- 1Department of Gastric Surgery, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Zhangzhou, Fujian, China

- 2Department of Ultrasound, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Zhangzhou, Fujian, China

- 3Department of Statistics, Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Zhangzhou, Fujian, China

Objective: This study aims to analyze the benefits of indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging on the efficacy of lymph node dissection (LND) during laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) for advanced upper gastric cancer.

Materials and methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological data of 98 patients with advanced upper gastric cancer undergoing LTG, including 29 patients in the ICG-guided group and 69 in the conventional LTG (non-ICG) group. The perioperative outcomes, efficiency of LND, and survival outcomes were compared between the two groups.

Results: The mean number of lymph nodes (LNs) dissected was greater in the ICG group than the non-ICG group (52.34 vs. 37.38; P < 0.001). Additionally, the ICG group had more patients with > 30 dissected LNs (96.55% vs. 76.81%; P = 0.018). Notably, the ICG group exhibited a higher number of LNs dissected at stations 7, 8, 9, and 11 than the non-ICG group (P < 0.05). Metastatic LNs were more frequently identified among fluorescence-positive LNs (P = 0.002). ICG fluorescence imaging demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance for metastatic LNs with a sensitivity of 85.9% and a negative predictive value of 96%. The ICG and non-ICG groups showed comparable 2-year overall survival (86.2% vs 82.6%, p=0.737) and disease-free survival (82.8% vs 72.5%, p=0.203) rates.

Conclusions: ICG fluorescence imaging significantly improved lymphadenectomy precision during LTG for advanced upper gastric cancer, particularly in suprapancreatic nodal stations, and enhanced detection of metastatic LNs. However, no obvious survival benefit was observed within the limited follow-up period. Future prospective, multicenter studies are warranted to validate these results.

1 Introduction

Gastric cancer is a significant health burden in China, with a high incidence rate and poor prognosis, as the majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages (1). Surgical intervention remains a cornerstone of the management of advanced gastric cancer. In particular, the use of laparoscopic radical total gastrectomy (LTG) has increased owing to its minimal invasiveness, enabling rapid recovery (2, 3). However, advanced gastric cancer in the upper stomach requiring LTG poses a distinct surgical challenge. This procedure involves not only standard suprapancreatic lymph node dissection but also necessitates clearance of stations specific to the gastric fundus and proximal anatomy. These steps are technically demanding and carry increased risks of complications such as pancreatic fistula or splenic vessel injury. Consequently, a thorough lymphadenectomy in LTG carries a high risk of incomplete nodal retrieval, especially in these critical zones. This incompletion may, in turn, compromise oncologic outcomes.

With the evolution of precision medicine and surgical advancements, indocyanine green (ICG) near-infrared imaging has emerged as a valuable tool for laparoscopic gastric cancer surgery. This technology enables real-time visualization of lymphatic drainage and lymph node (LN) locations, providing surgeons with intuitive navigational information that may lead to more thorough lymph node dissection (LND) and improved surgical efficacy (4, 5). However, existing literature on ICG navigation in gastric cancer often amalgamates results from diverse tumor locations and surgical procedures. This heterogeneity may obscure its precise value in specific, high-risk scenarios. Despite the promising results, there is an ongoing debate regarding which lymph node regions or patient populations benefit the most from ICG-guided dissection, alongside unresolved debates regarding its prognostic implications (6).

In light of these considerations, the present study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of the efficacy of ICG in lymphadenectomy and its application to the diagnosis of metastatic lymph nodes during LTG for advanced gastric cancer. Furthermore, this study delved into the prognostic implications of ICG-guided lymphadenectomy, ultimately offering granular clinical evidence to optimize precision oncology strategies in gastric cancer management.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients

