- 1Department of Clinical Laboratory, Institute of Translational Medicine, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei, China

- 2Shenzhen Key Laboratory for Reproductive Immunology of Peri-implantation, Shenzhen Zhongshan Institute for Reproductive Medicine and Genetics, Shenzhen Zhongshan Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital (Formerly Shenzhen Zhongshan Urology Hospital), Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrine-metabolic disorder syndrome, that predominantly affects women of reproductive age. It is characterized by marked clinical heterogeneity involving multiple systems including reproductive, metabolic and immune systems, while existing diagnostic protocols remain inadequate for clinical needs. Moreover, the incomplete understanding of PCOS etiology has limited therapeutic strategies for symptomatic management rather than interventions targeting core pathological mechanisms, resulting in PCOS frequently persisting as a chronic condition with an increased risk of long-term complications such as type 2 diabetes, metabolic disorder-associated fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease. This clinical reality underscores the urgent need to elucidate its pathogenic network at the molecular level. Emerging evidence suggests that the Hippo signaling pathway plays a central role in the pathological process of PCOS through dynamically regulating cell proliferation-apoptosis balance, differentiation programs and metabolic homeostasis. This review examines the molecular mechanisms governing Hippo signaling transduction and its physiological relevance, with a focused analysis of its diverse implications in PCOS pathophysiology, particularly in reproductive dysfunction, metabolic-endocrine disturbances, and immune dysregulation. These mechanistic insights not only advance our understanding of PCOS pathogenesis but also provide a theoretical foundation for developing signaling pathway-targeted precision therapies.

1 Introduction

PCOS, also known as Stein-Leventhal syndrome, is a complex endocrine-metabolic disorder affecting approximately 11-13% of reproductive-aged women globally (1). This condition is clinically characterized by impaired fertility, metabolic disorders and immune microenvironment dysregulation. Notably, current therapeutic interventions remain challenging, with patients facing significant risks of comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (2). Furthermore, as a multisystem disorder involving reproductive, metabolic and immune interactions, systematic elucidation of PCOS pathogenesis holds critical implications for advancing clinical diagnosis and treatment strategies.

The Hippo signaling pathway, an evolutionarily conserved regulatory network, derives its name from the tissue hyperproliferation phenotype observed in Drosophila melanogaster with Hippo kinase mutations (3, 4). This pathway governs several biological processes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and tissue homeostasis through phosphorylation cascades (5). Remarkably, the Hippo signaling pathway has multidimensional regulatory functions. In the female reproductive system, it regulates follicular developmental homeostasis, while its functional dysregulation is strongly associated with reproductive-endocrine disorders, such as PCOS and premature ovarian insufficiency (6–9). In addition, this pathway can also coordinate systemic metabolism by interfering with metabolites and/or metabolic signaling, as well as modulate immune microenvironment homeostasis through its involvement in immune cell differentiation and inflammatory cytokine secretion (10, 11).

As early as 2012, Li et al. identified the Hippo signaling pathway core effector YAP1 as a susceptibility gene for PCOS through genome-wide association study (GWAS) analysis (12). Subsequent advancements in research methodologies have established that Hippo signaling dysregulation contributes to PCOS pathogenesis via aberrant androgen biosynthesis, granulosa cell cycle disruption, and impaired folliculogenesis (13). However, given the multisystem complexity of PCOS, the mechanistic studies need to break through the traditional single-system analysis framework and conduct comprehensive analysis from a holistic perspective. As evidenced by extensive literature reviews, current research on the Hippo-PCOS relationship remains limited. This review summarizes and discusses the roles of the Hippo signaling pathway and its key components in reproductive, metabolic and immune regulation, elucidating its molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications in PCOS. By emphasizing the cross-system regulatory properties of the pathway, this work aims to inspire researchers to explore novel insights into PCOS pathogenesis and therapeutic targets.

2 Search methods

To ensure a comprehensive review of the literature, a systematic search was performed using the PubMed, Medline, and Embase databases for relevant articles published between 2010 and 2025. The search used a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to “polycystic ovary syndrome”, “infertility”, “ovarian follicular development”, “ovarian microenvironment”, “lipid metabolism”, “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease/MASLD”, “insulin resistance”, “hyperandrogenemia”, “adipose tissue”, “inflammation”, “macrophages”, and “Hippo signaling pathway” (including YAP/TAZ, MST1/2 and LATS1/2). The scope of the search encompassed original research (observational, epidemiological and experimental), reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. The inclusion criteria were limited to English-language articles presenting original data or seminal reviews, prioritizing those published in peer-reviewed journals with an emphasis on recent evidence. Additional information was obtained from references cited in the articles resulting from the literature search.

3 Results

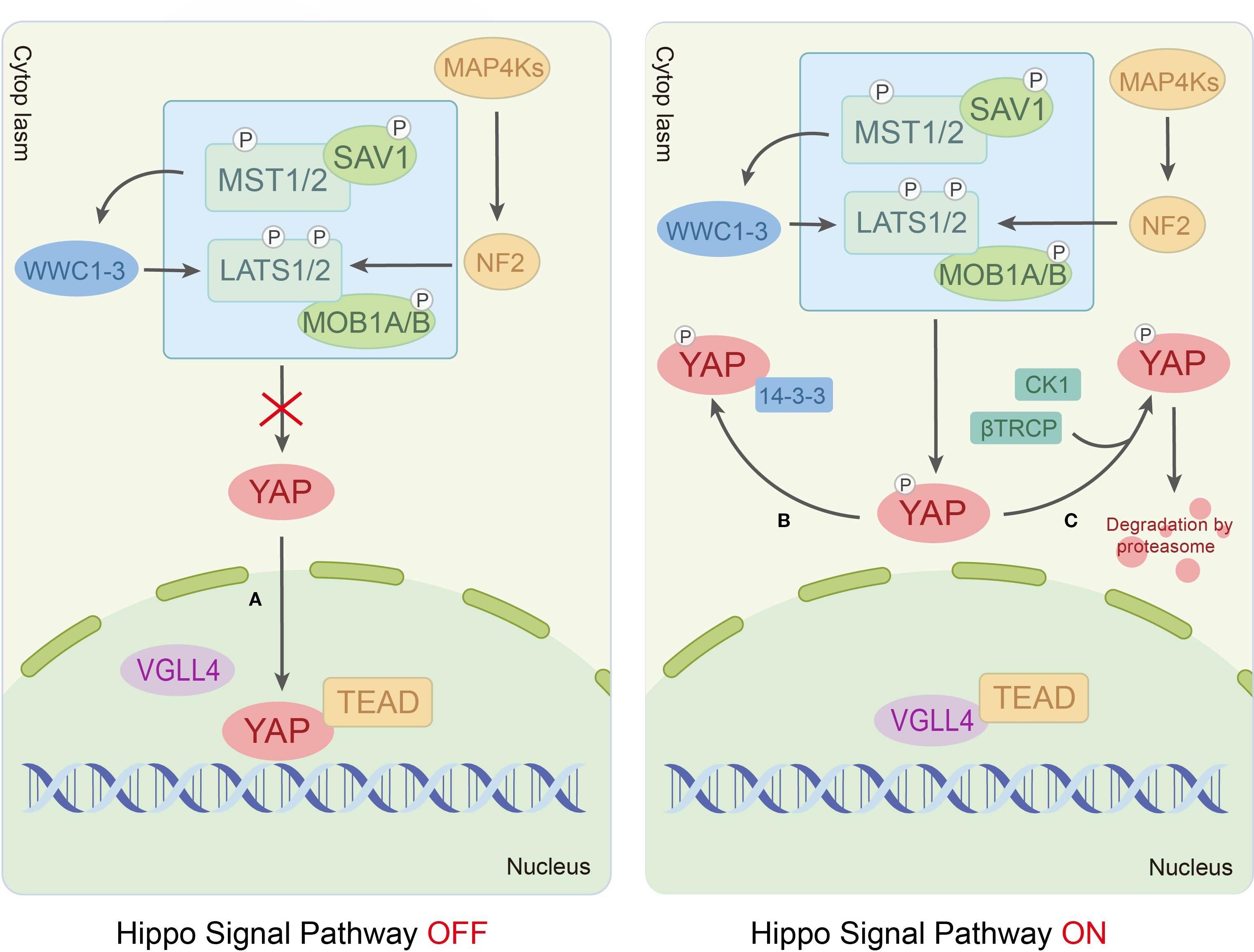

3.1 Mechanism of Hippo signaling pathway transduction

In mammals, the Hippo signaling pathway is organized as a canonical serine/threonine kinase cascade. Within this cascade, the MST-LATS kinase can be activated by upstream signals, such as cell polarity, cell density, stress signals and mechanical cues (14, 15). Furthermore, the scaffolding protein Salvador homolog-1 (SAV1) binds to the mammalian Ste20-like kinase1/2 (MST1/2, orthologs of Hippo) via its SARAH domain, promoting MST1/2 autophosphorylation at Thr183/Thr180 sites to enhance kinase activity (16). Activated MST1/2 subsequently phosphorylates two critical regulatory domains of large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2 (LATS1/2, orthologs of Wts), including the Thr1079/Thr1041 sites in the hydrophobic motif (HM) and the Ser909/Ser872 sites in the activation loop (T-loop), thereby driving LATS1/2 activation (17). Additionally, MST1/2 phosphorylates the Thr12/Thr35 sites of the LATS1/2 coactivator Mps One Binder kinase activator-like 1A/1B (MOB 1A/B, orthologs of Mats), amplifying signaling through strengthened MOB1A/B-LATS1/2 interactions (18). Ultimately, the core effectors of the pathway, Yes-associated protein (YAP)/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ, also known as WWTR1), are phosphorylated by activated LATS1/2 at Ser127/Ser89 sites. This phosphorylation promotes YAP/TAZ cytoplasmic retention through 14-3–3 protein binding or facilitates their degradation via β-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase-mediated ubiquitination, suppressing their transcriptional activity (19). Conversely, Hippo pathway inactivation allows dephosphorylated YAP/TAZ to translocate into the nucleus, where they compete with VGLL4 (a Drosophila Tgi ortholog and transcriptional cofactor) to bind TEAD transcription factors (DNA-binding partners), regulating target genes governing cell proliferation, apoptosis and migration (10, 20) (Figure 1).

Recent studies have revealed the existence of more sophisticated regulatory mechanisms based on the classical Hippo signaling pathway. Qi et al. systematically analyzed the intermediate regulatory mechanism of the MST1/2-LATS1/2 kinase cascade, proposing two novel regulatory modules: HPO1 and HPO2. The HPO1 module involves WW and C2 domain-containing proteins (WWC1-3), which mediate LATS1/2-SAV1 interactions and localize the MST1/2-SAV1 complex to LATS1/2. The HOP2 module consists of neurofibromin 2 (NF2/Merlin) collaborating with mitogen-activated protein kinase 1-7 (MAP4K1-7, Hippo-like kinases), forming a redundant network with MST1/2 to regulate LATS1/2 activity (21–24). Furthermore, the transmembrane protein KIRREL1, a YAP/TAZ target protein, also enhances MST1/2-mediated LATS1/2 activation in a SAV1-dependent manner (25). Citron kinase (CIT), an AGC family kinase involved in mitotic regulation, exhibits dual regulatory roles in the pathway. On the one hand, it serves as an essential scaffolding protein bridging LATS2 and YAP during phosphorylation. On the other hand, it inhibits MST1-dependent LATS2 HM phosphorylation (26). This duality suggests that the effect of CIT on LATS2 may be dynamically modulated by the cellular microenvironment.

