- 1Center Laboratory, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Department of Respiration, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Centre, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) is a serious condition emerging during the COVID-19 pandemic, strongly associated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Characterized by systemic inflammation affecting multiple organs, MIS-C presents a complex clinical picture including fever, gastrointestinal distress, cardiac dysfunction, and neurological manifestations. Although its exact pathogenesis remains incompletely understood, immune dysregulation is recognized as a central mechanism. This review examines current understanding of MIS-C pathogenesis, focusing on immune dysfunction and viral triggers, particularly SARS-CoV-2. We analyze both innate and adaptive immune responses, cytokine storm dynamics, molecular mimicry, and virus-induced inflammatory cascades. Additionally, we discuss potential immunomodulatory therapeutic strategies and identify future research directions to improve MIS-C management and treatment outcomes.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a severe condition typically emerging 2–6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection (1–3). While rare hyperinflammatory responses were previously documented in pediatric cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), MIS-C demonstrates a distinct clinical characterized by more pronounced gastrointestinal and mucocutaneous involvement. MIS-C presents with fever, abdominal pain, and rash, and cardiovascular manifestations, posing substantial diagnostic challenges (4–7). Its pathophysiology involves dysregulated hyperinflammatory responses to viral exposure, evidenced by elevated inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (8–10). This immune dysregulation likely stems from genetic predispositions interacting with environmental triggers, particularly viral infections. The immune activation pattern shows partial overlap with Kawasaki Disease (KD) but demonstrates distinct cytokine profiles and epidemiological characteristics (11, 12). The temporal delay between SARS-CoV-2 infection and MIS-C onset supports classification as a post-infectious syndrome rather than direct viral pathology, a crucial distinction guiding therapeutic strategies (6, 13–15).

Clinical management remains challenging without standardized protocols. Current guidelines recommend immunomodulatory therapies including intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and corticosteroids, though variable treatment responses necessitate further investigation through controlled trials (16–18). Emerging research focuses on identifying predictive biomarkers to enable personalized treatment approaches (10, 19–21).

Understanding the interplay between viral triggers and immune dysregulation remains essential for elucidating MIS-C pathogenesis. Continued investigation into immunological mechanisms and therapeutic interventions will be critical for improving outcomes and preparing for future pediatric health emergencies.

2 Clinical manifestations and diagnostic criteria of MIS-C

2.1 Characteristic symptom presentations

MIS-C is a severe inflammatory complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with clinical features overlapping KD (19, 22, 23). Key symptoms include persistent fever (present in nearly all cases), rash, conjunctivitis, and gastrointestinal issues such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Cardiovascular manifestations (e.g., shock) and neurological symptoms (e.g., altered mental status or seizures) may also occur, complicating diagnosis (5, 24, 25). Elevated inflammatory markers—including C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and D-dimer—are common and aid in assessing severity (26–28). Some children exhibit acute respiratory symptoms, potentially leading to misdiagnosis as primary respiratory infections (29).

Epidemiological data reveal significant disparities in MIS-C prevalence across populations. Incidence rates are higher among Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic Black children compared to non-Hispanic White children, with variations linked to genetic, socioeconomic, and geographic factors (30–32). Age and gender also influence risk, with peak incidence in children aged 5–12 years and a male predominance (ratio ~1.5:1) (33). These differences underscore the need for population-specific clinical awareness.

Given the symptom overlap with other inflammatory conditions, high suspicion and comprehensive assessment are essential for accurate differentiation. A schematic of MIS-C symptom characteristics is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Symptom characteristics simulation chart of MIS-C following SARS-CoV-2 infection (By Figdraw). This schematic summarizes the multisystem clinical features observed in children with MIS-C following SARS-CoV-2 infection. The characteristic symptoms involve multiple organ systems: Cardiovascular: Myocardial dysfunction (e.g., chest pain), coronary artery dilatation, and arterial inflammation. Gastrointestinal System: Abdominal pain (often colicky), vomiting, and diarrhea (watery stools). Skin and Mucous Membranes: Erythematous rash, non-purulent conjunctivitis, and mucosal involvement. Neurological System: Altered mental status and seizures. Respiratory System: Respiratory distress, cough, and pneumonia. Systemic Symptoms: Persistent fever, fatigue, myalgia, and chills. This comprehensive depiction highlights the systemic hyperinflammation and heterogeneous presentation in MIS-C, which distinguishes it from other pediatric inflammatory conditions.

2.2 Diagnostic approaches

Diagnostic MIS-C relies on clinical evaluation and laboratory testing, based on criteria from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) (34–36). Key requirements include fever lasting ≥ 24 hours, elevated inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or ferritin), and involvement of ≥2 organ systems (e.g., cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or neurological). Providers must exclude alternative causes, such as active infections or other inflammatory syndromes.

Early identification is critical for initiating treatments like intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and corticosteroids. The diagnostic process should account for demographic variations; for instance, higher prevalence in certain populations may warrant adjusted thresholds for inflammatory markers (30, 37). MIS-C typically presents as multi-system inflammation weeks post-SARS-CoV-2 infection, and confirmation involves characteristic markers and organ involvement, as summarized in Table 1.

2.3 Laboratory and imaging evaluations

Laboratory tests are crucial for diagnosing and managing MIS-C. Common findings from these tests often show elevated inflammatory markers, including CRP, procalcitonin, ferritin, and D-dimer, alongside conditions like lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia (38, 39). Additionally, cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) are frequently elevated, suggesting possible heart involvement (40). Imaging studies, especially echocardiography, are vital for evaluating cardiac function and detecting complications like coronary artery dilation or aneurysms, which pose significant risks in MIS-C cases (41). Chest imaging may also be necessary to check for lung involvement. By integrating clinical observations, laboratory results, and imaging findings, healthcare providers can conduct a thorough assessment of the child’s health, which is essential for making informed treatment decisions and monitoring for potential complications. In summary, effectively managing MIS-C requires a comprehensive approach that combines symptom evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging studies to ensure prompt and effective care for this serious condition.

