Abstract

Introduction:

Ancient cryospheric environments may preserve overlooked reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and bioactive potential. This study reports the first whole-genome sequencing and functional characterization of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 isolated from 5,000-year-old ice from Scărișoara Ice Cave, revealing a multidrug-resistance phenotype alongside antimicrobial activity.

Methods:

Whole-genome sequencing combined with phenotypic characterization for extremotolerance, antibiotic susceptibility and biochemical profile were used to identify and functionally characterize the ancient Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3.

Results:

SC65A.3 is a polyextremophile, growing up to 15 °C and tolerating 1.9 M NaCl and 0.9 M MgCl₂. Phylogenetic analysis classified it within P. cryohalolentis. Functional assays showed broad hydrolytic activity and resistance to 10 antibiotics across 8 classes, including third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and rifampicin. Whole-genome analysis identified >100 AMR-associated genes, including clinically relevant determinants (e.g., ampC, gyrA, gyrB, parC, parE, dfrA, rpoB, tetA, tetC, and mcr-1), as well as multiple heavy-metal resistance and multidrug efflux genes. SC65A.3 inhibited 14 ESKAPE-group pathogens (including MRSA, Enterococcus faecium, Enterobacter sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii), consistent with genes linked to antimicrobial compounds such as glycopeptides and bacitracin. In addition, 45 stress-response genes related to cold/heat adaptation were detected, including distinctive htpX, htpG, and pka genes among cold-adapted Psychrobacter.

Discussion:

SC65A.3 represents an ancient, ice-adapted Psychrobacter with a dual profile of multidrug resistance and antimicrobial activity, highlighting ice caves as underexplored reservoirs of ancient resistomes and bioactive traits. To our knowledge, this is the first genome analysis of a Psychrobacter isolate from an ice cave and the first characterization of an ancient resistome from this environment, supporting future ecological, biotechnological, and medical exploration.

1 Introduction

With 20% of Earth’s surface comprising frozen habitats and low temperatures characterizing much of the biosphere, understanding cold-adapted microbes is increasingly critical in the context of rapid climate change (Margesin and Miteva, 2011; Yadav et al., 2017). Icy habitats serve as reservoirs for psychrophilic microorganisms representing a significant source of genomic diversity and novel microbial species, that exhibit remarkable stability and activity at low temperatures, holding promising applications in bio-nanotechnology and various industries (Priscu et al., 1998, 1999; Miteva et al., 2009; Anesio and Laybourn-Parry, 2012; Anesio et al., 2017; Mondini et al., 2022).

Recent studies have explored microbiomes in diverse cave systems (Bogdan et al., 2023; Gatinho et al., 2024; Jurado et al., 2024; Ogorek et al., 2024; Salazar-Hamm et al., 2025), including perennial ice deposits within caves (Paun et al., 2021; Mondini et al., 2022; Lange-Enyedi et al., 2024). However, investigations of cave-associated icy habitats remain comparatively sparse in contrast to the substantial literature on permafrost (Zhang et al., 2007; McCann et al., 2016; Rivkina et al., 2016; Abramov et al., 2021), polar ice sheets (Rehakova et al., 2010; Musilova et al., 2015; Mogrovejo et al., 2020; Kumar and Sharma, 2021), sea ice (Deming, 2009; Wing et al., 2012; Li et al., 2019a; Ozturk et al., 2022), glacial lakes (Murray et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016; Sharma and Kumar, 2017; Gupta et al., 2022), and snow (Bachy et al., 2011; Lopatina et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2022). Expanding research on cave ice deposits active microbiomes is essential to uncover their biodiversity, functional adaptations to geochemical and climatic variations, and their potential as a source of novel microbial strains and biomolecules for industrial and medical applications (Purcarea, 2018).

Scarisoara Ice Cave (Romania) is among the most extensively studied ice caves globally. Its 100,000 m3 perennial ice block, dated to approximately 13,000 years before present (BP), is one of the oldest and largest of its kind (Holmlund et al., 2005; Persoiu and Pazdur, 2010; Hubbard, 2017; Persoiu et al., 2017; Paun et al., 2019). The molecular approaches revealed that its perennial ice deposit hosts a rich and complex microbial community (Hillebrand-Voiculescu et al., 2013, 2014; Itcus et al., 2018; Mondini et al., 2019, 2022; Paun et al., 2019). The distribution of the microbial community appears to be influenced by the climatic conditions during ice formation and the organic carbon content within the ice substrate (Itcus et al., 2016, 2018; Brad et al., 2018; Mondini et al., 2019; Paun et al., 2019). Culture-based microbiological studies performed on Scarisoara Ice Cave allowed the isolation and characterization of psychrotrophic and psychrophilic bacterial strains (Paun et al., 2021).

In addition to their ecological and biotechnological relevance, microbial communities preserved in ancient ice deposits are also valuable for understanding the evolutionary history of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). AMR is an ancient, natural phenomenon, occurring long before clinical antibiotic use, with resistance mechanisms such as target alteration, drug efflux/influx control, and enzyme-mediated inactivation evolving over millions of years (Allen et al., 2010; D’Costa et al., 2011; Bhullar et al., 2012; Perry et al., 2016; Van Goethem et al., 2018; Morozova et al., 2022). However, this natural phenomenon has been accelerated by the huge selection pressure exerted by chronic antibiotic use, promoting antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) diversification and spreading through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Kaufmann and Hung, 2010; Kohanski et al., 2010; D’Costa et al., 2011; Thi et al., 2011; Meng et al., 2022). Today AMR is a global crisis undermining human and veterinary medicine, food security, and environmental health, demanding accelerated discovery of new antibiotics to contain infections and curb economic losses (Aslam et al., 2018; Lewis, 2020; Meng et al., 2022; Aggarwal et al., 2024; Naghavi et al., 2024). In a report from 2023, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) it was shown that the environment has a key role in AMR development, transmission and spread, and it was stipulated that “Prevention is at the core of the action and environment is a key part of the solution” (UNEP, 2023).

Resistance determinants are part of the natural microbial gene pool, and caves and permafrost environments represent reservoirs where ancient resistance mechanisms can be preserved and studied. This phenomenon often correlates with the metabolic diversity of microbial strains from extreme environments (Perkins and Nicholson, 2008; Allen et al., 2010), therefore, studies of extremophiles from environments with limited anthropogenic influences, including polar and high-altitude habitats, could bring important insights into both AMR evolution and antibiotic discovery (Hemala et al., 2014; Nunez-Montero and Barrientos, 2018; Willms et al., 2019; Kralova et al., 2021; Song et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022). Recent studies show that cold-environment microbes from Arctic and Antarctic regions (O’Brien et al., 2004; Mogrovejo et al., 2020; Kralova et al., 2021), polar marine ecosystems (Lo Giudice et al., 2007; Tam et al., 2015; Belov et al., 2020; Morozova et al., 2022), and non-Polar high-altitude sites (Ali et al., 2021) harbor unique resistance profiles and are able to produce biomolecules with unique structures and activities, including antimicrobial agents effective against pathogens and other microbes (Hemala et al., 2014; Mogrovejo et al., 2020). Isolated bacteria from Arctic and Antarctic soils and sediments (Nedialkova and Naidenova, 2005; Gesheva, 2010; Shekh et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2011; Mogrovejo et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2012a, 2012b), lakes and benthic mats (Biondi et al., 2008; Rojas et al., 2009; Wietz et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2014; Lo Giudice et al., 2007a) belong to diverse taxa such as Actinomycetota and Pseudomonadota, and have demonstrated activity against multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens (Lo Giudice et al., 2007; Ali et al., 2021). Recent studies indicated that the ice cave environments, with their distinct conditions of low temperature and oligotrophy, host bacterial strains producing antimicrobial and anticancer compounds (Ambrozic Avgustin et al., 2019; Jaroszewicz et al., 2021; Paun et al., 2021; Kosznik-Kwasnicka et al., 2022; Zada et al., 2022).

In the case of Scarisoara Ice Cave, harboring the largest and oldest underground ice block (Holmlund et al., 2005; Persoiu and Pazdur, 2010; Persoiu et al., 2017), recent data revealed preservation of viable bacterial communities in a chronosequence of perennial ice dating back up to 13,000 years (Paun et al., 2019). The cave ice microbiome harbored culturable strains showing a distinct antibiotic resistance profile and various enzymatic and antimicrobial activities (Paun et al., 2021). Such findings underscore the untapped potential of these extreme environments for discovering new bioactive compounds with medical applications.

The genus Psychrobacter (family Moraxellaceae, class Gammaproteobacteria) was described in 1986 with P. immobilis as the type species (Juni and Heym, 1986; Juni, 2005). Genomic studies suggest evolutionary adaptation to cold environments from mesophilic ancestors (Bakermans, 2018; Welter et al., 2021). Psychrobacter species have a widespread distribution, found primarily in cold and saline habitats (Rodrigues et al., 2009; Lasa and Romalde, 2017; Kampfer et al., 2020), with 44 of 52 identified species validated (Parte et al., 2020; Schoch et al., 2020). These Gram-variable, non-motile coccobacilli form cream to orange colonies and thrive at low temperatures, however tolerating up to 35–37 °C and varying salinities (Bowman et al., 1997; Juni, 2005; Bowman, 2006; Welter et al., 2021). They are strictly aerobic, catalase- and oxidase-positive, and utilize amino and organic acids as carbon sources while displaying limited biochemical versatility (Denner et al., 2001; Bowman, 2006; Gheorghita et al., 2021). Some species, such as P. sanguinis, P. arenosus, P. faecalis, P. pulmonis and P. phenylpyruvicus are opportunistic human pathogens (Deschaght et al., 2012; Wirth et al., 2012; Caspar et al., 2013; Yang, 2014; Bonwitt et al., 2018; Ioannou et al., 2025), while others, such as P. immobilis or P. glacincola, were found to affect fish species (Hisar et al., 2002; Deschaght et al., 2012; El-Sayed et al., 2023). Recent data show the pathogenic potential of Psychrobacter species, being rarely reported in human clinical samples (Ioannou et al., 2025). The genus holds biotechnological potential due to cold-active enzymes, carbonic anhydrases for bioremediation, and pathways for terpenoid biosynthesis and benzoate degradation, alongside genes for mercury detoxification and toxin resistance (Bull et al., 2000; Rothschild and Mancinelli, 2001; Bowman, 2006; Lee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Lasa and Romalde, 2017; Staloch et al., 2022). The antibiotic resistance profiles of Psychrobacter species remain largely underexplored (Romanenko et al., 2002; Bowman, 2006; Petrova et al., 2009; Bakermans, 2018).

In this context, the current study reports the isolation and functional characterization of a novel Psychrobacter strain from 5,000 year-old ice in Scarisoara Ice Cave (Romania) belonging to P. cryohalolentis species, with emphasis on its antibiotic resistance profile, antimicrobial potential, and enzymatic activities, integrated with putative determinants revealed by whole-genome sequence analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first genome sequence analysis of Psychrobacter species isolated from an ice cave, and first report on ancient microbial resistomes from this habitat.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strain isolation, identification and characterization

The Psychrobacter SC65A.3 bacterial strain was isolated from the 5,000 years old ice layer, part of the 25.33-meters ice core from Scarisoara Ice Cave, Romania, at 4 °C, on R2B medium (Paun et al., 2019, 2021).

The growth temperature range was assessed on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) medium by incubating the strain at various temperatures in the 4 °C-37 °C interval for 14 days, as described by Paun et al. (2021). The growth salinity range was evaluated in Luria Broth (LB) medium at 15 °C under agitation, using different concentrations of NaCl (0–4 M) and MgCl₂ (0–4 M).