A total of 179 patients with advanced upper gastric cancer who underwent LTG at the Department of Gastric Surgery, Affiliated Zhangzhou Hospital of Fujian Medical University from June 2021 to December 2022 were enrolled in this study. All included cases were operated by the same surgical team, with procedures performed by a senior surgeon (>300 laparoscopic gastrectomies) proficient in ICG near-infrared fluorescence imaging.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 16 and 80 years; D2 lymph node dissection; postoperative pathology-confirmed gastric adenocarcinoma; and pathological staging of pT2-4a, N0-3, or M0. The exclusion criteria included the presence of distant metastasis, a history of gastric surgery (including endoscopic treatment for gastric cancer), prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy, combined organ resection or thoracic surgery, linitis plastica, or missing clinical or pathological data. All enrolled patients received 4–6 cycles of standardized adjuvant chemotherapy (SOX or S1 regimen).

Patient assignment to the ICG or non-ICG group was determined clinically. ICG fluorescence navigation was routinely recommended for all eligible patients. Its final application depended on informed patient/family consent, the availability of the fluorescence imaging system, and intraoperative findings. Ultimately, 98 patients were included in the study and divided into the following two groups based on the surgical approach: ICG fluorescence imaging group (29 cases) and non-ICG fluorescence imaging group (69 cases). This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Zhangzhou Hospital, Fujian Medical University(Approval No. 2024LWB425). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

2.2 Surgical procedures

The ICG injection protocol was standardized and identical for all patients in the ICG group. ICG was used as a tracer agent intraoperatively, following the recommended serosal injection method and pattern (7). ICG (25 mg/vial, diluted to 0.5 mg/mL with sterile water for injection) was injected at three points on the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach, with 1.5 mL administered subserosally at each point, 20 min before LND. On the lesser curvature, injections were performed at the first branch of the right gastric artery, the angular incisure, and the midpoint between the first and second gastric wall branches of the left gastric artery. On the greater curvature, injections were performed at the first gastric branch of the right gastroepiploic artery, the first gastric branch of the left gastroepiploic artery, and the junction of the gastric fundus and body. The recommended injection points are depicted in supplementary Figure 1. In case the injection point is invaded by the tumor, the tumor margin is suggested as the injection point. The fluorescence mode was switched for navigation during LND (supplementary Figure 2). Dissection of the splenic hilar lymph nodes was reserved for tumors involving the upper gastric greater curvature or cases with suspected nodal metastasis on preoperative computed tomography imaging/intraoperative findings.

ICG was not used in the non-ICG group, and conventional laparoscopic gastric cancer radical surgery was performed according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Guidelines (8). To achieve accurate tumor N staging, lymph nodes were sorted by the operating surgeon based on their location before pathological examination. In the ICG group, specimens were examined based on the ICG system product fluorescence after removal. Lymph nodes displaying fluorescence and those not displaying fluorescence were separately packaged, fixed with 10% formalin, and sent for pathological examination.

2.3 Observation items and definitions

Intraoperative blood loss was estimated using the suction and gauze weight method. The time to first ambulation was recorded when patients stood and walked at least 5 m. The time to first flatus was confirmed based on patient reports and auscultation by medical staff. The time to first oral intake was noted when patients consumed food orally for the first time. Postoperative hospital stay was measured from the end of surgery to the time of discharge.

The diagnostic performance of ICG fluorescence for metastatic lymph nodes (LNs) was evaluated per node. Each harvested LN in the ICG group was intraoperatively classified as fluorescent or non-fluorescent. Postoperative histopathology served as the gold standard, defining the following categories: True Positive (TP: fluorescent & metastatic), False Positive (FP: fluorescent and benign), True Negative (TN: non-fluorescent and benign), and False Negative (FN: non-fluorescent and metastatic). Sensitivity was calculated as TP/(TP+FN). Specificity was the proportion of non-metastatic LNs correctly identified as non-fluorescent (TN/[TN+FP]). The positive predictive value (PPV) was the proportion of fluorescent LNs that were metastatic (TP/[TP+FP]), and the negative predictive value (NPV) was the proportion of non-fluorescent LNs that were non-metastatic (TN/[TN+FN]). The Youden index was calculated as (Sensitivity + Specificity - 1).

