Abstract

Background:

The co-occurrence of myasthenia gravis (MG) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is rare, and their temporal sequence and shared pathogenesis remain poorly understood.

Methods:

We present the case of a 43-year-old woman with pre-existing acetylcholine receptor antibody (AChR-Ab) positive ocular MG who developed aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4-Ab) positive NMOSD. Additionally, we conducted a systematic literature review up to July 2024 to identify similar cases.

Results:

Including the present case, 74 patients were analyzed. The cohort showed a marked female predominance (89.2%). MG onset significantly preceded NMOSD onset in most patients (93.2%), with a younger mean age at onset (28.19 vs. 41.02 years, p < 0.001) and a mean interval of 12.56 years. Among tested patients, AChR-Ab was positive in 90.5% and AQP4-Ab in 73.0%. In our case, administration of the complement C5 inhibitor eculizumab led to marked clinical improvement after failure of high-dose steroid therapy.

Conclusion:

This study suggests a consistent temporal pattern wherein MG predominantly precedes NMOSD, often by years, suggesting a possible shared autoimmune predisposition. The observed response to eculizumab highlights complement pathway inhibition as a potentially effective therapeutic strategy for this complex overlap syndrome, warranting further investigation.

1 Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) are distinct antibody-mediated autoimmune neurological disorders. MG targets the neuromuscular junction, whereas NMOSD involves demyelination in the central nervous system (CNS), leading to optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (1, 2). Although MG and NMOSD are distinct clinical entities, the rare co-occurrence or sequential development of both diseases in a single individual suggests a potential shared autoimmune predisposition, leading to a level of clinical complexity and heterogeneity that surpasses what is typically seen in either condition alone. Understanding this temporal pattern and the underlying immunopathological mechanisms is crucial for improving patient management.

In this case report, we present a rare and illustrative case of a 43-year-old woman with a known history of MG who developed NMOSD, and who demonstrated a poor response to steroids but a remarkable one to eculizumab. The rapid succession of multiple severe symptoms, combined with the atypical treatment response, makes this case exceptionally uncommon in clinical practice. To better understand and contextualize this phenomenon, we conducted a comprehensive review of 73 published case reports to date (3–28). By integrating this case with a systematic review of the literature, we aim to delineate the clinical characteristics, temporal sequence, and therapeutic implications of this rare association.

2 Case presentation

A 43-year-old woman was admitted for a one-month history of intractable hiccups and vomiting culminating in rapid visual loss and ascending sensorimotor deficits. Her symptoms began approximately one month prior with persistent hiccups and severe, intractable vomiting. About ten days after the initial gastrointestinal symptoms, she developed generalized pruritus, neck pain, band-like sensation around the chest, and progressive bilateral lower limb numbness and weakness, which was more pronounced on the right side. This sensorimotor deficit ascended to involve her upper limbs, primarily the right arm, and was accompanied by urinary retention and constipation. In the ten days immediately preceding admission, she noted a rapid and significant deterioration of vision in her left eye.

Her medical history was significant for ocular myasthenia gravis (MG), characterized initially by left-sided ptosis and diplopia, and diagnosed in 2019 with positive anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody (AChR-Ab). She was initially treated with pyridostigmine (60 mg, tid), and received mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg, bid) three months later because she developed bilateral ptosis. She maintained stable symptom control on these medications for approximately five years. Notably, her ptosis did not recur after discontinuation of these medications one month prior due to severe vomiting. Other past medical histories included a COVID-19 infection in 2023 and herpes zoster affecting the right waist two months before admission.

On admission, neurological examination revealed severely impaired left-eye visual acuity (counting fingers at 30 cm and hand motion at 50 cm), reduced strength in neck flexor (grade 5-) and bilateral limbs (grade 5- in left limbs and grade 4 in right limbs). Additional findings included symmetrically decreased muscle tone, hyperreflexia (more prominent on the right), positive pathological reflexes, and diminished sensation to pinprick and vibration below the T4 dermatome bilaterally. No meningeal signs were detected. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score at admission was 4.0.

Routine blood tests, including inflammatory markers, thyroid function, and metabolic panels (homocysteine, vitamin B12, folate), were unremarkable except for hypokalemia. Due to clinical suspicion of spinal cord involvement, MRI of the brain and spinal cord was performed, which revealed a linear T2-hyperintensity in the dorsal medulla (area postrema) and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis spanning multiple cervical and thoracic segments, with patchy gadolinium enhancement (Figures 1A–D). Regarding her myasthenia gravis (MG) history, repetitive nerve stimulation indicated postsynaptic neuromuscular junction dysfunction, and serum AChR-Ab remained positive. Tests for immunoglobulins and complement showed an elevated C1q level (242.30 mg/L). Tumor marker screening revealed mild elevation of carbohydrate antigen 72–4 (10.29 U/mL), although chest and abdominal CT scans showed no thymic pathology or other tumors. Further evaluations included visual evoked potentials, which showed an absent P100 wave in the left eye and delayed latency in the right, and bladder ultrasound demonstrating mild post-void residual urine (76 mL).

