Abstract

Cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) and bloodstream infections (BSI) are the most common infectious complications in patients after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Both are associated with great high morbidity whilst the BSI is the leading cause of mortality. This retrospective study evaluated the incidence of CMVr and BSI, identified associated risk factors, assessed their impact on survival in allo-HSCT recipients during the first 100 days after transplantation. The study comprised 500 allo-HSCT recipients who were CMV DNA-negative and CMV IgG-positive before allo-HSCT. Amongst them, 400 developed CMVr and 75 experienced BSI within 100 days after allo-HSCT. Multivariate regression revealed that graft failure and acute graft-versus-host disease were significant risk factors for poor prognosis, whereas CMVr or BSI alone were not. Amongst all 500 patients, 56 (14%) developed both CMVr and BSI in the 100 days after HSCT, showing significantly reduced 6-month overall survival (p = 0.003) and long-term survival (p = 0.002). Specifically, in the initial post-transplant phase (within 60 days), BSI significantly elevate mortality risk, However, patients who survive BSI during this critical period subsequently experience a lower mortality risk. Nevertheless, the presence of CMVr in patients with BSI considerably diminishes their long-term survival prospects. This study provides real-world data on the impact of CMVr and BSI following transplantation on survival, particularly in regions such as China, where the prevalence of CMV IgG-positivity is high. The findings underscore the necessity for devising and executing focused prevention and early management strategies for CMVr and BSI to enhance outcomes for allo-HSCT recipients.

1 Introduction

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is an effective and intensive treatment for many haematological diseases, especially acute leukaemia. Nevertheless, post-allo-HSCT infection contributes to early mortality. The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) (2024) database shows that infection accounts for 19% and 28% of mortality within 100 days post-transplantation in matched-related and haploidentical HSCT amongst recipients aged over 18, respectively. Amongst various complications, bloodstream infection (BSI) and cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) are the two most common infections after allo-HSCT (Cho et al., 2019; Ljungman et al., 2019).

Several factors can influence the development of BSI, including immunodeficiency resulting from long-term myelosuppression and immunosuppression after allo-HSCT (Girmenia et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2018). Furthermore, CMV infection has been associated with myelosuppression. Various sources, such as in vitro studies, statistical analyses of clinical studies, patient case reports, and studies in murine models (Randolph-Habecker et al., 2002) collectively provide evidence of a reciprocal relationship between CMVr and BSI after allo-HSCT.

Infections following allo-HSCT are not typically observed in clinical practice as isolated events but frequently manifest in combination with other infections. Several studies have extensively explored the characteristics of BSI or CMVr after HSCT; some of these studies have indicated an association between CMVr and invasive fungal infections, Epstein–Barr virus reactivation, or hepatitis B virus reactivation (Liu et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). Nevertheless, a limited number of studies have delved into the relationship between CMVr and BSI shortly after HSCT. This study aimed to delineate the incidence of CMVr and BSI amongst patients who underwent allo-HSCT in the southeastern coastal region of China from March 2013 to May 2022. Additionally, it sought to elucidate the effects of BSI and CMVr occurring within the first 100 days after transplantation on recipient clinical outcomes.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and patient selection

This study constituted a multicentre, retrospective analysis of a patient cohort presenting with haematological disorders who underwent allo-HSCT in four hospitals across the Fujian Province of China over a 9-year period (March 2013 to May 2022). A total of 500 patients who underwent their first allo-HSCT were included, and their medical records were retrospectively reviewed. All the included patients, children and adults, were consecutive. Before participation in the study, all patients and donors provided informed consent. The research was conducted in accordance with and approved by the ethical standards of the local institutional review board (Medical Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, 2022KY167) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Transplantation procedures

Patients diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were treated with a standard myeloablative conditioning regimen. This regimen consisted of fludarabine (25 mg/m2/day intravenously on days −10 to −6), cytarabine (2 g/m2/day intravenously on days −10 to −6), busulfan (0.8 mg/kg/q6hr intravenously on days −6 to −4), cyclophosphamide (1.8 g/m2/day intravenously on days −3 to −2), semustine (250 mg/m2 orally on day −1), and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG; 7.5–10 mg/kg intravenously on days −5 to −2). Patients diagnosed with aplastic anaemia received fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day intravenously on days −5 to −2), cyclophosphamide (30 mg/kg/day intravenously on days −5 to −2), and ATG (2.5 mg/kg/day intravenously on days −4 to −2). All patients received a graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisting of cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and short-term methotrexate.

2.3 CMV therapy and monitoring

Testing for CMV was performed in plasma samples using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction with a CMV nucleic acid quantitative detection kit (DA-D061; Da An Gene Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). All centres employ the same CMV testing kit, along with identical detection procedures and instruments. CMV screening started from the first day after transplantation, twice a Week. All patients received prophylactic acyclovir (5 mg/kg, every 8 h) from days 1 to 100. CMVr was defined as a viral load of >500 copies/mL on two consecutive readings 5 days apart (Mo et al., 2022). The time of CMVr refers to the duration from allo-HSCT to the occurrence of CMVr. Preemptive therapy with either intravenous foscarnet (90 mg/kg/day) or intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg, twice daily) was initiated upon confirmation, if the CMV viral load continues to increase after 2 weeks of ganciclovir continuous treatment, we switch to valganciclovir (900 mg, twice daily) or foscarnet (120 mg/kg/day) for treatment, therapy was continued until CMV DNA was no longer detected in two consecutive tests.

2.4 Definition and management of BSI

BSI was defined as an infection resulting from a bacterial or fungal pathogen isolated from at least one blood culture. In the case of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus infection or common skin contaminants, a minimum of two positive blood cultures were required (Frère et al., 2004; Cappellano et al., 2007). Blood cultures were obtained when signs of infection, typically manifesting as fever (oral temperature of ≥38°C), were observed. All suspected infected catheters were aseptically removed, and catheter tips were cultured to confirm catheter-related BSI. Prophylaxis for fungal infection included primary prophylaxis for patients without a prior history of invasive fungal infection (IFD) and secondary prophylaxis for patients with a prior history of IFD. Primary prophylaxis consisted of oral posaconazole or itraconazole from day −10 to day +100 after transplant. Secondary prophylaxis involves the use of antifungal medications that have been effective in the patient’s previous treatment from −10 days to +100 days post-transplantation. No antibacterial prophylaxis was conducted before transplantation. All patients with febrile neutropenia were treated promptly with empiric intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics until the results of the blood and catheter tip cultures were known, following current guidelines (Tomblyn et al., 2009; Averbuch et al., 2013a,b; Heinz et al., 2017).

2.5 Statistical analyses

The analysis of the data encompassed several variables aimed at identifying risk factors for CMV and BSI: age, sex, underlying diseases, disease status at transplantation, donor type, conditioning regimen, presence of acute GVHD (aGVHD), ATG dose and BSI. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to calculate survival and the cumulative incidence of CMV infection and BSI. We performed landmark analyses for all endpoints by dividing the entire 3,400-day follow-up period into the first 60 days and subsequent 3,340 days. Differences between the two survival curves were estimated using a log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to identify prognostic factors for CMVr and BSI. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 for p-values. All statistical analyses were performed using R (4.3.0) and Prism 8 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States) software.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of patients undergoing allo-HSCT

