Abstract

Four new species of Agaricales from China viz. Hohenbuehelia tomentosa, Rhodophana qinghaiensis, Rhodophana aershanensis, and Spodocybe tomentosum are described based on their unique morphological features and molecular evidence. Hohenbuehelia tomentosa is mainly characterized by its dark brown pileus with finely dense pure white tomentum, dirty white, decurrent lamellae, eccentric stipe, smooth spores, and fusiform metuloid cystidia. The characteristics of Rhodophana qinghaiensis are glabrous, smooth, reddish-brown pileus, gray-orange lamellae, and initially light orange becoming reddish brown stipe. The unique morphological characteristics of Rhodophana aershanensis are reddish brown pileus with age, brown-orange toward the margin, light orange lamellae and stipe dark brown at first, and reddish-brown with age. Spodocybe tomentosum is characterized by subclitocyboid and small basidiomes, finely dense pure white tomentum on the pileus surface, and broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid and smaller basidiospores. Phylogenetic analysis showed that Hohenbuehelia tomentosa, Rhodophana qinghaiensis, Rhodophana aershanensis, and Spodocybe tomentosum formed an independent lineage. Full descriptions, illustrations, and phylogenetic trees of the four new species are provided in this study.

1. Introduction

In recent years, many new species have been reported in China. For example, Liu et al. (2010) published three new records in China [Hohenbuehelia angustata (Berk.), Singer., H. nigra (Schwein.) Singer., and H. grisea (Peck) Singer.]. Similarly, Yang and Fan (2020) published a new species (Rhodophana guandishanensis L. Fan and C. Yang.) and He and Yang (2021) published two new species [Spodocybe bispora Z. M. He and Zhu L. Yang., S. rugosiceps Z. M. He and Zhu L. Yang.], all in China. This article introduces four new species from H. tomentosa, R. qinghaiensis, R. aershanensis, and S. tomentosum.

The Agaricales is the largest and most diverse order of mushroom-forming Basidiomycota, including Crepidotus (Fr.) Staude. (Kumar et al., 2018), Clavaria P. Micheli. (Yan et al., 2020), Hohenbuehelia Schulzer. (Kirk et al., 2001), Rhodophana Kühner. (Daniëls et al., 2017), Spodocybe Z. M. He & Zhu L. Yang. (He and Yang, 2021). Hohenbuehelia Schulzer. is nematophagous, has 135 valid records in Index Fungorum, and is distributed across Canada, Austria, the US, and China (Liu et al., 2010; Consiglio et al., 2018). Hohenbuehelia was established and first described by Schulzer von Müggenburg et al. (1866) and belongs to Pleurotaceae Kühner., Agaricales Underw. (Kirk et al., 2001). It is mainly characterized by spathulate, reniform, or flabelliform pileus, usually with a gelatinous layer under the surface of the pileus, with decurrent lamellae, diminished or no stipe, ellipsoid basidiospores, and thick-walled cystidia. In earlier studies, the genus Hohenbuehelia was placed under the genus Pleurotus (Fr.) P. Kumm. due to the similar pileus shape (conchiform) (Pilát and Veselý, 1935). However, the results of phylogenetic analyses based on 25S rDNA indicated that Hohenbuehelia differs from Pleurotus and exists as a monophyletic genus in Pleurotaceae (Thorn et al., 2000). Mentrida (2016) also proposed that Hohenbuehelia and Pleurotus could be distinguished from each other by the presence of a gelatinous layer between the context and the cuticle (present in the Hohenbuehelia species, but not in the Pleurotus). The asexual stage was separately described in the anamorph genus Nematoctonus Drechsler. (Drechsler, 1941; Thorn and Barron, 1986). Based on the phylogenetic analyses of ITS + nrLSU sequences, Nematoctonus and Hohenbuehelia are currently considered different (Koziak et al., 2007). According to the naming rules for fungi adopted in Melbourne in 2011 (Taylor, 2011), all members of the genus should therefore be referred to as Hohenbuehelia (Thorn, 2013). However, as more and more species are described in Hohenbuehelia, different researchers have inconsistent views on the infrageneric classification.

Rhodophana is a genus that was defined from Entolomataceae Kotl & Pouzar in 2014 (Kluting et al., 2014) and distributed in Canada, Argentina, Australia, the US, and China (Yang and Fan, 2020). The genus was first established by Kühner with R. nitellina (Fr.) T. J. Baroni & Bergemann. as the type species (Kühner, 1947). At the time, it was not effectively published until Kühner redescribed it in 1971, during which it was described as a Rhodocybe subgenus (Kühner and Lamoure, 1971). In 2014, based on phylogenetic analysis, Kühner found that it belonged to an independent branch, so it was repositioned as a genus. According to the current research, it was predicted that there will be many new combinations of this genus (Buyck et al., 2021). The morphological characteristics of this genus are mainly the collybioid basidiocarps, adnexed to adnate lamellae, and basidiospores with undulate-pustulate ornamentation, which is observed in the direction of the polar view of the angle, and more or less clamp connection. Since its establishment, there are 19 records in Index Fungorum, of which 15 are valid records, distributed in Europe [Spain and France] (Vizzini et al., 2012; Buyck et al., 2021), Asia [India and China] (Raj et al., 2016; Yang and Fan, 2020), and Canary Island of Africa (Vizzini et al., 2011).

Currently, Spodocybe is distributed in China and Europe (He and Yang, 2021; Vizzini et al., 2021). Spodocybe has the characteristics of saprophytic life, usually gregarious or caespitose on the ground of coniferous or coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest and distributed in temperate and subtropical zones from June to November. Lodge et al. (2014) revised the agaric family Hygrophoraceae Lotsy. while retaining the Cuphophylloid rank in the family Hygrophoraceae as the basis for the composition of Cuphophyllus (Donk) Bon., Ampulloclitocybe Redhead, Lutzoni, Moncalvo & Vilgalys. and Cantharocybe H. E. Bigelow & A. H. Sm.e. (Matheny et al., 2006; Binder et al., 2010; Lodge et al., 2014). However, the taxonomic problems of these three genera remained unresolved due to weak phylogenetic support. In 2021, Spodocybe was established as a new genus by He and Yang (2021) and placed in the new subfamily, Cuphophylloideae Z. M. He & Zhu L. Yang., which consists of Spodocybe, Ampulloclitocybe, Cantharocybe, and Cuphophyllus. Spodocybe is mainly characterized by clitocyboid basidiomes, decurrent lamellae, inamyloid basidiospores, lamellar trama subregular, and the presence of clamps connections. According to the Index Fungorum, Spodocybe contains six species, namely S. bispora, S. collina (Velen.) Vizzini, P. Alvarado & Dima, S. fontqueri (R. Heim) Vizzini, P. Alvarado & Dima., S. herbarum (Romagn.) Vizzini, P. Alvarado & Dima., S. rugosiceps, and S. trulliformis (Fr.) Vizzini, P. Alvarado & Dima.

The present study aims to describe four new species viz. H. tomentosa, R. qinghaiensis, R. aershanensis, and S. tomentosum.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Specimen collection

All the specimens were collected from China. The collected samples were dried overnight using an electric drying oven at 45°C and deposited in the Herbarium Mycology of Jilin Agricultural Science and Technology University (HMJU).

2.2. Morphological analysis of specimens

The macromorphological descriptions were based on field notes and photographs captured in the field. Images of the samples were taken in natural light using a Canon camera and tripod. The color card described by Kornerup and Wanscher (1978) was used. The micromorphology of the specimens was studied under an Olympus BX 53 (Tokyo, Japan) light microscope at 40, 100, 400, 600, and 1,000 × magnifications. All measurements were observed under a 1,000 × oil immersion. Sections of the dried specimens were mounted in 3% KOH, Melzer's reagent, Congo red, and Cotton blue for observations. Cotton blue and iron acetocarmine solutions were utilized to highlight the siderophilous granulation in the basidia following the study of Baroni (1981).

Basidiospore measurements were made by photographing all spores from time to time (taken from dry specimens) and measured via Cellsens Standard. The spore dimensions excluded the hilar appendix and the ornamentation and are given as (minimum–) average minus standard deviation—average plus standard deviation (–maximum) of length × (minimum–) average minus standard deviation—average plus standard deviation (–maximum) of width. Factor Q is the ratio of spore length to width, and Qm is the average of factor Q. When calculating the average, the maximum and minimum values are discarded. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) procedure was the one followed by Xu et al. (2019).

2.3. DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the dried samples following the procedure described by Zhao et al. (2011). For the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, primer pair ITS1 and ITS4 (White et al., 1990) were used for the internal transcribed spacer (ITS). Primer LR0R was paired with LR5 and LR7 (Vilgalys and Hester, 1990) to obtain sequences for the nuclear ribosomal large subunit (nrLSU). Primer pairs 5F and 7.1R (Matheny, 2005) and RhoF1 and RhoR1 (Kluting et al., 2014) were used for the DNA-directed RNA polymerase II second largest subunit 2 (rpb2). Primers ATP6-1 and ATP6-2 (Kretzer and Bruns, 1999) were used for the ATP synthase subunit 6 (atp6) and primers 526F and 1567R (Matheny et al., 2007), and 595F (Wendland and Kothe, 1997) and Efgr (Rehner and Buckley, 2005) were used for the translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1-α). The reaction program is shown in Table 1. The PCR products were examined on a 1% agarose gel detected by a JY 600 electrophoresis apparatus (Beijing JUNYI Electrophoresis Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and then sent to BGI Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for sequencing.

