- 1College of Natural and Health Sciences, Southeastern University, Lakeland, FL, United States

- 2Department of Pediatric Oncology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

- 3Department of Global Pediatric Medicine, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, United States

Background: Subspecialization and centralization increase the quality of care in many medical subspecialties. It is expected to be standard of care in high-income countries. However, studies addressing the effect of subspecialization and centralization on the quality of pediatric neuro-oncology care in low-resource settings are lacking.

Methods: We determined the impact of subspecialization and centralization of pediatric neuro-oncology services on quality of care, survival outcomes, and quality of life by searching the Medline/PubMed literature database to identify relevant articles. We conducted this search using multiple English terms and keywords.

Results: Pediatric brain tumors are rare, and the care of pediatric neuro-oncology patients is complex and requires a multidisciplinary team. Established pediatric neuro-oncology programs greatly increase patient survival, outcomes, quality of care, and hospital volume. Barriers to centralization may include the distance to travel and the financial burden of that travel, which could lead to underserved populations.

Conclusions: Subspecialization and centralization of pediatric neuro-oncology services improves quality of care and patient outcome. More prospective research in this area is needed to determine the true impact of subspecialization and centralization in pediatric neuro-oncology in low-resource settings.

1 Introduction

Survival of children with cancer continues to improve as more advanced, effective therapies are developed. However, this improvement is mostly benefiting those children in high-income countries (HICs) (1). Where a child is born and resides is still a major predictive measure of survival (2). More than 211,080 children receive a cancer diagnosis each year, and more than 80% of those children live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where only approximately 20% of patients with cancer survive (3–8). The objective of the World Health Organization’s Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer is to achieve at least 60% survival for pediatric patients with cancer globally by 2030 (8). One strategy to help close this gap in survival between HICs and LMICs is the subspecialization and centralization of pediatric cancer care.

Subspecialization and centralization promote the pooling of expertise and resources, including therapeutic interventions, at a high-volume treatment center, which in turn increases the quality of care. Some of the many benefits of this include improved patient satisfaction, ease of providers staying current in the discipline, confidence in patient management, depth of expertise in the clinical team, efficiency in tumor boards, increased overall referrals, and increased access to clinical trials (9, 10). Many studies have shown positive results in outcomes, including survival, of patients due to subspecialization and centralization and in increasing patient volume in adult oncologic care (11–16).

Although there is paucity in literature on the centralization of pediatric oncologic care, centralization of care in cancer centers provides better outcomes and increased use of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, compared to that in noncancer centers (17). Recent examples of successful centralization of pediatric oncology programs in HICs can be seen in The Netherlands at Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology (8, 18) and in Hungary, where the Hungarian Pediatric Oncology Network provides centralized treatment (19).

2 Literature search strategy

This was a non-systematic review. The Medline/PubMed literature database was searched to identify relevant articles by using multiple English terms and keywords (Sub-specialization, Centralization, Pediatric(s), Volume, Neuro-oncology, Radiology, Diagnostic Imaging, Surgery, Pathology, Oncology, Radiation Oncology, Nursing, Palliative Care, Intensive Care Unit, Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, etc.). No date limits were set, and only English references were used. Additionally, the review included a nonsystematic selection of relevant publications. Additional articles were then identified in the reference lists of the initial publications selected. The articles were screened by two individuals. Relevant articles were exported into Zotero software for citation management. The search continued through August 11, 2023.

3 Results

3.1 Radiology

Sub specialization and centralization promote and thrive on a multidisciplinary team approach, in which all disciplines, including radiology, communicate with each other to ensure the most accurate and highest quality care (19). An effective radiology team is complex and expensive, as it includes radiologists, nuclear medicine physicians, imaging radiographers, technologists, medical physicists, and radiochemists, among others (20). Atun R et al. (21) noted the necessity of medical imaging as a cornerstone of many oncological services. Radiology is required in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer for accurate clinical management decision making by the multidisciplinary team and optimal outcomes for the patient (20). In many cancer types, early diagnosis and proper disease staging enhance the likelihood of survival (22). Unfortunately, misdiagnoses are not uncommon, causing patients to endure unneeded, and sometimes harmful, treatment, extra costs for the families and the hospitals, and even further delay of the correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment (23).

Sub specialization and centralization can help alleviate this common dilemma in oncology by working to ensure proper diagnostic imaging and earlier diagnosis. Studies have shown major differences between initial radiologist reports and subspecialty radiologist interpretations of imaging after referral (23, 24), indicating that a second opinion by a centralized radiology team has a positive impact on accurate diagnosis and patient care. This benefit may be even greater if done earlier in the course of illness. Additionally, sub specialization and centralization of pediatric oncology radiologists can decrease hospital costs by centrally reviewing images obtained at other institutions for patients who have been referred, instead of repeating the imaging examinations (23). The Institute of Medicine (25) reported that about 25% of patients undergo unnecessary repeated tests, including imaging (26), leading to inflated costs. Establishing a centralized team of specialty-trained pediatric radiologists can reduce such unnecessary costs. In large countries, like India, Indonesia, and Ethiopia, a network of different tier centers (primary, secondary, and tertiary) can be established, and utilization of telemedicine could help to address the issue.

