Abstract

Background:

Patients with endometrial cancer bone metastases (ECBM) are clinically rare and have a poor prognosis, including a higher incidence of early death (survival ≤ 3 months). Currently, no practical tools exist to predict early mortality in these patients. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop clinically applicable predictive models, such as nomograms, for individualized assessment of early death risk in ECBM.

Methods:

Relevant clinical and pathological data for ECBM patients from the SEER database (2010-2021). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify risk factors associated with early death in ECBM patients and to construct prognostic nomograms. ROC analysis, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to assess the predictive accuracy and clinical utility of the nomogram model.

Results:

A total of 1,201 ECBM patients were found in the SEER database. After applying strict exclusion criteria, 769 patients were finally included in this study. Patients were randomly divided into training and validation cohorts in a 7:3 ratio. The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed several independent predictive factors for early death. For both overall early death (OED) and cancer-specific early death (CSED), protective factors included surgery (OED: OR = 0.22, 95%CI: 0.12-0.41, p<0.001; CSED: OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18-0.61, p<0.001) and chemotherapy (OED: OR = 0.11, 95%CI: 0.06-0.18, p<0.001; CSED: OR = 0.14, 95%CI: 0.09-0.24, p<0.001). Brain metastases increased risk (OED: OR = 2.98, 95%CI: 1.29-6.87, p=0.01; CSED: OR = 2.20, 95%CI: 1.04-4.79, p=0.047). Compared to 0–9 days, longer time from diagnosis to treatment showed protective associations: 10–27 days (OED: OR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.27-0.98, p=0.042) and ≥28 days (OED: OR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.12-0.44, p<0.001; CSED: OR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.16-0.56, p<0.001). Regarding histological type, compared to endometrioid subtype, sarcomatous subtype significantly increased OED risk (OR = 3.04, 95%CI: 1.40-6.57, p=0.005), while radiotherapy reduced CSED risk (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.33-0.92, p=0.022). Based on these variables, nomograms were developed to predict the risk of early death. The ROC curve confirmed the model’s high predictive accuracy, while the calibration curve showed strong alignment between predicted and actual survival. DCA further demonstrated its clinical utility.

Conclusion:

In this study, we developed robust nomogram models to predict the probability of early death in ECBM patients.

1 Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most common malignant tumors of the female reproductive system, with an increasing incidence and mortality rate each year. According to the American Cancer Society, in 2022, the number of new cases in the United States rose to 65,950, resulting in 12,550 deaths and posing a significant threat to women’s health (1, 2). Although most EC patients are diagnosed early and have a favorable prognosis, with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 80%, those advanced or recurrent patients have a poor prognosis. Distant metastasis is the primary cause of death in EC patients, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 20% (3, 4). Bone and brain are the least common distant metastases organs for EC patients, with a median survival time of only 4 months for ECBM patients (5).

Currently, the TNM staging system established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is the standard tool for predicting survival rates in EC patients. However, its predictive effectiveness significantly diminishes when applied to metastatic disease (6). Some ECBM patients die within 3 months of diagnosis. To date, there have been relatively few reports on ECBM, and no prognostic models specifically designed to predict early death have been established. Recent studies have indicated that nomograms offer a convenient and accurate tool for assessing the prognosis of cancer (7).

This study utilizes a large sample of clinical data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute to analyze clinical and pathological factors associated with prognosis in ECBM patients. Nomogram models were constructed to predict the risk of early death (8). This model is designed to enhance the assessment of prognosis in ECBM patients, enabling clinicians to identify high-risk individuals timely, and develop personalized treatment plans, ultimately aiming to extend life expectancy and improve patients’ quality of life.

2 Methods

Data from 769 ECBM patients were extracted from the SEER database (URL: https://seer.cancer.gov/) covering the period from 2010 to 2021. The study extracted basic clinical and pathological information as well as treatment methods for the patients. Authorization for access to and use of the SEER database has been obtained for this research. Given the anonymized nature and publicly accessible data within the SEER database, this study does not require additional approval from an institutional ethics committee. This research adheres to the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments and similar ethical guidelines.

2.1 Patient cohorts

The clinical information of 769 patients was extracted by the SEER*Stat database (version 8.4.4). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) pathological diagnosis of endometrial cancer; (2) with bone metastasis; (3) only primary cancer; (4) diagnosis from 2010 to 2021. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with unknown survival time; (2) patients with unspecified histological type; (3) patients with multiple primary tumors; and (4) patients with missing racial information. The selection process of the ECBM patients is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The flow chart of ECBM patient enrollment.

2.2 Data collection

The exclusion studies follow the criteria: (a) study children with cancer and cancer patients undergoing treatment; (b) intervention studies combining exercise with cognitive therapy, physiotherapy, massaging, diet, or medication; (c) studies that excluded trials with no control group; (d) Endpoints that reported cancer-specific scales and excluded non-cancer survivors’ HRQoL scales. The demographic information includes age, race, marital status, tumor size, histological grade, histological type, TNM staging, metastases, the time from diagnosis of ECBM to treatment, the year of diagnosis, surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

According to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3), metastatic EC patients were divided into three histological subtypes: endometrioid (codes 8380, 8382), non-endometrioid (codes 8000, 8010, 8013, 8020, 8041, 8045, 8046, 8050, 8070, 8140, 8246, 8255, 8260, 8263, 8310, 8323, 8441, 8460, 8461, 8480, 8560, 8570, 8574), and sarcomatous (codes 8800, 8802, 8805, 8890, 8900, 8902, 8930, 8933, 8935, 8950, 8980, 9102). Tumor grading was defined as Grade I (well-differentiated), Grade II (moderately differentiated), Grade III (poorly differentiated), and Grade IV (undifferentiated).

Based on previous studies, OED was defined as death from any cause occurring within three months (9). CSED refers to death resulting from ECBM within the same three-month period. The study endpoints were OED and CSED. Survival time was calculated from the date of initial diagnosis of ECBM.

2.3 Statistical analyses

The eligible patients were randomly divided into a training cohort (537 patients) and a validation cohort (232 patients) in a 7:3 ratio. Statistical analyses were conducted by using SPSS 27.0 and R 4.4.1 software. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages), and intergroup comparisons were performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Ordered categorical variables were compared using the rank-sum test. The X-tile software was utilized to determine the optimal cutoff values for age, tumor size, and time from diagnosis to treatment for ECBM patients. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent risk factors for OED and CSED within the training cohort. Nomograms were constructed to predict OED and CSED. The predictive models’ discrimination and diagnostic performance were assessed using ROC curves and AUC values. The calibration and clinical applicability of the models were evaluated through calibration curves and DCA analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Determine the age, tumor size, and optimal cutoff from diagnosis to treatment based on X-tile

