- 1Department of Urology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 2Department of Nursing, The Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 3Department of Pathology, The Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 4Department of Urology, The Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor (JGCT) is an extremely rare neoplasm of the kidney that poses a significant clinical challenge in terms of accurate diagnosis. The key to successful treatment lies in the accurate identification of renal lesion. Excessive secretion of renin by JGCT causes activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) secondary to uncontrollable hypertension, hypokalemia and consequently a range of clinical manifestations. While most JGCTs are benign, there have been reports of malignant cases, thus requiring close follow-up. In this case report, the subject is a middle-aged female patient who has suffered from recurrent poorly controlled blood pressure for a number of years. Following a medical examination, the patient was found to have the right renal mass, which was pathologically confirmed to be JGCT after laparoscopic partial right nephrectomy. Thereafter, the patient’s blood pressure recovered steadily during the subsequent follow-up period. Furthermore, a comprehensive summary of the diagnosis, differential diagnosis, treatment and review of case reports of JGCT from the last decade is provided, encompassing malignant biological behaviors.

Introduction

Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor (JGCT) is an extremely rare renal tumor first described by Robertson et al. in 1967 (1) and formally named by Kihara et al. in 1968 (2), which has led to the disease being referred to as Robertson-Kihara syndrome. The tumor originates from the juxtaglomerular apparatus and is an endocrinologically active neoplasm. The neoplastic cells secrete excessive amounts of renin, which further activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in a secondary manner. The condition is classified as either typical or atypical. The most typical clinical symptoms are uncontrollable hypertension and hypokalemia, which lead to a series of concomitant manifestations, such as headache, weakness, blurred vision, nausea and vomiting. It is evident that these present their own unique clinical and pathological characteristics. In this paper, we present a case of atypical JGCT, with a clinical presentation dominated by poorly controlled recurrent hypertension. We also perform a review of the relevant published literature.