Postoperative surgical complications, mainly related to the surgical system, included incisional infections, gastrointestinal leaks, postoperative bleeding, abdominal infections, and gastrointestinal obstructions (9), recorded within 1 month and graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification system were included in analyses (10).

Overall Survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause. Disease-Free Survival (DFS) was defined as the time from surgery to tumor recurrence or death from any cause, whichever came first.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Normally distributed continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, and intergroup comparisons were performed using independent-samples Student’s t-tests. Data that were not normally distributed were analyzed using non-parametric tests. Categorical data are expressed as numbers and percentages, and intergroup comparisons were performed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact probability test. Survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method to construct survival curves, followed by log-rank testing for between-group comparisons of time-to-event data. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

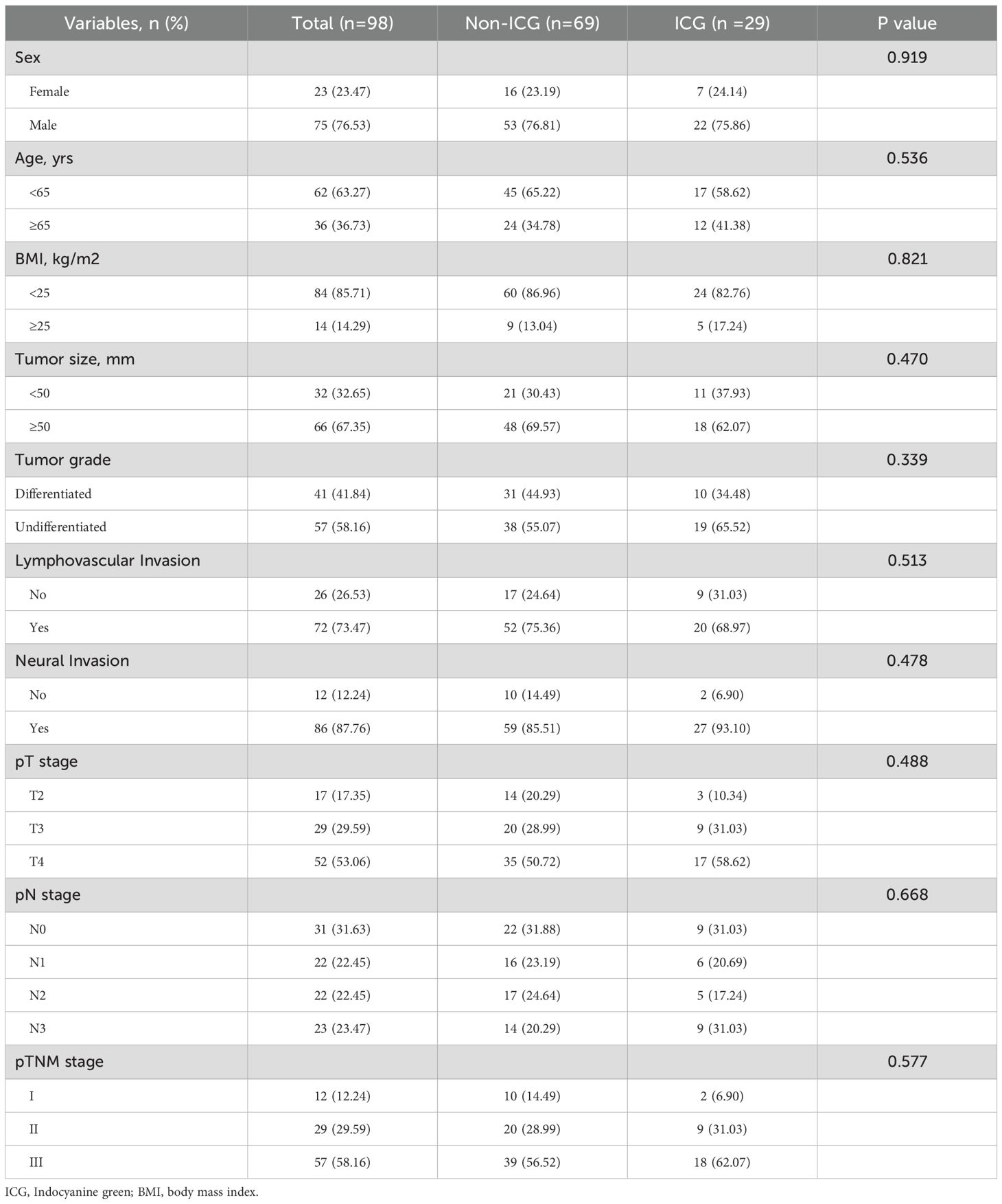

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in age, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor size, degree of differentiation, neural invasion, vascular invasion, pT stage, pN stage, or pTNM stage between the ICG and non-ICG groups (all P > 0.05).

3.2 Perioperative outcomes

The ICG and non-ICG groups showed no differences in intraoperative blood loss, time to first ambulation, time to first flatus, time to first oral intake, or postoperative hospital stay (all P > 0.05). The overall postoperative surgical complication rate was 19.64%, with estimates of 21.74% in the non-ICG group and 17.24% in the ICG group (P = 0.614). The majority of complications were grade II according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system, with postoperative infections and bleeding being the most common types. The incidence and severity of complications were comparable between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 2).

3.3 Comparison of LND between the two groups

As shown in Table 3, the mean total number of LNs dissected was higher in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group (52.34 vs. 37.38; P < 0.001). The proportion of patients with > 30 dissected LNs was also higher in the ICG group (96.55% vs. 76.81%, P = 0.018). Additionally, greater numbers of LNs were retrieved from both the perigastric (33.41 vs. 26.65; P = 0.009) and extraperigastric (19.10 vs. 10.72; P < 0.001) regions in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group. Stratified analyses confirmed that the mean total number of nodes dissected remained higher in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group across various subgroups, including sex, BMI, tumor size, tumor grade, and pT, pN, and pTNM stages.