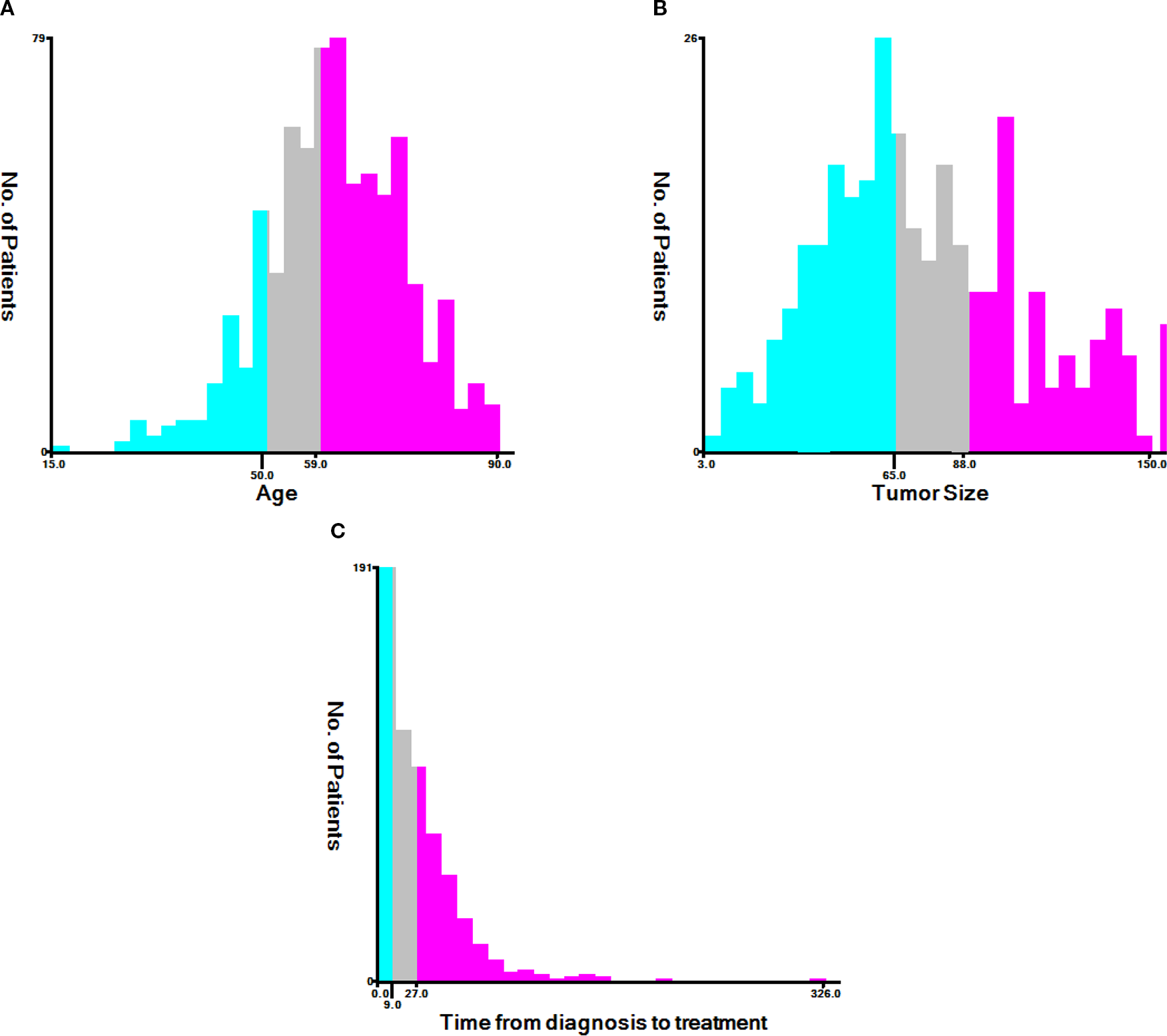

According to X-tile, the optimal cutoff values for age were 50 years old and 59 years old. Patients were categorized into groups of ≤50, 51–59, and ≥60 years old (Figure 2A). The optimal cutoff values for tumor size were identified as 65 mm and 88 mm, with patients grouped as ≤ 65 mm, 66–88 mm, and ≥ 89 mm (Figure 2B). Additionally, the optimal cutoff values for time from diagnosis to treatment were established at 9 days and 27 days, resulting in patient groupings of ≤9 days, 10–27 days, and ≥28 days (Figure 2C).

Figure 2

The X-tile analysis. (A) Age, (B) tumor size, (C) time from diagnosis to treatment.

3.2 Epidemiological and clinicopathological features

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 769 ECBM patients were retrospectively included in this study. As shown in Table 1, 41.5% (319/769) of the ECBM patients died within three months, with 38.9% (299/769) dying from ECBM, and most of the patients were White (80.6%). Lung metastases (55.5%) were more common than brain metastases (10.0%) and liver metastases (31.7%). The most common histological type was non-endometrioid (58.0%), followed by the endometrioid (27.0%) and sarcomatous (15.0%). Additionally, 32.0% of patients received radiotherapy, 23.8% underwent chemotherapy, while only 17.2% received surgical treatment. The patients were randomly divided into a training cohort (n = 537) and an internal validation cohort (n = 232) in a 7:3 ratio. Comparisons of demographic and clinicopathological parameters between the training and validation cohorts showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05), indicating that the cohorts were suitable for subsequent analyses (Table 2).

Table 1

| Name | Levels | No (N=450) | Overall early death (N=319) | Cancer-specific early death (N=299) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-50 | 70 (15.6%) | 36 (11.3%) | 35 (11.7%) |

| 51-59 | 116 (25.8%) | 81 (25.4%) | 73 (24.4%) | |

| >=60 | 264 (58.7%) | 202 (63.3%) | 191 (63.9%) | |

| Race | White | 361 (80.2%) | 257 (80.6%) | 243 (81.3%) |

| Black | 42 (9.3%) | 23 (7.2%) | 22 (7.4%) | |

| Other | 47 (10.4%) | 39 (12.2%) | 34 (11.4%) | |

| Marital.status | Married | 218 (48.4%) | 157 (49.2%) | 148 (49.5%) |

| Unmarried | 216 (48%) | 148 (46.4%) | 138 (46.2%) | |

| unknown | 16 (3.6%) | 14 (4.4%) | 13 (4.3%) | |

| Grade | I | 9 (2%) | 4 (1.3%) | 4 (1.3%) |

| II | 43 (9.6%) | 12 (3.8%) | 12 (4%) | |

| III | 137 (30.4%) | 78 (24.5%) | 71 (23.7%) | |

| IV | 65 (14.4%) | 41 (12.9%) | 39 (13%) | |

| unknown | 196 (43.6%) | 184 (57.7%) | 173 (57.9%) | |

| T | T1 | 49 (10.9%) | 27 (8.5%) | 25 (8.4%) |

| T2 | 41 (9.1%) | 19 (6%) | 19 (6.4%) | |

| T3 | 193 (42.9%) | 90 (28.2%) | 80 (26.8%) | |

| T4 | 40 (8.9%) | 41 (12.9%) | 38 (12.7%) | |

| unknown | 127 (28.2%) | 142 (44.5%) | 137 (45.8%) | |

| N | N0 | 128 (28.4%) | 89 (27.9%) | 80 (26.8%) |

| N1 | 152 (33.8%) | 106 (33.2%) | 100 (33.4%) | |

| N3 | 92 (20.4%) | 53 (16.6%) | 50 (16.7%) | |

| unknown | 78 (17.3%) | 71 (22.3%) | 69 (23.1%) | |

| Surgery | No | 271 (60.2%) | 264 (82.8%) | 248 (82.9%) |

| Yes | 179 (39.8%) | 55 (17.2%) | 51 (17.1%) | |

| Radiation | No/Unknown | 219 (48.7%) | 217 (68%) | 205 (68.6%) |

| Yes | 231 (51.3%) | 102 (32%) | 94 (31.4%) | |

| Chemotherapy | No/Unknown | 106 (23.6%) | 243 (76.2%) | 228 (76.3%) |

| Yes | 344 (76.4%) | 76 (23.8%) | 71 (23.7%) | |

| Tumor.Size | 3-65 | 101 (22.4%) | 43 (13.5%) | 40 (13.4%) |

| 66-88 | 42 (9.3%) | 23 (7.2%) | 21 (7%) | |

| 90-150 | 56 (12.4%) | 43 (13.5%) | 40 (13.4%) | |

| unknown | 251 (55.8%) | 210 (65.8%) | 198 (66.2%) | |

| Brain.metastasis | No | 417 (92.7%) | 277 (86.8%) | 261 (87.3%) |

| Yes | 23 (5.1%) | 32 (10%) | 29 (9.7%) | |

| Unknown | 10 (2.2%) | 10 (3.1%) | 9 (3%) | |

| Liver.metastasis | No | 330 (73.3%) | 209 (65.5%) | 196 (65.6%) |

| Yes | 117 (26%) | 101 (31.7%) | 95 (31.8%) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.7%) | 9 (2.8%) | 8 (2.7%) | |

| Lung.metastasis | No | 232 (51.6%) | 132 (41.4%) | 121 (40.5%) |

| Yes | 207 (46%) | 177 (55.5%) | 168 (56.2%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (2.4%) | 10 (3.1%) | 10 (3.3%) | |

| Time.from.diagnosis.to.treatment | 0-9 | 88 (19.6%) | 75 (23.5%) | 69 (23.1%) |

| 10-27 | 124 (27.6%) | 62 (19.4%) | 59 (19.7%) | |

| 28-326 | 201 (44.7%) | 51 (16%) | 47 (15.7%) | |

| unknown | 37 (8.2%) | 131 (41.1%) | 124 (41.5%) | |

| Year.of.diagnosis | 2010-2015 | 201 (44.7%) | 134 (42%) | 124 (41.5%) |

| 2016-2021 | 249 (55.3%) | 185 (58%) | 175 (58.5%) | |

| Histology | endometrioid subtype | 156 (34.7%) | 86 (27%) | 79 (26.4%) |

| non-endometrioid subtype | 236 (52.4%) | 185 (58%) | 177 (59.2%) | |

| sarcoma subtype | 58 (12.9%) | 48 (15%) | 43 (14.4%) |

Epidemiological and clinicopathological characteristics of ECBM patients.

(Grade: I (highly differentiated), II (moderately differentiated), III/IV (poorly differentiated or undifferentiated)).

