- 1Hadassah–Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel

- 2Emory Winship Cancer Institute, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 3Monash University Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia Subang Jaya Medical Centre, Subang Jaya, Malaysia

- 4Instituto de Anatomia Patológica, Rede D’Or São Luiz, São Paulo, Brazil

- 5Instituto de Pesquisa e Ensino D’Or, São Paulo, Brazil

- 6IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, Milan, Italy

- 7University of Cologne Medical Faculty, Cologne, Germany

- 8Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, United States

- 9Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Purpose: Over the years, immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) axes have substantially improved clinical outcomes for patients with various types of cancer and stages. As a result, PD-L1 is the most recognized biomarker used to guide the selection of patients for treatment with anti–PD-(L)1 therapy. To date, there are 4 regulatory agency-approved and commercially available immunohistochemistry assays used to quantify PD-L1 tumor expression, with each assay approved for use with a specific PD-(L)1 inhibitor. In this descriptive review, we concisely summarize the methodology and scoring methods of each assay, as well as some of the challenges associated with real-world use of these assay systems.

Results: Each assay system is optimized for specific therapies, with its own anti-PD-L1 antibody, protocol, scoring, and interpretation guidelines. Although the methodologies of the 4 PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay systems are similar, differences in their antibody clones, protocol conditions, instrumentation, and scoring methods limit assay interchangeability. The assays are also highly sensitive; slight deviations to the protocol can increase the risk of misclassifying the PD-(L)1 tumor status of patients. As a result, pathologists are faced with choosing which assay to perform with a limited tumor sample as well as with the challenges associated with the scoring methods and differences in regional regulatory approvals and infrastructure.

Conclusion: While the 4 approved PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assays provide clinical value, we offer pathologists suggestions to reduce the challenges associated with PD-L1 testing based on assay systems.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) have substantially improved clinical outcomes in multiple tumor types (1–9). As a result, PD-L1 is now one of the most widely used biomarkers to identify patients for treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (10). To date, there are 4 commercially available PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays that are approved for use in the United States (US Food & Drug Administration [FDA]), Europe (Conformité Européenne in vitro diagnostic [IVD] certification), and Japan (Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency [PMDA]) (11, 12): PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (Agilent Technologies) (13), PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx (Agilent Technologies) (14), PD-L1 SP263 (Ventana/Roche) (15), and PD-L1 SP142 (Ventana/Roche) (16). These assays were codeveloped alongside a specific PD-(L)1 inhibitor in early-phase clinical trials (PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx: pembrolizumab [Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA]; PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx: nivolumab [Bristol Myers Squibb]; PD-L1 SP263 assay: durvalumab [AstraZeneca]; PD-L1 SP142 assay: atezolizumab [Genentech]), resulting in their approval as companion or complementary diagnostic assays (17, 18). Therefore, each diagnostic assay is optimized for specific therapies, with its own PD-(L)1 antibody, protocol, platform, and scoring and interpretation guidelines (19). Although each PD-L1 assay is well established with a PD-(L)1 inhibitor, differences in the assay systems restrict interchangeability and warrant closer examination.

Herein, we provide a concise descriptive review of all 4 commercially available PD-L1 IVD assay systems and their approved indications. We also offer suggestions for how pathologists can navigate challenges associated with the real-world use of these assay systems.

Drug-diagnostic systems

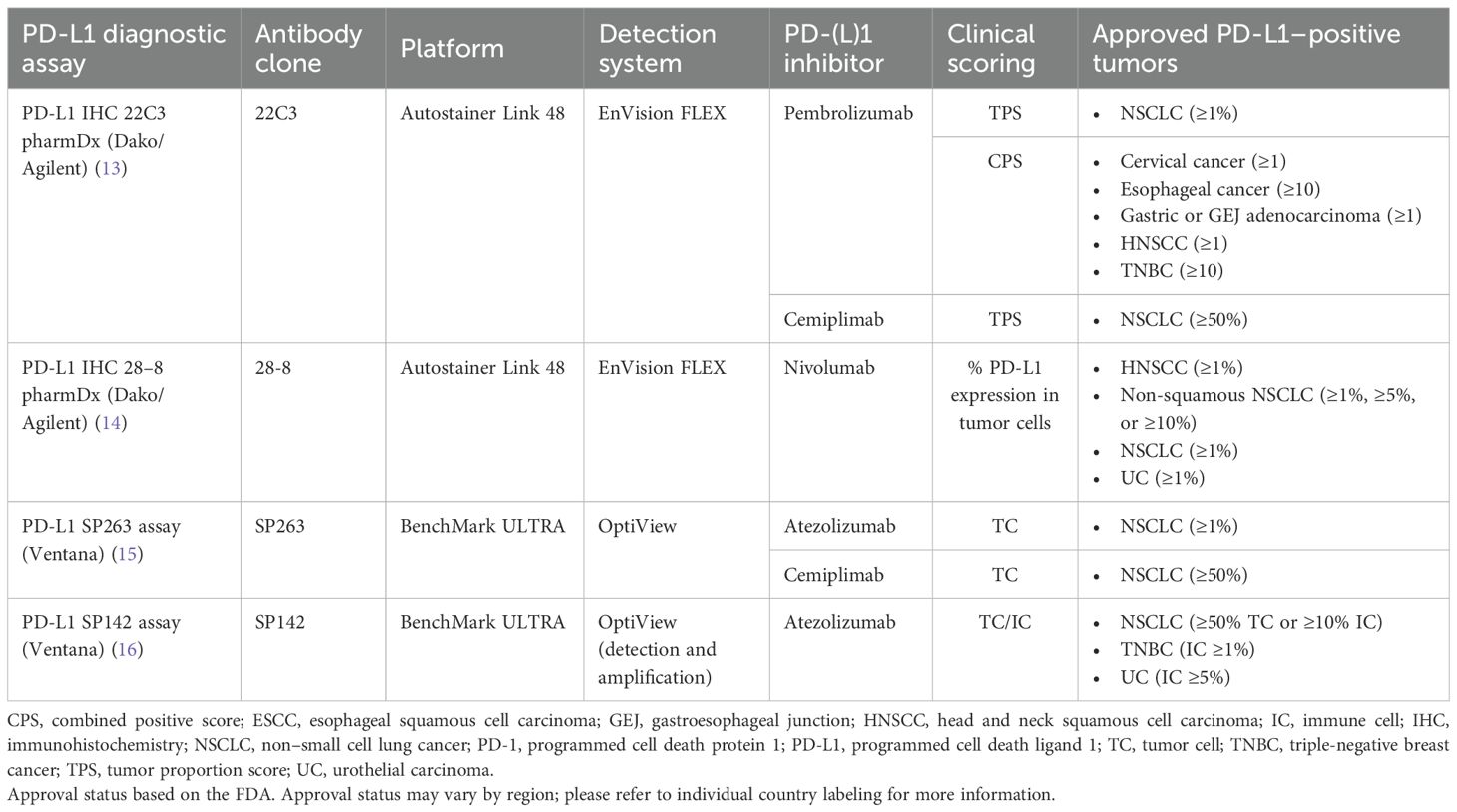

The 4 currently approved and commercially available PD-L1 diagnostic assays are summarized in Table 1 (13–16), and their regulatory US approval histories in Figure 1. Each PD-L1 diagnostic assay has been approved as a companion diagnostic or complementary assay (13–16).

