- Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Denver, Denver, CO, United States

Cardiovascular tissues exhibit complex mechanical behaviors that are nonlinear, anisotropic, and spatially heterogeneous. These local and regional variations play a critical role in disease initiation, progression, and treatment outcomes, yet conventional approaches often rely on specimen-averaged properties that overlook this heterogeneity. This review highlights recent advances in local mechanical characterization, spanning experimental methods, imaging-based assessments, and computational strategies. Traditional mechanical tests, such as uniaxial, biaxial, and indentation methods, remain foundational but assume uniform material properties. Surface-based techniques, particularly digital image correlation, now enable high-resolution full-field strain mapping in vitro and even intraoperatively, while volumetric approaches—including ultrasound, Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)—extend characterization to through-thickness and into in vivo settings. Digital volume correlation (DVC) further enhances these modalities by extracting three-dimensional internal displacement fields, though its use in cardiovascular tissues is still emerging. To translate these data into clinically relevant metrics, inverse methods such as the Virtual Fields Method (VFM) and inverse finite element analysis (iFEA) are used to estimate region-specific constitutive parameters. Emerging machine learning and physics-informed frameworks further accelerate model selection, parameter identification, and uncertainty quantification. Despite significant progress, major challenges remain in image quality in dynamic in vivo environments, uncertain boundary conditions, computational costs, and the lack of standardized protocols. Future progress will rely on integrating multimodal imaging, robust inverse modeling, and physics-informed machine learning into reproducible pipelines capable of generating patient-specific mechanical maps. Ultimately, local characterization holds the potential to transform risk prediction, medical device optimization, and personalized treatment planning in cardiovascular medicine.

1 Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Arnett et al., 2019; Vos et al., 2020; Timmis et al., 2022; Tsao et al., 2022), with outcomes often determined not only by systemic risk factors but also by local changes in tissue structure and mechanics. Understanding how regional variations in stiffness, strength, and remodeling drive disease initiation and progression is, therefore, essential for both mechanistic insight and clinical translation. Mechanical characterization is central to this effort (Zhang et al., 2002; Avril et al., 2010). While early studies often relied on simplified material models, a growing body of evidence shows that these tissues are spatially heterogeneous, anisotropic, and nonlinear (Davis et al., 2015; di Gioia et al., 2023). These observations motivate a shift from averaged properties to local material characterization, which captures region-specific mechanical behavior.

Conventional benchtop tests, such as uniaxial, biaxial, and indentation remain foundational for relating load and deformation to material response. Standard protocols typically assume near-uniform stress and strain in a central testing region and treat the specimen as materially homogeneous, i.e., a single parameter set (whether isotropic or anisotropic) applied specimen-wide. However, these assumptions are often violated in tissues with structural or compositional variability, leading to biased parameter estimates and reduced fidelity (Abbasi et al., 2016).

Advances in imaging have partially addressed these challenges by enabling full-field deformation measurements: digital image correlation (DIC) provides high-resolution surface strain maps in vitro and even intraoperatively (Hokka et al., 2015), while ultrasound, Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) yield volumetric geometry and wall motion assessment both in vitro and in vivo. Across these techniques, the central goal remains: to extract load-displacement data and identify constitutive models that accurately describe tissue behavior.

The need for local characterization is underscored by the marked spatial variability consistently revealed by full-field datasets, even within a single non-diseased specimen (Davis et al., 2015; di Gioia et al., 2023). This variability is further exacerbated by aging and disease. Aging alters collagen-elastin ratios, often leading to localized thickening and stiffening (Singam et al., 2020). Myocardial infarction leads to negative remodeling of the left ventricle, including regional wall thinning, dilation and impaired function (Nguyen et al., 2015). Similarly, localized pathological changes in blood vessels, such as in aortic dissection, can decrease effective wall thickness and increase stress (Weiss et al., 2022), while aneurysms can alter collagen and elastin cross linking leading to increased regional stiffness (Weiss et al., 2020; Cosentino et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2023).

These findings demonstrate that spatial variation is mechanistically informative and must be properly measured and modeled. Local characterization has yielded critical insights into understanding disease progression and guiding clinical decisions. For example, in atherosclerosis, spatially resolved mechanics help explain plaque initiation and progression (Brown et al., 2016). In aneurysms and dissections, local wall properties improve growth and rupture risk prediction beyond diameter-based criteria (Laurent et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2022; Baumler et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Similarly, localized material properties guide the design and durability assessment of medical devices, such as coronary stents, bioprosthetic valves, and mitral valve repair devices (Abbasi et al., 2016; Simonian et al., 2023; Ha et al., 2025). Furthermore, incorporating region-dependent properties also facilitates reconstruction of stress-free geometries, which are often unavailable in vivo (Mourato et al., 2024). This added spatial detail can better constrain zero-pressure reconstructions, by reducing the non-uniqueness of the prestress field—regional stiffness informs where prestress should accumulate, yielding more trustworthy stress, strain, and pressure estimates and, ultimately, more informed clinical decision-making (Weisbecker et al., 2014; Mourato et al., 2024).

Extracting these local material properties is enabled by a combination of full-field measurement and inverse approaches such as the Virtual Fields Method (VFM) and inverse finite element analysis (iFEA), which convert kinematic and load measurements into spatially varying parameters. Recently, machine learning has emerged as a complementary tool, streamlining constitutive model selection and parameter identification while handling the high-dimensional datasets produced by imaging (Linka and Kuhl, 2024). These developments are making local mechanical characterization increasingly practical in both research and clinical contexts.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of cardiovascular tissue characterization, with an emphasis on local material properties. We begin by summarizing experimental setups and imaging modalities that generate full-field data. We then examine constitutive models that capture the anisotropy, nonlinearity, and heterogeneity of cardiovascular tissues, before highlighting inverse approaches, including VFM, iFEA, and machine learning, that enable region-specific parameter estimation.

Together, we aim to demonstrate how local characterization links microstructure to cardiovascular mechanics, improves predictive modeling, and advances translation into cardiovascular diagnostics and interventions.

2 Mechanical testing for cardiovascular material characterization

A fundamental understanding of conventional mechanical testing methods is essential for anyone engaged in local material characterization, as most in vitro material characterization procedures are directly built upon these general mechanical testing methods. Among these, tensile (uniaxial and multiaxial) and indentation tests are the most commonly performed. The fundamental principle underlying these tests is to examine the relationship between applied force and resulting displacement, or vice versa. The data can be used to calculate stress and strain and could be further fitted into a constitutive model to describe the tissue’s mechanical behavior.

Since cardiovascular tissues are inherently viscoelastic, their initial loading curves are strongly influenced by time-dependent effects such as creep and hysteresis. To minimize these transient effects and improve reproducibility, preconditioning is typically applied prior to data collection (Fung, 1993). This process involves cyclic loading and unloading of the specimen, which helps the fibers reach a stabilized mechanical state, release residual stress, and reduce hysteresis and creep (Pena et al., 2018). With these considerations in mind, the following subsections review the most common conventional mechanical testing approaches used in cardiovascular tissue characterization.

2.1 Uniaxial

In uniaxial testing, specimens are typically prepared in a rectangular or dog-bone shape so that both ends can be securely gripped by the testing device (García-Herrera et al., 2016). To highlight tissue anisotropy, strips are usually excised along dominant fiber orientations. For example, cutting vessels in the axial and circumferential directions.

This method is among the most straightforward mechanical assessments and provides baseline tensile properties of soft tissues. However, it relies on simplifying assumptions, including material homogeneity, isotropy, and constant thickness throughout the specimen. While valuable for establishing fundamental tensile behavior, uniaxial testing does not capture the complex multiaxial loading conditions that cardiovascular tissues experience in vivo (Lane et al., 2024). In practice, limited tissue area—especially in small vessels and valve leaflets may restrict excision of strips in both circumferential and axial orientations (Tian et al., 2015; van Haaften et al., 2019). This limits assessment of anisotropy and can bias fitted parameters toward the tested direction(s).

2.2 Multiaxial

Early mechanical assessments of biological soft tissues are limited to uniaxial studies, with difficulty in multidimensional control. Given that cardiovascular tissues exhibit intrinsic anisotropy, uniaxial assessments alone fail to yield comprehensive data necessary for the estimation of a generalized strain energy function (Sacks and Sun, 2003). To address this limitation, tensile tests in multiple directions, collectively referred to as multiaxial tests, were developed. These include planar biaxial, tubular biaxial, triaxial and inflation-based methods.