Table 1

| Species name | Sequence name | Primer pair | PCR amplification condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hohenbuehelia tomentosa | ITS | ITS1/ITS4 | 94°C 4 min 94°C 1min 56°C 1 min 72°C 1 min 72°C 5 min |

40 cycles |

| nrLSU | LROR/LR7 | 94°C 4 min 94°C 90 s 56°C 45 s 72°C 90 s 72°C 5 min |

40 cycles | |

| Rhodophana qinghaiensis | rpb2 | RhoF1/RhoR1 | 95°C 3 min 94°C 30 s 58°C 60 s 72°C 90 s 72°C 8 min |

35 cycles |

| tef1-α | EF1-526F/EF1-1567R | 94°C 3 min 94°C 30 s 52°C 30 s 72°C 30 s 72°C 3 min |

33 cycles | |

| Rhodophana aershanensis | atp6 | ATP6-3/6r | 95°C 5 min 95°C 30 s 42°C 2 min 72°C 1 min 72°C 10 min |

33 cycles |

| nrLSU | LROR/LR7 | 94°C 4 min 94°C 30 s 46°C 45 s 72°C 40 s 72°C 4 min |

30 cycles | |

| tef1-α | EF1-595F/EF1-Efgr | 94°C 3 min 94°C 30 s 54°C 30 s 72°C 1 min 72°C 10 min |

32 cycles | |

| Spodocybe tomentosum | ITS | ITS1/ITS4 | 94°C 5 min 94°C 30 s 52°C 30 s 72°C 30 s 72°C 5 min |

33 cycles |

| nrLSU | LROR/LR5 | 94°C 5 min 94°C 30 s 52°C 30 s 72°C 50 s 72°C 10 min |

35 cycles | |

| rpb2 | RPB2-5F/RPB2-7.1R | 94°C 5 min 94°C 40 s 52.5°C 45 s 72°C 40 s 72°C 10 min |

32 cycles | |

| atp6 | ATP6-1/2 | 94°C 5 min 94°C 40 s 52.5°C 45 s 72°C 40 s 72°C 10 min |

32 cycles |

List of PCR used in this study.

2.4. Phylogenetic analyses

The newly obtained sequences were compared with representative ITS, rpb2, nrLSU, atp6, and tef1-α sequences retrieved from GenBank. According to the phylogenetic analysis, we selected Pleurotus ostreatus as an outgroup in Figure 1, Mycena aff. pura, Panellus stipticus, Catathelasma imperiale, Tricholoma aurantium, and Tricholoma flavovirens as outgroups in Figure 2, and Macrotyphula juncea, Macrotyphula phacorrhiza, and Phyllotopsis sp. as outgroups in Figure 3 (Raj et al., 2016; Daniëls et al., 2017). The sequences were aligned with MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013) and then manually adjusted in Mega (Sudhir et al., 2016). The selection of the model was completed by ModelFinder based on the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). Mapping and analyzing the phylogenetic position of the new species was done using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The ML was calculated using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al., 2015), and the BI phylogeny was inferenced by MrBayes 3.2.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012). The ML tree was evaluated by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates (Stamatakis, 2006). A 50% majority-rule consensus cladogram was computed from the trees to obtain estimates for Bayesian posterior probabilities. The significance threshold was set to >0.95 for Bayesian posterior probability (PP) and >70% for ML bootstrap proportions (BP). All the sequences used in this study are listed in Table 2.

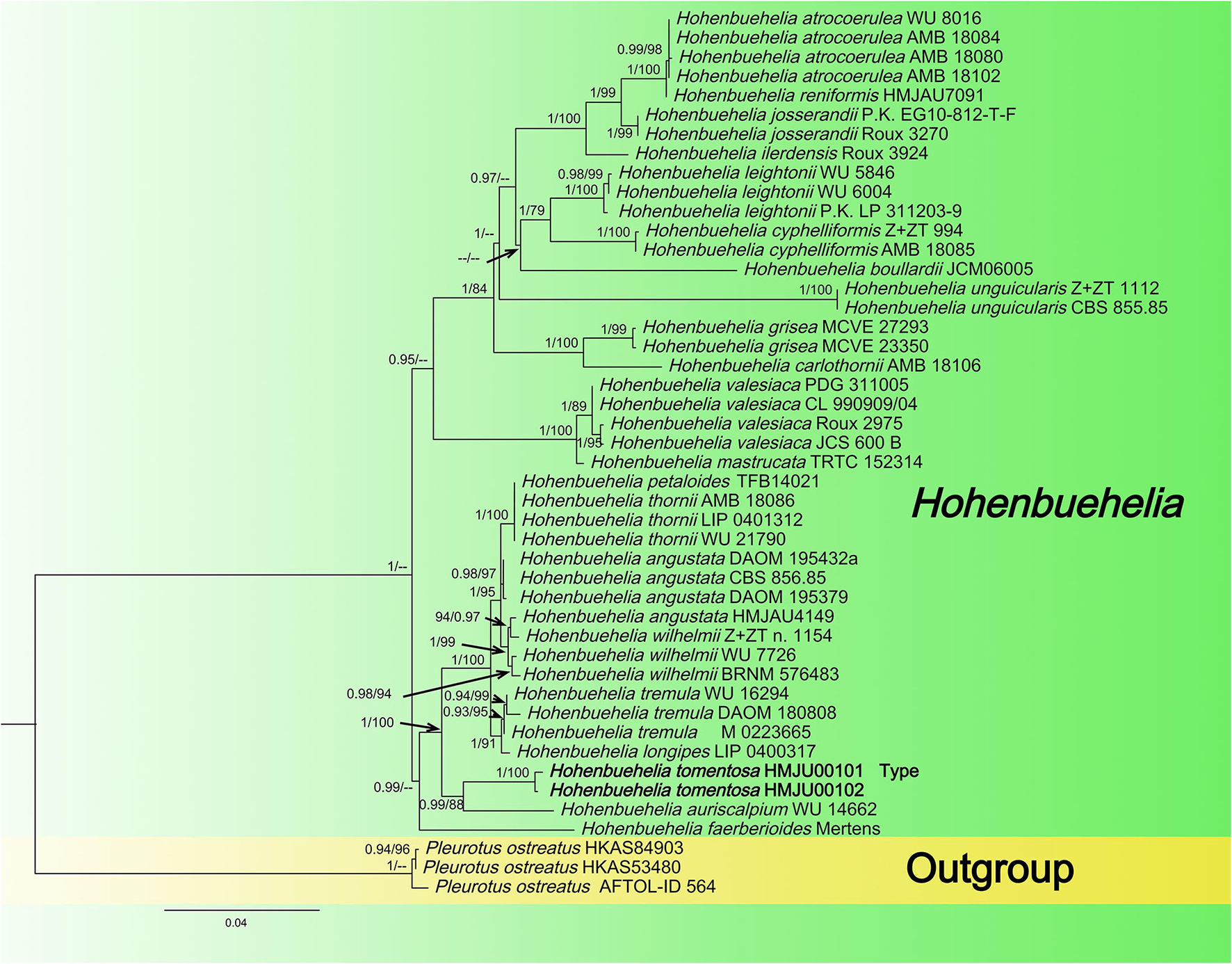

Figure 1

Maximum likelihood tree based on analyses of the ITS and nrLSU sequence data.

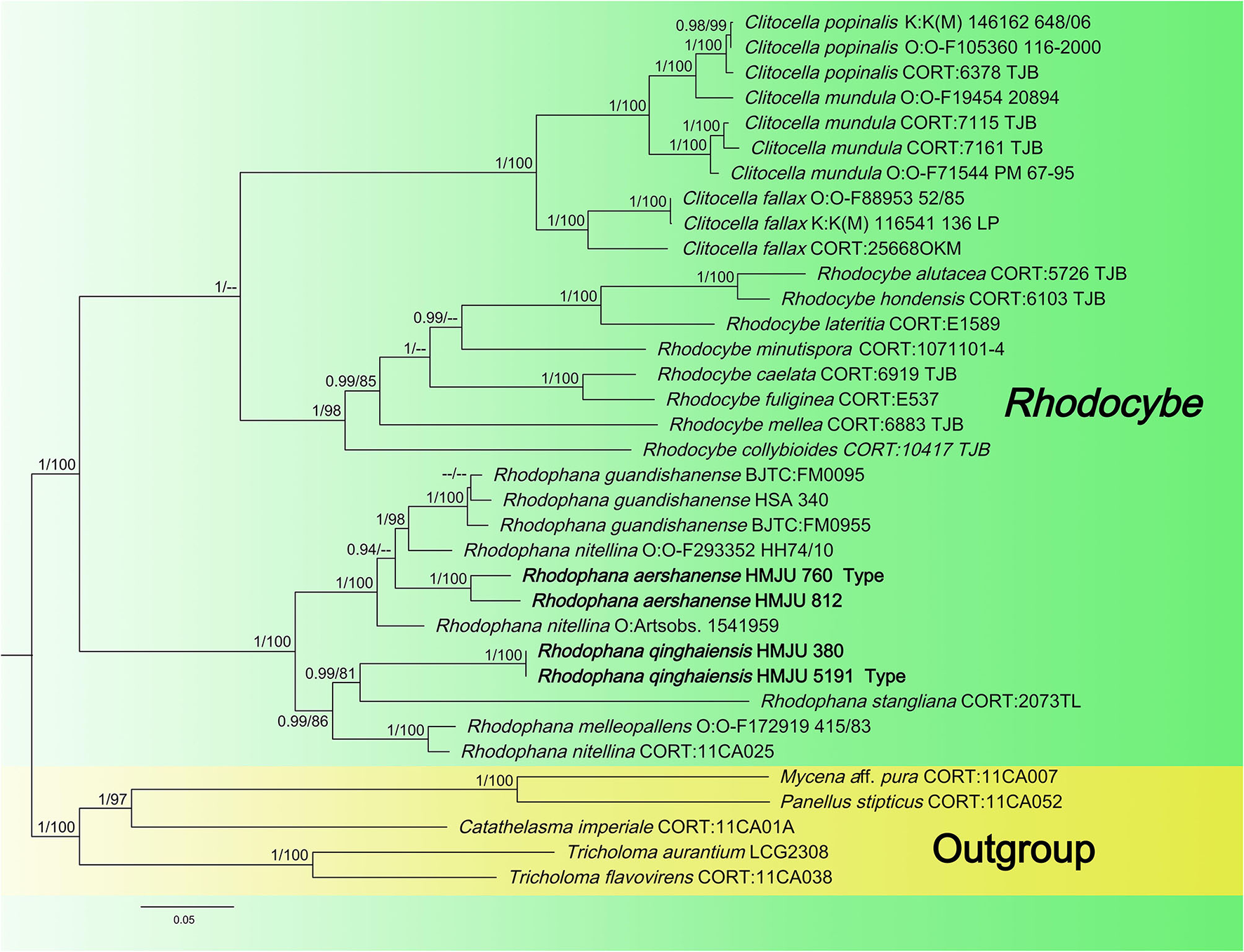

Figure 2

Maximum likelihood tree based on analyses of the nrLSU, rpb2, and tef1-α sequence data.