In conclusion, the Hippo signaling pathway governs the cellular localization and activity of the transcriptional coactivators YAP/TAZ via a highly conserved MST-LATS kinase cascade, which integrates diverse upstream signals to modulate the life activities of cells. Mounting evidence has further elucidated a sophisticated multi-tiered regulatory network, encompassing components such as the Hpo1 and Hpo2 modules, alongside factors including KIRREL1 and CIT. These discoveries substantially advance our comprehension of the pathway’s intricate complexity and context-dependent nature, while also offering novel insights into its molecular mechanisms in disease.

3.2 Hippo signaling pathway and ovarian dysfunction in PCOS

The pathogenesis of PCOS is rooted in its hallmark ovarian abnormalities, which provide a critical framework for investigating Hippo signaling dysregulation in this disorder.

3.2.1 Hippo signaling in normal follicular development

During the reproductive cycle, key components of the Hippo signaling pathway are widely localized in ovarian cells, including oocytes, granulosa cells (GCs), theca cells and luteal cells, with dynamic expression patterns (27). For example, MST1 translocates to the nucleus from the cytoplasm gradually during oocyte development and achieves nuclear localization in the antral-stage oocytes (28). Similarly, YAP demonstrates stage-specific localization patterns in both oocytes and granulosa cells From primordial to preovulatory follicles, YAP progressively accumulates in the nucleus but relocates to the cytoplasm with markedly reduced expression in postovulatory luteal cells (28, 29). This observation is corroborated in a bovine ovary study, where microarray analysis revealed a significantly elevated YAP1 activation in larger developing follicles (5–10 mm) (30).

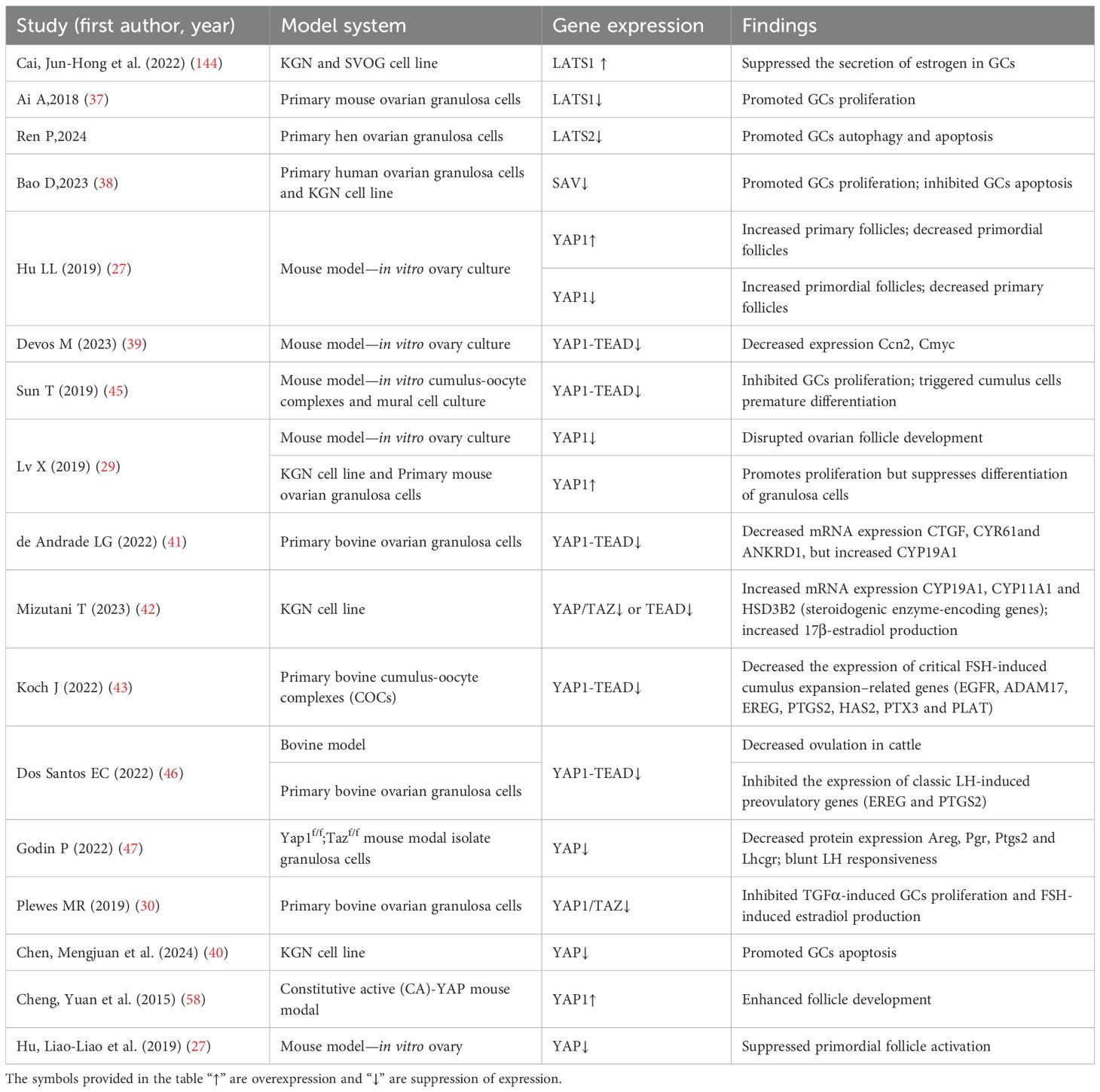

The Hippo signaling pathway governs the balance between primordial follicle dormancy and activation via mechanosensitive regulation. In mature ovaries, oocytes predominantly exist in a mechanically stressed state imposed by GCs and extracellular matrix (ECM), a condition critical for sustaining follicular dormancy and preserving female reproductive longevity (31). Subsequently, a series of studies confirms that mechanical signal during primordial follicle activation is involved in maintaining primordial follicle quiescence through activation of the Hippo signaling pathway (28, 32, 33). Furthermore, Liu et al. revealed that high cellular density promotes LATS1 SUMOylation at K830 residue (K829 in mice), enhancing kinase activity and amplifying Hippo signaling-mediated suppression of premature follicle activation (34–36).

Proliferation of GCs is also essential for primordial-to-primary follicle transition. Murine ovarian models demonstrate that activation of the Hippo signaling pathway downregulates pro-proliferative target genes CCN2 and CMYC, thereby inhibiting GCs proliferation while promoting apoptosis (27, 37–39). Recent work by Chen et al. further demonstrates that YAP transcriptional activity prevents GCs apoptosis through NEDD8-mediated K159 neddylation (40). Thus, the Hippo signaling pathway participates in folliculogenesis by regulating GCs proliferation/apoptosis. Notably, YAP also serves as a crucial hub for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)- and luteinizing hormone (LH)-mediated follicular development. Physiologically, FSH suppresses YAP-TEAD transcriptional activity in GCs, upregulating steroidogenic enzymes (CYP11A1, HSD3B2 and CYP19A1) to enhance estradiol synthesis and dominant follicle selection (41, 42). Conversely, in cumulus cells FSH induces YAP-TEAD interactions, upregulating cumulus expansion genes (EGFR, ADAM17, EREG, and PTGS2) to promote oocyte maturation (43). Additionally, Hippo-YAP signaling also modulates LH secretion and function. In adenohypophysis, YAP/TAZ is a negative regulatory factor for LH secretion (44). During LH-induced ovulation, transient inactivation of the Hippo signaling pathway promotes nuclear YAP1 binding to the amphiregulin (Areg) promoter, thereby activating ERK1/2 signaling to induce LH target gene expression. Subsequent LH-induced cAMP/PKA signaling sequesters YAP in the cytoplasm, driving GC luteinization (45–47). Collectively, mature follicle formation and ovulation depend on precisely coordinating the activity of the Hippo signaling pathway (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2.2 Ovulation dysfunction in PCOS

Ovulatory dysfunction is a core diagnostic phenotype of PCOS, characterized by oligo-ovulation or anovulation, and its pathological mechanisms are closely associated with follicular developmental arrest and maturation impairment. Huang et al. observed that ovarian tissues of DHEA-induced PCOS murine models display an elevated YAP and phosphorylated YAP (p-YAP) expression but a significant reduction in p-YAP/YAP ratio (48). Mechanistically, this aberrant YAP1 activation in PCOS stimulates GCs hyperproliferation and downregulates luteinization-associated LH target genes (CYP11A1, STAR, LHCGR, PGR), which induces GC differentiation arrest, maintaining it in a non-luteinized state and triggering the pathological accumulation of immature ovarian follicles (49). Notably, impaired FSH signaling in PCOS synergistically contributes to dominant follicle selection failure (50). Recent studies reveal that YAP overexpression can impede follicular maturation by suppressing FSH responsiveness in GCs (42). In addition, a pathogenic androgen-YAP positive feedback loop may exist in PCOS. Jiang et al. found that androgens can attenuate YAP1 promoter methylation in a dose-dependent manner to increase YAP1 transcriptional activation in GCs (51). Concurrently, YAP-TEAD complex upregulation inhibits aromatase activity through suppressing CYP19A1 expression to affect the biotransformation of androgens to estrogens. This dual mechanism culminates in localized ovarian estrogen deficiency and androgen excess that obstruct follicle maturation and ovulation (42). Collectively, these findings suggest that abnormal YAP activation is intimately linked to ovulation dysfunction in PCOS (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Potential molecular mechanisms of the Hippo signaling pathway in PCOS follicular development. (A) Primordial folliclar stage: Reduced extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness maintains Hippo signaling activity and promotes follicular activation. (B) Preovulatory folliclar stage: Androgen-induced YAP upregulation inhibits FSH and LH effects on follicular development, impairing dominant follicle formation and ovulation.

3.2.3 Decreased ovarian reserve (DOR) in PCOS

Observational clinical cohort studies have revealed that some PCOS patients exhibit DOR, but the exact mechanism is unclear (52). Dysregulation of ECM homeostasis in GCs may contribute to this pathology. For PCOS, ECM-related genes are down-regulated in the GCs, including ECM1, laminin α3/β1 (LAMA3/LAMB1) and fibronectin 1 (FN1), while matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9) are upregulated, indicating a reduction in ECM stiffness (53–55). Furthermore, genomic analysis identified that the Ras homology growth-related (RHOG) gene, which regulates actin cytoskeleton polymerization, is abnormally elevated in PCOS patients’ GCs (56). When GCs perceive a decreased mechanical stress, F-actin is induced to form and hinders the Hippo signaling pathway, thereby triggering premature activation of dormant follicles (7, 27, 57). Pharmacological induction of actin polymerization corroborates this mechanism, as enhanced YAP nuclear translocation drives follicular recruitment (58). Thus, Hippo pathway dysregulation in GCs likely contributes to the pathological early follicular recruitment observed in PCOS-associated DOR (Figure 2A).

3.2.4 Ovarian microenvironmental perturbations in PCOS

The ovarian microenvironment provides nutritional support and signaling transduction essential for normal follicular development (59). Patil et al. found that follicular growth arrest, luteal insufficiency and recurrent miscarriage in PCOS are associated with impairment of the vascular system (60). Moreover, follicular fluid in PCOS displays a down-regulation of pro-angiogenic genes (FGFR1, VEGFA, FN1), reflecting compromised vascular development (60). Genome-wide association analysis further identified a significant association between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene polymorphisms and PCOS susceptibility (61). Mechanistic investigations demonstrate that neovascularization is dependent on a feed-forward loop between YAP/TAZ and VEGF-VEGFR2 signaling in endothelial cells mediated by cytoskeletal dynamics, while YAP suppression disrupts angiogenesis (62, 63). Consequently, diminished pro-angiogenic factors in PCOS microenvironments may impede vascular sprouting by inhibiting YAP signaling in endothelial cells.

