- Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Weihai Municipal Hospital, Weihai, China

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver is a malignant mesenchymal tumor of the liver that predominantly affects children, with exceedingly rare occurrence in adults, and is associated with a poor prognosis. We present a case of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in a previously healthy 45-year-old man admitted to our hospital due to fever. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a cystic-solid mass in the right lobe of the liver, measuring approximately 15 * 13 * 13 cm in size. Imaging diagnosis raised a suspicion of biliary cystadenocarcinoma with hemorrhage. A hepatic resection was successfully performed, and the histologic diagnosis was undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. The patient received a chemotherapy regimen of ifosfamide combined with epirubicin after surgery, and no recurrence was observed after 6 months of follow-up. We herein review the clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features of this rare tumor.

1 Introduction

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is a rare and aggressive liver sarcoma originating from the liver’s mesenchymal tissue (1). Most cases occur in children aged 6 to 10 years, and UESL accounts for less than 1% of liver tumors in adults (2, 3). The early symptoms of UESL are similar to those of liver abscess and cystic liver disease, such as abdominal mass, distension, and pain, which are difficult to diagnose clinically (4). Tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are usually not significantly abnormal (5). The imaging findings of UESL are also non-specific. The right lobe of the liver is a common site of UESL, presenting as a single, large, and well-defined cystic-solid mass (6, 7). Surgical excision and postoperative chemotherapy remain the primary treatments for UESL. However, due to the difficulty of symptom concealment and diagnosis, most patients diagnosed with UESL are in advanced stages of the disease, making them unsuitable for surgical treatment. Therefore, early detection, complete resection, and postoperative adjuvant therapy are the keys to a good prognosis (2, 8).

This case report provides a comprehensive description of the clinical diagnosis and treatment of an adult patient, including imaging, histology, and genetic manifestations, thereby supporting the clinical progress of UESL.