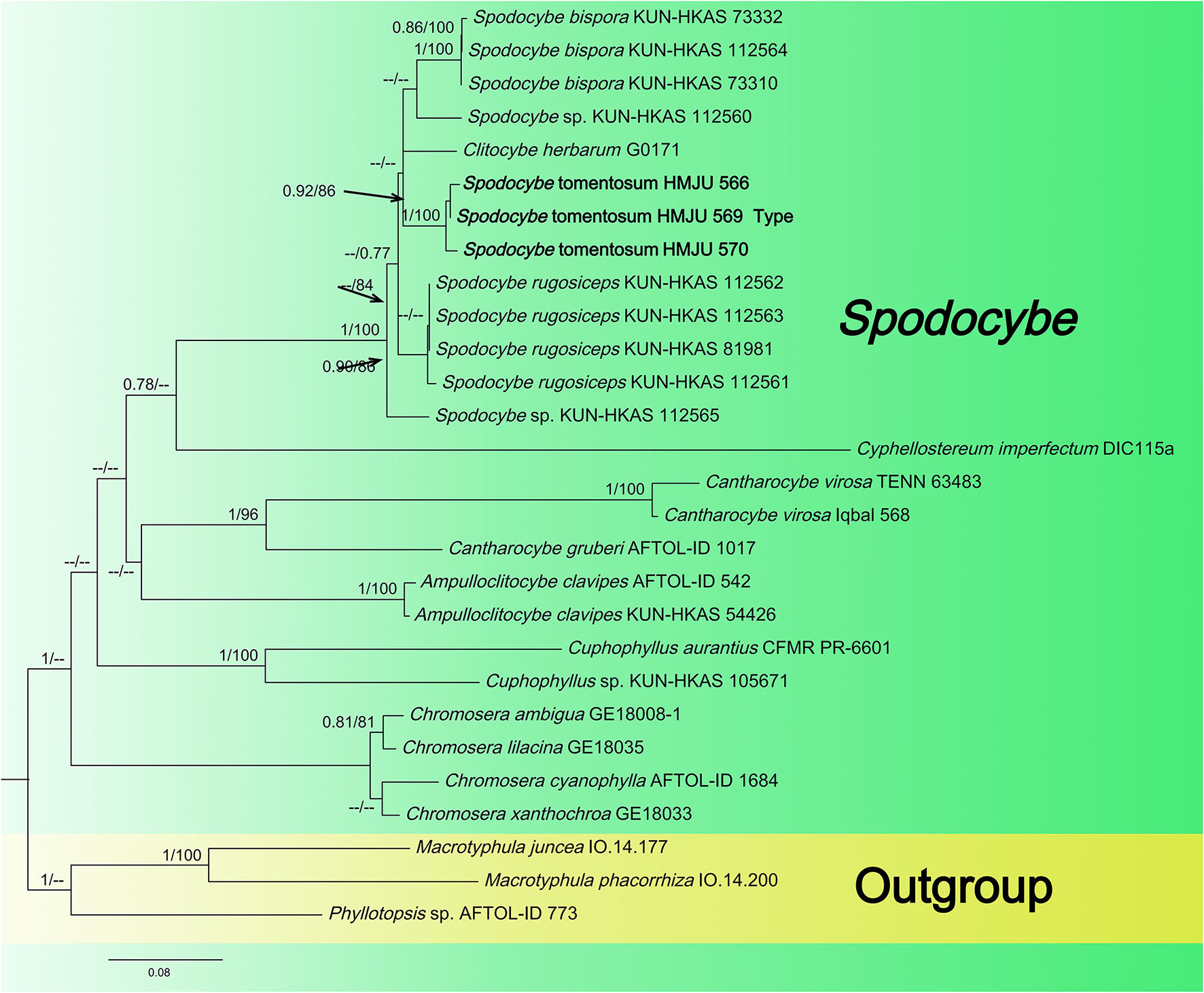

Figure 3

Maximum likelihood tree based on analyses of the ITS, nrLSU, rpb2, and atp6 sequence data.

Table 2

| Species | Collection | GenBank accession numbers | Location | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | nrLSU | rpb2 | tef1-α | atp6 | |||

| Ampulloclitocybe clavipes | AFTOL-ID 542 | AY789080 | AY639881 | AY780937 | – | – | – |

| KUN-HKAS 54426 | MW616462 | MW600481 | MW656471 | – | – | China | |

| Cantharocybe gruberi | AFTOL-ID 1017 | DQ200927 | DQ234540 | DQ385879 | – | – | USA |

| C. virosa | TENN 63483 | KX452405 | JX101471 | – | – | – | India |

| Iqbal 568 | KX452403 | KF303143 | – | – | – | Bangladesh | |

| Chromosera ambigua | GE18008-1 | MK645573 | MK645587 | MK645593 | – | – | France |

| C. cyanophylla | AFTOL-ID 1684 | DQ486688 | DQ457655 | KF381509 | – | – | USA |

| C. lilacina | GE18035 | MK645577 | MK645591 | MK645597 | – | – | Canada |

| C. xanthochroa | GE18033 | MK645576 | MK645590 | MK645596 | – | – | Canada |

| Clitocella fallax | O:O-F88953 52/85 | KC816767 | KC816936 | – | KC816845 | – | Norway |

| CORT:25668OKM | KC816768 | KC816937 | – | KC816846 | – | USA | |

| K:K(M) 116541 136 LP | KC816769 | KC816938 | – | KC816847 | – | Spain | |

| C. mundula | O:O-F71544 PM 67-95 | KC816780 | KC816950 | – | KC816860 | – | Norway |

| CORT:7115 TJB | KC816781 | KC816951 | – | KC816861 | – | USA | |

| CORT:7161 TJB | KC816782 | KC816952 | – | KC816862 | – | USA | |

| O:O-F19454 20894 | KC816784 | KC816954 | – | KC816864 | – | Norway | |

| C. popinalis | K:K(M) 146162 648/06 | KC816795 | KC816970 | – | KC816877 | – | UK |

| O:O-F105360 116-2000 | KC816800 | KC816975 | – | KC816881 | – | Norway | |

| CORT:6378 TJB | KC816801 | KC816976 | – | KC816882 | – | Switzerland | |

| C. herbarum | G0171 | – | MK277719 | – | – | – | Hungary |

| Cuphophyllus aurantius | CFMR PR-6601 | KF291099 | KF291100 | KF291102 | – | – | Puerto Rico |

| C. sp. | KUN-HKAS 105671 | MW762875 | MW763000 | MW789179 | – | – | China |

| Cyphellostereum imperfectum | DIC115a | KF443218 | KF443243 | KF443277 | – | – | Guatemala |

| Hohenbuehelia angustata | DAOM 195432a | MG383817 | MG383827 | – | – | – | Spain |

| HMJAU4149 | GQ142027 | GQ142042 | – | – | – | China | |

| CBS 856.85 | MH861919 | MG383826 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| DAOM 195379 | MG383815 | MH873608 | – | – | – | Netherlands | |

| H. atrocoerulea | AMB 18080 | KU355304 | KU355389 | – | – | – | Italy |

| WU 8016 | KU355309 | KU355390 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| AMB 18084 | KU355301 | KU355388 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| AMB 18102 | KY698000 | KY698001 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| H. auriscalpium | WU 14662 | KU355317 | KU355391 | – | – | – | Italy |

| H. boullardii | JCM06005 | MG553637 | MG553644 | – | – | – | Spain |

| H. carlothornii | AMB 18106 | KY698012 | KY698013 | – | – | – | Italy |

| H. cyphelliformis | Z+ZT 994 | KU355325 | KU355393 | – | – | – | Italy |

| AMB 18085 | KU355324 | KU355392 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| H. faerberioides | Mertens | MG553638 | MG553645 | – | – | – | Spain |

| H. grisea | MCVE 27293 | KU355329 | KU355394 | – | – | – | Italy |

| MCVE 23350 | MH137807 | MH137834 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| H. ilerdensis | Roux 3924 | MG553639 | MG553646 | – | – | – | Spain |

| H. josserandii | P. K. EG10-812-T-F | KU355353 | KU355403 | – | – | – | Italy |

| Roux 3270 | KU355354 | KU355404 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| H. leightonii | WU 5846 | MG553640 | MG553647 | – | – | – | Spain |

| WU 6004 | MH137809 | MH137835 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| P. K. LP 311203-9 | MH137810 | MH137836 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| H. longipes | LIP 0400317 | KU355333 | KU355396 | – | – | – | Italy |

| H. mastrucata | TRTC 152314 | KU355336 | KU355397 | – | – | – | Italy |

| H. petaloides | TFB14021 | KP026226 | KP026217 | – | – | – | USA |

| H. reniformis | HMJAU7091 | GQ142024 | GQ142041 | – | – | – | China |

| H. thornii | AMB 18086 | KU355342 | KU355400 | – | – | – | Italy |

| WU 21790 | KU355343 | MG383831 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| LIP 0401312 | MG383823 | NG060672 | – | – | – | Europe | |

| H. tomentosa | HMJU00101 | MK583558 | MN947621 | – | – | – | China |

| HMJU00102 | MK583564 | MN382128 | – | – | – | China | |

| H. tremula | WU 16294 | KU355359 | KU355407 | – | – | – | Italy |

| DAOM 180808 | KU355357 | KU355405 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| M 0223665 | KU355358 | KU355406 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| H. unguicularis | Z+ZT 1112 | KU355361 | KU355408 | – | – | – | Italy |

