1 Introduction

Public health strategies rely heavily on vaccination to reduce the burden of infectious diseases (1–3). From 1974 to 2024, vaccination is estimated to have prevented 154 million deaths and contributed to 40% of the decline in global infant mortality (4), eradicating once-devastating pathogens (5, 6). The sudden emergence of highly transmissible pathogens can disrupt daily life, increase mortality, and severely affect economic growth, especially in low- and middle income countries (LMICs) (7–9). Several types of vaccines have been developed, with traditional formulations based on attenuated or inactivated pathogens (10–12). Subunit vaccines-based on pathogen proteins- offer a safer and versatile alternative when compared to conventional inactivated or attenuated vaccines, minimizing infection risks while eliciting protective immune responses (13).

Achieving robust and broad immunity depends not only on which pathogen regions are selected as antigens but also on how these regions are presented to the immune system. Immunodominant regions are often the most variable in sequence (14–16), or structurally hidden by post-translational modifications that help pathogens evade recognition (17). Among these modifications, protein N-glycosylation plays a central—and often paradoxical—role in antigen biology and recombinant vaccine antigen design. Enveloped viruses such as HIV-1 or influenza A bear N-linked glycans in their membrane proteins and use the host’s glycosylation to shield important epitopes (18, 19). Notably, N-glycosylation contributes to both viral immune evasion and glycoprotein folding and ER quality control, albeit through distinct glycan structures (20). In patients with congenital disorders of glycosylation such as MOGS-CDG-a disorder caused by mutations in glucosidase I, the first enzyme involved in glycan remodeling after transfer to proteins – the replication of many enveloped viruses is reduced (21, 22). This dual role of N-glycosylation poses a challenge for vaccine development: producing cost-effective antigens while ensuring proper folding and immunogenicity. These underscore the need to conceptually separate the folding and immunogenic functions of N-glycans. Viewing glycans as tunable design elements opens new opportunities for rational, cost-effective, and globally accessible vaccine development. In this article we dissect the roles of N-glycosylation in rational antigenic design.

2 Roles of N-glycosylation in antigen folding and immunogenicity

2.1 N-glycans and glycoprotein folding

N-glycosylation is one of the most frequent post-translational modifications of the secretory pathway: a preassembled oligosaccharide–conserved in mammals, yeast and plants- is added to the consensus sequence N-X-S/T (X cannot be P) of proteins that are entering the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). N-linked glycans participate in protein folding in the ER, 1) by increasing solubility and preventing aggregation of folding intermediates (23, 24), and 2) by allowing the protein interaction with the ER quality control of glycoprotein folding (ERQC) (25, 26). This process ensures that only properly folded glycoproteins proceed to secretory pathway, while misfolded proteins are retrotranslocated to the cytosol and degraded (27).

Several studies have demonstrated the critical role of N-glycosylation in the correct folding of recombinant proteins. For example, expression of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in Nicotiana benthamiana showed that N-glycosylation is essential for proper folding, as mutants generated by site-directed mutagenesis of glycosylation sites could not be produced as soluble proteins (28). Yields of Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) from SARS-CoV-1 expressed in Pichia pastoris decreased with the reduction of N-glycosylation sites (29). Deglycosylated Aspergillus niger α-L-rhamnosidase (r-Rha1), produced in P. pastoris either by in vivo inhibition of N-glycosylation or by in vitro enzymatic deglycosylation, revealed that in vivo inhibition led to greater structural destabilization and a more pronounced loss of enzymatic activity (30). These examples highlight the importance of glycosylation during folding, although individual N-glycosylation sites contribute differently to folding, trafficking or protein function (31, 32).

2.2 N-glycans and immunogenicity of antigens

Once folded glycoproteins leave the ER, their N-glycans undergo species-specific remodeling along the secretory pathway, generating the diversity found in mature proteins: high-mannose, complex, or hybrid forms (33). N-glycans are crucial in host-pathogen and cell-cell interactions and both pathogenicity and infection resistance can depend on glycosylation of secreted or surface proteins (34–38).

Immune-evasion mechanisms, such as masking of conserved epitopes, frequently rely also on glycosylation (39–42) and secreted effector glycoproteins, which may need to be glycosylated to be active and contribute to virulence (43, 44). For example, the Haemophilus influenzae surface glycoprotein HMW1 mediates host-cell adhesion via a membrane-anchored glycan but upon deglycosylation, adhesion is lost (36, 45). HIV, SARS-CoV-2, and Influenza are enveloped viruses whose surface glycoproteins mediate receptor binding and entry, making them major vaccine targets (46, 47). However, evolutionary pressure drives immune-evasion through continual mutation of these immunodominant proteins (48). In influenza, immune response focuses on hemagglutinin (HA), but antigenic drift accumulates mutations, undermining vaccine effectiveness (49, 50). HIV-1 vaccine development faces similar obstacles: the virus has high mutation rates, while heavily glycosylated Env protein shields key epitopes (51–53). For SARS-CoV-2, the immune response mainly targets the Spike glycoprotein, which contains 22 glycosylation sites per monomer (54, 55).