The genomic DNA was isolated using a DNeasy Blood&Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA), and the strain identification was performed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, as previously described (Hillebrand-Voiculescu et al., 2013; Paun et al., 2021). The partial 16S rRNA gene sequence of this ice bacterial isolated strain was deposited in GenBank database under accession number MN577402.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was carried out by the Kirby-Bauer standard method (Bauer et al., 1966; Hudzicki, 2009; Matuschek et al., 2014) against 28 antibiotics belonging to 17 classes, on Muller-Hinton agar (MH). For the Psychrobacter SC65A.3 bacterial strain, the incubation has been performed at 15 °C for 48 h, while the Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (BioMérieux, France) and Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus Rosenbach ATCC 25923 (BioMérieux, France) used as control strains, at 37 °C for 24 h. The MH-agar medium contained 2 g/L meat extract (Scarlab, Spain), 1.5 g/L starch (Merck, Germany), 17.5 g/L casamino acids (VWR, USA), and 17 g/L bacteriological agar (300–2500 ppm calcium, 50–1000 ppm magnesium) (Scarlab, Spain). The interpretation was stratified as follows: (i) because no species-specific breakpoints are available for Psychrobacter, zone diameters (mm) for strain SC65A.3 were classified as susceptible or resistant using EUCAST 2020 (v10.0) (The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 2020) and CLSI 2021 (Humphries et al., 2021) breakpoints established for Acinetobacter spp., Moraxella catarrhalis and Pseudomonas spp., which represent the closest taxonomic relatives of the Scarisoara isolate; (ii) for antibiotics lacking breakpoints in these genera, we applied CLSI 2021 breakpoints defined for the reference Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus strains; (iii) for antibiotics without CLSI/EUCAST breakpoints, interpretation thresholds were taken from published studies, namely novobiocin (R < 16 mm) (Harrington and Gaydos, 1984), lincomycin (R < 6 mm) (Abdul-Jabbar et al., 2022), metronidazole (Hazim et al., 2020), and spectinomycin (R < 14 mm) (Martins et al., 2022).

The antimicrobial activity assays were conducted using a modified diffusion method (Paun et al., 2021), where SC65A.3 extracts (5 μL) were spotted on MH agar medium immediately after pathogen plating, and antimicrobial activity was determined after 18 h at 37 °C. The assay was performed against two reference strains (Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus Rosenbach) ATCC 25923 (BioMérieux, France) and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (BioMérieux, France), and 20 clinical isolated pathogens from the Microbial Collection of the Research Institute of The University of Bucharest. The presence of antimicrobial activity was assessed based on the presence or absence of an inhibition zone formed.

The biochemical characterization of the cave isolate SC65A.3 was done using API ZYM and API 20NE strips (BioMérieux, France), at 15 °C incubation temperature.

The enzymatic evaluation of API ZYM was done based on the number of nmol of hydrolyzed substrate as (0): no activity, (1 and 2): low activity (5 nmol and 10 nmol, respectively), (3): moderate activity (20 nmol), (4 and 5): high activity (30 nmol and ≥ 40 nmol, respectively) (Nowak and Piotrowska, 2012; Paun et al., 2021).

2.2 Whole genome sequencing (WGS)

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and analysis were carried out at Macrogen (South Korea). After 3 days of incubation at 15 °C with agitation (160 rpm), bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation (30 min, 7,500 rpm) and genomic DNA was extracted as described by Paun et al. (2021). A volume of 300 μL DNA (100 ng/μL) was used for WGS.

De novo genome sequencing of the complete genome involved PacBio RSII library construction (20 kb insert size), PacBio RSII SMRT cell sequencing (0.7 GB data per cell), Illumina DNA PCR-free library preparation (350 bp insert size), and Illumina NovaSeq 2 × 150 bp sequencing (6 GB data per sample).

PacBio long reads were assembled with HGAP3, and Illumina reads were subsequently used with Pilon (Walker et al., 2014) to improve sequence accuracy. Subreads were mapped to the assembled contigs to generate a consensus sequence with coverage depth. Following complete genome assembly, BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) was employed for taxonomic assignment, and the genome was analyzed to identify protein-coding sequences, tRNA genes, and rRNA genes. Functional annotation was performed using the EggNOG database (Huerta-Cepas et al., 2016).

Comparative genomic analysis was performed using CJ Bioscience’s online Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) calculator1 (Yoon et al., 2017) to compare the genome of Psychrobacter SC65.3 with those of 45 other Psychrobacter species. Genomic data for all comparisons were obtained from the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (Tatusova et al., 2016; Haft et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021).

Heatmap gene similarity matrices were obtained by importing spreadsheets from Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Excel, 2024) into Python 3.11 (Python Software Foundation, 2023) using the pandas 2.2.2 library. Non-numeric entries (e.g., “no similarity”) were converted to zero to allow numerical analysis. Hierarchical clustering and heatmap visualization were performed with seaborn 0.13.2 (clustermap function) and matplotlib 3.9.0. Clustering was computed using the SciPy 1.13.1 hierarchical clustering module with Euclidean distance and average linkage.

The circular representation of the genome was generated using the web-based platform Proksee (Grant et al., 2023). In our workflow, the complete genome sequence was provided in FASTA format, annotations were imported in GFF3 format, and circular rings were set up to display GC content, GC skew, CDS, rRNA, tRNA, CRISPR loci, antibiotic resistance genes (CARD), and other relevant genomic features. The resulting figure was exported in SVG format for graphical editing.

The complete genome sequence of the Scarisoara isolate Psychrobacter SC65A.3 was deposited in GenBank database under accession number CP106752.1, with NCBI RefSeq assembly number GCF_025642195.1.

2.3 Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses of 16S rRNA and gyrB sequences using maximum likelihood parsimony, curation, and rendering were performed using the www.phylogeny.fr platform (Dereeper et al., 2008). Sequence alignment was carried out using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). Taxonomic classification of microbial genomes was performed using GTDB-Tk (v2.3.2) within the KBase platform2 using the standard workflow (Arkin et al., 2018; Chaumeil et al., 2020). Input genomes were analyzed against the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB; release R214) (Parks et al., 2018). The output included comprehensive taxonomic assignments from domain to species level, estimates of genome completeness and contamination, and average nucleotide identity (ANI) values, leading to a phylogenetically consistent and reproducible classification according to the GTDB framework. A compact phylogenetic tree was generated using the Insert Set of Genomes Into SpeciesTree (v2.2.0) tool in KBase (Arkin et al., 2018). The online platform tool iTOL (Interactive Tree of Life) was employed for the visualization, annotation, and refinement of phylogenetic trees generated through maximum-likelihood (ML) analyses (Letunic and Bork, 2024).

3 Results

3.1 Isolation and identification of Psychrobacter SC65A.3

Cultivation on R2A medium at 4 °C of the 5,335 ± 54 years old ice sample collected from a 1,706–1,716 cm-deep ice core of Scarisoara Ice Cave led to growth of an orange/pink-pigmented colony that was selected and further purified (Supplementary Figure S1). This bacterial strain (SC65A.3) could grow on R2A, TSA, MH and LB media. On TSA, the cave isolate grew could grow at temperatures between 4 °C and 15 °C, consistent with its classification as a psychrophilic bacterium (Morita, 1975). When cultivated at 15 °C on LB over 7 days, it tolerated salinities ranging up to 1.9 M NaCl and 0.9 M MgCl2, consistent with the characteristics of a moderate halophilic extremophile (Ventosa et al., 1998).

BLAST analysis of the SC65A.3 16S rRNA amplicon showed 97% identity with that of Psychrobacter glaciei strain BIc20019 [NR_148850.1] isolated from an Arctic ice core (Zeng et al., 2016). The assignment of the ice cave strain SC65A.3 to the Psychrobacter genus was confirmed through phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences from 43 Psychrobacter species, showing that SC65A.3 clustered with 13 other psychrophilic and psychrotrophic members of the genus (Supplementary Figure S2).

3.2 Functional characterization of Psychrobacter SC65A.3

To evaluate the potential of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 new isolate for producing enhanced biotechnological and medical compounds, we determined various enzymatic functions, the antibiotic resistance profile and putative antimicrobial activities of this psychrophilic bacterium preserved for over 5,000 years in ice deposits of Scarisoara Ice Cave.

Screening of enzymatic activities of SC65A.3 using API ZYM system (Gruner et al., 1992) revealed notable production of lipase (C14), alkaline phosphatase, esterase (C 4), esterase lipase (C 8), and naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase (Table 1). A low enzymatic activity was recorded for valine arylamidase, cystine arylamidase, trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, α-glucosidase, and n-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, while no activity was observed for α-galactosidase, β-galactosidase, β-glucuronidase, β-glucosidase, α-mannosidase, and α-fucosidase in this cave-derived psychrophilic strain (Table 1).

Table 1

| Test API ZYM | Test API 20NE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Reaction/Enzyme | Results | ||

| Enzymatic activity | Results | NO3 | Reduction of nitrates to nitrites | + |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 3 | Reduction of nitrites to nitrogen | − | |

| Esterase (C 4) | 3 | TRP | Indole production | − |

| Esterase Lipase (C 8) | 3 | GLU | Fermentation D-glucose | − |

| Lipase (C 14) | 4 | ADH | Arginine dihydrolase | − |

| Leucine arylamidase | 3 | URE | Urease | + |

| Valine arylamidase | 2 | ESC | hydrolysis (β-glucosidase) (esculin) | + |

| Cystine arylamidase | 2 | GEL | hydrolysis (protease) | − |

| Trypsin | 1 | PNPG | β-Galactosidase | − |

| α-chymotrypsin | 1 | GLU | Assimilation D-glucose | − |

| Acid phosphatase | 0 | ARA | Assimilation L-arabinose | − |

| Naphthol-AS-BI-phosphohydrolase | 3 | MNE | Assimilation D-mannose | − |

| α-galactosidase | 0 | MAN | Assimilation D-mannitol | − |

| β-galactosidase | 0 | NAG | Assimilation N-acetyl-glucosamine | − |

| β-glucuronidase | 0 | MAL | Assimilation D-maltose | − |

| α-glucosidase | 1 | GNT | Assimilation potassium gluconate | − |

| β-glucosidase | 0 | CAP | Assimilation capric acid | − |

| N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | 1 | ADI | Assimilation adipic acid | − |

| α-mannosidase | 0 | MLT | Assimilation malic acid | − |

| α-fucosidase | 0 | CIT | Assimilation trisodium citrate | + |

| PAC | Assimilation phenylacetic acid | − | ||

Enzymatic profile of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 using API ZYM and API 20NE systems.

Color intensity corresponds to the activity (see Methods). No significance of the bold values.

Moreover, the substrate utilization profile of this ice cave isolate, as assessed by the API 20NE system, indicated the presence of nitrate reduction, urea hydrolysis, citrate assimilation and esculin hydrolysis (β-glucosidase) enzymatic activities (Table 1).

Investigation of the antibiotic resistance of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 to 28 antibiotics of broad spectrum, narrow spectrum and anaerobe-specific covering 17 classes (Supplementary Figure S3) revealed resistance of this strain to narrow spectrum antibiotics (i.e., clindamycin, lincomycin, vancomycin), to metronidazole, and to 6 out of the 21 broad-spectrum antibiotics (Table 2).

