Abstract

Introduction:

The first vaccines approved against SARS-CoV-2, mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2, utilized mRNA platforms. However, little is known about the proteomic markers and pathways associated with host immune responses to mRNA vaccination. In this proof-of-concept study, sera from male and female vaccine recipients were evaluated for proteomic and immunologic responses 1-month and 6-months following homologous third vaccination.

Methods:

An aptamer-based (7,289 marker) proteomic assay coupled with traditional serology was leveraged to generate a comprehensive evaluation of systemic responsiveness in 64 and 68 healthy recipients of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccines, respectively.

Results:

Sera from female recipients of mRNA-1273 showed upregulated indicators of inflammatory and immunological responses at 1-month post-third vaccination, and sera from female recipients of BNT162b2 demonstrated upregulated negative regulators of RNA sensors at 1-month. Sera from male recipients of mRNA-1273 showed no significant upregulation of pathways at 1-month post-third vaccination, though there were multiple significantly upregulated proteomic markers. Sera from male recipients of BNT162b2 demonstrated upregulated markers of immune response to doublestranded RNA and cell-cycle G(2)/M transition at 1-month. Random Forest analysis of proteomic data from pre-third-dose sera identified 85 markers used to develop a model predictive of robust or weaker IgG responses and antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein at 6-months following boost; no specific markers were individually predictive of 6-month IgG response. Thirty markers that contributed most to the model were associated with complement cascade and activation; IL-17, TNFR pro-apoptotic, and PI3K signaling; and cell cycle progression.

Discussion:

These results demonstrate the utility of proteomics to evaluate correlates or predictors of serological responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

1 Introduction

The global response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic of 2020 ushered in a new chapter in vaccinology with the development and wide-spread use of mRNA-based vaccines (1). However, evidence is mounting that a more individualized approach may be needed as the COVID-19 landscape continues to evolve. The 2 original mRNA vaccines to SARS-CoV-2, BNT162b2 (Pfizer) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) both target immune responses to full-length viral spike protein and have been highly successful in preventing severe COVID-19 disease, hospitalization, and death on the population level (2–5). However, the 2 vaccine types include different concentrations of mRNA per dose and have demonstrated differences in immunogenicity in different patient groups and between sexes assigned at birth (2–4, 6–10). In addition, multiple studies have shown that the circulating vaccine induced antibody levels decline rapidly in most recipients within a couple of months of primary series vaccination (7, 8, 11–13), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has since recommended additional vaccination doses and vaccines to develop sustainable and effective humoral responses (14). To add complexity, new viral variants routinely emerge and often escape neutralization, resulting in high numbers of breakthrough infections (15, 16). These observations support the CDC recommendation of booster immunizations for all recipients (17), however there are no known correlates of protection and it is not clear which patients will have robust versus weaker responses that may be strengthened through the administration of additional doses.

Established correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection or disease would be extremely valuable to inform recommendations for booster vaccinations. The mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are believed to impart protection through neutralizing antibody responses (as in other infections such as with Human Papillomavirus), as well as cell-mediated immune responses, and both responses result in distinct protein expression patterns (18–22). Proteomic changes in serum may consequently prove to be indicative, or even predictive, of vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy, and could inform new vaccine recommendations and developments.

The recent evolution of proteomic affinity-capture platforms into large comprehensive screening tools (23) provide a unique opportunity to evaluate broad spectrum protein responses in easily accessible, small volume serum samples (24). However, it remains to be demonstrated whether protein markers can be realistically used to predict serological immune responses. In this proof-of-concept study, a 7,289-proteome assay was used to evaluate human protein markers pre- and post-homologous third dose of mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 in healthy vaccine recipients and then the results were compared with humoral response. Specifically, serum antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 spike, proteins, and impacted cellular pathways were analyzed in samples collected 1-month and 6-months after a third dose of vaccine and compared to pre-third dose samples. Influence of vaccine type and sex assigned at birth were also evaluated for differing antibody and proteomic profiles. In addition, pre-third dose sera were evaluated for proteomic markers that could be predictors of either higher or lower vaccine-induced serum IgG antibody content and used to develop a model predictive of 6-month antibody levels.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples

Serum samples were collected from healthy vaccine recipients by Feinstein-Northwell Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY (Institutional Review Board #20-1007) and by the National Institutes of Health’s Occupational Safety and Health Office located at Ft. Detrick, MD under the Research Donor Protocol (RDP). RDP participants were healthy NCI-Frederick employees and other NIH staff that donated blood samples for in-vitro research at the NCI-Frederick laboratories. The protocol is listed under NIH protocol number OH99CN046 and NCT number NCT00339911. Blood donors ranged in age from 25-76 years and included 67 females and 65 males; demographics are presented in Table 1. Study participants were sampled 61-377 days after administration of the second dose of the same primary series vaccine (either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273) serving as a pre-boost timepoint. Participants were then boosted with a homologous third dose, and then sampled at 1-month (15 to 45 days post-third vaccination) and at 6-months (165-195 days post-third vaccination). Blood samples were processed at the collection sites, sera were frozen and stored at -80°C and then shipped on dry ice to the NCI-Frederick Repository until requested for testing at the Vaccine, Immunity, and Cancer Directorate (VICD).

Table 1

| Study Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Participants | BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 |

| Number (n) | 68 | 64 |

| Geometric mean Age (Years) | 46.6 | 42.5 |

| Age Min-Max (Years) | 25-71 | 25-76 |

| Female (percent) | 34 (50) | 33 (52) |

| Male (percent) | 34 (50) | 31 (48) |

Study demographics.

2.2 Serology

2.2.1 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA assays used to quantify human serum IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein were performed at room temperature (RT) as follows: Maxisorp 96-well plates (Thermo-Scientific Cat# 439454) were coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (SARS-CoV-2 S-2P (14-1213)-T4f-His6) sourced from the Protein Expression Laboratory (PEL) at Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research (FNLCR), (0.15 µg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). After coating for a minimum of 24 hours at 4°C, assay plates were washed with a PBS-Tween buffer and blocked with PBS-Tween 0.20% and 4.00% skim milk (BD, Cat# 232100) for 90 minutes. Following a plate wash, heat-inactivated samples were tested with appropriate in-well dilution series. Plates were incubated for 60 minutes with the samples, washed, and then incubated for an additional 60 minutes with an empirically determined dilution of goat anti-human IgG HRP-conjugate in PBS-Tween (Seracare, Cat# 5220-0390). The plates were washed and developed with tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) 2-component substrate (Seracare, Cat# 5120-0049, 5120-0038) for 25 minutes. Finally, the reaction in the plate wells was stopped with 0.36N sulfuric acid and read at 450nm and 620nm on a SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data analyses were performed using SoftMax Pro GxP 7.0.3. Reportable values for IgG quantitative ELISA are binding antibody units per milliliter (BAU/mL), based on a standard calibrated to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Standard (25).

2.2.2 Avidity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (chaotrope ELISA)

Avidity ELISA assays (chaotrope assays) are based on standard ELISA tests for anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein IgG but include an additional step where the analyte (antibody) is exposed to a chaotropic agent that effectively breaks and elutes off weakly bound antibody species; a “bind and break” ELISA. Urea was used as the chaotropic agent due to its experimental range and minimal impact on assay plate coat integrity. Avidity ELISAs were performed on sample dilutions with optical densities (OD) between 0.50 to 1.30 OD units at 450nM; 1.00 was the target OD. Extensive assay development with multiple SARS-CoV-2 serum samples demonstrated highly reproducible (CV<10%) measurements in this range (13). Each assay plate tested 5 serum samples in duplicate. After each sample was incubated on the assay plate for 1 hour at 22°C (room temperature [RT]), the plates were washed and incubated with dilutions of urea ranging from 0 to 10M for 15 minutes at 22°C. After 4 washes with PBS-Tween, plates were developed as described above for the quantitative IgG assay. Serum avidity assessments are reported as Avidity Indices (AI20); the molar concentration (M) of chaotrope required to reduce the optical density of the sample to 80% that of untreated wells. Additionally, each assay plate contained 2 system suitability controls that were developed from well characterized serum samples: 1 control with a known low avidity index, the other a known high avidity index.

2.3 Proteomics

SomaLogic’s SomaScan v4.1 7K Assay platform was used to evaluate serum protein content longitudinally for significant changes in abundance at 1-month and 6-months following homologous third vaccination. Protein quantitated in sera collected pre-third dose set baseline values for each study participant. The SomaScan assay was performed on a Tecan Fluent 780 high throughput system according to manufacturer’s instructions at the NIH Center for Human Immunology. A complete list of the 7,289 targets analyzed is available at https://menu.somalogic.com. The data are reported in relative fluorescence units (RFU), a surrogate for protein concentration. The SomaScan Assay data were normalized using SomaLogic’s standardization procedure (26). In short, data were first normalized to correct for well-to-well variation in microarray hybridization steps. This was then followed by intraplate median signal normalization to correct for sample-to-sample differences that may be introduced due to technical assay effects. Plate scaling was applied to normalize global signal differences between plates, and calibration was applied to adjust for SOMAmer reagent-specific differences between tests. Finally, median signal normalization was performed via Adaptive Normalization by Maximum Likelihood (ANML) to harmonize data across multiple assay plates.

2.4 Data analyses

Serum IgG antibody to SARS-CoV-2 spike concentrations are reported as geometric mean binding antibody units per milliliter (BAU/mL) based on established serological WHO standards (27).

Proteomic data were stratified based on vaccine received and sex assigned at birth for these analyses. In total, data analyses were performed on 12 data subsets as follows: 2 vaccines assessed at 3 timepoints and against 2 sex assigned at birth stratifications.