Emerging evidence implicates there are relationships between the ovarian microenvironment exposure to environmental contaminants, such as perfluoroalkyl and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), zearalenone (ZEN), microplastics and phthalates, and the risk of PCOS, which involve the Hippo signaling pathway dysregulation (64–68). Firstly, Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure can result in ovarian fibrosis and DOR, which are associated with abnormally high expression of YAP (69, 70). Secondly, co-exposure of polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-NPs) and phthalates induced PCOS-like phenotypes in mice via ROS-Hippo signaling activation (66, 71). Finally, single-cell RNA sequencing identifies the Hippo signaling pathway disruption as the molecular basis for ZEN-induced primordial follicle assembly defects (72). These findings establish a theoretical framework linking environmental toxicants to PCOS through the modulation of the Hippo signaling pathway, advancing etiological and therapeutic insights.

Overall, the Hippo signaling pathway plays a central role in ovarian dysfunction associated with PCOS. Under physiological conditions, this pathway is instrumental in the precise regulation of follicular development, granulosa cell proliferation and differentiation, hormonal response, and the ovulation process. In PCOS, however, significant dysregulation of this pathway (e.g., abnormal nuclear localization and sustained activation of YAP) triggers a cascade of pathological alterations, including imbalances in granulosa cell proliferation and differentiation, premature follicular activation and impaired angiogenesis, etc. Collectively, these disruptions contribute to ovulatory dysfunction, DOR and an aberrant ovarian microenvironment. The above findings not only provide deeper insights into the pathogenesis of PCOS-related ovarian dysfunction but also establish a rational basis for developing novel therapeutic strategies aimed at the Hippo signaling pathway.

3.3 Hippo signaling pathway and metabolic dysregulation in PCOS

PCOS is not only a reproductive disorder, but also a systemic metabolic syndrome characterized by IR, hyperinsulinemia, dyslipidemia and obesity. Emerging evidence implicates the Hippo signaling pathway as a critical regulator of these metabolic perturbations (Supplementary Table 2).

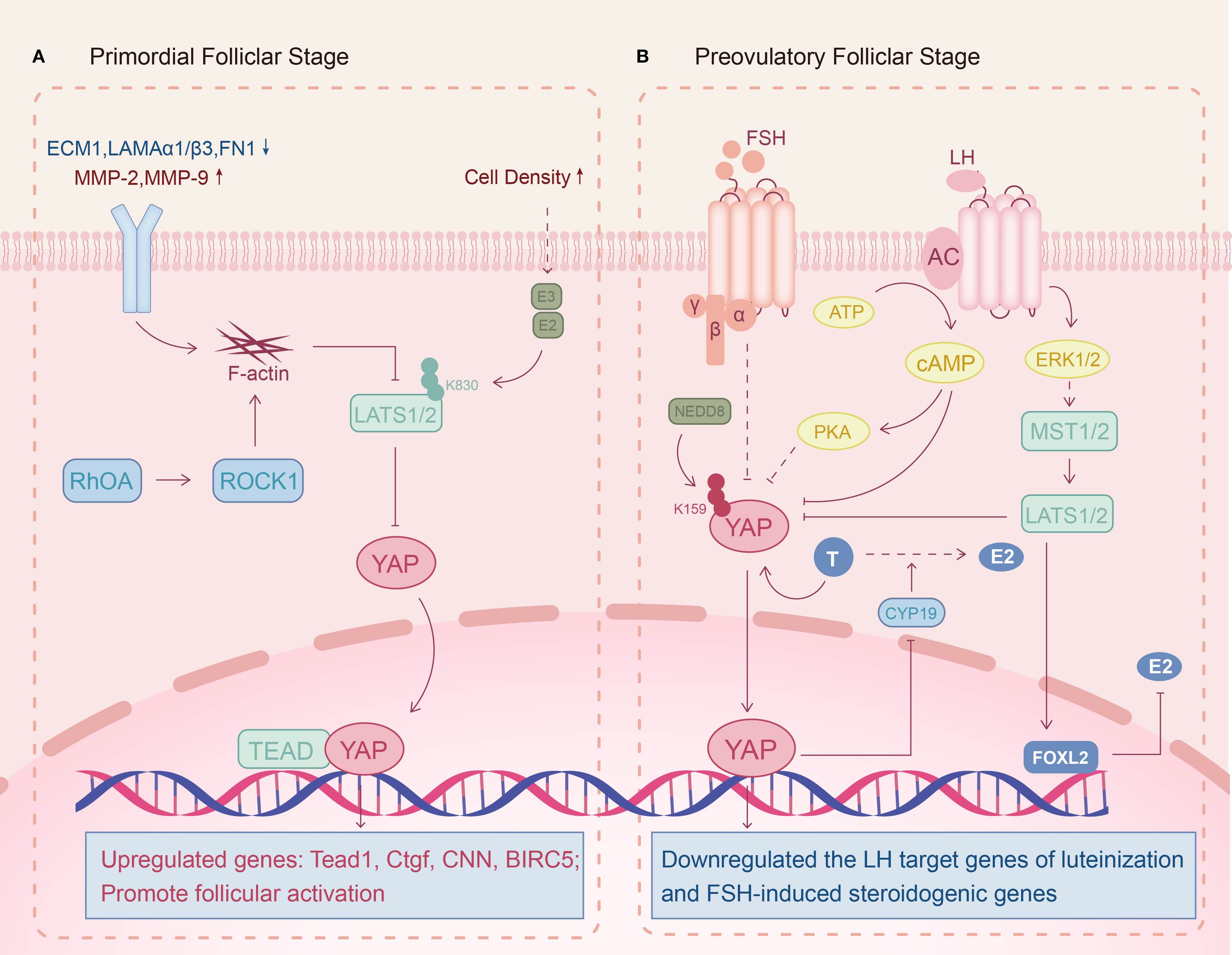

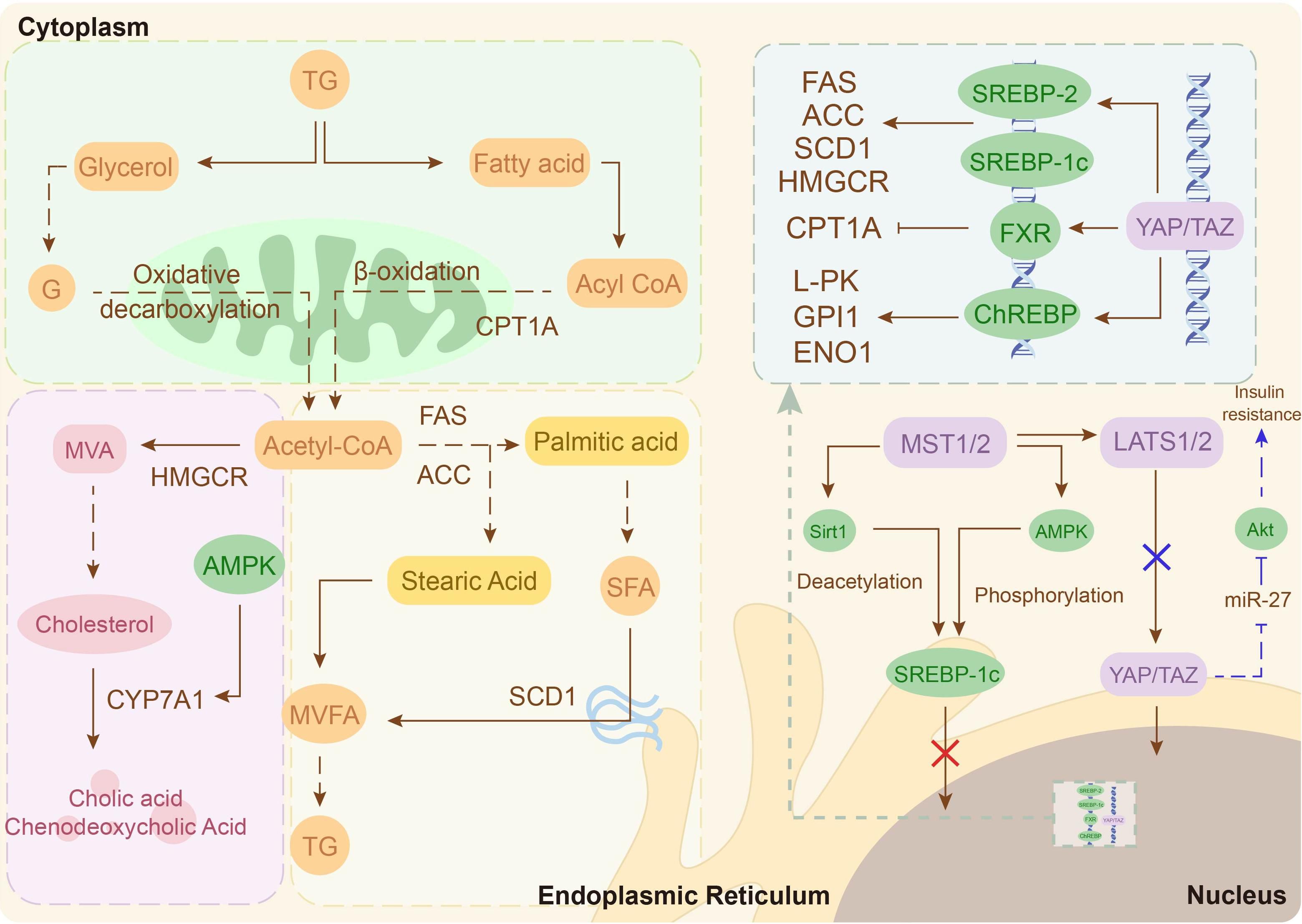

3.3.1 Lipid metabolism dysregulation in PCOS

The liver, a central organ in lipid homeostasis, exhibits Hippo-mediated dysregulation in PCOS (73). Clinical studies reveal a bidirectional association between PCOS and MASLD, though the underlying molecular mechanisms remain unclear (74, 75). Further exploration finds that hyperandrogenemia induces metabolic disruption in the liver of PCOS via increasing YAP expression and activity (73). Mechanistically, YAP is a co-activator of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBP-1c and SREBP-2) and a nuclear cofactor for carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP) that amplifies the expression of their target genes, thereby accelerating fatty acid and cholesterol production in hepatocytes (76, 77). In addition, inhibition of fatty acid oxidation mediated by the YAP-FXR axis can further exacerbate lipid deposition (78). In conclusion, the increased activity and expression levels of YAP in patients with PCOS are one of the major causes of their hepatic lipid metabolism disorders (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Potential molecular mechanisms of the Hippo signaling pathway in hepatic lipid metabolism. Hyperlipidemia inhibits Hippo signaling, activating YAP/TAZ and enhancing the transcriptional activity of SREBP-2, SREBP-1c and ChREBP, thereby driving hepatic lipid metabolism. Additionally, the Hippo signaling pathway inactivation suppresses insulin signaling, exacerbating insulin resistance (IR) (blue arrow).