Sub specialization and centralization of radiology also may increase patient volume from an increase in referrals (27), leading to a more reliable supply chain for imaging diagnostics (20), a more accurate perception of epidemiology of rare tumor subtypes not usually seen in smaller centers and improved collection and storage of imaging data, which helps with long-term follow-up (8). Additionally, by establishing centralized pediatric neuro-oncology specialized radiology, survival can be improved, as seen in a study on centralized neuroradiographic review in the United States (28). In a clinical trial of patients with average-risk medulloblastoma, 17% had images that, upon review, were considered incomplete or of poor quality, and when those patients’ survival was compared with that of patients with eligible, fully assessable images, those with incomplete or poor-quality images had poorer event-free survival (28). Additionally, 10% of the patients in the study were excluded after central radiologic review, because they had disseminated or residual disease. These patients were undertreated, which significantly decreased their probability of survival (28). A subspecialized and centralized pediatric neuro-oncology radiology center also positively influences surgical outcomes (20).

3.2 Surgery

Many studies have shown that surgical procedures performed in high-volume centers have a higher survival rate and better outcomes, compared to those performed in low-volume centers (18, 29–36). The same has been found for individual surgeons who have performed high volumes of procedures and have more experience (29–31, 33, 35, 37). The centralization of pediatric surgical care in The Netherlands in Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology had a positive effect on both intraoperative and postoperative complications, mortality, and morbidity, when compared to pre-centralization data (18). Improvements in the care given at high-volume centers may be attributed to the skills of the staff, nursing team, and all related specialties, large number of operations, neurological intensive care unit, and high-quality advanced equipment (32). Additionally, sub specialization and centralization increase referrals, which in turn increases the experience of surgeons and hospital volume (32).

Sub specialization and high patient volume make acquiring equipment cost effective. For these reasons, surgical and radiological sub specialization and centralization should be linked because they enable hospitals to have better, more cost-effective resources (17). Another advantage of such an approach in high-volume centers is the networking among centers of excellence (32). In pediatric neuro-oncology, sub specialization and centralization of surgery offers a more aggressive approach towards many tumor resections; this is important in cancers in which survival is associated with complete resection (37, 38). One study comparing pediatric neurosurgery outcomes with surgeon experience/specialty found that the amount of residual tumor was related to the type of neurosurgeon (general, pediatric, or ASPN [American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons] member) who performed the procedure.

Pediatric neurosurgeons are more likely to extensively remove pediatric brain tumors than are general neurosurgeons. Additionally, lower neurological morbidity is associated with greater neurosurgical experience (e.g., ASPN members) (37). The mean number of operations performed by individual surgeons increased with sub specialization; individual general neurosurgeons perform fewer operations than do ASPN members (37).

Another study examined postoperative posterior fossa syndrome in patients with medulloblastoma; the authors found that younger age and having an operation in a low-volume center or by a low-volume surgeon increased the likelihood of posterior fossa syndrome (31). After sub specialization and centralization of pediatric brain tumor resections, mortality decreased (33). Additionally, lower rates of second brain tumor resection were associated with high surgical volumes, which can lead to lower costs in high-volume centers than in low-volume centers (34). Pediatric oncologic care (including surgery) is one of the most complex subspecialties of medical care; therefore, such cases favor centralization of care to surgical centers with high volume (34).

3.3 Pathology

Pathologic assessment of tissue plays a vital role in diagnosis, staging, treatment, and prognosis (39, 40), and histopathologic evaluation of tumor tissue is typically required to confirm oncologic diagnosis (39). With increasingly smaller tissue samples needed for histopathologic examination, the centralized management of those specimens helps optimize the number of examinations that can be done on the tissue sample (41). This can be achieved through specialized standard operating procedures, policies, and protocols.

One study showed that after tissue-specific protocols were implemented, quality of care increased through improved and complete pathology reporting, which led to better interpretations of pathologic findings by the clinicians (42). Pathologists play a crucial role in communicating results with clinicians (40, 41, 43). Cancer diagnosis has changed from morphology-based classification, through microscopic examinations, to a molecular-based discipline (43). Many cancers are genetically driven, and over the last few decades, targeted therapies have been developed, forcing a more specific and stratified oncologic diagnosis (43). Successful treatment depends on pathologic diagnosis (44); furthermore, better outcomes are associated with accurate stratification of treatment (42). New high-throughput technologies are becoming essential for diagnosis of oncologic pathology (43, 45, 46). Sub specialization and centralization of pathology services can be an effective way for LMICs to access new, innovative technologies.

A useful strategy for resource-limited settings is seeking a second opinion, which can lower the risk of misdiagnosis and the necessity to later amend diagnoses (44, 47, 48). The accuracy of diagnosis can be evaluated by telepathology through twinning programs; the concordance rates of accuracy are similar in both static (pictures) and dynamic (real-time video) consultations (46). Sub specialization and centralization of pathology can be implemented into LMICs through collaborations with pathologists in HICs for intensive specialty training and second opinion telepathology (49).

One study demonstrated that in low-resource settings, an intensive 6-month training specifically tailored to local needs, as opposed to full subspecialty training, provided a sufficient foundation for accurate diagnoses of pediatric cancer (46). Neuro-oncological diagnoses have very specific histologic features that can be present due to genetic, environmental, or reactive causes, among others. One study in the United States found that after a central, independent pathologic review, 28% of high-grade glioma diagnoses were reclassified as low-grade glioma (50). Those 28% of children with low-grade glioma, whose follow-up after a near-complete resection should have been monitored only, received unnecessary chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which put them at risk of acute and long-term adverse late effects. In addition, the misdiagnoses added an unnecessary extra cost burden on health care systems.

3.4 Neuro-oncology

Pediatric neuro-oncology is a nontechnical discipline, and the limited literature makes it difficult to quantify the impact of sub specialization and centralization of pediatric neuro-oncologists. Oncologists in LMICs typically have a heavy workload (42), with no extra time for fellowship training for sub specialization (46). Many academic hospitals in LMICs also do not have the resources to fund a full fellowship (46). An intensive 6-month specialty training was established in Brazil as a model for other low-resource settings (46). Although this model was used to train a general pathologist in pediatric cancer pathology, one can assume that it can also be used to train general oncologists to be pediatric neuro-oncologists.