Case report

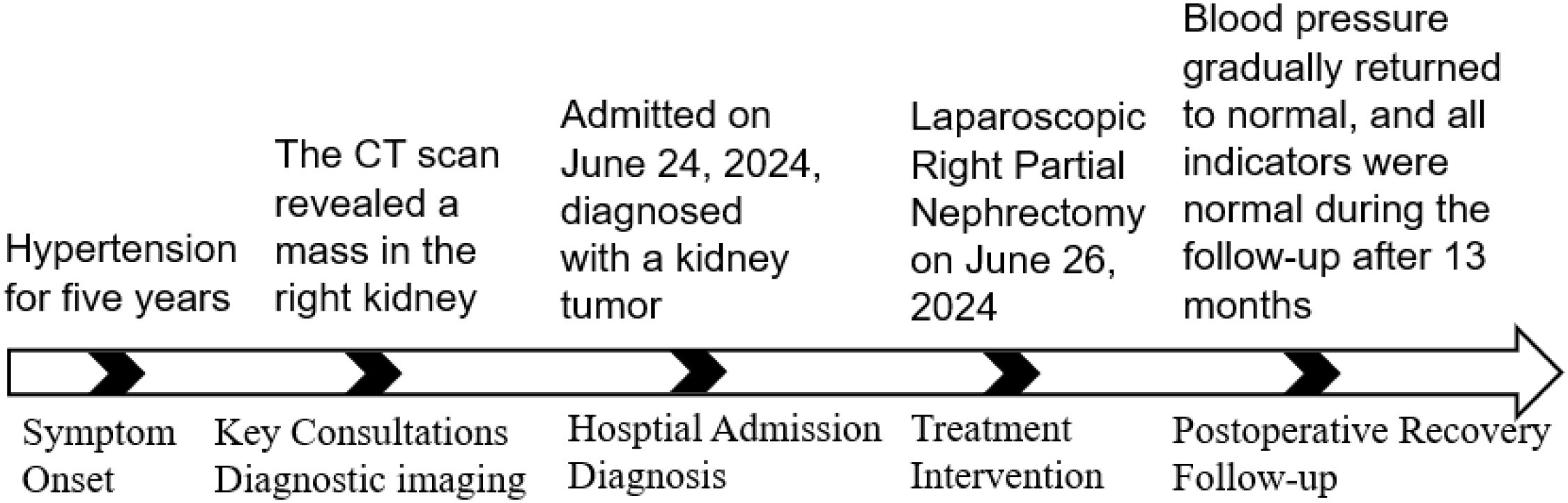

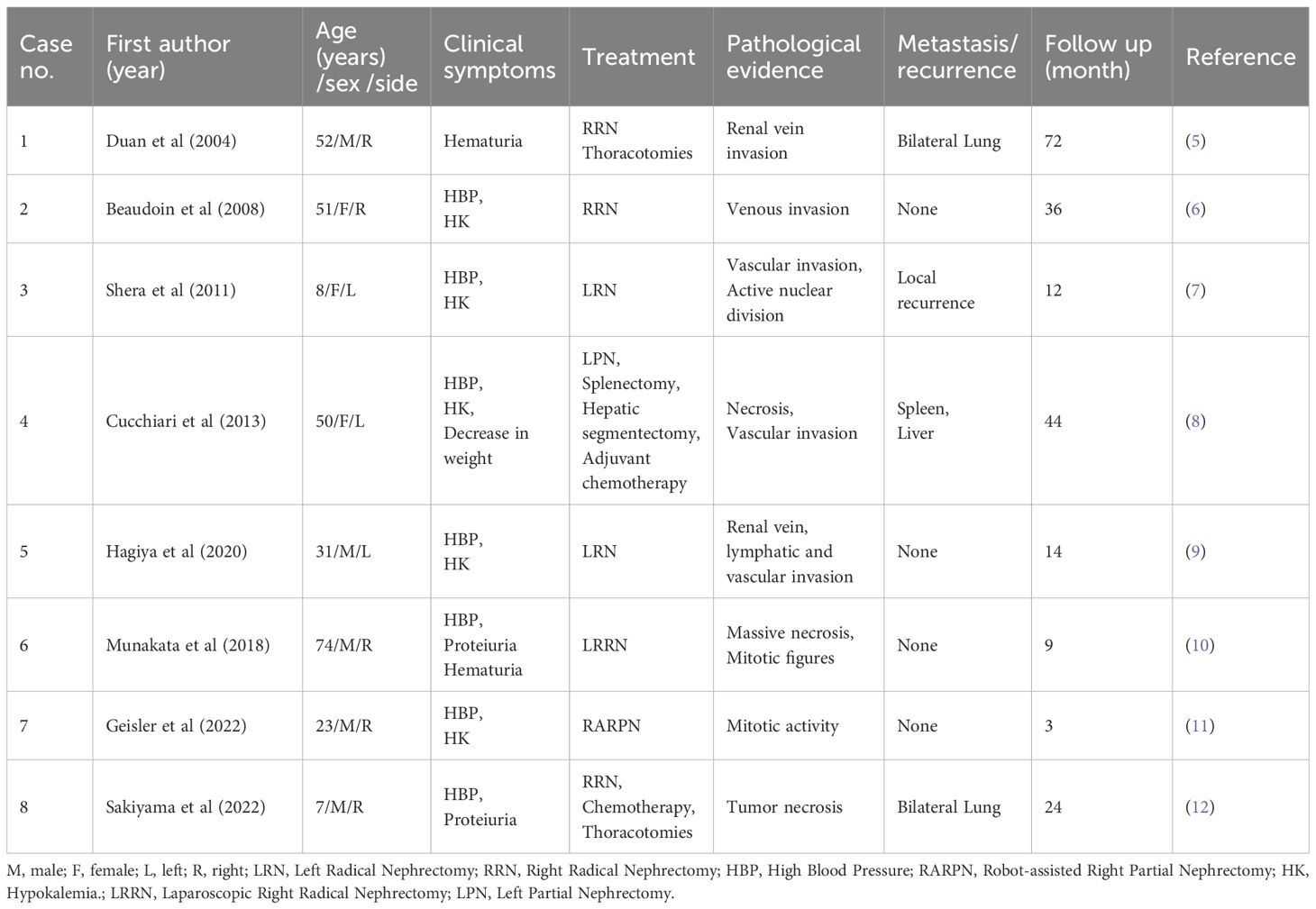

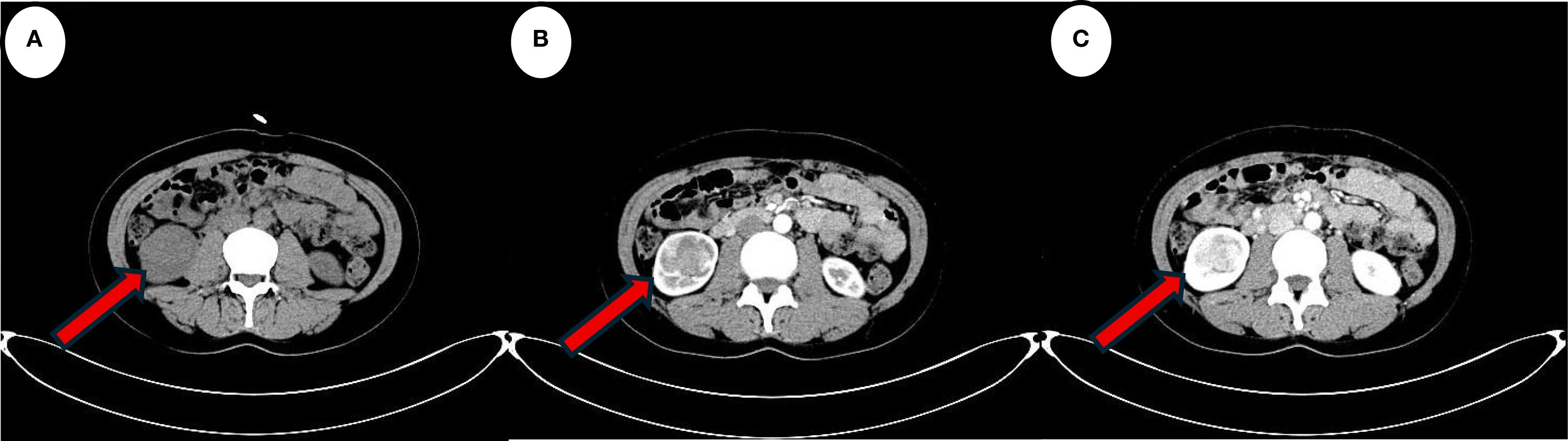

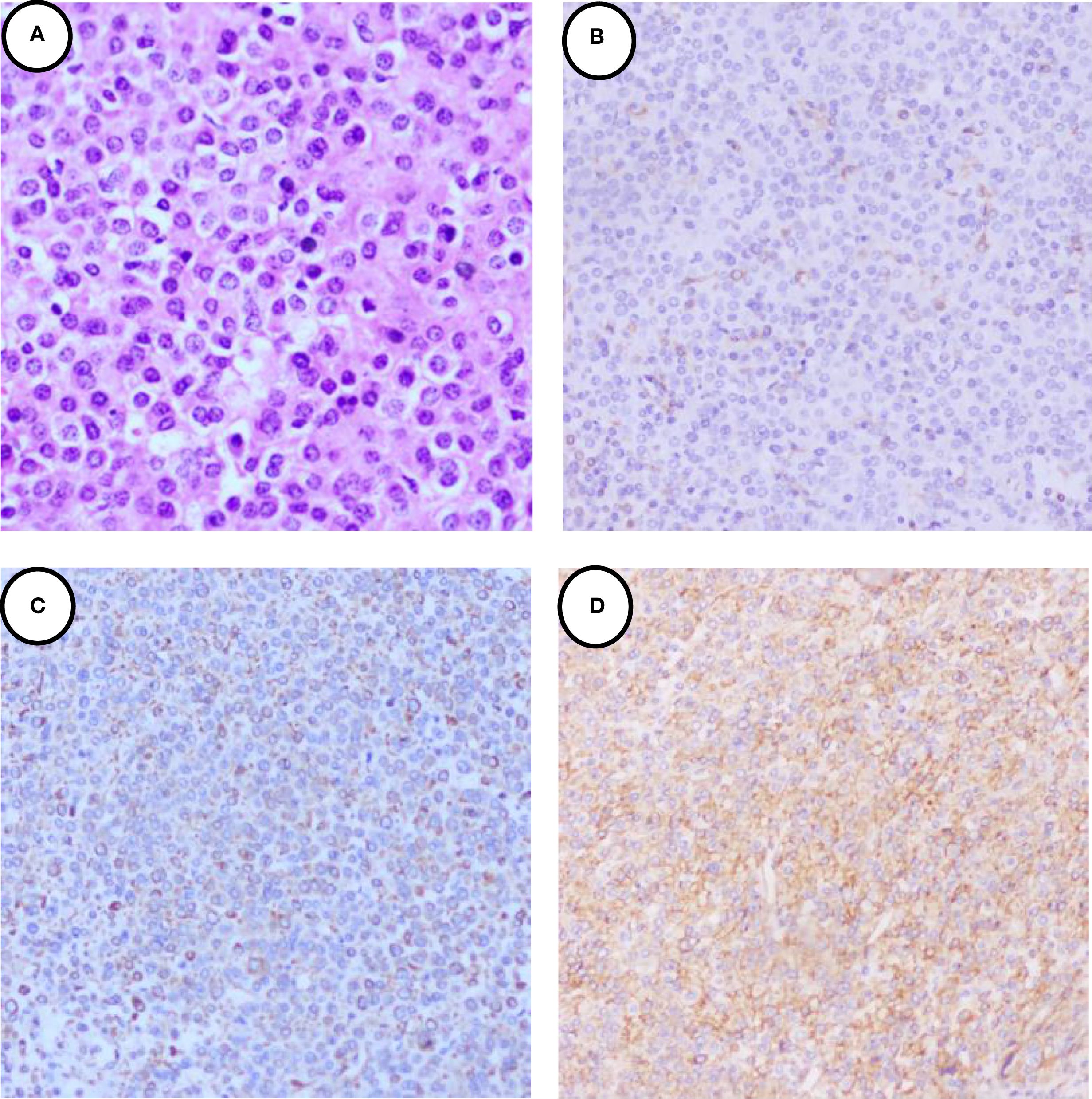

A 39-year-old female patient was admitted to the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University due to inadequate blood pressure control. To exclude the possibility of secondary hypertension, she underwent bilateral adrenal computed tomography scanning and enhancement. The results indicated that the body of the left adrenal gland exhibited slight thickening, while the right adrenal gland did not demonstrate any abnormalities in size, morphology, or density (Figures 1A–C). No abnormal reinforcement was identified in the enhancement scans. The right renal mass with obvious inhomogeneous enhancement measured approximately 61×35 mm. The patient was admitted to the urology department for further evaluation and treatment. The patient’s blood pressure had previously been inadequately controlled during pregnancy 10 years ago. The possibility of hypertension in pregnancy had been considered in the external hospital. The patient’s blood pressure remained unstable after the end of the pregnancy. The patient has been regularly monitored and treated with oral antihypertensive medication to date. The patient had a medical history significant only for hypertension and one previous pregnancy. She denied any family history of genetic disorders. Both of her parents were healthy and had no history of hypertension. After admission to the urology department, her blood pressure ranged from 155–165/83–88 mmHg. Physical examination revealed no significant abnormalities, particularly with respect to the cardiovascular, renal, and neurological systems. Following a thorough preoperative evaluation that ruled out any surgical contraindications, the patient underwent laparoscopic partial right nephrectomy. Postoperative pathology (see Figures 2A–D) showed the presence of tumor in the right kidney and the tumor cells appeared in a circular polygon shape with HE staining, which was confirmed