Notably, at station 4 and the superior margin area of the pancreas (stations 7, 8, 9, and 11), the ICG group exhibited a greater number of LNs dissected than that in the non-ICG group (P < 0.05). (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of mean lymph node dissection count in the ICG and non-ICG groups. SE, Standard Error. The asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.4 Relationship between fluorescence and lymph node metastasis

Within the ICG group, the number of fluorescent LNs was greater than the number of non-fluorescent LNs (35.78 vs. 16.56; P < 0.001), and metastatic LNs were more frequently identified among fluorescent LNs (4.01 vs. 0.67; P = 0.002). In the stratified analysis according to LN station, the number of fluorescent LNs consistently exceeded the number of non-fluorescent LNs at each station, and metastatic fluorescent LNs were more frequently identified at stations 1, 2, 3 and 7. (Figure 2). ICG fluorescence imaging demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance for metastatic LNs, with a sensitivity of 85.9% and negative predictive value of 96% (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. Comparison of mean fluorescent and non-fluorescent lymph node retrieval and number of metastatic fluorescents in ICG Group. SE, Standard Error.

3.5 Comparative analysis of postoperative survival outcomes

With the final follow-up date extending through February 28, 2025, the median follow-up duration for the entire cohort was 34 months (range: 26–44 months). Comparative analysis revealed comparable 2-year survival outcomes between groups: the ICG group demonstrated 86.2% OS and 82.8% DFS rates, while the non-ICG group achieved 82.6% OS and 72.5% DFS rates. These intergroup differences did not reach statistical significance (OS: p=0.737; DFS: p=0.203), as detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Comparison of survival outcomes in the ICG and non-ICG groups: (A) Overall survival; (B) Disease-free survival.

4 Discussion

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that ICG fluorescence imaging provides significant value in ensuring a complete lymphadenectomy during LTG for advanced upper gastric cancer, a procedure characterized by unique technical challenges. Consistent with our focus on the technical difficulties of LTG, the data revealed that the benefit of ICG was not uniform but was particularly evident in key anatomical regions (Stations #7, #8, #9, and #11).