2.5 Antibody and avidity level analyses

Serum antibody levels and avidity are expressed as geometric mean concentrations (GMC) and geometric mean avidity levels (GMA), respectively, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. A Mann-Whitney U test (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test) was used when comparing antibody content or avidity values between vaccine type, or between sex assigned at birth. A Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used when serological tests were evaluated between timepoints. These tests were chosen because they do not have the requirement of a normal distribution of values, as in an unpaired or paired t-test, and work for smaller sample sizes; p<0.05 was considered significant.

2.6 Proteomic data analysis

Serum proteins were quantitated using the SomaScan v4.1 7K Assay platform (28, 29). The geometric mean value for each detectable protein within each cohort was quantitated in relative fluorescent units (RFU), and the magnitude of protein abundance change was expressed with the following formulas: log2(1-month value/pre-third-dose value) and log2(6-month value/pre-third-dose value). A 2-tailed t-test was performed to determine if the calculated geometric mean values were significantly different between the 2 timepoints. p-values in this assessment provided significance thresholds. Proteins having a p-value of <0.05 and a log protein abundance difference of >0.20 (significant increase) or <-0.20 (significant decrease) were identified as proteins that demonstrated significant differences in content.

2.7 Pathway analyses

Biological processes impacted by vaccination were evaluated through KEGG and REACTOME pathway functional enrichment analyses. Enrichment ratio and false discovery rate (FDR) were calculated for significant proteins using the WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt) 2 (30). EntrezGene was used to map proteins to gene identifiers. Background gene sets for enrichment analyses were created by selecting all unique EntrezGene names from all protein analytes detected in the SomaScan Assay.

2.8 Predictive analyses

As serological antibody responses to the 2 vaccines were largely analogous irrespective of vaccine or sex assigned at birth (Tables 2, 3), and because of the limited sizes of the vaccine recipient cohorts, the entire database was evaluated without segregation by sex assigned at birth or vaccine to identify pre-third-dose markers predicting 6-month antibody response levels. Attempts to develop predictive models specific for sex assigned at birth or vaccine were unsuccessful lacking sufficient predictive accuracy; larger sample sizes would be necessary to develop segregated models.

Table 2

| Response to Homologous third Vaccination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric mean IgG Content, 95% CI:(BAU/mL) | |||

| Pre-third vaccination | 1-month | 6-months | |

| mRNA-1273 | 619 (427-896) | 8655 (7074-10591) | 3074 (2382-3966) |

| BNT162b2 | 268 (212-340) | 7635 (6542-8910) | 2823 (2222-3587) |

| p-value | 0.0006 | 0.3008 | 0.5872 |

| Avidity Development (M) | |||

| Pre-third vaccination | 1-month | 6-months | |

| mRNA-1273 | 4.1 (3.8-4.3) | 5.5 (5.4-5.6) | 5.3 (5.1-5.5) |

| BNT162b2 | 3.5 (3.3-3.8) | 5.4 (5.2-5.5) | 5.3 (5.1-5.5) |

| p-value | 0.0247 | 0.3640 | 0.8964 |

Serology responses to vaccination, influence of vaccine type.

Table 3

| Influence of sex assigned at birth on Response to Homologous third Vaccination Geometric mean IgG Content, 95% CI:(BAU/mL) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-third vaccination | 1-month | 6-months | ||||

| Male | 424 (298-602) | 8124 (6757-9768) | 3175 (2423-4161) | |||

| Female | 383 (285-513) | 8088 (6804-9614) | 2747 (2193-3440) | |||

| p-value | 0.6273 | 0.7382 | 0.6434 | |||

| Male Vaccine Recipients Geometric mean IgG Content, 95% CI:(BAU/mL) |

||||||

| Pre-third vaccination | 1-month | 6-months | ||||

| mRNA-1273 | 688 (391-1214) | 9400 (6936-12739) | 3879 (2570-5855) | |||

| BNT162b2 | 272 (183-406) | 7173 (5707-9016) | 2682 (1856-3875) | |||

| p-value | 0.0092 | 0.1940 | 0.2403 | |||

| Female Vaccine Recipients Geometric mean IgG Content, 95% CI:(BAU/mL) |

||||||

| Pre-third vaccination | 1-month | 6-months | ||||

| mRNA-1273 | 560 (336-932) | 8050 (6070-10675) | 2540 (1839-3510) | |||

| BNT162b2 | 265 (202-347) | 8126 (6535-10103) | 2963 (2133-4115) | |||

| p-value | 0.0436 | 0.9851 | 0.6582 | |||

Circulating IgG antibody content to SARS-CoV-2 Spike, Influence of sex assigned at birth.

A pilot machine learning model was developed (Figure 1) using Random Forest (RF) to predict antibody response levels at 6-months. Thirty-nine subjects were identified as higher responders (IgG > 5000 BAU/mL) and 44 subjects were identified as lower responders (IgG < 2000 BAU/mL) based on IgG levels at 6-months. A 2-tailed t-test was performed to determine if the calculated geometric mean values of the protein levels at pre-third dose for the 2 groups were significantly different from zero. One hundred and seven statistically significant markers were identified based on comparative changes between the extreme (higher or lower) responders (p<0.05). The markers were reduced to an 85-feature set by removing redundant predictors, or co-linear markers. The RF model was trained with data from 28 higher responders and 31 lower responders, and the model was tested on the remaining 11 higher responders and 13 lower responders and achieved a predictive accuracy of 79.17% on test data with an area under the curve (AUC) of 86.71%.

Figure 1

Schematic of the pilot machine learning model. Thirty-nine subjects were identified as higher responders (IgG > 5000 BAU/mL) and 44 subjects were identified as lower responders (IgG < 2000 BAU/mL) based on IgG levels at 6-months. One hundred and seven statistically significant markers were identified based on comparative changes between the extreme (higher or lower) responders (p<0.05). The markers were reduced to an 85-feature set by removing redundant predictors, or co-linear markers. The RF model was trained with data from 28 higher responders and 31 lower responders, and the model was tested on the remaining 11 higher responders and 13 lower responders and achieved a predictive accuracy of 79.17% on test data with an area under the curve (AUC) of 86.71%.

2.9 Confounding factors to predictive model development

Assessments of vaccination responses were confounded with the observation that 18 mRNA-1273 and 19 BNT162b2 recipients had antibody reactive to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, despite no self-reports of infection indicating coronavirus infections or potential exposure. Moreover, 14 mRNA-1273 and 7 BNT162b2 vaccine recipients had positive nucleocapsid tests at 1-month and 6-month timepoints, possibly indicating subclinical infections. To evaluate the priming influence of the infections, the dataset was re-examined excluding vaccine-recipient samples that tested positive for coronavirus nucleocapsid. Evaluation of nucleocapsid-antibody negative sera did not significantly affect pre-third-dose predictive marker sets or pathways associated with higher or lower 6-month serology. Analyses of the nucleocapsid naïve dataset did produce 1 additional cellular process - mitophagy (selective degradation of defective mitochondria) -which contributed to model development (Data not shown).

3 Results

3.1 There were no significant serological differences based on vaccine-received or sex assigned at birth

The development of a predictive model of 6-month IgG antibody response levels from vaccination through proteomic assessments of sera required desegregated analyses due to study size. Consequently, we evaluated in-depth both the quality and robustness of the IgG responses by vaccine received and sex assigned at birth to assure validity of our desegregated assessment. Serological responses were comparable across both vaccine types and sexes assigned at birth at both 1-month and 6-months post-third vaccinations (Figures 2A, B; Tables 2, 3); the only significant differences were detected in pre-third-dose sera (mRNA-1273 primary vaccine recipients demonstrated statistically higher antibody and avidity levels to spike compared to recipients of BNT162b2, irrespective of sex assigned at birth [antibody levels: p=0.0006 vaccines, p=0.0092 males, p=0.0436 females; avidity: p=0.0247]) (Figures 2A, C, D; Table 2). Additionally, the mean time between primary series vaccination and third dose of vaccine was different in the 2 vaccine groups: 294 days (164-377) for mRNA-1273 recipients and 265 days (61-377) for BNT162b2 recipients (p<0.0001, Mann Whitney).

Figure 2

Serological Assessments of Responses to Homologous Third Vaccination. Assessments of IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike content of serum. (A) Comparison of serum antibody levels pre-boost and 1 and 6 months after vaccination. (B) Response to third vaccination by sex assigned at birth; male recipients (Blue), female recipients (Red). (C) Vaccine response to homologous third vaccination in sera from male recipients. (D) Vaccine response to homologous third vaccination in sera from female recipients. mRNA-1273 results are shown in purple, BNT162b2 in green. Group geometric mean vales are depicted by the bar graph horizontal line and listed above each bar with the 95 percent confidence interval of the geometric mean. Statistically significant comparisons are depicted with p values.

In detail, the geometric mean anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG antibody levels in mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 recipients at 1-month were 8655 (95% CI: 7074-10591) BAU/mL and 7635 (95% CI: 6542-8910) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.3008 (Figure 2A; Table 2). The geometric mean antibody avidity levels at 1-month for mRNA-1273 and recipients BNT162b2 were 5.5 (95% CI: 5.4-5.6) M and 5.4 (95% CI: 5.2-5.5) M, respectively; p=0.3640 (Table 2). The 6-month geometric mean anti-SARS-CoV-2 levels for mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 recipient sera were 3074 (95% CI: 2382-3966) BAU/mL and 2823 (95% CI: 2222-3587) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.5872 (Figure 2A; Table 2). The geometric mean antibody avidity levels at 6-months for mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 recipients were 5.3 (95% CI: 5.1-5.5) M and 5.3 (95% CI: 5.1-5.5) M, respectively; p=0.8964 (Table 2).

When serology responses were analyzed according to sex assigned at birth, male and female recipients had geometric mean serum antibody levels at 1-month of 8124 (95% CI: 6757-9768) BAU/mL and 8088 (95% CI: 6804-9614) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.7382 (Figure 2B; Table 3). At 6-months, male and female recipients had geometric mean serum antibody levels of 3175 (95% CI: 2423-4161) BAU/mL and 2747 (95% CI: 2193-3440) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.6434 (Figure 2B; Table 3). There were also no statistically significant serum avidity differences based on sex assigned at birth (data not shown).

