- 1Medical College, Henan University of Chinese Medicine, Zhengzhou, China

- 2Henan Engineering Research Center for Chinese Medicine Foods for Special Medical Purpose, Zhengzhou, China

Background: Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.) is an edible plant that has been found to have medicinal effects in the treatment of hyperuricemia (HUA). The bioactive compounds of mulberry leaf and their mechanisms of action have not been determined yet.

Methods: In-silico methodologies were used to identify bioactive compounds and to determine the underlying mechanisms of mulberry leaf. In order to verify the biochemical mechanism and intestinal microbiota, in vivo experiments were conducted.

Results: Kaempferol was identified as the principal bioactive compound, while the key targets were AKT1 and TNF. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations revealed that AKT1-kaempferol and TNF-kaempferol complexes showed strong and stable binding pattern after a 100 ns simulation. In vivo studies demonstrated that kaempferol exerted significant anti-HUA effects. Specifically, kaempferol reduces AKT expression and phosphorylation, which may in turn reduces the oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways and signal transmission of the kidneys. Meanwhile, the application of kaempferol attenuated gut microbiota dysbiosis caused by HUA.

Conclusion: Kaempferol may regulate UA metabolism and inflammatory injury by modulating the AKT signaling pathway, and exert its effects on the gut-kidney axis and restoring gut microbiota composition.

1 Introduction

Hyperuricemia (HUA) is a metabolic disorder primarily characterized by elevated serum uric acid (UA) levels, which is often accompanied by hyperreactive oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (Yang et al., 2019b; Wang et al., 2022). Current pharmacological treatments for HUA include xanthine oxidase inhibitors such as allopurinol and febuxostat, and uricosuric agents like benzbromarone. Despite their efficacy in reducing UA levels, the long-term use of these agents is often associated with significant adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, cardiovascular complications, and severe hypersensitivity reactions (Yokose et al., 2019), which substantially limit their clinical applicability. Therefore, the development of safer and longer-acting therapeutic strategies for HUA is urgently needed.

Traditional Chinese medicines (TCM) have a long-standing history of clinical use and have demonstrated beneficial effects in the treatment of various metabolic disorders, such as hypertension, diabetes, and atherosclerosis (Huang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022a). Mulberry leaf (Morus alba L.), a commonly used TCM food source in China, is consumed in various forms including tea infusions, stir-frying and deep-frying (Makchuay et al., 2023). Its bioactive compounds mainly include flavonoids, phenolic acids, coumarins, and polysaccharides (Shi et al., 2022). Recent studies have highlighted the potential of mulberry leaf in alleviating HUA. The ethyl acetate extract of mulberry leaf has been shown to regulate both UA production and excretion, leading to a significant reduction in serum UA levels (Yao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2025). Additionally, the polysaccharide fractions exhibit strong antioxidant activity by scavenging hydroxyl radicals and modulating inflammatory cytokine secretion, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory and oxidative stress-reducing effects (Hu et al., 2024). However, the precise bioactive compounds responsible for its anti-HUA effects and the associated molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

The deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) is widely recognized as a classic trigger of acute inflammatory responses and subsequent tissue injury. However, even with no MSU formation, persistently elevated soluble uric acid promotes subclinical inflammation and enhanced oxidative stress, resulting in progressive tissue damage (Yip et al., 2020). Multiple signaling pathways are involved in this process, such as AKT, NF-κB, and STAT signaling (Ge et al., 2024; Alanazi et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2026). In addition, gut-kidney axis also plays an important role in this process. Gut microbial dysbiosis is likely to disrupt short-chain fatty acid metabolism, intestinal barrier permeability, and endotoxin levels. These alternations finally lead to structural and functional renal injury (Yang et al., 2018; Tsuji et al., 2024; Deng et al., 2025). Zhang et al. reported that Lactobacillus paracasei N1115 exerted a beneficial effect on HUA by modulating butyrate production through a cross-feeding interaction (Zhang et al., 2025). Ni et al. demonstrated that combined administration of astaxanthin and Lactobacillus rhamnosus could alleviate HUA via gut-kidney axis (Ni et al., 2025).

This research applied network pharmacology to explore the potential biological activities of the identified bioactive compounds. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations (MDS) were utilized to construct binding models between compounds and target proteins. The findings indicated kaempferol as the primary bioactive compound contributing to the anti-HUA effect of mulberry leaf. Then a HUA mouse model was constructed to investigate the molecular mechanisms of kaempferol in vivo. Kaempferol exerted its therapeutic effect by reducing UA levels, modulating purine metabolism, and attenuating inflammatory responses, primarily through inhibition of AKT expression and phosphorylation. These findings offer conceptual support and novel insights into the therapeutic use of mulberry leaf for managing HUA.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents

Kaempferol (K812226) was purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Oxonic acid potassium salt (OA, 156124) and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC-Na, 419338) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Allopurinol (A105386) and hypoxanthine (HX, H108384) were supplied by Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Commercial assay kits for GSH, MDA, UA, CRE, and BUN were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). ELISA kits for mouse IL-1β (KT21178), IL-6 (KT99854), IL-17 (KT22800), and TNF-α (KT99985) were provided by Wuhan Moshake Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Antibodies against AKT (#4691) and phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT, #4060) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Phosphatase inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Beyotime (#P1082, Beyotime, China).

2.2 Screening of major bioactive compounds in mulberry leaf and HUA-related targets

All bioactive compounds present in mulberry leaf were retrieved from the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP, https://www.tcmsp-e.com). Compounds with oral bioavailability (OB) >30% and drug-likeness (DL) >0.18 were selected as the main bioactive compounds. The potential targets of these compounds were then predicted using the SwissTargetPrediction online platform, and those with a predicted possibility >0.1 were retained as candidate targets (Daina et al., 2019). To identify HUA-related targets, the term “hyperuricemia” was searched in the GeneCards database, yielding a total of 1,410 associated targets. Among these, 706 targets with relevance scores above the median were selected for further analysis (Stelzer et al., 2016). Additionally, 287 targets with an inference score greater than 30 were obtained from the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, http://ctdbase.org/) (Davis et al., 2024). The overlapping targets from both databases were merged.