by immunohistochemical staining. The following markers were observed: CD34 (+), Vimentin (+), ERG (scattered +), SMA (partially +), GATA3 (partially +), CD10 (partially +), CD117 (scattered +), S-100 (scattered +), Syn (scattered +), Ki-67 (2%+). The following markers were found to be negative: CK, CK5/6, CK7, HMB45, CA9, Ksp-cadherin, Melan-A, p63, PAX-8, RCC, TFE3, CD56, CgA, CK18, CK8, NSE, Desmin. Subsequent to the surgical procedure, the patient’s blood pressure exhibited a gradual return to its norm. Following a comprehensive analysis of the patient’s clinical manifestations, imaging findings, and pathological results, a diagnosis of JGCT was rendered. It is noteworthy that the patient’s blood pressure has been effectively managed since the postoperative follow-up. During the 13-month outpatient follow-up, the patient reported well-controlled blood pressure and had discontinued oral antihypertensive medications. Repeated laboratory tests showed that renal function and serum potassium levels remained within normal limits. Follow-up abdominal CT and abdominal ultrasound examinations showed no evidence of tumor recurrence. In order to enhance the clarity of the case and the narrative flow, we have added a visual timeline of the patient’s course of illness (Figure 3).

Figure 1. The red arrow indicates the lesion. (A) Computed tomography scan suggests a localised hypodense occupancy of the right kidney. (B) A small amount of enhancement is seen in the cortical phase of the enhanced scan. (C) Enhancement is more obvious in the medullary phase. The features are consistent with the typical presentation of JGCT imaging.

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining of the JGCT. (A) 40×H&E staining revealed that the tumor cells exhibited a round and polygonal morphology with homogeneous cytoplasm, and lacked clear cell borders and heterogeneity. (B) showed the tumor cells were cytoplasmic positive for CD34. (C) showed the tumor cells were cytoplasmic positive for Vimentin. (D) showed the tumor cells were cytoplasmic positive for SMA.