Table 2

| Name | Levels | Training (N=537) | Validation (N=232) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-50 | 77 (14.3%) | 29 (12.5%) | .793 |

| 51-59 | 137 (25.5%) | 60 (25.9%) | ||

| >=60 | 323 (60.1%) | 143 (61.6%) | ||

| Race | White | 424 (79%) | 194 (83.6%) | .209 |

| Black | 46 (8.6%) | 19 (8.2%) | ||

| Other | 67 (12.5%) | 19 (8.2%) | ||

| Marital.status | Married | 266 (49.5%) | 109 (47%) | .644 |

| Unmarried | 252 (46.9%) | 112 (48.3%) | ||

| unknown | 19 (3.5%) | 11 (4.7%) | ||

| Grade | I | 11 (2%) | 2 (0.9%) | .649 |

| II | 38 (7.1%) | 17 (7.3%) | ||

| III | 146 (27.2%) | 69 (29.7%) | ||

| IV | 78 (14.5%) | 28 (12.1%) | ||

| unknown | 264 (49.2%) | 116 (50%) | ||

| T | T1 | 49 (9.1%) | 27 (11.6%) | .136 |

| T2 | 43 (8%) | 17 (7.3%) | ||

| T3 | 186 (34.6%) | 97 (41.8%) | ||

| T4 | 63 (11.7%) | 18 (7.8%) | ||

| unknown | 196 (36.5%) | 73 (31.5%) | ||

| N | N0 | 156 (29.1%) | 61 (26.3%) | .172 |

| N1 | 176 (32.8%) | 82 (35.3%) | ||

| N3 | 93 (17.3%) | 52 (22.4%) | ||

| unknown | 112 (20.9%) | 37 (15.9%) | ||

| Surgery | No | 380 (70.8%) | 155 (66.8%) | .313 |

| Yes | 157 (29.2%) | 77 (33.2%) | ||

| Radiation | No/Unknown | 312 (58.1%) | 124 (53.4%) | .265 |

| Yes | 225 (41.9%) | 108 (46.6%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | No/Unknown | 244 (45.4%) | 105 (45.3%) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 293 (54.6%) | 127 (54.7%) | ||

| Tumor.Size | 3-65 | 102 (19%) | 42 (18.1%) | .507 |

| 66-88 | 41 (7.6%) | 24 (10.3%) | ||

| 90-150 | 66 (12.3%) | 33 (14.2%) | ||

| unknown | 328 (61.1%) | 133 (57.3%) | ||

| Brain.metastasis | No | 483 (89.9%) | 211 (90.9%) | .359 |

| Yes | 42 (7.8%) | 13 (5.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 12 (2.2%) | 8 (3.4%) | ||

| Liver.metastasis | No | 371 (69.1%) | 168 (72.4%) | .595 |

| Yes | 158 (29.4%) | 60 (25.9%) | ||

| Unknown | 8 (1.5%) | 4 (1.7%) | ||

| Lung.metastasis | No | 245 (45.6%) | 119 (51.3%) | .301 |

| Yes | 278 (51.8%) | 106 (45.7%) | ||

| Unknown | 14 (2.6%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| Time.from.diagnosis.to.treatment | 0-9 | 116 (21.6%) | 47 (20.3%) | .447 |

| 10-27 | 121 (22.5%) | 65 (28%) | ||

| 28-326 | 180 (33.5%) | 72 (31%) | ||

| unknown | 120 (22.3%) | 48 (20.7%) | ||

| Year.of.diagnosis | 2010-2015 | 237 (44.1%) | 98 (42.2%) | .684 |

| 2016-2021 | 300 (55.9%) | 134 (57.8%) | ||

| Histology | endometrioid subtype | 171 (31.8%) | 71 (30.6%) | .934 |

| non-endometrioid subtype | 293 (54.6%) | 128 (55.2%) | ||

| sarcoma subtype | 73 (13.6%) | 33 (14.2%) |

The comparison of characteristics of ECBM patients in the training and validation cohorts.

3.3 Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis

Univariate analysis revealed that surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, brain metastasis, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, time from diagnosis to treatment, and histological type were significantly associated with OED (all p<0.05). Similarly, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, brain metastasis, lung metastasis, liver metastasis, and time from diagnosis to treatment were significantly associated with CSED (all p<0.05).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified independent predictive factors for early death. For OED, protective factors included surgery (OR = 0.22, 95%CI: 0.12-0.41, p<0.001) and chemotherapy (OR = 0.11, 95%CI: 0.06-0.18, p<0.001). Brain metastasis was associated with increased risk (OR = 2.98, 95%CI: 1.29-6.87, p=0.01). Interestingly, compared to patients treated within 9 days, longer time from diagnosis to treatment was associated with reduced risk: 10–27 days (OR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.27-0.98, p=0.042) and ≥28 days (OR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.12-0.44, p<0.001). Regarding histological type, using endometrioid as reference, the sarcomatous subtype significantly increased OED risk (OR = 3.04, 95%CI: 1.40-6.57, p=0.005), while non-endometrioid subtype showed no significant difference.

For CSED, protective factors included surgery (OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.18-0.61, p<0.001), chemotherapy (OR = 0.14, 95%CI: 0.09-0.24, p<0.001), and radiotherapy (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.33-0.92, p=0.022). Brain metastasis increased risk (OR = 2.20, 95%CI: 1.04-4.79, p=0.047). Similar to OED, longer time from diagnosis to treatment (≥28 days) was associated with reduced CSED risk (OR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.16-0.56, p<0.001). The paradoxical protective effect of longer time to treatment may reflect immortal time bias or selection of patients with better performance status who could afford treatment delays (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3

| Dependent: overall early death | 0 (N=309) | 1 (N=228) | OR (95%CI) (univariable) | OR (95%CI) (multivariable) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-50 | 46 (14.9%) | 31 (13.6%) | ||

| 51-59 | 86 (27.8%) | 51 (22.4%) | 0.88 (0.50-1.56, p=.661) | ||

| >=60 | 177 (57.3%) | 146 (64%) | 1.22 (0.74-2.03, p=.433) | ||

| Race | White | 242 (78.3%) | 182 (79.8%) | ||

| Black | 30 (9.7%) | 16 (7%) | 0.71 (0.38-1.34, p=.290) | ||

| Other | 37 (12%) | 30 (13.2%) | 1.08 (0.64-1.81, p=.776) | ||

| Marital.status | Married | 156 (50.5%) | 110 (48.2%) | ||

| Unmarried | 144 (46.6%) | 108 (47.4%) | 1.06 (0.75-1.51, p=.729) | ||

| unknown | 9 (2.9%) | 10 (4.4%) | 1.58 (0.62-4.01, p=.340) | ||

| Grade | I | 8 (2.6%) | 3 (1.3%) | ||

| II | 30 (9.7%) | 8 (3.5%) | 0.71 (0.15-3.31, p=.664) | ||

| III | 95 (30.7%) | 51 (22.4%) | 1.43 (0.36-5.63, p=.608) | ||

| IV | 48 (15.5%) | 30 (13.2%) | 1.67 (0.41-6.78, p=.475) | ||

| unknown | 128 (41.4%) | 136 (59.6%) | 2.83 (0.74-10.91, p=.130) | ||

| T | T1 | 30 (9.7%) | 19 (8.3%) | ||

| T2 | 30 (9.7%) | 13 (5.7%) | 0.68 (0.29-1.63, p=.392) | 0.63 (0.21-1.90, p=.415) | |

| T3 | 126 (40.8%) | 60 (26.3%) | 0.75 (0.39-1.44, p=.391) | 0.60 (0.26-1.39, p=.233) | |

| T4 | 34 (11%) | 29 (12.7%) | 1.35 (0.63-2.88, p=.442) | 0.99 (0.37-2.64, p=.979) | |

| unknown | 89 (28.8%) | 107 (46.9%) | 1.90 (1.00-3.60, p=.050) | 0.66 (0.28-1.53, p=.330) | |

| N | N0 | 93 (30.1%) | 63 (27.6%) | ||

| N1 | 101 (32.7%) | 75 (32.9%) | 1.10 (0.71-1.70, p=.681) | ||

| N3 | 59 (19.1%) | 34 (14.9%) | 0.85 (0.50-1.44, p=.549) | ||

| unknown | 56 (18.1%) | 56 (24.6%) | 1.48 (0.90-2.41, p=.119) | ||

| Surgery | No | 189 (61.2%) | 191 (83.8%) | ||

| Yes | 120 (38.8%) | 37 (16.2%) | 0.31 (0.20-0.46, p<.001) | 0.22 (0.12-0.41, p<.001) | |

| Radiation | No/Unknown | 161 (52.1%) | 151 (66.2%) | ||

| Yes | 148 (47.9%) | 77 (33.8%) | 0.55 (0.39-0.79, p=.001) | 0.59 (0.35-1.00, p=.051) | |