The high structural variability of carbohydrates confers proteins exceptional diversity (56). Their role in immune evasion complicates antigen selection for vaccines (57). Emerging glycoengineering approaches may help overcome these challenges and improve vaccine design.

3 Glycoengineering in vaccine designs

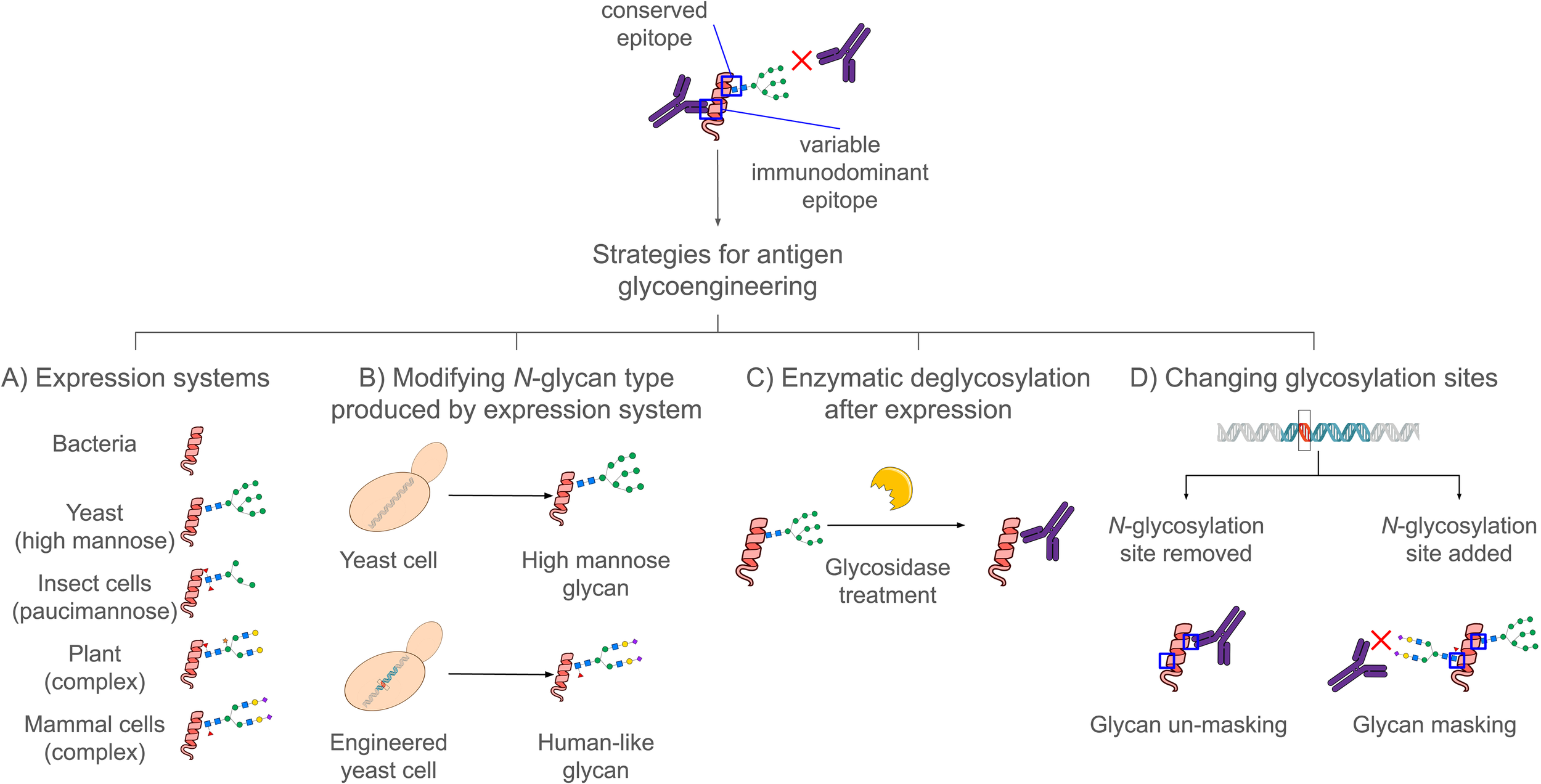

Glycoengineering strategies for improving vaccine antigens involve optimizing the carbohydrate structures attached to proteins to improve immunogenicity, safety, or production yield. As N-glycans influence folding, trafficking and immune recognition, their modification provides a unique opportunity to explore their roles in diverse contexts, expanding vaccine design possibilities. Below, we outline and critically assess the main glycoengineering strategies used to enhance antigen’s performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Strategies in antigen glycoengineering. The monosaccharides follow the Symbol Nomenclature for Graphical Representations of Glycans (58). The enzyme-yellow icon was adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/), licensed under CC-BY 3.0 Unported. All other icons were obtained from BioArt and BioIcons under their respective open licenses.

