- Department of Radiation Oncology, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China

Purpose: This study was conducted in order to develop a trajectory optimization algorithm for non-coplanar volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) and investigate the potential of organs at risk (OARs) sparing in locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients using non-coplanar VMAT.

Methods and Materials: Firstly, a cost map that represents the ray–OAR voxel intersections at each source position was generated using a ray-tracing algorithm. A graph search algorithm was then used to determine the least-cost path from the cost map. Lastly, full arcs or partial arcs were selected based on the least-cost path to generate the non-coplanar VMAT (ncVMAT) trajectories. Clinical coplanar VMAT (coVMAT) plans for 11 patients diagnosed with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer (LAPC) receiving 45 to 70 Gy in 25 fractions were replanned using non-coplanar VMAT trajectories. Both coplanar and non-coplanar plans were normalized to cover 95% of the PTV45 Gy volume with a prescription dose of 45 Gy. The conformity index (CI), homogeneity index (HI), PTV coverage, and dose to the OARs were compared between coVMAT and ncVMAT plans.

Results: With ncVMAT, the mean coverage of PTV50 Gy, PTV54 Gy, PTV60 Gy, and PTV70 Gy increased significantly. The mean conformity index of PTV45 Gy, PTV54 Gy, and PTV70 Gy was also improved in the ncVMAT plans. Compared with coVMAT plans, the ncVMAT plans resulted in significantly lower doses to the spinal cord, bilateral kidneys, stomach, and duodenum. The maximum dose to the spinal cord decreased by 6.11%. The mean dose to the left and right kidneys decreased by an average of 5.52% and 11.71%, respectively. The Dmax, Dmean, and D15% of the stomach were reduced by an average of 7.45%, 15.82%, and 16.79%, separately. The D15% and Dmean of the duodenum decreased 6.38% and 5.64%, respectively.

Conclusion: A trajectory optimization algorithm was developed for non-coplanar VMAT. Compared with conventional coplanar VMAT, non-coplanar VMAT resulted in improved coverage and conformity to the targets. The sparing of OARs was significantly improved in non-coplanar VMAT compared with coVMAT plans for locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society, pancreatic cancer was the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide for both genders in 2018 (1). The only curative therapy for patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer is surgical resection. Nevertheless, only 15%–20% of these patients presented with resectable tumors (2). The standard care for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer is chemotherapy and/or chemoradiotherapy (3). However, conventionally fractionated radiotherapy which delivers 40 to 60 Gy in 1.8–2.0 Gy per fraction showed minimal to no local tumor control benefit for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) (4). With the development of image-guided radiotherapy and immobilization techniques, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) which precisely delivers a high dose per fraction has become a promising option for the treatment of patient with LAPC. A study that investigated the outcomes of patients treated with SBRT using the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) showed that the median overall survival (OS) (13.9 vs. 11.6 months) and the 2-year OS rate (21.7% vs. 16.5%) were significantly higher with SBRT versus conventionally fractionated radiation therapy (5). The reason why SBRT resulted in a better survival rate is that SBRT allows to deliver a higher biological effective dose (BED) to patients and higher BED is associated with better local control. On the other hand, early studies implementing SBRT were associated with high early and/or late gastrointestinal side effects (6, 7). Therefore, the sparing of radiosensitive gastrointestinal organs such as the stomach, small intestines, colon, and duodenum near the pancreas becomes the main difficulty of dose escalation in LAPC patients (4).

A lot of studies have been done to investigate the application of non-coplanar radiotherapy in OAR dose sparing for different sites. Evidence has shown that non-coplanar plans were superior in normal tissue sparing compared with the conventional coplanar technique (8–12). Smyth et al. evaluated non-coplanar VMAT for OAR sparing in primary brain tumor radiotherapy (13). They found that compared with coplanar VMAT, non-coplanar VMAT significantly reduced doses to the contralateral lobe, optic nerve, hippocampus, and temporal lobe for patients with primary brain tumors. Yu et al. reported the first clinical implementation of 4π radiation therapy in recurrent high-grade glioma patients (14). Twenty beam orientations were used for optimization. The results showed that compared with coplanar VMAT, 4π IMRT plans resulted in equal or significantly lower OAR doses. A study shows that in head and neck cases, non-coplanar IMRT can significantly reduce dose to hippocampi and whole brain which helps preserve neurocognitive function (15). Another study of non-coplanar VMAT for brain metastases shows that non-coplanar VMAT generated more rapid dose falloff and higher conformity compared with co-planar VMAT (8). Uto et al. compared coplanar VMAT and non-coplanar VMAT for hippocampus protection in craniopharyngioms cases and found that non-coplanar VMAT significantly reduced the dose to bilateral hippocampus (16). The two non-coplanar arcs were set at couch angles of 45° and 315°. Similarly, Cheung et al. applied non-coplanar VMAT to primary brain tumor using non-coplanr arcs with couch rotated to 45° or 315° (17). An alternative approach to non-coplanar IMRT or non-coplanar VMAT is the VMAT+ technique proposed by Sharfo et al. which combined full coplanar arcs with few non-coplanar beams with optimized beam angles (18). The advantage of the VMAT+ technique is that it has similar plan quality to fully non-coplanar IMRT but much shorter treatment delivery time.