3 Abnormal immune responses

3.1 Mechanisms of autoimmunity and viral cross-reactivity

Autoimmunity arises from genetic, environmental, and immunological imbalances that disrupt immune tolerance, triggering activation of self-reactive T and B cells (42). These cells produce autoantibodies and pro-inflammatory cytokines, driving tissue injury and inflammation (43). Infections can exacerbate such responses, as seen in MIS-C, where viral epitopes induce cross-reactivity:

EBV as Primary Driver: The EBV nuclear antigen 2-derived peptide TVFYNIPPMPL is a dominant cross-reactive epitope. TCRVβ21.3+ CD8+ T cells (expanded in 82% of MIS-C patients) show 3.1-fold stronger reactivity to this EBV epitope than non-EBV antigens. Single-cell TCR sequencing confirms MIS-C T-cell repertoires cluster with EBV-specific (not SARS-CoV-2-specific) TCRs, indicating EBV-directed responses are central to cross-reactivity (44).

SARS-CoV-2 as Potential Initiator: Structural models suggested SARS-CoV-2 spike protein superantigen-like activity, but functional studies show limited T-cell activation by SARS-CoV-2 peptides. Pre-pandemic MIS-C cases indicate spike protein is non-essential. Instead, SARS-CoV-2 may dysregulate TGFβ, impairing TCRVβ21.3+ T-cell cytotoxicity against EBV-infected B cells, promoting viral persistence and inflammation (45).

HLA-Mediated Amplification: HLA risk alleles (e.g., HLA-DRB101, HLA-DQB105), present in 19.4% - 23% of MIS-C patients (absent in controls) and enhance presentation of EBV/host molecular mimics, analogous to HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis (46).

Autoantibody Pathogenesis: Autoantibodies targeting endothelial, myocardial, and gastrointestinal antigens contribute to multi-organ damage. Recent studies link specific autoantibody profiles to cardiac dysfunction in MIS-C, highlighting their role in disease severity (47).

Supporting evidence includes 79.7% EBV seropositivity in MIS-C patients (vs. 56% controls) with elevated anti-EBNA2 IgA, and organ-specific inflammation aligning with EBV/host antigen mimicrysites (44). Infections trigger autoreactive lymphocytes via molecular mimicry or epitope spreading, while inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6) further drive the autoimmune, as observed in lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Understanding these mechanisms—viral cross-reactivity, HLA restriction, and autoantibody effects—is critical for targeted therapies to restore immune tolerance (46).

3.2 Inflammatory cytokine expression

Inflammatory cytokines balance protective immunity and harmful inflammation (48–50). Autoimmune diseases often disrupt this balance, elevating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) that correlate with disease severity (51–54). These cytokines sustain the inflammatory cycle by shaping the immune environment and driving immune cell activation and differentiation. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis, persistent cytokine exposure promotes joint damage and systemic complications (55–57). Consequently, targeting cytokine signaling pathways represents a promising therapeutic strategy to restore pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory balance in autoimmune diseases.

3.3 Immune cell activation status

Immune cell activation status critically shapes immune responses and significantly influences autoimmune disease onset and progression (58–63). In autoimmune diseases, T cells, B cells, and macrophages often exhibit hyperactivation. For example, CD4+ T helper cells differentiate into pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 subsets, releasing cytokines that amplify inflammation and tissue injury. Similarly, B cells produce autoantibodies that further propagate autoimmune pathology. This dysregulation disrupts immune tolerance, activating autoreactive lymphocytes (64–67). Meanwhile, regulatory T cells (Tregs) frequently show impaired function, failing to control inflammatory responses (68–72). Understanding these cellular activation patterns is therefore essential for developing targeted immunotherapies to reestablish immune equilibrium and prevent tissue damage.

4 Virus trigger mechanisms

4.1 Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection

The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 involves complex innate and adaptive interactions (73–75). Infection triggers innate immunity via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) like Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which detect viral components (76, 77). This recognition induces type I and III interferons, creating an antiviral state. However, SARS-CoV-2 evades strong interferon responses compared to SARS-CoV, despite efficient replication (78, 79).

Such evasion delays adaptive immunity, leading to low-affinity antibodies and T-cell hyperactivation that worsen disease outcomes. Additionally, immune dysregulation causes cytokine storms with pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, resulting in tissue damage and respiratory issues (80–83).

As shown in Figure 2, TLR and RLR hyperactivation drives excessive cytokine production, triggering systemic inflammation and multi-organ injury. Acute infection involves innate cell activation and lymphopenia, which normalizes during recovery. In contrast, MIS-C exhibits delayed, exaggerated immune responses with elevated inflammatory markers and tissue damage.

Figure 2. Immunological mechanisms in MIS-C (By Figdraw). MIS-C is a severe inflammatory syndrome associated with infection, characterized by aberrant activation of both innate and adaptive immunity. Innate immunity: TLR2 and TLR4 trigger pro-inflammatory cytokine release; TLR7 and TLR8 detect viral ssRNA, activating type I interferons via the MyD88 pathway; type I interferons bind to IFNAR receptor, activating JAK-STAT signaling and inducing interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) to inhibit viral replication. Adaptive immunity: Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) process viral antigens and present them to naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; activated CD4+ T cells differentiate into subsets such as Th1, secreting cytokines to coordinate immune responses; CD8+ T cells, with CD4+ T cell help, become cytotoxic T lymphocytes that directly kill infected cells; B cells, activated by CD4+ T cells, differentiate into plasma cells that secrete IgM and IgG antibodies through class switching; memory B and T cells are formed to provide long-term immunity. This dysregulated immune activation contributes to the hyperinflammation seen in MIS-C.

Epidemiological studies further reveal that MIS-C cases typically peak 2–6 weeks after community surges of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with incidence rates proportional to transmission levels (84–86).This temporal clustering, with cases surging 2–6 weeks post-infection waves, underscores the importance of monitoring infection spread for early MIS-C detection. For instance, surveillance data indicate a direct correlation between regional COVID-19 incidence and subsequent MIS-C outbreaks, highlighting the need for proactive surveillance to detect early signs of the syndrome (87, 88).

4.2 Effects of viral variants

The emergence of viral variants has important implications for how SARS-CoV-2 causes disease and how effective public health measures can be (89, 90). Variants like Delta and Omicron have shown increased transmissibility and the ability to evade immune responses, which complicates how the body reacts to previous infections or vaccinations (91, 92). For example, spike protein mutations in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) enhance ACE2 binding, facilitating host cell entry (93, 94). Pre-existing immunity from other coronaviruses may impair neutralizing antibodies against variants, potentially exacerbating disease (95, 96). Variants’ ability to partially escape antibodies challenges vaccine efficacy, highlighting the need for updated vaccines. Ongoing surveillance is crucial to understand impacts on spread, severity, and vaccine effectiveness. These variants may also influence MIS-C incidence proportionally to infection waves, as observed in variant-specific outbreaks (97, 98).