2 Case presentation

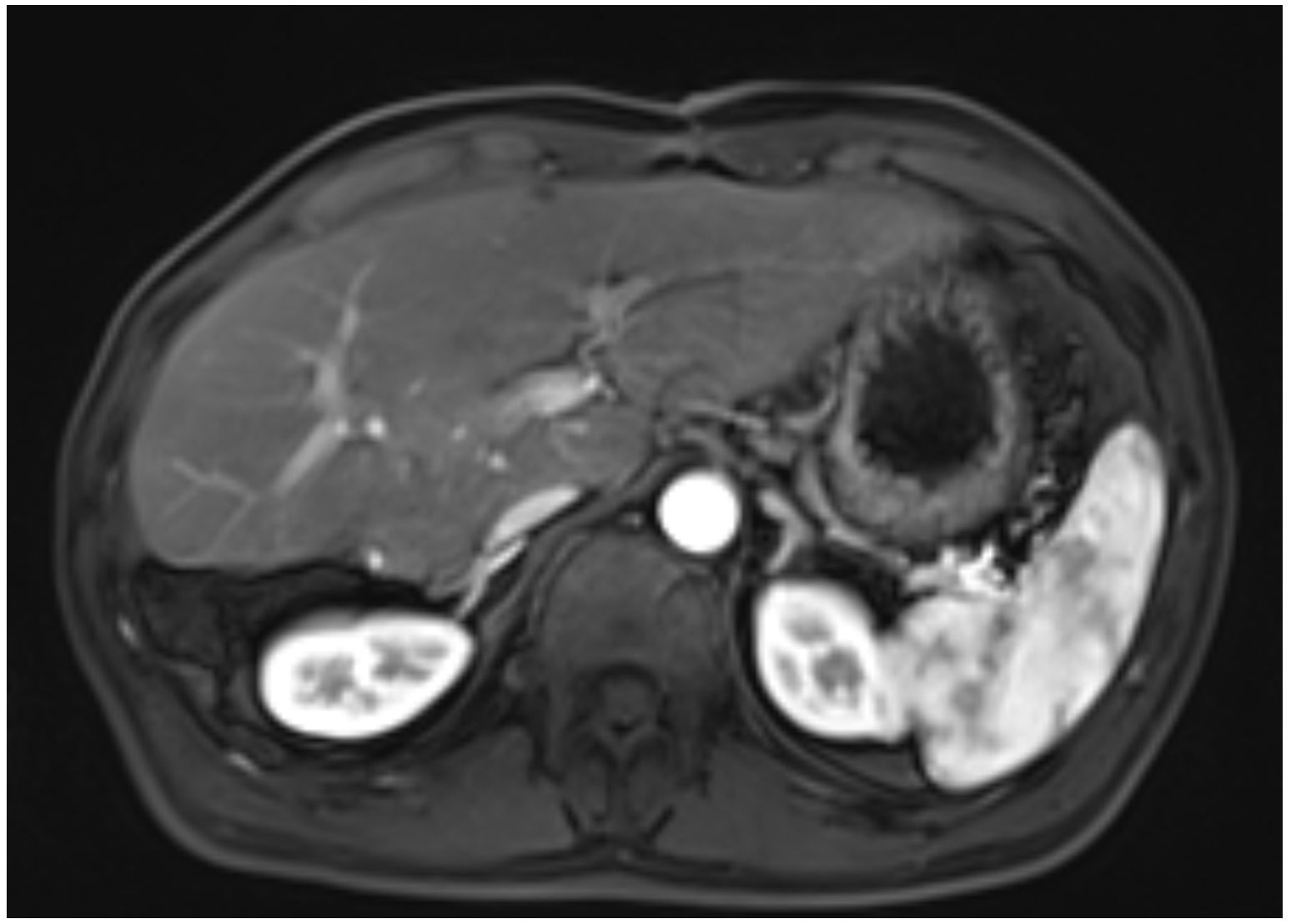

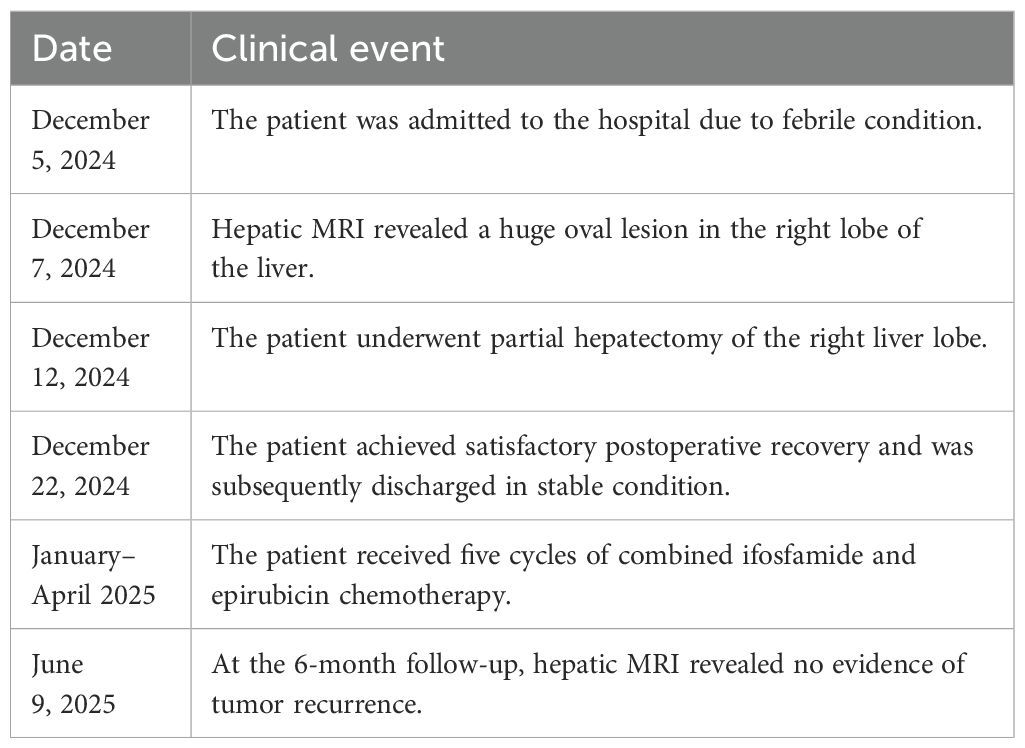

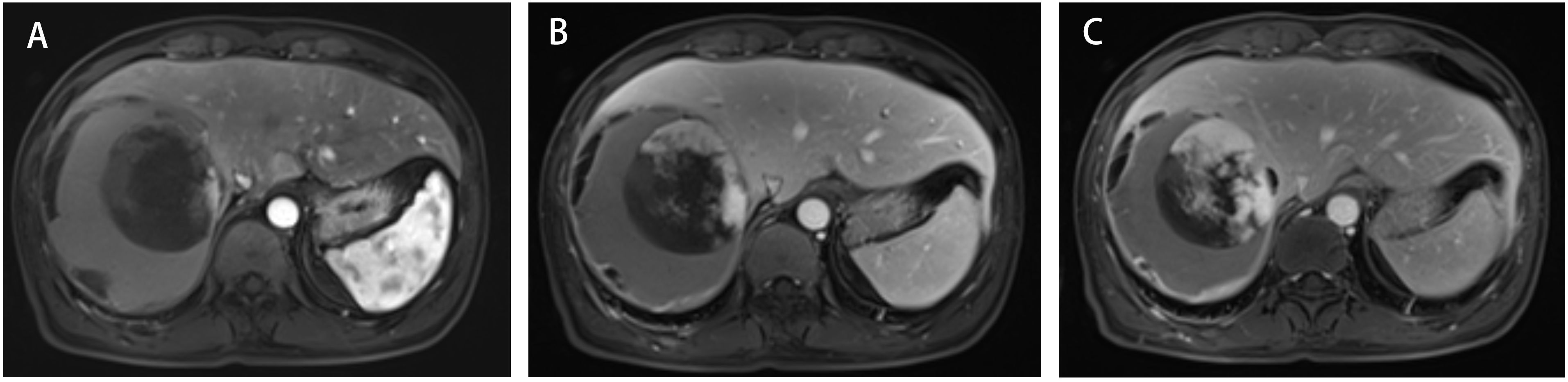

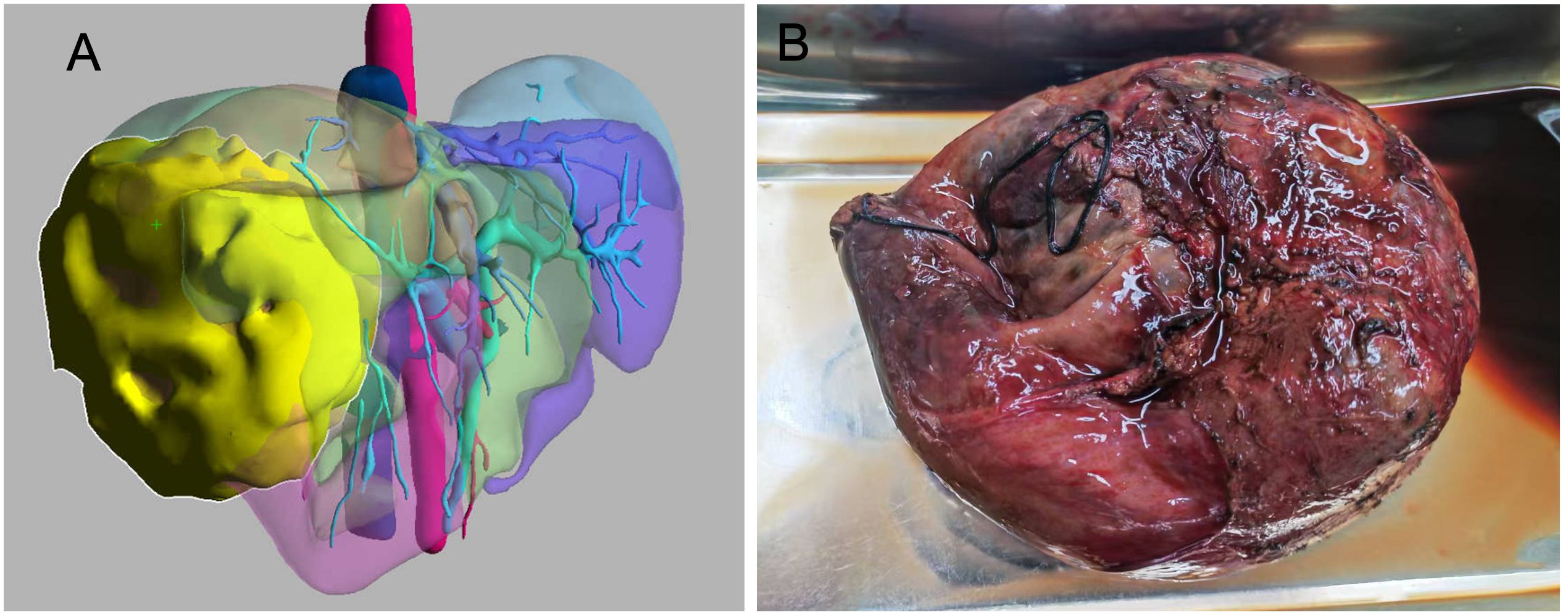

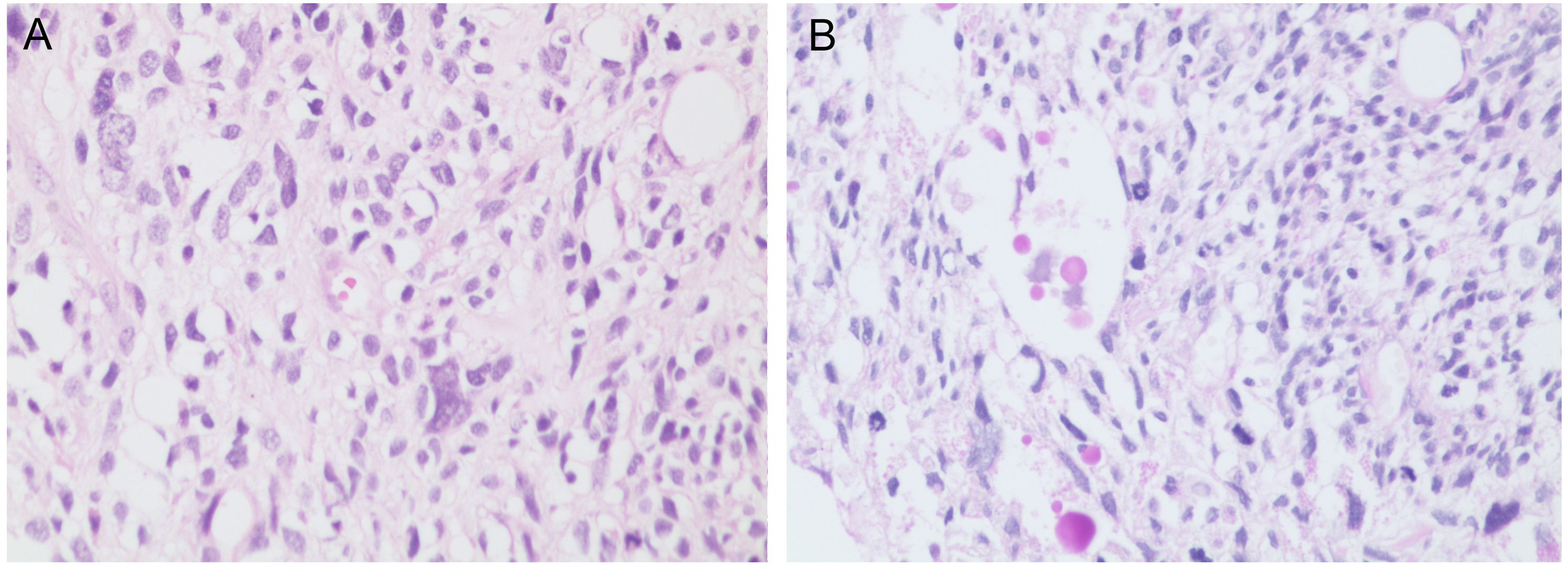

A 45-year-old male patient presented with fever to Weihai Municipal Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University in December 2024. Laboratory examination upon admission showed elevated white blood cell count and hypersensitive C-reactive protein, and no abnormalities were found in the tumor markers (including AFP, CA19-9, and CEA). Physical examination revealed no discernible disparity. The patient had no history of hepatitis B infection, liver cirrhosis, or other malignancies and no family history of disease. Abdominal ultrasound of the patient showed a cystic-solid mass in the right lobe of the liver, measuring approximately 15 * 13 * 13 cm in size, with a thin wall, clear boundary, and internal septa. Color Doppler flow imaging (CDFI) demonstrates sparse peripheral blood flow signals around the nodule. Further enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a huge oval lesion in the right lobe of the liver. T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) showed mixed low signal, and T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) showed mixed high signal. The solid part showed diffusion restriction in diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). After injection of the contrast agent, the solid part of the lesion showed progressive heterogeneous enhancement, especially in the delayed phase (Figure 1). Background liver parenchyma was normal without manifestations of fatty liver or cirrhosis. Imaging diagnosis raised a suspicion of biliary cystadenocarcinoma with hemorrhage. Preoperative assessment showed that the patient’s liver function was classified as Child–Pugh A, and the indocyanine green 15-minute retention rate was 3.3%. The standardized future liver remnant (sFLR), calculated from preoperative three-dimensional reconstruction imaging, was 0.88. Therefore, open liver tumor resection was performed under general anesthesia, and a cystic-solid mass originating from the right lobe of the liver was observed, with an intact capsule. The remaining liver tissue appeared reddish and moist, with no cirrhosis or abnormal nodules. The right posterior lobe of the liver along with the mass was completely resected approximately 1 cm from the left margin of the mass (Figure 2). The tumor demonstrates a variegated cut surface with gray-red and gray-yellow coloration, showing focal cystic changes filled with clear, straw-colored fluid. Pathological examination revealed a fusiform cell tumor with necrosis, hemorrhage, cystic changes, and mitotic images. Some tumor cells contained eosinophilic bodies, which were positive for Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (Figure 3). The results of immunohistochemical (IHC) were as follows: Vimentin (+), CK-pan (+), P16 (+), CD34 (+), Desmin (+), H3K27Me3 (+), P53 (missense mutant), Melan A (−), S-100 (−), SMA (−), CD31 (−), MyoD1 (−), Stat6 (−), and Ki-67 labeling index of 65%. Based on the location, morphology, and immunohistochemical results, the diagnosis tended to be UESL of the liver. Postoperatively, the patient’s liver function showed no significant impairment. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 9 following a smooth recovery. Currently, there is no standardized chemotherapy regimen for UESL. Postoperatively, based on multidisciplinary tumor board consensus and published literature (2, 22), the patient received five cycles of combined ifosfamide and epirubicin chemotherapy administered at 21-day intervals (Table 1). The chemotherapy regimen was well-tolerated by the patient, who maintained excellent compliance throughout the treatment course. At the 6-month follow-up, hepatic MRI revealed no evidence of tumor recurrence (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Three-phase enhanced MRI of the abdomen. (A) The arterial phase. (B) The portal venous phase. (C) The delayed phase.

Figure 2. (A) Preoperative three-dimensional reconstruction imaging (the lesion is highlighted in yellow). (B) Gross photograph of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver.