Figure 1. PD-L1 diagnostic assay FDA regulatory approvals. Bolded indications represent approval as a companion diagnostic. Non-bolded indications represent approval as a complementary diagnostic. Italicized text represents withdrawn indication. Approval status may vary by region; please refer to individual country labeling for more information. AC, adenocarcinoma; GEJ, gastroesophageal junction; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; UC, urothelial carcinoma.

PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx

PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (13) was developed to detect PD-L1 expression and facilitate the safe and effective use of the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (20). This assay was first approved as a companion diagnostic by the FDA in 2015 (21, 22), followed by approvals for the same indication in Europe and Japan in 2016. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx has since been approved as a companion diagnostic for use with pembrolizumab in other tumor types, including cervical cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), and urothelial carcinoma (UC; FDA label subsequently updated to remove PD-L1 tumor expression requirement) (13). In 2021, the assay was approved by the FDA for use with another PD-1 inhibitor, cemiplimab-rwlc, in patients with NSCLC (23).

PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx

PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx (14) was developed to detect PD-L1 expression and facilitate the safe and effective use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab in patients with NSCLC (24). This assay was first granted FDA approval in 2015 as a complementary diagnostic, followed by European approval in 2016 (25). Since then, complementary diagnostic approval by the FDA has been extended to patients with HNSCC, melanoma (subsequently withdrawn), and UC (26). In 2020, the assay was approved by the FDA as a companion diagnostic for use with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in NSCLC (27); this approval was also granted in Japan and Europe (28, 29), both of which also approved its use in ESCC (29, 30), HNSCC (29, 31), gastric cancer (29, 32, 33), and melanoma (28, 29). The assay is also approved for use with nivolumab in Europe for muscle-invasive UC, GEJ adenocarcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma (34).

PD-L1 SP263 assay

The PD-L1 SP263 assay (15) was developed to detect PD-L1 expression for use with the PD-L1 inhibitor durvalumab in UC (35). The FDA first approved this assay as a complementary diagnostic for use with durvalumab in UC in 2017 (subsequently withdrawn) (35), followed by approvals as a companion diagnostic for use with atezolizumab and cemiplimab-rwlc in NSCLC (35). In addition to these US approvals, the PD-L1 SP263 assay was approved in Japan as a companion diagnostic for use with atezolizumab for NSCLC (36) and in Europe as a companion diagnostic for use with either atezolizumab or cemiplimab-rwlc in NSCLC (37, 38).

PD-L1 SP142 assay

The PD-L1 SP142 assay (16) was developed to detect PD-L1 expression for companion use with the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab in NSCLC and UC (39). This assay was first approved by the FDA as a complementary diagnostic in 2016 (40). This was followed by US approval of the assay as a companion diagnostic for use with atezolizumab for NSCLC (41), TNBC (subsequently withdrawn), and UC (subsequently withdrawn). The assay has also been approved as a companion diagnostic for use with atezolizumab in Europe (NSCLC, TNBC, and UC) and Japan (NSCLC and TNBC) (36, 42, 43).

Protocols and chemistry

Recommended IHC staining protocols of the 4 commercially available PD-L1 diagnostic assays are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Summary of protocols for commercially available PD-L1 diagnostic assays. Ab, antibody; CC1, cell conditioning 1; DAB, 3,3’-diaminobenzidine; HRP; horseradish peroxidase; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1.

PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx

PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (13, 44) is optimized for use with the PT Link Pretreatment Module (Agilent Technologies, Carpinteria, CA), Autostainer Link 48 automated staining platform (Agilent Technologies), and Dako Omnis (Agilent Technologies), and visualized with the EnVision FLEX system (Agilent Technologies). Briefly, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples are fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) for 12–72 hours, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4- to 5-µm sections, and mounted on positively charged microscope slides. Prepared tissue sections are incubated with an anti–PD-L1 22C3 mouse monoclonal primary antibody followed by a Linker antibody specific to the host species of the primary antibody. This step is followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) chromogen. The sample may then be counterstained and viewed under a light microscope for interpretation of the results. Preparation of a second slide stained with the negative control [immunoglobulin (Ig)] reagent (NCR) can help assess background staining, and positive control slides containing 2 FFPE human cell lines are provided to validate staining runs.

PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx

Similar to PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx, PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx (14) is optimized for use with the PT Link Pretreatment Module and Autostainer Link 48 automated staining platform and visualized with the EnVision FLEX system. FFPE tissue samples are fixed in 10% NBF for 24–48 hours, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4- to 5-µm sections, and mounted on positively charged microscope slides. The IHC staining procedure uses an anti–PD-L1 28–8 rabbit monoclonal primary antibody and follows a protocol very similar to PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx.

PD-L1 SP263 assay

The PD-L1 SP263 assay (15) is optimized for use with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit on the BenchMark ULTRA automated staining platform (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). FFPE tissue samples are fixed in 10% NBF for 6–72 hours, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4- to 5-µm sections, and mounted on microscope slides. Prepared tissue sections are incubated with an anti–PD-L1 SP263 rabbit monoclonal primary antibody followed by incubation with the OptiView HQ Linker (Roche Diagnostics) for 8 minutes, and then a multimer for an additional 8 minutes. The sample may then be counterstained, post-counterstained, and viewed under a light microscope. Preparation of a second slide stained with the NCR (rabbit monoclonal negative control Ig) can help assess background staining and a positive control slide of qualified normal human term placental tissue can be prepared to validate staining runs.

