Abstract

Background:

Sexual health is a crucial aspect of quality of life, yet it is rarely addressed by healthcare providers, especially in the context of gynecological cancer. Reports on sexual education (SE) for gynecological cancer patients are particularly scarce in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. This study aims to highlight the experiences, needs, and preferences of gynecological cancer survivors regarding SE during cancer treatment and follow-up.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among gynecologic cancer survivors at the Radiation Oncology Department of King Hussein Cancer Center. A data collection tool, developed and validated by a multidisciplinary panel of experts, was used to explore patient-provider discussions about sexuality and the factors influencing these discussions. These factors included both patient and healthcare provider-related aspects. Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square and ANOVA tests.

Results:

Sixty married patients participated in our survey, most of whom (n=27; 45%) had cervical cancer. The mean age of patients was 52, and for their sexual partners was 57. Two-thirds (66.7%) reported sexual activity (SA) as a somewhat or very important aspect of their life. While 48% reported that their partners noted a negative impact on SA after treatment, none considered stopping treatment to preserve sexual function. Although 86% felt it was important to discuss SE at clinic, and 41.7% specified that the timing of this discussion should be before treatment, only 35% of patients had had this discussion throughout their treatment and follow up. This discussion was held by the physician in 94% of instances. The most common barrier to discussion was having a male physician (71%), followed by embarrassment (60%). In our analysis, we found that physicians tend to discuss SA with patients who had younger sexual partner’s (p value = 0.024).

Conclusion:

This study is the first in the MENA region to address SE in this patient population. SE is a priority for two-thirds of the patients surveyed, yet it appears that physicians are not adequately addressing this need. Further research is needed to evaluate physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding SE to provide comprehensive, high-quality care to gynecological cancer patients.

Synopsis

This study investigates the often-neglected topic of sexual education (SE) for gynecological cancer survivors in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, focusing on their experiences, needs, and preferences. Conducted at the King Hussein Cancer Center, the cross-sectional survey involved 60 married gynecological cancer survivors, primarily cervical cancer patients, with a mean age of 52. Two-thirds considered sexual activity important, yet only 35% had discussed SE with healthcare providers during their treatment and follow-up, mostly with male physicians, a factor identified as a key barrier (71%). Despite the importance of SE to patients, provider-patient communication was limited, influenced by embarrassment and demographic factors such as the partner’s age. The findings highlight the urgent need for improved physician training and practices to address sexual health comprehensively in this population.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 100,000 patients in the United States are diagnosed with gynecological malignancies (1). In Jordan, the incidence of gynecological cancers in 2022 was 667 cases, with a 5-year prevalence of 2108 cases (2). Gynecological cancers and their treatments have a profound impact on sexual activity. These effects often begin with pre-diagnosis symptoms such as vulvar or pelvic pain, and or vaginal bleeding, which may or may not be triggered by intercourse. The psychological burden of a cancer diagnosis further exacerbates these issues and continues throughout the course of treatment—including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy—ultimately affecting the quality of life for survivors.

Previous studies conducted mainly outside the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have shown that sexual education is often inadequately addressed by healthcare providers, despite many patients’ expressing a desire for receiving related information during treatment and follow up (3, 4), another study from Jordan emphasized the lack of effective communication with physicians for sexual education (5). There is little consensus on the optimal approach and timing for delivering sexual education (6), with varying needs reported, particularly among younger patients and those in relationships (7). Gynecological cancer survivors commonly attribute their sexual dysfunction to a combination of physical (8, 9), and psycho-social concerns (10, 11). Consequently, managing sexual dysfunction following gynecological cancer therapy requires addressing both of these aspects (12, 13).

Healthcare providers should be vigilant in assessing sexual dysfunction stemming from both the disease and its treatment, applying appropriate strategies during treatment and follow-up. Delp Pub L and colleagues have outlined therapeutic strategies and recommendations tailored to the symptoms reported by survivor patients (14). Correia et al. reported that 32% of patients remained sexually active following cervical cancer treatment, though more than half of these patients experienced sexual dysfunction, as measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (15). Similarly, Fischer et al. found that women who survived ovarian cancer often experienced a poorer quality of sexual life (16).

