Abstract

Background:

Primary endometrial yolk sac tumor (YST), as an extragonadal germ cell tumor, is an exceedingly rare malignancy characterized by high aggressiveness and poor prognosis. Currently, there is no standardized and effective treatment.

Case report:

We report a case of a 71-year-old woman with primary mixed endometrial yolk sac tumor. She presented with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. PET CT imaging suggested a uterine malignancy. Serum levels of AFP, CEA, and CA19–9 were elevated. Diagnostic endometrial biopsy pathology showed adenocarcinoma, suggestive of endometrioid carcinoma. The patient underwent laparoscopic extra-fascial total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, right pelvic lymphadenectomy, and para-aortic lymph node biopsy. Postoperative pathology revealed mixed endometrioid carcinoma, within which a component exhibited features consistent with differentiation towards yolk sac tumor (YST). Immunohistochemistry showed focal AFP positivity (+), SALL4 positivity (+), and GPC3 positivity (+). Postoperatively, she received three cycles of BEP chemotherapy (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin), followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Subsequently, she received one cycle of PEB chemotherapy. One month after completing chemotherapy, a PET-CT scan revealed a new lesion in the omentum, indicating disease recurrence. The patient opted for observation. On April 7, 2025, a follow-up chest CT showed multiple small pulmonary nodules, suggestive of metastases. Repeat AFP levels remained within the normal range. She is currently receiving combination therapy with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and pembrolizumab.

Conclusion:

Primary endometrial YST is an exceptionally rare malignant germ cell tumor. Early symptoms frequently include vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain, often accompanied by elevated serum AFP levels. Immunohistochemical markers such as AFP, GPC-3, SALL-4, and Villin are valuable for differentiating it from other entities. Advanced FIGO stage and age over 50 years were significantly associated with a higher likelihood of recurrence or death in our case and the available literature. Compared to pure endometrial YST, mixed endometrial YST occurs at an older age and appears to carry a worse prognosis. The currently most treatment for YST is radical surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, typically the BEP regimen. The role of radiotherapy in improving outcomes requires further investigation.

Introduction

Yolk sac tumor (YST) is the third most common malignant germ cell tumor, typically occurring in the gonads of young individuals (1). However, it can also arise in extragonadal sites such as the anterior mediastinum (2), retroperitoneum (3), sacrococcygeal region, and pineal gland. Mixed germ cell tumors (MGCTs), characterized by the presence of two or more malignant, primitive, or germ cell components, constitute approximately 8% of malignant germ cell tumors. The combination of YST and dysgerminoma represents the most frequent MGCT subtype (4).In female patients, extragonadal YSTs account for about 20% of all YSTs (5). Primary endometrial YSTs are even rarer. The first case of a primary endometrial endodermal sinus tumor (EST, synonymous with YST) was described by Pileri in 1980 (6). Subsequently, similar cases were reported sporadically. In 1996, Shokeir MO reported the first case of a malignant mixed Müllerian tumor (MMMT) of the uterus containing a YST component (7), representing the initial documented case of a mixed primary endometrial YST.To date, only 39 cases of primary endometrial YST have been reported in the literature. Among these, 21 cases were pure primary endometrial YSTs, while 18 cases were mixed primary endometrial YSTs. Ravishankar et al. proposed that these endometrial YSTs admixed with other somatic malignancies represent somatic-type YSTs (SDYSTs) derived from somatic malignancies (8). They typically occur in postmenopausal women and are associated with higher aggressiveness and poorer prognosis (8). Herein, we share a case of mixed primary endometrial yolk sac tumor.