| CBS 855.85 | MH861918 | MH873607 | – | – | – | Netherlands | |

| H. valesiaca | PDG 311005 | KU355339 | KU355398 | – | – | – | Italy |

| Roux 2975 | KU355340 | KU355399 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| CL 990909/04 | MH137819 | MH137841 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| JCS 600 B | MH137820 | MH137842 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| H. wilhelmii | WU 7726 | KU355300 | KU355387 | – | – | – | Italy |

| BRNM 576483 | MG383824 | MG383832 | – | – | – | Spain | |

| Z+ZT n. 1154 | MF494947 | MF494948 | – | – | – | Italy | |

| Rhodocybe alutacea | CORT:5726 TJB | KC816762 | KC816931 | – | KC816842 | – | USA |

| R. caelata | CORT:6919 TJB | KC816764 | KC816933 | – | KC816843 | – | USA |

| R. collybioides | CORT:10417 TJB | KC816766 | KC816935 | – | KC816844 | – | Argentina |

| R. fuliginea | CORT:E537 | KC816770 | KC816940 | – | KC816850 | – | Australia |

| R. hondensis | CORT:6103 TJB | KC816771 | KC816941 | – | KC816851 | – | USA |

| R. lateritia | CORT:E1589 | KC816772 | KC816942 | – | KC816852 | – | Australia |

| R. mellea | CORT:6883 TJB | KC816774 | KC816944 | – | KC816854 | – | USA |

| R. minutispora | CORT:1071101-4 | KC816777 | KC816947 | – | KC816857 | – | Spain |

| Rhodophana aershanensis | HMJU 760 | OQ123823 | OP919536 | OP948886 | OP948887 | ||

| HMJU 812 | OQ123821 | OP919537 | OP948888 | OP948889 | |||

| R. guandishanense | BJTC:FM0095 | MT558552 | MT558555 | – | MT558558 | – | China |

| HSA 340 | MT558553 | MT558557 | – | MT558560 | – | China | |

| BJTC:FM0955 | MT558554 | MT558556 | – | MT558559 | – | China | |

| R. melleopallens | O:O-F172919 415/83 | KC816776 | KC816946 | – | KC816856 | – | Norway |

| R. nitellina | O:O-F293352 HH74/10 | KC816788 | KC816958 | – | KC816865 | – | Norway |

| O:Artsobs. 1541959 | KC816790 | KC816961 | – | KC816868 | – | Norway | |

| CORT:11CA025 | KC816792 | KC816965 | – | KC816872 | – | USA | |

| R. qinghaiensis | HMJU 380 | OP919468 | OP919476 | OP948883 | |||

| HMJU 5191 | OQ123822 | OP919551 | OP948890 | ||||

| R. stangliana | CORT:2073TL | – | KC816992 | – | KC816899 | – | Denmark |

| Spodocybe bispora | KUN-HKAS 73310 | MW762880 | MW763005 | MW789184 | – | – | China |

| KUN-HKAS 73332 | MW762881 | MW763006 | MW789185 | – | – | China | |

| KUN-HKAS 112564 | MW762882 | MW763007 | MW789186 | – | – | China | |

| S. rugosiceps | KUN-HKAS 112561 | MW762883 | MW763008 | MW789187 | – | – | China |

| KUN-HKAS 81981 | MW762884 | MW763009 | MW789188 | – | – | China | |

| KUN-HKAS 112562 | MW762887 | MW763012 | MW789191 | – | – | China | |

| KUN-HKAS 112563 | MW762888 | MW763013 | MW789192 | – | – | China | |

| S. sp. | KUN-HKAS 112560 | MW762889 | MW763014 | MW789193 | – | – | China |

| KUN-HKAS 112565 | MW762890 | MW763015 | MW789194 | – | – | China | |

| S. tomentosum | HMJU 566 | OP935679 | OP919483 | OP948882 | – | OP948891 | China |

| HMJU 569 | OP935678 | OP935676 | OP948884 | – | OP948892 | China | |

| HMJU 570 | OP935677 | OP919526 | OP948885 | – | OP948893 | China | |

| Catathelasma imperiale | CORT:11CA01A | KC816816 | KC816994 | – | KC816900 | – | USA |

| Macrotyphula juncea | IO.14.177 | MT232353 | MT232306 | MT242337 | – | – | Sweden |

| M. phacorrhiza | IO.14.200 | MT232363 | MT232314 | MT242347 | – | – | France |

| Mycena aff. pura | CORT:11CA007 | KC816817 | KC816995 | – | KC816901 | – | USA |

| Panellus stipticus | CORT:11CA052 | KC816818 | KC816996 | – | KC816902 | – | USA |

| Phyllotopsis sp. | AFTOL-ID 773 | DQ404382 | AY684161 | AY786061 | – | – | – |

| Pleurotus ostreatus | AFTOL-ID 564 | AY854077 | AY645052 | – | – | – | USA |

| HKAS84903 | KP867913 | KP867901 | – | – | – | Germany | |

| HKAS53480 | KP867914 | KP867902 | – | – | – | Germany | |

| Tricholoma aurantium | LCG2308 | JN019434 | JN019705 | – | JN019386 | – | Canada |

| T. flavovirens | CORT:11CA038 | KC816819 | KC816997 | – | KC816903 | – | USA |

List of fungal species and their information used in the phylogenetic analyses.

The GenBank accession numbers of ITS, nrLSU, rpb2, tef1-α, and atp6 for our specimens were given in bold values.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic analyses

A total of 282 sequences (107 ITS, 109 nrLSU, 29 rpb2, 33 tef1-α, 4 atp6) from 62 samples were used in the phylogenetic analyses, of which 31 (9 ITS, 9 nrLSU, 2 tef1-α, 7 rpb2, 4 atp6) were newly generated in the present study (Table 2). The newly generated sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers are listed in Table 1). In this study, three datasets were analyzed: (i) namely the Hohenbuehelia dataset, (ii) the Rhodophana dataset, and (iii) the Spodocybe dataset.

3.1.1. Hohenbuehelia dataset analyses

In this dataset, the final ITS dataset was composed of 46 sequences, which was 610 base pairs (bps) long and contained 540 (88%) conserved sites, whereas the nrLSU dataset was composed of 48 sequences, which was 798 base pairs long and contained 790 (98%) conserved sites. A total of 46 sequences were complete for both genes, and these datasets were combined for the phylogenetic analysis. The Bayesian PP value was 0.90 (left) and the MLBP value was 75% (right), and the nodes are annotated. The maximum likelihood tree is presented in Figure 1 with bootstrap values provided on the branches. Our sequences assembled together and fell under the genus Hohenbuehelia, which indicated that it should be a member of Hohenbuehelia. In particular, H. tomentosa formed a strongly supported branch in the phylogenetic trees where it occupies an independent but uncertain position with regard to the genus Hohenbuehelia.

3.1.2. Rhodophana dataset analyses

Four tef1-α, four rpb2, and two atp6 sequences of four specimens were newly generated in this study. The sequences were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers are listed in Table 1). The Bayesian and ML analyses resulted in a topology similar to the MP analysis, so only the ML tree was shown (Figure 2). Nodes were annotated if supported by >0.90 Bayesian PP (left) or >75% MLBP (right) values according to Vizzini et al. (2015) and Cai et al. (2020). For the ML analysis, sequences relating to 22 species were added. The ML tree represented in Figure 2 shows detailed results with high bootstrapping values. The outgroups used were Mycena aff. pura, Panellus stipticus, Catathelasma imperiale, Tricholoma aurantium, and Tricholoma flavovirens. The monophyly of the Rhodophana clade was strongly supported (BP = 100%, PP = 1.00), including Rhodophana qinghaiensis HMJU380 and Rhodophana qinghaiensis HMJU5191 (BP = 100%, PP = 1.00), Rhodophana aershanensis HMJU812 and Rhodophana aershanensis HMJU760 (BP = 100%, PP = 1.00), and four other Rhodophana species. Rhodophana qinghaiensis HMJU380 and Rhodophana qinghaiensis HMJU5191 independently separated a clade, and Rhodophana aershanensis HMJU812 and Rhodophana aershanensis HMJU760 also independently separated a clade (Figure 1). Four specimens fell under Rhodophana, which belonged to the genus Rhodophana and, therefore, should be a member of Rhodophana.

3.1.3. Spodocybe dataset analyses

The Spodocybe dataset, consisting of 130 sequences dataset, was applied to phylogenetic analysis for displaying the relationships. Macrotyphular juncea (Alb. & Schwein.) Berthier., Macrotyphula phacorrhiza (Reichard) Olariaga et al., and Phyllotopsis sp. were used as the outgroups. Both BI and ML approaches resulted in the same tree topology; as such, only the ML tree was shown, with Bayesian PP values (left) and maximum likelihood tree BP values (right) provided near each node (Figure 3). In the three-gene tree (Figure 3), all new collections of Spodocybe from China fell into the Spodocybe clade and formed an independent clade. One collection (nrLSU: MK27771) from Hungary, labeled Clitocybe herbarum Romagn., fell under the Spodocybe clade, indicating that it should be a member of Spodocybe.

3.2. Taxonomy

3.2.1. Hohenbuehelia tomentosa J. Z. Xu, sp. nov.

Fungal Names number: FN 571264, Figure 4.

