- 1Department of Urology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin, Guangxi, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and Microenvironmental Regulation, Guilin Medical University, Guilin, Guangxi, China

- 3Guangxi Health Commission Key Laboratory of Tumor Immunology and Receptor-Targeted Drug Basic Research, Guilin Medical University, Guilin, Guangxi, China

Background: Gene polymorphisms of ESRα Pvull(rs2234693), Xbal(rs9340799), and ESRβ Alul(rs4986938) and RsaI (rs1256049), have been investigated for their associations with prostate cancer risk. However, the nature of these relationships remains ambiguous. Therefore, the present study aimed to further clarify the association between ESR gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer.

Objective: To investigate the association between ESRα Pvull(rs2234693), Xbal(rs9340799), and ESRβ Alul(rs4986938), Rsal(rs1256049) polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk.

Materials and methods: PubMed, Medline, and CNKI were searched. Associations were assessed using odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The false-positive report probability (FPRP), Bayesian false discovery probability (BFDP), and Venetian criteria were used to evaluate the credibility of statistically significant findings.

Results: We found for the first time that, overall, the ESRα PvuII polymorphism was significantly associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer (pp vs. Pp + PP: OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.71–0.97; pp vs. PP: OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57–0.99; p vs. P: OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.78–0.99). A similarly reduced risk was observed in Caucasians (pp + Pp vs. PP: OR = 0.01, 95% CI = 0.01–0.04). By contrast, the ESRα PvuII polymorphism increased prostate cancer risk among Africans (pp + Pp vs. PP: OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.61–3.51). For ESRβ RsaI, we observed a reduced risk of prostate cancer in Asians (r vs. R: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.77–0.98). However, no significant associations were identified for ESRα XbaI or ESRβ AluI. When evaluating credibility using the FPRP, BFDP, and Venetian criteria, no statistically robust associations were confirmed.

Conclusions: Overall, the results suggest a potential association between the ESRα PvuII and ESRβ RsaI polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk, although the credibility assessments did not support statistically robust relationships.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a highly prevalent malignancy among men worldwide, particularly in Western countries, where it remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality and a major public health concern (1). Although the incidence of PCa in Asian populations has historically been lower than in Western nations, epidemiological trends indicate a steady rise in cases, attributed to factors such as socioeconomic development, demographic aging, adoption of Westernized dietary habits, and lifestyle changes (2). Despite advances in early detection and therapeutic interventions, the precise etiology and molecular mechanisms underlying PCa pathogenesis remain incompletely understood. Current evidence suggests that both genetic susceptibility and environmental influences contribute to PCa development, with gene polymorphisms serving as an important biological determinant of inherited risk (3).

Estrogen receptors (ESRs) are nuclear macromolecules that mediate the biological effects of estrogen (4). Two isoforms exist—ESRα and ESRβ—which differ in the C-terminal ligand-binding region and the N-terminal activation domain (5). The ESRα gene consists of eight exons spanning approximately 140 kb on chromosome 6q25.1, whereas the ESRβ gene consists of eight exons spanning approximately 40 kb on chromosome 14q23–24.1 (6). Studies have shown that ESRα may act as an oncogenic factor that promotes tumor cell proliferation, while ESRβ is considered protective, exhibiting anti-cancer and pro-apoptotic effects. Genetic polymorphisms in the ESRα and ESRβ genes may lead to altered transcription or affect transcript stability (7). Therefore, polymorphisms in ESRα and ESRβ may represent potential risk factors for prostate cancer.

To date, numerous studies have examined the associations between ESRα and ESRβ gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk (8–15, 18–41). However, the evidence remains inconsistent, with some reports identifying significant associations while others report null findings. Eight meta-analyses have evaluated these associations, yet their conclusions remain conflicting (8–15). In addition, no previous meta-analysis performed a credibility assessment of statistically significant findings. Therefore, the present study further investigated the association between ESRα and ESRβ gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk.

Materials and methods

PRISMA guidelines were followed in this meta-analysis (42).

Search strategy

Articles were retrieved from PubMed, Medline, and CNKI. The search strategy was as follows: (“estrogen receptors” OR “ESR” OR “estrogen receptor alpha” OR “estrogen receptor beta” OR “ER alpha” OR “ER beta” OR “estrogen receptor 1” OR “estrogen receptor 2” OR “ESR1” OR “ESR2”) AND (“polymorphism” OR “gene” OR “SNP”) AND (“prostate cancer” OR “PCa). Searches were conducted up until September 15, 2024. In addition, reference lists of previously published meta-analyses were carefully reviewed to identify all eligible studies (8–15).

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) case–control studies; (ii) studies that assessed associations between ESRα PvuII and XbaI, and ESRβ AluI and RsaI polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk; (iii) prostate cancer cases confirmed by histopathology. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) cross-sectional studies; (ii) case reports, reviews, letters, and meta-analyses; (iii) animal studies.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The literature was screened by two independent reviewers, with disagreements resolved through discussion or by consultation with a third researcher. Extracted data included the first author, publication year, country, ethnicity, sample sizes of cases and controls, and genotype frequencies (Supplementary Tables 2–5). Study quality was independently evaluated by two authors using criteria reported in previous studies (16, 17), as presented in Supplementary Table 1. The quality assessment was based on a 15-point scale, and a score greater than 8 indicated a high-quality study.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.0. Five genetic models were evaluated (dominant, recessive, additive, over-dominant, and allele models). Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control group was assessed using the chi-square test (P < 0.05 was considered indicative of Hardy–Weinberg disequilibrium [HWD]) (43).

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Q test and the I² statistic. Significant heterogeneity was defined as P < 0.10 and/or I² > 50% (44), in which case pooled ORs were calculated using a random-effects model; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied. Potential sources of heterogeneity were explored using meta-regression analysis (45). Subgroup analyses were conducted by ethnicity and by source of the control group. Sensitivity analyses were performed by including only studies of high quality and studies in HWE.

Egger’s test (46) and Begg’s test (47) were used to evaluate publication bias. The false-positive report probability (FPRP) (48), Bayesian false discovery probability (BFDP) (49), and Venetian criteria (50) were used to assess the credibility of statistically significant associations (I2 < 50%; FPRP < 0.2 and BFDP <0.8).

