Abstract

The interaction between gut microbiota metabolites and the host immune system plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and in the development of inflammatory bowel disease and other enteric conditions. This article presents a systematic review of the sources and functions of short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan metabolites, bile acids, and other microbial metabolites, focusing on how these metabolites regulate the function of immune cells, such as T cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, as well as key inflammatory signaling pathways, including the NF-κB, NLRP3 inflammasome, and JAK–STAT pathways, thereby influencing intestinal barrier integrity. Also explored are potential therapeutic strategies based on microbial metabolites, including the application status and prospects of probiotic and prebiotic interventions, the direct administration of metabolites, and fecal microbiota transplantation. Although current research faces challenges such as unclear mechanisms, significant differences among individuals, and barriers to clinical translation, the development of multiomics technologies and precision medicine holds promise for providing more effective and personalized treatment strategies targeting gut microbiota metabolites for patients with enteritis.

1 Introduction

The composition and function of the gut microbiota interact intricately with the host immune system, a relationship that is vital for maintaining intestinal health. The gut microbiota not only participates in host nutritional metabolism but also regulates immune responses through its metabolites, thus playing a significant role in the onset and progression of enteritis (1). In recent years, research on the relationship between the gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has gradually increased, and findings have confirmed that gut dysbiosis is closely related to the pathogenesis of IBD (2, 3). Existing research indicates that an imbalance in gut microbial diversity, along with an overgrowth of specific pathogenic bacteria, can compromise intestinal barrier integrity, leading to chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation (4). As research has progressed, there has been a better understanding that gut dysbiosis not only causes local inflammation within the intestine but also may lead to systemic diseases by affecting the systemic immune system. For example, IBD patients often exhibit the overgrowth of certain specific microbes in their intestines. These microbes exacerbate inflammatory responses by producing proinflammatory metabolites and may cause extraintestinal immune dysregulation (4, 5). Focusing on the immunoregulatory mechanisms of these metabolites is pivotal. It clarifies the causal link between microbial dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation and pinpoints key molecular targets for novel therapies designed to reinstate immune homeostasis.

Research has shown that gut microbiota metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and tryptophan metabolites, also play important roles in regulating immune responses and maintaining intestinal barrier integrity. For instance, SCFAs play key roles in regulating the function of intestinal epithelial cells and promoting the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Tregs), thereby suppressing inflammatory responses and maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis (6, 7). Tryptophan metabolites, such as indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), have been shown to enhance intestinal barrier function in inflammatory states and improve clinical outcomes (8). Therefore, understanding how the gut microbiota and its metabolites affect host immune responses is crucial for developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the gut microbiota.

In recent years, treatment strategies based on gut microbiota products have attracted increasing attention. For example, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been used as a potential therapeutic method to alleviate IBD symptoms by restoring a healthy gut microbiota composition (9). Additionally, the use of probiotics and prebiotics has been shown to positively affect the gut microbiota, improving intestinal health and reducing inflammation levels (10).

In summary, the gut microbiota and its metabolites play key roles in the immunoregulation of enteritis. A deeper understanding of their mechanisms will provide new ideas and strategies for treating IBD and related diseases. These studies will both enhance our understanding of the interaction between the gut microbiota and host immunity and open new directions for future clinical treatments.

2 Gut microbiota and enteritis: an overview

A substantial body of evidence links dysbiosis of the gut microbiota to the pathogenesis of various forms of enteritis, including IBD, colitis, and infectious enteritis (11, 12). In IBD patients, a consistent reduction in microbial diversity and a shift in community structure, often characterized by a depletion of beneficial bacteria (e.g., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) and an expansion of pro-inflammatory species (e.g., adherent-invasive Escherichia coli), are frequently observed (13). This imbalance disrupts host-microbe symbiosis, leading to compromised epithelial barrier function, aberrant activation of mucosal immune responses, and sustained inflammation (4, 5). The following sections will detail how metabolites derived from this dysbiotic microbiota serve as key mediators in the immunoregulation of enteritis.

3 Types and sources of gut microbiota products

3.1 Short-chain fatty acids

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are important metabolites produced by the fermentation of dietary fiber by the gut microbiota, with bacteria such as Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes playing key roles in this process (14). The main types of SCFAs include acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs not only constitute the primary energy source for intestinal epithelial cells but also play important roles in maintaining intestinal barrier function and regulating immune responses and metabolism (15–17). Specifically, butyrate is considered among the most important SCFAs because it promotes the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal epithelial cells and has anti-inflammatory effects (18, 19). Importantly, SCFAs can regulate host energy metabolism and immune function by activating G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which play significant roles in various physiological and pathological processes closely related to host health (20–22).

3.2 Tryptophan metabolites

Tryptophan is an important essential amino acid, and its metabolites play a crucial role in the interaction between the gut microbiota and the host. Tryptophan is primarily derived from microbiota such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium; these microbes metabolize tryptophan to generate various bioactive metabolites, such as indole, indolepropionic acid, and kynurenine (23). These metabolites not only participate in regulating intestinal immune function (24) but also affect nervous system health (25), tumor development (26), and metabolic syndrome outcomes (27) and are closely related to mental health in some cases (28). One important metabolite, indole and its derivatives, can activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), exerting anti-inflammatory effects in regulating intestinal immune responses and barrier function (29, 30), further highlighting its importance in host health.

3.3 Bile acids and their derivatives

Bile acids are key metabolites synthesized by the liver and are transformed in the intestine by gut microbes. Primary bile acids synthesized in the liver are converted into secondary bile acids, such as deoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid, by intestinal microbial metabolism (31). These bile acids not only participate in fat digestion and absorption but also play important roles in regulating tumorigenesis, immunity, and microbial community composition (32–34). Bile acids can activate various nuclear receptors, such as the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5), to regulate signaling molecules and the metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids, and energy, and play significant roles in modulating liver and intestinal metabolic functions (35, 36). Therefore, metabolic dysregulation may lead to various diseases, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and enteritis (37–39).

3.4 Other types of metabolites

In addition to short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan metabolites, and bile acids, the gut microbiota also produces various other metabolites that play important roles in intestinal health. Studies have shown that the gut microbiota can produce vitamins, antimicrobial peptides, and other bioactive compounds. These substances can not only enhance intestinal barrier function but also regulate immune responses and metabolic processes (39, 40). For example, the microbial decomposition product spermidine has anti-inflammatory effects and regulates physiological activities such as cell growth and proliferation (41, 42). Niechcial (43) et al. reported that spermidine has a protective effect on colitis and restores a healthy gut microbiota. Mechanistically, spermidine primarily maintains epithelial barrier integrity in a PTPN2-dependent manner and prevents macrophage polarization towards a proinflammatory phenotype to reduce intestinal inflammation. In addition to obtaining B vitamins from the diet, the gut microbiota is now considered a potential source of B vitamins (44). Studies have shown that B vitamins can, in turn, act as nutrients for the gut microbiota, regulators of immune cell activity, and modulators of colitis (45). Recently, Dalayeli (46) et al. validated the anti-inflammatory and antiulcer properties of B vitamins in animal models. They reported that B vitamins have a protective effect on mouse enteritis regardless of treatment dose and duration. These studies reveal the diversity and complexity of gut microbiota metabolites, emphasizing their importance in maintaining intestinal and systemic health.