Non-coplanar techniques have also been implemented in the management of pancreatic cancer. Chang et al. found that non-coplanar IMRT was able to significantly decrease bilateral kidney dose for unresectable pancreatic cancer compared with coplanar IMRT (19). The non-coplanar IMRT beam angles were manually selected in beam’s eye view (BEV) to spare the kidneys. Osborne et al. also found that the non-coplanar plans show overall benefits over coplanar plans (20). Two lateral wedged oblique fields and two wedged non-coplanar oblique fields were used. Burghelea et al. investigated non-coplanar trajectories for LAPC cases using dynamic wave arc on the VERO gimballed linac (21). However, the beam directions were selected by a human planner. Previous studies on pancreatic cancer were based on the IMRT technique or the beam angles were selected manually due to the complexity of beam orientation optimization (22). In this study, we present an implementation of non-coplanar VMAT technique which utilized cost map generation and trajectory optimization algorithm for OAR dose sparing in LAPC patients.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent was waived. Eleven patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with conventional coplanar VMAT plans were selected in our study. Patients were simulated using Philips Brilliance Big-Bore helical CT with 3 mm slice thickness. Plans were designed and optimized using VMAT techniques with simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) in the Eclipse treatment planning system (Varian Medical System, Palo Alto, CA, USA). PTV prescription dose includes 45 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions, 50 Gy in 2 Gy fractions, 54 Gy in 2.14 Gy fractions, 60 Gy in 2.4 Gy fractions, and 70 Gy in 2.8 Gy fractions. The average planning target volume (PTV) size was 435.31 cm3 for PTV45 Gy, 215.32 cm3 for PTV50 Gy, 45.50 cm3 for PTV54 Gy, 43.53 cm3 for PTV60 Gy, and 20.37 cm3 for PTV70 Gy.

Data Input

For each patient, the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) structure set which contains isocenter position, contours of PTV, and OARs were exported from Eclipse treatment planning system into MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) to generate a 3D patient phantom for ray-tracing simulation.

Ray Tracing and Cost Map Generation

The gantry rotated from 0° to 360° with control points spaced every 2°, and the couch rotated from 270° to 90° with control points spaced every 2°. For each source position determined by the couch and gantry angle, ray tracing was performed using a MATLAB algorithm (23). The couch and gantry angle combinations which may cause collision were eliminated from ray tracing. The collision regions were determined by measuring the permitted gantry rotation angle for each couch angle with a patient phantom placed on the couch.

For each source position, ray tracing was performed, and a list of coordinates in three dimensions of the intersected voxels was produced. Then, the number of intersected voxels in different types of OARs was calculated. The OARs evaluated in this study were the small intestines, duodenum, colon, liver, bilateral kidneys, stomach, and spinal cord.

For each source position determined by couch angle c and gantry angle g, the cost of each node Cc,g is given by the sum of the relative volume of each OAR intersected during ray tracing:

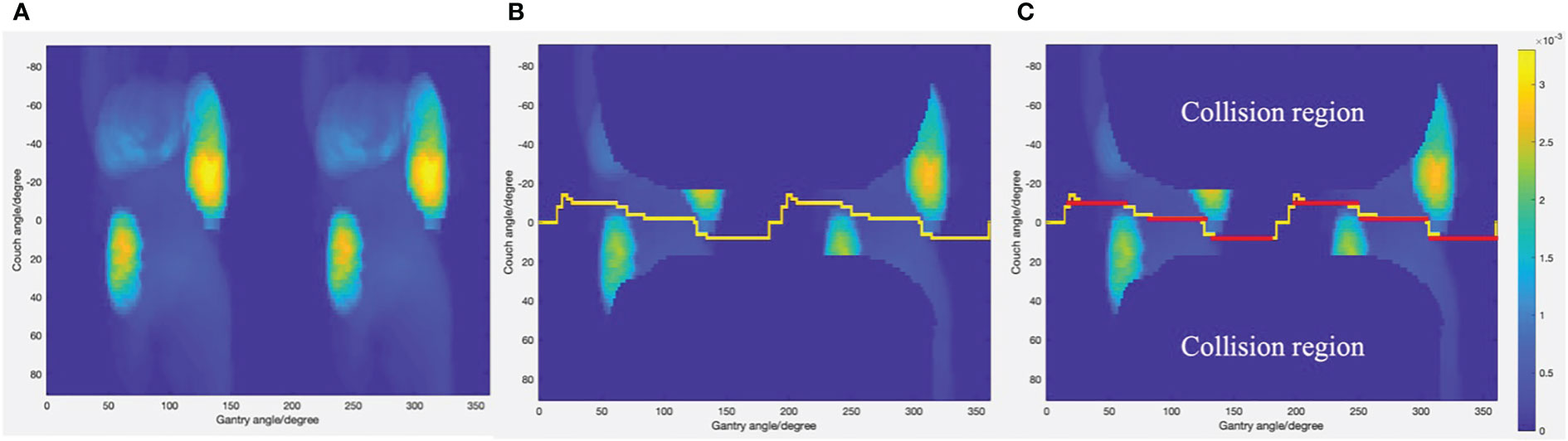

where v is the OAR of interest, V is the set of all OARs evaluated, nv is the number of organ v voxels intersected by the ray, and Nv is the total number of voxels of organ v. After the cost of each permitted source position was calculated, the cost data were reformatted into a matrix and displayed as a cost map as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1 (A) Cost map generated through ray-tracing simulation. (B) The least cost trajectory generated by Dijkstra’s algorithm displayed on cost map with collision region excluded. (C) The subarcs with fixed couch positions (displayed as red lines) adopted as final non-coplanar trajectories.