Five patients with CMV DNA levels of >103 copies/mL before allo-HSCT were excluded from further analysis. In this study, we enrolled 500 patients, all of whom, including both donors and recipients, were CMV IgG-positive before transplantation. The stem cells were all derived from bone marrow and peripheral blood; there were no patients who underwent umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation. The cohort comprised 64.8% (n = 324) men and 35.2% (n = 176) women, with a median age of 26 (IQR 12–40) years. More than half of the patients were diagnosed with acute leukaemia (41.6% with acute myeloid leukaemia and 23% with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia). Other diseases included chronic myeloid leukaemia, severe aplastic anaemia, MDS, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and congenital immune deficiency. A myeloablative conditioning regimen was administered to 77.2% (n = 386) of the patients, and an ATG dose of ≥7.5 mg/kg was administered to 89.6% (n = 448). Amongst the 500 patients, the types of HSCT donors included 355 (71%) haploidentical donors, 101 (20.2%) HLA-matched siblings, and 44 (8.8%) unrelated donors. Neutrophil engraftment was achieved in 97% (n = 485) of patients, and the median time to absolute neutrophil count recovery was 13 (IQR: 12–16) days. Platelet engraftment occurred in 92% (n = 460) of the patients, with a median time to platelet recovery of 15 (IQR: 12–19) days. The overall incidence of acute GVHD (grades I–IV) was 33.2% (n = 166), whereas that of severe acute GVHD (grades III–IV) was 18.8% (n = 94). The median follow-up time was 606 (IQR: 170–1,433) days. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of all participants.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Total |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 26 (12, 40) |

| Patient Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 324 (64.8%) |

| Female | 176 (35.2%) |

| Disease, n (%) | s |

| AML | 208 (41.6%) |

| ALL | 115 (23%) |

| MDS | 32 (6.4%) |

| CML | 25 (5%) |

| AA | 79 (15.8%) |

| AITL | 7(1.4%) |

| Lymphoma | 17(3.4%) |

| Other | 17(3.4%) |

| Pretreatment status, n (%) | |

| RIC | 114 (22.8%) |

| MAC | 386 (77.2%) |

| ATG dose, n (%) | |

| 5 mg/kg | 52 (10.4%) |

| 7.5 mg/kg | 196 (39.2%) |

| 10 mg/kg | 252 (50.4%) |

| HLA-matching status, n (%) | |

| Mismatch | 355 (71%) |

| Match | 101(20.2%) |

| Unrelated donor | 44 (8.8%) |

| Neutrophil engraftment, n (%) | |

| Engraftment | 485 (97%) |

| Failure | 15 (3%) |

| Neutrophil count recovery (day), median (IQR) | 13 (12–16) |

| PLT engraftment, n (%) | |

| Engraftment | 460 (92%) |

| Failure | 40 (8%) |

| PLT count recovery (day), median (IQR) | 15 (12–19) |

| aGVHD, n (%) | |

| No aGVHD | 334 (66.8%) |

| Grade I-II | 72 (14.4%) |

| Grade III-IV | 94 (18.8%) |

| CMVr | |

| No CMVr | 100 (20%) |

| CMVr | 400 (80%) |

| BSI | |

| No BSI | 425(81.2%) |

| BSI | 75(18.8%) |

| CMVr Time (day)*, median (IQR) | 32 (24, 41) |

| Follow-up time (day), median (IQR) | 606 (170, 1,433) |

Baseline characteristics of patients receiving allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST).

IQR, Interquartile Range; AML, Acute Myeloid Leukaemia; ALL, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia; MDS, Myelodysplastic Syndromes; CML, Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia; AA, Aplastic Anaemia; AITL, Angioimmunoblastic T-cell Lymphoma; PLT, Platelets; aGVHD, acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease; RIC, Reduced-Intensity Conditioning; MAC, Myeloablative conditioning; CMVr, Cytomegalovirus reactivation; CMVr Time*, The duration from haematopoietic stem cell transplantation to the occurrence of CMVr; CMVr duration time*, The time from CMV reactivation to CMV clearance.

3.2 CMV reactivation and BSI development in allo-HSCT

Of the 500 patients who underwent allo-HSCT, 400 (80%) experienced CMVr within the first 100 days after allo-HSCT. The median time to CMVr occurrence was 32 (IQR: 24–41) days. The median duration of CMV viraemia was 31 (IQR: 24–41) days (Table 1). Within 100 days after HSCT, CMV was cleared in 77.8% (n = 311) of the patients, with a median time of 67 (IQR: 53–90) days and the median time of duration of CMVr was 42 (IQR: 27–77) days (Table 2). Amongst all 500 patients, 75 (18.8%) developed BSI, of whom 56 experienced CMVr within the first 100 days. A total of 70 different strains were detected in these patients. Blood culture specimens from 43 patients showed the presence of a single pathogen, whilst 12 showed two pathogens, and one showed three pathogens. The detection rate of Gram-negative bacteria was 56%, with predominant pathogens being Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli. Gram-positive bacteria were detected in 34.7% of cases, with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus being the main species. Additionally, fungi were detected in 6 cases, as shown in Supplementary Table 1. Of the 75 patients with BSI, 35 (46.7%) were found to have multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infection. The predominant MDR bacteria were mainly Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, with the Extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing (ESBL+) strains had the highest resistance rate 16 (21.3%), as showed in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2

| Characteristics | CMVr | No CMVr | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 400 | N = 100 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 26 (13, 40) | 25 (11, 39.25) | 0.851 |

| Disease, n (%) | 0.056 | ||

| AA | 64 (16%) | 15 (15%) | |

| AML | 165 (41.2%) | 43 (43%) | |

| MDS | 24 (6%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Lymphoma | 17 (4.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| CML | 15 (3.8%) | 10 (10%) | |

| ALL | 94 (23.5%) | 21 (21%) | |

| Other | 16 (4%) | 1 (1%) | |

| AITL | 5 (1.2%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | 0.107 | ||

| Not CR | 200 (50%) | 59 (59%) | |

| CR | 200 (50%) | 41 (41%) | |

| Donor Sex, n (%) | 0.135 | ||

| Male | 264 (66%) | 58 (58%) | |

| Female | 136 (34%) | 42 (42%) | |

| HLA-matching status, n (%) | 0.079 | ||

| Unrelated donor | 39 (9.8%) | 5 (5%) | |

| Mismatch | 287 (71.8%) | 68 (68%) | |

| Match | 74 (18.5%) | 27 (27%) | |

| MNC, median (IQR) | 7.955 (6.4, 11.08) | 7.8 (5.98, 11.592) | 0.663 |

| CD34, median (IQR) | 4.295 (2.8975, 7.44) | 3.75 (2.7, 7.795) | 0.574 |

| Neutrophil engraftment, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Engraftment | 398 (99.5%) | 87 (87%) | |

| Failure | 2 (0.5%) | 13 (13%) | |

| Neutrophil engraftment time, median (IQR) | 13 (12, 16) | 13 (12, 16.5) | 0.397 |

| PLT engraftment, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Engraftment | 379 (94.8%) | 81 (81%) | |

| Failure | 21 (5.2%) | 19 (19%) | |

| PLT engraftment time, median (IQR) | 15 (12, 19) | 14 (12, 18) | 0.122 |

| aGVHD, n (%) | 0.574 | ||

| Grade I–II | 55 (13.8%) | 17 (17%) | |

| Grade III–IV | 78 (19.5%) | 16 (16%) | |

| No GVHD | 267 (66.8%) | 67 (67%) | |

| Pretreatment, n (%) | 0.070 | ||

| RIC | 98 (24.5%) | 16 (16%) | |

| MAC | 302 (75.5%) | 84 (84%) | |

| ATG dose, n (%) | 0.004 | ||

| 7.5 mg/kg | 216 (54%) | 36 (36%) | |

| 10 mg/kg | 143 (35.8%) | 53 (53%) | |

| 5 mg/kg | 41 (10.2%) | 11 (11%) | |

| BSI, n (%) | 0.210 | ||

| BSI | 56 (14%) | 19 (19%) | |

| No BSI | 344 (86%) | 81 (81%) | |

| CMV cleared status*, n (%) | |||

| Clear | 311 (77.8%) | ||

| Unclear | 89 (22.2%) | ||

| Time to clear CMV (day), median (IQR) | 67 (53, 90) | ||

| Duration of CMVr (day), median (IQR) | 42 (27, 77) | ||

| Follow up time (day), median (IQR) | 633.5 (184.75, 1376.5) | 388 (76.75, 2,148) | 0.306 |

Baseline characteristics of all patients in the cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) and no-CMVr groups.

