- 1Department of Clinical Medicine, Qinghai University, Xining, Qinghai, China

- 2Department of Urology, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining, Qinghai, China

- 3Department of Pathology, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining, Qinghai, China

- 4Department of Nephrology, Meishan People’s Hospital, Meishan, Sichuan, China

Background: Angiomyolipoma with Epithelial Cysts (AMLEC) is a rare renal tumor that has been established as a separate pathological entity in recent years. Existing literature has focused on its histological origin, molecular features, and imaging characteristics. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of AMLEC coexisting with clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC).

Case presentation: A 37-year-old male presented with lumbar pain and persistent gross hematuria. Imaging revealed tumor rupture with hemorrhage, initially suggestive of cystic renal cell carcinoma. However, postoperative pathology and immunohistochemistry confirmed a diagnosis of AMLEC combined with ccRCC.

Conclusion: AMLEC is a rare subtype of angiomyolipoma (AML) that typically lacks adipose tissue, with an epithelial component likely derived from dilated renal tubules. Its unique histological features and immunohistochemical staining are key to pathological diagnosis. This report also reviews prior cases of AMLEC and synchronous renal tumors, offering a valuable reference for clinical diagnosis and management.

1 Introduction

Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts (AMLEC) is a rare renal tumor recognized as a distinct subtype of angiomyolipoma (AML). Some researchers consider it a cystic variant of AML (1) or a fat-poor type of AML (2, 3). AMLEC was first described by Fine et al. (4) and Davis et al. (5), who referred to it as “angiomyolipoma with epithelioid cyst” and “renal cystic angiomyolipoma,” respectively, with the former term gaining broader recognition.

Due to its distinct histologic morphology and immunophenotype, the Vancouver Classification of Renal Tumors and the International Society of Urological Pathology recognized AMLEC in 2012 as an epithelial cystic variant of AML, though it was not formally categorized as a subtype (6). It was not until 2022 that the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Urological and Male Genital System formally classified AMLEC as a subtype of AML (7).

AML consists of mature adipose tissue, smooth muscle, and thick-walled blood vessels (1, 8). In contrast to typical AML, AMLEC is characterized by epithelium-lined cysts, Müllerian tube-like subepithelial stroma, and thick-walled blood vessels, typically lacking adipose tissue (9). Regarding the origin of AMLEC epithelial cells, most researchers (9, 10) support the viewpoint of Fine et al. (4) that the epithelial component of AMLEC is composed of non-tumorous, entrapped, and dilated renal tubules, but this view remains controversial. The most recent study further adds to the findings of Fine et al. that the epithelial and stromal components of AMLEC may represent a hormone-driven proliferation of non-tumorigenic renal components in the context of a dysregulated tumor microenvironment (11).

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the main subtype of renal cell carcinoma, accounting for approximately 70% of all renal cell carcinomas (12). Renal cell carcinoma typically presents as a unilateral lesion; however, the presence of multiple tumors, both synchronous and asynchronous, has been observed in 2–4% of sporadic cases (13). Here, we present a case of a rare synchronous tumor along with its immunohistochemical findings.

2 Case report

In September 2023, a 34-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with right-sided lumbar pain, followed by gross hematuria. Physical examination revealed tenderness and percussion pain in the right renal region. There was no bilateral lower extremity edema, and no palpable abdominal mass or evidence of lower back trauma. The patient had no history of chronic diseases, such as hypertension, and no family history of renal cysts, renal tumors, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), or related conditions. Before admission, he had consulted multiple medical institutions and was diagnosed with a right renal cyst with hemorrhage.

The patient had not undergone any prior interventions. Following admission, laboratory tests revealed a mildly elevated serum creatinine level of 98 μmol/L (reference range: 57–97 μmol/L), while the complete blood count and other key biochemical markers remained within normal limits.

