- 1Department of Agriculture and Forest Science, Tuscia University, Viterbo, Italy

- 2Department of Plant Protection, Subdepartment of Phytopathology and Mycology, University of Life Sciences, Lublin, Poland

- 3Research Centre for Olive, Fruit and Citrus Crops, Council for Agricultural Research and Economics, Caserta, Italy

- 4Institute of Biosciences and BioResources, National Research Council, Portici, Italy

Recent studies on Fusaria associated with hazelnut have pointed out a role of these fungi as both disease agents and endophytic symbionts, raising concern for the possible mycotoxin contamination of kernels and derived products. Molecular evidence has shown that previous classifications of these isolates as Fusarium lateritium were incorrect, indicating that most of them instead belong to the Fusarium citricola species complex (FCCSC). Based on a set of isolates collected in Italy and Poland, the present work provides a phylogenetic analysis supported by three species delimitation algorithms. The results confirm that all the available hazelnut isolates belong to the FCCSC, and that the discrimination between three currently accepted taxa in this species complex, namely F. aconidiale, F. celtidicola and F. juglandicola, should be reconsidered. The inclusion in our analysis of 25 species identified in the closely related Fusarium tricinctum species complex provides an indication that the statistical methods for species delimitation represent a useful tool for checking the reliability of the species boundaries currently defined in these fungi.

1 Introduction

The genus Fusarium comprises a large and diverse group of filamentous ascomycetous fungi that are ubiquitous in nature, colonizing soil, plant debris, and a variety of other substrates. Many Fusarium species are recognized as major plant pathogens, causing devastating diseases across a wide range of crops worldwide (Todorović et al., 2023). Recent taxonomic studies have revealed that the genus Fusarium comprises more than 400 phylogenetically distinct species, grouped into over 30 species complexes and several monotypic lineages (Hof and Schrecker, 2024). These advances, together with ongoing revisions based on molecular data, continue to reshape the taxonomy of the genus through the description of new species and the redefinition of phylogenetic relationships (Crous et al., 2022; O’Donnell et al., 2022; Ulaszewski et al., 2025). Although morphological features provide valuable diagnostic information, their reliability for species-level identification in Fusarium is limited by high phenotypic plasticity and overlapping traits among species, often influenced by culture conditions and environmental factors. This morphological convergence, or synapomorphy, where distantly related taxa share similar characters, has historically complicated Fusarium taxonomy and the species identification (Stępień, 2014; Manganiello et al., 2019; Crous et al., 2022). The integration of molecular approaches, particularly DNA barcoding and multilocus sequencing, has therefore become essential for accurate species delineation, providing greater resolution within cryptic or recently diversified lineages (Summerell, 2019; Sandoval-Denis et al., 2018; Lombard et al., 2021; Stoeva et al., 2023; Kamil et al., 2025).

The economic impact of hazelnut (Corylus avellana) is increasing worldwide, with an estimated global production of 1.15 million tons in 2023; Turkey is the leader country, producing as much as 56% of shelled hazelnuts, followed by Italy with a market share of about 9% (FAOSTAT; www.fao.org/statistics/en, accessed on 30 November 2025). A major concern for product storage and marketing is represented by fungi causing kernel contamination with a wide array of mycotoxins, for which there is increasing attention by the control authorities (Salvatore et al., 2023). In this respect, the role by Fusarium spp. deserves more-in-depth assessments in light of their reputation as producers of mycotoxins, such as trichothecenes and enniatins, and the increasing number of reports in association with this crop (Munkvold et al., 2021; Gautier et al., 2020; Zimowska et al., 2024). Indeed, Fusaria isolated from hazelnut represent a meaningful example of how traditional morphology-based taxonomic schemes are insufficient for accurate species identification and have often led to misclassification. Early investigations on the nut gray necrosis (NGN) affecting hazelnuts in the Viterbo area (Central Italy) carried out in the first decade of the 2000s identified Fusarium lateritium as the causal agent (Vitale et al., 2011). However, genomic evidence from a more recent study questioned this identification, highlighting a closer affinity of these isolates with the Fusarium tricinctum species complex (FTSC) (Turco et al., 2021). Following the characterization of a new lineage related to the FTSC, designated as Fusarium citricola species complex (FCCSC) (Sandoval-Denis et al., 2018), two endophytic isolates from hazelnut collected in Poland were identified as members of this complex (Zimowska et al., 2024). Although this inference was later confirmed after the whole genome sequencing of one of these isolates (Becchimanzi et al., 2025), the limited number of reference strains available at that time did not allow to conclusively assign them to either Fusarium celtidicola or Fusarium juglandicola. Similar uncertainty regarding the separation between these species also emerged in a recent phylogenetic study based on strains available from reputed mycological collections, which had been classified as F. lateritium and found to rather belong to either the FTSC or the FCCSC (Costa et al., 2024). In this context, the availability of a broader set of isolates from both Italy and Poland enabled us to perform a more comprehensive phylogenetic reconstruction supported by species delimitation analyses. These species delimitation methods provide a valuable tool for resolving complex taxonomic relationships and detecting cryptic diversity, as demonstrated in other Ascomycota lineages (Liu et al., 2016; Bustamante et al., 2019; Maharachchikumbura et al., 2021; Becchimanzi et al., 2021; Sklenář et al., 2022; Dissanayake et al., 2024; Zapata et al., 2024). In this framework, the present study aims to clarify the taxonomic position of Fusarium isolates associated with hazelnut and to evaluate the validity of the current species boundaries within the F. citricola species complex (FCCSC).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Fusarium isolates

In May and June 2023, a field survey was carried out in three hazelnut orchards located in the Viterbo area (Central Italy), to investigate the presence of early NGN symptoms. Twenty five symptomatic hazelnut samples, collected from cultivar ‘Nocchione’ and ‘Tonda Romana’, were sealed in sterile plastic bags and brought to the Plant Pathology Laboratory of the Tuscia University in Viterbo. Briefly, hazelnut inner kernel sections were surface-sterilized with 3% sodium hypochlorite for 3 min, rinsed twice with sterile distilled water, and dried under laminar flow. One-centimeter sections from both healthy and symptomatic tissues were aseptically placed onto potato dextrose agar (PDA, Dinkelberg analytics, Gablingen, Germany) plates and incubated at 25 ± 1 °C for 5–7 days. The pure fungal cultures were obtained through serial transfer of emerging colonies onto fresh PDA plates and further used for morphological and molecular analyses. For morphological characterization, single hyphal tips were transferred to plates containing the standard PDA and oatmeal agar (OA, Condalab, Madrid, Spain), which were incubated at 25 °C in the dark. After 10 days, the morphology of the colony was observed. Morphology of the conidia was examined by growing the isolates on synthetic nutrient agar (SNA), prepared according to Nirenberg (1976). Plates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark at 100% relative humidity. Observations on the conidial morphology and size were carried out at 100x magnification through a microscope (Leitz).