The St. Jude Global Academy established the Neuro-Oncology Training Seminar as a multidisciplinary course on pediatric neuro-oncology for physicians in LMICs (51). Upon completion of the 9-week online course and the 7-day in-person workshop, physicians showed a significant improvement in comprehension of the core elements of pediatric neuro-oncology. In addition to this Academy, virtual clinical fellowship opportunities have been established through St. Jude Global and partners around the world (52). Using these novel approaches is important, because clinical fellows from LMICs who complete their medical training in HICs often decline the invitation to return to their country of origin, or they return but then leave after practicing for only a few years (53).

3.5 Radiation oncology

Radiation therapy is a vital element of the multidisciplinary clinical management of many pediatric cancers (54). The late adverse effects of radiation have been more clearly discerned as long-term survival of pediatric brain tumors has increased (55). Survivors of childhood brain tumors are at risk for neurocognitive, endocrine, and growth sequelae due, in part, to cranial radiation therapy (28, 54, 56). The amount and type of radiation administered are determined by the pathology, tumor location, disease progression, and age of the child (57). Large fields and high doses of radiation were used previously to treat pediatric brain tumors; however, severe late effects were seen in the first generation of survivors (55). Additionally, one study of patients with medulloblastoma showed that 71% of patients had at least one deviation in radiation, and seven patients did not receive the protocol-specified dose of radiation (58).

Because marginal deviations in radiation therapy are strongly correlated with risk of relapse (58), centralization and sub specialization are essential to ensure high quality treatment. Variations in outcome (54) indicate the need for sub specialization and centralization of radiation therapy for pediatric neuro-oncology patients; specific treatment protocols are not sufficient to positively affect quality of care without the presence of a multidisciplinary team. One important aim of radiation therapy in pediatric neuro-oncology has been to reduce the field of radiation and dose (55). Image-guided radiation therapy increases the accuracy of treatment by reducing the margin of healthy cells in the radiation beam and enabling increased dosage to the target area (54, 55). Having a specialized radiation oncologist makes this major advance possible because many technical skills are required (54).

These findings support the centralization of radiation treatment in cancer centers for an expansion of access to new, expensive resources in LMICs (59). Although 85% of the world’s population resides in LMICs, only about 33% of all radiation therapy facilities are in LMICs (60). Radiation therapy is cost-effective because of the high volume of patients a facility can treat and the long life of the equipment (21, 60). Twinning programs can also help establish radiation therapy centers and expertise in safe radiation therapy, while adapting to local and regional needs (21, 54).

3.6 Palliative care

Palliative care is a key component of comprehensive cancer care (59). It requires a broad, holistic, interdisciplinary approach for pain management, attending to suffering, home-based and hospice services, and bereavement (5, 10, 25, 59, 61, 62). Unfortunately, access to palliative care subspecialty is quite rare in LMICs, and if it is available, it is only at larger, more centralized locations (63). A major aspect of palliative care is to help clarify goals of treatment and care between clinicians and the patients and/or their families, which is vital throughout the illness experience (64, 65). The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatric palliative care begin at the time of the cancer diagnosis (5). Early involvement of palliative care is important for many reasons, including that children with malignant brain tumors commonly suffer from loss of their ability to communicate and present with severe symptoms at the end of life (25, 62, 66–68). Additionally, with early involvement of palliative care, advanced care planning improves, as discussions between the health care team and the patient and/or their family occur more frequently and earlier before death (69).

In patients with high-grade gliomas, palliative care consultations are associated with early change of code status to DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) and the increased use of hospice (70). Additionally, early integration promotes the continuation of relationships between the multidisciplinary team (including palliative care specialists) and the family, while avoiding the transfer of care or the introduction of new palliative care specialists during the last days of a child’s life (67). Palliative care consultations are associated with a shorter duration of stay in the hospital without any effect on mortality, and fewer deaths in the intensive care unit (64, 69). Integration of palliative care can also improve the quality of life by using less-aggressive treatment at the end of life and can improve survival (71). Interestingly, after the integration of palliative care, the number of hospital admissions at the end of life may be reduced (69); this was especially true for children with brain tumors (72). One study in Italy found that after the integration of palliative care, none of the patients with brain tumors had uncontrolled pain; almost 60% of patients received palliative sedation, and 44% died at home (66).

Pediatric palliative care includes patients and parents in clinical decision making; the wishes of the patient and/or parents are considered (65). Parents feel more comfortable discussing death with their child after consultations with the palliative care team (61). From the parents’ point of view, clear and honest communication from the doctor about their child’s prognosis is one of the strongest determinants of high-quality physician care (73). For parents of children with cancer, preparedness may be their only sense of control over unpredictable and devastating circumstances (73). Integrating palliative care aids in the grief and bereavement journey of surviving family members (68).

3.7 Supportive therapies

As the incidence and survival of pediatric brain tumors are increasing, supportive therapies, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, neuropsychology, dental service, optometry, and audiometry, continue to be essential (74–77). Treatments for brain tumors can cause detrimental sequelae, including neurocognitive deficits, neurologic complications, endocrine abnormalities, gastrointestinal impairments, eye-related complications, and hearing loss (56, 74, 76, 78–81). For example, posterior fossa syndrome arises postoperatively in 40% of children with brain tumors located in the posterior fossa and presenting symptoms of impaired communication (often mutism), depressed mood, and loss of motor skills (82). Neuropsychological evaluations and interventions improve outcomes in pediatric neuro-oncology patients (56, 57, 83). Incorporating inpatient rehabilitation for patients with neurological disabilities due to brain tumors can also lead to functional improvement in activities of daily living (79, 84). Rehabilitation specialists in multiple disciplines (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy) are required to optimize overall patient function (74). Early identification of these sequelae is vital to optimize normal speech, communication, language development, and social interactions for improved quality of life (85).