Figure 3. (A) The tumor is composed of spindle-shaped cells (×200, H&E stain). (B) Some tumor cells contain eosinophilic globules (×200, PAS stain). PAS, Periodic Acid-Schiff.

3 Discussion

UESL is a malignant liver tumor originating from mesenchymal tissue, primarily occurring in children aged 6 to 10 years. It ranks third in incidence among primary malignant liver tumors in children, following hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, and it has also been sporadically reported in adult patients (1, 3). However, this entity is exceptionally rare in adults, constituting less than 1% of primary hepatic neoplasms (9). The non-specific clinical manifestations frequently lead to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment. Adult UESL demonstrates significantly poorer prognosis with a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 48.2%, compared to 84.4% in pediatric cases (10, 11).

The clinical symptoms of UESL are insidious, primarily manifesting as abdominal pain or an epigastric mass, with occasional secondary symptoms such as fever, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. UESL lacks specific serum markers. Although patients with UESL generally do not have underlying liver diseases such as hepatitis or cirrhosis, abnormal liver function may occur due to the compression of surrounding normal liver tissue by the large tumor mass. In cases complicated by intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, or infection, elevated leukocytes may be observed (8). Serum tumor markers in UESL patients are typically negative. In this case, laboratory tests, including tumor markers, showed no abnormal findings, which aligns with previous research findings (12, 13). UESL is predominantly located in the right hepatic lobe, and lesions can be detected via ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or MRI. Typical ultrasound findings reveal a cystic-solid mass with mixed echogenicity, characterized by hyperechoic areas caused by numerous small interfaces within the myxoid matrix (2). In CT images, tumors are displayed as a well-defined unilocular or multilocular hypodense mass. Due to the hydrophilic acidic mucopolysaccharides in the myxoid matrix, which continuously absorb water, CT often indicates fluid density (8, 14). Contrast-enhanced scans show varying degrees of enhancement in the tumor margins and internal solid components. The differences in imaging features between ultrasound and CT can improve preoperative diagnostic accuracy. Notably, the main differential diagnoses for UESL include biliary cystadenocarcinoma, massive hepatocellular carcinoma, mesenchymal hamartoma, and hepatoblastoma. Biliary cystadenocarcinoma predominantly affects middle-aged women, with CT imaging typically revealing multilocular cystic liver lesions characterized by nodular wall projections, irregular wall thickness, and homogeneous enhancement of septations. In contrast, massive hepatocellular carcinoma usually develops in patients with hepatitis-induced cirrhosis, showing significantly elevated AFP levels and CT features of predominantly solid masses containing necrotic areas, demonstrating the classic “wash-in, wash-out” enhancement pattern. Mesenchymal hamartoma occurs primarily in children under 2 years of age, presenting on CT as well-demarcated multilocular cystic lesions with multiple thin septations, smooth walls, and rare soft-tissue components or mural nodules. Hepatoblastoma, mainly affecting children aged 3–5 years without a history of hepatitis or cirrhosis, typically appears on CT as large solid masses frequently exhibiting hemorrhage and necrosis, with amorphous calcifications observed in approximately 50% of cases. While MRI exhibits more distinctive characteristics compared to ultrasound and CT, these imaging modalities are insufficient to differentiate UESL from other space-occupying lesions (7, 13). Preoperative needle biopsy may provide a more definitive diagnosis of UESL, but it carries a risk of tumor spread and should be used cautiously (15, 16). In summary, the preoperative diagnosis of UESL remains challenging, and definitive diagnosis ultimately requires postoperative pathological examination.