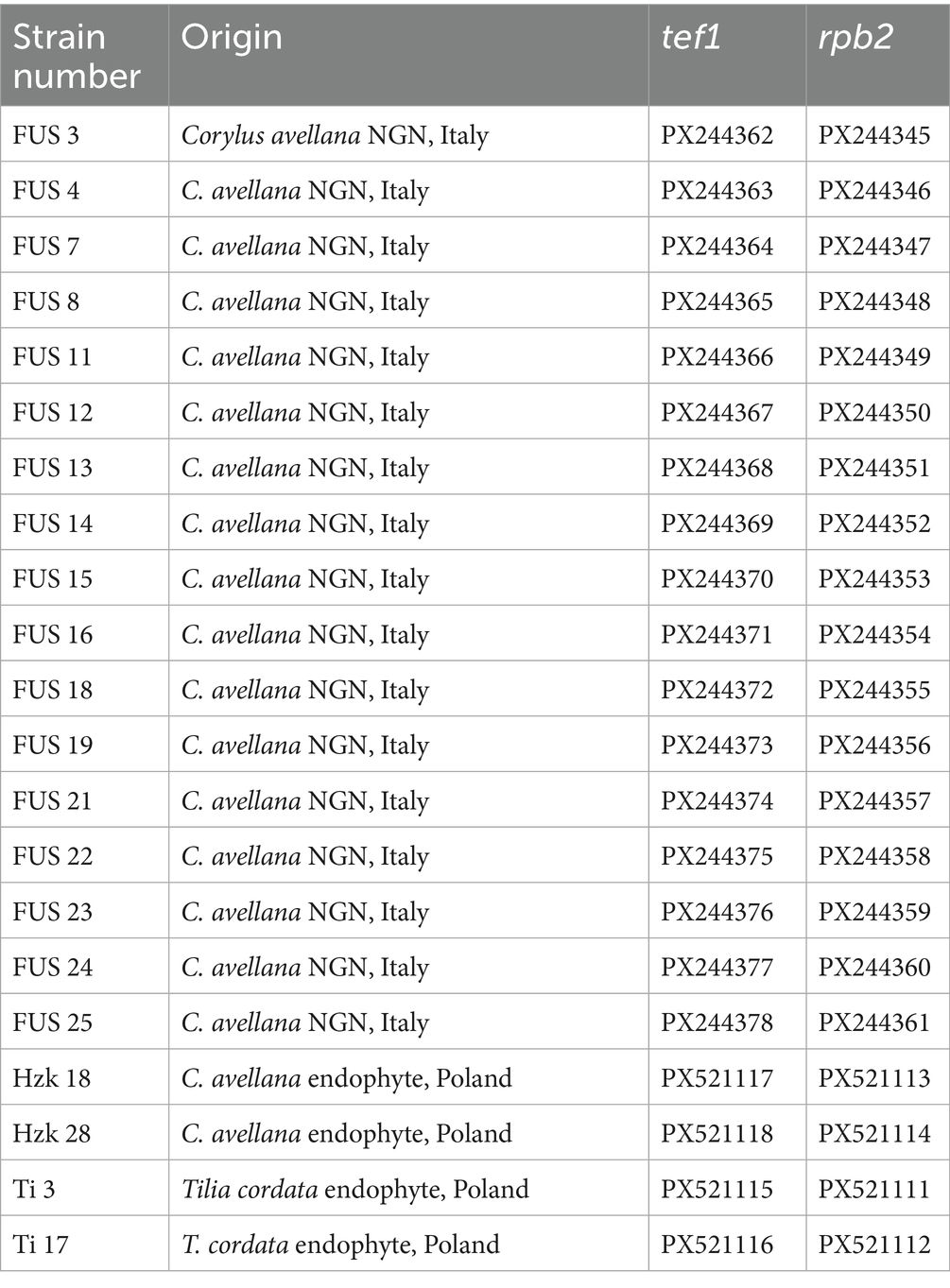

In addition to those available from our previous study (Zimowska et al., 2024), four more endophytic isolates conforming to the FCCSC were collected from secondary branches of both hazelnut and small-leaved linden (Tilia cordata) in the Kraków area (Southwest Poland), following the procedure described in the mentioned reference. The details concerning the isolation sources and the GenBank accession numbers of the DNA barcode sequences used in this study are indicated in Table 1.

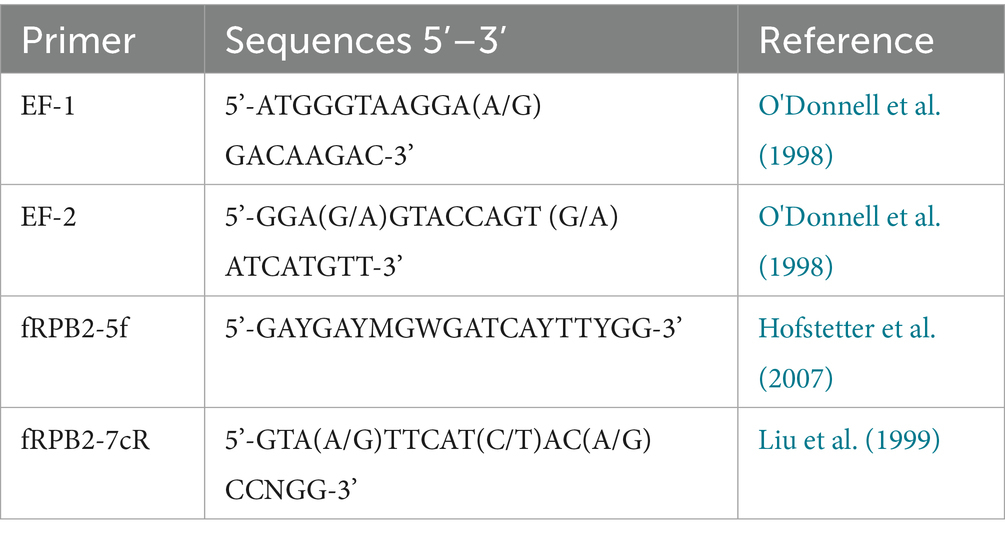

Table 1. Fusarium isolates obtained in this study and their DNA barcode sequence GenBank accession numbers.

2.2 DNA extraction and PCR amplification for molecular characterization

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from fresh, filtered mycelium obtained from pure colonies grown in 50 mL tubes containing potato dextrose broth (PDB) using the Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Fisher Molecular Biology, Rome, Italy). Molecular characterization was carried out following published protocols (O'Donnell et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1999; Hofstetter et al., 2007), through amplification of the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef-1) and the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (rpb2) gene regions, using the primers listed in Table 2. For each PCR reaction, 5 ng of gDNA was used as a template in a final volume of 25 μL, containing 2 × PCRBIO HS Taq DNA Polymerase (PCR Biosystems, UK) and 0.5 μM of both forward and reverse primers. The thermal cycling program for tef-1, using primers EF-1 and EF-2, consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. For rpb2 amplification, using primers fRPB2-5f and fRPB2-7cR, the program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 60 s, annealing at 57 °C for 75 s, and extension at 72 °C for 60 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Two μL of the amplified products were analyzed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, while the remaining products were sent to Macrogen Europe (Milan, Italy) for Sanger sequencing.

2.3 Phylogenetic and species delimitation analyses

All the collected Fusarium isolates were submitted to a detailed phylogenetic analysis, along with 60 strains belonging to the FCCSC and the FTSC whose sequences are available in the GenBank database (Supplementary Table 1); F. lateritium NRRL 13622 was included as an outgroup. The original sequences were edited using UGENE v48.1 (Okonechnikov et al., 2012), concatenated, and aligned with MUSCLE v3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004). The resulting alignment file was used as input to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree with RAxML-HPC v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014), employing the GTRGAMMAI substitution model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized with FigTree v1.4.41 and further edited with Inkscape v0.92.2

Species delimitation analysis was performed employing the distance-based Automatic Barcode Gap Discovery (ABGD), the Generalized Mixed Yule-Coalescent (GMYC) model, and the Poisson Tree Processes method with multi-rate (mPTP) implementations, using RAxML output tree as input. In particular, the ABGD algorithm splits sequences based on break points in pairwise genetic distances (“barcode gaps,” Puillandre et al., 2012). The mPTP algorithm (Kapli et al., 2017) inspects a substitution-based, non-ultrametric phylogenetic tree to detect changes in branching rates. These rates, modeled as a Poisson process, occur randomly at a relatively constant rate within species and more slowly between species, allowing the algorithm to delineate species boundaries. The GMYC algorithm uses a time-calibrated (ultrametric) tree to find the point where the branching pattern shifts from splits between species to merge among individuals of the same species; thus, it is really sensitive to recent divergence when they tend to over-split. For the ABGD analysis, the parameters were set to test variability (P) between 0.001 (Pmin) and 0.1 (Pmax), standard for fungal ITS or protein-coding markers (Puillandre et al., 2012), with a minimum gap width of 0.1, employing the Kimura 2-parameter model and 50 screening steps. For the mPTP approach, 50 million generations were employed with MCM or ML algorithm, with sampling every 1,000 generations, using the minimum branch length calculated from each tree. For the GMYC analysis, an ultrametric tree was constructed on BEAST2 v2.7.7 (Bouckaert et al., 2014), setting the gamma site model with GTR + G + I as substitution, the Yule prior with a relaxed molecular clock, and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) run for 50 million generations, sampled every 1,000 generations. Convergence and effective sample size (ESS) higher than 200 was checked using Tracer v.1.7.2 (Rambaut et al., 2018) and the maximum credibility clade tree was obtained with Treeannotator v2.7.7 (Bouckaert et al., 2014) applying the mean heights parameter and discarding the first 10% of the trees as burn-in period. The resulting tree was then imported into the R environment and the GMYC analysis was performed using the splits package using the single threshold approach (Fujisawa and Barraclough, 2013).