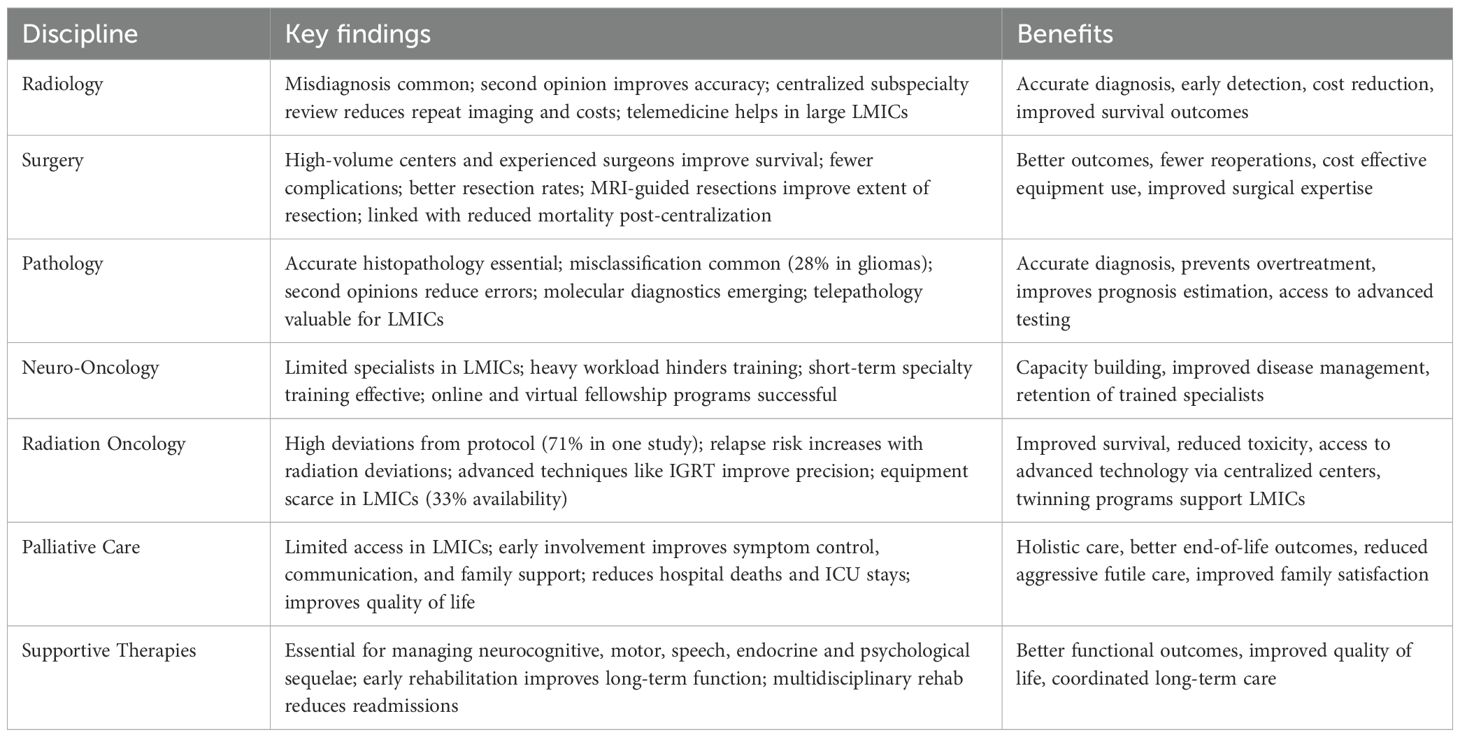

The Rehabilitation Medicine Department of the Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health suggests integrating rehabilitation care from diagnosis and throughout the patient’s journey (86). The oncology team must screen patients for levels of function to ensure accurate and timely referral during the course of treatment and long-term follow-up (74, 77). Including rehabilitation providers on the multidisciplinary teams/rounds supports patients and families by ensuring consistent care providers throughout treatment (75), coordinated scheduling of rehabilitation services and anticancer treatment (74, 87), and improved discharge planning that can reduce the likelihood of re-admission to acute care (75, 87) and promote successful school transitions (88) (Table 1).

Table 1. Depicts the key findings of every discipline and benefits of sub specialization and centralization of pediatric neuro-oncology services.