Trajectory Selection

After the cost map was generated, the trajectory optimization was simplified as a traveling salesman problem. A salesman wants to travel between several cities to sell goods. The distance to each city is different and not every city is connected. The problem is to find the shortest route between a certain number of destinations that must be visited. One constraint of the traveling salesman problem is that each city can be visited only once. Similar to the salesman problem, we want to find the least-cost trajectory through various nodes. The cost of each node is similar to the distance to each city in the traveling salesman problem. Dijkstra’s algorithm was used to find the minimal cost trajectory through the cost map. Dijkstra’s algorithm aims to find the shortest paths from a starting node to all other nodes in a weighted graph. This algorithm was created by the Dutch computer scientist Dr. Edsger W. Dijkstra. In this study, we only need to find the shortest path from the source node to a target node. The source node was at gantry angle of 0 and couch angle of 0. The target node was at gantry angle of 360 and couch angle of 0. The reason of doing this is that every gantry angle from 0° to 360° will be visited. There are four inputs when implementing Dijkstra’s algorithm. The first input is the cost of moving from node i to node j which is the sum of the cost of node i and node j. The second input is an adjacency matrix which indicates which nodes are adjacent to which other nodes in the cost map:

where gi and gj are the gantry angle of node i and node j, and ci and cj are the couch angel of node i and node j. The last two inputs are the coordinates of the source node and target node. The outputs are the minimal cost path connecting the starting node and ending node and the cost value for the path. Figure 1B shows the least-cost path generated by Dijkstra’s algorithm. Due to restrictions of the Eclipse treatment planning system, the couch and gantry cannot rotate simultaneously for VMAT plans. Therefore, the optimized trajectory was divided into several subarcs with fixed couch positions as shown in Figure 1C. Subarcs with an arc length less than 30° cannot be optimized in the treatment planning system and, therefore, were excluded from plan optimization.

Treatment Planning

The original clinical coVMAT plans consisted of two coplanar arcs with control points spaced every 2°. Plans were designed and optimized using the Eclipse planning system. Both the coplanar and non-coplanar plans were normalized to cover 95% of PTV45 Gy volume with a prescription dose of 45 Gy. Coplanar and non-coplanar plans were produced for a 6MV Varian Trilogy linear accelerator with a Millennium 120 leaf MLC. The minimal MLC width was 5 mm. The dose calculation algorithm was the anisotropic analytical algorithm (AAA). The calculation resolution was 2.5 mm.

Plan Evaluation

Multiple dose metrics were evaluated for coVMAT and ncVMAT plans. For the targets, homogeneity index (HI), conformity index (CI), and mean coverage (V100%) were compared.

The HI was defined as:

where D5% and D95% are the doses to 5% and 95% of the PTV volume.

CI was recommended by Paddicks’s formula:

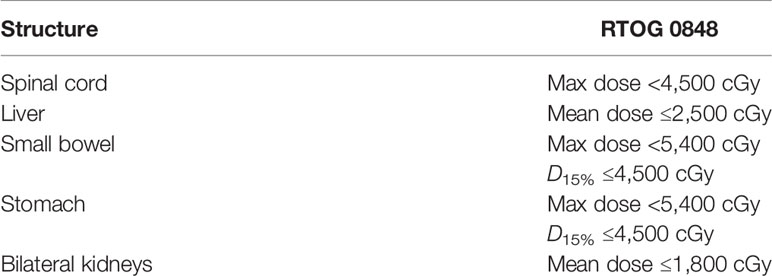

where V(PI ∩ T) is the volume of the intersection of the prescription isodoses and the target, V(T) is the volume of the target, and V(PI) is the volume of the prescription isodose. For OARs, the maximum point dose (Dmax), dose to 15% of OAR volume (D15%), dose to 2 cm3 of OAR volume (D2 cc), the portion of volume receiving 20 Gy (V20 Gy), and 40 Gy (V40 Gy) were evaluated for the small intestine, colon, and stomach. The mean dose (Dmean) was evaluated for bilateral kidneys. Dmean was evaluated for the liver. The Dmax was also evaluated for the spinal cord. Dmax and D15% were evaluated for the duodenum. Those criteria were selected according to RTOG 0848 and practice in our institution (24). Table 1 shows the normal tissue dose constraints for conventionally fractionated radiotherapy from RTOG 0848. Monitor unit (MU) was calculated for each plan. Paired t-test was used to perform statistical analysis, and a significance level of P≤0.05 (two-tailed) was used.