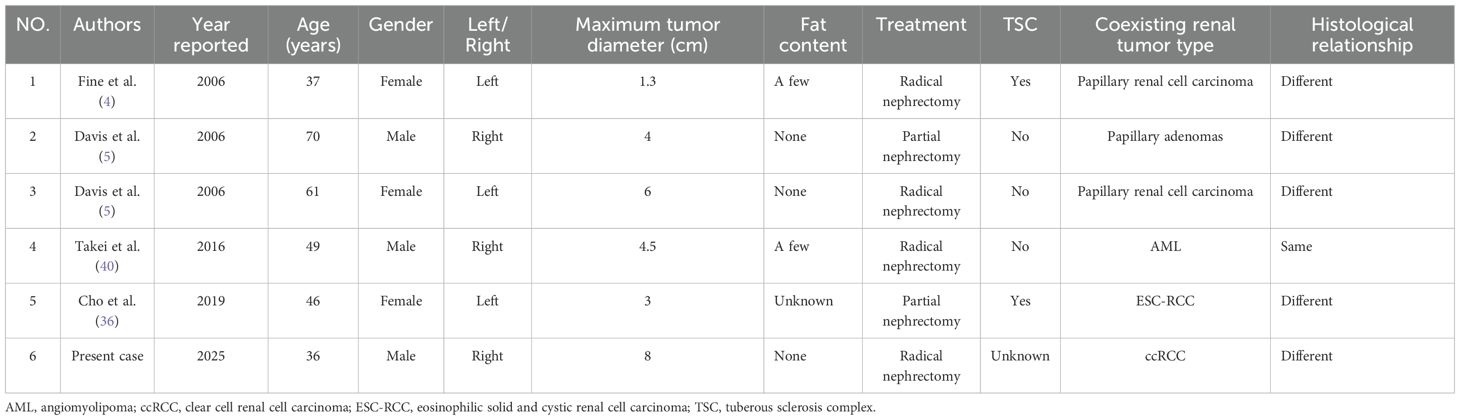

An enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of both kidneys identified a space-occupying lesion at the lower pole of the right kidney, measuring 80 mm × 61 mm, raising suspicion of malignancy and associated hemorrhage (Figure 1A). Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lower abdomen detected a lesion in the same region, with internal hemorrhage, measuring 75 mm × 73 mm × 63 mm, and suggested possible encroachment of the renal pelvis (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. (A) Shows the lower pole of the right kidney with an occupying mixed density lesion protruding from the renal silhouette. This lesion had clear borders and a large cross-sectional area of approximately 80×61mm, with uneven density, localized lamellar hyperdense shadows, mild enhancement of the solid portion, and localized lamellar hyperdense shadows with no significant enhancement (red arrows). (B) Shows the lower pole of the right kidney and a rounded mass-like mixed lesion with predominantly long T2 and short T1 signals. This lesion protruded outside of the renal silhouette, with a maximum diameter of approximately 75×70×63mm. Multi-cystic changes with segregation were evident inside the lesion, with septal and partial nodular enhancement after enhancement and unclear demarcation between the lesion and the renal pelvis (red arrowheads).

Urine exfoliative cytology indicated atypical urinary epithelial cells, while urinalysis revealed occult blood at a level of 3 +. Erythrocyte phase contrast microscopy showed homogeneous erythrocyte morphology, thereby excluding a glomerular source of hematuria.

Based on a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s clinical presentation, imaging findings, and urine exfoliative cytology results, the preliminary diagnosis was a cystic renal cell carcinoma with rupture and hemorrhage. Given the tumor rupture, prominent symptoms, potential for worsening renal function under conservative management, and imaging findings highly suggestive of malignant transformation, surgical intervention was deemed necessary. To preserve renal function, a right ureteral stent was placed preoperatively. On September 19, 2023, under general anesthesia, the patient underwent laparoscopic radical resection of the right kidney and tumor.

Postoperatively, the patient underwent genetic counseling to assess the necessity of TSC gene testing. TSC is an autosomal dominant disorder, with a 50% inheritance risk for offspring of an affected individual (14). Since the patients and their first-degree relatives exhibited neither TSC-related clinical features nor a family history suggestive of TSC, the necessity for TSC1/TSC2 genetic testing was deemed low.

The patient underwent abdominal and chest CT at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year postoperatively. The patient was in good general condition. Radiological evaluation was consistent with surgical resection and no signs of metastasis were found. Laboratory findings were normal.

3 Pathological results

Gross examination revealed a cystic cavity located at the lower pole of the kidney, adjacent to the renal capsule, measuring approximately 70 mm × 60 mm × 20 mm. On sectioning, the lesion showed multiloculated cystic and solid areas and contained bloody fluid.