3.1 Strategy A — choosing the expression system

The glycosylation pattern of a recombinant protein is determined by the host system used for its production (59, 60). Consequently, selecting an expression platform is inherently a form of glycoengineering, as the host dictates the glycan repertoire displayed on the antigen (59, 60). E. coli adds no N-glycans; mammalian cells typically produce complex-type glycans; insect cells generate high-mannose and paucimannose structures; plant cells yield biantennary GlcNAc-terminating N-glycans; and yeasts are characterized by extensive high-mannose N-glycans (61). For SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, the complex-type glycans produced in CHO cells correlate with stronger neutralizing antibody responses in mice when compared to Spike produced in yeast or insect cells (62). Although mammalian cell culture remains the gold standard for producing biotherapeutics, alternative expression systems may offer complementary advantages depending on the antigen and manufacturing context, such as higher expression yields, access to distinct post-translational modifications, or increased process flexibility compared with the native host (63). However, each organism imposes a characteristic “glycan signature” that can alter protein function (56) or elicit an undesired immunogenic response often requiring additional engineering to mitigate these effects (64–66). Thus, understanding system-specific glycosylation is fundamental to subsequent engineering decisions, and the choice of expression host should also consider potential drawbacks, such as the need to remove lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxins from recombinant proteins produced in E. coli for animal or human use (67).

3.2 Strategy B — modifying the N-glycosylation pathway of a cell type

Several strategies aim to homogenize or “humanize” N-glycans in eukaryotic systems such as yeast and plants. For instance, secreted IgG1-Fc with truncated N-glycans extendable into diverse structures was produced in a P. pastoris expressing a Golgi-localized endoglycosidase Endo T (68). This GlycoDelete strategy has also been applied in plants, whose glycoproteins normally contain heterogeneous forms with β-1,2-xylose and core α-1,3-fucose, sugars recognized by human IgG1 in many non-allergic blood donors. To eliminate these residues, a Golgi-targeted Endo T from Hypocrea jecorina was expressed in seeds of an Arabidopsis GnTI mutant. The resulting recombinant activation associated secretory protein 1 (ASP1) glycoprotein produced carried single GlcNAc residues, showing that GlycoDelete can be used for other recombinant proteins not requiring complex N-glycans while removing immunogenic plant sugars (69). A successful example of N-glycan engineering in bacteria is the introduction of the Campylobacter jejuni N-glycosylation pathway into E. coli, enabling the production of glycoproteins bearing a heptasaccharide on D/E-X-N-X-S/T sequons (70).

Another approach to glycoengineering in P. pastoris is GlycoSwitch technology. The SuperMan5 strain -engineered to prevent hyperglycosylation and to shift the glycan profile toward Man5GlcNAc2- enabled methanol-independent production of an IgG Fc with a more homogeneous and size-defined glycosylation pattern. Although these glycans are not complex and do not correspond to the typical Fc glycosylation of human IgG1, their reduced heterogeneity may offer advantages from a production and quality control perspective, positioning this platform as a potentially safe and cost-effective alternative to mammalian cell culture for antibody manufacturing (71). A glycoengineered P. pastoris strain capable of producing fully complex and terminally sialylated N-glycans has been successfully used for the expression of functional erythropoietin, a glycoprotein whose efficacy and receptor affinity critically depend on its glycosylation profile (72).

Nonetheless, switching N-glycan types in a host requires careful consideration: deleting or introducing entire pathways may compromise genetic stability (73) and enzymes introduced to manipulate the glycosylation pathway may be deletereous on the host organism (70). Further challenges include the time-consuming optimization needed to ensure enzyme activity in the host environment and the difficulty achieving fully uniform N-glycan profiles (68).