Results

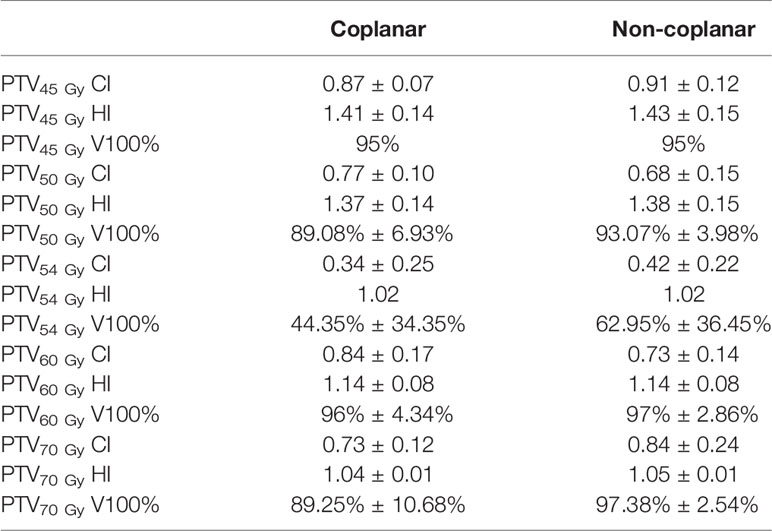

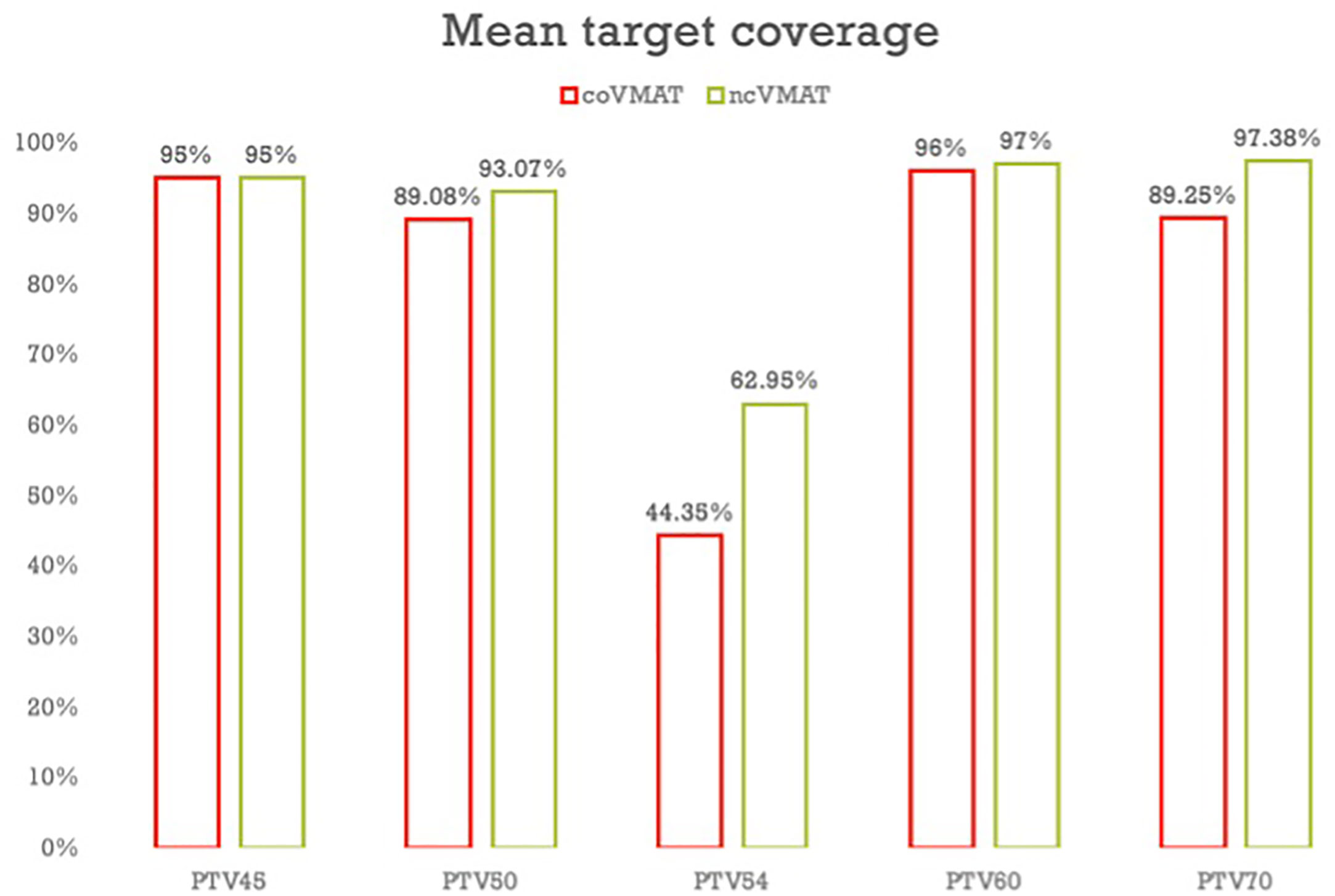

The dosimetric parameters of the PTVs are shown in Table 2. Both coVMAT and ncVMAT plans were normalized to over 95% of the PTV45 Gy volume with the prescription dose of 45 Gy. Therefore, the mean coverage of PTV45 Gy was both 95% for coVMAT and ncVMAT plans. Compared with coVMAT plans, the mean coverage of PTV50 Gy, PTV54 Gy, PTV60 Gy, and PTV70 Gy of ncVMAT plans were significantly increased. The mean conformity index of PTV45 Gy, PTV54 Gy, and PTV70 Gy was also increased, while the mean conformity index of PTV50 Gy and PTV60 Gy decreased slightly. There was no significant difference for homogeneity indexes between the coVMAT and ncVMAT plans.

