Abstract

Objective:

BRAF V600E mutation is the most common and clinically significant genetic alteration in advanced thyroid cancers. This study provides real-world experience with BRAF and MEK inhibitors other than dabrafenib and trametinib in the treatment of advanced thyroid cancers harboring this mutation.

Methods:

A case series of four patients with advanced thyroid cancer (three papillary and one anaplastic) treated with various BRAF and MEK inhibitors. All patients had confirmed BRAF V600E mutation.

Results:

Among three patients treated with BRAF/MEK inhibitors for radioiodine refractory metastatic PTC, and one patient with ATC, all (100%) demonstrated a partial response (PR) during therapy, yielding an overall response rate (ORR) of 100%. Stable disease was observed in multiple treatment phases, contributing to a high overall disease control rate. Three patients had disease-related death, while one remained under treatment at last follow-up. The course of treatment was complicated by significant toxicities, leading to dose reductions or treatment discontinuations. Despite initial responses, all cases eventually progressed, necessitating sequential treatment strategies. Overall survival ranged from 6.0 to 25.3 months, with a median follow-up of 18.3 months since the initiation of BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

Conclusions:

This case series highlights the potential benefits and challenges of targeted therapies in advanced thyroid cancer. While BRAF and MEK inhibitors offer new treatment options, toxicity management and the development of resistance remain significant hurdles. The limited FDA-approved options for BRAF V600E-positive thyroid cancer compared to melanoma underscore the need for further research to optimize and expand treatment strategies.

Introduction

Thyroid cancer represents the most common endocrine malignancy, with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) accounting for approximately 85% of cases (1, 2). While most PTCs have an excellent prognosis, a subset of patients develop aggressive, treatment-refractory disease. At the other end of the spectrum, anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) stands as one of the most lethal human malignancies, with a historical median survival of only 3–5 months (3, 4).

The somatic BRAFV600E mutation is present in 37%–60% of PTC, particularly among the tall-cell variants, and to a similar extent in ATC (1–3). The presence of BRAFV600E mutation is linked to dysregulation of the sodium-iodide symporter, reducing the capacity of tumor cells to absorb radioiodine (RAI) and consequently, leading to RAI resistance (4). Patients with BRAFV600E-positive tumors are more likely to exhibit a more aggressive tumor behavior and potentially higher cancer-related mortality, requiring systemic therapies for recurrent or metastatic disease (5, 6).

Recent advances in molecular profiling have revolutionized our understanding of thyroid cancer biology and opened new avenues for targeted therapies (5–7). The identification of driver mutations, particularly the BRAF V600E mutation, has led to the development of targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors with a promising therapeutic potential in both differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers (7–9), extending the overall survival in ATC to 80% at 12 months (8).

To date, the only BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimen approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of ATC is the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib (10). This approval was initially based on findings from the phase II ROAR basket trial, which demonstrated promising clinical activity, with subsequent research further supporting its efficacy (11, 12). Despite these encouraging results, dabrafenib and trametinib remain the sole labeled combination approved for ATC, in contrast to melanoma treatment, where other BRAF and MEK inhibitor combinations, such as vemurafenib–cobimetinib and encorafenib–binimetinib, are available (13–15). These alternative regimens exhibit slightly different side-effect profiles, which may enable clinicians to modify therapy in the presence of severe adverse events, potentially reducing the need for dose reductions or treatment discontinuation.

These cases illustrate the complexity of managing advanced thyroid cancer in the era of precision medicine, emphasizing both the benefits and challenges of targeted therapies (13, 16–18). Prior treatments, tumor mutation profiles, and outcomes compared with previously reported cohorts are summarized in Table 1, and sequential therapeutic strategies are outlined in Figure 1. This series highlights the real-world use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors, management of treatment-related toxicities, and the need for ongoing research to optimize personalized care and improve patient outcomes (14, 23).

Table 1

| Case | N | Age (years) | Variant | Mutation profile | Prior treatments before BRAF + MEK inhibitors | BRAF/MEK inhibitor used | PFS (months) | Dose modification/discontinuation | Grade 3-4 adverse reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 1 | 68 | ATC | BRAF V600E, ATM, TP53 | None | D + T; E + B | 2.5 | Discontinuation | Yes |

| Case 2 | 1 | 67 | Tall cell variant PTC | BRAF V600E, TERT, VHL, MSS, TMB 0 | Surgery; RAI × 2; radiotherapy; lenvatinib | D + T; E + B | 10 | Dose reduction; discontinuation | Yes |

| Case 3 | 1 | 83 | Tall cell variant PTC | BRAF V600E, MSS, TMB 3.78 | Surgery; RAI × 3 | D + T; E + B | 17 | Dose reduction; discontinuation | Yes |

| Case 4 | 1 | 76 | Tall cell variant PTC | BRAF V600E, TERT, MEN1 LOF, TMB 1.6 | Surgery; RAI × 1 | D + T; E + B; V + C | 18 | Dose reduction; discontinuation | Yes |

| Brose MS et al. (7) | 51 | 66 (55-74) | PTC | BRAF V600E | VEGFR inhibitor; chemotherapy | V | 18.4 | Dose reduction (53%); discontinuation (77%) | 66.7% |