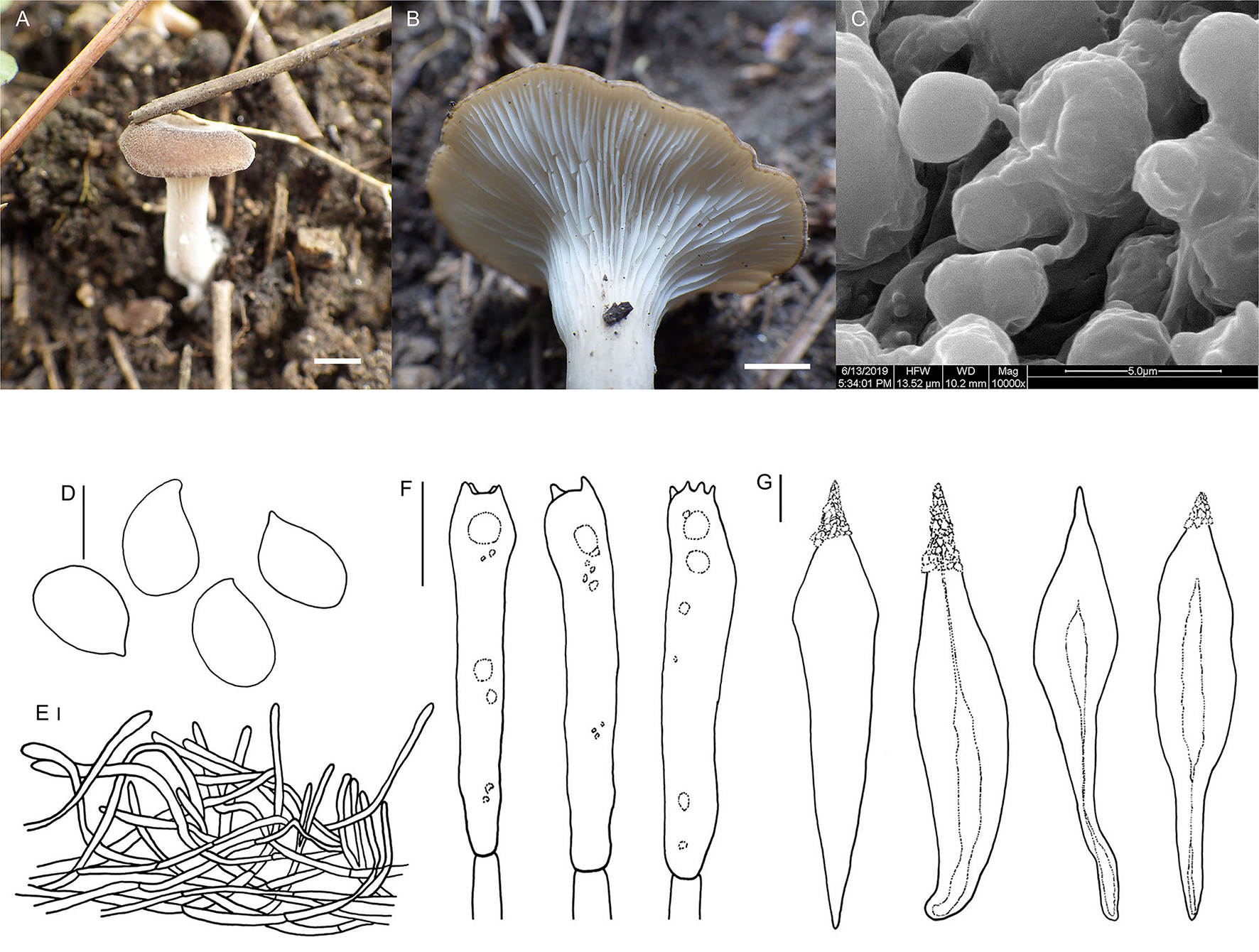

Figure 4

Hohenbuehelia tomentosa (HMJU00101, holotype). (A, B) Habitat and basidiocarps; (C) SEM images of basidiospores; (D) basidiospores; (E) pileipellis; (F) basidia; (G) Cheilometuloids. Bars: [(A) = 0.83 cm; (B) = 0.5 cm; (D, F, G) = 5 μm; (E) =2 μm].

Diagnosis: Distinguished by a dark brown pileus with finely dense pure white tomentum; decurrent, pure white lamellae; a dirty white, subcentral stipe with a longitudinally fibrous striate surface; smooth, ellipsoid to oblong-ellipsoid spores; fusiform metuloid cystidia.

Holotype—China. Liaoning Province, Fumeng Town, Haitang Mountain, on humus or ground by the road, 6 August 2016, J. Z. Xu, HMJU00101.

Etymology—tomentosa (Lat.): referring to the pileus, which is always with finely dense pure white tomentum on the surface.

Description: Pileus 1.5–4.0 cm diam, subcircular, extremely depressed at the center, subfunnel-shape, margin incurved; surface with finely dense pure white tomentum at all ages, with radial stripes; gray-brown (7A3) to almost black, in some places dark brown (7E6) when young, dark brown (7E6) with a nearly black (6F6) center at a later stage; context thin; 1–2 mm thick at pileus. Lamellae 1.5–2.0 mm broad, decurrent, pure white, with fine pure white frosting at times, crowded, with one intercalated lamellula between each pair of lamellae reaching the stipe at times, edge concolorous, entire, even. Stipe 2–4 × 0.7– 0.9 cm, eccentric, broadened at base, and longitudinally fibrous striate; pale grayish beige (29A2) to dirty white (28A2). Smell and taste are insignificant.

Basidiospores (4.6) 5.0–7.1 (7.6) × (3.3) 3.6–4.4 (4.6) μm, Q = (1.44) 1.52–1.92 (1.98), (n = 30), ellipsoid to oblong-ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, some with one or more oil drop, and inamyloid. Basidia (20) 22–25 (27) × 4.7–6.0 μm, clavate to subcylindrical, slightly broadened at apex, subhyaline, with two or four sterigmata, and sterigmata up to 2.1–3.6 (4.1) μm long. Thin-walled cystidia, rare. Metuloid cheilo- and pleurocystida abundant, cheilometuloids (41) 54–69 (76) × (8.8) 9.1–11.6 (14) μm, fusiform, subcylindrical to ventriculose, thick-walled, mostly with a narrow base and a lanceolate apical part, and incrusted with crystals at apex, some extremely broadened at the apex. Pleurometuloids similar to cheilometuloids. Hymenophoral trama is made up of regular, radially parallel hyphae, hyphae 2.5–5.6 μm wide, cylindrical, thin-walled, clamped, hyaline, smooth. Pileipellis is composed of thin-walled, branched, interwoven hyphae, hyphae 2.2–4.5 μm wide, tomentum, cylindrical, not or slightly constricted at the septa, hyaline, smooth.

Habitat: Scattered or single on humus or ground by the road. Known from Liaoning Province in China.

Additional specimen examined—China. Liaoning Province, Fumeng Town, Haitang Mountain, on soil under mixed forests dominated by Quercus mongolica 41°56′20.7′′N, 121°50′13.9′′E, 350 m, 6 August 2016, J. Z. Xu, HMJU00102.

Note: Morphologically, it is closely related to members of the subgenus Hohenbuehelia due to the eccentric stipe and smooth spores (Singer, 1986). Hohenbuehelia longipes (Boud.) M. M. Moser., H. culmicola Bon. and H. ilerdensis Courtec., Vila & Rocabruna., share similar features with our species, whereas H. culmicola growing on culms and leaf-sheaths of Ammophila arenaria in coastal dunes produces a not translucent-striate, densely tomentose pileus, and a brown stipe covered in gray villose surface (Noordeloos, 1987). H. longipes mainly differs from H. tomentosa in having a longer stipe (40–60 (80) × 3–5 (8) mm in H. longipes, 20–40 × 7–9 mm in H. tomentosa), a brown-ochraceous to isabelline pileus and whitish-ochraceous gills (Thorn and Barron, 1986; Watling and Gregory, 1989). Hohenbuehelia. ilerdensis, growing at the bases of dead grasses in semi steppe communities, is distinguished from H. tomentosa in having a convex to flattened, smooth, violaceous to reddish brown pileus, a cylindrical, greyish stipe, and abundant cheilocystidia (Courtecuisse et al., 1999).