Table 2

| Antimicrobial spectrum | Antimicrobial class | Antibiotics (code/μg) | SC65A.3 | S. aureus | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST profile (diameter—mm) | |||||

| Broad spectrum | Penicillin | Ampicillin (AMP/ 25 μg) | S (43) | S (34) | R (13) |

| Carbenicillin (CAR/100 μg) | S (47) | S (40) | R (14) | ||

| Cephalosporins | Ceftazidime (CAZ/30 μg) | R (18) | R (12) | R (19) | |

| Cefixime (CFM/5 μg) | S (25) | R (10) | S (17) | ||

| Cefotaxime (CTX/30 μg) | S (30) | S (26) | S (26) | ||

| Cefpirome (CPO/30 μg) | S (25) | R (16) | S (23) | ||

| Cephalothin (KF/30 μg) | R (6) | S (35) | R (6) | ||

| Cefpodoxime (CPD/10 μg) | S (33) | S (27) | S (22) | ||

| Carbapenems | Imipenem (IPM/10 μg) | S (65) | S (40) | S (35) | |

| Fluoroquinolones | Ciprofloxacin (CIP/10 μg) | R (30) | R (21) | S (36) | |

| Nalidixic acid (NA/30 μg) | S (56) | R (8) | S (30) | ||

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin (CN/30 μg) | S (29) | S (19) | S (21) | |

| Spectinomycin (SH/25 μg) | R (13) | R (8) | R (14) | ||

| Streptomycin (S/25 μg) | S (24) | R (14) | S (21) | ||

| Coumarin glycosides | Novobiocin (NV/6 μg) | S (26) | R (19) | R (6) | |

| Chloramphenicol | Chloramphenicol (C/30 μg) | S (45) | R (20) | S (26) | |

| Nitrofurantoin | Nitrofurantoin (F/100 μg) | S (17) | S (14) | S (25) | |

| Rifampin | Rifampicin (RD/5 μg) | R (37) | S (26) | R (20) | |

| Sulfonamide compounds S3 | Sulfonamide compounds (S3/300 μg) | S (47) | R (6) | S (26) | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline (TE/30 μg) | S (39) | S (25) | S (24) | |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfonamides | Trimethoprim (W/5 μg) | R (6) | S (17) | S (23) | |

| Narrow spectrum (G+) | Macrolides | Clarithromycin (CLR/15 μg) | S (26) | R (20) | R (18) |

| Erythromycin (E/15 μg) | S (21) | S (21) | R (12) | ||

| Lincosamide | Clindamycin (DA/2 μg) | R (6) | S (22) | R (6) | |

| Lincomycin (MY/15 μg) | R (6) | S (22) | R (6) | ||

| Fatty Acyls | Mupirocin (MUP/5 μg) | S (35) | R (23) | R (6) | |

| Glycopeptides | Vancomycin (VA/30 μg) | R (14) | R (13) | R (6) | |

| Anaerobes | Metronidazole | Metronidazole (MTZ/5 μg) | R (6) | R (6) | R (6) |

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 and the reference strains Staphylococcus aureus subsp. Rosenbach ATCC 25923 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922.

Resistance (R) and susceptibility (S) categories were assigned from inhibition zone diameters (mm) according to EUCAST breakpoint Table v10.0 (2020), CLSI 2021, and published literature (see Methods). Resistance (bold).

Considering the observed resistance to 10 out of 28 tested antibiotics belonging to 8 classes, this ice cave strain exhibited a multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype (Table 2), consistent with the ECDC/CDC consensus definitions considering the MDR phenotypes as non-susceptible to at least one agent from three or more antimicrobial categories (Magiorakos et al., 2012). However, these data must be interpreted with caution. First, no species-specific clinical breakpoints are available for Psychrobacter, so the R/S categories were inferred using breakpoints established for related species or from literature-derived cut-offs, rather than from dedicated guidelines for this taxon. Second, given the particular origin of this strain (an ice cave), standard MH agar and conventional incubation conditions may not be optimal for accurately revealing its susceptibility profile (Gattinger et al., 2023). It is also known that elevated cation concentrations can modulate apparent antibiotic resistance by stabilizing biofilm structure, influencing efflux pump activity, or acting as an essential cofactor that alters the activity of certain antibiotics such as daptomycin (Lee et al., 2019; Nechifor et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025). Therefore, the corresponding calcium (5.1–42.5 μg/mL) and magnesium (0.85–17 μg/mL) concentrations in the MH medium used for the SC65A.3 assays may have an impact on the resistance phenotype of the cave strain. In addition, antibiotic susceptibility in cold-adapted bacteria is temperature-dependent, which could bias the quantitative measurements for psychrophilic or psychrotolerant isolates (Gattinger et al., 2023).

The antimicrobial activity of SC65A.3 tested against 20 clinical bacterial strains and 2 ATCC reference strains (Supplementary Figure S4) indicated that this cave isolate inhibited both S. aureus and E. coli ATCC strains, as well as 12 of the 20 clinical pathogens tested (Table 3). Notably, SC65A.3 showed an antimicrobial activity against several Gram-negative pathogens, including Enterobacter spp. (2 strains), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 strains), Klebsiella pneumoniae (3 strains), and E. coli ATCC 25922 (Table 3). Meanwhile, no inhibitory effect against Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates, Enterobacter asburiae 19,069 ONE1, Klebsiella pneumoniae 19,047 ENE4, and two methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains was observed (Table 3).

Table 3

| Test pathogen | Antimicrobial activity of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 (+/−) |

|---|---|

| Gram positive pathogenic strains | |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 | + |

| MRSA 19081 F1 | + |

| MRSA 19081 S1 | − |

| MRSA 388 | − |

| Enterococcus faecium 19,040 E1 | + |

| Enterococcus faecium 19,040 E2 | + |

| Enterococcus faecium 19,040 E3 | + |

| Gram negative pathogenic strains | |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | + |

| Enterobacter asburiae 19,069 ONE1 | − |

| Enterobacter cloacae 19,069 ONE2 | + |

| Enterobacter cloacae 19,069 ONE3 | + |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa CN11 | + |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 19,053 CNE5 | + |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 19,053 CNE6 | + |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 8 | − |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 19,094 CK1 | + |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 19,094 CK2 | + |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 19,094 CK3 | + |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 19,047 ENE4 | − |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 19,047 CNE5 | − |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 19,047 CNE3 | − |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 18,032 C3 | − |

| Total | 14 |

Antimicrobial activity of Psychrobacter SC65A.3.

Presence (+) and absence (−) of inhibitory growth effect on Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogenic strains of S. aureus and E. coli ATCC collection strains, and clinical strains of genera MRSA, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and Acinetobacter.

3.2.1 Whole genome sequencing and analyses

Based on the functional properties of Scarisoara strain SC65A.3, the whole genome was sequenced for identifying structural elements associated with the natural antibiotic resistance of this cave strain entrapped in ice for the last 5 millennia and for future studies investigating novel cold-active enzymes and bioactive molecules, also highlighting the putative thermal-adaptation gene pool of this psychrophilic ice cave bacterium.

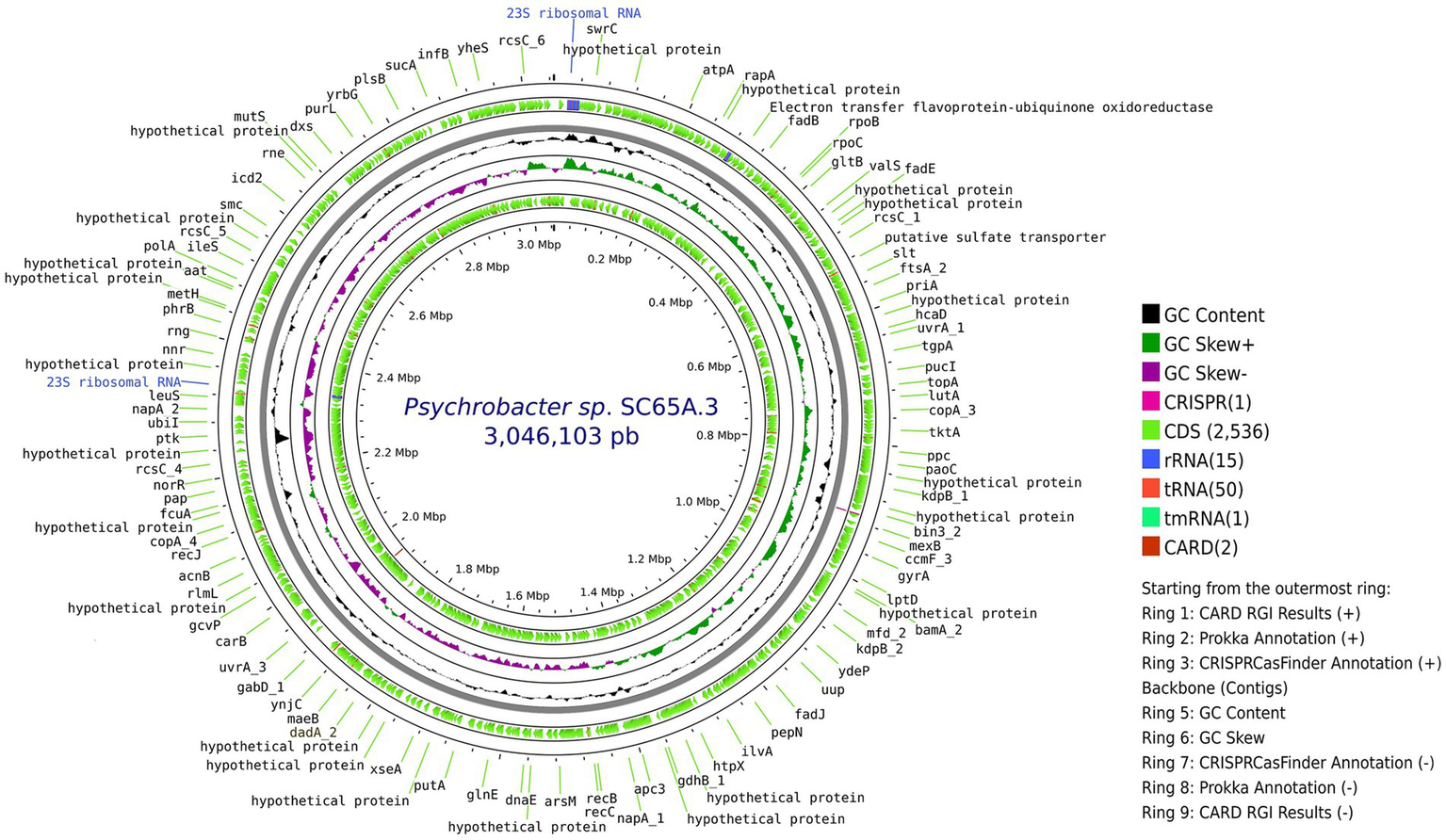

PacBio sequencing and subreads filtering of Scarisoara strain SC65A.3 genome produced 1,351,448,809 subread bases, with a mean 10,421 subread length and 129,674 subreads with an N50 value of 14,351 base pairs. De novo genome assembly generated a unique circular contig of 3,046,103 bases length (Figure 1), with a GC content of 42.52%. The genome comprised 2,602 CDS, 15 rRNA genes, 50 tRNA genes, and 15 rRNA, with a single CRISPR locus and two predicted antibiotic resistance genes (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Circular representation of the complete genome of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3. From the outermost to the innermost rings: (1) CARD RGI resistance gene hits (positive strand), (2) annotated coding sequences (CDS) identified by Prokka, (3) CRISPR loci detected by CRISPRCasFinder, (4) genome backbone (contigs), (5) GC content, (6) GC skew (green = positive, purple = negative), (7) CRISPRCasFinder annotations (negative strand), (8) Prokka CDS annotations (negative strand), and (9) CARD RGI results (negative strand). Gene names indicate key metabolic, regulatory, or structural functions identified along the chromosome.

BLAST analysis of the complete genome revealed 97% identity with the Psychrobacter cryohalolentis strains FDAARGOS_308 [CP022043.2] and K5 [CP000323.1], and with Psychrobacter sp. strain G [CP006265.1] (Supplementary Table S1).