| Subbiah V et al. (8) | 16 | 72 (56-85) | ATC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; radiotherapy; chemotherapy; small-molecule targeted therapy | D + T | 12-months PFS estimate 79% | Dose reduction (30%); discontinuation (60.5%) | 42% |

| Subbiah V et al. (12) | 36 | 71 (47-85) | ATC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; radiotherapy; RAI; small-molecule targeted therapy; immunotherapy | D + T | 6.7 | Dose reduction (78%); discontinuation (17%) | 56% |

| Violetis O et al. (19) | 1 | 45 | PDTC, Hobnail, and tall-cell PTC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; RAI × 2; lenvatinib + sorafenib; radiotherapy | D + T | 24 | Discontinuation | Yes |

| Shimoi T et al. (20) | 15 | 56.5 (16-77) | 10 PTC; 5 ATC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; radiotherapy | D + T | 5.7 | Dose reduction (20%); discontinuation (6%) | 45.6% |

| Jeon Y et al. (21) | 27 | 73 (24-84) | 19 PTC; 8 ATC/PDTC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; RAI; lenvatinib + pembrolizumab; sorafenib; chemotherapy | D + T | 21.7 | Dose reduction (48.1%); discontinuation (81.5%) | 44.4% |

| Tahara M et al. (22) | 22 | 68 (50-77) | 17 DTC; 5 ATC | BRAF V600E | Surgery; RAI; radiotherapy; lenvatinib; sorafenib; VEGFR inhibitor | E + B | 12-months PFS estimate 78.8% | Dose reduction (13.6%); discontinuation (18.2%) | 27.3% |

Prior treatments, tumor mutation profiles, and outcomes compared with previously reported cohorts.

PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; DTC, differentiated thyroid carcinoma; BRAF V600E, B-Raf proto-oncogene mutation at valine 600; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; TP53, tumor protein p53; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; VHL, Von Hippel-Lindau; MSS, microsatellite stable; TMB, tumor mutational burden; RAI, radioactive iodine; LOF, loss of function; PFS, progression-free survival; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; D + T, dabrafenib + trametinib; E + B, encorafenib + binimetinib; V, vemurafenib; V + C, vemurafenib + cobimetinib.

Figure 1

Swimmer plot showing the tumor response timeline since initiation of BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment. Each row represents an individual patient (cases 1-4). Colored bars denote different systemic therapies administered.

Methods

This case series presents four patients with advanced thyroid cancer: three with PTC and one with ATC, all harboring the BRAF V600E mutation diagnosed using next-generation sequencing (NGS) by The Ion Torrent™ Oncomine™ Dx Express Test in all cases but case 2 in which FoundationOne®CDx was used.

Disease progression was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) ver. 1.1 (15). Treatment-related adverse events were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) ver. 5.0 (24). The baseline characteristics, treatment history, efficacy, and safety outcomes were evaluated. The study was approved by the local IRB (TLV-0197-25) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with informed consent waived due to its retrospective design.

Cases presentation

Case 1

A 68-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer presented in April 2024 with a painful neck mass with cutaneous infiltration (Figure 2). Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed an infiltrative mass extending from the left thyroid lobe to the carotid sheath, displacing the internal jugular vein (IJV) laterally, with a posterior invasion into the larynx and prevertebral fascia. Suspicious cervical lymphadenopathy was also noted. Initial fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy was inconclusive between poorly differentiated thyroid cancer and medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). However, subsequent fine-needle biopsy confirmed BRAF-V600E-mutated ATC. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) demonstrated locally advanced disease without distant metastasis.

Figure 2

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma presenting as a neck mass with invasion of the overlying skin. Cutaneous involvement enabled clinical monitoring of the tumor’s response to treatment.

She was started on dabrafenib (150 mg twice daily) and trametinib (2 mg once daily), resulting within days in clinical improvement characterized by reduced pain and decreased neck swelling; however, 1 month after treatment initiation, she developed grade 3 encephalopathy that required hospitalization. She presented with fever and an acute confusional state and underwent an extensive diagnostic workup, including lumbar puncture; cerebrospinal fluid analysis, cultures, and PCR tests showed negative results. Discontinuation of therapy led to restoration of her baseline cognitive function. To maintain the therapeutic response that was previously achieved with BRAF and MEK inhibition, she was subsequently started on encorafenib (450 mg once daily) and binimetinib (45 mg once daily) for 4 weeks, but this regimen was discontinued due to disease progression. The patient was then reinitiated on dabrafenib and trametinib, resulting in clinical improvement that persisted for several weeks.

Due to unresectable disease with tracheal infiltration, the patient underwent definitive chemoradiation to the neck, receiving a total dose of 66 Gy in combination with weekly paclitaxel, resulting in a satisfactory clinical and radiographic response. Subsequently, she underwent salvage surgery, which included total thyroidectomy and left neck dissection of levels II–V, with resection of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, IJV, sternocleidomastoid muscle, strap muscles, overlying skin, and shaving of tumor from the laryngeal cartilages and esophageal adventitia. Reconstruction was performed using a pectoralis major flap.

Histopathological examination revealed infiltrating ATC with 50% necrosis, with clean pathological margins. However, 5 weeks postoperatively, the patient developed tracheal necrosis with formation of a tracheocutaneous fistula. Immunohistochemistry of final pathology showed a combined positive score (CPS) of 80 for which she was offered treatment with anti-PD-1 and lenvatinib, which had shown to have some modest benefits as a second-line regimen (25); however, the patient declined further treatment and succumbed to her disease 7 weeks later.