Recognizing the limited reporting on this topic from the MENA region, particularly within the Arab world, our study aims to explore the sexual health education needs of our patients, focusing on the appropriate extent and timing of this education. Additionally, we seek to assess the burden of radiation-induced side effects among our patients and their impact on sexual activity.

Methodology

This cross-sectional study included adult gynecologic cancer survivors treated at the Radiation Oncology Department of King Hussein Cancer Center (KHCC) between 2014 and 2023. Eligible participants were those who had achieved complete remission for at least six months, were married at the time of data collection, and were at least 18 years old, ovarian cancer patients were excluded because radiation treatment is not an essential part of their treatment. Eligible patients were identified through a review of approximately 250 medical charts. Many patients were excluded from the study due to being single, divorced, or widowed. All eligible patients within the six-month timeframe were approached during follow-up clinic visits and invited to complete a questionnaire. We explained the purpose, importance, and implications of the research to each patient approached for the questionnaire, reassuring them that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential. The questionnaire was developed by the research team based on several previous studies (7, 17). Its content validity was evaluated by a multidisciplinary panel of seven experts including: two gyn-oncologist, one nurse, one psychosocial expert, one medical oncologist and two radiation oncologists.

The questionnaire was designed and prepared in Arabic, with all words and phrases carefully reviewed to ensure cultural appropriateness. It included a demographic section, along with questions exploring current sexual activity and the importance of sexual activity to the patient. The final part of the questionnaire focused on patient-provider discussions about sexual activity and the factors that might influence these discussions, whether related to the healthcare provider or the patients themselves. After finalizing the questions and receiving provisional approval, we conducted a pilot phase involving 10 patients, during which no changes were necessary.

To facilitate responses, a scale was incorporated into some questions, particularly those assessing the quality of sexual life before diagnosis, the quality of sexual life after treatment, and the current importance of sexual life to the patient. This scale ranged from 1 to 10, and responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics (Mean; SD).Adapted table from Krejcie and Morgan was considered to determine minimum needed sample, and based on a p value of 0.05 and time frame for data collection, sample size of at least 55 patients is considered to be representative (18). SPSS software was used to analyze data, descriptive statistics were done, associations were measured either by using Chi-square or One-Way ANOVA tests P <0.05 considered significant.

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board, approval number (22 KHCC 168).

Results

Patient’s demographics

Sixty patients completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 95%, with only three patients declining to participate. The mean age of the participants was 52 ± 8.52 years, while the mean age of their husbands was 57 ± 10.24 years. The majority of patients were diagnosed with cervical cancer (45%, n=27), followed by endometrial cancer (31%, n=19), vulvar cancer (20%, n=12), and other types (3.3%, n=2). Nearly all patients were treated with radiotherapy (98.3%, n=59), and most of them had multimodality treatment, including chemotherapy (70%, n=42) and surgery (65%, n=39). A significant proportion of respondents held higher educational degrees (43.4%, n=26), with 15% (n=9) currently employed and 10% retired. Detailed demographic information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1

| Variable | N, (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of participants | 60, (100) |

| Patient age (mean ± SD) | 52.13 ± 8.52 |

| Spouse age (mean ± SD) | 57.05 ± 10.24 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Cervical cancer | 27, (45) |

| Endometrial cancer | 19, (31.7) |

| Vulvar cancer | 12, (20) |

| Others | 2, (3.3) |

| Treatment received | |

| Radiotherapy | 59, (98.3) |

| Chemotherapy | 42, (70) |

| Surgery | 39, (65) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 45, (75) |

| Employed | 9, (15) |

| Retired | 6, (10) |

| Educational level | |

| Up to high school | 34, (56.6) |

| Beyond high school | 26, (43.4) |

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

SD (Standard Deviation).