Figure 1

Magnetic resonance imaging and clinical timeline of the patient. (A–D) MRI of the patient at time of admission: sagittal view of the cervical and thoracic spine revealed multiple T2-weighted hypersignal lesions in the posterior bulbar (area postrema), cervical (A) and thoracic medulla (B), with some lesions showing contrast enhancement in contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (C,D; arrows). (E) Detailed graphical timeline of the patient’s symptoms. IVMP, intravenous methylprednisolone; EDSS, Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Based on imaging findings indicative of myelitis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was performed. CSF analysis revealed a normal cell count with mildly elevated protein (0.55 g/L). Neuroimmunological testing showed type III oligoclonal bands, an elevated albumin quotient (15.23 × 10−3), and positive aquaporin-4 antibody (AQP4-Ab) in both serum and CSF (titer 1:40) by cell-based assay. Testing for myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody and paraneoplastic antibodies was negative in both serum and CSF. Based on the 2015 international diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of NMOSD was confirmed in the context of pre-existing MG.

Following the diagnosis, the patient received high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/day for 5 days), which resulted in little improvement in her visual or sensorimotor symptoms. Eculizumab was initiated 1 week later at a dose of 900 mg weekly for 4 weeks, followed by 1,200 mg every 2 weeks. Marked clinical improvement was observed within 24 h after first eculizumab infusion. After 1 week, her left-eye visual acuity had improved to counting fingers at 2 meters, sensory function had improved above the T8 level, and her EDSS score decreased to 2.5. She was discharged after the second eculizumab infusion. She received eculizumab for 3 months in total and was subsequently enrolled in a phase 3 clinical trial for a novel, domestically produced third-generation CD20 monoclonal antibody MIL62, on which she has remained relapse-free to date. A detailed timeline summarizing the clinical progression, diagnostic evaluations, and treatments is shown in Figure 1E.

3 Literature review

3.1 Search strategy and study selection

We conducted a systematic literature search without language restrictions using PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from inception to July 2024. The search strategy employed Boolean operators: (“myasthenia gravis” OR “MG”) AND (“neuromyelitis optica” OR “NMOSD” OR “NMO” OR “Devic’s disease”). Two authors (Y.B. and Z.N.) independently screened titles/abstracts and reviewed full texts of potentially eligible articles. Duplicate records were removed, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consultation with a third reviewer (S.C. or R.L.).

The study selection process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and is summarized in a flow diagram (Supplementary Figure S1). Articles were included if they reported one or more patients with co-occurring or sequentially diagnosed MG and NMOSD. We applied this inclusive criterion to capture cases published before the widespread availability of AQP4-IgG testing or the formalization of modern NMOSD diagnostic criteria, provided their clinical features were consistent with the current NMOSD spectrum. Articles describing MG co-occurring with typical multiple sclerosis without these distinctive NMOSD features were excluded. Review articles, commentaries, and studies lacking sufficient individual clinical data were also excluded. The reference lists of all included articles were manually searched to identify additional relevant reports.

3.2 Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 20.0. Descriptive statistics included percentages, frequencies, and means. Categorical data were represented as counts (n) with percentage and analyzed by Fisher’s exact test, whereas continuous data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (x̅ ± s) and analyzed using the t-test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.3 Summary of findings