3 Results

3.1 Morphological features

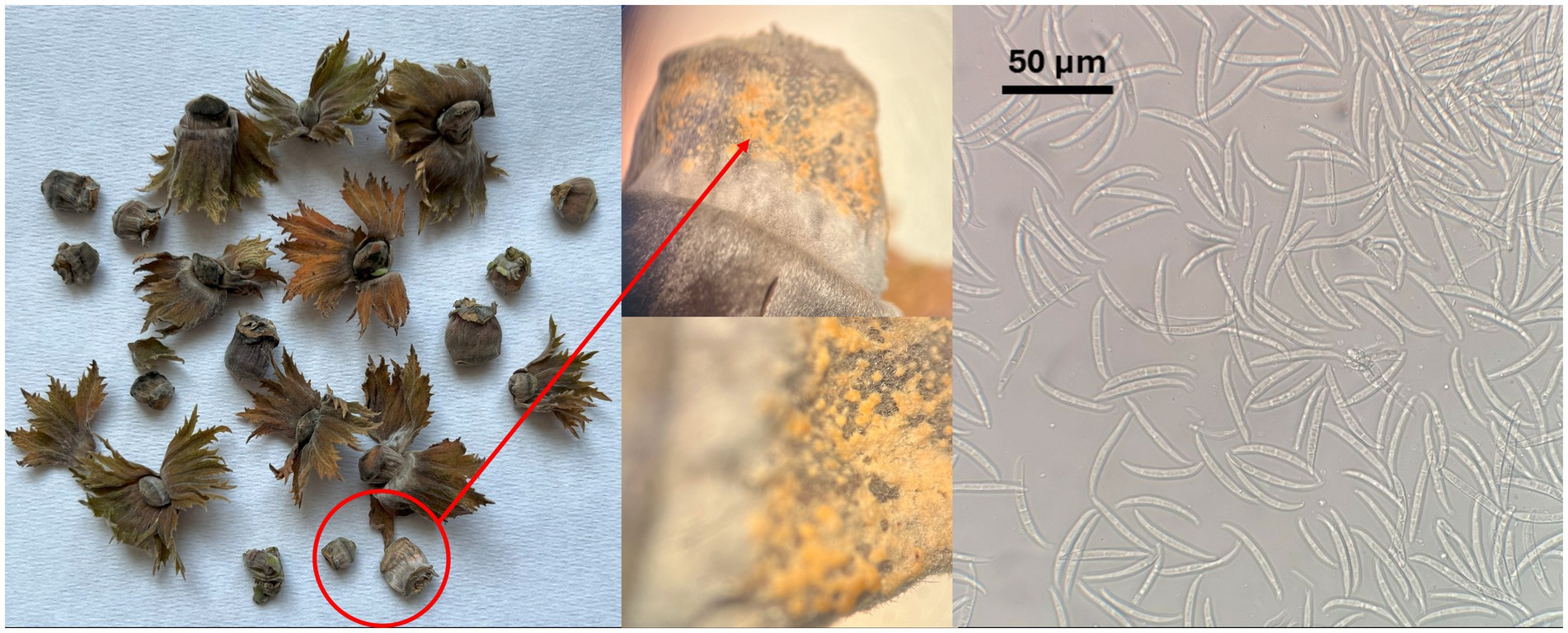

The hazelnut samples collected in orchards located in the Viterbo area from NGN symptomatic plants showed the presence of orange to light brown sporodochia on the fruit surface, indicating active fungal growth; these fruiting structures contained numerous hyaline, multiseptate, crescent-shaped macroconidia (Figure 1). The isolations done from the inner kernel tissues consistently yielded Fusarium from all the samples examined; a total of 17 isolates were recovered and stored in pure culture for the subsequent assessments. Four more Fusarium isolates exhibiting similar morphological features were recovered in the Kraków area, respectively two from hazelnut and two from linden tree, within the cooperative work in progress concerning endophytic associates of forest trees (Nicoletti and Zimowska, 2023). Notably, no symptoms referable to NGN were observed in the course of inspections carried out in Southern Poland in summer 2025.