Patients’ expectations, beliefs, and experience

Two thirds (N = 40) of patients believe that SA is somewhat or very important (who scored 5 and above), and these patients tend to be younger (49.98 ± 8.441) vs (56.45 ± 7.045) (p value = 0.005) and have younger husbands (53.88 ± 9.53) (p value = <0.001). Before treatment, they rated the quality of their SA as 6.95 (+/- 3.039) on a scale of 1-10; where 1 is the lowest/worst and 10 is the highest/best scores. However, after treatment, this rating decreased significantly to 3.90 (± 2.839), (p value <0.001). Those patients who reported lower quality of SA post-diagnosis also indicated SA was less important to them in general (p value = 0.007) on 1–10 scale question. Among the patients, 78.3% (N = 47) reported a change in their sexual activity post-treatment, with only 48.3% (N = 29) of these patients noting that their husbands had observed this change. Patients whose husbands noticed the change were significantly younger (49.62 ± 8.641) compared to those whose husbands did not (54.48 ± 7.822) (p value = 0.026). This observation was more prevalent among patients with vulvar cancer (p value = 0.057), particularly those experiencing vaginal stenosis after treatment (p value = 0.003). However, none of the patients considered stopping treatment to preserve SA (Table 2).

Table 2

| SA quality and importance | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Quality of SA before diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 6.95 ± 3.039 |

| Quality of SA after treatment (mean ± SD) | 3.90 ±-2.839 |

| Importance of SA currently (mean ± SD) | 5.08 ± 3.033 |

| Statement | Patients who responded (Yes) N, % |

| I noticed a change in the quality of SA | 47, (78.3) |

| My husband noticed a change in the quality of SA | 29, (48.3) |

| I thought of stopping treatment to limit its effect on SA | 0, (0) |

| I believe the effect of treatment on SA should be brought up | 53, (88.3) |

| I believe the effect of treatment on SA should be discussed before treatment | 52, (86.7) |

| I believe the effect of treatment on SA should be discussed with the medical team | 53, (88.3) |

| The effect of treatment on SA was discussed with me by the healthcare team | 21, (35.0) |

| I believe that best timing for SE discussion: | |

| At diagnosis | 15 (25) |

| Before treatment | 25 (41.7) |

| During follow up | 24 (40) |

| I prefer not to discuss SE | 8 (13.3) |

| I believe that husband should attend the discussion | 38 (63.3) |

| I believe that husband presence during discussion will negatively affect the relationship | 9 (15) |

| Side effects reported by patients: | |

| Vaginal dryness | 39 (65) |

| Vaginal stenosis | 38 (63.3) |

| Skin discoloration | 24 (40) |

| Psychological effects | 13 (21.7) |

| Post-coital bleeding | 19 (31.7) |

| Social effects | 8 (13.3) |

Patients’ expectations, beliefs, and experience.

A significant majority of patients (88.3%) believe that the impact of treatment on sexual activity (SA) and sexual education (SE) should be discussed during clinic visits, particularly by their medical team. However, only 35% (n=21) reported actually having had this discussion. When asked about the optimal timing for such discussions, 41.7% (n=25) felt it should take place before treatment that affects SA begins. Additionally, 63.3% (n=38) believed their husbands should be present during these discussions, though 15% (n=9) expressed concerns that their husband’s presence could negatively impact their relationship (Table 2).