2.3 Identification of core targets of mulberry leaf against HUA

Based on the targets identified above, common targets between mulberry leaf bioactive compounds and HUA-related genes were determined. The intersecting targets were then imported into the STRING database to construct a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, with the minimum required interaction score set to 0.4. Topological analysis of the PPI network was performed to calculate key parameters, including degree, betweenness, and closeness centralities of each node (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). Targets with all 3 topological parameters exceeding the average were identified as core targets (Supplementary Table 1).

2.4 Enrichment analysis

Based on the identified core targets, enrichment analyses for Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were conducted via the DAVID database (Sherman et al., 2022). The parameters set as “identifier = official gene symbol” and “species = Homo sapiens.” The top 10 terms in both GO and KEGG analyses were selected based on p-values for further interpretation.

2.5 Compound-target-pathway (C-T-P) network

To further explore the mechanism by which mulberry leaf exerts anti-HUA effects, the previously identified bioactive compounds, core targets, and the top 10 enriched pathways were imported into Cytoscape 3.10.3 software to construct a C-T-P network. Topological analysis of the network was conducted to calculate key metrics for each node (Supplementary Table 2).

2.6 Molecular docking

The 3D structures of the main compounds were retrieved from the PubChem database (Kim et al., 2023), while structures of the core target proteins were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (Burley et al., 2023). Molecular docking between the bioactive compounds and core targets were performed using AutoDock Tools 4.0. A binding free energy of less than −7.0 kcal/mol was considered indicative of strong binding affinity (Morris et al., 2009). PyMOL software was used for visualizing ligand binding sites and interaction modes. The binding sites and docking boxes were shown in Supplementary Table 3.

2.7 Molecular dynamics simulations

The optimal docking complexes generated from molecular docking studies were subjected to MDS using GROMACS 2022.3 software (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). The Amber99sb-ildn force field and tip3p water model were employed to parameterize the receptor proteins. A cubic simulation box was constructed around the receptor, and sufficient Na+ ions were added to neutralize the overall charge of the system. Energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm to relax all atoms in the protein structure. Equilibration was carried out in two phases: an isothermal-isochoric ensemble followed by an isothermal-isobaric ensemble, each run for 100,000 steps with a coupling constant of 0.1 picosecond (ps) and a total duration of 100 ps. Subsequently, a production MDS was conducted for 5,000,000 steps with a time step of 2 femtosecond (fs), corresponding to a total simulation time of 100 nanosecond (ns). Upon completion, the trajectory data were analyzed using built-in GROMACS tools.

2.8 In vivo experimental design

Male Kunming mice (5 weeks old, 18-22 g) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (License No.: SCXK [Zhe] 2020-0002). All animals were housed in a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) environment under controlled conditions: temperature 23-25 °C, relative humidity 40-60%, and a 12 h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water. The animal protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Henan University of Chinese Medicine (Approval No.: IACUC-202503027). After a week of acclimatization, 36 mice were randomly divided into 6 groups (n = 6 per group): control group (Con), model group (Mod), allopurinol group (All, 10 mg/kg), and 3 kaempferol treatment groups: low-dose (Low, 25 mg/kg), medium-dose (Mid, 50 mg/kg), and high-dose (High, 100 mg/kg) (Qu et al., 2021). Beginning on day 8, mice in the Mod and kaempferol treatment groups were intraperitoneally injected with OA at 300 mg/kg/day (dissolved in 0.5% CMC-Na), followed 1 h later by oral administration of HX at 500 mg/kg/day, dissolved in normal saline (NS), for 14 consecutive days to induce HUA. While mice in the control group received equivalent volumes of CMC-Na or NS in the same way. Starting on day 15, all groups received their respective interventions 1 h after HX administration, once daily for 4 weeks: vehicle for the Con and Mod groups, allopurinol (10 mg/kg) for the All group, and kaempferol at different doses for the treatment groups. At the end of the treatment period, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation. Blood samples were collected, allowed to stand at room temperature for 40 mins, and centrifuged to obtain serum, which was stored at −70 °C for subsequent analysis. The kidneys were also harvested: the left kidney was washed thoroughly and stored at −70 °C, while the right kidney was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological examination. The animal experiment design is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.9 Biochemical index measurements

Serum levels of UA, CRE, and BUN were measured using commercial biochemical assay kits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to quantify the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17. All ELISA measurements were performed in duplicate, with an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) < 10%. Oxidative stress in renal tissue was assessed by measuring the levels of GSH and MDA in kidney homogenates using commercial biochemical assay kits.

2.10 Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Mouse right kidney tissues were adequately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Tissue blocks were sectioned into 3 μm slices, followed by H&E staining to examine histopathological changes in the kidneys across different groups.

2.11 Western blotting (WB)

Mouse kidney tissues were lysed on ice using RIPA buffer containing PMSF and phosphatase inhibitors to extract total protein. Proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and visualized using a Bio-Rad imaging system. ImageJ software was employed to analyze band intensity, with β-actin used as the internal loading control. The expression levels of AKT and p-AKT were quantified via WB.

2.12 16S rRNA sequencing analysis

Total DNA was extracted from the fecal microbiota 16S rRNA gene. The V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene was sequenced. Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) accession and abundance were used for subsequent data analyses. PICRUSt2 was utilized to predict metabolic pathways and cluster of orthologous group (COG) functional categories of the microbiota.

2.13 Correlation analysis

To identify potential key microbial taxa, we performed correlation analyses between dominant differential microbes and the altered key indicators. Pearson correlation coefficients were applied to assess the value of association between microbiota taxa and clinical variables.

2.14 Statistical analysis

All experimental data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM, Chicago, USA). One-way analysis of variance was applied for intergroup comparisons, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Screening of bioactive compounds in mulberry leaf and their associated targets against HUA

A total of 269 chemical compounds of mulberry leaf were retrieved from the TCMSP database. The SMILES structures of these compounds were submitted to the SwissTargetPrediction web server to predict their potential targets. The resulting targets were then cross-referenced with the UniProt database to standardize protein names. A total of 513 unique targets related to the bioactive compounds were identified. Meanwhile, HUA-related disease targets were obtained, resulting in 913 non-redundant targets. A Venn diagram analysis revealed 104 overlapping targets between the compound-related targets and HUA-related disease targets, indicating potential anti-HUA relevance (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Network pharmacology analysis of mulberry leaf against HUA. (A) Overlapping targets between mulberry leaf and HUA; (B) PPI network of the overlapping targets; (C) GO enrichment and (D) KEGG pathway analysis of the 24 core targets; (E) C-T-P network diagram (blue polygons: bioactive compounds; green circles: core targets; orange triangles: signaling pathways).