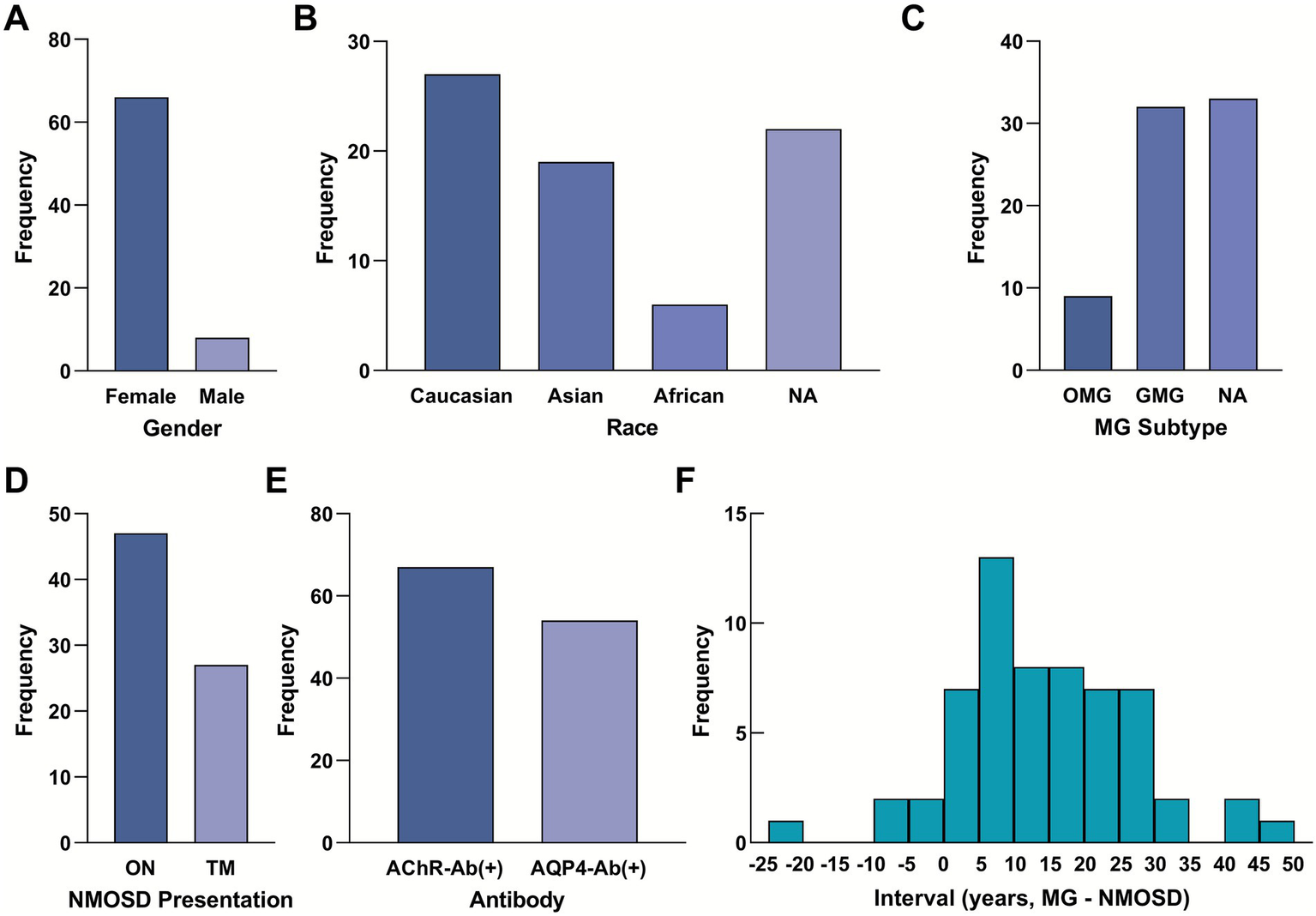

Including our present case, a total of 74 patients (73 from literature and 1 index case) with coexisting MG and NMOSD were analyzed. Detailed data are provided in Table 1, while the key demographic, clinical, and serological characteristics of this cohort are summarized in Figure 2. A pronounced female predominance was observed, with 66 female patients (89.2%) and 8 male patients (10.8%) (Figure 2A). The cohort was ethnically diverse, with the majority being of Caucasian (36.5%) or Asian (25.7%) descent (Figure 2B). Regarding the clinical subtype of MG, generalized disease was most common (43.2%), followed by ocular MG (12.2%); the subtype was not specified in 44.6% of reports (Figure 2C). The initial presentation of NMOSD was optic neuritis (ON) in 63.5% of patients and transverse myelitis (TM) in 36.5% (Figure 2D).

Table 1

| Case and references | Count (n) | Gender | Race | MG type | Age of MG onset (years) | Age of NMOSD onset (years) | Interval (years) | AChR Antibody | AQP4 Antibody | Thymectomy | Pathology | NMOSD presentation | NMOSD treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoine et al. (3) | 1 | M | NA | Generalized | 49 | 49 | 0.6 | (+) | NA | (+) | Thymoma | TM | IVMP, PLEX, cyclophosphamide |

| Balarabe et al. (4) | 1 | F | African | Generalized | 8 | 14 | 6 | (+) | (+) | (+) | Hyperplasia | ON | IVMP, oral steroids |

| Bates et al. (5) | 1 | F | NA | NA | 39 | 54 | 15 | (+) | (+) | (+) | NA | TM | IVMP, eculizumab |

| Bichuetti et al. (6) | 1 | F | Caucasian | Generalized | 27 | 31 | 4 | NA | NA | (+) | NA | TM | IVMP, AZA, oral steroids |

| Castro-Suarez et al. (7) | 2 | 2F | NA | Ocular | 20, 18 | 49, 23 | 29, 5 | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | Hyperplasia | 1ON, 1TM | IVMP, AZA, oral steroids |

| Etemadifar et al. (8) | 1 | F | Caucasian | Generalized | 42 | 33 | −9 | (+) | (+) | NA | NA | ON | PLEX, mitoxantrone, AZA, oral steroids |

| Furukawa et al. (9) | 2 | 2F | Asian | NA | 23, 63 | 48, 63 | 25, 0 | 2(+) | 2(−) | 1(+), 1(−) | 1Hyperplasia, 1NA | 2ON | IVMP, oral steroids |

| Gotkine et al. (10) | 1 | F | NA | Generalized | 10 | 26 | 16 | (+) | NA | (+) | NA | TM | IVMP, PLEX for severe relapse |

| Hironishi et al. (11) | 1 | F | Asian | Generalized | 23 | 30 | 7 | (+) | (−) | (+) | Hyperplasia | ON | AZA, oral steroids, intermittent IVMP, IVIG |

| Ikeda et al. (12) | 1 | F | Asian | NA | 29 | 45 | 16 | (−) | NA | (+) | Hyperplasia | TM | IVMP |

