- National Clinical Research Center for Metabolic Diseases, Key Laboratory of Diabetes Immunology (Central South University), Ministry of Education, and Department of Metabolism and Endocrinology, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

Introduction: Genome-wide association studies in Caucasians suggested an association between the acyl-CoA oxidase-like (ACOXL) gene and type 1 diabetes (T1D). We investigated if polymorphisms in ACOXL conferred susceptibility to T1D in Chinese and how they affected the clinical characteristics of T1D.

Methods: MassARRAY was performed in this case–control study to genotype rs4849165 and rs4849135 of ACOXL in a collection of 1,280 patients with T1D and 1,331 non-diabetic subjects.

Results: The minor allele C of rs4849165 was associated with an increased risk of T1D (P = 0.0013, OR 1.21). Moreover, individuals with the C/C genotype exhibited significantly lower postprandial C-peptide levels compared with T allele carriers (P = 0.0058, OR 1.76). The minor allele T of rs4849135 was associated with a decreased risk for T1D (P = 0.0098, OR 0.85) and a lower likelihood of having a low level of postprandial C-peptide (P = 0.0213, OR 0.78). Patients with G/T or T/T genotypes were more likely to be diagnosed during adulthood than those with G/G genotype (P = 0.0206, OR 0.77). No correlation with glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA), protein tyrosine phosphatase antibodies (IA-2A), or zinc transporter 8 antibodies (ZnT8A) could be reported here.

Discussion: Polymorphisms in ACOXL were associated with susceptibility to T1D in Chinese and showed associations with age at onset and beta-cell function. These loci, together with other genetic signals, may contribute to the development of risk models to identify genetically susceptible individuals in the Chinese population.

1 Introduction

In general, type 1 diabetes (T1D) is considered as a chronic disorder in which beta-cells of pancreatic islet are destroyed by autoimmune response, and susceptibility to the disease can be determined by both environmental and genetic factors (1). Besides the HLA complex explaining nearly half of genetic susceptibility to T1D (1), more than 80 non-HLA variants that add moderate risk for T1D individually have been revealed in prior genome-wide association studies (GWASs) and meta-analyses (2–4). Additionally, these genomic locations have already been applied to clinical use, as the genetic risk model consisting of 67 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) including both HLA and non-HLA information has proved its efficacy in discriminating subtypes of adult-onset diabetes and newborn screening (5).

Nevertheless, the associations with T1D mentioned above are primarily derived from Caucasian origin and cannot be simply extrapolated to other ethnic groups—for example, the HLA DR9 haplotype prevalent in patients from East Asia was seen at a considerably low frequency in Caucasians (6, 7). Furthermore, the C1858T of PTPN22 well known in Caucasian patients with T1D could rarely be found in Chinese (8). Therefore, the remarkable heterogeneity of T1D etiopathogenesis observed among multiple racial groups emphasizes the need to scrutinize the genetics of this disease in underrepresented populations. In terms of Chinese patients, only a few of the genetic variants have been classified as candidate genes for T1D, such as HLA region, CTLA4, PTPN22, STAT4, and ERBB3, while a large part of non-HLA genes susceptible to T1D in Caucasians remain unidentified in our population (7–11).

Members of the acyl-CoA oxidase family, such as ACOX1 and ACOX2, are ubiquitously expressed in human tissues, and their roles in peroxisomal β-oxidation have been well characterized (12). The protein encoded by acyl-CoA oxidase-like (ACOXL) gene is preferentially expressed in lung, parathyroid gland, urinary bladder, and male sex organs including testis and prostate (The Human Protein Atlas). The function of this protein remains poorly defined, though it is predicted to enable acyl-CoA oxidase activity, fatty acid binding activity, and the maintenance of lipid homeostasis (gene database of NCBI). Variants within ACOXL have been engaged in the etiology of various immune-related or metabolic disorders, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (13), alopecia areata (14), syndromic obesity, and type 2 diabetes (15, 16). Gene polymorphism rs4849135, an intron of ACOXL, was initially identified as related to T1D in Caucasians by a dense genotyping array, namely, the Immunochip (4). As far as previous publications are concerned, the role for this or other polymorphisms of ACOXL in the pathogenesis of T1D among non-Caucasian participants have not been verified so far.

The current research was thus conducted to investigate if polymorphisms in ACOXL conferred risk for T1D in Chinese and if these polymorphisms modified the clinical characteristics of T1D patients, including the positivity of islet autoantibodies, age at diagnosis as well as beta-cell function. In addition to the previously identified T1D risk locus rs4849135, we also selected rs4849165 for analysis. Rs4849165 is located in an intron of ACOXL, is not in linkage disequilibrium with rs4849135 (r2 <0.20 in the Asian population of the 1000 Genomes Project), and tags 132 SNPs of ACOXL. The inclusion of rs4849165 allowed us to capture broader genetic variation within ACOXL and to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of its potential role in the Chinese population.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study participants

A total of 1,280 T1D subjects were identified from the Department of Metabolism and Endocrinology in the Second Xiangya Hospital, and they were supposed to fulfill the following inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosed as diabetes under the criteria by WHO in 1999 and (2) acute disease manifestation and dependency of insulin administration upon diagnosis, (3) positive for at least one of the three autoantibodies against pancreatic islet: glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody (GADA), protein tyrosine phosphatase antibody (IA-2A) as well as zinc transporter 8 antibody (ZnT8A). A total of 1,331 healthy controls with normal glucose tolerance but without family history for diabetes were enrolled from the Department of Physical Examination in the Second Xiangya Hospital. All of the study participants declared themselves as of Chinese Han origin. The current research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. The participants or guardians of T1D children gave their written informed consent and were fully aware of the study process.

2.2 Biochemical assays and genotyping methods

Both fasting and postprandial C-peptide levels were determined with methods of chemiluminescence from Adiva Centaur Systemkit. Nearly 70% of the case subjects took this measurement within 12 months after disease onset, whereas the other patients were examined with a disease duration >12 months. Disease duration was included as a covariate in our analyses to account for the progressive decline of C-peptide after T1D onset. Radioligand assays in duplicate permitted the detection of autoantibodies against pancreatic islet, including GADA, IA-2A as well as ZnT8A. All T1D subjects took the examination of autoantibodies at disease onset, and positive results were further validated by a repetition to ensure that cases negative for all autoantibodies and those with ambiguous positivity were not recruited. MassARRAY (Sequenom, the US) was performed to genotype rs4849165 and rs4849135 in ACOXL followed by a quality control which achieved call rates of 99.8% and 99.5% for the two polymorphisms respectively.