Results

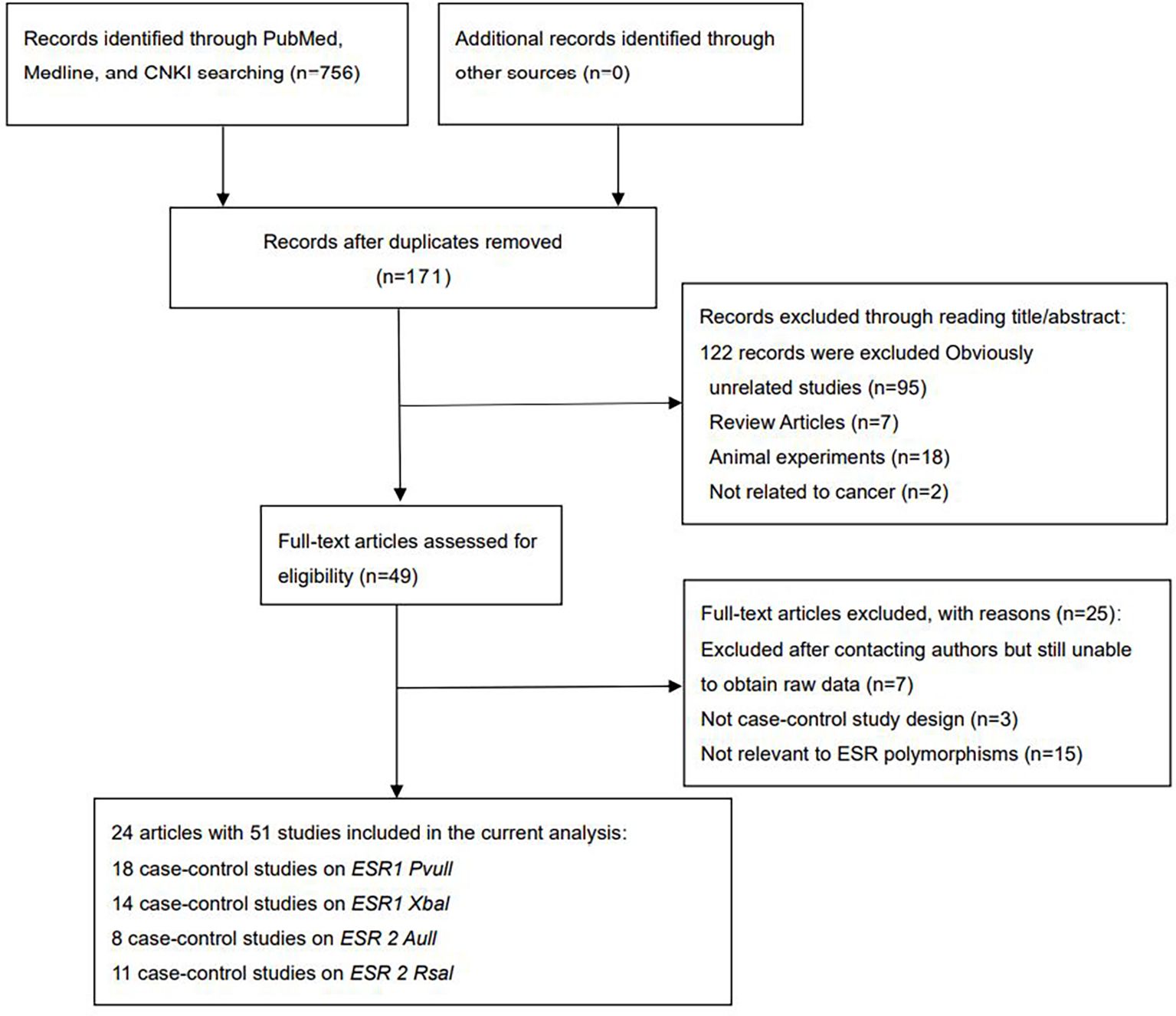

Overall, 756 articles were retrieved (Figure 1). After screening titles and full texts, 24 articles comprising 51 studies were included (Supplementary Tables 2–5, Figure 1). A total of 26,454 cases and 33,941 controls were analyzed. As shown in Supplementary Tables 2–5, ESRα Pvull was reported in 18 studies (4,623 cases and 9,850 controls), ESRα Xbal in 14 studies (3,716 cases and 4,536 controls), ESRβ Alul in eight studies (8,674 cases and 9,498 controls), and ESRβ Rsal in 11 studies (9,390 cases and 10,057 controls). As detailed in Supplementary Table 6, the number of high-quality articles for each polymorphism was as follows: ESRα Pvull (n=10; with 8 low-quality), ESRα Xbal (n=5; with 9 low-quality), ESRβ Alul (n=3; with 5 low-quality), and ESRβ Rsal (n=7; with 4 low-quality).