| Ikeguchi et al. (13) | 3 | 2F, 1 M | Asian | Generalized | 25, 41, 47 | 49, 53, 70 | 24, 12, 23 | 3(+) | 2(+), 1(−) | 2(+), 1(−) | Thymoma, 1Normal, 1NA | 2TM, 1ON | IVMP, PLEX (in one case), oral steroids |

| Isbister et al. (14) | 1 | F | Asian | Generalized | 28 | 36 | 8 | (+) | NA | (+) | Hyperplasia | ON | NA |

| Jarius et al. (15) | 10 | 10F | Caucasian | NA | 11–33 (23.4) | 20–67 (44.3) | 0–46 | 9(+), 1(−) | 10(+) | 6(+), 4(−) | 3Hyperplasia, 1Thymitis, 2Normal, 4NA | 5TM, 5ON | NA |

| Kay et al. (16) | 1 | F | Asian | Ocular | 44 | 49 | 5 | (+) | (+) | (−) | NA | ON | AZA, oral steroids |

| Kister et al. (17) | 4 | 4F | 2African, 1Caucasian, 1Asian | 2Ocular, 2 Generalized | 38, 36, 17, 27 | 39, 41, 19, 38 | 1, 5, 2, 11 | 4(+) | 2(+), 1(−), 1NA | 4(+) | 3Hyperplasia, 1NA | 3ON, 1TM | AZA, steroids; IVMP+IVIG for relapses |

| Kohsaka et al. (18) | 1 | F | Asian | NA | 53 | 60 | 7 | (+) | (+) | (+) | Hyperplasia | TM | IVMP, IVIG, tacrolimus, steroids |

| Leite et al. (19) | 16 | 15F, 1 M | 11Caucasian, 3African, 1Asian, 1NA | 2Ocular, 13 Generalized | 12–47 (26.5) | 23–67 (39.5) | −24-41 | 16(+) | 16(+) | 11(+), 5(−) | 8Hyperplasia, 3Normal, 5NA | 8ON, 8TM | AZA + steroids, rituximab, cyclophosphamide |

| Nakamura et al. (20) | 1 | F | Asian | NA | 28 | 38 | 10 | (+) | (+) | (+) | NA | ON | IVMP |

| O’Riordan et al. (21) | 1 | F | Caucasian | NA | NA | 41 | NA | (+) | NA | NA | NA | ON | IVMP, cyclophosphamide |

| Ogaki et al. (22) | 1 | F | Asian | Generalized | 30 | 43 | 13 | (+) | (+) | (+) | NA | ON | IVMP, oral steroids |

| Spillane et al. (23) | 1 | F | NA | Generalized | 23 | 31 | 7 | (+) | (+) | (+) | Normal | TM | AZA, oral steroids |

| Tsujii et al. (24) | 1 | F | Asian | Generalized | 10 | 33 | 23 | (+) | (+) | (+) | Hyperplasia | ON | IVMP (ineffective), PLEX, oral steroids |

| Uzawa et al. (25) | 2 | 2F | Asian | Generalized | 20, 18 | 41, 27 | 21, 9 | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | 1Hyperplasia, 1NA | 2ON | IVMP, PLEX, oral steroids, tacrolimus |

| Vaknin et al. (26) | 15 | 10F, 5 M | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 11(+), 4(−) | 7(+), 8(−) | 9(+), 6(−) | 7Thymoma, 2Hyperplasia, 6NA | 14ON, 1TM | NA |

| Vakrakou et al. (27) | 2 | 2F | Caucasian | Generalized | 24, 17 | 49, 21 | 25, 4 | 2(+) | 2(+) | 2(+) | Normal | 1TM, 1ON | IVMP, PLEX, AZA, oral steroids, rituximab (in one case) |

| Yau et al. (28) | 1 | F | Asian | Ocular | 56 | 51 | −5 | (+) | (+) | (−) | NA | ON | IVMP, AZA, oral steroids |

| This case | 1 | F | Asian | Ocular | 38 | 43 | 5 | (+) | (+) | (−) | NA | TM | IVMP, eculizumab |

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with the coexistence of NMOSD and MG.

MG, myasthenia gravis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; AQP4-Ab, aquaporin-4 antibody; AChR-Ab, acetylcholine receptor antibody; ON, optic neuritis; TM, transverse myelitis; IVMP: Intravenous Methylprednisolone; PLEX: Plasma Exchange; AZA: Azathioprine; IVIG: Intravenous Immunoglobulin; NA: Not Available.