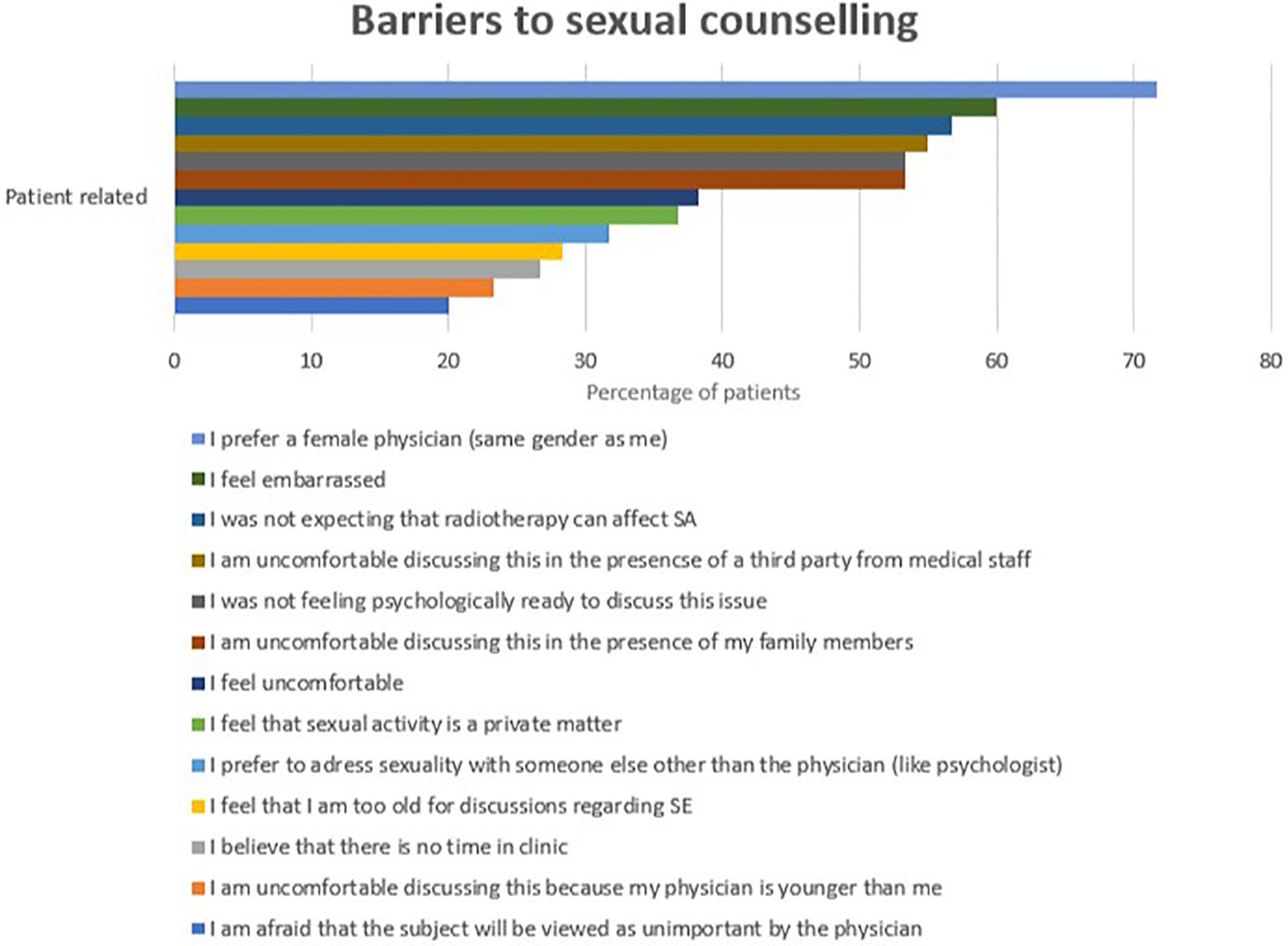

Among those who reported having SE discussions at the clinic, 35.1% (n=13) mainly discussed the effects of the tumor and treatments on SA. However, they expressed a desire to address additional topics, such as advice on preserving SA (68.3%, n=41) and understanding the impact of treatment side effects on their husbands (63.3%, n=38). Moreover, many patients showed interest in receiving brochures or written educational materials about SE (61.7%, n=37) or being referred to specialized SE clinics or group therapy (51.7%, n=31) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Patient preferences regarding SE at clinic.

The most commonly reported side effects after radiation treatment were vaginal dryness (65%, n=39) and vaginal stenosis (63.3%, n=38). However, only 38.9% (n=14) of these patients were willing to use vaginal dilators to address the condition. In terms of quality of life, psychological (34%) and social (10%) effects were the most frequently reported side effects (Table 2).

No significant associations were found between patients’ clinical or demographic characteristics and their belief in the importance of discussing sexual education (SE). However, healthcare providers were more likely to discuss SE with patients whose husbands were younger (mean age 53.05 ± 9.795) compared to those with older husbands (mean age 59.26 ± 9.920) (p-value = 0.024), (Table 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | Change in sexual life quality | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Patient Age | Mean, SD | 49.62, 8.64 N= 29 |

54.48, 7.82 N= 31 |

0.026 |

| Partner Age | Mean, SD | 54.52, 9.94 N= 29 |

59.50, 10.09 N= 31 |

0.061 |

| Partner noticed change in sexual life | Yes | 29 | 0 | <0.001 |

| No | 18 | 13 | ||

| Type of cancer | Vulvar cancer | 10 | 2 | 0.057 |

| Endometrial cancer | 7 | 12 | ||

| Cervical cancer | 11 | 16 | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| Vaginal dryness | Yes | 23 | 16 | 0.066 |

| No | 6 | 15 | ||

| Vagina stenosis | Yes | 24 | 14 | 0.009 |

| No | 5 | 17 | ||

Associations between demographic characteristics and change in sexual life quality.