4 Discussion

Sub specialization and centralization have been used as a strategy to reduce the disparity in survival of children with cancer in LMICs versus those in HICs and has led to increased volume, development of molecular diagnostics, innovative treatments, and outcomes comparable to those in HICs (89). Sub specialization and centralization of rare, complex, and multidisciplinary specialties, like pediatric neuro-oncology, will help increase the quality of care and patient outcome. LMICs that have established pediatric neuro-oncology programs include Malaysia (51), Jordan (89), and Pakistan (90). After the establishment of these programs, survival and patient volume significantly increased, in terms of steep increase in referrals, better tumor board participation, and providing best-possible available treatment options in resource-constrained settings. Sub-specialized and centralized pediatric neuroradiology, surgery, pathology, oncology, radiation oncology, nursing, palliative care, intensive care, and rehabilitation services are all necessary aspects of multidisciplinary care in pediatric neuro-oncology. The concept of decentralization is appealing for LMIC governments; however, for rare diseases like pediatric brain tumors, sub specialization and centralization of services deceases the chances of relapse by providing good staging (28), correct diagnosis (50), and proper therapies upfront (18). It also decreases morbidity and complications (31, 37) and avoids unnecessary therapies (50), which translates to less short- and long-term costs. Governments and tertiary centers should be sensitive to local needs and the burden of travel, losing working time, and housing, so centralization does not become a burden on patients and families. In LMIC, a hub and spoke model connects resource-rich central facilities like tertiary cancer care hospitals (hubs) with peripheral facilities like primary and secondary care hospitals (spokes) to improve healthcare delivery. The hub provides technical expertise, training, and materials, while the spokes offer basic services, creating a system where specialized care can reach underserved areas through methods like emergency services and elective patient transfers. This model is well-suited for areas like cancer care and acute coronary syndromes to ensure best outcomes.

5 Conclusions

Caring for pediatric neuro-oncology patients is complex and requires a multidisciplinary team of radiologists, surgeons, pathologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, nurses, palliative care specialists, intensivists, and therapists, among others. Sub specialization and centralization promote high-quality communication and collaboration among multidisciplinary care providers. In low-resource settings and many LMICs, sub specialization and centralization are an effective use of resources to improve quality of care for the many patients in areas where they previously did not have access to multidisciplinary care, thereby ensuring early diagnosis and effective treatment. Additionally, twinning programs and telemedicine are an effective way to help establish pediatric neuro-oncology programs in low-resource settings. Effective twinning and other models continue to close the gap in survival of children with brain tumors in HICs and those in LMICs. Although sub specialization and centralization have been successful, barriers to centralization may include the distance to travel and financial burden associated with that travel, which could lead to underserved care. Thus, housing, transportation, and financial support for patients should be considered when establishing a centralized pediatric neuro-oncology service in low-resource settings. More prospective research in this area is needed to determine the true impact of sub specialization and centralization on quality of care, survival, and psychosocial outcomes in pediatric neuro-oncology. Smaller LMICs could follow Netherlands steps in its novel approach to childhood cancers–one pediatric cancer hospital for the whole country while for larger LMIC model like hub and spoke could be beneficial where there is a regional center for excellence which could be the hub.

6 Limitations

As the review is non-systematic, the limitations include the lack of a standardized, transparent, and comprehensive methodology, leading to potential bias, inconclusive results, and an inability to fully assess the quality of the included studies.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. DM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation. IQ: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities and Angela McArthur for editing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors DM.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Bhakta N, Force LM, Allemani C, Atun R, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. Childhood cancer burden: a review of global estimates. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:e42–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30761-7

2. Goss PE, Lee BL, Badovinac-Crnjevic T, Strasser-Weippl K, Chavarri-Guerra Y, St Louis J, et al. Planning cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. (2013) 14:391–436. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70048-2

3. Rodriguez-Galindo C, Friedrich P, Alcasabas P, Antillon F, Banavali S, Castillo L, et al. Toward the cure of all children with cancer through collaborative efforts: pediatric oncology as a global challenge. J Clin Oncol. (2015) 33:3065–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6376

4. Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, Shulman LN, Alleyne G, Armstrong L, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. (2010) 376:1186–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61152-X

5. Baker JN, Levine DR, Hinds PS, Weaver MS, Cunningham MJ, Johnson L, et al. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care. J Pediatr. (2015) 167:467–470.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.05.002

6. Atun R, Bhakta N, Denburg A, Frazier AL, Friedrich P, Gupta S, et al. Sustainable care for children with cancer: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:e185–224. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30022-X

7. Bouffet E, Amayiri N, Fonseca A, and Scheinemann K. Pediatric neuro-oncology in countries with limited resources. In: Scheinemann K and Bouffet E, editors. Pediatric Neuro-Oncology. Switzerland AG: Springer Nature Springer (2015). p. 299–307.

8. Wang M, Bi Y, Fan Y, Fu X, and Jin Y. Global incidence of childhood cancer by subtype in 2022: a population-based registry study. eClinicalMedicine. (2025) 89:103571. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2025.103571

9. Gesme DH and Wiseman M. Subspecialization in community oncology: option or necessity? J Oncol Pract. (2011) 7:199–201. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000292

10. Abdel-Baki MS, Hanzlik E, and Kieran MW. Multidisciplinary pediatric brain tumor clinics: the key to successful treatment? CNS Oncol. (2015) 4:147–55. doi: 10.2217/cns.15.1

11. Taylor C, Shewbridge A, Harris J, and Green JS. Benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork in the management of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Dove Med Press. (2013) 5:79–85. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S35581

12. Korkes F, Timóteo F, Martins S, Nascimento M, Monteiro C, Santiago JH, et al. Dramatic impact of centralization and a multidisciplinary bladder cancer program in reducing mortality: The CABEM Project. JCO Glob Oncol. (2021) 7:1547–55. doi: 10.1200/GO.21.00104

13. Dahm-Kähler P, Palmqvist C, Staf C, Holmberg E, and Johannesson L. Centralized primary care of advanced ovarian cancer improves complete cytoreduction and survival - A population-based cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. (2016) 142:211–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.025

14. Gooiker GA, van der Geest LG, Wouters MW, Vonk M, Karsten TM, Tollenaar RA, et al. Quality improvement of pancreatic surgery by centralization in the western part of the Netherlands. Ann Surg Oncol. (2011) 18:1821–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1511-4