Further analyzing according to both sex assigned at birth and vaccine, male recipients of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 at 1-month demonstrated geometric mean serum antibody levels of 9400 (95% CI: 6936-12739) BAU/mL and 7173 (95% CI: 5707-9016) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.1940 (Figure 2C; Table 3). Female recipients of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 at 1-month had geometric mean serum antibody levels of 8050 (95% CI: 6070-10675) BAU/mL and 8126 (95% CI: 6535-10103) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.9851 (Figure 2D; Table 3). At 6-months, male recipients of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 had geometric mean serum antibody levels of 3879 (95% CI: 2570-5855) BAU/mL and 2682 (95% CI: 1856-3875) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.2403 (Figure 2C; Table 3). Finally, at 6-months female recipients of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 had geometric mean serum antibody levels of 2540 (95% CI: 1839-3510) BAU/mL and 2963 (95% CI: 2133-4115) BAU/mL, respectively; p=0.6582 (Figure 2D; Table 3).

3.2 Proteomic Assessments of cohorts by vaccine and sex assigned at birth

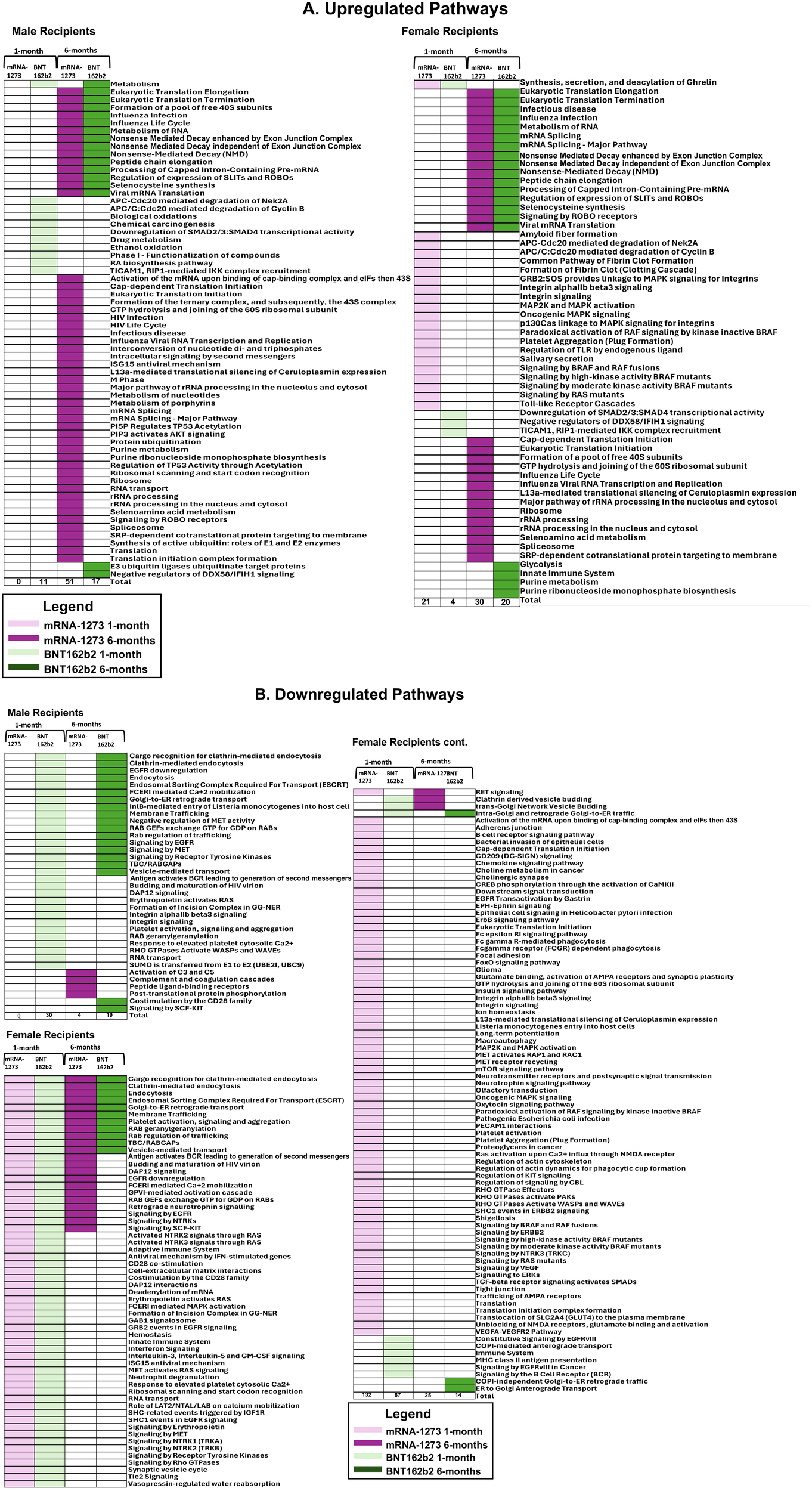

Proteomic profiles in serum from each vaccine recipient were assessed with the SomaScan v4.1 7K Assay platform before the third vaccination (after completion of 2-dose primary vaccine series), and then at 1-month and 6-months post-third vaccination; summary of changes in protein marker expression profiles of the respective cohorts are presented in Supplementary Table S1A (downregulated markers) and Supplementary Table S1B (upregulated markers) and Figure 3. Significant proteins were selected based on p-value and average log abundance differences (Figure 4; Supplementary Tables S1A, B).

Figure 3

Assessment of Proteomic Marker Profiles by Vaccination Cohort and sex assigned at birth. Assessment of proteomic marker changes from baseline measurement. (A, B) are diagrams of assessment of markers upregulated at 1-month and 6-months in sera from male and female recipients (respectively); (C, D) are diagrams of assessment of markers downregulated at 1- and 6-months in sera from male and female recipients (respectively). mRNA-1273 vaccinated (1-month) light purple and (6-month) dark purple. BNT162b2 vaccinated (1-month) light green and (6-month) dark green.

Figure 4

Individual Serum Protein Abundance Change and Statistical Significance at 1-month and 6-Months After Third Vaccination. Each graphed point represents a serum protein marker with detectable change from pre-vaccination levels. Statistical significance (P<0.05) is depicted on the y-axes and Log2 abundance change on the X-axes. Lines of significance (p<0.05 and abundance change <0.2 or >0.2 m) are depicted by dashed lines. Responses in sera from male recipients are shown in panels (A–D), responses in serum from female recipients are shown in the bottom panels (E–H). (A, B, E, F) Responses 1 month after vaccination. (C, D, G, H) 6-month responses. Significant marker changes are depicted with blue dots; grey dots depict marker abundance changes that did not reach significance. N values are listed in each quadrant for significant marker changes.

Sera collected from the male recipients of mRNA-1273 1 month post-third vaccination demonstrated upregulation of 11 markers and downregulation of 14, while sera from female recipients showed upregulation of 14 markers and downregulation of 472 (Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S1A, B). By 6 months, sera from the male recipients of mRNA-1273 showed upregulated 232 protein markers and downregulated 29, while the sera from the female recipient group demonstrated upregulated 102 markers and downregulated 255 (Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S1A, B).

The sera from the male recipients of BNT162b2 showed upregulation of 9 markers at 1-month and downregulation of 218 markers post-third vaccination, while sera from the female recipient cohort demonstrated upregulated 38 markers and downregulated 362 proteins (Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S1A, B). At 6-months post-third vaccination, sera from male recipients showed upregulated 83 markers and downregulated 220, while sera from female recipients demonstrated upregulated 172 markers and downregulated 229 (Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S1A, B).

When evaluated at the cohort level, sera from male recipients of either vaccine at 1-month post-third vaccination demonstrated 1 common upregulated marker (UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48), and 1 common downregulated marker (CXCL8, interleukin-8) (Figure 3). In sera from the female recipient cohorts, 7 markers were upregulated (UBE2D1|UBB, CHAC1, LEP, CST5, CST2, INS) and 342 markers downregulated (Figure 3). By 6-months, sera from male recipients of either vaccine upregulated 61 markers and downregulated 18, while sera from female recipients of either vaccine demonstrated upregulation of 86 markers and downregulation of 177 (Figure 3; Table 4; Supplementary Tables S1A, B). Upregulation of UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 was common to sera from all recipient cohorts at 1-month after third vaccination, regardless of sex assigned at birth or vaccine received (Figure 3).