Biaxial testing involves stretching the specimen in two directions (often orthogonal). The method of testing may vary based on how the specimen is shaped, allowing it to be performed in flat or tubular forms. Planar biaxial testing of biological tissues was first introduced by Lanir and Fung (1974) in rabbit skin and subsequently applied to cardiovascular tissues by Chew et al. (1986). In this method, a thin flat specimen is mounted onto a testing device, and loads are applied in both directions. By fitting constitutive models to the resulting bidirectional data, planar mechanical characteristics can be determined (Sacks, 2000). Square specimens are common in planar biaxial testing but are highly sensitive to mounting/clamping errors (Avanzini and Battini, 2016). As in uniaxial test, fidelity when using a square specimen depends on fiber alignment: even modest misalignment to the loading axes induces shear and can bias parameter estimation (Fehervary et al., 2018). Cruciform specimens are generally less sensitive to the edge effects because loads are transferred through the arms to the central test region, though the load delivered to the gauge area may differ from the force measured at the grips. Modified cruciform designs (e.g., slit arms) can improve load-transfer efficiency and increase biaxial uniformity in the central region (Avanzini and Battini, 2016).

Since blood vessels are inherently tubular, they are often tested in their native cylindrical form. Tubular biaxial testing, also known as the inflation-extension test, stretches tissues in the circumferential and axial directions simultaneously. In this setup, the applied load in the circumferential direction is generated by luminal pressure, which induces physiologically relevant stresses. Vito first developed a tubular biaxial setup in 1980 (Vito and Hickey, 1980), and this approach has since been widely used and advanced to characterize both healthy and diseased vessels (Gleason et al., 2004; Ferruzzi et al., 2013).

Despite their advantages, biaxial tests are not without limitations. Both planar and tubular methods assume uniform specimen thickness and uniform force distribution. In planar testing, accurate results are expected only in the central region, away from boundary effects (Nielsen et al., 1991). Furthermore, the clamping required for planar biaxial testing makes it unsuitable for failure analysis, as rupture rarely occurs within the gauge region. To address this, bulge inflation testing was introduced by Mohan and Melvin (1983) to evaluate failure mechanics in the descending aorta. In this approach, circular specimens are mounted and pressurized on one side, allowing the tissue to deform until rupture. Compared with planar biaxial tests, bulge inflation more closely replicates in vivo loading and reduces dependence on clamping artifacts (Cavinato et al., 2017). However, the classic circular-die bulge test produces near-equi-biaxial loading, which can limit parameter identifiability in highly anisotropic tissues. By contrast, planar biaxial testing permits arbitrary tension ratios to evaluate directional response. Recent work shows that employing an elliptical bulge die introduces controlled non-equi-biaxial stress states, improving the ability to capture anisotropic behavior (Gasparotti et al., 2023).

While biaxial and bulge tests provide critical data on tissue behavior, they are insufficient to fully characterize the mechanical properties of orthotropic materials such as myocardium (Sommer et al., 2015). Triaxial shear on small cuboidal samples captures shear and mixed-loading responses that biaxial tests miss. In myocardium, six simple-shear modes can be aligned with the fiber, sheet, and sheet-normal axes (Dokos et al., 2002). Pairing biaxial extension with triaxial shear in human myocardium produced the first comprehensive datasets capturing nonlinear, viscoelastic, direction-dependent behavior across orientations and showed that biaxial data alone may provide the wrong material symmetry class (Sommer et al., 2015). Building on this, Avazmohammadi et al. (2018) developed an integrated experimental-inverse modeling framework for post-infarct myocardium using triaxial testing, demonstrating that incorporating pure-shear modes (tension along one axis coupled with compression along another) improves parameter identifiability relative to using only simple-shear, thereby enhancing predictive performance (Avazmohammadi et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020).

2.3 Indentation and atomic force microscopy

Indentation testing is an alternative method for evaluating material behavior by correlating force with indentation depth (Cox et al., 2008). The method is grounded in Hertz contact theory, which assumes the material is elastic, homogeneous, and isotropic, with deformation considered infinitesimal and properties linearly elastic (Hertz, 1881). Among the earliest applications in cardiovascular biomechanics was Gow’s 1970s work on the mechanical properties of the vascular endothelium (Gow and Vaishnav, 1975). However, this approach alone is insufficient for cardiovascular tissues, which are typically anisotropic and hyperelastic.

Subsequent investigations have integrated indentation with other methods, such as equibiaxial stretch, to gain in-plane stress-strain relation of the myocardial wall (Halperin et al., 1987). Humphrey et al. (1991) found that the transverse stiffness is approximately linearly correlated with the in-plane stress in specific stretch ranges on the cardiac tissue, thereby rendering the indentation test a feasible method for assessing the regional material properties of an intact heart. More recently, indentation has been used to evaluate regional properties in the porcine left ventricle (Jehl et al., 2021) and aortic arch (Zhao et al., 2025), although many analyses still rely on simplified linear elastic models.

Like indentation, atomic force microscopy (AFM) employs Hertzian or extended contact theories, such as Johnson-Kendall-Roberts and Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov models, to evaluate material properties (Kim et al., 2025). AFM operates by scanning a nanometer-scale sharp tip across the specimen surface, applying forces in the nano-to microscale range, thereby enabling high-resolution mechanical characterization at the nanoscale. Gavara and Chadwick introduced a frequency-modulated AFM technique that allows contactless assessment of both elastic and viscous properties of soft tissues (Gavara and Chadwick, 2010). In this approach, the elastic modulus and viscosity are derived from the frequency-dependent phase lag between an oscillating microsphere and the driving piezo across different positions above the sample. Akhtar later demonstrated that frequency-modulated AFM could quantify regional variations in the mechanical properties of cardiovascular tissues, such as the aortic media layer (Akhtar et al., 2016). While AFM provides spatially resolved measurements with minimal sample preparation, its main drawback is the time required for data collection.

3 Imaging modalities for local tissue assessment: from surface to volume

Recent advances in imaging techniques enable high-frequency tracking of deformations within specimens, both on the surface and throughout the volume. The principle relies on monitoring full-field deformation through distributed trackable features, such as surface speckles, internal patterns, or other image-detectable markers. These features are captured in sequences of high-resolution images, and their displacements are analyzed in conjunction with applied force data.

Images from cameras and microscopes are highly practical for in vitro benchtop testing but are generally not feasible in vivo, where optical access is limited. In contrast, volumetric medical imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT, MRI, and OCT allow both in vivo and in vitro assessment of tissue kinematics.

Numerous studies have employed these approaches to investigate cardiovascular tissue behavior. In the following subsections, we review progress in both surface-based and volumetric imaging for deformation tracking, and highlight their roles in material characterization. By integrating imaging-based deformation fields with mechanical loading information, a comprehensive stress–strain relationship can be obtained. This approach supports not only global but also local estimation of material parameters, provided that appropriate constitutive models and inverse methods are employed.

3.1 Surface assessment

Digital Image Correlation (DIC) is a non-contact, image-based method that is straightforward to implement and readily compatible with standard benchtop tests. The setup typically consists of one or more high-speed cameras that record digital images during loading under controlled illumination. To achieve accurate correlation, specimens are coated with a randomly distributed speckle pattern with an ideal black-to-white ratio of ∼50:50 to enhance pattern recognition and improve displacement tracking accuracy (Palanca et al., 2015).

The method relies on comparing reference and deformed images of the specimen surface. Image subsets from the undeformed reference are tracked in the deformed state by converting discrete pixel intensities into continuous fields through interpolation (e.g., bilinear fitting). This enables sub-pixel displacement estimation and precise full-field strain calculations (Sutton et al., 1983).

Early charge-coupled device (CCD) systems limited vascular applications to low-frequency diameter tracking (∼10 Hz) due to constraints in storage and computation (Vito and Hickey, 1980). With the emergence of high-speed cameras, affordable computing power, and improved correlation algorithms, including seminal work by Peters and Ranson (1982), Sutton et al. (1983), Chu et al. (1985), Sutton et al. (1986), and Bruck et al. (1989), DIC expanded rapidly in the 2000s. Today, it is widely used to capture full-field deformation and to support accurate material characterization.

3.1.1 2D DIC

2D DIC is a powerful tool for measuring the full-field surface strain of planar specimens. As seen in Figure 1, a typical setup uses a single CCD camera to capture images of a specimen with a high-contrast speckle pattern applied to its surface (Pan et al., 2009). This technique is commonly paired with conventional mechanical tests. Researchers have used 2D DIC to assess changes in the diameter of diseased arteries during inflation tests (Beattie et al., 1998) and to obtain the full strain field of native vascular tissue during uniaxial testing (Zhou et al., 2016). It was also used to evaluate bovine aorta using uniaxial testing (Zhang et al., 2002). Planar biaxial tests are also frequently integrated with 2D DIC to evaluate the properties of heart valve and prosthetic valve materials (Abbasi et al., 2016; Parvin Nejad et al., 2024), as well as to determine regional variations in the material properties of blood vessels (Pena et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Schematic of the 2D DIC testing setup. A CCD camera records the deformation on a planar specimen by tracking randomly distributed speckle patterns.