| Chemotherapy | No/Unknown | 72 (23.3%) | 172 (75.4%) | ||

| Yes | 237 (76.7%) | 56 (24.6%) | 0.10 (0.07-0.15, p<.001) | 0.11 (0.06-0.18, p<.001) | |

| Tumor.Size | 3-65 | 70 (22.7%) | 32 (14%) | ||

| 66-88 | 26 (8.4%) | 15 (6.6%) | 1.26 (0.59-2.70, p=.549) | 1.81 (0.65-5.04, p=.258) | |

| 90-150 | 39 (12.6%) | 27 (11.8%) | 1.51 (0.79-2.89, p=.207) | 1.21 (0.53-2.78, p=.648) | |

| unknown | 174 (56.3%) | 154 (67.5%) | 1.94 (1.21-3.10, p=.006) | 1.04 (0.56-1.93, p=.905) | |

| Brain.metastasis | No | 286 (92.6%) | 197 (86.4%) | ||

| Yes | 17 (5.5%) | 25 (11%) | 2.13 (1.12-4.06, p=.021) | 2.98 (1.29-6.87, p=.010) | |

| Unknown | 6 (1.9%) | 6 (2.6%) | 1.45 (0.46-4.57, p=.524) | 0.21 (0.01-3.60, p=.281) | |

| Liver.metastasis | No | 227 (73.5%) | 144 (63.2%) | ||

| Yes | 81 (26.2%) | 77 (33.8%) | 1.50 (1.03-2.18, p=.035) | 1.59 (0.96-2.63, p=.071) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3%) | 7 (3.1%) | 11.03 (1.34-90.62, p=.025) | 23.07 (0.55-962.35, p=.099) | |

| Lung.metastasis | No | 154 (49.8%) | 91 (39.9%) | ||

| Yes | 148 (47.9%) | 130 (57%) | 1.49 (1.05-2.11, p=.026) | 1.17 (0.74-1.85, p=.504) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.3%) | 7 (3.1%) | 1.69 (0.58-4.98, p=.339) | 0.58 (0.10-3.19, p=.527) | |

| Time.from.diagnosis.to.treatment | 0-9 | 58 (18.8%) | 58 (25.4%) | ||

| 10-27 | 82 (26.5%) | 39 (17.1%) | 0.48 (0.28-0.81, p=.006) | 0.51 (0.27-0.98, p=.042) | |

| 28-326 | 142 (46%) | 38 (16.7%) | 0.27 (0.16-0.45, p<.001) | 0.23 (0.12-0.44, p<.001) | |

| unknown | 27 (8.7%) | 93 (40.8%) | 3.44 (1.96-6.04, p<.001) | 0.69 (0.30-1.55, p=.366) | |

| Year.of.diagnosis | 2010-2015 | 142 (46%) | 95 (41.7%) | ||

| 2016-2021 | 167 (54%) | 133 (58.3%) | 1.19 (0.84-1.68, p=.323) | ||

| Histology | endometrioid subtype | 110 (35.6%) | 61 (26.8%) | ||

| non-endometrioid subtype | 163 (52.8%) | 130 (57%) | 1.44 (0.98-2.12, p=.067) | 1.42 (0.85-2.37, p=.184) | |

| sarcoma subtype | 36 (11.7%) | 37 (16.2%) | 1.85 (1.06-3.23, p=.029) | 3.04 (1.40-6.57, p=.005) |

Univariate and multivariate Logistic regression analysis of OED in the ECBM patients.

((0: survival > 3 months; 1: survival ≤3 months); (OR: Odds Ratio; 95%CI: 95% Confidence Interval)). OR <1 indicates protective association (reduced risk of early death); OR >1 indicates adverse association (increased risk of early death).

Table 4

| Dependent: cancer-specific early death | 0 (N=323) | 1 (N=214) | OR (95%CI) (univariable) | OR (95%CI) (multivariable) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15-50 | 47 (14.6%) | 30 (14%) | ||

| 51-59 | 92 (28.5%) | 45 (21%) | 0.77 (0.43-1.37, p=.369) | ||

| >=60 | 184 (57%) | 139 (65%) | 1.18 (0.71-1.97, p=.516) | ||

| Race | White | 251 (77.7%) | 173 (80.8%) | ||

| Black | 30 (9.3%) | 16 (7.5%) | 0.77 (0.41-1.46, p=.430) | ||

| Other | 42 (13%) | 25 (11.7%) | 0.86 (0.51-1.47, p=.589) | ||

| Marital.status | Married | 162 (50.2%) | 104 (48.6%) | ||

| Unmarried | 152 (47.1%) | 100 (46.7%) | 1.02 (0.72-1.46, p=.892) | ||

| unknown | 9 (2.8%) | 10 (4.7%) | 1.73 (0.68-4.40, p=.249) | ||

| Grade | I | 8 (2.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | ||

| II | 30 (9.3%) | 8 (3.7%) | 0.71 (0.15-3.31, p=.664) | ||

| III | 100 (31%) | 46 (21.5%) | 1.23 (0.31-4.84, p=.770) | ||

| IV | 49 (15.2%) | 29 (13.6%) | 1.58 (0.39-6.43, p=.524) | ||

| unknown | 136 (42.1%) | 128 (59.8%) | 2.51 (0.65-9.67, p=.181) | ||

| T | T1 | 32 (9.9%) | 17 (7.9%) | ||

| T2 | 30 (9.3%) | 13 (6.1%) | 0.82 (0.34-1.96, p=.649) | 0.84 (0.29-2.42, p=.746) | |

| T3 | 132 (40.9%) | 54 (25.2%) | 0.77 (0.39-1.50, p=.443) | 0.64 (0.28-1.46, p=.283) | |

| T4 | 37 (11.5%) | 26 (12.1%) | 1.32 (0.61-2.87, p=.478) | 0.93 (0.35-2.45, p=.876) | |

| unknown | 92 (28.5%) | 104 (48.6%) | 2.13 (1.11-4.08, p=.023) | 1.00 (0.43-2.32, p=.997) | |

| N | N0 | 100 (31%) | 56 (26.2%) | ||

| N1 | 105 (32.5%) | 71 (33.2%) | 1.21 (0.77-1.88, p=.406) | 1.20 (0.68-2.13, p=.521) | |

| N3 | 60 (18.6%) | 33 (15.4%) | 0.98 (0.57-1.68, p=.948) | 1.04 (0.53-2.06, p=.900) | |

| unknown | 58 (18%) | 54 (25.2%) | 1.66 (1.01-2.73, p=.044) | 0.81 (0.42-1.58, p=.538) | |

| Surgery | No | 201 (62.2%) | 179 (83.6%) | ||

| Yes | 122 (37.8%) | 35 (16.4%) | 0.32 (0.21-0.49, p<.001) | 0.33 (0.18-0.61, p<.001) | |

| Radiation | No/Unknown | 168 (52%) | 144 (67.3%) | ||

| Yes | 155 (48%) | 70 (32.7%) | 0.53 (0.37-0.75, p<.001) | 0.55 (0.33-0.92, p=.022) | |

| Chemotherapy | No/Unknown | 83 (25.7%) | 161 (75.2%) | ||

| Yes | 240 (74.3%) | 53 (24.8%) | 0.11 (0.08-0.17, p<.001) | 0.14 (0.09-0.24, p<.001) | |

| Tumor.Size | 3-65 | 72 (22.3%) | 30 (14%) | ||

| 66-88 | 28 (8.7%) | 13 (6.1%) | 1.11 (0.51-2.44, p=.787) | 1.43 (0.53-3.90, p=.483) | |

| 90-150 | 41 (12.7%) | 25 (11.7%) | 1.46 (0.76-2.82, p=.254) | 1.35 (0.60-3.03, p=.473) | |

| unknown | 182 (56.3%) | 146 (68.2%) | 1.93 (1.19-3.11, p=.007) | 1.04 (0.57-1.91, p=.902) | |

| Brain.metastasis | No | 298 (92.3%) | 185 (86.4%) | ||

| Yes | 19 (5.9%) | 23 (10.7%) | 1.95 (1.03-3.68, p=.039) | 2.20 (1.01-4.79, p=.047) | |

| Unknown | 6 (1.9%) | 6 (2.8%) | 1.61 (0.51-5.07, p=.415) | 0.23 (0.02-3.26, p=.277) | |

| Liver.metastasis | No | 237 (73.4%) | 134 (62.6%) | ||

| Yes | 85 (26.3%) | 73 (34.1%) | 1.52 (1.04-2.22, p=.030) | 1.60 (0.98-2.62, p=.059) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3%) | 7 (3.3%) | 12.38 (1.51-101.71, p=.019) | 26.12 (0.78-879.02, p=.069) | |