Table 4

| Upregulated mRNA-1273 Female Recipients (1-month) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Marker | Abundance (RFU) | Significance (p) |

| UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 | UBE2D1|UBB | 0.262310471 | 0.028873413 |

| No protein | 0.260175482 | 0.004812444 | |

| Cystatin-S | CST4 | 0.238394992 | 0.010329505 |

| Melittin.VESMG | MELT | 0.234682716 | 0.012103636 |

| D-dimer | FGA|FGB|FGG | 0.229641179 | 0.003727817 |

| Cystatin-D | CST5 | 0.226042814 | 0.00631462 |

| Band 4.1-like protein 1 | EPB41L1 | 0.224335353 | 0.046323173 |

| Insulin | INS | 0.222642643 | 0.015592254 |

| Histatin-3 | HTN3 | 0.220599779 | 0.010398185 |

| Glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 | CHAC1 | 0.210679991 | 0.028781324 |

| Upregulated mRNA-1273 Male Recipients (1-month) | |||

| Name | Marker | Abundance (RFU) | Significance (p) |

| Porphobilinogen deaminase | HMBS | 0.386411533 | 0.037515731 |

| Tubulin-specific chaperone cofactor E-like protein | TBCEL | 0.331158567 | 0.044087199 |

| Band 4.1-like protein 1 | EPB41L1 | 0.322041671 | 0.042732449 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C 2 | AGO2 | 0.318949382 | 0.049328952 |

| Flavin reductase (NADPH) | BLVRB | 0.317039757 | 0.03549251 |

| UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 | UBE2D1|UBB | 0.312316601 | 0.040253001 |

| Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase IB subunit gamma | PAFAH1B3 | 0.311850831 | 0.034457691 |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 14 | USP14 | 0.310442854 | 0.025334095 |

| Tropomodulin-1 | TMOD1 | 0.284304196 | 0.029963826 |

| Insulin | INS | 0.230907349 | 0.043061194 |

| Upregulated BNT162b2 Female Recipients (1-month) | |||

| Name | Marker | Abundance (RFU) | Significance (p) |

| UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 | UBE2D1|UBB | 0.607793151 | 2.04E-05 |

| Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase | GAA | 0.399913314 | 1.34E-05 |

| Matrix Gla protein | MGP | 0.380325892 | 0.000263212 |

| Cancer/testis antigen 1 | CTAG1A|CTAG1B | 0.372971351 | 0.000292772 |

| 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | PGD | 0.361802534 | 0.003981293 |

| Glucagon | GCG | 0.358596605 | 0.000498532 |

| Proenkephalin-A | PENK | 0.355051683 | 0.001395606 |

| Glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 | CHAC1 | 0.346030491 | 0.003767481 |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | PCBP2 | 0.335035501 | 0.008597658 |

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 | TIMP3 | 0.310196296 | 0.000501893 |

| Upregulated BNT162b2 Male Recipients (1-month) | |||

| Name | Marker | Abundance (RFU) | Significance (p) |

| UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 | UBE2D1|UBB | 0.319356416 | 0.006160708 |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase 1C | ADH1C | 0.28002833 | 0.019782399 |

| Glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 | CHAC1 | 0.278445535 | 0.016013345 |

| Cytochrome P450 2C19 | CYP2C19 | 0.260331428 | 0.028872966 |

| Cancer/testis antigen 1 | CTAG1A|CTAG1B | 0.244254885 | 0.005766592 |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase 4 | ADH4 | 0.240887034 | 0.024632752 |

| Sorbitol dehydrogenase | SORD | 0.227359432 | 0.017601475 |

| Formimidoyltransferase-cyclodeaminase | FTCD | 0.216772387 | 0.010574406 |

| Apolipoprotein A-V | APOA5 | 0.208358558 | 0.002681697 |

Top 10 markers upregulated 1-month post-third vaccination.

Sorted for p values first, then largest (abundance) change.

Evaluation of the 10 most significant (highest statistical significance/abundance change) proteomic markers upregulated in sera at 1-month after the third dose of vaccine demonstrated that both vaccine groups modulated sets of vaccine-type associated markers, regardless of sex assigned at birth. Specifically, sera from both mRNA-1273 recipient cohorts showed upregulated UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 (UBE2D1|UBB), Insulin (INS) and Band 4.1-like protein1 (EPB41L1), while sera from both BNT162b2 recipient cohorts showed upregulated UB2D1/PolyUbiquitin K48 (UBE2D1|UBB), Glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1), and Cancer/testis antigen 1 (CTAG1A|CTAG1B) (Table 4).

3.3 Proteomics assessments of biological pathways and processes

Biological pathways were assessed based on observed proteomic marker changes according to vaccine received and sex assigned at birth. Proteins with significant changes between pre-third dose and 1-month or 6-months after third dose of vaccine were assessed through REACTOME and KEGG databases to evaluate differential pathways and cellular processes impacted (31, 32). A complete accounting at the cohort level of pathways up- and downregulated in 6-month sera compared to pre-third-dose sera measurements are listed in Table 5.

Table 5

| Upregulated Pathways | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio | FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Female Recipients |

Amyloid fiber formation | 30.328125 | 0.01268247 | ||

| Common Pathway of Fibrin Clot Formation | 48.525 | 0.00558661 | |||

| Formation of Fibrin Clot (Clotting Cascade) | 27.7285714 | 0.01468566 | |||

| GRB2:SOS provides linkage to MAPK signaling for Integrins | 80.875 | 0.00291728 | |||

| p130Cas linkage to MAPK signaling for integrins | 34.6607143 | 0.00973617 | |||

| Regulation of TLR by endogenous ligand | 64.7 | 0.00360031 | |||

| Salivary secretion | 44.6206897 | 0.00223322 | |||

| Toll-like Receptor Cascades | 16.0148515 | 0.00360031 | |||

| MAP2K and MAPK activation | 34.6607143 | 0.00973617 | |||

| Oncogenic MAPK signaling | 26.2297297 | 0.01640566 | |||

| Paradoxical activation of RAF signaling by kinase inactive BRAF | 35.9444444 | 0.00943464 | |||

| Platelet Aggregation (Plug Formation) | 35.9444444 | 0.00943464 | |||

| Signaling by BRAF and RAF fusions | 28.5441177 | 0.01429216 | |||

| Signaling by high-kinase activity BRAF mutants | 38.82 | 0.00943464 | |||

| Signaling by moderate kinase activity BRAF mutants | 35.9444444 | 0.00943464 | |||

| Signaling by RAS mutants | 33.4655172 | 0.01006548 | |||

| Synthesis, secretion, and deacylation of Ghrelin | 53.9166667 | 0.0471068 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio | FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Female Recipients |

Cap-dependent Translation Initiation | 9.55485232 | 0.0020531 | ||

| Eukaryotic Translation Elongation | 14.3322785 | 3.43E-04 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Initiation | 9.55485232 | 0.0020531 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 14.955421 | 3.19E-04 | |||

| Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 13.7589873 | 3.78E-04 | |||

| GTP hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit | 10.1169025 | 0.00158428 | |||

| Infectious disease | 4.89394875 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Influenza Infection | 10.1918425 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Influenza Life Cycle | 10.289841 | 3.96E-04 | |||

| Influenza Viral RNA Transcription and Replication | 11.4658228 | 9.45E-04 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 14.955421 | 3.19E-04 | |||

| L13a-mediated translational silencing of Ceruloplasmin expression | 10.4234753 | 0.00144894 | |||

| Major pathway of rRNA processing in the nucleolus and cytosol | 9.29661307 | 3.51E-05 | |||

| Metabolism of RNA | 4.45020519 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| mRNA Splicing | 7.37088608 | 3.43E-04 | |||

| mRNA Splicing - Major Pathway | 7.16613924 | 3.78E-04 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) enhanced by the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 13.838062 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) independent of the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 14.3322785 | 3.43E-04 | |||

| Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) | 13.838062 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Peptide chain elongation | 16.3797468 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA | 6.99135536 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Regulation of expression of SLITs and ROBOs | 7.05589094 | 0.00116369 | |||

| Ribosome | 11.0959575 | 0.0010946 | |||

| rRNA processing | 7.64388186 | 0.00653237 | |||

| rRNA processing in the nucleus and cytosol | 8.38962643 | 0.00394799 | |||

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 10.1169025 | 0.00158428 | |||

| Selenocysteine synthesis | 16.3797468 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| Signaling by ROBO receptors | 4.77742616 | 0.01318081 | |||

| Spliceosome | 7.29643268 | 0.0024757 | |||

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 11.4658228 | 9.45E-04 | |||

| Viral mRNA Translation | 17.1987342 | 2.17E-04 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Female Recipients |

Downregulation of SMAD2/3:SMAD4 transcriptional activity | 32.6610577 | 0.0475592 | ||

| Negative regulators of DDX58/IFIH1 signaling | 24.6141304 | 0.0284525 | |||

| Synthesis, secretion, and deacylation of Ghrelin | 35.3828125 | 0.0475592 | |||

| TICAM1, RIP1-mediated IKK complex recruitment | 30.328125 | 0.04755928 | |||

| Downregulation of SMAD2/3:SMAD4 transcriptional activity | 32.6610577 | 0.04755928 | |||

| Negative regulators of DDX58/IFIH1 signaling | 24.6141304 | 0.0284525 | |||

| Synthesis, secretion, and deacylation of Ghrelin | 35.3828125 | 0.0475592 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Female Recipients |

Eukaryotic Translation Elongation | 8.5131579 | 0.01429319 | ||

| Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 7.402746 | 0.04432762 | |||

| Glycolysis | 6.00928793 | 0.04205984 | |||

| Infectious disease | 3.11456996 | 0.01609754 | |||

| Influenza Infection | 5.29707602 | 0.03293579 | |||

| Innate Immune System | 1.8888979 | 0.01609754 | |||

| Metabolism of RNA | 3.10982937 | 0.00260869 | |||

| mRNA Splicing | 5.20248538 | 0.00260869 | |||

| mRNA Splicing - Major Pathway | 5.35112782 | 0.00260869 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) enhanced by the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 7.04537205 | 0.023371 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) independent of the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 7.09429825 | 0.04744206 | |||

| Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) | 7.04537205 | 0.023371 | |||

| Peptide chain elongation | 9.72932331 | 0.00743626 | |||

| Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA | 4.98331194 | 0.00260869 | |||

| Purine metabolism | 4.00619195 | 0.023371 | |||

| Purine ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthesis | 17.0263158 | 0.04432762 | |||

| Regulation of expression of SLITs and ROBOs | 4.19109312 | 0.04744206 | |||

| Selenocysteine synthesis | 8.10776942 | 0.03293579 | |||

| Signaling by ROBO receptors | 3.90186404 | 0.01854041 | |||

| Viral mRNA Translation | 8.5131579 | 0.02911311 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Male Recipients |

None detected | NA | NA | ||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Male Recipients |