Case presentation

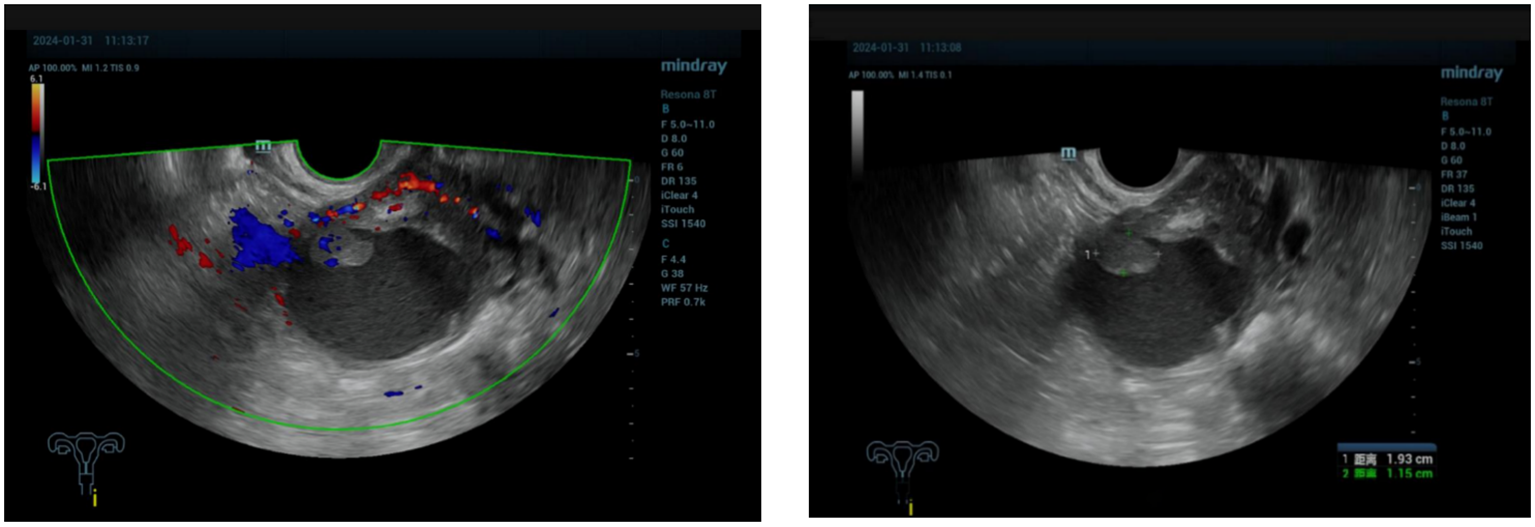

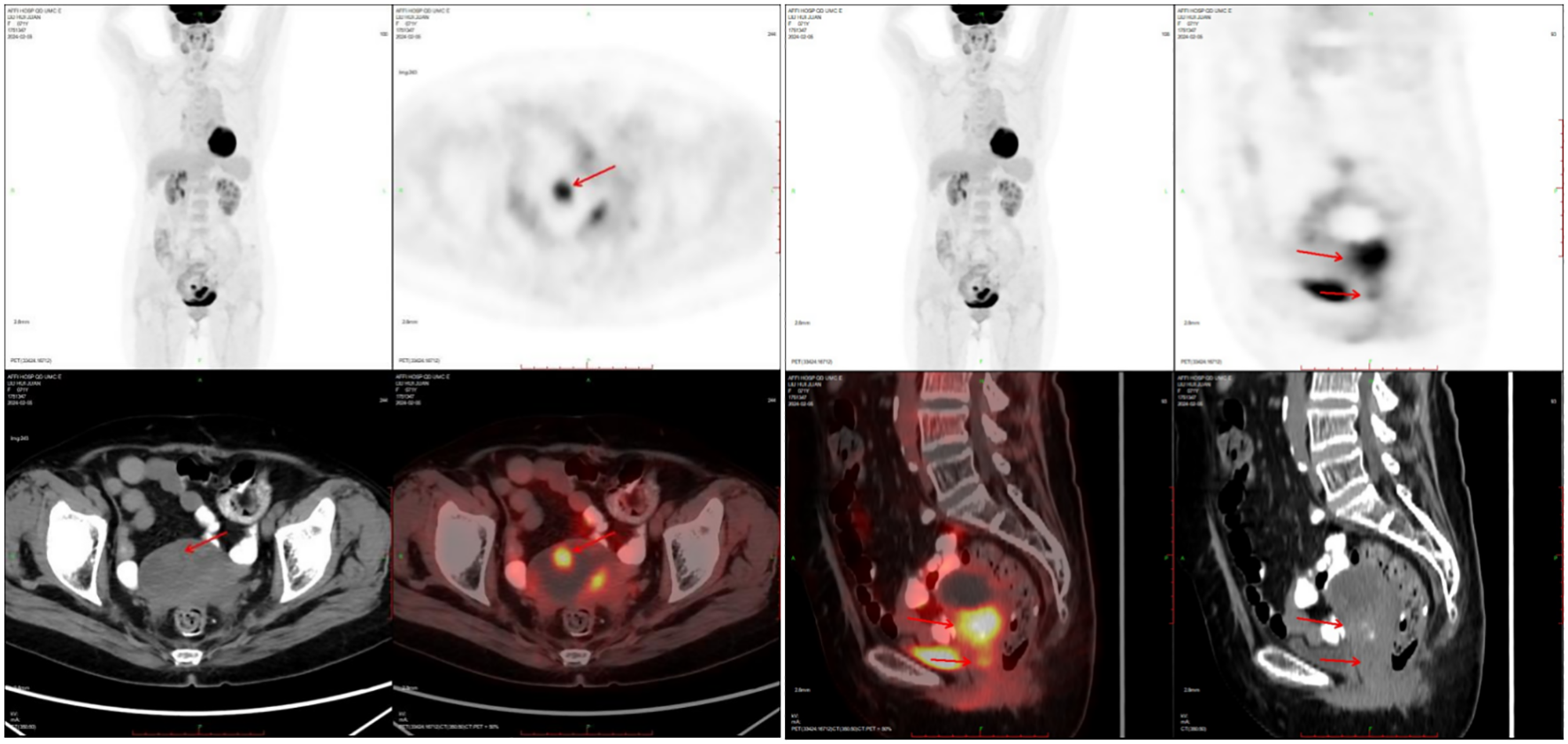

A 71-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with scant dark-red vaginal bleeding. She sought medical treatment at Qingdao University Affiliated Hospital. B-ultrasound revealed an enhanced echo in the lower uterine segment, measuring approximately 5.6×4.8×3.8 cm, raising suspicion of endometrial carcinoma (Figure 1). Diagnostic endometrial biopsy subsequently confirmed adenocarcinoma, favoring endometrioid subtype. Serum tumor markers were as follows: Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) 15.480 ng/mL (reference range: 0–7 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 8.070 ng/mL (reference range: 0–5 ng/mL), carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199) 98.280 U/mL (reference range: 0–30 U/mL), and carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) 8.080 U/mL (reference range: 0–25 U/mL). Whole-body PET/CT demonstrated an ill-defined hypermetabolic soft-tissue nodule (SUVmax ≈13.8) in the uterine corpus-cervix junction and an intracavitary protruding nodule (SUVmax ≈9.3) in the fundus, with no enlarged lymph nodes in the bilateral iliac/inguinal regions, consistent with uterine malignancy (Figure 2). Following an initial diagnosis of endometrial malignancy, the patient was admitted to our gynecology department on February 16, 2024, for surgery. Following admission, a comprehensive medical history was documented. The patient is G3P2A1. Fourteen years ago, she underwent surgical treatment for rectal cancer, followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Regular postoperative surveillance revealed no signs of recurrence. On February 20, 2024, the patient underwent laparoscopic exploration Laparoscopy revealed dense adhesions between the rectum/sigmoid colon and left pelvic wall, with fibrosis impeding vascular dissection. Frozen section pathology indicated moderately-to-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with necrosis and calcification, infiltrating nearly the full myometrial thickness. Consequently, we performed laparoscopic extrafascial total hysterectomy, bilateral adnexectomy, right pelvic lymph node dissection, para-aortic lymph node biopsy, and pelvic adhesion lysis.

Figure 1

The ultrasound showed enhanced echo in the lower segment of the uterus, ranging from 5.6×4.8×3.8cm, considering endometrial malignancy.

Figure 2

PET-CT showed nodules of soft tissue density at the base of the uterine body, protruding intrauterine, with increased metabolism, which was consistent with malignant uterine tumors.