Quantitative synthesis

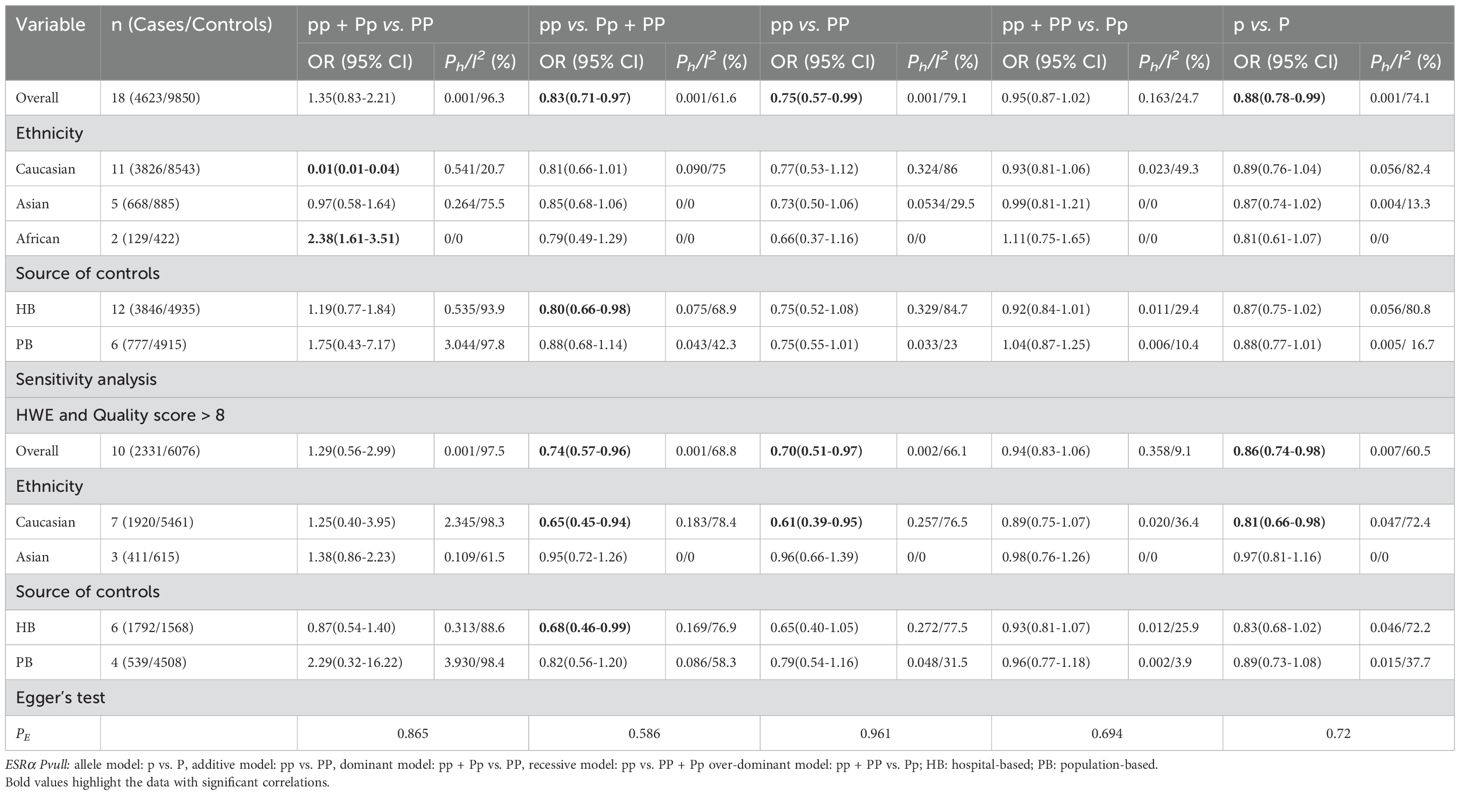

ESRα Pvull polymorphism

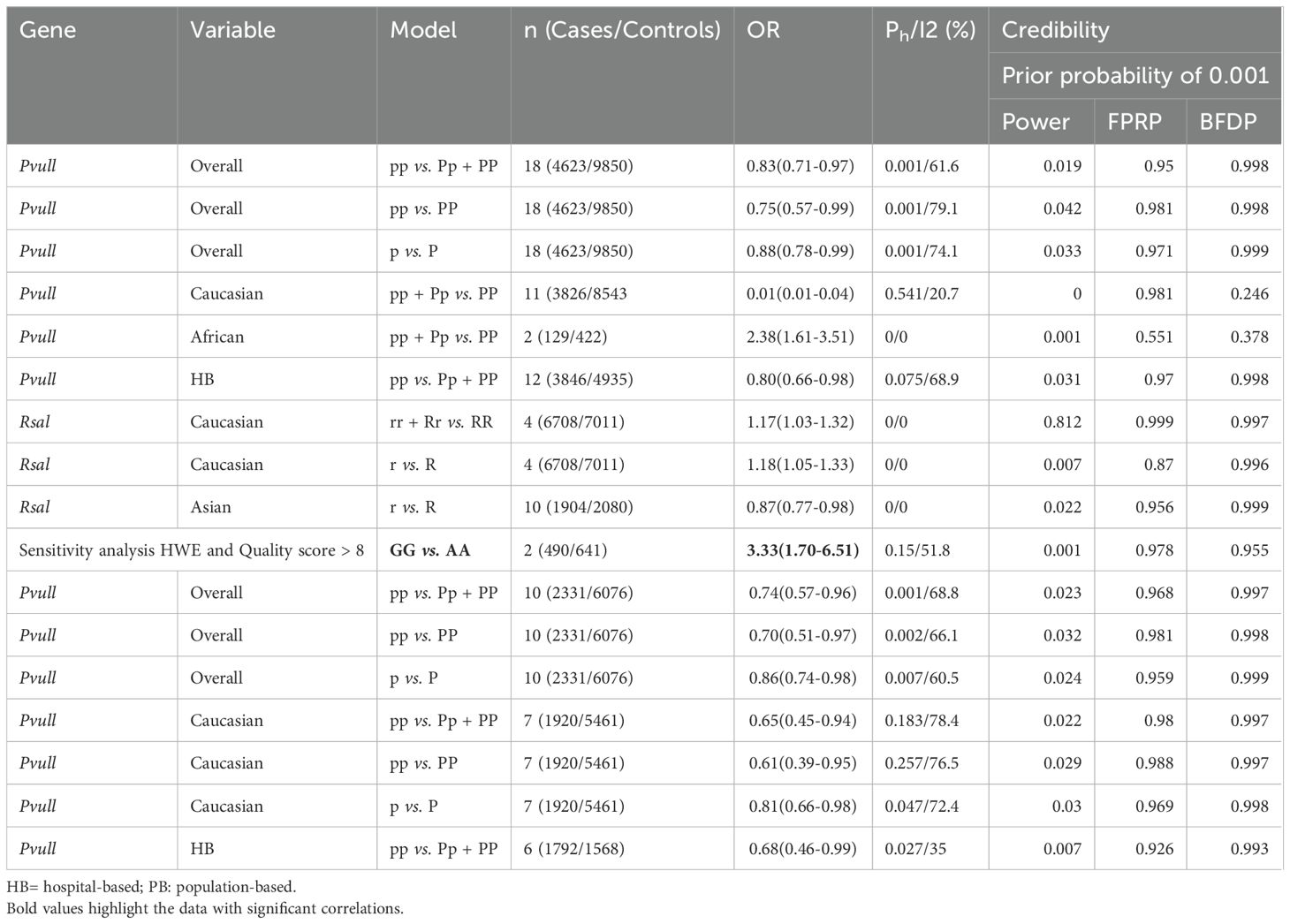

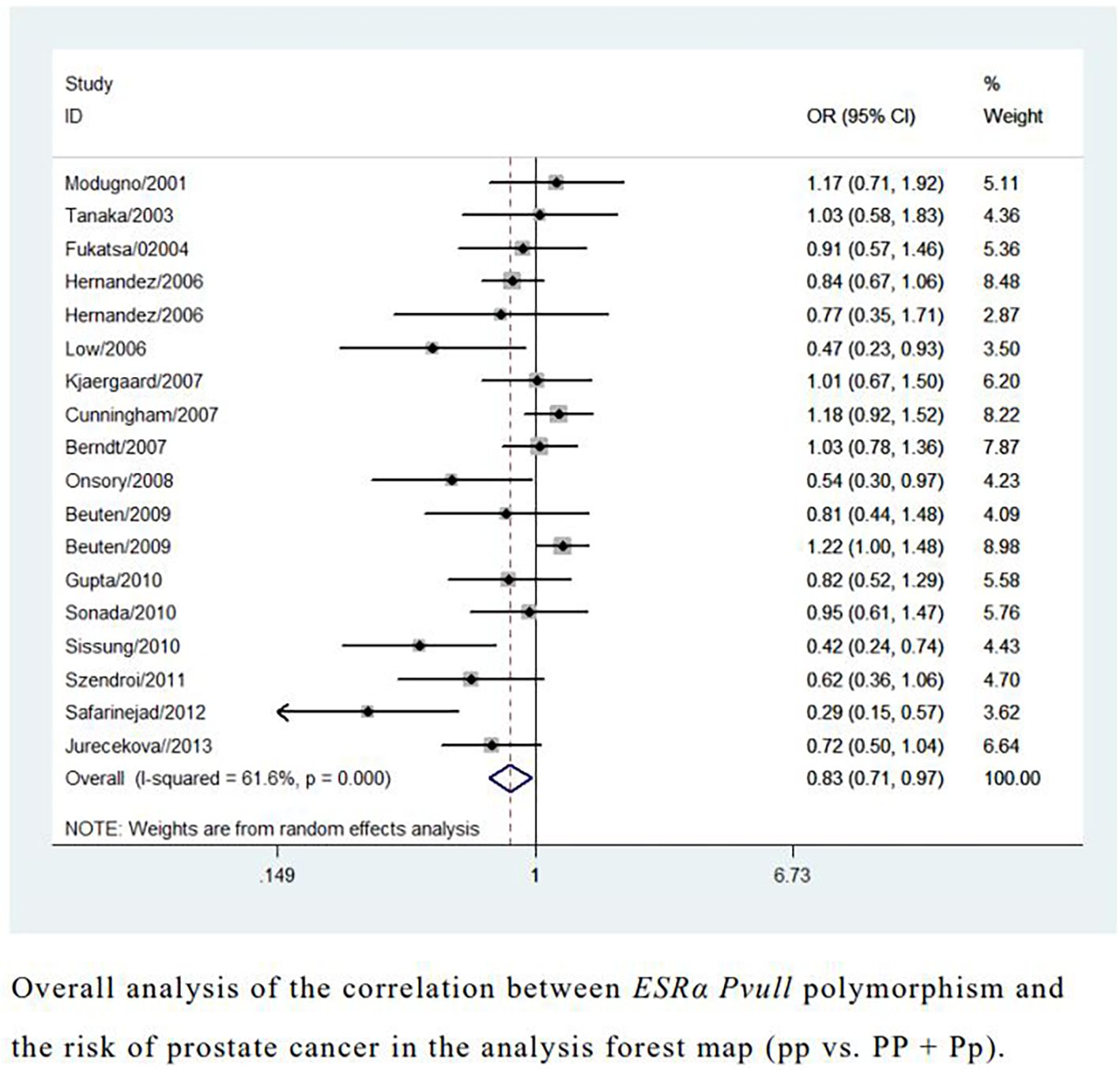

Overall analyses showed that the ESRα PvuII polymorphism was associated with a reduced risk of prostate cancer (pp vs. Pp + PP: OR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.71–0.97; pp vs. PP: OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57–0.99; p vs. P: OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.78–0.99; Table 1 and Figure 2). A similarly reduced risk was observed in Caucasians (pp + Pp vs. PP: OR = 0.01, 95% CI = 0.01–0.04). However, the ESRα PvuII polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer in Africans (pp + Pp vs. PP: OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 1.61–3.51; Table 1). A reduced risk was also observed in hospital-based controls (pp vs. Pp + PP: OR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.66–0.98; Table 1). Sensitivity analyses further confirmed the robustness of these findings.

Table 1. Meta-analysis of the association of ESRα Pvull polymorphism with risk of prostate cancer risk.

Figure 2. Overall analysis of the correlation between ESRα Pvull polymorphism and the risk of prostate cancer in the analysis forest map.