Discussion

JGCT is an extremely rare renal tumor, accounting for a very low proportion of all renal tumors (3). The cellular origin of JGCT is a focus of debate in the academic community, and the current trend is that it is a special group of cells differentiated from arterial smooth muscle cells during embryonic development of the body, which possesses a unique endocrine function due to its ability to secrete nephrin, based on the dual phenotypic characteristics of myogenic contractile properties and endocrine activity at the same time (4). Myoendocrine cells have been defined based on their dual phenotypic characteristics of myogenic contractile properties and endocrine activity. This provides an important morphofunctional basis for the in-depth analysis of its pathophysiological mechanisms. The following is a summary of cases of benign biological behavior of JGCT reported in the literature over the past decade (Table 1). The previously published biological behaviors of JGCT exhibit malignancy, as summarized in Table 2. The majority of JGCT are benign tumors that secrete large amounts of renin, which leads to secondary activation of the RAAS system, causing long-term uncontrollable hypertension in patients. Radical surgery can be a curative treatment; however, the biological behavior of JGCT showing malignant manifestations has also been reported in the past. Notwithstanding the potential for radical surgery to engender a positive outcome, there have been antecedent reports of JGCT manifesting malignant biological behavior. For instance, Duan et al. (5) documented a case of paraglomerular cell tumor invading the renal vein and developing bilateral lung metastases five years later, with a maximum diameter of the mass of 15 cm, deep vein and vena cava invasion, and necrosis of the tumor. Beaudoin et al. (6) reported a case of a 51-year-old female JGCT patient presenting with tumor invasion of blood vessels and a mass size of 9.8cm x 8.5cm x 7.3cm; Shera et al. (7) reported a case of an 8-year-old boy with paraglomerular paraganglioma recurring in the renal fossa 1 year after left nephrectomy, with an initial mass size of 8cm x 8cm and a tumor recurrence mass size of 5cm x 4cm with vascular and peripheral invasion and active nuclear division; Cucchiari et al. (8) reported a case of a 50-year-old man with paraglomerular cell tumor with multisite involvement in the kidney, liver, and spleen, and who underwent surgery and systemic therapy, and the disease progressed during treatment; Hagiya et al. (9) reported a JGCT case with atypical pathological features, in which the tumor invaded the renal vein, lymphatic and vascular invasion, with no signs of recurrence or metastasis at 14 months of follow-up; Munakata et al. (10) diagnosed a 74-year-old male patient with a tumor that did not appear to be metastatic, but postoperative pathology suggested that the tumor had massive necrosis and mitotic figures, and the patient survived for 9 months; Geisler et al. (11) diagnosed a rare young male patient with malignant JGCT and suggested that GATA3 positivity could be helpful in the diagnosis of other diseases; Sakiyama et al. (12) reported a case of a 7 year old boy with JGCT of the right kidney and multiple pulmonary metastases at the time of presentation; the metastatic lesions were pathological as those of the kidney, and the patient had no recurrence at 2 years of follow up. In cases of malignant biological behavior associated with JGCT, surgical intervention alone may not yield the desired outcomes, necessitating close monitoring and the development of a personalized systemic treatment plan.

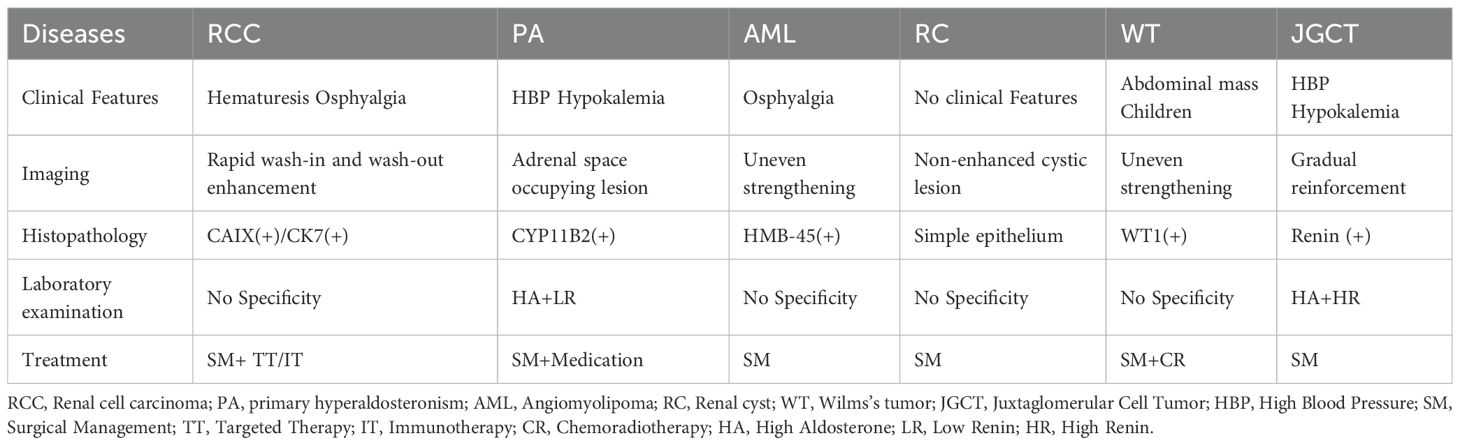

The typical presentation of JGCT is characterized by hypertension, hypokalemia, renin hypersecretion and secondary aldosteronism. However, the accurate diagnosis of atypical patients is challenging and should be considered when there is a combination of a renal mass and hypertension or hypokalemia. JGCT is rare, and therefore the differential diagnosis of JGCT is critical in smaller hospitals with inexperienced clinicians, based on the combination of clinical presentation, imaging and pathology. In order to differentiate this disease, clinical manifestations, imaging data and histology are required. Some of the common diseases that need to be differentiated are renal cell carcinoma, primary aldosteronism, angiomyolipoma, renal cysts and nephroblastoma (Table 3). JGCT is prevalent in adolescents and young adults, with a higher proportion of females (13), and its clinical presentation is as described above. Patients with atypical JGCT may have only a single symptom, such as hypertension or hypokalemia. Previous studies have concluded that computed tomography (CT) and computed tomography contrast are useful for the JGCT, having high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity (14). CT shows a low-density occupancy, and enhanced CT often suggests that the tumor has no significant enhancement in the cortical stage, and the CT value of tumors in the parenchymal stage is higher than that of the cortical stage, so that the tumors in the parenchymal and delayed stages are shown more clearly than those in the cortical stage (slow in progress and slow in regression) (15); however, as newer studies have been found to be useful, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has shown a better status in detecting JGCT (16). JGCT is shown to be a well-defined lesion on MRI, with isosignal or low-signal areas on T1-weighted images and predominantly high-signal on T2-weighted images, with homogeneous or haloed, nodular high-signal on DWI, and progressive enhancement on enhancement (17). It is important to note that the aforementioned examinations are merely suggestive, and a definitive diagnosis of the tumor necessitates a pathological examination. Light microscopic HE staining of JGCT revealed tumor cells with uniformly rounded, polygonal or spindle-shaped morphology, eosinophilic cytoplasm or light staining, unclear cell borders, small and regular nuclei, fine chromatin, and rare karyorrhexis. The histological structure exhibited solid sheets, nests or beams of tumor cells, and the interstitium was characterized by a high density of thin-walled blood vessels. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) phenotypes are specific and pivotal in confirming diagnoses. It is evident that the following positive markers (18) should be considered: The positivity of CD34 (+) is indicative of vascular endothelial markers (i.e. diffuse strong cytoplasmic positivity of the tumor cells, characteristic of the presentation), SMA (+) is suggestive of myxoid differentiation, and vimentin (+) is suggestive of mesenchymal origin. The most confirmatory marker is Renin. The most significant confirmatory marker is Renin, which demonstrates granular cytoplasmic positivity. Among the negative markers, CK (-), PAX8 (-), RCC (-), and HMB45 (-) have been found to be effective in excluding other renal tumors (19). Although Renin was not performed in this case, the patient was finally diagnosed as a case of JGCT by means of a differential diagnosis of the patient’s clinical presentation, imaging and a number of immunohistochemical positive, weakly positive and negative expression results.