Case 2

A 67-year-old woman with a history of radiotherapy treatment due to meningioma underwent total thyroidectomy in 2008 for multifocal papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), followed by postoperative RAI therapy (150 mCi). Between 2011 and 2021, she underwent multiple neck dissections for recurrent locoregional disease, detected on sonography, RAI uptake scans, and following PET-CT scans, accompanied by elevated thyroglobulin antibody levels.

In 2021, pathology from a recurrence revealed tall cell variant PTC with mutations in BRAF-V600E and TERT. The disease involved the right recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and was carefully dissected off the internal carotid artery during her most recent surgery. She subsequently received volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) and achieved clinical and radiographic stability for 18 months.

In August 2022, a PET-CT demonstrated new metastases in the lungs and ribs. NGS confirmed positivity for BRAF-V600E, TERT, VHL, microsatellite stability (MSS), and a tumor mutational burden (TMB) of 0. The patient was initiated on lenvatinib (14 mg daily). After 2 months of treatment, a dose reduction to 10 mg daily was necessitated by grade 3 mucositis. Treatment was ultimately discontinued after 14 months of stable disease due to progression, with the development of new skeletal metastases in July 2025.

Treatment with dabrafenib–trametinib was initiated promptly but discontinued early due to severe hypersensitivity with angioedema, rash, and tongue edema requiring corticosteroids and antihistamines. The patient was transitioned to encorafenib–binimetinib with a gradual dose-escalation protocol, starting at 50% of the target dose. On the half-dose regimen, pleural effusion resolved, but escalation was withheld due to weakness and hospitalization for diverticulitis.

Over the course of 1 year, treatment resulted in both clinical and radiological improvement. Subsequently, the patient experienced further local and distant disease progression, including the development of a D5 vertebral metastasis causing spinal canal narrowing and a cervical mass compressing the internal jugular vein (Figure 3). This necessitated initiation of cabozantinib at 40 mg daily (reduced dose, adjusted for her frail condition). Despite this intervention, the disease continued to progress, and the patient died 3 months later.

Figure 3

Serial PET-CT images demonstrate the patient’s radiological response and subsequent disease progression. Initial scans [(A), October 2023] show radiological improvement including in the left femur metastasis (arrowhead), following 1 year of therapy on a reduced-dose regimen, coinciding with development and gradual resolution of pleural effusion (asterisk). Later images [(B), April 2024; (C), July 2024] depict disease progression, including the emergence of a D5 vertebral metastasis with associated spinal canal narrowing (circle) and a cervical soft-tissue mass compressing the internal jugular vein. These findings prompted the initiation of cabozantinib therapy. Despite treatment, further progression was observed on follow-up imaging.

Case 3

An 83-year-old woman underwent a total thyroidectomy and neck dissection levels II–VI in 2012 for T3N1bM0 PTC. Due to recurrent disease, she received three courses of RAI therapy of 150 mCi each in 2012, 2016, and 2019. In 2022, due radioiodine refractory disease and evidence of mediastinal metastasis, she underwent a selective left neck dissection (level V), with pathology revealing 5 out of 16 positive lymph nodes with extra-capsular extension (ENE). NGS demonstrated a BRAF-V600E mutation.

The patient was initially started on dabrafenib and trametinib but discontinued treatment shortly thereafter due to therapy-induced severe pancreatitis requiring hospitalization. Given evidence of metastatic disease involving the brain, lungs, and liver, treatment was switched to encorafenib (450 mg daily) and binimetinib (45 mg daily), treatment was initiated carefully with gradually dose escalation due to the patient’s age and former acute side effects. However, due to treatment-related severe myalgia that necessitated several brief treatment interruptions, the doses were reduced to encorafenib 150 mg once daily and binimetinib 15 mg once daily.

Despite dose modifications, thyroglobulin levels remained stable at approximately 1,100 ng/mL and brain metastasis remained stable on MRI imaging. After 8 months, the patient elected to discontinue active therapy due to persistent myalgia. In January 2025, dabrafenib–trametinib was reintroduced at half the standard dose under close monitoring of amylase and lipase levels, without recurrence of pancreatitis. The patient continues to demonstrate clinical improvement, with thyroglobulin levels decreasing from 7,516 to 1,764 ng/mL as of July 2025.

Case 4

A 76-year-old man presented in November 2020 with a thyroid mass infiltrating the trachea, as well as regional and distant metastases to the lungs, mediastinum, scapula, third rib, and L1 vertebra. The patient underwent a total thyroidectomy with a right lateral neck dissection in February 2021. Tracheal resection was performed for tumor extension, leaving positive surgical margins to avoid the need for total laryngectomy. Pathology revealed tall cell variant PTC, and 8 out of 40 lymph nodes were positive for disease with minimal ECE.

Postoperatively, he received 150 mCi RAI therapy in March 2021. NGS demonstrated mutations in BRAF-V600E and TERT. Dabrafenib–trametinib was initiated in April 2021, but therapy was soon discontinued due to acute liver injury. He was transitioned to encorafenib (450 mg QD) and binimetinib (45 mg QD), achieving a partial response with a thyroglobulin decrease from 20,000 to 8,000 and radiographic and metabolic disease regression on PET-CT. However, treatment was discontinued after 4 months due to acute kidney injury associated with capillary leak syndrome.