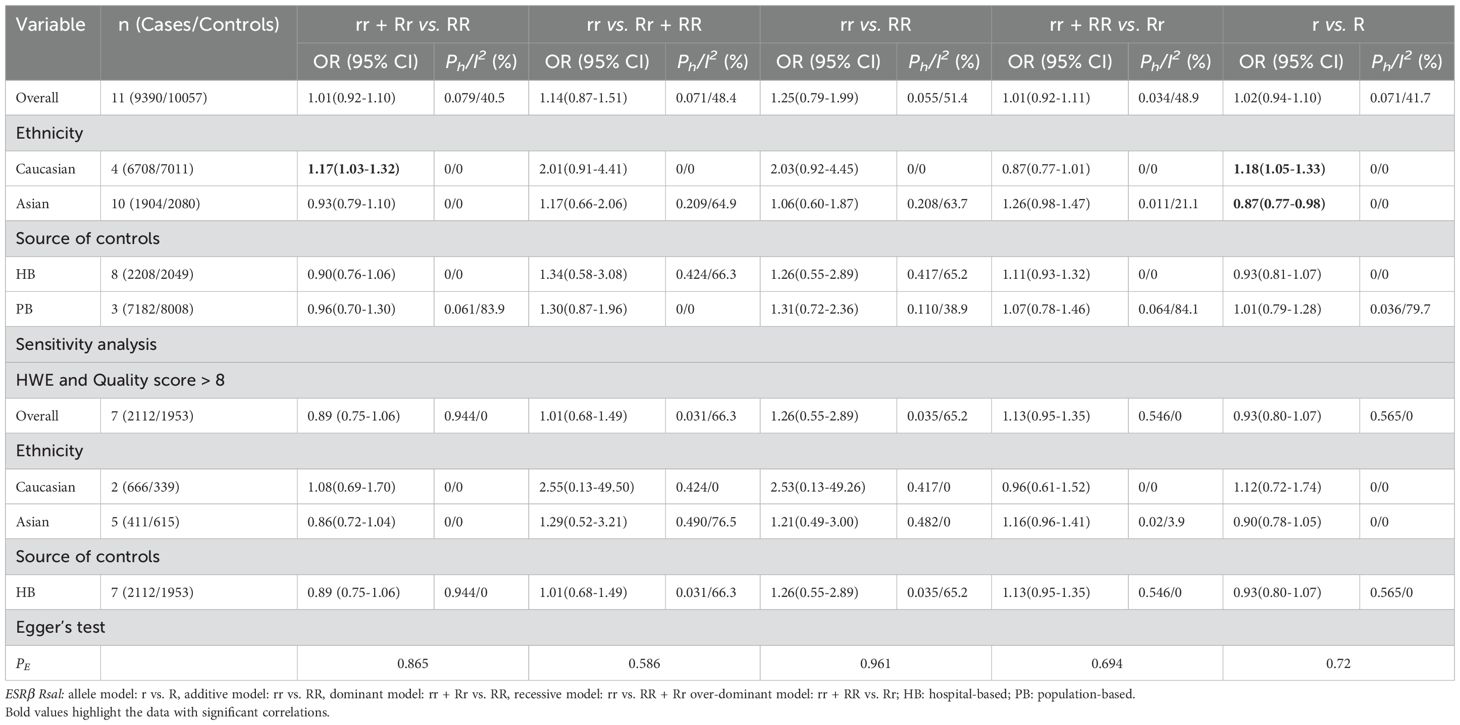

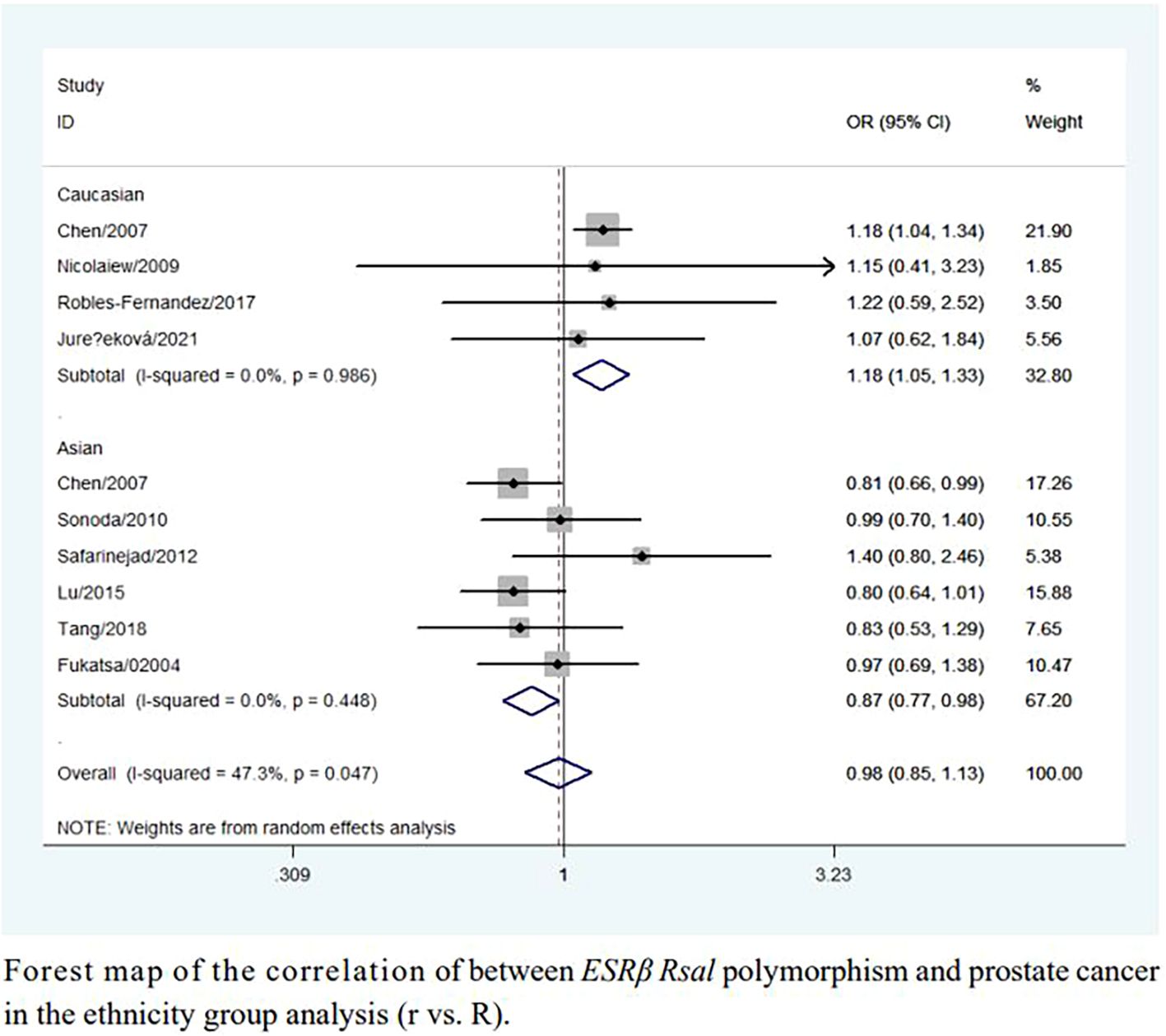

ESRβ Rsal polymorphism

An increased risk of prostate cancer was found in Caucasians (rr + Rr vs. RR: OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.03–1.32; r vs. R: OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.05–1.33; Table 2, Figure 3). In contrast, a reduced risk was observed in Asians (r vs. R: OR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.77–0.98; Table 2, Figure 3). However, sensitivity analyses did not confirm these associations (Table 2).

Table 2. Meta-analysis of the association of ESRβ Rsal polymorphism with risk of prostate cancer risk.