3.2 Construction of the PPI network

A PPI network was constructed based on the 104 intersecting targets, and after removing the disconnected nodes, the resulting PPI network was constructed, consisting of 102 nodes and 1,176 edges (Figure 1B). The average degree, betweenness, and closeness centrality values of the intersecting targets were 23.06, 94.76, and 0.53, respectively, and 24 targets were identified as core targets. Among them, AKT1, TNF, TP53, BCL2, CASP3, and PPARG degree value exceeded 60, suggesting that these targets may serve as more critical molecular targets of mulberry leaf in the treatment of HUA.

3.3 Enrichment analysis of core targets

To further investigate the biological functions of the core targets, GO and KEGG analyses were conducted using the DAVID database (Figures 1C, D). GO enrichment results revealed that the core targets were involved in a wide range of BP, CC, and MF. Using a significance threshold of p < 0.05, 173 BP terms were identified. The top 3 was: response to xenobiotic stimulus, positive regulation of neuron apoptotic process, and positive regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. A total of 22 CC terms were enriched, with the top 3 being protein-containing complex, cytoplasm, and cytosol. For MF, 65 terms were identified, mainly associated with enzyme binding, identical protein binding, and nuclear receptor activity. These findings suggest that the anti-HUA effects of mulberry leaf may be closely related to the regulation of enzyme activity and resistance to oxidative stress. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that 81 signaling pathways were significantly enriched. The top 10 enriched pathways were visualized and primarily involved: colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, endocrine resistance, proteoglycans in cancer, pathways in cancer, lipid and atherosclerosis, human cytomegalovirus infection, gastric cancer, hepatitis C, and microRNAs in cancer.

3.4 C-T-P network analysis

Using Cytoscape software, a network was constructed, consisting of 25 bioactive compounds from mulberry leaf, 24 core targets, and the top 10 enriched signaling pathways. A total of 5 compounds that were not connected to any core targets were excluded, resulting in a finalized C-T-P network (Figure 1E). The resulting network contained 54 nodes and 194 edges. Topological parameter analysis revealed an average degree of 7.19, average betweenness centrality of 80.78, and average closeness centrality of 0.40. Based on degree ranking, the 5 most important bioactive compounds were identified as kaempferol, norartocarpetin, arachidonic acid, 4-prenylresveratrol, and quercetin.

3.5 Molecular docking analysis

To validate the interactions between the key bioactive compounds and core targets, molecular docking was performed to assess binding affinities. The top 5 bioactive compounds were selected as ligands, while 6 most critical molecular targets served as receptor proteins. As shown in Figure 2A, among all docking models, AKT-kaempferol and TNF-kaempferol demonstrated the strongest binding affinities. Visualization of target-compound interactions and binding modes was performed using PyMOL (Figures 2B-D). The results revealed that kaempferol formed hydrogen bonds with key amino acid residues of AKT (VAL-271, ASP-292, and TYR-326) and TNF (LYS-98, GLN-102, and GLU-116). These findings confirm that the bioactive compounds in mulberry leaf exhibit strong binding potential with critical HUA-related targets.

Figure 2. Molecular docking and MDS analysis. (A) Binding energies of the 3 bioactive compounds with the core targets; (B) AKT1, (C) TNF and (D) PPARG form hydrogen bonds with residues of core targets, respectively. (E) RMSD, RMSF, and Rg analysis of AKT1-kaempferol and (F) TNF-kaempferol.

3.6 Molecular dynamics simulations analysis

To further evaluate the stability of interactions between kaempferol and the two key targets, AKT and TNF, 100 ns MDS were conducted for the 2 best docking complexes: AKT-kaempferol and TNF-kaempferol (Figures 2E, F). The RMSD curves showed the overall stability and conformational fluctuations of both complexes. In comparison to the protein-solvent systems alone, all systems exhibited initial fluctuations during the first 20 ns, after which they stabilized, indicating the systems reached equilibrium under the simulation conditions. The total complexes (black curves) showed greater fluctuations than the corresponding apo-proteins (red curves), likely due to conformational changes induced by ligand binding. This suggests that kaempferol binding affects the structural stability of AKT and TNF, although both systems eventually achieved a relatively stable conformation after 20 ns. The RMSF plots reflected the flexibility of amino acid residues within the complexes. Peaks near residues 120 and 310 indicated regions of higher flexibility, possibly corresponding to loops or substrate-binding regions near the active site. Increased flexibility in these areas may enhance ligand interaction and facilitate functional adaptability of the protein. In contrast, lower RMSF values in other regions suggest that much of the complex remains structurally stable, preserving the enzyme's core conformation. The Rg plots were used to assess the compactness of the AKT1-kaempferol and TNF-kaempferol complexes. The consistently stable Rg values observed during the simulation suggested that the tertiary structures of the complexes remained largely unchanged, with no marked expansion or contraction, thereby reinforcing the structural stability of the target-compound complexes.