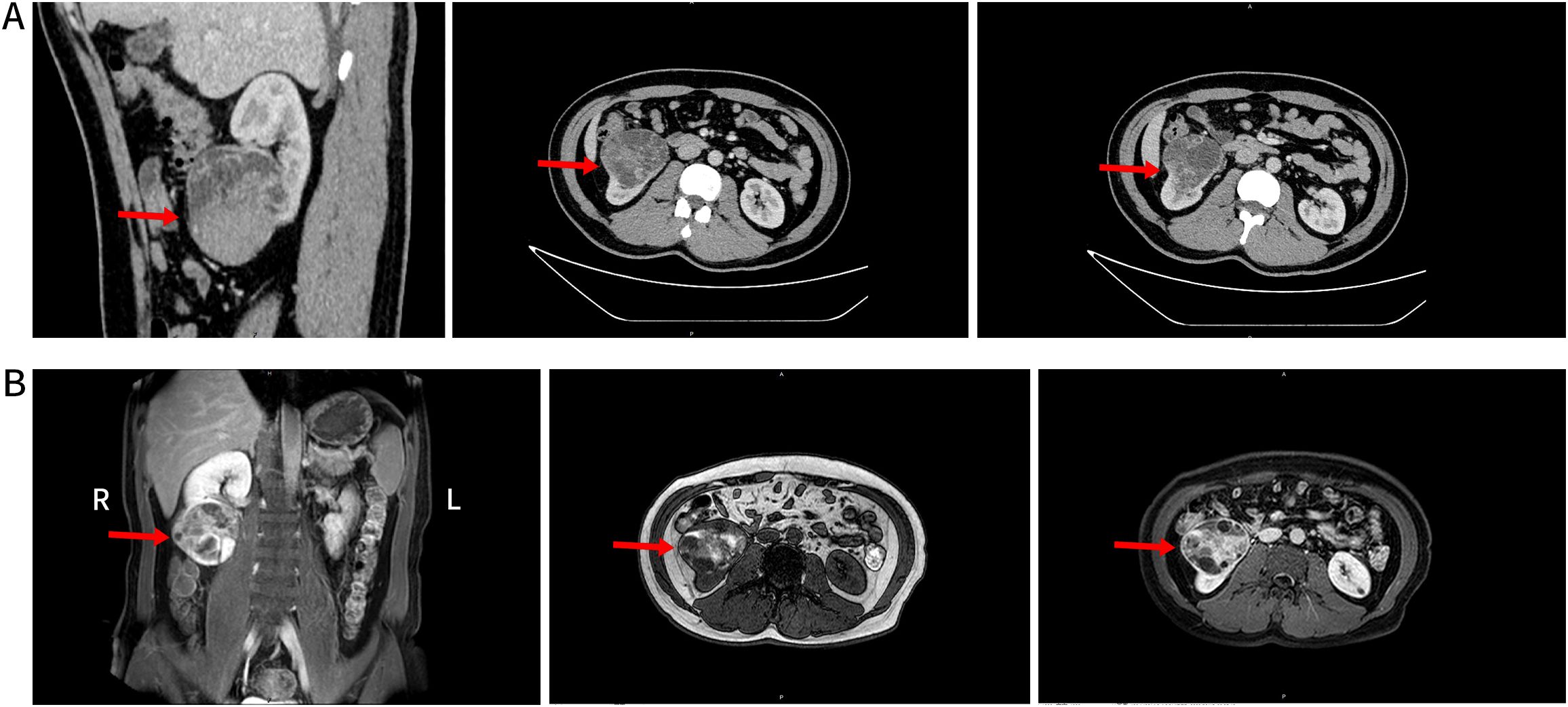

At low magnification, cystic structures are evident, with cyst walls of variable thickness, displaying irregular oval and slit-like configurations in some areas. The cysts are lined by a single or multilayered epithelium, beneath which compact stromal cells are observed. At intermediate magnification, the epithelium is composed of a single layer of cuboidal cells or multilayered columnar cells, with focal areas displaying boot-shaped or peg-like projections and focal epithelial denudation. Beneath the epithelium, spindle-shaped, oval, and epithelioid stromal cells are observed, and parts of the stromal component show smooth muscle–like differentiation, with scattered lymphocytes distributed among them. In addition, variably sized, dilated, and congested thick-walled dysmorphic blood vessels are identified (Figures 2A–D).

Figure 2. Microscopic and immunohistochemical findings of AMLEC. (A) Both epithelial and stromal components are observed, with numerous thick-walled, variably sized dysplastic blood vessels in the surrounding area (H&E, ×20). (B) Stromal cells are distributed around blood vessels, with scattered lymphocytes (H&E, ×40). (C) Compact stromal cells exhibiting epithelioid or short spindle-shaped morphology (H&E, ×40). (D) Stromal cells showing epithelioid features with coarse nuclear chromatin and relatively intact nuclear membranes (H&E, ×40). (E) Subepithelial stromal cells show diffuse positivity for ER (×20). (F) Subepithelial stromal cells show patchy positivity for desmin (×20). (G) Subepithelial stromal cells show diffuse positivity for HMB45 (×20). (H) Epithelial cells show diffuse positivity for PAX8 (×10).H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemistry (Figure 2E–H) showed that the epithelial component was positive for pancytokeratin (CK) and PAX8, while the stromal component showed positive staining for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), CD10, desmin, HMB45, and Melan-A. Smooth muscle actin (SMA) demonstrated focal positivity, and some stromal cells expressed WT-1. Inhibin was negative, and the Ki-67 labeling index was approximately 10%. Based on the immunohistochemical profile, a diagnosis of AMLEC was rendered.