| Lung.metastasis | No | 161 (49.8%) | 84 (39.3%) | ||

| Yes | 155 (48%) | 123 (57.5%) | 1.52 (1.07-2.17, p=.020) | 1.18 (0.76-1.84, p=.468) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.2%) | 7 (3.3%) | 1.92 (0.65-5.65, p=.238) | 0.60 (0.11-3.39, p=.562) | |

| Time.from.diagnosis.to.treatment | 0-9 | 64 (19.8%) | 52 (24.3%) | ||

| 10-27 | 84 (26%) | 37 (17.3%) | 0.54 (0.32-0.92, p=.024) | 0.63 (0.33-1.19, p=.153) | |

| 28-326 | 144 (44.6%) | 36 (16.8%) | 0.31 (0.18-0.52, p<.001) | 0.30 (0.16-0.56, p<.001) | |

| unknown | 31 (9.6%) | 89 (41.6%) | 3.53 (2.04-6.12, p<.001) | 0.83 (0.39-1.79, p=.637) | |

| Year.of.diagnosis | 2010-2015 | 151 (46.7%) | 86 (40.2%) | ||

| 2016-2021 | 172 (53.3%) | 128 (59.8%) | 1.31 (0.92-1.85, p=.134) | ||

| Histology | endometrioid subtype | 114 (35.3%) | 57 (26.6%) | ||

| non-endometrioid subtype | 169 (52.3%) | 124 (57.9%) | 1.47 (0.99-2.17, p=.056) | ||

| sarcoma subtype | 40 (12.4%) | 33 (15.4%) | 1.65 (0.94-2.89, p=.080) |

Univariate and multivariate Logistic regression analysis of CSED in the ECBM patients.

((0: CSED; 1: non-CSED); (OR, Odds Ratio; 95%CI, 95% Confidence Interval)).