To maintain systemic therapy, the patient was initiated on a third BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination, vemurafenib (360 mg BID) and cobimetinib (40 mg QD), approximately 16 months after diagnosis. The disease remained stable for 15 months but showed oligometastatic progression at 21 months, with new skeletal metastases involving the vertebrae and hips. Vemurafenib was escalated to the standard dose; however, follow-up PET-CT imaging 6 months later confirmed further disease progression. He received radiation to progression sites and lenvatinib was introduced at 25 months, but the disease continued to advance, culminating in the patient’s death at 31 months.

Discussion

Here, we presented four cases of thyroid cancer, three PTC and one ATC, which highlight the complex nature of managing advanced thyroid cancers, particularly those with BRAF V600E mutations. All patients received standard-of-care treatments, including surgery, radiation, radioactive iodine, and multikinase inhibitors. For progressive locoregional disease, various BRAF–MEK inhibitors were used as personalized salvage therapy to delay progression and improve quality of life, obtained through individual insurance approvals since they are not included in standard protocols.

The BRAF V600E mutation constitutively activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by promoting ligand-independent phosphorylation of downstream kinases MEK and ERK (9, 13). This dysregulation promotes uncontrolled cell growth and differentiation, contributing to oncogenesis of tumor cells (16, 17). Targeted inhibition of BRAF and MEK interrupts this signaling cascade and has demonstrated clinical benefit across several BRAFV600E-mutated solid tumors (Figure 4) (18).

Figure 4

Schematic representation of the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and sites of targeted inhibition. Binding of growth factors (GF) to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) at the cell membrane activates the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK cascade, ultimately promoting gene transcription, cell growth, and survival. Mutant BRAF (V600E/K) leads to constitutive activation of the pathway. Targeted therapies include BRAF inhibitors: dabrafenib, encorafenib, and vemurafenib, and MEK inhibitors: trametinib, cobimetinib, and binimetinib, which act at their respective kinase levels to block downstream signaling.

The identification of BRAF V600E mutations in these cases underscores the critical role of molecular profiling in guiding treatment decisions (23), particularly in heavily pretreated patients. BRAF V600E is a known driver of thyroid cancer progression and a target for therapy (5, 26, 27). BRAF and MEK inhibitor combinations such as dabrafenib–trametinib, encorafenib–binimetinib, and vemurafenib–cobimetinib exemplify the transition toward personalized medicine in advanced thyroid cancer (14, 23).

While multiple BRAF–MEK combinations are approved for melanoma, with comparable efficacy and slightly differing toxicity profiles, approval in thyroid cancer remains more limited (28). As of 2025, dabrafenib plus trametinib is the only FDA-approved targeted regimen for unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E-mutant ATC, based on the ROAR trial, which demonstrated a 61% response rate (10–12). This combination later received tumor-agnostic approval for BRAF V600E-mutant solid tumors and is recommended by ESMO as standard therapy for eligible ATC patients (10, 12, 18, 29).

Earlier ATA guidelines (2015) recommended kinase inhibitors for progressive, symptomatic, radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer; however, BRAF–MEK combinations were not included due to limited evidence (30–32). The updated 2025 ATA guidelines now support BRAF-directed therapy as a first-line option for patients unsuitable for lenvatinib or those who progress or develop intolerance to prior kinase inhibitors (33).

Toxicity remains a major limitation of BRAF–MEK inhibition. All four patients in this series (100%) developed grade ≥3 adverse events requiring dose modification or discontinuation. The most common toxicities were pyrexia (100%), myalgia (75%), gastrointestinal intolerance (75%), and hepatotoxicity (50%). Given the high incidence and severity of adverse events, rechallenge with BRAF–MEK inhibitors should be cautiously considered, particularly in frail or elderly patients. In case 1, reintroduction of dabrafenib–trametinib following prior encephalopathy and disease progression on encorafenib–binimetinib led to a transient partial response.

Similar toxicity rates are reported in clinical trials. In the phase II ROAR study, 100% of patients experienced adverse events on the standard dabrafenib (150 mg BID) and trametinib (2 mg daily) regimen, with 58% having grade 3–4 toxicity and half requiring dose interruption or reduction (12). Similar toxicity patterns were reported in melanoma, as shown by Long et al., where treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib for stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma resulted in adverse events in 97% of patients, including 41% with grade 3–4 events that led to dose interruption, dose reduction, and treatment discontinuation in 66%, 38%, and 26% of cases, respectively (34). Although large phase III randomized controlled trials evaluating BRAF and MEK inhibitors in thyroid cancer are lacking, case reports, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses of early-phase and non-randomized studies have demonstrated meaningful clinical activity, manageable safety profiles, and improved outcomes in this historically aggressive and treatment-refractory population (12, 14, 15, 17–19, 35, 36). In other settings, trials in advanced RAI-resistant differentiated thyroid cancer have shown the feasibility of using BRAF and MEK inhibitors as part of a redifferentiation treatment strategy, thereby broadening the therapeutic potential of these drug combinations (25, 37).