4 Immunoregulatory mechanisms of gut microbiota metabolites

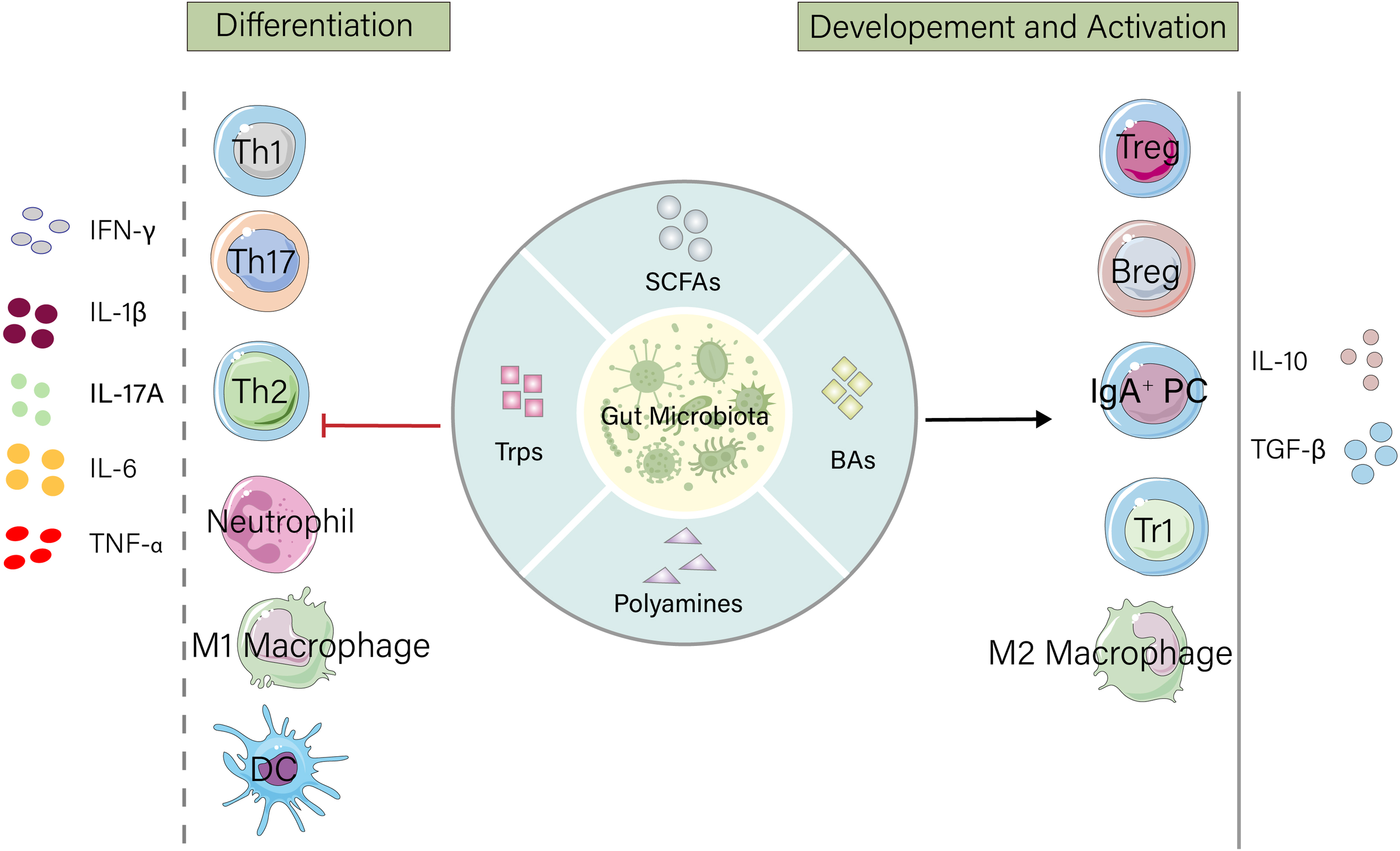

Gut microbiota metabolites exert broad and precise regulatory effects on the immune system. These metabolites not only directly influence the differentiation, activation, and function of various immune cells but also maintain intestinal immune homeostasis through mechanisms such as cellular metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic modifications, and signaling pathway activation. The following sections elaborate on the specific regulatory effects of gut microbiota metabolites on T cells, B cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Gut microbiota metabolites maintain intestinal homeostasis by regulating the host immune system. Microbial products such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), tryptophan, bile acids, and polyamines promote the development and activation of immunosuppressive cells, increase the release of anti-inflammatory factors, and suppress the differentiation of inflammatory cells as well as the secretion of proinflammatory factors. IFN, Interferon; IL, Interleukin; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; Th, T helper cell; DC, Dendritic cell; Treg, Regulatory T cell; Breg, Regulatory B cell; IgA+PC, IgA-secreting plasma cell; Tr1, Type 1 regulatory T cell.

4.1 Modulation of adaptive immunity: T cells and B cells

T Cell Subset Differentiation: The gut microbiota precisely regulates the differentiation, function, and homeostasis of T cells through a network of metabolites, serving as a core mechanism for maintaining intestinal immune balance. SCFAs, produced by the symbiotic bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, act as key signaling molecules. On the one hand, SCFAs perform epigenetic regulation by inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) (16); on the other hand, they activate GPCRs (GPR43, GPR41, and GPR109a) (47). Together, these actions strongly promote the generation and activity of immunosuppressive Tregs while effectively inhibiting the overactivation of proinflammatory Th17 cells (47, 48) and regulating the metabolism and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells (49). Metabolites derived from the microbial metabolism of dietary tryptophan, such as indole derivatives and kynurenine, primarily activate the AhR signaling pathway, further inducing Treg differentiation, suppressing Th1/Th17 responses, and helping maintain intestinal epithelial barrier integrity and regulate T cell migration (50–52). Secondary bile acids, which are converted from primary bile acids, act as important signaling molecules by binding FXR or TGR5, also tending to inhibit the differentiation of proinflammatory Th17 cells, promote Treg generation (53, 54), and regulate T cell mitochondrial function and energy metabolism (55, 56). Furthermore, peptidoglycan fragments derived from bacterial cell wall degradation, particularly muramyl dipeptide (MDP), act as important pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) recognized by the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) receptor in host cells, and the activation of NOD2 signaling can inhibit the differentiation, expansion, and immunosuppressive function of Tregs (57). These diverse microbiota products (including substances such as polyamines and B vitamins that influence T cell metabolic reprogramming) work synergistically through three core pathways—epigenetic modification, specific receptor signal transduction, and cellular metabolic reprogramming—to finely maintain the dynamic balance between Tregs and effector T cells (such as Th1 and Th17 cells), thereby promoting immune tolerance and suppressing excessive inflammatory responses both locally and systemically (23, 58, 59). The disruption of this precise regulatory network dominated by microbiota products is closely related to the pathogenesis and development of various pathological states, such as IBD (60), autoimmune diseases (61), and cancer (62).

B Cell Development and Function: Gut microbiota metabolites precisely regulate the development, activation, differentiation, and function of B cells through multilayered direct and indirect mechanisms and play a central role in maintaining intestinal mucosal immune homeostasis. Like in T cells, SCFAs can also drive the differentiation of intestinal IgA+ plasma cells by activating GPCRs on the B cell surface and through epigenetic regulation via the inhibition of HDAC activity (63, 64). Moreover, SCFAs indirectly affect B cell affinity maturation and the germinal center (GC) responses by regulating the function of follicular helper T (Tfh) cells (65). Tryptophan metabolites (such as 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid) enhance the suppressive function of Bregs and inhibit GC B cell and plasma cell differentiation by activating AhR in B cells (66). Additionally, polyamines (such as spermidine) regulate B cell metabolic adaptability and survival by inhibiting the mTORC1 pathway and enhancing autophagy (67). Furthermore, the gut microbiota can interact with vitamin A to maintain intestinal immune stability. With the assistance of the gut microbiota, the vitamin A derivative retinoic acid binds to the nuclear receptor RARα in B cells, induces the expression of the gut-homing receptor (α4β7 integrin), directs the recruitment of B cells to the intestinal mucosa, and promotes IgA secretion by B cells. IgA, in turn, can coordinately balance the composition of the gut microbiota (68). Overall, microbiota products achieve core regulation through direct receptor signaling (GPCRs/TLRs/AhR/RAR), epigenetic reprogramming, and indirect Tfh/Breg interaction networks, working synergistically to 1) induce immune tolerance and suppress inflammation via Bregs and 2) directionally recruit B cells to the intestine and optimize their response efficacy.

4.2 Influence on innate immunity: neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells

Neutrophil Recruitment and Activation: Microbiota metabolites play a protective role in mucosal defense and immune homeostasis by regulating neutrophil recruitment, activation, bactericidal function, and inflammation resolution pathways. SCFAs induce neutrophil migration to inflammation sites and increase their phagocytic capacity by activating the cell surface GPR43 receptor (69), significantly reducing the release of neutrophil chemokines (such as IL-8/CXCL1) and proinflammatory cytokines (such as IFN-γ and IL-1β) (70) while decreasing the release of neutrophil reactive oxygen species (ROS) to mitigate tissue damage (71), thereby limiting the inflammatory response capacity of neutrophils. Tryptophan metabolites activate AhR, inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β maturation (72, 73) while also inhibiting neutrophil myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (74), accelerating the resolution of neutrophil-mediated inflammation and reducing bystander tissue damage. Specific microbiota metabolites, such as succinate, which is overproduced by pathogenic Fusobacterium nucleatum, can promote neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. NETs further increase the proportion of Th1/Th17 cells among CD4+ T cells and the expression of the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ/IL-17A, thereby amplifying autoimmune inflammation (75, 76). In the context of cancer, bile acids induce neutrophil recruitment and maintain their immature phenotype via the GPBAR1-CXCL10 axis, creating an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (76). In summary, microbiota products achieve a bidirectional fine balance in regulating neutrophils: on the one hand, they can enhance phagocytic function to strengthen defense against acute infections; on the other hand, they can suppress excessive inflammatory factor release and promote inflammation resolution and tissue repair. An imbalance in this regulatory network can lead to abnormal neutrophil activation or functional defects, which are deeply involved in the pathological processes of diseases such as IBD, sepsis, and autoimmune diseases.