3.7 Kaempferol alleviates HUA in mice

HUA mouse model was employed to explore the mechanism of kaempferol in managing HUA. In the High group, serum UA levels were reduced by 37.81% (p < 0.001), indicating that kaempferol exerts potent anti-HUA activity in mice (Figure 3A). Additionally, CRE and BUN levels were significantly reduced by 33.49% and 59.25%, respectively, in the High group (p < 0.001), suggesting a potential reno-protective effect of kaempferol (Figures 3B, C). Subsequently, oxidative stress markers and inflammatory cytokines were assessed in kidney tissues. High dose kaempferol treatment significantly increased the level of the antioxidant GSH by 56.62% (p < 0.001) and reduced the level of MDA by 20.05% (p < 0.001), indicating enhanced renal antioxidant capacity and reduced oxidative stress (Figures 3D, E). As for inflammatory cytokines, the most notable was IL-17 (Figure 3H), which decreased by 51.50% in the Mid group and 65.25% in the High group (p < 0.001). Additionally, other cytokines also showed varying degrees of reduction: IL-1β (Figure 3F) decreased by 15.68%, IL-6 (Figure 3G) by 28.72%, and TNF-α (Figure 3I) by 42.79% (p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Effects of kaempferol against HUA. (A) Serum UA levels after treatment; (B, C) Serum renal function indicators: CRE and BUN; (D, E) Oxidative stress markers in kidney tissue: GSH and MDA; (F-I) Levels of inflammatory cytokines in serum. Each dot represents the measurement from an individual mouse (n = 6 per group), and bars indicate the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. Mod group; ###p < 0.001 vs. Con group.

3.8 Histopathological effects of kaempferol on kidney tissue in mice

As shown in Figure 4A, H&E staining revealed significant renal damage in HUA model mice induced by combined administration of OA and HX. Pathological features included varying degrees of tubular epithelial cell swelling and degeneration, mild tubular dilation, mesangial cell proliferation, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Notably, these pathological alterations were markedly alleviated in the high-dose kaempferol treatment group, suggesting a protective effect of kaempferol against UA-induced renal injury.

Figure 4. Kaempferol ameliorates renal injury and inhibits the AKT Pathway. (A) Representative H&E-stained kidney sections from each group after treatment (bar = 50 μm); (B) WB images of total AKT and p-AKT; (C, D) quantification of the relative expression levels of total AKT and p-AKT based on grayscale analysis of the blotting results. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. Mod group.

3.9 Effects of kaempferol on core targets

Based on the above results, AKT was identified as the major potential target through which kaempferol exerts its therapeutic effects. To validate this, the expression levels of AKT and p-AKT in renal tissue were evaluated by WB (Figure 4B). The results revealed that total AKT protein levels remained unchanged in model mice, whereas p-AKT expression was significantly increased, and the p-AKT/AKT ratio increased by 129.47% compared with the control group. Then, in kaempferol treated mice, decreases were observed in both AKT and p-AKT expression. And a 41.51% decrease of p-AKT/AKT ratio was observed in the High group compared with the model group, indicating that kaempferol effectively inhibits AKT expression and phosphorylation in HUA mice (Figures 4C, D).