It is noteworthy that several subtypes of renal cell carcinoma are characterized by the absence of clinical manifestations in the early stage, with a predilection for middle-aged and elderly patients. The typical presentation of the condition includes symptoms such as hematuria, lumbar pain and abdominal mass. However, with the increased prevalence of medical checkups in recent times, the number of patients exhibiting this triad has decreased. When it does occur, it may be indicative of advanced tumor growth. Furthermore, a computed tomography scan may reveal a rounded mass in the renal parenchyma. The distinction lies in the temporal profile of the enhancement scan for renal clear cell carcinoma, which manifests as a ‘fast in and fast out’ phenomenon, characterized by a substantial blood supply. In the arterial phase, the enhancement is conspicuous, and the tumor’s density is lower than that of the normal renal parenchyma. In the venous phase, the enhancement diminishes further, and the contrast with the surrounding tissues reveals an even lower density. The enhancement of papillary renal carcinoma is weaker and shows slow progressive enhancement, while that of chromophobe cell tumor is in between (20).

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is a real-time, dynamic imaging modality that can demonstrate the entire process of the contrast agent from its entry into the renal tumor and renal parenchyma until its subsidence. It also allows for observation of the tumor’s blood supply in real time. CEUS has been shown to have a role in differentiating cystic and solid masses in the kidney. Previous studies have reported that CEUS has higher sensitivity and specificity than enhanced CT in the differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic cystic renal lesions and solid tumors (21, 22). It has been reported in the literature that CEUS has a higher level of sensitivity and specificity than enhanced CT in the differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic renal cystic lesions and solid tumors (21, 22).CEUS is a more effective tool in the differential diagnosis of renal carcinoma, as it is typically fast-acting with high enhancement, and its performance differs significantly from that of renal tumors, which are chronic and with low enhancement (23). The rationale behind the examination of the low enhancement and chronicity of JGCT enhancement imaging is that the substantial renin output results in vasoconstriction, leading to the constriction of the lumen and, consequently, diminished blood flow (24).

As a renin-secreting tumor, elevated renin levels often lead to secondary aldosteronism, which in turn causes uncontrollable hypertension. This condition must be differentiated from primary aldosteronism (25, 26), where renin levels are often normal or reduced (27), and imaging suggests adrenal gland occupancy, which is responsible for about one-fifth of refractory hypertension (28). JGCT secretes excessive renin, and renin levels obtained by routine venous blood collection often lead to false negatives. It has been demonstrated that renin levels obtained from routine venous blood collection frequently result in false negatives. Consequently, previous studies have advocated that selective deep vein blood collection is of greater diagnostic value in identifying bilaterally different hormone levels (29). However, recent studies have indicated that renal vein blood collection is impractical in clinical settings, challenging to execute, and lacks sensitivity and specificity (27). Unfortunately, although the patient underwent bilateral adrenal CT scanning upon admission, which revealed mild left adrenal gland thickening, no space-occupying lesion was detected in the adrenal glands. Consequently, not all preoperative indicators for elevated blood pressure were thoroughly evaluated. Only routine preoperative preparations were completed to rule out surgical contraindications, and surgery was performed specifically to clarify the nature of the renal mass. Therefore, for patients with an established diagnosis of hypertension, if CT indicates adrenal gland thickening, adrenal hormone level testing should be performed to avoid poorly controlled blood pressure after JGCT resection and the need for secondary surgery.

The treatment option for JGCT is laparoscopic partial nephrectomy as the first choice (27, 30–32), but surgical treatment is absolutely feasible only after the diagnosis of secondary hypertension due to the source of the renal lesion has been made after characterization, localization, and etiology. Preoperative control of the patient’s blood pressure and active correction of hypokalemia are required (26), and PN can greatly preserve the function of the kidney itself and cure uncontrollable hypertension and electrolyte disorders (25, 27). A case of JGCT with long-term recurrent hypertension and renal insufficiency has been reported in the literature, and renal transplantation was performed due to renal failure after removal of the tumor (33), and there was also a patient with JGCT combined with membranous glomerulonephritis, whose blood pressure was normalized in a short period of time after the operation, but uncontrollable hypertension reappeared after one and a half years of follow up (34), so it is not that a single operation can solve the whole problem, and it is necessary to consider the patient’s condition comprehensively in order to develop an individualized plan for the patient. Therefore, not all problems can be solved by a single surgery, and comprehensive consideration of the patient’s condition is still needed, with a view to individualizing the treatment plan.

In summary, complete surgical excision remains the only curative approach and the gold standard for JGCT. The choice of surgical procedure depends on the size and location of the renal mass, as well as its relationship with blood vessels or the collecting system. Laparoscopic/robot-assisted partial nephrectomy is currently the preferred approach, as reflected in most previously published cases (Table 1), allowing complete tumor removal while preserving maximal functional renal parenchyma. Thorough preoperative preparation is essential, including strict control of blood pressure, management of complications, and correction of electrolyte imbalances. Postoperatively, blood pressure and potassium levels may not normalize immediately; antihypertensive and potassium supplementation therapies should be continued and tapered gradually based on the patient’s clinical response.

It has been established through previous studies that the occurrence of JGCT is associated with the expression of certain oncogenes located on chromosomes 4 and 10, and the loss of specific oncogenes on chromosomes 9, 11, and X (35–37).The primary treatment for JGCT remains surgical intervention; however, patients with metastases or those unable to undergo surgery may require systemic therapy. In 2023, Treger et al. (38) identified the NOTCH1 rearrangement in JGCT, which can be targeted by existing NOTCH1 inhibitors for therapeutic targeting. In 2024, Lobo et al. (39) emphasized a specified role for the MAPK-RAS pathway by IHC and whole exome sequencing (WES), but the specific pathogenesis of JGCT still needs to be explored by large-scale genomics. Overall, patients with JGCT have an excellent prognosis. Successful surgical removal of the lesion typically leads to complete resolution or significant improvement of hypertension and electrolyte disturbances, as demonstrated in the present case where the patient’s blood pressure remained within the normal range and no hypokalemia was observed during follow-up. The vast majority of JGCTs are benign; however, very few cases exhibit malignant biological behavior (Table 2). Therefore, in the presence of features suggestive malignancy, close postoperative surveillance is crucial.