3.3 Strategy C — post-expression deglycosylation: folding first, glycan removal later

Another strategy to modify an antigen’s N-glycosylation profile is to remove or modify glycans enzymatically. This approach relies on the observation that many antigens require glycans for proper folding but do not require them for immune presentation. By allowing N-glycans to assist protein folding and then eliminating them after purification, previously shielded conserved epitopes can be exposed and size heterogeneity eliminated. Following this rationale, the SARS-CoV-2 RBD was produced in P. pastoris with its two native N-glycosylation sites intact during expression, followed by enzymatic deglycosylation with Endo H after purification (74). The resulting deglycosylated antigen maintained structural integrity while presenting to the immune system or patient’s serum a homogeneous surface with a single GlcNAc remaining, thus avoiding the heterogeneity of yeast high-mannose glycans. This strategy has also been applied in plants, where RBD and the malaria antigen Pfs48/45 were produced in Nicotiana benthamiana co-expressing bacterial Endo H, enabling in vivo deglycosylation (75, 76). A similar approach was used for the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen (PA), a promising candidate for a cost-effective and immunogenic anthrax vaccine (77).

Although the post-expression deglycosylation strategy is useful to produce recombinant antigens in a low-cost scalable host system without non-mammalian glycosylation, several issues need to be evaluated. It is known that some deglycosylation enzymes, such as PNGase F, can remove complex glycans but also deamidates asparagine residues, potentially altering protein structure (77). In addition, certain antigens, as the APA complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis experience up to a ten-fold activity loss in eliciting delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions in guinea pigs immunized with BCG upon deglycosylation, indicating that their mannose residues may be necessary to maintain antigenic properties (78). Deglycosylated proteins may be more aggregation-prone, less thermally stable, and more susceptible to proteolysis (79), along with potential structural alterations (30). In addition, the manufacturing costs associated with the inclusion of a deglycosylation step should be taken into account.

3.4 Strategy D — changing glycosylation sites for masking and unmasking epitopes

Another approach involves adding or removing N-glycosylation sequons to reshape which regions of an antigen are targeted by the immune system. Glycan masking works by sterically shielding undesired, variable, or immunodominant epitopes, redirecting antibodies toward conserved or functionally important regions. Conversely, glycan unmasking reveals epitopes normally hidden during infection, enabling recognition of vulnerable structural features pathogens often conceal.

These strategies have been applied to several viral antigens. In HIV, N-glycans introduced in Env variants (eOD-GT8) focused immunity on the CD4 binding site (80). For Influenza H5N1, masking hypervariable HA regions broadened cross-clade neutralization (81, 82), with further gains when multiple masked immunogens were combined (83). Pairing head masking with stem-epitope unmasking also produced cross-clade protection in mice (81–84). Similar glycan-based immune-focusing approaches have been explored for Ebola glycoprotein (85) and SARS-CoV-2 RBD (46), highlighting the versatility of rational glycan design.

Epitope redirection via glycan masking and unmasking is not without risks. Adding N-glycans can induce conformational changes that destabilize the antigen or alter the native epitope architecture (86, 87). Removing glycans can reduce thermal stability, increase aggregation, or proteolytic susceptibility.

4 Discussion

Current glycoengineering strategies show that the key question in antigen design is not whether glycosylation is present, but when during biosynthesis it is required and for what function. Glycans often serve as essential biosynthetic elements that support folding and quality control, yet they may hinder immune recognition once the protein reaches its mature state. Our opinion is that glycosylation should be viewed as a tunable design parameter, necessary during glycoprotein biosynthesis but amenable to rational remodeling or removal in the final recombinant immunogen. This perspective shifts glycoengineering from merely replicating native viral glycosylation toward strategically redesigning it.

Within this framework, the choice of the expression systems and downstream processing becomes a deliberate design decision. The predictable glycosylation patterns of host cells enable the use of glycans as temporary folding aids while allowing controlled optimization of epitope exposure. Overall, effective vaccine design should rely on distinguishing when N-glycans are biologically essential and when they are immunologically dispensable.

Statements

Author contributions

SO: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. TI: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. MM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Salary support for CD and the fellowships of TIH and MAMS were provided by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) and/or Universidad de Buenos Aires. SO is supported by a fellowship from ANPCyT.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Check of some English grammar and spelling.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Andre FE Booy R Bock HL Clemens J Datta SK John TJ et al . Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ. (2008) 86:140–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.040089

2

Lembo A Molinaro A De Castro C Berti F Biagini M . Impact of glycosylation on viral vaccines. Carbohydr Polym. (2024) 342:122402. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122402

3

Orenstein WA Ahmed R . Simply put: Vaccination saves lives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2017) 114:4031–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704507114

4

Shattock AJ Johnson HC Sim SY Carter A Lambach P Hutubessy RCW et al . Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet. (2024) 403:2307–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00850-X

5

Rodrigues CMC Plotkin SA . Impact of vaccines; health, economic and social perspectives. Front Microbiol. (2020) 11:1526. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01526