3.2.2. Rhodophana qinghaiensis J. Z. Xu, sp. nov.

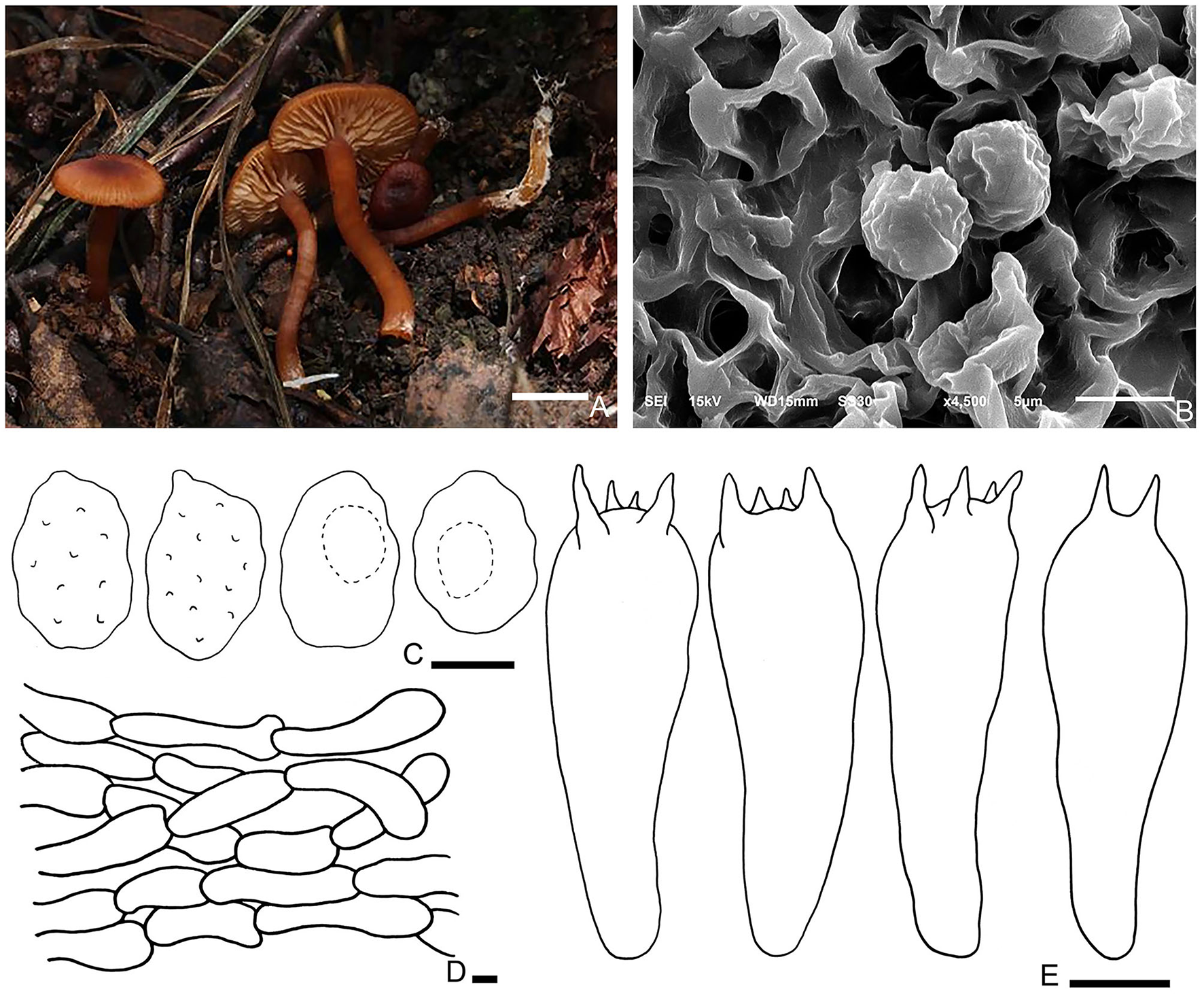

Fungal Names number: FN 571265, Figure 5.

Figure 5

Rhodophana qinghaiensis (HMJU5191, holotype). (A) Habitat and basidiocarps; (B) SEM images of basidiospores; (C) basidia; (D) pileipellis; (E) basidiospores. Bars: [(A) = 1 cm; (B, C) = 5 μm; (D, E) = 10 μm].

Diagnosis: Pileus reddish brown. Lamellar adnexed, gray-orange. Stipe light orange to reddish brown. Clamp connections are present. Basidiospores with strongly verrucose ornamentation all over.

Holotype—China. Qinghai Province, Haixi Korean, Halihatu National Forest Park, 37°2′0′′N, 98°39′32.4′′E, 3,604.1 m, 5 August 2018, J. Z. Xu, HMJU5191.

Etymology—qinghaiensis (Lat.): referring to the collection site.

Description: Pileus 1–2.5 cm in diam, applanate, umbo in the center, surface dry, not smooth, not hygrophanous; margin incurved becoming decurved, entire and regular; reddish brown (8E5) at the center, and brown-orange (7B5) at the margin. Lamellar adnexed, medium close, with lamellulae of 1–3 lengths; gray-orange (6B5). Edge concolor, entire, some broken in the middle, even. Stipe 2–3 × 0.3–0.6 cm, central, cylindrical, equal or slightly tapering toward the base, surface glabrous, smooth, solid; initially light orange (6B4), and becoming reddish brown (8D8) with age.

Basidiospores (5.9–) 6.2–8.2 (−8.6) × (4.1–) 4.5–5.9 (−6.5) μm, Q = 1.14–1.73, Qm = 1.4, broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid in face view, oblong or amygdaliform in profile view, with strongly verrucose ornamentation all over, thin-walled, inamlyloid, brown in 3% of the KOH. Basidia (24.9–) 27.0–32.6 (−40.9) × 7.6–11.3 μm, clavate, mostly 4-spored, some 2-spored, sterigmata up to 4.9 μm long. Hymenophoral trama regular, hyphae cylindrical, hyaline, 6–16 μm wide. Pileipellis, a cutis of subparallel, cylindrical hyphae, hyaline, 3.2–9.0 μm in diam, thin-walled. Clamp connections are present.

Habitat: Scattered on the moss in coniferous forest.

Additional specimen examined—China. Qinghai Province, Haixi Korean, Halihatu National Forest Park, 5 August 2018, J. Z. Xu, HMJU380.

Notes: The key characteristics of R. qinghaiensis are reddish brown pileus, margin incurved becoming decurved, entire, gray-orange and adnexed lamellar, entire or broken in the middle, light orange to reddish brown, and smooth and solid stipe. Rhodophana flavipes T. J. Baroni, P. P. Daniëls & O. Hama. differs from R. qinghaiensis in the pileus with fibrils and squamules, adnexed lamellar and light yellow, and hollow stipe with reddish bruising of fibrils; Rhodophana squamulosa K. P. D. Latha & Manim. also have gray-orange lamellar, but R. squamulosa have squamules on the pileus. In addition, R. squamulosa has adnexed lamellar and hollow stipe with appressed fibrillose all over.

3.2.3. Rhodophana aershanensis J. Z. Xu, sp. nov.

Fungal Names number: FN 571266, Figure 6.

Figure 6

Rhodophana aershanensis (HMJU760, holotype). (A) Habitat and basidiocarps; (B) SEM images of basidiospores; (C) basidiospores; (D) pileipellis; (E) basidia. Bars: [(A) = 1 cm; (B, E) = 5 μm; (C) = 3 μm; (D) = 10 μm].

Diagnosis: Pileus dark brown or reddish brown, with striate incurved margin. Lamellar light orange, decurved. Stipe solid, with white basal mycelial cord. Clamp connections, present. Basidiospores undulate-pustulate, inamyloid.

Holotype—China. Neimenggu Autonomous Region, Aershan City, Bailang Town, 18 August 2020, J. Z. Xu, HMJU760.

Etymology—aershanensis (Lat.): referring to the collection site.

Description: Pileus 1–2 cm in diam, smooth, slightly hygrophanous when young, gradually becoming dry with age; umbo in the center, depressed at sides when young, applanate with a small, obtuse bulge when mature, the depression becoming subsulcate with expansion; margin striped, incurved, regular, even; initially dark brown (8F6) at the center, margin reddish brown (9E8), reddish brown (9E7) with age, brown-orange (7B7) toward the margin. Lamellar decurrent, medium crowded, with lamellulae of 3–4 lengths; edges concolor, entire and even; light orange (7C6). Stipe 2–3.5 × 0.3– 0.5 cm, central, cylindrical, curved toward apex, equal or slightly tapering toward the base, glabrous, smooth, solid, with white basal mycelial cord; dark brown (9F6) at first, reddish brown (8D8) with age, and light orange (7C7) at the base.

Basidiospores (1.3–) 2.7–5.8 (−6.6) × (1.2–) 2.2–5.1 (−6.2) μm, Q = 1.04–1.39, Qm = 1.1, lacrymoid (ellipsoid with suprahilar depression), the surface undulate-pustulate, slightly undulate-pustulate all over, thin-walled, hyaline, with a large guttula, inamyloid. Basidia 20.8–24.6 (−26.4) × (6.7–) 7.2–8.9 (−9.6) μm, clavate, hyaline, mostly tetrasporic, sterigmata up to 2.5 μm long. Hymenophoral trama regular, hyaline, cylindrical hyphae, 2–9 μm wide. Pileipellis, a cutis of subparallel, dense, cylindrical hyphae, hyaline, 3.2–14.6 μm in diam., and thin-walled. Clamp connections are present.

Habitat: Scattered on soil in mixed forests.

Additional specimen examined—China. Neimenggu Autonomous Region, Aershan City, Bailang Town, 18 August 2020, J. Z. Xu, HMJU812.

Notes: Rhodophana flavipes resembles Rhodophana aershanensis due to the reddish-brown pileus, and light orange lamellar, but R. flavipes has scaly, hygrophanous pileus, adnexed lamellar, and light yellow, hollow stipe; Rhodophana canariensis (Dähncke, Contu, and Vizzini) T. J. Baroni & Bergemann. showed similarities with Rhodophana aershanensis in the appearance of striations on the pileus, however, R. canariensis is differentiated by tan and hygrophanous pileus, light pink and adnate lamellar, and stipe with orange basal tomentum.