3.10 Kaempferol attenuated gut microbiota of HUA mice

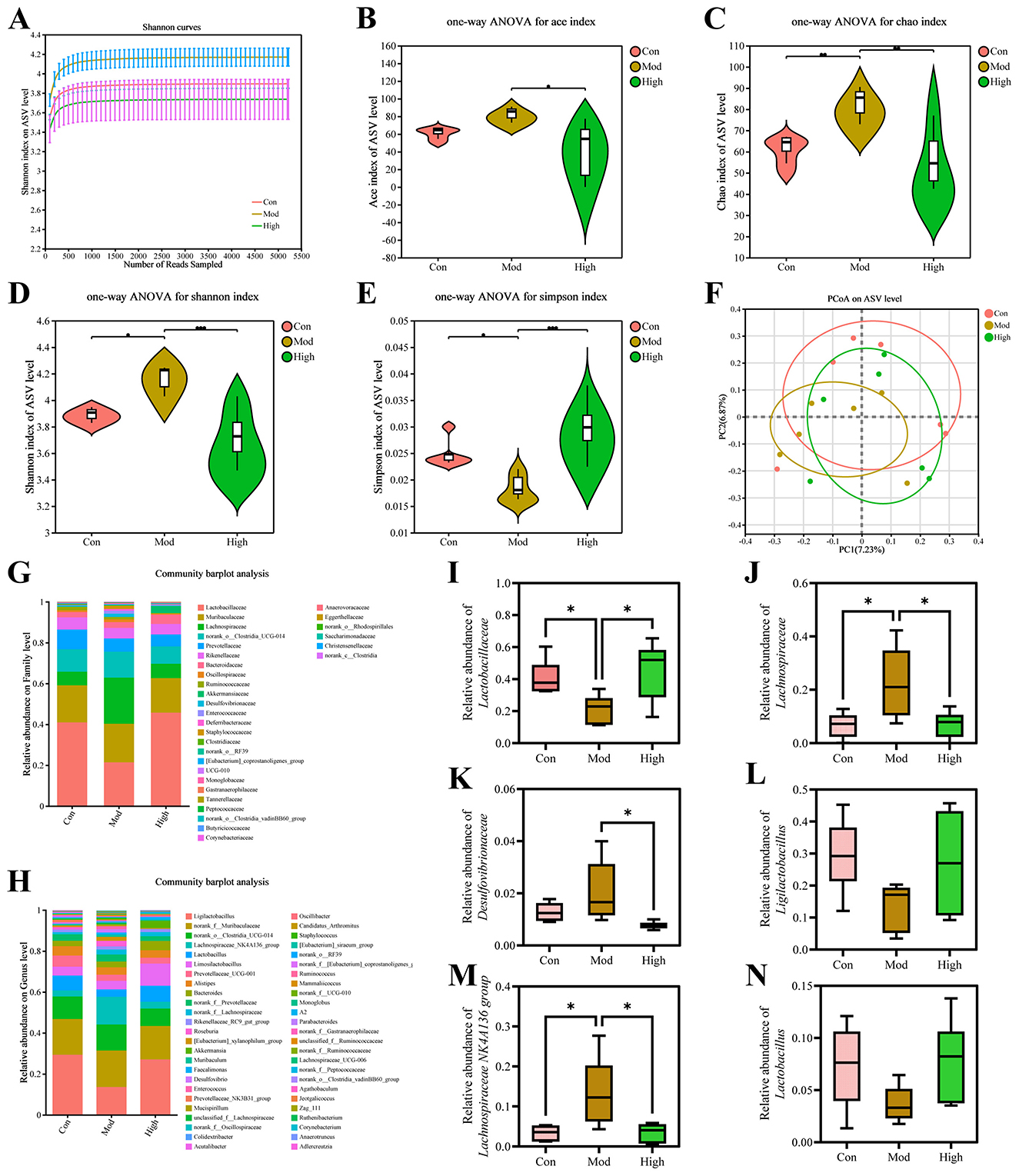

As the high-dose group showed superior outcomes in biochemical indices and histopathological analysis compared with the other treatment groups, it was chosen for subsequent investigations. To characterize the effects of kaempferol on the gut microbiota of HUA mice, fecal samples were prepared to 16S rRNA sequencing following the aforementioned procedure. The Shannon index gradually increased and then reached a plateau, indicating the results had sufficient representativeness (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Kaempferol modulate gut microbiota diversity and composition on ASV level. (A) Shannon rarefaction curves. (B-E) Violin plots of ACE index, Chao1 index, Shannon index, and Simpson index. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. (F) PCoA β-diversity analysis. (G, H) Community barplot analysis at family and genus levels. (I-K) Relative abundance of representative microbiomes at family level. (L-N) Relative abundance of representative microbiomes at genus level. Data are presented as mean ± SD. p < 0.05 indicates statistically significant differences between groups. *p < 0.05.

As shown in Figures 5B-E, the α-diversity index in Mod group significantly changed, and kaempferol treatment modulated these indices toward Con group profile. PCoA analysis revealed that the gut microbiota structure in the Mod group changes compared with the Con group, while it shifted toward Con group after treatment with kaempferol, suggesting that kaempferol exerted a restorative effect on gut microbial composition (Figure 5F).

At the family level, kaempferol treatment reversed the abundance alterations of Lactobacillaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Desulfovibrionaceae caused by HUA (Figures 5G, I-K). In this study, both of Lachnospiraceae and Desulfovibrionaceae showed a significant increase in the Mod group, which was alleviated by kaempferol treatment. Similarly, at the genus level, kaempferol also showed a clear regulatory trend on the abundances of several genus (Figures 5H, L-N). HUA induced microbiota dysbiosis in mice, and kaempferol altered these changes at family and genus levels.

3.11 Correlation analysis and functional prediction of differential microbiota

To explore the relationship between gut microbiota alterations and the progression of HUA, we performed a correlation analysis between microbiota composition and HUA-related cytokines. LEfSe analysis was used to identify the differences in gut microbiota among the fecal samples of mice from different groups (Figure 6A). In the Mod group, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Colidextribacter, and Roseburia were identified as the dominant genus. In contrast, after kaempferol treatment, Lactobacillaceae and Akkermansiaceae exhibited higher relative abundances compared to the Mod group. Pearson's correlation analysis revealed that Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Colidextribacter, and Roseburia were positively correlated with the progression of HUA, whereas Lactobacillaceae and Akkermansiaceae showed a negative correlation (Figure 6B). UA and IL-1β were negatively correlated with Lactobacillaceae, but positively correlated with Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group. IL-17 showed a significant negative correlation with Lactobacillaceae, while exhibiting significant positive correlations with Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Colidextribacter, and Roseburia. GSH levels were significantly negatively correlated with Colidextribacter and Roseburia, but positively correlated with Lactobacillaceae and Akkermansiaceae. Moreover, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group displayed significant positive correlations with several cytokines, including CRE, BUN, IL-6, TNF-α, and MDA.

Figure 6. Differential analysis and functional correlation of gut microbiota. (A) LEfSe analysis (LDA > 2). (B) Spearman correlation heatmap between significantly altered microbiomes and biochemical indicators (GSH, IL-17, IL-1β, UA, BUN, MDA, IL-6, CRE, and TNF). (C) COG functional categories analysis. (D) KEGG functional pathway analysis. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Subsequently, functional prediction was performed using PICRUSt2. Based on the COG classification system, differences in microbial functions were analyzed (Figure 6C). The Mod group showed a significant decrease in the J category, compared with the Con group. Kaempferol treatment significantly attenuated the alteration. KEGG pathway enrichment indicated the microbiota in Mod group significantly altered in genetic information processing and cellular processes, and kaempferol treatment counteract these alterations (Figure 6D).

4 Discussions

Elevated serum UA levels, along with increased oxidative stress and dysregulated inflammatory cytokines, are key pathological features of HUA. Mulberry leaf, rich in flavonoids and polyphenolic compounds, has potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and metabolic regulatory properties, including modulation of blood glucose and lipid levels (Shan et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2022). In addition, mulberry leaf has been shown to lower serum UA in HUA model mice, potentially through inhibition of xanthine oxidase activity, suggesting great therapeutic potential in the prevention and treatment of HUA (Wang et al., 2025). This study integrated network pharmacology, molecular docking, and MDS to investigate the major anti-HUA compounds of mulberry leaf and the potential mechanisms. Kaempferol is probably a principal active compound which is responsible for the anti-HUA effects of mulberry leaf. AKT1 and TNF were identified as its core molecular targets.

Kaempferol is a naturally occurring flavonoid widely distributed in various plants, fruits, and vegetables. It is distinguished by its antitumor, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties (Šelo et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022b). Numerous studies have demonstrated that kaempferol exhibits safety at biologically relevant doses, which make it a promising candidate as a natural therapeutic agent (Mamouni et al., 2018; Crocetto et al., 2021). Recent findings have shown that kaempferol can effectively ameliorate HUA by enhancing UA excretion through the regulation of key urate transporters, including ABCG2, OCT2, OAT1, and GLUT9 (Huang et al., 2024). Also, kaempferol derivatives, such as kaempferol3′-sulfonate and kaempferol-34′-di-O-β-glucoside, have been demonstrated in vitro inhibitory activity against xanthine oxidase (Teixeira et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023a). These findings further underscore the therapeutic potential of kaempferol and its derivatives in the treatment of HUA.