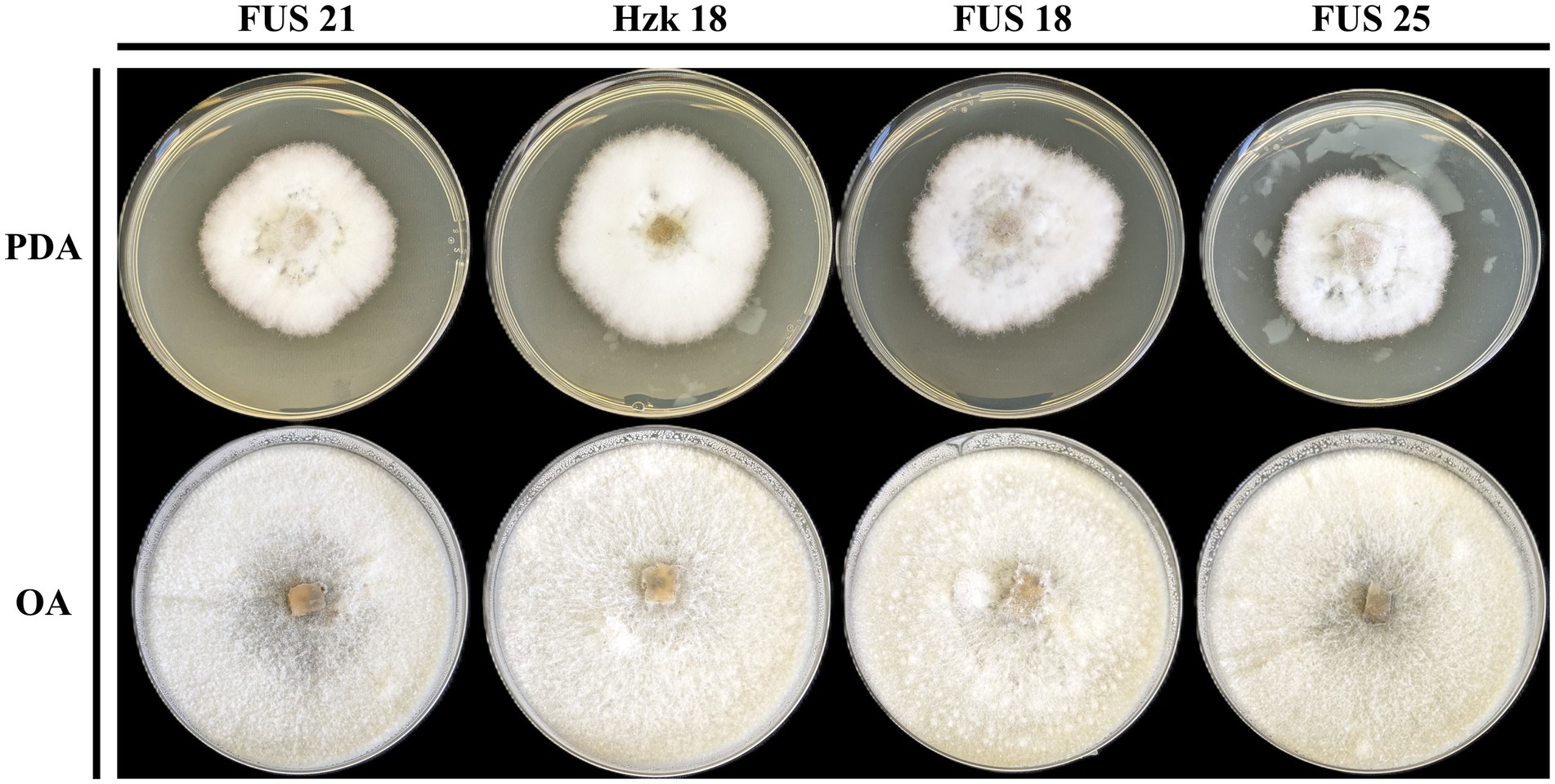

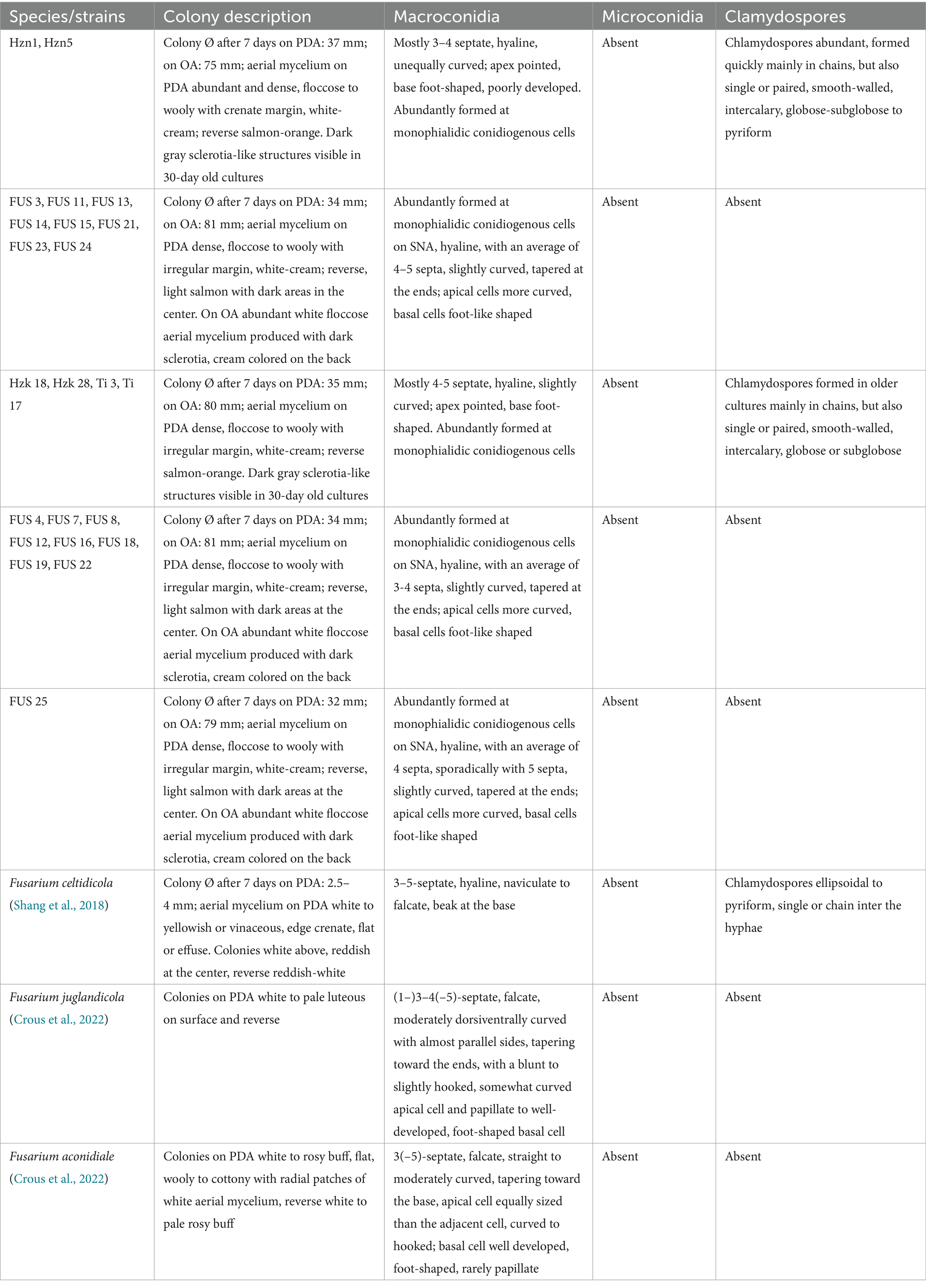

When grown in axenic culture on PDA, the morphological characteristics of both pathogenic and endophytic isolates were comparable and consistent with the description previously reported for Polish isolates (Zimowska et al., 2024). On OA, radial growth was more pronounced; however, sporulation was generally reduced, and only minor differences in colony color and morphology were observed (Figure 2). On SNA, abundant macroconidia were produced from monophialidic conidiogenous cells. These conidia were hyaline, multicellular, typically with three to five septa, slightly curved and tapering toward both ends. The apical cells were more distinctly curved, whereas the basal cells exhibited a characteristic foot-shaped morphology (Figure 3). Throughout the 14-day incubation period, no pigmentation of the medium was detected, and microconidia were not produced. Chlamydospores were absent in the Italian isolates, whereas they were consistently observed in all the Polish isolates examined (Figure 4). The relevant morphological features as assessed in comparison with the descriptions of the reference FCCSC species, and reported for homogeneous groups of isolates, are resumed in Table 3.

Figure 2. Colony morphology of representative isolates on PDA and OA after 10-day incubation at 25 °C.

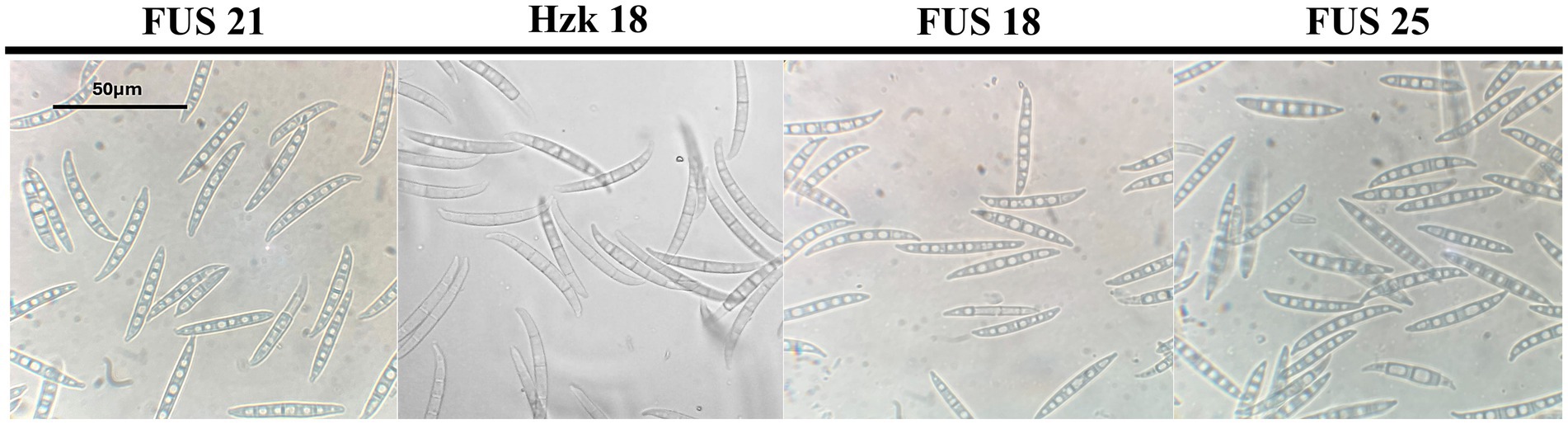

Figure 3. Morphology of macroconidia of isolate FUS 21, Hzk 18, FUS 18, and FUS 25 after 2-week incubation on SNA at 25 °C.