6

Greenwood B . The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. (2014) 369:20130433. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0433

7

Bong C-L Brasher C Chikumba E McDougall R Mellin-Olsen J Enright A . The COVID-19 pandemic: effects on low- and middle-income countries. Anesth Analg. (2020) 131(1):86–92. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004846

8

Chen N . Income insecurity and social protection: Examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across income groups. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0310680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0310680

9

Shang Y Li H Zhang R . Effects of pandemic outbreak on economies: evidence from business history context. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:632043. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.632043

10

McConnell MJ Pachón J . Active and passive immunization against Acinetobacter baumannii using an inactivated whole cell vaccine. Vaccine. (2010) 29:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.052

11

Sugaya N Nerome K Ishida M Miyako K Mitamura Nirasawa M . Efficacy of inactivated vaccine in preventing antigenically drifted influenza type A and well-matched type B. JAMA. (1994) 272:1122–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520140052037

12

Innis BL Snitbhan R Kunasol P Laorakpongse T Poopatanakool W Kozik CA et al . Protection against hepatitis A by an inactivated vaccine. JAMA. (1994) 271:1328–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510410040030

13

D’Amico C Fontana F Cheng R Santos HA . Development of vaccine formulations: past, present, and future. Drug Deliv Transl Res. (2021) 11:353–72. doi: 10.1007/s13346-021-00924-7

14

Saito A Yamashita M . HIV-1 capsid variability: viral exploitation and evasion of capsid-binding molecules. Retrovirology. (2021) 18:32. doi: 10.1186/s12977-021-00577-x

15

Sánchez-Nava J Rodríguez MH Rodríguez-Aguilar ED . Inferring geographic spread of flaviviruses through analysis of hypervariable genomic regions. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2025) 10:277. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed10100277

16

Tohma K Ford-Siltz LA Kendra JA Parra GI . Manipulation of immunodominant variable epitopes of norovirus capsid protein elicited cross-blocking antibodies to different GII.4 variants despite the low potency of the polyclonal sera. J Virol. (2025) 99:e00611–25. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00611-25

17

Di Rienzo L Miotto M Desantis F Grassmann G Ruocco G Milanetti E . Dynamical changes of SARS-CoV-2 spike variants in the highly immunogenic regions impact the viral antibodies escaping. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinforma. (2023) 91:1116–29. doi: 10.1002/prot.26497

18

Hariharan V Kane RS . Glycosylation as a tool for rational vaccine design. Biotechnol Bioeng. (2020) 117:2556–70. doi: 10.1002/bit.27361

19

Tate MD Job ER Deng Y-M Gunalan V Maurer-Stroh S Reading PC . Playing hide and seek: how glycosylation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin can modulate the immune response to infection. Viruses. (2014) 6:1294–316. doi: 10.3390/v6031294

20

Feng T Zhang J Chen Z Pan W Chen Z Yan Y et al . Glycosylation of viral proteins: Implication in virus–host interaction and virulence. Virulence. (2022) 13:670–83. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2022.2060464

21

Chang J Block TM Guo J-T . Article commentary: viral resistance of MOGS-CDG patients implies a broad-spectrum strategy against acute virus infections. Antivir Ther. (2015) 20:257–9. doi: 10.3851/IMP2907

22

Sadat MA Moir S Chun TW Lusso P Kaplan G Wolfe L et al . Glycosylation, hypogammaglobulinemia, and resistance to viral infections. N Engl J Med. (2014) 370:1615–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302846

23

Jayaprakash NG Surolia A . Role of glycosylation in nucleating protein folding and stability. Biochem J. (2017) 474:2333–47. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170111

24

He M Zhou X Wang X . Glycosylation: mechanisms, biological functions and clinical implications. Signal Transduction Targeting Ther. (2024) 9:194. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01886-1

25

Tannous A Pisoni GB Hebert DN Molinari M . N-linked sugar-regulated protein folding and quality control in the ER. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2015) 41:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.12.001

26

Aebi M Bernasconi R Clerc S Molinari M . N-glycan structures: recognition and processing in the ER. Trends Biochem Sci. (2010) 35:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.10.001

27

Ferris SP Kodali VK Kaufman RJ . Glycoprotein folding and quality-control mechanisms in protein-folding diseases. Dis Model Mech. (2014) 7:331–41. doi: 10.1242/dmm.014589

28

Shin Y-J König-Beihammer J Vavra U Schwestka J Kienzl NF Klausberger M et al . N-glycosylation of the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain is important for functional expression in plants. Front Plant Sci. (2021) 12:689104. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.689104