Figure 3. Forest map of the correlation of between ESRβ Rsal polymorphism and prostate cancer in the ethnicity group analysis (r vs. R).

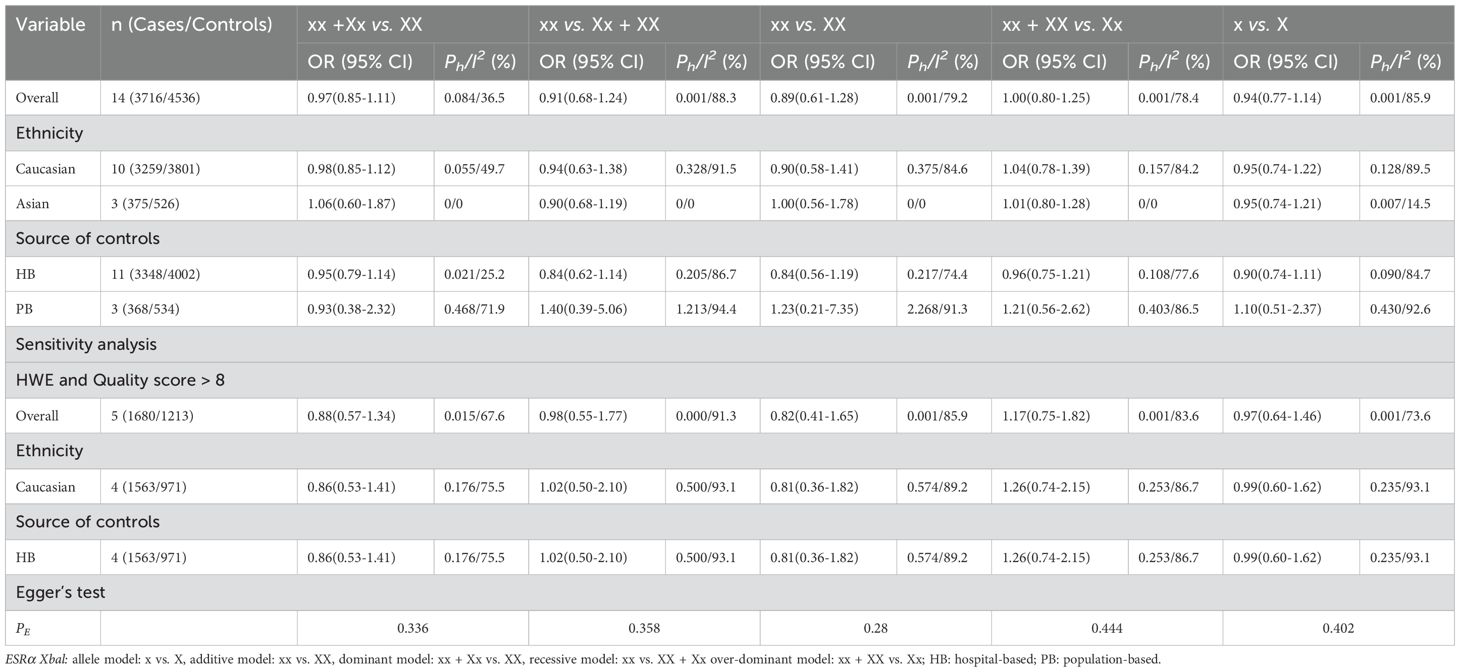

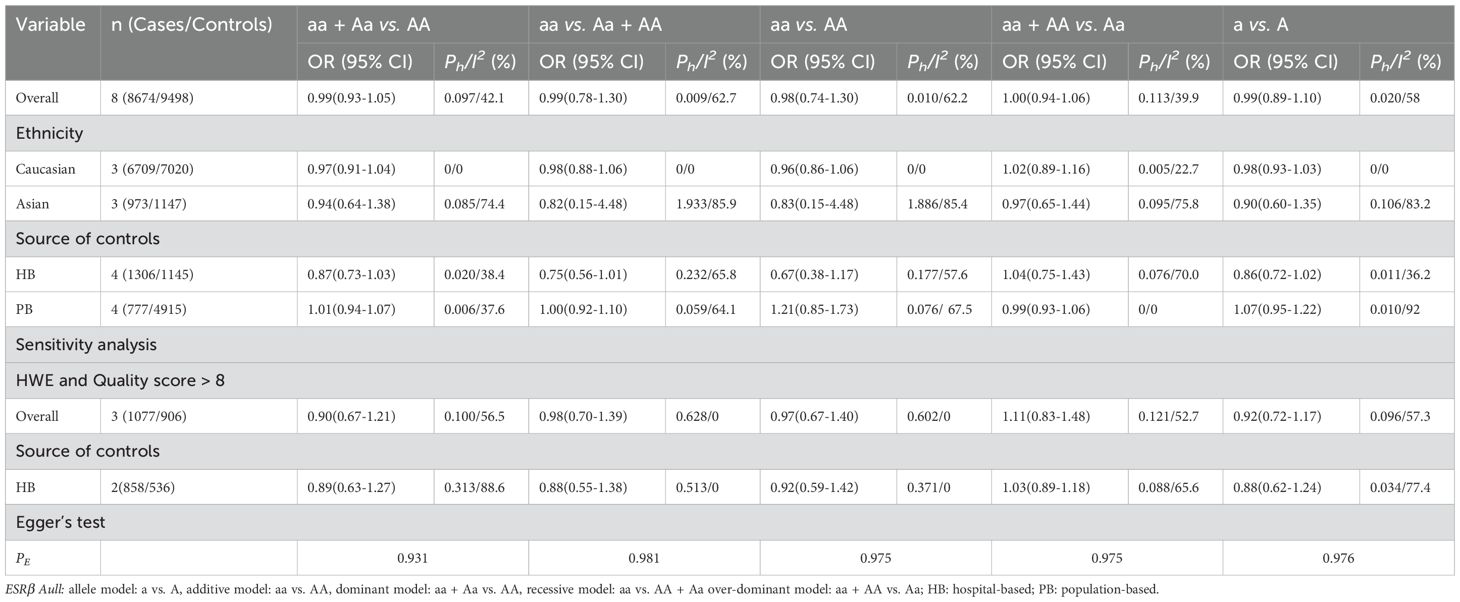

ESRα Xbal and ESRβ Alul polymorphism

The overall and subgroup analyses showed no association between ESRα XbaI or ESRβ AluI polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk. Sensitivity analyses showed no significant changes in these results (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3. Meta-analysis of the association of ESRα Xbal polymorphism with risk of prostate cancer risk.