Activation of the mRNA upon binding of the cap-binding complex and eIFs, and subsequent binding to 43S | 7.41395539 | 6.16E-04 | ||

| Cap-dependent Translation Initiation | 9.03575813 | 3.84E-07 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Elongation | 8.34069982 | 4.07E-04 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Initiation | 9.03575813 | 3.84E-07 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 7.61542157 | 0.00141979 | |||

| Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 8.00707182 | 4.43E-04 | |||

| Formation of the ternary complex, and subsequently, the 43S complex | 7.50662983 | 0.00521615 | |||

| GTP hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit | 8.83132922 | 1.26E-06 | |||

| HIV Infection | 2.94377641 | 0.02549153 | |||

| HIV Life Cycle | 4.09452536 | 0.01282603 | |||

| Infectious disease | 3.3566231 | 1.09E-04 | |||

| Influenza Infection | 5.56046654 | 6.58E-04 | |||

| Influenza Life Cycle | 5.77433064 | 0.00114598 | |||

| Influenza Viral RNA Transcription and Replication | 5.83848987 | 0.00704071 | |||

| Interconversion of nucleotide di- and triphosphates | 6.82420894 | 0.00819223 | |||

| Intracellular signaling by second messengers | 2.53199816 | 0.01448855 | |||

| ISG15 antiviral mechanism | 4.69164365 | 0.04808094 | |||

| L13a-mediated translational silencing of Ceruloplasmin expression | 9.09894525 | 1.13E-06 | |||

| M Phase | 2.72968358 | 0.04657549 | |||

| Major pathway of rRNA processing in the nucleolus and cytosol | 5.41018366 | 0.00471349 | |||

| Metabolism | 3.19917253 | 8.21E-06 | |||

| Metabolism of nucleotides | 4.58151117 | 4.43E-04 | |||

| Metabolism of porphyrins | 10.0088398 | 0.01798475 | |||

| Metabolism of RNA | 3.19917253 | 8.21E-06 | |||

| mRNA Splicing | 4.51787907 | 4.43E-04 | |||

| mRNA Splicing - Major Pathway | 4.64696133 | 4.34E-04 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) enhanced by the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 6.90264812 | 8.70E-04 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) independent of the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 7.29811234 | 0.00179384 | |||

| Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) | 6.90264812 | 8.70E-04 | |||

| Peptide chain elongation | 9.53222836 | 1.56E-04 | |||

| PI5P Regulates TP53 Acetylation | 15.0132597 | 0.02311676 | |||

| PIP3 activates AKT signaling | 2.43721748 | 0.04133459 | |||

| Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA | 4.57721331 | 1.39E-04 | |||

| Protein ubiquitination | 5.26781041 | 0.00539683 | |||

| Purine metabolism | 3.23815405 | 0.01974497 | |||

| Purine ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthesis | 12.5110497 | 0.04201052 | |||

| Regulation of expression of SLITs and ROBOs | 4.23450914 | 0.00255575 | |||

| Regulation of TP53 Activity through Acetylation | 15.0132597 | 0.02311676 | |||

| Ribosomal scanning and start codon recognition | 7.41395539 | 6.16E-04 | |||

| Ribosome | 5.65015149 | 0.00819223 | |||

| RNA transport | 5.08261395 | 1.81E-04 | |||

| rRNA processing | 4.44837324 | 0.01450373 | |||

| rRNA processing in the nucleus and cytosol | 4.88236087 | 0.00819223 | |||

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 5.15160871 | 0.01410805 | |||

| Selenocysteine synthesis | 8.34069982 | 8.58E-04 | |||

| Signaling by ROBO receptors | 3.64905617 | 0.00142896 | |||

| Spliceosome | 3.6395781 | 0.04657549 | |||

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 5.83848987 | 0.00704071 | |||

| Synthesis of active ubiquitin: roles of E1 and E2 enzymes | 5.77433064 | 0.01811131 | |||

| Translation | 4.22059509 | 4.43E-04 | |||

| Translation initiation complex formation | 7.69910752 | 5.05E-04 | |||

| Viral mRNA Translation | 8.75773481 | 6.54E-04 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Male Recipients |

APC/C:Cdc20 mediated degradation of Cyclin B | 100.644444 | 0.03847957 | ||

| APC-Cdc20 mediated degradation of Nek2A | 111.827161 | 0.03595134 | |||

| Biological oxidations | 19.3547009 | 0.01611921 | |||

| Chemical carcinogenesis | 35.1085271 | 0.02213348 | |||

| Downregulation of SMAD2/3:SMAD4 transcriptional activity | 77.4188034 | 0.04931422 | |||

| Drug metabolism | 45.7474748 | 0.01611921 | |||

| Ethanol oxidation | 91.4949495 | 0.04110933 | |||

| Phase I - Functionalization of compounds | 41.9351852 | 0.01611921 | |||

| RA biosynthesis pathway | 71.8888889 | 0.04931422 | |||

| TICAM1, RIP1-mediated IKK complex recruitment | 71.8888889 | 0.04931422 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| BNT162b2 Male Recipients |

E3 ubiquitin ligases ubiquitinate target proteins | 12.5024155 | 0.04476852 | ||

| Eukaryotic Translation Elongation | 10.9396135 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 11.4152489 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 10.502029 | 0.04958801 | |||

| Influenza Infection | 8.75169082 | 0.03633001 | |||

| Influenza Life Cycle | 8.41508733 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Metabolism | 1.88935756 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Metabolism of RNA | 3.59658527 | 0.03959885 | |||

| Negative regulators of DDX58/IFIH1 signaling | 11.4152489 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) enhanced by the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 11.3168416 | 0.03633001 | |||

| Nonsense Mediated Decay (NMD) independent of the Exon Junction Complex (EJC) | 10.9396135 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) | 11.3168416 | 0.03633001 | |||

| Peptide chain elongation | 12.5024155 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA | 5.60321668 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Regulation of expression of SLITs and ROBOs | 6.05886288 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Selenocysteine synthesis | 12.5024155 | 0.04476852 | |||

| Viral mRNA Translation | 13.1275362 | 0.04476852 | |||

| B. Downregulated Pathways | |||||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Female Recipients |

Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 2.19549862 | 0.04949487 | ||

| Adaptive Immune System | 1.47596546 | 0.04947068 | |||

| FoxO signaling pathway | 2.13847268 | 0.04814867 | |||

| SHC1 events in ERBB2 signaling | 3.76371191 | 0.04814867 | |||

| L13a-mediated translational silencing of Ceruloplasmin expression | 3.04138336 | 0.04814867 | |||

| Retrograde neurotrophin signaling | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| EGFR Transactivation by Gastrin | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| SHC-related events triggered by IGF1R | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| Unblocking of NMDA receptors, glutamate binding and activation | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| CREB phosphorylation through the activation of CaMKII | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| Ras activation upon Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptor | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| CD209 (DC-SIGN) signaling | 4.48060942 | 0.04814867 | |||

| RHO GTPases activate PAKs | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| Activated NTRK2 signals through RAS | 5.5758695 | 0.04814867 | |||

| Choline metabolism in cancer | 2.66929923 | 0.04755468 | |||

| Ion homeostasis | 3.96180201 | 0.04009573 | |||

| mTOR signaling pathway | 2.28103752 | 0.03906048 | |||

| Olfactory transduction | 4.82527168 | 0.03519761 | |||

| Neurotransmitter receptors and postsynaptic signal transmission | 2.78793475 | 0.03519761 | |||

| Listeria monocytogenes entry into host cells | 4.82527168 | 0.03519761 | |||

| Signaling by NTRK3 (TRKC) | 4.82527168 | 0.03519761 | |||

| B cell receptor signaling pathway | 2.65389943 | 0.03355829 | |||

| MET activates RAS signaling | 6.27285319 | 0.0335385 | |||

| MET activates RAP1 and RAC1 | 6.27285319 | 0.0335385 | |||

| Activated NTRK3 signals through RAS | 6.27285319 | 0.0335385 | |||

| Signaling to ERKs | 3.65916436 | 0.03257863 | |||

| Translation | 2.26729633 | 0.03238849 | |||

| Epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection | 3.05165831 | 0.03211109 | |||

| Oncogenic MAPK signaling | 3.05165831 | 0.03211109 | |||

| Proteoglycans in cancer | 1.96611816 | 0.03114849 | |||

| Signaling by ERBB2 | 2.91760613 | 0.0271399 | |||

| Eukaryotic Translation Initiation | 3.13642659 | 0.02712832 | |||

| Cap-dependent Translation Initiation | 3.13642659 | 0.02712832 | |||

| Synaptic vesicle cycle | 3.81825846 | 0.02674081 | |||

| Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 2.64120134 | 0.02553008 | |||

| Long-term potentiation | 3.46088452 | 0.02553008 | |||

| FCERI mediated Ca+2 mobilization | 4.42789637 | 0.02553008 | |||

| Signaling by RAS mutants | 3.46088452 | 0.02553008 | |||

| Regulation of signaling by CBL | 4.42789637 | 0.02553008 | |||

| Cholinergic synapse | 3.22603878 | 0.02372978 | |||

| ErbB signaling pathway | 2.47380126 | 0.02190311 | |||

| GRB2 events in EGFR signaling | 7.16897507 | 0.02162445 | |||

| Cell-extracellular matrix interactions | 7.16897507 | 0.02162445 | |||

| MAP2K and MAPK activation | 3.58448754 | 0.02162445 | |||

| Response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+ | 2.19245354 | 0.02153177 | |||

| Adherens junction | 2.87505771 | 0.02148228 | |||

| Glioma | 3.05992838 | 0.02148228 | |||

| Signaling by BRAF and RAF fusions | 3.32092228 | 0.02071388 | |||

| GTP hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit | 3.32092228 | 0.02071388 | |||

| Tie2 Signaling | 4.70463989 | 0.02048885 | |||

| Role of LAT2/NTAL/LAB on calcium mobilization | 5.70259381 | 0.02025908 | |||

| Chemokine signaling pathway | 2.16698565 | 0.01985779 | |||

| TGF-beta receptor signaling activates SMADs | 4.18190212 | 0.01863291 | |||

| Signaling by moderate kinase activity BRAF mutants | 3.71724633 | 0.01863291 | |||