4.3 Virus-induced immune hyperreactivity

Virus-induced airway hyperreactivity, especially from respiratory infections, poses a significant risk to children (99, 100). For instance, infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are linked to a higher likelihood of developing asthma and other chronic respiratory issues later in life (101). The causes of this hyperreactivity are complex, including direct viral effects and resulting immune imbalances. After an RSV infection, airway hyperreactivity notably increases, likely resulting from ongoing inflammation, disruption of the airway lining, and release of inflammatory substances. Furthermore, the interaction between viral infections and the body’s immune response can induce a state of heightened airway sensitivity. This increased sensitivity makes the airways more prone to future infections and allergic reactions. This situation underscores the need to better understand the long-term effects of viral infections on respiratory health, particularly in at-risk groups such as infants and young children. Addressing these challenges through preventive strategies, including vaccinations and early interventions, is crucial to reducing the incidence of chronic respiratory diseases associated with viral infections.

4.4 Comparative viral pathogenesis in MIS-C

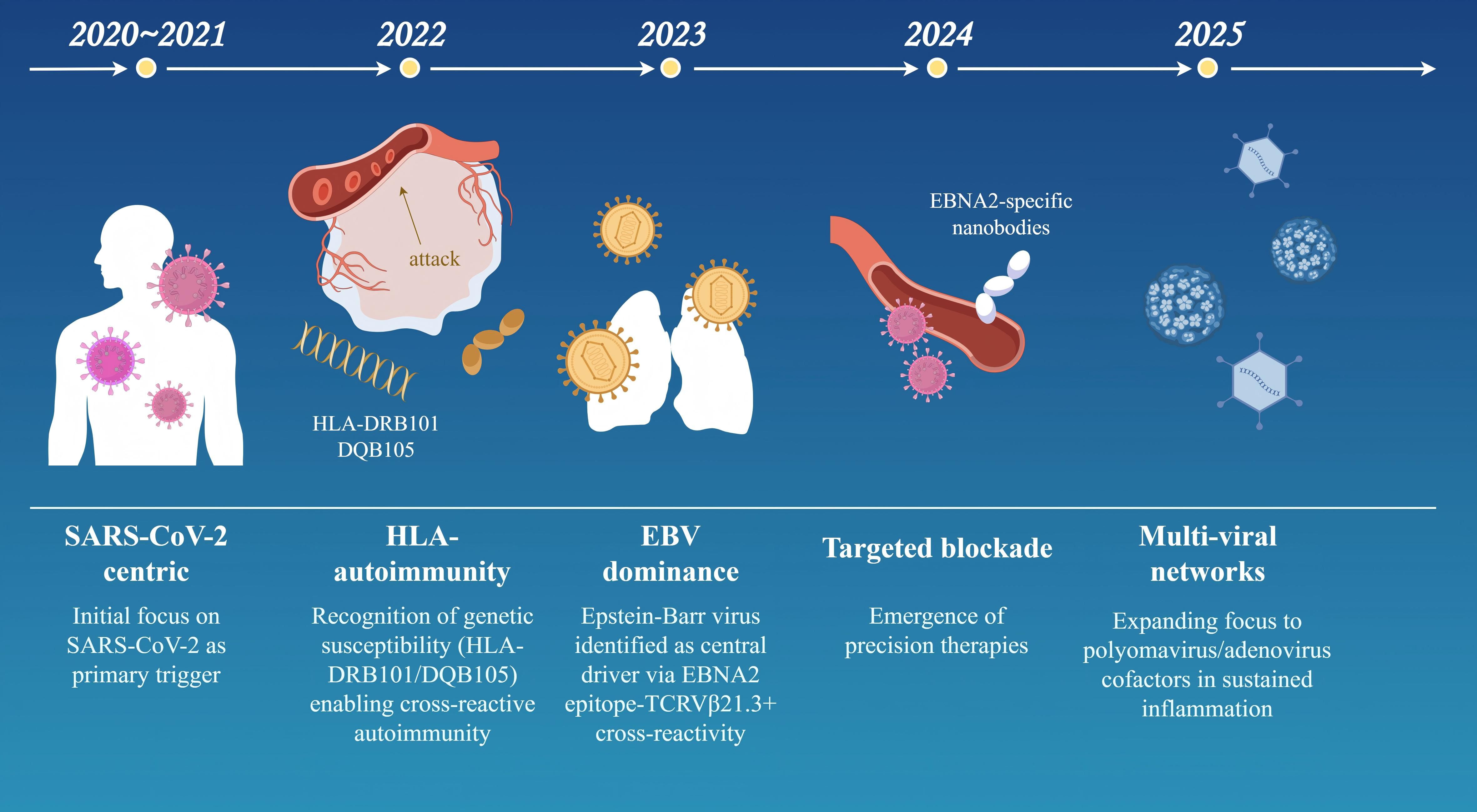

Specific viruses trigger MIS-C through distinct immunopathological mechanisms. SARS-CoV-2 has the strongest causal link (>95% of cases), supported by temporal clustering, high seropositivity, and tissue viral RNA detection. Key mechanisms include spike protein superantigen-like activity driving TCR Vβ 21.3+ T-cell expansion and cytokine storms (elevated IL-6/IL-10/IFN-γ), plus ACE2-mediated endothelial damage via MMP-9 overexpression (20, 51). Unique features include IFN-I suppression and elevated NETosis markers. EBV shows a moderate association (15-20% of cases), often through reactivation evidenced by EBNA-IgG/VCA-IgM serology (102, 103). It contributes via LMP1-induced NF-κB hyperactivation and CD21+ B-cell depletion, exacerbating macrophage activation syndrome -like pathology with hyperferritinemia in co-infections. Elevated TGFβ in MIS-C impairs T cell cytotoxicity against EBV, leading to reactivation and hyper-inflammation (44). Adenovirus involvement is emerging (5-10% of cases), with hexon protein seropositivity linked to MIS-C (104). It triggers HSP60-mediated molecular mimicry against cardiac antigens and immune complex deposition driving complement-mediated NETosis, often with higher myocarditis incidence (troponin-I >1.0 ng/mL). Common pathways include triphasic immune dysregulation: viral endocytosis (via ACE2/LAT1), delayed IFN-I responses promoting pyroptosis, and TRAIL+ CD4+ T-cell cytotoxicity causing multi-organ damage. Genetic susceptibility (e.g., HLA-DRB1*11:01 allele, conferring 9.3× increased risk) further unifies these mechanisms. Milestones in MIS-C Pathogenesis are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Conceptual evolution of MIS-C pathogenesis (2020–2025) (By Figdraw). This timeline model outlines key milestones in the understanding of MIS-C pathogenesis over a five-year period, reflecting shifts in research focus and mechanistic insights: 2020–2021 (SARS−CoV−2−centric phase): Initial emphasis on SARS−CoV−2 as the primary trigger, highlighting viral spike protein interactions and systemic cytokine storms. 2022 (HLA and autoimmunity): Recognition of genetic susceptibility linked to HLA−DRB101/DQB105 haplotypes, facilitating cross−reactive autoimmune responses. 2023 (Epstein–Barr virus dominance): Identification of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) as a central driver, mediated by EBNA2 epitope cross−reactivity with TCR Vβ21.3+ T cells. 2024 (Targeted therapeutic blockade): Emergence of precision immunotherapies, including EBNA2−specific nanobodies designed to inhibit vascular leakage and hyperinflammation. 2025 (Multi−viral network hypothesis): Expanding evidence for co−factors such as polyomaviruses and adenoviruses in sustaining inflammatory networks and disease severity. The model underscores the progressive elucidation of synergistic viral, genetic, and immunologic factors in MIS-C.

5 Comparisons with other pediatric inflammatory diseases

5.1 Distinguishing MIS-C from sepsis

Differentiating MIS-C from sepsis remains challenging due to overlapping features like fever, gastrointestinal distress, and cardiovascular instability. However, key distinctions exist: MIS-C patients are generally older (median age 10 years vs. 4 years for sepsis) and exhibit prolonged fever with prominent mucocutaneous and gastrointestinal symptoms. Laboratory findings further aid differentiation-sepsis often shows elevated leukocyte counts and procalcitonin, while MIS-C commonly presents with thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, and hyperfibrinogenemia. Myocardial dysfunction is more severe in MIS-C and can be quantified using the Vasoactive Inotropic Score (VIS) (105). The MISSEP scoring system, with high sensitivity and specificity, assists clinicians in this distinction (16). This differentiation is vital as it informs appropriate treatment strategies; sepsis typically necessitates immediate antibiotic therapy, whereas the management of MIS-C may involve immunomodulatory treatments such as IVIG and corticosteroids.