PD-L1 SP142 assay

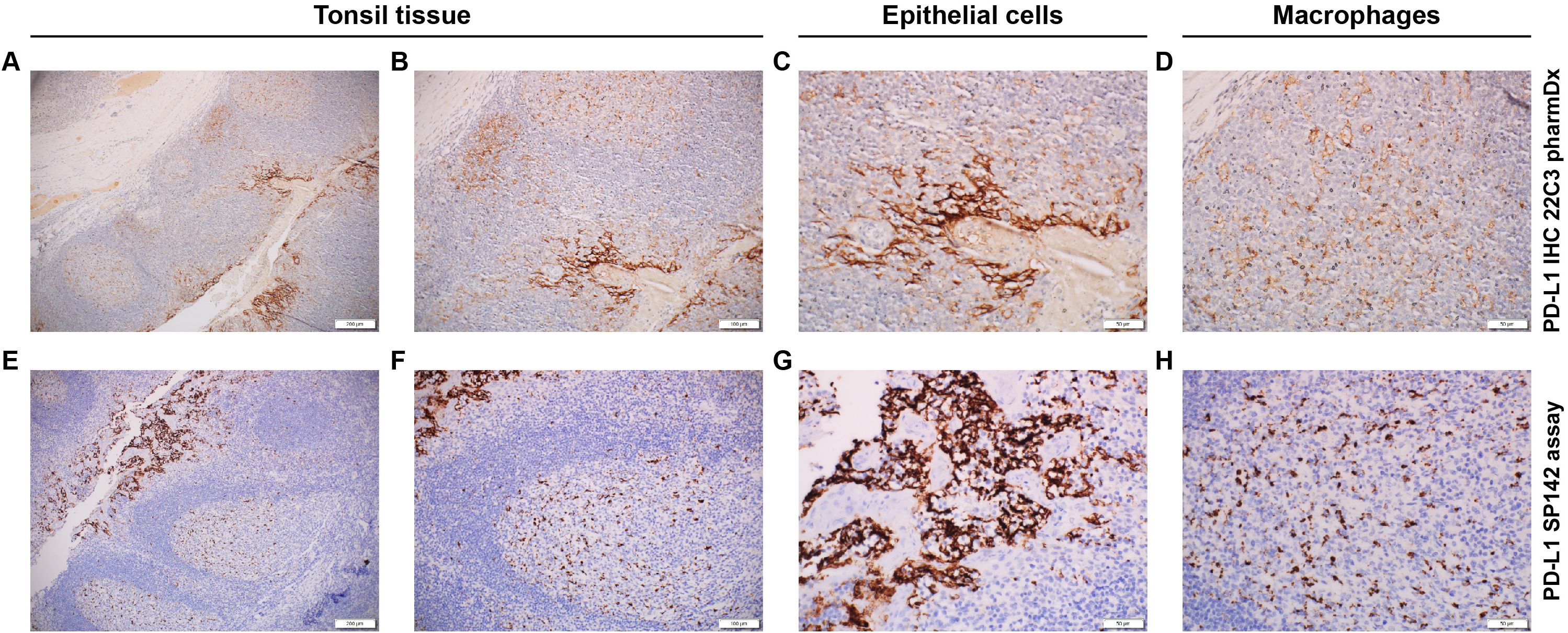

The PD-L1 SP142 assay (16) is optimized for use with the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit and OptiView Amplification Kit on BenchMark ULTRA automated staining platform. FFPE tissue samples are fixed in 10% NBF for 6–72 hours, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4-μm sections, and mounted on microscope slides. Prepared tissue sections are incubated with an anti–PD-L1 SP142 rabbit monoclonal primary antibody, followed by incubation with the OptiView HQ Linker for 8 minutes and then a multimer for an additional 8 minutes. Importantly, amplification with a hapten amplifier (for 8 minutes) and amplification multimer (for 8 minutes) is performed; this produces a dark, granular staining pattern not usually seen in the other 3 assays (Figure 3). The sample is counterstained, post-counterstained, and viewed under a light microscope. Preparation of a second slide stained with the NCR (rabbit monoclonal negative control Ig) can help assess background staining, and a positive control slide of qualified benign human tonsil tissue can be prepared to validate staining runs.

Figure 3. Immunohistochemical staining pattern of PD-L1 using different assay systems. (A–D) PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx staining. (A) Positive epithelial cells (right) with low background noise. (B) Higher magnification of the positive epithelial cells. (C) Positive epithelial cells of tonsil tissue (brown pigment). (D) Macrophages of the tonsil tissue. (E–H) PD-L1 SP142 assay staining. (E) Positive epithelial cells (left) with high background noise. (F) Higher magnification of the positive epithelial cells. (G) Positive epithelial cell of the tonsil tissue (brown pigment). (H) Macrophages of the tonsil tissue. Magnification: (A, E), ×10; (B, F), ×20; (C, D, G, H), ×40.

Scoring methods

The scoring algorithms used with the 4 commercially available PD-L1 assays estimate the percentage of PD-L1–positive tumor cells (TCs), immune cells (ICs), or both (Table 1). The tumor proportion score (TPS), percentage PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, and TC staining assessment all reflect the percentage of TCs that express PD-L1. TPS is defined as the percentage of viable TCs showing partial or complete PD-L1 membrane staining at any intensity (45). The percentage TC score is similar to the TPS and is defined as the percentage of evaluable TCs exhibiting partial linear or complete circumferential plasma membrane PD-L1 staining at any intensity (46), whereas TC staining assessment is defined as the presence of discernible PD-L1 membrane staining of any intensity in TCs (16). In contrast, the IC staining assessment is the only scoring system normalized by the cross-sectional area of the section defined as the percentage of tumor area occupied by PD-L1–expressing tumor-infiltrating ICs (lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and granulocytes) of any intensity (16). Finally, the combined positive score (CPS) is defined as the number of PD-L1-staining cells (TCs, lymphocytes, and macrophages) divided by the total number of viable TCs, multiplied by 100 (and capped at 100) (45).

Scoring methods and their cutoffs to define PD-L1 expression vary considerably by type of diagnostic assay, tumor type, and treatment strategy (Table 2). For example, all 4 PD-L1 assays received FDA approval for use as companion diagnostics with different first-line treatment strategies in NSCLC, using various cutoffs to define PD-L1 expression (47). Pembrolizumab monotherapy was the first PD-1 inhibitor therapy approved for the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic NSCLC, specifically those whose tumors have high PD-L1 expression (TPS ≥50%), assessed per PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (48). This approval was later expanded to include pembrolizumab for first-line treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC with PD-L1 expression of TPS ≥1% (48) and cemiplimab-rwlc monotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC with TPS ≥50% (49). PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx also received FDA approval for use in identifying candidates for first-line therapy with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab for metastatic NSCLC with a percentage TC expression of ≥1% (27). The PD-L1 SP142 assay was also approved for use with atezolizumab as the first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC (TC ≥50% or IC ≥10%) (41).

Practical considerations and challenges

The availability of multiple PD-L1 IHC assay systems and treatment strategies make it challenging to identify patients likely to respond to specific therapies. The Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project performed analytical and clinical comparisons of the 4 assay systems in NSCLC alone (50, 51). During phase 1, analytical comparison indicated that 3 of the 4 assays (PD-L1 22C3 pharmDx, PD-L1 28–8 pharmDx, and PD-L1 SP263) resulted in similar proportions of PD-L1–stained TCs; however, fewer PD-L1–stained TCs overall were observed for the PD-L1 SP142 assay (50). Although all 4 assays detected ICs, greater variability of IC PD-L1 staining was observed. Additionally, the PD-L1 SP142 assay resulted in staining that was more punctate and discontinuous, which may be a reflection of its unique additional amplification step (steep reaction curve) of this assay (50). Comparison of clinical performance during phase 1 demonstrated that interchanging validated cutoff thresholds between assays reduced the rate of agreement compared with the reference standard (defined as the validated cutoff and assay combination) (50). Therefore, there is potential for “misclassification” of PD-L1 status of some tumors if assays and validated cutoffs are interchanged (50).