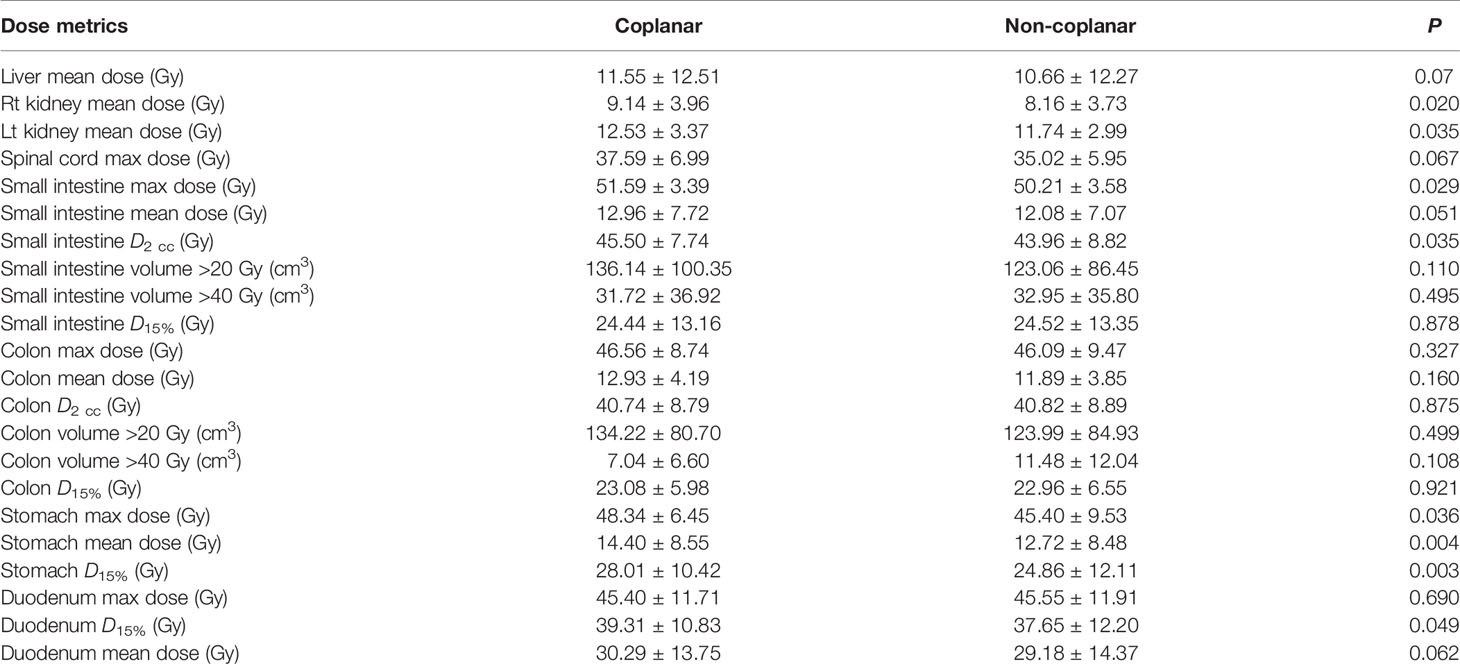

The dosimetric parameters of the OARs are shown in Table 3. Compared with coVMAT plans, the ncVMAT plans resulted in a lower dose to the liver. The mean dose to the liver was reduced by an average of 8.8%. Compared with coVMAT plans, ncVMAT plans resulted in lower doses to the spinal cord. The max dose to the spinal cord was reduced by an average of 6.11%. The ncVMAT plans also resulted in lower doses to bilateral kidneys. The mean dose to the left kidney decreased by an average of 5.52%. The mean dose to the right kidney decreased by an average of 11.71%. For the stomach, a significant improvement of the Dmax, Dmean, and D15% was observed. For the small intestines, ncVMAT resulted in lower Dmax, Dmean, D2 cc, and V20 Gy, while V40 Gy increased slightly. There was no significant difference between coVAMT and ncVAMT for small intestine D15%. The Dmean and V20 Gy of the colon decreased, while the colon V40 Gy increased. Colon Dmax, D2 cc, and D15% were similar for coVMAT and ncVMAT. Compared with coVMAT plans, ncVMAT plans also resulted in lower D15% and Dmean to the duodenum.