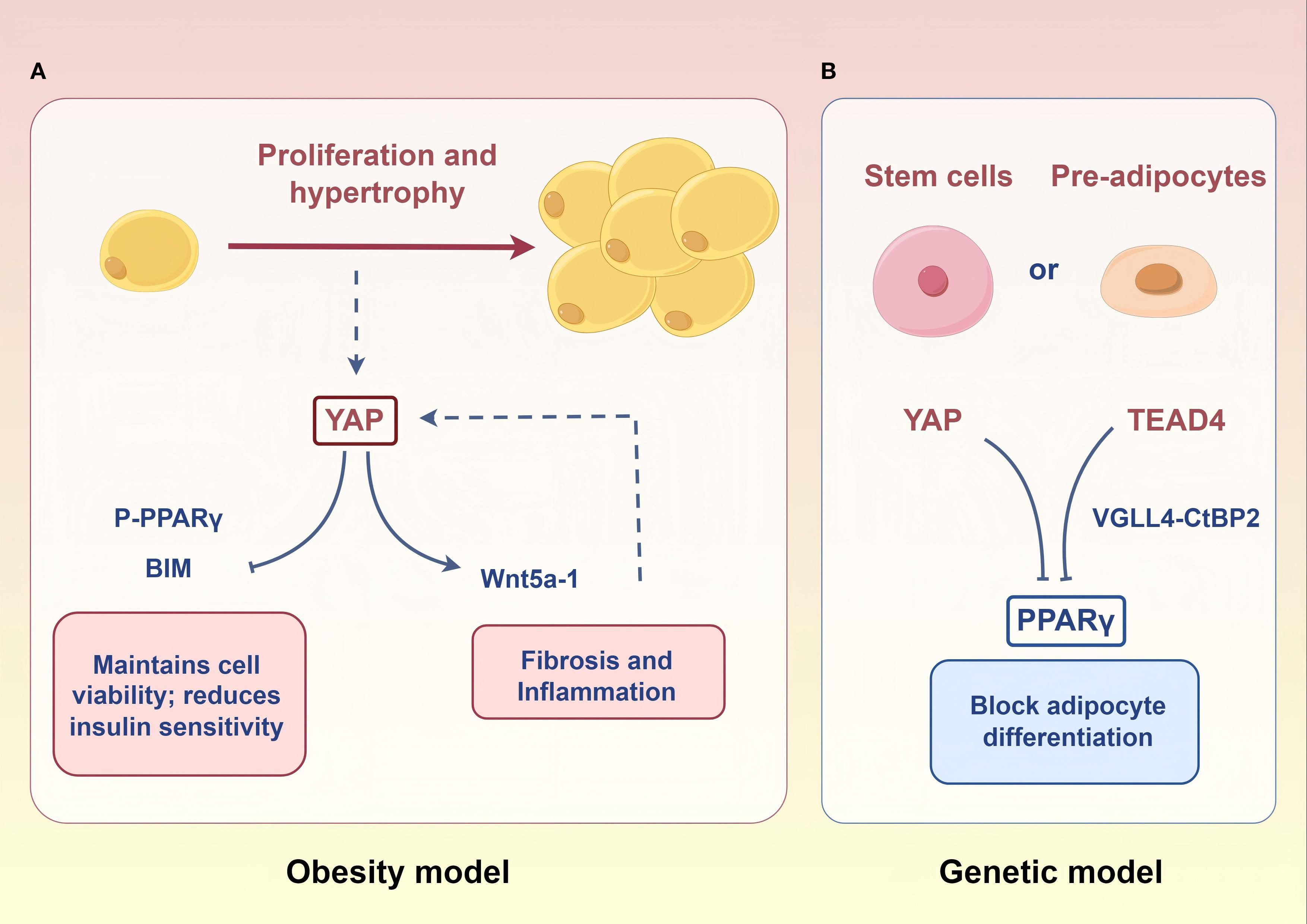

Obesity is another important phenotype of lipid disorders in PCOS, affecting approximately 50% of these patients (79). Its pathological changes are characterized by adipose tissue excessive expansion (hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia) (80). Despite the lack of studies on the Hippo signaling pathway in adipose tissue of obese PCOS patients, researchers have observed significantly elevated YAP activity in white adipose tissue of humans and mice with obesity (81). Mechanistically, high YAP activity can exacerbate adipocyte hypertrophy by inducing Wnt5a-1 expression (82, 83). Therefore, high YAP activity in adipocytes of obese PCOS patients may contribute to their fat accumulation.

However, in normal-weight women with PCOS, adipogenic gene expression (PPARγ, CEBPα, AGPAT2) is abnormally elevated in their abdominal adipose-derived stem cells compared to healthy controls (84). Furthermore, a meta-analysis confirmed a significant association between PPARG gene polymorphisms and PCOS susceptibility (85). These imply that enhanced adipogenic tendency is a risk for non-obese patients. In recent years, a series of laboratory studies have demonstrated that the YAP-PPARγ regulatory axis is a key molecular mechanism for the differentiation of endocrine stem cells/pre-adipocytes to mature adipocytes (86–88). Therefore, there may be a lipogenic tendency mediated by the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway in preadipocytes of non-obese women with PCOS (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Potential molecular mechanisms of the Hippo signaling pathway in adipose tissue. (A) In the context of obesity, heightened YAP activity within mature adipocytes drives adipocyte hypertrophy and proliferation. (B) In a potential genetic model, elevated PPARγ expression in stem cells/pre-adipocytes of lean individuals enhances their differentiation into mature adipocytes. The downregulation of YAP and TEAD4 expression may potentiate this pro-differentiation effect. Figure was created by Figdraw (www.figdraw.com).

3.3.2 Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in PCOS

IR as a core phenotype of metabolic disorders in PCOS, involves functional dysregulation across multiple organs (89). Hepatic lipid accumulation promotes IR by inducing the Hippo signaling pathway inactivation to amplify miR-27-mediated suppression of Akt signaling (73). Moreover, insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis in adipose tissue are negatively correlated with YAP activity (90, 91). Skeletal muscle, as another major target organ for insulin, occurs IR is closely related to reduced YAP levels (92, 93). Mechanistically, inhibited YAP can lead to IR by inducing mitochondrial fatty acid oxidizing capacity dysfunction in skeletal muscle (93). Furthermore, although not clear in skeletal muscle, reduced YAP/TAZ activity has been shown to cause downregulation of IRS1 phosphorylation levels in endometrial cancer cells, which in turn affects insulin sensitivity (94). Notably, hepatic lipid accumulation, adipose tissue dysfunction, mitochondrial dysfunction and IRS1/PI3K/Akt signaling inhibition in skeletal muscle underlies IR pathogenesis in PCOS (91, 95, 96). Collectively, Hippo-YAP dysregulation underpins IR pathogenesis through hepatic steatosis, adipocyte dysfunction, and skeletal muscle metabolic inflexibility.

Hyperinsulinemia (HI), caused by pancreatic β-cell hypersecretion, exhibits a bidirectional pathological association with IR (89). Emerging clinical evidence suggests HI may precede IR onset in PCOS, correlating with hyperandrogenemia (97, 98). Prenatal androgen exposure induces β-cell apoptosis, whereas postnatal exposure triggers compensatory β-cell hyperplasia and HI (99–101). Mechanistic studies demonstrate that the Hippo pathway collaborates with neurogenin 3 (NGN3) to silence YAP during endocrine lineage specification, which is a prerequisite for functional β-cell differentiation (102–104). Conversely, aberrant YAP activation disrupts its functional maturation (105). Intriguingly, the upregulation of YAP expression in mature β-cells stimulates proliferation without affecting function (106–108). Given androgen-induced YAP activation in hepatic and ovarian tissues, we propose that hyperandrogenemia drives HI via ectopic YAP activation in pancreatic β-cells, establishing a self-reinforcing endocrine-metabolic loop.

In summary, dysregulation of the Hippo signaling pathway appears to be a critical node in the molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic disturbances in PCOS. This pathway not only contributes to hepatic lipid accumulation by regulating lipid synthesis and lipolysis, but also mediates adipose tissue dysfunction. Furthermore, it extensively influences insulin signaling transduction in peripheral tissues, promoting the development of systemic insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. These mechanisms highlight the significant role of the Hippo signaling pathway in the systemic metabolic dysregulation of PCOS, providing new perspectives on the disorder’s molecular underpinnings.