15. Wouters MW, Karim-Kos HE, le Cessie S, Wijnhoven BP, Stassen LP, Steup WH, et al. Centralization of esophageal cancer surgery: does it improve clinical outcome? Ann Surg Oncol. (2009) 16:1789–98. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0458-9

16. Pfister DG, Rubin DM, Elkin EB, Neill US, Duck E, Radzyner M, et al. Risk adjusting survival outcomes in hospitals that treat patients with cancer without information on cancer stage. JAMA Oncol. (2015) 1:1303–10. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3151

17. Kramer S, Meadows AT, Pastore G, Jarrett P, and Bruce D. Influence of place of treatment on diagnosis, treatment, and survival in three pediatric solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. (1984) 2:917–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.8.917

18. Roy P, van Peer SE, de Witte MM, Tytgat GAM, Karim-Kos HE, van Grotel M, et al. Characteristics and outcome of children with renal tumors in the Netherlands: The first five-year’s experience of national centralization. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0261729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261729

19. Jakab Z, Garami M, Bartyik Monika K C, Daniel Janos E, and Peter H. Late mortality in survivors of childhood cancer in Hungary. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67444-1

20. Hricak H, Abdel-Wahab M, Atun R, Lette MM, Paez D, Brink JA, et al. Medical imaging and nuclear medicine: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:e136–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30751-8

21. Atun R, Jaffray DA, Barton MB, Bray F, Baumann M, Vikram B, et al. Expanding global access to radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:1153–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00222-3

22. Singh H, Sethi S, Raber M, and Petersen LA. Errors in cancer diagnosis: current understanding and future directions. J Clin Oncol. (2007) 25:5009–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2142

23. Hatzoglou V, Omuro AM, Haque S, Khakoo Y, Ganly I, Oh JH, et al. Second-opinion interpretations of neuroimaging studies by oncologic neuroradiologists can help reduce errors in cancer care. Cancer. (2016) 122:2708–14. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30083

24. Eakins C, Ellis WD, Pruthi S, Johnson DP, Hernanz-Schulman M, Yu C, et al. Second opinion interpretations by specialty radiologists at a pediatric hospital: rate of disagreement and clinical implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. (2012) 199:916–20. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7662

25. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America (2013). National Academies Press (US. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/ (Accessed August 14, 2024).

26. Sammer MBK and Kan JH. Providing second-opinion interpretations of pediatric imaging: embracing the call for value-added medicine. Pediatr Radiol. (2021) 51:523–8. doi: 10.1007/s00247-019-04596-x

27. Al-Qudimat MR, Day S, Almomani T, Odeh D, and Qaddoumi I. Clinical nurse coordinators: a new generation of highly specialized oncology nursing in Jordan. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2009) 31:38–41. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31818b3536

28. Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, Rorke-Adams L, Burger PC, Robertson PL, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. (2006) 24:4202–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980

29. Sanford RA. Craniopharyngioma: results of survey of the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgery. Pediatr Neurosurg. (1994) 21:39–43. doi: 10.1159/000120860

30. Safford SD, Pietrobon R, Safford KM, Martins H, Skinner MA, and Rice HE. A study of 11,003 patients with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and the association between surgeon and hospital volume and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. (2005) 40:967–972; discussion 972–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.011

31. Khan RB, Patay Z, Klimo P, Huang J, Kumar R, Boop FA, et al. Clinical features, neurologic recovery, and risk factors of postoperative posterior fossa syndrome and delayed recovery: a prospective study. Neuro-Oncol. (2021) 23:1586–96. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab030

32. Bachmann M, Peters T, and Harvey I. Costs and concentration of cancer care: evidence for pancreatic, oesophageal and gastric cancers in National Health Service hospitals. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2003) 8:75–82. doi: 10.1258/135581903321466030

33. Smith ER, Butler WE, and Barker FG. Craniotomy for resection of pediatric brain tumors in the United States, 1988 to 2000: effects of provider caseloads and progressive centralization and specialization of care. Neurosurgery. (2004) 54:553–563; discussion 563–565. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000108421.69822.67

34. Choi Hr, Song IA, and Oh TK. Association between surgical volume and outcomes after craniotomy for brain tumor removal: A South Korean nationwide cohort study. J Clin Neurosci. (2022) 100:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2022.04.007

35. Cowan JA, Dimick JB, Leveque JC, Thompson BG, Upchurch GR, and Hoff JT. The impact of provider volume on mortality after intracranial tumor resection. Neurosurgery. (2003) 52:48–53; discussion 53–54.

36. Berry JG, Hall MA, Sharma V, Goumnerova L, Slonim AD, and Shah SS. A multi-institutional, 5-year analysis of initial and multiple ventricular shunt revisions in children. Neurosurgery. (2008) 62:445–453; discussion 453–454. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000316012.20797.04

37. Albright AL, Sposto R, Holmes E, Zeltzer PM, Finlay JL, Wisoff JH, et al. Correlation of neurosurgical subspecialization with outcomes in children with Malignant brain tumors. Neurosurgery. (2000) 47:879–885; discussion 885–887. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200010000-00018

38. Assessing “second-look” tumour resectability in childhood posterior fossa ependymoma-a centralised review panel and staging tool for future studies - PubMed. Available online at (Accessed August 14, 2024).