| Paradoxical activation of RAF signaling by kinase inactive BRAF | 3.71724633 | 0.01863291 | |||

| Activation of the mRNA upon binding of the cap-binding complex and eIFs, and subsequent binding to 43S | 3.71724633 | 0.01863291 | |||

| Regulation of actin dynamics for phagocytic cup formation | 3.42155628 | 0.01829587 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 3.00006022 | 0.01693218 | |||

| Signaling by NTRK1 (TRKA) | 2.84053729 | 0.016891 | |||

| EPH-Ephrin signaling | 2.71823638 | 0.01625992 | |||

| Downstream signal transduction | 3.86021735 | 0.01563779 | |||

| Translation initiation complex formation | 3.86021735 | 0.01563779 | |||

| Platelet Aggregation (Plug Formation) | 3.86021735 | 0.01563779 | |||

| Formation of Incision Complex in GG-NER | 4.39099723 | 0.01495995 | |||

| Signaling by Erythropoietin | 4.39099723 | 0.01495995 | |||

| MET receptor recycling | 6.27285319 | 0.01446396 | |||

| Signaling by VEGF | 2.66121044 | 0.01417322 | |||

| Shigellosis | 3.13642659 | 0.0129849 | |||

| DAP12 interactions | 3.64230185 | 0.0129849 | |||

| Signaling by high-kinase activity BRAF mutants | 4.01462604 | 0.0129849 | |||

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 2.19549862 | 0.01177427 | |||

| Pathogenic Escherichia coli infection | 3.76371191 | 0.01048107 | |||

| Fc epsilon RI signaling pathway | 3.07241789 | 0.00964524 | |||

| Innate Immune System | 1.44981198 | 0.00936362 | |||

| GAB1 signalosome | 6.96983687 | 0.00893579 | |||

| Deadenylation of mRNA | 6.96983687 | 0.00893579 | |||

| Macroautophagy | 3.89349508 | 0.00870537 | |||

| RHO GTPases Activate WASPs and WAVEs | 4.87888581 | 0.00870537 | |||

| Regulation of KIT signaling | 5.79032602 | 0.00829642 | |||

| FCERI mediated MAPK activation | 4.36372396 | 0.00827695 | |||

| Neutrophil degranulation | 1.7219597 | 0.00827695 | |||

| Fcgamma receptor (FCGR) dependent phagocytosis | 3.20315907 | 0.00743717 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 5.16587909 | 0.00639158 | |||

| Signaling by NTRK2 (TRKB) | 4.56207504 | 0.00624723 | |||

| Interferon Signaling | 2.53733387 | 0.00615989 | |||

| PECAM1 interactions | 6.27285319 | 0.00552616 | |||

| Ribosomal scanning and start codon recognition | 4.18190212 | 0.00552616 | |||

| SHC1 events in EGFR signaling | 7.84106648 | 0.00547587 | |||

| Focal adhesion | 2.2303478 | 0.00504074 | |||

| Budding and maturation of HIV virion | 5.48874654 | 0.00504074 | |||

| Signaling by NTRKs | 2.89516301 | 0.00504074 | |||

| VEGFA-VEGFR2 Pathway | 3.02827395 | 0.00504074 | |||

| Interleukin-3, Interleukin-5 and GM-CSF signaling | 3.63165184 | 0.00504074 | |||

| Antigen activates B Cell Receptor (BCR) leading to generation of second messengers | 4.77931671 | 0.00504074 | |||

| Oxytocin signaling pathway | 3.08140157 | 0.00474565 | |||

| Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells | 3.50112736 | 0.00403216 | |||

| RET signaling | 4.51645429 | 0.00363104 | |||

| EGFR downregulation | 5.85466297 | 0.00347741 | |||

| Trafficking of AMPA receptors | 5.85466297 | 0.00347741 | |||

| Glutamate binding, activation of AMPA receptors and synaptic plasticity | 5.85466297 | 0.00347741 | |||

| Integrin alphaIIb beta3 signaling | 5.28240268 | 0.00279959 | |||

| Integrin signaling | 5.28240268 | 0.00279959 | |||

| Vasopressin-regulated water reabsorption | 4.90918945 | 0.00201276 | |||

| Platelet activation | 3.24457923 | 0.00183056 | |||

| Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases | 1.87314366 | 0.00176539 | |||

| RHO GTPase Effectors | 2.57949103 | 0.00159805 | |||

| Translocation of SLC2A4 (GLUT4) to the plasma membrane | 4.64655792 | 0.00148823 | |||

| Costimulation by the CD28 family | 3.96180201 | 0.00148823 | |||

| ISG15 antiviral mechanism | 4.31258657 | 0.00141757 | |||

| Insulin signaling pathway | 3.01096953 | 0.00115283 | |||

| DAP12 signaling | 5.3767313 | 0.00115283 | |||

| CD28 co-stimulation | 5.3767313 | 0.00115283 | |||

| Signaling by MET | 3.42155628 | 0.00115283 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 3.42155628 | 0.00115283 | |||

| Erythropoietin activates RAS | 7.31832872 | 0.00102824 | |||

| Antiviral mechanism by IFN-stimulated genes | 4.30138504 | 8.58E-04 | |||

| Hemostasis | 1.84922262 | 7.49E-04 | |||

| Tight junction | 3.58448754 | 4.71E-04 | |||

| Signaling by Rho GTPases | 2.49195538 | 3.24E-04 | |||

| GPVI-mediated activation cascade | 5.5201108 | 1.51E-04 | |||

| Signaling by EGFR | 5.26110267 | 3.34E-05 | |||

| Signaling by SCF-KIT | 5.01828255 | 2.52E-05 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 3.58448754 | 1.07E-05 | |||

| RNA transport | 3.92053324 | 9.13E-06 | |||

| Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation | 2.80525111 | 1.25E-06 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 6.75538035 | 3.21E-07 | |||

| RAB GEFs exchange GTP for GDP on RABs | 6.10331661 | 1.39E-08 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 5.80819739 | 1.05E-11 | |||

| Endocytosis | 3.81825846 | 1.48E-12 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 3.30150168 | 0 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 2.98907769 | 0 | |||

| RAB geranylgeranylation | 7.84106648 | 0 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Female Recipients |

FCERI mediated Ca+2 mobilization | 6.8662826 | 0.03823944 | ||

| GPVI-mediated activation cascade | 5.6028866 | 0.03663942 | |||

| RET signaling | 5.6028866 | 0.03663942 | |||

| Budding and maturation of HIV virion | 7.29542526 | 0.03176858 | |||

| Signaling by NTRKs | 3.59159397 | 0.03081647 | |||

| Retrograde neurotrophin signaling | 10.3757159 | 0.02984514 | |||

| trans-Golgi Network Vesicle Budding | 4.4467354 | 0.02984514 | |||

| Clathrin derived vesicle budding | 4.4467354 | 0.02984514 | |||

| EGFR downregulation | 7.78178694 | 0.0292749 | |||

| DAP12 signaling | 6.67010309 | 0.01943979 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 4.5675706 | 0.01283571 | |||

| Signaling by SCF-KIT | 5.33608247 | 0.01045592 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 8.23953912 | 0.00630182 | |||

| Signaling by EGFR | 6.02460925 | 0.00474016 | |||

| Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation | 2.90004482 | 0.00279803 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.66907217 | 0.00279803 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 3.94142456 | 0.00279803 | |||

| Antigen activates B Cell Receptor (BCR) leading to generation of second messengers | 7.78178694 | 0.00279803 | |||

| RAB GEFs exchange GTP for GDP on RABs | 6.94051268 | 5.31E-05 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 8.97898493 | 1.38E-05 | |||

| RAB geranylgeranylation | 7.58724227 | 1.64E-06 | |||

| Endocytosis | 4.39840132 | 2.97E-08 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 7.78178694 | 1.54E-09 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 3.6036463 | 2.29E-12 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 4.03716766 | 0 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Female Recipients |

Signaling by NTRK2 (TRKB) | 4.39566483 | 0.04439593 | ||

| Constitutive Signaling by EGFRvIII | 5.37247924 | 0.0414074 | |||

| Signaling by EGFRvIII in Cancer | 5.37247924 | 0.0414074 | |||

| Response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+ | 2.34719967 | 0.04084622 | |||

| Retrograde neurotrophin signaling | 7.16330565 | 0.03888623 | |||

| GAB1 signalosome | 7.16330565 | 0.03888623 | |||

| Signaling by NTRK1 (TRKA) | 3.04102599 | 0.03888623 | |||

| SHC-related events triggered by IGF1R | 7.16330565 | 0.03888623 | |||

| CD28 co-stimulation | 4.60498221 | 0.03888623 | |||

| Deadenylation of mRNA | 7.16330565 | 0.03888623 | |||

| COPI-mediated anterograde transport | 3.58165283 | 0.03888623 | |||

| Activated NTRK2 signals through RAS | 7.16330565 | 0.03888623 | |||

| Signaling by the B Cell Receptor (BCR) | 2.68623962 | 0.03888623 | |||

| Intra-Golgi and retrograde Golgi-to-ER traffic | 2.76298932 | 0.0338327 | |||

| Formation of Incision Complex in GG-NER | 4.83523132 | 0.03239498 | |||

| Ribosomal scanning and start codon recognition | 4.17859497 | 0.03239498 | |||

| trans-Golgi Network Vesicle Budding | 3.45373666 | 0.02926044 | |||

| Clathrin derived vesicle budding | 3.45373666 | 0.02926044 | |||

| MET activates RAS signaling | 8.05871886 | 0.02919414 | |||

| Activated NTRK3 signals through RAS | 8.05871886 | 0.02919414 | |||

| Signaling by Rho GTPases | 2.20786818 | 0.02151158 | |||

| Signaling by NTRKs | 2.97552696 | 0.01987525 | |||

| Immune System | 1.340816 | 0.01754536 | |||

| GRB2 events in EGFR signaling | 9.20996441 | 0.01745487 | |||

| DAP12 interactions | 4.15933877 | 0.01745487 | |||

| Cell-extracellular matrix interactions | 9.20996441 | 0.01745487 | |||

| Signaling by MET | 3.22348754 | 0.01745487 | |||

| MHC class II antigen presentation | 3.50379081 | 0.01711049 | |||

| FCERI mediated Ca+2 mobilization | 5.68850743 | 0.01711049 | |||

| Costimulation by the CD28 family | 3.81728788 | 0.01711049 | |||

| Interleukin-3, Interleukin-5 and GM-CSF signaling | 3.81728788 | 0.01711049 | |||