2.3 Statistical analysis

All of the data were computed in SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, USA). We displayed continuous variables with normal distributions as mean ± standard deviation and compared them via Student’s t-test, whereas those exhibiting skewed distributions were expressed as median with interquartile range and compared using Mann–Whitney U-test. We showed categorical variables as n (%) and compared them using chi-square test, which also permitted the test for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Stepwise logistic regression was performed to compute all of the following analyses. When a dominant model was assumed, homozygotes of minor allele and heterozygotes were encoded as 1 and those homozygous for a major allele as 0. Under the assumption of recessive model, those homozygous for a minor allele were set as 1 and heterozygotes in combination with homozygotes of major allele as 0. In the additive model which calculated the impact for each copy of the minor allele, major allele homozygotes were defined as 0, heterozygotes as 1, and minor allele homozygotes as 2. All dominant, recessive, and additive models were adjusted for age to account for the mismatch between cases and controls. When interrogating the clinical relevance of ACOXL polymorphisms, outcome variables such as positivity of islet autoantibodies, early disease onset, and lower C-peptide levels were denoted as 1 and the negative results of islet autoantibodies, late T1D onset, and higher C-peptide concentrations as 0. For the analyses of C-peptide levels, disease duration was adjusted for in the logistic regression models.

3 Results

3.1 Sample description

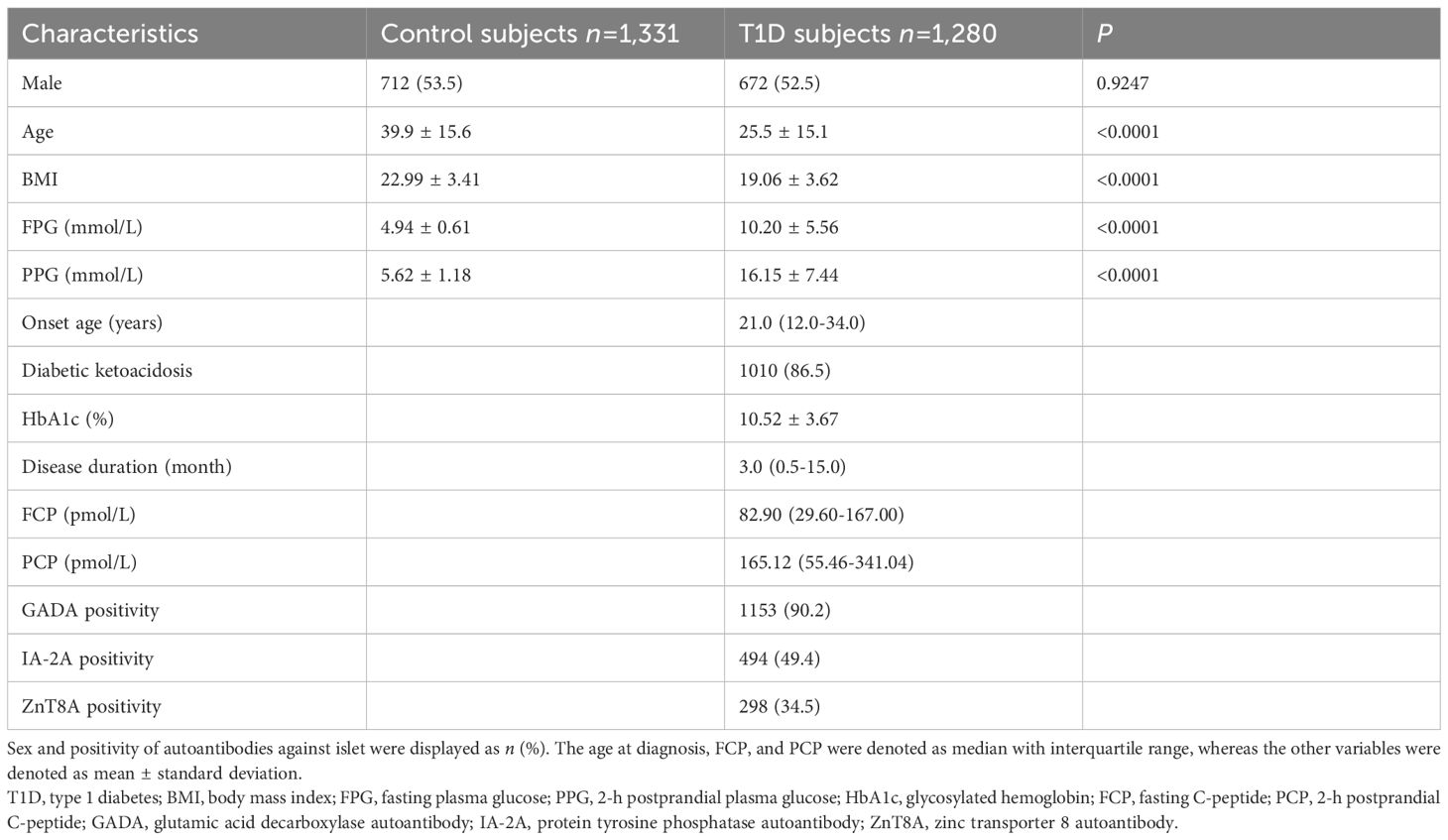

The demographics and clinical features of 1,280 T1D subjects and 1,331 healthy controls enrolled in this study are listed in Table 1. In brief, these two groups showed comparable proportions of male participants (P = 0.9247), while the T1D subjects were younger (P < 0.0001). Not surprisingly, patients with T1D appeared leaner (P < 0.0001) and exhibited remarkably higher concentrations of both fasting plasma glucose (P < 0.0001) and 2-h postprandial plasma glucose (P < 0.0001) in contrast to non-diabetic subjects. The median age at T1D diagnosis was 21.0 (12.0–34.0) years, and 1,010 patients (86.5%) presented diabetic ketoacidosis at disease onset. The T1D patients had an average HbA1c of 10.52% ± 3.67%, and their median fasting C-peptide and median postprandial C-peptide were 82.90 (29.60–167.00) pmol/L and 165.12 (55.46–341.04) pmol/L, respectively. Disease duration was recorded at the time of C-peptide measurement. At the occurrence of T1D, 90.2%, 49.4%, and 34.5% of patients tested positive for GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A, respectively.