Table 4. Meta-analysis of the association of ESRβ Aull polymorphism with risk of prostate cancer risk.

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

During the statistical process, we identified several possible sources of heterogeneity were examined, including ethnicity, sample size, country, source of study population, quality score, and HWE status. Meta-regression analyses were performed, but no clear source of heterogeneity was identified. Two approaches were used for sensitivity analyses: (i) sequential removal of each study, and (ii) restricting the analysis to studies with both high quality and HWE compliance. Both approaches showed that the associations between ESRα and ESRβ polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk remained unchanged (Tables 1, 2).

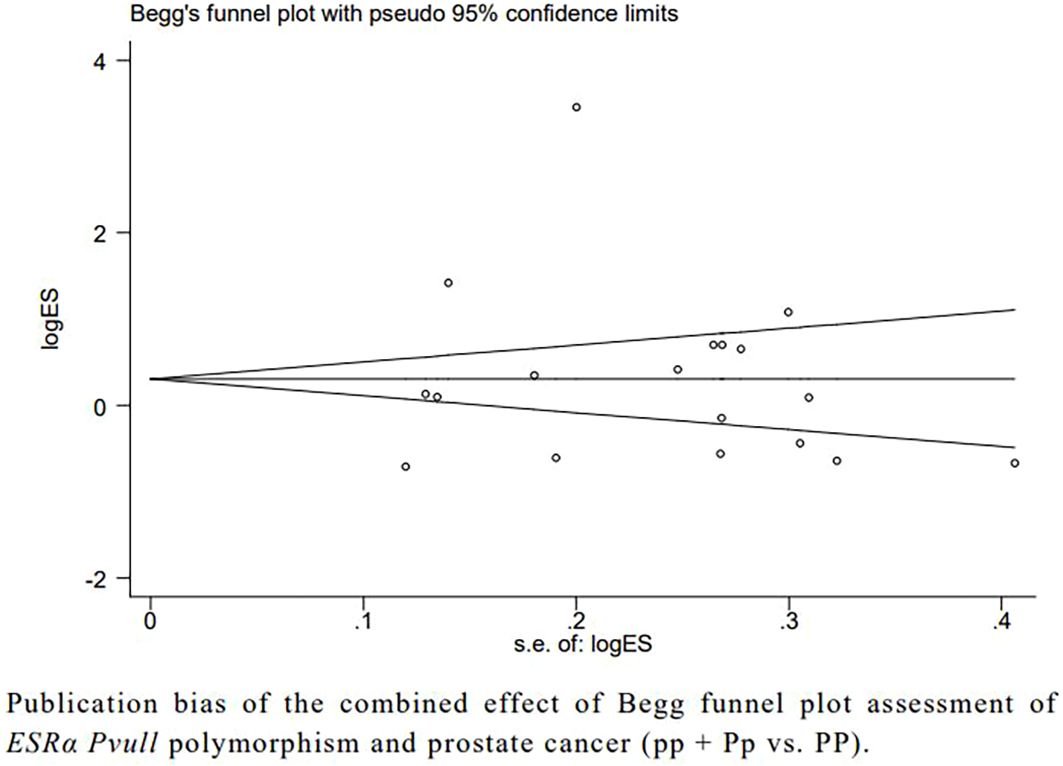

Publication bias

Begg’s and Egger’s tests showed no publication bias between ESRα Pvull, ESRα Xbal, ESRβ Alul, and ESRβ Rsal polymorphisms and prostate cancer (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Publication bias of the combined effect of Begg funnel plot assessment of ESRα Pvull polymorphism anf prostate cancer (pp + Pp vs. PP).

Credibility analysis

The credibility of this meta-analysis was assessed using the FPRP, BFDP, and Venice criteria. In this study, we observed a reduction in the strength of all statistically significant associations (Table 5).

Discussion

Interestingly, the effect of ESR on the risk of prostate cancer differed significantly across ethnic groups. We found that ESRβ Rsal was associated with a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer in Caucasians. However, ESRβ Rsal appears to be a protective gene against prostate cancer in Asians. Meanwhile, Pvull may also be a risk gene locus for prostate cancer in Africans. However, ESRα Pvull gene polymorphism showed a significantly reduced association with prostate cancer risk in the general population. However, no significant results were found in the final sensitivity analyses. Although we attempted to include all relevant studies, the inclusion of low-quality studies may have affected the true associations. Unfortunately, we did not find an association between ESRα Xbal and ESRβ Alul and the risk of prostate cancer.

We used subgroups of race and mode of recruitment, as well as five genetic models, which necessarily led to multiple comparisons; therefore, adjustment for pooled p-values was necessary. The confidence of the associations between ESRα Pvull, Xbal, and ESRβ Alul, Rsal polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk was low according to the FPRP, BFDP, and Venice criteria. This seemingly contradictory outcome primarily stems from the following aspects. First, the calculation of FPRP and BFDP depends not only on the P-value but, more critically, on statistical power and the pre-specified prior probability. In this study, the statistical power for this specific variant was at a moderate level, which increases the relative risk of the result being a false positive. Second, adhering to a principle of caution, we employed a relatively conservative prior probability (0.001) in our calculations. This reflects a more prudent stance toward this finding, given the current lack of strong biological or genetic evidence. Therefore, the “low confidence” rating does not negate the association but emphasizes that our findings should be considered preliminary and suggestive evidence, whose ultimate confirmation will require replication in larger, independent cohorts or prospective studies. Future research should aim to validate the association observed here in samples with sufficient statistical power, complemented by functional experimental evidence.

Based on subgroup analyses by population, the results across different ethnic subgroups revealed contradictory patterns. Our findings underscore that the effects of genetic variants may be highly population-specific. The underlying factors for these discrepancies may include differences in allele frequencies, variations in linkage disequilibrium patterns across populations, and gene–environment interactions. Extreme caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to populations with different genetic backgrounds. Future studies should focus on more refined genetic analyses within individual populations and integrate environmental exposure data to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying these discordant associations.