39. Parra-Herran C, Romero Y, and Milner D. Pathology and laboratory medicine in cancer care: A global analysis of national cancer control plans. Int J Cancer. (2021) 148:1938–47. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33384

40. Raab SS, Grzybicki DM, Janosky JE, Zarbo RJ, Meier FA, Jensen C, et al. Clinical impact and frequency of anatomic pathology errors in cancer diagnoses. Cancer. (2005) 104:2205–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21431

41. Kremer LC, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, Bhatia S, Landier W, Levitt G, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2013) 60(4):543–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24445

42. Elzomor H, Taha H, Nour R, Aleieldin A, and Zaghloul MS. A multidisciplinary approach to improving the care and outcomes of patients with retinoblastoma at a pediatric cancer hospital in Egypt. Ophthalmic Genet. (2017) 38:345–51. doi: 10.1080/13816810.2016.1227995

43. Vranic S and Gatalica Z. The role of pathology in the era of personalized (precision) medicine: a brief review. Acta Med Acad. (2021) 50:47–57. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.325

44. Peck M, Moffat D, Latham B, and Badrick T. Review of diagnostic error in anatomical pathology and the role and value of second opinions in error prevention. J Clin Pathol. (2018) 71:995–1000. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205226

45. Schwabenland M, Brück W, Priller J, Stadelmann C, Lassmann H, and Prinz M. Analyzing microglial phenotypes across neuropathologies: a practical guide. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). (2021) 142:923–36. doi: 10.1007/s00401-021-02370-8

46. Santiago TC, Jenkins JJ, Pedrosa F, Billups C, Quintana Y, Ribeiro RC, et al. Improving the histopathologic diagnosis of pediatric Malignancies in a low-resource setting by combining focused training and telepathology strategies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2012) 59:221–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24071

47. Kronz JD and Westra WH. The role of second opinion pathology in the management of lesions of the head and neck. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2005) 13:81–4. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000156162.20789.66

48. Westra WH, Kronz JD, and Eisele DW. The impact of second opinion surgical pathology on the practice of head and neck surgery: a decade experience at a large referral hospital. Head Neck. (2002) 24:684–93. doi: 10.1002/hed.10105

49. Gilani A, Mushtaq N, Shakir M, Altaf A, Siddiq Z, Bouffet E, et al. Pediatric neuropathology practice in a low- and middle-income country: capacity building through institutional twinning. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1328374. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1328374

50. Fouladi M, Hunt DL, Pollack IF, Dueckers G, Burger PC, Becker LE, et al. Outcome of children with centrally reviewed low-grade gliomas treated with chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy on Children’s Cancer Group high-grade glioma study CCG-945. Cancer. (2003) 98:1243–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11637

51. Moreira DC, Gajjar A, Patay Z, Boop FA, Chiang J, Merchant TE, et al. Creation of a successful multidisciplinary course in pediatric neuro-oncology with a systematic approach to curriculum development. Cancer. (2021) 127:1126–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33350

52. Salman Z, Moreira D, Resendiz AB, Hoveyan J, Rahmartani L, Ain RU, et al. The St. Jude Global Virtual Pediatric Neuro-oncology Fellowship: a novel approach to increasing pediatric neuro-oncology capacity in low- and middle- income countries. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2024) 26(Suppl 4):0. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noae064.743

53. Gandy K, Castillo H, Rocque BG, Bradko V, Whitehead W, and Castillo J. Neurosurgical training and global health education: systematic review of challenges and benefits of in-country programs in the care of neural tube defects. Neurosurg Focus. (2020) 48:E14. doi: 10.3171/2019.12.FOCUS19448

54. Salminen E, Anacak Y, Laskar S, Kortmann RD, Raslawski E, Stevens G, et al. Twinning partnerships through International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to improve radiotherapy in common paediatric cancers in low- and mid-income countries. Radiother Oncol. (2009) 93:368–71. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.018

55. Bindra RS and Wolden SL. Advances in radiation therapy in pediatric neuro-oncology. J Child Neurol. (2016) 31:506–16. doi: 10.1177/0883073815597758

56. Tonning Olsson I, Perrin S, Lundgren J, Hjorth L, and Johanson A. Access to neuropsychologic services after pediatric brain tumor. Pediatr Neurol. (2013) 49:420–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.07.002

57. Fischer C, Petriccione M, Donzelli M, and Pottenger E. Improving care in pediatric neuro-oncology patients: an overview of the unique needs of children with brain tumors. J Child Neurol. (2016) 31:488–505. doi: 10.1177/0883073815597756

58. Carrie C, Hoffstetter S, Gomez F, Moncho V, Doz F, Alapetite C, et al. Impact of targeting deviations on outcome in medulloblastoma: study of the French society of pediatric oncology (SFOP)1. Int J Radiat Oncol. (1999) 45:435–9. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00200-X

59. Von Roenn JH. Palliative care and the cancer patient: current state and state of the art. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2011) 33:S87–89. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230dac8

60. Rodin D, Grover S, Elmore SN, Knaul FM, Atun R, Caulley L, et al. The power of integration: radiotherapy and global palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. (2016) 5:209–17. doi: 10.21037/apm.2016.06.03

61. Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, Brandstätter M, Borasio GD, and Führer M. Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med. (2012) 15:294–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0196

62. Frisella S, Bonosi L, Ippolito M, Giammalva GR, Ferini G, Viola A, et al. Palliative care and end-of-life issues in patients with brain cancer admitted to ICU. Med Kaunas Lith. (2023) 59:288. doi: 10.3390/medicina59020288

63. McNeil MJ, Ehrlich BS, Wang H, Vedaraju Y, Bustamante M, Dussel V, et al. Physician perceptions of palliative care for children with cancer in Latin America. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e221245. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1245

64. Pottash M, McCamey D, Groninger H, Aulisi EF, and Chang JJ. Palliative care consultation and effect on length of stay in a tertiary-level neurological intensive care unit. Palliat Med Rep. (2020) 1:161–5. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0051