Because 2D DIC only records the planar surface deformation, it has limited capability for predicting the three-dimensional (3D) behavior of materials, especially for highly anisotropic tissues. To overcome this limitation, hybrid strategies combine 2D DIC with out-of-plane measurements and offer a more comprehensive visualization of the specimen’s mechanics. For instance, surface DIC paired with indentation (via inverted confocal microscopy) provided complementary depth information for engineered tissues and atherosclerotic plaque (Cox et al., 2008; Chai et al., 2015). Another approach used a single-camera system that integrates fringe projection (which is radially sensitive) with 2D DIC, enabling simultaneous in-plane and apparent through-thickness deformation assessment in porcine myocardium (Genovese et al., 2015). A recent study paired 2D DIC with histology-derived fiber orientation, fiber content, and collagen undulation to build subject-specific micromechanical models and explore remodeling after myocardial infarction (Mendiola et al., 2024). These hybrid methods offer a more comprehensive visualization of the specimen’s mechanics using a single camera setup.

Despite its straightforward implementation, 2D DIC has distinct drawbacks that limit its applicability. The primary issue is its single-camera perspective, which assumes the specimen is perfectly planar and viewed perpendicularly. Even slight imperfect alignment or out-of-plane motion can introduce significant errors, as the system misinterprets 3D movement as in-plane deformation. This makes it unsuitable for complex or highly curved geometries, such as heart valves, and for anisotropic materials, where mechanical properties vary with direction (Abbasi et al., 2016). Ultimately, these limitations often render 2D DIC insufficient for accurately characterizing the complex, multi-axial behavior of cardiovascular tissues (Pan, 2018).

3.1.2 3D DIC

Three-dimensional digital image correlation (3D DIC), also known as stereo DIC, extends traditional 2D DIC by reconstructing the three-dimensional coordinates of each subset using images captured from two or more simultaneous camera views. The first binocular 3D DIC system was developed in 1993 by Luo et al. using two synchronized cameras positioned at different viewing angles (Luo et al., 1993). This configuration allows for accurate recovery of 3D surface geometry and deformation fields, making it particularly suitable for characterizing the biomechanical behavior of cardiovascular tissues such as blood vessels and heart valves.

3D DIC has been widely adopted in inflation-based studies to investigate the mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of vascular tissues. Early implementations beginning in the late 1990s utilized bulge inflation tests to assess vessel wall mechanics under biaxial loading conditions across human and animal vessels, revealing localized mechanical responses and rupture characteristics, as shown in Figure 2A (Hsu et al., 1995; Drexler et al., 2007; Drexler et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012; Romo et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2015; 2016; Duprey et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2016; Cavinato et al., 2019).

Figure 2. Schematic of the selected 3D DIC testing setup. A tubular specimen represents a blood vessel; alternative tissues (e.g., bioprosthetic valves or excised vessels for bulge-inflation) can also be tested (A) Binocular 3D DIC system. (B) Stereo DIC on a specimen immersed in an hydration bath. (C) Stereo DIC with controlled rotation for panoramic deformation data. (D) Single-camera pDIC using a conical-shape mirror; a rotating mirror adjusts the view. (E) Four-camera pDIC using mirrors and beam splitters. (F) Multi-biprism four-camera pDIC for immersed tissue testing.

At smaller scales, stereo DIC combined with microscopy has been used to resolve local deformation in small arteries like murine carotid arteries (Sutton et al., 2008; Ning et al., 2010). This combination enables non-contact, high-resolution strain measurements in small specimens, overcoming limitations of traditional contact-based methods.

More recently, 3D DIC has been employed to quantify leaflet strains in bioprosthetic heart valves under physiological pressure in a custom saline-bath apparatus (Figure 2B) (Abbasi et al., 2018). This setup allowed dynamic testing while preserving native tissue mechanics.

Capturing full-field strain on curved and complex geometries often requires multiple viewing angles. Techniques such as rotating the specimen or camera (Figure 2C) have been used to acquire sequential images from different perspectives. However, non-simultaneous image acquisition can introduce temporal noise and deformation drift, inspiring the development of alternative setups.

The conventional binocular 3D DIC requires two precisely synchronized high-speed cameras, increasing cost and setup complexity. To address this, single-camera systems have been developed to create a more compact and cost-effective testing environment. As shown in Figure 2D, these setups use a single camera with mirror-assisted optics (conical or flat) to simultaneously capture images from multiple angles, eliminating the need for camera synchronization.

One such setup is panoramic DIC (pDIC), which uses a 45° concave conical mirror to generate simultaneous multi-view images (Genovese, 2007). Initially applied with spherical markers to estimate anisotropic hyperplastic properties in arterial segments (Genovese, 2009; Avril et al., 2010), the system was later refined with random speckle patterns for improved accuracy and applicability to small vessels (Genovese et al., 2011b; Genovese et al., 2011a). Calibration procedures were also implemented to correct for refraction artifacts caused by sample immersion in physiological solutions.

The pDIC system has since been used to study healthy and diseased vessels in murine models (Genovese et al., 2012; Genovese et al., 2013; Bersi et al., 2016; Weiss et al., 2022), examining anisotropic hyperelastic properties across various vascular regions. It has also facilitated investigations into complex phenomena such as arterial tortuosity, where disruptions in elastic fiber integrity and collagen organization contribute to structural instability and local stiffening (Weiss et al., 2020).

Another single-camera 3D DIC method involves rotating the specimens to collect sequential images. This approach has been used to investigate residual strain and stress in intact, load-free excised arterial segments (Badel et al., 2012b). However, similar to the pDIC, this method is also susceptible to deformation drift between the views due to the viscoelastic nature of blood vessels.

Standard stereo 3D DIC acquires two simultaneous angled views but cannot provide 360° coverage. Mirror-assisted, single-camera pDIC can extend coverage, but balancing a wide field of view with sufficient pixel density and depth of field remains challenging, especially for small vessels. To address these issues, Genovese et al. developed two advanced systems. A four-camera pDIC system for small-scale arteries, extending the conical mirror-assisted setup with dynamic full-field measurement and refraction correction as shown in Figure 2E; and A multi-biprism DIC system (Figure 2F) for larger vessels, such as human arteries, where each camera views the specimen through a prismatic bath corner, generating two virtual views per camera and enabling 360° coverage without specimen rotation (Genovese et al., 2021).

While 3D DIC is highly beneficial for in vitro testing, its application for in vivo studies remains limited. While it has been demonstrated to have the potential to provide data on myocardial movement during surgery (Hokka et al., 2015), the results require improved contrast conditions for greater accuracy. Furthermore, as a surface assessment method, 3D DIC cannot capture strain and displacement throughout the tissue’s thickness, which restricts its ability to resolve transmural deformation. Future advancements may integrate multimodal imaging or tomographic techniques to reconstruct real-time, specimen-specific geometries with depth-resolved displacement fields.

3.2 Volume assessment

Volume assessment extends surface measurements into the tissue interior, enabling through-thickness characterization of deformation. This section reviews key volumetric imaging modalities -ultrasound, CT, MRI, and OCT-that provide 3D structural and motion data followed by digital volume correlation (DVC), a post-processing approach that is emerging in cardiovascular applications.

3.2.1 Ultrasound

Ultrasound has been widely used in clinical practice since the 1970s (Gennisson et al., 2013). The tissue 1D motion can be tracked with M (motion) mode or Tissue Doppler Imaging (TDI), which quantify vessel diameter changes during loading (Phillips et al., 2017; Ferruzzi et al., 2018; Wang and Lee, 2021). B (Brightness)-mode provides 2D cross-sections that can be stacked into 3D, and access to raw radio frequency (RF) data enables sub-pixel displacement tracking with micrometer precision (∼1–10 µm) (Hoskins and Kenwright, 2015).

In 4D ultrasound (3D ultrasound with time-resolved data), the speckle tracking method is used to track the tissue kinematics by following natural patterns in B-mode or RF data (Seo et al., 2009; Wittek et al., 2013; Wittek et al., 2016). These methods have quantified regional left ventricular strain to inform myocardial function during pharmacological and ischemic interventions (Seo et al., 2009). In large vessels, 4D ultrasound has been used to track aortic wall deformations at different ages and pathologies (Wittek et al., 2013; Wittek et al., 2016) and to also improve strain accuracy in carotid-like phantoms through ultrafast acquisitions (Fekkes et al., 2018). Motion tracking has also revealed that perivascular tethering allows central arteries to operate at lower wall stress/stiffness than often assumed (Ferruzzi et al., 2018). This has implications for interpreting in vivo vessel mechanics and designing physiologically relevant models.