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is critically involved in the pathogenesis and advancement of HUA (Wan et al., 2025). AKT is known to catalyze the phosphorylation of URAT1 at the Thr408 site, a modification that promotes glycosylation and enhances the membrane localization of URAT1. This, in turn, increases URAT1 activity and facilitates renal reabsorption of UA (Fujii et al., 2025). Moreover, NF-κB is closely linked to AKT signaling (Grandage et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2019a; Chang et al., 2021). Earlier research has demonstrated that isorhamnetin can inhibit the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway and thereby alleviate UA-induced renal inflammation in mice (Kong et al., 2025). Similarly, corn silk flavonoids have been reported to attenuate HUA by downregulating this pathway, thereby reducing inflammation and apoptosis (Wang et al., 2023b). Taken together, the inhibition of AKT signaling can modulate renal UA transport, oxidative stress, and inflammation, ultimately contributing to HUA mitigation. TNF-α is a key proinflammatory cytokine that activates the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. It can also initiate apoptosis via the TNFR1 death domain, a mechanism implicated in tissue damage during HUA progression (Qin et al., 2012). In this study, the phosphorylation of AKT increased in the kidneys of HUA mice. Kaempferol treatment significantly suppressed the expression and phosphorylation of AKT proteins, corroborating the computational predictions and supporting its role in targeting these critical pathways in the context of HUA. However, due to the low initial expression of TNF, we did not detect sufficient expression of TNF in mouse kidney tissues by WB experiment. Instead, a significant decrease in TNF-α after kaempferol administration were observed in ELISA assay.

As one of the most common probiotic families, Lactobacillaceae protect the intestinal barrier and modulate inflammatory responses (Walter and O'Toole, 2023). Kaempferol treatment effectively alleviated the dysbiosis of Lactobacillaceae observed in the Mod group. Similarly, another up-regulated family is Lachnospiraceae. Certain strains of Lachnospiraceae exhibit potential toxicity and may be associated with chronic inflammation (Vacca et al., 2020). Previous studies have reported a significant increase in Lachnospiraceae abundance in chronic kidney disease (CKD) (Ren et al., 2023). In this research, the accumulation of kaempferol reversed the alternation in the composition of Lachnospiraceae. The excessive proliferation of Desulfovibrionaceae indicates the occurrence of inflammatory responses and the disruption of intestinal homeostasis (Jin et al., 2025). Previous studies have shown that Akkermansiaceae exhibited a decreased abundance in HUA mouse and was negatively correlated with intestinal permeability (Lv et al., 2023). Similarly, Yin et al. also reported an elevated abundance of Akkermansiaceae during the treatment of hyperuricemia with fermented Artemisia selengensis Turcz extracts. In this study, Akkermansiaceae showed a positive correlation with GSH, suggesting that this bacterial family may help restore oxidative stress homeostasis in the host.

In conclusion, this study indicated kaempferol might be an important compound for mulberry leaf in managing HUA. Mechanistically, kaempferol reduced AKT expression and phosphorylation and lowered TNF-α expression, which is potentially linked to the attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammatory responses in renal tissues. Moreover, kaempferol remodeled gut microbiota, and restored microbiota homeostasis.

Data availability statement

All data of this article are included within the article. It can also be requested from the corresponding author or first author. The sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1393186 (BioProject). The dataset includes 18 BioSamples and their corresponding SRA accessions, which can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1393186.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Henan University of Chinese Medicine. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JH: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. QW: Validation, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Conceptualization. XG: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. YN: Investigation, Writing – original draft. JH: Writing – original draft, Supervision. BZ: Writing – original draft, Resources. ZG: Writing – original draft, Data curation. ZW: Writing – original draft, Visualization. SF: Validation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Special Project of Henan Province, grant number 241111311200; the Joint Funds of Science and Technology Research and Development Project of Henan Province, grant number 232301420070; the Key Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province, grant number 24A310006; the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province, grant number 242300420498; the Scientific and Technological Attack Project of Henan Province, grant number 252102311277.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2026.1752775/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

HUA, hyperuricemia; UA, uric acid; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; MDS, molecular dynamics simulations; MSU, monosodium urate; OA, Oxonic acid potassium salt; HX, hypoxanthine; TCMSP, Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database; OB, oral bioavailability; DL, drug-likeness; CTD, Comparative Toxicogenomics Database; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; C-T-P, compound-target-pathway; PDB, Protein Data Bank; SPF, specific-pathogen-free; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; WB, western blotting; ASV, amplicon sequence variant; COG, cluster of orthologous group; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

References

Alanazi, S. T., Salama, S. A., Althobaiti, M. M., Bakhsh, A., Aljehani, N. M., Alanazi, E., et al. (2025). Theaflavin alleviates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: targeting SIRT1/p53/FOXO3a/Nrf2 signaling and the NF-kB inflammatory cascade. Food Chem. Toxicol. 198:115334. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2025.115334

Burley, S. K., Bhikadiya, C., Bi, C., Bittrich, S., Chao, H., Chen, L., et al. (2023). RCSB protein data bank (RCSB.org): delivery of experimentally-determined PDB structures alongside one million computed structure models of proteins from artificial intelligence/machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D488–D508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1077

Chang, M., Zhu, D., Chen, Y., Zhang, W., Liu, X., Li, X.-L., et al. (2021). Total flavonoids of litchi seed attenuate prostate cancer progression via inhibiting AKT/mTOR and NF-kB signaling pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 12:758219. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.758219

Chen, C., Yang, M.-Y., Lin, F.-Y., Chen, J.-W., and Chang, T.-T. (2026). Sodium nitroprusside improves ischemia-induced neovascularization via the HO-1/NOX and AKT/eNOS signaling pathways in chronic kidney disease. Life Sci. 385:124143. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2025.124143

Crocetto, F., di Zazzo, E., Buonerba, C., Aveta, A., Pandolfo, S. D., Barone, B., et al. (2021). Kaempferol, myricetin and fisetin in prostate and bladder cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Nutrients 13:nu13113750. doi: 10.3390/nu13113750

Daina, A., Michielin, O., and Zoete, V. (2019). Swisstargetprediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W357–W364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382

Davis, A. P., Wiegers, T. C., Sciaky, D., Barkalow, F., Strong, M., Wyatt, B., et al. (2024). Comparative toxicogenomics database's 20th anniversary: Update 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D1328-D1334. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae883

Deng, W., Guo, Y., Mo, Q., Liu, J., Su, Y., Wei, Z., et al. (2025). Exploring the mechanisms of torularhodin in alleviating diabetic kidney disease: a microbiome and metabolomics approach through the gut-kidney axis. Food Res. Int. 221:117597. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2025.117597