Patient perspective

For years, I struggled with refractory hypertension and fatigue, unaware these were caused by a rare kidney tumor. The discovery of a renal lesion on CT was concerning, and the diagnosis felt overwhelming. However, surgery—recommended after my doctors identified a renal cause—led to a remarkable turnaround. My blood pressure normalized without medication, and repeated follow-ups confirmed normal results. This experience lifted a long-standing burden of anxiety. I am deeply grateful to my medical team and urge others with similar symptoms to seek timely, thorough evaluation. I provide full consent for my medical history to be shared and have signed the required informed consent form.

Conclusion

The classic triad of hypertension, hypokalemia, and a renal mass is highly suggestive of JGCT, which, although mostly benign, requires prompt and definitive surgical management. Histopathology remains the gold standard for diagnosis, as biochemical and imaging findings are only supportive. Complete resection, preferably through nephron-sparing surgery, is curative and typically resolves the metabolic abnormalities. Thus, in patients presenting with this triad, JGCT should be strongly suspected. Unnecessary medical management or delayed intervention must be avoided. Referral to specialized centers with experience in renal tumors is recommended to ensure accurate diagnosis and timely operation, both critical for favorable outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CZ: Writing – original draft. ZT: Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – review & editing. TY: Writing – review & editing. ZH: Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – review & editing. BY: Writing – review & editing. NZ: Writing – review & editing. NF: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the grants from the plan of Science and Technology of Zunyi (grant 2022-403), the Guizhou Provincial Health Commission (grant gzw kj2023-374) and The Zunyi Medical University College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program(ZYDC202301026).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Robertson PW, Klidjian A, Harding LK, Walters G, Lee MR, Robb-Smith AH, et al. Hypertension due to a renin-secreting renal tumor. Am J Med. (1967) 43:963–76. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(67)90256-2

2. Kihara I, Kitamura S, Hoshino T, Seida H, and Watanabe T. A hitherto unreported vascular tumor of the kidney: a proposal of ‘juxtaglomerular cell tumor’. Acta Patholigica Japonica. (1968) 18:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1968.tb00048.x

3. Moch H, Amin MB, Berney DM, Compérat EM, Gill AJ, Hartmann A, et al. The 2022 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs—part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumors. Eur Urol. (2022) 82:458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.06.016

4. Barajas L. Anatomy of the juxtaglomerular apparatus. Am J Physiology-Renal Physiol. (1979) 237:F333–43. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.237.5.F333

5. Duan X, Bruneval P, Hammadeh R, Fresco R, Eble JN, Clark JI, et al. Metastatic juxtaglomerular cell tumor in a 52-year-old man. Am J Surg Pathol. (2004) 28:1098–102. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126722.29212.a7

6. Beaudoin J, Périgny M, Têtu B, and Lebel M. A patient with a juxtaglomerular cell tumor with histological vascular invasion. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. (2008) 4:458–62. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0890

7. Shera AH, Baba AA, Bakshi IH, and Lone IA. Recurrent Malignant juxtaglomerular cell tumor: A rare cause of Malignant hypertension in a child. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surgeons. (2011) 16:152–4. doi: 10.4103/0971-9261.86876

8. Cucchiari D, Bertuzzi A, Colombo P, De Sanctis R, Faucher E, Fusco N, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: multicentric synchronous disease associated with paraneoplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 159:e240–2. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.5545

9. Hagiya A, Zhou M, Hung A, and Aron M. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor with atypical pathological features: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Surg Pathol. (2020) 28:87–91. doi: 10.1177/1066896919868773

10. Munakata S, Tomiyama E, and Takayama H. Case report of atypical juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Case Rep Pathol. (2018) 2018:6407360. doi: 10.1155/2018/6407360

11. Geisler D, Almutairi F, John I, Quiroga-Garza G, Yu M, Seethala R, et al. Malignant juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Urol Case Rep. (2022) 45:102176. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2022.102176

12. Sakiyama H, Hamada S, Oshiro T, Hyakuna N, Kuda M, Hishiki T, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor with pulmonary metastases: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2023) 70(4):e30068. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30068

13. More IAR, Jackson AM, and MacSween RNM. Renin-secreting tumor associated with hypertension. Cancer. (1974) 34:2093–102. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197412)34:6<2093::AID-CNCR2820340633>3.0.CO;2-B

14. Tanabe A, Naruse M, Ogawa T, Ito F, Takagi S, Takano K, et al. Dynamic computer tomography is useful in the differential diagnosis of juxtaglomerular cell tumor and renal cell carcinoma. Hypertension Res. (2001) 24:331–6. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.331

15. Rosei CA, Giacomelli L, Salvetti M, Paini A, Corbellini C, Tiberio G, et al. Advantages of renin inhibition in a patient with reninoma. Int J Cardiol. (2015) 187:240–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.280

16. Faucon AL, Bourillon C, Grataloup C, Baron S, and Bernadet-Monrozies P. Usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of juxtaglomerular cell tumors: a report of 10 cases and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. (2019) 73:566–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.09.005

17. Kang S, Guo A, Wang H, Ma L, Xie Z, Li J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging features of a juxtaglomerular cell tumor. J Clin Imaging Sci. (2015) 5:68. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.172976

18. Wang F, Shi C, Cui Y, Li C, and Tong A. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: clinical and immunohistochemical features. J Clin Hypertension. (2017) 19:807–12. doi: 10.1111/jch.12997

19. Méndez GP, Klock C, and Nosé V. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney: case report and differential diagnosis with emphasis on pathologic and cytopathologic features. Int J Surg Pathol. (2011) 19:93–8. doi: 10.1177/1066896908329413

20. Leveridge MJ, Bostrom PJ, Koulouris G, Finelli A, and Lawrentschuk N. Imaging renal cell carcinoma with ultrasonography, CT and MRI. Nat Rev Urol. (2010) 7:311–25. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.63

21. Pan KH, Jian L, Chen WJ, Nikzad AA, Kong FQ, Bin X, et al. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in renal cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:586949. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.586949