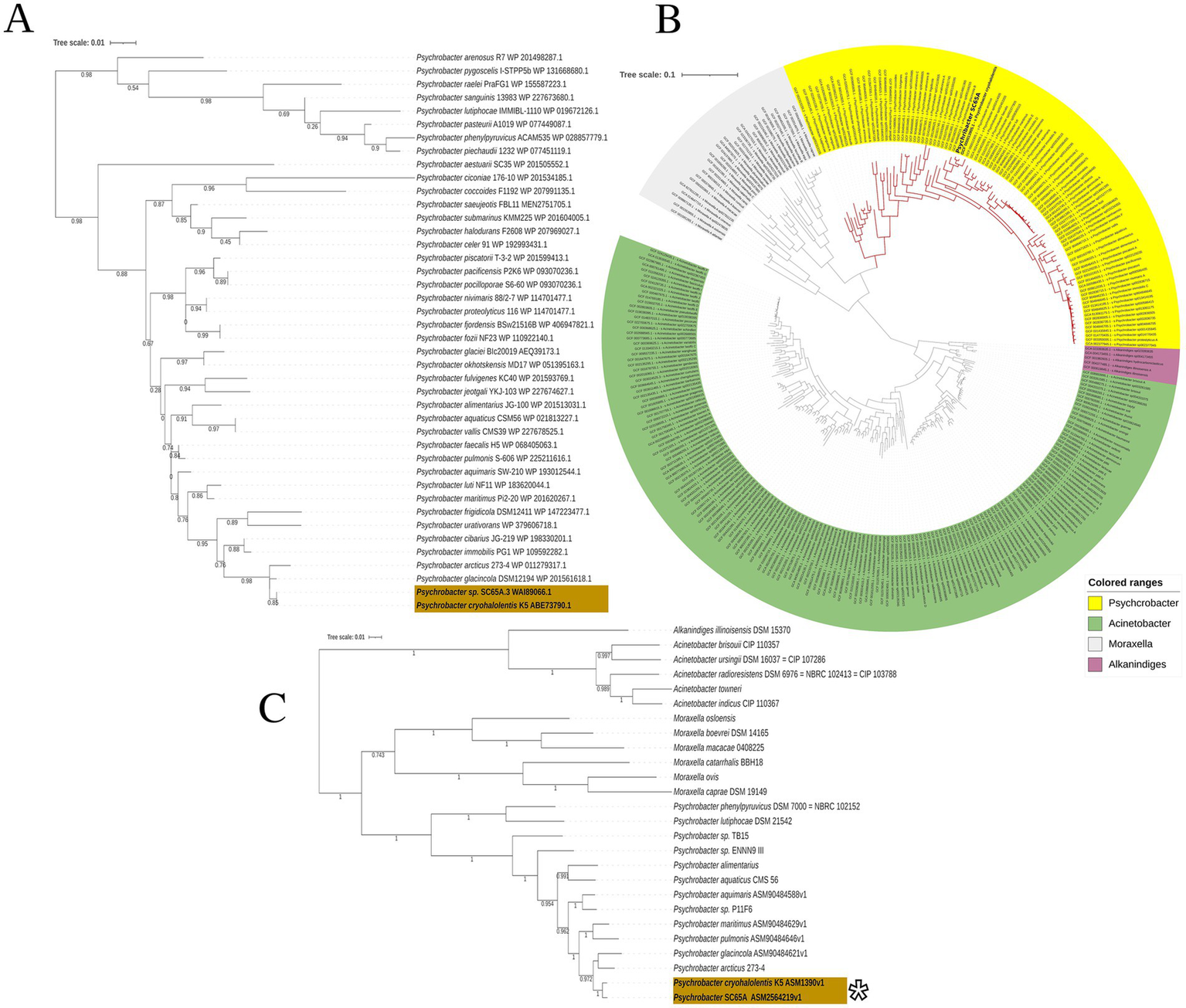

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis based on 41 gyrB gene sequences (Bakermans et al., 2006) sustained the taxonomic affiliation of SC65A.3 by positioning this ice cave strain within a well-supported clade alongside Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5 [CP000323.1], suggesting a close evolutionary relationship within the genus (Figure 2A). This lineage was also grouped with P. glacinicola DSM12194 [WP_201561618] and P. arcticus 273–4 [WP_011279317] with high bootstrap support (~0.95), while showing more distant evolutionary relationships to other Psychrobacter clustered lineages of P. phenylpyruvicus, P. pacificensis, and P. piechaudii (Figure 2A). These findings indicate that SC65A.3 belongs to a cold-adapted Psychrobacter lineage, in agreement with the phylogenetic pattern observed in the 16S rRNA gene-based analysis (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 2

Phylogenetic position of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 based on gyrB gene and whole-genome sequences. (A) Maximum-likelihood tree based on gyrB gene sequences showing the phylogenetic position of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 among 44 Psychrobacter strains retrieved from the NCBI database. (B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenomic tree constructed from 332 genomes, including 100 Psychrobacter genomes, illustrating the taxonomic relationships within the Moraxellaceae family. Colored ranges indicate different genera: Psychrobacter (green), Acinetobacter (yellow), Moraxella (purple), Alkanindiges (gray). (C) Maximum-likelihood tree based exclusively on Psychrobacter genomes, highlighting the clustering of Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 with its closest relatives, P. cryohalolentis K5 and P. glacincola DSM 15331. Bootstrap values are indicated at the nodes. (*) ANI value = 96.63%.

A phylogenomic analysis of whole genomes based on 322 genomes, among which 100 from Psychrobacter genus (Figure 2B), revealed that Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 clustered firmly within the monophyletic clade corresponding to genus Psychrobacter, that is clearly separated from the related genera Acinetobacter, Moraxella, and Alkanindiges (Figure 2C). Within this group, SC65A.3 was positioned in a well-supported subclade together with Psychrobacter cryohalolentis, as also observed by the gyrB phylogenetic analysis (Figure 2A), a species known for its adaptations to permafrost environments and cryogenic conditions (Bakermans et al., 2006). The close phylogenetic relationship between SC65A.3 and P. cryohalolentis (Figure 2C) suggests a high degree of genomic similarity and a possible common origin in cold or marine ecosystems, in line with the general characteristics of the genus Psychrobacter adapted to Polar and cold marine environments. In addition to the phylogenomic profile, the 96.63% average nucleotide identity (ANI) across all shared orthologous genes between Psychrobacter sp. SC65A.3 and the three Psychrobacter cryohalolentis genomes (Figure 2C) supports the assignment of the cave strain to this species.

3.2.2 Psychrobacter SC65A.3 genome annotation

Sequence homology analysis of the assembled Psychrobacter SC65A.3 genome indicated a total of 2,602 genes of which 2,536 protein-coding sequences (CDSs) and tRNA and rRNA genes (Supplementary Table S1, Figure 2A). Functional annotation disclosed 2,428 genes assigned to a single EggNOG orthologous group and 56 mapped to multiple groups (Supplementary Table S1).

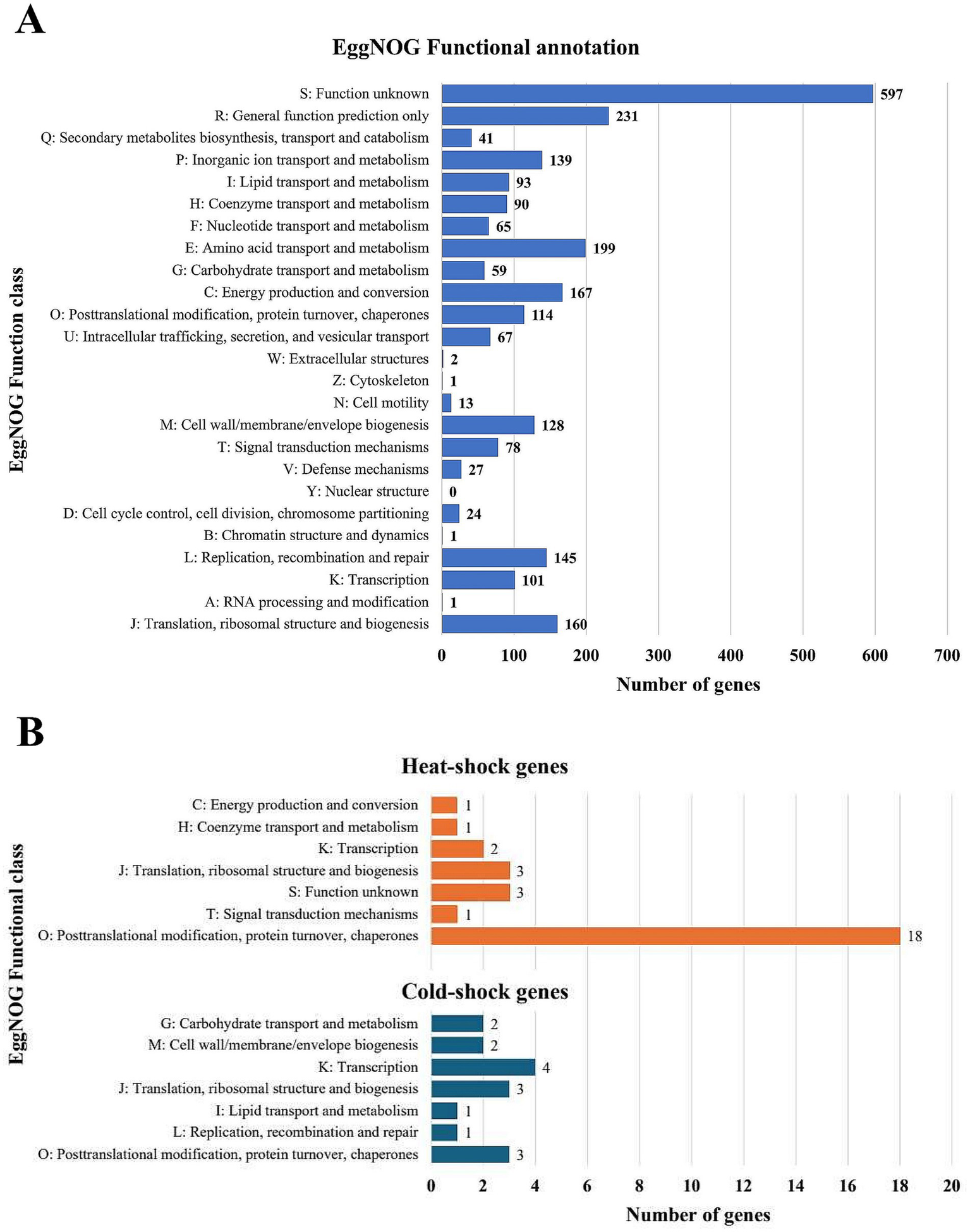

Among the assigned genes, the largest group was associated with general function prediction (231), amino acid transport and metabolism (199), and energy production and conversion (167) (Figure 3A). A considerable number of genes were linked to translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis (160), replication, recombination, and repair (145), inorganic ion transport and metabolism (139), and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (128). Also, more than 100 genes related to posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperone activity and transcription were annotated, while single genes were identified for RNA processing and modification, chromatin structure and dynamics, and cytoskeleton organization, while no genes associated with nuclear structure were detected (Figure 3A). Notably, a substantial number of genes (597) were classified with unknown functions, suggesting untapped potential for discovering novel biological mechanisms in the psychrophilic Psychrobacter strain from this underexplored icy habitat (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

Gene annotation and temperature adaptability gene profile of Psychrobactcer SC65A.3. (A) EggNOG functional gene annotation and classification; (B) Heat-shock (orange) and cold-shock (blue) gene distribution based on EggNOG analysis.

3.2.3 Low temperature adaptation genes

Given the psychrophilic nature of this ice-isolated bacterial strain, analysis of the SC65A.3 genome highlighted 45 genes associated with thermal adaptation, among which a large majority (29) involved in heat-shock processes and only 16 in cold-shock responses (Supplementary Table S2; Figure 3B). As expected, most of these genes (21) are chaperones involved in posttranslational modifications and protein turnover, primarily representing heat-shock adaptations (18 genes) (Figure 3B). A restrained number of genes (2–4) associated with transcription and translation processes and ribosomal structure and biogenesis appeared to be involved in both heat-shock and cold-shock processes, while distinct pathways appeared to participate to either cold-shock (6 genes from carbohydrate and lipid transport and metabolism, cell wall biogenesis, and replication, recombination, and repair), or heat-shock (3 genes involved in energy production and conversion, coenzyme transport and metabolism and signal transduction) processes (Figure 3B). Interestingly, three genes classified under EggNOG unknown functions were assigned to heat-shock response, indicating potential unique thermal adaptation mechanisms in this cave ice-retrieved bacterial strain (Figure 3B).

3.2.4 Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in correlation with the phenotypic profile of the Psychrobacter SC65A.3 strain

In line with the phenotypic profile of antibiotic resistance of SC65A.3, the genomic DNA coding sequence was analyzed with a focus on genes associated with intrinsic or acquired antibiotic resistance, and with biosynthesis of compounds with antimicrobial activity (Table 4).