Barriers to sexual counseling

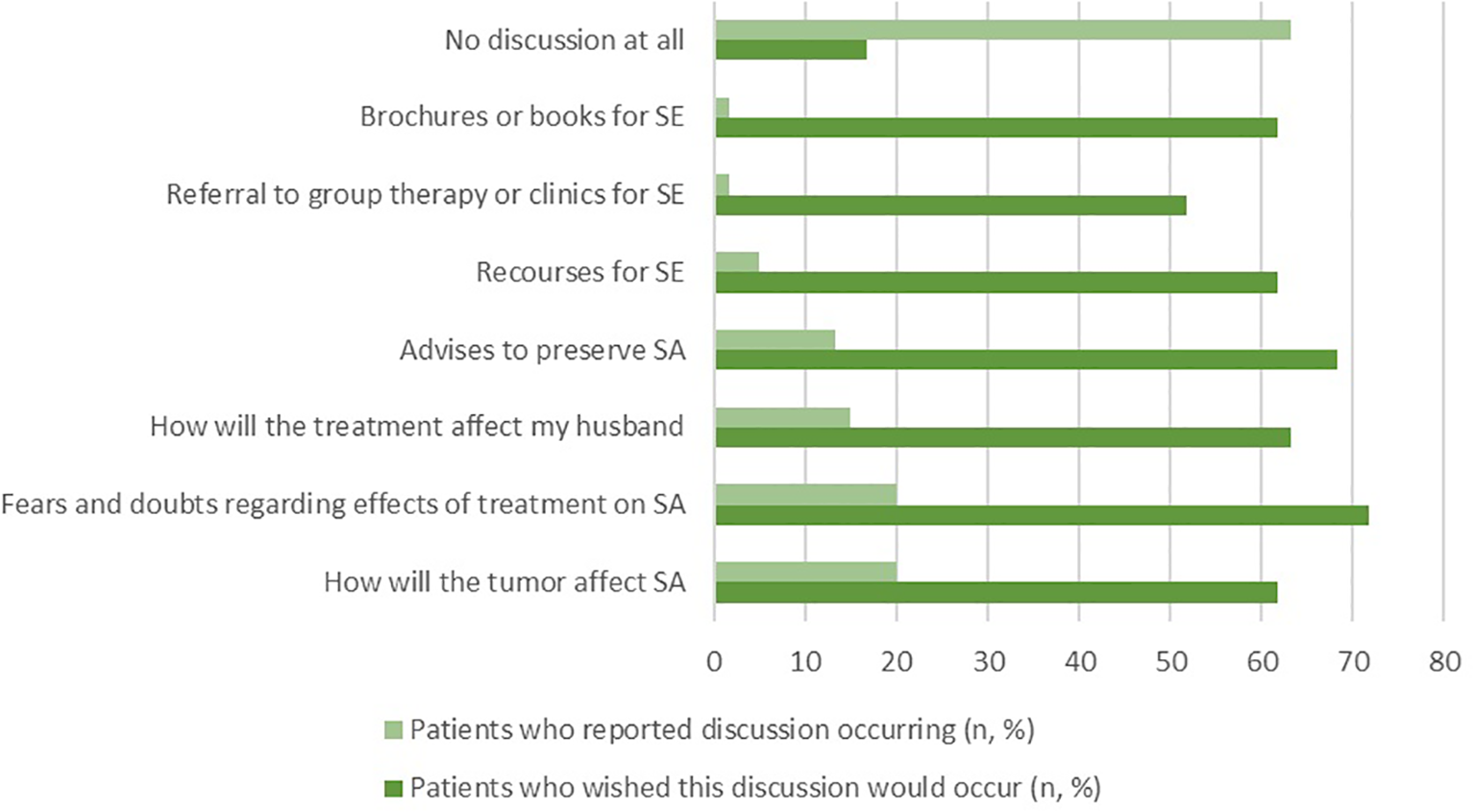

Barriers to discussing sexual activity (SA) were categorized into physician-related and patient-related factors, as reported by patients. Among physician-related barriers, the most common were the belief that the physician did not have enough time to address sexual education (SE) (33%, n=20), discomfort with discussing SE (16.7%, n=10), and perceptions of the physician lacking capability (15%, n=9) or adequate knowledge and experience in dealing with SE (8.3%). Additional barriers included patients feeling that discussing SE was outside the physician’s job description (10%) or that the physician lacked the necessary resources to support them (6.7%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Patient-related barriers into sexual counseling.