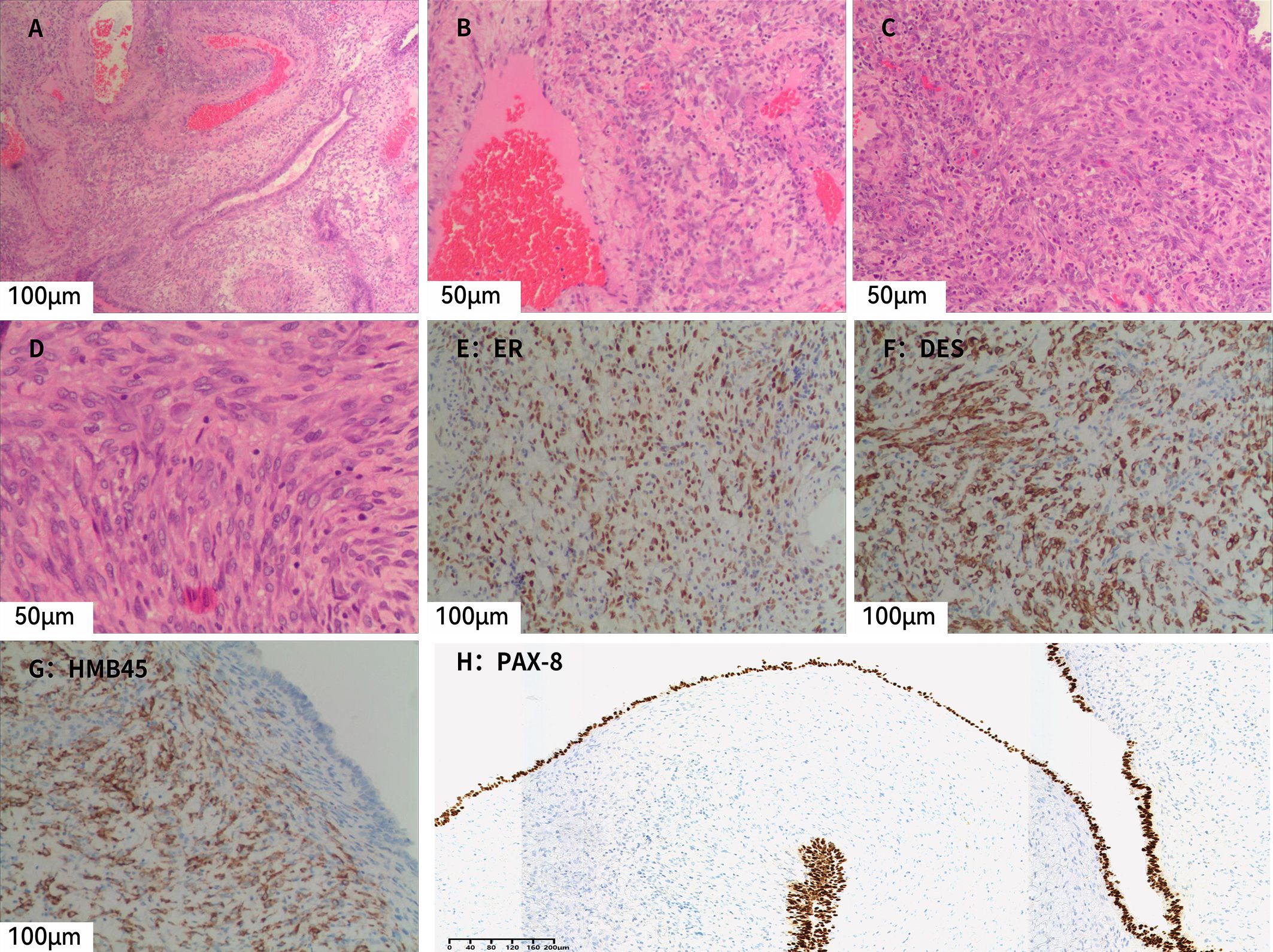

Unexpectedly, a grayish-yellow nodule measuring approximately 3 mm × 2 mm × 0.8 mm, with a golden-yellow cut surface, was identified in the upper pole of the kidney. This nodule had not been detected on preoperative imaging. Microscopically (Figures 3A–C), the tumor is well-circumscribed and composed of nests and alveolar structures separated by a delicate vascular network. The tumor cells have abundant clear cytoplasm and centrally located round nuclei. Immunohistochemical analysis (Figures 3D, E) showed that the tumor cells were positive for PAX8, CA-9, CD10, and CK7, but negative for CD117 and TFE3. SDHB expression was retained, and the Ki-67 labeling index was approximately 5%. The nodule was diagnosed as ccRCC, staged as pT1aN0M0 and classified as WHO/ISUP grade 1.

Figure 3. (A–C) Microscopic examination reveals tumor cells with distinct cell borders and abundant clear cytoplasm. Small, dilated, and congested capillaries are present within the tumor, and no fibroblastic proliferation is observed (Hematoxylin–eosin staining; A, ×20; B, ×40; C, ×40). (D) Tumor cells show diffuse membranous positivity for CA-9 (×40). (E) Tumor cell nuclei show diffuse positivity for PAX8, supporting renal epithelial differentiation (×20).

Combining all these findings, we finally diagnosed the patient with AMLEC combined with ccRCC. The patient’s treatment timeline is delineated in Supplementary Figure 1.

4 Discussion

A study of 1,064 cases of postoperative renal angiomyolipoma revealed that only 11 were diagnosed as AMLEC, accounting for approximately 1% of cases (5). Research indicates that AMLEC is more prevalent in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:3 (15). The vast majority of patients are clinically asymptomatic, with the condition typically detected incidentally during routine physical examinations or imaging. However, some patients may present with symptoms such as hematuria, proteinuria, an abdominal mass, retroperitoneal bleeding, abdominal pain, groin pain, or renal insufficiency (16, 17). When patients present with gross hematuria and lumbar pain, this may suggest an emergent clinical condition, such as bleeding from a ruptured tumor.