3.2 Frequency distributions of genotypes and alleles

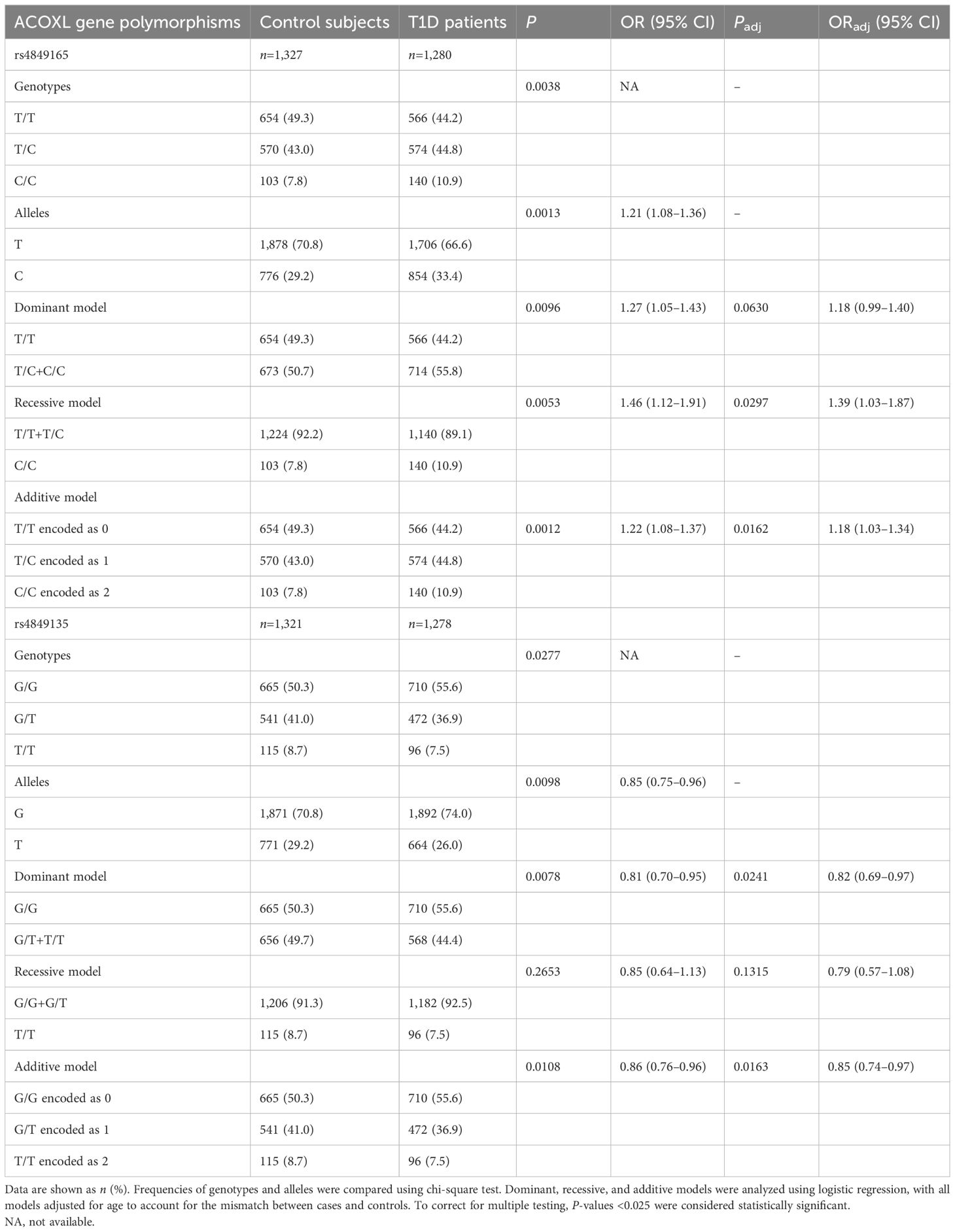

Neither the genotypes of rs4849165 (P = 0.7586 for T1D group and P = 0.1657 for control group) nor those of rs4849135 (P = 0.1560 for T1D group and P = 0.7391 for control group) showed a significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The genotypic and allelic frequency distributions of the two polymorphisms within ACOXL are listed in Table 2. As for rs4849165, a significantly different distribution of genotypes was seen between the two groups of participants (P = 0.0038) and the minor allele C increased risk for T1D (P = 0.0013, odds ratio [OR] 1.21, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–1.36). After adjusting for age, the association with T1D risk was best explained by an additive model, where the minor allele C conferred increased risk (Padj = 0.0162, ORadj 1.18, 95% CI 1.03–1.34). The initial associations observed in the dominant (Padj = 0.0630) and recessive models (Padj = 0.0297) were no longer statistically significant after age adjustment and correction for multiple testing.

Table 2. Genotypic and allelic frequency distributions of ACOXL gene polymorphisms between patients with T1D and healthy controls in a Chinese population.

In terms of rs4849135, the genotypic distribution of the T1D group marginally differed from that in the control group (P = 0.0277), the significance of which could not be sustained after correction for multiple testing. The minor allele T was associated with lower odds of T1D (P = 0.0098, OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75–0.96), and this effect remained significant after adjusting for age in both the additive model (Padj =0.0163, ORadj 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.97) and the dominant model (Padj = 0.0241, ORadj 0.82, 95% CI 0.69–0.97). Given the frequencies and OR of the minor alleles, the significance level of 0.05, and the sample size of 2,607, the power was 0.89 for rs4849165 and 0.77 for rs4849135, respectively.