On the other hand, the most frequently reported patient-related barriers included a preference for gender concordance, with 71.7% (n=43) specifically preferring a female physician. Other common barriers included feelings of embarrassment (60%, n=36) and a lack of awareness that radiotherapy could affect SA (56.7%, n=34). Patients also cited concerns about a lack of privacy in the clinic due to the presence of third parties such as healthcare staff (55%, n=33) or family members (53.3%, n=32), psychological readiness to discuss SE (53.3%, n=32), and discomfort with the discussion (38.3%). Additionally, some patients considered SA a private matter (36.7%), preferred to discuss SE with someone other than their physician (31.7%), felt their age was inappropriate for discussing SE (28.3%), and noted a lack of time during clinic visits (26.7%). Discomfort related to the physician’s age (23.3%) and concerns that SE might be deemed unimportant by the physician (20%) were also reported (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Physician-related barriers into sexual counseling.

Discussion

Although, SA among gynecological cancer survivors was addressed before in research from the MENA region (19), this is the first study to address SE among these patients in a cohort from a comprehensive cancer center in the region. Our findings indicate that 88.3% of patients prefer to include SE and discussions about these issues as part of their healthcare.

Although SA appears to be important to at least 66% of our patients, and sexual functions after radiation treatment is usually significantly affected (20), there is a notable gap in addressing SE in clinical settings (3) which is confirmed by our study as only 35% of our patients reported occurrence of SE discussion. On the other hand, 16.7% of our patients preferred not to discuss SA in the clinic. So to ensure high-quality care for our patients, it is crucial to identify those who wish to discuss SE and to address any obstacles or barriers hindering these discussions.

Casey et al. reported that physicians use age of patients as indicator to provide SE, and they suggested to use relationship status and SA as indicators too (7). In our analysis, we found that healthcare providers were more likely to discuss sexual education (SE) when the patient’s husband was younger. This may reflect cultural norms, as sexual activity is typically restricted to marital relationships, accordingly addressing such a topic in unmarried females is considered stigma in our society. In addition this was IRB prerequisite to approve the study. Our study did not identify any specific clinical or demographic characteristics as reliable indicators for providing SE, which may be due to the limited sample size. Given that 88.3% of our patients expressed a preference for discussing SE, we recommend that SE discussions be offered to all patients.

Many of our patients (41.7%) prefers to have SE discussion before treatment that would affect SA or during follow up (40%), This is in contrast with literature, where patients usually prefer discussion during follow up, as they believe that SE discussion at time of diagnosis and treatment will be overwhelming (7). Additionally, 88.3% of our patients prefer that this discussion be led by their healthcare provider, and about half expressed interest in having access to sexual health clinics or group therapy for SE and follow-up. The most common barrier to these discussions was having a physician of male gender, which emphasizing the cultural sensitivity of this topic.

Janelle N. et al. reported that 63% of obstetrician/gynecologists at the U.S routinely assessed patients SA, but fewer than 30% assessed others aspects of SA as satisfaction or sexual problems (3). In our analysis we found that the most commonly addressed aspects were related to the tumor effects on SA (20%) and fear and doubts regarding effects of treatment on SA (20%), but patients actually expressed their desire to have a more comprehensive discussion addressing all aspect of SA and SE.

Delishaj D et al. reported that vaginal stenosis, fibrosis, discharge, bleeding, and dryness are the most common side-effects after high-dose-rate radiation treatment (21). Similarly, Barcellini et al. found that vaginal dryness, stenosis, and pain are the most frequently reported side effects post radiation treatment (22). In our analysis, we observed the same trends, with vaginal dryness (65%) and vaginal stenosis (63.3%) being the most commonly reported side effects among our patients. Notably, only 38.9% of patients with vaginal stenosis expressed a willingness to use vaginal dilators. This may be comparable to the 42% adherence rate over 12 months reported by Law et al. (23). Therefore, if our patients were given the opportunity to use vaginal dilators, they may express almost the same adherence rate.