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) provides high-resolution in vivo assessment using a rotating echo element at the catheter tip (Bom et al., 2000). Beyond geometry and volume assessments, IVUS can be extended to elastography, enabling stiffness mapping of regions of interest. This is achieved by correlating known forces with measured deformations. Ultrasound elastography is broadly categorized into quasi-static and dynamic approaches (Gennisson et al., 2013). Quasi-static (strain) methods map local strain between two loading states, e.g., diastole vs. systole, and was used to show that lipid plaques deform more than fibrous or calcified regions (Bom et al., 2000), and that healthy arterial regions are stiffer than atherosclerotic regions under both normotensive and hypertensive conditions (Vonesh et al., 1997; de Korte et al., 2000a). Dynamic elastography involves wave-based methods such as Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) and shear wave elastography. ARFI delivers focused acoustic pushes and measures axial displacement or shear wave speed. In carotid plaques, ARFI has identified soft lipid cores beneath stiff caps and low displacement in calcified regions, consistent with histological findings (Czernuszewicz et al., 2015). Shear/guided-wave elastography infers stiffness from wave speed and dispersion. In vivo carotid studies have shown pressure-driven variability in wave speed, enabling the recovery of arterial shear stiffness (Li et al., 2022). Similarly, intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) is a catheter-based ultrasound modality used for real-time anatomic visualization and guidance during electrophysiology and structural interventions. In vivo, ICE-based elastography, most commonly ARFI/myocardial elastography, has been used to visualize and monitor radiofrequency ablation lesions and to differentiate softer from stiffer atrial tissue (Eyerly et al., 2012; Bunting et al., 2018). As with IVUS, ICE elastography relates measured deformation to either focused acoustic impulses (dynamic) or differences between loading states (quasi-static), allowing local stiffness maps to be generated within the cardiac chambers. Practical considerations include catheter orientation and depth, limits on push amplitude for safety, and cardiac motion. Nonetheless, ICE offers intra-procedural, site-specific mechanical contrast that can guide substrate modification and, where needed, provide regional stiffness prior information for inverse modeling in patient-specific analyses. Together, IVUS and ICE extend elastography into the lumen and cardiac chambers, providing catheter-accessible, local mechanical maps complementary to external imaging modalities.

To surpass the diffraction limits of conventional ultrasound, super-resolution ultrasound (SR-US), often termed Ultrasound Localization Microscopy (ULM), enables sub-wavelength vascular imaging (Chen et al., 2021; van Sloun et al., 2021). ULM uses red-blood-cell–scale microbubble contrast and high-frame-rate acquisitions to localize and track individual bubbles across frames, fusing detections into microvascular maps and velocity fields (Yan et al., 2024). In practice, there is a three-way trade-off among localization precision, bubble concentration, and acquisition time: higher concentrations shorten scans but induce overlapping point-spread functions that confound single-bubble fitting (Chen et al., 2021; van Sloun et al., 2021). Clinically, acquisition times on the order of minutes are typically required to accumulate sufficient sparse localizations, and physiological motion degrades registration. Recent machine-learning–based ULM directly addresses high-density overlap and motion, reducing the required acquisition time while preserving super-resolution detail (van Sloun et al., 2021).

From a cardiovascular mechanics standpoint, ULM’s sub-wavelength vascular maps and flow vectors can (i) refine regional hemodynamic loads (e.g., microvascular perfusion patterns adjacent to plaques or infarct zones), (ii) improve boundary conditions for inverse modeling by anchoring local flow/pressure estimates, and (iii) support multiscale coupling between tissue stiffness maps and microvascular remodeling. Furthermore, super-resolved displacement/velocity fields can stabilize ultrasound elastography—e.g., by improving speckle tracking in regions with rapid decorrelation—thereby enhancing local stiffness estimation in vivo.

3.2.2 Computed tomography (CT)

CT reconstructs cross-sectional images from X-ray attenuation, reported in Hounsfield Units (HU). Clinical CT has been in routine use since the 1970s (Schulz et al., 2021), while micro-CT emerged in the 1980s for preclinical and research use (Hunter and Dewanckele, 2021). Micro-CT employs microfocus, enabling spatial resolution below 100 µm and down to tens of microns in vitro (Clark and Badea, 2021). ECG-gated CT has been used to extract cyclic strain and effective stiffness maps in vivo. For example, Celi et al. (2023) derived local arterial stiffness by tracking contour changes across the cardiac cycles and pairing with pressure data. In abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), regional strain and incremental modulus measurements revealed marked mechanical heterogeneity across the sac, and can be fed into patient-specific analyses of wall rupture risk (Tierney et al., 2012).

Micro-CT enables internal strain mapping in small animals and ex vivo tissues; when paired with tubular biaxial testing, it has been used to quantify regional strain in porcine veins (Gomez et al., 2014) and to visualize notch propagation in dissected carotid arteries (Brunet et al., 2020).

3.2.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI, or Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR), when applied to cardiovascular tissue, was introduced into clinical practice in the early 1980s (Kabasawa, 2022).

MRI is well-suited for visualizing internal soft tissue structures and kinematics because it leverages the nuclear magnetic resonance of water-rich hydrogen protons. While it avoids ionizing radiation, it typically has lower spatial resolution (1–2 mm in routine clinical use) than CT, but cine-MRI can achieve a higher temporal resolution (20–50 ms) (Golemati et al., 2019). Time-resolved cine-MRI is used in vivo to determine the spatial and temporal displacement field of tissues (Nederveen et al., 2014). Early work used this technique to report the strain field in the left ventricle during diastole (Veress et al., 2005). Similar techniques have also been applied to assess the stiffness of smaller-scale cardiovascular tissues, such as healthy human carotid arteries (Franquet et al., 2013). Analogous to ultrasound elastography, Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) uses externally generated shear waves and encodes tissue motion into the MR phase to estimate stiffness maps. MRE provides depth-independent, whole-organ stiffness measurements, though it requires longer acquisition times and access to specialized MRI hardware (Manduca et al., 2001; Khan et al., 2018). In cardiac applications, MRE has been used to map myocardial stiffness throughout the cardiac cycle. Studies in porcine models have shown strong correlations between MRE-derived stiffness and left ventricular loading conditions (Kolipaka et al., 2011). In clinical settings, elevated myocardial stiffness detected by MRE has been associated with diseases such as cardiac amyloidosis (Arani et al., 2017), and in abdominal aortic aneurysms lower wall stiffness measured via MRE has been linked to increased risk of aneurysm rupture events (Dong et al., 2022).

Contrast-enhanced MRI, particularly late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging, highlights myocardium with expanded extracellular space, differentiating viable from non-viable myocardium (Jenista et al., 2023). LGE delineates scar and infarct border zone that typically exhibits impaired regional mechanics (Mendiola et al., 2022). In non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, the presence and distribution of LGE associate with worse global and regional function, underscoring fibrosis-function coupling (Mėlinytė-Ankudavičė et al., 2022). For mechanics-oriented analyses, LGE maps can (i) define region-specific material classes (e.g., scar, border, remote) for constitutive modeling and (ii) inform patient-specific boundary/loading conditions when combined with cine or 4D-flow data.

While routine MRI maps structure and function at the organ scale, diffusion tensor MRI (DT-MRI/CMR) measures direction-dependent water diffusion to resolve fiber and sheetlet architecture in vivo. It quantifies myocardial microstructure and reveals dynamic sheetlet reorientation across the cardiac cycle in health and disease (Nielles-Vallespin et al., 2017). Recent work has tracked progressive microstructural remodeling across infarct, border, and remote zones post-MI, linking fiber disarray to regional dysfunction (Mendiola et al., 2025). For mechanics, DT-CMR provides orientation and dispersion priors that improve anisotropic constitutive models (e.g., HGO families), increase parameter identifiability, and reduce bias in stress/strain predictions compared with geometry-only fits.

Despite its strengths in vivo, in vitro MRI for mechanical testing is less common due to the high hardware costs and long scan times. One study obtained quasi-static pressure-strain data in porcine carotid arteries using an MRI-compatible chamber (Wang et al., 2025).