Macrophage Polarization and Function: Macrophages play important roles in immune responses, and their function is also regulated by gut microbiota products. Gut microbiota products continuously and precisely regulate the development, polarization, functional status, and tissue homeostasis maintenance of intestinal macrophages. These microbial small molecules act as key commensal signals on macrophages in different intestinal regions (such as the lamina propria, Peyer’s patches, and crypts) through various mechanisms: on one hand, they specifically bind to macrophage GPRs [e.g., GPR43 binds SCFAs (77), and TGR5 binds secondary bile acids (78)] or intracellular receptors [e.g., AhR binds tryptophan metabolites (79), and NOD2 recognizes muramyl dipeptide (80)], triggering downstream complex signaling networks [e.g., inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and NF-κB proinflammatory pathways (81) and inducing cAMP/PKA signaling (82)] and profoundly affecting epigenetic modifications [e.g., among SCFAs, butyrate potently inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), increases histone acetylation levels, and opens chromatin for anti-inflammatory genes (83)]; on the other hand, through this multireceptor, multipathway integration, they drive macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory, reparative, and tolerant phenotype (M2-like), manifested as a significantly enhanced phagocytic clearance capacity (efficiently clearing apoptotic cells and bacterial debris), an increase in the secretion of key anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-10, TGF-β), and the suppression of proinflammatory mediators like reactive oxygen species, while strongly inhibiting the excessive activation of macrophages towards a proinflammatory state (M1-like) and reducing the release of proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-6) (84, 85). Furthermore, specific microbiota products (like butyrate) are crucial for maintaining the local self-renewal, survival, and homeostatic pool of embryo-derived macrophages within the intestinal lamina propria (83, 86), influence the differentiation of bone marrow-derived monocytes into macrophages (86), “train” macrophages to establish immune tolerance to commensal bacteria (avoiding unnecessary inflammatory responses) while retaining vigilance against pathogens (6, 87), and strengthen intestinal barrier integrity by promoting epithelial tight junction protein expression and goblet cell mucus secretion (86, 88). This multifaceted and dynamically balanced regulatory network dominated by microbiota metabolites is the cornerstone of intestinal immune homeostasis, effectively coordinating the host defence, damage repair, and harmonious coexistence with commensal bacteria.

Dendritic Cell Maturation and T Cell Priming: Dendritic cells (DCs) are important bridges connecting innate and adaptive immunity, and their function is also regulated by gut microbiota products. Gut microbiota metabolites are core environmental signals that shape the phenotype, function, and immune response of intestinal DCs; they regulate DC maturation, migration, cytokine secretion profiles, antigen presentation efficiency, and the ability to induce T cell differentiation through various molecular mechanisms, thus playing a pivotal role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis and immune tolerance. These microbe-derived molecules (mainly including SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites, secondary bile acids, etc.) are recognized by DC subsets in different intestinal regions (such as CD103+CD11b+, CD103+CD11b-, CD11b+CD103-, and plasmacytoid DCs) by binding their surface or intracellular specific receptors [GPR43 binds SCFAs (88), AhR binds tryptophan metabolites (89), and FXR/TGR5 binds bile acids (90)], triggering downstream key signaling pathways [e.g., inhibiting NF-κB proinflammatory signaling via TGR5-cAMP-PKA (91)] and influencing epigenetic modifications [(e.g., butyrate inhibiting HDAC activity (92)]. Under this influence, microbiota products strongly drive DCs to present a “semimature” or “regulatory” phenotype, characterized by the moderate upregulation of the expression of costimulatory molecules (such as CD80, CD86, and CD40) and major histocompatibility complex class II molecules (MHC-II) to maintain necessary antigen presentation capacity (93), while selectively enhancing the secretion of anti-inflammatory/regulatory cytokines (such as IL-10 and TGF-β) and immunoregulatory mediators (e.g., retinoic acid metabolizing enzymes, e.g., RALDHs, catalyzing retinoic acid production and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activating IDO1) (59, 94). This unique cytokine and mediator environment prompts DCs to preferentially induce the differentiation of naïve T cells into Foxp3+ Tregs and IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) rather than proinflammatory Th1, Th2, or Th17 cells, thereby actively establishing and maintaining immune tolerance to food antigens and commensal bacteria (95).

5 Regulation of inflammatory signaling pathways by gut microbiota products

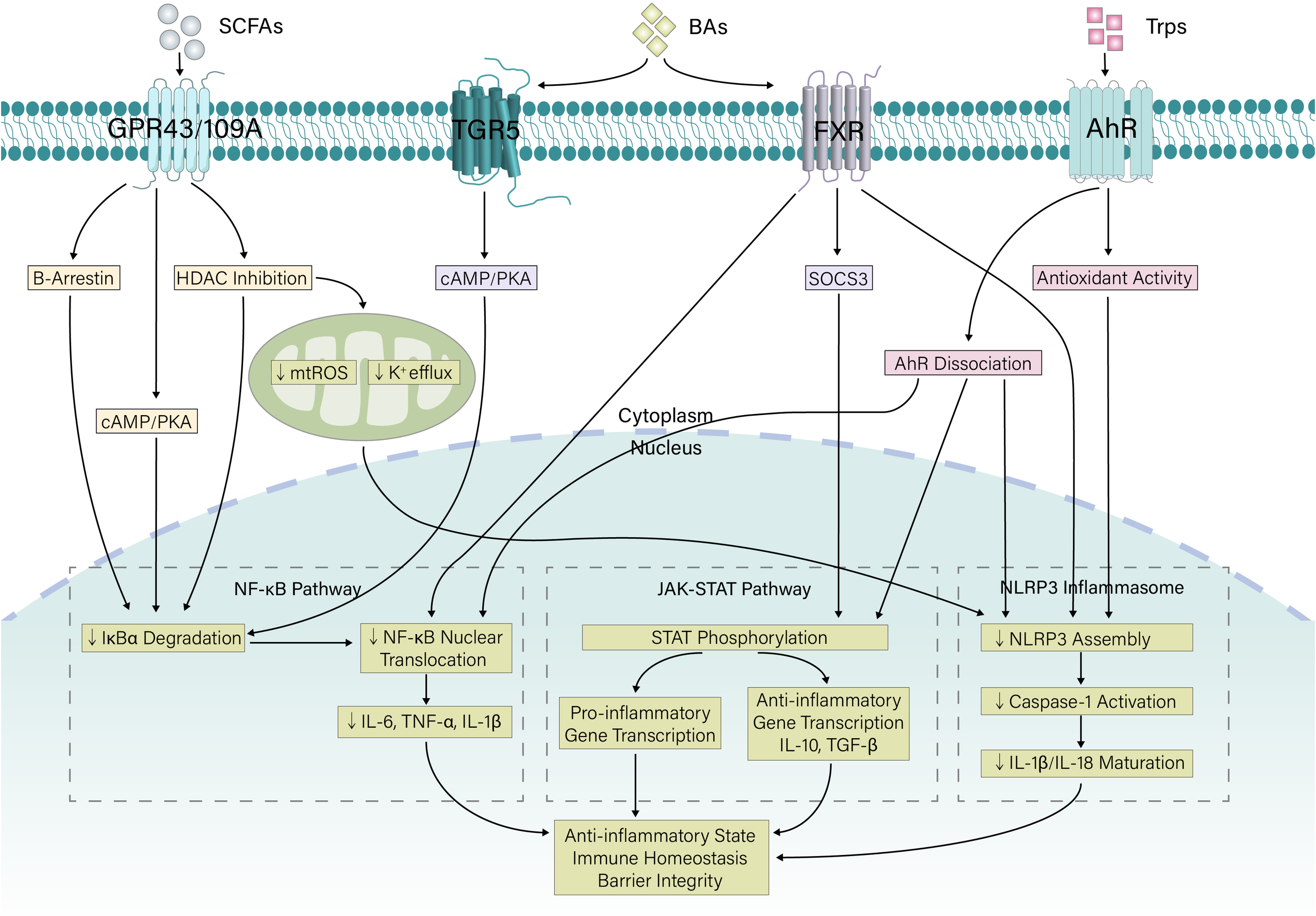

In addition to directly regulating immune cells, gut microbiota metabolites also serve as key modulators of intracellular inflammatory signaling pathways. By activating or inhibiting specific receptors and kinases, gut microbiota metabolites precisely regulate the activity of downstream transcription factors and the expression of inflammation-related genes, playing a decisive role in maintaining intestinal immune balance. The following sections elaborate on the regulatory effects of major metabolites on critical signaling pathways, including the NF-κB, NLRP3 inflammasome, and JAK–STAT pathways (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Coordinated regulation of inflammatory signaling by microbial metabolites. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites (SCFAs, bile acids, and tryptophan metabolites) signal through specific cellular receptors to suppress proinflammatory pathways. SCFAs act via GPCRs (GPR43/109A) and HDAC inhibition to stabilize IκBα and improve mitochondrial function. Bile acids signal through TGR5 and FXR to inhibit NF-κB and induce SOCS3. Tryptophan metabolites activate AhR and exert antioxidant effects. Together, these compounds synergistically inhibit NF-κB activation and NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and modulate JAK–STAT signaling, promoting an overall anti-inflammatory state and immune homeostasis. SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; Trp, Tryptophan; GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor; FXR, Farnesoid X receptor; AhR, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3; mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species; cAMP, Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate; PKA, Protein Kinase A; TGF, Transforming Growth Factor; IL, Interleukin; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor.

5.1 NF-κB signaling pathway

The gut microbiota finely and complexly regulates the host NF-κB pathway through its metabolites, a process that is crucial for maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis. The core mechanisms include the following: short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyrate) stabilize IκBα by inhibiting HDAC (96) and activate GPR43/GPR41 to trigger β-arrestin-2 or cAMP/PKA signaling, collectively blocking NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity (97, 98); tryptophan activates AhR, which directly antagonizes the NF-κB subunit p65 in the nucleus, inhibiting proinflammatory gene expression (99); bile acids inhibit IKK by activating the membrane receptor TGR5 (100), while nuclear receptor FXR activation induces the inhibitory protein SHP, dually inhibiting NF-κB activation (101); and microbiota metabolites indirectly inhibit the excessive activation of the TLR/NF-κB pathway by maintaining epithelial barrier integrity and reducing exposure to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (such as LPS) (102). Once this dynamic balance is disrupted (dysbiosis), harmful bacterial products (such as LPS) drive strong TLR4-mediated IKK phosphorylation, leading to sustained NF-κB activation and the development of chronic inflammatory diseases (such as IBD and metabolic syndrome) (103, 104). Therefore, by directly intervening in kinase activity and nuclear receptor interactions, the microbiota metabolic network precisely regulates the intensity of NF-κB signaling, serving as a core hub for intestinal immune balance.