5.2 Similarities and differences with Kawasaki disease

MIS-C and KD (KD) share clinical features (e.g., prolonged fever, rash, conjunctivitis, mucosal changes, and coronary artery complications), yet their pathogenesis and inflammatory profiles differ fundamentally. KD is a vasculitis treated with IVIG and aspirin, while MIS-C is a post-infectious hyperinflammatory syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2. MIS-C demonstrates distinct cytokine patterns, such as elevated CXCL9, rarely seen in KD (106, 107). Management strategies for MIS-C are evolving, potentially incorporating biologics tailored to its unique immunopathology.

5.3 Comparison with other virus-related diseases

MIS-C parallels other hyperinflammatory conditions like macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) in its “cytokine storm” signature and multi-organ involvement (4). However, unlike typical viral infections presenting with respiratory symptoms, MIS-C manifests as systemic inflammation with potential organ failure (108). Its immune dysregulation may be exacerbated by SARS-CoV-2’s superantigen-like properties. These distinctions emphasize the need for comprehensive differential diagnosis in pediatric patients with systemic inflammation (98, 109, 110).

6 Future research directions and clinical applications

6.1 Identification of novel biomarkers

Novel biomarkers are critical for advancing MIS-C diagnosis and management. Recent studies highlight immunoglobulin G (IgG) glycosylation patterns—particularly afucosylated spike IgG—as promising biomarkers correlating with disease severity and hyperinflammatory responses in MIS-C patients. These glycan modifications may help track disease progression and therapeutic responses. Additional biomarkers involving cytokine/chemokine dysregulation (e.g., IL-6, CXCL9) and T-cell activation profiles are under investigation for early diagnosis and targeted therapy development (20, 106). Future research should prioritize validating large-scale validation of these biomarkers and assess their clinical utility.

6.2 Optimization of treatment strategies

Treatment optimization remains challenging due to MIS-C heterogeneity and variable treatment responses. Current immunomodulatory regimens (e.g., IVIG, corticosteroids) show inconsistent efficacy (111). Emerging strategies combine conventional therapies with novel agents like zonulin inhibitors to address intestinal barrier dysfunction and immune hyperactivation. Personalized approaches accounting for individual immune profiles and organ involvement may improve outcomes. Robust clinical trials evaluating combination therapies and biomarker-guided regimens are urgently needed to establish evidence-based guidelines.

6.3 Impact of vaccination on MIS-C incidence and severity

Vaccination significantly reduces MIS-C risk by modulating SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammatory responses. Multiple studies demonstrate 2-4-fold lower MIS-C incidence among vaccinated children, with attenuated severity in breakthrough cases (112–114). Proposed mechanisms include vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies limiting viral replication and memory B-cell responses dampening hyperinflammation. Longitudinal data confirm sustained protection against MIS-C post-vaccination, supporting its public health value (115). Ongoing surveillance is essential to evaluate vaccine efficacy against emerging variants and optimize pediatric vaccination strategies.

7 Conclusion

Research on MIS-C has elucidated its complex pathophysiological, focusing on immune dysregulation and viral triggers. As a significant COVID-19 complication, MIS-C presents distinctive challenges in pediatric healthcare, requiring comprehensive understanding of its diverse clinical manifestations and immunological responses. The integration of multidisciplinary findings reveals that effective management necessitates collaborative approaches spanning immunology, pediatrics, and infectious disease specialties.

MIS-C’s heterogeneous clinical presentation—ranging from gastrointestinal to cardiovascular involvement—demands broad diagnostic criteria, while its hyperinflammatory nature underscores the need for targeted immunomodulatory therapies. Current advances not only improve clinical practice but also guide future research directions. Ongoing investigations into immune dysregulation mechanisms remain crucial for developing effective preventive and therapeutic strategies. For instance, biomarker discovery could enable risk stratification and personalized treatment approaches.