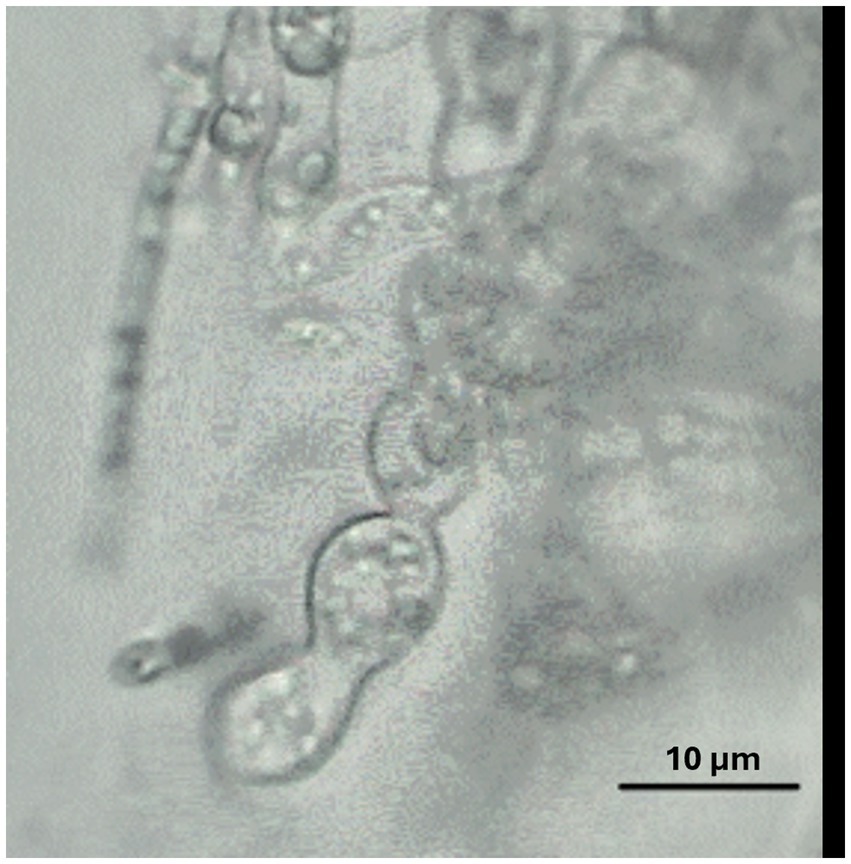

Table 3. Main morphological characters of the groups of isolates delimited in the phylogenetic analysis in comparison with the related FCCSC species.

Figure 4. Chlamydospores of isolate Hzk 18 produced on SNA after 2-week incubation at 25 °C. Scale bar = 10 μm.

3.2 Phylogenetic and species delimitation analyses

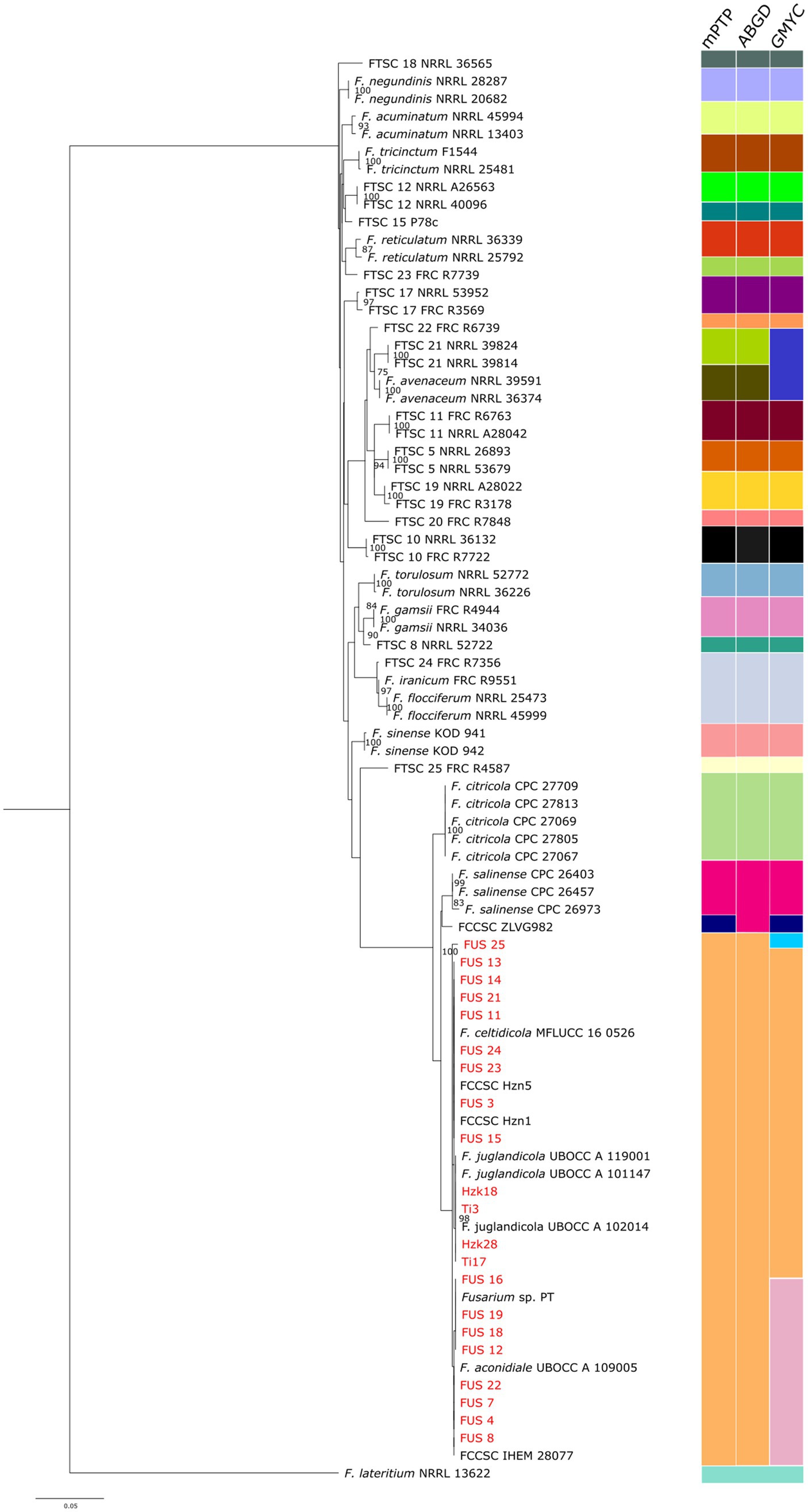

The phylogenetic analysis based on the selected DNA markers (Figure 5) confirmed that all strains analyzed belong to the Fusarium citricola species complex (FCCSC), although they exhibit a certain degree of intra-clade variation. The 17 strains collected from the Viterbo area are positioned in the lower portion of the dendrogram and form four main clusters. The first cluster consists exclusively of isolate FUS 25; the second includes the type strain of F. aconidiale together with isolate PT, previously assigned to the FTSC (Turco et al., 2021); the third group includes F. celtidicola and the endophytic isolates from the Lublin area; and the fourth occupies an intermediate position, encompassing F. juglandicola and the isolates from the Kraków area. As a whole, the FCCSC and its related isolates are clearly separated from the rest of the strains, reinforcing their distinction from the FTSC.

Figure 5. Species delimitation of the combined tef-1 and rpb2 sequences of 81 Fusarium isolates according to ABGD, mPTP, and GMYC algorithms. Bootstrap values indicating the robustness of the clustering are reported as node values ≥70.

This separation is consistently supported by all the three independent species-delimitation algorithms (Figure 5). In fact, both mPTP and ABGD assigned all the 21 isolates to a single species-level unit, whereas GMYC identified three distinct entities. The first GMYC group comprised a single NGN isolate (FUS 25), which forms an independent lineage congruent with its unique placement in the phylogenetic tree. The second group included eight Italian NGN isolates, all the Polish isolates, and the strains identified as F. celtidicola and F. juglandicola. The third cluster encompassed the remaining NGN isolates, including isolate PT, isolate IHEM 28077, and the type strain of F. aconidiale. All the three delimitation methods consistently recognized F. citricola and F. salinense as distinct species, but the placement of isolate ZLVG982 was discordant. In the ABGD analysis this isolate grouped with F. salinense, whereas in both mPTP and GMYC it formed an independent lineage, supporting our earlier inference that it may represent a separate, as-yet undescribed species (Zimowska et al., 2024).

Within the FTSC, the three algorithms are generally concordant, consistently recovering well-supported clades corresponding to F. acuminatum, F. tricinctum, F. torulosum, F. reticulatum, F. avenaceum, and F. gamsii. Minor discrepancies concern the discrimination among F. iranicum, F. flocciferum and FTSC 24, which were grouped as a single taxon by all three delimitation methods, as well as isolate FTSC 21, which clustered together with F. avenaceum into a single operational unit in the GMYC analysis. Also noteworthy was the case of FTSC 25, represented by a single strain, which was placed in an intermediate position at a seemingly equal phylogenetic distance from both the FCCSC and the other FTSC lineages. This finding, consistent with our previous phylogenetic results (Becchimanzi et al., 2025), deserves further examination if additional isolates belonging to this provisional taxon become available.