MRI scan time is often reduced by undersampling phase-encoding lines, but this degrades spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (Berggren et al., 2022). Recent deep learning–based super-resolution MRI (SR-MRI) methods can recover high-frequency details from accelerated, lower-resolution acquisitions, shortening scan duration while preserving anatomical fidelity (Vollbrecht et al., 2025). When coupled with learned denoising/reconstruction, SR-MRI further improves effective SNR and edge sharpness (Vollbrecht et al., 2024; Vollbrecht et al., 2025). The application of this technique could mitigate super-resolution artifacts in rapidly moving cardiac tissue (Mukherjee et al., 2025). Clinically, these approaches have enabled higher-quality fetal cardiac MRI for prenatal evaluation of congenital heart defects (Vollbrecht et al., 2025) and have been applied to murine hearts to reconstruct anatomy and quantify motion (Mukherjee et al., 2025).

From a cardiovascular mechanics perspective, SR-MRI can sharpen cine boundaries (reducing tracking error and improving strain estimates), refine 4D-flow velocities for more reliable wall-shear stress and pressure-gradient calculations, and enhance the phase SNR of MR elastography, stabilizing local stiffness maps. Because super-resolution relies on training-based assumptions, task-specific validation is essential. It can be done by enforcing physical consistency across frames, testing against phantoms or benchtop references, and reporting uncertainty so confidence limits carry through to constitutive parameters.

3.2.4 Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

OCT is often considered the optical analog of ultrasound. It uses low-coherence interferometry to measure light echo intensity and time delay, generating high-resolution cross-sectional images. A single A-scan captures one-dimensional information, while stacked A-scans (B-scans) provide two-dimensional data. Similarly, stacked B-scans can be used to construct the 3D tissue microstructure (Fujimoto and Swanson, 2016). Since the early 2000s OCT has been applied to cardiovascular tissues. OCT alone has provided pre- and post-loading images of human aortas for mechanical assessment (Rogowska et al., 2004), but its limited penetration depth (∼500 μm in tissue, compared to ∼2 mm wall thickness of human aorta) restricts standalone use in a wide range of deep-tissue imaging applications. Tissue clearing has been explored to address this limitation and extend tissue depth; however, clearing agents can alter tissue hydration and mechanical properties, potentially confounding biomechanical measurements (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020). As such, OCT is often combined with complementary techniques to capture both microstructure and mechanics.

3.2.5 Digital volume correlation (DVC)

DVC is a three-dimensional extension of DIC, sharing its core methodology of image-based displacement tracking. First developed in 1999 (Bay et al., 1999; Bay, 2008), DVC tracks 3D voxel subsets to recover full-field internal displacements within a volume, unlike DIC, which tracks 2D pixel subsets on a surface. Instead of external surface speckle patterns, this methodology uses the natural grayscale texture, which is derived from microstructural features within the volume. DVC relies on volumetric imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, and OCT to generate the high-resolution 3D datasets needed to calculate displacement and strain.

In cardiovascular biomechanics, OCT is often the imaging modality of choice for DVC due to its micrometer-scale resolution, high-speed acquisition, and intrinsic coherent speckle. Santamaría et al. combined OCT with DVC to map through-thickness strain distributions in porcine aorta under tensile loading, revealing layer-dependent mechanical inhomogeneities (Acosta Santamaría et al., 2018). This approach was later used to quantify chemoelastic strains induced by osmotic agents, demonstrating the sensitivity of arterial tissue mechanics to chemical environments (Acosta Santamaría et al., 2020). At smaller scales, Bersi et al. integrated pDIC for surface strain measurement with OCT-based DVC for volumetric strain mapping in a murine model of aortic dissection. This multimodal approach enabled the reconstruction of a complete 3D strain field across the vessel wall and intramural thrombus, revealing dramatic regional variations in stiffness and strain energy (Bersi et al., 2020).

DVC provides comprehensive, through-thickness strain data that supports local material properties assessment. It is particularly valuable for characterizing layered or heterogeneous tissues where surface-only measurements are insufficient. However, it remains less mature than DIC in cardiovascular applications, is computationally demanding, and highly dependent on the quality and resolution of volumetric imaging. As a result, its use in quantifying cardiovascular tissue mechanics is still limited.

3.3 Summary: surface and volume characterization

Mechanical testing and imaging methods converge into two complementary strategies for locally characterizing cardiovascular tissue mechanics: surface-based and volume-based approaches.

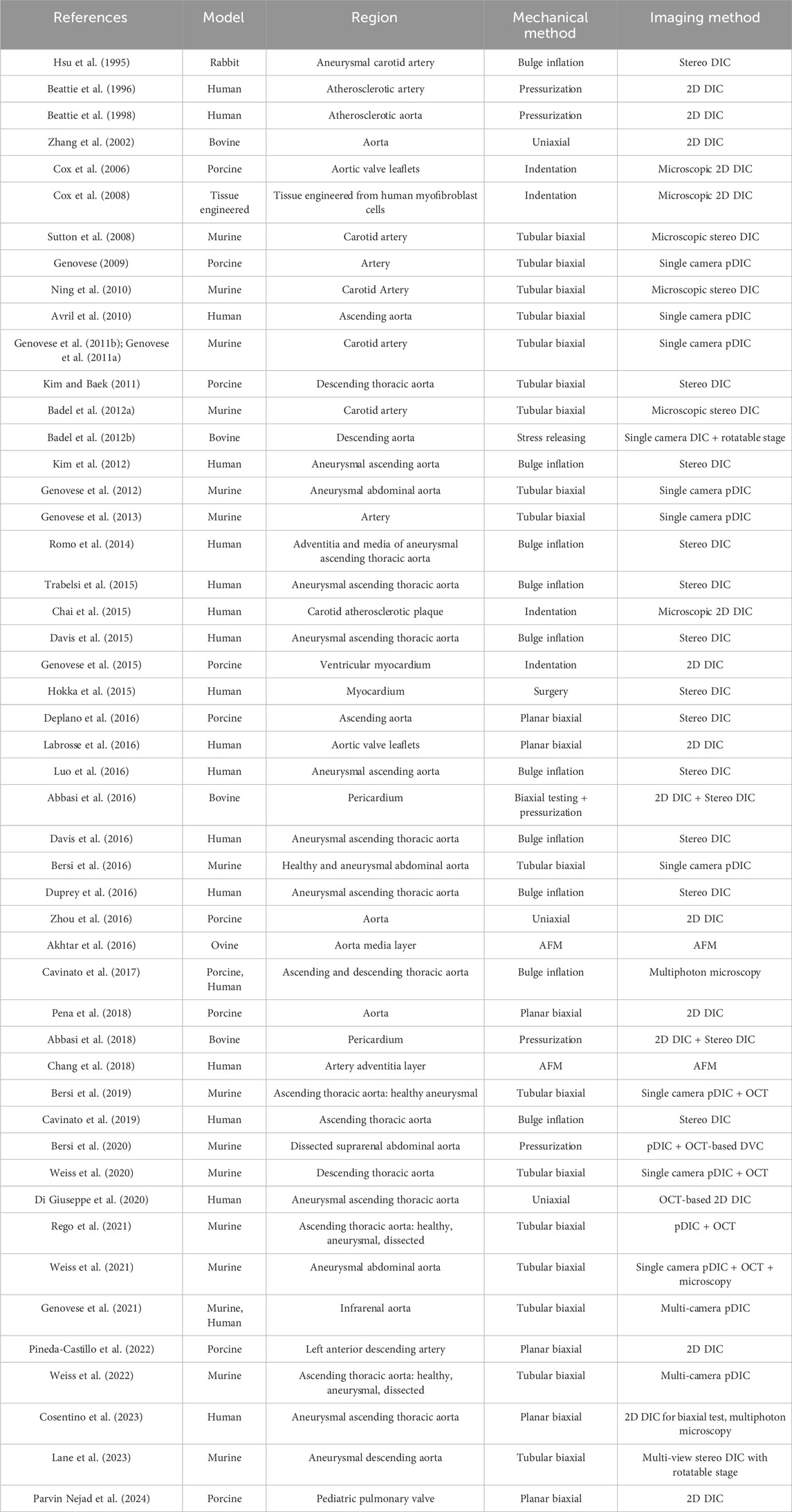

On the surface side, DIC remains one of the most widely used in vitro techniques for mapping specimen kinematics. With suitable optics, it has been applied to large vessels (e.g., human and porcine aorta) as well as small vessels (e.g., murine aorta) and can be coupled with microscopy for microscale analyses. When combined with tubular biaxial testing, the most common protocol for vessels—DIC resolves full-field deformation under physiologic loading. At finer scales, AFM enables direct measurement of micromechanical properties at the fiber or lamellar level. The breadth of surface-based studies, ranging from organ-scale DIC to microstructural AFM, is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies investigated cardiovascular tissue mechanical behavior with surface-based approaches.