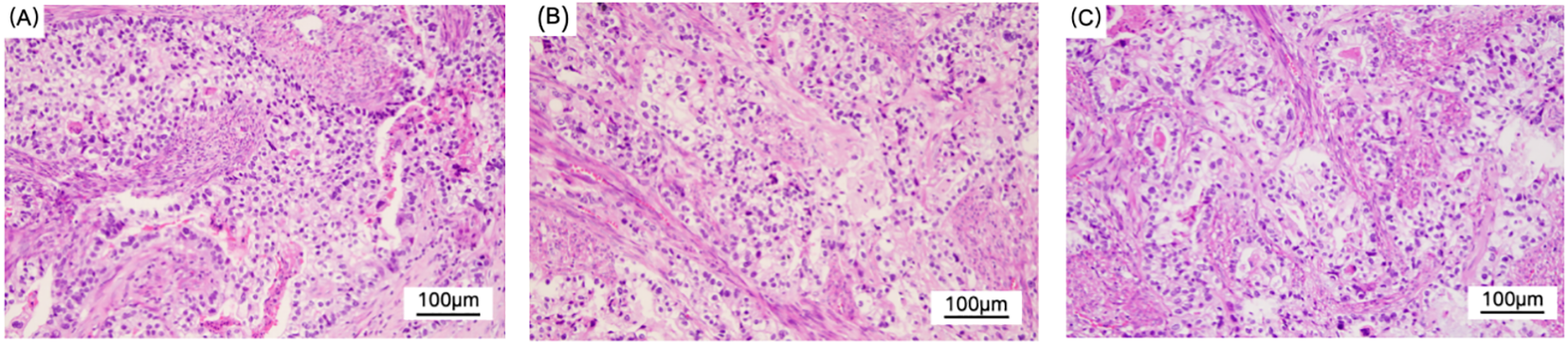

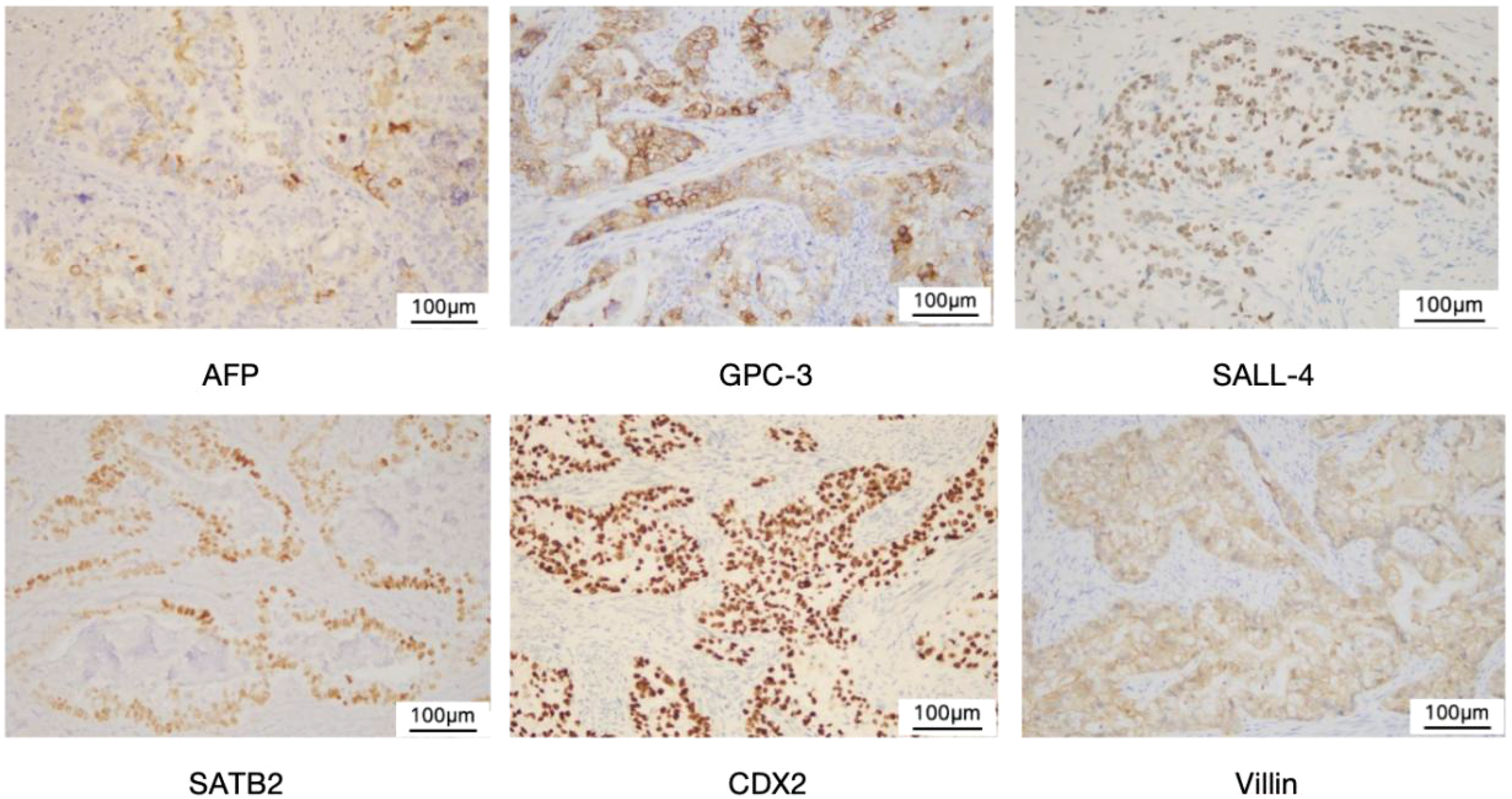

The size of the removed uterus was approximately 8 cm x 8 cm x 2 cm. A rough area measuring 6 cm x 5.5 cm was found in the uterine cavity, characterized by tough gray matter that visibly invaded the entire layer. Additionally, a mass measuring 2.5 cm x 2.1 cm was identified in the uterine cavity, exhibiting gray, white, and red sections with a slightly tough consistency. The tumor invaded the right pelvic peritoneum but did not involve the lymph nodes. According to the FIGO (International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology) staging system, this case is classified as Stage IIIB. Microscopically, the main type of cancer was adenocarcinoma. In some areas, the cytoplasm of the tumor cells was transparent, and nuclear/paranuclear vacuoles could be observed, presenting an adenoid or sieve-like arrangement. Nuclear mitotic figures were common (Figure 3). Based on the morphology and immunohistochemical results, it was considered a mixed endometrial-like carcinoma. Some of the tumors were suspected to have differentiated into yolk sac tumors, invading the entire layer of the uterine body muscle wall. Many vascular tumor thrombi could be seen, invading the cervical canal fibromuscular layer (about 1/2 layer), involving the right pelvic peritoneum and the right ovarian vessels, but not the bilateral parametrial tissues or lymph nodes. Immunohistochemistry showed AFP (foci+), SALL4 (+), GPC3 (+), SATB2 (+), CDX2 (+), Villin (+), Pax-8 (-), Vimentin (-), CK7 (in a small part +), CK20 (+), CD10 (+) (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Figure (A–C) show the light microscopic appearance of YST. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), original magnification × 200.The main type is adenocarcinoma. Some tumor cells have clear cytoplasm, and nuclear/proximal nuclear vacuoles can be observed in figure (B). They are arranged in an adenoid or sieve-like pattern, and mitotic figures are common. Considering the morphology and immunohistochemical results, it is considered a mixed endometrial-like carcinoma. Some of the tumors are suspected to have differentiated into yolk sac tumors.

Figure 4

Immunohistochemical staining of YST.Yolk sac tumor (× 200). Immunohistochemical staining showed positive for AFP,GPC-3, SALL-4, SATB2,CDX2, and Villin, respectively.

Genetic testing revealed: 1) TP53 C275Y mutation (17.5% VAF); 2) Endometrial carcinoma molecular subtype: copy-number high; 3) PD-L1 CPS = 0.3 (negative); MSI = 0.041 (MSS); TMB = 3.110 Muts/Mb (TMB-low).Postoperatively, the patient received three cycles of BEP chemotherapy: bleomycin (24 mg; 15 U/m², D1-2), etoposide (162 mg; 100 mg/m², D1-3), cisplatin (48 mg; 30 mg/m², D1-3). Due to significant adverse reactions, subsequent doses were reduced to: bleomycin (12 U/m², D1-2), etoposide (130 mg; D1-3), cisplatin (40 mg; 25 mg/m², D1-3). From 2024-05-29, she underwent 23-fraction vaginal brachytherapy (4600 cGy total, 200 cGy/fraction) with cisplatin radiosensitization (30 mg/m², D1) on 2024-06–01 and 2024-06-19, which was well-tolerated. An additional BEP cycle was administered on 2024-08-05. Serum AFP normalized before the first chemotherapy cycle and remained normal during treatment.