3.3 In-depth investigation of K2P genetic distance

Pairwise Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) distance matrices derived from the ABGD analysis confirmed a clear discontinuity between the FCCSC and FTSC species complexes (Supplementary Figure 1). Inter-complex distances ranged from 0.0614 to 0.0955, with a median of 0.0767, delineating a clear barcode gap that separates the two complexes (Supplementary Table 2). By contrast, intra-complex distances were much smaller: within the FTSC, distances were higher (Q3 = 0.0406, i.e., the 75th percentile of the dataset, meaning that 75% of all pairwise distances are smaller than this value and 25% are larger; max = 0.0560), reflecting greater internal structuring associated to several distinct, recognized species-level entities. Within the FCCSC, values remained very low, with a median of 0.0036, Q3 of 0.0229 and max distance of 0.0279 (Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Table 2). These results confirm a strong genetic separation between the two complexes, with no overlap between their intra- and inter-group distance distributions. This absence of overlap represents a clear “barcode gap”, quantitatively reinforcing the distinct evolutionary identity of the FCCSC and its separation from the FTSC.

When going deeper into the FCCSC, the K2P distance matrix revealed a cohesive but internally structured lineage composed of four genetic groups: F. citricola, F. salinense, Fusarium sp. ZLVG982, and a larger assemblage including F. aconidiale, F. celtidicola, F. juglandicola, and the Italian and Polish isolates (referred to as “the FCCSC comprehensive taxon, or FCCSC-CT”), in line with our previous phylogenetic consideration. Pairwise distances within these groups were uniformly low, with no variation observed in F. citricola (all distances = 0, indicating that these five isolates are genetically identical for the loci analyzed), and slight variability observed in F. salinense (median = 0.0048; max = 0.0048) and in FCCSC-CT isolates (median = 0.0024; Q3 = 0.0036, max = 0.0060). Between-group comparison within the FCCSC also yielded very low divergence, with median values ranging from 0.016 to 0.023 K2P (Supplementary Table 2). The smallest inter-group distance was recorded between ZLVG982 and F. salinense (median = 0.0144), whereas the largest occurred between F. citricola and F. salinense (median = 0.0230). The FCCSC-CT consistently showed low differentiation from all the other FCCSC subgroups (median = 0.0168-0.0229). Their internal distances (median = 0.0024) fall well within the expected intraspecific range, while their inter-group divergences (0.017-0.023) suggest incipient speciation rather than established separation. Collectively, these data indicate that the FCCSC-CT constitutes a single, genetically cohesive lineage distinct from, but closely related to, F. citricola, F. salinense and ZLVG982; together, they form a compact species complex characterized by shallow internal divergence and strong inter-complex separation. Regarding FTSC 25, which is intermediate between FTSC and FCCSC, the distance indicates that this provisional taxon is genetically closer to the former complex. Specifically, the distances from the FTSC were: min distance = 0.0333, max distance = 0.0560, and median = 0.0430; while higher values could be determined toward the FCCSC: min distance = 0.0674, max distance = 0.0739, and median = 0.0700.

4 Discussion

The genus Fusarium includes a highly diverse assemblage of plant pathogens, endophytes, and saprotrophs occupying a wide range of ecological niches. Its remarkable morphological plasticity and the frequent occurrence of cryptic species have long complicated species delimitation (Summerell, 2019; Crous et al., 2022). Traditional morphology-based identification is often unreliable, as diagnostic traits may vary with culture conditions or overlap among distinct taxa. The introduction of molecular tools has greatly refined Fusarium taxonomy, leading to the recognition of several major species complexes through multilocus phylogenetic approaches (O’Donnell et al., 2015; Lombard et al., 2015). However, despite these advances, many recently described species are still based on a limited number of isolates, raising questions about the robustness of their typification and the stability of species boundaries.

Among these, the FCCSC represents one of the most recently delineated and least resolved groups, characterized by low interspecific divergence and overlapping morphological features (Crous et al., 2022; Costa et al., 2024). Within this framework, the present study provides an integrative assessment of FCCSC isolates from Italy and Poland associated with hazelnut, combining morphological observations with phylogenetic inference and three complementary species delimitation methods.

Consistent with previous uncertainties, morphological variation was observed among the analyzed isolates, none of which fully matched the original descriptions of F. celtidicola, F. juglandicola, or F. aconidiale (Shang et al., 2018; Crous et al., 2022). Moreover, the uneven micromorphological traits did not correspond clearly to their phylogenetic distribution. The cluster centered on the type strain of F. celtidicola included isolates lacking microconidia and medium pigmentation, with only a few producing chlamydospores. Conversely, the four endophytic isolates associated with F. juglandicola all produced chlamydospores, a feature absent from the species’ original description. Finally, the eight isolates related to F. aconidiale were most consistent with its morphological profile, although they exhibited macroconidia with a lower average number of septa.

The examination of phylogenetic relationships through genetic distances and species delimitation analyses does not support the current discrimination among these species within the FCCSC. Delimiting species boundaries in recently diversified fungal lineages is inherently challenging, particularly in complexes such as the FCCSC, where low sequence divergence, incomplete lineage sorting, and possible gene flow can obscure the evolutionary patterns, as observed in other Fusarium species complex (O’Donnell et al., 2009; Vu et al., 2019). To explore these boundaries, we applied three complementary species delimitation algorithms, ABGD, mPTP, and GMYC, each based on distinct theoretical and evolutionary assumptions. Although they produced partially divergent outcomes, their combined results provide a coherent picture of a genetically cohesive yet internally structured species complex.

The more conservative ABGD and mPTP methods identified a single species-level taxonomic unit including all isolates within the FCCSC, since they failed to detect any significant gap and branching rate shifts within the FCCSC isolates, while clearly discriminating between the two complexes.

Despite being designed to infer species boundaries using a single-locus gene tree, the GMYC model (Fujisawa and Barraclough, 2013) has been extensively used in defining species boundaries in several taxonomic groups using concatenated loci (Liu et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2018; Hilário et al., 2021; Dissanayake et al., 2024; Zapata et al., 2024). Here, GMYC splits the FCCSC-CT into three subgroups, most likely identifying subpopulation structures, rather than real differentiated species. This finer subdivision is consistent with the model’s sensitivity to shallow population-level divergence and has been frequently reported in other Fusarium complexes where recent diversification conceals clear species boundaries (Lombard et al., 2015; Crous et al., 2022). The different outcomes among the three algorithms reflect their distinct underlying principles. While the distance- and rate-based methods (ABGD and mPTP) emphasize clear genetic discontinuities, the coalescent-based GMYC is more sensitive to recent divergence and population structure. The slight over-splitting observed with GMYC has similarly been reported in other Fusarium complexes such as the F. incarnatum–equiseti and F. tricinctum s.c. (Marin-Felix et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2019).

Quantitative analyses of K2P distances independently supported the species delimitation results, confirming a clear genetic gap between the FCCSC and the FTSC. Inter-complex distances were more than three times higher than those observed within the FCCSC, underscoring their distinct evolutionary separation.

Within the FCCSC, genetic variation remained minimal: intra-group distances were an order of magnitude lower (median = 0.002–0.005) than the interspecific thresholds typically recognized for Fusarium (0.04–0.06; Vu et al., 2019), indicating strong internal cohesion. Four main genetic clusters were identified, F. citricola, F. salinense, Fusarium sp. ZLVG982, and the broad FCCSC-CT assemblage. The latter group displayed very shallow divergence consistent with intraspecific variability rather than distinct speciation, in line with the GMYC results. Isolate ZLVG982 from Slovenia occupied an intermediate position, suggesting an incipient lineage possibly reflecting early divergence or limited geographic isolation. Overall, the concordant outcomes of ABGD and mPTP, supported by low K2P distances, indicate that the FCCSC represents a single monophyletic lineage with shallow but structured intraspecific diversity.