5.2 The NLRP3 inflammasome

Gut microbiota metabolites precisely regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation through bidirectional, dynamic mechanisms, processes that are crucial for maintaining intestinal immune balance. On the one hand, specific microbiota products can directly activate or sensitize NLRP3: extracellular ATP released by bacterial death triggers K+ efflux and Ca²+ influx via the P2X7 receptor; pore-forming toxins (e.g., α-toxin) produced by pathogens disrupt cell membrane ion homeostasis; and bacterial nucleic acids/particles upregulate NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression via TLRs, initiating NF-κB signaling, collectively driving inflammasome assembly and IL-1β/IL-18 maturation and release (105). On the other hand, beneficial metabolites from commensal bacteria constitute a powerful inhibitory network: short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyrate) directly block NLRP3 oligomerization and ASC speck formation by inhibiting HDAC (106) and activate the GPR43 receptor, inducing β-arrestin-2 to inhibit inflammatory pathways (97), and tryptophan activates AhR, enhances mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria, upregulates the expression of antioxidant genes, and directly inhibits NLRP3 transcription (107).

5.3 JAK–STAT signaling pathway

Gut microbiota metabolites precisely regulate the JAK–STAT signaling pathway in host cells through multilevel mechanisms, playing a core role in maintaining immune homeostasis and inflammatory balance. The core regulatory strategies include the following: 1) directly inhibiting kinase and STAT activation: SCFAs (e.g., butyrate) upregulate the expression of the negative regulatory protein SOCS3 by inhibiting HDAC activity and blocking JAK kinase activity and STAT (e.g., STAT3/STAT5) phosphorylation (108); simultaneously activating GPR43/GPR41 interferes with the STAT cascade (109); and tryptophan metabolites (indole derivatives, etc.) promote STAT degradation through AhR–STAT protein interactions (110); 2) Nuclear receptor-mediated transcriptional regulation: Bile acids activate the nuclear receptor FXR, downregulate the expression of cytokine receptors such as IL-6R and induce SOCS3, indirectly inhibiting the IL-6-JAK–STAT pathway (111).

6 Regulation of intestinal barrier function by gut microbiota products

6.1 Enhancing tight junction protein expression

Various bioactive molecules produced by gut microbiota metabolism increase the expression and functional integrity of tight junction proteins between epithelial cells through complex and synergistic mechanisms, thereby consolidating the mucosal barrier. Among such molecules, SCFAs (e.g., butyrate and propionate) play a central role: on the one hand, as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis), they directly promote the transcriptional activation of core tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin, claudins, and ZO-1) by increasing histone acetylation levels in the promoter regions of target genes (112, 113); on the other hand, SCFAs activate GPRs (e.g., GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109a) on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells, triggering intracellular signaling cascades, such as activating the AMPK/mTOR pathway, thereby regulating the synthesis, phosphorylation status and localization of tight junction proteins to the cell membrane, thus enhancing junction stability (114, 115). Additionally, tryptophan metabolites (e.g., indole and its derivatives) act as AhR ligands, activating the AhR signaling pathway and inducing downstream target gene expression, including directly or indirectly promoting the transcription of various tight junction proteins and inhibiting the production of proinflammatory factors, thus reducing inflammation-induced damage to tight junctions (116, 117). Secondary bile acids regulate the expression of tight junction-related genes by activating FXR or the membrane receptor TGR5 (118, 119). Moreover, some polyamines produced by bacteria can promote cell proliferation and repair, indirectly supporting the maintenance of tight junction structures (120). These microbial products also generally have potent anti-inflammatory effects, reducing the levels of cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ by inhibiting proinflammatory pathways such as the NF-κB pathway. These inflammatory factors are known to be potent inhibitors and disruptors of tight junction protein expression (121, 122). Therefore, gut microbiota metabolites work synergistically through multiple targets (epigenetic regulation, receptor signaling, and anti-inflammatory activity) to increase the expression abundance and function of tight junction proteins, establishing and strengthening the physical defence against external harmful substances, serving as an indispensable driving force for maintaining intestinal epithelial barrier homeostasis.

6.2 Regulating intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis

Studies have shown that SCFAs promote the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (123, 124). This process is crucial for maintaining the integrity and function of the intestinal epithelium. In mouse models, SCFA supplementation has been shown to increase the proliferative capacity of intestinal epithelial cells and promote cell growth and regeneration, thereby accelerating repair after injury (125). Furthermore, SCFAs promote intestinal epithelial proliferation and repair by regulating the expression of cell cycle-related proteins (such as Cyclin D3), which has potential clinical significance for treating intestinal inflammation (126).

The metabolism of secondary bile acids (e.g., deoxycholic acid) in the intestine has also been shown to play important roles in regulating the survival and apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells. Studies indicate that secondary bile acids can inhibit the necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells by activating FXR, thereby enhancing intestinal barrier function (127). In mouse DSS-induced colitis models, treatment with secondary bile acids significantly reduced the apoptosis rate of intestinal epithelial cells, promoted epithelial cell proliferation, and improved the overall health status of the intestine (128). Additionally, the regulatory effect of secondary bile acids on the gut microbiota also supports the mechanism by which they protect the intestinal epithelium by altering the composition of gut microbes, further enhancing intestinal barrier integrity and function (31).

7 Potential therapeutic strategies based on gut microbiota products

7.1 Probiotic and prebiotic interventions

Based on the core mechanism through which gut microbiota metabolites regulate intestinal homeostasis, probiotic and prebiotic interventions have become promising strategies for treating enteritis (such as IBD). The core strategy is to restore homeostatic levels of microbiota products with barrier repair and anti-inflammatory effects by reshaping the dysregulated microbial community and its metabolic activity, thereby alleviating intestinal inflammation (129). Probiotics (e.g., specific strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus) directly supplement symbiotic bacteria that produce SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites, or secondary bile acids; while colonizing or transiently surviving in the gut, they not only competitively inhibit pathogen growth but also directly secrete metabolites such as SCFAs, indole compounds, and polyamines (130–133). These substances synergistically repair the physical barrier and suppress local inflammatory responses by promoting epithelial repair or enhancing tight junction protein expression. Moreover, prebiotics (such as pectin, resistant starch, fructooligosaccharides, and other indigestible fibers) act as selective substrates, specifically stimulating the expansion and metabolism of host SCFA-producing bacteria (such as Eubacterium and Roseburia), significantly increasing intestinal concentrations of SCFAs and markedly increasing the overall richness of the microbiota (131). Furthermore, the combined use of probiotics and prebiotics (synbiotics) can produce synergistic effects, and the functional efficacy of synbiotics is superior to that of probiotics or prebiotics alone (134), demonstrating good potential value for intestinal health interventions. Clinical evidence has shown that synbiotics as adjuvant therapy can alleviate symptoms and are well tolerated by patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis (UC), but the differences in efficacy among different formulations still need to be investigated further (135, 136). Notably, the effects of probiotics in the remission phase of UC are relatively limited (137), and there are application limitations such as low bioactivity and short retention times (138, 139), prompting researchers to explore alternative strategies such as postbiotics (140). Novel prebiotics such as functional oligosaccharides show therapeutic potential by regulating microbiota metabolic pathways (141), but more rigorously designed clinical trials are needed to verify their specific efficacy (142). Overall, such microecological modulators, as multitarget intervention strategies, have important application prospects in the comprehensive management of UC (143).

7.2 Direct administration of microbiota metabolites

UC patients often lack certain microbiota metabolites, and these molecules play key roles in maintaining intestinal homeostasis (31, 144, 145). In preclinical studies, direct supplementation with these products has shown encouraging results. For example, in DSS- or TNBS-induced mouse colitis models, the administration of sodium butyrate via enema or drinking water not only significantly improved the disease activity index, reduced histological damage, and decreased proinflammatory cytokine levels but also promoted the restoration of the gut microbial community balance (146); similarly, the administration of the ellagic acid metabolite urolithin A also effectively alleviated inflammation in animal models (147). Although clinical translation is not yet a reality, preliminary evidence from human trials supports the potential of the direct administration of microbiota metabolites. For instance, several small clinical trials have shown that oral butyrate as an adjunctive therapy for UC can alleviate clinical symptoms, improve endoscopic scores, and reduce histological inflammation, with good safety (148–150). Indole derivatives (such as IPA and indole-3-aldehyde) produced by the microbial metabolism of tryptophan are key ligands for AhR. The activation of AhR signaling is crucial for maintaining epithelial barrier integrity, promoting IL-22-mediated repair, and regulating immune cell function (151). Furumatsu (152) et al. reported that mice lacking AhR are more susceptible to colitis than wild-type mice are. Providing these ligands (e.g., oral indole-3-carbinol) as a supplement in mouse colitis models significantly alleviated colitis (153).

The direct administration of gut microbiota products represents a “functional replacement” precision treatment strategy. This strategy aims to repair damaged intestinal homeostasis by supplementing key ecological niche molecules missing in UC patients and directly acting on host epithelial and immune cells, opening a highly promising new direction for developing the next generation of efficient and safe UC therapies.