3.4 Hippo signaling pathway and chronic low-grade inflammation in PCOS

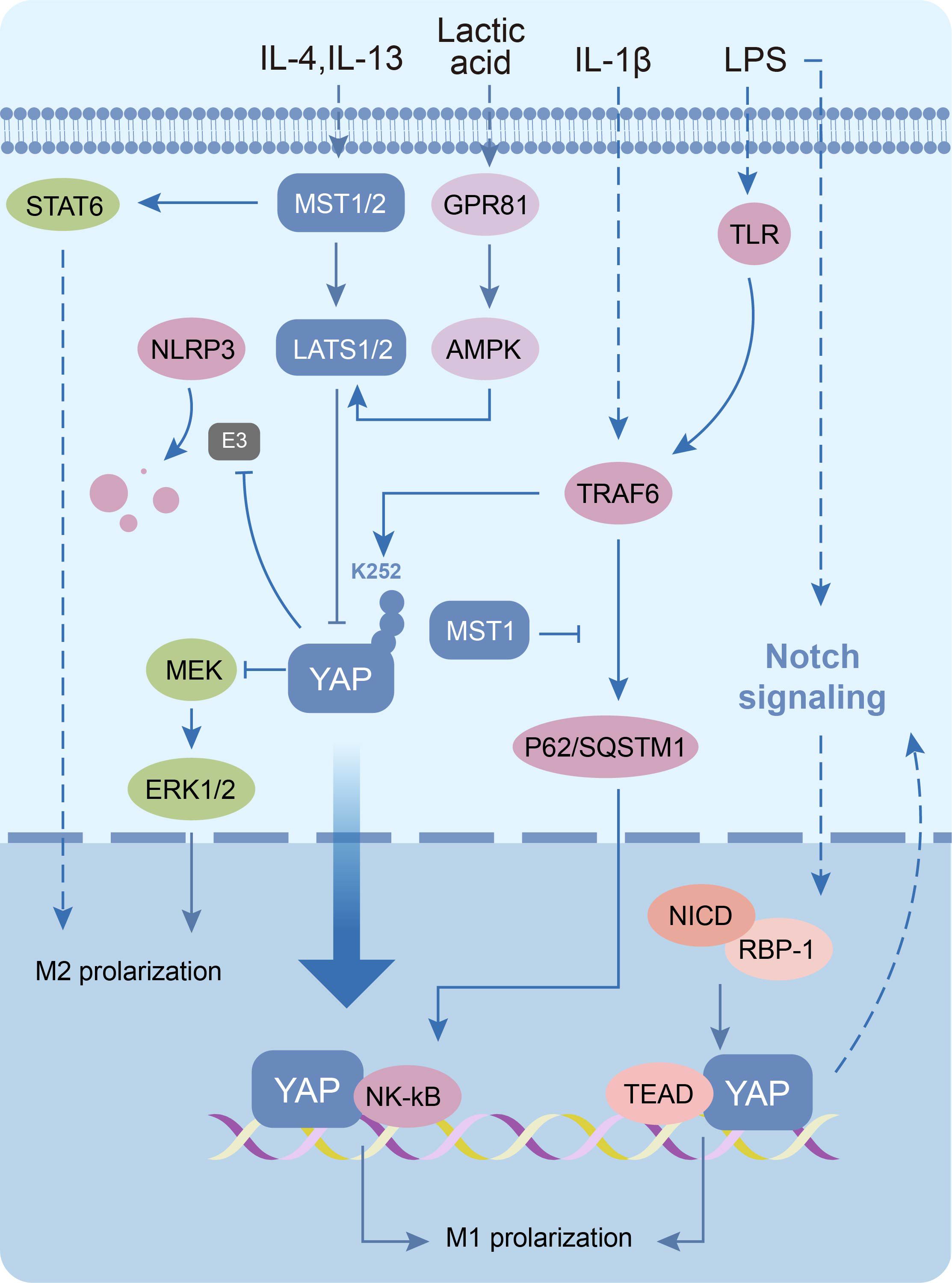

In recent years, researchers have identified chronic low-grade inflammation as one of the central aspects of PCOS pathophysiology, forming a complex network with IR, hyperandrogenemia and metabolic abnormalities (109). Chronic low-grade inflammation in PCOS is mainly manifested in the form of increased levels of various inflammatory factors (eg: IL-6, IL-1β, IL-18) and dysregulated M1/M2 macrophage polarization in ovarian microenvironments (110, 111). Mechanistic studies reveal YAP drives inflammation through dual mechanisms. During LPS/TFN-γ-induced pro-inflammatory M1 polarization, YAP/TAZ overexpression stabilizes cytosolic NLRP3 inflammasomes by inhibiting β-TrCP1-mediated ubiquitination in the cytoplasm; as well as combining with TEAD to directly activate IL-6 transcription via promoter binding in the nuclear (112, 113). Furthermore, YAP amplifies inflammation through NF-κB and Notch1 pathway activation (114–116). Notably, the inflammatory factor IL-1β can in turn promote macrophage M1 polarization by inducing ubiquitination of YAP at the K252 site to increase activity (117). Conversely, IL-4/IL-13-induced anti-inflammatory M2 polarization requires deregulating YAP inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathways, thereby restoring anti-inflammatory gene expression (Arg, Egr2, Cd206, Ym1, Fizz1) (118, 119). These findings implicate that YAP-mediated macrophage polarization imbalance may be a pivotal mechanism sustaining chronic inflammation in PCOS (Figure 5) (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 5. Molecular mechanisms of the Hippo signaling pathway in macrophages. The Hippo signaling pathway inactivation induces macrophage M1 polarization as well as increased levels of inflammatory vesicle NLRP3. Conversely, the pathway activation promotes macrophage M2 polarization.

3.5 Therapeutic prospects in PCOS: targeting the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway

3.5.1 Modulating follicular development to restore fertility

Follicular development modulation represents a cornerstone for addressing PCOS-related infertility. Laparoscopic ovarian drilling (LOD), as a surgical intervention for clomiphene citrate (CC)-resistant patients, inhibits Hippo signaling to promote primordial follicle activation, though its efficacy remains debated (7, 120–123). Emerging evidence suggests that the Hippo signaling pathway activation represents an effective therapeutic mechanism in PCOS patients with impaired follicular development. Huang et al. observe that verteporfin (a YAP-TEAD interaction inhibitor) treatment in PCOS mice can reduce serum anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels and restore follicular growth (48). Furthermore, YAP also serves as a molecular hub of biopharmaceutical and nutraceutical interventions for PCOS. Firstly, anti-growth factor-releasing peptide antibodies alleviate PCOS phenotypes in murine models, such as weight gain, estrous cycle disruption, ovarian morphologic aberrations and hormonal imbalances, via silencing Gαq/11 or YAP in GCs (124). Secondly, adding n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to the diet significantly alleviated hormonal and estrous cycle disturbances in PCOS mice by reducing YAP1/Nrf2 signaling in GCs (125). Therefore, targeting the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway is a promising therapeutic strategy for restoring fertility in PCOS patients.

3.5.2 Metabolic correction: adipose and insulin signaling

Weight management constitutes the cornerstone of metabolic intervention in PCOS, particularly in patients with comorbid overweight/obesity (79). Current therapies reduce adipocyte hypertrophy but fail to modulate hyperplasia (80, 126). A mechanistic study by Wang et al. has revealed that YAP inhibition selectively induces apoptosis in mature adipocytes (81). Notably, the adipogenic marker PPARγ in preadipocytes exhibits a significant correlation with PCOS metabolic parameters, which is negatively regulated by YAP and TEAD4 (127–129). In addition, MST1/2 gene deletion enhances adipocyte mitochondrial autophagy activity through a non-YAP-dependent pathway, thereby elevating the efficiency of energy metabolism and inhibiting dietary obesity (130). Liraglutide as a common insulin sensitizer in PCOS patients, despite its known glucose-lowering effect, also inhibits the proliferation of preadipocytes through activation of the Hippo signaling pathway but also accelerates adipogenic differentiation (131).

IR management is the center of PCOS metabolic intervention. Experimental evidence indicates that adipocyte-specific YAP/TAZ knockout significantly enhances insulin sensitivity in obese murine models (90, 132). In addition, both clinical observations and animal studies demonstrate reduced proportions of insulin-sensitive type I muscle fibers in PCOS, which may be an important pathological basis for skeletal muscle IR (96, 133). Remarkably, LATS1/2 knockout in mice can significantly increase the percentage of type I muscle fibers in skeletal muscle (134). Thus, precise modulation targeting the Hippo signaling pathway may provide an innovative therapeutic strategy to ameliorate PCOS metabolic disorders.

3.5.3 Anti-inflammatory interventions

Although current clinical guidelines for PCOS have not yet incorporated systemic anti-inflammatory treatment regimens, accumulating experimental evidence underscores the pivotal role of inflammatory modulation in improving reproductive and metabolic outcomes in PCOS (109, 126). Recently, Wang et al. proposed a potential molecular pathway of PUFAs in PCOS treatment. Their findings demonstrate that PUFAs significantly upregulate anti-inflammatory gene expression and induce macrophage M2-like polarization by inhibiting RhoA-YAP1 signaling (135, 136). This implies a potential therapeutic value of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway remodeling immunocyte phenotype for anti-inflammatory interventions in PCOS.

3.5.4 Comorbidity management

PCOS combined with MASLD significantly constrains therapeutic options, exacerbates disease management complexity and amplifies long-term adverse outcomes (137). Researchers have found that hyperlipidemia and IR are shared pathological foundations between PCOS and MASLD, suggesting potential synergistic therapeutic targets (138). In clinical practice, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, thiazolidinediones, and statins have demonstrated dual therapeutic effects, their side-effect profiles necessitate novel approaches (139). Animal experiments have confirmed that YAP knockout in MASLD model mice can effectively reduce hepatic triglyceride (TG) and Perilipin 2 (PLIN2) levels and ameliorate lipid metabolism disorders (140). Moreover, emerging therapeutic approaches utilizing chrysanthemum lactone (PAR), anti-miR-199a-5p exosome and Hep@PGEA/MST1 nanocarrier demonstrate reducing hepatic lipid burden effects by disrupting the Hippo signaling pathway (141–143). These findings collectively propose that targeting the expression of Hippo signaling components to regulate metabolic disorders in the liver may be a novel way to treat PCOS-MASLD comorbidities.

Notably, LATS1 activity in GCs is negatively correlated with steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)-mediated estrogen synthesis (144). However, pathological estrogen elevation significantly increases the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), a serious complication frequently observed in PCOS patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF)/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatments (145). Consequently, activation of LATS1 in GCs may be a preventive strategy against OHSS during PCOS patients’ assisted reproductive therapy.

In conclusion, targeting the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway represents a promising multifaceted therapeutic strategy for PCOS, encompassing key areas such as reproductive function, metabolic regulation, inflammatory response and comorbidity management. Specifically, modulation of this pathway could potentially promote follicular development, improve metabolic disorders, regulate immune responses and prevent complications such as OHSS and MASLD.

The current clinical management of PCOS is still based on symptomatic relief as the main goal with limited therapeutic options (146). To address this current situation, developing stage-specific and tissue-targeted Hippo pathway modulation strategies holds significant clinical promise. However, the clinical translation of such strategies faces several challenges, including limitations in targeting precision, delivery efficiency, biocompatibility, safety, stability, and scalable production. Therefore, future research should emphasize multidisciplinary collaboration to optimize delivery systems, thereby providing more robust and precise tools for disease treatment. Furthermore, significantly upregulated YAP expression has been observed in ovarian granulosa cells of PCOS patients, suggesting that quantitative assessment of Hippo signaling biomarkers (e.g., p-YAP and YAP levels) may facilitate early diagnosis and real-time therapeutic monitoring (51).

4 Conclusions

This review systematically delineates the multidimensional regulatory mechanisms of the Hippo signaling pathway and its core components (MST1/2, LATS1/2, YAP/TAZ) in the pathogenesis of PCOS. In reproductive dysfunction, Hippo dysregulation drives primordial follicle depletion, granulosa cell apoptosis-proliferation imbalance, and anovulation, while also mediating environmental toxicant-induced ovarian injury. Metabolically, this pathway is involved in systemic metabolic disturbances in PCOS by regulating pancreatic β-cell function, adipose tissue differentiation/function, skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity, and hepatic lipid metabolism. Immunologically, YAP-driven M1 macrophage polarization might emerge as a pivotal mechanism underlying chronic low-grade inflammation in PCOS. Collectively, Hippo signaling emerges as a molecular linchpin integrating the reproductive-metabolic-immune axis in PCOS, establishing a novel therapeutic paradigm for targeted interventions (Table 1).

Author contributions

JW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. GC: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors received the Basic Research Program of Shenzhen (JCYJ20230807150200001 and JCYJ20220530172814032) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei province (No.2022CFB200) support for this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all authors for their contributions to the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2025.1623143/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome

IR: Insulin Resistance

GWAS: Genome-wide association study

SAV1: Salvador homolog-1

MST1/2: Mammalian Ste20-like kinase1/2

LATS1/2: Large tumor suppressor kinase 1/2

HM: Hydrophobic motif

T-loop: The activation loop

MOB 1A/B: Mps One Binder kinase activator-like 1A/1B

YAP: Yes-associated protein

TAZ: Transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif

WWC1-3: WW and C2 domain-containing proteins

NF2/Merlin: Neurofibromin 2

MAP4K1-7: Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1-7

CIT: Citron kinase

GCs: Granulosa cells

ECM: Extracellular matrix

FSH: Follicle-stimulating hormone

LH: Luteinizing hormone

Areg: Amphiregulin

p-YAP: Phosphorylated YAP

LAMA3/LAMB1: Laminin α3/β1

FN1: Fibronectin 1

MMP: Matrix metalloproteinases

RHOG: Ras homology growth-related

VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor

PFAS: Perfluoroalkyl and poly-fluoroalkyl substances

ZEN: Zearalenone

PFOA: Perfluorooctanoic acid

PS-NPs: Polystyrene nanoparticles

MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

SREBP-1C/2: Sterol regulatory element binding protein 1C/2

ChREBP: Carbohydrate response element binding protein

HI: Hyperinsulinemia

NGN3: Neurogenin 3

LOD: Laparoscopic ovarian drilling

CC: Clomiphene citrate

AMH: Anti-Müllerian hormone

PUFAs: Polyunsaturated fatty acids

GLP-1: Glucagon-like peptide-1

TG: Triglyceride

PLIN2: Perilipin 2

PAR: Chrysanthemum lactone

StAR: Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

OHSS: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome

IVF: In vitro fertilization

ICSI: Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

References

1. Stener-Victorin E, Teede H, Norman RJ, Legro R, Goodarzi MO, Dokras A, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2024) 10:27. doi: 10.1038/s41572-024-00511-3

2. Sadeghi HM, Adeli I, Calina D, Docea AO, Mousavi T, Daniali M, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: A comprehensive review of pathogenesis, management, and drug repurposing. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(2):583. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020583