CMVr, Cytomegalovirus Reactivation; BSI, Bloodstream Infection; IQR, Interquartile Range; AML, Acute Myeloid Leukaemia; ALL, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia; MDS, Myelodysplastic Syndromes; CML, Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia; AA, Aplastic Anaemia; AITL, Angioimmunoblastic T-cell Lymphoma; Not CR, partial response, stable disease (SD), and progressive disease; CR, Complete Response; MNC, Mononuclear Cell; PLT, Platelets; aGVHD, acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease; MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning; RIC, Reduced-Intensity Conditioning; ATG dose, Anti-Thymocyte Globulin dose; CMV Cleared status*, CMV cleared within 100 days after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

3.3 Risk factors in patients with HSCT

Cox regression analysis of survival in 500 patients undergoing allo-HSCT was used to identify significant factors related to OS. Neutrophil (p < 0.001; HR 25.19 [95% CI 10.135–62.585]) and platelet engraftment failure (p < 0.001; HR 3.505 [95% CI 1.990–6.175]), as well as grade I–II aGVHD (p = 0.022; HR: 1.841 [95% CI 1.091–3.107]) and grade III–IV aGVHD (p < 0.001; HR: 3.399 [95% CI 2.221–5.202]), were significant predictors of OS. Notably, CMVr was not identified as a risk factor for OS in the competing risk model (p > 0.05). Table 3 summarises the hazards for OS after allo-HSCT.

Table 3

| Characteristics | Total (N) | Univariate analysis | p-value | Multivariate analysis | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Patient age | 500 | 0.016 | |||

| <18 | 137 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥18 | 363 | 1.651 (1.075–2.537) | 0.022 | 1.447 (0.915–2.288) | 0.114 |

| Patient sex | 500 | 0.829 | |||

| Male | 324 | Reference | |||

| Female | 176 | 0.961 (0.670–1.379) | 0.830 | ||

| Disease | 500 | 0.027 | |||

| Acute leukaemia | 355 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-acute leukaemia | 145 | 0.636 (0.419–0.966) | 0.034 | 0.838 (0.439–1.598) | 0.592 |

| Disease status | 500 | 0.104 | |||

| CR | 241 | Reference | |||

| Not CR | 259 | 1.331 (0.941–1.881) | 0.106 | ||

| Donor sex | 500 | 0.778 | |||

| Male | 322 | Reference | |||

| Female | 178 | 0.950 (0.664–1.360) | 0.779 | ||

| Donor age | 500 | 0.070 | |||

| <18 | 40 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥18 | 460 | 1.974 (0.870–4.479) | 0.104 | 1.003 (0.429–2.347) | 0.995 |

| HLA-match | 500 | 0.095 | |||

| Unrelated donor | 44 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Match | 101 | 0.691 (0.326–1.463) | 0.334 | 0.660 (0.299–1.454) | 0.303 |

| Mismatch | 355 | 1.163 (0.624–2.167) | 0.634 | 0.556 (0.281–1.101) | 0.092 |

| Donor-recipient blood type | 500 | 0.361 | |||

| Match | 319 | Reference | |||

| Major mismatched | 59 | 1.450 (0.897–2.343) | 0.129 | ||

| Minor mismatched | 90 | 0.845 (0.518–1.378) | 0.500 | ||

| Minor and Major mismatched | 32 | 1.145 (0.575–2.279) | 0.701 | ||

| MNC | 500 | 0.973 (0.935–1.012) | 0.166 | ||

| CD34 | 500 | 0.995 (0.961–1.031) | 0.801 | ||

| Neutrophil engraftment | 500 | <0.001 | |||

| Engraftment | 485 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Failure | 15 | 51.597 (27.663–96.241) | <0.001 | 25.186 (10.135–62.585) | <0.001 |

| PLT engraftment | 500 | <0.001 | |||

| Engraftment | 460 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Failure | 40 | 11.879 (7.983–17.676) | <0.001 | 3.505 (1.990–6.175) | <0.001 |

| aGVHD | 500 | <0.001 | |||

| No aGVHD | 330 | Reference | Reference | ||

| aGVHD I–II | 77 | 1.688 (1.044–2.730) | 0.033 | 1.841 (1.091–3.107) | 0.022 |

| aGVHD III–IV | 93 | 3.423 (2.339–5.008) | <0.001 | 3.399 (2.221–5.202) | <0.001 |

| BSI | 500 | <0.001 | |||

| No-BSI | 425 | Reference | Reference | ||

| BSI | 75 | 2.957 (2.026–4.316) | <0.001 | 1.936 (0.974–3.847) | 0.060 |

| CMVr | 500 | 0.001 | |||

| CMVr | 400 | Reference | Reference | ||

| No-CMVr | 100 | 1.914 (1.309–2.801) | <0.001 | 1.229 (0.528–2.860) | 0.633 |

| CMVr time | 500 | 1.010 (1.005–1.016) | <0.001 | 1.004 (0.992–1.015) | 0.519 |

| Pretreatment | 500 | 0.001 | |||

| RIC | 114 | Reference | Reference | ||

| MAC | 386 | 2.135 (1.282–3.554) | 0.004 | 1.519 (0.659–3.503) | 0.327 |

| ATG dose | 500 | 0.024 | |||

| 5 mg/kg | 52 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 7.5 mg/kg | 252 | 1.636 (0.783–3.422) | 0.191 | 2.115 (0.879–5.085) | 0.094 |

| 10 mg/kg | 196 | 2.301 (1.103–4.803) | 0.026 | 2.155 (0.924–5.025) | 0.075 |

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for overall survival (OS) after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST).

CMVr, Cytomegalovirus Reactivation; BSI, Bloodstream Infection; IQR, Interquartile Range; Not CR, partial response, stable disease (SD), and progressive disease; CR, Complete Response; MNC, Mononuclear Cell; PLT, Platelets; aGVHD, acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease; MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning; RIC, Reduced-Intensity Conditioning; ATG dose, Anti-Thymocyte Globulin dose.