Previously, eight interlinked meta-analyses had published results on the association between the ESRα Pvull, Xbal, and ESRβ Alul, Rsal genetic polymorphisms and the risk of prostate cancer. Chang et al, Fu et al, Ma et al, and Liu found that ESRβ Rsal might be correlated with an increased risk of PCa in Caucasians, while less susceptibility was observed in Asians (8, 9, 13, 14). Wang et al. and Li et al. found that the PvuII polymorphism was significantly associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer among Asian populations (11, 15). Gazzaz et al. demonstrated that ESRα Rsal increases the risk of prostate cancer. Gu et al. suggested that ESRα Xbal is a noteworthy gene for prostate cancer risk in Africans (12). Unfortunately, we did not replicate the findings of Gu et al. after including additional data from our study. The conflicting results, particularly in Asian populations, may be due to the insufficient number of included studies. These studies examined only the association between a single SNP and prostate cancer risk. Furthermore, several studies did not conduct a quality assessment of eligible articles. In addition, none evaluated the credibility of statistically significant associations. Compared with previous studies, our study is the first to reveal a significant association between the ESRα Pvull polymorphism and a reduced risk of prostate cancer. By including a larger number of studies, we further clarified the relationship between ESRα, ESRβ, and prostate cancer risk.

In order to further clarify the uncertain results of previous meta-analyses and evaluate current findings, we conducted this meta-analysis. The present study has the following advantages over previous analyses: (i) strict inclusion criteria; (ii) HWE examination of control groups; (iii) assessment of the credibility of statistically significant associations; (iv) inclusion of more studies with larger sample sizes; and (v) more accurate subgroup analyses and more professional modeling approaches. The shortcomings of previous studies were noted and addressed. However, our study has several limitations. First, we included only published articles that could be retrieved through database searches. Second, the included studies did not adjust for confounding factors that may significantly affect the results; therefore, our findings are based on unadjusted OR estimates. Third, although the overall sample size was large, the quality of the included studies varied, which may reduce confidence in the final results. Therefore, additional studies are needed in the future to further verify our findings.

The pathogenesis of prostate cancer involves complex interactions between environmental factors and polygenic influences. While our investigation specifically examined the impact of ESR single-nucleotide polymorphisms on prostate cancer risk, this systematic analysis incorporated the majority of currently available studies on the ESR–prostate cancer association. Our findings further elucidate the relationship between ESR and prostate cancer and provide a meaningful perspective for future prostate cancer research and the identification of potential therapeutic targets.

Conclusion

In summary, ESRα Pvull and ESRβ Rsal polymorphisms are associated with the risk of prostate cancer. However, the observed effects were inconsistent or weak across studies. To resolve this uncertainty and confirm any potential link, large studies with sufficient methodological quality are needed in the future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

XB: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Software, Investigation. LG: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Conceptualization. JZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. WL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YC: Writing – original draft, Data curation. XG: Writing – original draft, Data curation. JJ: Writing – review & editing. BG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (grant no. [2023GXNSFAA026061]; [Li Gao]), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. [32360170], [Li Gao]; [82460158].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1630363/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

BFDP, Bayesian false discovery probability; CI, confidence interval; FPRP, false-positive report probabilities; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; OR, odds ratio; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses; ESR, estrogen receptor.

References

1. Bergengren O, Pekala KR, Matsoukas K, Fainberg J, Mungovan SF, Bratt O, et al. 2022 update on prostate cancer epidemiology and risk factors-A systematic review. Eur Urol. (2023) 84:191–206. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.021

2. Ju W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Sun K, Wang S, et al. Cancer statistics in Chinese older people, 2022: current burden, time trends, and comparisons with the US, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Sci China Life Sci. (2023) 66:1079–91. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2218-x

3. Baca SC, Singler C, Zacharia S, Seo JH, Morova T, Hach F, et al. Genetic determinants of chromatin reveal prostate cancer risk mediated by context-dependent gene regulation. Nat Genet. (2022) 54:1364–75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01168-y

4. Hassan NE, El Shebini SM, El-Masry SA, Ahmed NH, Eldeen GN, Rasheed EA, et al. Association of some dietary ingredients, vitamin D, estrogen, and obesity polymorphic receptor genes with bone mineral density in a sample of obese Egyptian women. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. (2021) 19:28. doi: 10.1186/s43141-021-00127-0

5. Lambert MNT, Hu LM, and Jeppesen PB. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of isoflavone formulations against estrogen-deficient bone resorption in peri- and postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. (2017) 106:801–11. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.151464

6. Kos M, Reid G, Denger S, and Gannon F. Minireview: genomic organization of the human ERalpha gene promoter region. Mol Endocrinol. (2001) 15:2057–63. doi: 10.1210/me.15.12.2057

7. Maguire P, Margolin S, Skoglund J, Sun XF, Gustafsson JA, Borresen-Dale AL, et al. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) polymorphisms in familial and sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2005) 94:145–52. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-7697-7

8. Chang X, Wang H, Yang Z, Wang Y, Li J, and Han Z. ESR2 polymorphisms on prostate cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (Baltimore). (2023) 102:e33937. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000033937

9. Fu C, Dong WQ, Wang A, and Qiu G. The influence of ESR1 rs9340799 and ESR2 rs1256049 polymorphisms on prostate cancer risk. Tumour Biol. (2014) 35:8319–28. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2086-7

10. Gazzaz H, El Feniche M, Ameur A, and Dami A. Association between the Estrogen receptor β rs1256049 polymorphism and prostate cancer risk:a meta-analysis. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). (2023) 81:280–8. doi: 10.1684/abc.2023.1815

11. Wang YM, Liu ZW, Guo JB, Wang XF, Zhao XX, and Zheng X. ESR1 gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk: A huGE review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2013) 8:e66999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066999

12. Gu Z, Wang G, and Chen W. Estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis involving 18 studies. Tumour Biol. (2014) 35:5921–30. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1785-4

13. Liu P. A meta-analysis of estrogen receptor β gene rs1256049 polymorphism and prostate cancer susceptibility. No. 382, Wuyi Road, Xinghualing District, Taiyuan City, Shanxi Province: Shanxi Medical University (2019).

14. Ma Y-d, Wang A-N, and Zhong S-p. Relationship between estrogen receptor α gene rs2234693 polymorphism and risk of prostate cancer. Chin J Physiol. (2015) 1):104–8.

15. Li L, Zhang X, Xia Q, Ma H, Chen L, and Hou W. Association between estrogen receptor alpha PvuII polymorphism and prostate cancer risk. Tumour Biol. (2014) 35:4629–35. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1606-9

16. Wang D, Liu L, Zhang C, Lu W, Wu F, and He X. Evaluation of association studies and meta-analyses of eNOS polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes mellitus risk. Front Genet. (2022) 13:887415. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.887415

17. Mu YY, Liu B, Chen B, Zhu WF, Ye XH, Li HZ, et al. Evaluation of association studies and an updated meta-analysis of VDR polymorphisms in osteoporotic fracture risk. Front Genet. (2022) 12:791368. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.791368

18. Modugno F, Weissfeld JL, Trump DL, Zmuda JM, Shea P, Cauley JA, et al. Allelic variants of aromatase and the androgen and estrogen receptors:toward a multigenic model of prostate cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. (2001) 7:3092–6.

19. Tanaka Y, Sasaki M, Kaneuchi M, Shiina H, Igawa M, and Dahiya R. Polymorphisms estrogen receptor alpha in prostate cancer. Mol Carcinog. (2003) 37:202–8. doi: 10.1002/mc.10138

20. Fukatsu T, Hirokawa Y, Araki T, Hioki T, Murata T, Suzuki H, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of hormone-related genes and prostate cancer risk in the Japanese population. Anticancer Res. (2004) 24:2431–7.