ICG is well-recognized for its safety profile, characterized by minimal toxicity and a low risk of allergic reactions. Most studies confirm that ICG navigation is both safe and feasible, demonstrating comparable short-term outcomes to conventional laparoscopic surgery without increasing postoperative complications (11, 12). In our study, the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative recovery, and postoperative surgical complication rates did not differ between the ICG and non-ICG groups (P > 0.05). The number of LNs dissected was significantly higher in the ICG group than the non-ICG group, while the mean number of LN metastases did not differ between the two groups. In a meta-analysis of 13 studies showed that, without increasing the operation time, intraoperative blood loss, or postoperative complications, more LNs were dissected in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group (P < 0.001) (13). Similarly, in the FUGES-012 prospective study, more LNs were dissected in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group (50.5 vs. 42.0, P < 0.01), with comparable postoperative recovery and complication rates between the two groups (14). However, Lan et al. (15) found that the ICG group did not result in an increase in the total number of nodes dissected, and this difference among studies may be related to differences in ICG injection methods and concentrations.

Accurate N staging requires dissection of at least 16 LNs, with 30 or more LNs being optimal (8). In our study, all patients had more than 16 LNs dissected, and the proportion of patients with more than 30 dissected LNs was higher in the ICG group than the non-ICG group, indicating that ICG helps identify missed lymphatic tissue and increases the number of LNs dissected. Kwon et al. (16) found that the ICG resulted in a significantly higher number of nodes dissected at stations 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Lee et al. (17) reported that the ICG group had an advantage in LNs dissected at station 10. The divergent patterns of lymph node enhancement observed across studies may be attributed to several factors. A key methodological difference is the ICG injection technique; the endoscopic submucosal injection used in the cited studies (16, 17) targets a different lymphatic drainage initiation point compared to the subserosal approach employed in our work, which could lead to variations in the primary lymphatic basins highlighted. Furthermore, differences in patient populations and proficiency in interpreting ICG fluorescence likely also contribute to the observed variances. Our study found that more LNs were retrieved in the ICG group, particularly in the upper pancreatic region (stations 7, 8, 9, 11). This is likely attributable to the area’s complex anatomy, which features abundant lymphatic and vascular adipose tissue with ill-defined planes to the pancreas. In such cases, ICG imaging can effectively guide and improve the dissection precision. Additionally, a stratified analysis confirmed that the mean total number of nodes dissected remained higher in the ICG group than in the non-ICG group across various subgroups (e.g., sex, BMI, tumor size, tumor grade, and pT, pN, and pTNM stage), consistent with previous results (14, 18). Furthermore, we found that the number of fluorescent LNs was higher than the number of non-fluorescent LNs, and the fluorescent LNs had a higher mean number of metastatic LNs than did the non-fluorescent LNs. The diagnostic sensitivity of ICG imaging for metastatic LNs was 85.9%, which is consistent with the reported range of 52.6–95.3% (19, 20). This indicates that fluorescent LNs receive lymphatic drainage from the tumor surroundings, but may not necessarily have cancer metastasis. The negative predictive value of nonfluorescent lymph nodes in our study was 96.0%; the false-negative rate was non-zero, consistent with that in previous studies (21, 22). This suggests that the lymphatic return pathways of some metastatic LNs were completely blocked by cancer cells, thereby preventing ICG backflow. However, the notably low specificity (33.4%) and Youden Index (0.19) indicate a high false-positive rate, meaning that a positive fluorescence signal is not a reliable predictor of metastasis. This underscores that fluorescence can be triggered by factors other than cancer cells, such as inflammation or macrophage accumulation in benign nodes. Therefore, the principal clinical value of ICG lies in its role as an exceptional lymphatic mapping and retrieval tool to guide a thorough lymphadenectomy, rather than as an intraoperative diagnostic test for metastasis. Surgeons should utilize ICG to enhance lymph node harvest completeness but must continue to depend on definitive postoperative histopathology for nodal staging.