Furthermore, insights from MIS-C management inform our understanding of other pediatric inflammatory conditions and enhance preparedness for future emerging pathogens. This collective knowledge strengthens pandemic response capabilities and ultimately contributes to improved global child health outcomes.

Author contributions

TX: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. XH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis. XX: Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JQ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. CW: Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YY: Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LK: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the fund from the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (202201020628).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CRP, reactive protein; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; KD, Kawasaki Disease; MAS, Macrophage activation syndrome; MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; PRRs, pattern recognition receptors; RBD, receptor-binding domain; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WHO, the World Health Organization (WHO); TLRs, Toll-like receptors; TSS, toxic shock syndrome; VIS, Vasoactive Inotropic Score.

References

1. Basu M and Das SK. Clinical characteristics of paediatric hyperinflammatory syndrome in the era of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Indian J Clin Biochem. (2021) 36:404–15. doi: 10.1007/s12291-021-00963-4

2. Bhat CS, Gupta L, Balasubramanian S, Singh S, and Ramanan AV. Hyperinflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19: need for awareness. Indian Pediatr. (2020) 57:929–35. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1997-1

3. Filippatos F, Tatsi EB, and Michos A. Immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome after COVID-19 in children: A review of the current evidence. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:5711. doi: 10.3390/ijms24065711

4. Panaro S and Cattalini M. The spectrum of manifestations of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV2) infection in children: what we can learn from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 8:747190. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.747190

5. Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, Martelli L, Ruggeri M, Ciuffreda M, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. (2020) 395:1771–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31103-x

6. Feldstein LR, Rose EB, Horwitz SM, Collins JP, Newhams MM, Son MBF, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. Children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:334–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680

7. Whittaker E, Bamford A, Kenny J, Kaforou M, Jones CE, Shah P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-coV-2. Jama. (2020) 324:259–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369

8. Eskandarian Boroujeni M, Sekrecka A, Antonczyk A, Hassani S, Sekrecki M, Nowicka H, et al. Dysregulated interferon response and immune hyperactivation in severe COVID-19: targeting STATs as a novel therapeutic strategy. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:888897. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.888897

9. Angurana SK, Kumar V, Nallasamy K, Kumar MR, Naganur S, Kumar M, et al. Clinico-laboratory profile, intensive care needs and short-term outcome of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): experience during first and second waves from north India. J Trop Pediatr. (2022) 68:fmac068. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmac068

10. Gruber CN, Patel RS, Trachtman R, Lepow L, Amanat F, Krammer F, et al. Mapping systemic inflammation and antibody responses in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Cell. (2020) 183:982–95.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.034

11. Vaňková L, Bufka J, and Křížková V. Pathophysiological and clinical point of view on Kawasaki disease and MIS-C. Pediatr Neonatol. (2023) 64:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2023.05.002

12. Sharma C, Ganigara M, Galeotti C, Burns J, Berganza FM, Hayes DA, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and Kawasaki disease: a critical comparison. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2021) 17:731–48. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00709-9

13. Piekarski F, Steinbicker AU, and Armann JP. The multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and its association to SARS-CoV-2. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2021) 34:521–9. doi: 10.1097/aco.0000000000001024

14. Jiang L, Tang K, Levin M, Irfan O, Morris SK, Wilson K, et al. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:e276–e88. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30651-4

15. Hoste L, Van Paemel R, and Haerynck F. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children related to COVID-19: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr. (2021) 180:2019–34. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-03993-5

16. Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, Gorelik M, Lapidus SK, Bassiri H, et al. American college of rheumatology clinical guidance for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-coV-2 and hyperinflammation in pediatric COVID-19: version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2022) 74:e1–e20. doi: 10.1002/art.42062

17. Patel JM. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. (2022) 22:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11882-022-01031-4

18. Gottlieb M, Bridwell R, Ravera J, and Long B. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. (2021) 49:148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.05.076

19. La Torre F, Taddio A, Conti C, and Cattalini M. Multi-inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in 2023: is it time to forget about it? Children (Basel). (2023) 10:980. doi: 10.3390/children10060980

20. Carter MJ, Fish M, Jennings A, Doores KJ, Wellman P, Seow J, et al. Peripheral immunophenotypes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1701–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1054-6

21. Rey-Jurado E, Espinosa Y, Astudillo C, Jimena Cortés L, Hormazabal J, Noguera LP, et al. Deep immunophenotyping reveals biomarkers of multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children in a Latin American cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2022) 150:1074–85.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.006

22. Raffeiner B, Rojatti M, Tröbinger C, Nailescu AM, and Pagani L. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome of adults (MIS-A) as delayed severe presentation of SARS-coV-2 infection: A description of two cases. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:6632. doi: 10.3390/jcm13226632

23. Saeed S, Cao J, Xu J, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Jiang L, et al. Case Report: A case of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in an 11-year-old female after COVID-19 inactivated vaccine. Front Pediatr. (2023) 11:1068301. doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1068301

24. Chien TC, Chien MM, Liu TL, Chang H, Tsai ML, Tseng SH, et al. Adrenal crisis mimicking COVID-19 encephalopathy in a teenager with craniopharyngioma. Children (Basel). (2022) 9:1238. doi: 10.3390/children9081238

25. García-Azorín D, Abildúa MJA, Aguirre MEE, Fernández SF, Moncó JCG, Guijarro-Castro C, et al. Neurological presentations of COVID-19: Findings from the Spanish Society of Neurology neuroCOVID-19 registry. J Neurol Sci. (2021) 423:117283. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117283

26. Sana A and Avneesh M. Identification of hematological and inflammatory parameters associated with disease severity in hospitalized patients of COVID-19. J Family Med Prim Care. (2022) 11:260–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_941_21

27. Sukrisman L and Sinto R. Coagulation profile and correlation between D-dimer, inflammatory markers, and COVID-19 severity in an Indonesian national referral hospital. J Int Med Res. (2021) 49:3000605211059939. doi: 10.1177/03000605211059939

28. Zhao Y, Yin L, Patel J, Tang L, and Huang Y. The inflammatory markers of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and adolescents associated with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:4358–69. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26951

29. Shabbir A, Khurshid H, and Khan IM. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates associated with COVID-19 in neonatal ICU of a tertiary care hospital. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. (2024) 34:727–31. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2024.06.727

