school district operates…is different than how the community wants to operate…So the [white] community feels a certain way…Change is uncomfortable.” “I like how things used to be. Why are we changing things? What’s all of this?” Bobby cites white families’ concerns with and resistance to the changing face of school leadership.

Serena names the unsupportiveness of white central office administrators as a key issue when she was hired as the first Black Somali woman in her district. Reflecting on her initial experiences with the white women teachers who were trying to push her out, she offered,

And what made it…harder too is like my leader, who recruited me to come, good white man, but is on his equity journey too, held space for the white people to talk to him. So there was an undermining of leadership. But the intent was positive…But what that did was…created space for them [white educators] to talk to my supervisor. So really hard.

Serena’s recount of her early experiences in the district underscores another way that white senior leadership, despite good intent, can be ill-equipped to support Black administrators in predominately white districts.

Differently, Adrian recounted that he felt and experienced boundary heightening and role entrapment the summer before beginning the principalship. He stated,

A lot of people had talked to me quite a bit last summer or sent me an email about this… “We need to be [about] order and consequences. You know kids need to be in class Mr. Smith, you’d be surprised about the students that hang out in the flexible areas or just common areas”…As I entered into the first couple of months, it was Black students, Black students, or students of color that really spend majority of passive time there…

Later in our conversation, he explains that the racialized overtones of the white educators were connected to their own deficitizing beliefs about Black people and what the role of a Black principal is regarding their concerns. He questions his staff’s preoccupations with addressing Black student behaviors “not [to] necessarily address, the behavior, adult behavior…like the law and ordering of the building, yeah, how they see it.” Adrian calls attention to the distance between Black principals’ beliefs about their roles and the limited imaginations of white educators, which only allow them, in this case, to see Black principals as disciplinarians. Brown et al. (2018) liken this role entrapment of the Black male educator to this notion of the Black pedagogical kind.

In sum, Black principals in this study narrate the specific experience of racialized isolation in historically and predominately white school districts, which can be particularly insufferable. This is especially true given the antiblackness, which is pervasive and tangible in historically white suburban school environments. Further, their collective experience outlines the inabilities of district leaders to create the conditions that mitigate the sustained disregard for Black life and leadership visions. Yet, Black principals in this study (re)member and cling tightly to their commitments to alleviate the suffering of Black youth and communities.

Discussion: (neo)liberality and antiblackness in the Black principalship

This scholarship offers a brief glimpse into the challenges of Black principalship in predominately and historically white, liberal school-district contexts. The principals reveal the limitations of Black leader hiring initiatives in predominately white school districts as de-facto equity planning/response. That is, these school districts were severely unprepared for Black leadership visions that seek to uplift and liberate Black youth who are learning in deeply oppressive contexts. Each principal offers important evidence that their school districts have yet to intentionally name and commit to understanding the ingrained nature of anti-Black racism before hiring Black school leaders. Hence, Black leaders were thrust into spaces where they would experience a diabolical mix of public assaults (grand misère) and everyday suffering (la petite misère).

The Black principalship as an unsustainable site of suffering

Stanley (2024) posits that Black educators, leaders, students, and families are uniquely tethered to a shared consciousness of anti-Black suffering and Black social death. “Tetheredness” means that, despite supposed positional authority, the Black principal is not absolved from experiencing anti-Black disregard and disposability. As Dumas and ross (2016) explain, “BlackCrit intervenes at the point of detailing how policies and everyday practices find their logic in, and reproduce Black suffering” (p.429). Reflecting, I think about what this tetheredness means for Nolan who experienced his basketball coach use the N word as a form of violence against Black youth and was subsequently reinstated to work in his building. Black students experienced a direct assault against their humanity; their communities were not offered any form of repair. The Black principal who employs this coach, after requesting his dismissal, is instead forced [by central office leadership] to reinstate the coach; the Black leaders, educators, families, and students are now immersed in a context where there are daily reminders of the disregard for Black life. The permanence of antiblackness rests in its ability to reinstate white supremacist logics premised on Black demise. As such, this specific chain of events for Nolan becomes eerily and sufferably recognizable to the Black.

Relatedly, these principals highlight the immense cost of this disregard of their humanity. Each principal explains how they are required to navigate and outmaneuver contexts that are not welcoming to their leadership and are largely dismissive of Black humanity. Their leadership commitments are met with staunch resistance from white leaders, teachers, and community members. Hence, these leaders, whether through direct assaults or racialized isolation, incur psychological, emotional, community, and representational costs, which make their work largely unsustainable. These district contexts often act as boiler plates which, as Nolan explains, increases the pressure specifically for Black leaders; that is, contexts that are not prepared for Black leadership are more likely to intensify their scrutiny of these leaders. The immense pressure of being the only Black administrator coupled with white racialized resistance (e.g., white teachers organizing to push out the Black administrator) to support Black youth can derail the efforts of Black principals. As evidenced in this paper, these contexts can cause bewilderment, imposter syndrome, and eventually escape from the position, district, or profession.