However, as the analyses were based on two loci (tef1-α and rpb2) and on a defined number of Italian and Polish isolates, additional genomic data, together with an expanded sampling across hosts and regions, will be essential to determine whether the observed variability reflects early speciation or polymorphism within a recently diversified species complex. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was comprehensive of all the strains currently ascribed to the three species in question within the FCCSC. Fusarium juglandicola has also been identified in Poland in leaves of mistletoe (Viscum album subsp. austriacum) (Jankowiak et al., 2023) and on diseased stems of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) seedlings (Jankowiak et al., 2025), as well as in Slovakia on larvae and inside galls of the cecidomyid midges Asphondylia echii and Lasioptera rubi (Pyszko et al., 2024); unfortunately, the pair of marker sequences required for phylogenetic assessments were not available in GenBank for including these strains in our analyses. Despite these limitations, the close genetic relatedness of isolates collected from both cultivated and wild hosts suggests that members of the FCCSC are widespread and potentially share an endophytic phase in hazelnut. In line with the recent observations by Costa et al. (2024), many strains previously classified as F. lateritium likely belong to the FCCSC, reinforcing the need for a comprehensive taxonomic revision and a re-evaluation of the species boundaries among F. celtidicola, F. juglandicola, and F. aconidiale.

5 Conclusion

The results of this study provide new insights into the taxonomy of the FCCSC, demonstrating that the currently accepted separation among F. aconidiale, F. celtidicola, and F. juglandicola is not supported by molecular and distance-based evidence. Phylogenetic reconstruction, species delimitation analyses (ABGD, mPTP, and GMYC), and pairwise K2P distance comparisons consistently indicate that these taxa, together with the Italian and Polish isolates, form a single, genetically cohesive lineage characterized by shallow but structured intraspecific diversity. While ABGD and mPTP converged on a single species-level unit, GMYC detected limited substructure likely reflecting population-level differentiation or incomplete lineage sorting.

These findings highlight that, although the FCCSC is clearly distinct from the FTSC, internal diversification within the FCCSC remains below the interspecific thresholds typically recognized for Fusarium. The observed genetic cohesion suggests that several taxa currently regarded as separate species may instead represent variants of a single evolutionary lineage. More broadly, the study illustrates that while species boundaries in some Fusarium s.c. are robust and reproducible across methods, others remain ambiguous. This underscores the need to expand taxon sampling and adopt integrative approaches that combine molecular, morphological, and ecological data. In this respect, distance-based and model-based species delimitation algorithms provide a valuable framework for reassessing recently described taxa and for verifying the stability of species boundaries as the ongoing exploration of Fusarium diversity continues.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, several.

Author contributions

FB: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. ST: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation. NU: Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BA: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Data curation. AC: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. RN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Writing – original draft. LM: Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was carried out within the Agritech National Research Center and received funding from the European Union Next-Generation EU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) -MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.4 -D. D. 1032 17/06/2022, CN00000022). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out within the framework of the Ministry for University and Research (MUR) initiative “Department of Excellence” (Law 232/2016) DAFNE Project 2023-27 “Digital, Intelligent, Green and Sustainable” (acronym: D. I. Ver. So). All the bioinformatics calculations and analyses were performed at the DAFNE HPC Scientific Computing Center of the Università degli Studi della Tuscia. Part of this research was carried out within the supply chain project “Quantitative valorization of dried fruit (hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts and walnuts)” in collaboration with ASSOFRUTTI.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1741069/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Becchimanzi, A., Zimowska, B., Calandrelli, M. M., De Masi, L., and Nicoletti, R. (2025). Genome sequencing of a Fusarium endophytic isolate from hazelnut: phylogenetic and metabolomic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26:4377. doi: 10.3390/ijms26094377,

Becchimanzi, A., Zimowska, B., and Nicoletti, R. (2021). Cryptic diversity in Cladosporium cladosporioides resulting from sequence-based species delimitation analyses. Pathogens 10:1167. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091167,

Bouckaert, R., Heled, J., Kühnert, D., Vaughan, T., Wu, C.-H., Xie, D., et al. (2014). BEAST 2: a software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10:e1003537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003537,

Bustamante, D. E., Oliva, M., Leiva, S., Mendoza, J. E., Bobadilla, L., Angulo, G., et al. (2019). Phylogeny and species delimitations in the entomopathogenic genus Beauveria (Hypocreales, Ascomycota), including the description of B. peruviensis sp. nov. MycoKeys 58:47. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.58.35764,

Costa, M. M., Sandoval-Denis, M., Moreira, G. M., Kandemir, H., Kermode, A., Buddie, A. G., et al. (2024). Known from trees and the tropics: new insights into the Fusarium lateritium species complex. Stud. Mycol. 109, 403–450. doi: 10.3114/sim.2024.109.06,

Crous, P. W., Sandoval-Denis, M., Costa, M. M., Groenewald, J. Z., Van Iperen, A. L., Starink-Willemse, M., et al. (2022). Fusarium and allied fusarioid taxa (FUSA). 1. Fungal System. Evol. 9, 161–200. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2021.100116

Dissanayake, A. J., Zhu, J. T., Chen, Y. Y., Maharachchikumbura, S. S., Hyde, K. D., and Liu, J. K. (2024). A re-evaluation of Diaporthe: refining the boundaries of species and species complexes. Fungal Divers. 126, –125. doi: 10.1007/s13225-024-00538-7

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340,

Fujisawa, T., and Barraclough, T. G. (2013). Delimiting species using single-locus data and the generalized mixed yule coalescent approach: a revised method and evaluation on simulated data sets. Syst. Biol. 62, 707–724. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt033,

Gautier, C., Pinson-Gadais, L., and Richard-Forget, F. (2020). Fusarium mycotoxins enniatins: an updated review of their occurrence, the producing Fusarium species, and the abiotic determinants of their accumulation in crop harvests. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 4788–4798. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00411,

Hilário, S., Gonçalves, M. F., and Alves, A. (2021). Using genealogical concordance and coalescent-based species delimitation to assess species boundaries in the Diaporthe eres complex. J. Fungi. 7:507. doi: 10.3390/jof7070507,

Hof, H., and Schrecker, J. (2024). Fusarium spp.: infections and intoxications. GMS Infect. Dis. 12:Doc04. doi: 10.3205/id000089,

Hofstetter, V., Miadlikowska, J., Kauff, F., and Lutzoni, F. (2007). Phylogenetic comparison of protein-coding versus ribosomal RNA-coding sequence data: a case study of the Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota). Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 44, 412–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.10.016,

Jankowiak, R., Bilański, P., Zając, J., Jobczyk, A., and Taerum, S. J. (2023). The culturable leaf mycobiome of Viscum album subsp. austriacum. For. Pathol. 53:e12821. doi: 10.1111/efp.12821

Jankowiak, R., Stępniewska, H., Bilański, P., and Hausner, G. (2025). Fusarium species associated with naturally regenerated Fagus sylvatica seedlings affected by Phytophthora. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 171, 661–681. doi: 10.1007/s10658-024-02975-1

Kamil, D., Mishra, A. K., Das, A., and Nishmitha, K. (2025). “Genus Fusarium and Fusarium species complexes” in Biodiversity, bioengineering, and biotechnology of Fungi. ed. D. Kamil (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 209–225.