3.3 Correlations between genotypes and phenotypes

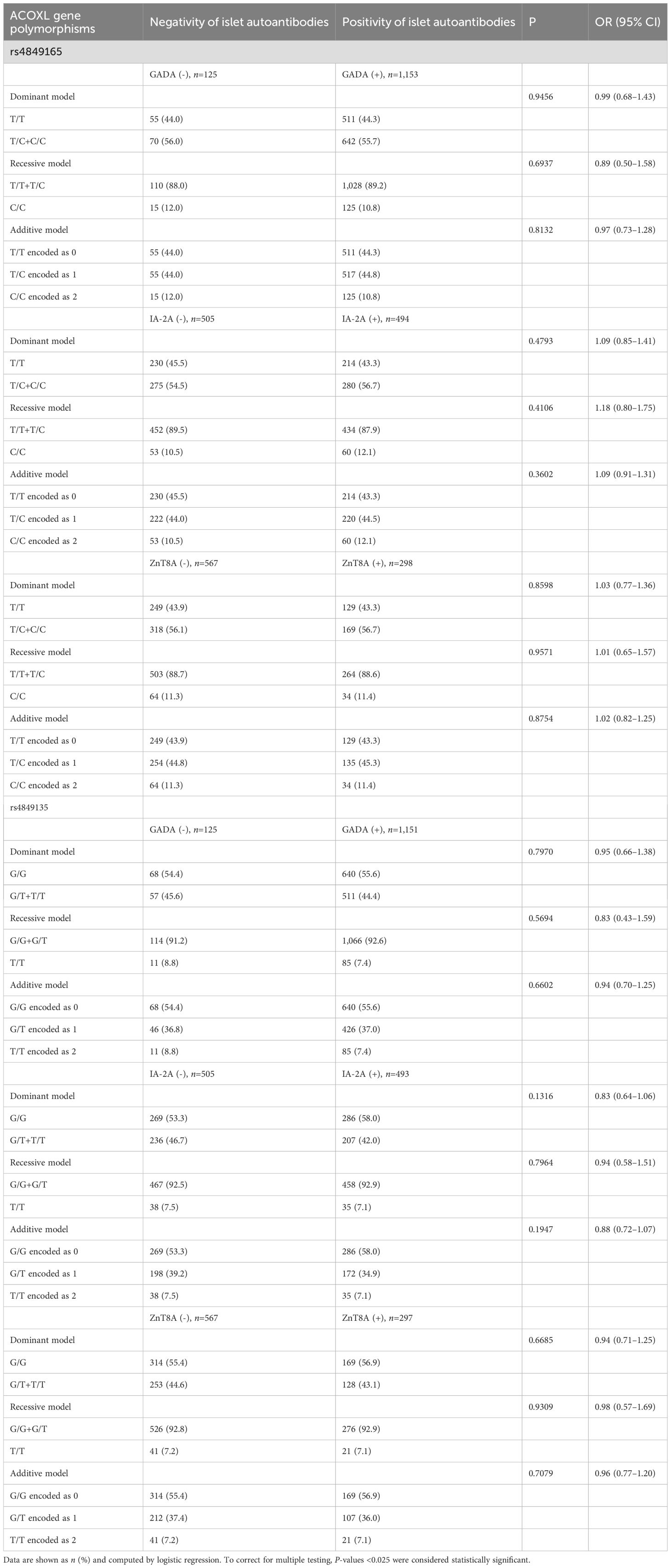

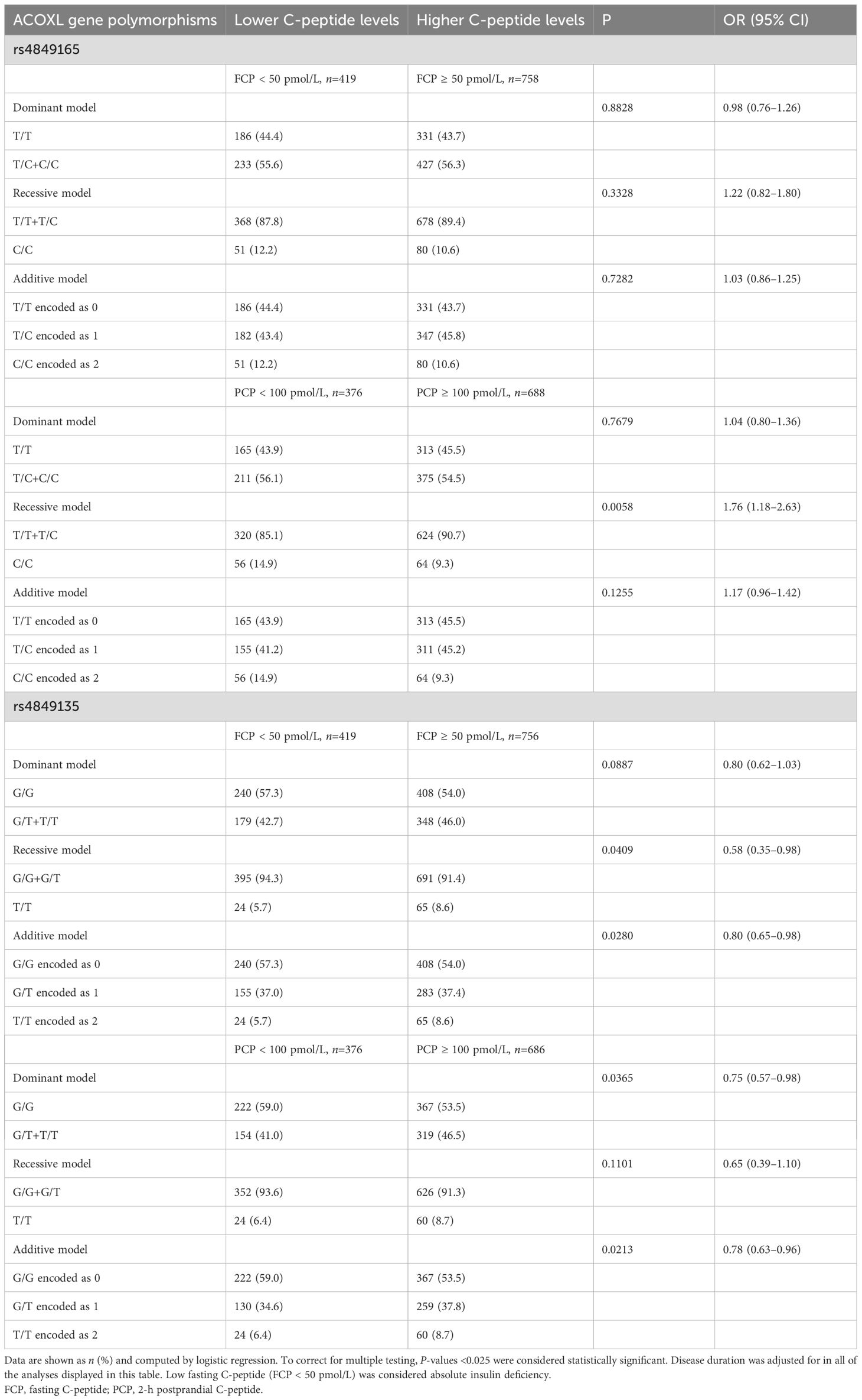

We went on to analyze the status of the three islet autoantibodies (Table 3), early or late disease onset (Table 4) as well as levels of C-peptide (Table 5) with information split by genotypes of ACOXL gene polymorphisms. Whichever genetic model selected, we reported no significant changes in autoantibody status, including GADA, IA-2A, and ZnT8A that could be attributed to the alteration in genotype frequency of rs4849165 or rs4849135 (shown in Table 3, all P-values >0.05).