In a phase II trial by Marcia S. Brose et al. (7), the efficacy of vemurafenib was evaluated in 51 patients with metastatic or unresectable BRAF V600E–positive, RAI-refractory PTC. Vemurafenib achieved a partial response in 38% of patients who had not received prior VEGFR inhibitor therapy, compared with 27% among those previously treated with a VEGFR inhibitor. The corresponding median PFS was 18.2 months versus 8.9 months, respectively. The lower response rates observed in both cohorts may be attributed to the use of BRAF inhibitor monotherapy without concurrent MEK inhibition, and to the latter cohort being more heavily pretreated and having received multiple prior systemic therapies, including chemotherapy, which is rarely used in current practice. Grade 3–4 adverse events occurred in approximately two-thirds of patients, with no treatment-related deaths reported.

Extrapolating from melanoma experience, alternative BRAF and MEK inhibitor combinations beyond dabrafenib–trametinib may help mitigate toxicity while maintaining efficacy in advanced thyroid cancer. In our series, following severe adverse events with two prior regimens, switching to vemurafenib–cobimetinib in case 4 achieved 14 months of stable disease, underscoring the potential benefit of strategic sequencing of alternative targeted combinations.

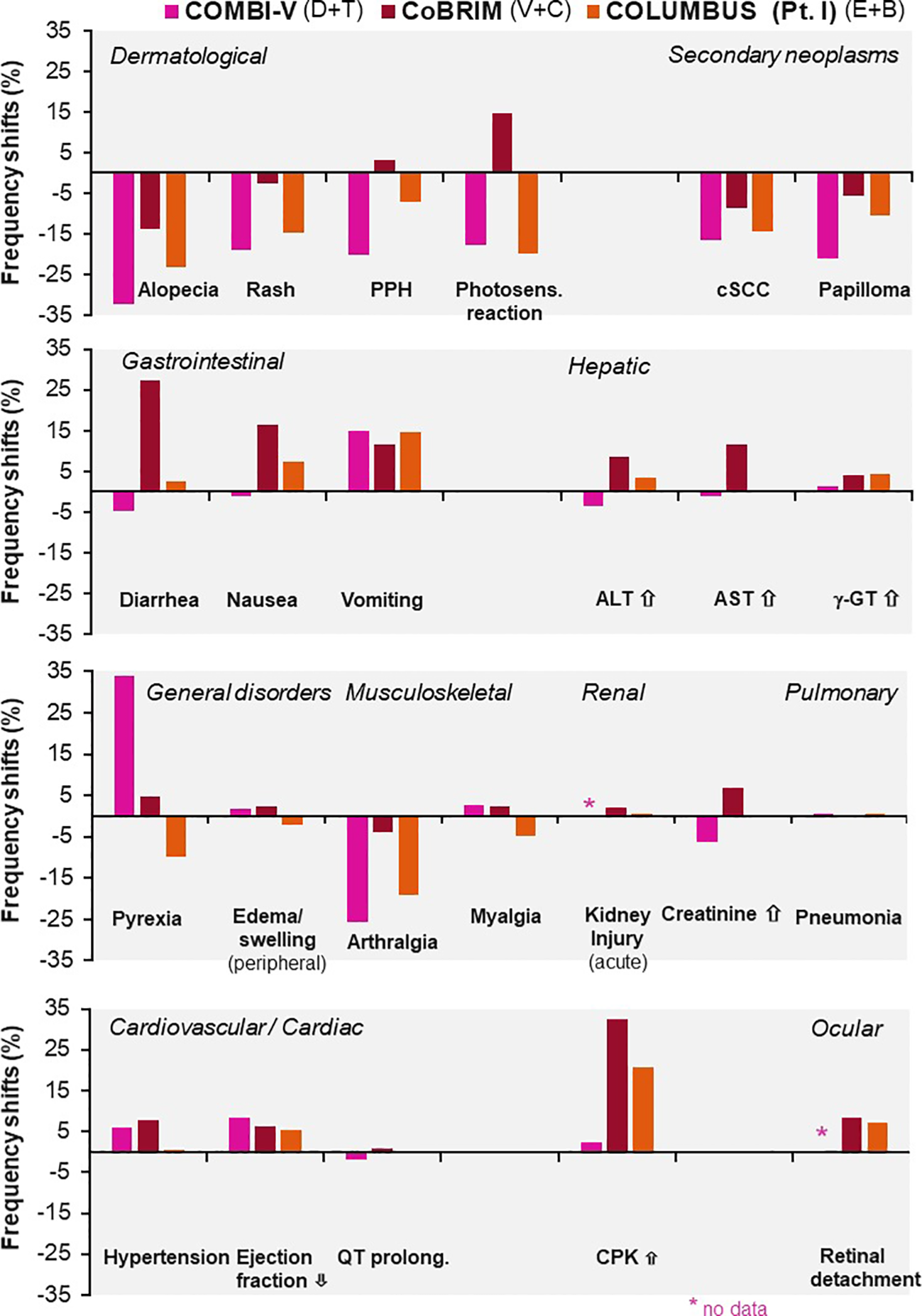

Although these combinations share overlapping toxicities, each agent has a distinctive adverse effect profile: vemurafenib–cobimetinib is associated with photosensitivity and ocular toxicity; dabrafenib–trametinib with pyrexia; while encorafenib–binimetinib with relatively lower pyrexia risk. These differences in adverse effects were thoroughly evaluated in three major clinical trials for advanced melanoma and previously published in ESMO Open, as illustrated in Figure 5 (38). Notably, encephalopathy is a rarely reported adverse effect; however, in case 1, it developed during treatment and, following thorough neurological evaluation, was attributed to dabrafenib and trametinib therapy.