In contrast, volume characterization relies on three-dimensional imaging modalities, including ultrasound, IVUS, CT, MRI, and OCT. These tools, many of which are clinically accessible, dominate in vivo assessments by capturing through-wall or volumetric deformation fields. DVC has been used as a post-processing strategy that extracts 3D displacement and strain maps from these volumetric datasets. Applications of these volume-based approaches in cardiovascular tissue mechanics are listed in Table 2, while their generalized processing steps are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Schematic of volumetric data acquisition. Cross-sectional data are obtained using the probe or instrument. The data can then be used to reconstruct the specimen-specific geometry.

Together, surface methods deliver high-resolution local strain fields where optical access or direct contact is feasible, whereas volume methods recover full 3D or through-thickness deformation fields at the organ level. This sets the foundation for the next section, where measured kinematics are linked to material parameter estimation through inverse approaches.

4 Material properties characterization

The previous sections highlighted advances in methods for obtaining displacement/strain, stress maps. While these data provide valuable insights into tissue mechanics, predicting behavior beyond specific test conditions requires generalized constitutive models. Well-defined and validated models enable the prediction of disease progression, support prevention strategies, and guide medical device design and optimization. This section reviews approaches for translating experimental results into constitutive models.

4.1 Linear and isotropic material models

Early material characterization studies often employed simple material assumptions—such as isotropic, incompressible, and homogeneous—to identify an optimal elastic modulus using linear Hookean or bilinear elastic models (Peters and Ranson, 1982; Vonesh et al., 1997; Beattie et al., 1998). Some studies applied this approach to regions of interest, such as assigning distinct linear elastic properties to fibrous and calcified plaque regions (Beattie et al., 1998). Combining indentation with full-field methods like DIC (Cox et al., 2008) or using a multi-region testing strategy (Jehl et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2025) can enhance the outcome, but the core limitation remains. While linear elastic properties are sometimes used in complex computational studies, such as Fluid-Solid Interactions (FSI), to reduce computational cost (Yilin et al., 2025), the Hookean law fundamentally fails to capture the nonlinear stiffening (hyperelasticity) of soft biological tissues, necessitating the use of more complex material models.

4.2 Isotropic hyperelastic models

Hyperelastic material models are governed by a strain energy function W, which describes the stored energy per unit volume as a function of strain. The neo-Hookean model is a simple, isotropic hyperelastic model and is commonly used when the ground substance matrix is the dominant component. It is governed by the following equation:

where µ is the shear-like modulus, κ is the bulk modulus, and

The Mooney-Rivlin model incorporates an additional term, enhancing the neo-Hookean model’s flexibility to improve the accuracy of isotropic hyperelastic materials. It is given by the Equation 2,

where

The Ogden material model is an alternative approach that offers enhanced control over the fitting curve using principal stretches (Ogden, 1972). However, since cardiovascular tissues (especially arteries and myocardium) are highly anisotropic and dominated by fibers orientation, simple isotropic Ogden forms often underperform compared with fiber-reinforced, structure-based models (e.g., the Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden family) that capture collagen fiber directions and dispersion (Holzapfel et al., 2000; Gasser et al., 2006; Holzapfel, 2006).

4.3 Viscoelasticity

Cardiovascular tissues exhibit time- and rate-dependent behavior, including relaxation during dwells, creep under sustained pressure, and hysteresis across cycles (Righi and Balbi, 2021). Two model families are common. Quasi-linear viscoelasticity (QLV) combines a nonlinear elastic law with a reduced relaxation function (Fung, 1993) and generalized Maxwell/Prony formulations, which introduce internal variables and time constants at finite strain (Fung, 1993; Nekouzadeh et al., 2007; Righi and Balbi, 2021). Anisotropic viscoelasticity further allows distinct relaxation along fiber, sheet, and cross-fiber directions (LeBar et al., 2024). Although viscoelasticity is well-documented experimentally in cardiovascular tissues, it is used less frequently in constitutive fitting, in part due to the complexity of coupling nonlinear anisotropy with viscous terms and the absence of simple, standardized frameworks (Nordsletten et al., 2021). When the loading protocol involves pronounced rate effects or cycle-to-cycle hysteresis, incorporating viscoelasticity can improve fit quality, reduce bias in hyperelastic parameters, and better match in vivo dynamics.

4.4 Anisotropic models

Histology and imaging show that cardiovascular tissues are reinforced by load-bearing collagen fibers embedded in elastin-rich matrix with proteoglycans and smooth muscle cells. Fibers form one or more families with preferred orientations and finite dispersion (Sosnovik et al., 2009; Wagenseil and Mecham, 2009; Cocciolone et al., 2018). This 3D architecture drives direction-dependent, recruitment-driven stiffening, underpinning the tissues’ nonlinear anisotropic behavior (Fung, 1993; Gasser et al., 2006; Chen and Kassab, 2016).

In vitro, fiber directions and dispersion can be quantified by histology, polarized light microscopy or second-harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy (label-free collagen mapping) (Ferruzzi et al., 2011a; Sommer et al., 2015; Cavinato et al., 2021; Torun et al., 2023; Mendiola et al., 2024). Through-thickness architecture can be assessed with OCT or micro-CT in suitably prepared specimens (Gomez et al., 2014; Acosta Santamaría et al., 2020). In vivo, DT-CMR provides ventricular fiber/sheet orientations and dispersion (Nielles-Vallespin et al., 2017), while intravascular OCT can offer near-surface orientation in arterial walls when co-registered to geometry (Narayanan et al., 2021).

For anisotropic laws, the mean fiber angle(s) and dispersion directly parameterize stiffness directions and convexity, improving parameter identification and reducing bias relative to geometry-only fits (Mendiola et al., 2024). Orientation constraints stabilize inverse problems, enable layer- or region-specific properties, and support remodeling analyses in which fiber orientation is allowed to evolve over time (Mendiola et al., 2025). Practically, using measured fiber angle/dispersion tightens bounds on anisotropic models and improves predictions of stress/strain maps, failure initiation, and device–tissue interactions (Torun et al., 2023).

4.4.1 Phenomenological anisotropic

Phenomenological models reproduce observed stress–strain behavior without explicitly incorporating microstructure; their parameters are descriptive rather than microstructurally interpretable (Holzapfel et al., 2004).

The collagen-recruitment–driven stiffening of cardiovascular tissues motivates exponential forms. Fung (Fung, 1993) introduced an exponential strain-energy function to capture this behavior, later generalized to 3D by Humphrey (Humphrey, 1995), which is shown in Equation 3:

where c is a stress-like parameter, D is the compressibility parameter, and

Fung-type model has been applied to pericardium (Abbasi et al., 2016), myocardium (Nikou et al., 2016), and arterial wall (Guo et al., 2024). Its primary advantages are flexibility and good fits across common loading paths; however, the inclusion of the mixed terms b which involves normal and shear strain components, significantly increases the number of parameters required.

4.4.2 Structurally-informed anisotropic

Structure-based laws capture features of tissue architecture (fiber families, dispersion, orientation), yielding parameters with biological meaning and more accurately represent anisotropy and its development across loading conditions (Sacks, 2003; Gasser et al., 2006).

Motivated by the microstructural organization of collagen fiber families in vessels, the Holzapfel-Gasser-Ogden (HGO) structure-based model was developed by Holzapfel et al. (2000) to incorporate a neo-Hookean term for the ground substance and an additional exponential term for the collagen fiber contributions. The generalized form can be written as:

where

To capture more complex microstructures, a Four-Fiber Family material model was introduced to describe collagen fibers aligned in the circumferential, axial, and two diagonal directions (Ferruzzi et al., 2011b; Ferruzzi et al., 2013). Its incompressible strain energy function is:

where

Similar to the four-fiber family model shown in Equation 5, Bersi (Bersi et al., 2016) incorporated the mass fractions of each fiber family to describe the stored energy in each constituent. It can be expressed in Equation 6:

where

4.5 Inverse and emerging machine learning approaches

While material properties can be directly derived from local strain-stress curves, measurement noise and uncertain boundary conditions often affect the results. Optimal design of experiments (ODoE) mitigates this by tailoring loading paths and sampling schemes to maximize information content and reduce parameter covariance (Lanir et al., 1996; Avazmohammadi et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020). In planar biaxial testing, adding an equibiaxial step to off-axis uniaxial paths at ±22.5°, together with non-uniform sampling concentrated near higher strain levels, tightens confidence bounds and improves conditioning (Lanir et al., 1996). Extending to 3D myocardium, mixed triaxial protocols that combine simple shear with pure shear improves the optimality metrics compared to all-simple-shear designs and enhance parameter identifiability (Avazmohammadi et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020). In practice, pre-selecting informative loading paths can substantially sharpen subsequent inverse identification; however, broad adoption remains limited by tooling constraints (hardware and control) and tissue heterogeneity, so many studies proceed without formal ODoE despite its benefits (Li et al., 2020). To obtain more robust, generalized material parameters across loads and geometries, inverse approaches are typically employed, with the most common being the VFM and iFEA.