Figure 2

Demographic, clinical, and serological profile of 74 patients with coexisting myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. (A) Gender distribution of the cohort (Female: 89.2%, n = 66; Male: 10.8%, n = 8). (B) Racial distribution (Caucasian: 36.5%, n = 27; Asian: 25.7%, n = 19; African: 8.1%, n = 6; Unknown: 29.7%, n = 22). (C) Distribution of MG types (Generalized: 43.2%, n = 32; Ocular: 12.2%, n = 9; Unknown: 44.6%, n = 33). (D) Initial NMOSD presentation (ON: 63.5%, n = 47; TM: 36.5%, n = 27). (E) Seropositivity rates for key antibodies (AChR-Ab positive: 90.5%, n = 67; AQP4-Ab positive: 73.0%, n = 54). (F) Histogram showing the distribution of the interval between the onset of MG and NMOSD (n = 57 with reported interval data). Negative values indicate that NMOSD onset preceded MG. The mean interval is 12.56 ± 12.99 years. MG, myasthenia gravis; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder; ON, optic neuritis; TM, transverse myelitis; AChR-Ab, acetylcholine receptor antibody; AQP4-Ab, aquaporin-4 antibody.

Serologically, the vast majority of patients were positive for disease-specific autoantibodies: AChR-Ab was positive in 90.5% of tested patients, and AQP4-Ab was positive in 73.0% (Figure 2E). A high proportion of patients (70.3%) had undergone thymectomy. Among those with reported histopathology (n = 41), thymic hyperplasia was the most common finding (53.7%), followed by thymoma (22.0%) and normal histology (22.0%).

The temporal relationship between the two disorders was prominent. In the majority of cases (93.2%, 69/74), MG onset consistently preceded NMOSD onset by years (mean interval 12.56 years). The mean age of onset for MG was 28.19 ± 11.78 years, which was significantly younger than the mean age of NMOSD onset at 41.02 ± 13.40 years (p < 0.001). The interval between diagnoses varied widely, with a mean interval of 12.56 ± 12.99 years. The distribution of these intervals is visualized in Figure 2F.

4 Discussion

The sequential occurrence of MG and NMOSD is uncommon, and their overlapping epidemiological characteristics remain inadequately defined. MG has an estimated annual incidence of 1.5–3.1 per 100,000, with onset possible across all ages but more common in women aged 20–50 years and men over 65 (29, 30). In contrast, NMOSD shows a lower incidence of about 0.278 per 100,000 and predominately affects young to middle-aged women (31, 32). Consistent with known female preponderance in autoimmunity, our review identified a marked female predominance (89.2%) among patients with both conditions. The cohort was ethnically diverse, with Caucasians (36.5%) and Asians (25.7%) representing the majority. Although MG generally preceded NMOSD, the sequence of onset occasionally varied, as observed in some reports and in the present case.

Both MG and NMOSD are antibody-mediated autoimmune disorders, but they differ in target tissues and primary immunopathological mechanisms. MG results from impaired neuromuscular transmission driven mainly by AChR-Ab, supported by cellular immunity and complement activation (1). In contrast, NMOSD is primarily humoral, with AQP4-Ab playing a key pathogenic role (2). Other immune-mediated disorders, such as autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy, further illustrate the spectrum of CNS autoimmunity (33, 34). In our patient, positivity for both AChR-Ab and AQP4-Ab reinforces the contribution of disease-specific autoantibodies. Notably, MG symptoms did not recur or worsen after NMOSD onset, possibly reflecting immune rebalancing. The frequent co-occurrence of both antibodies and the observed temporal pattern suggest a shared immunological predisposition, as also indicated by studies on the causal links between NMOSD and other autoimmune diseases (35).