We do not have sufficient date from traditional radiotherapy era regarding sexual side effects (24), but despite implementing of new radiotherapy modalities in gynecological malignancies treatment, as intensity modulated radiotherapy treatment (IMRT), image-guided radiotherapy treatment (IGRT) and 3-dimentional (3-D) brachytherapy treatment, most studies are reporting high prevalence of mild to moderate vaginal morbidity post radiation treatment (24, 25).

This report is limited by the small cohort size, which is probably related to topic sensitivity primarily, in addition to the lower incidence of gynecological malignancies in Jordan compared to other regions. However, to address this limitation, all eligible patients were included at our center, which resembles the only tertiary healthcare facility that serves as the main referral center for gynecological cancer cases in Jordan, given its comprehensive range of specialized treatment options. Also our patients’ sample includes a high degree of heterogeneity over social, educational and economic factors, for example, the highly educated individuals presented (43%) while urban residents presented (65%). While this may reflect the broader characteristics of our society, again a larger sample size would enhance the generalizability of the results. Additionally, our analysis did not include the perspectives of healthcare workers, such as physicians and radiotherapy clinical coordinators, which limits our understanding of the broader context needed for implementing comprehensive care. Addressing this gap will be a key focus of our future research.

Despite its limitations, this study represents an important initial step toward a more proactive approach to sexual activity (SA) and sexual education (SE) for our patients. We recommend establishing specialized sexual healthcare clinics, led by female physicians, to provide SE for gynecological cancer patients. Such clinics would address many of the barriers reported by patients, such as feelings of embarrassment and discomfort. Additionally, we suggest considering group therapy, which has been shown to effectively address sexual dysfunction in gynecological cancer patients and improve their sexual health and quality of life (12). We also recommend to understand the perspective of the healthcare providers so that a holistic solution can be advocated.

Conclusion

This is the first study in the MENA region to address sexual education (SE) in gynecological cancer patients. Our findings reveal that SE is a priority for approximately two-thirds of patients, regardless of their age or type of gynecological cancer. However, physicians are not currently providing adequate SE. Therefore, further research is needed to explore physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to SE to ensure comprehensive and high-quality care for patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by King Hussein Cancer Center - Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal Analysis, Software. SA: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IL: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Validation. IJ: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RA: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources. IM: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SS: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA-S: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Validation. MA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA-H: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Resources. FA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Siegel RL Miller KD Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442

2

400-Jordan-fact-sheet.pdf (2024). Available online at: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/400-Jordan-fact-sheet.pdf (Accessed December 2024).

3

Sobecki JN Curlin FA Rasinski KA Lindau ST . What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of united states obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. (2012) 9:1285–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x

4

Gilbert E Perz J Ussher JM . Talking about sex with health professionals: the experience of people with cancer and their partners. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2016) 25:280–93. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12216

5

Al-haddad M Alananzeh IM Green H Alomari A Fernandez R . Sexual experiences of cancer survivors: A qualitative study in Jordan. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0271264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271264

6

Stabile C Goldfarb S Baser RE Goldfrank DJ Abu-Rustum NR Barakat RR et al . Sexual health needs and educational intervention preferences for women with cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2017) 165:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4305-6

7

Hay CM Donovan HS Hartnett EG Carter J Roberge MC Campbell GB et al . Sexual health as part of gynecologic cancer care: what do patients want? Int J Gynecol Cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc. (2018) 28:1737. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001376

8

Lindau ST Abramsohn EM Baron SR Florendo J Haefner HK Jhingran A et al . Physical examination of the female cancer patient with sexual concerns: what oncologists and patients should expect from consultation with a specialist. CA Cancer J Clin. (2016) 66:241–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21337

9

Dahl AA Bentzen AG Fosså SD Hess SL Steen R Vistad I et al . Sexual inactivity during the last 4 weeks in long-term cervical cancer survivors: prevalence and associated factors. J Sex Med. (2020) 17:1359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.03.010

10

Abbott-Anderson K Kwekkeboom KL . A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. (2012) 124:477–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.030