Figure 5

Differences in adverse event frequencies between combination therapies tested for advanced melanoma in three major clinical trials: COMBI-V (dabrafenib plus trametinib), CoBRIM (vemurafenib plus cobimetinib), and COLUMBUS Part 1 (encorafenib plus binimetinib). Shown are frequency shifts (%) in selected adverse events observed in patients treated with. Positive values indicate increased frequency relative to monotherapy; negative values indicate decreased frequency. Reprinted from ESMO Open, Vol. 4, Davies MA et al., “Comparison of adverse event profiles of MEK inhibitors across indications: a review of clinical trials,” e000491, Copyright (2019), with permission from Elsevier.Sciwheel inserting bibliography.

Despite initial responses to targeted therapies, all cases eventually showed disease progression, indicating the development of treatment resistance. Resistance due to escape phenomenon is well-documented in BRAF-mutated cancers, develops faster in thyroid cancer relatively to BRAF positive melanomas, and underscores the need for sequential treatment strategies and ongoing research into resistance mechanisms (24, 32). Reported mechanisms include reactivation of the MAPK pathway through NRAS, KRAS, or CRAF mutations, enhanced receptor tyrosine kinase signaling (HER2, HER3, MET), and secondary alterations in MEK or BRAF splice variants (39, 40). Tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution further limit response durability (41). These findings emphasize the need for re-biopsy and molecular re-profiling at progression to inform second-line strategies or trial enrollment.

Two patients (50%) in our series harbored concomitant TERT promoter mutations. Although BRAF and TERT co-mutations are well recognized for their association with radioiodine resistance and more aggressive disease (42), the limited sample size in our cohort precludes definitive conclusions regarding their role in treatment resistance. Further studies are warranted to elucidate their potential contribution to resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors.

In the updated phase II ROAR trial, the objective response rate (ORR) was 56% with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.7 months (12). The Japanese BELIEVE trial demonstrated a lower ORR of 33.3% and median PFS of 5.7 months in a cohort comprising 10 PTC patients and 5 with undifferentiated thyroid cancer, without distinction between poorly differentiated carcinoma (PDC) and ATC (20). In our series, progression-free survival for dabrafenib trametinib averaged 5.75 months (based on two evaluated patients), 5.75 for encorafenib–binimetinib (based on four evaluated patients), and 14 for vemurafenib–cobimetinib (based on one evaluated patient).

Superior outcomes were reported by the Korean group of Jeon et al. (2024), with a total ORR of 73.1% and differential PFS outcomes of 23.3 months for PTC and 4.5 months for undifferentiated histologies (21). Notably, this improved efficacy may be attributed to the study design, wherein out of the 27 patients two-thirds of patients received dabrafenib plus trametinib as first-line therapy, without prior exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy or multiple kinase inhibitors. An additional small phase 2 trial including 22 patients, of whom 17 had differentiated thyroid cancer and 9 ATC, found that encorafenib and binimetinib achieved an ORR of 47.1% in the differentiated subgroup and 54.5% overall (95% CI 32.2–75.6), with partial responses in 12 patients and stable disease in 10 (22). Grade 3 adverse events occurred in 27.3%, with no grade 4 or 5 events, highlighting a modest safety profile (22).

Case 1 illustrates the therapeutic potential of BRAF-directed therapy in ATC, historically associated with dismal prognosis (4, 43). The use of BRAF-targeted therapy in this case aligns with recent advancements in ATC treatment, offering a potential avenue for improved outcomes in this historically difficult-to-treat malignancy (26, 27, 29, 44). Treatment with BRAF+MEK inhibitors as well as the initiation of chemoradiation therapy not only saved the patient from undergoing total laryngectomy but also made the tumor operable with the opportunity of achieving clear surgical margins. Unfortunately, the tumor recurred and the patient refused further treatment even though the last pathology confirmed a combined positivity score of 80.

In case 3, BRAF–MEK inhibition demonstrated intracranial activity in brain metastases, consistent with literature reporting adequate central nervous system penetration over multiple kinase inhibitores (45). Although lenvatinib is considered as the first-line treatment for RAI-refractory PTC (33), the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors is often preferred in the immediate postoperative period following major surgery because of the risk of impaired wound healing (46). This consideration was the primary rationale for selecting BRAF and MEK inhibitor regimen in case 4, after the patient had undergone tracheal resection.

Conclusion

These cases underscore the necessity of a multimodal, individualized approach to advanced thyroid cancer. The integration of surgery, radiation, radioiodine, and targeted systemic therapy optimizes disease control, while molecular profiling has become indispensable in guiding precision treatment. BRAF and MEK inhibition represents a major therapeutic advancement; however, toxicity management, treatment sequencing, and the emergence of resistance remain significant challenges. This case series highlights both the progress achieved and the unmet needs in managing advanced thyroid malignancies. Continued clinical investigation and translational research are essential to refine patient selection, enhance tolerability, and improve long-term outcomes in this complex disease spectrum.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center IRB 0197-25. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Author contributions

TY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. OC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ER: Validation, Writing – review & editing. EI: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. OG: Writing – review & editing. YL: Writing – review & editing. RM: Writing – review & editing. AW: Writing – review & editing. NM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. IF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Avi Khafif for his valuable insights; he had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, manuscript preparation, or the decision to publish.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Elisei R Ugolini C Viola D Lupi C Biagini A Giannini R et al . BRAF(V600E) mutation and outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a 15-year median follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2008) 93:3943–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0607