VFM is a fast modeling technique to derive material parameters from full-field measurements (Avril et al., 2010). It is based on a weak formulation of equilibrium for every kinematically admissible (KA) virtual displacement

Where,

While conceptually simple, solving this complex problem directly for nonlinear models using Equation 7 is often impractical (Fabrice Pierron, 2012). Bersi et al. used an iterative VFM process to determine four-fiber family parameters for murine aortas by minimizing a cost function that matched predicted loads with experimental data (Bersi et al., 2016). Although VFM provides a quick estimation of the material parameters, it is highly sensitive to load uncertainty and model nonlinearity.

iFEA uses iterative finite element simulations to optimize constitutive model parameters. It starts with an initial guess, runs a forward FE simulation, and then minimizes a defined cost function by matching the simulated deformation/load response to the experimental full-field or selected region measurements (Abbasi et al., 2016). The iteration loop is accelerated by choosing an appropriate optimization algorithm and parameter bounds.

iFEA is effective when accurate geometry and boundary conditions are simultaneously obtained during experimental testing. Despite its high computational cost, this approach can robustly recover material parameters that precisely describe complex geometry, material models, and boundary conditions. Workflow charts, Figures 4, 5, illustrate the general procedures of VFM and iFEM, respectively, while Table 3 summarizes a list of studies that fit the experimental data into various material models.

Figure 4. VFM workflow for local cardiovascular tissue characterization. Full-field measurements and loads are combined with selected virtual fields; enforcing the virtual work principle to recover material parameters (iterated as needed for nonlinear laws), producing spatial maps.

Figure 5. iFEA workflow for local cardiovascular tissue characterization. Imaging and mechanical tests define geometry, boundary conditions, and full-field measurements; an FE model with a chosen constitutive model is iteratively fit to minimize the cost function, yielding load-free geometry and material parameter maps.

Table 3. Selected studies from 2015 to 2025 that used inverse method including the test setup, material model, inverse approaches, and cost function target. The material region is defined as follows: Bulk uses a universal material model and parameters applied to the entire specimen. Pointwise defines the material model and parameters for each point. Region-specific assigns a unique material model to each region.

Conventional VFM and iFEA require a pre-selected constitutive law and well-defined boundary conditions, which can be challenging for anisotropic, nonlinear, and heterogeneous soft tissues. Emerging machine learning (ML) approaches can address these challenges by learning constitutive structure from data and embedding physics constraints during training. Complementary to these model-learning strategies, statistical surrogates can also make inverse identification practical at scale. Gaussian process emulators (GPEs) act as surrogate models for expensive forward FE analyses, mapping parameters to pressures, diameters, or strain fields at significantly lower computational cost. They support global sensitivity analysis and history matching to screen parameters and narrow the feasible space before final calibration, while providing predictive means and variances for basic uncertainty quantification (Strocchi et al., 2025). In practice, GPEs could integrate with iFEA/VFM pipelines to accelerate regional or pointwise identification and can be used within Bayesian calibration or adaptive sampling. Supervised methods, such as a Constitutive Artificial Neural Network (CANN), can learn the energy function directly from stress-strain data (Linka and Kuhl, 2023). These methods can produce compact, closed-form models that remain physically reasonable and can be used directly in FE simulations (Linka and Kuhl, 2024; Martonová et al., 2024).

Unsupervised methods, such as a weak-form approach, can leverage full-field deformation data and a VFM-like loss function to characterize materials without requiring local stress labels (Meng et al., 2025). Finite-element–based neural network (FE–NN) surrogates further reduce computational cost by replacing repeated forward simulations in the inverse loop, learning the mapping from parameters/boundary conditions to displacements and strains (Zhang et al., 2022). These new methods can not only capture direction-dependent stiffness by using strain invariants (Linka and Kuhl, 2024) but also handle heterogeneous materials by interpolating local behaviors within a single model (Shi et al., 2025).

Overall, ML approaches can directly determine an appropriate material model from the data itself, while still producing physically meaningful and interpretable parameters. This has the potential to shorten the path from benchtop testing to simulation-ready setups and make clinical implementation more feasible. Table 4 summarizes selected studies that use machine learning approaches for material characterization.

5 Challenges and future directions

Despite significant advances in experimental techniques and computational frameworks, localized mechanical assessment of cardiovascular tissues remains far from routine clinical use. This gap is critical because many cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction and aortic dissection, originate from localized structural and mechanical abnormalities. Accurate clinical decision-making, therefore, requires data that reflect the specific mechanical environment of the affected region rather than global or averaged properties. For example, myocardial infarction results in regional extracellular matrix degradation, which drives adverse remodeling and functional deterioration (Nguyen et al., 2015; Romito et al., 2017). Similarly, aortic dissection typically initiates from confined defects within the medial layer (Humphrey, 2012; Rolf-Pissarczyk et al., 2021).

There is a growing convergence between studies of local microstructure and local mechanics. In a murine model of abdominal aortic aneurysm, compromised elastic fiber integrity and altered matrix cross-linking were associated with regional wall weakening and accelerated enlargement, highlighting the link between microstructural failure and macroscopic growth (Weiss et al., 2021). In AngII-induced thoracic aortopathy, evolving mural defects and dilatation coincided with localized biomechanical dysfunction and collagen/elastic fiber remodeling, reinforcing the value of co-mapped structural and mechanical metrics for site-specific risk assessment (Weiss et al., 2022). In carotid plaque, co-mapping collagen architecture with local failure mechanics revealed higher local stretch at rupture initiation (Torun et al., 2023). In the porcine left anterior descending artery, load-dependent microstructural realignment was observed (Pineda-Castillo et al., 2022). In ascending thoracic aorta, regional microstructural maps have been linked to biaxial response (Vignali et al., 2020). Yet a standardized, co-registered pipeline—common region of interest (ROI) grid/coordinates, synchronized imaging and mechanics, and uncertainty carried into inversion—is still missing, limiting structurally informed modeling and patient-specific prediction.

Surface-based approaches, such as DIC, indentation, and AFM, deliver high-resolution local mechanical data. Yet, their deployment in clinical environments faces restrictions imposed by both technological and biological challenges. DIC requires optical access, stable speckle patterns, and robust motion compensation—conditions that are difficult to achieve in vivo (Hokka et al., 2015). Indentation and AFM provide microscale stiffness maps (Chang et al., 2018), but face challenges related to sterility, accessibility, and acquisition time. Moreover, these methods often rely on simplified linear-elastic assumptions, which may fail to capture the nonlinear and anisotropic behavior of cardiovascular tissues (Kim et al., 2025).

A broader limitation of surface-only methods is their inability to resolve transmural heterogeneity, which is especially relevant in thick tissues like myocardium and aorta. Integrating surface and through-wall measurements, or combining imaging with mechanical testing, offers a promising strategy to overcome this limitation (Bersi et al., 2019; Rego et al., 2021).

Volumetric imaging modalities—including ultrasound, IVUS, CT, MRI, and OCT—extend mechanical characterization into the tissue interior. However, each modality presents trade-offs. CT excels at detecting calcifications and luminal geometry but lacks soft-tissue contrast and involves ionizing radiation (Trabelsi et al., 2016; Clark and Badea, 2021). MRI provides excellent soft-tissue contrast but is limited by long acquisition times and restricted accessibility (Franquet et al., 2013). Ultrasound is portable and widely used, yet suffers from speckle decorrelation and limited penetration depth (Gennisson et al., 2013). IVUS offers high spatial and temporal resolution but is invasive (Wang et al., 2022), while OCT provides exceptional near-surface resolution but shallow penetration. Across all modalities, co-registration and motion compensation remain major challenges, as do the reliable definition of in vivo boundary and loading conditions.

Opening-angle studies in arteries and myocardial residual-strain measurements show that the unloaded configuration is pre-strained (residual stress) (Chuong and Fung, 1986; Omens and Fung, 1990). In vivo geometry is also pre-stressed by physiological pressure. Accordingly, inverse analyses should reconcile the in-vivo geometry with a compatible zero-pressure (stress-free) state to obtain a realistic stress prediction and unbiased parameters (Weisbecker et al., 2014). Practical strategies include estimating a stress-free reference via iterative prestressing and enforcing equilibrium across pressure states. Without this step, fitted models can incorrectly attribute residual/pre-stress to constitutive stiffness, biasing stress distributions and reducing predictive accuracy.