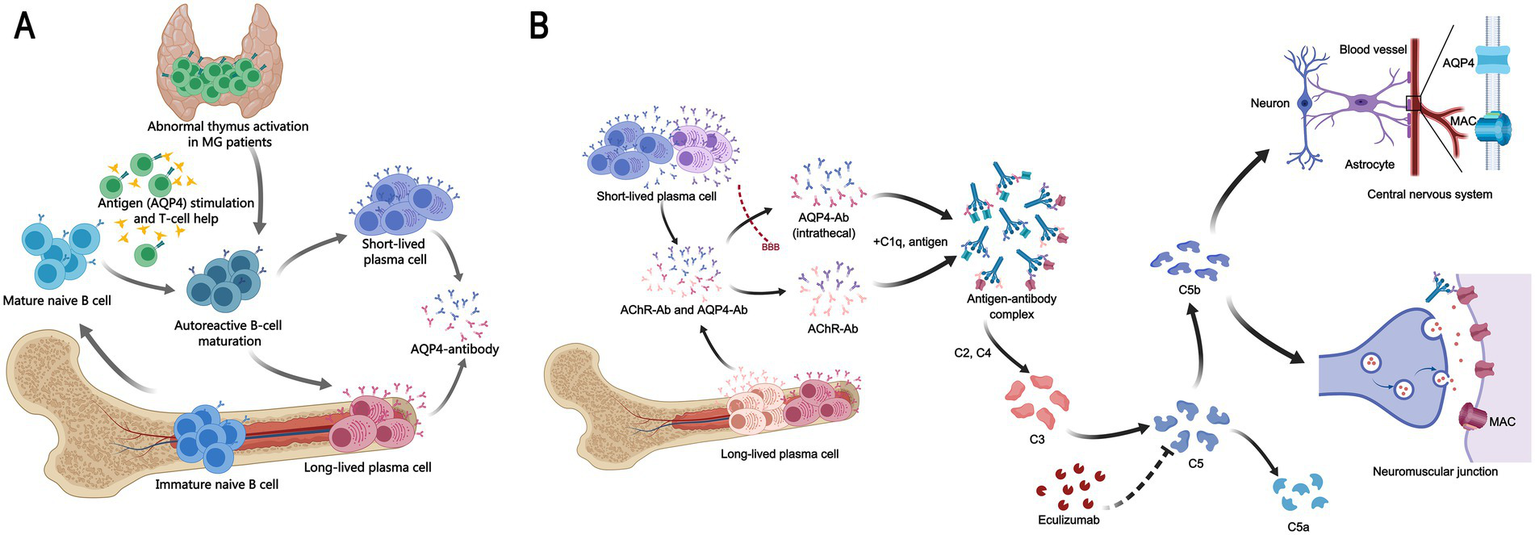

We propose a pathogenic model in which MG—often associated with thymic pathology—may initiate systemic B-cell dysregulation, eventually enabling the emergence of AQP4-specific autoimmunity (Figure 3A). This model accommodates cases where NMOSD develops even after thymectomy, indicating that autoreactive clones may become established independently of the thymic microenvironment. The discontinuation of mycophenolate mofetil prior to NMOSD onset in our case might have reduced immunosuppressive control, allowing breakthrough autoimmunity. Elevated complement C1q further supports complement dysregulation as a common pathway in both diseases, consistent with the recognized role of complement in their pathogenesis (34).

Figure 3

Mechanistic insights into the MG-NMOSD association and therapy. (A) Proposed immunopathogenic link between MG and NMOSD. A schematic illustrating a hypothesized cascade: MG, commonly with abnormal thymus activation like thymic hyperplasia, may induce systemic immune dysregulation. This environment could promote the emergence of autoreactive B cells that produce pathogenic AQP4-Ab, triggering NMOSD. This model may apply to a subset of patients, as NMOSD can develop post-thymectomy. (B) Mechanism of action of eculizumab in MG and NMOSD. The complement inhibitor eculizumab blocks cleavage of C5, preventing membrane attack complex (MAC) formation. In MG (below), this inhibits MAC-mediated damage at the neuromuscular junction initiated by AChR-Ab. In NMOSD (above), it blocks AQP4-ab-driven, complement-dependent astrocytic injury. Thus, it shares a molecular target (C5) but acts in distinct pathogenic contexts.

Management of patients with sequential MG and NMOSD remains clinically challenging. Early recognition of NMOSD in patients with established MG is crucial. Current treatment relies largely on immunomodulatory strategies overlapping between the two disorders, including steroids and conventional immunosuppressants. Plasma exchange and intravenous immunoglobulin may be used in acute severe attacks. However, therapeutic decisions must balance the severity and interaction of each disease. The development of targeted biologics offers promising alternatives. Agents such as rituximab, satralizumab, and eculizumab have shown efficacy in clinical studies. Updated 2024 NEMOS guidelines recommend eculizumab as a first-line therapy for AQP4-Ab-positive NMOSD due to its rapid onset and sustained C5 inhibition (36). Eculizumab is approved in China and several other countries for both AChR-Ab-positive refractory generalized MG and AQP4-Ab-positive NMOSD (37), supporting a shared complement-mediated mechanism. New therapeutic avenues potentially for MG-NMOSD overlap include FcRn inhibitors (e.g., efgartigimod), next-generation complement inhibitors (e.g., ravulizumab), and B-cell targeting agents (e.g., CD19 CAR-T). Personalized immunotherapy based on serological profiles may further optimize outcomes, while experimental approaches such as stem-cell or gene therapy warrant further investigation (1, 29, 36, 38).

In our patient, high-dose corticosteroids produced limited benefit, highlighting the refractory nature of her NMOSD presentation. The subsequent rapid response to eculizumab underscores the importance of complement activation and validates therapeutic targeting of this pathway. Eculizumab inhibits terminal complement component C5, thereby blocking the final effector mechanism in both AChR-Ab- and AQP4-Ab-mediated injury (Figure 3B). After three months of stable control with eculizumab, the patient was transitioned to a third-generation CD20 monoclonal antibody under a clinical trial protocol. This sequential approach—from complement inhibition to B-cell depletion—illustrates the dynamic and personalized management required for complex autoimmune overlap syndromes and introduces a promising new therapeutic option.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis is based on published case reports, which are subject to publication bias (favoring severe/atypical presentations) and reporting bias, potentially inflating the observed female predominance and influencing the reported racial distribution. Second, diagnostic criteria evolved over time, and AQP4-IgG testing was not available for many historical cases, introducing heterogeneity and diagnostic uncertainty. Third, incomplete reporting of antibody status and clinical details, along with the lack of individual patient data, precluded advanced statistical analysis or meta-analysis. Finally, while a temporal association is clear, this study cannot establish causality or definitively prove a shared pathogenic mechanism between MG and NMOSD.