2

Xing M . BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. (2005) 12:245–62. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.0978

3

Sandulache VC Williams MD Lai SY Lu C William WN Busaidy NL et al . Real-time genomic characterization utilizing circulating cell-free DNA in patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. (2017) 27:81–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0076

4

Riesco-Eizaguirre G Rodríguez I De la Vieja A Costamagna E Carrasco N Nistal M et al . The BRAFV600E oncogene induces transforming growth factor beta secretion leading to sodium iodide symporter repression and increased Malignancy in thyroid cancer. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:8317–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1248

5

Xing M Westra WH Tufano RP Cohen Y Rosenbaum E Rhoden KJ et al . BRAF mutation predicts a poorer clinical prognosis for papillary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2005) 90:6373–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0987

6

Graboyes EM Kompelli AR Neskey DM Brennan E Nguyen S Sterba KR et al . Association of treatment delays with survival for patients with head and neck cancer: A systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2019) 145:166–77. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2716

7

Brose MS Cabanillas ME Cohen EWC Wirth LJ Riehl T Yue H et al . Vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E)-positive metastatic or unresectable papillary thyroid cancer refractory to radioactive iodine: a non-randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:1272–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30166-8

8

Subbiah V Kreitman RJ Wainberg ZAW Cho JY Schellens JHM Soria JC et al . Dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic BRAF V600-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:7–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.6785

9

Gouda MA Nelson BE Buschhorn L Wahida A Subbiah V . Tumor-agnostic precision medicine from the AACR GENIE database: clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. (2023) 29:2753–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-0090

10

Boussemart LB Routier E Mateus C Oplova K Sebille G Kamsu-Kom N et al . Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:1691–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt015

11

FDA . FDA approves new uses for two drugs administered together for the treatment of BRAF-positive anaplastic thyroid cancer. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-uses-two-drugs-administered-together-treatment-braf-positive-anaplastic-thyroid (Accessed January 24, 2025).

12

Subbiah V Kreitman RJ Wainberg ZAW Cho JY Schellens JHM Soria JC et al . Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF V600E-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer: updated analysis from the phase II ROAR basket study. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:406–15. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.12.014

13

Gouda MA Subbiah V . Precision oncology for BRAF-mutant cancers with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: from melanoma to tissue-agnostic therapy. ESMO Open. (2023) 8:100788. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100788

14

Dadu R Shah K Busaidy NL Waguespack SG Habra MA Ying AK et al . Efficacy and tolerability of vemurafenib in patients with BRAF(V600E) -positive papillary thyroid cancer: M.D. Anderson Cancer Center off label experience. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 100:E77–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2246

15

Subbiah V Lassen U Élez E Italiano A Curigliano G Javle M et al . Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600E-mutated biliary tract cancer (ROAR): a phase 2, open-label, single-arm, multicentre basket trial. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:1234–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30321-1

16

Pearson G Robinson F Beers Gibson T Xu BE Karandikar M Berman K et al . Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. (2001) 22:153–83. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428

17

Subbiah V Baik C Kirkwood JM . Clinical development of BRAF plus MEK inhibitor combinations. Trends Cancer. (2020) 6:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.05.009

18

Gouda MA Subbiah V . Expanding the benefit: dabrafenib/trametinib as tissue-agnostic therapy for BRAF V600E-positive adult and pediatric solid tumors. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. (2023) 43:e404770. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_404770

19

Violetis O Konstantakou P Spyroglou A Xydakis A Kekis PB Tseleni S et al . The long journey towards personalized targeted therapy in poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC): a case report and systematic review. J Pers Med. (2024) 14:654. doi: 10.3390/jpm14060654

20

Shimoi T Sunami K Tahara M Nishiwaki S Tanaka S Baba E et al . Dabrafenib and trametinib administration in patients with BRAF V600E/R or non-V600 BRAF mutated advanced solid tumours (BELIEVE, NCCH1901): a multicentre, open-label, and single-arm phase II trial. EClinicalMedicine. (2024) 69:102447. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102447

21

Jeon Y Park S Lee SH Kim TH Kim SW Ahn MJ et al . Combination of dabrafenib and trametinib in patients with metastatic BRAFV600E-mutated thyroid cancer. Cancer Res Treat. (2024) 56:1270–6. doi: 10.4143/crt.2023.1278

22

Tahara M Kiyota N Imai H Takahashi S Nishiyama A Tamura S et al . A phase 2 study of encorafenib in combination with binimetinib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutated thyroid cancer in Japan. Thyroid. (2024) 34:467–76. doi: 10.1089/thy.2023.0547

23

Chen H Luthra R Routbort MJ Patel KP Cabanillas ME Broaddus RR et al . Molecular profile of advanced thyroid carcinomas by next-generation sequencing: characterizing tumors beyond diagnosis for targeted therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. (2018) 17:1575–84. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0871

24

Eisenhauer EA Therasse P Bogaerts J Schwartz LH Sargent D Ford R et al . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1. 1) Eur J Cancer. (2009) 45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