Neoliberal hiring: unplanned failures in diversifying school districts

Black Crit is deeply suspicious of liberal/neoliberal multiculturalism and post-civil rights DEI initiatives and discourse because of their mis/treatment of Black life. Dumas and ross explain, “we want to recognize that the trouble with (liberal and neoliberal) multiculturalism and diversity, both ideology and practice, is that they are often positioned against the lives of Black people” (2016, p.430). That is, under these ideological perspectives, Black people remain the problem needing to be fixed, and their visions for self-determination are disregarded in favor of the market’s diversity priorities. As mentioned above, the mass displacement of Black professionals (i.e., teachers, principals), disregard for Black educational self-determination, and the destabilization of the Black middle class in post-Katrina New Orleans are prime examples of the problems of neoliberalism in education (Dixson et al., 2015). As evidenced in this scholarship, the school districts that these Black principals are working in fall victim to the same logics put forth by post-war desegregation reforms; that is, district workforce diversity takes precedence over Black humanity, well-being, and futurity (Dumas and ross, 2016) and remains a fixture in district reform and succession planning efforts. Put simply, Black leader hiring initiatives are severely undertheorized and do not deeply interrogate the readiness of white districts to support Black leadership; they flatly and erroneously presume that workforce diversity will solve the district’s issues regarding racism and other forms of oppression. Instead, as these principals discussed, racialized resistance and assaults on Black life have only made themselves more palpable. Instead, and given the ongoing containment of the aspiring Black principal, school districts could consider reframing “tapping” practices in non-reactionary ways that center the humanity, sustainability, and futurity of Black leaders over district representational goals.

Divining a vision for Black principalship futurity: implications

To close, I like to imagine, alongside the Black principals in this study, Black principal futures and the possibilities of Black principal sustainability. Specifically, I am inspired by BlackCrit’s notion of a liberatory fantasy to envision Black principals’ possibilities free from the oppressive backdrops that seek to contain them, their communities, and their pursuits. When asked about the future of Black principalship and what is needed to sustain Black principals, Serena, Nolan, Adrian, and Bobby offered the following key thematic responses: mentorship, affinity, and central office support. Relatedly, I offer recommendations for schools and districts to consider as they (hopefully) plan to hire Black principals. That said, I contradictorily and simultaneously reject the notion of recommendations given that their logics traditionally rely on state-sanctioned measures of “progress” and “success” that are confined by district and institutional logics and center the “equity or diversity needs” as defined by the state and district. Hence, I attempt to situate recommendations against Black backdrops, which may be in tension with traditional district initiatives.

Black principal mentorship

Each principal highlighted the importance of both internal and external mentorship as a mechanism that can sustain Black principalship. In response to my query about the future of the Black principalship, Nolan explained,

I think it should include access to coaching and mentorship outside of your district leadership structures…I still believe, despite people’s like best efforts and intentions, school systems are still fundamentally harmful…so for folks to be able to describe what they are experiencing and process what they are experiencing and not have to worry about alienating their cabinet-level colleague…I just think that’s important.

Nolan names the ways that white hegemony can compress and confine Black life within a white school district structure. Yet, Black mentorship outside of the district offers a hopeful escape from these oppressive conditions. Scholars have highlighted the importance of Black mentorship and ancestral guidance in education (Dixson and Dingus, 2008; Peters-Hawkins et al., 2018; Smith, 2021; Tillman, 2003). Mentorship and ancestral guidance offer a green book for Black principals; they reinstate and recenter Black imaginations and possibilities and situate the Black principal as the central figure in the self-determination of Black educational communities. Arguably, any subsequent imagination of Black principals’ futures should consider the rich legacies and possibilities of Black mentorship. School districts seeking to hire Black principals should be attentive to these support mechanisms.

In alignment with this call, I recommend that school districts planning to diversify their leadership hire intergenerational cohorts of Black administrators. District leaders must first recognize the ways that aspiring Black leaders are overlooked in hiring decisions; then, when seeking to “tap” a Black leader, districts should think about how to wrap the necessary supports around them for sustainability purposes. This effort should prioritize veteran, mid-career, and early-career Black principals to optimize opportunities for Black relational mentorship. As evidenced by Mosely’s (2018) discussion of the Black Teacher Project, multi-generational cohorts can offer aspiring and more novice Black educators space for additional guidance, support, and sustainment. For example, one experienced teacher in the study offered affirmation, comfort, and grace to a second-year teacher struggling to connect with their students (Mosely, 2018). Further, Black principals should be intentionally connected to retired Black principals who have worked in similar district contexts; in alignment with Black feminist perspectives, wisdom is a necessary component of navigating Black life. In these efforts, districts should compensate the leadership elders and the current Black administrators with time off, financial incentives, and material resources (e.g., space to convene). Regardless of the structure, this kind of mentorship must always focus on growth, affirmation, and imagining new possibilities.