3. Mauviel A, Nallet-Staub F, and Varelas X. Integrating developmental signals: A hippo in the (Path)Way. Oncogene. (2012) 31:1743–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.363

4. Badouel C and McNeill H. Snapshot: the hippo signaling pathway. Cell. (2011) 145:484–.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.009

5. Chan SW, Ong C, and Hong W. The recent advances and implications in cancer therapy for the hippo pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. (2025) 93:102476. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2025.102476

6. Hsueh AJ, Kawamura K, Cheng Y, and Fauser BC. Intraovarian control of early folliculogenesis. Endocr Rev. (2015) 36:1–24. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1020

7. Hsueh AJW and Kawamura K. Hippo signaling disruption and ovarian follicle activation in infertile patients. Fertil Steril. (2020) 114:458–64. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.07.031

8. Zhu M, Xu M, Zhang J, and Zheng C. The role of hippo pathway in ovarian development. Front Physiol. (2023) 14:1198873. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1198873

9. Yang H, Yang J, Zheng X, Chen T, Zhang R, Chen R, et al. The hippo pathway in breast cancer: the extracellular matrix and hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25(23):12868. doi: 10.3390/ijms252312868

10. Ma S, Meng Z, Chen R, and Guan KL. The hippo pathway: biology and pathophysiology. Annu Rev Biochem. (2019) 88:577–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111829

11. Zheng Y and Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and disease. Dev Cell. (2019) 50:264–82. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.06.003

12. Li T, Zhao H, Zhao X, Zhang B, Cui L, Shi Y, et al. Identification of yap1 as a novel susceptibility gene for polycystic ovary syndrome. J Med Genet. (2012) 49:254–7. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100727

13. Clark KL, George JW, Przygrodzka E, Plewes MR, Hua G, Wang C, et al. Hippo signaling in the ovary: emerging roles in development, fertility, and disease. Endocr Rev. (2022) 43:1074–96. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnac013

14. Juan WC and Hong W. Targeting the hippo signaling pathway for tissue regeneration and cancer therapy. Genes (Basel). (2016) 7(9):55. doi: 10.3390/genes7090055

15. Fu M, Hu Y, Lan T, Guan KL, Luo T, and Luo M. The hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2022) 7:376. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01191-9

16. Tran T, Mitra J, Ha T, and Kavran JM. Increasing kinase domain proximity promotes mst2 autophosphorylation during hippo signaling. J Biol Chem. (2020) 295:16166–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015723

17. Hoa L, Kulaberoglu Y, Gundogdu R, Cook D, Mavis M, Gomez M, et al. The characterisation of lats2 kinase regulation in hippo-yap signalling. Cell Signal. (2016) 28:488–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.02.012

18. Ni L, Zheng Y, Hara M, Pan D, and Luo X. Structural basis for mob1-dependent activation of the core mst-lats kinase cascade in hippo signaling. Genes Dev. (2015) 29:1416–31. doi: 10.1101/gad.264929.115

19. Zhao B, Li L, Tumaneng K, Wang CY, and Guan KL. A coordinated phosphorylation by lats and ck1 regulates yap stability through scf(Beta-trcp). Genes Dev. (2010) 24:72–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1843810

20. Koontz LM, Liu-Chittenden Y, Yin F, Zheng Y, Yu J, Huang B, et al. The hippo effector yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped-mediated default repression. Dev Cell. (2013) 25:388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.021

21. Qi S, Zhong Z, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Ma M, Wang Y, et al. Two hippo signaling modules orchestrate liver size and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. (2023) 42:e112126. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022112126

22. Qi S, Zhu Y, Liu X, Li P, Wang Y, Zeng Y, et al. Wwc proteins mediate lats1/2 activation by hippo kinases and imply a tumor suppression strategy. Mol Cell. (2022) 82:1850–64.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2022.03.027

23. Zheng Y, Wang W, Liu B, Deng H, Uster E, and Pan D. Identification of happyhour/map4k as alternative hpo/mst-like kinases in the hippo kinase cascade. Dev Cell. (2015) 34:642–55. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.08.014

24. Meng Z, Moroishi T, Mottier-Pavie V, Plouffe SW, Hansen CG, Hong AW, et al. Map4k family kinases act in parallel to mst1/2 to activate lats1/2 in the hippo pathway. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:8357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9357

25. Gu Y, Wang Y, Sha Z, He C, Zhu Y, Li J, et al. Transmembrane protein kirrel1 regulates hippo signaling via a feedback loop and represents a therapeutic target in yap/taz-active cancers. Cell Rep. (2022) 40:111296. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111296

26. Tran THY, Yang DW, Kim M, Lee DH, Gai M, Di Cunto F, et al. Citron kinase interacts with lats2 and inhibits its activity by occluding its hydrophobic phosphorylation motif. J Mol Cell Biol. (2019) 11:1006–17. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjz013

27. Hu LL, Su T, Luo RC, Zheng YH, Huang J, Zhong ZS, et al. Hippo pathway functions as a downstream effector of akt signaling to regulate the activation of primordial follicles in mice. J Cell Physiol. (2019) 234:1578–87. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27024

28. De Roo C, Lierman S, Tilleman K, and De Sutter P. In-vitro fragmentation of ovarian tissue activates primordial follicles through the hippo pathway. Hum Reprod Open. (2020) 2020:hoaa048. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa048

29. Lv X, He C, Huang C, Wang H, Hua G, Wang Z, et al. Timely expression and activation of yap1 in granulosa cells is essential for ovarian follicle development. FASEB J. (2019) 33:10049–64. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900179RR

30. Plewes MR, Hou X, Zhang P, Liang A, Hua G, Wood JR, et al. Yes-associated protein 1 is required for proliferation and function of bovine granulosa cells in vitro†. Biol Reprod. (2019) 101:1001–17. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz139

31. Nagamatsu G, Shimamoto S, Hamazaki N, Nishimura Y, and Hayashi K. Mechanical stress accompanied with nuclear rotation is involved in the dormant state of mouse oocytes. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaav9960. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav9960

32. Zhang T, Lin H, Ren T, He M, Zheng W, Tong Y, et al. Rock1 is a multifunctional factor maintaining the primordial follicle reserve and follicular development in mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2024) 326:C27–c39. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00019.2023

33. Fiorentino G, Cimadomo D, Innocenti F, Soscia D, Vaiarelli A, Ubaldi FM, et al. Biomechanical forces and signals operating in the ovary during folliculogenesis and their dysregulation: implications for fertility. Hum Reprod Update. (2023) 29:1–23. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmac031

34. Mei L, Qv M, Bao H, He Q, Xu Y, Zhang Q, et al. Sumoylation activates large tumour suppressor 1 to maintain the tissue homeostasis during hippo signalling. Oncogene. (2021) 40:5357–66. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01937-9

35. Feng Y, Cui P, Lu X, Hsueh B, Möller Billig F, Zarnescu Yanez L, et al. Clarity reveals dynamics of ovarian follicular architecture and vasculature in three-dimensions. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:44810. doi: 10.1038/srep44810

36. Gershon E and Dekel N. Newly identified regulators of ovarian folliculogenesis and ovulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(12):4565. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124565

37. Ai A, Xiong Y, Wu B, Lin J, Huang Y, Cao Y, et al. Induction of mir-15a expression by tripterygium glycosides caused premature ovarian failure by suppressing the hippo-yap/taz signaling effector lats1. Gene. (2018) 678:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.08.018

38. Bao D, Gao L, Xin H, and Wang L. Lncrna-fmr6 directly binds sav1 to increase apoptosis of granulosa cells in premature ovarian failure. J Ovarian Res. (2023) 16:65. doi: 10.1186/s13048-023-01121-5

39. Devos M, Dias Nunes J, Donfack Jiatsa N, and Demeestere I. Regulation of follicular activation signaling pathways by in vitro inhibition of yap/taz activity in mouse ovaries. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:15346. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-41954-0

40. Chen M, Liu Y, Zuo M, Guo C, Du Y, Xu H, et al. Nedd8 enhances hippo signaling by mediating yap1 neddylation. J Biol Chem. (2024) 300:107512. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107512

41. de Andrade LG, Portela VM, Dos Santos EC, Aires KV, Ferreira R, Missio D, et al. Fsh regulates yap-tead transcriptional activity in bovine granulosa cells to allow the future dominant follicle to exert its augmented estrogenic capacity. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23(22):14160. doi: 10.3390/ijms232214160

42. Mizutani T, Orisaka M, Kawabe S, Morichika R, Uesaka M, and Yoshida Y. Yap/taz-tead is a novel transcriptional regulator of genes encoding steroidogenic enzymes in rat granulosa cells and kgn cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2023) 559:111808. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2022.111808

43. Koch J, Portela VM, Dos Santos EC, Missio D, de Andrade LG, da Silva Z, et al. The hippo pathway effectors yap and taz interact with egf-like signaling to regulate expansion-related events in bovine cumulus cells in vitro. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2022) 39:481–92. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02384-x

44. Lalonde-Larue A, Boyer A, Dos Santos EC, Boerboom D, Bernard DJ, and Zamberlam G. The hippo pathway effectors yap and taz regulate lh release by pituitary gonadotrope cells in mice. Endocrinology. (2022) 163(1):bqab238. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab238

45. Sun T and Diaz FJ. Ovulatory signals alter granulosa cell behavior through yap1 signaling. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. (2019) 17:113. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0552-1

46. Dos Santos EC, Lalonde-Larue A, Antoniazzi AQ, Barreta MH, Price CA, Dias Gonçalves PB, et al. Yap signaling in preovulatory granulosa cells is critical for the functioning of the egf network during ovulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2022) 541:111524. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111524

47. Godin P, Tsoi MF, Morin M, Gévry N, and Boerboom D. The granulosa cell response to luteinizing hormone is partly mediated by yap1-dependent induction of amphiregulin. Cell Commun Signal. (2022) 20:72. doi: 10.1186/s12964-022-00843-1

48. Huang Z, Xu T, Liu C, Wu H, Weng L, Cai J, et al. Correlation between ovarian follicular development and hippo pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Ovarian Res. (2024) 17:14. doi: 10.1186/s13048-023-01305-z

49. Ji SY, Liu XM, Li BT, Zhang YL, Liu HB, Zhang YC, et al. The polycystic ovary syndrome-associated gene yap1 is regulated by gonadotropins and sex steroid hormones in hyperandrogenism-induced oligo-ovulation in mouse. Mol Hum Reprod. (2017) 23:698–707. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gax046

50. Dewailly D, Robin G, Peigne M, Decanter C, Pigny P, and Catteau-Jonard S. Interactions between androgens, fsh, anti-müllerian hormone and estradiol during folliculogenesis in the human normal and polycystic ovary. Hum Reprod Update. (2016) 22:709–24. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw027

51. Jiang LL, Xie JK, Cui JQ, Wei D, Yin BL, Zhang YN, et al. Promoter methylation of yes-associated protein (Yap1) gene in polycystic ovary syndrome. Med (Baltimore). (2017) 96:e5768. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000005768

52. Jin J, Ruan X, Hua L, Tian X, Li Y, Wang L, et al. Prevalence of diminished ovarian reserve in chinese women with polycystic ovary syndrome and sensitive diagnostic parameters. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2017) 33:694–7. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1310838

53. Gomes VA, Vieira CS, Jacob-Ferreira AL, Belo VA, Soares GM, Fernandes JB, et al. Imbalanced circulating matrix metalloproteinases in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Cell Biochem. (2011) 353:251–7. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0793-6