Emerging evidence suggests that more extensive lymphadenectomy may confer survival benefits in long-term follow-up, yet data regarding the prognostic impact of ICG-guided radical gastrectomy remain scarce. Huang et al. conducted a prospective clinical trial demonstrating that ICG-navigated laparoscopic gastrectomy significantly improved 3-year OS (86.0% vs 73.6%, p=0.015) and DFS (81.4% vs 68.2%, p=0.012) rates compared to conventional surgery (23). However, a Spanish propensity score-matched study revealed comparable 2-year OS and DFS rates between ICG and non-ICG groups (24). Intriguingly, our study similarly demonstrated no statistically significant differences in 2-year OS ((86.2% vs 82.6%, p=0.737) or DFS (82.8% vs 72.5%, p=0.203) between cohorts. Furthermore, by strictly enrolling only patients with upfront surgery who completed standardized adjuvant chemotherapy, we aimed to isolate the effect of ICG navigation on surgical quality and intermediate outcomes, reducing the confounding impact of heterogeneous systemic therapy. However, the interpretation of long-term survival trends is constrained by the progressive reduction in the number of patients at risk beyond 30 months (Figure 3), which limits the statistical reliability of the Kaplan-Meier estimates in the later follow-up period. Therefore, the long-term trajectories of the survival curves should be interpreted with caution. The divergent outcomes across studies can be attributed to multiple factors: inherent patient heterogeneity; variations in surgical protocols, especially in operator-dependent factors like surgical skill and ICG mastery; and methodological inconsistencies in follow-up and assessment. Notably, The current evidence may underestimate true clinical outcomes because the non-ICG group’s median lymph node retrieval exceeds 30—a benchmark for adequate dissection. This suggests that while ICG enhances dissection, the non-ICG group’s lymph node retrieval quality may already be sufficient. Thus, further improvements in lymphadenectomy are unlikely to affect survival outcomes.

Looking forward, the future of fluorescence-guided precision surgery in gastric cancer lies in overcoming the specificity limitations inherent to non-targeted agents like ICG. While ICG serves as an excellent lymphatic mapping tool, as demonstrated by its high sensitivity, its low specificity for metastasis underscores the need for more selective targeting strategies. The emerging field of tumor-specific molecular imaging aims to address this precise challenge. The development of fluorescent probes targeting tumor-specific biomarkers—such as carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), or other gastric cancer-associated antigens—holds the potential to truly revolutionize surgical oncology (25). Such targeted agents could enable the visual intraoperative discrimination of metastatic from non-metastatic lymph nodes. This would shift the paradigm from a thorough, anatomy-based lymphadenectomy guided by non-targeted mapping to a precision resection that specifically preserves non-metastatic nodes.

Our study has several important limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its retrospective design and conduct at a single institution carry an inherent risk of selection bias and may limit the generalizability of our findings to broader populations with different surgical protocols and patient demographics. Second, although based on existing literature, the ICG administration and imaging protocol lacked universal standardization, potentially introducing variability in fluorescence signals. Third, the modest sample size and significant group imbalance (ICG: 29 vs. Non-ICG: 69) are important limitations. This imbalance renders the study potentially underpowered, increasing the risk of Type II errors wherein clinically meaningful survival benefits might have been undetected. Finally, the relatively short follow-up period precludes definitive conclusions on long-term outcomes. Therefore, our findings should be considered exploratory and validated through prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled trials.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, ICG fluorescence imaging demonstrated superior efficacy in optimizing lymph node dissection precision during LTG for advanced upper gastric cancer, particularly at anatomically challenging suprapancreatic nodal stations. Notably, its ability to intraoperatively pinpoint LNs at higher risk for metastasis serves as a valuable adjunct to conventional surgical protocols. Nevertheless, the technique did not demonstrate significant survival advantages within the current observation period. Further investigation with extended follow-up is warranted to determine whether these technical improvements may translate into measurable long-term oncological benefits.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Zhangzhou Hospital, Fujian Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

C-BL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft. L-YT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. Y-QS: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. R-JH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. H-HH: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Q-XC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. L-SC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J011567); Climbing Project of Doctor’s Studio of Zhangzhou Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University (PDB202109).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of nurses, pathologists, researchers, peer reviewers, and editors who voluntarily supported this study without financial compensation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1588048/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | The recommended injection points for subserosal injection of ICG.