Table 4

| EggNOG genes | ARGs (no) | Antimicrobials biosynthesis genes (no) |

|---|---|---|

| J: Translation, ribosomal structure, biogenesis (160) | aviRb, fusA, ileS, rng, rplD, rplF, rplV, rpmG, rpsD, rpsE, rpsL, rpsQ, rsmA_1, thrS (14) | - |

| K: Transcription (101) | rpoB, rpoC, merR1_1, rpoD, tetC, acrR, rpoA, merR1_2, coaX (9) | - |

| L: Replication, recombination & repair (145) | parE, parC, gyrA, mfd, nudC_2, polC, gyrB (7) | - |

| D: Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning (24) | crcB, relE (2) | - |

| V: Defense mechanisms (24) | ampC, emrK, macB, mdtA, mdtK, mepA, mexA, msbA, uppP, yojI (10) | - |

| T: Signal transduction mechanisms (78) | cpxA, cpxR, phoP, walR | - |

| zraR, zraS_1, zraS_2 (7) | ||

| M: Cell wall/membrane/ envelope biogenesis (128) | ampD, ftsI, galU, lpxA, lpxC, lpxD, macA, mipA, murA, murG, murU, oprM, porB, rsmG, ywnH (15) | sunS (1) |

| U: Intracellular trafficking, secretion, vesicular transport (67) | pilQ (1) | - |

| O: Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones (114) | anmK (1) | - |

| C: Energy production/ conversion (167) | merA (1) | pikAII (1) |

| G: Carbohydrate transport/ metabolism (59) | ampG, nagZ (2) | - |

| E: Amino acid transport/ metabolism (199) | aroK, mhqA (2) | btrK, rebO_1, rebO_2 (3) |

| F: Nucleotide transport/ metabolism (65) | thyA, nudC_1, dut (3) | - |

| H: Coenzyme transport/ metabolism (90) | dfrA, folP, ubiA, rsmA_2 (4) | - |

| I: Lipid transport/ metabolism (93) | clsA_1, clsA_2, cdsA, fabI, clsC, pgsA (6) | dpgD (1) |

| P: Inorganic ion transport/ metabolism (139) | arsA, arsB, arsC, bcr, cirA, emrE, merP, mexB, swrC, yejB, yejE (11) | - |

| Q: Secondary metabolites biosynthesis/ transport/ catabolism (41) | sttH (1) | - |

| R: General function prediction (231) | tetA (1) | - |

| S: Function unknown (597) | amgK, arsH, mcr1, mshB, mupP, pvdQ, rarD_1, rarD_2, rarD_3, yejF (10) | bacC, bpoA2, cetB, rdmC, sdhE (5) |

| Total count genes: 2543 | 107 | 11 |

EggNOG Psychrobacter SC65A.3 functional annotation for antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and biosynthesis of antimicrobial compounds.

Genes relevant to clinical resistance (bold).

From the total of 2,543 genes, 107 were identified as genes associated with AMR (Table 4). Some of them were distributed across a broad range of functional categories within the EggNOG database, including transcription, replication, recombination and repair, as well as signal transduction mechanisms. Other genes were associated with lipid transport and metabolism, coenzyme transport and metabolism, and nucleotide transport and metabolism. A smaller subset of resistance-associated genes was related to cell cycle control, amino acid metabolism, and carbohydrate metabolism. Single genes were also identified within categories related to energy production, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, intracellular trafficking, general function prediction, and posttranslational modification (Table 4).

The genes relevant to clinical resistance (Table 4) are associated with resistance to β-lactams (ampC, ftsI, ampD, ampG), tetracyclines (tetA, tetC), fluoroquinolones (gyrA, gyrB, parC, parE), aminoglycosides / multidrug efflux (mexA, mexB, oprM, emrK, mdtA, mdtK, macB, mepA, msbA, macA, bcr, emrE), rifampin (rpoB), trimethoprim / sulfonamides (dfrA, folP), colistin (mcr1), resistance to heavy metals (arsA, arsB, arsC, merA, merP, merR1_1, merR1_2).

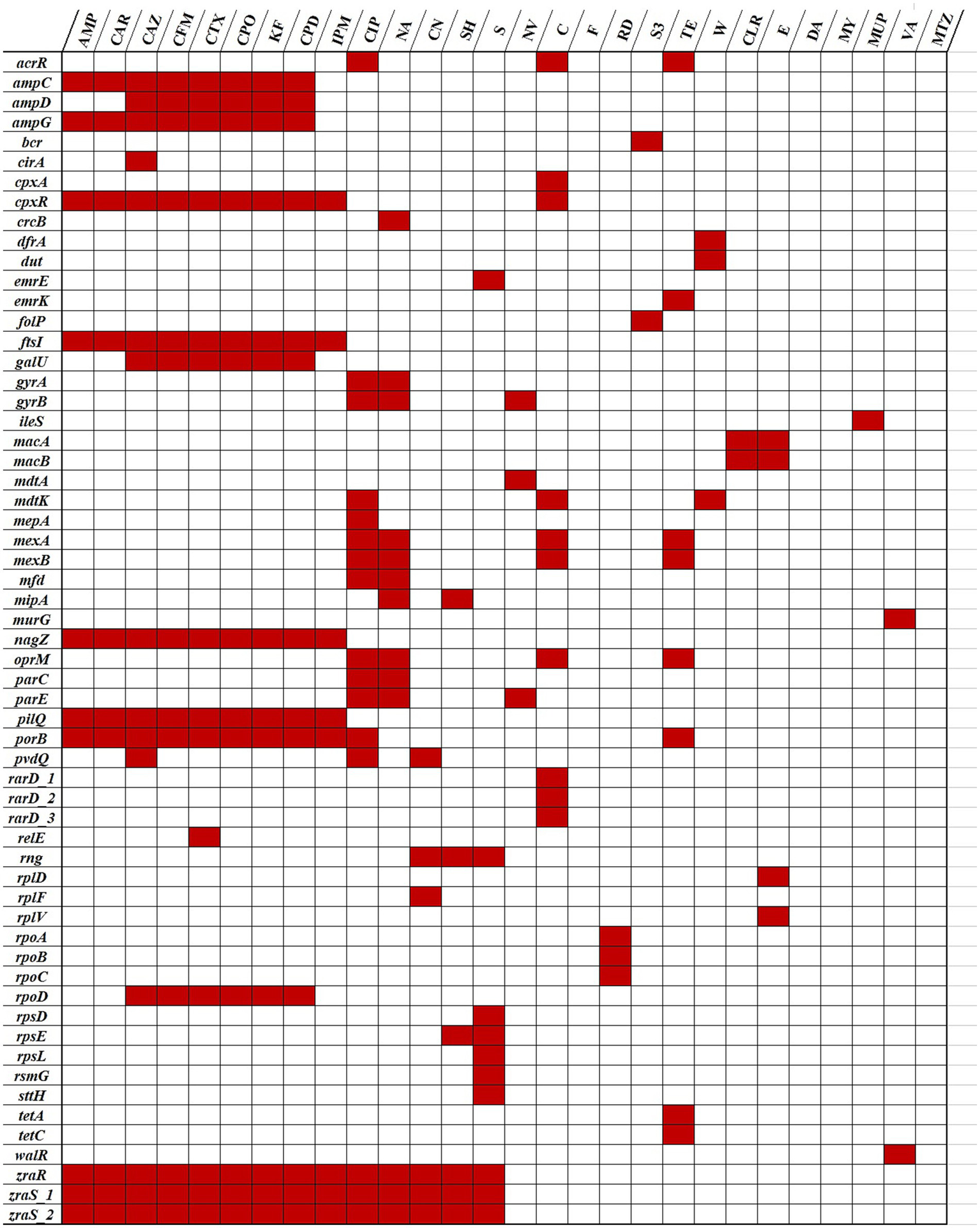

From the 107 ARGs, 44 could be linked to intrinsic or acquired resistance against the antibiotics tested in this study (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Correlation of the Psychrobacter SC65A.3 antibiotic resistance phenotypic and genotypic profiles. (Red blocks): Resistance genes (y-axis) matching the phenotypic antibiotic resistance (x-axis); (white blocks): no resistance genes detected or antibiotic susceptibility not tested. Data available in Tables 2, 4.

The correlation analysis between the phenotypic resistance profile (Table 2) of the SC65A.3 strain and its gene pool related to antibiotic resistance (Table 4) shown that resistance to certain antibiotics was not linked to any specific ARG detected in the genome (Figure 4). However, the functional resistance to these antibiotics could be due to the presence of multidrug efflux genes harbored by this strain (Jian et al., 2021; Gaurav et al., 2023; Elshobary et al., 2025).

3.2.5 Antimicrobial activity-related genes in Psychrobacter SC65A.3

Analysis of the SC65A.3 genome for genes potentially involved in antimicrobial activity identified a total of 11 candidates (Table 4). The identified genes are involved in the biosynthesis of sublancin, an S-linked glycopeptide (sunS) (Oman et al., 2011), pikromicin (pikAII) (Xue et al., 1998) (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9ZGI4/entry), butirosin (btrK) (Popovic et al., 2006), rebeccamycin (rebO) (Nishizawa et al., 2005), glycopeptide (dpgD) (Chen et al., 2001), bacitracin (bacC) (Konz et al., 1997), haloperoxidase (bpoA2) (Hecht et al., 1994), cetoniacytone A (cetB) (Wu et al., 2009), anthracycline tailoring (rdmC) (Jansson et al., 2003), and a succinate dehydrogenase assembly factor (sdhE) (McNeil et al., 2012) (Table 4).

4 Discussion

4.1 Taxonomic position and physiological characteristics of the ice cave Psychrobacter SC65A.3 strain

Despite the remarkable ecological and biotechnological potential of psychrophilic and psychrotrophic bacteria, the recovery and characterization of cold-adapted antibiotic producers remain limited as compared to mesophiles (O’Brien et al., 2004; Sanchez et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2018). To advance a comprehensive understanding of microbial life in cold environments, integrated research should focus on mapping their taxonomic and functional diversity, uncovering the mechanisms of cold adaptation, evaluating their roles in biogeochemical cycles and climate feedback processes, and exploring novel microbial taxa and functions with potential applications in biotechnology and medicine.

The novel bacterial strain SC65A.3 isolated from 5,000-year-old ice deposits of Scarisoara Ice Cave represents a polyextremophile classified as psychrophilic, with a growth range of 4–15 °C, and as a moderate halophile, tolerating up to 1.8 M NaCl and 0.9 M MgCl₂. Molecular identification based on 16S rRNA gene homology indicated the closest match (97% identity) with Psychrobacter glaciei BIc20019 [NR_148850.1] originating from an Arctic ice core in Svalbard (Zeng et al., 2016).

The genus Psychrobacter displays a wide ecological distribution, with species recovered from various habitats, primarily cold and saline environments (Rodrigues et al., 2009; Lasa and Romalde, 2017). According to the NCBI Taxonomy Database (Schoch et al., 2020) and the List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (Parte et al., 2020), 52 Psychrobacter species have been described to date, of which 44 are taxonomically validated and 43 have documented morphological or functional characterization.

Psychrobacter species are able to thrive at low temperatures, being predominantly psychrotrophic or psychrophilic, while some strains can grow at 35–37 °C, with a minimum temperature limit of 10 °C (Vela et al., 2003; Romanenko et al., 2004; Baik et al., 2010; Kampfer et al., 2015, 2020). Additionally, certain species tolerate a broad salinity range, being categorized as polyextremophiles (Juni, 2005; Bowman, 2006; Welter et al., 2021) (Supplementary Table S3). In this respect, SC65A.3 represents a novel psychrophilic and halotolerant Psychrobacter strain, consistent with the characteristics of many species inhabiting cold environments.

Most Psychrobacter isolates, including the cave strain SC65A.3, can grow in the absence of added salts, whereas some require elevated salinity for optimal growth. For example, P. cibarius, isolated from fermented food, grows only within a 2–10 M NaCl range (Jung et al., 2005), and P. pulmonis, from lamb lungs, requires 1.1 M NaCl (Vela et al., 2003) (Supplementary Table S3). Most Psychrobacter species tolerate NaCl concentrations up to approximately 2 M, comparable to SC65A.3 which grows in media containing up to 1.9 M NaCl (Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, marine species demand higher salinity, such as P. nivimaris from the South Atlantic (2.23 M) (Heuchert et al., 2004), P. submarinus from Pacific waters (Romanenko et al., 2002; Shivaji et al., 2004; Kaur et al., 2023) and P. celer from the South Sea, both tolerating up to 2.7 M NaCl (Yoon et al., 2005c), and P. saeujeotis from salted shrimp jeotgal, which grows in up to 3.5 M NaCl (Kim et al., 2025).