30. Godfred-Cato S, Abrams JY, Balachandran N, Jaggi P, Jones K, Rostad CA, et al. Distinguishing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children from COVID-19, kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2022) 41:315–23. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000003449

31. Payne AB, Gilani Z, Godfred-Cato S, Belay ED, Feldstein LR, Patel MM, et al. Incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children among US persons infected with SARS-coV-2. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2116420. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16420

32. Santos-Rebouças CB, Piergiorge RM, Dos Santos Ferreira C, Seixas Zeitel R, Gerber AL, Rodrigues MCF, et al. Host genetic susceptibility underlying SARS-CoV-2-associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Brazilian Children. Mol Med. (2022) 28:153. doi: 10.1186/s10020-022-00583-5

33. Abrams JY, Godfred-Cato SE, Oster ME, Chow EJ, Koumans EH, Bryant B, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: A systematic review. J Pediatr. (2020) 226:45–54.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.003

34. Avcu G, Arslan SY, Soylu M, Bilen NM, Bal ZS, Cicek C, et al. Quantitative antibody levels against SARS-coV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Viral Immunol. (2022) 35:681–9. doi: 10.1089/vim.2022.0089

35. Kornitzer J, Johnson J, Yang M, Pecor KW, Cohen N, Jiang C, et al. A systematic review of characteristics associated with COVID-19 in children with typical presentation and with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8269. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168269

36. Messiah SE, Xie L, Mathew MS, Shaikh S, Veeraswamy A, Rabi A, et al. Comparison of long-term complications of COVID-19 illness among a diverse sample of children by MIS-C status. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:13382. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013382

37. Son MBF, Murray N, Friedman K, Young CC, Newhams MM, Feldstein LR, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children - initial therapy and outcomes. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102605

38. Visa-Reñé N, Rubio-Páez A, Mitjans-Rubies N, and Paredes-Carmona F. Comparison of plasma inflammatory biomarkers between MIS-C and potentially serious infections in pediatric patients. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). (2024) 20:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.reumae.2024.01.005

39. Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C, and Favaloro EJ. Diagnostic value of D-dimer in differentiating multisystem inflammatory syndrome in Children (MIS-C) from Kawasaki disease: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Diagnosis (Berl). (2024) 11:231–4. doi: 10.1515/dx-2024-0013

40. Yan Y, Barbati ME, Avgerinos ED, Doganci S, Lichtenberg M, and Jalaie H. Elevation of cardiac enzymes and B-type natriuretic peptides following venous recanalization and stenting in chronic venous obstruction. Phlebology. (2024) 39:619–28. doi: 10.1177/02683555241261321

41. Vukomanovic V, Krasic S, Prijic S, Petrovic G, Ninic S, Popovic S, et al. Myocardial damage in multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 in children and adolescents. J Res Med Sci. (2021) 26:113. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_1195_20

42. Chen B, Sun L, and Zhang X. Integration of microbiome and epigenome to decipher the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. (2017) 83:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.03.009

43. Shan J, Jin H, and Xu Y. T cell metabolism: A new perspective on th17/treg cell imbalance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1027. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01027

44. Goetzke CC, Massoud M, Frischbutter S, Guerra GM, Ferreira-Gomes M, Heinrich F, et al. TGFβ links EBV to multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nature. (2025) 640:762–71. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-08697-6

45. Cheng MH, Zhang S, Porritt RA, Noval Rivas M, Paschold L, Willscher E, et al. Superantigenic character of an insert unique to SARS-CoV-2 spike supported by skewed TCR repertoire in patients with hyperinflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2020) 117:25254–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010722117

46. Porritt RA, Binek A, Paschold L, Rivas MN, McArdle A, Yonker LM, et al. The autoimmune signature of hyperinflammatory multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J Clin Invest. (2021) 131:e151520. doi: 10.1172/jci151520

47. Bodansky A, Mettelman RC, Sabatino JJ Jr., Vazquez SE, Chou J, Novak T, et al. Molecular mimicry in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nature. (2024) 632:622–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07722-4

48. Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, and Pennington DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1843:2563–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014

49. Dinarello CA. Historical insights into cytokines. Eur J Immunol. (2007) 37 Suppl 1:S34–45. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737772

50. Dzhambazov B. Special issue: autoimmune diseases: A swing dance of immune cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:9365. doi: 10.3390/ijms26199365

51. Feldmann M, Maini RN, and Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. (2003) 9:1245–50. doi: 10.1038/nm939

52. McInnes IB and Schett G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. (2017) 389:2328–37. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31472-1

53. Jain A, Bishnoi M, Prajapati SK, Acharya S, Kapre S, Singhvi G, et al. Targeting rheumatoid arthritis: a molecular perspective on biologic therapies and clinical progress. J Biol Eng. (2025) 19:67. doi: 10.1186/s13036-025-00534-8

54. Najm A, Ferguson LD, and McInnes IB. Cytokine pathways driving diverse tissue pathologies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2025). doi: 10.1002/art.43376

55. Liu Y, Wang XQ, Lu JH, Huang HW, Qiu YH, and Peng YP. Treg cells mitigate inflammatory responses and symptoms via β2-AR/β-Arr2/ERK signaling in an experimental rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. (2025) 27:194. doi: 10.1186/s13075-025-03659-9

56. Li H, Wu QY, Teng XH, Li ZP, Zhu MT, Gu CJ, et al. The pathogenesis and regulatory role of HIF-1 in rheumatoid arthritis. Cent Eur J Immunol. (2023) 48:338–45. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2023.134217

57. Livshits G and Kalinkovich A. Hierarchical, imbalanced pro-inflammatory cytokine networks govern the pathogenesis of chronic arthropathies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. (2018) 26:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.10.013

58. Jacobelli J, Buser AE, Heiden DL, and Friedman RS. Autoimmunity in motion: Mechanisms of immune regulation and destruction revealed by in vivo imaging. Immunol Rev. (2022) 306:181–99. doi: 10.1111/imr.13043

59. Zhao J, Lu Q, Liu Y, Shi Z, Hu L, Zeng Z, et al. Th17 cells in inflammatory bowel disease: cytokines, plasticity, and therapies. J Immunol Res. (2021) 2021:8816041. doi: 10.1155/2021/8816041