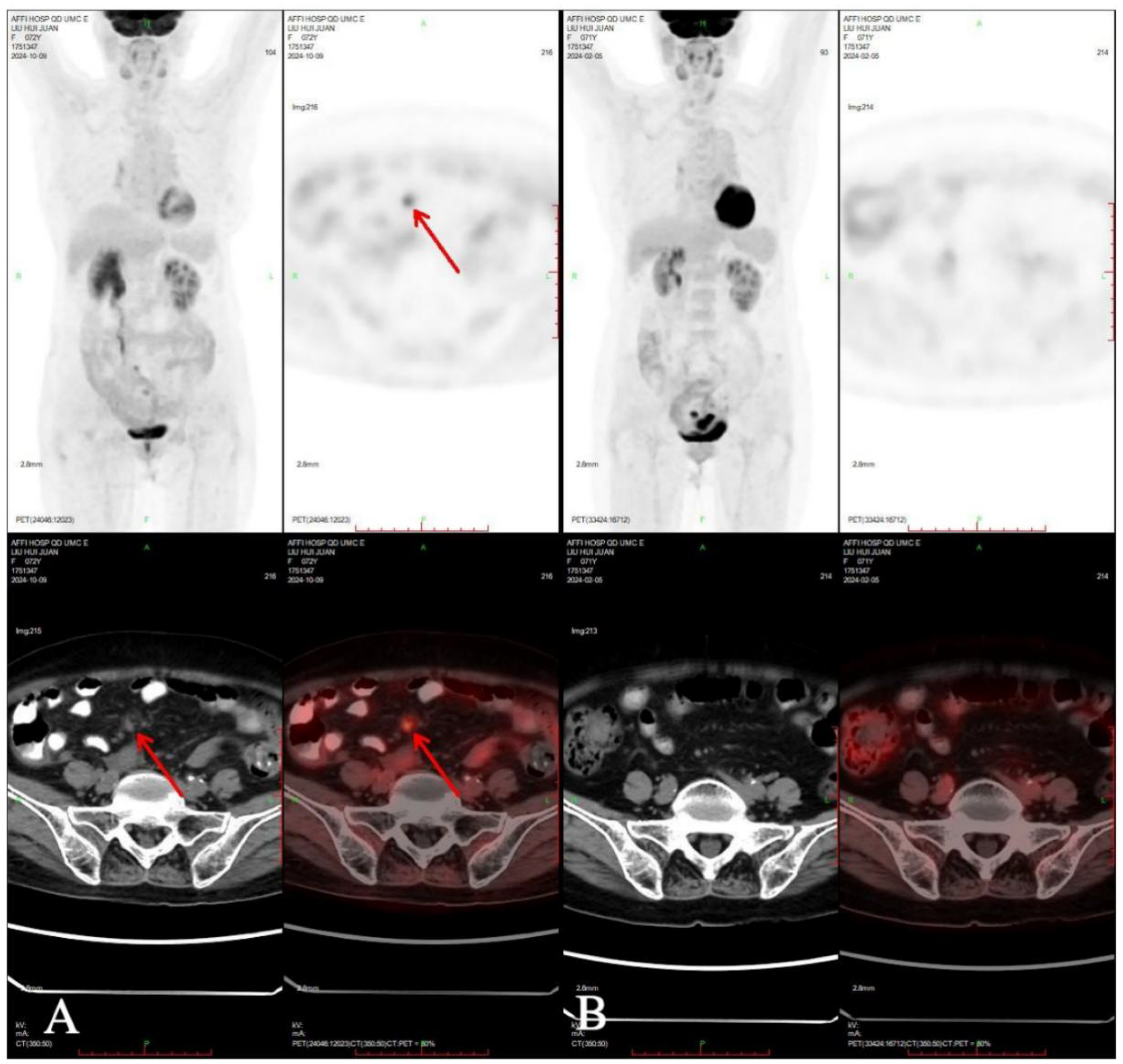

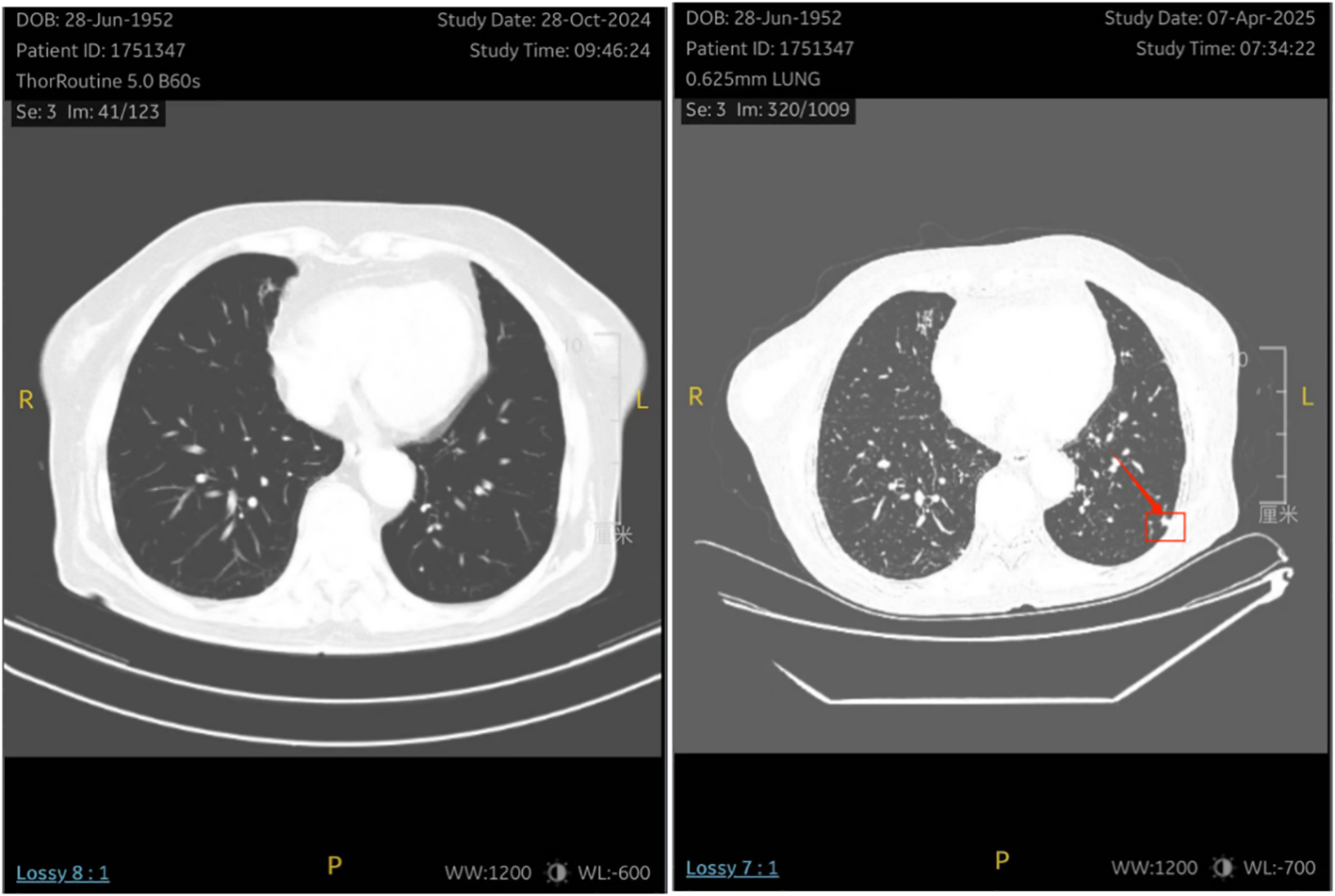

One month after chemotherapy, the patient developed dysuria. Ultrasound showed right hydronephrosis, and CT suggested possible metastatic nodules in the left pelvic peritoneum. PET/CT revealed a new hypermetabolic soft-tissue lesion (SUVmax ≈4.3) in the mesentery (Figure 5), indicating recurrence. Serum AFP was measured at 3.16 ng/mL (reference range 0–7 ng/mL). Given these examination results, the possibility of metastasis and recurrence was considered. The patient requested continued observation without treatment. On April 7, 2025, chest CT detected multiple pulmonary nodules suggestive of metastasis (Figure 6), though AFP remained normal. Multidisciplinary consultation recommended paclitaxel (240 mg/m²) + carboplatin (AUC = 5) + pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg).

Figure 5

Compared PET-CT (A) in 2024-10-09 with PET-CT (B) in 2024-02-05, new lesions were found in the omentum.

Figure 6

The patient underwent a re-examination of the chest CT on April 7, 2025, which revealed multiple small nodules in the lungs . It is considered that there might be metastatic tumors.

Discussion

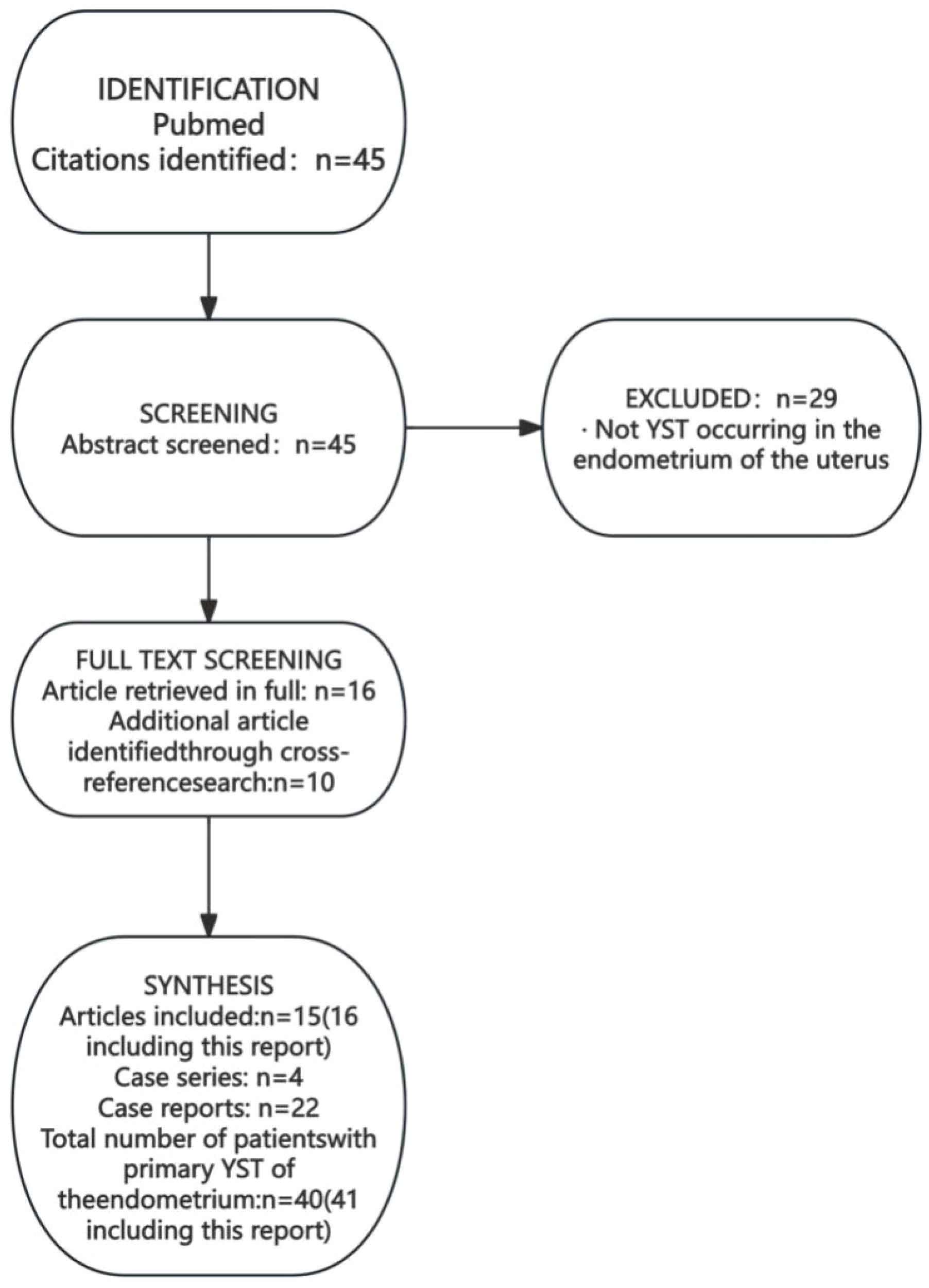

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed in October 2024 using the search string: ((“yolk sac tumor*”[tiab] OR “yolk sac tumor*”[tiab] OR “endodermal sinus tumor*”[tiab] OR “endodermal sinus tumour*”[tiab] OR “EST”[tiab] OR “YST”[tiab]) AND (“endometr*”[tiab] OR “uter*”[tiab] OR “uterine corpus”[tiab]) AND (“primary”[tiab] OR “primitive”[tiab] OR “de novo”[tiab])) AND (“case report”[pt] OR “case series”[pt] OR “case”[tiab] OR “report”[tiab] OR “review”[tiab]). A total of 45 articles were retrieved. After excluding irrelevant articles and supplementing based on cross-referenced literature, 37 cases of primary uterine endometrial YST (26 publications) were included (Figure 7) (6–31). Among them, there were 21 cases of simple uterine endometrial primary yolk sac tumor and 19 cases of mixed uterine endometrial primary yolk sac tumor. We reviewed and summarized the symptoms, pathological features, treatment modalities, and prognosis of these 37 known cases of primary endometrial yolk sac tumor (Table 1). The first case of primary endometrial yolk sac tumor was reported by Ishiguro T in 1980 (6). In 1996, Shokeir MO reported the first case of a uterine malignant Mullerian mixed tumor containing yolk sac tumor components (7), which was subsequently recognized as the first case of mixed primary endometrial yolk sac tumor. In other reported cases, the tumor components were mixed with endometrial adenocarcinoma (4/19), serous carcinoma (3/19), undifferentiated carcinoma (3/19), adenocarcinoma (3/19), clear cell carcinoma (3/19), carcinosarcoma (2/19), embryonal carcinoma (1/19), High-grade cancer (1/19) and immature teratoma (1/19). The patient in the present case had a primary endometrial yolk sac tumor complicated by endometrioid carcinoma.