Given the cold-loving characteristics of most Psychrobacter species, the industrial and biotechnological interest in these bacteria is focused on the discovery of novel cold-active proteins and enzymes with broad applicability (Bull et al., 2000; Rothschild and Mancinelli, 2001; Bowman, 2006). In this respect, the highly active carbonic anhydrase of Psychrobacter sp. SHUES1 (Li et al., 2016) is a potential biocatalyst for bioremediation, while other strains harboring two metabolic pathways involved in terpenoids biosynthesis and benzoate degradation (Lee et al., 2016) could be exploited for food and pharmaceutical industries.

Based on ANI values (Supplementary Table S4) and on literature data, 12 different Psychrobacter species among which 7 psychrophilic and 5 psychrotrophic were phenotypically compared to the Scarisoara strain, showing a different functional profile with respect to substrate assimilation and enzymatic activities (Supplementary Table S3).

Among the metabolic activities revealed by the API 2ONE and API ZYM biochemical tests, SC65A.3 evidenced a distinct functional profile regarding esculin hydrolysis (absent in all other species), urease activity (present only in P. muriicola 2pS), cysteine arylamidases (present only in P. pulmonis S-606), and scarcely encountered valine arylamidase activity and trisodium citrate catabolism (Supplementary Table S3). Most reported Psychrobacter species are unable to hydrolyze complex substrates, while some are capable of protein hydrolysis, preferentially utilize organic and amino acids as carbon sources, and frequently exhibit lipolytic activity (Denner et al., 2001; Bowman, 2006). The lipase (C14) activity of SC65A.3, also observed in certain psychrophilic Psychrobacter species (Supplementary Table S3), was evaluated for potential biotechnological applications (Gheorghita et al., 2021; Paun et al., 2024), given the high hydrolytic capacity of this ice-cave isolate toward long-chain fatty acids.

Overall, the enzymatic profile of this novel ice cave strain indicates a wide-ranging potential for applications in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and environmental processes.

4.2 Genetic comparison of cold-adapted Psychrobacter strains

The current study providing the first whole-genome sequence of a Psychrobacter strain isolated from cave ice belonging to P. cryohalolentis species revealed a range of distinctive genomic features as compared to other Psychrobacter species from cold environments. These unique traits may reflect specific adaptations to the extreme conditions of this subterranean ice habitat.

At the genome assembly level, only 12 Psychrobacter species were found to have complete genomes, of which six are psychrophilic strains, similar to SC65A.3 (Supplementary Table S4). Based on Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) values, the closest genomic identity to SC65A3 was observed with the psychrophilic strains Psychrobacter sp. G (96.84%) and P. cryohalolentis K5 (96.63%) isolated from Antarctic seawater (Che et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017) and a Siberian cryopeg (Bakermans et al., 2003, 2006), respectively. Lower ANI values were recorded for the psychrophilic P. arcticus 273–4 (88.13%) isolated from Siberian permafrost (Bakermans et al., 2006), and P. glacincola DSM12194 (88.06%) originating from Antarctic Sea ice (Bowman et al., 1997). The lowest score (72.3%) was found with the mesophilic P. phenylpyruvicus ACAM535 strain (Bovre and Henriksen, 1967; Bowman et al., 1996) (Supplementary Table S4), suggesting that temperature adaptation in Psychrobacter is linked to distinct genetic mechanisms.

The genome sizes of analyzed Psychrobacter species range from 3,696,886 bp in P. arenosus (isolated from marine sediment in the Sea of Japan) (Romanenko et al., 2004) to 2,484,493 bp in P. ciconiae (isolated from white storks) (Kampfer et al., 2015), with that of SC65A.3 falling within this range at 3,046,103 bp (Supplementary Table S4). Comparison of the GC content of Psychrobacter strain SC65A.3 (42.5%) with 45 other Psychrobacter species revealed identical values with 11 strains, including the psychrophilic Psychrobacter sp. G (Che et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017), P. cryohalolentis K5 (Bakermans et al., 2003, 2006), P. glacincola DSM12194 (Bowman et al., 1997), and P. nivimaris 88/2–7, isolated from southern Atlantic seawater (Heuchert et al., 2004), and seven psychrotolerant or mesophilic strains counting the Antarctic P. luti NF11 and P. fozii NF23 strains (Bozal et al., 2003), P. fjordensis BSw21516B retrieved from Arctic seawater (Zeng et al., 2015), P. saeujeotis FBL11 (Kim et al., 2025) and P. jeotgali YKJ-103 (Yoon et al., 2003) isolated from fermented seafood, alongside P. pasteurii A1019 and P. piechaudii 1,232 (Hurtado-Ortiz et al., 2017). A relatively higher GC content (49.5%) was observed in the case of the mesophilic strain P. aestuarii SC35 originating from tidal flat sediment (Baik et al., 2010) (Supplementary Table S4).

Comparative analysis of Psychrobacter genomes showed that the predicted gene count of the Scarisoara SC65A.3 strain is similar to both psychrophilic and psychrotolerant species, despite differing isolation habitats. Its total gene number closely matches psychrophiles like P. cryohalolentis K5 (2,615) from Siberian cryopeg (Bakermans et al., 2003, 2006) and P. submarinus KMM225 (2,624) from Pacific sea water (Romanenko et al., 2002; Shivaji et al., 2004; Kaur et al., 2023), as well as the mesophilic P. celer 91 (2,583) from the Korean South Sea (Yoon et al., 2005c), in contrast with the psychrotolerant P. piscatorii T-3-2 (Yumoto et al., 2010) that has a notably higher gene count of 3,049 (Supplementary Table S4).

Genome annotation indicated a relatively high number of rRNA genes (15) in the case of SC65A.3, similar to other seven Psychrobacter species including the psychrophilic P. pacificensis WSYP01 isolated from 6,000 m depth in the Japan Trench (Maruyama et al., 2000) (Supplementary Table S4), while only two other species showed a higher number (18) of rRNA genes, counting the psychrophilic P. muriicola 2pS originating from permafrost (Shcherbakova et al., 2009) and the psychcrotolerant P. fjordensis BSw21516B isolated from Arctic seawater (Zeng et al., 2015) (Supplementary Table S4). Psychrobacter SC65A.3 genome also contains 50 tRNA genes, matching two other species—the psychrophile P. pacificensis WSYP01 (Maruyama et al., 2000) and the mesophile P. alimentarius PAMC27889 (Yoon et al., 2005a), as compared to the mesophilic P. raelei PraFG1 (57) (Manzulli et al., 2024) (Supplementary Table S4).

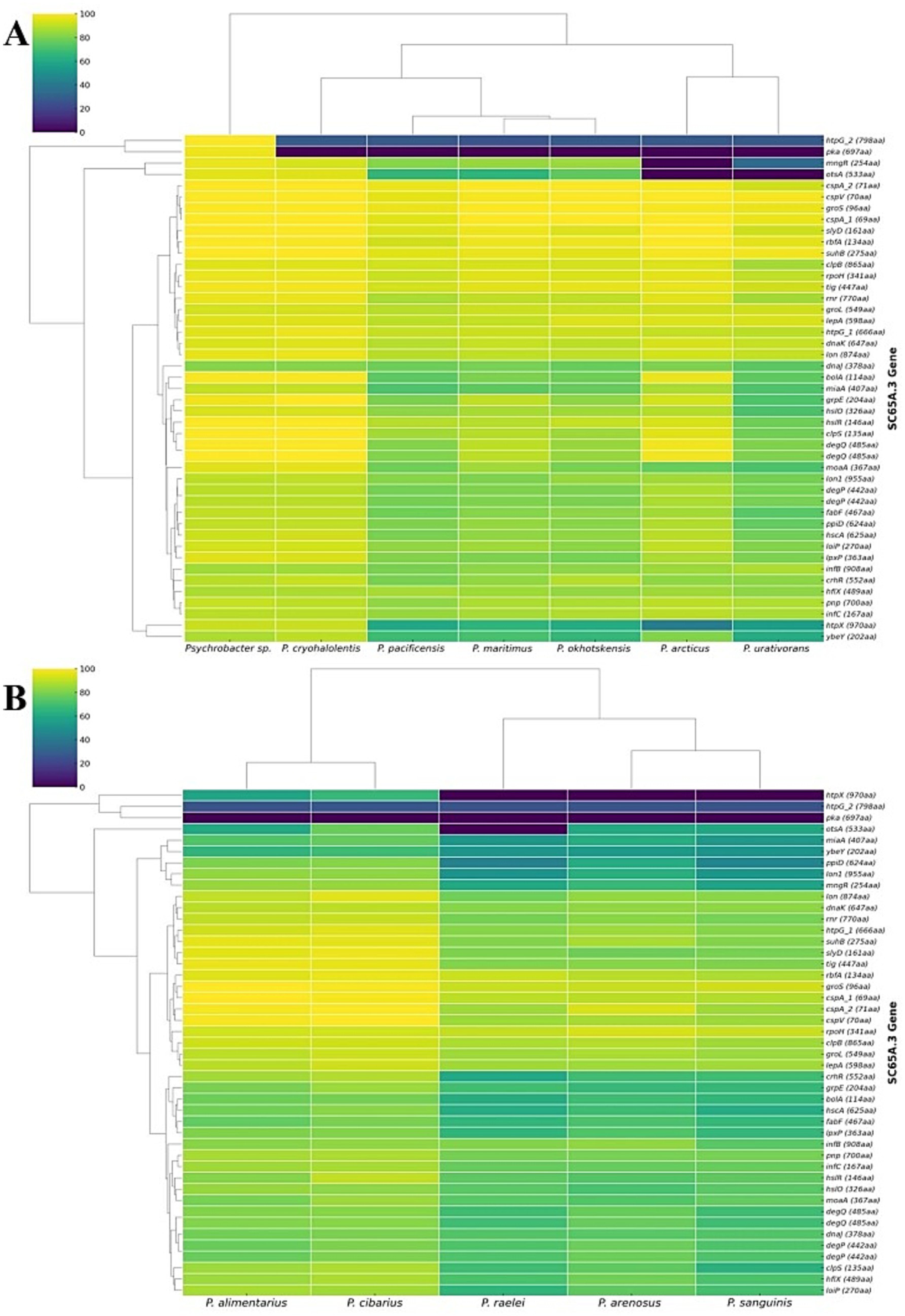

The genes set associated with heat-shock and cold-shock adaptation in Psychrobacter SC65A.3 (Supplementary Table S2) shows a distinct distribution across other Psychrobacter species (Figure 4). Heatmap analysis of these genes compared with those from 7 psychrophilic (Figure 5A) and 5 psychrotrophic strains (Figure 5B) revealed partial interspecies conservation. The highest conservation of thermal-adaptation genes was observed among psychrophilic species with Psychrobacter sp. G from Antarctic seawater (Che et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017), P. cryohalolentis from Siberian cryopeg (Bakermans et al., 2003, 2006) and P. articus from Siberian permafrost (Bakermans et al., 2006), and to a lesser extent with the marine species P. maritimus (Romanenko et al., 2004), P. okhotskensis (Yumoto, 2003), and P. pacificensis (Maruyama et al., 2000) (Figure 5A). Psychrotolerant species generally showed lower conservation of heat-shock and cold-shock genes as compared to SC65A.3 strain, with a closer genome pool profile in the cases of P. alimentarius (Yoon et al., 2005a) and P. cibarius (Jung et al., 2005), both isolated from fermented seafood (Figure 5B).

Figure 5

Heatmap distribution of temperature-shock genes in Psychrobacter genomes as compared to annotated SC65A.3 genes. (A) Psychrophilic Psychrobacter species; (B) Psychrotrophic Psychrobacter species. The annotated heat-shock and cold-shock SC65A.3 genes are indicated in Supplementary Table S2.

Interestingly, the heat-shock genes htpG_2 and pka exhibited very low conservation across all cold-adapted Psychrobacter strains (Figure 5). The htpG_2 gene primarily functions as a molecular chaperone with ATPase activity (Chuang and Blattner, 1993), whereas pka acts mainly as a CoA-binding domain protein, with its heat-response role inferred from mutant phenotypes in E. coli (Ma and Wood, 2011). Heat-shock mngR and cold-shock otsA genes also showed reduced conservation along psychrophilic species, notably in the cases of P. articus (Bakermans et al., 2006; Ayala-del-Rio et al., 2010) and P. urantivorans (Bowman et al., 1996) (Figure 5A), and htpX heat-shock gene was absent in all psychrotrophic strains (Figure 5B). A notable absence was that of the cold-shock otsA gene in P. raelei (Manzulli et al., 2024) among psychrotolerant species, while present in all other Psychrobacter counterparts (Figure 5B).