Analytical validation of the 4 assay systems during phase 2 confirmed the findings observed during phase 1 and demonstrated strong reliability among pathologists in TC PD-L1 scoring and poor reliability in IC PD-L1 scoring (51). Notably, Tsao et al. stated that the use of different anti–PD-L1 monoclonal primary antibody clones with potential variances in epitope binding may result in distinct staining properties, thus prohibiting their interchangeability in the clinical setting (51). In support of this, a detailed mapping analysis of PD-L1 antibody clones showed that the discordance of staining between the SP142 and the SP263 assays, despite targeting an identical epitope, was likely due to subtle differences in assay protocol design rather than antibody specificity (47). Additionally, staining intensity and patterns varied by tumor type for each antibody clone (46). Notably, in selected lung cancer cases, therapy-relevant differences in PD-L1 tumor cell expression were observed depending on the antibody used (46). Finally, it is important to note that greater sensitivity of a PD-L1 IHC assay system does not imply a higher predictive value for response to drug treatment (52).

From the regulatory perspective, a companion diagnostic assay is a medical device, often an IVD, that provides information essential for the safe and effective use of a corresponding therapeutic product, while a complementary diagnostic assay identifies a biomarker-defined subset of patients who are more likely to respond to a drug, providing clinically meaningful information that aids in risk-benefit assessments for individual patients (53). In comparison with companion diagnostic assays, complementary diagnostic assays are not prerequisites for receiving a treatment (53). As a result, clinicians may be less inclined to order testing with PD-L1 complementary diagnostics, particularly in jurisdictions for which there is insufficient reimbursement and the costs are a concern. While the FDA has approved use of the 4 assay systems as complementary diagnostics in some tumor types (eg, PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx with nivolumab for HNSCC and UC), the European Medicines Agency does not recognize complementary diagnostic assays for use with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

From the infrastructure perspective, pathology laboratories may not own the Autostainer Link 48 or the BenchMark ULTRA staining platform and may therefore use another IHC staining platform or a laboratory-developed test (LDT) to assess PD-L1 expression (54). LDTs are a type of diagnostic test for which the protocol was designed and developed in the test laboratory; LDTs may also include previously approved tests that have been altered in some way (55). These assays are generally developed out of necessity due to the lack of instruments to perform the commercially available assays according to their required specifications (56). However, technical validation of LDTs must be undertaken before an assay can be considered similar to a clinically validated companion diagnostic (57). Recently, the College of American Pathologists (CAP) published updated guidelines on the analytic validation of IHC assays (58). The CAP recommends that all LDTs must be analytically validated before reporting results on patient tissue, and laboratories should achieve ≥90% overall concordance between the LDT and the comparator assay or expected results (58). Furthermore, analytic validation can be established for predictive LDTs by testing a minimum of 20 positive and negative tissue samples each, and each assay-scoring system should be separately validated with a minimum of 20 positive and negative tissue specimens each (58). Despite these guidelines, concerns about the use of LDTs still exist, including the complexity of LDT validation given variability in IHC assay analytic validation practices, the lack of transparency regarding methodology that is often not publicly available, the lack of external review, and the limited oversight/governance. Recently, the FDA announced that IVDs, including those manufactured by a laboratory, are included under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (59). The revised policy provides greater oversight to ensure the safety and effectiveness of LDTs in the US (59).

It is well known that changes in protocols, however minor, may dramatically change the IHC staining pattern. Thus, it is unsurprising that studies have shown that minor changes in IHC protocols can have a substantial impact on PD-L1–staining patterns and intensity (60). In a study evaluating the reliability and reproducibility of the 22C3 antibody with the Ventana BenchMark XT platform (Roche Diagnostics), decreasing the antibody incubation time from 32 to 16 minutes resulted in the germinal center of macrophages being mostly negative (61). Substantial variability in staining may also result from differences in the processing and embedding of tissue (Table 3) (62). Therefore, in addition to cell line controls, the selection and use of positive and negative control tissue from specimens of the same tumor type as the patient specimen in each staining run is recommended (63). However, because this practice is hard to manage clinically, positive control tissue with a complete dynamic representation of the staining can be used. For example, reactive human tonsil, normally shows strong positivity in the epithelium and light positivity of the germinal center macrophages (so called “tangible body macrophages”) (61). This control demonstrates easily the dynamic range of the PD-L1 staining and can be incorporated on each slide. We do not recommend using placenta as a positive internal control. Placenta stains very strongly for PD-L1 by IHC, and because the tissue lacks the full dynamic range of the staining, the interpreting pathologist might miss a sensitivity drift in the moderate- to low-expressing cells. Laboratories should consider including the interpretation of the internal-positive control of the patient’s tissue (macrophages, lymphocytes, etc) in the patient’s report. This is particularly important with low levels or negative PD-L1–expressing biopsies, to identify drifts in staining due to pre-analytical conditions. The identification and reporting of suboptimal internal control positive and negative cells should be considered, as this provides the treating oncologist more information about the validity and adequacy of the score.

Method of collection (by core biopsy or needle aspiration), tissue type, and tissue availability may pose challenges when evaluating PD-L1 status (64). For example, PD-L1 status is a poor predictor of treatment outcomes associated with immunotherapy in patients whose samples were obtained by needle aspiration (exfoliative cytology samples, pleural fluids especially; these occasionally are the only samples available) (64). Moreover, studies comparing core biopsy with surgical resection samples indicate that caution should be taken for specific biopsy specimens to evaluate PD-L1 status. For instance, immunostaining of decalcified bone biopsies and the impact of different decalcification solutions on antigen expression have not been validated, and additional sampling of the tumor from soft tissue may be required to minimize the risk of tumor misclassification (65–67). In contrast, some studies show comparable PD-L1 expression between cytology specimens and surgical resections (68, 69). Lau et al. showed that PD-L1 assessment on cytology specimens was comparable to histology and predicted similar treatment responses with single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic NSCLC (70). Furthermore, although there is generally good concordance in PD-L1 expression between primary and metastatic tumor samples (35, 71–73), discordance in PD-L1 expression among the origin of tissue samples can occur and should be considered (74–77). Some studies reported higher PD-L1 expression in metastatic sites in patients with breast cancer, lung cancer, or melanoma (74–77). Notably, in patients with TNBC, immunostaining with PD-L1 SP142 assay showed a lower percentage of PD-L1–positive cells in liver metastases compared with other metastatic sites (78). If tissue availability is limited, prioritization of PD-L1 IHC over other biomarkers may be required and is dependent on the tumor type.

Interpreting the results of IHC staining relies on the standard IHC assay approach of morphological evaluation (79). Assessment of PD-L1 expression by CPS is based on visual estimation of the positive expression of PD-L1 in tumor and immune cells. In samples with sparse cellularity or tumor content, where PD-L1 staining is close to the cutoff, pathologists may count tumor cells to arrive at an accurate estimation of the CPS cutoff (79). Because TPS requires visual estimation of the area covered by PD-L1–positive TCs, scoring may be subject to interobserver variability due to difficulties in estimating heterogeneous cell populations with intermixed areas of PD-L1–positive and PD-L1–negative tumor regions (79). Notably, complexities exist across tumor types, which may complicate assessment of PD-L1 expression. In HNSCC, when scoring PD-L1 expression, tumor-associated immune cells should be differentiated from chronic inflammation, and PD-L1–positive carcinoma in situ or dysplasia should be excluded when assessing invasive cancer (80). In TNBC, PD-L1 staining of neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells is not common but, when present, may be difficult to exclude from scoring using CPS (62). When scoring gastric cancer samples stained by PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx, it is important to delineate immune cells from diffuse infiltrative signet ring cells to ensure accurate calculation of CPS.