Figure 7

Literature search process for cases of primary endometrial yolk sac tumor.

Table 1

| Author | Year of public | Age | Symptom | Associated component | Initial diagnosis | FIGO stage | Metastasis site | Laboratory report | Immunohistoch-emical | Surgerys | Chemo- therapy | Radiotherapy | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pileri (6) | 1980 | 28 | AVB | None | NA | IB | None | AFP 380ng/ml | AFP(+) | TAH+BSO | VAC | No | REC 2;DOD 8 |

| Ohta (9) | 1988 | 27 | AVB,IM | None | YST | IA | None | AFP 1580ng/ml | AFP(+) | TAH+BSO+OMT | VAC | No | NED>14 |

| Clement (10) | 1988 | 24 | AVB | None | NA | IV | Ovary | AFP 3600ng/ml | AFP(+),AAT(+), CEA(+) |

CISH+BSO | VAC | YES | REC,DOD 24 |

| Joseph (11) | 1990 | 42 | AVB | None | YST | IA | None | AFP18530ng/ml | AFP(+), AAT(+), CK(+),PLAP(+) | TAH+BSO | PVB | No | NED>24 |

| Spatz (12) | 1998 | 49 | AVB | None | YST | IVB | None | AFP normal | AFP(+) | TAH+BSO+PLND | NO | 45 Gy on the pelvis | NED>28 |

| Wang C (13) | 2011 | 29 | AVB | None | YST | II | None | AFP 3593.4 ng/ml | NA | Modified hysterectomy+LSO+PLND+PALND | Etoposide + carboplatin + bleomycin | No | NED>39 |

| Rossi R (14) | 2011 | 30 | AVB | None | GCT | II | None | AFP1.762 ng/ml | AFP(+) | TAH | BEP | No | NED>72 |

| Abhilasha (15) | 2014 | 31 | AVB | None | NA | IA | None | AFP 242.3 IU/ml | AFP(+),CK(+), PLAP(+),CD 117(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | NED >24 |

| Qzler (16) | 2015 | 44 | AVB | None | NA | IB | None | AFP 27522ng/ml | NA | TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | NED>6 |

| Qzler (16) | 2015 | 57 | Abd pain | None | NA | IVB | Lung,ovary, liver | AFP 29214ng/ml | NA | TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | DOD<2 |

| Damato (17) | 2016 | 63 | Postmenopausal bleeding | None | Metastatic colorectal carcinoma | IVB | Liver,lung | AFP 244.6IU/ml(PO) | AFP(+),GPC3(+),SALL4(+),Villin(+), CDX2(+), Hep Par1(+), CK20(+),CEA(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | REC,6 |

| Li JK (18) | 2017 | 38 | Menorrhea | None | NA | IIIC | Omentum | AFP 37.4 ng/ml(PO) | AFP(+),CEA(+), SALL4(+), CK18(+),CK56(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | NED>24 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 59 | AVB,uterine mass | None | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | IB | NA | NA | AFP(+),GPC3(+)SALL4(+), CDX2(+) | NA | YES | No | LTF |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 68 | AVB,uterine mass | None | Metastatic colorectal carcinoma | IV | NA | NA | AFP(+),GPC3(+), SALL4(+), CK20(+) |

YES | YES | No | DOD 14 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 61 | AVB | None | Metastatic colorectal carcinoma | IA | NA | NA | AFP (–),CK20(+), CK7(+),CDX2(+), SALL4(+) |

YES | YES | No | AWD8 |

| Lu T (19) | 2019 | 27 | AVB | None | YST | IA | NA | AFP 800 ng/ml | AFP(+),SALL4(+), CK(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | DC | No | NED> 14 |

| Lin SW (20) | 2019 | 68 | Postmenopausal bleeding | None | Serous carcinoma | II | None | AFP 133.4ng/ml(PO) | AFP (+) | TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | NED>6 |

| Ge H (21) | 2021 | 43 | AVB,Abd pain | None | EC | IA | None | AFP 1465 µg/ml | AFP(+),SALL 4(+), GPC-3(+),AE1/AE3(+),PAX 8(+) |

TAH+Bilateral salpingectomy+ Bilateral ovarian biopsy +PLND+PALND+OMT |

BEP | No | NED >15 |

| Sinha (22) | 2021 | 73 | Abd pain | None | EC | IIIA | Ovary | AFP10.5 ng/ml(PO) | AFP(+),GPC3(+), SALL 4(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+Omental biopsy | BP | No | NED>15 |

| Cheng X (23) | 2021 | 35 | AVB, prolonged menstruation |

None | NA | IA | None | AFP 9152 ng/ml | AFP(+),SALL4(+), AE1/AE3(+),CD117(+),Ki-67(80%+), Vim(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | BEP | No | NED>21 |

| Liu R (24) | 2024 | 42 | AVB | None | YST | IIIA | None | AFP1210 ng/ml | AFP(+),SALL4(+), p16(+),EMA(+), |

TAH+BSO+PLND | BEP | No | NED>13 |

| Shokeir (7) | 1996 | 64 | Abd | mixed Müllerian tumor | NA | IVB | NA | AFP15918ng/ml | NA | NA | NA | No | DOD,2.5 |

| Patsner (25) | 2001 | 59 | Postmenopausal bleeding | EC | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | IVB | Liver, diaphragm | AFP 27670 ng/ml, CA-125 250 U/ml |

AFP(+), CK(+),PLAP(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+OMT | BEP EP | 21 Gy by vaginal brachytherapy | REC,16;AWD>16 |

| Oguri (26) | 2006 | 65 | Watery discharge | carcinosarcoma | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | IIIC | Ln | AFP 2360 ng/ml, CA 199 50 U/ml, CEA 110 U/ml |

AFP(+), AE1/AE3(+), CK7(+),EMA(+) |

MRH+BSO+PLND | TP | No | NA |

| Ji M (27) | 2013 | 28 | AVB | EC | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | IV | Peritoneum,Omentum | AFP 1522 ng/ml, β-hCG 518.9 mIU/ml, CA 125 129 U/ml |

AFP(+), AE1/AE3(+), EMA(+), CA125(+),CK7(+) |

TAH+BSO+OMT+PLND+appendectomy+ partial resection of the sigmoid colon with anastomosis |

PTX,ADM,DDP,CBDCA,MTX,Act-D,VP-16,BLM,pingyangmycin,VCR,FUDR,oxaliplatin,CPA | No | REC,2;AWD,10 |

| Hu Y (28) | 2016 | 36 | AVB | CCC | CCC | IIIA | None | AFP 4597 ng/ml | AFP(+), GPC3(+),CK(+), Calretinin(+), PLAP(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT | Docetaxel+nedaplatin | No | NED >12 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 55 | AVB | Complex hyperplasia | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | II | NA | NA | AFP (–),CK20(+), CDX2(+) | YES | YES | YES | DOD16 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 77 | AVB,uterine mass | Endometrial adenocarcinoma, Undifferentiated carcinoma |

MMMT | IIIC | NA | NA | AFP(-),GPC3(+),SALL4(+),PAX-8(+) | NA | NA | NA | LTF |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 64 | AVB | adenocarcinoma,NOS | Undifferentiated carcinoma | IIIA | NA | NA | CK7(+),CDX2(+),AFP(+),GPC3(+),SALL4(+) | YES | YES | YES | DOD 23 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 87 | AVB | adenocarcinoma,NOS | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | II | NA | NA | AFP(+), GPC3(+), SALL4(+) | YES | YES | No | AWD7 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 63 | AVB | MMMT | MMMT | IIIC | NA | NA | CDX2(+), Villin(+), SALL4(+) | YES | YES | YES | NED5 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 62 | AVB | Serous carcinoma | Serous carcinoma | IB | NA | NA | AFP (–),CK7(+), GPC3(+),SALL4(+), PAX-8(+) |

YES | YES | No | AWD30 |

| Ravishankar (8) | 2017 | 77 | AVB | Serous, Clear cell, Undifferentiated carcinoma |

Serous carcinoma | IIIC | NA | NA | AFP (–),CDX2(+), GPC3(+),SALL4(+), PAX-8(+) |

YES | YES | No | AWD17 |

| Song L (29) | 2019 | 38 | AVB,menorrhea | CCC | Carcinosarcoma | IVB | None | CA125 58.5 U/ml,AFP Normal | AFP(+),SALL4(+), GPC3(+),CK18(+), CD56(+),CD15(+), p16(+),CEA(+) |