These clustering patterns (Figure 5) show that SC65A.3 genes are largely conserved across cold-adapted Psychrobacter species, particularly in psychrophilic homologs, but with a notable divergence at the level of specific genes, reflecting functional specialization among these cold-environment bacteria. The absence or low conservation of the htpG_2, pka, and htpX heat-shock genes across all analyzed psychrotrophic species, in addition to cold-shock otsA absence in particular strains, suggests that these organisms rely on molecular mechanisms for thermal adaptation that differ from those used by psychrophilic strains.

4.3 Dual antimicrobial resistance and bioactive potential of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 strain

To date, the antimicrobial resistance of Psychrobacter species is poorly studied (Bowman, 2006). According to the NCBI Taxonomy Database (Schoch et al., 2020), from the 49 Psychrobacter strains identified and accepted as different species, only 18 strains, classified as psychrophiles, were tested for the antibiotic resistance to at least one type of antibiotic, most frequently from the penicillin class, and only five of them have undergone testing to a large set of antibiotics for establishing their antimicrobial resistance profiles (Table 5).

Table 5

| Antimicrobial spectrum | Antimicrobial class | Code ATB | 1 | 2* | 3* | 4* | 5* | 6* | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad spectrum | Penicillins | AMP | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | R | R | R | S | S | R | S | S | R | S | S | |

| CAR | S | S | ⁑R | S | R | R | R § | S§ | S§ | S§ | S | S | R § | ||||||||

| Cephalosporins | CAZ | R | |||||||||||||||||||

| CFM | S | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CTX | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||||

| CPO | S | ||||||||||||||||||||

| KF | R | ⁑S | S | S | S | S | |||||||||||||||

| CPD | S | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbapenems | IPM | S | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fluoroquinolones | CIP | R | S | ||||||||||||||||||

| NA | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | |||||||||||||

| Aminoglycosides | CN | S | S | ⁑S | S | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | |||||||

| SH | R | S | |||||||||||||||||||

| S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | ||||||

| Coumarin glycosides | NV | S | S | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||||||||

| Chloramphenicol | C | S | S | ⁑S | S | S | S | R | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | |||||

| Nitrofurantoin | F | S | S | R | S | R | |||||||||||||||

| Rifampin | RD | R | S | S | S | S | S | R | S | ||||||||||||

| Sulfonamide compounds S3 | S3 | S | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tetracyclines | TE | S | S | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | S | R | |||||

| Trimethoprim/Sulfonamides | W | R | S | ||||||||||||||||||

| Narrow spectrum (G+) | Macrolides | CLR | S | S | S | ||||||||||||||||

| E | S | S | ⁑S | S | R | R | R | S | S | ||||||||||||

| Lincosamide | DA | R | |||||||||||||||||||

| MY | R | R | S | R | R | R | R | S | R | ||||||||||||

| Fatty Acyls | MUP | S | |||||||||||||||||||

| Glycopeptides | VA | R | R | R | S | R | |||||||||||||||

| Anaerobes | Metronidazole | MTZ | R |

Comparative antibiotic susceptibility/resistance profile of Psychrobacter SC65A.3 and other Psychrobacter strains.

1. Psychrobacter SC65A.3 from Scarisoara Cave. Psychrophilic strains (*): 2. P. aquaticus CMS56 (Shivaji et al., 2005); 3. P. immobilis PG1 (Juni and Heym, 1986; Gini, 1990); 4. P. proteolyticus 116 (Romanenko et al., 2002; Shivaji et al., 2004); 5. P. submarinus KMM225 (Romanenko et al., 2002; Shivaji et al., 2004); 6. P. vallis CMS39 (Shivaji et al., 2005). Psychrotrophic strains: 7. P. aestuarii SC35 (Baik et al., 2010); 8. P. alimentarius JG-100 (Yoon et al., 2005a); 9. P. aquimaris SW-210 (Yoon et al., 2005b); 10. P. celer 91 (Yoon et al., 2005c); 11. P. cibarius JG-219 (Jung et al., 2005); 12. P. coccoides F1192 (Shang et al., 2022); 13. P. fozii NF23 (Bozal et al., 2003); 14. P. glaciei BIc20019 (Zeng et al., 2016); 15. P. halodurans F2608 (Shang et al., 2022); 16. P. luti NF11 (Bozal et al., 2003); 17. P. namhaensis SW-242 (Yoon et al., 2005b); 18. P. phenylpyruvicus ACAM535 (Bovre and Henriksen, 1967; Bowman et al., 1996); 19. P. pocilloporae S6-60 (Zachariah et al., 2016). (⁑): clinical strains (Gini, 1990); (§): resistance/susceptibility to penicillin class found in literature; (red /R): resistance; (blue /S): susceptibility; (white): not tested. No significance of the bold values.

Our study reports the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the Psychrobacter SC65A.3 strain to a broad panel of antibiotics. Compared to Psychrobacter species listed in the NCBI Taxonomy Database (Schoch et al., 2020), Psychrobacter SC65A.3 displays the most extensive antibiotic resistance profile, carrying genes associated with resistance to both antibiotics and toxic compounds (Table 4). This finding aligns with a previous genomic study of three Psychrobacter sp. strains, which also identified genes involved in antibiotic and toxic compound resistance, as well as mercury detoxification and metabolism, highlighting the promising potential of this genus for bioremediation applications (Lasa and Romalde, 2017). Moreover, this is the first report providing phenotypic and genotypic data regarding the susceptibility or resistance of a Psychrobacter strain (SC65A.3) to the following antibiotics: ceftazidime, trimethoprim, clindamycin (lincosamide class) and metronidazole (Table 5).

The currently investigated ice cave Psychrobacter strain showed resistance to 10 antibiotics from eight classes, which was mostly dissimilar to other Psychrobacter strains (Table 3, Table 5). Remarkably, SC65A.3 exhibited resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics for Gram-negative infections, such as β-lactams (incl. Third generation cephalosporins), fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides. This particular resistance profile suggests that cold-adapted strains can act as reservoirs of resistance genes, which could be transferred to pathogens under selective pressure, mostly in aquatic or food-related environments.

The presence of ampC gene in SC65A.3 suggests a mechanism for β-lactam resistance through the hydrolysis of β-lactam antibiotics (Mora-Ochomogo and Lohans, 2021). AmpC β-lactamases are enzymes produced by many Gram-negative bacteria and confer resistance to a broad range of β-lactam antibiotics, particularly penicillins, cephalosporins (including cephalotin and ceftazidime) and monobactams. They are typically not inhibited by classical β-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid. Although in many bacteria, ampC is normally expressed at low (basal) levels, certain β-lactams (e.g., cefoxitin, imipenem) can induce ampC expression via regulatory genes such as ampR (Jacoby, 2009). Also, mutations in regulatory regions (e.g., promoter or repressor genes) can lead to constitutive overexpression, causing high-level resistance even without antibiotic exposure (Zaunbrecher et al., 2009). Some AmpC variants are carried on plasmids, allowing horizontal transfer between different bacterial species (Jacoby, 2009). Moreover, AmpC-producing strains often show multidrug resistance, such is the case of our strain, particularly when combined with efflux pumps (harbored by our strain), which reduce intracellular antibiotic concentrations. They can complicate treatment because β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations are often ineffective, and third-generation cephalosporins may fail (Pérez-Pérez and Hanson, 2002; Jacoby, 2009; Bush, 2018).

Moreover, SC65A.3 genome harbored genes associated with phenotypic resistance to quinolones, likely resulting from mutations in the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes, leading to alterations in DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, the primary targets of fluoroquinolones (Redgrave et al., 2014; Manik et al., 2025). These mutations can be transferred via mobile genetic elements (MGEs), contributing to the spread of fluoroquinolone resistance (Sakalauskienė et al., 2025). Rifampin resistance in SC65A.3 strain may be linked to mutations in the rpoB gene encoding the β-subunit of RNA polymerase representing the primary target of this antibiotic (Fluit et al., 2001; Goldstein, 2014; Sudzinová et al., 2023). Resistance to aminoglycosides as well as to other antibiotics could be attributed to the presence of multidrug efflux pump genes (mexA, mexB, oprM, emrK, mdtA, mdtK, macB, mepA, msbA, and macA genes) that could actively expel different antimicrobial agents from bacterial cells (Huang et al., 2022). These genes are frequently located on MGEs (Serio et al., 2017; Naderi et al., 2023). Despite the lack of phenotypic resistance to tetracycline, the SC65A.3 strain harbored the tetA and tetC genes conferring resistance to tetracycline via efflux mechanisms. These genes are frequently located on plasmids and transposons, allowing for their dissemination across diverse bacterial species through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Roberts, 2005; Grossman, 2016). Trimethoprim resistance could be linked to the dfrA gene, through the production of altered target enzymes (Ambrose and Hall, 2021). These genes are commonly associated with integrons, which can capture and mobilize resistance gene cassettes, facilitating their spread (Muziasari et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2023). Although the colistin susceptibility testing was not performed, SC65A.3 harbors the mcr1 gene, responsible for the last resort antibiotic colistin resistance, which is located on plasmids and can be transferred between bacteria, including those of environmental origin, posing a risk for the emergence of colistin-resistant pathogens (Forde et al., 2018; Mondal et al., 2024).

Additional genes such as arsA, arsB, arsC, bcr, emrE, merA, merP, merR1_1, and merR1_2 confer resistance to heavy metals and other compounds (Anedda et al., 2023; Sanchez-Corona et al., 2025). Moreover, arsenic and mercury genes could co-select for resistance to different antibiotics. Also, these genes are often located on plasmids and transposons, contributing to the adaptability and persistence of bacteria in various environments (Pal et al., 2017; Gillieatt and Coleman, 2024).

The presence of these clinically important resistance genes in SC65A.3, a psychrophilic strain, emphasizes the role of environmental bacteria as reservoirs of resistance determinants (Larsson and Flach, 2022; Martak et al., 2024). The mobility of these genes via MGEs facilitates their transfer to pathogenic bacteria, potentially leading to the emergence of MDR pathogens. This underscores the importance of monitoring environmental sources for AMR genes and implementing strategies to mitigate their spread (Bengtsson-Palme et al., 2023).

A study from 2002 on nonclinical Psychrobacter strains revealed their resistance to most penicillins (pilQ, porB, ftsI, nagZ, cpxR, zraS_1, zraS_2, zraR, ampC, ampG) (Romanenko et al., 2002), while a Psychrobacter strain isolated from 35,000-years old permafrost was resistant to tetracycline (tetA, tetC, emrK) and streptomycin (emrE, rpsE, rpsD,rsmG, rpsL, mipA) (Petrova et al., 2009). Also, the sensitivity of various Psychrobacter strains, including three psychrotrophic marine Psychrobacter isolates from the Mediterranean Sea, Egypt, to tetracycline, ampicillin and chloramphenicol among other antibiotics was reported (Dziewit et al., 2013; Jeong et al., 2013; Abd-Elnaby et al., 2016).

The responses of five psychrophilic Psychrobacter strains to the same set of antibiotics differed from that observed in SC65A.3 (Table 5). P. aquaticus CMS56 (Shivaji et al., 2005), P. proteolyticus 116 (Denner et al., 2001; Romanenko et al., 2002), P. submarinus KMM225 (Romanenko et al., 2002) and P. immobilis PG1 associated with fish, processed meat, poultry products (Juni and Heym, 1986) showed sensitivity to ampicillin, oppositely to the Scarisoara strain, while the clinically isolated P. immobilis was resistant to penicillin (Gini, 1990), and P. vallis CMS39 (Shivaji et al., 2005) was resistant to ampicillin and carbenicillin (Table 5). Cephalosporin testing was performed only on the clinically isolated P. immobilis strain, which was sensitive to cephalothin, in contrast to the resistance observed in strain SC65A.3 (Table 5). The Psychrobacter vallis CMS39 strains was sensitive to trimethoprim, unlike the Scarisoara strain which showed resistance to this antibiotic (dfrA, dut, mdtK). Furthermore, SC65A.3 was resistant to (porB, pvdQ, acrR, oprM, mexB, mexA, mdtK, mepA) and spectinomycin (rpsE), while Psychrobacter pocilloporae S6-60, a psychrotrophic bacteria isolated from the mucus of the coral Pocillopora eydouxi, was susceptible to both antibiotics (Zachariah et al., 2016) and also to rifampicin (rpoB, rpoC, rpoA), similar to the psychrothrophic strains P. aestuarii SC35 (Baik et al., 2010), P. coccoides F1192 (Shang et al., 2022) and P. halodurans F2608 (Shang et al., 2022), respectively (Table 5). Meanwhile, the other five analyzed Psychrobacter strains were either sensitive to these antibiotics, or no testing was done (Table 5).