Pathologist training on the use and interpretation of PD-L1 IHC assays may improve consistency and quality in the assessment of PD-L1 status (81, 82). For example, pathologists who underwent specific reader training to score PD-L1 using TPS or CPS with PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx showed high overall interobserver agreement across several tumor types (83, 84); interobserver agreement was ≥87.3% for TPS (83) and ≥86.5% for CPS (82). An online training tool for the PD-L1 SP263 assay and the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx also resulted in high inter-reader concordance among pathologists for PD-L1 TC scoring (84). External proficiency surveys are also of value to assess practice patterns of PD-L1 IHC assay systems and identify issues and disparities (85). In the Nordic immunohistochemical Quality Control (NordiQC) external quality assessment (EQA) program for IHC, cumulative data for PD-L1 IC score revealed a mean pass rate of 88% (range, 78%-93%) for the PD-L1 SP142 assay, whereas other PD-L1 companion diagnostic assays (PD-L1 22C3 pharmDx, PD-L1 28–8 pharmDx, and PD-L1 SP263 assay) and LDTs provided a mean pass rate of 20% (range, 0%-74%) (85). A global survey of pathologists conducted by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer pathology committee highlighted marked heterogeneity in PD-L1 testing across regions and laboratories with regard to antibody clones, IHC assays, samples, turnaround times, and quality assurance measures (86).

Discussion

Despite the availability of 4 approved PD-L1 assays, inter-laboratory differences in evaluation remain a challenge. To improve this, it is recommended that pathologists utilize the available online training tools prior to validating these assays in their laboratories. Additionally, laboratories that perform PD-L1 IHC staining must continuously participate in EQA programs (eg, CAP, NordiQC, United Kingdom National External Quality Assessment Service, and European Society of Pathology) (87–90). Participating laboratories should select an EQA program that will inform the laboratory on the accuracy of the PD-L1 IHC assay protocol and the pathologists’ readout based on assessment by a central expert panel. However, participation in EQA programs is not a substitute for clinical and technical validation.

Laboratories can assess assay system proficiency by comparing their observed PD-L1 positivity and negativity rates across reported tumor types against benchmark data from tumor type–specific clinical trials. This comparison helps identify pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical processes, serving as a simple and cost-effective best practice for scoring PD-L1 using each assay system.

Complexities associated with the interpretation and scoring of PD-L1 IHC results support the rationale for developing computer-assisted PD-L1 assessment tools (eg, digital pathology, deep learning, artificial intelligence [AI]) to overcome challenges associated with manual evaluation of PD-L1 status. Recently, an AI tool was used to evaluate PD-L1 IC expression in breast cancer, substantially improving accuracy and concordance in the interpretation of PD-L1 status (91). AI-assisted methods have also been investigated in other tumor types, including NSCLC and HNSCC (92–95). However, adequate testing, validation, and training using an AI approach are required to ensure that the AI algorithm is robust, reproducible, and acceptable to support pathologists as a tool for assessment of PD-L1 expression.

In conclusion, pathologists experience multiple challenges associated with PD-L1 testing using the 4 commercially available PD-L1 IHC assay systems. Studies have shown that some of these assays are comparable but not interchangeable, highlighting differences in the entire system of detection. As a result, deviation from the protocol of a validated PD-L1 IHC assay system may increase the risk of misclassifying PD-L1 status. In addition, regulatory variability further challenges the consistent use of the PD-L1 assays, with regional differences in approvals of companion versus complementary diagnostics impacting clinical adoption. Moreover, many laboratories face constraints due to lack of approved staining platforms and infrastructure limitations, necessitating reliance on rigorously validated LDTs. While both commercially available assays and LDTs are of clinical value, pathologists should be mindful that all systems have their limitations. Therefore, laboratories and pathologists are encouraged to use well-validated, peer-reviewed LDT protocols, followed by validation of the LDTs, and to further assess, if possible, commercially available systems in different clinical settings.

Author contributions

GV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. PR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GV: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. RB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JJ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. RK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. M-ST: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Shanel Dhani, PhD, and Holly C. Cappelli, PhD, CMPP, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

Conflict of interest

GWV reports grants/research support from Roche/Genentech, Ventana Medical Systems, and Dako/Agilent Technologies; honoraria/consultation fees from Ventana, Dako/Agilent, Roche, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, and Gilead. SSB reports institutional grants/research support from NCI R01 CA281932, Caris, and Eli Lilly; honoraria/consulting fees from Agilent, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, and Roche. FAS reports honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biomarkers Academy, and BMS. GV reports consulting fees from Agilent Technologies, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Pfizer, and Roche; honoraria for lectures, presentations, speaker bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AstraZeneca, MSD, and Roche; support for meetings/travel from AstraZeneca and Roche; participation on a data safety monitoring board/advisory board AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo. RB reports honoraria for lectures and advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Illumina, Janssen, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Novartis, Qiagen, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Targos MP Inc; funding from the German Cancer Aid DKH, German Research Society DFG, the German Ministry of Research and Sciences BMBF, and the European Union UN; and is a co-founder and co-owner of Gnothis Inc. SE and Timer Therapeutics GE. SN is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, who holds stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA. JJ is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and holds stock in Illumina, GRAIL, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, and Regeneron. RK is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA, who holds stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway,NJ, USA. The funder contributed to the design, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation in collaboration with the authors; all authors had full access to the data. The funder provided financial support for editorial and writing assistance. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. New Engl J Med. (2015) 372:2521–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093

2. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:1919–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709937

3. Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Aren Frontera O, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:1277–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126

4. Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:2078–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005

5. Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, Zurawski B, Kim S-W, Carcereny Costa E, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:2020–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910231

6. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745

7. Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, Caserta C, Valderrama BP, Gurney H, et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1218–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002788

8. Forde PM, Spicer J, Lu S, Provencio M, Mitsudomi T, Awad MM, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:1973–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2202170

9. Zhou B, Zhang F, Guo W, Wang S, Li N, Qiu B, et al. Five-year follow-up of neoadjuvant PD-1 inhibitor (sintilimab) in non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. (2024) 12:e009355. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-009355

10. Duffy MJ and Crown J. Biomarkers for predicting response to immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer patients. Clin Chem. (2019) 65:1228–38. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2019.303644

11. Keppens C, Mc Dequeker E, Pauwels P, Ryska A, ‘t Hart N, and Von Der Thüsen JH. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry in non-small-cell lung cancer: unraveling differences in staining concordance and interpretation. Virchows Arch. (2021) 478:827–39. doi: 10.1007/s00428-020-02976-5

12. Motoi N and Yatabe Y. Lung cancer biomarker tests: the history and perspective in Japan. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2020) 9:879–86. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2020.03.09

13. Agilent Technologies. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx Overview (2021). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/p150013c.pdf (Accessed November 12, 2025).

14. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx Overview (2020). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/en-us/pd-l1-ihc-28-8-overview (Accessed February 17, 2025).