Table 3. Islet autoantibodies’ status stratified by genotypes of ACOXL polymorphisms in Chinese patients with T1D.

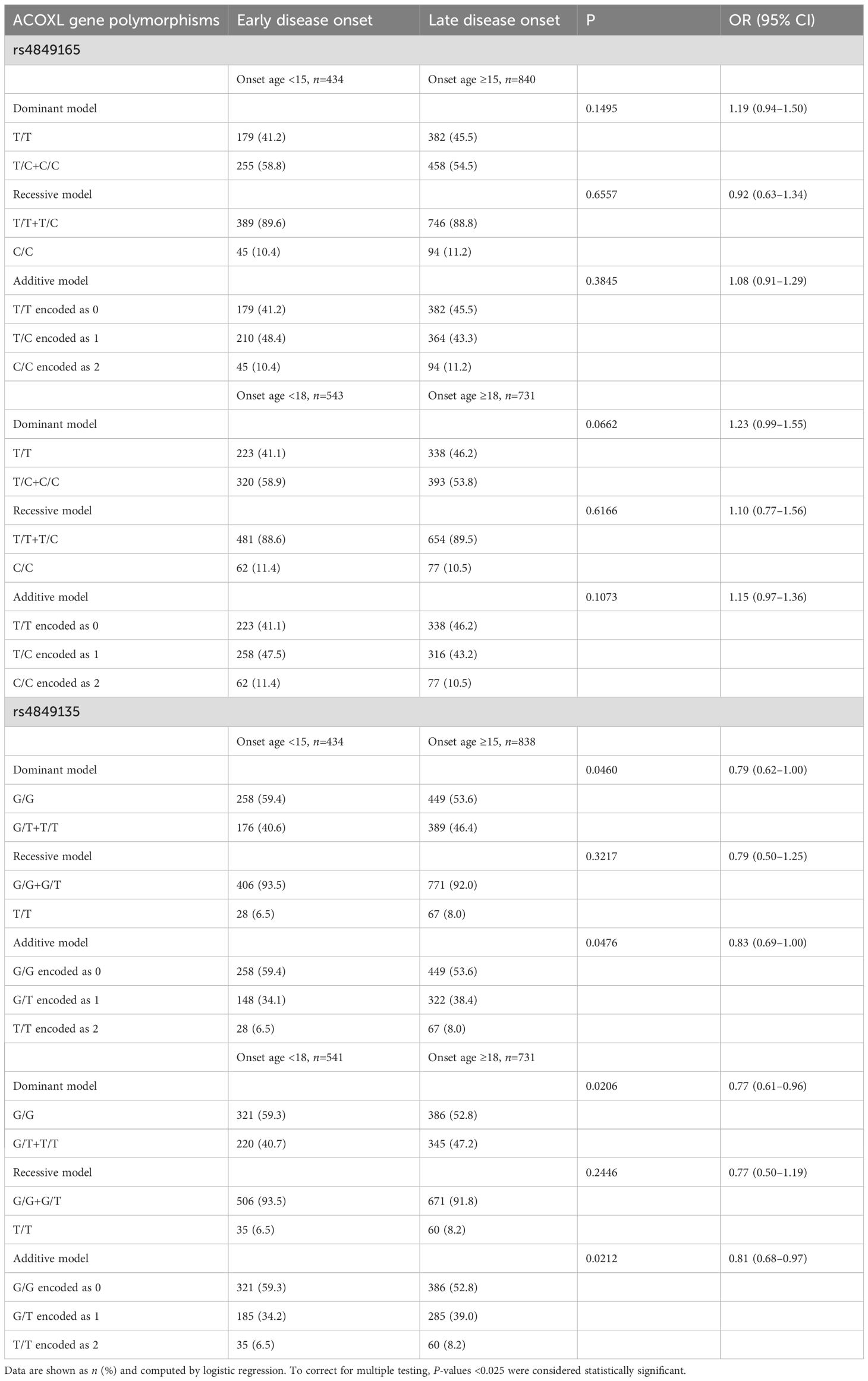

Table 4. Age at diagnosis stratified by genotypes of ACOXL polymorphisms in Chinese patients with T1D.

Table 5. C-peptide levels stratified by genotypes of ACOXL polymorphisms in Chinese patients with T1D.

As shown in Table 4, rs4849165 did not modify the age at T1D diagnosis, regardless of genetic models assumed or the cutoff value of onset age selected (all P-values >0.05 for rs4849165). When T1D subjects were classified as either those with childhood onset (1–14 years) or those without (>15 years), the T allele of rs4849135 was marginally related to late disease onset (additive model, P = 0.0476, OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–1.00), and a slightly higher frequency of late onset was observed in T allele carriers in relation to homozygotes of G (68.8% vs. 63.5% in the dominant model, P = 0.0460, OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.62–1.00). Both associations lost their significance after Bonferroni correction. However, when the cutoff point for onset age was set as 18 years, the T allele of rs4849135 was significantly associated with adult onset of T1D (additive model, P = 0.0212, OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68–0.97), and a markedly higher percentage of adult onset was found in patients with G/T or T/T genotypes than those with G/G genotype (61.1% vs. 54.6% in the dominant model, P = 0.0206, OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61–0.96). In the recessive model, similar proportions of late disease onset were seen in homozygotes of minor allele T and those with major allele G (P = 0.2446).

When both postprandial C-peptide and fasting C-peptide were measured to evaluate the beta-cell function of T1D patients and the adjustment for disease duration was made (Table 5), individuals carrying C/C genotypes of rs4849165 were more likely to have low levels of postprandial C-peptide (PCP) compared with T allele carriers (46.7% vs. 33.9% in recessive model, P = 0.0058, OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.18–2.63). The detrimental effect of rs4849165 on beta-cell function was not seen in the association analysis of fasting C-peptide (FCP) (P >0.05 for all of the three models). Regarding rs4849135, the T allele was associated with a lower likelihood of low FCP levels (additive model, P = 0.0280, OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98), and patients with T/T genotype were at a slightly lower risk for absolute insulin deficiency (FCP <50 pmol/L) compared to those carrying G allele (27.0% vs. 36.4% in the recessive model, P = 0.0409, OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.38–0.98). The T allele significantly decreased the risk for failure of beta-cell function (PCP < 100 pmol/L) in the additive model (P = 0.0213, OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.63–0.96), whereas a slightly smaller proportion of patients with T allele had failure of beta-cell function compared to those homozygous for G allele (dominant model, P = 0.0365, OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.98). Nonetheless, the T/T genotype was not significantly associated with PCP in contrast to G/G plus G/T genotype (recessive model, P = 0.1101).