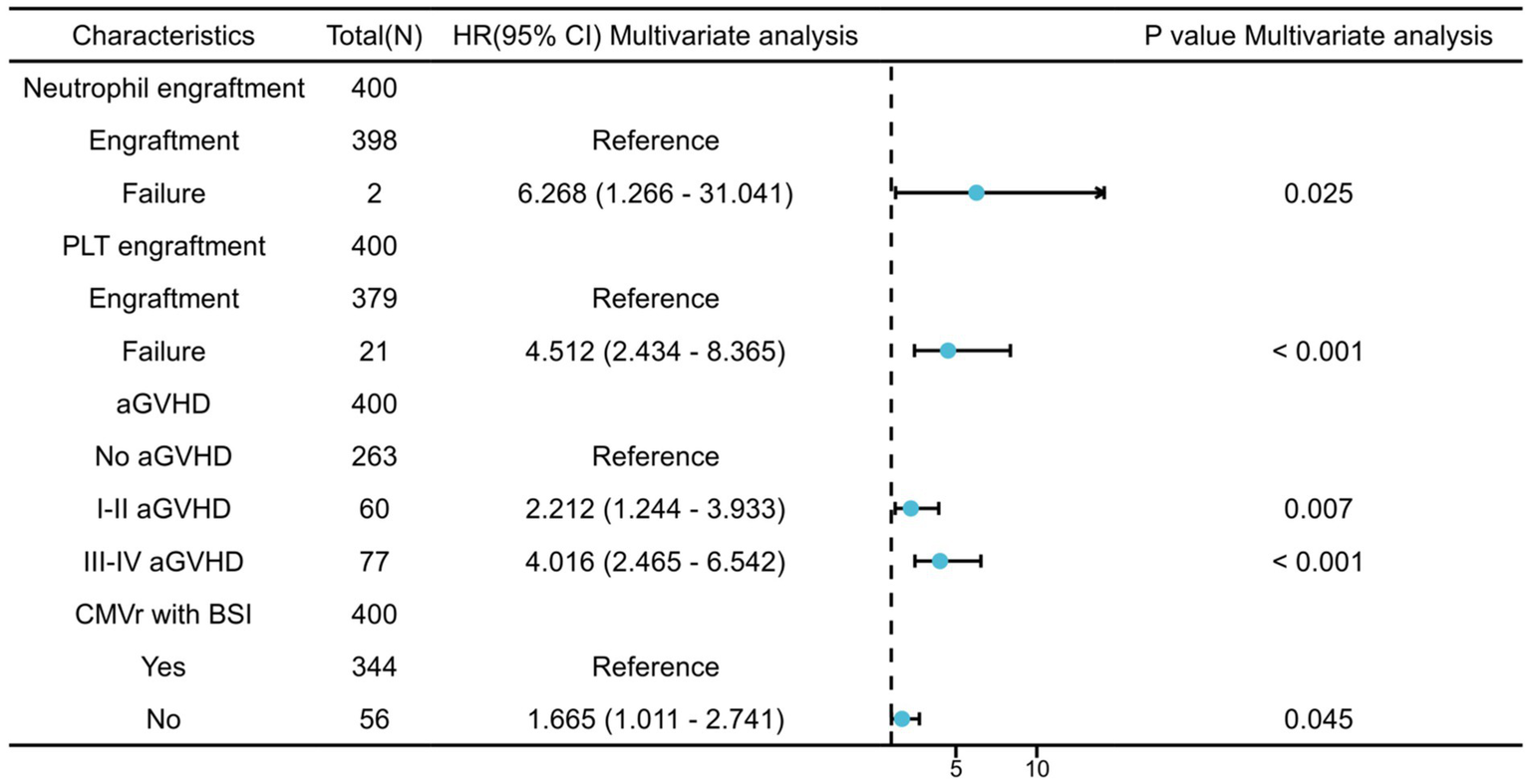

We further analysed the risk factors leading to mortality in patients with CMVr. Specifically, neutrophil engraftment failure (p = 0.025; hazard ratio (Heinz et al., 2017) 6.268 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.266–31.041]) and platelet engraftment failure (p < 0.001; HR 4.512 [95% CI 2.434–8.365]), as well as grade I–II aGVHD (p = 0.007; HR 2.212 [95% CI 1.244–3.933]) and grade III–IV aGVHD (p < 0.001; HR 4.016 [95% CI 2.465–6.542]), were identified as significant risk factors for overall survival (OS). Additionally, CMVr with BSI (p = 0.045; HR 1.665 [95% CI 1.011–2.741]) was also a significant risk factor for OS in the CMVr patients. Figure 1 summarises the factors related to OS in CMVr.

Figure 1

Risk factors for overall survival in patients with cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

3.4 Landmark analysis the impact of CMVr and BSI on post-transplantation survival

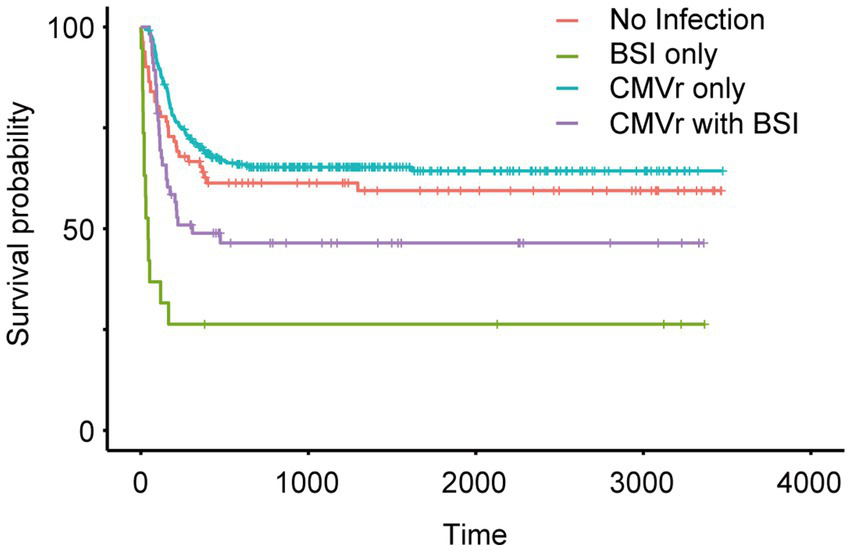

To investigate the impact of BSI and CMVr on the survival of HSCT patients, we categorised all patients into four groups (based on infections within first 100 days after transplantation): (1) no infection; (2) BSI only; (3) CMVr only; (4) CMVr with BSI. Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival outcomes indicated that the CMVr-only group had the best survival, followed by the no-infection group and CMVr with BSI group. The BSI-only group demonstrated the lowest survival (Figure 2). Notably, survival curves demonstrated a crossover around 60 days. A significant early decline in survival was observed for the BSI-only group and CMVr with BSI group during the immediate post-transplantation period, which was not observed in other groups. It seems that the influence of BSI on OS ‘outshines’ the CMVr variable considerably and distorts the results.

Figure 2

Kaplan–Meier analysis of long-term survival in all patients after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST).

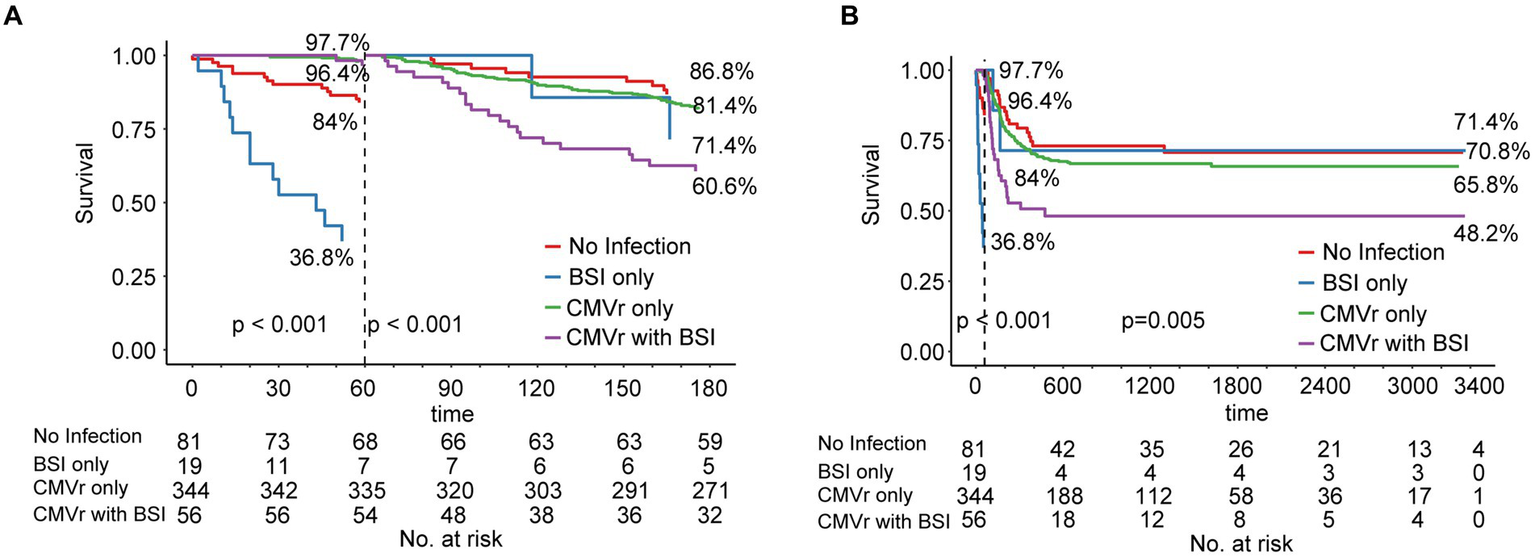

Due to changes in death risk of BSI and CMVr over different follow-up time intervals, we employed landmark analysis to separately analyse the data in different time periods, with 60 days post-transplantation as the landmark time point. During the first 6 months after transplantation, the OS for the CMVr with BSI group exhibited significant fluctuations, with a decrease from 96.45% before 60 days after transplantation to 60.6% thereafter. Notably, within the initial 60 days after transplantation, the BSI-only group demonstrated the lowest survival, with an OS of 36.8%. This improved to 71.4% after 60 days, whilst the OS for the CMVr with BSI group reduced to 60.6% (Figure 3A). After 60 days following transplantation, the OS for the BSI-only group remained at 71.4%, the OS for the CMVr-only group decreased to 65.8%, and the OS of the CMVr with BSI group showed a marked decline in survival to 48.2% (Figure 3B). This suggests that the risk of BSI-related mortality is high within the first 60 days post HSCT, but decreases significantly if the patient survives beyond this period. However, for patients with concurrent CMVr, the risk of mortality increases substantially after 60 days post-transplantation. Meanwhile, we attempted to use 30 days post-transplantation as the landmark time point, but the results did not reveal a turning time point of BSI survival (Supplementary Figures 1A,B).