The pathological features of UESL include a single, well-demarcated lesion, typically larger than 10 cm, with a fibrous pseudocapsule. The tumor is composed of solid and cystic components. The solid portions exhibit a white or gray-white, fish-flesh-like appearance on cut surfaces, while the cystic areas contain necrotic debris and blood clots (6). Under the microscope, spindle-shaped and stellate tumor cells are diffusely distributed within a myxoid matrix, accompanied by marked cellular atypia and frequent mitotic figures. Additionally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification and diagnostic criteria for tumors of the digestive system, UESL should undergo PAS staining. The presence of PAS-positive eosinophilic bodies within tumor cells and the intercellular stroma serves as a specific pathological indicator of UESL (6). Currently, UESL does not have a specific immunophenotype. Vimentin, CD68, and α1-antitrypsin are typically positive, while the expression of S-100, SMA, Desmin, CD34, Cytokeratin, Myoglobin, and Actin varies (17, 18). These findings suggest that the tumor cells originate from primitive mesenchymal cells. Most immunohistochemical tests are primarily used to exclude other diagnoses. The pathogenesis of UESL is unclear. Given that UESL shares chromosomal abnormalities with mesenchymal hamartoma, some researchers hypothesize that UESL may arise through malignant transformation of mesenchymal hamartoma. Molecular characterization reveals recurrent abnormalities at the 19q13.4 locus, including balanced translocations t(11;19)(q13;q13.4) and t(15;19)(q15;q13.4). Tumor protein 53 (TP53) mutations have also been identified in a subset of cases. TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene whose mutations lead to loss of apoptotic control and impaired DNA repair, thereby increasing the risk of tumorigenesis and progression. In this case, the tumor cells demonstrated diffusely strong positive expression of TP53. However, definitive genetic testing could not be performed due to the patient’s financial constraints (20, 21).

UESL is a highly malignant tumor characterized by rapid progression and aggressive invasiveness. It is often diagnosed at an advanced stage with a large tumor volume. Historically, treatment with surgical resection alone yielded poor outcomes, with high rates of postoperative recurrence and metastasis, resulting in a 5-year survival rate below 37.5% (8, 19). In recent years, advancements in comprehensive cancer therapy have significantly improved the prognosis of UESL patients through a combination of surgical resection and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Although no standardized chemotherapy regimen exists, multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of ifosfamide combined with epirubicin in treating UESL, markedly enhancing overall survival rates (22). The patient in this case was treated with this chemotherapy regimen and showed no signs of tumor recurrence or metastasis during a 6-month follow-up. However, the 6-month follow-up period is insufficient to draw meaningful conclusions regarding long-term prognosis. We will continue to monitor this patient’s clinical course to generate more robust survival data for UESL treatment evaluation.

4 Conclusion

Given the insidious clinical presentation of UESL, the patient already had a large tumor volume at initial diagnosis. However, through aggressive surgical intervention followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, favorable short-term outcomes were achieved. The preoperative diagnosis of UESL remains challenging, with high misdiagnosis rates. For suspected cases, multidisciplinary collaboration is strongly recommended. Complete tumor resection combined with systemic therapy appears crucial for long-term survival, although the optimal treatment standards and efficacy require further investigation through multicenter studies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Weihai Municipal Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SL: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LXB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. XL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. LB: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and his family.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1599953/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Shi Y, Rojas Y, Zhang W, Beierle EA, Doski JJ, Goldfarb M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in children with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: A report from the National Cancer Database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2017) 64:e26272. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26272

2. Huang Y, He X, Shangguan L, Zhou Y, Zhang L, and Wu Y. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver masquerading as a cystadenoma in a young adult: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2024) 18:517. doi: 10.1186/s13256-024-04867-8

3. Weinberg AG and Finegold MJ. Primary hepatic tumors of childhood. Hum Pathol. (1983) 14:512–37. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80005-7

4. Shu B, Gong L, Zhuang X, Cao L, Yan Z, and Yang S. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in adults: Retrospective analysis of a case series and systematic review. Oncol Lett. (2020) 20:102. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11963

5. Lin W-Y, Wu K-H, Chen C-Y, Guo B-C, Chang Y-J, Lin M-J, et al. Treatment of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in children. Cancers. (2024) 16:897. doi: 10.3390/cancers16050897