15. Ventana Medical Systems Inc. VENTANA PD-L1 (SP263) Assay. Available online at: https://diagnostics.roche.com/global/en/products/lab/pd-l1-sp263-ce-ivd-us-export-ventana-rtd001234.html (Accessed February 17, 2025).

16. Ventana Medical Systems. VENTANA PD-L1 (SP142) Assay package insert(2020). Available online at: https://diagnostics.roche.com/content/dam/diagnostics/us/en/products/v/ventana-pd-l1-sp142-assay/Ventana-PD-L1-SP142-PI-1019497USa.pdf (Accessed February 17, 2025).

17. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:2018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824

18. Zajac M, Boothman AM, Ben Y, Gupta A, Jin X, Mistry A, et al. Analytical validation and clinical utility of an immunohistochemical programmed death ligand-1 diagnostic assay and combined tumor and immune cell scoring algorithm for durvalumab in urothelial carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2019) 143:722–31. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0555-OA

19. Teixidó C, Vilariño N, Reyes R, and Reguart N. PD-L1 expression testing in non-small cell lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. (2018) 10:1758835918763493. doi: 10.1177/1758835918763493

20. Roach C, Zhang N, Corigliano E, Jansson M, Toland G, Ponto G, et al. Development of a companion diagnostic PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay for pembrolizumab therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2016) 24:392–7. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000408

21. US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket approval (PMA) PD-L1 IHC 22C3 PHARMDX (2015). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P150013 (Accessed November 11, 2025).

22. Hirsch FR, McElhinny A, Stanforth D, Ranger-Moore J, Jansson M, Kulangara K, et al. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assays for lung cancer: results from phase 1 of the Blueprint PD-L1 IHC Assay Comparison Project. J Thorac Oncol. (2017) 12:208–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2228

23. US Food and Drug Administration. Premarket approval (PMA). PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx (2021). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P150013S021 (Accessed November 11, 2025).

24. Phillips T, Simmons P, Inzunza HD, Cogswell J, Novotny J Jr., Taylor C, et al. Development of an automated PD-L1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay for non-small cell lung cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2015) 23:541–9. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000256

25. Jørgensen JT. Companion diagnostic assays for PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. (2016) 16:131–3. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2016.1117389

26. Dako North America, Inc. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED)(2020). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/P150025S013B.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

27. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves nivolumab plus ipilimumab for first-line mNSCLC (PD-L1 tumor expression ≥1%) (2020). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab-first-line-mnsclc-pd-l1-tumor-expression-1 (Accessed November 11, 2025).

28. Labmate Online. Dako announces expanded use of PD-L1 diagnostic test in Europe (2017). Available online at: https://www.labmate-online.com/news/laboratory-products/3/dako-agilent-pathology-solutions/dako-announces-expanded-use-of-pd-l1-diagnostic-test-in-europe/39209 (Accessed February 17, 2025).

29. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx (2024). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/en-us/product/pharmdx/pd-l1-ihc-28-8-overview (Accessed February 17, 2025).

30. Agilent Technologies Inc. Agilent companion diagnostic expands CE-IVD Mark for PD-L1IHC 28–8 pharmDx to include esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. (2022). Available online at: https://www.investor.agilent.com/news-and-events/news/news-details/2022/Agilent-Companion-Diagnostic-Expands-CE-IVD-Mark-for-PD-L1-IHC-28-8-pharmDx-to-IncludeEsophageal-Squamous-Cell-Carcinoma/default.aspx (Accessed November 11, 2025).

31. Scientific Technology News. Agilent technologies announces expanded use for PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx diagnostic in Europe (2017). Available online at: https://www.selectscience.net/article/agilent-technologies-announces-expanded-use-of-cancer-diagnostic-in-europe (Accessed November 12, 2025).

32. Agilent Technologies Inc. Agilent PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx receives CE-IVD mark as a companion diagnostic test in advanced or metastatic gastric, gastroesophageal junction, or esophageal adenocarcinoma (2024). Available online at: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20211021005619/en/Agilent-PD-L1-IHC-28-8-pharmDx-Receives-CE-IVD-Mark-as-a-Companion-Diagnostic-Test-in-Advanced-or-Metastatic-Gastric-Gastroesophageal-Junction-or-Esophageal-Adenocarcinoma (Accessed November 11, 2025).

33. Agilent Technologies I. PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx for gastric, GEJ, and esophageal adenocarcinoma (2021). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/brochures/29457-d68866-pd-l1-28-8-gastric-brochure-en-eu.pdf (Accessed February 17, 2025).

34. Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharma EEIG. OPDIVO 10 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion (Summary of Product Characteristics) (2020). Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/opdivo-epar-product-information_en.pdf (Accessed February 4, 2025).

35. US Food and Drug Administration. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED) (2023). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf16/P160046S013B.pdf (Accessed February 17, 2025).

36. Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Chugai obtains approval for Tecentriq as a monotherapy for chemotherapy-naïve PD-L1-positive unresectable advanced or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). December 25, 2020. Available online at: https://www.chugai-pharm.co.jp/english/news/detail/20201225170000_789.html (Accessed February 17, 2025).

37. PR Newswire. Roche's VENTANA PD-L1 (SP263) Assay receives CE IVD approval to identify patients with locally advanced and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer eligible for Libtayo. (2022). Available online at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/roches-ventana-pd-l1-sp263-assay-receives-ce-ivd-approval-to-identify-patients-with-locally-advanced-and-metastatic-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-eligible-for-libtayo-301621285.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

38. F. Hoffman-La Roche Inc. Roche’s VENTANA PD-L1 (SP263) test gains CE label expansion as a companion diagnostic to identify non-small cell lung cancer patients eligible for Tecentriq. (2022). Available online at: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/roches-ventana-pd-l1-sp263-test-gains-ce-label-expansion-as-a-companion-diagnostic-to-identify-non-small-cell-lung-cancer-patients-eligible-for-tecentriq-301611199.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

39. Vennapusa B, Baker B, Kowanetz M, Boone J, Menzl I, Bruey JM, et al. Development of a PD-L1 complementary diagnostic immunohistochemistry assay (SP142) for atezolizumab. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2019) 27:92–100. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000594

40. FDA approved PD-L1 (SP142) assay for lung cancer. Oncol Times. (2016) 38:27. doi: 10.1097/01.COT.0000511177.08533.08

41. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC with high PD-L1 expression(2020). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-atezolizumab-first-line-treatment-metastatic-nsclc-high-pd-l1-expression (Accessed November 11, 2025).

42. Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. Chugai obtains approval for additional indication and formulation for Tecentriq in PD-L1-positive triple negative breast cancer (2019). Available online at: https://www.chugai-pharm.co.jp/english/news/detail/20190920153002_648.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

43. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. VENTANA® PD-L1 (SP142) Assay (2025). Available online at: https://diagnostics.roche.com/global/en/products/lab/pd-l1-sp142-assay-us-export-ventana-rtd001232.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

44. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx2021(2021). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/packageinsert/public/P05051EN_04.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

45. Emancipator K, Huang L, Aurora-Garg D, Bal T, Cohen EEW, Harrington K, et al. Comparing programmed death ligand 1 scores for predicting pembrolizumab efficacy in head and neck cancer. Mod Pathol. (2021) 34:532–41. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00710-9

46. Kintsler S, Cassataro MA, Drosch M, Holenya P, Knuechel R, and Braunschweig T. Expression of programmed death ligand (PD-L1) in different tumors. Comparison of several current available antibody clones and antibody profiling. Ann Diagn Pathol. (2019) 41:24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2019.05.005

47. Lawson NL, Dix CI, Scorer PW, Stubbs CJ, Wong E, Hutchinson L, et al. Mapping the binding sites of antibodies utilized in programmed cell death ligand-1 predictive immunohistochemical assays for use with immuno-oncology therapies. Mod Pathol. (2020) 33:518–30. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0372-z

48. Merck & Co., Inc. FDA approves Merck’s KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) in metastatic NSCLC for first-line treatment of patients whose tumors have high PD-L1 expression (tumor proportion score [TPS] of 50 percent or more) with no EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations (2016). Available online at: https://www.merck.com/news/fda-approves-mercks-keytruda-pembrolizumab-in-metastatic-nsclc-for-first-line-treatment-of-patients-whose-tumors-have-high-pd-l1-expression-tumor-proportion-score-tps-of-50-percent/ (Accessed November 11, 2025).

49. Rosa K. FDA approves companion diagnostic for cemiplimab in NSCLC(2021). Available online at: https://www.onclive.com/view/fda-approves-companion-diagnostic-for-cemiplimab-in-nsclc (Accessed November 11, 2025).

50. Hirsch FR, Averbuch S, Emami T, Walker J, Williams A, Stanforth D, et al. The Blueprint Project: harmonizing companion diagnostics across a class of targeted therapies blueprint results. Presented at: The American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting; New Orleans, LA, USA; 16–20 April 2016.

51. Tsao MS, Kerr KM, Kockx M, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Botling J, et al. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry comparability study in real-life clinical samples: results of Blueprint Phase 2 Project. J Thorac Oncol. (2018) 13:1302–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.05.013

52. Sompuram SR, Torlakovic EE, t Hart NA, Vani K, and Bogen SA. Quantitative comparison of PD-L1 IHC assays against NIST standard reference material 1934. Mod Pathol. (2021) 35:326–32. doi: 10.1038/s41379-021-00884-w

53. Scheerens H, Malong A, Bassett K, Boyd Z, Gupta V, Harris J, et al. Current status of companion and complementary diagnostics: strategic considerations for development and launch. Clin Transl Sci. (2017) 10:84–92. doi: 10.1111/cts.12455

54. Vainer G, Huang L, Emancipator K, and Nuti S. Equivalence of laboratory-developed test and PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx across all combined positive score indications. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0285764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285764

55. Genzen JR. Regulation of laboratory-developed tests. Am J Clin Pathol. (2019) 152:122–31. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqz096

56. Spitzenberger F, Patel J, Gebuhr I, Kruttwig K, Safi A, and Meisel C. Laboratory-developed tests: design of a regulatory strategy in compliance with the International State-of-the-Art and the Regulation (EU) 2017/746 (EU IVDR [In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device Regulation]). Ther Innov Regul Sci. (2022) 56:47–64. doi: 10.1007/s43441-021-00323-7

57. Torlakovic EE. PD-L1 IHC testing: issues with interchangeability evidence based on laboratory-developed assays of unknown analytical performance. Gastric Cancer. (2022) 25:1131–2. doi: 10.1007/s10120-022-01336-3

58. Goldsmith JD, Troxell ML, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Colasacco CF, Edgerton ME, Fitzgibbons PL, et al. Principles of analytic validation of immunohistochemical assays: guideline update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2024) 148:e111–53. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2023-0483-CP

59. US Food and Drug Administration. Laboratory developed tests (2024). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics/laboratory-developed-tests (Accessed November 11, 2025).

60. Emoto K, Yamashita S, and Okada Y. Mechanisms of heat-induced antigen retrieval: does pH or ionic strength of the solution play a role for refolding antigens? J Histochem Cytochem. (2005) 53:1311–21. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5C6627.2005

61. Neuman T, London M, Kania-Almog J, Litvin A, Zohar Y, Fridel L, et al. A harmonization study for the use of 22C3 PD-L1 immunohistochemical staining on Ventana's platform. J Thor Oncol. (2016) 11:1863–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.146

62. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx interpretation manual, triple-negative breast cancer (2023). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/29389_22c3_pharmdx_tnbc_interpretation_manual_kn355.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2024).

63. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx, interpretation manual—NSCLC (2018). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/29158_pd-l1-ihc-22C3-pharmdx-nsclc-interpretation-manual.pdf (Accessed June 7, 2024).

64. Chen M, Xu Y, Zhao J, Li J, Liu X, Zhong W, et al. Feasibility and reliability of evaluate PD-L1 expression determination using small biopsy specimens in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. (2021) 12:2339–44. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.14075

65. Wang Y, Wu J, Deng J, She Y, and Chen C. The detection value of PD-L1 expression in biopsy specimens and surgical resection specimens in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. (2021) 13:4301–10. doi: 10.21037/jtd-21-543

66. Zdrenka M, Kowalewski A, Borowczak J, Łysik-Miśkurka J, Andrusewicz H, Nowikiewicz T, et al. Diagnostic biopsy does not accurately reflect the PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Exp Med. (2023) 23:5121–7. doi: 10.1007/s10238-023-01190-2

67. Ilie M, Long-Mira E, Bence C, Butori C, Lassalle S, Bouhlel L, et al. Comparative study of the PD-L1 status between surgically resected specimens and matched biopsies of NSCLC patients reveal major discordances: a potential issue for anti-PD-L1 therapeutic strategies. Ann Oncol. (2016) 27:147–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv489

68. Lozano MD, Abengozar-Muela M, Echeveste JI, Subtil JC, Bertó J, Gúrpide A, et al. Programmed death–ligand 1 expression on direct pap-stained cytology smears from non–small cell lung cancer: Comparison with cell blocks and surgical resection specimens. Cancer Cytopathology. (2019) 127:470–80. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22155

69. Heymann JJ, Bulman WA, Swinarski D, Pagan CA, Crapanzano JP, Haghighi M, et al. PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma: Comparison among cytology, small biopsy, and surgical resection specimens. Cancer Cytopathol. (2017) 125:896–907. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21937

70. Lau SCM, Rabindranath M, Weiss J, Li JJN, Fung AS, Mullen D, et al. PD-L1 assessment in cytology samples predicts treatment response to checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC. Lung Cancer. (2022) 171:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.07.018

71. Kim HR, Cha YJ, Hong MH, Gandhi M, Levinson S, Jung I, et al. Concordance of programmed death-ligand 1 expression between primary and metastatic non-small cell lung cancer by immunohistochemistry and RNA in situ hybridization. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:87234–43. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20254

72. Kim S, Koh J, Kwon D, Keam B, Go H, Kim YA, et al. Comparative analysis of PD-L1 expression between primary and metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Eur J Cancer. (2017) 75:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.01.004