Figure 3

(A) Landmark analysis of overall survival for all patients within 180 days after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST); landmark point set at 60 days after transplantation; p < 0.001 before and after 60 days; (B) Landmark analysis of overall survival for all patients after allo-HSCT patients in long-term follow-up; landmark point set at 60 days after transplantation; before 60 days, p < 0.001; after 60 days, p = 0.005.

An analysis of baseline data across the four groups indicated poor neutrophil and platelet engraftment in the BSI group. In the BSI-only group, neutrophil engraftment failure occurred in 26.3% of patients, and platelet engraftment failure occurred in 42.1% of patients, significantly higher than the rates in the CMVr-only group (0.6 and 4.1%, respectively) and the CMVr with BSI group (0% and 12.5%, respectively; characteristics summarised in Table 4). The elevated mortality rate in the BSI group during the initial post-transplantation period may be linked to this suboptimal engraftment.

Table 4

| Characteristics | No Infection | BSI-only | CMVr-only | CMVr with BSI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 81 | N = 19 | N = 344 | N = 56 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 24 (10, 37) | 33 (20, 49.5) | 26 (12, 40) | 26 (17.75, 37.5) | 0.183 |

| Patient Sex, n (%) | 0.250 | ||||

| Male | 59 (72.8%) | 14 (73.7%) | 218 (63.4%) | 33 (58.9%) | |

| Female | 22 (27.2%) | 5 (26.3%) | 126 (36.6%) | 23 (41.1%) | |

| Disease, n (%) | 0.326 | ||||

| AML | 33 (40.7%) | 10 (52.6%) | 143 (41.6%) | 22 (39.3%) | |

| ALL | 17 (21%) | 4 (21.1%) | 79 (23%) | 15 (26.8%) | |

| Other | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (4.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | |

| MDS | 6 (7.4%) | 2 (10.5%) | 20 (5.8%) | 4 (7.1%) | |

| AA | 12 (14.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 57 (16.6%) | 7 (12.5%) | |

| CML | 10 (12.3%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (3.8%) | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Lymphoma | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (3.8%) | 4 (7.1%) | |

| AITL | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | 0.083 | ||||

| CR | 37 (45.7%) | 4 (21.1%) | 170 (49.4%) | 30 (53.6%) | |

| Not CR | 44 (54.3%) | 15 (78.9%) | 174 (50.6%) | 26 (46.4%) | |

| HLA-matching status, n (%) | 0.382 | ||||

| Mismatch | 55 (67.9%) | 13 (68.4%) | 246 (71.5%) | 41 (73.2%) | |

| Match | 23 (28.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 64 (18.6%) | 10 (17.9%) | |

| Unrelated donor | 3 (3.7%) | 2 (10.5%) | 34 (9.9%) | 5 (8.9%) | |

| MNC, median (IQR) | 8.11 (6.19, 11.7) | 6.72 (5.61, 9.60) | 7.955 (6.4, 11.31) | 7.855 (6.45, 10.54) | 0.298 |

| CD34, median (IQR) | 4.04 (2.71, 7.93) | 3.47 (2.67, 6.2) | 4.15 (2.92, 7.46) | 4.725 (2.78, 6.37) | 0.712 |

| Neutrophil engraftment, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Failure | 8 (9.9%) | 5 (26.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Engraftment | 73 (90.1%) | 14 (73.7%) | 342 (99.4%) | 56 (100%) | |

| Neutrophil engraftment time, median (IQR) | 12 (12, 16) | 16 (15, 19) | 13 (11, 16) | 15 (12.75, 18) | <0.001 |

| PLT engraftment, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Failure | 11 (13.6%) | 8 (42.1%) | 14 (4.1%) | 7 (12.5%) | |

| Engraftment | 70 (86.4%) | 11 (57.9%) | 330 (95.9%) | 49 (87.5%) | |

| PLT engraftment time, median (IQR) | 13 (12, 16.75) | 21 (16, 24.5) | 14 (12, 19) | 17 (14, 21) | <0.001 |

| aGVHD, n (%) | 0.756 | ||||

| No GVHD | 54 (66.7%) | 13 (68.4%) | 232 (67.4%) | 35 (62.5%) | |

| Grade III–IV | 12 (14.8%) | 4 (21.1%) | 64 (18.6%) | 14 (25%) | |

| Grade I–II | 15 (18.5%) | 2 (10.5%) | 48 (14%) | 7 (12.5%) | |

| Pretreatment, n (%) | 0.304 | ||||

| MAC | 68 (84%) | 16 (84.2%) | 258 (75%) | 44 (78.6%) | |

| RIC | 13 (16%) | 3 (15.8%) | 86 (25%) | 12 (21.4%) | |

| ATG dose, n (%) | 0.044 | ||||

| 10 mg/kg | 45 (55.6%) | 8 (42.1%) | 121 (35.2%) | 22 (39.3%) | |

| 7.5 mg/kg | 27 (33.3%) | 9 (47.4%) | 187 (54.4%) | 29 (51.8%) | |

| 5 mg/kg | 9 (11.1%) | 2 (10.5%) | 36 (10.5%) | 5 (8.9%) |

Baseline characteristics of patients in the no-infection, bloodstream infection (BSI)-only, cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr)-only, and CMVr with BSI groups.

CMVr, Cytomegalovirus reactivation; BSI, Bloodstream infection; IQR, Interquartile range; AML, Chronic myeloid leukaemia; AA, Aplastic anaemia; AITL, Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; Not CR, partial response, stable disease (SD), and progressive disease; CR, Complete response; MNC, Mononuclear Cell; PLT, Platelets; aGVHD, acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease; MAC, Myeloablative Conditioning; RIC, Reduced-Intensity Conditioning; ATG dose, Anti-Thymocyte Globulin dose.

Dividing all 500 patients into CMVr and No-CMVr groups, landmark analysis was conducted to assess the impact of CMVr on survival. Within the first 60 days post-transplantation, the No-CMVr group exhibited poorer survival compared to the CMVr group (Supplementary Figure 2A). Baseline analysis comparing the two groups, as shown in Table 2, revealed a significantly higher proportion of neutrophil engraftment failure patients in the No-CMVr group (p < 0.001). Additionally, analysis of causes of death within the first 60 days post-transplantation showed that the proportion of infection-related deaths in the No-CMVr group reached 76%, significantly higher than that in the CMVr group (Supplementary Table 3). Therefore, the atypical finding of decreased survival in the No-CMVr group within the first 60 days post-transplantation is attributed to the increased probability of pathogenic infections due to neutropenia. However, from the 60 days post-HSCT to the long-term follow up, the no-CMVr group showed a trend towards better survival than the CMVr group, although this was not significant (p = 0.18; Supplementary Figure 2B).

To evaluate the occurrence of combined BSI and CMVr on patient survival within the first 100 days after transplantation, we categorised patients with CMVr into two groups: (1) CMVr with BSI (n = 56) and (2) CMVr without BSI (n = 344). The characteristics are summarised in Supplementary Table 4. The 6-month OS and long-term survival were lower in the CMVr with BSI group than in the CMVr without BSI group (Supplementary Figures 3A,B).

To further exclude the influence of GVHD on the survival of that CMVr with BSI, we selected the patient without aGVHD and divided them into CMVr with BSI and CMVr without BSI. The results were consistent with those obtained previously, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 4. The CMVr without BSI group demonstrated significantly better survival than the CMVr with BSI group (p = 0.0347).