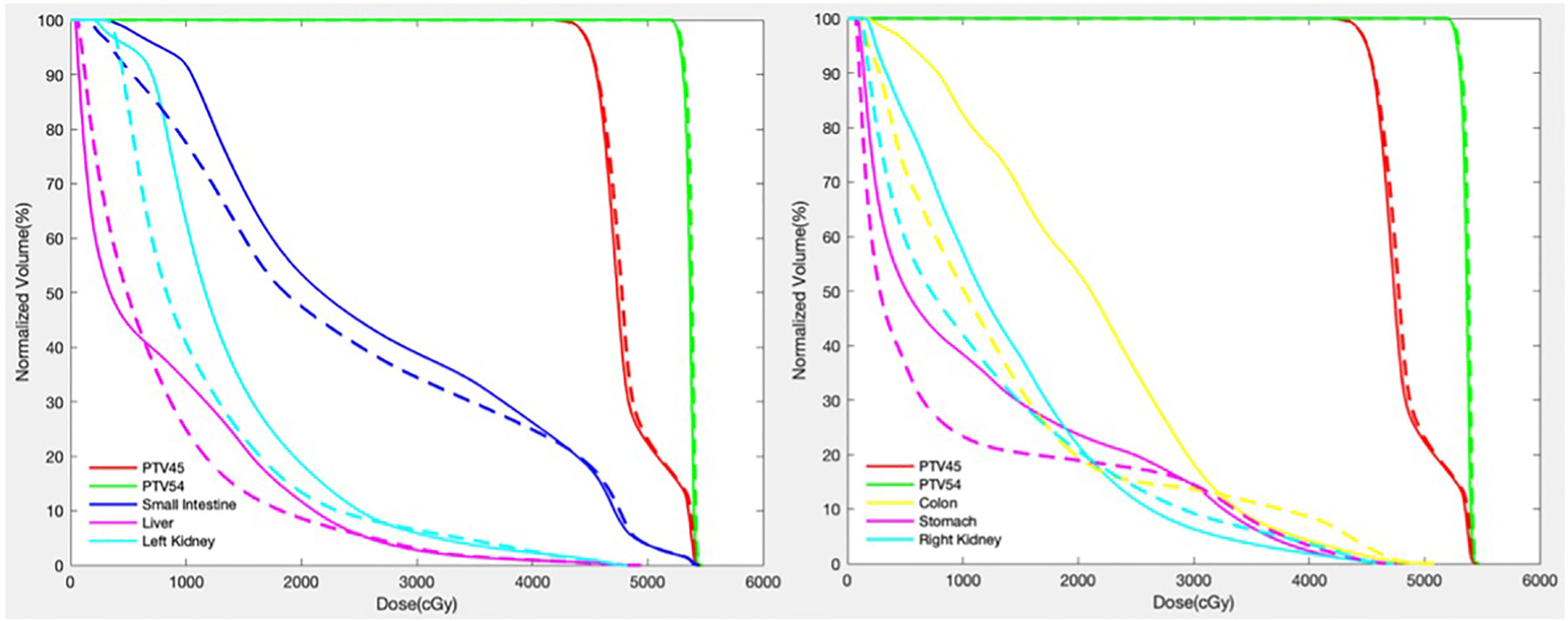

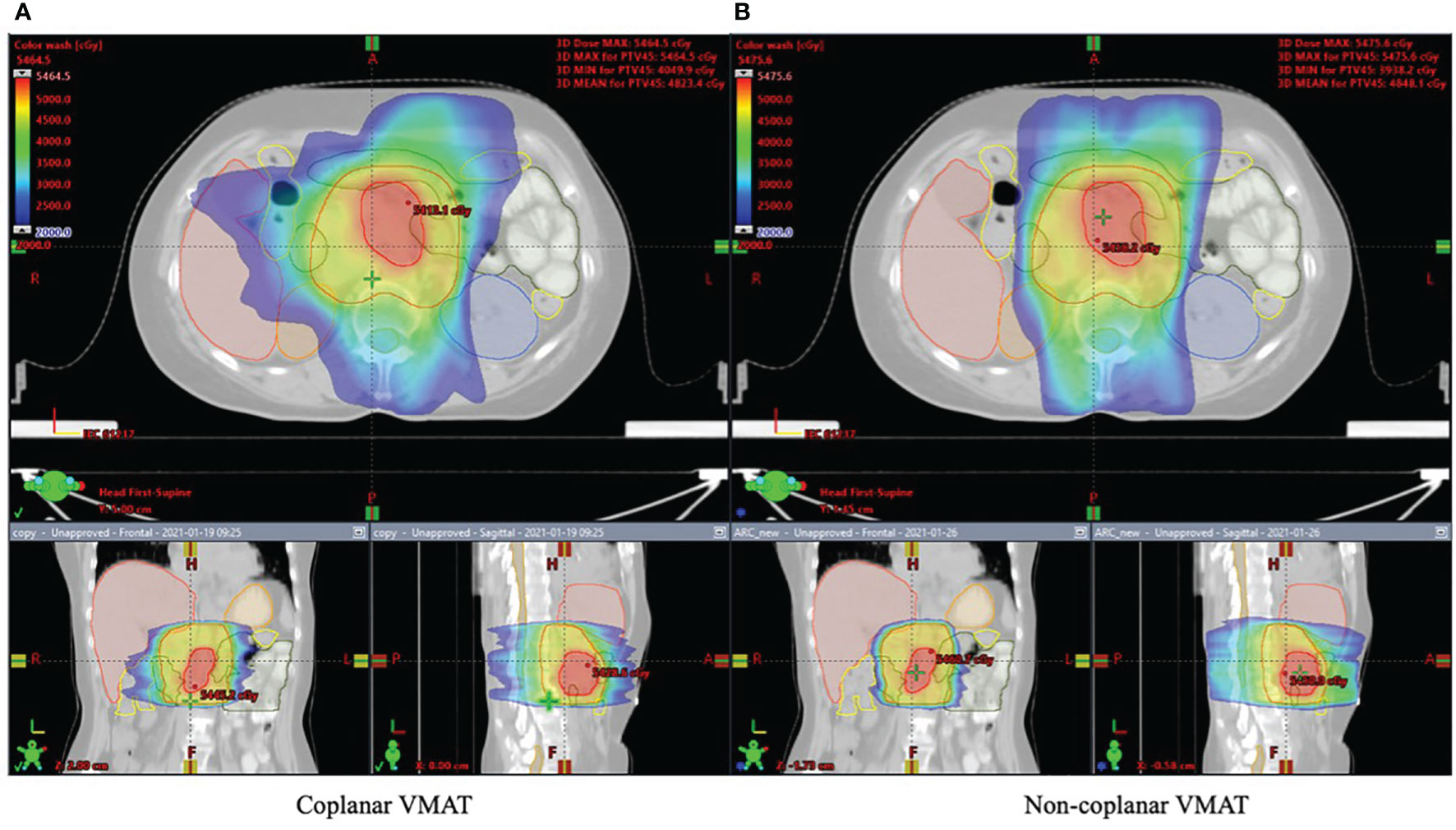

Figures 2, 3 show the dose distribution comparison of coVMAT and ncVMAT for one typical patient and the dose–volume histogram of PTV and selected OARs. As Figure 2 shows, the pancreas is centrally located and surrounded by many radiation-sensitive organs such as the stomach, bilateral kidneys, duodenum, colon, and small intestine. From the dose distribution, we can see that the ncVMAT plan has a better sparing of the liver, small intestine, and colon due to the additional freedom of couch rotation. The dose–volume histogram comparison also shows that ncVMAT resulted in a significant dose reduction to selected OARs with comparable target coverage to the coVMAT plan. In such a case, the improved OAR sparing can be utilized to increase the amount of dose that can be delivered to the tumor limited by normal tissue toxicity, thus improving the local control.

Figure 2 Dose distribution for one typical patient shown in axial, coronal, and sagittal views: (A) coplanar VMAT and (B) non-coplanar VMAT plan.

The average MUs for coVMAT and ncVMAT plans were 585 ± 117 and 540 ± 80 MU. The average number of subarcs for each non-coplanar plan is 10. The minimum and maximum numbers of subarcs are 8 and 12.