73. Dako North America, Inc. Summary of safety and effectiveness data (SSED)(2017). Available online at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/P150013S006b.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

74. Placke JM, Kimmig M, Griewank K, Herbst R, Terheyden P, Utikal J, et al. Correlation of tumor PD-L1 expression in different tissue types and outcome of PD-1-based immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma - analysis of the DeCOG prospective multicenter cohort study ADOREG/TRIM. EBioMedicine. (2023) 96:104774. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104774

75. Moutafi MK, Tao W, Huang R, Haberberger J, Alexander B, Ramkissoon S, et al. Comparison of programmed death-ligand 1 protein expression between primary and metastatic lesions in patients with lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. (2021) 9:e002230. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002230

76. Xu H, Chen X, Lin D, Zhang J, Li C, Zhang D, et al. Conformance assessment of PD-L1 expression between primary tumour and nodal metastases in non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. (2019) 12:11541–7. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S223643

77. Boman C, Zerdes I, Mårtensson K, Bergh J, Foukakis T, Valachis A, et al. Discordance of PD-L1 status between primary and metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. (2021) 99:102257. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102257

78. Li Y, Vennapusa B, Chang C-W, Tran D, Nakamura R, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Prevalence study of PD-L1 SP142 assay in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2021) 29:258–64. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000857

79. Robert ME, Rüschoff J, Jasani B, Graham RP, Badve SS, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. High interobserver variability among pathologists using combined positive score to evaluate PD-L1 expression in gastric, gastroesophageal junction, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. (2023) 36:100154. doi: 10.1016/j.modpat.2023.100154

80. Agilent Technologies Inc. PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx Interpretation Manual – Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC)(2023). Available online at: https://www.agilent.com/cs/library/usermanuals/public/29314_22c3_pharmDx_hnscc_interpretation_manual_us.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

81. Discovery Life Sciences. ECP 2019 – A standardized structured training of pathologists scoring PD-L1 in NSCLC(2023). Available online at: https://dls.com/resources/ecp-2019-a-standardized-structured-training-of-pathologists-scoring-pd-l1-in-nsclc/#:~:text=ECP%202019%20%E2%80%93%20A%20standardized%20structured,scoring%20PD%2DL1%20in%20NSCLC&text=Immunohistochemical%20diagnostic%20testing%20for%20programmed,small%20cell%20lung%20cancer%2C%20NSCLC (Accessed November 11, 2025).

82. Nuti S, Zhang Y, Zerrouki N, Roach C, Bänfer G, Kumar GL, et al. High interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility among pathologists assessing PD-L1 CPS across multiple indications. Histopathology. (2022) 81:732–41. doi: 10.1111/his.14775

83. Jasani B, Bänfer G, Oberthür R, Diezko R, Kumar GL, Rüschoff J, et al. A standardised structured training of pathologists scoring PD-L1 in NSCLC. August 2019. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354209460_A_standardised_structured_training_of_pathologists_scoring_PD-L1_in_NSCLC (Accessed November 11, 2025).

84. Jasani B, Bänfer G, Fish R, Waelput W, Sucaet Y, Barker C, et al. Evaluation of an online training tool for scoring programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) diagnostic tests for lung cancer. Diagn Pathol. (2020) 15:37. doi: 10.1186/s13000-020-00953-9

85. Nielsen S, Bzorek M, Vyberg M, and Røge R. Lessons learned, challenges taken, and actions made for "precision" immunohistochemistry. Analysis and perspectives from the NordiQC proficiency testing program. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2023) 31:452–8. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000001071

86. Mino-Kenudson M, Le Stang N, Daigneault JB, Nicholson AG, Cooper WA, Roden AC, et al. The international association for the study of lung cancer global survey on programmed death-ligand 1 testing for NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2021) 16:686–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.12.026

87. Nielsen S. NordiQC EQA Data and Observations for PD-L1 Biomarker Testing(2021). Available online at: https://www.iqnpath.org/nordiqc-eqa-data-and-observations-for-pd-l1-biomarker-testing/ (Accessed June 10, 2024).

88. European Society of Pathology. EQA programme: Programmed Death Ligand 1 (PDL1). (2024). Available online at: https://www.sekk.cz/PDL1/2024_PDL1_flyer.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

89. Dodson A, Parry S, Lissenberg-Witte B, Haragan A, Allen D, O'Grady A, et al. External quality assessment demonstrates that PD-L1 22C3 and SP263 assays are systematically different. J Pathol Clin Res. (2020) 6:138–45. doi: 10.1002/cjp2.153

90. Vyberg M and Nielsen S. Proficiency testing in immunohistochemistry–experiences from Nordic Immunohistochemical Quality Control (NordiQC). Virchows Arch. (2016) 468:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1829-1

91. Wang X, Wang L, Bu H, Zhang N, Yue M, Jia Z, et al. How can artificial intelligence models assist PD-L1 expression scoring in breast cancer: results of multi-institutional ring studies. NPJ Breast Cancer. (2021) 7:61. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00268-y

92. Sha L, Osinski BL, Ho IY, Tan TL, Willis C, Weiss H, et al. Multi-field-of-view deep learning model predicts nonsmall cell lung cancer programmed death-ligand 1 status from whole-slide hematoxylin and eosin images. J Pathol Inform. (2019) 10:24. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_24_19

93. Choi S, Cho SI, Ma M, Park S, Pereira S, Aum BJ, et al. Artificial intelligence-powered programmed death ligand 1 analyser reduces interobserver variation in tumour proportion score for non-small cell lung cancer with better prediction of immunotherapy response. Eur J Cancer. (2022) 170:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.04.011

94. Hondelink LM, Hüyük M, Postmus PE, Smit V, Blom S, Von Der Thüsen JH, et al. Development and validation of a supervised deep learning algorithm for automated whole-slide programmed death-ligand 1 tumour proportion score assessment in non-small cell lung cancer. Histopathology. (2022) 80:635–47. doi: 10.1111/his.14571

Keywords: immune checkpoint inhibitors, PD-L1 assays, PD-L1 expression, PD-L1 scoring method, regulatory approval

Citation: Vainer GW, Badve SS, Rajadurai P, Soares FA, Viale G, Büttner R, Nuti S, Juco J, Krishnan R and Tsao M-S (2025) Unraveling the complexity of PD-L1 assays: a descriptive review of the methodology, scoring, and practical implications. Front. Oncol. 15:1581275. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1581275

Received: 21 February 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Stefano Cavalieri, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, ItalyReviewed by:

Pingping CHEN, University of Miami, United StatesFeiteng Lu, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Corporate Member of Freie Universität Berlin, and Humboldt-Universität zu, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Vainer, Badve, Rajadurai, Soares, Viale, Büttner, Nuti, Juco, Krishnan and Tsao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ming-Sound Tsao, TWluZy5Uc2FvQHVobi5jYQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Gilad W. Vainer1†

Gilad W. Vainer1† Sunil S. Badve

Sunil S. Badve Pathmanathan Rajadurai

Pathmanathan Rajadurai Reinhard Büttner

Reinhard Büttner Ming-Sound Tsao

Ming-Sound Tsao