Supplementary Figure 2 | ICG fluorescence imaging sample pictures during lymph node dissection. (A, B): Fluorescent lymph nodes; (C): Fluorescent lymphatic vessels; (D): Exposed right gastroepiploic vein after the lymphoid tissue was dissected.

Abbreviations

BMI, body mass index; CEACAM5, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5; DFS, Disease-Free Survival; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ICG, Indocyanine Green; LND, lymph node dissection; LNM, lymph node metastasis; LN, lymph node; LTG, laparoscopic total gastrectomy; OS, Overall Survival; SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

References

1. Fan X, Qin X, Zhang Y, Li Z, Zhou T, Zhang J, et al. Screening for gastric cancer in China: Advances, challenges and visions. Chin J Cancer Res. (2021) 33:168–80. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2021.02.05

2. Liu F, Huang C, Xu Z, Su X, Zhao G, Ye J, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic vs open total gastrectomy for clinical stage I gastric cancer: the CLASS02 multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2020) 6:1590–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3152

3. Yang Y, Chen Y, Hu Y, Feng Y, Mao Q, and Xue W. Outcomes of laparoscopic versus open total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. (2022) 27:124. doi: 10.1186/s40001-022-00748-2

4. Sposito C, Maspero M, Conalbi V, Magarotto A, Altomare M, Battiston C, et al. Impact of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging on lymphadenectomy quality during laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer (Greeneye): an adaptative, phase 2, clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. (2023) 30:6803–11. doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13848-y

5. Dehal A, Woo Y, Glazer ES, Davis JL, Strong VE, and Society of Surgical Oncology Gastrointestinal Disease Site Workgroup. D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: advancements and technical considerations. Ann Surg Oncol. (2025) 32:2129–40. doi: 10.1245/s10434-024-16545-6

6. Li H, Xie X, Du F, Zhu X, Ren H, Ye C, et al. A narrative review of intraoperative use of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in gastrointestinal cancer: situation and future directions. J Gastrointest Oncol. (2023) 14:1095–113. doi: 10.21037/jgo-23-230

7. Chen QY, Zhong Q, Li P, Xie JW, Liu ZY, Huang XB, et al. Comparison of submucosal and subserosal approaches toward optimized indocyanine green tracer-guided laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for patients with gastric cancer (FUGES-019): a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. (2021) 19:276. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02125-y

8. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer. (2023) 26:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10120-022-01331-8

9. Dindo D, Demartines N, and Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. (2004) 240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

10. Jung MR, Park YK, Seon JW, Kim KY, Cheong O, and Ryu SY. Definition and classification of complications of gastrectomy for gastric cancer based on the accordion severity grading system. World J Surg. (2012) 36:2400–11. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1693-y

11. Niu S, Liu Y, Li D, Sheng Y, Zhang Y, Li Z, et al. Effect of indocyanine green near-infrared light imaging technique guided lymph node dissection on short-term clinical efficacy of minimally invasive radical gastric cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1257585. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1257585

12. Pang HY, Liang XW, Chen XL, Zhou Q, Zhao LY, Liu K, et al. Assessment of indocyanine green fluorescence lymphography on lymphadenectomy during minimally invasive gastric cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. (2022) 36:1726–38. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08830-2

13. Zhang Z, Deng C, Guo Z, Liu Y, Qi H, and Li X. Safety and efficacy of indocyanine green near-infrared fluorescent imaging-guided lymph node dissection during robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. (2023) 32:240–8. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2023.2165415