Fujii, W., Yamazaki, O., Hirohama, D., Kaseda, K., Kuribayashi-Okuma, E., Tsuji, M., et al. (2025). Gene-environment interaction modifies the association between hyperinsulinemia and serum urate levels through SLC22A12. J. Clin. Invest. 135:e186633. doi: 10.1172/JCI186633

Ge, P., Xie, H., Guo, Y., Jin, H., Chen, L., Chen, Z., et al. (2024). Linoleyl acetate and mandenol alleviate HUA-induced ED via NLRP3 inflammasome and JAK2/STAT3 signalling conduction in rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28:e70075. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.70075

Grandage, V. L., Gale, R. E., Linch, D. C., and Khwaja, A. (2005). PI3-kinase/akt is constitutively active in primary acute myeloid leukaemia cells and regulates survival and chemoresistance via NF-kB, MAPkinase and p53 pathways. Leukemia 19, 586–594. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403653

Hu, Y., Zhang, Y., Cui, X., Wang, D., Hu, Y., and Wang, C. (2024). Structure-function relationship and biological activity of polysaccharides from mulberry leaves: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 268:131701. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131701

Huang, R., Zhang, M., Tong, Y., Teng, Y., Li, H., and Wu, W. (2022). Studies on bioactive components of red ginseng by UHPLC-MS and its effect on lipid metabolism of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Nutr. 9:865070. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.865070

Huang, Y., Li, C., Xu, W., Li, F., Hua, Y., Xu, C., et al. (2024). Kaempferol attenuates hyperuricemia combined with gouty arthritis via urate transporters and NLRP3/NF-κB pathway modulation. iScience 27:111186. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.111186

Jin, X., Su, J., Su, X., Dong, Y., Zhu, J., Zhou, H., et al. (2025). Study on the unique effects of wubi shanyao pills in improving postmenopausal osteoporosis via the “gut-bone” axis. Phytomedicine 148:157447. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.157447

Kim, S., Chen, J., Cheng, T., Gindulyte, A., He, J., He, S., et al. (2023). PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1373–D1380. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac956

Kong, X., Zhao, L., Huang, H., Kang, Q., Lu, J., and Zhu, J. (2025). Isorhamnetin ameliorates hyperuricemia by regulating uric acid metabolism and alleviates renal inflammation through the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Funct. 16, 2840–2856. doi: 10.1039/D4FO04867A

Lv, Q., Zhou, J., Wang, C., Yang, X., Han, Y., Zhou, Q., et al. (2023). A dynamics association study of gut barrier and microbiota in hyperuricemia. Front. Microbiol. 14:1287468. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1287468

Makchuay, T., Tongchitpakdee, S., and Ratanasumawong, S. (2023). Effect of mulberry leaf tea on texture, microstructure, starch retrogradation, and antioxidant capacity of rice noodles. J. Food Process Preserv. 2023, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2023/2964013

Mamouni, K., Zhang, S., Li, X., Chen, Y., Yang, Y., Kim, J., et al. (2018). A novel flavonoid composition targets androgen receptor signaling and inhibits prostate cancer growth in preclinical models. Neoplasia 20, 789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2018.06.003

Morris, G. M., Huey, R., Lindstrom, W., Sanner, M. F., Belew, R. K., Goodsell, D. S., et al. (2009). AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256

Ni, S., Zheng, W., Hu, Y., Li, S., Song, S., and Ai, C. (2025). Fabrication and characterization of astaxanthin-loaded nanoprobiotic and its role in alleviating hyperuricemia via the regulation of the gut-kidney axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 330:148077. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.148077

Qin, J., Shang, L., Ping, A., Li, J., Li, X., Yu, H., et al. (2012). TNF/TNFR signal transduction pathway-mediated anti-apoptosis and anti-inflammatory effects of sodium ferulate on IL-1β-induced rat osteoarthritis chondrocytes in vitro. Arthritis Res. Ther. 14:R242. doi: 10.1186/ar4085

Qu, Y., Li, X., Xu, F., Zhao, S., Wu, X., Wang, Y., et al. (2021). Kaempferol alleviates murine experimental colitis by restoring gut microbiota and inhibiting the LPS-TLR4-NF-κB axis. Front. Immunol. 12:679897. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.679897

Ren, F., Jin, Q., Jin, Q., Qian, Y., Ren, X., Liu, T., et al. (2023). Genetic evidence supporting the causal role of gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease and chronic systemic inflammation in CKD: a bilateral two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front. Immunol. 14:1287698. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1287698

Šelo, G., Planinić, M., Tišma, M., Grgić, J., Perković, G., Koceva Komlenić, D., et al. (2022). A comparative study of the influence of various fungal-based pretreatments of grape pomace on phenolic compounds recovery. Foods 11:11111665. doi: 10.3390/foods11111665

Shan, Y., Sun, C., Li, J., Shao, X., Wu, J., Zhang, M., et al. (2022). Characterization of purified mulberry leaf glycoprotein and its immunoregulatory effect on cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Foods 11:foods11142034. doi: 10.3390/foods11142034

Sherman, B. T., Hao, M., Qiu, J., Jiao, X., Baseler, M. W., Lane, H. C., et al. (2022). DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W216–W221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac194

Shi, Y., Zhong, L., Fan, Y., Zhang, J., Zhong, H., Liu, X., et al. (2022). The protective effect of mulberry leaf flavonoids on high-carbohydrate-induced liver oxidative stress, inflammatory response and intestinal microbiota disturbance in monopterus albus. Antioxidants 11:antiox11050976. doi: 10.3390/antiox11050976

Stelzer, G., Rosen, N., Plaschkes, I., Zimmerman, S., Twik, M., Fishilevich, S., et al. (2016). The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 54, 1.30.1-1.30.33. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5

Szklarczyk, D., Kirsch, R., Koutrouli, M., Nastou, K., Mehryary, F., Hachilif, R., et al. (2023). The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638–D646. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1000

Teixeira, A. F., de Souza, J., Dophine, D. D., de Souza Filho, J. D., and Saúde-Guimarães, D. A. (2022). Chemical analysis of eruca sativa ethanolic extract and its effects on hyperuricaemia. Molecules 27:molecules27051506. doi: 10.3390/molecules27051506