3.5 Risk factors for BSI in patients with CMVr

After 60 days post-transplantation, there was a significant decrease in survival for CMVr with BSI patients. Subsequently, we further conducted logistic regression analysis to analyse the risk factors for BSI in patients with CMVr. Variables associated with BSI after HSCT were previously reported to include a diagnosis of acute leukaemia and MDS, transplantation from an HLA-mismatched donor and cord blood, an interval from diagnosis to HSCT of ≥190 days, carbapenem therapy, grade 3–4 intestinal mucositis, older age, and the duration of severe neutropenia (Girmenia et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2019). Therefore, we selected age, sex, donor origin, intensive conditioning regimen, total body irradiation, ATG dose, and aGVHD severity for logistic regression analysis. This revealed that the time to platelet engraftment (odds radio [OR] 1.007, 95% CI 1.002–1.012, p = 0.007) was associated with BSI after HSCT in patients with CMVr. Multivariate analysis identified the time to platelet engraftment (OR 1.007, 95% CI 1.002–1.012, p = 0.007) as an independent risk factor for BSI within 100 days after allo-HSCT (Table 5).

Table 5

| Characteristics | Total (N) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Patient age (years) | 400 | ||||

| <18 | 107 | Reference | |||

| ≥18 | 293 | 1.112 (0.462–1.762) | 0.750 | ||

| Patient sex | 400 | ||||

| Male | 251 | Reference | |||

| Female | 149 | 1.206 (0.630–1.782) | 0.524 | ||

| Disease | 400 | ||||

| No Acute leukaemia | 119 | Reference | |||

| Acute leukaemia | 281 | 0.967 (0.352–1.582) | 0.915 | ||

| Disease status | 400 | ||||

| CR | 201 | Reference | |||

| Not CR | 199 | 0.857 (0.291–1.423) | 0.592 | ||

| Donor sex | 400 | ||||

| Male | 265 | Reference | |||

| Female | 135 | 1.106 (0.516–1.697) | 0.738 | ||

| Donor age(years) | 400 | ||||

| <18 | 32 | Reference | |||

| ≥18 | 368 | 1.626 (0.403–2.850) | 0.436 | ||

| HLA-match | 400 | ||||

| Unrelated donor | 39 | Reference | |||

| Match | 74 | 1.062 (−0.089–2.214) | 0.918 | ||

| Mismatch | 287 | 1.133 (0.138–2.129) | 0.805 | ||

| MNC | 400 | 0.959 (0.889–1.029) | 0.238 | ||

| CD34 | 400 | 0.976 (0.907–1.046) | 0.500 | ||

| Time of neutrophil engraftment | 400 | 1.002 (0.984–1.020) | 0.796 | ||

| Time of PLT engraftment | 400 | 1.007 (1.002–1.012) | 0.007 | 1.007 (1.002–1.012) | 0.007 |

| aGVHD | 400 | ||||

| No aGVHD | 263 | Reference | |||

| I-II aGVHD | 60 | 1.036 (0.209–1.863) | 0.933 | ||

| III-IV aGVHD | 77 | 1.497 (0.815–2.179) | 0.246 | ||

| Pretreatment | 400 | ||||

| RIC | 98 | Reference | |||

| MAC | 302 | 1.222 (0.539–1.906) | 0.565 | ||

| ATG dose | 400 | ||||

| 5 mg/kg | 41 | Reference | |||

| 7.5 mg/kg | 216 | 1.117 (0.103–2.130) | 0.831 | ||

| 10 mg/kg | 143 | 1.309 (0.269–2.349) | 0.612 | ||

Logistic regression analysis of bloodstream infection (BSI) in patients with cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) within 100 days of allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST).

CMVr, Cytomegalovirus reactivation; BSI, Bloodstream infection; IQR, Interquartile range; Not CR, partial response, stable disease (SD), and progressive disease; CR, Complete response; MNC, Mononuclear cell; PLT, Platelets; aGVHD, acute graft-versus-host disease; MAC, Myeloablative conditioning; RIC, Reduced-intensity conditioning; ATG dose, Anti-thymocyte globulin dose.

4 Discussion

This study conducted a comprehensive evaluation of clinical outcomes and survival amongst a cohort of patients undergoing allo-HSCT. It assessed the impact of CMVr and BSI on patient survival at different times after transplantation and identified associated risk factors. This analysis has not yet been applied in large-scale population-based studies of allo-HSCT.

Previous studies have demonstrated a CMVr rate after HSCT ranging from approximately 30 to 70% (Schmidt-Hieber et al., 2013; Green et al., 2016; Styczynski et al., 2016; Teira et al., 2016; Maertens and Lyon, 2017; Schuster et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020). In our study, we observed a higher incidence of CMVr (76.04%) at 100 days after allo-HSCT. This elevated rate may be attributed to several factors, including the all patients in our cohort being CMV-IgG-positive and receiving higher doses of ATG during allo-HSCT. The pre-transplant seropositivity positive of recipient is identified as an independent risk factor for post-transplant CMV reactivation. In our study, all 500 patients and their donors tested positive for serological CMV IgG before transplantation. Considering the high prevalence of CMV infection in the southeastern coastal regions of China, where this study was conducted, it is not surprising that previous studies have not indicated CMVr rates exceeding 70% (Fang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2014). In China, a critical scarcity of HLA-matched donors leads most HSCT patients to receive haploidentical transplants (Xu et al., 2023). Consequently, patients with HLA mismatches represented more than 70% of our study cohort, with virtually all undergoing ATG treatment to GVHD. This contrasts sharply with the CIBMTR data, where HLA-mismatched donors constitute less than 5%, and ATG usage is below 30% (Teira et al., 2016). Valganciclovir, a prodrug of ganciclovir, has a bioavailability of 60%, markedly higher than ganciclovir’s 6.3%. If this initial treatment proves ineffective, we then consider switching to valganciclovir or foscarnet (Pescovitz et al., 2000). Ganciclovir or Foscarnet preemptive therapy can effectively prevent CMV end-organ disease, but this strategy does not reduce CMV DNAemia/antigenemia and its indirect impact on Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM; de la Camara, 2016). Recent studies indicate that Letermovir prophylactic treatment can inhibit clinically significant Cytomegalovirus infection in patients from any transplant source and is significantly associated with a reduction in NRM 6 months post-bone marrow transplantation (Toya et al., 2024). Thus, from April 2023, our centre began using Letermovir for CMV prophylaxis, but the number of patients was small and not included in the cohort of this study.

Most studies indicate that the median time for CMVr falls within the range of days +30 to +60 (Teira et al., 2016; Goldsmith et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2023). In this study, the median time for CMVr was days +32. Recent research indicates that the cumulative incidence of CMV infection reaches its peak and tends to stabilise around 60 days after HSCT (Huang et al., 2024). Therefore, this study chose days +60 as the landmark. Then, the survival rate of the BSI only group significantly decreased from day 0 to day +60, indicating that BSI significantly affects patient survival within 60 days after transplantation. Therefore, before 60 days post-transplantation, the impact of BSI and CMVr on survival is not on the same scale. To analyse the impact of CMVr with BSI on survival, we believe that choosing day +60 as a landmark to analyse the impact of CMVr with BSI on survival yields more rational results. This approach can exclude the issue where the influence of BSI on overall survival significantly ‘outshines’ the CMVr variable.

We observed that patients in the CMVr group seemed to have better survival than those without CMVr in the first 60 days after transplantation. However, baseline characteristics between the two groups showed better neutrophil engraftment in the CMVr group. Hence, the variance in survival rates during the initial 60-day period following transplantation could be ascribed to heightened mortality from infections in the no-CMVr cohort, stemming from inadequate neutrophil engraftment. Such fatalities may occur before the manifestation of CMVr.

After the initial 60 days after transplantation, the OS rate for patients without CMVr was 70.9%, slightly exceeding the 63.4% observed in the CMVr group. Whilst the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant, the findings align more closely with those of previous studies indicating a negative impact of CMVr on survival in patients after allo-HSCT (Teira et al., 2016). Several factors influence CMVr after allo-HSCT, including the serum status of CMV in donors and patients, the allo-HSCT regimen, and prophylactic medications. This difference from other studies may be attributed to the increased attention and standardisation in CMV detection, prevention, and treatment by transplant doctors. Prospective, multicentre, randomised controlled studies are required for confirmation.