29

Chen WH Du L Chag SM Ma C Tricoche N Tao X et al . Yeast-expressed recombinant protein of the receptor-binding domain in SARS-CoV spike protein with deglycosylated forms as a SARS vaccine candidate. Hum Vaccines Immunother. (2014) 10:648–58. doi: 10.4161/hv.27464

30

Lu Q Liao H Jiang Z Zhu Y Han Y Li L et al . Deglycosylation significantly affects the activity, stability and appropriate folding of recombinant Aspergillus Niger α-L-rhamnosidase expressed in Pichia pastoris. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 308:142531. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142531

31

Moharir A Peck SH Budden T Lee SY . The role of N-glycosylation in folding, trafficking, and functionality of lysosomal protein CLN5. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e74299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074299

32

Losev Y Frenkel-Pinter M Abu-Hussien M Viswanathan G Elyashiv-Revivo D Geries R et al . Differential effects of putative N-glycosylation sites in human Tau on Alzheimer’s disease-related neurodegeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2021) 78:2231–45. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03643-3

33

Chen S Qin R Mahal LK . Sweet systems: technologies for glycomic analysis and their integration into systems biology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. (2021) 56:301–20. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2021.1908953

34

Rudd PM Elliott T Cresswell P Wilson IA Dwek RA . Glycosylation and the immune system. Science. (2001) 291:2370–6. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2370

35

de Groot PWJ de Boer AD Cunningham J Dekker HL de Jong L Hellingwerf KJ et al . Proteomic analysis of candida albicans cell walls reveals covalently bound carbohydrate-active enzymes and adhesins. Eukaryot Cell. (2004) 3:955–65. doi: 10.1128/ec.3.4.955-965.2004

36

Grass S Buscher AZ Swords WE Apicella MA Barenkamp SJ Ozchlewski N et al . The Haemophilus influenzae HMW1 adhesin is glycosylated in a process that requires HMW1C and phosphoglucomutase, an enzyme involved in lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis. Mol Microbiol. (2003) 48:737–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03450.x

37

Singh RS Walia AK Kanwar JR . Protozoa lectins and their role in host–pathogen interactions. Biotechnol Adv. (2016) 34:1018–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bioteChadv.2016.06.002

38

Muenzner P Tchoupa AK Klauser B Brunner T Putze J Dobrindt U et al . Uropathogenic E. coli exploit CEA to promote colonization of the urogenital tract mucosa. PLoS Pathog. (2016) 12:e1005608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005608

39

Chen Y Chen J Wang H Shi J Wu K Liu S et al . HCV-induced miR-21 contributes to evasion of host immune system by targeting MyD88 and IRAK1. PLoS Pathog. (2013) 9:e1003248. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003248

40

Arthur JSC Ley SC . Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2013) 13:679–92. doi: 10.1038/nri3495

41

Goverse A Smant G . The activation and suppression of plant innate immunity by parasitic nematodes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. (2014) 52:243–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-050118

42

Hou S Zhang C Yang Y Wu D . Recent advances in plant immunity: recognition, signaling, response, and evolution. Biol Plant. (2013) 57:11–25. doi: 10.1007/s10535-012-0109-z

43

Li S Zhang L Yao Q Li L Dong N Rong J et al . Pathogen blocks host death receptor signalling by arginine GlcNAcylation of death domains. Nature. (2013) 501:242–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12436

44

Chen J Lin B Huang Q Hu L Zhuo K Liao J . A novel Meloidogyne graminicola effector, MgGPP, is secreted into host cells and undergoes glycosylation in concert with proteolysis to suppress plant defenses and promote parasitism. PLoS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006301. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006301

45

St Geme JW Falkow S Barenkamp SJ . High-molecular-weight proteins of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae mediate attachment to human epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (1993) 90:2875–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2875

46

Carnell GW Billmeier M Vishwanath S Suau Sans M Wein H George CL et al . Glycan masking of a non-neutralising epitope enhances neutralising antibodies targeting the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1118523. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1118523

47

Wilson IA Stanfield RL . 50 Years of structural immunology. J Biol Chem. (2021) 296:100745. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100745

48

Vossen MT Westerhout EM Söderberg-Nauclér C Wiertz EJ . Viral immune evasion: a masterpiece of evolution. Immunogenetics. (2002) 54:527–42. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0493-1

49

Martina CE Crowe JE Meiler J . Glycan masking in vaccine design: Targets, immunogens and applications. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1126034. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1126034

50

Pruett PS Air GM . Critical interactions in binding antibody NC41 to influenza N9 neuraminidase: Amino acid contacts on the antibody heavy chain. Biochemistry. (1998) 37:10660–70. doi: 10.1021/bi9802059