Tsuji, K., Uchida, N., Nakanoh, H., Fukushima, K., Haraguchi, S., Kitamura, S., et al. (2024). The gut–kidney axis in chronic kidney diseases. Diagnostics 15:21. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15010021

Vacca, M., Celano, G., Calabrese, F. M., Portincasa, P., Gobbetti, M., and De Angelis, M. (2020). The controversial role of human gut lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms 8:573. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8040573

Van Der Spoel, D., Lindahl, E., Hess, B., Groenhof, G., Mark, A. E., and Berendsen, H. J. C. (2005). GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291

Walter, J., and O'Toole, P. W. (2023). Microbe profile: the Lactobacillaceae. Microbiology 169:001414. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001414

Wan, Y., Yuan, M.-H., Liang, X., Wang, Y.-L., Ye, Q., Peng, C., et al. (2025). Mechanistic insights into the potentiation and toxicity mitigation of myocardial infarction treatment with salvianolate and ticagrelor. Phytomedicine 141:156676. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156676

Wang, K., Wu, S., Li, P., Xiao, N., Wen, J., Lin, J., et al. (2022). Sacha inchi oil press-cake protein hydrolysates exhibit anti-hyperuricemic activity via attenuating renal damage and regulating gut microbiota. Foods 11:11162534. doi: 10.3390/foods11162534

Wang, X., Cui, Z., Luo, Y., Huang, Y., and Yang, X. (2023a). In vitro xanthine oxidase inhibitory and in vivo anti-hyperuricemic properties of sodium kaempferol-3′-sulfonate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 177:113854. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2023.113854

Wang, X., Dong, L., Dong, Y., Bao, Z., and Lin, S. (2023b). Corn silk flavonoids ameliorate hyperuricemia via PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 9429–9440. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.3c03422

Wang, Y.-A., Guo, X., Zhang, M.-Q., Sun, S.-T., Ren, Q.-D., Wang, M.-X., et al. (2025). Evaluation of anti-hyperuricemic and nephroprotective activities and discovery of new XOD inhibitors of morus alba L. root bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 343:119476. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2025.119476

Yang, H.-L., Thiyagarajan, V., Shen, P.-C., Mathew, D. C., Lin, K.-Y., Liao, J.-W., et al. (2019a). Anti-EMT properties of CoQ0 attributed to PI3K/AKT/NFKB/MMP-9 signaling pathway through ROS-mediated apoptosis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38:186. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1196-x

Yang, Q., Wang, Q., Deng, W., Sun, C., Wei, Q., Adu-Frimpong, M., et al. (2019b). Anti-hyperuricemic and anti-gouty arthritis activities of polysaccharide purified from Lonicera japonica in model rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 123, 801–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.077

Yang, T., Richards, E. M., Pepine, C. J., and Raizada, M. K. (2018). The gut microbiota and the brain–gut–kidney axis in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 14, 442–456. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0018-2

Yang, Y., Li, W., Xian, W., Huang, W., and Yang, R. (2022). Free and bound phenolic profiles of rosa roxburghii tratt leaves and their antioxidant and inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase. Front. Nutr. 9:922496. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.922496

Yao, J., He, H., Xue, J., Wang, J., Jin, H., Wu, J., et al. (2019). Mori ramulus (chin.ph.)-the dried twigs of morus alba L./part 1: discovery of two novel coumarin glycosides from the anti-hyperuricemic ethanol extract. Molecules 24:24030629. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030629

Yip, K., Cohen, R. E., and Pillinger, M. H. (2020). Asymptomatic hyperuricemia: is it really asymptomatic? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 32, 71–79. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000679

Yokose, C., Lu, N., Xie, H., Li, L., Zheng, Y., McCormick, N., et al. (2019). Heart disease and the risk of allopurinol-associated severe cutaneous adverse reactions: a general population-based cohort study. CMAJ 191, E1070–E1077. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190339

Zhang, H., Wang, D., Li, D., Bao, B., Chen, Q., Wang, S., et al. (2025). Lactobacillus paracasei N1115 alleviates hyperuricemia in mice: Regulation of uric acid metabolism as well as its impact on gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. Front. Nutr. 12:1651214. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1651214

Zhang, S., Wang, Y., Yu, M., Shang, Y., Chang, Y., Zhao, H., et al. (2022a). Discovery of herbacetin as a novel SGK1 inhibitor to alleviate myocardial hypertrophy. Adv. Sci. 9:e2101485. doi: 10.1002/advs.202101485

Zhang, S.-S., Liu, M., Liu, D.-N., Shang, Y.-F., Du, G.-H., and Wang, Y.-H. (2022b). Network pharmacology analysis and experimental validation of kaempferol in the treatment of ischemic stroke by inhibiting apoptosis and regulating neuroinflammation involving neutrophils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23:232012694. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012694

Keywords: 16S rRNAsequencing, Akt signaling pathway, hyperuricemia, in vivo study, kaempferol, moleculardynamics simulations, network pharmacology

Citation: Huang J, Wang Q, Guo X, Niu Y, Huang J, Zhang B, Guo Z, Wang Z and Feng S (2026) Unraveling the mechanism of mulberry leaf in alleviating hyperuricemia: key role of kaempferol by modulating AKT pathway and gut-kidney axis. Front. Microbiol. 17:1752775. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2026.1752775

Received: 24 November 2025; Revised: 30 December 2025;

Accepted: 05 January 2026; Published: 22 January 2026.

Edited by:

Jiajia Song, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yongli Ye, Jiangnan University, ChinaYou Zhou, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences (JAAS), China

Copyright © 2026 Huang, Wang, Guo, Niu, Huang, Zhang, Guo, Wang and Feng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuying Feng, ZnN5QGhhY3RjbS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jiawei Huang

Jiawei Huang Qianqian Wang

Qianqian Wang Xiaowen Guo

Xiaowen Guo Yuanyuan Niu

Yuanyuan Niu Junhong Huang1

Junhong Huang1 Boyi Zhang

Boyi Zhang Zilong Wang

Zilong Wang Shuying Feng

Shuying Feng