One of the main contributions of this study was the investigation of the impact of CMVr and BSI on survival before and after 60 days after allo-HSCT. We observed a crossover between survival curves around 60 days after transplantation between the no-infection group and CMVr-only group, indicating that this time point may represent a critical juncture for the survival of patients with CMVr. The landmark analysis further demonstrated a decline in survival for patients with CMVr with or without BSI from 60 days after transplantation to long-term follow-up. Notably, patients with CMVr combined with BSI exhibited worse survival after 60 days following transplantation. In light of the commonality of infections and aGVHD following transplantation, Poutsiaka et al. (2011) identified a correlation between BSI and aGVHD. Given that GVHD is a significant risk factor for mortality after transplantation, we conducted further analyses to ascertain if aGVHD affected the survival rates in patients with CMVr and BSI 60 days after transplantation. This separate analysis revealed that the survival rates were significantly lower in the CMVr with BSI group than in the CMVr without BSI group.

Our findings suggest that the median time for CMVr is 32 days after transplantation. In our cohort, most cases of BSI occurred before CMVr, with only five cases of BSI occurring after CMVr amongst a cohort of 500 patients. We have yet to confirm the relationship between CMVr and BSI. However, previous studies showing that CMVr can indirectly affect engraftment and immunosuppression, potentially leading to concurrent bacterial or fungal infections (Chan and Logan, 2017; Cho et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2022).

Our study had some limitations that should be acknowledged. (1) For example, the retrospective design may have introduced bias and confounding factors beyond our control. (2) The timing of CMVr and BSI events was determined based on laboratory test results. However, BSI detection, conducted using blood culture, has a lower sensitivity and longer diagnostic time. Therefore, we could not accurately determine the duration of BSI and precisely calculate the proportion of simultaneous occurrence of BSI and CMVr. (3) We did not have complete data on antibiotic and steroid use because of which it was difficult to determine the risk factors associated with BSI occurrence. (4) Due to patient compliance and financial constraints, we were unable to collect data on T-cell recovery at various stages post-transplantation for all patients. (5) Due to limitations in medical resources, we cannot conduct tissue organ biopsies to diagnose CMV end-organ disease definitively. Diagnosis relies solely on clinical assessment rather than laboratory confirmation. Consequently, complete data on CMV disease in this cohort cannot be collected. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the impact of CMVr and BSI on survival within the context of stem cell implantation and transplantation. Future research should delve further into the mechanisms behind CMVr’s potential impact on immune function and infection risk.

In conclusion, our evaluation of CMVr and BSI following transplantation demonstrates that whilst CMVr alone does not compromise transplant prognosis, its concurrence with BSI markedly affects patient outcomes. Our findings indicate that patients afflicted with both CMVr and BSI shortly after transplantation face a significantly reduced survival rate beyond 60 days. In the initial post-transplant phase (within 60 days), the risk of mortality is heightened by BSIs, yet those who overcome BSIs during this period exhibit a decreased mortality risk thereafter. Nevertheless, the presence of CMVr in patients with BSI considerably diminishes their long-term survival prospects, underscoring the vital need for strategic preventive and early management measures targeting CMVr and BSIs. Therefore, in the clinical setting, it’s importance to focus on BSI monitoring in the first 60 days following transplantation and subsequently, to focus on the detection and treatment of CMVr to enhance patient outcomes amongst allo-HSCT recipients.

Statements

Data availability statement

Original data have been deposited at Zenodo and are publicly available as of the date of publication https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10720246.

Ethics statement

The research was conducted by the ethical standards of the local institutional review board (the Medical Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, 2022KY167). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft. JX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CN: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. LL: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JL: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. QL: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JH: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. TY: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20419 and 82070177), Special Foundation of Marine Economic Development Program of Fujian Province (FJHJF-L-2022-3), Cooperation Project of Industry and University in Fujian Province (2022Y4013), Open Research Fund of Key Laboratory of Gastrointestinal Cancer (Fujian Medical University), Ministry of Education (FMUGIC-202102), and Startup Fund for Scientific Research Project of Fujian Medical University (2020QH2021, 2021QH2019, and 2022QH2211).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Guanbin Zhang for his guidance and support and thank Youran Zhuang for their editorial assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1405652/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1(A) Landmark analysis of overall survival for all patients within 180 days after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCST); landmark point set at 30 days after transplantation; before 30 days, p = 0.513; after 30 days, p < 0.001; (B) Landmark analysis of overall survival for all patients after allo-HSCT patients in long-term follow-up; landmark point set at 30 days after transplantation; before 30 days, p = 0.513; after 30 days, p = 0.001.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 2(A) Landmark analysis of overall survival for the cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) and no-CMVr groups within 180 days after transplantation; landmark point set at 60 days after transplantation; the p-values for both groups before and after 60 days are 0.002 and 0.163, respectively; (B) Landmark analysis of overall survival for the CMVr and no-CMVr groups in long-term follow-up; landmark point set at 60 days after transplantation; the p-values for both groups before and after 60 days are 0.002 and 0.18, respectively.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 3(A) The 180-day OS was lower in the cytomegalovirus reactivation (CMVr) with bloodstream infection (BSI) group than in the CMVr with no BSI group (58.9% vs. 78.9%, p = 0.0003, HR 3.244 [95% CI 1.763–5.968]); (B) Long-term survival was lower in the CMVr with BSI group than in the CMVr with no BSI group (58.9% vs. 79.6%, p = 0.0002, HR 3.131 [95% CI 1.688–5.808]).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 4Kaplan–Meier analysis of long-term survival in patients without acute GVHD (aGVHD).

References

1

Averbuch D. Cordonnier C. Livermore D. M. Mikulska M. Orasch C. Viscoli C. et al . (2013b). Targeted therapy against multi-resistant bacteria in leukemic and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: guidelines of the 4th European conference on infections in leukemia (ECIL-4, 2011). Haematologica98, 1836–1847. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091330

2

Averbuch D. Orasch C. Cordonnier C. Livermore D. M. Mikulska M. Viscoli C. et al . (2013a). European guidelines for empirical antibacterial therapy for febrile neutropenic patients in the era of growing resistance: summary of the 2011 4th European conference on infections in leukemia. Haematologica98, 1826–1835. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091025

3

Cappellano P. Viscoli C. Bruzzi P. Van Lint M. T. Pereira C. A. Bacigalupo A. (2007). Epidemiology and risk factors for bloodstream infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantion. New Microbiol.30, 89–99. PMID:

4

Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) . (2024). Available at:https://cibmtr.org/CIBMTR/Resources/Summary-Slides-Reports

5

Chan S. Logan A. (2017). The clinical impact of cytomegalovirus infection following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: why the quest for meaningful prophylaxis still matters. Blood Rev.31, 173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.01.002

6

Cho S. Y. Lee D. G. Kim H. J. (2019). Cytomegalovirus infections after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: current status and future immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20:2666. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112666

7

de la Camara R. (2016). CMV in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis8:e2016031. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2016.031

8

Ding Y. Ru Y. Song T. Guo L. Zhang X. Zhu J. et al . (2021). Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the prevalence and impacts on outcomes: EBV and CMV reactivation post Allo-HCT in NHL. Ann. Hematol.100, 2773–2785. doi: 10.1007/s00277-021-04642-5

9

Fan Z. Y. Han T. T. Zuo W. Zhao X. S. Chang Y. J. Lv M. et al . (2022). CMV infection combined with acute GVHD associated with poor CD8+ T-cell immune reconstitution and poor prognosis post-HLA-matched Allo-HSCT. Clin. Exp. Immunol.208, 332–339. doi: 10.1093/cei/uxac047

10

Fang F. Q. Fan Q. S. Yang Z. J. Peng Y. B. Zhang L. Mao K. Z. et al . (2009). Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection in Shanghai, China. Clin. Vaccine Immunol.16, 1700–1703. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00385-08