25

Leboulleux S Dupuy C Lacroix L Attard M Grimaldi S Corre R et al . Redifferentiation of a BRAFK601E-mutated poorly differentiated thyroid cancer patient with dabrafenib and trametinib treatment. Thyroid. (2019) 29:735–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0457

26

Ge J Wang J Wang H Jiang X Liao Q Gong Q et al . The BRAF V600E mutation is a predictor of the effect of radioiodine therapy in papillary thyroid cancer. J Cancer. (2020) 11:932–9. doi: 10.7150/jca.33105

27

Xing M Alzahrani AS Carson KA Viola D Elisei R Bendlova B et al . Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. (2013) 309:1493–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3190

28

Chapman PB Hauschild A Robert C Haanen JB Ascierto P Larkin J et al . Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. (2011) 364:2507–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782

29

Filetti S Durante C Hartl D Leboulleux S Locati LD Newbold K et al . Thyroid cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:1856–83. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz400

30

Haugen BR Alexander EK Bible KC Doherty GM Mandel SJ Nikiforov YE et al . 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the american thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. (2016) 26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020

31

Salerno P De Falco V Tamburrino A Nappi TCN Vecchio G Schweppe RE et al . Cytostatic activity of adenosine triphosphate-competitive kinase inhibitors in BRAF mutant thyroid carcinoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2010) 95:450–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0373

32

Schubert L Mariko ML Clerc J Huillard O Groussin L . MAPK pathway inhibitors in thyroid cancer: preclinical and clinical data. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030710

33

Ringel MD Sosa JA Baloch Z Bischoff L Bloom G Brent GA et al . 2025 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. (2025) 35:841–85. doi: 10.1177/10507256251363120

34

Long GV Hauschild A Santinami M Atkinson V Mandalà M Chiarion-Sileni V et al . Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:1813–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708539

35

Peng X Lei J Li Z Zhang K . Case report: visibly curative effect of dabrafenib and trametinib on advanced thyroid carcinoma in 2 patients. Front Oncol. (2023) 12:1099268. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1099268

36

Priantti JN Rodrigues NMV de Moraes FCA da Costa AG Jezini DL Heckmann MIO . Efficacy and safety of BRAF/MEK inhibitors in BRAFV600E-mutated anaplastic thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. (2024) 86:284–92. doi: 10.1007/s12020-024-03845-w

37

Iravani A Solomon B Pattison DA Jackson P Kumar AR Kong G et al . Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibition for redifferentiation of radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer: an evolving protocol. Thyroid. (2019) 29:1634–45. doi: 10.1089/thy.2019.0143

38

Heinzerling L Eigentler TK Fluck M Hassel JC Heller-Schenck D Leipe J et al . Tolerability of BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations: adverse event evaluation and management. ESMO Open. (2019) 4:e000491. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000491

39

Lee M Morris LG . Genetic alterations in thyroid cancer mediating both resistance to BRAF inhibition and anaplastic transformation. Oncotarget. (2024) 15:36–48. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.28544

40

Van Allen EM Wagle N Sucker AS Treacy DJ Johannessen CM Goetz EM et al . The genetic landscape of clinical resistance to RAF inhibition in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Discov. (2014) 210(Supplement 1):15–8. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0617

41

Zeng PYF Meens J Pan H Cecchini M Karimi A Palma D et al . Understanding and overcoming innate and acquired MAPK-inhibition resistance in anaplastic thyroid cancer. medRxiv. (2024). doi: 10.1101/2024.12.04.24318267

42

Le TTN Nghiem XH Dao PG Dang TD Nguyen TP Ngo TMH et al . Prognostic significance of BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations in radioiodine resistance and recurrence of differentiated thyroid cancer. Med (Baltimore). (2025) 104:e44540. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000044540

43

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) | Protocol Development | CTEP . Available online at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htmctc_60 (Accessed May 2, 2025).

44

Iñiguez-Ariza NM Ryder MM Hilger CR Bible KC . Salvage lenvatinib therapy in metastatic anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid. (2017) 27:923–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0627

45

Liao G Fu Y Arooj S Khan M Li X Yan M et al . Impact of previous local treatment for brain metastases on response to molecular targeted therapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma brain metastasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:704890. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.704890

46

Cheng C Nayernama A Jones SC Casey D Waldron PE . Wound healing complications with lenvatinib identified in a pharmacovigilance database. J Oncol Pharm Pract. (2019) 25:1817–22. doi: 10.1177/1078155218817109

Summary

Keywords

BRAF V600E mutation, papillary thyroid carcinoma, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, targeted therapy, real-world evidence

Citation

Yamin T, Cohen O, Robenshtok E, Izkhakov E, Miodovnik M, Gutfeld O, Leshem Y, Meirovitz R, Warshavsky A, Muhanna N and Finkel I (2026) BRAF and MEK inhibition beyond dabrafenib–trametinib in advanced thyroid cancer: a real-world case series. Front. Endocrinol. 17:1694805. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2026.1694805

Received

28 August 2025

Revised

09 November 2025

Accepted

19 January 2026

Published

05 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Dario de Biase, University of Bologna, Italy

Reviewed by

Krystallenia I. Alexandraki, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Marilda Mormando, Regina Elena National Cancer Institute (IRCCS), Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yamin, Cohen, Robenshtok, Izkhakov, Miodovnik, Gutfeld, Leshem, Meirovitz, Warshavsky, Muhanna and Finkel.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tzahi Yamin, yaminzack@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.