7.3 Fecal microbiota transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), as an emerging treatment method, has progressed from initial validation to in-depth mechanistic exploration and protocol optimization in the latest research on intestinal disease treatment. The current consensus is that FMT shows significant and promising efficacy for refractory UC (154). Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have indicated that the rate of clinical remission induced by multiple FMT procedures via colonoscopy can exceed 50%. The core mechanisms of FMT include reconstructing the intestinal microecological balance, restoring the function of beneficial microbes (such as SCFA-producing bacteria), strengthening intestinal barrier integrity, and regulating host immune responses (e.g., increasing Tregs) (155–158). However, efficacy is highly dependent on the donor, and the “superdonor” phenomenon (i.e., the microbiota from certain healthy donors consistently yields better efficacy) has become a research focus; the microbiota characteristics of superdonors typically include high diversity and specific metabolic functions (156, 157). In contrast, evidence for FMT in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) remains weak and inconsistent, but FMT has shown potential for alleviating concurrent Clostridium difficile infection and some intestinal symptoms (159).

8 Limitations and future directions

Although significant progress has been made in recent years regarding the role of the gut microbiota and its metabolites in the immunoregulation of enteritis, the current research still has certain limitations. First, most studies are still in the basic research stage, clinical trials are relatively limited, and sample sizes are small, making it difficult to generalize results to broader populations (160). Second, the high individual variability in the gut microbiota leads to considerable fluctuations in the effectiveness of interventions, and unified standardized treatment protocols are lacking (161). Furthermore, the interactions between different microbiota metabolites (such as SCFAs, tryptophan metabolites, and bile acids) and their specific regulatory mechanisms in the complex in vivo environment are not fully understood (162), especially their dynamic changes under different pathological conditions, which still require further exploration (163, 164).

The following research directions should be considered in future studies: First, in-depth analyses of the specific mechanisms of action of particular microbiota metabolites on immune cell signaling pathways, especially their differential effects on different cell types and inflammatory environments (162, 165), are warranted; second, more high-quality, large-sample clinical studies should be conducted to validate the efficacy and safety of strategies such as probiotics, prebiotics, postbiotics, and the direct administration of microbiota metabolites (160, 166); third, multiomics technologies (such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and single-cell sequencing) should be combined to establish personalized gut microbiota intervention models for precision treatment (161); and fourth, the extended effects of microbiota–host interactions in extraintestinal organs (such as lungs and joints) and systemic diseases should be explored, expanding the clinical application scope of gut microbiota regulation (167, 168).

9 Conclusion

In summary, the gut microbiota and its metabolites play crucial roles in the immunoregulation of enteritis. Through multiple mechanisms, such as regulating immune cell function, influencing inflammatory signaling pathways, and enhancing intestinal barrier integrity, these processes collectively maintain intestinal homeostasis. Current research not only reveals the close relationships among microbiota diversity, metabolic functions, and the pathogenesis and progression of enteritis but also provides a theoretical basis for the development of novel microbiota-based treatment strategies (such as probiotics and FMT).

Although challenges such as unclear mechanisms, significant individual differences, and difficulties in clinical translation remain (160), with the continuous advancement of research methods and in-depth interdisciplinary collaboration, the application prospects of gut microbiota products in enteritis treatment could be very broad. Future studies should continue to explore the underlying mechanisms in greater detail, optimize intervention strategies, and promote clinical translation. Ultimately, this work will provide more effective and personalized treatment plans for patients with enteritis, improving their quality of life and health outcomes.

Statements

Author contributions

SY: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. MZ: Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZD: Supervision, Writing – original draft. BT: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. JL: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82400472), the Anhui Postdoctoral Scientific Research Program Foundation (Grant No. 2025C1205), and the Anhui Provincial University Natural Sciences Research Project (Grant No. 2022AH051137).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Qiu P Ishimoto T Fu L Zhang J Zhang Z Liu Y . The gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:733992. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.733992

2

Wu Z Huang S Li T Li N Han D Zhang B et al . Gut microbiota from green tea polyphenol-dosed mice improves intestinal epithelial homeostasis and ameliorates experimental colitis. Microbiome. (2021) 9:184. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01115-9

3

Li B Du P Du Y Zhao D Cai Y Yang Q et al . Luteolin alleviates inflammation and modulates gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis rats. Life Sci. (2021) 269:119008. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.119008

4

Wan T Wang Y He K Zhu S . Microbial sensing in the intestine. Protein Cell. (2023) 14:824–60. doi: 10.1093/procel/pwad028

5

Wang J He M Yang M Ai X . Gut microbiota as a key regulator of intestinal mucosal immunity. Life Sci. (2024) 345:122612. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122612

6

Duan H Wang L Huangfu M Li H . The impact of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids on macrophage activities in disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. BioMed Pharmacother. (2023) 165:115276. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115276

7

Huang H Yang C Li S Zhan H Tan J Chen C et al . Lizhong decoction alleviates experimental ulcerative colitis via regulating gut microbiota-SCFAs-Th17/Treg axis. J Ethnopharmacol. (2025) 349:119958. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2025.119958

8

Nieves KM Flannigan KL Hughes E Stephens M Thorne AJ Delanne-Cumenal A et al . Indole-3-propionic acid protects medium-diversity colitic mice via barrier enhancement preferentially over anti-inflammatory effects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2025) 328:G696–715. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00256.2024

9

Yadegar A Bar-Yoseph H Monaghan TM Pakpour S Severino A Kuijper EJ et al . Fecal microbiota transplantation: current challenges and future landscapes. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2024) 37:e0006022. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00060-22

10

Haneishi Y Furuya Y Hasegawa M Picarelli A Rossi M Miyamoto J . Inflammatory bowel diseases and gut microbiota. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:(4). doi: 10.3390/ijms24043817

11

Wang N Li Z Cao L Cui Z . Trilobatin ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in mice via the NF-kappaB pathway and alterations in gut microbiota. PloS One. (2024) 19:e0305926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0305926

12

Ren K Yong C Jin Y Rong S Xue K Cao B et al . Unraveling the microbial mysteries: gut microbiota’s role in ulcerative colitis. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1519974. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1519974

13

Shoham S Pintel N Avni D . Oxidative stress, gut bacteria, and microalgae: A holistic approach to manage inflammatory bowel diseases. Antioxidants (Basel Switzerland). (2025) 14:(6). doi: 10.3390/antiox14060697

14

Zhang D Jian YP Zhang YN Li Y Gu LT Sun HH et al . Short-chain fatty acids in diseases. Cell Commun Signal. (2023) 21:212. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01219-9

15

Guo Y Yu Y Li H Ding X Li X Jing X et al . Inulin supplementation ameliorates hyperuricemia and modulates gut microbiota in Uox-knockout mice. Eur J Nutr. (2021) 60:2217–30. doi: 10.1007/s00394-020-02414-x

16

Yang W Yu T Huang X Bilotta AJ Xu L Lu Y et al . Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4457. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18262-6

17

Tagliamonte S Laiola M Ferracane R Vitale M Gallo MA Meslier V et al . Mediterranean diet consumption affects the endocannabinoid system in overweight and obese subjects: possible links with gut microbiome, insulin resistance and inflammation. Eur J Nutr. (2021) 60:3703–16. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02538-8

18

Koh A De Vadder F Kovatcheva-Datchary P Backhed F . From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. (2016) 165:1332–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041

19

Zhang L Liu C Jiang Q Yin Y . Butyrate in energy metabolism: there is still more to learn. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 32:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.12.003

20

Kimura I Ichimura A Ohue-Kitano R Igarashi M . Free fatty acid receptors in health and disease. Physiol Rev. (2020) 100:171–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2018

21

Shimizu H Masujima Y Ushiroda C Mizushima R Ohue-Kitano R Kimura I . Dietary short-chain fatty acid intake improves the hepatic metabolic condition via FFAR3. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:16574. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53242-x

22

Kimura I Ozawa K Inoue D Imamura T Kimura K Maeda T et al . The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun. (2013) 4:1829. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2852

23

Su X Gao Y Yang R . Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites maintain gut and systemic homeostasis. Cells. (2022) 11:(15). doi: 10.3390/cells11152296

24

Lavelle A Sokol H . Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 17:223–37. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0258-z

25

Pasupalak JK Rajput P Gupta GL . Gut microbiota and Alzheimer’s disease: Exploring natural product intervention and the Gut-Brain axis for therapeutic strategies. Eur J Pharmacol. (2024) 984:177022. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.177022

26

Dai G Chen X He Y . The gut microbiota activates ahR through the tryptophan metabolite kyn to mediate renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:712327. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.712327

27

Su X Zhang M Qi H Gao Y Yang Y Yun H et al . Gut microbiota-derived metabolite 3-idoleacetic acid together with LPS induces IL-35(+) B cell generation. Microbiome. (2022) 10:13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01205-8

28

Chen LM Bao CH Wu Y Liang SH Wang D Wu LY et al . Tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism: a link between the gut and brain for depression in inflammatory bowel disease. J Neuroinflamm. (2021) 18:135. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02175-2

29

Ala M . Tryptophan metabolites modulate inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer by affecting immune system. Int Rev Immunol. (2022) 41:326–45. doi: 10.1080/08830185.2021.1954638