Kapli, P., Lutteropp, S., Zhang, J., Kobert, K., Pavlidis, P., Stamatakis, A., et al. (2017). Multi-rate Poisson tree processes for single-locus species delimitation under maximum likelihood and Markov chain Monte Carlo. Bioinformatics 33, 1630–1638. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx025,

Liu, F., Wang, M., Damm, U., Crous, P. W., and Cai, L. (2016). Species boundaries in plant pathogenic fungi: a Colletotrichum case study. BMC Evol. Biol. 16:81. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0649-5,

Liu, Y. J., Whelen, S., and Hall, B. D. (1999). Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092,

Lombard, L., Crous, P. W., Cobo-Diaz, J. F., Le Floch, G., and Nodet, P. (2021). Fungal planet description sheets: 1282-1283. Persoonia 46, 313–528. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2021.46.11,

Lombard, L., Van der Merwe, N. A., Groenewald, J. Z., and Crous, P. W. (2015). Generic concepts in Nectriaceae. Stud. Mycol. 80, 189–245. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.12.002,

Luo, A., Ling, C., Ho, S. Y., and Zhu, C. D. (2018). Comparison of methods for molecular species delimitation across a range of speciation scenarios. Syst. Biol. 67, 830–846. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy011,

Maharachchikumbura, S. S., Chen, Y., Ariyawansa, H. A., Hyde, K. D., Haelewaters, D., Perera, R. H., et al. (2021). Integrative approaches for species delimitation in Ascomycota. Fungal Divers. 109, 155–179. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.113.139427

Manganiello, G., Marra, R., Staropoli, A., Lombardi, N., Vinale, F., and Nicoletti, R. (2019). The shifting mycotoxin profiles of endophytic Fusarium strains: a case study. Agriculture 9:143. doi: 10.3390/agriculture9070143

Marin-Felix, Y., Hernández-Restrepo, M., Wingfield, M. J., Akulov, A., Carnegie, A. J., Cheewangkoon, R., et al. (2019). Genera of phytopathogenic fungi: GOPHY 2. Stud. Mycol. 92, 47–133. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.04.002,

Munkvold, G. P., Proctor, R. H., and Moretti, A. (2021). Mycotoxin production in Fusarium according to contemporary species concepts. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 59, 373–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-102825,

Nicoletti, R., and Zimowska, B. (2023). Endophytic fungi of hazelnut (Corylus avellana). Plant Prot. Sci. 59, 107–123. doi: 10.17221/133/2022-PPS

Nirenberg, H. I. (1976). Untersuchungen über die morpholoigische und biologische differnzierung in der Fusarium-sektion Liseola. Mitt. Biol. Bundesanst. Land- u. Forstwirtsch. Berl.-Dahlem 169, 1–117. doi: 10.5073/20210624-085725

O’Donnell, K., Gueidan, C., Sink, S., Johnston, P. R., Crous, P. W., Glenn, A., et al. (2009). A two-locus DNA sequence database for typing plant and human pathogens within the Fusarium oxysporum species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46, 936–948. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.08.006,

O’Donnell, K., Ward, T. J., Robert, V. A., Crous, P. W., Geiser, D. M., and Kang, S. (2015). DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: current status and future directions. Phytoparasitica 43, 583–595. doi: 10.1007/s12600-015-0484-z

O’Donnell, K., Whitaker, B. K., Laraba, I., Proctor, R. H., Brown, D. W., Broders, K., et al. (2022). DNA sequence-based identification of Fusarium: a work in progress. Plant Dis. 106, 1597–1609. doi: 10.1094/pdis-09-21-2035-sr,

O'Donnell, K., Kistler, H. C., Cigelnik, E., and Ploetz, R. C. (1998). Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 2044–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2044,

Okonechnikov, K., Golosova, O., and Fursov, M.UGENE team (2012). Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 28, 1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091

Puillandre, N., Lambert, A., Brouillet, S., and Achaz, G. J. M. (2012). ABGD, automatic barcode gap discovery for primary species delimitation. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1864–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2011.05239.x,

Pyszko, P., Šigutová, H., Kolařík, M., Kostovčík, M., Ševčík, J., Šigut, M., et al. (2024). Mycobiomes of two distinct clades of ambrosia gall midges (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) are species-specific in larvae but similar in nutritive mycelia. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e0283023–e0283023. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02830-23,

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G., and Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 67, 901–904. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032,

Salvatore, M. M., Andolfi, A., and Nicoletti, R. (2023). Mycotoxin contamination in hazelnut: current status, analytical strategies, and future prospects. Toxins 15:99. doi: 10.3390/toxins15020099,

Sandoval-Denis, M., Guarnaccia, V., Polizzi, G., and Crous, P. W. (2018). Symptomatic Citrus trees reveal a new pathogenic lineage in Fusarium and two new Neocosmospora species. Persoonia 40, 1–25. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2018.40.01,

Shang, Q. J., Phookamsak, R., Camporesi, E., Khan, S., Lumyong, S., and Hyde, K. D. (2018). The holomorph of Fusarium celtidicola sp. nov. from Celtis australis. Phytotaxa 361, 251–265. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.361.3.1,

Sklenář, F., Glässnerová, K., Jurjević, Ž., Houbraken, J., Samson, R. A., Visagie, C. M., et al. (2022). Taxonomy of aspergillus series Versicolores: species reduction and lessons learned about intraspecific variability. Stud. Mycol. 102, 53–93. doi: 10.3114/sim.2022.102.02,

Stamatakis, A. (2014). RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033,

Stępień, Ł. (2014). The use of Fusarium secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes in chemotypic and phylogenetic studies. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 40, 176–185. doi: 10.3109/1040841x.2013.770387,

Stoeva, D., Gencheva, D., Yordanova, R., and Beev, G. (2023). Molecular marker-based identification and genetic diversity evaluation of Fusarium spp. - а review. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 39, 376–385. doi: 10.59393/amb23390402

Summerell, B. A. (2019). Resolving Fusarium: current status of the genus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 323–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-100204,

Todorović, I., Moënne-Loccoz, Y., Raičević, V., Jovičić-Petrović, J., and Muller, D. (2023). Microbial diversity in soils suppressive to Fusarium diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1228749. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1228749,

Turco, S., Grottoli, A., Drais, M. I., De Spirito, C., Faino, L., Reverberi, M., et al. (2021). Draft genome sequence of a new Fusarium isolate belonging to Fusarium tricinctum species complex collected from hazelnut in Central Italy. Front. Plant Sci. 12:788584. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.788584,

Ulaszewski, B., Sandoval-Denis, M., Groenewald, J. Z., Costa, M. M., Mishra, B., Ploch, S., et al. (2025). Genomic features and evolution of lifestyles support the recognition of distinct genera among fusarioid fungi. Mycol. Progress 24:20. doi: 10.1007/s11557-024-02025-4

Vitale, S., Santori, A., Wajnberg, E., Castagnone-Sereno, P., Luongo, L., and Belisario, A. (2011). Morphological and molecular analysis of Fusarium lateritium, the cause of gray necrosis of hazelnut fruit in Italy. Phytopathology 101, 679–686. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-10-0120,

Vu, D., Groenewald, M., De Vries, M., Gehrmann, T., Stielow, B., Eberhardt, U., et al. (2019). Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 92, 135–154. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.05.001,

Xia, J. W., Sandoval-Denis, M., Crous, P. W., Zhang, X. G., and Lombard, L. (2019). Numbers to names-restyling the Fusarium incarnatum-equiseti species complex. Persoonia 43, 186–221. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.05,

Zapata, M., Rodríguez-Serrano, E., Castro, J. F., Santelices, C., Carrasco-Fernández, J., Damm, U., et al. (2024). Novel species and records of Colletotrichum associated with native woody plants in south-central Chile. Mycol. Progr. 23:18. doi: 10.1007/s11557-024-01956-2

Keywords: Fusarium citricola species complex, Fusarium tricinctum species complex, hazelnut mycobiome, phylogenesis, species delimitation analysis

Citation: Brugneti F, Turco S, Ukwibishaka N, Abramczyk B, Cardacino A, Mazzaglia A, Nicoletti R, De Masi L and Zimowska B (2026) Molecular investigation on hazelnut-associated Fusarium isolates belonging to the Fusarium citricola species complex. Front. Microbiol. 16:1741069. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1741069

Edited by:

Debasis Mitra, Graphic Era University, IndiaReviewed by:

Lukasz Stepien, Polish Academy of Sciences, PolandCaterina Morcia, Council for Agricultural and Economics Research, Italy

Copyright © 2026 Brugneti, Turco, Ukwibishaka, Abramczyk, Cardacino, Mazzaglia, Nicoletti, De Masi and Zimowska. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosario Nicoletti, cm9zYXJpby5uaWNvbGV0dGlAY3JlYS5nb3YuaXQ=

Federico Brugneti

Federico Brugneti Silvia Turco

Silvia Turco Nepomuscene Ukwibishaka1

Nepomuscene Ukwibishaka1 Antonella Cardacino

Antonella Cardacino Angelo Mazzaglia

Angelo Mazzaglia Rosario Nicoletti

Rosario Nicoletti Luigi De Masi

Luigi De Masi Beata Zimowska

Beata Zimowska