Classic AML is readily identifiable on CT and MRI due to its abundant mature adipose tissue. In contrast, AMLEC typically lacks adipose content and exhibits cystic features, which Acar et al. described as a rare variant of fat-poor angiomyolipoma (2). Since most previously reported cases of AMLEC fall under Bosniak type III or IV and exhibit imaging characteristics similar to malignant cystic renal tumors, such as cystic renal cell carcinoma (cRCC) and cystic nephroma (CN), they are frequently misdiagnosed preoperatively as other renal neoplasms (2, 18–20). Some studies suggest that contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) may be a promising additional diagnostic tool that not only demonstrates good performance in differentiating benign and malignant renal lesions, but also improves the diagnostic sensitivity of malignant cystic masses (21–24).

AMLEC displays distinct immunohistochemical features that assist in its diagnosis. The cyst-lining epithelium expresses PAX8, PAX2, and CK7, while the subepithelial stromal region shows strong positive staining for ER, PR, CD10, Melan-A, and HMB45. Additionally, the muscular component stains most intensely for smooth muscle actin and desmin (25).

The role of renal puncture biopsy in the early diagnosis and risk stratification of renal cystic tumors remains a topic of ongoing debate (26). Some researchers argue that biopsy may cause complications, such as hemorrhage or tumor dissemination, and therefore should not be employed routinely (27). Conversely, given the challenges of definitively identifying fat-poor angiomyolipomas using CT or MRI alone, some advocate for percutaneous biopsy in such cases (28–30). Moreover, in TSC-associated renal cystic tumors, biopsy may induce hemorrhage in highly vascularized angiomyolipomas or even facilitate malignant cell dissemination, making it generally inadvisable (31). Overall, the clinical indications for renal puncture biopsy require further investigation.

Recent reports have explored the molecular basis of AMLEC. Xu et al. (32) identified a TSC1 splicing mutation in a fat-poor AMLEC, while Song et al. (33) reported a TSC2 nonsense mutation associated with activation of the PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway. These findings highlight the potential for molecular diagnosis of AMLEC in clinical practice. However, given the sporadic reports, further studies are needed to validate these mutations and assess their role in guiding potential targeted therapies.

An intriguing aspect of AMLEC is its relationship with TSC. AML occurs in approximately 80% of adult patients with TSC and typically manifests as unilateral or bilateral multifocal lesions (34, 35). However, the relationship between AMLEC and TSC remains unclear, with only three reported cases of TSC co-occurring with AMLEC in the literature (4, 10, 36). Thus, there is no evidence that AMLEC is a lesion exclusive to TSC, with the majority of cases appearing to be sporadic (19).

In this case, ccRCC and AMLEC were identified in the upper and lower poles of the right kidney, respectively, occupying distinct anatomical regions. This necessitates differentiation among collision tumors, composite tumors, and synchronous tumors (37). Collision tumors are defined as the simultaneous presence of multiple tumors of different types in the same part of the same kidney, which are histologically distinct in origin and non-confluent. Composite tumors consist of two morphologically and immunohistochemically distinct tumor types within the same mass, often representing divergent differentiation of a single neoplasm. In contrast, synchronous tumors refer to the presence of two different tumors diagnosed simultaneously or within a short time frame, with well-demarcated borders, occurring in separate regions of the same organ or in different anatomical sites. Therefore, based on the above definitions, they were identified as synchronous renal tumors.