54. Chen Z, Wei H, Zhao X, Xin X, Peng L, Ning Y, et al. Metformin treatment alleviates polycystic ovary syndrome by decreasing the expression of mmp-2 and mmp-9 via H19/mir-29b-3p and akt/mtor/autophagy signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. (2019) 234:19964–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28594

55. Hassani F, Oryan S, Eftekhari-Yazdi P, Bazrgar M, Moini A, Nasiri N, et al. Downregulation of extracellular matrix and cell adhesion molecules in cumulus cells of infertile polycystic ovary syndrome women with and without insulin resistance. Cell J. (2019) 21:35–42. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2019.5576

56. Shen H, Liang Z, Zheng S, and Li X. Pathway and network-based analysis of genome-wide association studies and rt-pcr validation in polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Mol Med. (2017) 40:1385–96. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3146

57. Lunding SA, Andersen AN, Hardardottir L, Olesen H, Kristensen SG, Andersen CY, et al. Hippo signaling, actin polymerization, and follicle activation in fragmented human ovarian cortex. Mol Reprod Dev. (2020) 87:711–9. doi: 10.1002/mrd.23353

58. Cheng Y, Feng Y, Jansson L, Sato Y, Deguchi M, Kawamura K, et al. Actin polymerization-enhancing drugs promote ovarian follicle growth mediated by the hippo signaling effector yap. FASEB J. (2015) 29:2423–30. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-267856

59. Ahmed TA, Ahmed SM, El-Gammal Z, Shouman S, Ahmed A, Mansour R, et al. Oocyte aging: the role of cellular and environmental factors and impact on female fertility. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2020) 1247:109–23. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_456

60. Patil K, Hinduja I, and Mukherjee S. Alteration in angiogenic potential of granulosa-lutein cells and follicular fluid contributes to luteal defects in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. (2021) 36:1052–64. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa351

61. Huang L and Wang L. Association between vegf gene polymorphisms (11 sites) and polycystic ovary syndrome risk. Biosci Rep. (2020) 40(3):BSR20191691. doi: 10.1042/bsr20191691

62. Kim J, Kim YH, Kim J, Park DY, Bae H, Lee DH, et al. Yap/taz regulates sprouting angiogenesis and vascular barrier maturation. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:3441–61. doi: 10.1172/jci93825

63. Wang X, Freire Valls A, Schermann G, Shen Y, Moya IM, Castro L, et al. Yap/taz orchestrate vegf signaling during developmental angiogenesis. Dev Cell. (2017) 42:462–78.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.08.002

64. Al-Saleh I. The relationship between urinary phthalate metabolites and polycystic ovary syndrome in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: nested case-control study. Chemosphere. (2022) 286:131495. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131495

65. Alenazi A, Virk P, Almoqhem R, Alsharidah A, Al-Ghadi MQ, Aljabr W, et al. The efficacy of hispidin and magnesium nanoparticles against zearalenone-induced fungal toxicity causing polycystic ovarian syndrome in rats. Biomedicines. (2024) 12(5):943. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12050943

66. Xu K, Wang Y, Gao X, Wei Z, Han Q, Wang S, et al. Polystyrene microplastics and di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate co-exposure: implications for female reproductive health. Environ Sci Ecotechnol. (2024) 22:100471. doi: 10.1016/j.ese.2024.100471

67. Xu X, Zhang X, Chen J, Du X, Sun Y, Zhan L, et al. Exploring the molecular mechanisms by which per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances induce polycystic ovary syndrome through in silico toxicogenomic data mining. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2024) 275:116251. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.116251

68. Zhang Y, Martin L, Mustieles V, Ghaly M, Archer M, Sun Y, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposure is associated with polycystic ovary syndrome risk among women attending a fertility clinic. Sci Total Environ. (2024) 950:175313. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175313

69. Clark KL, George JW, Hua G, and Davis JS. Perfluorooctanoic acid promotes proliferation of the human granulosa cell line hgrc1 and alters expression of cell cycle genes and hippo pathway effector yap1. Reprod Toxicol. (2022) 110:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2022.03.011

70. Clark KL, George JW, and Davis JS. Adolescent exposure to a mixture of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (Pfas) depletes the ovarian reserve, increases ovarian fibrosis, and alters the hippo pathway in adult female mice. Toxicol Sci. (2024) 202:36–49. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfae103

71. Wu H, Liu Q, Yang N, and Xu S. Polystyrene-microplastics and dehp co-exposure induced DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and necroptosis of ovarian granulosa cells in mice by promoting ros production. Sci Total Environ. (2023) 871:161962. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161962

72. Tian Y, Zhang MY, Zhao AH, Kong L, Wang JJ, Shen W, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling provides insights into the toxic effects of zearalenone exposure on primordial follicle assembly. Theranostics. (2021) 11:5197–213. doi: 10.7150/thno.58433

73. Li J, Zheng R, Shen Y, Zhuo Y, Lu L, Song J, et al. Jiawei qi gong wan improves liver fibrosis and inflammation in pcos mice via the akt2-foxo1 and yap/taz signaling pathways. Phytomedicine. (2025) 136:156294. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156294

74. Vassilatou E, Vassiliadi DA, Salambasis K, Lazaridou H, Koutsomitopoulos N, Kelekis N, et al. Increased prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in premenopausal women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Endocrinol. (2015) 173:739–47. doi: 10.1530/eje-15-0567

75. Alhermi A, Perks H, Nigi V, Altahoo N, Atkin SL, and Butler AE. The role of the liver in the pathophysiology of pcos: A literature review. Biomolecules. (2025) 15(1):51. doi: 10.3390/biom15010051

76. Shu Z, Gao Y, Zhang G, Zhou Y, Cao J, Wan D, et al. A functional interaction between hippo-yap signalling and srebps mediates hepatic steatosis in diabetic mice. J Cell Mol Med. (2019) 23:3616–28. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14262

77. Shu ZP, Yi GW, Deng S, Huang K, and Wang Y. Hippo pathway cooperates with chrebp to regulate hepatic glucose utilization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2020) 530:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.06.105

78. Lu J, Gao Y, Gong Y, Yue Y, Yang Y, Xiong Y, et al. Lycium barbarum L. Balanced intestinal flora with yap1/fxr activation in drug-induced liver injury. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 130:111762. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111762

79. Glueck CJ and Goldenberg N. Characteristics of obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, treatment, and genetics. Metabolism. (2019) 92:108–20. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.002

80. Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, and Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. (2022) 185:419–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.016

81. Wang L, Wang S, Shi Y, Li R, Günther S, Ong YT, et al. Yap and taz protect against white adipocyte cell death during obesity. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:5455. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19229-3

82. Lee GJ, Kim YJ, Park B, Yim S, Park C, Roh H, et al. Yap-dependent wnt5a induction in hypertrophic adipocytes restrains adiposity. Cell Death Dis. (2022) 13:407. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04847-0

83. Shen H, Huang X, Zhao Y, Wu D, Xue K, Yao J, et al. The hippo pathway links adipocyte plasticity to adipose tissue fibrosis. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:6030. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33800-0

84. Leung KL, Sanchita S, Pham CT, Davis BA, Okhovat M, Ding X, et al. Dynamic changes in chromatin accessibility, altered adipogenic gene expression, and total versus de novo fatty acid synthesis in subcutaneous adipose stem cells of normal-weight polycystic ovary syndrome (Pcos) women during adipogenesis: evidence of cellular programming. Clin Epigenet. (2020) 12:181. doi: 10.1186/s13148-020-00970-x

85. Liang J, Lan J, Li M, and Wang F. Associations of leptin receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma polymorphisms with polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab. (2019) 75:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000500996

86. Lorthongpanich C, Thumanu K, Tangkiettrakul K, Jiamvoraphong N, Laowtammathron C, Damkham N, et al. Yap as a key regulator of adipo-osteogenic differentiation in human mscs. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2019) 10:402. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1494-4

87. Oliver-De La Cruz J, Nardone G, Vrbsky J, Pompeiano A, Perestrelo AR, Capradossi F, et al. Substrate mechanics controls adipogenesis through yap phosphorylation by dictating cell spreading. Biomaterials. (2019) 205:64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.009

88. Zhang Y, Fu J, Li C, Chang Y, Li X, Cheng H, et al. Omentin-1 induces mechanically activated fibroblasts lipogenic differentiation through pkm2/yap/pparγ Pathway to promote lung fibrosis resolution. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2023) 80:308. doi: 10.1007/s00018-023-04961-y

89. Houston EJ and Templeman NM. Reappraising the relationship between hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in pcos. J Endocrinol. (2025) 265(2):e240269. doi: 10.1530/joe-24-0269

90. Han DJ, Aslam R, Misra PS, Chiu F, Ojha T, Chowdhury A, et al. Disruption of adipocyte yap improves glucose homeostasis in mice and decreases adipose tissue fibrosis. Mol Metab. (2022) 66:101594. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101594

91. Zhao H, Zhang J, Cheng X, Nie X, and He B. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome across various tissues: an updated review of pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Ovarian Res. (2023) 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s13048-022-01091-0

92. Sylow L, Tokarz VL, Richter EA, and Klip A. The many actions of insulin in skeletal muscle, the paramount tissue determining glycemia. Cell Metab. (2021) 33:758–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.03.020

93. Watt KI, Henstridge DC, Ziemann M, Sim CB, Montgomery MK, Samocha-Bonet D, et al. Yap regulates skeletal muscle fatty acid oxidation and adiposity in metabolic disease. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:2887. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23240-7

94. Wang C, Jeong K, Jiang H, Guo W, Gu C, Lu Y, et al. Yap/taz regulates the insulin signaling via irs1/2 in endometrial cancer. Am J Cancer Res. (2016) 6:996–1010.

95. Shen Q, Bi H, Yu F, Fan L, Zhu M, Jia X, et al. Nontargeted metabolomic analysis of skeletal muscle in a dehydroepiandrosterone-induced mouse model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Reprod Dev. (2019) 86:370–8. doi: 10.1002/mrd.23111

96. DeChick A, Hetz R, Lee J, and Speelman DL. Increased skeletal muscle fiber cross-sectional area, muscle phenotype shift, and altered insulin signaling in rat hindlimb muscles in a prenatally androgenized rat model for polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21(21):7918. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217918

97. Skarra DV, Hernández-Carretero A, Rivera AJ, Anvar AR, and Thackray VG. Hyperandrogenemia induced by letrozole treatment of pubertal female mice results in hyperinsulinemia prior to weight gain and insulin resistance. Endocrinology. (2017) 158:2988–3003. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1898

98. Misra S, Gada J, Dhole C, Varthakavi P, and Bhagwat N. Comparative study of insulin sensitivity and resistance and their correlation with androgens in lean and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci. (2024) 31:754–63. doi: 10.1007/s43032-023-01374-x

99. Halloran KM, Saadat N, Pallas B, Vyas AK, Sargis R, and Padmanabhan V. Developmental programming: testosterone excess masculinizes female pancreatic transcriptome and function in sheep. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2024) 588:112234. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2024.112234

100. Jackson IJ, Puttabyatappa M, Anderson M, Muralidharan M, Veiga-Lopez A, Gregg B, et al. Developmental programming: prenatal testosterone excess disrupts pancreatic islet developmental trajectory in female sheep. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2020) 518:110950. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110950

101. Ramaswamy S, Grace C, Mattei AA, Siemienowicz K, Brownlee W, MacCallum J, et al. Developmental programming of polycystic ovary syndrome (Pcos): prenatal androgens establish pancreatic islet α/β Cell ratio and subsequent insulin secretion. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:27408. doi: 10.1038/srep27408