51

Stewart-Jones GBE Soto C Lemmin T Chuang GY Druz A Kong R et al . Trimeric HIV-1-Env structures define glycan shields from clades A, B, and G. Cell. (2016) 165:813–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.010

52

Seabright GE Doores KJ Burton DR Crispin M . Protein and glycan mimicry in HIV vaccine design. J Mol Biol. (2019) 431:2223–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.04.016

53

Deimel LP Xue X Sattentau QJ . Glycans in HIV-1 vaccine design – engaging the shield. Trends Microbiol. (2022) 30:866–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2022.02.004

54

Röltgen K Boyd SD . Antibody and B cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Cell Host Microbe. (2021) 29:1063–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.06.009

55

Watanabe Y Allen JD Wrapp D McLellan JS Crispin M . Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science. (2020) 369:330–3. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9983

56

Varki A . Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology. (2017) 27:3–49. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cww086

57

Kearns M Li M Williams AJ . Protein–glycan engineering in vaccine design: merging immune mechanisms with biotechnological innovation. Trends Biotechnol. (2025). doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2025.06.022

58

Varki A Cummings RD Aebi M Packer NH Seeberger PH Esko JD et al . Symbol nomenclature for graphical representations of glycans. Glycobiology. (2015) 25:1323–4. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv091

59

Goh JB Ng SK . Impact of host cell line choice on glycan profile. Crit Rev Biotechnol. (2018) 38:851–67. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1416577

60

Go EP Liao H-X Alam SM Hua D Haynes BF Desaire H . Characterization of host-cell line specific glycosylation profiles of early transmitted/founder HIV-1 gp120 envelope proteins. J Proteome Res. (2013) 12:1223–34. doi: 10.1021/pr300870t

61

Clausen H Wandall HH DeLisa MP Stanley P Schnaar RL . Glycosylation engineering, in: Essentials of Glycobiology (2022). Cold Spring Harbor (NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

62

Renner TM Stuible M Rossotti MA Rohani N Cepero-Donates Y . Modifying the glycosylation profile of SARS-CoV-2 spike-based subunit vaccines alters focusing of the humoral immune response in a mouse model. Commun Med. (2025) 5:111. doi: 10.1038/s43856-025-00830-w

63

Zhou Q Qiu H . The mechanistic impact of N-glycosylation on stability, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins. J Pharm Sci. (2019) 108:1366–77. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2018.11.029

64

Senra RL Pereira HS Schittino LMP Fontes PP de Oliveira TA Ribon AdOB et al . Co-expression of human sialyltransferase improves N-glycosylation in Leishmania tarentolae and optimizes the production of humanized therapeutic glycoprotein IFN-beta. J Biotechnol. (2024) 394:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2024.08.002

65

Eidenberger L Eminger F Castilho A Steinkellner H . Comparative analysis of plant transient expression vectors for targeted N-glycosylation. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2022) 10:1073455. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1073455

66

Laukens B De Wachter C Callewaert N . Engineering the pichia pastoris N-glycosylation pathway using the glycoSwitch technology. In: CastilhoA, editor. Glyco-Engineering: Methods and Protocols. Springer, New York, NY (2015). p. 103–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2760-9_8

67

Razdan S Wang J-C Barua S . PolyBall: A new adsorbent for the efficient removal of endotoxin from biopharmaceuticals. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:8867. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45402-w

68

Wang S Rong Y Wang Y Kong D Wang PG Chen M et al . Homogeneous production and characterization of recombinant N-GlcNAc-protein in Pichia pastoris. Microb Cell Factories. (2020) 19:7. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-1280-0

69

Piron R Santens F De Paepe A Depicker A Callewaert N . Using GlycoDelete to produce proteins lacking plant-specific N-glycan modification in seeds. Nat Biotechnol. (2015) 33:1135–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3359

70

Passmore IJ Faulds-Pain A Abouelhadid S Harrison MA Hall CL Hitchen P et al . A combinatorial DNA assembly approach to biosynthesis of N-linked glycans in E. coli. Glycobiology. (2023) 33:138–49. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwac082

71

Yang Y, Madden K, Sha M. Human IgG Fc Production Through Methanol-Free Pichia pastoris Fermentation. BioProcessing J. (2022) 21:1. Available online at: https://bioprocessingjournal.com/human-igg-fc-production-through-methanol-free-pichia-pastoris-fermentation/ (November 27, 2025).