TAH+BSO+PLND+PALND+OMT+Appendectomy | BEP | No | NED>24 |

| Zhang H (30) | 2020 | 65 | Postmenopausal bleeding | embryonal carcinoma,immature teratoma | EC | 1A | None | AFP 359 ng/ml | AFP(+),OCT 3/4(+), AE1/AE3(+), GFAP(+),Ki-67(+) |

TAH+BSO | BEP | No | NED 15 |

| Mills (31) | 2024 | 74 | Postmenopausal bleeding | Carcinosarcoma | YST | IB | NA | AFP10024 ng/ml | AFP(+),GPC3(+), SALL4(+) |

YES | NA | NA | NA |

| Mills (31) | 2024 | 82 | NA | Highgrade carcinoma | Highgrade carcinoma | IB | Lung | NA | AFP(+),GPC3(+), SALL4(+),CDX2(+),CK20(+) |

YES | NA | NA | REC,8 |

| Mills (31) | 2024 | 70 | NA | SC | SC | IB | None | NA | AFP(-),SALL 4(+), GPC-3(+) |

YES | NA | NA | NED>34 |

| Mills (31) | 2024 | 59 | NA | UDC | UDC | IA | None | NA | SALL 4(+), GPC-3(+) |

YES | NA | NA | NED>48 |

| Zicheng C | – | 71 | Postmenopausal bleeding | EC | EC | IIIB | Omentum,lung | AFP 15.480ng/ml CEA 8.070ng/ml CA199 98.280U/ml |

AFP(+),SALL4(+),GPC3(+),SATB2(+)CDX2(+),Villin(+),CK7(+),CK20(+),CD10(+) | TAH+BSO+PLND | BEP+TC | CTV4600 cGy/23f by vaginal brachytherapy | REC,8;AWD>20 |

Summary of clinicopathologic features of primary endometrial YSTs.

ref, references; AVB, abnormal vaginal bleeding; Abd, abdominal; PO, postoperatively; EC, endometrioid adenocarcinoma; SC, serous carcinoma; UDC, undifferentiated carcinoma; AC, adenocarcinoma; MMMT, malignant mixed mullerian tumor; CCC, clear cell carcinoma; CISH, classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; OMT, omentectomy; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; PALND, para-aortic lymph node dissection; MRH, modified radical hysterectomy; REC, recurrence; AWD, alive with disease; DOD, died of disease; LTF, lost to follow-up; NED, no evidence sof disease; NA, not available.

Primary endometrial YST typically presents with irregular vaginal bleeding as an early symptom; some patients also experience abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, or menstrual abnormalities. The mean age at diagnosis was 53.78 years (range: 24-87). Patients with pure endometrial YST were significantly younger than those with mixed tumors (mean age 44.67 vs. 61.37 years; p = 0.005). Age >50 years was associated with higher mortality risk (p = 0.016). FIGO staging was available for 41 patients: Stage I (n=16), II (n=4), III (n=11), and IV (n=9). Pure YSTs were diagnosed at earlier stages (Stage I: 47.62% [10/21], II: 14.29% [3/21], III: 14.29% [3/21], IV: 23.81% [5/21]), while mixed YSTs presented at more advanced stages (Stage I: 15.00% [6/20], II: 10.00% [2/20], III: 40.00% [8/20], IV: 20.00% [4/20]), though this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.40).

Yolk sac tumor (YST) is an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-secreting germ cell malignancy. Serum AFP levels have high specificity in the diagnosis of yolk sac tumors, but there is no absolute threshold. When the serum AFP index exceeds 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), it is a strong indicator supporting the diagnosis (for example, when ULN = 10 ng/mL, AFP > 100 ng/mL). Most patients with yolk sac tumors have AFP levels above 1,000 ng/mL (32). However, the threshold of serum AFP levels for yolk sac tumors in different locations varies at present, and its diagnostic value needs to be comprehensively judged in combination with clinical manifestations, pathology and other examinations. Serum AFP measurement is valuable for diagnosis, monitoring treatment response, and detecting metastasis or recurrence post-therapy. Apart from two patients whose AFP levels were within the normal range before and after surgery (7, 29), the AFP levels of other patients were significantly elevated before or after surgery. Other tumor markers, such as CA199, CA125, and CEA, generally remain within the normal range but have been elevated in some cases (25–27, 29). Mingliang Ji reported a case of elevated β-hCG (β-hCG = 518.9 mIU/mL) in a patient with endometrial yolk sac tumor, which was considered to be associated with a trophoblastic tumor (27). In our case, AFP was mildly elevated (AFP = 15.47 ng/mL), along with elevated CEA (CEA = 8.070 ng/mL, reference range: 0–5 ng/mL) and CA199 (CA199 = 98.280 U/mL, reference range: 0–30 U/mL), which may be related to the presence of other malignant tumor components.

The mechanism of extragonadal YST remains controversial, but four possible mechanisms have been proposed: (1) Extragonadal YST may originate from ectopic or primordial germ cells that remain along the midline of the human spine during embryogenesis. These cells may remain in the basal layer of the endometrium for long periods, and thus, extragonadal YST is often associated with other germ cell tumors. (2) It may be caused by residual fetal tissue after an incomplete abortion. Sobis and Vandeputtr (33), Sakashita et al. (34), and others (35) have reported that fetal resection can induce intrauterine sinus tumors in rats and mice, and it is possible that YST can develop from tissue remaining after spontaneous abortion in humans. (3) Primary gonadal occult germ cell tumor metastasis. (4) Extragonadal YST may also result from abnormal differentiation of somatic cells, which may explain some mixed malignant cell tumors. Current evidence suggests that YST originating from aberrant somatic differentiation predominantly affects postmenopausal women. McNamee et al. proposed that YST in adults may develop secondarily within overgrown epithelial tumors. The YST component could arise from these epithelial precursors via neometaplasia or dedifferentiation processes. Consequently, they designated such tumors as somatic-type YST (36).

Among the 22 reported cases of pure endometrial YST, 14 patients underwent preoperative diagnostic curettage. Pathological analysis confirmed YST diagnosis in 7 of these patients. Notably, diagnostic curettage in three patients suggested metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, a potential misdiagnosis possibly attributable to the tendency of YST to differentiate toward endodermal derivatives, such as intestinal tissue. In mixed endometrial YST, the complex histological composition often impedes the identification of the YST component through preoperative curettage. Indeed, among the 19 previously reported cases, no YST component was detected preoperatively. In the case we present, preoperative curettage resulted in a diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma. The diagnosis of yolk sac tumor relies on pathological examination, and its histological patterns are notably more diverse than those of other germ cell tumors. Characteristic histological features of YST include (37): (1) loose reticular structure, (2) Schiller-Duval body (S-D body), (3) transparent corpuscles, (4) acinar, glandular, or adenoid structures of varying sizes and shapes, and (5) papillary and cystic structures. When considering SDYST, mere morphology is not sufficient for its diagnosis. Fadare’s morphological review of 626 endometrial carcinomas identified 5 cases (0.8%) exhibiting potential YST features; among these, 3 (0.5%) were confirmed as true somatic-type YST by supportive IHC (38). Consequently, histological variability and the propensity of YST to mimic somatic carcinomas can complicate diagnosis, particularly when the tumor arises in atypical locations (e.g., extragonadal) or outside the characteristic age group. Immunohistochemical analysis is crucial in these scenarios. Although AFP demonstrates high specificity and was historically considered vital for histological confirmation of YST, its diagnostic utility is limited. Focal AFP immunopositivity can occur in epithelial carcinomas, embryonal carcinomas, and immature teratomas (39). Moreover, not all YSTs exhibit positive AFP immunostaining (40), as evidenced by 5 reported AFP-negative cases. This has prompted exploration of additional diagnostic markers.SALL4, a pluripotency marker associated with germ cell differentiation, is expressed in all germ cell tumors except choriocarcinoma. It is therefore highly valuable for confirming the presence of a germ cell component but exhibits lower specificity for YST specifically (41). Glypican-3 (GPC-3) is a more sensitive marker for YST and may outperform AFP in highlighting glandular and hepatoid patterns. However, GPC-3 expression is also found in other somatic tumors, particularly clear cell carcinoma, which shares histological overlap with YST and can cause diagnostic confusion (42). When used in combination with GPC-3 and AFP, SALL4 serves as a useful diagnostic marker (43).Mills AM proposed an IHC-based diagnostic algorithm for somatic-type YST: appropriate morphology combined with coexpression of at least two YST markers (SALL4, Glypican-3, AFP), with at least one marker showing expression in ≥70% of cells within areas demonstrating morphological features of YST differentiation. Given the high specificity of AFP, its presence in any proportion of cells can permit less extensive staining for SALL4 and Glypican-3 (31).Due to its potential for differentiation toward endodermal derivatives (e.g., intestinal tissue), YST may express markers commonly associated with somatic tumors, such as cytokeratins 7 and 20, CDX2, and villin (44). Villin, expressed throughout endodermal development, was suggested by Nogales et al. (2014) for inclusion in the diagnostic IHC panel for YST (45).