4 Discussion

As a supplement for the previously identified T1D-susceptible loci in Chinese like HLA complex, CTLA4, PTPN22, STAT4, and ERBB3, the first GWAS in this population has revealed GATA3, BTN3A1, and SUOX as additional genetic markers for T1D (17). However, the number of risk loci confirmed so far in Chinese patients with T1D is barely comparable to that in Caucasians, and several barriers have been in our way to pursue extra determinants of disease susceptibility. The first issue to be settled when handling genes with moderate effect sizes is a sufficiently large sample capacity to ensure statistical power. Second, as Chinese population is comprised of various ethnicities and certain ethnic minorities are genetically similar to Europeans instead of Han (18), findings generated from an admixed population can be confusing. Third, given that T1D may occur at any age and that the majority of new-onset T1D subjects in China are diagnosed during adulthood (19), we cannot obtain a full view of genetic architecture using data from studies restricted to childhood-onset T1D. Therefore, the considerably large collection of both T1D subjects and non-diabetic controls covering all age groups from genetically homogeneous Han population has enabled us to decipher the impact of ACOXL polymorphisms on T1D susceptibility in Chinese.

Though the genotype distribution of rs4849135 did not show a significant difference between the two groups (Table 2), the T allele did reduce the risk for T1D with an OR of 0.85, which was compatible with the result (OR 0.89) in GWASs conducted among Caucasians (4). In the dominant model, carrying the T allele was associated with lower odds of T1D compared with homozygotes of G allele. It was notable that in the recessive model, two copies of the T allele were not significantly associated with lower odds compared with individuals carrying 0–1 copy of the T allele, which could probably be explained by the mixture of the higher-risk G/G genotype with the lower-risk G/T genotype as well as the relatively low frequency of the T/T genotype observed in this population. These findings suggest that the ACOXL gene variant rs4849135 may be associated with T1D susceptibility, consistent with the findings reported in the ImmunoChip study. However, as no direct functional evidence exists, its role in T1D requires further investigation. Concerning rs4849165, after adjusting for age, the association with T1D was best explained by an additive model, suggesting a dose-dependent effect of the minor allele C. While the unadjusted analysis initially suggested a particularly strong effect for the homozygous C/C genotype, this was not statistically significant in the recessive model after accounting for age as a confounder.

The advent of overt T1D is usually preceded by the appearance of autoantibodies against islet (1). HLA complex and non-HLA loci both modify the specificity of the antibody setting in motion autoimmune process, namely, IAA or GADA as the first antibody to appear (20, 21). Before the diagnosis of classic T1D in our department, the patients were routinely tested for the three autoantibodies against islet. Nevertheless, neither of the two ACOXL gene polymorphisms showed a correlation with GADA, IA-2A, or ZnT8A no matter which genetic model was tested. Quite a number of genetic association studies in Caucasian patients with T1D are conducted in those with childhood onset, i.e., diagnosed between 1 and 14 years of age whereas the prevalence of adulthood-onset (≥18 years) T1D in Chinese should be worthy of note. We went on to separate the T1D participants into either group of early onset or those with late onset based on the two thresholds discussed above. It was found that patients carrying the T allele of rs4849135 were more frequently diagnosed at age ≥18 years than those with G/G genotype, which could at least explain in part why T1D with adulthood onset is relatively common in Chinese. On the other hand, rs4849165 did not appear to be a modulator of onset age for T1D in this population. We next sought to determine if the allelic variants of ACOXL had any impact on the beta-cell function of patients, for whom both FCP and PCP levels were measured. A previous study on the declining pattern of beta-cell function in Chinese patients with T1D defined both FCP <50 pmol/L and 2-h PCP <100 pmol/L as failure of beta-cell function (22). We paid particular attention to beta-cell failure which was unfavorable for the control of both hyperglycemia and complications and adopted the two cutoff values above to categorize patients of the current dataset. As a result, patients with the T1D-permissive C/C genotype of rs4849165 were more likely to experience failure of beta-cell function (PCP <100 pmol/L) compared with those carrying T/T or T/C genotype. In contrast, the T allele of rs4849135 was associated with a lower likelihood of beta-cell function failure compared with the G allele. Although we could not find data from other populations to substantiate the relationship between ACOXL and the C-peptide levels of T1D patients, increasing evidence was collected from multiple ethnicities to support the regulatory role of non-HLA SNPs such as vitamin D receptor gene, PTPN22, and FCRL3 on the beta-cell function of subjects with T1D (23, 24). The main limitation of this research was that only cross-sectional profiles of patients such as autoantibody status and C-peptide concentrations could be presented here. The control group was not screened for islet autoantibodies; therefore, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that some individuals were in the preclinical stage of T1D. We were unable to figure out whether ACOXL polymorphisms alone or coupled with other risk loci could predict seroconversion to positivity of islet autoantibodies, progression to overt T1D, or the rapid decay of beta-cell function in Chinese. An additional limitation is that the exact timing of C-peptide measurement was not uniformly available; however, we included disease duration as a covariate in our analyses, which reduces the likelihood of bias due to the differential decline of C-peptide levels over time (25).

Aside from its association with T1D in Caucasian and in the Chinese population described here, genetic variants within ACOXL have also been involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases probably ascribed to either aberrant immunity or metabolic disorder. Alopecia areata was another autoimmune disease with evident genetic predisposition. Researchers from Columbia University integrated the data of two genome-wide association studies on alopecia areata and uncovered ACOXL rs3789129 reaching statistical significance, the association strength of which was second only to the HLA complex (14). Chronic lymphocytic leukemia was a malignancy of B lymphocyte encompassing a pronounced familial component. A meta-analysis exploited the genome-wide information of 2,343 European cases and 2,854 controls from 22 studies and identified nine new susceptibility loci including ACOXL rs13401811 for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (13). Since only a few of type 2 diabetes-related SNPs initially identified in populations of European ancestry could be replicated in African American which harbored a high genetic diversity, the GENNID Study Group managed to perform a linkage analysis utilizing the genotypes of 9,203 SNPs and established the association of 24 novel candidate loci such as ACOXL rs7583450 with type 2 diabetes in the African American subgroup (15). Additionally, syndromic obesity was defined by obesity with at least one other criterion like intellectual disability, facial dysmorphism, or congenital malformations. Vuillaume ML and her colleagues identified a list of new candidate loci in a cohort of 100 French children presented with syndromic obesity, and a vital branch of these genomic locations, e.g., ACOXL, was believed to engage in lipid metabolism (16). With a growing body of evidence gathered from epidemiological studies favoring the correlation between obesity and the risk for asthma, Zhu Z and his colleagues conducted a cross-trait GWAS enrolling 457,822 European participants from the UK Biobank in order to determine the shared genetic components between metabolic traits and subtypes of asthma. Consequently, ACOXL rs72836344 was found to be an overlapping variant between late-onset asthma and BMI (26). In this context, one might conceive that ACOXL could serve as a bridge between immunity and metabolism.