102. Mamidi A, Prawiro C, Seymour PA, de Lichtenberg KH, Jackson A, Serup P, et al. Mechanosignalling via integrins directs fate decisions of pancreatic progenitors. Nature. (2018) 564:114–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0762-2

103. Shin E, Kwon TY, Cho Y, Kim Y, Shin JH, and Han YM. Ecm architecture-mediated regulation of β-cell differentiation from hescs via hippo-independent yap activation. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. (2023) 9:680–92. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c01054

104. Wu Y, Qin K, Xu Y, Rajhans S, Vo T, Lopez KM, et al. Hippo pathway-mediated yap1/taz inhibition is essential for proper pancreatic endocrine specification and differentiation. Elife. (2024) 13:e84532. doi: 10.7554/eLife.84532

105. Rosado-Olivieri EA, Anderson K, Kenty JH, and Melton DA. Yap inhibition enhances the differentiation of functional stem cell-derived insulin-producing β Cells. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1464. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09404-6

106. George NM, Boerner BP, Mir SU, Guinn Z, and Sarvetnick NE. Exploiting expression of hippo effector, yap, for expansion of functional islet mass. Mol Endocrinol. (2015) 29:1594–607. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1375

107. Yuan T, Rafizadeh S, Azizi Z, Lupse B, Gorrepati KDD, Awal S, et al. Proproliferative and antiapoptotic action of exogenously introduced yap in pancreatic β Cells. JCI Insight. (2016) 1:e86326. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86326

108. Ardestani A and Maedler K. Mst1 deletion protects β-cells in a mouse model of diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. (2022) 12:7. doi: 10.1038/s41387-022-00186-3

109. Rudnicka E, Suchta K, Grymowicz M, Calik-Ksepka A, Smolarczyk K, Duszewska AM, et al. Chronic low grade inflammation in pathogenesis of pcos. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22(7):3789. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073789

110. Rostamtabar M, Esmaeilzadeh S, Tourani M, Rahmani A, Baee M, Shirafkan F, et al. Pathophysiological roles of chronic low-grade inflammation mediators in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Cell Physiol. (2021) 236:824–38. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29912

111. Feng Y, Tang Z, and Zhang W. The role of macrophages in polycystic ovarian syndrome and its typical pathological features: A narrative review. BioMed Pharmacother. (2023) 167:115470. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115470

112. Mia MM, Cibi DM, Abdul Ghani SAB, Song W, Tee N, Ghosh S, et al. Yap/taz deficiency reprograms macrophage phenotype and improves infarct healing and cardiac function after myocardial infarction. PloS Biol. (2020) 18:e3000941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000941

113. Wang D, Zhang Y, Xu X, Wu J, Peng Y, Li J, et al. Yap promotes the activation of nlrp3 inflammasome via blocking K27-linked polyubiquitination of nlrp3. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:2674. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22987-3

114. Yang K, Xu J, Fan M, Tu F, Wang X, Ha T, et al. Lactate suppresses macrophage pro-inflammatory response to lps stimulation by inhibition of yap and nf-κb activation via gpr81-mediated signaling. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:587913. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.587913

115. Roh KH, Lee Y, Yoon JH, Lee D, Kim E, Park E, et al. Traf6-mediated ubiquitination of mst1/stk4 attenuates the tlr4-nf-κb signaling pathway in macrophages. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2021) 78:2315–28. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03650-4

116. Yang Y, Ni M, Zong R, Yu M, Sun Y, Li J, et al. Targeting notch1-yap circuit reprograms macrophage polarization and alleviates acute liver injury in mice. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 15:1085–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2023.01.002

117. Liu M, Yan M, Lv H, Wang B, Lv X, Zhang H, et al. Macrophage K63-linked ubiquitination of yap promotes its nuclear localization and exacerbates atherosclerosis. Cell Rep. (2020) 32:107990. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107990

118. Zhou X, Li W, Wang S, Zhang P, Wang Q, Xiao J, et al. Yap aggravates inflammatory bowel disease by regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization and gut microbial homeostasis. Cell Rep. (2019) 27:1176–89.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.028

119. An Y, Tan S, Zhang P, Yang J, Wang K, Zheng R, et al. Inactivation of mst1/2 controls macrophage polarization to affect macrophage-related disease via yap and non-yap mechanisms. Int J Biol Sci. (2024) 20:1004–23. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.87057

120. Zakerinasab F, Behfar Q, Al Saraireh TH, Naziri M, Yaghoobpoor S, Deravi N, et al. Unilateral or bilateral laparoscopic ovarian drilling in polycystic ovary syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. (2025) 14:14–23. doi: 10.4103/gmit.gmit_89_23

121. Bordewijk EM, Ng KYB, Rakic L, Mol BWJ, Brown J, Crawford TJ, et al. Laparoscopic ovarian drilling for ovulation induction in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 2:Cd001122. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001122.pub5

122. Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, Deguchi M, Sato Y, Takae S, et al. Hippo signaling disruption and akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2013) 110:17474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312830110

123. Grosbois J and Demeestere I. Dynamics of pi3k and hippo signaling pathways during in vitro human follicle activation. Hum Reprod. (2018) 33:1705–14. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dey250

124. Zhu P, Bi X, Su D, Li X, Chen Y, Song Z, et al. Transcription repression of estrogen receptor alpha by ghrelin/gq/11/yap signaling in granulosa cells promotes polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Cell. (2024) 37:1663–78. doi: 10.1007/s13577-024-01127-1

125. Zhang P, Pan Y, Wu S, He Y, Wang J, Chen L, et al. N-3 pufa promotes ferroptosis in pcos gcs by inhibiting yap1 through activation of the hippo pathway. Nutrients. (2023) 15(8):1927. doi: 10.3390/nu15081927

126. Teede HJ, Tay CT, Laven JJE, Dokras A, Moran LJ, Piltonen TT, et al. Recommendations from the 2023 international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. (2023) 189:G43–g64. doi: 10.1093/ejendo/lvad096

127. Gao Z, Daquinag AC, Su F, Snyder B, and Kolonin MG. Pdgfrα/pdgfrβ Signaling balance modulates progenitor cell differentiation into white and beige adipocytes. Development. (2018) 145(1):dev155861. doi: 10.1242/dev.155861

128. Zhang W, Xu J, Li J, Guo T, Jiang D, Feng X, et al. The tea domain family transcription factor tead4 represses murine adipogenesis by recruiting the cofactors vgll4 and ctbp2 into a transcriptional complex. J Biol Chem. (2018) 293:17119–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003608

129. Zhou Q, Tang H, Wang Y, Hua Y, Ouyang X, and Li L. Hyperoside mitigates pcos-associated adipogenesis and insulin resistance by regulating ncoa2-mediated ppar-Γ Ubiquitination and degradation. Life Sci. (2025) 364:123417. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2025.123417

130. Cho YK, Son Y, Saha A, Kim D, Choi C, Kim M, et al. Stk3/stk4 signalling in adipocytes regulates mitophagy and energy expenditure. Nat Metab. (2021) 3:428–41. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00362-2

131. Li Y, Du J, Zhu E, Zhang J, Han J, Zhao W, et al. Liraglutide suppresses proliferation and induces adipogenic differentiation of 3t3-L1 cells via the hippo-yap signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. (2018) 17:4499–507. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8438

132. El Ouarrat D, Isaac R, Lee YS, Oh DY, Wollam J, Lackey D, et al. Taz is a negative regulator of pparγ Activity in adipocytes and taz deletion improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance. Cell Metab. (2020) 31:162–73.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.10.003

133. Stener-Victorin E, Eriksson G, Mohan Shrestha M, Rodriguez Paris V, Lu H, Banks J, et al. Proteomic analysis shows decreased type I fibers and ectopic fat accumulation in skeletal muscle from women with pcos. Elife. (2024) 12:RP87592. doi: 10.7554/eLife.87592

134. Nezhad FY, Riermeier A, Schönfelder M, Becker L, de Angelis MH, and Wackerhage H. Skeletal muscle phenotyping of hippo gene-mutated mice reveals that lats1 deletion increases the percentage of type I muscle fibers. Transgenic Res. (2022) 31:227–37. doi: 10.1007/s11248-021-00293-4

135. Salek M, Clark CCT, Taghizadeh M, and Jafarnejad S. N-3 Fatty Acids as Preventive and Therapeutic Agents in Attenuating Pcos Complications. Excli J. (2019) 18:558–75. doi: 10.17179/excli2019-1534

136. Wang H, Yung MM, Xuan Y, Chen F, Chan W, Siu MK, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids promote M2-like tam deposition via dampening rhoa-yap1 signaling in the ovarian cancer microenvironment. Exp Hematol Oncol. (2024) 13:90. doi: 10.1186/s40164-024-00558-8

137. Spremović Rađenović S, Pupovac M, Andjić M, Bila J, Srećković S, Gudović A, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and pathophysiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Nafld) in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (Pcos). Biomedicines. (2022) 10(1):131. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10010131

138. Macut D, Tziomalos K, Božić-Antić I, Bjekić-Macut J, Katsikis I, Papadakis E, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with insulin resistance and lipid accumulation product in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. (2016) 31:1347–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew076

139. Vidal-Cevallos P, Mijangos-Trejo A, Uribe M, and Tapia NC. The interlink between metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2023) 52:533–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2023.01.005

140. Li C, Xue Y, Liu Y, Zheng K, Gao Y, Gong Y, et al. Hepatocyte-specific yap1 knockout maintained the liver homeostasis of lipid metabolism in mice. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2024) 17:3197–214. doi: 10.2147/dmso.S472778

141. Li Y, Nie JJ, Yang Y, Li J, Li J, Wu X, et al. Redox-unlockable nanoparticle-based mst1 delivery system to attenuate hepatic steatosis via the ampk/srebp-1c signaling axis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2022) 14:34328–41. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c05889

142. Li Y, Luan Y, Li J, Song H, Li Y, Qi H, et al. Exosomal mir-199a-5p promotes hepatic lipid accumulation by modulating mst1 expression and fatty acid metabolism. Hepatol Int. (2020) 14:1057–74. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10096-0

143. Wang W, He Y, and Liu Q. Parthenolide plays a protective role in the liver of mice with metabolic dysfunction−Associated fatty liver disease through the activation of the hippo pathway. Mol Med Rep. (2021) 24(1):487. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2021.12126

144. Cai JH, Sun YT, and Bao S. Hucmscs-exosomes containing mir-21 promoted estrogen production in ovarian granulosa cells via lats1-mediated phosphorylation of loxl2 and yap. Gen Comp Endocrinol. (2022) 321-322:114015. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2022.114015

145. Sun B, Ma Y, Li L, Hu L, Wang F, Zhang Y, et al. Factors associated with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (Ohss) severity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing ivf/icsi. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:615957. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.615957

Keywords: Hippo signaling pathway, polycystic ovary syndrome, YAP, TAZ, ovary, lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, inflammation

Citation: Wen J, Cheng G, Zhang Y and Liu S (2025) Hippo signaling pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 16:1623143. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2025.1623143

Received: 05 May 2025; Accepted: 15 September 2025;

Published: 06 October 2025.

Edited by:

Duan Xing, Southeast University, ChinaReviewed by:

Fahimeh Ramezani Tehrani, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, IranShaobo Li, The First Affiliated Hospital of Henan University of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Wen, Cheng, Zhang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Zhang, cGVuZXl5YW5Ad2h1LmVkdS5jbg==; Su Liu, c3VubnlzdWUwMzA5QDE2My5jb20=

Jiahui Wen1

Jiahui Wen1 Su Liu

Su Liu