30

Whitfield-Cargile CM Cohen ND Chapkin RS Weeks BR Davidson LA Goldsby JS et al . The microbiota-derived metabolite indole decreases mucosal inflammation and injury in a murine model of NSAID enteropathy. Gut Microbes. (2016) 7:246–61. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1156827

31

Cai J Sun L Gonzalez FJ . Gut microbiota-derived bile acids in intestinal immunity, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cell Host Microbe. (2022) 30:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.02.004

32

Kuhn T Stepien M Lopez-Nogueroles M Damms-MaChado A Sookthai D Johnson T et al . Prediagnostic plasma bile acid levels and colon cancer risk: A prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2020) 112:516–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz166

33

Lee JWJ Plichta D Hogstrom L Borren NZ Lau H Gregory SM et al . Multi-omics reveal microbial determinants impacting responses to biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. (2021) 29:1294–1304 e1294. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.019

34

Wang S Dong W Liu L Xu M Wang Y Liu T et al . Interplay between bile acids and the gut microbiota promotes intestinal carcinogenesis. Mol Carcinog. (2019) 58:1155–67. doi: 10.1002/mc.22999

35

Hasan MN Wang H Luo W Du Y Li T . Gly-betaMCA modulates bile acid metabolism to reduce hepatobiliary injury in Mdr2 KO mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2025) 329:G45–57. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00044.2025

36

Chiang JYL Ferrell JM . Bile acid receptors FXR and TGR5 signaling in fatty liver diseases and therapy. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2020) 318:G554–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00223.2019

37

Kuang J Wang J Li Y Li M Zhao M Ge K et al . Hyodeoxycholic acid alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through modulating the gut-liver axis. Cell Metab. (2023) 35:1752–1766 e1758. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2023.07.011

38

Xu M Cen M Shen Y Zhu Y Cheng F Tang L et al . Deoxycholic acid-induced gut dysbiosis disrupts bile acid enterohepatic circulation and promotes intestinal inflammation. Dig Dis Sci. (2021) 66:568–76. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06208-3

39

Xu M Shen Y Cen M Zhu Y Cheng F Tang L et al . Modulation of the gut microbiota-farnesoid X receptor axis improves deoxycholic acid-induced intestinal inflammation in mice. J Crohns Colitis. (2021) 15:1197–210. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab003

40

Gubatan J Holman DR Puntasecca CJ Polevoi D Rubin SJ Rogalla S . Antimicrobial peptides and the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. (2021) 27:7402–22. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i43.7402

41

Gobert AP Latour YL Asim M Barry DP Allaman MM Finley JL et al . Protective role of spermidine in colitis and colon carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. (2022) 162:813–827 e818. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.11.005

42

Carriche GM Almeida L Stuve P Velasquez L Dhillon-LaBrooy A Roy U et al . Regulating T-cell differentiation through the polyamine spermidine. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2021) 147:335–348 e311. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.037

43

Niechcial A Schwarzfischer M Wawrzyniak M Atrott K Laimbacher A Morsy Y et al . Spermidine ameliorates colitis via induction of anti-inflammatory macrophages and prevention of intestinal dysbiosis. J Crohns Colitis. (2023) 17:1489–503. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad058

44

Peterson CT Rodionov DA Osterman AL Peterson SN . B vitamins and their role in immune regulation and cancer. Nutrients. (2020) 12:(11). doi: 10.3390/nu12113380

45

Uebanso T Shimohata T Mawatari K Takahashi A . Functional roles of B-vitamins in the gut and gut microbiome. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2020) 64:e2000426. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202000426

46

Dalayeli N Hajhashemi V Talebi A Minaiyan M . Investigating the impact of selected B vitamins (B1, B2, B6, and B12) on acute colitis induced experimentally in rats. Int J Prev Med. (2024) 15:61. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.ijpvm_232_23

47

Parada Venegas D de la Fuente MK Landskron G Gonzalez MJ Quera R Dijkstra G et al . Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:277. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277

48

Haghikia A Jorg S Duscha A Berg J Manzel A Waschbisch A et al . Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity. (2015) 43:817–29. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.007

49

Yu X Ou J Wang L Li Z Ren Y Xie L et al . Gut microbiota modulate CD8(+) T cell immunity in gastric cancer through Butyrate/GPR109A/HOPX. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2307542. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2307542

50

Jiang ZM Zeng SL Huang TQ Lin Y Wang FF Gao XJ et al . Sinomenine ameliorates rheumatoid arthritis by modulating tryptophan metabolism and activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor via gut microbiota regulation. Sci Bull (Beijing). (2023) 68:1540–55. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2023.06.027

51

Ma Z Akhtar M Pan H Liu Q Chen Y Zhou X et al . Fecal microbiota transplantation improves chicken growth performance by balancing jejunal Th17/Treg cells. Microbiome. (2023) 11:137. doi: 10.1186/s40168-023-01569-z

52

Liu X Yang M Xu P Du M Li S Shi J et al . Kynurenine-AhR reduces T-cell infiltration and induces a delayed T-cell immune response by suppressing the STAT1-CXCL9/CXCL10 axis in tuberculosis. Cell Mol Immunol. (2024) 21:1426–40. doi: 10.1038/s41423-024-01230-1

53

Chang L Wang C Peng J Yuan M Zhang Z Xu Y et al . Sea buckthorn polysaccharides regulate bile acids synthesis and metabolism through FXR to improve th17/treg immune imbalance caused by high-fat diet. J Agric Food Chem. (2025) 73:15376–88. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5c00409

54

Zhang Y Gao X Gao S Liu Y Wang W Feng Y et al . Effect of gut flora mediated-bile acid metabolism on intestinal immune microenvironment. Immunology. (2023) 170:301–18. doi: 10.1111/imm.13672

55

Lindner S Miltiadous O Ramos RJF Paredes J Kousa AI Dai A et al . Altered microbial bile acid metabolism exacerbates T cell-driven inflammation during graft-versus-host disease. Nat Microbiol. (2024) 9:614–30. doi: 10.1038/s41564-024-01617-w

56

Zheng C Wang L Zou T Lian S Luo J Lu Y et al . Ileitis promotes MASLD progression via bile acid modulation and enhanced TGR5 signaling in ileal CD8(+) T cells. J Hepatol. (2024) 80:764–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.12.024

57

Takada R Watanabe T Hara A Sekai I Kurimoto M Otsuka Y et al . NOD2 deficiency protects mice from the development of adoptive transfer colitis through the induction of regulatory T cells expressing forkhead box P3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2021) 568:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.068

58

Yan JB Luo MM Chen ZY He BH . The function and role of the th17/treg cell balance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res. (2020) 2020:8813558. doi: 10.1155/2020/8813558

59

Hosseinkhani F Heinken A Thiele I Lindenburg PW Harms AC Hankemeier T . The contribution of gut bacterial metabolites in the human immune signaling pathway of non-communicable diseases. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1–22. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1882927

60

Glassner KL Abraham BP Quigley EMM . The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 145:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.003

61

Wang X Yuan W Yang C Wang Z Zhang J Xu D et al . Emerging role of gut microbiota in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1365554. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1365554

62

Wong CC Yu J . Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2023) 20:429–52. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00766-x

63

Kim M Qie Y Park J Kim CH . Gut microbial metabolites fuel host antibody responses. Cell Host Microbe. (2016) 20:202–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.001

64

Sanchez HN Moroney JB Gan H Shen T Im JL Li T et al . B cell-intrinsic epigenetic modulation of antibody responses by dietary fiber-derived short-chain fatty acids. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:60. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13603-6

65

Yu B Pei C Peng W Zheng Y Fu Y Wang X et al . Microbiota-derived butyrate alleviates asthma via inhibiting Tfh13-mediated IgE production. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10:181. doi: 10.1038/s41392-025-02263-2

66

Rosser EC Piper CJM Matei DE Blair PA Rendeiro AF Orford M et al . Microbiota-derived metabolites suppress arthritis by amplifying aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation in regulatory B cells. Cell Metab. (2020) 31:837–851 e810. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.03.003

67

Metur SP Klionsky DJ . The curious case of polyamines: spermidine drives reversal of B cell senescence. Autophagy. (2020) 16:389–90. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1698210

68

Bang YJ Hu Z Li Y Gattu S Ruhn KA Raj P et al . Serum amyloid A delivers retinol to intestinal myeloid cells to promote adaptive immunity. Science. (2021) 373:eabf9232. doi: 10.1126/science.abf9232

69

Vinolo MA Hatanaka E Lambertucci RH Newsholme P Curi R . Effects of short chain fatty acids on effector mechanisms of neutrophils. Cell Biochem Funct. (2009) 27:48–55. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1533

70

Carrillo-Salinas FJ Parthasarathy S Moreno de Lara L Borchers A Ochsenbauer C Panda A et al . Short-chain fatty acids impair neutrophil antiviral function in an age-dependent manner. Cells. (2022) 11:(16). doi: 10.3390/cells11162515

71

Miller A Fantone KM Tucker SL Gokanapudi N Goldberg JB Rada B . Short chain fatty acids reduce the respiratory burst of human neutrophils in response to cystic fibrosis isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Cyst Fibros. (2023) 22:756–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.04.022

72

Anderson G Carbone A Mazzoccoli G . Tryptophan metabolites and aryl hydrocarbon receptor in severe acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus-2 (SARS-coV-2) pathophysiology. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:(4). doi: 10.3390/ijms22041597