Black principal affinity groups

Black educational communities tend to operate in communally bonded ways (see Morris, 2009); they (we) navigate the treacherous waters of school and district contexts collectively. As such, the Black principals reflected on their communities of support when imagining their sustainability in the principalship. Serena leans on her intersectional communities,

You have to be strategic and you have to have people, a community that you can talk to. I’ve got a sisterhood of other sisters who are in admin and we are able to share our challenges and not internalize it, because what breaks you is when you do not have that community and that space…you begin to feel like there’s something wrong with you and that you are the problem.

To mitigate the isolation, shared consciousness of social suffering, and costs of being Black in white spaces, these leaders identified communal supports that helped them unlearn imposed inferiority discourse(s). Mosely (2018) posits that racial affinity groups are essential structures in the sustainment of Black educators. Hence, I argue that the future of Black principalship could hinge on the authentic relational kinship of Black school leaders. Black principals need direct access to other Black leaders as a networked community to share and process their experiences. Further, districts should create space for Black communal dialogue and intentionally support Black-focused leadership professional development (see the Black Teacher Project and Black Principals Network). Beyond the contours of state and district confinement, Black principals must see themselves as part of a broader village of leaders committed to similar, liberatory educational pursuits. They must be synergized in ways that allow them to envision the possibilities of their leadership alongside Black communities.

Hence, I recommend that districts support ongoing professional development and collective healing opportunities specifically for Black principals in the district. Examples might include paid time off for conference travel, Black-centered professional development activities, and other opportunities for Black leaders to convene during and beyond school time. These convening opportunities should be designed and contoured by Black educational leaders’ imaginations of Black educational futures; they should center on Black possibilities, transgressions, and escape. These spaces must be carefully curated to allow for the fullness/intersections of Black life to create, inform, and/or resist the agenda; there must be room for refusal and resistance. Further, these opportunities should be financially supported by those with expressed commitments to sustaining Black leadership (i.e., white educational decision-makers).

Central office support of Black principals

Finally, leaders offered their thoughts on the ways that school districts should be thinking about Black principal sustainability in the wake of shifting socio-political climates and rapidly diversifying schools.

I think it is really important for our white systems leaders to understand how do I right now start leading from culturally responsive frames, even if I do not have leaders of color in my system right now? How do I start preparing for that?…and communities continue to diversify like there is going to be a need for that representation in your leadership. And, the best way to sustain that is to be a culturally responsive and affirming leader [now]….not starting to do that work once folks are already there (Nolan).

Thinking through Peters (2011) concept of leadership succession planning, this analysis calls attention to the reactionary nature of current school district systems to changing demographics and Black leadership. Specifically, these state systems are not equipped to engage in a praxis that critically interrogates the anti-Black social conditions experienced by Black people. As a result, Black leaders must endure, shield, and interrupt antiblackness upon their entry into the school; this practice exacerbates the racialized costs. The neoliberal multicultural frames that inform the hiring of Black principals is met with the dehumanizing antagonism of antiblackness, due in part to the failures of state systems (e.g., school districts) to attempt to, perhaps preemptively, interrupt deeply ingrained anti-Black sentiments, policies, and practices. Instead of informal, reactionary “tapping,” districts seeking to sustain Black educators and leaders must critically interrogate the conditions of their school communities, unpack the antiblackness that permeates the hallways, and be willing to center Black liberatory leadership visions as a praxis; these analyses should be central to a planning and sustaining elements of a dynamic succession plan that prioritizes Black principal humanity and sustainability.

That said, I recommend that central office leaders proactively support the critical professional (un)learning of antiblackness through formal and informal district-wide activities, such as equity audits, book studies, critical interrogations of whiteness/white supremacy, examining curricula, and anti-racist professional development; create the space and opportunities for liberation-minded Black people (e.g., youth, elders, educators) to directly inform the district and school-wide goals and direction of the district in all facets (e.g., equity, student support services, curricula and facilities, leadership succession); and institutionalize ongoing interrogations of antiblackness as a praxis that is engaged in regularly by practitioners and which holds them answerable to Black youth, families, and communities. For example, all teacher lesson plans and materials should be publicly available to specifically Black students, families, and other Black educators for opportunities of critique and improvement, and districts should consider what additional supports might be needed before hiring Black leaders.

Closing ruminations: what is succession planning for the black principal?