60. Darouni L, Tavassoli Razavi F, Yazdanpanah E, Orooji N, Shadab A, Emami A, et al. Interleukin 15 and autoimmune disorders: pathophysiology, therapeutic potential, and clinical implications. Inflammation Res. (2025) 74:141. doi: 10.1007/s00011-025-02084-7

61. Song Y, Li J, and Wu Y. Evolving understanding of autoimmune mechanisms and new therapeutic strategies of autoimmune disorders. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2024) 9:263. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01952-8

62. Zhou J, Yang D, Han C, Dong H, Wang S, Li X, et al. Inhibition of LARP4-mediated quiescence exit of naive CD4(+) T cells ameliorates autoimmune and allergic diseases. Nat BioMed Eng. (2025). doi: 10.1038/s41551-025-01514-5

63. Du J, Chen H, You J, Hu W, Liu J, Lu Q, et al. Proximity between LAG-3 and the T cell receptor guides suppression of T cell activation and autoimmunity. Cell. (2025) 188:4025–42.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.06.004

64. Yan J and Mamula MJ. B and T cell tolerance and autoimmunity in autoantibody transgenic mice. Int Immunol. (2002) 14:963–71. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf064

65. Jung S, Schickel JN, Kern A, Knapp AM, Eftekhari P, Da Silva S, et al. Chronic bacterial infection activates autoreactive B cells and induces isotype switching and autoantigen-driven mutations. Eur J Immunol. (2016) 46:131–46. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545810

66. McQueen F. A B cell explanation for autoimmune disease: the forbidden clone returns. Postgrad Med J. (2012) 88:226–33. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130364

67. Hou Y, Sun L, LaFleur MW, Huang L, Lambden C, Thakore PI, et al. Neuropeptide signalling orchestrates T cell differentiation. Nature. (2024) 635:444–52. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08049-w

68. An Haack I, Derkow K, Riehn M, Rentinck MN, Kühl AA, Lehnardt S, et al. The role of regulatory CD4 T cells in maintaining tolerance in a mouse model of autoimmune hepatitis. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0143715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143715

69. Gouirand V, Habrylo I, and Rosenblum MD. Regulatory T cells and inflammatory mediators in autoimmune disease. J Invest Dermatol. (2022) 142:774–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2021.05.010

70. Hassan M, Elzallat M, Mohammed DM, Balata M, and El-Maadawy WH. Exploiting regulatory T cells (Tregs): Cutting-edge therapy for autoimmune diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. (2025) 155:114624. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114624

71. Cheru NT, Osayame Y, and Sumida TS. Breaking tolerance: an update of Treg dysfunction in autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. (2025) 46:611–3. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2025.06.007

72. Peng YQ, Wang L, Tan AL, Wang SJ, Zou W, Li X, et al. PMEPA1-mediated treg cell impairment promotes endometrial stromal invasion via excessive PI3K/AKT signaling in endometriosis. Curr Med Sci. (2025) 45:1231–43. doi: 10.1007/s11596-025-00125-0

73. Balkhi MY. Mechanistic understanding of innate and adaptive immune responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mol Immunol. (2021) 135:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2021.04.021

74. Sievers BL, Cheng MTK, Csiba K, Meng B, and Gupta RK. SARS-CoV-2 and innate immunity: the good, the bad, and the “goldilocks. Cell Mol Immunol. (2024) 21:171–83. doi: 10.1038/s41423-023-01104-y

75. Shen J, Fan J, Zhao Y, Jiang D, Niu Z, Zhang Z, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and predisposing factors. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1159326. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1159326

76. Sariol A and Perlman S. Lessons for COVID-19 immunity from other coronavirus infections. Immunity. (2020) 53:248–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.005

77. Thorne LG, Reuschl AK, Zuliani-Alvarez L, Whelan MVX, Turner J, Noursadeghi M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 sensing by RIG-I and MDA5 links epithelial infection to macrophage inflammation. EMBO J. (2021) 40:e107826. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021107826

78. Lei X, Dong X, Ma R, Wang W, Xiao X, Tian Z, et al. Activation and evasion of type I interferon responses by SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:3810. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17665-9

79. Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, Uhl S, Hoagland D, Møller R, et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-coV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. (2020) 181:1036–45.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026

80. Mathew D, Giles JR, Baxter AE, Oldridge DA, Greenplate AR, Wu JE, et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science. (2020) 369:eabc8511. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8511

81. Li T, Wang D, Wei H, and Xu X. Cytokine storm and translating IL-6 biology into effective treatments for COVID-19. Front Med. (2023) 17:1080–95. doi: 10.1007/s11684-023-1044-4

82. Tian J, Shang B, Zhang J, Guo Y, Li M, Hu Y, et al. T cell immune evasion by SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 escapees targeting two cytotoxic T cell epitope hotspots. Nat Immunol. (2025) 26:265–78. doi: 10.1038/s41590-024-02051-0

83. Wang Y, Bai C, Hou K, Zhang Z, Guo M, Wang X, et al. Engineered dual-function antibody-like proteins to combat SARS-coV-2-induced immune dysregulation and inflammation. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2025) 12:e04690. doi: 10.1002/advs.202504690

84. Versace V, Ortelli P, Dezi S, Ferrazzoli D, Alibardi A, Bonini I, et al. Co-ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide/luteolin normalizes GABA-ergic activity and cortical plasticity in long COVID-19 syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. (2023) 145:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2022.10.017

85. Öztürk R, Taşova Y, and Ayaz A. COVID-19: pathogenesis, genetic polymorphism, clinical features and laboratory findings. Turk J Med Sci. (2020) 50:638–57. doi: 10.3906/sag-2005-287

86. Giovanetti M, Branda F, Cella E, Scarpa F, Bazzani L, Ciccozzi A, et al. Epidemic history and evolution of an emerging threat of international concern, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J Med Virol. (2023) 95:e29012. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29012

87. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, and Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. (2020) 395:1607–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31094-1

88. Dufort EM, Koumans EH, Chow EJ, Rosenthal EM, Muse A, Rowlands J, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in new york state. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:347–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756

89. López-Macías C, López-Medina E, Alves MB, Matos ADR, Hernández-Villena JV, Aponte-Torres Z, et al. Clinical characteristics, SARS-CoV-2 variants, and outcomes of adults hospitalized due to COVID-19 in Latin American countries. Clinics (Sao Paulo). (2025) 80:100648. doi: 10.1016/j.clinsp.2025.100648