11

Frère P. Hermanne J. P. Debouge M. H. de Mol P. Fillet G. Beguin Y. (2004). Bacteremia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence and predictive value of surveillance cultures. Bone Marrow Transplant.33, 745–749. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704414

12

Girmenia C. Bertaina A. Piciocchi A. Perruccio K. Algarotti A. Busca A. et al . (2017). Incidence, risk factors and outcome of pre-engraftment gram-negative bacteremia after allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: an Italian prospective multicenter survey. Clin. Infect. Dis.65, 1884–1896. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix690

13

Goldsmith S. R. Abid M. B. Auletta J. J. Bashey A. Beitinjaneh A. Castillo P. et al . (2021). Posttransplant cyclophosphamide is associated with increased cytomegalovirus infection. a CIBMTR analysis. Blood, 137, 3291–3305. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009362

14

Green M. L. Leisenring W. Xie H. Mast T. C. Cui Y. Sandmaier B. M. et al . (2016). Cytomegalovirus viral load and mortality after haemopoietic stem cell transplantation in the era of pre-emptive therapy: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol3, e119–e127. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3026(15)00289-6

15

Heinz W. J. Buchheidt D. Christopeit M. von Lilienfeld-Toal M. Cornely O. A. Einsele H. et al . (2017). Diagnosis and empirical treatment of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in adult neutropenic patients: guidelines of the infectious diseases working party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann. Hematol.96, 1775–1792. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3098-3

16

Huang Y. C. Hsiao F. Y. Guan S. T. Yao M. Liu C. J. Chen T. T. et al . (2024). Ten-year epidemiology and risk factors of cytomegalovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect.57, 365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2024.02.005

17

Kim J. Hong S. Park W. Kim R. Kim M. Park Y. et al . (2020). Prognostic factors of cytomegalovirus retinitis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. PLoS One15:e0238257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238257

18

Li S. S. Zhang N. Jia M. Su M. (2022). Association between cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus co-reactivation and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12:818167. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.818167

19

Lin A. Brown S. Chinapen S. Lee Y. J. Seo S. K. Ponce D. M. et al . (2023). Patterns of CMV infection after letermovir withdrawal in recipients of posttransplant cyclophosphamide-based transplant. Blood Adv.7, 7153–7160. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010966

20

Liu Y. C. Lu P. L. Hsiao H. H. Chang C. S. Liu T. C. Yang W. C. et al . (2012). Cytomegalovirus infection and disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: experience in a center with a high seroprevalence of both CMV and hepatitis B virus. Ann. Hematol.91, 587–595. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1351-8

21

Ljungman P. de la Camara R. Robin C. Crocchiolo R. Einsele H. Hill J. A. et al . (2019). Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stem cell transplantation from the 2017 European conference on infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect. Dis.19, e260–e272. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30107-0

22

Maertens J. Lyon S. (2017). Current and future options for cytomegalovirus reactivation in hematopoietic cell transplantation patients. Future Microbiol.12, 839–842. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0095

23

Mo W. Chen X. Zhang X. Wang S. Li L. Zhang Y. (2022). The potential Association of Delayed T Lymphocyte Reconstitution within six Months Post-Transplantation with the risk of cytomegalovirus retinitis in severe aplastic Anemia recipients. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12:900154. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.900154

24

Pescovitz M. D. Rabkin J. Merion R. M. Paya C. V. Pirsch J. Freeman R. B. et al . (2000). Valganciclovir results in improved oral absorption of ganciclovir in liver transplant recipients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.44, 2811–2815. doi: 10.1128/Aac.44.10.2811-2815.2000

25

Poutsiaka D. D. Munson D. Price L. L. Chan G. W. Snydman D. R. (2011). Blood stream infection (BSI) and acute GVHD after hematopoietic SCT (HSCT) are associated. Bone Marrow Transplant.46, 300–307. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.112

26

Randolph-Habecker J. Iwata M. Torok-Storb B. (2002). Cytomegalovirus mediated myelosuppression. J. Clin. Virol.25, 51–56. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00092-6

27

Ren J. Lin Q. Chen W. Lin C. Zhang Y. Chen C. et al . (2019). G-CSF-primed haplo-identical HSCT with intensive immunosuppressive and myelosuppressive treatments does not increase the risk of pre-engraftment bloodstream infection: a multicenter case-control study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.38, 865–876. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03482-6

28

Schmidt-Hieber M. Labopin M. Beelen D. Volin L. Ehninger G. Finke J. et al . (2013). CMV serostatus still has an important prognostic impact in de novo acute leukemia patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a report from the acute leukemia working party of EBMT. Blood122, 3359–3364. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-499830

29

Schuster M. G. Cleveland A. A. Dubberke E. R. Kauffman C. A. Avery R. K. Husain S. et al . (2017). Infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: Results from the organ transplant infection project, a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Open Forum Infect. Dis.4:ofx050. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx050

30

Styczynski J. Czyzewski K. Wysocki M. Gryniewicz-Kwiatkowska O. Kolodziejczyk-Gietka A. Salamonowicz M. et al . (2016). Increased risk of infections and infection-related mortality in children undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared to conventional anticancer therapy: a multicentre nationwide study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect.22, 179.e1–179.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.017

31

Teira P. Battiwalla M. Ramanathan M. Barrett A. J. Ahn K. W. Chen M. et al . (2016). Early cytomegalovirus reactivation remains associated with increased transplant-related mortality in the current era: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood127, 2427–2438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-679639

32

Tomblyn M. Chiller T. Einsele H. Gress R. Sepkowitz K. Storek J. et al . (2009). Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: a global perspective. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant.15, 1143–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.06.019

33

Toya T. Mizuno K. Sakurai M. Kato J. Mori T. Doki N. et al . (2024). Differential clinical impact of letermovir prophylaxis according to graft sources: a KSGCT multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood Adv.8, 1084–1093. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010735

34

Xu L. P. Lu D. P. Wu D. P. Jiang E. L. Liu D. H. Huang H. et al . (2023). Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation activity in China 2020-2021 during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: a report from the Chinese blood and marrow transplantation registry group. Transplant Cell Ther29:136.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.11.011

35

Yan C. H. Wang Y. Mo X. D. Sun Y. Q. Wang F. R. Fu H. X. et al . (2018). Incidence, risk factors, microbiology and outcomes of pre-engraftment bloodstream infection after Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and comparison with HLA-identical sibling transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis.67, S162–S173. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy658

36

Zhang Q. Gao Y. Peng Y. Fu M. Liu Y. Q. Zhou Q. J. et al . (2014). Epidemiological survey of human cytomegalovirus antibody levels in children from southeastern China. Virol. J.11:123. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-123

37

Zhang Z. Li R. Chen Y. Zhang J. Zheng Y. Xu M. et al . (2022). Association between active cytomegalovirus infection and lung fibroproliferation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis.22:788. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07747-y

38

Zhou J. R. Shi D. Y. Wei R. Wang Y. Yan C. H. Zhang X. H. et al . (2020). Co-reactivation of cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus was associated with poor prognosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Front. Immunol.11:620891. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.620891

Summary

Keywords

allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, cytomegalovirus reactivation, bloodstream infection, haematological disease, acute myeloid leukaemia

Citation

Ren J, Xu J, Sun J, Wu X, Yang X, Nie C, Lan L, Zeng Y, Zheng X, Li J, Lin Q, Hu J and Yang T (2024) Reactivation of cytomegalovirus and bloodstream infection and its impact on early survival after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a multicentre retrospective study. Front. Microbiol. 15:1405652. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1405652

Received

23 March 2024

Accepted

29 May 2024

Published

19 June 2024

Volume

15 - 2024

Edited by

Axel Cloeckaert, Institut National de recherche pour l’agriculture, l’alimentation et l’environnement (INRAE), France

Reviewed by

Daniel Teschner, University Hospital Würzburg, Germany

Rafael De La Camara, Princess University Hospital, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Ren, Xu, Sun, Wu, Yang, Nie, Lan, Zeng, Zheng, Li, Lin, Hu and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Yang, yang.hopeting@gmail.comJianda Hu, drjiandahu@163.com

†These authors share first authorship

‡Lead contact

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.