These four principals’ experiences suggest that the Black principalship in predominately and historically white districts can be challenging, even treacherous; the context and terrain can be littered with landmines premised on anti-Black social suffering and disregard. Yet, and despite the enduring and endemic nature of antiblackness (and therefore Black social suffering), these principals offer critical insight into how districts might reconsider hiring and workforce diversity initiatives. Specifically, district leaders must call into question the readiness of their respective educational communities for Black principalship. Has the district proactively prepared for Black leadership visions? Moreover, has the district prepared to unpack and process the antiblackness that is so often fundamental to the suburban, white school experience? To what extent do central office leaders recognize the barriers to/within the principalship for Black leaders? Until these logics are intentionally and consistently interrupted, the field will continue to chase the elusive goal of workforce diversity and, more specifically, Black principal sustainability. Nevertheless, because of these important dialogues, I remain hopeful about the future of the Black principal. I am hopeful because the Black principals in this study see themselves as the necessary architects for more liberatory Black educational futures. That is, they are clear on what they are fighting for despite impediments in front of them. I hope this scholarship activates district leaders’ commitments to centering Black principal humanity over undertheorized educator workforce diversity paradigms; this is the first step towards Black principal sustainability and countless other possibilities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, J. D. (1988). The education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Anfara, V. A., Brown, K. M., and Mangione, T. L. (2002). qualitative analysis on stage: making the research process more public. Educ. Res. 31, 28–38. doi: 10.3102/0013189X031007028

Armstrong, R. L. (2023). “I’m Not Your Superwoman”: How Black Women Principals Define and Mediate Self-Care. (Order No. 30788400) [Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University]. ProQuest Dissertations Global Publishing.

Arnold, N. W. (2014). Ordinary theologies: Religio-spirituality and the leadership of Black female principals. New york: Peter Lang.

Stanley, D. A. (2022). Blood, sweat, and tears: black women teacher’s organizational experiences in schools. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 35, 194–209. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2020.1828647

Stanley, D. A., and Gilzene, A. (2023). Listening, Engaging, Advocating and Partnering (L.E.A.P): A Model for Responsible Community Engagement for Educational Leaders. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 18, 253–276. doi: 10.1177/19427751221076409

Stanley, D. A. (Ed.). (2024). #Blackeducatorsmatter: The experiences of black teachers in an anti-black world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bailes, L. P., and Guthery, S. (2023). Disappearing diversity and the probability of hiring a non-white teacher: an analysis of principals’ hiring patterns in predominantly white schools. J. Educ. Human Resour. 41, 686–707. doi: 10.3138/jehr-2021-0033

Bass, L. (2012). When care trumps justice: the operationalization of Black feminist caring in educational leadership. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 25, 73–87. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2011.647721

Berry, R. R., and Reardon, R. M. (2022). Leadership Preparation and the Career Paths of Black Principals. Educ. Urban Soc. 54, 29–53. doi: 10.1177/00131245211001905

Bourdieu, P. (ed.). 1999. The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in Contemporary Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Brown, A. L., Dilworth, M. E., and Brown, K. D. (2018). Understanding the Black Teacher Through Metaphor. The Urban Review, 50, 284–299. doi: 10.1007/s11256-018-0451-3

Burton, B. A. (2023). Midwest Black, indigenous, people of color leaders serving in white Spaces. Alabama J. Educ. Leadersh. 10:143.

Carter, V. C. (2021). Diversifying Minnesota’s educator workforce: a series of research briefs. Comprehens. Center Netw., 1–17.

Chambers, T. V., Huggins, K. S., Locke, L. A., and Fowler, R. M. (2014). Between a “ROC” and a school place: the role of racial opportunity cost in the educational experiences of academically successful students of color. Educ. Stud. 50, 464–497. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2014.943891

Diamond, J. B., and Posey-Maddox, L. (2020). The changing terrain of the suburbs: examining race, class, and place in suburban schools and communities. Equity Excell. Educ. 53, 7–13. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2020.1758975

Dixson, A. D., Buras, K. L., and Jeffers, E. K. (2015). The color of reform: race, education reform, and charter schools in post-Katrina New Orleans. Qual. Inq. 21, 288–299. doi: 10.1177/1077800414557826

Dixson, A. D., and Dingus, J. E. (2008). In search of our mothers’ gardens: Black women teachers and professional socialization. Teach. College Rec. 110, 805–837. doi: 10.1177/016146810811000403

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. eds. A. G. McClurg & Co., Chicago, IL: The Floating Press.

Dumas, M. J. (2014). “Losing an arm”: schooling as a site of black suffering. Race Ethn. Educ. 17, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2013.850412

Dumas, M. J., and ross, K. M. (2016). Be real black for me: imagining blackcrit in education. Urban Educ. 51, 415–442. doi: 10.1177/0042085916628611

Esposito, J., and Evans-Winters, V. E. (2022). Introduction to intersectional qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.