14. Chen QY, Xie JW, Zhong Q, Wang JB, Lin JX, Lu J, et al. Safety and efficacy of indocyanine green tracer-guided lymph node dissection during laparoscopic radical gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. (2020) 155:300–11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.6033

15. Lan YT, Huang KH, Chen PH, Liu CA, Lo SS, Wu CW, et al. A pilot study of lymph node mapping with indocyanine green in robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. SAGE Open Med. (2017) 5:2050312117727444. doi: 10.1177/2050312117727444

16. Kwon IG, Son T, Kim HI, and Hyung WJ. Fluorescent lymphography-guided lymphadenectomy during robotic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. JAMA Surg. (2019) 154:150–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4267

17. Lee S, Song JH, Choi S, Cho M, Kim YM, Kim HI, et al. Fluorescent lymphography during minimally invasive total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an effective technique for splenic hilar lymph node dissection. Surg Endosc. (2022) 36:2914–24. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08584-x

18. Kim KY, Hwang J, Park SH, Cho M, Kim YM, Kim HI, et al. Superior lymph node harvest by fluorescent lymphography during minimally invasive gastrectomy for gastric cancer patients with high body mass index. Gastric Cancer. (2024) 27:622–34. doi: 10.1007/s10120-024-01482-w

19. Cianchi F, Indennitate G, Paoli B, Ortolani M, Lami G, Manetti N, et al. The clinical value of fluorescent lymphography with indocyanine green during robotic surgery for gastric cancer: a matched cohort study. J Gastrointest Surg. (2020) 24:2197–203. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04382-y

20. Jung MK, Cho M, Roh CK, Seo WJ, Choi S, Son T, et al. Assessment of diagnostic value of fluorescent lymphography-guided lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. (2021) 24:515–25. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01121-0

21. Zhang QJ, Cao ZC, Zhu Q, Sun Y, Li RD, Tong JL, et al. Application value of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in guiding sentinel lymph node biopsy diagnosis of gastric cancer: Meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. (2024) 16:1883–93. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i6.1883

22. Tuan NA and Van Du N. Assessment of diagnostic value of indocyanine green for lymph node metastasis in laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: a prospective single-center study. J Gastrointest Surg. (2024) 28:1078–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2024.04.025

23. Chen QY, Zhong Q, Liu ZY, Li P, Lin GT, Zheng QL, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging-guided versus conventional laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: long-term outcomes of a phase 3 randomised clinical trial. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:7413. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-42712-6

24. Senent-Boza A, García-Fernández N, Alarcón-Del Agua I, Socas-Macías M, de Jesús-Gil Á, and Morales-Conde S. Impact of tumor stage and neoadjuvant chemotherapy in fluorescence-guided lymphadenectomy during laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched study in a western center. Surgery. (2023) 175:380–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2023.10.032

Keywords: indocyanine green, gastric cancer, fluorescence laparoscopy, lymph node dissection, prognosis

Citation: Lv C-B, Tong L-Y, Sun Y-Q, Huang R-J, Han H-H, Chen Q-X and Cai L-s (2025) Beneficial impact of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging on lymphadenectomy in laparoscopic total gastrectomy for advanced upper gastric cancer. Front. Oncol. 15:1588048. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1588048

Received: 05 March 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Ulrich Ronellenfitsch, Medical Faculty of the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, GermanyReviewed by:

Serena Martinelli, University of Florence, ItalyEfstahios Kotidis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Rui-Fu Chen, Xiamen Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China

Ji Yoon Jeong, Yonsei University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2025 Lv, Tong, Sun, Huang, Han, Chen and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiu-Xian Chen, bGMyNzU3NTgxMzg4QDEyNi5jb20=; Li-sheng Cai, Y2FpbGlzaGVuZ2Nsc0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors share first authorship

Chen-Bin Lv

Chen-Bin Lv Lin-Yan Tong2†

Lin-Yan Tong2† Yu-Qin Sun

Yu-Qin Sun Li-sheng Cai

Li-sheng Cai