Follow-up information was available for 37 out of 41 patients. The mean follow-up duration was 18.14 months (range: 2–72 months). Disease-free survival was observed in 54.05% (20/37) of patients. Adverse outcomes included recurrence in 18.92% (7/37) and disease-related death in 21.62% (8/37) within 2.5 to 24 months. Persistent disease was present in 21.62% (8/37) of patients at their last follow-up. The incidence of adverse outcomes (recurrence or death) showed a significant association with FIGO stage (p = 0.012). Adverse outcomes occurred in 77.78% (7/9) of FIGO stage IV patients, 33.33% of stage III patients, and 15.00% and 20.00% of stage I and II patients, respectively. Among the 20 patients with pure primary endometrial YST and available follow-up, 25% (5/20) experienced adverse outcomes. For the 17 patients with mixed primary endometrial YST and follow-up, the adverse outcome rate was 47.06% (8/17). Although mixed tumors suggested a trend toward worse prognosis, the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.207).

Due to the limited number of cases of primary endometrial YST, there is no consensus on treatment. Currently, surgery and postoperative adjuvant therapy are the primary treatment modalities. Of the 41 known cases, 38 patients underwent surgical treatment. Details of the surgical approach were available for 25 patients. All of these patients had a total hysterectomy, 88% underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (22/25). Two patients preserved bilateral ovaries due to fertility concerns, and one patient had her right ovary preserved. Left salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and/or anterior sacral lymphadenectomy were performed in 82% of patients (18/25). Fourteen patients also underwent greater omentectomy, one patient had appendectomy, and two patients had both procedures. Nearly half of the patients (41.46%, 17/41) were women of reproductive age. Therefore, whether endocrine function should be preserved in young women of reproductive age diagnosed with primary endometrial YST warrants further investigation. Changyu Wang et al. reported a 29-year-old woman diagnosed via dilation and curettage pathology with primary endometrial YST (13). She underwent modified hysterectomy, left salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and carboplatin. The right adnexa was preserved to maintain endocrine function. Follow-up examinations at 39 months post-diagnosis showed no abnormalities. Roberto et al. reported a 30-year-old woman with primary endometrial YST who underwent simple total hysterectomy with bilateral adnexal preservation; pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes were not resected. She received three cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) postoperatively and remained disease-free for over 6 years after treatment (14). Consequently, preserving both ovaries in young women under close monitoring appears feasible. However, more case data are needed to support this approach, as ovarian metastasis occurred in 3 of 37 reported cases with follow-up after treatment. Besides ovarian metastasis, among 24 cases with available follow-up information, metastases were also observed in the liver (3/24), lungs (2/24), omentum (2/24), lymph nodes (2/24), peritoneum (1/24), and diaphragm (1/24).

There is similarly no standardized chemotherapy regimen for primary endometrial YST. For ovarian germ cell tumors (GCT), regimens such as BEP (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin), BVP (bleomycin, vincristine, cisplatin), or VAC (vincristine, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide) are recommended. Changyu Wang et al. propose that bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin is the preferred first-line adjuvant therapy for both ovarian and endometrial YST (13). According to the 1994 Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study (GOG protocol 78), the standard recommended treatment for ovarian GCT is PEB (cisplatin, etoposide, bleomycin). This study demonstrated that three courses of adjuvant BEP following complete resection of ovarian GCT nearly always prevented recurrence (46). Among the 41 current patients, 33 received chemotherapy, with details available for 24: 14 received BEP; one patient received BP (cisplatin, bleomycin) due to abnormal pulmonary function precluding bleomycin use (28); one received a combination of etoposide, bleomycin, and carboplatin; VAC was used in 12.5% (3/24); PVB (cisplatin, vinblastine, bleomycin) in 4.16% (1/24); and other regimens in 20.8% (5/24). Research by Wang X et al. showed that BEP chemotherapy combined with the anti-angiogenic targeted agent bevacizumab and immunotherapy (tislelizumab) achieved good efficacy in treating postoperative pelvic and lymph node metastases, offering a new approach for maintenance therapy after surgery for primary endometrial YST (47).

The literature reports 6 cases of postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy: 1 case of a 24-year-old patient with endometrial YST, who received 6 courses of VAC chemotherapy after surgery, and died of the tumor 2 years after the onset of the disease (10). Spatz (12) et al. reported a case of a 49-year-old patient who underwent hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, and only pelvic external irradiation was performed after surgery. There was no tumor recurrence after 28 months of follow-up. A 59-year-old postmenopausal woman with endometrial adenocarcinoma with YST components received vaginal internal radiotherapy, 21 Gy/1w, and the tumor recurred 1 month after the surgery (25). Ravishankar (8) et al. reported 3 patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy after surgery. One patient survived without tumor for 5 months, and 2 patients died of disease progression. Their survival periods were 16 months and 23 months respectively. In this case, radiotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy were also applied after surgery, but metastasis and recurrence occurred in the omentum 2 months after the end of chemotherapy. The prognosis of these 7 patients varied greatly. Whether postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy can improve the prognosis of patients needs further study.

Shortcomings and prospects

The reported cases of endometrial YST are very limited, whether it is simple YST or SDYST. Therefore, doctors have limited experience in diagnosing and treating such diseases. Fadare’s re-examination of 626 cases of endometrial malignancies revealed that there were 3 cases of missed diagnosis of SDYST (37). Therefore, we cannot help but suspect that there were missed diagnoses in previous cases of diagnosing endometrial malignancies. This also requires pathologists to improve their diagnostic ability for such tumors. Fadare proposed a diagnostic model combining pathological features, AFP, GPC-3, and SALL4, which provides new insights for the diagnosis of SDYST. More cases are still needed to increase the clinical treatment experience for this disease. Current issues discussed regarding the treatment plan for this disease include but are not limited to: 1. Treatment plans for young patients with simple endometrial YST to preserve fertility; 2. Whether the omentum should be removed during surgery; 3. Whether patients with endometrial YST who meet the radiotherapy indications for endometrial cancer can benefit from radiotherapy. 4. For SDYST, whether the chemotherapy plan needs to be appropriately adjusted according to the type of somatic cell tumors and the proportion of yolk sac tumors it is combined with. 5. Treatment plans after recurrence.

Conclusion

Primary endometrial yolk sac tumor is an exceedingly rare malignant germ cell tumor. Early symptoms typically include vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain, often accompanied by elevated serum AFP levels. Schiller-Duval bodies are a characteristic histopathological feature, while immunohistochemical markers (AFP, GPC-3, SALL4, Villin) aid in distinguishing it from other malignancies. The mean follow-up duration for primary endometrial YST was 18.14 months (range: 2–72 months); 54.05% (20/37) of patients showed no evidence of disease during follow-up. Advanced FIGO stage correlated with higher recurrence and mortality rates. Patients aged >50 years exhibited increased mortality risk. The prognosis of mixed (SDYST) primary endometrial YST appears poorer. The currently most primary treatment is radical surgery followed by adjuvant BEP chemotherapy (bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin). Whether radiotherapy improves prognosis remains to be determined through further investigation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization. YS: Writing – review & editing. HC: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Validation. AC: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Young RH . The yolk sac tumor: reflections on a remarkable neoplasm and two of the many intrigued by it-Gunnar Teilum and Aleksander Talerman-and the bond it formed between them. Int J Surg Pathol. (2014). 22(8):677–87. doi: 10.1177/1066896914558265

2

Goonera S Keh P Sreekanth S Recant W Talerman A . Anterior mediastinal endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumor in a female infant. Cancer. (1985) 56:1430–3. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850915)56:6<1430::AID-CNCR2820560634>3.0.CO;2-U

3

Lack E Travis W Welch K . Retoperitoneal germ cell tumors in childhood, a clinical and pathologic study of 11 cases. Cancer. (1985) 56:602–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850801)56:3<602::AID-CNCR2820560329>3.0.CO;2-D

4

Kurman RJ ML C Herrington S Yong RH . WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th edition Vol. 62. . lyon: IARC Press (2014).

5

Ramalingam P . Germ cell tumors of the ovary: A review. Semin Diagn Pathol. (2023) 40:22–36. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2022.07.004

6

Pileri S Martinelli G Serra L Bazzocchi F . Endodermal sinus tumor arising in the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. (1980) 56:391–6.

7

Shokeir MO SM N Clement PB . Malignant müllerian mixed tumor of the uterus with a prominent alpha-fetoprotein-producing component of yolk sac tumor. Mod Pathol. (1996) 9:647–51.