In conclusion, this analysis provides insight into the clinical characteristics and potential immunopathological links in patients with sequential MG and NMOSD. The consistent pattern of MG preceding NMOSD, the frequent presence of both AChR-Ab and AQP4-Ab, and the response to complement inhibition suggest overlapping autoimmune diatheses. Further large-scale, multicenter studies are needed to elucidate shared mechanisms and to develop more precise therapeutic strategies for this complex overlap syndrome.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board of Peking University First Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZN: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision, Data curation. LY: Visualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources. JR: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources. JW: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology. JG: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. NZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. FG: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Project administration, Investigation. HH: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Data curation, Resources, Project administration, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. RL: Visualization, Data curation, Resources, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Cross-Disciplinary Research Fond of Peking University First Hospital (grant no. 2023IR07).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2026.1747855/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Iorio R . Myasthenia gravis: the changing treatment landscape in the era of molecular therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. (2024) 20:84–98. doi: 10.1038/s41582-023-00916-w,

2.

Gholizadeh S Exuzides A Lewis KE Palmer C Waltz M Rose JW et al . Clinical and epidemiological correlates of treatment change in patients with NMOSD: insights from the CIRCLES cohort. J Neurol. (2023) 270:2048–58. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11529-6,

3.

Antoine JC Camdessanché JP Absi L Lassablière F Féasson L . Devic disease and thymoma with anti-central nervous system and antithymus antibodies. Neurology. (2004) 62:978–80. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000115168.73299.88,

4.

Balarabe SA Adamu MD Watila MM Jiya N . Neuromyelitis optica and myasthenia gravis in a young Nigerian girl. BMJ Case Rep. (2015) 2015:bcr2014207362. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207362,

5.

Bates M Chisholm J Miller E Avasarala J Guduru Z . Anti-MOG and anti-AQP4 positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2020) 44:102205. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102205,

6.

Bichuetti DB Barros TM Oliveira EM Annes M Gabbai AA . Demyelinating disease in patients with myasthenia gravis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2008) 66:5–7. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2008000100002,

7.

Castro-Suarez S Guevara-Silva E Caparó-Zamalloa C Cortez J Meza-Vega M . Neuromyelitis optica in patients with myasthenia gravis: two case-reports. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2020) 43:102173. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102173,

8.

Etemadifar M Abtahi SH Dehghani A Abtahi MA Akbari M Tabrizi N et al . Myasthenia gravis during the course of Neuromyelitis Optica. Case Rep Neurol. (2011) 3:268–73. doi: 10.1159/000334128,

9.

Furukawa Y Yoshikawa H Yachie A Yamada M . Neuromyelitis optica associated with myasthenia gravis: characteristic phenotype in Japanese population. Eur J Neurol. (2006) 13:655–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01392.x,

10.

Gotkine M Fellig Y Abramsky O . Occurrence of CNS demyelinating disease in patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurology. (2006) 67:881–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234142.41728.a0,

11.

Hironishi M Ishimoto S Sawanishi T Miwa H Kawachi I Kondo T . Neuromyelitis optica following thymectomy with severe spinal cord atrophy after frequent relapses for 30 years. Brain Nerve. (2012) 64:951–5.

12.

Ikeda K Araki Y Iwasaki Y . Occurrence of CNS demyelinating disease in patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurology. (2007) 68:1326–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234142.41728.a0

13.

Ikeguchi R Shimizu Y Suzuki S Shimizu S Kabasawa C Hashimoto S et al . Japanese cases of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder associated with myasthenia gravis and a review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2014) 125:217–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.07.036,

14.

Isbister CM Mackenzie PJ Anderson D Wade NK Oger J . Co-occurrence of multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis in British Columbia. Mult Scler. (2003) 9:550–3. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms964oa,

15.

Jarius S Paul F Franciotta D de Seze J Münch C Salvetti M et al . Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders in patients with myasthenia gravis: ten new aquaporin-4 antibody positive cases and a review of the literature. Mult Scler. (2012) 18:1135–43. doi: 10.1177/1352458511431728,

16.

Kay CS Scola RH Lorenzoni PJ Jarius S Arruda WO Werneck LC . NMO-IgG positive neuromyelitis optica in a patient with myasthenia gravis but no thymectomy. J Neurol Sci. (2008) 275:148–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.06.038

17.

Kister I Gulati S Boz C Bergamaschi R Piccolo G Oger J et al . Neuromyelitis optica in patients with myasthenia gravis who underwent thymectomy. Arch Neurol. (2006) 63:851–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.6.851,

18.

Kohsaka M Tanaka M Tahara M Araki Y Mori S Konishi T . A case of subacute myelitis with anti-aquaporin 4 antibody after thymectomy for myasthenia gravis: review of autoimmune diseases after thymectomy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. (2010) 50:111–3. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.50.111,

19.

Leite MI Coutinho E Lana-Peixoto M Apostolos S Waters P Sato D et al . Myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a multicenter study of 16 patients. Neurology. (2012) 78:1601–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825644ff,

20.

Nakamura M Nakashima I Sato S Miyazawa I Fujihara K Itoyama Y . Clinical and laboratory features of neuromyelitis optica with oligoclonal IgG bands. Mult Scler. (2007) 13:332–5. doi: 10.1177/13524585070130030201,

21.