90. Chen Y, Liu Q, Zhou L, Zhou Y, Yan H, and Lan K. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants: Why, how, and what’s next? Cell Insight. (2022) 1:100029. doi: 10.1016/j.cellin.2022.100029

91. Mohsin M and Mahmud S. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern: A review on its transmissibility, immune evasion, reinfection, and severity. Med (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e29165. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000029165

92. Arabi M, Al-Najjar Y, Sharma O, Kamal I, Javed A, Gohil HS, et al. Role of previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 in protecting against omicron reinfections and severe complications of COVID-19 compared to pre-omicron variants: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. (2023) 23:432. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08328-3

93. Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Hilton SK, Ellis D, Crawford KHD, Dingens AS, et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-coV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell. (2020) 182:1295–310.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.012

94. Tian F, Tong B, Sun L, Shi S, Zheng B, Wang Z, et al. N501Y mutation of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 strengthens its binding to receptor ACE2. Elife. (2021) 10:e69091. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69091

95. Reynolds CJ, Swadling L, Gibbons JM, Pade C, Jensen MP, Diniz MO, et al. Discordant neutralizing antibody and T cell responses in asymptomatic and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol. (2020) 5:eabf3698. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abf3698

96. Anderson EM, Goodwin EC, Verma A, Arevalo CP, Bolton MJ, Weirick ME, et al. Seasonal human coronavirus antibodies are boosted upon SARS-CoV-2 infection but not associated with protection. Cell. (2021) 184:1858–64.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.010

97. SARS-coV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant - United States, december 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1731–4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

98. Dhaliwal M, Tyagi R, Malhotra P, Barman P, Loganathan SK, Sharma J, et al. Mechanisms of immune dysregulation in COVID-19 are different from SARS and MERS: A perspective in context of kawasaki disease and MIS-C. Front Pediatr. (2022) 10:790273. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.790273

99. Tian K, Dangarh P, Zhang H, Hines CL, Bush A, Pybus HJ, et al. Role of epithelial barrier function in inducing type 2 immunity following early-life viral infection. Clin Exp Allergy. (2024) 54:109–19. doi: 10.1111/cea.14425

100. Mistry LN, Agarwal S, Jaiswal H, Kondkari S, Mulla SA, and Bhandarkar SD. Human metapneumovirus: emergence, impact, and public health significance. Cureus. (2025) 17:e80964. doi: 10.7759/cureus.80964

101. Petat H, Gajdos V, Angoulvant F, Vidalain PO, Corbet S, Marguet C, et al. High frequency of viral co-detections in acute bronchiolitis. Viruses. (2021) 13:990. doi: 10.3390/v13060990

102. Papatriantafyllou M. A role for TGFβ and EBV in MIS-C pathogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2025) 21:255. doi: 10.1038/s41584-025-01244-7

103. Liu M, Brodeur KE, Bledsoe JR, Harris CN, Joerger J, Weng R, et al. Features of hyperinflammation link the biology of Epstein-Barr virus infection and cytokine storm syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2025) 155:1346–56.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.11.029

104. Gençeli M, Üstüntaş T, Metin Akcan Ö, Saylik S, Ercan F, Pekcan S, et al. A new scoring in differential diagnosis: multisystem inflammatory syndrome or adenovirus infection? Turk J Med Sci. (2024) 54:1237–43. doi: 10.55730/1300-0144.5905

105. Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, Newhams M, Rose EB, Dapul H, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) compared with severe acute COVID-19. Jama. (2021) 325:1074–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2091

106. Caldarale F, Giacomelli M, Garrafa E, Tamassia N, Morreale A, Poli P, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells depletion and elevation of IFN-γ Dependent chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:654587. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.654587

107. Biesbroek G, Kapitein B, Kuipers IM, Gruppen MP, van Stijn D, Peros TE, et al. Inflammatory responses in SARS-CoV-2 associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome and Kawasaki Disease in children: An observational study. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0266336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266336

108. Truong DT, Trachtenberg FL, Hu C, Pearson GD, Friedman K, Sabati AA, et al. Six-month outcomes in the long-term outcomes after the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children study. JAMA Pediatr. (2025) 179:293–301. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.5466

109. Guo J and Wang L. The complex landscape of immune dysregulation in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Life Med. (2024) 3:lnae034. doi: 10.1093/lifemedi/lnae034

110. Nakra NA, Blumberg DA, Herrera-Guerra A, and Lakshminrusimha S. Multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) following SARS-coV-2 infection: review of clinical presentation, hypothetical pathogenesis, and proposed management. Children (Basel). (2020) 7:69. doi: 10.3390/children7070069

111. Melgar M, Seaby EG, McArdle AJ, Young CC, Campbell AP, Murray NL, et al. Treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: understanding differences in results of comparative effectiveness studies. ACR Open Rheumatol. (2022) 4:804–10. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11478

112. Schwartz N, Ratzon R, Hazan I, Zimmerman DR, Singer SR, Wasser J, et al. Multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children and the BNT162b2 vaccine: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. (2024) 183:3319–26. doi: 10.1007/s00431-024-05586-4

113. Le Marchand C, Singson JRC, Clark A, Shah D, Wong M, Chavez S, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) cases by vaccination status in California. Vaccine. (2025) 43:126499. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126499

114. Piechotta V, Siemens W, Thielemann I, Toews M, Koch J, Vygen-Bonnet S, et al. Safety and effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19 in children aged 5–11 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2023) 7:379–91. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(23)00078-0

Keywords: children, MIS-C, immune dysregulation, viral triggers, SARS-CoV-2

Citation: Xu T, Zhang J, Hou X, Xie X, Qi J, Wang C, Yan Y, Kuang L and Zhu B (2025) MIS-C pathogenesis: immune dysregulation & viral triggers. Front. Immunol. 16:1624963. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1624963

Received: 08 May 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 22 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Pengfei Wang, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Zhaowei Xu, Fujian Medical University, ChinaRahul Tyagi, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United States

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Zhang, Hou, Xie, Qi, Wang, Yan, Kuang and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bing Zhu, emh1YmluZzAzMjdAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Tiantian Xu1†

Tiantian Xu1† Junye Qi

Junye Qi Bing Zhu

Bing Zhu