| Synaptic vesicle cycle | 4.90530713 | 0.01622817 | |||

| Vasopressin-regulated water reabsorption | 4.90530713 | 0.01622817 | |||

| FCERI mediated MAPK activation | 4.90530713 | 0.01622817 | |||

| Interferon Signaling | 2.71642209 | 0.01622817 | |||

| Role of LAT2/NTAL/LAB on calcium mobilization | 7.32610806 | 0.01615184 | |||

| Tie2 Signaling | 6.04403915 | 0.01413792 | |||

| Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases | 1.90275306 | 0.00903642 | |||

| Hemostasis | 1.81670541 | 0.00821089 | |||

| Signaling by Erythropoietin | 5.6411032 | 0.00775507 | |||

| ISG15 antiviral mechanism | 4.53302936 | 0.0060236 | |||

| GPVI-mediated activation cascade | 5.15758007 | 0.00561733 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 3.85416989 | 0.00560701 | |||

| Adaptive Immune System | 1.81372701 | 0.00364644 | |||

| Neutrophil degranulation | 1.94884051 | 0.00350327 | |||

| SHC1 events in EGFR signaling | 10.0733986 | 0.00332732 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 6.636592 | 0.00305047 | |||

| Antiviral mechanism by IFN-stimulated genes | 4.60498221 | 0.00283646 | |||

| RNA transport | 3.5256895 | 0.00234402 | |||

| Budding and maturation of HIV virion | 7.051379 | 0.00220985 | |||

| DAP12 signaling | 6.13997628 | 0.00201177 | |||

| Antigen activates B Cell Receptor (BCR) leading to generation of second messengers | 6.13997628 | 0.00201177 | |||

| Innate Immune System | 1.63906146 | 0.00175534 | |||

| EGFR downregulation | 7.52147094 | 0.00168712 | |||

| Signaling by SCF-KIT | 5.06548043 | 6.24E-04 | |||

| Erythropoietin activates RAS | 9.40183867 | 2.85E-04 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.39566483 | 1.04E-04 | |||

| Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation | 2.80303265 | 6.84E-05 | |||

| RAB GEFs exchange GTP for GDP on RABs | 5.66288352 | 2.71E-05 | |||

| Signaling by EGFR | 6.23900815 | 2.70E-05 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.18634746 | 5.29E-06 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 7.43881741 | 3.27E-06 | |||

| RAB geranylgeranylation | 6.44697509 | 1.77E-07 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 5.96942138 | 7.47E-09 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 3.02878024 | 3.82E-12 | |||

| Endocytosis | 4.43813503 | 5.73E-13 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 3.39314478 | 0 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Female Recipients |

ER to Golgi Anterograde Transport | 4.01586207 | 0.04233504 | ||

| COPI-independent Golgi-to-ER retrograde traffic | 7.61176471 | 0.04233504 | |||

| Intra-Golgi and retrograde Golgi-to-ER traffic | 3.69714286 | 0.04233504 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 7.61176471 | 0.04233504 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.23490909 | 0.03679775 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 3.69714286 | 0.02893682 | |||

| Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation | 2.73267081 | 0.02789041 | |||

| RAB geranylgeranylation | 5.823 | 0.0037292 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 5.62608696 | 0.00200224 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 8.95846154 | 9.53E-05 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 6.23037037 | 3.27E-05 | |||

| Endocytosis | 4.1257971 | 4.77E-06 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 3.38697987 | 3.19E-09 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 3.79443609 | 1.50E-10 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Male Recipients |

None Detected | ND | ND | ||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| mRNA-1273 Male Recipients |

Peptide ligand-binding receptors | 10.228094 | 0.04627729 | ||

| Post-translational protein phosphorylation | 10.1048639 | 0.04627729 | |||

| Complement and coagulation cascades | 12.333878 | 0.0353268 | |||

| Activation of C3 and C5 | 71.8888889 | 0.01119387 | |||

| 1-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Male Recipients |

DAP12 signaling | 6.38067061 | 0.04961712 | ||

| Signaling by MET | 3.89800968 | 0.04961712 | |||

| Erythropoietin activates RAS | 8.93293886 | 0.04496226 | |||

| SUMO is transferred from E1 to E2 (UBE2I, UBC9) | 16.0792899 | 0.03298049 | |||

| Integrin alphaIIb beta3 signaling | 7.05232015 | 0.03298049 | |||

| Integrin signaling | 7.05232015 | 0.03298049 | |||

| RHO GTPases Activate WASPs and WAVEs | 7.44411571 | 0.02818226 | |||

| Response to elevated platelet cytosolic Ca2+ | 3.12219222 | 0.02818226 | |||

| Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases | 2.14018327 | 0.02818226 | |||

| InlB-mediated entry of Listeria monocytogenes into host cell | 10.7195266 | 0.02697305 | |||

| FCERI mediated Ca+2 mobilization | 7.88200487 | 0.02517852 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 4.66066375 | 0.02235289 | |||

| Negative regulation of MET activity | 8.37463018 | 0.02035789 | |||

| RNA transport | 4.18731509 | 0.0107186 | |||

| Antigen activates B Cell Receptor (BCR) leading to generation of second messengers | 7.65680473 | 0.00903136 | |||

| Formation of Incision Complex in GG-NER | 8.03964497 | 0.00709878 | |||

| RAB GEFs exchange GTP for GDP on RABs | 5.79433872 | 0.00598092 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.8725121 | 0.00362047 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.17643895 | 0.00313745 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 9.45840585 | 0.00313745 | |||

| Budding and maturation of HIV virion | 10.0495562 | 0.00249234 | |||

| Signaling by EGFR | 6.91582363 | 0.0023029 | |||

| EGFR downregulation | 10.7195266 | 0.00200892 | |||

| Platelet activation, signaling and aggregation | 3.16259326 | 0.00152845 | |||

| RAB geranylgeranylation | 6.69970414 | 3.70E-04 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 9.27651343 | 7.06E-05 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 6.94784133 | 2.25E-06 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 3.41729876 | 3.09E-09 | |||

| Endocytosis | 5.24324672 | 3.23E-10 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 3.82840237 | 2.38E-10 | |||

| 6-month | |||||

| Cohort | Pathway | Enrichment Ratio |

FDR | ||

| BNT162b2 Male Recipients |

Costimulation by the CD28 family | 4.90758514 | 0.03955952 | ||

| RAB GEFs exchange GTP for GDP on RABs | 5.04022258 | 0.03516174 | |||

| InlB-mediated entry of Listeria monocytogenes into host cell | 10.6564706 | 0.03408549 | |||

| Signaling by SCF-KIT | 5.32823529 | 0.03386844 | |||

| FCERI mediated Ca+2 mobilization | 7.83564014 | 0.03386844 | |||

| Negative regulation of MET activity | 8.32536765 | 0.03386844 | |||

| TBC/RABGAPs | 6.1479638 | 0.03386844 | |||

| Golgi-to-ER retrograde transport | 4.63324808 | 0.03386844 | |||

| Endosomal Sorting Complex Required For Transport (ESCRT) | 7.83564014 | 0.03386844 | |||

| Signaling by MET | 4.35946524 | 0.02951796 | |||

| Signaling by Receptor Tyrosine Kinases | 2.22009804 | 0.02905208 | |||

| EGFR downregulation | 10.6564706 | 0.00207877 | |||

| Cargo recognition for clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 5.32823529 | 0.00105399 | |||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | 4.49786096 | 0.00105399 | |||

| Rab-regulation of trafficking | 5.42690632 | 0.00105399 | |||

| Signaling by EGFR | 7.7345351 | 5.09E-04 | |||

| Endocytosis | 4.05409207 | 1.49E-05 | |||

| Vesicle-mediated transport | 3.30779708 | 2.55E-08 | |||

| Membrane Trafficking | 3.70572755 | 1.52E-09 | |||

Cellular pathways and processes impacted by third vaccination.

Enrichment ratio was calculated using the WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt) 2 (30).FDR, False Discovery Rate.

Sera from male recipients of the mRNA-1273 vaccine demonstrated no significantly upregulated or downregulated pathways at 1-month, while sera from female recipients demonstrated an upregulation of 21 (including TLR signaling cascades, fibrin clot formation, and platelet aggregation) and downregulation of 132 pathways, (including membrane and vesical trafficking, platelet activation, and RNA transport) (Figure 5; Table 5; Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5

Cellular Pathways and Processes Impacted by Third Vaccination. Assessment of pathways modulated by vaccination. Upregulated pathways and cellular processes are presented in panel (A), downregulated pathways in panel (B) Pathway assessments utilized both KEGG and REACTOME databases and identified processes are listed to the left of the figures. mRNA-1273 vaccination responses are indicated by purple, BNT162b2 indicated by green. Lighter colors indicate 1-month, darker colors 6-months. Common pathways between 1-month to 6-months and between BNT162b2 to mRNA-1273 vaccine recipient sera are indicated by the boxes.