73

Chen Y Song S Wang Y Wu L Wu J Jiang Z et al . Topical application of magnolol ameliorates psoriasis-like dermatitis by inhibiting NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway and regulating tryptophan metabolism. Bioorg Chem. (2025) 154:108059. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2024.108059

74

Alexeev EE Dowdell AS Henen MA Lanis JM Lee JS Cartwright IM et al . Microbial-derived indoles inhibit neutrophil myeloperoxidase to diminish bystander tissue damage. FASEB J. (2021) 35:e21552. doi: 10.1096/fj.202100027R

75

Jiang SS Xie YL Xiao XY Kang ZR Lin XL Zhang L et al . Fusobacterium nucleatum-derived succinic acid induces tumor resistance to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe. (2023) 31:781–797 e789. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2023.04.010

76

Li H Tan H Liu Z Pan S Tan S Zhu Y et al . Succinic acid exacerbates experimental autoimmune uveitis by stimulating neutrophil extracellular traps formation via SUCNR1 receptor. Br J Ophthalmol. (2023) 107:1744–9. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-320880

77

Wang G Liu J Zhang Y Xie J Chen S Shi Y et al . Ginsenoside Rg3 enriches SCFA-producing commensal bacteria to confer protection against enteric viral infection via the cGAS-STING-type I IFN axis. ISME J. (2023) 17:2426–40. doi: 10.1038/s41396-023-01541-7

78

Fiorucci S Biagioli M Zampella A Distrutti E . Bile acids activated receptors regulate innate immunity. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1853. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01853

79

Sukka SR Ampomah PB Darville LNF Ngai D Wang X Kuriakose G et al . Efferocytosis drives a tryptophan metabolism pathway in macrophages to promote tissue resolution. Nat Metab. (2024) 6:1736–55. doi: 10.1038/s42255-024-01115-7

80

Chen S Putnik R Li X Diwaker A Vasconcelos M Liu S et al . PGLYRP1-mediated intracellular peptidoglycan detection promotes intestinal mucosal protection. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:1864. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-57126-9

81

Lee K Kwak JH Pyo S . Inhibition of LPS-induced inflammatory mediators by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in macrophages through suppression of PI3K/NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Food Funct. (2016) 7:3073–82. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00187d

82

Pols TW Nomura M Harach T Lo Sasso G Oosterveer MH Thomas C et al . TGR5 activation inhibits atherosclerosis by reducing macrophage inflammation and lipid loading. Cell Metab. (2011) 14:747–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.11.006

83

Xiao P Cai X Zhang Z Guo K Ke Y Hu Z et al . Butyrate prevents the pathogenic anemia-inflammation circuit by facilitating macrophage iron export. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2024) 11:e2306571. doi: 10.1002/advs.202306571

84

Shi Y Su W Zhang L Shi C Zhou J Wang P et al . TGR5 regulates macrophage inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by modulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:609060. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.609060

85

Scott NA Andrusaite A Andersen P Lawson M Alcon-Giner C Leclaire C et al . Antibiotics induce sustained dysregulation of intestinal T cell immunity by perturbing macrophage homeostasis. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:(464). doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao4755

86

Liang L Liu L Zhou W Yang C Mai G Li H et al . Gut microbiota-derived butyrate regulates gut mucus barrier repair by activating the macrophage/WNT/ERK signaling pathway. Clin Sci (Lond). (2022) 136:291–307. doi: 10.1042/CS20210778

87

Xie Q Li Q Fang H Zhang R Tang H Chen L . Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids and macrophage modulation: exploring therapeutic potentials in pulmonary fungal infections. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2024) 66:316–27. doi: 10.1007/s12016-024-08999-z

88

Hays KE Pfaffinger JM Ryznar R . The interplay between gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and implications for host health and disease. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2393270. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2393270

89

Zhang Y Tu S Ji X Wu J Meng J Gao J et al . Dubosiella newyorkensis modulates immune tolerance in colitis via the L-lysine-activated AhR-IDO1-Kyn pathway. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:1333. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-45636-x

90

Jia H He X Jiang T Kong F . Roles of bile acid-activated receptors in monocytes-macrophages and dendritic cells. Cells. (2025) 14:(12). doi: 10.3390/cells14120920

91

Hu J Wang C Huang X Yi S Pan S Zhang Y et al . Gut microbiota-mediated secondary bile acids regulate dendritic cells to attenuate autoimmune uveitis through TGR5 signaling. Cell Rep. (2021) 36:109726. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109726

92

Andrusaite A Lewis J Frede A Farthing A Kastele V Montgomery J et al . Microbiota-derived butyrate inhibits cDC development via HDAC inhibition, diminishing their ability to prime T cells. Mucosal Immunol. (2024) 17:1199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.mucimm.2024.08.003

93

Zhang Y Zhao M He J Chen L Wang W . In vitro and in vivo immunomodulatory activity of acetylated polysaccharides from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves. Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 259:129174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.129174

94

Yuan X Tang H Wu R Li X Jiang H Liu Z et al . Short-chain fatty acids calibrate RARalpha activity regulating food sensitization. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:737658. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.737658

95

Wang J Zhu N Su X Gao Y Yang R . Gut-microbiota-derived metabolites maintain gut and systemic immune homeostasis. Cells. (2023) 12:(5). doi: 10.3390/cells12050793

96

Zhong H Yu H Chen J Mok SWF Tan X Zhao B et al . The short-chain fatty acid butyrate accelerates vascular calcification via regulation of histone deacetylases and NF-kappaB signaling. Vascul Pharmacol. (2022) 146:107096. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2022.107096

97

Park BO Kang JS Paudel S Park SG Park BC Han SB et al . Novel GPR43 agonists exert an anti-inflammatory effect in a colitis model. Biomol Ther (Seoul). (2022) 30:48–54. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2021.078

98

Yan F Wang X Du Y Zhao Z Shi L Cao T et al . Pumpkin Soluble Dietary Fiber instead of Insoluble One Ameliorates Hyperglycemia via the Gut Microbiota-Gut-Liver Axis in db/db Mice. J Agric Food Chem. (2025) 73:1293–307. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c08986

99

Zhang J Gao T Chen G Liang Y Nie X Gu W et al . Vinegar-processed Schisandra Chinensis enhanced therapeutic effects on colitis-induced depression through tryptophan metabolism. Phytomedicine. (2024) 135:156057. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156057

100

Zhuo W Li B Zhang D . Activation of G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor Gpbar1 (TGR5) inhibits degradation of type II collagen and aggrecan in human chondrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. (2019) 856:172387. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.05.016

101

Guan B Tong J Hao H Yang Z Chen K Xu H et al . Bile acid coordinates microbiota homeostasis and systemic immunometabolism in cardiometabolic diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B. (2022) 12:2129–49. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.011

102

Malesza IJ Malesza M Walkowiak J Mussin N Walkowiak D Aringazina R et al . High-fat, western-style diet, systemic inflammation, and gut microbiota: A narrative review. Cells. (2021) 10:(11). doi: 10.3390/cells10113164

103

Xiong T Zheng X Zhang K Wu H Dong Y Zhou F et al . Ganluyin ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis by inhibiting the enteric-origin LPS/TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. (2022) 289:115001. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115001

104

Hu N Zhang Y . TLR4 knockout attenuated high fat diet-induced cardiac dysfunction via NF-kappaB/JNK-dependent activation of autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2017) 1863:2001–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.01.010

105

Sarkar SK Gubert C Hannan AJ . The microbiota-inflammasome-brain axis as a pathogenic mediator of neurodegenerative disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2025) 176:106276. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106276

106

Wang W Dernst A Martin B Lorenzi L Cadefau-Fabregat M Phulphagar K et al . Butyrate and propionate are microbial danger signals that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages upon TLR stimulation. Cell Rep. (2024) 43:114736. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114736

107

Cao J Bao Q Hao H . Indole-3-carboxaldehyde alleviates LPS-induced intestinal inflammation by inhibiting ROS production and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Antioxidants (Basel Switzerland). (2024) 13:(9). doi: 10.3390/antiox13091107

108

Gao SM Chen CQ Wang LY Hong LL Wu JB Dong PH et al . Histone deacetylases inhibitor sodium butyrate inhibits JAK2/STAT signaling through upregulation of SOCS1 and SOCS3 mediated by HDAC8 inhibition in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Exp Hematol. (2013) 41:261–270 e264. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2012.10.012

109

Tao Z Wang Y . The health benefits of dietary short-chain fatty acids in metabolic diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2025) 65:1579–92. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2023.2297811

110

Korac K Rajasekaran D Sniegowski T Schniers BK Ibrahim AF Bhutia YD . Carbidopa, an activator of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, suppresses IDO1 expression in pancreatic cancer and decreases tumor growth. Biochem J. (2022) 479:1807–24. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210851

111

Girisa S Henamayee S Parama D Rana V Dutta U Kunnumakkara AB . Targeting Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) for developing novel therapeutics against cancer. Mol BioMed. (2021) 2:21. doi: 10.1186/s43556-021-00035-2

112

Karoor V Strassheim D Sullivan T Verin A Umapathy NS Dempsey EC et al . The short-chain fatty acid butyrate attenuates pulmonary vascular remodeling and inflammation in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:(18). doi: 10.3390/ijms22189916