Research on ACOXL included but were not limited to genetic association studies and could be extended to the field of clinical relevance like treatment and prognosis for malignancies. Lipid metabolism was fundamental for the progression and metastasis of tumor. Jiang A and his colleagues developed a prognostic index for early-stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma according to the expression levels of six lipid metabolism-related genes, including ANGPTL4, NPAS2, SLCO1B3, ACOXL, ALOX15, and B3GALNT1. Patients with a higher prognostic index tended to have poorer overall survival and respond better to immune checkpoint inhibitors (27). Dong Y and his colleagues found that the transcriptomics of genes related to fatty acid metabolism such as ACOXL was valuable for classifying cutaneous melanoma into either hot or cold tumors, which showed distinct response rates for immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors (28). Additionally, Pontén F et al. carried out a proteomic analysis of human prostate and disclosed the potential of TMEM79 and ACOXL proteins to distinguish between benign and malignant prostatic tissues (29). In a recent study, Japanese scholars analyzed publicly available data of ChIP-Seq in various mouse tissues and discovered a T cell-specific enhancer-like region which was localized within the 9th intron of ACOXL, at around 200 kb upstream of Bim and at nearly 90 kb upstream of Bub1. This cis-regulatory enhancer was thus termed EBAB (Bub1-Acoxl-Bim). In EBAB knockout mice, thymocytes harboring TCR with high affinity toward self-antigen were defective in apoptosis, which could be attributed to the insufficient expression of Bim. T cells which strongly recognized self-peptide and evaded negative selection in the thymus could subsequently result in autoimmunity (30). Their findings laid the groundwork for mechanistic studies on how changes in ACOXL could trigger autoimmune process in mice. These observations raise the possibility that ACOXL may influence immune tolerance through enhancer-mediated regulation of thymocyte apoptosis and negative selection, thereby indirectly affecting autoimmunity. In addition, given the reported associations of ACOXL variants with metabolic traits such as type 2 diabetes, obesity, and asthma, it is also possible that ACOXL polymorphisms contribute to T1D by modulating the pathways of lipid metabolism that secondarily impact beta-cell function. While these findings highlight the potential roles of ACOXL in immunity and metabolism, important limitations should be noted. ACOXL is primarily a peroxisomal fatty acid β-oxidation enzyme with limited expression in immune tissues and the pancreas, and there is no functional evidence supporting its causal role in autoimmunity. Therefore, the observed associations may reflect linkage disequilibrium with truly causal variants at the 2q13 locus rather than direct functional effects of ACOXL. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes causal inference, and independent longitudinal studies are needed to validate our findings. Although all participants were Han Chinese, we cannot completely rule out regional genetic heterogeneity within this population. To mitigate this potential bias, recruitment was restricted to a single tertiary hospital in Hunan Province, which ensured a relatively homogeneous cohort. However, this strategy may also limit the generalizability of our findings to broader Chinese populations. Finally, environmental exposures known to influence T1D risk, such as viral infections and dietary factors, were not assessed in this study.

Our findings suggest that ACOXL variants may contribute not only to T1D susceptibility but also to clinical heterogeneity such as age at onset and beta-cell function in Chinese patients. These results raise the possibility that genes beyond classical immune pathways, including those involved in lipid metabolism, may modulate T1D pathogenesis and provide a basis for future mechanistic studies. Collectively, the data presented here have, for the first time, established the role of ACOXL gene polymorphisms in susceptibility to and the clinical features of T1D among the Chinese population. Whether these polymorphisms in combination with other genetic variants identified in this population can aid in the recognition of individuals genetically prone to T1D, the appearance of islet autoantibodies with distinct specificities and the development of full-blown T1D or rapid progressors to failure of beta-cell function should be a topic of interest for future studies with a longitudinal design.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YX: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. ZX: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XL: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. GH: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JH: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81820108007, 82200933), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (2021zzts0381), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JC0003), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2024RC3054).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the doctors, nurses, and case and control individuals for their devotion to this investigation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ilonen J, Lempainen J, and Veijola R. The heterogeneous pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:635–50. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0254-y

2. Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Smiles AM, Plagnol V, Walker NM, Allen JE, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association study data identifies additional type 1 diabetes risk loci. Nat Genet. (2008) 40:1399–401. doi: 10.1038/ng.249

3. Ortega HI, Udler MS, Gloyn AL, and Sharp SA. Diabetes mellitus polygenic risk scores: heterogeneity and clinical translation. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2025) 21:530–45. doi: 10.1038/s41574-025-01132-w

4. Onengut-Gumuscu S, Chen WM, Burren O, Cooper NJ, Quinlan AR, Mychaleckyj JC, et al. Fine mapping of type 1 diabetes susceptibility loci and evidence for colocalization of causal variants with lymphoid gene enhancers. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:381–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3245

5. Sharp SA, Rich SS, Wood AR, Jones SE, Beaumont RN, Harrison JW, et al. Development and standardization of an improved type 1 diabetes genetic risk score for use in newborn screening and incident diagnosis. Diabetes Care. (2019) 42:200–7. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1785

6. Erlich H, Valdes AM, Noble J, Carlson JA, Varney M, Concannon P, et al. HLA DR-DQ haplotypes and genotypes and type 1 diabetes risk: analysis of the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium families. Diabetes. (2008) 57:1084–92. doi: 10.2337/db07-1331

7. Luo S, Lin J, Xie Z, Xiang Y, Zheng P, Huang G, et al. HLA genetic discrepancy between latent autoimmune diabetes in adults and type 1 diabetes: LADA China study no. 6. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 101:1693–700. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3771

8. Pei Z, Chen X, Sun C, Du H, Wei H, Song W, et al. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism in the protein tyrosine phosphatase N22 gene (PTPN22) is associated with Type 1 diabetes in a Chinese population. Diabetes Med. (2014) 31:219–26. doi: 10.1111/dme.12331