At 6-months, sera from male recipients of mRNA-1273 demonstrated upregulation of 51 pathways (including class I antigen processing, metabolism of RNA, eucaryotic translation and peptide chain elongation) and downregulation of 4 (including complement activation, coagulation cascades, and peptide ligand receptors). Sera from female recipients of mRNA-1273 demonstrated upregulation of 30 pathways at 6-months (including class I antigen processing, metabolism of RNA, and peptide chain elongation) and downregulation of 25 (including endocytosis, membrane and vesicle trafficking and platelet activation) (Table 5; Figure 5; Supplementary Table S2).

One month after booster, the sera from male recipients of BNT162b2 demonstrated upregulation of 11 pathways (including APC-Cdc20 degradation and TICAM1 and RIP1 signaling) and downregulation of 30 (including platelet activation, membrane trafficking, and RNA transport), while sera from the female recipients demonstrated upregulation of 4 pathways (including TICAM1 and RIP1 mediated signaling) and downregulation of 67 (including membrane and vesical trafficking, platelet activation, and RNA transport) (Table 5; Figure 5; Supplementary Table S2). Upregulated pathways in sera from both male and female recipients of BNT162b2 included TICAM1, RIP1 mediated IKK signaling (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S2).

By 6-months post-third vaccination, sera from the male recipients of BNT162b2 showed upregulation of 17 pathways or processes associated with protein synthesis (mRNA processing and translation), regulation of cellular function (SLIT – ROBO pathway), and suppression of RIG-1 signaling pathway (DDX58/IFIH1) and downregulation of 19 (including membrane trafficking, endocytosis, and EGFR, RTK, MET, CD28, SCF-KIT, and ESCRT signaling). The sera from the female recipients of BNT162b2 demonstrated upregulation of 20 pathways and processes (including innate immune system activation, class I antigen processing, glycolysis and neddylation) and downregulation of 14 (including membrane and vesical trafficking, endocytosis, and platelet activation) (Table 5; Figure 5; Supplementary Table S2).

We evaluated common trends detected in pathways impacted by vaccination and found 17 pathways, including membrane trafficking, endocytosis and EGFR signaling pathways, were downregulated in sera from male recipients of BNT162b2 at 1-month and at 6-months, and 1 upregulated (metabolism) (Figure 6; Table 5). Likewise, sera from female recipients of BNT162b2 demonstrated 12 common pathways downregulated at 1-month and 6-months, most notably platelet activation, vesicle trafficking, endocytosis and signaling by RAB (Figure 6; Table 5). No comparisons were possible between sera from the male recipients of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 at 1-month because no significant pathway changes were noted in the mRNA-1273 group even though there were significant marker changes (Figure 6; Table 5). There was 1 common pathway upregulated in sera from female recipients of either vaccine at 1-month post-third vaccination: synthesis, secretion, and deacylation of Ghrelin (Figure 6; Table 5). Sera from recipients of either vaccine, regardless of sex assigned at birth (except male recipients of mRNA-1273), demonstrated upregulation of translation, peptide chain elongation and RNA metabolism and processing at 6-months (Figure 6; Table 5).

Figure 6

Common Pathways Modulated by Third Vaccination. Common cellular pathways and processes (A) upregulated or (B) downregulated according to BNT162b2 (green) and mRNA-1273 (purple) cohorts at 1-month (light green/purple) and 6-months (dark green/purple) after third vaccination. Number of common pathways (n) are indicated in the boxes.

3.4 Predictive modeling of serological responses

The overarching goal of this study was to investigate the possibility of identifying proteomic markers in pre-boost sera that are predictive of humoral response robustness to vaccination at later timepoints. Predictive modeling was performed as a pilot effort to investigate the utility of machine learning to identify markers or develop models of vaccine responsiveness (Figure 1). Change in anti-spike IgG antibody levels (BAU/mL) in pre-third vaccination and 6-month post-third vaccination sera were analyzed to identify vaccine-recipient samples with either “higher” or “lower” antibody content. The predictive potential of proteomic markers of avidity responses were not analyzed due to the limited range of AI measurements. The sera with the lowest and highest quartile of antibody titers were identified as “lower” and “higher” responders (Figure 7). Specifically, 44 vaccine-recipients with 6-month serum IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike antibody less than 2000 BAU/mL (7 male and 11 female recipients of mRNA-1273, 13 male and 13 female recipients of BNT162b2) were identified as relatively “Lower” responders, and 39 vaccine-recipients with sera containing greater than 5000 BAU/mL (9 male and 10 female recipients of mRNA-1273, and 8 male and 12 female recipients of BNT162b2) were identified as relatively “Higher” responders (Figures 1, 7; Table 6). The demographics of these 2 populations were well-balanced concerning sex assigned at birth and vaccine-received (Table 6).

Figure 7

Serological Antibody Assessment of IgG to SARS-CoV-2 Spike S-2 Protein at Pre-Third Dose and 1, 6 Months after Homologous Third Vaccination. Serology Response (Antibody Content BAU/mL) Test Result Distribution. Test results are broken out into tertiles; Higher responses (red), lower responses (blue), middle responses (white). Grey indicates samples unavailable for testing and there are no data. Column 1: Pre-third vaccination; Column 2: 1-month; Column 3: 6-months. Column 4 lists vaccine-recipient identification numbers.

Table 6

| Lower Serology Responders (<2000 BAU/mL) | Higher Serology Responders (>5000 BAU/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex assigned at birth | Vaccine | Count | Sex assigned at birth | Vaccine | Count |

| Male | mRNA-1273 | 7 | Male | mRNA-1273 | 9 |

| Male | BNT162b2 | 13 | Male | BNT162b2 | 8 |

| Female | mRNA-1273 | 11 | Female | mRNA-1273 | 10 |

| Female | BNT162b2 | 13 | Female | BNT162b2 | 12 |

| Total | 44 | Total | 39 | ||

Selected vaccine-recipient samples to develop model of 6-month post-third vaccination serology.

Random Forest (RF) modeling, which combines outputs of multiple “decision trees” to reach a single result, was used for predictive modeling. Attempts to develop predictive models restricted by vaccine or sex assigned at birth did not return results with sufficient power due to the limitations of small cohort sizes. However, evaluation of the entire dataset as a single cohort returned a productive model that was statistically different from random selection (Figure 1).

An RF model with 85 marker values from the pre-third vaccination sera could predict higher (>5,000 BAU/ml) and lower (<2,000 BAU/mL) responders at month-6 with 79.17% accuracy (Figure 1). The associated markers and comparative changes are listed in Supplementary Table S3 (Figure 7). Protein markers with the highest predictive power (i.e. markers that contributed the most to the model) were associated with complement cascade and activation, signaling by interleukins, tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) apoptotic signaling, IL-17 signaling and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling (Table 7).

Table 7

| Sequence Identification | Protein Symbol | Gene Symbol | Name | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25225.14 | Q9BXU8 | FTHL17 | Ferritin heavy polypeptide-like 17 | |

| 23595.6 | Q8IV20 | LACC1 | Laccase domain-containing protein 1 | |

| 7886.26 | O15269 | SPTLC1 | Serine palmitoyltransferase 1 | Sphingolipid de novo biosynthesis |

| 7871.16 | Q24JP5 | TMEM132A | Transmembrane protein 132A | |

| 3622.33 | Q99538 | LGMN | Legumain | Vitamin D (calciferol) metabolism |

| 5837.49 | P42702 | LIFR | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor | Signaling by Interleukins |

| 2946.52 | P00746 | CFD | Complement factor D | Complement cascade, Alternative complement activation |

| 21742.43 | Q6GQQ9 | OTUD7B | OTU domain-containing protein 7B | TNFR1-induced proapoptotic signaling |

| 7857.22 | P30990 | NTS | Neurotensin/neuromedin N | |

| 2312.13 | HCE000483 | HCE000483 | HCE000483 | |

| 20087.3 | O60613 | SELENOF | 15 kDa selenoprotein | |

| 5708.1 | Q969E1 | LEAP2 | Liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 | |

| 14116.129 | P26447 | S100A4 | Protein S100-A4 | |

| 23371.5 | Q9GZT8 | NIF3L1 | NIF3-like protein 1 | |

| 3622.33 | Q99538 | LGMN | Legumain | Vitamin D (calciferol) metabolism |

| 5837.49 | P42702 | LIFR | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor | Signaling by Interleukins |

| 20535.68 | Q8NFR9 | IL17RE | Interleukin-17 receptor E | IL-17 signaling pathway |

| 11218.84 | P51580 | TPMT | Thiopurine S-methyltransferase | Metabolic disorders of biological oxidation enzymes, Methylation |

| 9176.3 | P15941 | MUC1 | Mucin-1: region 2 | Termination of O-glycan biosynthesis |

| 8039.41 | Q8N128 | FAM177A1 | Protein FAM177A1 | Signaling by Interleukins |

| 7211.2 | P07998 | RNASE1 | Ribonuclease pancreatic | |

| 20120.101 | Q86WK6 | AMIGO1 | Amphoterin-induced protein 1: Extracellular domain | |

| 4133.54 | P10144 | GZMB | Granzyme B | Allograft rejection, Graft-vs-host |

| 25236.11 | Q96S19 | METTL26 | Methyltransferase-like 26 | |

| 7808.5 | O94923 | GLCE | D-glucuronyl C5-epimerase | |

| 6232.54 | P42081 | CD86 | T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD86 | Allograft rejection, Graft-vs-host, CD28 dependent Vav1 pathway, CD28 dependent PI3K/Akt signaling |

| 8091.16 | P48740 | MASP1 | Mannan-binding lectin serine protease 1: Mannan-binding lectin serine protease 1 heavy chain |

Lectin pathway of complement activation, Complement and coagulation cascades |

| 3470.1 | P16581 | SELE | E-selectin | Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) |

| 17441.4 | P09923 | ALPI | Intestinal-type alkaline phosphatase | Thiamine metabolism |

| 22969.12 | P80098 | CCL7 | C-C motif chemokine 7 | IL-17 signaling pathway |

Top 30 markers and pathways that contributed to the predictive model of 6-month post-third vaccination serology responses.

4 Discussion