113

Wang K Wang K Wang J Yu F Ye C . Protective Effect of Clostridium butyricum on Escherichia coli-Induced Endometritis in Mice via Ameliorating Endometrial Barrier and Inhibiting Inflammatory Response. Microbiol Spectr. (2022) 10:e0328622. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03286-22

114

Hu L Sun L Yang C Zhang DW Wei YY Yang MM et al . Gut microbiota-derived acetate attenuates lung injury induced by influenza infection via protecting airway tight junctions. J Trans Med. (2024) 22:570. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05376-4

115

Zhang Y Jiang H Peng XH Zhao YL Huang XJ Yuan K et al . Mulberry leaf improves type 2 diabetes in mice via gut microbiota-SCFAs-GPRs axis and AMPK signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. (2025) 145:156970. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156970

116

Li Y Han Y Wang X Yang X Ren D . Kiwifruit polysaccharides alleviate ulcerative colitis via regulating gut microbiota-dependent tryptophan metabolism and promoting colon fucosylation. J Agric Food Chem. (2024) 72:23859–74. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.4c06435

117

Zhang Y Han L Dong J Yuan Z Yao W Ji P et al . Shaoyao decoction improves damp-heat colitis by activating the AHR/IL-22/STAT3 pathway through tryptophan metabolism driven by gut microbiota. J Ethnopharmacol. (2024) 326:117874. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2024.117874

118

Li G Wang X Liu Y Gong S Yang Y Wang C et al . Bile acids supplementation modulates lipid metabolism, intestinal function, and cecal microbiota in geese. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1185218. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1185218

119

Xie XM Zhang BY Feng S Fan ZJ Wang GY . Activation of gut FXR improves the metabolism of bile acids, intestinal barrier, and microbiota under cholestatic condition caused by GCDCA in mice. Microbiol Spectr. (2025) 13:e0315024. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03150-24

120

Ma L Ni Y Wang Z Tu W Ni L Zhuge F et al . Spermidine improves gut barrier integrity and gut microbiota function in diet-induced obese mice. Gut Microbes. (2020) 12:1–19. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1832857

121

Yan B Mao X Hu S Wang S Liu X Sun J . Spermidine protects intestinal mucosal barrier function in mice colitis via the AhR/Nrf2 and AhR/STAT3 signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. (2023) 119:110166. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110166

122

Ma L Ni L Yang T Mao P Huang X Luo Y et al . Preventive and therapeutic spermidine treatment attenuates acute colitis in mice. J Agric Food Chem. (2021) 69:1864–76. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07095

123

Duan C Wu J Wang Z Tan C Hou L Qian W et al . Fucose promotes intestinal stem cell-mediated intestinal epithelial development through promoting Akkermansia-related propanoate metabolism. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2233149. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2233149

124

Kim S Shin YC Kim TY Kim Y Lee YS Lee SH et al . Mucin degrader Akkermansia muciniphila accelerates intestinal stem cell-mediated epithelial development. Gut Microbes. (2021) 13:1–20. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1892441

125

Lenoir M Martin R Torres-Maravilla E Chadi S Gonzalez-Davila P Sokol H et al . Butyrate mediates anti-inflammatory effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in intestinal epithelial cells through Dact3. Gut Microbes. (2020) 12:1–16. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.1826748

126

Siavoshian S Segain JP Kornprobst M Bonnet C Cherbut C Galmiche JP et al . Butyrate and trichostatin A effects on the proliferation/differentiation of human intestinal epithelial cells: induction of cyclin D3 and p21 expression. Gut. (2000) 46:507–14. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.507

127

Han B Lv X Liu G Li S Fan J Chen L et al . Gut microbiota-related bile acid metabolism-FXR/TGR5 axis impacts the response to anti-alpha4beta7-integrin therapy in humanized mice with colitis. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2232143. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2232143

128

Dong S Zhu M Wang K Zhao X Hu L Jing W et al . Dihydromyricetin improves DSS-induced colitis in mice via modulation of fecal-bacteria-related bile acid metabolism. Pharmacol Res. (2021) 171:105767. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105767

129

Rahman MN Barua N Tin MCF Dharmaratne P Wong SH Ip M . The use of probiotics and prebiotics in decolonizing pathogenic bacteria from the gut; a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2356279. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2356279

130

Tan J Dong L Jiang Z Tan L Luo X Pei G et al . Probiotics ameliorate IgA nephropathy by improving gut dysbiosis and blunting NLRP3 signaling. J Trans Med. (2022) 20:382. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03585-3

131

Zheng DW Li RQ An JX Xie TQ Han ZY Xu R et al . Prebiotics-encapsulated probiotic spores regulate gut microbiota and suppress colon cancer. Adv Mater. (2020) 32:e2004529. doi: 10.1002/adma.202004529

132

Xie LW Cai S Lu HY Tang FL Zhu RQ Tian Y et al . Microbiota-derived I3A protects the intestine against radiation injury by activating AhR/IL-10/Wnt signaling and enhancing the abundance of probiotics. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2347722. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2347722

133

Gadaleta RM Cariello M Crudele L Moschetta A . Bile salt hydrolase-competent probiotics in the management of IBD: unlocking the “Bile acid code. Nutrients. (2022) 14:(15). doi: 10.3390/nu14153212

134

Dang L Li D Mu Q Zhang N Li C Wang M et al . Youth-derived Lactobacillus rhamnosus with prebiotic xylo-oligosaccharide exhibits anti-hyperlipidemic effects as a novel synbiotic. Food Res Int. (2024) 195:114976. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114976

135

Zhou S Wang M Li W Zhang Y Zhao T Song Q et al . Comparative efficacy and tolerability of probiotic, prebiotic, and synbiotic formulations for adult patients with mild-moderate ulcerative colitis in an adjunctive therapy: A network meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. (2024) 43:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.11.010

136

Guo J Li L Cai Y Kang Y . The development of probiotics and prebiotics therapy to ulcerative colitis: a therapy that has gained considerable momentum. Cell Commun Signal. (2024) 22:268. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01611-z

137

Liu Y Yin F Huang L Teng H Shen T Qin H . Long-term and continuous administration of Bacillus subtilis during remission effectively maintains the remission of inflammatory bowel disease by protecting intestinal integrity, regulating epithelial proliferation, and reshaping microbial structure and function. Food Funct. (2021) 12:2201–10. doi: 10.1039/d0fo02786c

138

Zhang X Liu S Xin R Hu W Zhang Q Lu Q et al . Reactive oxygen species-responsive prodrug nanomicelle-functionalized Lactobacillus rhamnosus probiotics for amplified therapy of ulcerative colitis. Mater Horiz. (2025) 12:5749–61. doi: 10.1039/d5mh00114e

139

Zhang K Zhu L Zhong Y Xu L Lang C Chen J et al . Prodrug integrated envelope on probiotics to enhance target therapy for ulcerative colitis. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2023) 10:e2205422. doi: 10.1002/advs.202205422

140

Zhang T Zhang W Feng C Kwok LY He Q Sun Z . Stronger gut microbiome modulatory effects by postbiotics than probiotics in a mouse colitis model. NPJ Sci Food. (2022) 6:53. doi: 10.1038/s41538-022-00169-9

141

Liu N Wang H Yang Z Zhao K Li S He N . The role of functional oligosaccharides as prebiotics in ulcerative colitis. Food Funct. (2022) 13:6875–93. doi: 10.1039/d2fo00546h

142

Kennedy JM De Silva A Walton GE Gibson GR . A review on the use of prebiotics in ulcerative colitis. Trends Microbiol. (2024) 32:507–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2023.11.007

143

Chen K Wang H Yang Y Tang C Sun X Zhou J et al . Common mechanisms of Gut microbe-based strategies for the treatment of intestine-related diseases: based on multi-target interactions with the intestinal barrier. Cell Commun Signal. (2025) 23:288. doi: 10.1186/s12964-025-02299-5

144

Wei YH Ma X Zhao JC Wang XQ Gao CQ . Succinate metabolism and its regulation of host-microbe interactions. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2190300. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2190300

145

Su X Yang Y Gao Y Wang J Hao Y Zhang Y et al . Gut microbiota CLA and IL-35 induction in macrophages through Galphaq/11-mediated STAT1/4 pathway: an animal-based study. Gut Microbes. (2024) 16:2437253. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2437253

146

Recharla N Geesala R Shi XZ . Gut microbial metabolite butyrate and its therapeutic role in inflammatory bowel disease: A literature review. Nutrients. (2023) 15:(10). doi: 10.3390/nu15102275

147

Han D Wu Y Lu D Pang J Hu J Zhang X et al . Polyphenol-rich diet mediates interplay between macrophage-neutrophil and gut microbiota to alleviate intestinal inflammation. Cell Death Dis. (2023) 14:656. doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-06190-4

148

Pietrzak A Banasiuk M Szczepanik M Borys-Iwanicka A Pytrus T Walkowiak J et al . Sodium butyrate effectiveness in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel diseases-randomized placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Nutrients. (2022) 14:(16). doi: 10.3390/nu14163283

149

Vernero M De Blasio F Ribaldone DG Bugianesi E Pellicano R Saracco GM et al . The usefulness of microencapsulated sodium butyrate add-on therapy in maintaining remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: A prospective observational study. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:(12). doi: 10.3390/jcm9123941

150