3.2.4. Spodocybe tomentosum J. Z. Xu, sp. nov.

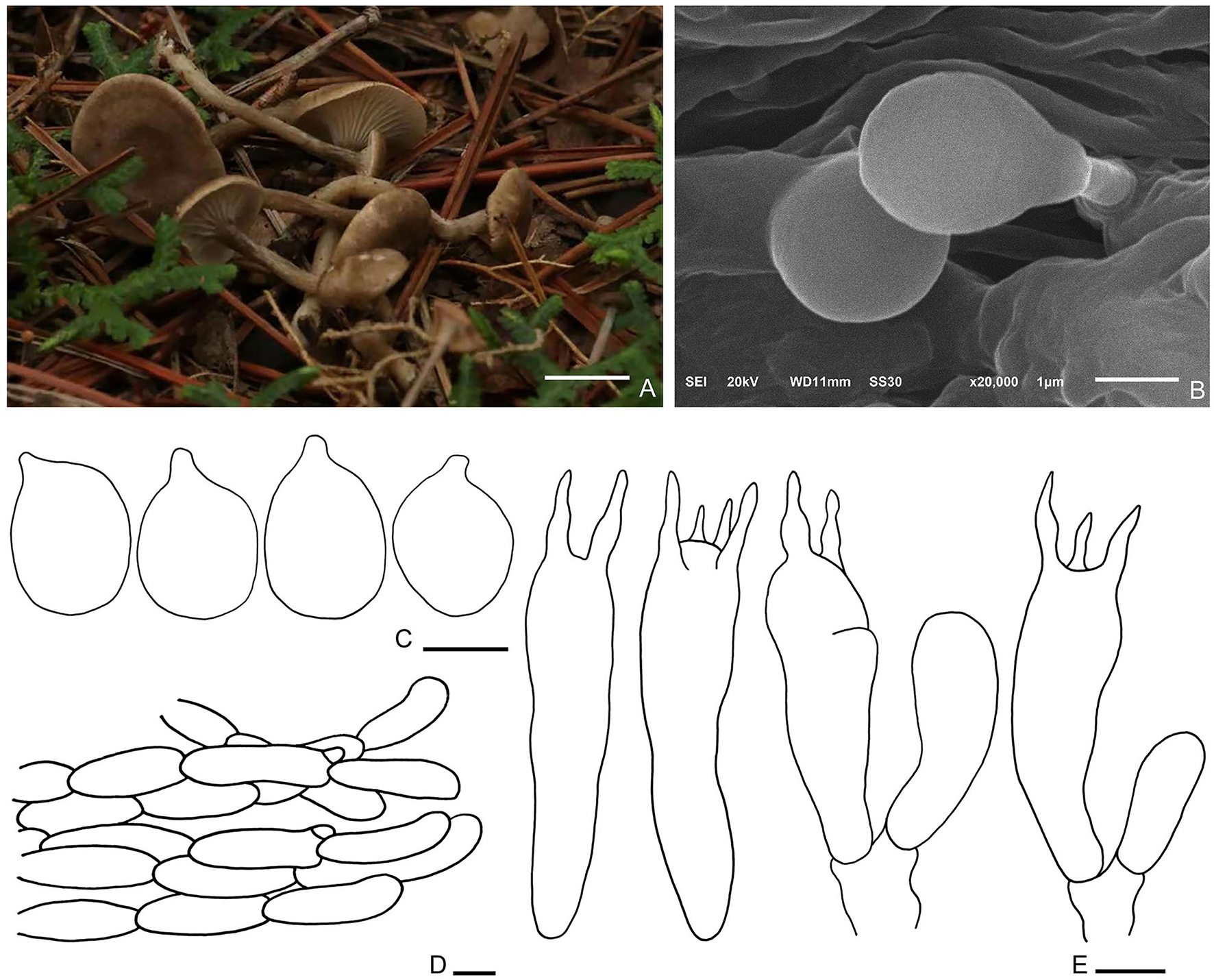

Fungal Names number: FN 571267, Figure 7.

Figure 7

Spodocybe tomentosum (HMJU569, holotype). (A) Habitat and basidiocarps; (B) SEM images of basidiospores; (C) basidiospores; (D) pileipellis; (E) basidia. Bars: [(A) = 1 cm; (B) = 1 μm; (C) = 3 μm; (D) = 10 μm; (E) = 5 μm].

Diagnosis: Basidiomes small, subclitocyboid. Pileus 1.5–3 cm in diam, at first applanate, then concave. Lamellae decurrent. Stipe central, hollow. Basidiospores are broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, and inamyloid. Clamp connections were abundant.

Holotype—China. Liaoning Province, Fuxin City, Haitang Mountain, 41°53′50.6′′N, 121°47′18.3′′E, 428.8 m, 9 August 2019, J. Z. Xu, HMJU569 (holotype).

Etymology—tomentosum (Lat.): referring to the pileus, which was always with finely dense pure white tomentum on the surface.

Description: Basidiomes small, subclitocyboid. Pileus 1.5–3 cm in diam, at first applanate, then concave; with finely dense pure white tomentum on the surface; brown (7F7) to dark brown (7E6), gradually fading toward the margin; with papillae to applanation in the center. Lamellae decurrent, relatively crowded, with intercalated lamellulae, sometimes forked, concolorous with margin. Stipe 1.5–3.5 × 0.3–0.5 cm, equally thick, central, hollow; surface nearly smooth or slightly longitudinal stripe, concolorous with pileus.

Basidiospores (3.1–) 3.3–4.9 (−5.4) × 2.2–3.8 μm, Q = 1.22–1.55, Qm = 1.4, broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled, inamyloid. Basidia (19.9–) 23.6–27.6 × 5.4–6.7 μm, clavate, hyaline; 4-spored majority, 2-spored minority, sterigmata up to 4.4 μm long. Cystidia absent. Hymenophoral trama regular, hyphae cylindrical, hyaline, 1–7 μm wide. Pileipellis, a cutis, cylindrical, hyphae 9–10 μm wide, enlarged at the end. Clamp connections are abundant.

Habitat: Scattered on soil in coniferous forests.

Additional specimen examined—China. Liaoning Province, Fuxin City, Haitang Mountain, 9 August 2019, J. Z. Xu, HMJU566; Liaoning Province, Fuxin City, Haitang Mountain, 9 August 2019, J. Z. Xu, HMJU570.

Note: Spodocybe tomentosum differs from S. rugosiceps in that the pileus never forms rugosity during growth. Microscopically, S. tomentosum is mainly different from S. rugosiceps in having broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid basidiospores. Spodocybe tomentosum and S. bispora can be differentiated by the broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid basidiospores with Q = 1.22–1.55 (basidiospores cylindrical Q = (2.05) 2.11–3 (3.33) in S. bispora) and 2 to 4 spored basidia (He and Yang, 2021).

4. Discussion

In the Index Fungorum, Hohenbuehelia contains 135 valid records, Rhodophana contains 13 valid records, and Spodocybe contains 6 valid records. In addition, R. guandishanense, S. bispora, and S. rugosiceps were published in China. Our present study demonstrates a new species of Hohenbuehelia, two new species of Rhodophana, and a new species of Spodocybe based on both morphological characteristics and molecular phylogenetic analyses.

In the ITS + nrLSU tree, H. tomentosa formed an independent lineage and grouped with H. auriscalpium (Maire) Singer. Hohenbuehelia auriscalpium lacks a subcentral, fibrous striate stipe, and the cheilometuloids incrusted with crystals in H. auriscalpium are rare (Singer and Kuthán, 1980). In addition, H. longipes, H. tremula (Schaeff.) Thorn & G. L. Barron., H. wilhelmii Consiglio & Setti., H. angustata (Berk.) Singer., H. thornii Consiglio & Setti., and H. petaloides (Bull.) Schulzer are closely related to H. tomentosa. Morphologically, H. longipes mainly differs from H. tomentosa in having a longer stipe (40–60 (80) × 3–5 (8) mm in H. longipes, 20–40 × 7–9 mm in H. tomentosa), a brown-ochraceous to isabelline pileus, and whitish-ochraceous gills (Thorn and Barron, 1986; Watling and Gregory, 1989). Hohenbuehelia petaloides, H. angustata, H. wilhelmii, and H. tremula all lack a subcentral, fibrous striate stipe (Singer and Kuthán, 1980; Thorn and Barron, 1986; Corner, 1994; Consiglio et al., 2018). Hohenbuehelia thornii has a gelatine layer in its pileipellis, which is absent in H. tomentosa (Consiglio, 2017).

The key characteristics of R. qinghaiensis are reddish brown pileus, margin incurved becoming decurved, entire, gray-orange and adnexed lamellar, and entire or broken in the middle, light orange to reddish brown, smooth and solid stipe. The main characteristics of R. aershanense are the dark brown or reddish-brown pileus with striate incurved margin, light orange and decurved lamellar, and dark brown or reddish-brown and solid stipe with white basal mycelial cord. In the phylogenetic tree, R. qinghaiensis forms an independent lineage and is grouped with R. stangliana (Bresinsky and Pfaff) Vizzini. Rhodophana aershanensis formed an independent lineage. Rhodophana qinghaiensis differs from R. aershanensis by having the pileus without hygrophanous, lamellar adnexed, basidiospores without guttula, and sterigmata longer. Rhodophana guandishanensis differs from R. qinghaiensis in that it has orange-yellow and not-striate pileus, decurrent lamellar, and hollow stipe. Rhodophana guandishanensis resembles R. aershanensis due to its decurrent lamellar, but R. guandishanensis has an orange-yellow and not-striate pileus, light yellow lamellar, and light orange and hollow stipe.

Spodocybe tomentosum is characterized as subclitocyboid and small basidiomes, decurrent lamellae, central stipe, broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid and inamyloid basidiospores, and abundant clamp connections. In the ML tree, S. tomentosum formed an independent lineage. In addition, Cantharocybe and Ampulloclitocybe also have a good genetic relationship. Spodocybe tomentosum differs from S. rugosiceps, in that the pileus never forms rugosity during growth. Spodocybe tomentosum is mainly different from S. rugosiceps in having broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid basidiospores. Spodocybe tomentosum and S. bispora can be differentiated by the broadly ellipsoid to ellipsoid basidiospores with Q = 1.22–1.55 (basidiospores cylindrical Q = (2.05) 2.11–3 (3.33) in S. bispora) and 2 to 4 spored basidia (He and Yang, 2021).

In summary, our study used morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analysis to identify four new species, namely H. tomentosa, R. qinghaiensis, R. aershanensis, and S. tomentosum.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

JX and TW wrote the manuscript. JX, YJ, XL, and DZ carried out experiments. MIH revise manuscript. JX collecting specimens and designed experiments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province (20220204066YY) and the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team of Jilin Agricultural Science and Technology University.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrus Voitk for revising the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Baroni T. J. (1981). The genus Rhodocybe maire (Agaricales). Beihefte. Nova Hedwig.67, 1–194.

2

Binder M. Larsson K. H. Matheny P. B. Hibbett D. S. (2010). Amylocorticiales ord. nov. and Jaapiales ord. nov.: early diverging clades of Agaricomycetidae dominated by corticioid forms. Mycologia102, 865–880. 10.3852/09-288

3

Buyck B. Eyssatier G. Dima B. Consiglio G. Noordeloos M. E. Papp V. et al . (2021). Fungal biodiversity profiles 101–110. Cryptogamie Mycol.42, 63–89. 10.5252/cryptogamie-mycologie2021v42a5

4

Cai Q. LvLi Y. J. Kost G. Yang Z. L. (2020). Tricholyophyllum brunneum gen. et. sp. nov. with bacilliform basidiospores in the family Lyophyllaceae. Mycosystema39, 1–13.

5

Consiglio G. (2017). Nomenclatural novelties. Index Fungorum 326, 1.