22. Aoki S, Hattori R, Yamamoto T, Funahashi Y, Matsukawa Y, Gotoh M, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound using a time-intensity curve for the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. (2011) 108:349–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09799.x

23. Tufano A, Drudi FM, Angelini F, Polito E, Martino M, Granata A, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the evaluation of renal masses with histopathological validation—Results from a prospective single-center study. Diagnostics. (2022) 12:1209. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12051209

24. Kim JH, Li S, Khandwala Y, Chung KJ, Park HK, Chung BI, et al. Association of prevalence of benign pathologic findings after partial nephrectomy with preoperative imaging patterns in the United States from 2007 to 2014. JAMA Surg. (2019) 154:225–31. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4602

25. Gu WJ, Zhang LX, Jin N, Ba JM, Dong J, Wang DJ, et al. Rare and curable renin-mediated hypertension: a series of six cases and a literature review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 29:209–16. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2015-0025

26. Hommos MS and Schwartz GL. Clinical value of plasma renin activity and aldosterone concentration in the evaluation of secondary hypertension, a case of reninoma. J Am Soc Hypertens. (2018) 12:641–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2018.06.001

27. Liu K, Wang B, Ma X, Li H, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. Minimally invasive surgery-based multidisciplinary clinical management of reninoma: a single-center study. Med Sci Monitor: Int Med J Exp Clin Res. (2019) 25:1600. doi: 10.12659/MSM.913826

28. Rossi GP, Bisogni V, Rossitto G, Maiolino G, Cesari M, Zhu R, et al. Practice recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of the most common forms of secondary hypertension. High Blood Pressure Cardiovasc Prev. (2020) 27:547–60. doi: 10.1007/s40292-020-00415-9

29. Osawa S, Hosokawa Y, Soda T, Yasuda T, Kaneto H, Kitamura T, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor that was preoperatively diagnosed using selective renal venous sampling. Internal Med. (2013) 52:1937–42. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0395

30. Torricelli FC, Marchini GS, Colombo JR, Coelho RF, Nahas WC, Srougi M, et al. Nephron-sparing surgery for treatment of reninoma: a rare renin secreting tumor causing secondary hypertension. Int Braz J urol. (2015) 41:172–6. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.23

31. Dong D, Li H, Yan W, and Xu W. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney—a new classification scheme. Urol Oncol. (2010) 28:34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.08.003

32. Ye Z, Fan H, Tong A, Xiao Y, and Zhang Y. The small size and superficial location suggest that laparoscopic partial nephrectomy is the first choice for the treatment of juxtaglomerular cell tumors. Front Endocrinol. (2021) 12:646–9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.646649

33. Bonsib SM and Hansen KK. Juxtaglomeruler cell tumors: A report of two cases with negative HMB-45 immunostaining. J Urol Pathol. (1998) 9:61–72. doi: 10.1385/JUP:9:1:61

34. Ng SB, Tan PH, Chuah KL, Cheng C, and Tan J. A case of juxtaglomerular cell tumor associated with membranous glomerulonephritis. Ann Diagn Pathol. (2003) 7:314–20. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2003.08.002

35. Kuroda N, Maris S, Monzon FA, Tan PH, Thomas A, Petersson FB, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a morphological, immunohistochemical and genetic study of six cases. Hum Pathol. (2013) 44:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.04.006

36. Capovilla M, Couturier J, Molinié V, Amsellem-Ouazana D, Priollet P, Baumert H, et al. Loss of chromosomes 9 and 11 may be recurrent chromosome imbalances in juxtaglomerular cell tumors. Hum Pathol. (2008) 39:459–62. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.010

37. Brandal P, Busund LT, and Heim S. Chromosome abnormalities in juxtaglomerular cell tumors. Cancer: Interdiscip Int J Am Cancer Soc. (2005) 104:504–10. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21205

38. Treger TD, Lawrence JE, Anderson ND, Coorens TH, Letunovska A, Abby E, et al. Targetable NOTCH1 rearrangements in reninoma. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:5826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41118-8

39. Lobo J, Canete-Portillo S, Pena MD, McKenney JK, Aron M, Massicano F, et al. Molecular characterization of juxtaglomerular cell tumors: evidence of alterations in MAPK–RAS pathway. Modern Pathol. (2024) 37:100492. doi: 10.1016/j.modpat.2024.100492

40. Vidal-Petiot E, Bens M, Choudat L, Fernandez P, Rouzet F, Hermieu JF, et al. A case report of reninoma: radiological and pathological features of the tumour and characterization of tumour-derived juxtaglomerular cells in culture. J Hypertension. (2015) 33(8):1709–15.

41. Gil NS, Han JY, Ok SH, Shin IW, Lee HK, Chung YK, et al. Anesthetic management for percutaneous computed tomography-guided radiofrequency ablation of reninoma: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiology. (2015) 68(1):78–82.

42. Sierra JT, Rigo D, Arancibia A, Mukdsi J, Nicolai S, and Ortiz ME. Juxtaglomerular cell tumour as a curable cause of hypertension: case presentation. Nefrología (English Edition). (2015) 35(1):110–14.

43. Yang H, Wang Z, and Ji J. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: A case report. Oncol Lett. (2016) 11(2):1418–20.

44. Soni A and Gordetsky JB. Adult pleomorphic juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Urology. (2016) 87:e5–e7.

45. Wu T, Gu JQ, Duan X, and Yu XD. Hypertension due to juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. (2016) 32(5):276.

46. Ma ZL, Jia ZK, Gu CH, and Yang JJ. A Case of Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor of the Kidney Treated with Retroperitoneal Laparoscopy Partial Nephrectomy. Chinese Med J. (2016) 129(2):250.

47. Pacilli M, O'Brien M, and Heloury Y. Laparoscopic nephro-sparing surgery of juxtaglomerular cell tumor in a child. J Pediatric Urol. (2016) 12(5):321–2.

48. Miyano G, Nagano C, Morita K, Yamoto M, Kaneshiro M, Miyake H, et al. A case of juxtaglomerular cell tumor, or reninoma, of the kidney treated by retroperitoneoscopy-assisted nephron-sparing partial nephrectomy through a small pararectal incision. J Laparoendoscopic & Adv Surg Techniques. (2016) 26(3):235–8.

49. Xue M, Chen Y, Zhang J, Guan Y, Yang L, and Wu B. Reninoma coexisting with adrenal adenoma during pregnancy: a case report. Oncol Lett. (2017) 13(5):3186–90.