65. Section on hospice and palliative medicine and committee on hospital care. Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics. (2013) 132:966–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2731

66. Vallero SG, Lijoi S, Bertin D, Pittana LS, Bellini S, Rossi F, et al. End-of-life care in pediatric neuro-oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2014) 61:2004–11. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25160

67. Veldhuijzen van Zanten SE, van Meerwijk CL, Jansen MH, Twisk JW, Anderson AK, Coombes L, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: results from a London cohort study and international survey. Neuro-Oncol. (2016) 18:582–8. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov250

68. Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AEL, and Bannister SL. Palliative care of children with brain tumors: a parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2010) 164:225–30. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.284

69. Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, Duncan J, Comeau M, Breyer J, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:1717–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0277

70. Rosenberg J, Massaro A, Siegler J, Sloate S, Mendlik M, Stein S, et al. Palliative care in patients with high-grade gliomas in the neurological intensive care unit. Neurohospitalist. (2020) 10:163–7. doi: 10.1177/1941874419869714

71. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

72. Fraser LK, van Laar M, Miller M, Aldridge J, McKinney PA, Parslow RC, et al. Does referral to specialist paediatric palliative care services reduce hospital admissions in oncology patients at the end of life? Br J Cancer. (2013) 108:1273–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.89

73. Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner B, Grier HE, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:9155–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010

74. Tanner L, Keppner K, Lesmeister D, Lyons K, Rock K, and Sparrow J. Cancer rehabilitation in the pediatric and adolescent/young adult population. Semin Oncol Nurs. (2020) 36:150984. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.150984

75. L’Hotta AJ, Beam IA, and Thomas KM. Development of a comprehensive pediatric oncology rehabilitation program. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2020) 67:e28083. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28083

76. Whelan KF, Stratton K, Kawashima T, Waterbor JW, Castleberry RP, Stovall M, et al. Ocular late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2010) 54:103–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22277

77. Knops RRG, van Dalen EC, Mulder RL, Leclercq E, Knijnenburg SL, Kaspers GJL, et al. The volume effect in paediatric oncology: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24:1749–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds656

78. Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Huang S, Ness KK, Leisenring W, et al. Long-term outcomes among adult survivors of childhood central nervous system Malignancies in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. (2009) 101:946–58. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp148

79. Philip PA, Ayyangar R, Vanderbilt J, and Gaebler-Spira DJ. Rehabilitation outcome in children after treatment of primary brain tumor. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (1994) 75:36–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(94)90334-4

80. Vargo M. Brain tumor rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2011) 90:S50–62. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31820be31f

81. Hua C, Bass JK, Khan R, Kun LE, and Merchant TE. Hearing loss after radiotherapy for pediatric brain tumors: effect of cochlear dose. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2008) 72:892–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.050

82. Parent E and Scott L. Pediatric posterior fossa syndrome (PFS): nursing strategies in the post-operative period. Can J Neurosci Nurs. (2011) 33:24–31.

83. Walsh K, Noll R, Annett R, Patel S, Patenaude A, and Embry L. Standard of care for neuropsychological monitoring in pediatric neuro-oncology: Lessons from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2016) 63:191–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25759

84. Formica V, Del Monte G, Giacchetti I, Grenga I, Giaquinto S, Fini M, et al. Rehabilitation in neuro-oncology: a meta-analysis of published data and a mono-institutional experience. Integr Cancer Ther. (2011) 10:119–26. doi: 10.1177/1534735410392575

85. Grewal S, Merchant T, Reymond R, McInerney M, Hodge C, and Shearer P. Auditory late effects of childhood cancer therapy: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatrics. (2010) 125:e938–950. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1597

86. Stout NL, Silver JK, Raj VS, Rowland J, Gerber L, Cheville A, et al. Toward a national initiative in cancer rehabilitation: recommendations from a subject matter expert group. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2016) 97:2006–15. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.05.002

87. Agulnik A, Muniz-Talavera H, Pham LTD, Chen Y, Carrillo AK, Cárdenas-Aguirre A, et al. Effect of paediatric early warning systems (PEWS) implementation on clinical deterioration event mortality among children with cancer in resource-limited hospitals in Latin America: a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. (2023) 24:978–88. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00285-1

88. Grandinette S. Supporting students with brain tumors in obtaining school intervention services: the clinician’s role from an educator’s perspective. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. (2014) 7:307–21. doi: 10.3233/PRM-140301

89. Qaddoumi I, Mansour A, Musharbash A, Drake J, Swaidan M, Tihan T, et al. Impact of telemedicine on pediatric neuro-oncology in a developing country: the Jordanian-Canadian experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2007) 48:39–43. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21085

Keywords: pediatric neuro-oncology, subspecialization, centralization, LMIC (low and middle income countries), neuro oncology

Citation: Baker A, Bhat K. V, Moreira DC and Qaddoumi I (2025) Sub specialization and centralization of pediatric neuro-oncology services: a strategy to improve outcomes in low-resource settings. Front. Oncol. 15:1618469. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1618469

Received: 26 April 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 28 October 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Terry A. Vik, Indiana University Bloomington, United StatesReviewed by:

Naureen Mushtaq, Aga Khan University, PakistanSidnei Epelman, Hospital Santa Marcelina, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Baker, Bhat K., Moreira and Qaddoumi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ibrahim Qaddoumi, aWJyYWhpbS5xYWRkb3VtaUBzdGp1ZGUub3Jn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Abigail Baker1†

Abigail Baker1† Vasudeva Bhat K.

Vasudeva Bhat K. Daniel C. Moreira

Daniel C. Moreira Ibrahim Qaddoumi

Ibrahim Qaddoumi