O'Riordan JI Gallagher HL Thompson AJ Howard RS Kingsley DP Thompson EJ et al . Clinical, CSF, and MRI findings in Devic's neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1996) 60:382–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.60.4.382,

22.

Ogaki K Hirayama T Chijiiwa K Fukae J Furuya T Noda K et al . Anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-positive definite neuromyelitis optica in a patient with thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Neurologist. (2012) 18:76–9. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e318247bc91,

23.

Spillane J Christofi G Sidle KC Kullmann DM Howard RS . Myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis opica: a causal link. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2013) 2:233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2013.01.003,

24.

Tsujii T Nishikawa N Tanabe N Iwaki H Nagai M Nomoto M . Myasthenia gravis complicated with optic neuritis showing anti-aquaporin 4 antibody: a case report. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. (2012) 52:503–6. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.52.503,

25.

Uzawa A Mori M Iwai Y Kobayashi M Hayakawa S Kawaguchi N et al . Association of anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica with myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Sci. (2009) 287:105–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.040,

26.

Vaknin-Dembinsky A Abramsky O Petrou P Ben-Hur T Gotkine M Brill L et al . Myasthenia gravis-associated neuromyelitis optica-like disease: an immunological link between the central nervous system and muscle?Arch Neurol. (2011) 68:1557–61. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.200,

27.

Vakrakou A Chatzistamatiou T Koros C Karathanasis D Tentolouris-Piperas V Tzanetakos D et al . HLA-genotyping by next-generation-sequencing reveals shared and unique HLA alleles in two patients with coexisting neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and thymectomized myasthenia gravis: immunological implications for mutual aetiopathogenesis?Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2022) 63:103858. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2022.103858,

28.

Yau GS Lee JW Chan TT Yuen CY . Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum disorder in a Chinese woman with ocular myasthenia gravis: first reported case in the Chinese population. Neuroophthalmology. (2014) 38:140–4. doi: 10.3109/01658107.2013.879903,

29.

Wartmann H Hoffmann S Ruck T Nelke C Deiters B Volmer T . Incidence, prevalence, hospitalization rates, and treatment patterns in myasthenia gravis: a 10-year real-world data analysis of German claims data. Neuroepidemiology. (2023) 57:121–8. doi: 10.1159/000529583,

30.

Rodrigues E Umeh E Aishwarya NN Cole A Moy K . Incidence and prevalence of myasthenia gravis in the United States: a claims-based analysis. Muscle Nerve. (2024) 69:166–71. doi: 10.1002/mus.28006,

31.

Bagherieh S Afshari-Safavi A Vaheb S Kiani M Ghaffary EM Barzegar M et al . Worldwide prevalence of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) and neuromyelitis optica (NMO): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. (2023) 44:1905–15. doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-06617-y,

32.

Tian DC Li Z Yuan M Zhang C Gu H Wang Y et al . Incidence of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) in China: a national population-based study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. (2020) 2:100021. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100021,

33.

Shan F Long Y Qiu W . Autoimmune glial fibrillary acidic protein astrocytopathy: a review of the literature. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2802. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02802,

34.

Chamberlain JL Huda S Whittam DH Matiello M Morgan BP Jacob A . Role of complement and potential of complement inhibitors in myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: a brief review. J Neurol. (2021) 268:1643–64. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09498-4,

35.

Wang X Shi Z Zhao Z Chen H Lang Y Kong L et al . The causal relationship between neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and other autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:959469. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.959469,

36.

Kümpfel T Giglhuber K Aktas O Ayzenberg I Bellmann-Strobl J Häußler V et al . Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD)—revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica study group (NEMOS). Part II: attack therapy and long-term management. J Neurol. (2024) 271:141–76. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11910-z,

37.

Narayanaswami P Sanders DB Wolfe G Benatar M Cea G Evoli A et al . International consensus guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis: 2020 update. Neurology. (2021) 96:114–22. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011124,

38.

Carnero Contentti E Correale J . Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: from pathophysiology to therapeutic strategies. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:208. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02249-1,

Summary

Keywords

acetylcholine receptor antibody, aquaporin 4, eculizumab, myasthenia gravis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder

Citation

Niu Z, Bao Y, Yao L, Ren J, Wang J, Guo J, Zhang N, Gao F, Hao H, Chen S and Liu R (2026) The temporal sequence of myasthenia gravis and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a case report and systematic review of 74 patients. Front. Neurol. 17:1747855. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2026.1747855

Received

25 November 2025

Revised

26 January 2026

Accepted

30 January 2026

Published

13 February 2026

Volume

17 - 2026

Edited by

Valerie Biousse, Emory University, United States

Reviewed by

Leanne Stunkel, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Chandra Bhushan Prasad, Healthway Hospitals, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Niu, Bao, Yao, Ren, Wang, Guo, Zhang, Gao, Hao, Chen and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Siwei Chen, siwei_chen1993@163.com; Ran Liu, dyyxys@126.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.