9. Jin P, Xiang B, Huang G, and Zhou Z. The association of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 + 49A/G and CT60 polymorphisms with type 1 diabetes and latent autoimmune diabetes in Chinese adults. J endocrinological Invest. (2015) 38:149–54. doi: 10.1007/s40618-014-0162-x

10. Bi C, Li B, Cheng Z, Hu Y, Fang Z, and Zhai A. Association study of STAT4 polymorphisms and type 1 diabetes in Northeastern Chinese Han population. Tissue Antigens. (2013) 81:137–40. doi: 10.1111/tan.12057

11. Sun C, Wei H, Chen X, Zhao Z, Du H, Song W, et al. ERBB3-rs2292239 as primary type 1 diabetes association locus among non-HLA genes in Chinese. Meta gene. (2016) 9:120–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2016.05.003

12. Van Veldhoven PP. Biochemistry and genetics of inherited disorders of peroxisomal fatty acid metabolism. J Lipid Res. (2010) 51:2863–95. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R005959

13. Berndt SI, Skibola CF, Joseph V, Camp NJ, Nieters A, Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Genet. (2013) 45:868–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.2652

14. Betz RC, Petukhova L, Ripke S, Huang H, Menelaou A, Redler S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis in alopecia areata resolves HLA associations and reveals two new susceptibility loci. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:5966. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6966

15. Hasstedt SJ, Highland HM, Elbein SC, Hanis CL, and Das SK. Five linkage regions each harbor multiple type 2 diabetes genes in the African American subset of the GENNID Study. J Hum Genet. (2013) 58:378–83. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.21

16. Vuillaume ML, Naudion S, Banneau G, Diene G, Cartault A, Cailley D, et al. New candidate loci identified by array-CGH in a cohort of 100 children presenting with syndromic obesity. Am J Med Genet Part A. (2014) 164a:1965–75. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36587

17. Zhu M, Xu K, Chen Y, Gu Y, Zhang M, Luo F, et al. Identification of novel T1D risk loci and their association with age and islet function at diagnosis in autoantibody-positive T1D individuals: based on a two-stage genome-wide association study. Diabetes Care. (2019) 42:1414–21. doi: 10.2337/dc18-2023

18. Liu S, Huang S, Chen F, Zhao L, Yuan Y, Francis SS, et al. Genomic analyses from non-invasive prenatal testing reveal genetic associations, patterns of viral infections, and Chinese population history. Cell. (2018) 175:347–59.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.016

19. Weng J, Zhou Z, Guo L, Zhu D, Ji L, Luo X, et al. Incidence of type 1 diabetes in China, 2010-13: population based study. BMJ. (2018) 360:j5295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5295

20. Lempainen J, Laine AP, Hammais A, Toppari J, Simell O, Veijola R, et al. Non-HLA gene effects on the disease process of type 1 diabetes: From HLA susceptibility to overt disease. J Autoimmun. (2015) 61:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.05.005

21. Ilonen J, Hammais A, Laine AP, Lempainen J, Vaarala O, Veijola R, et al. Patterns of β-cell autoantibody appearance and genetic associations during the first years of life. Diabetes. (2013) 62:3636–40. doi: 10.2337/db13-0300

22. Li X, Cheng J, Huang G, Luo S, and Zhou Z. Tapering decay of β-cell function in Chinese patients with autoimmune type 1 diabetes: A four-year prospective study. J Diabetes. (2019) 11:802–8. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12907

23. Habibian N, Amoli MM, Abbasi F, Rabbani A, Alipour A, Sayarifard F, et al. Role of vitamin D and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms on residual beta cell function in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol reports: PR. (2019) 71:282–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2018.12.012

24. Pawłowicz M, Filipów R, Krzykowski G, Stanisławska-SaChadyn A, Morzuch L, Kulczycka J, et al. Coincidence of PTPN22 c.1858CC and FCRL3 -169CC genotypes as a biomarker of preserved residual β-cell function in children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. (2017) 18:696–705. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12429

25. Ludvigsson J, Carlsson A, Deli A, Forsander G, Ivarsson SA, Kockum I, et al. Decline of C-peptide during the first year after diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabetes Res Clin practice. (2013) 100:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.03.003

26. Zhu Z, Guo Y, Shi H, Liu CL, Panganiban RA, Chung W, et al. Shared genetic and experimental links between obesity-related traits and asthma subtypes in UK Biobank. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 145:537–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.035

27. Jiang A, Chen X, Zheng H, Liu N, Ding Q, Li Y, et al. Lipid metabolism-related gene prognostic index (LMRGPI) reveals distinct prognosis and treatment patterns for patients with early-stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Int J Med Sci. (2022) 19:711–28. doi: 10.7150/ijms.71267

28. Dong Y, Zhao Z, Simayi M, Chen C, Xu Z, Lv D, et al. Transcriptome profiles of fatty acid metabolism-related genes and immune infiltrates identify hot tumors for immunotherapy in cutaneous melanoma. Front Genet. (2022) 13:860067. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.860067

29. O’Hurley G, Busch C, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Stadler C, Tolf A, et al. Analysis of the human prostate-specific proteome defined by transcriptomics and antibody-based profiling identifies TMEM79 and ACOXL as two putative, diagnostic markers in prostate cancer. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0133449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133449

Keywords: Chinese, type 1 diabetes, genetics, ACOXL, SNP

Citation: Liu J, Xia Y, Xie Z, Li X, Huang G, Hu J and Zhou Z (2025) Association of acyl-CoA oxidase-like gene polymorphisms with risk, onset age, and beta-cell function of type 1 diabetes in Chinese. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1551159. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1551159

Received: 24 December 2024; Accepted: 04 September 2025;

Published: 25 September 2025.

Edited by:

Humberto Garcia-Ortiz, National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), MexicoReviewed by:

Cong-Yi Wang, Tongji Medical College, ChinaJosé Rafael Villafan Bernal, National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Xia, Xie, Li, Huang, Hu and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiguang Zhou, emhvdXpoaWd1YW5nQGNzdS5lZHUuY24=; Jingyi Hu, aHVqaW5neWkwMDY2QGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

‡ORCID: Zhiguang Zhou, orcid.org/0000-0002-0374-1838

Jinhan Liu

Jinhan Liu Ying Xia

Ying Xia Zhiguo Xie

Zhiguo Xie Xia Li

Xia Li Gan Huang

Gan Huang Jingyi Hu

Jingyi Hu Zhiguang Zhou

Zhiguang Zhou