6. Putra J and Ornvold K. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: A concise review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2015) 139:269–73. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0463-RS

7. Jiang P, Jiao Y, Niu CY, and Liu YH. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver with epithelioid features in an adult patient. Medicine. (2021) 100:e28265. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000028265

8. Zhang C, Jia CJ, Xu C, Sheng QJ, Dou XG, and Ding Y. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: Clinical characteristics and outcomes. World J Clin cases. (2020) 8:4763–72. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4763

9. Noguchi K, Yokoo H, Nakanishi K, Kakisaka T, Tsuruga Y, Kamachi H, et al. A long-term survival case of adult undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver. World J Surg Oncol. (2012) 10:65. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-65

10. Ziogas IA, Zamora IJ, Lovvorn Iii HN, Bailey CE, and Alexopoulos SP. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in children versus adults: A national cancer database analysis. Cancers. (2021) 13:2918. doi: 10.3390/cancers13122918

11. Endo YK, Fujio A, Murakami K, Sasaki K, Miyazawa K, Kashiwadate T, et al. Long-term survival of an adult patient with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver with multidisciplinary treatment: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. (2022) 8:85. doi: 10.1186/s40792-022-01436-3

12. Chen JH, Lee CH, Wei CK, Chang SM, and Yin WY. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver with focal osteoid picture—A case report. Asian J Surg. (2013) 36:174–8. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2012.06.012

13. Li X-W. Undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma in adults: A report of four cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. (2010) 16:4725–32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4725

14. Moon WK, Kim WS, Kim IO, Yeon KM, Yu IK, Choi BI, et al. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: US and CT findings. Pediatr Radiol. (1994) 24:500–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02015012

15. Naveen K, Sameer V, Palash JD, Kochhar R, Srinivasan R, and Khandelwal N. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver in an adult masquerading as complicated hydatid cyst. Ann Hepatol. (2011) 10:81–3. doi: 10.1016/S1665-2681(19)31592-3

16. Geel JA, Loveland JA, Pitcher GJ, Beale P, Kotzen J, and Poole JE. Management of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in children: A case series and management review. South Afr Med J. (2013) 103:728–31. doi: 10.7196/samj.6058

17. Kiani B, Ferrell LD, Qualman S, and Frankel WL. Immunohistochemical analysis of embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. (2006) 14:193–7. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000173052.37673.95

18. Zheng JM, Tao X, Xu AM, Chen XF, Wu MC, and Zhang SH. Primary and recurrent embryonal sarcoma of the liver: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Histopathology. (2007) 51:195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02746.x

19. Cao Q, Ye Z, Chen S, Liu N, Li S, and Liu F. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver: a multi-institutional experience with 9 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2014) 7:8647–56.

20. Mathews J, Duncavage EJ, and Pfeifer JD. Characterization of translocations in mesenchymal hamartoma and undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. Exp Mol Pathol. (2013) 95:319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.09.006

21. Setty BA, Jinesh GG, Arnold M, Pettersson F, Cheng CH, Cen L, et al. The genomic landscape of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver is typified by C19MC structural rearrangement and overexpression combined with TP53 mutation or loss. PLoS Genet. (2020) 16:e1008642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008642

Keywords: undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma, liver, long-term survival, multidisciplinary treatment, adult

Citation: Li S, Bao L, Li X and Bai L (2025) Case Report: Undifferentiated embryonic sarcoma of an adult liver. Front. Oncol. 15:1599953. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1599953

Received: 25 March 2025; Accepted: 26 June 2025;

Published: 25 July 2025.

Edited by:

Lei Gong, Capital Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Konstantin Semash, Independent Researcher, Tashkent, UzbekistanMichel Meyers, Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Marwan Idrees, Royal Perth Hospital, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Li, Bao, Li and Bai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shengyong Li, d2hsc3lAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Shengyong Li

Shengyong Li Lexin Bao

Lexin Bao Xiujun Li

Xiujun Li Liang Bai

Liang Bai