A comparable pattern was observed for trimethoprim resistance (genes dfrA, dut, mdtK), where the only other tested Psychrobacter strain was the psychrophilic P. vallis CMS39, isolated from a cyanobacterial mat in Antarctica (Shivaji et al., 2005) (Table 5). Moreover, SC65A.3 showed resistance to cephalothin, whereas all other tested Psychrobacter strains, including P. immobilis PG1 (Gini, 1990), and the psychrotolerant P. alimentarius PAMC 27889 (Yoon et al., 2005a), P. aquimaris SW-210 (Yoon et al., 2005b), P. celer 91 (Yoon et al., 2005c), P. coccoides F1192 (Shang et al., 2022), P. halodurans F2608 (Shang et al., 2022) and P. namhaensis SW-242 (Yoon et al., 2005b) were susceptible (Table 5). In the case of lincomycin and vancomycin (walR, murG) SC65A.3 showed resistance similar to the majority of other Psychrobacter strains except for P. proteolyticus 116 (Romanenko et al., 2002; Shivaji et al., 2004) and P. aquaticus CMS56 (Shivaji et al., 2005) that were susceptible to lincomycin. Moreover, the psychrotolerant strain P. glaciei BIc20019 isolated from an Arctic glacier ice core (Zeng et al., 2016) showed susceptibility to both lincomycin and vancomycin (Table 5).

Scarisoara SC65A.3 strain has been susceptible to tetracycline, despite the presence of tetracycline resistance genes tetA and tetC (Figure 4, Table 5), while other Psychrobacter strains showed resistance for the most part, with the exception of two psychrophilic and one psychrotolerant strains showing susceptibility. Scarisoara strain was also susceptible to ampicillin, cefotaxime, streptomycin and chloramphenicol, similar to the other various Psychrobacter strains (Table 5). Six Psychrobacter strains isolated from bird guano from the Arctic Spirtsbergen Island were also found to be susceptible to ampicillin, chloramphenicol and tetracycline (Dziewit et al., 2013).

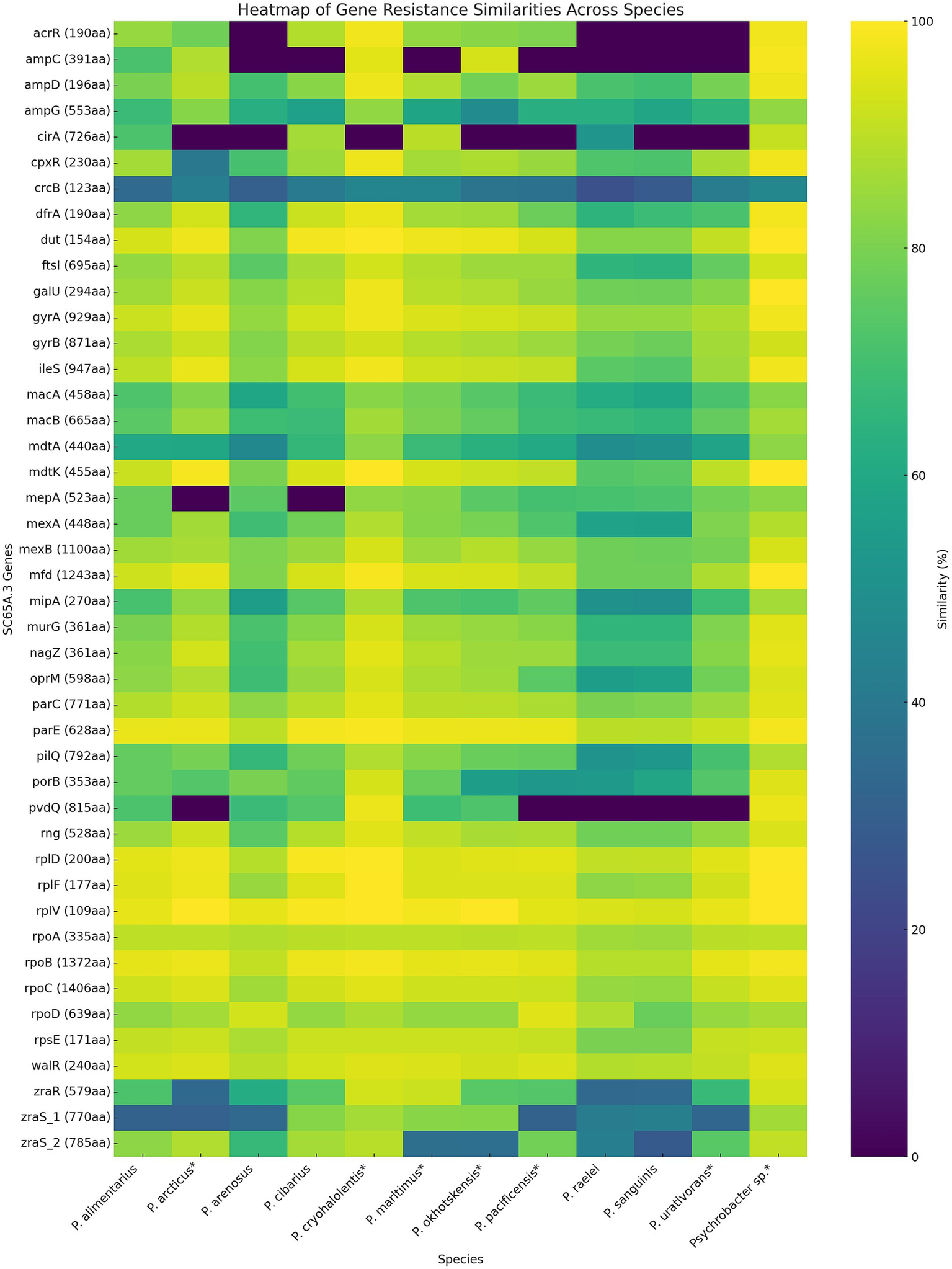

Heatmap comparative analysis of resistance-associated genes across Psychrobacter species (Figure 6) revealed both highly conserved determinants and more variable species-specific elements. The conservation patterns highlight the evolutionary balance between the essential functions of resistance genes and the adaptive pressures shaping their diversification. A subset of genes, including gyrA and gyrB (DNA gyrase), parC and parE (topoisomerase IV) core drug target genes, as well as rpoA, rpoB, rpoC (RNA polymerase subunits), and rplD, rplF, rplV, rpsE (ribosomal proteins), demonstrated strong conservation across all examined species (Figure 6). These findings support the view that such loci function as essential housekeeping genes subject to strong purifying selection, consistent with prior observations that core genes show limited polymorphism in prokaryotes under functional constraint (Bohlin et al., 2017; Joshi et al., 2022). Although mutations in housekeeping genes such as gyrA, rpoB, or rpsL can confer resistance to fluoroquinolones, rifampicins, and macrolides, respectively, the high conservation observed across species reflects the indispensable cellular roles of these genes, which strongly limit tolerated sequence variation (Vester and Douthwaite, 2001; Chiribau et al., 2024).

Figure 6

Heatmap distribution of the antibiotic resistance genes in SC65A.3 and 12 other Psychrobacter species genomes. The ARGs correspond to the phenotypic resistance (Table 4); (*): psychrophilic strains.

Efflux systems represented a second category of resistance determinants across Psychrobacter species’ resistome (Figure 6). Genes such as mexA, mexB, and oprM were broadly conserved, suggesting that multidrug efflux is a widespread strategy among Psychrobacter species and explaining its MDR phenotype (Zgurskaya, 2002; Ayala-del-Rio et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2022). In contrast, some efflux-related genes, such as mdtA, mdtK, and mexA, exhibited moderate variability, likely representing species-specific adaptations in substrate specificity or regulatory mechanisms that mirror the ecological diversity of the analyzed taxa (Kim et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2017; Glavier et al., 2020). Similarly, the ampC β-lactamase and its regulator ampD showed conservation in most species, but with notable divergence in some, suggesting differing potentials for β-lactam resistance (Mallik et al., 2022; Laranjeiro et al., 2025). In contrast, several genes, including cirA (outer membrane receptor), pvdQ (quorum-quenching enzyme), and regulatory elements such as zraR and zraS, exhibited limited similarity or were absent from subsets of species (Figure 6). The patchy distribution and low conservation of these genes point toward niche-specific functions, horizontal acquisition, or lineage-specific losses (Alm et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2018; Rome et al., 2018). For instance, the divergence of Psychrobacter species in these loci likely may reflect adaptation to cold environments, where selective pressures on resistance mechanisms may differ from those acting on mesophilic Psychrobacter.

Several enzymes detected in the SC65.3 genome (Supplementary Table S5) could also play a direct role in the processes underlying antibiotic resistance. Among these, β-lactamases—such as those associated with the Lactamase_B domain (COG2440/KEGG: K01413)—stand out for their ability to hydrolyze the β-lactam ring characteristic of penicillins and cephalosporins (Bush and Jacoby, 2010). Moreover, UppP phosphatase (COG1396/KEGG: K06116), which hydrolyzes undecaprenyl diphosphate (C₅₅-PP) to regenerate undecaprenyl phosphate (C₅₅-P) involved in recycling the lipid carrier essential for cell wall biosynthesis could confer resistance to bacitracin and ensure continuous peptidoglycan synthesis under antibiotic stress (Bernard et al., 2005). Also, MATE family transporters (COG2006/KEGG: K06188) acting as efflux pumps expel antibiotic molecules—such as fluoroquinolones—out of the cytoplasm, using H+ or Na+ gradients as an energy source (Omote et al., 2006). Meanwhile, penicillin amidase (COG2366/KEGG: K07116; EC 3.5.1.97) contributes to the degradation of penicillin-type antibiotics by cleaving the amide bond between 6-aminopenicillanic acid and its acyl side chain (Pan et al., 2022). This enzyme implicated in antibiotic inactivation in clinical Gram-negative bacteria (Cole and Sutherland, 1966) has been isolated from various environmental gene pools (Gabor et al., 2005), although, although to date no documented case in Psychrobacter linking both environmental and clinical origins has been reported. Consequently, mechanisms such as hydrolysis, enzymatic modification, active efflux, and target protection appear to be recurring strategies of antimicrobial resistance (Blair et al., 2015; Munita and Arias, 2016; Reygaert, 2018). The presence of these pathways even in non-pathogenic species like Psychrobacter cryohalolentis highlights a profound ecological adaptation, with a diverse genetic profile shaped by the selective pressures of its natural environment (Blair et al., 2015).

Furthermore, the genome of this cave-derived Psychrobacter highlights its broad biotechnological potential through diverse hydrolytic enzymes also evidenced in the functional profile (Table 1). Notably, the previously reported recombinant lipase Lip2, cloned from this strain by our group (Paun et al., 2024), represents a new catalysts exhibiting both lipolytic and esterase activities, underscoring its applicability in various biocatalytic processes.

Overall, these findings suggest a two-tiered organization of resistance determinants in Psychrobacter SC65A.3 ice cave strain (Figure 6), comprising a conserved core of housekeeping resistance genes for ensuring baseline defense against clinically relevant antibiotics across the genus (yellow), and a variable accessory set contributing to ecological specialization and adaptive flexibility (blue-green). Such patterns underscore the potential of environmental Psychrobacter and related taxa to serve as reservoirs of clinically relevant resistance genes, while also emphasizing the evolutionary fluidity of non-core determinants.

5 Conclusion