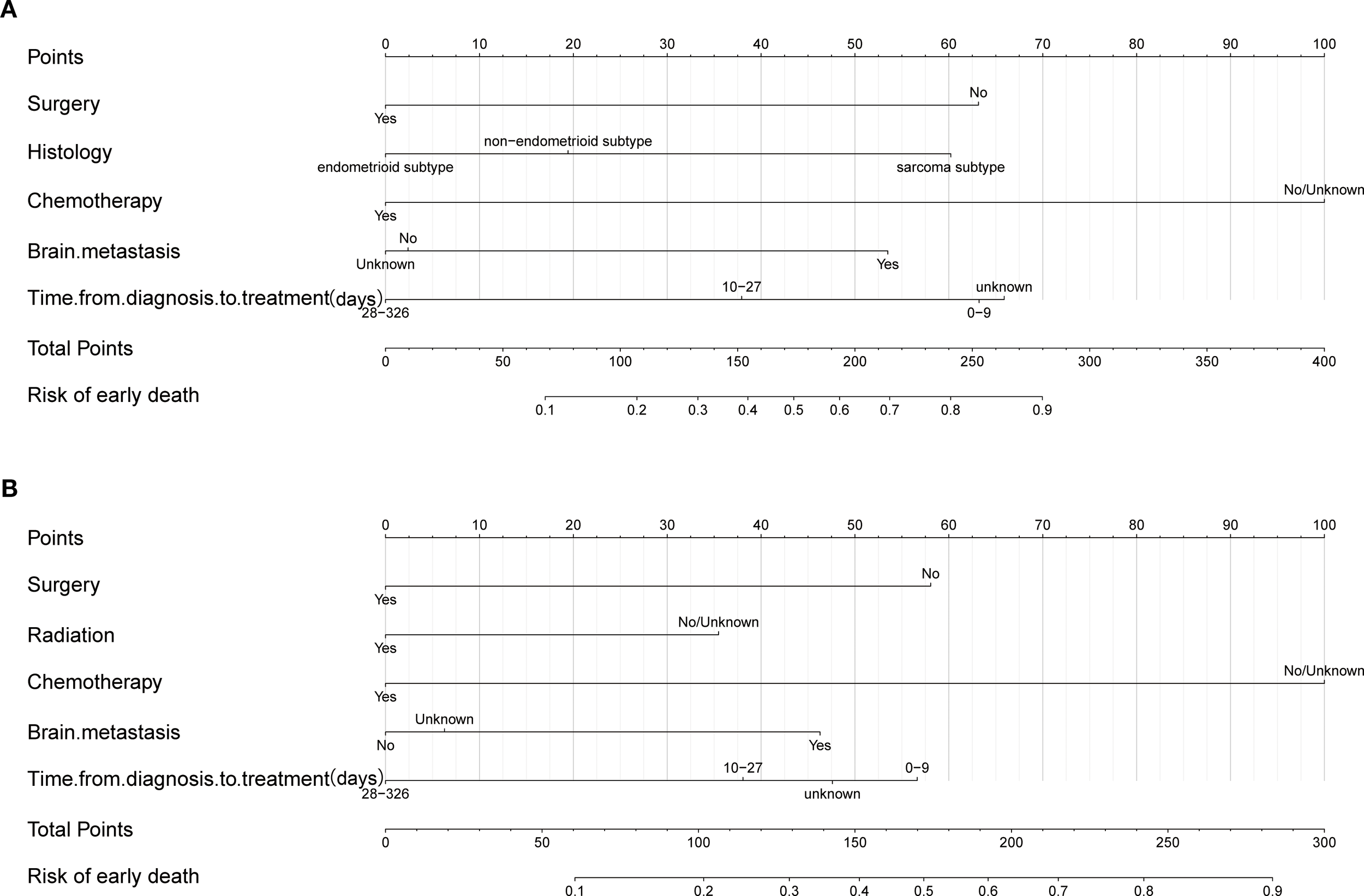

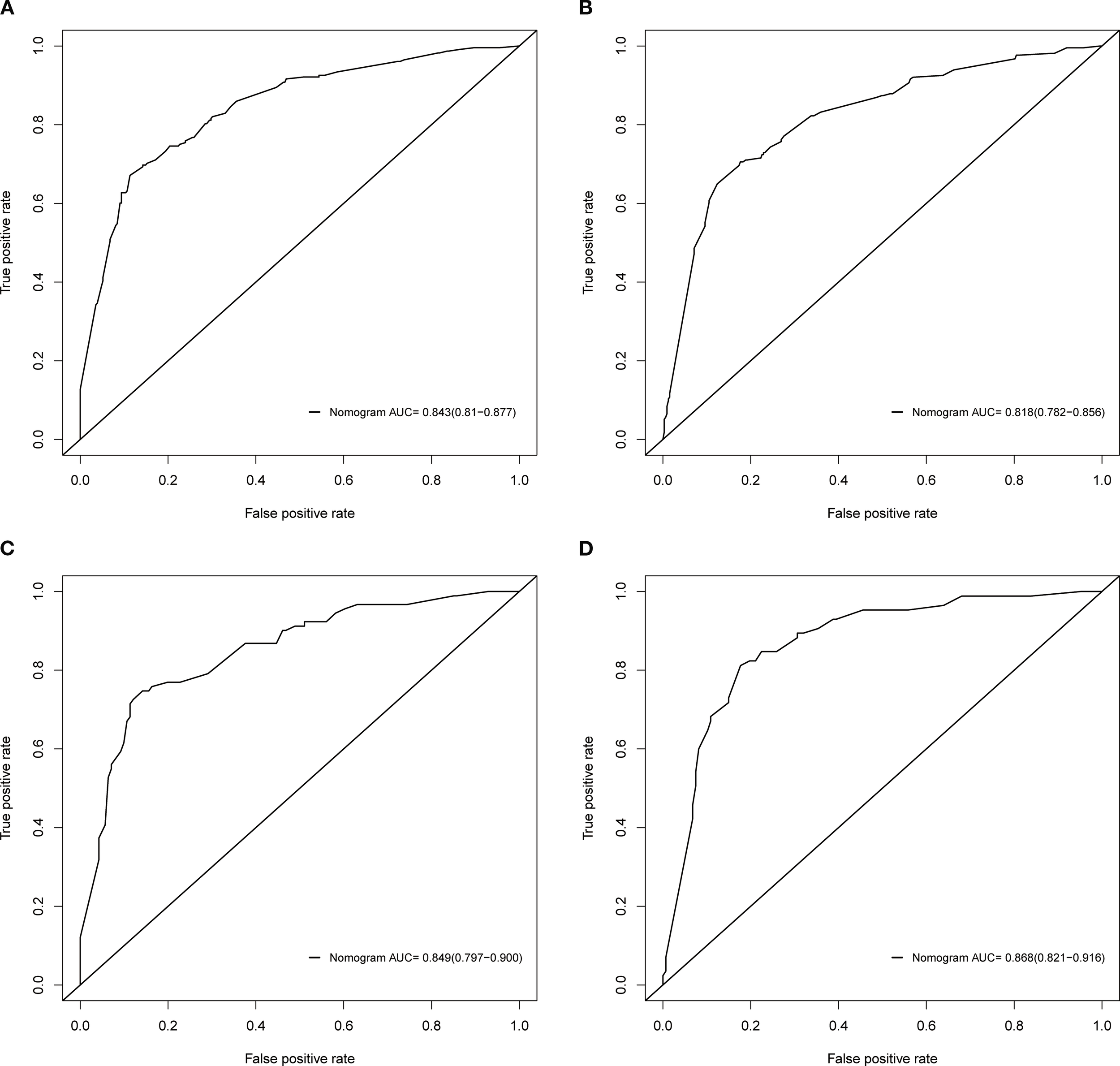

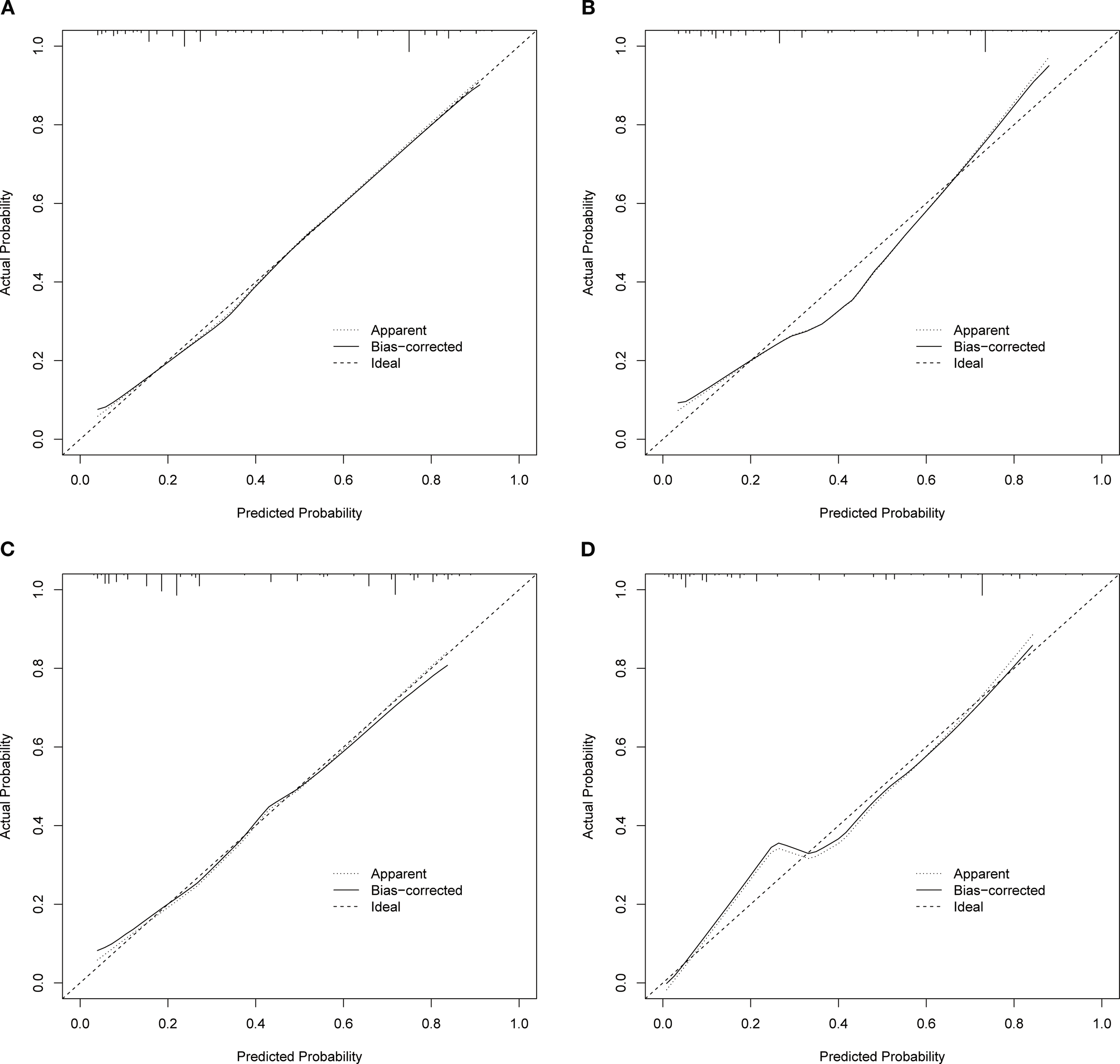

3.4 Establishment and verification of nomograms

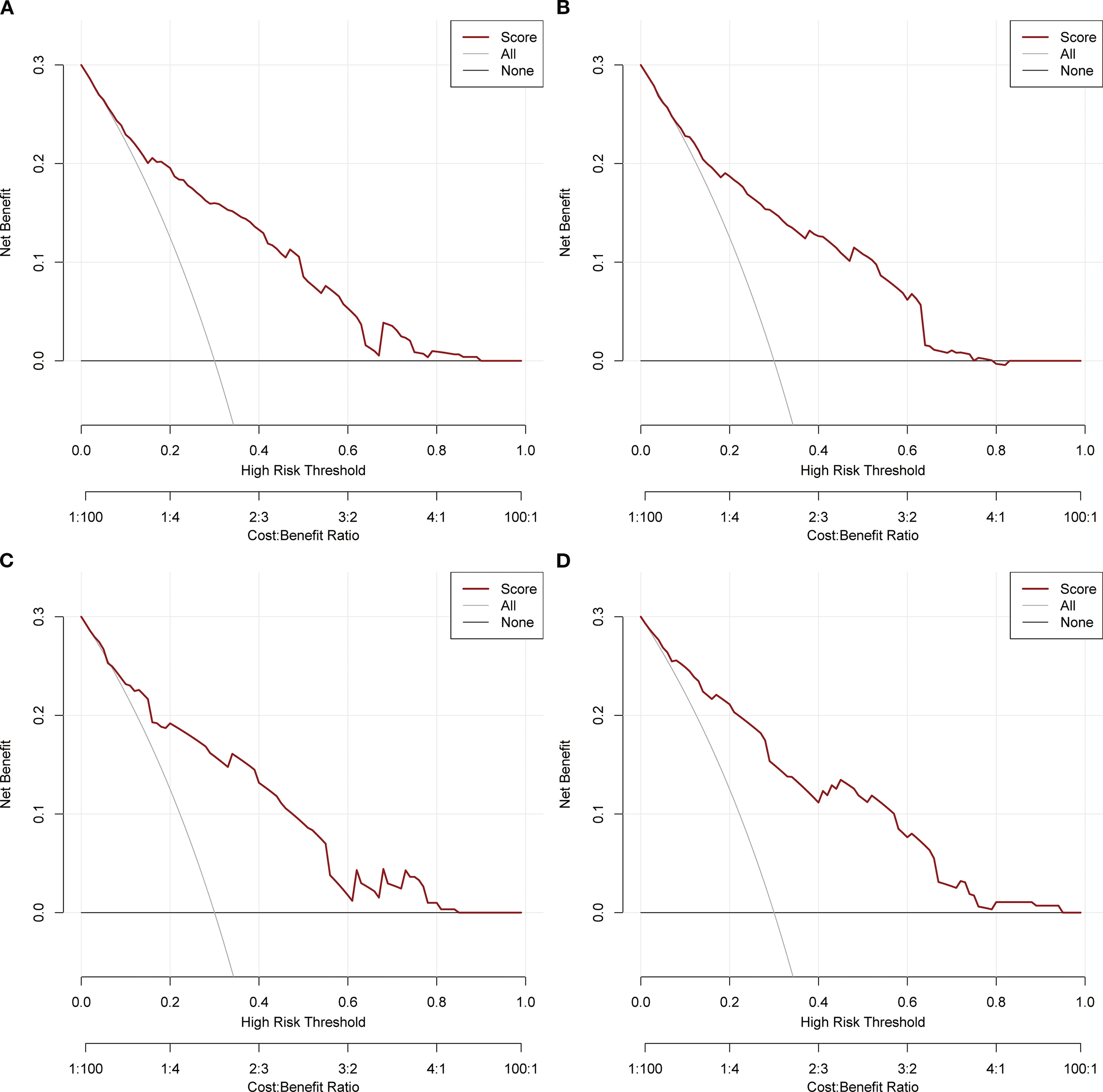

Based on the independent factors identified by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Nomograms were developed to evaluate the risks of OED and CSED in ECBM patients. (Figure 3). The ROC analysis for OED and CSED in the training and validation cohorts were shown in Figure 4. In the training cohort, the AUC values for OED and CSED were 0.843 and 0.818, respectively. In the validation cohort, the AUC values for OED and CSED were 0.849 and 0.868, respectively, indicating that the nomograms demonstrated strong predictive performance. The calibration curves demonstrate a strong concordance between predicted and observed probabilities (Figure 5). DCA analysis indicated that the model provides a positive net benefit, suggesting that the models developed in this study have substantial clinical applicability (Figure 6).