50. Daniele A, Sabbadin C, Costa G, Vezzaro R, Battistel M, Saraggi D, et al. A 10-year history of secondary hypertension: a challenging case of renin-secreting juxtaglomerular cell tumor. J Hypertension. (2018) 36(8):1772–4.

51. Nunes I, Santos T, Tavares J, Correia L, Coutinho J, Nogueira JB, et al. Secondary hypertension due to a juxtaglomerular cell tumor. J Am Soc Hypertension. (2018) 12(9):637–40.

52. Walasek A, Gupta S, Fine S, and Russo P. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a rare, curable cause of hypertension in a young patient. Urology. (2019) 134:42–44.

53. Nassiri N, Maas M, Fichtenbaum EJ, and Aron M. A Young female with refractory hypertension. Urology. (2020) 135:e1.

54. Krishnan A, Jacob J, and Patel T. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor in a young male presenting with new onset congestive heart failure. Urology Case Reports. (2020) 31:101189.

55. Jiang Y, Hou G, Zhu Z, Zang J, and Cheng W. Increased FDG uptake on juxtaglomerular cell tumor in the left kidney mimicking malignancy. Clin Nuclear Med. (2020) 45(3):252–4.

56. Dong J, Xu W, and Ji Z. Case report: a nonfunctioning juxtaglomerular cell tumor mimicking renal cell carcinoma. Medicine. (2020) 99(36):e22057.

57. Mezoued M, Habouchi MA, Azzoug S, Mokkedem K, and Meskine D. Juxtaglomerular cell cause of secondary hypertension in an adolescent. Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest). (2020) 16(3):359.

58. Phillis C, Midenberg E, O'Connor M, Terry W Jr, Keel C, and Noh P. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a rare presentation of a surgically curable cause of secondary hypertension in the pediatric population. Urology. (2021) 156:e131–e133.

59. Papez J, Starha J, Zerhau P, Pavlovska D, Jezova M, Jurencak T, et al. Spindle cell hemangioma and atypically localized juxtaglomerular cell tumor in a patient with hereditary BRIP1 mutation: a case report. Genes. (2021) 12(2):220.

60. Pan ZJ, Zhang ZC, Jiang XZ, Zhao HF, Wang S, Han RY, et al. Juxtaglomerular Cell Tumor: A Rare Cause of Hypertension. Urology. (2021) 158:3–4.

61. Ueda T, Morinaga Y, Inoue K, Hirano S, Matsubara H, and Hongo F. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor diagnosed preoperatively by renal tumor biopsy. IJU Case Rep. (2021) 4(4):207.

62. Skarakis NS, Papadimitriou I, Papanastasiou L, Pappa S, Dimitriadi A, Glykas I, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumour of the kidney: a rare cause of resistant hypertension. Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabol Case Rep. (2022) 2022(1).

63. Quach P and Hamza A. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: report of a case with unusual presentation. Autopsy and Case Reports. (2022) 12:e2021406.

64. John A, Cohen P, and Catterwell R. Robot–assisted partial nephrectomy with selective arterial clamping for an endophytic juxtaglomerular cell tumour: a case report. ANZ J Surg. (2023) 93(1–2):415–7.

65. Mondschein R, Kwan E, Abou-Seif C, and Rajarubendra N. Accurate lesion localisation facilitates nephron sparing surgery in reninoma patients: case report and discussion. Urology Case Rep. (2022) 43:102069.

66. Ruan Y, Lian F, Tian Y, Li Q, and Huang X. A case of pediatric secondary hypertension caused by juxtaglomerular cell tumor. Quantitative Imaging Med Surg. (2023) 13(9):6296.

67. Aouini H, Saadi A, Boussaffa H, Zaghbib S, Chakroun M, and Slama B. A juxtaglomerular cell tumor revealed by a hemorrhagic stroke. A case report. Urology Case Rep. (2023) 50:102535.

68. Pompozzi LA, Iturzaeta A, Deregibus MI, Steinbrun S, and Centeno MD. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor (reninoma) as a cause of arterial hypertension in adolescents. A case report. Archivos argentinos de pediatria. (2023) 121(4):e202202835.

69. Fu X, Deng G, Wang K, Shao C, and Xie LP. Pregnancy complicated by juxtaglomerular cell tumor of the kidney: A case report.World J Clin Cases. (2023) 11(11):2541.

70. Sekhon SS, Taha K, Kim LH, Humphreys R, Patel TJ, Andrews AR, et al. A Pediatric Case of Reninoma Presenting with Paraneoplastic Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion. Hormone Res in Paediatrics. (2024) 97(5):515–22.

71. Yan DE, He HB, Guo JP, Wang YL, Peng DP, Zheng HH, et al. Renal venous sampling assisted the diagnosis of juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a case report and literature review.Front Oncol. (2024) 13:1298684.

72. Chen G, Zhang Y, Xiong X, Li Z, Hua X, Li Z, et al. Renovascular hypertension following by juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a challenging case with 12-year history of resistant hypertension and hypokalemia. BMC Endocrine Disorders. (2024) 24(1):244.

73. Chaker K, Tlili S, Zehani A, Gharbia N, Snoussi M, Frikha W, et al. Juxtaglomerular cell tumor: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2025) 19(1):197.

Keywords: juxtaglomerular cell tumor, hypertension, rare disease, differential diagnosis, case report, review

Citation: Zhu C, Tian Z, Zhang Y, Yang T, He Z, Chen S, Yu B, Zhang N and Fu N (2025) Rare renal tumor: a case report of juxtaglomerular cell tumor and literature review. Front. Oncol. 15:1648756. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1648756

Received: 17 June 2025; Accepted: 09 September 2025;

Published: 30 September 2025.

Edited by:

Salvatore Siracusano, University of L’Aquila, ItalyReviewed by:

Xiaojuan Wu, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaErik Kouba, Sonic Healthcare, United States

Copyright © 2025 Zhu, Tian, Zhang, Yang, He, Chen, Yu, Zhang and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neng Zhang, ZW5lcmd5MjAxNzAxMThAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; Ni Fu, MTg5ODU2MDExODhAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Cheng Zhu1†

Cheng Zhu1† Tingting Yang

Tingting Yang Shicheng Chen

Shicheng Chen Bo Yu

Bo Yu Neng Zhang

Neng Zhang Ni Fu

Ni Fu