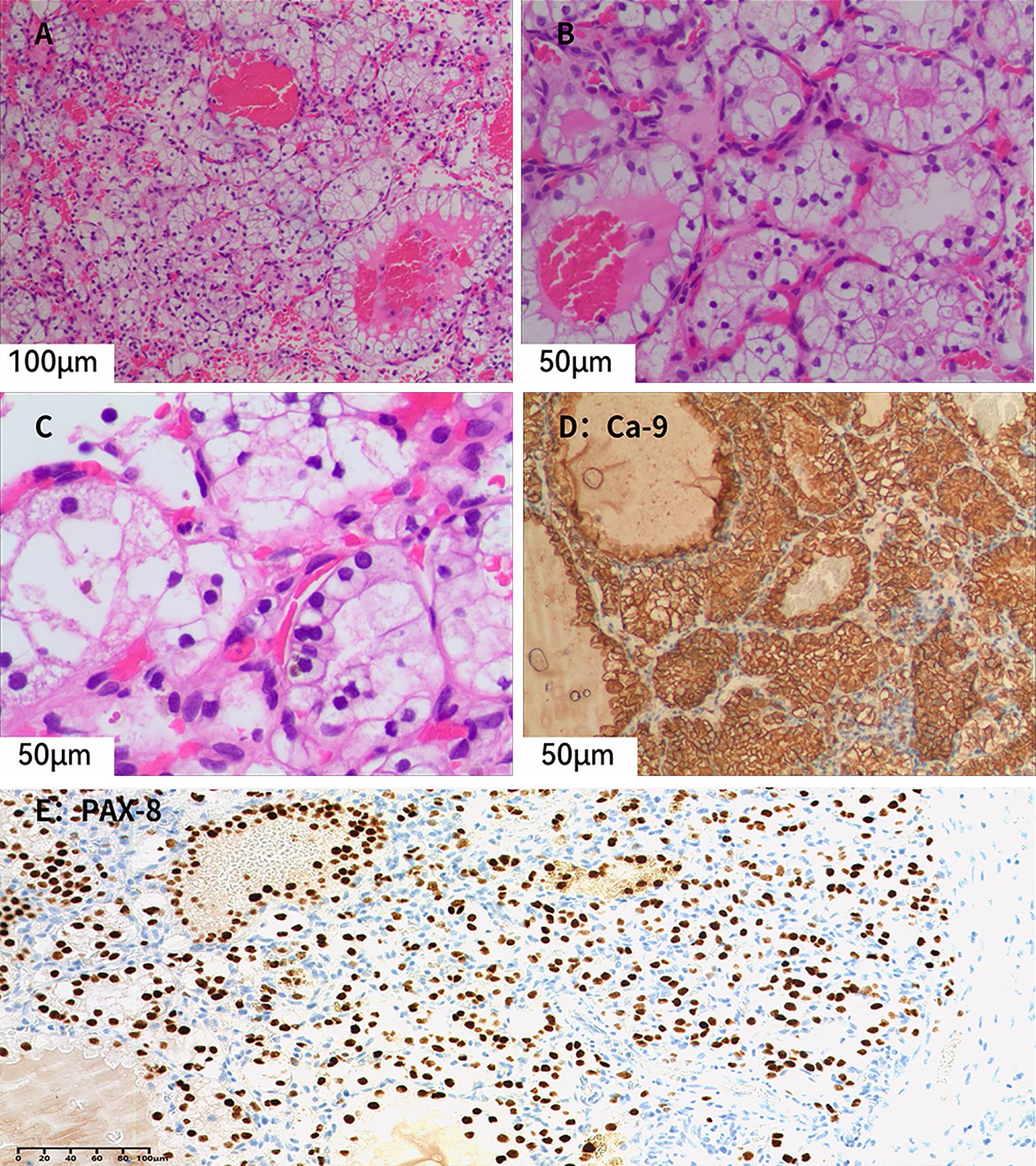

Synchronous renal tumors have been widely reported; however, synchronous AMLEC tumors are exceptionally rare, with only five cases documented to date (Table 1). To our knowledge, this case represents the sixth reported instance and the first documented occurrence of a synchronous tumor involving both AMLEC and ccRCC. Previous studies have described synchronous tumors comprising AML and ccRCC, which are classified as rare clinical entities (38). Additionally, Sakr et al. (39) noted that synchronous but histologically distinct in origin ipsilateral renal tumors constitute a rare phenomenon. The synchronous tumors in this case have different histological origins, and their prognosis and clinical management are challenging.

Solitary AMLEC exhibits favorable biological behavior, with no reported cases of recurrence or metastasis. Surgical intervention, including nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy, is the mainstay of treatment for large or symptomatic AMLEC, as demonstrated in our case (27). For patients with asymptomatic or tumors less than 4 cm in diameter, close follow-up observation is a viable option. When tumor diameter exceeds 4 cm, either surgical resection or selective arterial embolization may be considered to mitigate the risk of hemorrhage due to tumor rupture (20, 32). Additionally, for TSC-associated renal AMLEC, mTOR inhibitors may serve as a therapeutic option (41).

In cases where AMLEC coexists with malignant lesions such as ccRCC, treatment should prioritize the malignant component. For synchronous ipsilateral renal tumors, nephron-sparing surgery achieves tumor-specific survival rates comparable to those of radical nephrectomy (42, 43). While partial nephrectomy and focal ablation therapies offer advantages in preserving renal function, radical nephrectomy remains a reasonable option for complex or indistinguishable lesions. The surgical approach should be individualized based on the size, location, and presumed pathology of the synchronous tumors (44). Given the limited long-term data on synchronous renal tumors, further research is warranted to refine treatment strategies and evaluate disease progression in these rare cases.

5 Conclusions

AMLEC is a rare subtype of AML rather than a primary cystic lesion. Due to its lack of distinctive clinical and imaging features, preoperative diagnosis is challenging, with definitive diagnosis relying on postoperative histopathological examination and immunohistochemical analysis. Future research should further investigate the role of TSC1/TSC2 gene mutations in AMLEC to elucidate its molecular mechanisms and clinical significance in its pathogenesis. This study underscores the importance of managing rare cystic renal tumors and highlights the need for accurate differentiation between collision tumors, composite tumors, and synchronous tumors during diagnosis and treatment.

This study has certain limitations. The patient did not undergo TSC1/TSC2 genetic testing, which to some extent limited our ability to further analyze the molecular characteristics of AMLEC. Future investigations should prioritize targeted TSC1/TSC2 profiling to elucidate the potential contribution of TSC-pathway alterations to AMLEC pathogenesis.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University for the studies involving humans. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JW: Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. ZQ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JL: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – review & editing. GC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by General Program of Middle-aged and Young Research Fund of Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University (ASRF-2022-YB-05).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the colleagues in the Department of Pathology of Qinghai University Hospital that aided the efforts of the authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1618337/full#supplementary-material.

Supplementary Figure 1 | Timeline of the patient’s treatment.