Figure 3

Nomogram for predicting early death in ECBM patients. (A) Overall early death, (B) cancer-specific early death.

Figure 4

ROC analysis of the nomograms. (A) OED in the training cohort, (B) CSED in the training cohort, (C) OED in the validation cohort, (D) CSED in the validation cohort.

Figure 5

Calibration curves. (A) OED in the training cohort, (B) CSED in the training cohort, (C) OED in the validation cohort, (D) CSED in the validation cohort.

Figure 6

DCA analysis. (A) OED in the training cohort, (B) CSED in the training cohort, (C) OED in the validation cohort, (D) CSED in the validation cohort.

4 Discussion

This study revealed that the early death rate in ECBM patients is alarmingly high, reaching 41.5%. This finding underscores the urgent need for a practical and reliable predictive tool to identify high-risk ECBM patients and provide personalized treatment strategies. In recent years, nomograms have emerged as intuitive and effective predictive tools, widely used for assessing the prognosis in malignancies. However, due to the rarity of ECBM, there are few related studies, and no comprehensive analyses have been published on the risk factors for early death in ECBM patients. Furthermore, there has been no research to establish predictive models for early mortality in ECBM. The nomogram based on SEER database has a larger total sample, which significantly improves the accuracy and stability of the nomogram. In this study, we explored the independent risk factors for early death in ECBM patients using the SEER database and developed easy-to-use nomogram models to predict the risk of early death. These models aimed at assisting clinicians in the early identification of high-risk patients and optimizing clinical decision-making.

The univariate and multivariate analyses identified five independent risk factors for OED in ECBM patients, including surgery, histological type, chemotherapy, brain metastasis, and time from diagnosis to treatment. Additionally, five independent risk factors were determined for CSED in ECBM patients, which include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, brain metastasis, and time from diagnosis to treatment. Among the independent risk factors for OED, chemotherapy had the most significant impact on patient prognosis, followed by time from diagnosis to treatment, surgery, histological type, and brain metastasis. Similarly, in the context of CSED, chemotherapy emerged as the most critical factor, followed by time from diagnosis to treatment, surgery, brain metastasis, and radiotherapy. Surgery is the standard treatment for localized EC. However, there remains controversy regarding the use of surgery for metastatic or advanced EC. Most ECBM patients experience varying degrees of pain and structural bone damage (10). The primary goals of surgery were alleviating symptoms (such as pain, fractures, and nerve compression), reducing tumor burden, improving function and quality of life, facilitating other treatments, and prolonging survival.

This study revealed that surgery was significantly associated with improved survival outcomes in ECBM patients, suggesting a potential protective effect, which is consistent with previous research (11). However, we acknowledge that in this retrospective analysis, the selection of surgical candidates may have been influenced by factors such as better baseline clinical condition, disease extent, and overall performance status. Currently, cytoreductive surgery has been demonstrated to enhance survival outcomes and prolong overall survival (OS) in appropriately selected ECBM patients (12, 13). In clinical practice, whether to perform surgery for ECBM patients should comprehensively consider the site of metastasis, degree of diffusion, respectability, and patient status. Similarly, this study found that chemotherapy was associated with survival benefits for ECBM patients, though we recognize that treatment selection may have been influenced by patient fitness and disease characteristics suitable for systemic therapy. The combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel has been established as a first-line treatment for advanced and metastatic EC patients (13). With ongoing research into TCGA molecular subtyping, the therapeutic landscape for metastatic and recurrent EC is changing. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel in combination with pembrolizumab or dostarlimab as first-line therapy for recurrent or metastatic EC patients (14). Two phase III clinical trials have shown that compared to chemotherapy alone, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (i.e., pembrolizumab or dostarlimab) in conjunction with conventional chemotherapy leads to improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival in patients with metastatic or recurrent EC patients (15), without a significant increase in the incidence of common adverse effects. This study indicates that radiotherapy is a weak influencing factor for CSED, which aligns with previous findings (11, 12). For patients with early moderate to high risk EC, vaginal brachytherapy (VBT) or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) can effectively reduce tumor recurrence and mortality rates (16). However, some researchers argue that due to distant metastases in advanced EC patients, radiotherapy as a local treatment is difficult to effectively control distant metastases and improve the survival rate of advanced patients (17, 18). Therefore, for ECBM patients, palliative EBRT is commonly used for pain relief (19). To improve the survival of distant metastases patients, several recent studies have explored the performance of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABRT) in patients with oligometastases, as shown in a Phase II randomized SABR-COMET trial (NCT01446744). SABRT significantly reduced the progression-free survival (PFS) in oligometastasis patients but prolonged OS (20). In order to improve the survival and prognosis of patients, the treatment of distant metastatic EC patients usually needs to be personalized and customized by evaluating the patient’s status, pathological classification, comprehensive surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy, etc.

Furthermore, this study found that histological type is also an important factor for ECBM patients, with sarcomatous subtypes being significantly associated with a higher risk of early death. According to the research, patients with sarcomatous subtypes often have poorer prognoses, particularly those with high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma (9). Studies have shown that these subtypes are generally more aggressive and are often associated with high recurrence rates and low survival rates and that traditional treatments (including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) offer limited survival benefits for these subtypes (21, 22). The relationship between multiple distant metastases and poor prognosis in EC patients has been confirmed (23). In this study, ECBM patients with concomitant brain metastases presented a higher risk of early death rate, which is consistent with previous studies (6, 23). Mao et al. revealed that the shortest median survival of two-organ metastasis with brain metastases was only 1 month, which may be related to the easy formation of multiple metastases in the brain and the difficulty of treatment due to the limitation of the blood-brain barrier the early mortality risk in ECBM patients (6, 24). Additionally, an extended time from diagnosis to treatment initiation could lead to disease progression and further worsen prognosis. This finding underscores the importance of early intervention, which is crucial for reducing the early death risk in ECBM patients.

This research revealed that age is not an independent predictor of early death for ECBM patients, which is consistent with previous studies (11, 17, 25). In this study, patients with bone metastases had an older median age, and shorter survival, which may be one of the important reasons why age was not included as an independent prognostic factor. Many previous studies have shown that tumor grade is an important factor influencing patient prognosis including metastatic EC (11, 17, 26), but it is not significant in this study, which may be due to the high proportion of missing data on pathological grade in this study, and future studies with higher data integrity are needed. In terms of pathological grade, young EC patients are often highly differentiated and staged early, which indicates a higher survival rate and better quality of life. Older women are usually diagnosed at an advanced stage with poorer histological types and tend to have a poor prognosis. Elderly patients are usually complicated with underlying diseases, are more likely to have risk factors such as invasion of tumor, advanced stage, and more aggressive histological type, and have poor tolerance to treatment. Therefore, age factors should be fully considered in clinical practice to optimize disease management strategies. Previous studies have found that tumor size is an important independent predictor of early EC patients (27). However, tumor size may not have a significant effect on the prognosis of metastasis patients, which was consistent with the findings of Yan et al. (28). Race was also not a significant independent predictor in this study, which is different from what previous studies found (29). This may be because many previous studies focused on all EC patients, but this study only focused on ECBM patients. Currently, few studies have found a link between survival and marital status.

Despite the inherent challenges associated with studying rare malignancies through retrospective database analysis, this research addresses a significant clinical need. The development of predictive nomograms for ECBM patients fills an important gap in gynecologic oncology, providing clinicians with evidence-based tools for risk stratification and treatment planning in a patient population that has been inadequately studied due to its low incidence. While the clinical scenario may represent a small proportion of gynecologic oncology practice, the high early mortality rate (41.5%) observed in ECBM patients emphasizes the critical importance of accurate prognostic assessment for optimal patient management. The rigorous statistical approach employed in this study, combined with the comprehensive nature of the SEER database, provides the most robust analysis possible within the constraints of studying this rare condition.