Inverse modeling approaches, such as the VFM and iFEA, enable the estimation of constitutive parameters from experimental or imaging data. However, these methods face several barriers: lack of standardized initialization protocols, uncertainty in prestress and boundary conditions, and high computational cost, particularly in iFEA (Bersi et al., 2019; Genovese et al., 2021). Recovering load-free geometries from in vivo imaging remains a persistent challenge.

Recent advances in physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and weak-form learning offer promising solutions. These methods embed governing equations directly into the training process, reducing sensitivity to noise and incomplete boundary data (Linka and Kuhl, 2023; Caforio et al., 2024; Flaschel et al., 2025). When combined with Bayesian optimization and uncertainty quantification, these frameworks enhance robustness and interpretability, paving the way for clinically viable modeling pipelines (Tuo and Wang, 2022).

Looking ahead, several future priorities are evident. First, moving from bulk to regional, and ultimately pointwise, mapping is essential for capturing heterogeneity. This will require coordinated surface and volumetric acquisitions, supported by imaging-compatible test apparatus. Second, explicitly linking local microstructure (fiber angle/dispersion, density) to local mechanics should become routine practice, using shared ROI grids, a common coordinate frame, and co-registered imaging-mechanics pipelines. Third, intraoperative translation of surface methods such as DIC will depend on reliable speckling, motion compensation, and simplified calibration. Fourth, in vivo protocols must standardize strategies for reconstructing load-free geometries and anchoring hemodynamics to measured pressures and flows rather than generic assumptions. Finally, machine learning should serve as an accelerator, enabling rapid extraction of constitutive parameters under imperfect boundary conditions and facilitating patient-specific modeling. These advances could enable mechanics-informed biomarkers for rupture risk stratification, device optimization, and surgical planning, ultimately integrating mechanical data into personalized cardiovascular care.

In summary, a clear trend is emerging toward local analysis of cardiovascular tissues, enabling spatially resolved insights into mechanobiology and disease progression. While current methods yield increasingly detailed in vitro maps, precise pointwise estimates in vivo remain limited by boundary condition uncertainties, motion artifacts, and computational barriers. Clinical translation will hinge on three pillars: (i) standardized imaging and testing protocols that ensure reproducibility across centers, (ii) robust co-registration and motion compensation to deliver credible regional maps, and (iii) validated inverse or machine learning-assisted modeling pipelines that balance fidelity with interpretability.

Physics-informed machine learning represents a particularly promising bridge, accelerating the path from raw imaging data to clinically usable constitutive models while preserving physical meaning. With these elements in place, local mechanical mapping can evolve from an experimental tool into a decision-making asset, guiding rupture risk prediction, tailoring medical device design, and supporting longitudinal monitoring. Ultimately, the convergence of advanced imaging, computational mechanics, and machine learning has the potential to transform cardiovascular medicine by embedding local biomechanics directly into clinical workflows.

Author contributions

DQ: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. DW: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, M., Barakat, M. S., Vahidkhah, K., and Azadani, A. N. (2016). Characterization of three-dimensional anisotropic heart valve tissue mechanical properties using inverse finite element analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 62, 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.04.031

Abbasi, M., Qiu, D., Behnam, Y., Dvir, D., Clary, C., and Azadani, A. N. (2018). High resolution three-dimensional strain mapping of bioprosthetic heart valves using digital image correlation. J. Biomech. 76, 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.05.020

Acosta Santamaría, V. A., Garcia, M. F., Molimard, J., and Avril, S. (2018). Three-dimensional full-field strain measurements across a whole porcine aorta subjected to tensile loading using optical coherence tomography–digital volume correlation. Front. Mech. Eng. 4, 3. doi:10.3389/fmech.2018.00003

Acosta Santamaría, V. A., Garcia, M. F., Molimard, J., and Avril, S. (2020). Characterization of chemoelastic effects in arteries using digital volume correlation and optical coherence tomography. Acta Biomater. 102, 127–137. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2019.11.049

Akhtar, R., Graham, H. K., Derby, B., Sherratt, M. J., Trafford, A. W., Chadwick, R. S., et al. (2016). Frequency-modulated atomic force microscopy localises viscoelastic remodelling in the ageing sheep aorta. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 64, 10–17. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.07.018

Akyildiz, A. C., Hansen, H. H., Nieuwstadt, H. A., Speelman, L., De Korte, C. L., van der Steen, A. F., et al. (2016). A framework for local mechanical characterization of atherosclerotic plaques: combination of ultrasound displacement imaging and inverse finite element analysis. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 44 (4), 968–979. doi:10.1007/s10439-015-1410-8

Arani, A., Arunachalam, S. P., Chang, I. C. Y., Baffour, F., Rossman, P. J., Glaser, K. J., et al. (2017). Cardiac MR elastography for quantitative assessment of elevated myocardial stiffness in cardiac amyloidosis. J. Magnetic Reson. Imaging 46 (5), 1361–1367. doi:10.1002/jmri.25678

Arnett, D. K., Blumenthal, R. S., Albert, M. A., Buroker, A. B., Goldberger, Z. D., Hahn, E. J., et al. (2019). 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice Guidelines. Circulation 140 (11), e596–e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

Avanzini, A., and Battini, D. (2016). Integrated experimental and numerical comparison of different approaches for planar biaxial testing of a hyperelastic material. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 1–12. doi:10.1155/2016/6014129

Avazmohammadi, R., Li, D. S., Leahy, T., Shih, E., Soares, J. S., Gorman, J. H., et al. (2018). An integrated inverse model-experimental approach to determine soft tissue three-dimensional constitutive parameters: application to post-infarcted myocardium. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 17 (1), 31–53. doi:10.1007/s10237-017-0943-1

Avril, S., Badel, P., and Duprey, A. (2010). Anisotropic and hyperelastic identification of in vitro human arteries from full-field optical measurements. J. Biomech. 43 (15), 2978–2985. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.07.004

Badel, P., Avril, S., Lessner, S., and Sutton, M. (2012a). Mechanical identification of layer-specific properties of mouse carotid arteries using 3D-DIC and a hyperelastic anisotropic constitutive model. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin 15 (1), 37–48. doi:10.1080/10255842.2011.586945

Badel, P., Genovese, K., and Avril, S. (2012b). 3D residual stress field in arteries: novel inverse method based on optical full-field measurements. Strain 48 (6), 528–538. doi:10.1111/str.12008

Baumler, K., Rolf-Pissarczyk, M., Schussnig, R., Fries, T. P., Mistelbauer, G., Pfaller, M. R., et al. (2025). Assessment of aortic dissection remodeling with patient-specific fluid-structure interaction models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 72 (3), 953–964. doi:10.1109/TBME.2024.3480362

Bay, B. K. (2008). Methods and applications of digital volume correlation. J. Strain Analysis Eng. Des. 43 (8), 745–760. doi:10.1243/03093247jsa436

Bay, B. K., Smith, T. S., Fyhrie, D. P., and Saad, M. (1999). Digital volume correlation: Three-dimensional strain mapping using X-ray tomography. Exp. Mech. 39 (3), 217–226. doi:10.1007/Bf02323555

Beattie, D. K., Vito, R. P., Xu, C., and Glagov, S. (1996). “Measurement of the strain field in heterogeneous, diseased human aorta,” in Proceedings of the 1996 fifteenth Southern biomedical engineering conference, 103–105.

Beattie, D., Xu, C., Vito, R., Glagov, S., and Whang, M. C. (1998). Mechanical analysis of heterogeneous, atherosclerotic human aorta. J. Biomech. Eng. 120 (5), 602–607. doi:10.1115/1.2834750

Berggren, K., Ryd, D., Heiberg, E., Aletras, A. H., and Hedstrom, E. (2022). Super-Resolution cine image enhancement for fetal cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 56 (1), 223–231. doi:10.1002/jmri.27956

Berggren, C. C., Jack Wang, Y. F., Sigler, A. M. F., and Timmins, L. H. (2025). Focal comparison of experimental and finite element derived strain fields in a 3D IVUS-based computational model of vascular tissue under loading. J. Biomech. 187, 112689. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2025.112689

Bersi, M. R., Bellini, C., Di Achille, P., Humphrey, J. D., Genovese, K., and Avril, S. (2016). Novel methodology for characterizing regional variations in the material properties of Murine aortas. J. Biomech. Eng. 138 (7), 071005–07100515. doi:10.1115/1.4033674