References

1. Armah HB, Yin M, Rao UN, and Parwani AV. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts (AMLEC): a rare but distinct variant of angiomyolipoma. Diagn Pathol. (2007) 2:11. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-2-11

2. Acar T, Harman M, Sen S, Kumbaraci BS, and Elmas N. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cyst (AMLEC): A rare variant of fat poor angiomyolipoma mimicking Malignant cystic mass on MR imaging. Diagn Interv Imaging. (2015) 96:1195–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.03.005

3. Jinzaki M, Silverman SG, Akita H, Mikami S, and Oya M. Diagnosis of renal angiomyolipomas: classic, fat-poor, and epithelioid types. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. (2017) 38:37–46. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2016.11.001

4. Fine SW, Reuter VE, Epstein JI, and Argani P. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts (AMLEC): a distinct cystic variant of angiomyolipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. (2006) 30:593–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000194298.19839.b4

5. Davis CJ, Barton JH, and Sesterhenn IA. Cystic angiomyolipoma of the kidney: a clinicopathologic description of 11 cases. Mod Pathol. (2006) 19:669–74. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800572

6. Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, Epstein JI, Grignon D, et al. The international society of urological pathology (ISUP) vancouver classification of renal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. (2013) 37:1469–89. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1

7. Moch H, Amin MB, Berney DM, Comperat EM, Gill AJ, Hartmann A, et al. The 2022 world health organization classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. (2022) 82:458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.06.016

8. Mikami S, Oya M, and Mukai M. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts of the kidney in a man. Pathol Int. (2008) 58:664–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02287.x

9. Tajima S and Yamada Y. Cysts in angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts may be consisted of entrapped and dilated renal tubules: report of a case with additional immunohistochemical evidence to the pre-existing literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2015) 8:11729–34.

10. Karafin M, Parwani AV, Netto GJ, Illei PB, Epstein JI, Ladanyi M, et al. Diffuse expression of PAX2 and PAX8 in the cystic epithelium of mixed epithelial stromal tumor, angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, and primary renal synovial sarcoma: evidence supporting renal tubular differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. (2011) 35:1264–73. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822539a1

11. Kilic I, Segura S, Ulbright TM, and Mesa H. Immunophenotypic analysis of angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, comparison to mixed epithelial and stromal tumors and epithelial and stromal elements of normal kidney and ovaries. Virchows Arch. (2025) 486:233–41. doi: 10.1007/s00428-024-03827-3

12. Nezami BG and MacLennan GT. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review of its histopathology, genetics, and differential diagnosis. Int J Surg Pathol. (2024) 33:265–80. doi: 10.1177/10668969241256111

13. Dhanuka S, Kayal A, Mandal TK, and Dhanuka J. A rare case of bilateral synchronous renal tumors with different histology successfully treated with bilateral partial nephrectomy. J Cancer Res Ther. (2021) 17:593–5. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_605_18

14. Caban C, Khan N, Hasbani DM, and Crino PB. Genetics of tuberous sclerosis complex: implications for clinical practice. Appl Clin Genet. (2017) 10:1–8. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S90262

15. Varshney B, Vishwajeet V, Madduri V, Chaudhary GR, and Elhence PA. Renal angiomyolipoma with epithelial cyst. Autops Case Rep. (2021) 11:e2021308. doi: 10.4322/acr.2021.308

16. Gorin MA, Rowe SP, Allaf ME, and Argani P. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts: Add one to the differential of cystic renal lesions. Int J Urol. (2015) 22:1081–2. doi: 10.1111/iju.12908

17. LeRoy MA and Rao P. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2016) 140:594–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0170-RS

18. Rosenkrantz AB, Hecht EM, Taneja SS, and Melamed J. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts: mimic of renal cell carcinoma. Clin Imaging. (2010) 34:65–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2009.04.026

19. Wood A, Young F, and O'Donnell M. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts masquerading as a cystic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Urol. (2017) 9:209–11. doi: 10.1159/000447142

20. Yang X, Yu X, Zhang S, and Zhang Z. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts misdiagnosed as cystic renal carcinoma: A case report. Asian J Surg. (2024) 47:1571–3. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2023.12.016

21. Tufano A, Antonelli L, Di Pierro GB, Flammia RS, Minelli R, Anceschi U, et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the evaluation of small renal masses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). (2022) 12:2310. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12102310

22. Dipinto P, Canale V, Minelli R, Capuano MA, Catalano O, Di Pierro GB, et al. Qualitative and quantitative characteristics of CEUS for renal cell carcinoma and angiomyolipoma: a narrative review. J Ultrasound. (2024) 27:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s40477-023-00852-x

23. Tufano A, Drudi FM, Angelini F, Polito E, Martino M, Granata A, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the evaluation of renal masses with histopathological validation-results from a prospective single-center study. Diagnostics (Basel). (2022) 12:1209. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12051209

24. Sanz E, Hevia V, Gomez V, Alvarez S, Fabuel JJ, Martinez L, et al. Renal complex cystic masses: usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in their assessment and its agreement with computed tomography. Curr Urol Rep. (2016) 17:89. doi: 10.1007/s11934-016-0646-7

25. Zhang X, He XL, and Zhao M. Renal angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts: a clinicopathological analysis of four cases. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. (2020) 49:244–9.