ROC curve, calibration curve, and DCA analysis of this research revealed that the nomograms have high prediction accuracy, high consistency, and clinical application value. However, this study has some limitations: (1) This study was established based on a public database and employed a retrospective design. Due to the low incidence of ECBM, external validation was not included in this study. Therefore, the models need to be further evaluated by external data from multiple institutions; (2) The SEER database does not provide the detailed records of chemotherapy, radiotherapy and targeted therapy, which limits the further exploration of treatment plans in this study; (3) The SEER database does not contain TCGA molecular typing (such as POLE mutation, MSI-H, etc.), tumor biomarkers (such as CA125, etc.), lymphatic vascular space infiltration (LVSI), immunohistochemistry, lymph node metastasis and other important information, which limits the comprehensiveness of the models. (4) The SEER database contains a large amount of unknown information, which may interfere with the results of the models. This study is a retrospective study, and the prediction accuracy of the model needs to be further verified by future multi-center prospective studies. (5) It is important to acknowledge that the clinical scenario evaluated in this study, ECBM, represents a relatively small proportion of gynecologic oncology practice. This relatively low prevalence may limit the broad applicability of our findings across the full spectrum of gynecologic oncology. Nevertheless, for this specific patient population, our nomograms provide valuable prognostic tools that can assist in clinical decision-making despite the limited overall incidence of the condition. While we acknowledge that this retrospective analysis based on the SEER database has inherent limitations, the rarity of this condition makes large-scale prospective studies challenging. Within the scope of available data, we employed rigorous statistical methodology to address clinically relevant questions and provide evidence-based prognostic tools where none previously existed.

5 Conclusion

The predictive models constructed in this study can effectively predict the risk of early death in ECBM patients, providing an important reference for clinical decision-making. Despite limitations, this study lays a foundation for improving the prognostic management of high-risk ECBM patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Huaian No. 1 People's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

QT: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation. YS: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. YG: Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1613843/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

OR, odds ratio; ECBM, endometrial cancer bone metastases; ROC, Receiver Operating Characteristic l; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; DCA, decision curve analysis; OED, overall early death; CSED, cancer-specific early death; TNM, Tumor-Node-Metastasis; AJCC, the American Joint Committee on Cancer; ICD-O-3, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition; AUC, Area Under Curve; OS, overall survival; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PFS, progression-free survival; VBT, vaginal brachytherapy; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; SABRT, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy; SABR-COMET, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic disease; POLE, polymerase epsilon; MSI-H, Microsatellite Instability-High; LVSI, lymphatic vascular space infiltration.

References

1

Di Donato V Giannini A Bogani G . Recent advances in endometrial cancer management. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:2241. doi: 10.3390/jcm12062241

2

Siegel RL Miller KD Fuchs HE Jemal A . Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. (2022) 72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708

3

Gordhandas S Zammarrelli WA Rios-Doria EV Green AK Makker V . Current evidence-based systemic therapy for advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2023) 21:217–26. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.7254

4

Liu Y Chi S Zhou X Zhao R Xiao C Wang H . Prognostic value of distant metastatic sites in stage iv endometrial cancer: A seer database study of 2948 women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2020) 149:16–23. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13084

5

Vujić G Potkonjak AM Periša MM . 12-Year Follow up after Successful Treatment of Stage Ivc Endometrial Cancer with Bone Metastasis: A Case Report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2024) 292:267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.11.014

6

Mao W Wei S Yang H Yu Q Xu M Guo J et al . Clinicopathological study of organ metastasis in endometrial cancer. Future Oncol. (2020) 16:525–40. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0017

7

Pan WK Ren SY Zhu LX Lin BC . A web-based prediction model for early death in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. (2024) 47:71–80. doi: 10.1097/coc.0000000000001058

8

Che WQ Li YJ Tsang CK Wang YJ Chen Z Wang XY et al . How to use the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (Seer) data: research design and methodology. Mil Med Res. (2023) 10:50. doi: 10.1186/s40779-023-00488-2

9

Song Z Wang Y Zhang D Zhou Y . A novel tool to predict early death in uterine sarcoma patients: A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-based study. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:608548. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.608548

10

Wang J Dai Y Ji T Guo W Wang Z Wang J . Bone metastases of endometrial carcinoma treated by surgery: A report on 13 patients and a review of the medical literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:6823. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116823

11

Hu H Wang Z Zhang M Niu F Yu Q Ren Y et al . Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis in endometrial cancer with bone metastasis: A seer-based study of 584 women. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:694718. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.694718

12

Zhang Y Hao Z Yang S . Survival benefit of surgical treatment for patients with stage ivb endometrial cancer: A propensity score-matched seer database analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. (2023) 43:2204937. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2023.2204937

13

Heidinger M Simonnet E Koh LM Frey Tirri B Vetter M . Therapeutic approaches in patients with bone metastasis due to endometrial carcinoma -a systematic review. J Bone Oncol. (2023) 41:100485. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2023.100485

14

Abu-Rustum NR Campos SM Amarnath S Arend R Barber E Bradley K et al . NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Uterine Neoplasms, Version 3.2025. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2024) 23:284–91. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2025.0038

15

Bogani G Monk BJ Powell MA Westin SN Slomovitz B Moore KN et al . Adding immunotherapy to first-line treatment of advanced and metastatic endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. (2024) 35:414–28. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.02.006

16

Harkenrider MM Abu-Rustum N Albuquerque K Bradfield L Bradley K Dolinar E et al . Radiation therapy for endometrial cancer: an american society for radiation oncology clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol. (2023) 13:41–65. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2022.09.002

17

Zheng Y Jiang P Tu Y Huang Y Wang J Gou S et al . Incidence, risk factors, and a prognostic nomogram for distant metastasis in endometrial cancer: A seer-based study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2024) 165:655–65. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.15264

18

Yang F Zhao R Huang X Wang Y . Diagnostic and prognostic factors, and two nomograms for endometrial cancer patients with bone metastasis: A large cohort retrospective study. Med (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e27185. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000027185

19

Coleman R Hadji P Body JJ Santini D Chow E Terpos E et al . Bone health in cancer: esmo clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. (2020) 31:1650–63. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.019

20

Palma DA Olson R Harrow S Gaede S Louie AV Haasbeek C et al . Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic cancers: long-term results of the sabr-comet phase ii randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:2830–8. doi: 10.1200/jco.20.00818

21

Lewis D Liang A Mason T Ferriss JS . Current treatment options: uterine sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. (2024) 25:829–53. doi: 10.1007/s11864-024-01214-3

22

Rizzo A Pantaleo MA Saponara M Nannini M . Current status of the adjuvant therapy in uterine sarcoma: A literature review. World J Clin cases. (2019) 7:1753–63. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1753

23

Zhang M Li R Zhang S Xu X Liao L Yang Y et al . Analysis of prognostic factors of metastatic endometrial cancer based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Front Surg. (2022) 9:1001791. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.1001791

24

Bhambhvani HP Zhou O Cattle C Taiwo R Diver E Hayden Gephart M . Brain metastases from endometrial cancer: clinical characteristics, outcomes, and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. (2021) 147:e32–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.087

25

Forte M Cecere SC Di Napoli M Ventriglia J Tambaro R Rossetti S et al . Endometrial cancer in the elderly: characteristics, prognostic and risk factors, and treatment options. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2024) 204:104533. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104533

26

Yang J Tian Q Li G Liu Q Tang Y Jiang D et al . Identifying risk factors for cancer-specific early death in patients with advanced endometrial cancer: A preliminary predictive model based on seer data. PloS One. (2025) 20:e0318632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0318632

27

Jiao S Wei L Zou L Wang T Hu K Zhang F et al . Prognostic values of tumor size and location in early stage endometrial cancer patients who received radiotherapy. J Gynecol Oncol. (2024) 35:e84. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2024.35.e84

28

Yan G Li Y Du Y Ma X Xie Y Zeng X . Survival nomogram for endometrial cancer with lung metastasis: A seer database analysis. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:978140. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.978140

29

Lee MW Vallejo A Furey KB Woll SM Klar M Roman LD et al . Racial and ethnic differences in early death among gynecologic Malignancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2024) 231:231.e1–.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2024.03.003

Summary

Keywords

endometrial carcinoma, bone metastases, early death, SEER database, nomogram

Citation

Tang Q, Sun Y and Gao Y (2025) Establishment and validation of a nomogram model for predicting early death in patients with endometrial cancer bone metastases. Front. Oncol. 15:1613843. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1613843

Received

17 April 2025

Accepted

17 September 2025

Published

01 October 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Stefano Restaino, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia di Udine, Italy

Reviewed by

John E Mignano, Tufts University, United States

Tomoyuki Otani, Kindai University, Japan

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Tang, Sun and Gao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yingchun Gao, gych691222@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.