72

Hamilton SR Davidson RC Sethuraman N Nett JH Jiang Y Rios S et al . Humanization of yeast to produce complex terminally sialylated glycoproteins. Science. (2006) 313:1441–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1130256

73

Laukens B De Visscher C Callewaert N . Engineering yeast for producing human glycoproteins: where are we now? Future Microbiol. (2015) 10:21–34. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.104

74

Idrovo-Hidalgo T Pignataro MF Bredeston LM Elias F Herrera MG Pavan MF et al . Deglycosylated RBD produced in Pichia pastoris as a low-cost sera COVID-19 diagnosis tool and a vaccine candidate. Glycobiology. (2024) 34:cwad089. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwad089

75

Mamedov T Yuksel D Ilgın M Gurbuzaslan I Gulec B Yetiskin H et al . Plant-produced glycosylated and in vivo deglycosylated receptor binding domain proteins of SARS-CoV-2 induce potent neutralizing responses in mice. Viruses. (2021) 13:1595. doi: 10.3390/v13081595

76

Mamedov T Cicek K Miura K Gulec B Akinci E Mammadova G et al . A Plant-Produced in vivo deglycosylated full-length Pfs48/45 as a Transmission-Blocking Vaccine Candidate against malaria. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:9868. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46375-6

77

Mamedov T Gun N Gulec B Khozeini H Ungor R Yuksel D et al . Immunogenicity and efficacy studies of Endo H in vivo deglycosylated Protective Antigen from Bacillus anthracis as a vaccine candidate against anthra. (2024). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3928112/v1

78

Romain F Horn C Pescher P Namane A Riviere M Puzo G et al . Deglycosylation of the 45/47-kilodalton antigen complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis decreases its capacity to elicit in vivo or in vitro cellular immune responses. Infect Immun. (1999) 67:5567–72. doi: 10.1128/IAI.67.11.5567-5572.1999

79

Zheng K Bantog C Bayer R . The impact of glycosylation on monoclonal antibody conformation and stability. mAbs. (2011) 3:568–76. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.6.17922

80

Duan H Chen X Boyington JC Cheng C Zhang Y Jafari AJ et al . Glycan masking focuses immune responses to the HIV-1 CD4-binding site and enhances elicitation of VRC01-class precursor antibodies. Immunity. (2018) 49:301–11.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.005

81

Lin S-C Lin Y-F Chong P Wu S-C . Broader neutralizing antibodies against H5N1 viruses using prime-boost immunization of hyperglycosylated hemagglutinin DNA and virus-like particles. PloS One. (2012) 7:e39075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039075

82

Lin S-C Liu W-C Jan J-T Wu S-C . Glycan masking of hemagglutinin for adenovirus vector and recombinant protein immunizations elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies against H5N1 avian influenza viruses. PloS One. (2014) 9:e92822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092822

83

Chen TH Liu WC Lin CY Liu CC Jan JT Spearman M et al . Glycan-masking hemagglutinin antigens from stable CHO cell clones for H5N1 avian influenza vaccine development. Biotechnol Bioeng. (2019) 116:598–609. doi: 10.1002/bit.26810

84

Chen T-H Yang Y-L Jan J-T Chen C-C Wu S-C . Site-specific glycan-masking/unmasking hemagglutinin antigen design to elicit broadly neutralizing and stem-binding antibodies against highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infections. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:692700. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.692700

85

Xu D Powell AE Utz A Sanyal M Do J Patten JJ et al . Design of universal Ebola virus vaccine candidates via immunofocusing. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2024) 121:e2316960121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2316960121

86

Ringe RP Pugach P Cottrell CA LaBranche CC Seabright GE Ketas TJ et al . Closing and opening holes in the glycan shield of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein SOSIP trimers can redirect the neutralizing antibody response to the newly unmasked epitopes. J Virol. (2019) 93:10.1128/jvi.01656–18. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01656-18

87

Thornlow DN Macintyre AN Oguin TH Karlsson AB Stover EL Lynch HE et al . Altering the immunogenicity of hemagglutinin immunogens by hyperglycosylation and disulfide stabilization. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:737973. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.737973

Summary

Keywords

antigen, glycoengineering, immunogenicity, N-glycosylation, protein folding, vaccine design

Citation

Orioli S, Idrovo-Hidalgo T, Martinez Saucedo MdlA and D’Alessio C (2026) Architects of folding, editors of immunity: the strategic use of N-glycans in vaccine design. Front. Immunol. 17:1766701. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2026.1766701

Received

12 December 2025

Revised

03 January 2026

Accepted

26 January 2026

Published

18 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Jose De La Fuente, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Reviewed by

Yves Durocher, National Research Council Canada (NRC), Canada

Cristina Elisa Martina, Vanderbilt University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Orioli, Idrovo-Hidalgo, Martinez Saucedo and D’Alessio.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cecilia D’Alessio, cdalessio@fbmc.fcen.uba.ar

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.