21. Hernandez J, Balic I, Johnson-Pais TL, Higgins BA, Torkko KC, Thompson IM, et al. Association between an estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphism and the risk of prostate cancer in black men. J Urol. (2006) 175:523–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00240-5

22. Low YL, Taylor JI, Grace PB, Mulligan AA, Welch AA, Scollen S, et al. Phytoestrogen exposure, polymorphisms in COMT, CYP19, ESR1, and SHBG genes, and their associations with prostate cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. (2006) 56:31–9. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5601_5

23. Kjaergaard AD, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Axelsson CK, Grønholdt ML, Grande P, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha polymorphism and risk of cardio -vascular disease, cancer, and hip fracture: cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies and a meta-analysis. Circulation. (2007) 115:861–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615567

24. Cunningham JM, Hebbring SJ, McDonnell SK, Cicek MS, Christensen GB, Wang L, et al. Evaluation of genetic variations in the androgen and estro -gen metabolic pathways as risk factors for sporadic and fa -milial prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2007) 16:969–78. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0767

25. Berndt SI, Chatterjee N, Huang WY, Chanock SJ, Welch R, Crawford ED, et al. Variant in sex hormone-binding globulin gene and the risk of prostate. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2007) 16:165–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0689

26. Onsory K, Sobti RC, Al-Badran AI, Watanabe M, Shiraishi T, Krishan A, et al. Hormone receptor-related gene polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk in the Northern Indian population. Mol Cell Biochem. (2008) 314:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9761-1

27. Beuten J, Gelfond JA, Franke JL, Weldon KS, Crandall AC, Johnson-Pais TL, et al. Single and multigenic analysis of the association between variants in 12 steroid hormone metabolism genes and risk of prostate. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2009) 18:1869–80. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0076

28. Gupta L, Thakur H, Sobti RC, Seth A, and Singh SK. Role of genetic po syndrome lymorphism of estrogen receptor-alpha gene and risk of estrogen receptor alpha prostate cancer in north Indian population. Mol Cell Biochem. (2010) 335:255–61. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0275-2

29. Sonoda T, Suzuki H, Mori M, Tsukamoto T, Yokomizo A, Naito S, et al. Polymorphisms in estrogen related genes may modify the protective effect isoflavones against prostate cancer risk in Japanese men. Eur J Cancer Prev. (2010) 19:131–7. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328333fbe2

30. Sissung TM, Danesi R, Kirkland CT, Baum CE, Ockers SB, Stein EV, et al. Estrogen receptor αand aromatase polymorphisms affect risk, prognosis, and therapeutic outcome in men with castration-resist ant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel-based therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:E368–72. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2070

31. Szendroi A, Speer G, Tabak A, Kosa JP, Nyirady P, Majoros A, et al. The role of vitamin D, estrogen, calcium sensing receptor genotypes andserum calcium in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. Can J Urol. (2011) 18:5710–6.

32. Safarinejad MR, Safarinejad S, Shafiei N, and Safarinejad S. Estrogen receptors alpha (rs2234693 and rs9340799), and beta (rs4986938 and rs1256049) gene polymorphism in prostate cancer: evidence for association with risk and his -Pathological characteristics of tumor in Iranian men. Mol Carcinog. (2012) 51:E104–17. doi: 10.1002/mc.21870

33. Jurečeková J, Sivoňová MK, Evinová A, Kliment J, and Dobrota D. The association between estrogen receptor alpha polymorphisms and the risk of prostate cancer in Slovak population. Mol Cell Biochem. (2013) 381:201–7. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1703-x

34. Suzuki K, Nakazato H, Matsui H, Koike H, Okugi H, Kashiwagi B, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of estrogen receptor alpha, CYP19, catechol-O-methyltransferase are associated with familial prostate carcinoma risk in a Japanese population. Cancer. (2003) 98:411–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11639

35. Balistreri CR, Caruso C, Carruba G, Miceli V, and Candore G. Genotyping of sex hormone-related pathways in benign and Malignant human prostate tissues: data of a preliminary study. OMICS. (2011) 5:369–74. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0128

36. Chae YK, Huang HY, Strickland P, Hoffman SC, and Helzlsouer K. Genetic polymorphisms of estrogen receptors alpha and beta and the risk of developing prostate cancer. PloS One. (2009) 4:6523. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006523

37. Lu X, Yamano Y, Takahashi H, Koda M, Fujiwara Y, Hisada A, et al. Associations between estrogen receptor genetic polymorphisms, smoking status, and prostate cancer risk: a case-control study in Japanese men. Environ Health Prevent Med. (2015) 20:32–7. doi: 10.1007/s12199-015-0471-5

38. Chen YC, Kraft P, Bretsky P, Ketkar S, Hunter DJ, Albanes D, et al. Sequence variants of estrogen receptor beta and risk of prostate cancer in the National Cancer Institute Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevent. (2007) 6:1973–81. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0431

39. Nicolaiew N, Cancel-Tassin G, Azzouzi AR, Grand BL, Mangin P, Cormier L, et al. Association between estrogen and androgen receptor genes and prostate cancer risk. Eur J Endocrinol. (2009) 160:01–6. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0321

40. Robles-Fernandez I, Martinez-Gonzalez LJ, Pascual-Geler M, Cozar JM, Puche-Sanz I, Serrano MJ, et al. Association between polymorphisms in sex hormones synthesis and metabolism and prostate cancer aggressiveness. PloS One. (2017) 12:01 85447e0185447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185447

41. Tang L, Platek ME, Yao S, Till C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Associations between polymorphisms in genes related to estrogen metabolism and function and prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Carcinogenesis. (2018) 9:125–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx144

42. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, and PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

43. Thakkinstian A, McKay GJ, McEvoy M, Chakravarthy U, Chakrabarti S, Silvestri G, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between complement component 3 and age-related macular degeneration: a HuGE review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. (2011) 173:1365–79. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr025

44. Mantel N and Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. (1959) 22:719–48.

45. DerSimonian R and Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. (2015) 45:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002

46. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, and Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

47. Begg CB and Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446

48. Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El Ghormli L, and Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2004) 96:434–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075

49. Wakefield J. A Bayesian measure of the probability of false discovery in genetic epidemiology studies. Am J Hum Genet. (2007) 81:208–27. doi: 10.1086/519024

Keywords: ESR, polymorphism, prostate cancer, meta-analysis, FPRP, BFDP

Citation: Bai X, Gao L, Zhao J, Liao W, Chen Y, Guo X, Jin J and Ge B (2025) Association between ESRα and ESRβ polymorphisms and prostate cancer risk: meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 15:1630363. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1630363

Received: 17 May 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 10 October 2025;

Published: 08 December 2025.

Edited by:

Behzad Toosi, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaReviewed by:

Shalom Nwodo Chinedu, Covenant University, NigeriaNihal Inandiklioğlu, Bozok University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Bai, Gao, Zhao, Liao, Chen, Guo, Jin and Ge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Ge, Z2UxMTIzQHNpbmEuY29t; Jiamin Jin, MjgyNjY1OTA2NUBxcS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Xiaohui Bai

Xiaohui Bai Li Gao1,2†

Li Gao1,2† Jiawei Zhao

Jiawei Zhao Yujing Chen

Yujing Chen Bo Ge

Bo Ge