Discussion

In the radiotherapy of pancreatic cancer, a hypofractionated regimen that delivers much higher BED to the tumor shows better local control compared with the conventionally fractionated regimen. However, the implementation of hypofractionated radiotherapy in pancreatic cancer is usually associated with excess normal tissue toxicity which limited the amount of radiation dose that can be delivered to the tumor. Thus, OAR sparing is of great significance in order to improve tumor control while reducing normal tissue toxicity. In this study, non-coplanar VMAT was investigated for its ability of OAR dose sparing in locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients by using a trajectory optimization approach. Due to the complexity of non-coplanar VMAT trajectory optimization, beam oreientations were selected mannually in previous studies. The quality of non-coplanar plan using manually selected beam direction largely relies on the experience of the treatment planner. This study investigates the organ at risk sparing in locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients using the non-coplanar VMAT technique. Compared with previous studies which manually select the beam orientation, the non-coplanar trajectories in our study were selected automatically using the trajectory optimization algorithm. Compared with automatic optimization methods such as the VMAT+ technique, our method is simple and easy to implement because the fluence map optimization is decoupled from beam orientation optimization. Firstly, a cost map which represents the ray–OAR overlap was produced through ray-tracing simulation for each patient. Then, a shortest pathfinding algorithm was utilized to find the minimal cost trajectory through the cost map. The result in non-coplanar trajectory was a continuous path. Due to restriction of the planning and delivery system, the linac gantry and couch cannot rotate simultaneously, and the non-coplanar VMAT trajectory was divided into several subarcs with static couch rotation.

For OARs, both the coVMAT and ncVMAT plans met the dose constraints suggested by RTOG 0848. However, ncVMAT significantly decreased the dose to the stomach, bilateral kidneys, duodenum, and spinal cord, compared with coVMAT. The stomach Dmax, Dmean, and D15%; the bilateral kidneys Dmean; the duodenum Dmean and D15%; and the spinal cord Dmax were all decreased with ncVMAT. An overall lower mean dose to the small intestine and colon was also achieved with ncVMAT.

As Figure 4 shows, the non-coplanar VMAT significantly improved the mean coverage of PTV50 Gy, PTV54 Gy, PTV60 Gy, and PTV70 Gy. This could potentially improve tumor control. Improved tumor control also means improved survival. The mean conformity index of PTV45 Gy, PTV54 Gy, and PTV70 Gy was also improved which indicated that ncVMAT may have a better sparing of normal tissues.

Although the MU for ncVMAT plans was slightly lower than the coVMAT plans, the treatment delivery time of ncVMAT plans can be longer than coVMAT plans due to the extra couch rotation between multiple arcs. However, the treatment time of ncVMAT plans can be reduced by implementing automatic couch rotation.

There are several limitations of this study: 1) OARs were equally weighted when generating the cost map. A customized weighting factor can be applied to each OAR according to their clinically relevant importance to generate better sparing of a specific organ. 2) Trajectory optimization was separated from VMAT plan optimization. Due to the computation complexity, the trajectory optimization was separated from VMAT plan optimization. 3) Beams that had opposite direction were equally weighted during ray tracing. The OAR can be between the source and the PTV or behind the PTV for opposite beam directions. It is less desirable to have the OAR between the source and the PTV. In such a case, the beam orientations which have OAR between the source and the PTV should be heavily penalized. 4) Treatment time and patient comfort were sacrificed by resetting the couch to multiple arc positions.

In summary, compared with conventional coplanar VMAT, non-coplanar VMAT resulted in improved coverage for PTV50 Gy, PTV54 Gy, PTV60 Gy, and PTV70 Gy. The conformity index of PTV45 Gy, PTV54 Gy, and PTV70 Gy was also improved. For OARs, non-coplanar VMAT produced better dose sparing for the stomach, bilateral kidneys, duodenum, and spinal cord. A lower mean dose to the small intestine and colon was also achieved with non-coplanar VMAT with no significant difference for other OARs. In conclusion, non-coplanar VMAT has the potential of increasing the dose delivered to the tumor while reducing normal tissue toxicity, thus improving the local control of locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Conclusions

A trajectory optimization algorithm was developed for non-coplanar VMAT. Compared with conventional coplanar VMAT, non-coplanar VMAT resulted in improved coverage and conformity to the targets. The sparing of OARs was significantly improved in non-coplanar VMAT compared with coVMAT plans for locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All the authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the appropriateness of the material and method and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Nationl Key Research and Development Program (2021YFE0202500), Beijing Municipal Commission of Science and Technology Collaborative Innovation Project (Z201100005620012), Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2020-2Z-40919), and China International Medical Foundation (HDRS2020030206).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries, CA. Cancer J Clin (2018) 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

2. Hong J, Czito B, Willett C, Palta M. A Current Perspective on Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. OncoTargets Ther (2016) 9:6733–9. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S99826

3. Petrelli F, Comito T, Ghidini A, Torri V, Scorsetti M, Barni S. Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of 19 Trials. Int J Radiat Oncol (2017) 97:313–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.10.030

4. Reyngold M, Parikh P, Crane CH. Ablative Radiation Therapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Techniques and Results. Radiat Oncol (2019) 14:95. doi: 10.1186/s13014-019-1309-x

5. Zhong J, Patel K, Switchenko J, Cassidy RJ, Hall WA, Gillespie T, et al. Outcomes for Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Treated With Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy Versus Conventionally Fractionated Radiation: SBRT Versus Conventional RT in LAPC. Cancer (2017) 123:3486–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30706