8

Ravishankar S Malpica A Ramalingam P Euscher ED . Yolk sac tumor in Extragonadal Pelvic sites: still a diagnostic challenge. Am J Surg Pathol. (2017) 41:1–11. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000722

9

Ohta M Sakakibara K Mizuno K Kano T Matsuzawa K Tomoda Y et al . Successful treatment of primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol. (1988) 31:357–64. doi: 10.1016/S0090-8258(88)80015-5

10

Clement PB RH Y Scully RE . Extraovarian pelvic yolk sac tumors. Cancer. (1988) 62:620–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<620::aid-cncr2820620330>3.0.co;2-p

11

Joseph MG FG F Hearn SA . Primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium. A clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. (1990) 65:297–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900115)65:2<297::aid-cncr2820650219>3.0.co;2-e

12

Spatz A Bouron D Pautier P Castaigne D Duvillard P . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. (1998) 70:285–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5036

13

Wang C Li G Xi L Gu M Ma D . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2011) 114:291–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.020

14

Rossi R Stacchiotti D MG B Calvieri G Lo Voi R . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2011) 204:e3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.014

15

Abhilasha N UD B VR P PS R Krishnappa S . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a rare entity. Indian J Cancer. (2014) 51:446. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.175315

16

Qzler A Dogan S Mamedbeyli G Rahatli S AN H Dursun P et al . Primary yolk sac tumor of endometrium: report of two cases and review of literature. J Exp Ther Oncol. (2015) 11:5–9.

17

Damato S Haldar K McCluggage WG . Primary endometrial yolk sac tumor with endodermal-intestinal differentiation masquerading as metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2016) 35:316–20. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000236

18

Li JK KX Y Zheng Y . Endometrial yolk sac tumor with Omental Metastasis. Chin Med J (Engl). (2017) 130:2007–8. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.211893

19

Lu T Qi L Ma Y Lu G Zhang X Liu P . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium: a case report and review of the literatures. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2019) 300:1177–87. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05309-3

20

Lin SW SW H SH H HS L Huang CY . Yolk sac tumor of endometrium: a case report and literature review. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. (2019) 58:846–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2019.09.020

21

Ge H Bi R . Pure primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium tends to occur at a younger age: a case report and literature analysis. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. (2021) 9:2050313X211027734. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211027734

22

Sinha R Bustamante B Truskinovsky A GL G Shih KK . Yolk sac tumor of the endometrium in a post-menopausal woman: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. (2021) 36:100748. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2021.100748

23

Cheng X Zhao Q Xu X Guo W Gu H Zhou R et al . Case Report: Extragonadal Yolk Sac tumors originating from the Endometrium and the broad ligament: a Case Series and Literature Review. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:672434. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.672434

24

Liu R Wang Y Wang X Chen X Hu J . Primary yolk sac tumor of the endometrium combined with situs inversus totalis: a case report and literature review. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:484. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-03327-1

25

Patsner B . Primary endodermal sinus tumor of the endometrium presenting as recurrent endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. (2001) 80:93–5. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6011

26

Oguri H Sumitomo R Maeda N Fukaya T Moriki T . Primary yolk sac tumor concomitant with carcinosarcoma originating from the endometrium: case report. Gynecol Oncol. (2006) 103:368–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.04.024

27

Ji M Lu Y Guo L Feng F Wan X Xiang Y . Endometrial carcinoma with yolk sac tumor-like differentiation and elevated serum β-hCG: a case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. (2013) 6:1515–22. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S51983

28

Hu Y Zeng F Xue M Xiao S . A case report for primary yolk sac tumor of endometrium. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. (2016) 41:1362–5. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2016.12.019

29

Song L Wei X Wang D Yang K Qie M Yin R et al . Primary yolk sac tumor originating from the endometrium: a case report and literature review. Med (Baltim). (2019) 98:e15144. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015144

30

Zhang H Liu F Wei J Xue D Xie Z Xu C . Mixed germ cell tumor of the Endometrium: a Case Report and Literature Review. Open Med (Wars). (2020) 15:65–70. doi: 10.1515/med-2020-0010

31

Mills AM TM J ME D KA A Ring KL . Yolk sac differentiation in endometrial carcinoma: incidence and clinicopathologic features of somatically derived yolk sac tumors versus carcinomas with nonspecific immunoexpression of yolk sac markers. Am J Surg Pathol. (2024) 48:790–802. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000002230

32

Liu J Berchuck A Backes FJ Cohen J Grisham R Leath CA et al . NCCN guidelines® Insights: ovarian cancer/fallopian tube cancer/primary peritoneal cancer, version 3.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2024) 22:512–9. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2024.0052

33

Sobis H Vandeputte M . Yolk sac-derived Malignant tumors develop in the absence of germ cells. Oncodev. Biol Med. (1983) 4:415–22.

34

Sakashita S Hirai H Nishi S Nakamura K Tsuji I . A-fetoprotein synthesis in tissue culture of human testicular tumors and an examination of experimental yolk sac tumor in rat. Cancer Res. (1976) 36:4232–6.

35

Tyagi S Sazena K Rizvi R Langley F . Foetal remnants in the uterus and their relation to other uterine heterotopia. Histopathology. (1976) 3:339–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1979.tb03015.x

36

McNamee T Damato S McCluggage WG . Yolk sac tumours of the female genital tract in older adults derive commonly from somatic epithelial neoplasms: somatically derived yolk sac tumours. Histopathology. (2016) 69:11. doi: 10.1111/his.13021

37

Feng X Li L Jiang H Jiang K Jin Y Zheng J . Dihydroartemisinin potentiates the anticancer effect of cisplatin via mTOR inhibition in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: involvement of apoptosis and autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2014) 444:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.053

38

Fadare O Shaker N Alghamdi A Ganesan R Hanley KZ Hoang LN et al . Endometrial tumors with yolk sac tumor-like morphologic patterns or immunophenotypes: an expanded appraisal. Mod Pathol. (2019) 32:1847–60. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0341-6

39

Casper S van Nagell Jr JR Powell DF Dubilier LD Donaldson ES Hanson MB et al . Immunohistochemical localization of tumor markers in epithelial ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1984) 149:154–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90188-1

40

Zirker TA Silva EG Morris M Ordóñez NG . Immunohistochemical differentiation of clear-cell carcinoma of the female genital tract and endodermal sinus tumor with the use of alpha-fetoprotein and leu-M1. Am J Clin Pathol. (1989) 91:511–4. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/91.5.511

41

Nogales FF Preda O Nicolae A . Yolk sac tumours revisited. A Rev their many faces names. Histopathology. (2012) 60:1023–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03889.x

42

Preda O Nicolae A Aneiros-Fernández J Borda A Nogales FF . Glypican 3 is a sensitive, but not a specific, marker for the diagnosis of yolk sac tumours. Histopathology. (2011) 58:312–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03735.x

43

Cao D Guo S Allan RW Molberg KH Peng Y . SALL4 is a novel sensitive and specific marker of ovarian primitive germ cell tumors and is particularly useful in distinguishing yolk sac tumor from clear cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. (2009) 33:894–904. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318198177d

44

Ramalingam P Malpica A Silva EG Gershenson DM Liu JL Deavers MT . The use of cytokeratin 7 and EMA in differentiating ovarian yolk sac tumors from endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. (2004) 28:1499–505. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138179.87957.32

45

Nogales FF Quiñonez E López-Marín L Dulcey I Preda O . A diagnostic immunohistochemical panel for yolk sac (primitive endodermal) tumours based on animmunohistochemical comparison with the human yolk sac. Histopathology. (2014) 65:51–9. doi: 10.1111/his.12373

46

Williams S Blessing JA Liao SY Ball H Hanjani P . Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. (1994) 12:701–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.701

47

Wang X Zhao S Zhao M Wang D Chen H Jiang L . Use of targeted therapy and immunotherapy for the treatment of yolk sac tumors in extragonadal pelvic sites: two case reports. Gland Surg. (2021) 10:3045–52. doi: 10.21037/gs-21-663

Summary

Keywords

yolk sac tumor, endometrial malignancy, primary endometrial yolk sac tumor, AFP, GPC-3, SALL4

Citation

Cui Z, Shan Y, Chu H and Chen A (2025) A endometrial malignant tumor with yolk sac tumor component: a case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 15:1551266. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1551266

Received

25 December 2024

Accepted

04 September 2025

Published

25 September 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Yongyan Wu, Longgang Otolaryngology Hospital, China

Reviewed by

José Manuel Lopes, Centro Hospitalar Universitário São João, Portugal

Hina Sultana, University of North Carolina System, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cui, Shan, Chu and Chen.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huijun Chu, 929719205@qq.com; Aiping Chen, chenaiping516@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.