11

Boa R Grénman S . Psychosexual health in gynecologic cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet Off Organ Int Fed Gynaecol Obstet. (2018) 143 Suppl 2:147–52. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12623

12

Bober SL Recklitis CJ Michaud AL Wright AA . Improvement in sexual function after ovarian cancer: Effects of sexual therapy and rehabilitation after treatment for ovarian cancer. Cancer. (2018) 124:176–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30976

13

Brotto LA Erskine Y Carey M Ehlen T Finlayson S Heywood M et al . A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. (2012) 125:320–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.035

14

Del Pup L Villa P Amar ID Bottoni C Scambia G . Approach to sexual dysfunction in women with cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc. (2019) 29:630–4. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000096

15

Correia RA Bonfim CVD Feitosa KMA Furtado BMASM Ferreira DKDS Santos SLD . Disfunção sexual após tratamento para o câncer do colo do útero. Rev Esc Enferm USP. (2020) 54:e03636. doi: 10.1590/s1980-220x2019029903636

16

Fischer OJ Marguerie M Brotto LA . Sexual function, quality of life, and experiences of women with ovarian cancer: A mixed-methods study. Sex Med. (2019) 7:530–9. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.07.005

17

Em K Mp N van der W Gj P H K Ad P Rc et al . Sexual concerns after (Pelvic) radiotherapy: is there any role for the radiation oncologist? J Sex Med. (2015) 12.

18

Draugalis JR Plaza CM . Best practices for survey research reports revisited: implications of target population, probability sampling, and response rate. Am J Pharm Educ. (2009) 73:142. doi: 10.5688/aj7308142

19

Shams M Coman C Fatone F Marenesi V Bernorio R Feltrin A et al . The impact of gynecologic cancer on female sexuality in Europe and MENA (Middle East and North Africa): a literature review. Sex Med Rev. (2024) 12:587–99. doi: 10.1093/sxmrev/qeae039

20

H Y O T N T W A K W I M et al . Radiotherapy- or radical surgery-induced female sexual morbidity in stages IB and II cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc. (2014) 24.

21

Delishaj D Barcellini A D’Amico R Ursino S Pasqualetti F Fumagalli IC et al . Vaginal toxicity after high-dose-rate endovaginal brachytherapy: 20 years of results. J Contemp Brachytherapy. (2018) 10:559–66. doi: 10.5114/jcb.2018.79713

22

Barcellini A Dominoni M Dal Mas F Biancuzzi H Venturini SC Gardella B et al . Sexual health dysfunction after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer: role of physical rehabilitation including pelvic floor muscle training. Front Med. (2021) 8:813352. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.813352

23

Law E Kelvin JF Thom B Riedel E Tom A Carter J et al . Prospective study of vaginal dilator use adherence and efficacy following radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. (2015) 116:149–55. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.06.018

24

Jensen PT Froeding LP . Pelvic radiotherapy and sexual function in women. Transl Androl Urol. (2015) 4:18605–205. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.04.06

25

Kirchheiner K Nout RA Tanderup K Lindegaard JC Westerveld H Haie-Meder C et al . Manifestation pattern of early-late vaginal morbidity after definitive radiation (chemo)therapy and image-guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer: an analysis from the EMBRACE study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2014) 89:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.032

Summary

Keywords

sex education, gynecological malignancy, cancer survivor, cervical cancer, quality of life

Citation

Wahbeh L, Ammar K, Abutaha S, Lataifeh I, Jaradat I, Abu-Hijlih R, Mohamad I, Salah S, Abu-Shanab SMS, Al-Sayyed M, Al-Husseini M and Abuhijla F (2025) Addressing sexual health needs in gynecological cancer survivors: insights from a tertiary cancer center in Jordan. Front. Oncol. 15:1561947. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1561947

Received

16 January 2025

Accepted

08 September 2025

Published

30 September 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Vasilios Pergialiotis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Reviewed by

Komsun Suwannarurk, Thammasat University, Thailand

Vasilios Lygizos, Alexandra General Hospital, Greece

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wahbeh, Ammar, Abutaha, Lataifeh, Jaradat, Abu-Hijlih, Mohamad, Salah, Abu-Shanab, Al-Sayyed, Al-Husseini and Abuhijla.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fawzi Abuhijla, fhijle@khcc.jo

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.