6. Hoyer M, Roed H, Sengelov L, Traberg A, Ohlhuis L, Pedersen J, et al. Phase-II Study on Stereotactic Radiotherapy of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Carcinoma. Radiother Oncol (2005) 76:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.12.022

7. Schellenberg D, Goodman KA, Lee F, Chang S, Kuo T, Ford JM, et al. Gemcitabine Chemotherapy and Single-Fraction Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol (2008) 72:678–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.051

8. Zhang S, Yang R, Shi C, Li J, Zhuang H, Tian S, et al. Noncoplanar VMAT for Brain Metastases: A Plan Quality and Delivery Efficiency Comparison With Coplanar VMAT, IMRT, and CyberKnifeTechnol. Cancer Res Treat (2019) 18:153303381987162. doi: 10.1177/1533033819871621

9. Lee MacDonald R, Thomas CG. Dynamic Trajectory-Based Couch Motion for Improvement of Radiation Therapy Trajectories in Cranial SRT: Trajectory-Based Delivery for Cranial SRT. Med Phys (2015) 42:2317–25. doi: 10.1118/1.4917165

10. Dong P, Lee P, Ruan D, Long T, Romeijn E, Yang Y, et al. 4π Non-Coplanar Liver SBRT: A Novel Delivery Technique, Int. J Radiat Oncol (2013) 85:1360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.09.028

11. Woods K, Nguyen D, Tran A, Yu VY, Cao M, Niu T, et al. Viability of Noncoplanar VMAT for Liver SBRT Compared With Coplanar VMAT and Beam Orientation Optimized 4π IMRT. Adv Radiat Oncol (2016) 1:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2015.12.004

12. Dong P, Lee P, Ruan D, Long T, Romeijn E, Low DA, et al. 4π Noncoplanar Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Centrally Located or Larger Lung Tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol (2013) 86:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.02.002

13. Smyth G, Evans PM, Bamber JC, Mandeville HC, Welsh LC, Saran FH, et al. Non-Coplanar Trajectories to Improve Organ at Risk Sparing in Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy for Primary Brain Tumors. Radiother Oncol (2016) 121:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.07.014

14. Yu VY, Landers A, Woods K, Nguyen D, Cao M, Du D, et al. A Prospective 4π Radiation Therapy Clinical Study in Recurrent High-Grade Glioma Patients. Int J Radiat Oncol (2018) 101:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.048

15. Dunlop A, Welsh L, McQuaid D, Dean J, Gulliford S, Hansen V, et al. Brain-Sparing Methods for IMRT of Head and Neck Cancer. PloS One (2015) 10:e0120141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120141

16. Uto M, Mizowaki T, Ogura K, Hiraoka M. Non-Coplanar Volumetric-Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT) for Craniopharyngiomas Reduces Radiation Doses to the Bilateral Hippocampus: A Planning Study Comparing Dynamic Conformal Arc Therapy, Coplanar VMAT, and Non-Coplanar VMAT. Radiat Oncol (2016) 11:86. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0659-x

17. Cheung EYW, Lee KHY, Lau WTL, Lau APY, Wat PY. Non-Coplanar VMAT Plans for Postoperative Primary Brain Tumour to Reduce Dose to Hippocampus, Temporal Lobe and Cochlea: A Planning Study. BJR|Open (2021) 3:20210009. doi: 10.1259/bjro.20210009

18. Sharfo AWM, Dirkx MLP, Breedveld S, Romero AM, Heijmen BJM. VMAT Plus a Few Computer-Optimized Non-Coplanar IMRT Beams (VMAT+) Tested for Liver SBRT. Radiother Oncol (2017) 123:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.02.018

19. Chang DS, Bartlett GK, Das IJ, Cardenes HR. Beam Angle Selection for Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy (IMRT) Treatment of Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: Are Noncoplanar Beam Angles Necessary? Clin Transl Oncol (2013) 15:720–4. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0998-5

20. Osborne C, Bydder S, Ebert M, Spry N. Comparison of Non-Coplanar and Coplanar Irradiation Techniques to Treat Cancer of the Pancreas. Australas Radiol (2006) 50:463–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2006.01627.x

21. Burghelea M, Verellen D, Poels K, Hung C, Nakamura M, Dhont J, et al. Initial Characterization, Dosimetric Benchmark and Performance Validation of Dynamic Wave Arc. Radiat Oncol (2016) 11:63. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0633-7

22. Yang R, Dai J, Yang Y, Hu Y. Beam Orientation Optimization for Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy Using Mixed Integer Programming. In: Magjarevic R, Nagel JH. World Congr Med Phys Biomed Eng 2006. IFMBE Proceedings: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2007) 14:1758–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-36841-0_435

23. Amanatides J, Woo A. A Fast Voxel Traversal Algorithm for Ray Tracing. Proc EuroGraphics (1987) 87:3–10.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, non-coplanar, VMAT, trajectory optimization, treatment planning

Citation: Wang G, Wang H, Zhuang H and Yang R (2021) An Investigation of Non-Coplanar Volumetric Modulated Radiation Therapy for Locally Advanced Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer Using a Trajectory Optimization Method. Front. Oncol. 11:717634. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.717634

Received: 31 May 2021; Accepted: 26 August 2021;

Published: 17 September 2021.

Edited by:

Nicholas Hardcastle, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, AustraliaReviewed by:

Wei Zhao, Stanford University, United StatesMaarten Dirkx, Erasmus University Medical Center, Netherlands

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Wang, Zhuang and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ruijie Yang, cnVpanlhbmdAeWFob28uY29t

Gong Wang

Gong Wang Hao Wang

Hao Wang Hongqing Zhuang

Hongqing Zhuang Ruijie Yang

Ruijie Yang