26. Park BK. Renal angiomyolipoma: radiologic classification and imaging features according to the amount of fat. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2017) 209:826–35. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.17973

27. R V, Sharma P, Patel PA, and Patil P. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts: A rare but distinct variant of angiomyolipoma. Cureus. (2024) 16:e51824. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51824

28. McGuire BB and Fitzpatrick JM. The diagnosis and management of complex renal cysts. Curr Opin Urol. (2010) 20:349–54. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833c7b04

29. Negre T, Faure A, Andre M, Daniel L, Coulange C, and Lechevallier E. Renal angiomyolipomas without fat component: tomodensitometric and histologic characteristics, clinical course. Prog Urol. (2011) 21:837–41. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2011.06.006

30. Park BK. Renal angiomyolipoma based on new classification: how to differentiate it from renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2019) 212:582–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.20408

31. Rakowski SK, Winterkorn EB, Paul E, Steele DJ, Halpern EF, and Thiele EA. Renal manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: Incidence, prognosis, and predictive factors. Kidney Int. (2006) 70:1777–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001853

32. Xu Q, Yin L, Tao J, and Peng F. TSC1 splicing mutation in renal angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts without fat: A very rare case report and literature review. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e34191. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34191

33. Song H, Mao G, Jiao N, Li J, Gao W, Liu Y, et al. TSC2 nonsense mutation in angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1274953. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1274953

34. Brakemeier S, Bachmann F, and Budde K. Treatment of renal angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) patients. Pediatr Nephrol. (2017) 32:1137–44. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3474-6

35. Kang SG, Ko YH, Kang SH, Kim J, Kim CH, Park HS, et al. Two different renal cell carcinomas and multiple angiomyolipomas in a patient with tuberous sclerosis. Korean J Urol. (2010) 51:729–32. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.10.729

36. Cho WC, Collins K, Mnayer L, Cartun RW, and Earle JS. Concurrent eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma and angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts in the setting of tuberous sclerosis complex: A rare synchronous occurrence of 2 distinct entities. Int J Surg Pathol. (2019) 27:804–11. doi: 10.1177/1066896919849679

37. Lin Y, Guo J, Li Z, Liu Z, Xie J, Liu J, et al. Case report: A collision tumor of clear cell renal cell carcinoma and clear cell papillary renal cell tumor. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1284194. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1284194

38. Fekkar A, Znati K, Zouaidia F, Elouazzani H, Bernoussi Z, and Jahid A. Concurrent angiomyolipoma and clear cell renal cell carcinoma in the same kidney: A rare finding in a patient without tuberous sclerosis. Case Rep Urol. (2021) 2021:6663369. doi: 10.1155/2021/6663369

39. Sakr M, Badran M, Hassan SA, Elsaqa M, Elwany MA, Deeb N, et al. Detection of two synchronous histologically different renal cell carcinoma subtypes in the same kidney: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. (2024) 18:250. doi: 10.1186/s13256-024-04527-x

40. Takei K, Shimizu S, and Otsuki Y. Angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts (AMLEC) of the kidney. Hinyokika Kiyo. (2016) 62:355–60.

41. Osawa T, Oya M, Okanishi T, Kuwatsuru R, Kawano H, Tomita Y, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma by the Japanese Urological Association: Summary of the update. Int J Urol. (2023) 30:808–17. doi: 10.1111/iju.15213

42. Krambeck A, Iwaszko M, Leibovich B, Cheville J, Frank I, and Blute M. Long-term outcome of multiple ipsilateral renal tumours found at the time of planned nephron-sparing surgery. BJU Int. (2008) 101:1375–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07588.x

43. Minervini A, Serni S, Giubilei G, Lanzi F, Vittori G, Lapini A, et al. Multiple ipsilateral renal tumors: retrospective analysis of surgical and oncological results of tumor enucleation vs radical nephrectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. (2009) 35:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2008.06.003

Keywords: angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, angiomyolipoma, epithelial cysts, cystic renal cell carcinoma, renal synchronous tumors

Citation: Wang J, Ren C, Qiang Z, Li J, Ren H, Chen G, Gong X and Zhang J (2025) Synchronous angiomyolipoma with epithelial cysts and clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Front. Oncol. 15:1618337. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1618337

Received: 25 April 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025; Revised: 15 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Mottaran Angelo, University of Bologna, ItalyReviewed by:

Rahul Mannan, University of Michigan, United StatesCalogero Catanzaro, University of Bologna, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Wang, Ren, Qiang, Li, Ren, Chen, Gong and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chengde Ren, cjE4Njk3MjM5NTk2QDEyNi5jb20=

Jian Wang

Jian Wang Chengde Ren

Chengde Ren Ziyang Qiang2

Ziyang Qiang2 Guojun Chen

Guojun Chen Xue Gong

Xue Gong Jiaxin Zhang

Jiaxin Zhang