6

Consiglio G. Setti L. Thorn R. G. (2018). New species of Hohenbuehelia, with comments on the Hohenbuehelia atrocoerulea—Nematoctonus robustus species complex. Persoonia41, 202–212. 10.3767/persoonia.2018.41.10

7

Corner E. J. H. (1994). “On the agaric genera Hohenbuehelia and Oudemansiella. Part I: Hohenbuehelia,” in The Gardens' Bulletin. Vol. 5 (Singapore: National Parks Board), 1–47.

8

Courtecuisse R. Vila J. Llimona X. (1999). Hohenbuehelia ilerdensis, a new graminicolous species from semisteppe areas of Lleida (western Catalonia, Spain). Mycotaxon70, 1–5.

9

Daniëls P. P. Baroni T. J. Hama O. Kluting K. Bergemann S. Garcia-Pantaleon F. I. et al . (2017). A new species and a new combination in Rhodophana (Entolomataceae, Agaricales) from Africa. Phytotaxa306, 223–23310.11646/phytotaxa.306.3.5

10

Drechsler C. (1941). Some hyphomycetes parasitic on free-living terricolous nematodes. Phytopathology31, 773–802. 10.2307/3754415

11

He Z. M. Yang Z. L. (2021). A new clitocyboid genus Spodocybe and a new subfamily Cuphophylloideae in the family Hygrophoraceae (Agaricales). MycoKeys79, 129–148. 10.3897/mycokeys.79.66302

12

Kalyaanamoorthy S. Minh B. Q. Wong T. Von Haeseler A. Jermiin L. S. (2017). ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods14, 587–589. 10.1038/nmeth.4285

13

Katoh K. Standley D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol.30, 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010

14

Kirk P. M. Cannon P. F. David J. C. Stalpers J. A. (2001). Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edn.Wallingford: CABI International.

15

Kluting K. L. Baroni T. J. Bergemann S. E. (2014). Toward a stable classification of genera within the Entolomataceae: a phylogenetic re-evaluation of the rhodocybe-clitopilus clade. Mycologia106, 1127–1142. 10.3852/13-270

16

Kornerup A. Wanscher J. H. K. (1978). The Methuen Handbook of Colour. London: Eyre Methuen.

17

Koziak A. T. E. Cheng K. C. Thorn R. G. (2007). Phylogenetic analyses of Nematoctonus and Hohenbuehelia (Pleurotaceae). Can. J. Bot. 85, 762–773. 10.1139/B07-083

18

Kretzer A. M. Bruns T. D. (1999). Use of atp6 in fungal phylogenetics: an example from the Boletales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 13, 483–492. 10.1006/mpev.1999.0680

19

Kühner R. (1947). Agaricus (Clitocybe) hirneolus fries, champignon souvent me'connu en France aujourd'hui et la tribu nouvelles des Orcelle's. Bull. Trimestriel Soc. Mycol. France62, 183–193.

20

Kühner R. Lamoure D. (1971). Agaricales de la zone alpine. Genre Rhodocybe R. maire. Bull. Trimestriel Soc. Mycol. France87, 15–23.

21

Kumar A. M. Vrinda K. B. Pradeep C. K. (2018). Two new species of Crepidotus (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) from peninsular India. Phytotaxa372, 67–78. 10.11646/phytotaxa.372.1.5

22

Liu Y. Bau T. Li T. H. (2010). Three new records of the genus Hohenbuehelia in China. Mycosystema29, 454–458. 10.13346/j.mycosystema.2010.03.003

23

Lodge D. J. Padamsee M. Matheny P. B. Aime M. C. Cantell S. A. Boertmann D. et al . (2014). Molecular phylogeny, morphology, pigment chemistry and ecology in Hygrophoraceae (Agaricales). Fungal Divers. 64, 1–99. 10.1007/s13225-013-0259-0

24

Matheny P. B. (2005). Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe; Agaricales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.35, 1–20. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.014

25

Matheny P. B. Curtis J. M. Hofstetter V. Aime M. C. Moncalvo J. M. Ge Z. W. et al . (2006). Major clades of Agaricales: a multilocus phylogenetic overview. Mycologia98, 982–995. 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832627

26

Matheny P. B. Wang Z. Binder M. Curtis J. M. Lim Y. W. Nilsson H. et al . (2007). Contributions of rpb2 and tef1 to the phylogeny of mushrooms and allies (Basidiomycota, fungi). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.43, 430–451. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.08.024

27

Mentrida C. S. (2016). Species Delimitation and Phylogenetic Analyses of the Genus Hohenbuehelia in central Europe. Vienna: University of Vienna.

28

Nguyen L.-T. Schmidt H. Von Haeseler A. Minh B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300

29

Noordeloos M. E. (1987). Notulae ad floram agaricinam neerlandicam—XV. Marasmius, Marasmiellus, Micromphale, and Hohenbuehelia. Persoonia Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi13, 237–262.

30

Pilát A. Veselý R. (1935). “Pleurotus fries,” in Atlas des Champignons de l'Europe Chez les éditeurs (Praha).

31

Raj K. N. A. Latha K. P. D. Iyyappan R. Manimohan P. (2016). Rhodophana squamulosa—a new species of entolomataceae from India. Mycoscience57, 90–95. 10.1016/j.myc.2015.10.001

32

Rehner S. A. Buckley E. (2005). A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-alpha sequences: evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia97, 84–98. 10.3852/mycologia.97.1.84

33

Ronquist F. Teslenko M. Van Der Mark P. Ayres D. L. Darling A. Hoehna S. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

34

Schulzer von Müggenburg S. J. Kanitz A. Knapp J. A. (1866). Die bisher bekannten Pflanzen Slavoniens. Vienna: Ein Versuch.

35

Singer R. (1986). The Agaricales in Modern Taxonomy.Koenigstein: Koeltz Scientific Books.

36

Singer R. Kuthán J. (1980). Comparison of some lignicolous white-spored American agarics with European species. Ceska Mykol.34, 57–73.

37

Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics.22, 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446

38

Sudhir K. Glen S. Koichiro T. (2016). Mega7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054

39

Taylor J. W. (2011). One fungus = one name: DNA and fungal nomenclature twenty years after PCR. IMA Fungus2, 113–120. 10.5598/imafungus.2011.02.02.01

40

Thorn R. G. (2013). Nomenclatural novelties. Index Fungorum 16, 1.

41

Thorn R. G. Barron G. L. (1986). Nematoctonus and the tribe Resupinateae in Ontario, Canada. Mycotaxon25, 321–453.

42

Thorn R. G. Moncalvo J. M. Reddy C. A. Vilgalys R. (2000). Phylogenetic analyses and the distribution of nematophagy support a monophyletic Pleurotaceae within the polyphyletic pleurotoid-lentinoid fungi. Mycologia92, 241–252. 10.1080/00275514.2000.12061151

43

Vilgalys R. Hester M. (1990). Rapid genetic identifification and mapping of enzymatically amplifified ribosomal dna from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol.172, 4238–4246. 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990

44

Vizzini A. Alvarado P. Dima B. (2021). Nomenclatural Novelties. Rivista Micologica Romana, Bolletino dell' Associazione Micologica Ecologica Romana.

45

Vizzini A. Consiglio G. Setti L. Ercole E. (2015). Calocybella, a new genus for Rugosomyces pudicus (Agaricales, Lyophyllaceae) and emendation of the genus Gerhardtia. IMA Fungus6, 1–11. 10.5598/imafungus.2015.06.01.01

46

Vizzini A. Dähncke R. M. Contu M. (2011). Clitopilus rubroparvulus (Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetes), a new species from the Canary Islands (Spain). Mycosphere2, 291–295.

47

Vizzini A. Dähncke R. M. Contu M. (2012). Clitopilus canariensis (Basidiomycota, Entolomataceae), a new species in the C. nitellinus-complex (Clitopilus subg. rhodophana) from the Canary Islands (Spain). Brittonia63, 484–488. 10.1007/s12228-011-9187-z

48

Watling R. Gregory N. M. (1989). Crepidotaceae, Pleurotaceae and other pleurotoid agarics. Br. Fungus Flora6, 1–157.

49

Wendland J. Kothe E. (1997). Isolation of tef1 encoding translation elongation factor EF1α from the homobasidiomycete Schizophyllum commune. Mycol. Res.101, 798–802. 10.1017/S0953756296003450

50

White T. J. Bruns T. Lee S. Taylor J. (1990). 38 – Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 38, 315–322.

51

Xu J. Z. Yu X. D. Lu M. Z. Hu J. J. Moodley O. Zhang C. L. et al . (2019). Phylogenetic analyses of some melanoleuca species (Agaricales, Tricholomataceae) in Northern China, with descriptions of two new species and the identification of seven species as a first record. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2167. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02167

52

Yan J. Wang X. Y. Wang X. H. Chen Z. H. Zhang P. (2020). Two new species of Clavaria (Agaricales, Basidiomycota) from Central China. Phytotaxa477, 71–80. 10.11646/phytotaxa.477.1.5

53

Yang C. Fan L. (2020). Rhodophana guandishanense (Entolomataceae, Agaricales), a new species from China. Phytotaxa455, 173–181. 10.11646/phytotaxa.455.2.9

54

Zhao R. L. Karunarathna S. Raspé O. (2011). Major clades in tropical Agaricus. Fungal Divers.51, 279–296. 10.1007/s13225-011-0136-7

Summary

Keywords

four new species, fungi, morphological studies, mushrooms, phylogenetic analysis, taxonomy

Citation

Xu J, Jiang Y, Wang T, Zhang D, Li X and Hosen MI (2023) Morphological characteristics and phylogenetic analyses revealed four new species of Agaricales from China. Front. Microbiol. 14:1118525. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1118525

Received

07 December 2022

Accepted

06 January 2023

Published

03 February 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Samantha Chandranath Karunarathna, Qujing Normal University, China

Reviewed by

Soumitra Paloi, Chiang Mai University, Thailand; Jaturong Kumla, Chiang Mai University, Thailand

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Xu, Jiang, Wang, Zhang, Li and Hosen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jize Xu ✉ xujz802@nenu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Microbe and Virus Interactions with Plants, a section of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.